Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Genes in Drosophila melanogaster

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. SOD1 Gene

2.1. dSod1 and the Aging Theory

2.2. Drosophila as a Modeling Tool to Understand hSOD1-Induced ALS

2.2.1. hSOD1 Was the First Gene Linked to ALS Disease

2.2.2. Gain-of-Function Drosophila Models

2.2.3. Knock-In hSOD1 in Drosophila Led to Unexpected Results

2.3. ALS Drosophila Model to Test Neuroprotective Drug Candidates

3. C9orf72 Repeat Expansions

3.1. Loss of C9orf72 Function

3.2. Sequestration of Proteins by Expanded Repeat in RNA Foci

3.3. Dipeptide Repeats Protein Toxicity

4. FUS, an RNA-Binding Protein Associated with ALS

4.1. Drosophila Models of FUS-Related Neurodegeneration

4.2. From FUS Endogenous Functions to Toxicity

4.2.1. Nuclear and Cytoplasmic Localization of a Shuttle Protein

4.2.2. FUS Alters Mitochondrial Physiology

4.2.3. FUS in the Nucleus Is Associated with Nuclear Bodies

4.2.4. FUS Is a Multidomain Protein: Structure and Function

4.2.5. FUS Is an RBP Found in Stress Granules

4.2.6. FUS and Its Post-Translational Modifications (PTMs)

4.3. Search for Suppressors of FUS-Induced Neurodegeneration

4.3.1. Nucleocytoplasmic Localization

4.3.2. Transcriptional Regulation

4.3.3. Piwi-Interacting RNA (piRNA) Biogenesis

4.3.4. Cytoplasmic Mislocalization and SGs

4.3.5. Hippo and c-Jun N-Terminal Kinase (JNK) Signaling Pathways

5. TDP-43 Proteinopathy in the Fruit Fly

5.1. TBPH Is the Drosophila Ortholog of Human TARDBP

5.1.1. TBPH Loss of Function

5.1.2. TBPH and TDP-43 Share the Same Functions

5.2. TBPH and TDP-43 Gain of Function Mutations Are Toxic

5.2.1. Toxicity

5.2.2. TBPH and TDP-43 Gain-of-Function Phenotypes Are Dose- and Age-Dependent

5.2.3. TDP-43/TBPH Toxicity Requires RNA Binding

5.2.4. TDP-43/TBPH Toxicity and Nucleocytoplasmic Localization

5.2.5. TDP-43 Toxicity of ALS-Linked TDP-43 Mutations

5.3. Molecular Mechanisms Underlying TDP-43 Toxicity

5.3.1. Splicing Repression

5.3.2. Mitochondrial Dysfunction

5.3.3. Transposon Upregulation

5.3.4. Excitotoxicity

5.4. Genetic Modifiers of TDP-43 Toxicity

5.4.1. Stress Granules

5.4.2. Cytoplasmic Aggregation

5.4.3. Unfolded Protein Response

5.4.4. Inflammation

5.4.5. Mammalian Target of Rapamycin (mTOR) Pathway

5.4.6. Autophagosomes

5.4.7. Chaperone

5.4.8. Chromatin

5.4.9. hnRNPs

5.4.10. Metabolic Deregulation

5.5. Target RNAs

5.5.1. Futsch

5.5.2. Histone Deacetylase 6 (HDAC6)

5.5.3. Cacophony

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ALS | Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis |

| arcRNA | Architectural RNA |

| Arg | Arginine |

| ATP | Adenosine triphosphate |

| Aub | Aubergine |

| BMAA | β-N-methylamino l-alanine |

| C9ORF72 | Chromosome 9 open reading frame 72 |

| Ca | Calcium |

| Cas9 | CRISPR-associated protein 9 |

| Caz | Cabeza |

| CCAP | Crustacean cardioactive peptide |

| Chip | Chromatin immunoprecipitation |

| CNS | Central nervous system |

| CRISPR | Clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats |

| Cu | Copper |

| DART5 | Drosophila arginine methyltransferase protein 5 |

| dDSIF | Drosophila DRB sensitivity-inducing factor |

| dEAAT1 | Drosophila excitatory amino acid transporter 1 |

| dFMR1 | Drosophila Fragile X mental retardation 1 |

| dFMRP | Drosophila Fragile X mental retardation protein |

| Dlg | Discs-large |

| DNA | Deoxyribonucleic acid |

| dPAF1 | Drosophila polymerase-associated factor 1 |

| DPR | Dipeptide proteins |

| eIF1A | Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 1A |

| eIF2α | Eukaryotic initiation factor 2α |

| EJP | Excitatory junction potential |

| Elav | Embryonic lethal abnormal visual protein |

| ER | Endoplasmic reticulum |

| EWS | Ewing sarcoma |

| fALS | Familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis |

| FET | FUS EWS TAF15 family of proteins |

| FUS | Fused in sarcoma |

| FTD | Frontotemporal dementia |

| Gad1 | Glutamic acid decarboxylase 1 |

| GDP | Guanosine diphosphate |

| GFP | Green fluorescent protein |

| GluRIIA | Glutamate receptor IIA |

| Gly | Glycine |

| GMR | Glass multiple reporter |

| GOF | Gain of function |

| GRD | Glycine-rich domain |

| GS | GeneSwitch |

| GTP | Guanosine triphosphate |

| HDAC6 | Histone deacetylase 6 |

| HEK/HEK293 | Human embryonic kidney 293 |

| HeLa | Henrietta Lacks |

| Hpo | Hippo |

| hnRNP | Heterogenous nuclear ribonucleoprotein |

| HSP60 | Heat-shock protein 60 |

| HSP70 | Heat-shock protein 70 |

| HRE | Hexanucleotide repeat expansion |

| IP3 | Inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate |

| iPSC | Induced pluripotent stem cell |

| ITPR1 | Inositol-1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor type 1 |

| JNK | c-Jun N-terminal kinase |

| Kapβ2 | Karyopherin-β2 |

| kDa | Kilodalton |

| mTORC1 | Mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 |

| LA | α-Lipoic acid |

| LAMP-1 | Lysosomal-associated membrane protein 1 |

| LCD | Low-complexity domain |

| lncRNA | Long non-coding RNA |

| LOF | Loss of function |

| MARCM | Mosaic analysis with a repressible cell marker |

| miRNA | MicroRNAs |

| mRNA | Messenger RNA |

| NB | Nuclear body |

| NES | Nuclear export signal |

| NIR | Nuclear import receptor |

| NMJ | Neuromuscular junction |

| NLS | Nuclear localization signal |

| Nup | Nucleoporin |

| Orz | γ-Oryzanol |

| PABPN1 | Poly(A)-binding protein nuclear 1 |

| PARG | Poly(ADP-ribose) glycohydrolase |

| PARP1 | Poly(ADP-ribose)ylation polymerase 1 |

| PEK | Poly(ADP-ribose)ylation glycohydrolase |

| PINK1 | PTEN-induced kinase 1 |

| piRNA | Piwi-interacting RNA |

| PrLD | Prion-like domain |

| poly-GA | Poly-glycine/alanine |

| poly-GP | Poly-glycine/proline |

| poly-GR | Poly-glycine/arginine |

| poly-PA | Poly-proline/alanine |

| poly-PR | Poly-proline/arginine |

| PTM | Post-translational modification |

| PTP1B | Tyrosine phosphatase 1B |

| qPCR | Quantitative polymerase chain reaction |

| QGSY | Glutamine, glycine, serine, and tyrosine residues |

| RAN | Repeat-associated non-AUG |

| RanGAP | Ras-related nuclear GTPase-activating protein |

| RAVER1 | Ribonucleoprotein, PTB-binding 1 |

| RBP | RNA-binding protein |

| Rbp1 | RNA-binding protein 1 |

| RGG | Arginine glycine rich domain |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| RRM | RNA recognition motif |

| RNA | Ribonucleic acid |

| RNAi | RNA interference |

| RTE | Retrotransposable element |

| RT-PCR | Reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction |

| sALS | Sporadic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis |

| SF2 | Splicing factor 2 |

| Sf3b-1 | Splicing factor 3b subunit 1 |

| SG | Stress granule |

| siRNA | Small interfering RNA |

| SOD | Superoxide dismutase |

| SOP | Sensory organ precursor |

| TAF15 | TATA box-binding protein-associated factor 68 kDa |

| TARDBP | TAR DNA-binding protein |

| TARGET | Temporal and regional gene expression targeting |

| TBPH | TAR DNA-binding protein-43 homolog |

| TCERG1 | Transcription elongation regulator 1 |

| TDP-43 | TAR DNA-binding protein 43 |

| TDPBR | TDP-43 binding region |

| Ter94 | Transitional endoplasmic reticulum 94 |

| TLS | Translocated in liposarcoma |

| TMPyP4 | 5,10,15,20-Tetrakis-(N-methyl-4-pyridyl)porphine |

| UAS | Upstream activating sequence |

| UBPY | Ubiquitin isopeptidase Y |

| UPR | Unfolded protein response |

| UTR | Untranslated transcribed region |

| VCP | Valosin-containing protein |

| Wnd | Wallenda |

| WT | Wildtype |

| XPO1 | Exportin 1 |

| Zfp106 | Zing finger protein 106 |

| Zn | Zinc |

| ZnF | Zinc finger domain |

References

- Brown, R.H.; Al-Chalabi, A. Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 377, 162–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardiman, O.; Al-Chalabi, A.; Chio, A.; Corr, E.M.; Logroscino, G.; Robberecht, W.; Shaw, P.J.; Simmons, Z.; van den Berg, L.H. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2017, 3, 17071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowland, L.P.; Shneider, N.A. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2001, 344, 1688–1700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Es, M.A.; Hardiman, O.; Chio, A.; Al-Chalabi, A.; Pasterkamp, R.J.; Veldink, J.H.; van den Berg, L.H. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Lancet 2017, 390, 2084–2098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longinetti, E.; Fang, F. Epidemiology of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: An update of recent literature. Curr. Opin. Neurol. 2019, 32, 771–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Liu, T.; Liu, L.; Yao, X.; Chen, L.; Fan, D.; Zhan, S.; Wang, S. Global variation in prevalence and incidence of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Neurol. 2020, 267, 944–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappello, V.; Francolini, M. Neuromuscular Junction Dismantling in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 2092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleveland, D.W.; Rothstein, J.D. From Charcot to Lou Gehrig: Deciphering selective motor neuron death in ALS. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2001, 2, 806–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, L.M.; Hollander, D. Respiratory dysfunction in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Clin. Chest Med. 1994, 15, 675–681. [Google Scholar]

- Crabé, R.; Aimond, F.; Gosset, P.; Scamps, F.; Raoul, C. How Degeneration of Cells Surrounding Motoneurons Contributes to Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Cells 2020, 9, 2550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramzon, Y.A.; Fratta, P.; Traynor, B.J.; Chia, R. The Overlapping Genetics of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis and Frontotemporal Dementia. Front. Neurosci. 2020, 14, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elamin, M.; Bede, P.; Byrne, S.; Jordan, N.; Gallagher, L.; Wynne, B.; O’Brien, C.; Phukan, J.; Lynch, C.; Pender, N.; et al. Cognitive changes predict functional decline in ALS: A population-based longitudinal study. Neurology 2013, 80, 1590–1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phukan, J.; Elamin, M.; Bede, P.; Jordan, N.; Gallagher, L.; Byrne, S.; Lynch, C.; Pender, N.; Hardiman, O. The syndrome of cognitive impairment in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: A population-based study. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2012, 83, 102–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappella, M.; Ciotti, C.; Cohen-Tannoudji, M.; Biferi, M.G. Gene Therapy for ALS-A Perspective. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 4388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boylan, K. Familial Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Neurol. Clin. 2015, 33, 807–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mejzini, R.; Flynn, L.L.; Pitout, I.L.; Fletcher, S.; Wilton, S.D.; Akkari, P.A. ALS Genetics, Mechanisms, and Therapeutics: Where Are We Now? Front. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shatunov, A.; Al-Chalabi, A. The genetic architecture of ALS. Neurobiol. Dis. 2021, 147, 105156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Z.Y.; Zhou, Z.R.; Che, C.H.; Liu, C.Y.; He, R.L.; Huang, H.P. Genetic epidemiology of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2017, 88, 540–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, D.R.; Siddique, T.; Patterson, D.; Figlewicz, D.A.; Sapp, P.; Hentati, A.; Donaldson, D.; Goto, J.; O’Regan, J.P.; Deng, H.X.; et al. Mutations in Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase gene are associated with familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Nature 1993, 362, 59–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fridovich, I. Superoxide anion radical (O2-.), superoxide dismutases, and related matters. J. Biol. Chem. 1997, 272, 18515–18517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeJesus-Hernandez, M.; Mackenzie, I.R.; Boeve, B.F.; Boxer, A.L.; Baker, M.; Rutherford, N.J.; Nicholson, A.M.; Finch, N.A.; Flynn, H.; Adamson, J.; et al. Expanded GGGGCC hexanucleotide repeat in noncoding region of C9ORF72 causes chromosome 9p-linked FTD and ALS. Neuron 2011, 72, 245–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renton, A.E.; Majounie, E.; Waite, A.; Simón-Sánchez, J.; Rollinson, S.; Gibbs, J.R.; Schymick, J.C.; Laaksovirta, H.; van Swieten, J.C.; Myllykangas, L.; et al. A hexanucleotide repeat expansion in C9ORF72 is the cause of chromosome 9p21-linked ALS-FTD. Neuron 2011, 72, 257–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majounie, E.; Renton, A.E.; Mok, K.; Dopper, E.G.; Waite, A.; Rollinson, S.; Chiò, A.; Restagno, G.; Nicolaou, N.; Simon-Sanchez, J.; et al. Frequency of the C9orf72 hexanucleotide repeat expansion in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and frontotemporal dementia: A cross-sectional study. Lancet Neurol. 2012, 11, 323–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sellier, C.; Campanari, M.L.; Julie Corbier, C.; Gaucherot, A.; Kolb-Cheynel, I.; Oulad-Abdelghani, M.; Ruffenach, F.; Page, A.; Ciura, S.; Kabashi, E.; et al. Loss of C9ORF72 impairs autophagy and synergizes with polyQ Ataxin-2 to induce motor neuron dysfunction and cell death. EMBO J. 2016, 35, 1276–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, W.; Hu, F. Cellular and physiological functions of C9orf72 and implications for ALS/FTD. J. Neurochem. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratti, A.; Buratti, E. Physiological functions and pathobiology of TDP-43 and FUS/TLS proteins. J. Neurochem. 2016, 138 (Suppl. 1), 95–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvio, C.; Neubauer, G.; Mann, M.; Lamond, A.I. Identification of hnRNP P2 as TLS/FUS using electrospray mass spectrometry. RNA 1995, 1, 724–733. [Google Scholar]

- Morohoshi, F.; Ootsuka, Y.; Arai, K.; Ichikawa, H.; Mitani, S.; Munakata, N.; Ohki, M. Genomic structure of the human RBP56/hTAFII68 and FUS/TLS genes. Gene 1998, 221, 191–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwiatkowski, T.J., Jr.; Bosco, D.A.; Leclerc, A.L.; Tamrazian, E.; Vanderburg, C.R.; Russ, C.; Davis, A.; Gilchrist, J.; Kasarskis, E.J.; Munsat, T.; et al. Mutations in the FUS/TLS gene on chromosome 16 cause familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Science 2009, 323, 1205–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vance, C.; Rogelj, B.; Hortobágyi, T.; de Vos, K.J.; Nishimura, A.L.; Sreedharan, J.; Hu, X.; Smith, B.; Ruddy, D.; Wright, P.; et al. Mutations in FUS, an RNA processing protein, cause familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis type 6. Science 2009, 323, 1208–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann, M.; Sampathu, D.M.; Kwong, L.K.; Truax, A.C.; Micsenyi, M.C.; Chou, T.T.; Bruce, J.; Schuck, T.; Grossman, M.; Clark, C.M.; et al. Ubiquitinated TDP-43 in frontotemporal lobar degeneration and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Science 2006, 314, 130–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolognesi, B.; Faure, A.J.; Seuma, M.; Schmiedel, J.M.; Tartaglia, G.G.; Lehner, B. The mutational landscape of a prion-like domain. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 4162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adams, M.D.; Celniker, S.E.; Holt, R.A.; Evans, C.A.; Gocayne, J.D.; Amanatides, P.G.; Scherer, S.E.; Li, P.W.; Hoskins, R.A.; Galle, R.F.; et al. The genome sequence of Drosophila melanogaster. Science 2000, 287, 2185–2195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Myers, E.W.; Sutton, G.G.; Delcher, A.L.; Dew, I.M.; Fasulo, D.P.; Flanigan, M.J.; Kravitz, S.A.; Mobarry, C.M.; Reinert, K.H.; Remington, K.A.; et al. A whole-genome assembly of Drosophila. Science 2000, 287, 2196–2204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

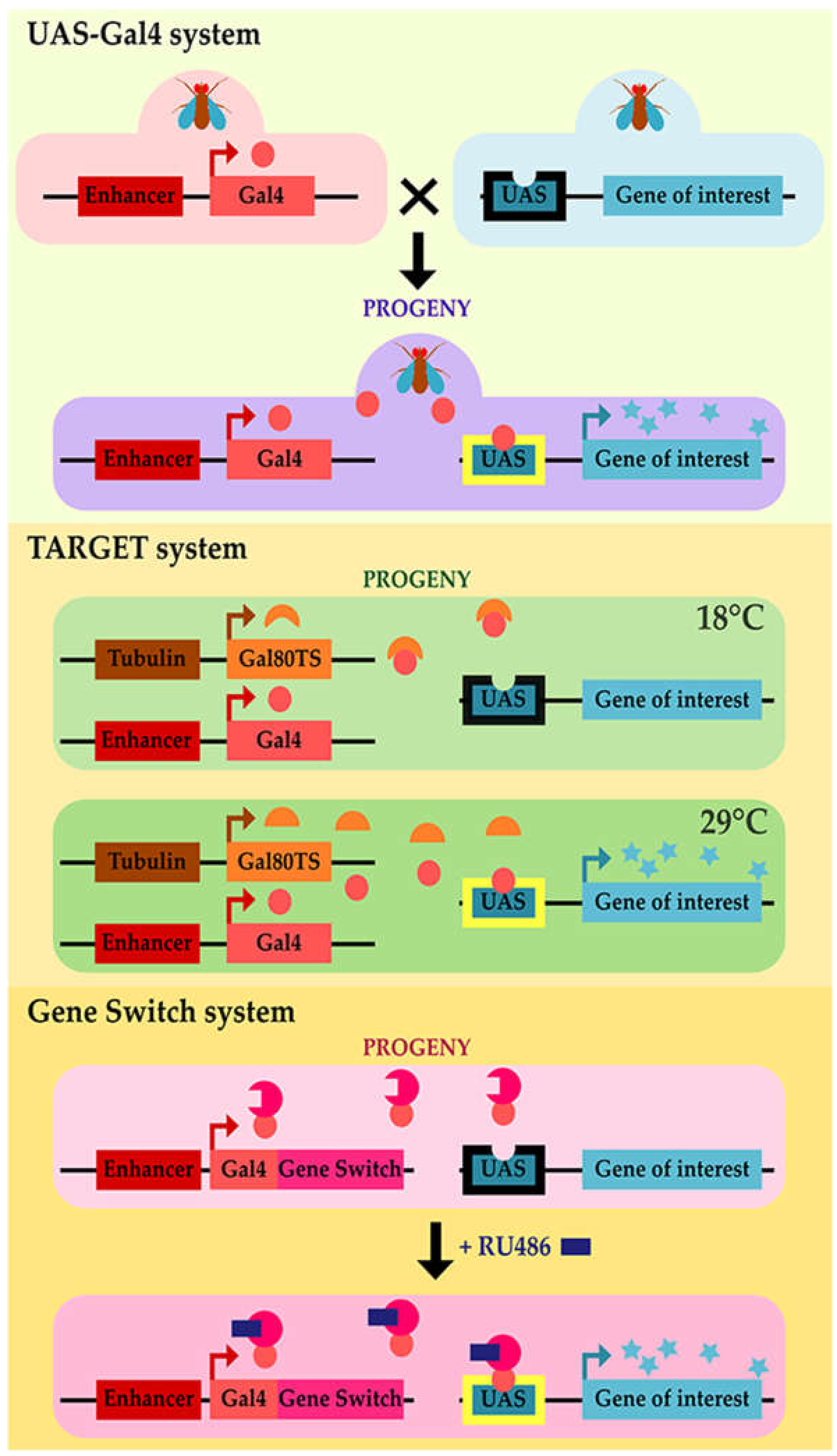

- Brand, A.H.; Perrimon, N. Targeted gene expression as a means of altering cell fates and generating dominant phenotypes. Development (Cambridge, UK) 1993, 118, 401–415. [Google Scholar]

- McGuire, S.E.; Mao, Z.; Davis, R.L. Spatiotemporal gene expression targeting with the TARGET and gene-switch systems in Drosophila. Sci. STKE 2004, 2004, pl6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiter, L.T.; Potocki, L.; Chien, S.; Gribskov, M.; Bier, E. A systematic analysis of human disease-associated gene sequences in Drosophila melanogaster. Genome Res. 2001, 11, 1114–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd, T.E.; Verstreken, P.; Ostrin, E.J.; Phillippi, A.; Lichtarge, O.; Bellen, H.J. A genome-wide search for synaptic vesicle cycle proteins in Drosophila. Neuron 2000, 26, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, J.L.; Thompson, L.M. Drosophila in the study of neurodegenerative disease. Neuron 2006, 52, 169–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGurk, L.; Berson, A.; Bonini, N.M. Drosophila as an In Vivo Model for Human Neurodegenerative Disease. Genetics 2015, 201, 377–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şentürk, M.; Bellen, H.J. Genetic strategies to tackle neurological diseases in fruit flies. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2018, 50, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harman, D. The aging process. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1981, 78, 7124–7128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harman, D. Aging: A theory based on free radical and radiation chemistry. J. Gerontol. 1956, 11, 298–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harman, D. Role of free radicals in mutation, cancer, aging, and the maintenance of life. Radiat. Res. 1962, 16, 753–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harman, D. Nutritional implications of the free-radical theory of aging. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 1982, 1, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harman, D. The aging process. Basic Life Sci. 1988, 49, 1057–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harman, D. Aging: Overview. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2001, 928, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seto, N.O.; Hayashi, S.; Tener, G.M. Cloning, sequence analysis and chromosomal localization of the Cu-Zn superoxide dismutase gene of Drosophila melanogaster. Gene 1989, 75, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, J.P.; Campbell, S.D.; Michaud, D.; Charbonneau, M.; Hilliker, A.J. Null mutation of copper/zinc superoxide dismutase in Drosophila confers hypersensitivity to paraquat and reduced longevity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1989, 86, 2761–2765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, J.P.; Tainer, J.A.; Getzoff, E.D.; Boulianne, G.L.; Kirby, K.; Hilliker, A.J. Subunit-destabilizing mutations in Drosophila copper/zinc superoxide dismutase: Neuropathology and a model of dimer dysequilibrium. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1995, 92, 8574–8578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staveley, B.E.; Phillips, J.P.; Hilliker, A.J. Phenotypic consequences of copper-zinc superoxide dismutase overexpression in Drosophila melanogaster. Genome 1990, 33, 867–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orr, W.C.; Sohal, R.S. Effects of Cu-Zn superoxide dismutase overexpression of life span and resistance to oxidative stress in transgenic Drosophila melanogaster. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1993, 301, 34–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reveillaud, I.; Niedzwiecki, A.; Bensch, K.G.; Fleming, J.E. Expression of bovine superoxide dismutase in Drosophila melanogaster augments resistance of oxidative stress. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1991, 11, 632–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Elia, A.J.; Parkes, T.L.; Kirby, K.; St George-Hyslop, P.; Boulianne, G.L.; Phillips, J.P.; Hilliker, A.J. Expression of human FALS SOD in motorneurons of Drosophila. Free radic. Biol. Med. 1999, 26, 1332–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkes, T.L.; Elia, A.J.; Dickinson, D.; Hilliker, A.J.; Phillips, J.P.; Boulianne, G.L. Extension of Drosophila lifespan by overexpression of human SOD1 in motorneurons. Nat. Genet. 1998, 19, 171–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mockett, R.J.; Radyuk, S.N.; Benes, J.J.; Orr, W.C.; Sohal, R.S. Phenotypic effects of familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis mutant Sod alleles in transgenic Drosophila. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 301–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şahin, A.; Held, A.; Bredvik, K.; Major, P.; Achilli, T.M.; Kerson, A.G.; Wharton, K.; Stilwell, G.; Reenan, R. Human SOD1 ALS Mutations in a Drosophila Knock-In Model Cause Severe Phenotypes and Reveal Dosage-Sensitive Gain- and Loss-of-Function Components. Genetics 2017, 205, 707–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Held, A.; Major, P.; Sahin, A.; Reenan, R.A.; Lipscombe, D.; Wharton, K.A. Circuit Dysfunction in SOD1-ALS Model First Detected in Sensory Feedback Prior to Motor Neuron Degeneration Is Alleviated by BMP Signaling. J. Neurosci. 2019, 39, 2347–2364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard, E.; Pegat, A.; Svahn, J.; Bouhour, F.; Leblanc, P.; Millecamps, S.; Thobois, S.; Guissart, C.; Lumbroso, S.; Mouzat, K. Clinical and Molecular Landscape of ALS Patients with SOD1 Mutations: Novel Pathogenic Variants and Novel Phenotypes. A Single ALS Center Study. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 6807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yim, M.B.; Kang, J.H.; Yim, H.S.; Kwak, H.S.; Chock, P.B.; Stadtman, E.R. A gain-of-function of an amyotrophic lateral sclerosis-associated Cu,Zn-superoxide dismutase mutant: An enhancement of free radical formation due to a decrease in Km for hydrogen peroxide. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1996, 93, 5709–5714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezzi, S.A.; Urushitani, M.; Julien, J.P. Wild-type superoxide dismutase acquires binding and toxic properties of ALS-linked mutant forms through oxidation. J. Neurochem. 2007, 102, 170–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reaume, A.G.; Elliott, J.L.; Hoffman, E.K.; Kowall, N.W.; Ferrante, R.J.; Siwek, D.F.; Wilcox, H.M.; Flood, D.G.; Beal, M.F.; Brown, R.H., Jr.; et al. Motor neurons in Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase-deficient mice develop normally but exhibit enhanced cell death after axonal injury. Nat. Genet. 1996, 13, 43–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruijn, L.I.; Houseweart, M.K.; Kato, S.; Anderson, K.L.; Anderson, S.D.; Ohama, E.; Reaume, A.G.; Scott, R.W.; Cleveland, D.W. Aggregation and motor neuron toxicity of an ALS-linked SOD1 mutant independent from wild-type SOD1. Science (New York, NY) 1998, 281, 1851–1854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciechanover, A.; Kwon, Y.T. Degradation of misfolded proteins in neurodegenerative diseases: Therapeutic targets and strategies. Exp. Mol. Med. 2015, 47, e147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciryam, P.; Lambert-Smith, I.A.; Bean, D.M.; Freer, R.; Cid, F.; Tartaglia, G.G.; Saunders, D.N.; Wilson, M.R.; Oliver, S.G.; Morimoto, R.I.; et al. Spinal motor neuron protein supersaturation patterns are associated with inclusion body formation in ALS. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, E3935–E3943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durham, H.D.; Roy, J.; Dong, L.; Figlewicz, D.A. Aggregation of mutant Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase proteins in a culture model of ALS. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 1997, 56, 523–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrawell, N.E.; Lambert-Smith, I.A.; Warraich, S.T.; Blair, I.P.; Saunders, D.N.; Hatters, D.M.; Yerbury, J.J. Distinct partitioning of ALS associated TDP-43, FUS and SOD1 mutants into cellular inclusions. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 13416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, J.A.; Dalton, M.J.; Gurney, M.E.; Kopito, R.R. Formation of high molecular weight complexes of mutant Cu, Zn-superoxide dismutase in a mouse model for familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2000, 97, 12571–12576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Kim, H.J. Prion-like Mechanism in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis: Are Protein Aggregates the Key? Exp. Neurobiol. 2015, 24, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinder, G.A.; Lacourse, M.C.; Minotti, S.; Durham, H.D. Mutant Cu/Zn-superoxide dismutase proteins have altered solubility and interact with heat shock/stress proteins in models of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 12791–12796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverman, J.M.; Fernando, S.M.; Grad, L.I.; Hill, A.F.; Turner, B.J.; Yerbury, J.J.; Cashman, N.R. Disease Mechanisms in ALS: Misfolded SOD1 Transferred Through Exosome-Dependent and Exosome-Independent Pathways. Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 2016, 36, 377–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Xu, G.; Borchelt, D.R. High molecular weight complexes of mutant superoxide dismutase 1: Age-dependent and tissue-specific accumulation. Neurobiol. Dis. 2002, 9, 139–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Xu, G.; Gonzales, V.; Coonfield, M.; Fromholt, D.; Copeland, N.G.; Jenkins, N.A.; Borchelt, D.R. Fibrillar inclusions and motor neuron degeneration in transgenic mice expressing superoxide dismutase 1 with a disrupted copper-binding site. Neurobiol. Dis. 2002, 10, 128–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watson, M.R.; Lagow, R.D.; Xu, K.; Zhang, B.; Bonini, N.M. A drosophila model for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis reveals motor neuron damage by human SOD1. J. Biol. Chem. 2008, 283, 24972–24981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, C.; Liang, W.; Wang, H.; Yang, Y.; Wang, T.; Wang, S.; Wang, X.; Wang, Y.; Feng, H. γ-Oryzanol mitigates oxidative stress and prevents mutant SOD1-Related neurotoxicity in Drosophila and cell models of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neuropharmacology 2019, 160, 107777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, R.; Kumimoto, E.L.; Bao, H.; Zhang, B. ALS-linked SOD1 in glial cells enhances ß-N-Methylamino L-Alanine (BMAA)-induced toxicity in Drosophila. F1000Research 2012, 1, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallart-Palau, X.; Ng, C.H.; Ribera, J.; Sze, S.K.; Lim, K.L. Drosophila expressing human SOD1 successfully recapitulates mitochondrial phenotypic features of familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neurosci. Lett. 2016, 624, 47–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Y.H.; Parsadanian, A.S.; Andreeva, A.; Snider, W.D.; Elliott, J.L. Restricted expression of G86R Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase in astrocytes results in astrocytosis but does not cause motoneuron degeneration. J. Neurosci. 2000, 20, 660–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lino, M.M.; Schneider, C.; Caroni, P. Accumulation of SOD1 mutants in postnatal motoneurons does not cause motoneuron pathology or motoneuron disease. J. Neurosci. 2002, 22, 4825–4832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pramatarova, A.; Laganière, J.; Roussel, J.; Brisebois, K.; Rouleau, G.A. Neuron-specific expression of mutant superoxide dismutase 1 in transgenic mice does not lead to motor impairment. J. Neurosci. 2001, 21, 3369–3374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto, G.; Stojanovic, A.; Holmberg, C.I.; Kim, S.; Morimoto, R.I. Structural properties and neuronal toxicity of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis-associated Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase 1 aggregates. J. Cell Biol. 2005, 171, 75–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stathopulos, P.B.; Rumfeldt, J.A.; Scholz, G.A.; Irani, R.A.; Frey, H.E.; Hallewell, R.A.; Lepock, J.R.; Meiering, E.M. Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase mutants associated with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis show enhanced formation of aggregates in vitro. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 7021–7026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pickles, S.; Vande Velde, C. Misfolded SOD1 and ALS: Zeroing in on mitochondria. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: Official publication of the World Federation of Neurology Research Group on Motor Neuron Diseases. Amyotroph. Lateral Scler. 2012, 13, 333–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sábado, J.; Casanovas, A.; Hernández, S.; Piedrafita, L.; Hereu, M.; Esquerda, J.E. Immunodetection of disease-associated conformers of mutant cu/zn superoxide dismutase 1 selectively expressed in degenerating neurons in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2013, 72, 646–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hetz, C.; Martinon, F.; Rodriguez, D.; Glimcher, L.H. The unfolded protein response: Integrating stress signals through the stress sensor IRE1α. Physiol. Rev. 2011, 91, 1219–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaronen, M.; Vehviläinen, P.; Malm, T.; Keksa-Goldsteine, V.; Pollari, E.; Valonen, P.; Koistinaho, J.; Goldsteins, G. Protein disulfide isomerase in ALS mouse glia links protein misfolding with NADPH oxidase-catalyzed superoxide production. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2013, 22, 646–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishitoh, H.; Matsuzawa, A.; Tobiume, K.; Saegusa, K.; Takeda, K.; Inoue, K.; Hori, S.; Kakizuka, A.; Ichijo, H. ASK1 is essential for endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced neuronal cell death triggered by expanded polyglutamine repeats. Genes Dev. 2002, 16, 1345–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, P.; Ron, D. The unfolded protein response: From stress pathway to homeostatic regulation. Science (New York, NY) 2011, 334, 1081–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalmar, B.; Greensmith, L. Cellular Chaperones as Therapeutic Targets in ALS to Restore Protein Homeostasis and Improve Cellular Function. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2017, 10, 251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, W.; Kunkler, P.E.; Harding, H.P.; Ron, D.; Kraig, R.P.; Popko, B. Enhanced integrated stress response promotes myelinating oligodendrocyte survival in response to interferon-gamma. Am. J. Pathol. 2008, 173, 1508–1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, W.; Lin, Y.; Li, J.; Fenstermaker, A.G.; Way, S.W.; Clayton, B.; Jamison, S.; Harding, H.P.; Ron, D.; Popko, B. Oligodendrocyte-specific activation of PERK signaling protects mice against experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J. Neurosci. 2013, 33, 5980–5991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valenzuela, V.; Collyer, E.; Armentano, D.; Parsons, G.B.; Court, F.A.; Hetz, C. Activation of the unfolded protein response enhances motor recovery after spinal cord injury. Cell Death Dis. 2012, 3, e272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gifondorwa, D.J.; Robinson, M.B.; Hayes, C.D.; Taylor, A.R.; Prevette, D.M.; Oppenheim, R.W.; Caress, J.; Milligan, C.E. Exogenous delivery of heat shock protein 70 increases lifespan in a mouse model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J. Neurosci. 2007, 27, 13173–13180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spencer, P.S.; Nunn, P.B.; Hugon, J.; Ludolph, A.C.; Ross, S.M.; Roy, D.N.; Robertson, R.C. Guam amyotrophic lateral sclerosis-parkinsonism-dementia linked to a plant excitant neurotoxin. Science 1987, 237, 517–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilieva, H.; Polymenidou, M.; Cleveland, D.W. Non-cell autonomous toxicity in neurodegenerative disorders: ALS and beyond. J. Cell Biol. 2009, 187, 761–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trotti, D.; Danbolt, N.C.; Volterra, A. Glutamate transporters are oxidant-vulnerable: A molecular link between oxidative and excitotoxic neurodegeneration? Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 1998, 19, 328–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorąca, A.; Huk-Kolega, H.; Piechota, A.; Kleniewska, P.; Ciejka, E.; Skibska, B. Lipoic acid—biological activity and therapeutic potential. Pharmacol. Rep. 2011, 63, 849–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Cheng, J.; Wang, S.; Wang, X.; Jiang, H.; Yang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Liang, W.; Feng, H. α-Lipoic acid attenuates oxidative stress and neurotoxicity via the ERK/Akt-dependent pathway in the mutant hSOD1 related Drosophila model and the NSC34 cell line of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Brain Res. Bull. 2018, 140, 299–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juliano, C.; Cossu, M.; Alamanni, M.C.; Piu, L. Antioxidant activity of gamma-oryzanol: Mechanism of action and its effect on oxidative stability of pharmaceutical oils. Int. J. Pharm. 2005, 299, 146–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Mossevelde, S.; van der Zee, J.; Cruts, M.; van Broeckhoven, C. Relationship between C9orf72 repeat size and clinical phenotype. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2017, 44, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belzil, V.V.; Bauer, P.O.; Prudencio, M.; Gendron, T.F.; Stetler, C.T.; Yan, I.K.; Pregent, L.; Daughrity, L.; Baker, M.C.; Rademakers, R.; et al. Reduced C9orf72 gene expression in c9FTD/ALS is caused by histone trimethylation, an epigenetic event detectable in blood. Acta Neuropathol. 2013, 126, 895–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frick, P.; Sellier, C.; Mackenzie, I.R.A.; Cheng, C.Y.; Tahraoui-Bories, J.; Martinat, C.; Pasterkamp, R.J.; Prudlo, J.; Edbauer, D.; Oulad-Abdelghani, M.; et al. Novel antibodies reveal presynaptic localization of C9orf72 protein and reduced protein levels in C9orf72 mutation carriers. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2018, 6, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waite, A.J.; Bäumer, D.; East, S.; Neal, J.; Morris, H.R.; Ansorge, O.; Blake, D.J. Reduced C9orf72 protein levels in frontal cortex of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and frontotemporal degeneration brain with the C9ORF72 hexanucleotide repeat expansion. Neurobiol. Aging 2014, 35, 1779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciura, S.; Lattante, S.; Le Ber, I.; Latouche, M.; Tostivint, H.; Brice, A.; Kabashi, E. Loss of function of C9orf72 causes motor deficits in a zebrafish model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Ann. Neurol. 2013, 74, 180–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Therrien, M.; Rouleau, G.A.; Dion, P.A.; Parker, J.A. Deletion of C9ORF72 results in motor neuron degeneration and stress sensitivity in C. elegans. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e83450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Rourke, J.G.; Bogdanik, L.; Yáñez, A.; Lall, D.; Wolf, A.J.; Muhammad, A.K.; Ho, R.; Carmona, S.; Vit, J.P.; Zarrow, J.; et al. C9orf72 is required for proper macrophage and microglial function in mice. Science (New York, NY) 2016, 351, 1324–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Q.; Jiang, J.; Gendron, T.F.; McAlonis-Downes, M.; Jiang, L.; Taylor, A.; Diaz Garcia, S.; Ghosh Dastidar, S.; Rodriguez, M.J.; King, P.; et al. Reduced C9ORF72 function exacerbates gain of toxicity from ALS/FTD-causing repeat expansion in C9orf72. Nat. Neurosci. 2020, 23, 615–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iyer, S.; Acharya, K.R.; Subramanian, V. A comparative bioinformatic analysis of C9orf72. PeerJ 2018, 6, e4391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gendron, T.F.; Bieniek, K.F.; Zhang, Y.J.; Jansen-West, K.; Ash, P.E.; Caulfield, T.; Daughrity, L.; Dunmore, J.H.; Castanedes-Casey, M.; Chew, J.; et al. Antisense transcripts of the expanded C9ORF72 hexanucleotide repeat form nuclear RNA foci and undergo repeat-associated non-ATG translation in c9FTD/ALS. Acta Neuropathol. 2013, 126, 829–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, L.D.; Prudencio, M.; Kramer, N.J.; Martinez-Ramirez, L.F.; Srinivasan, A.R.; Lan, M.; Parisi, M.J.; Zhu, Y.; Chew, J.; Cook, C.N.; et al. Toxic expanded GGGGCC repeat transcription is mediated by the PAF1 complex in C9orf72-associated FTD. Nat. Neurosci. 2019, 22, 863–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramer, N.J.; Carlomagno, Y.; Zhang, Y.J.; Almeida, S.; Cook, C.N.; Gendron, T.F.; Prudencio, M.; van Blitterswijk, M.; Belzil, V.; Couthouis, J.; et al. Spt4 selectively regulates the expression of C9orf72 sense and antisense mutant transcripts. Science (New York, NY) 2016, 353, 708–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Z.; Poidevin, M.; Li, X.; Li, Y.; Shu, L.; Nelson, D.L.; Li, H.; Hales, C.M.; Gearing, M.; Wingo, T.S.; et al. Expanded GGGGCC repeat RNA associated with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and frontotemporal dementia causes neurodegeneration. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 7778–7783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanai, Y.; Dohmae, N.; Hirokawa, N. Kinesin transports RNA: Isolation and characterization of an RNA-transporting granule. Neuron 2004, 43, 513–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Celona, B.; Dollen, J.V.; Vatsavayai, S.C.; Kashima, R.; Johnson, J.R.; Tang, A.A.; Hata, A.; Miller, B.L.; Huang, E.J.; Krogan, N.J.; et al. Suppression of C9orf72 RNA repeat-induced neurotoxicity by the ALS-associated RNA-binding protein Zfp106. eLife 2017, 6, e19032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, K.; Donnelly, C.J.; Haeusler, A.R.; Grima, J.C.; Machamer, J.B.; Steinwald, P.; Daley, E.L.; Miller, S.J.; Cunningham, K.M.; Vidensky, S.; et al. The C9orf72 repeat expansion disrupts nucleocytoplasmic transport. Nature 2015, 525, 56–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burguete, A.S.; Almeida, S.; Gao, F.B.; Kalb, R.; Akins, M.R.; Bonini, N.M. GGGGCC microsatellite RNA is neuritically localized, induces branching defects, and perturbs transport granule function. eLife 2015, 4, e08881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tran, H.; Almeida, S.; Moore, J.; Gendron, T.F.; Chalasani, U.; Lu, Y.; Du, X.; Nickerson, J.A.; Petrucelli, L.; Weng, Z.; et al. Differential Toxicity of Nuclear RNA Foci versus Dipeptide Repeat Proteins in a Drosophila Model of C9ORF72 FTD/ALS. Neuron 2015, 87, 1207–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moens, T.G.; Mizielinska, S.; Niccoli, T.; Mitchell, J.S.; Thoeng, A.; Ridler, C.E.; Grönke, S.; Esser, J.; Heslegrave, A.; Zetterberg, H.; et al. Sense and antisense RNA are not toxic in Drosophila models of C9orf72-associated ALS/FTD. Acta Neuropathol. 2018, 135, 445–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mori, K.; Arzberger, T.; Grässer, F.A.; Gijselinck, I.; May, S.; Rentzsch, K.; Weng, S.M.; Schludi, M.H.; van der Zee, J.; Cruts, M.; et al. Bidirectional transcripts of the expanded C9orf72 hexanucleotide repeat are translated into aggregating dipeptide repeat proteins. Acta Neuropathol. 2013, 126, 881–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mori, K.; Weng, S.M.; Arzberger, T.; May, S.; Rentzsch, K.; Kremmer, E.; Schmid, B.; Kretzschmar, H.A.; Cruts, M.; van Broeckhoven, C.; et al. The C9orf72 GGGGCC repeat is translated into aggregating dipeptide-repeat proteins in FTLD/ALS. Science 2013, 339, 1335–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizielinska, S.; Grönke, S.; Niccoli, T.; Ridler, C.E.; Clayton, E.L.; Devoy, A.; Moens, T.; Norona, F.E.; Woollacott, I.O.C.; Pietrzyk, J.; et al. C9orf72 repeat expansions cause neurodegeneration in Drosophila through arginine-rich proteins. Science (New York, NY) 2014, 345, 1192–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, X.; Tan, W.; Westergard, T.; Krishnamurthy, K.; Markandaiah, S.S.; Shi, Y.; Lin, S.; Shneider, N.A.; Monaghan, J.; Pandey, U.B.; et al. Antisense proline-arginine RAN dipeptides linked to C9ORF72-ALS/FTD form toxic nuclear aggregates that initiate in vitro and in vivo neuronal death. Neuron 2014, 84, 1213–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freibaum, B.D.; Lu, Y.; Lopez-Gonzalez, R.; Kim, N.C.; Almeida, S.; Lee, K.H.; Badders, N.; Valentine, M.; Miller, B.L.; Wong, P.C.; et al. GGGGCC repeat expansion in C9orf72 compromises nucleocytoplasmic transport. Nature 2015, 525, 129–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, K.H.; Zhang, P.; Kim, H.J.; Mitrea, D.M.; Sarkar, M.; Freibaum, B.D.; Cika, J.; Coughlin, M.; Messing, J.; Molliex, A.; et al. C9orf72 Dipeptide Repeats Impair the Assembly, Dynamics, and Function of Membrane-Less Organelles. Cell 2016, 167, 774–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perry, S.; Han, Y.; Das, A.; Dickman, D. Homeostatic plasticity can be induced and expressed to restore synaptic strength at neuromuscular junctions undergoing ALS-related degeneration. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2017, 26, 4153–4167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, D.; Abdallah, A.; Li, Z.; Lu, Y.; Almeida, S.; Gao, F.B. FTD/ALS-associated poly(GR) protein impairs the Notch pathway and is recruited by poly(GA) into cytoplasmic inclusions. Acta Neuropathol. 2015, 130, 525–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morón-Oset, J.; Supèr, T.; Esser, J.; Isaacs, A.M.; Grönke, S.; Partridge, L. Glycine-alanine dipeptide repeats spread rapidly in a repeat length- and age-dependent manner in the fly brain. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2019, 7, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boeynaems, S.; Bogaert, E.; Michiels, E.; Gijselinck, I.; Sieben, A.; Jovičić, A.; de Baets, G.; Scheveneels, W.; Steyaert, J.; Cuijt, I.; et al. Drosophila screen connects nuclear transport genes to DPR pathology in c9ALS/FTD. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 20877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moens, T.G.; Niccoli, T.; Wilson, K.M.; Atilano, M.L.; Birsa, N.; Gittings, L.M.; Holbling, B.V.; Dyson, M.C.; Thoeng, A.; Neeves, J.; et al. C9orf72 arginine-rich dipeptide proteins interact with ribosomal proteins in vivo to induce a toxic translational arrest that is rescued by eIF1A. Acta Neuropathol. 2019, 137, 487–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Wu, Z.; Li, Y.; Tantray, I.; de Stefani, D.; Mattarei, A.; Krishnan, G.; Gao, F.B.; Vogel, H.; Lu, B. Altered MICOS Morphology and Mitochondrial Ion Homeostasis Contribute to Poly(GR) Toxicity Associated with C9-ALS/FTD. Cell Rep. 2020, 32, 107989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simone, R.; Balendra, R.; Moens, T.G.; Preza, E.; Wilson, K.M.; Heslegrave, A.; Woodling, N.S.; Niccoli, T.; Gilbert-Jaramillo, J.; Abdelkarim, S.; et al. G-quadruplex-binding small molecules ameliorate C9orf72 FTD/ALS pathology in vitro and in vivo. EMBO Mol. Med. 2018, 10, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andersson, M.K.; Ståhlberg, A.; Arvidsson, Y.; Olofsson, A.; Semb, H.; Stenman, G.; Nilsson, O.; Aman, P. The multifunctional FUS, EWS and TAF15 proto-oncoproteins show cell type-specific expression patterns and involvement in cell spreading and stress response. BMC Cell Biol. 2008, 9, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guerrero, E.N.; Wang, H.; Mitra, J.; Hegde, P.M.; Stowell, S.E.; Liachko, N.F.; Kraemer, B.C.; Garruto, R.M.; Rao, K.S.; Hegde, M.L. TDP-43/FUS in motor neuron disease: Complexity and challenges. Prog. Neurobiol. 2016, 145–146, 78–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, C.; Zhou, H.; Tong, J.; Chen, H.; Liu, Y.J.; Wang, D.; Wei, X.; Xia, X.G. FUS transgenic rats develop the phenotypes of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and frontotemporal lobar degeneration. PLoS Genet. 2011, 7, e1002011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naumann, M.; Pal, A.; Goswami, A.; Lojewski, X.; Japtok, J.; Vehlow, A.; Naujock, M.; Günther, R.; Jin, M.; Stanslowsky, N.; et al. Impaired DNA damage response signaling by FUS-NLS mutations leads to neurodegeneration and FUS aggregate formation. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagier-Tourenne, C.; Polymenidou, M.; Hutt, K.R.; Vu, A.Q.; Baughn, M.; Huelga, S.C.; Clutario, K.M.; Ling, S.C.; Liang, T.Y.; Mazur, C.; et al. Divergent roles of ALS-linked proteins FUS/TLS and TDP-43 intersect in processing long pre-mRNAs. Nat. Neurosci. 2012, 15, 1488–1497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogelj, B.; Easton, L.E.; Bogu, G.K.; Stanton, L.W.; Rot, G.; Curk, T.; Zupan, B.; Sugimoto, Y.; Modic, M.; Haberman, N.; et al. Widespread binding of FUS along nascent RNA regulates alternative splicing in the brain. Sci. Rep. 2012, 2, 603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, A.Y.; Manley, J.L. TLS inhibits RNA polymerase III transcription. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2010, 30, 186–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uranishi, H.; Tetsuka, T.; Yamashita, M.; Asamitsu, K.; Shimizu, M.; Itoh, M.; Okamoto, T. Involvement of the pro-oncoprotein TLS (translocated in liposarcoma) in nuclear factor-kappa B p65-mediated transcription as a coactivator. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 13395–13401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zinszner, H.; Sok, J.; Immanuel, D.; Yin, Y.; Ron, D. TLS (FUS) binds RNA in vivo and engages in nucleo-cytoplasmic shuttling. J. Cell Sci. 1997, 110 Pt 15, 1741–1750. [Google Scholar]

- Lagier-Tourenne, C.; Cleveland, D.W. Rethinking ALS: The FUS about TDP-43. Cell 2009, 136, 1001–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Da Cruz, S.; Cleveland, D.W. Understanding the role of TDP-43 and FUS/TLS in ALS and beyond. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2011, 21, 904–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corrado, L.; Del Bo, R.; Castellotti, B.; Ratti, A.; Cereda, C.; Penco, S.; Sorarù, G.; Carlomagno, Y.; Ghezzi, S.; Pensato, V.; et al. Mutations of FUS gene in sporadic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J. Med. Genet. 2010, 47, 190–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dormann, D.; Rodde, R.; Edbauer, D.; Bentmann, E.; Fischer, I.; Hruscha, A.; Than, M.E.; Mackenzie, I.R.; Capell, A.; Schmid, B.; et al. ALS-associated fused in sarcoma (FUS) mutations disrupt Transportin-mediated nuclear import. EMBO J. 2010, 29, 2841–2857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dini Modigliani, S.; Morlando, M.; Errichelli, L.; Sabatelli, M.; Bozzoni, I. An ALS-associated mutation in the FUS 3’-UTR disrupts a microRNA-FUS regulatory circuitry. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 4335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabatelli, M.; Moncada, A.; Conte, A.; Lattante, S.; Marangi, G.; Luigetti, M.; Lucchini, M.; Mirabella, M.; Romano, A.; Del Grande, A.; et al. Mutations in the 3’ untranslated region of FUS causing FUS overexpression are associated with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2013, 22, 4748–4755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Yang, M.; Deng, J.; Chen, X.; Ye, Y.; Zhu, L.; Liu, J.; Ye, H.; Shen, Y.; Li, Y.; et al. Expression of human FUS protein in Drosophila leads to progressive neurodegeneration. Protein Cell 2011, 2, 477–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabashi, E.; Bercier, V.; Lissouba, A.; Liao, M.; Brustein, E.; Rouleau, G.A.; Drapeau, P. FUS and TARDBP but not SOD1 interact in genetic models of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. PLoS Genet. 2011, 7, e1002214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murakami, T.; Qamar, S.; Lin, J.Q.; Schierle, G.S.; Rees, E.; Miyashita, A.; Costa, A.R.; Dodd, R.B.; Chan, F.T.; Michel, C.H.; et al. ALS/FTD Mutation-Induced Phase Transition of FUS Liquid Droplets and Reversible Hydrogels into Irreversible Hydrogels Impairs RNP Granule Function. Neuron 2015, 88, 678–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasayama, H.; Shimamura, M.; Tokuda, T.; Azuma, Y.; Yoshida, T.; Mizuno, T.; Nakagawa, M.; Fujikake, N.; Nagai, Y.; Yamaguchi, M. Knockdown of the Drosophila fused in sarcoma (FUS) homologue causes deficient locomotive behavior and shortening of motoneuron terminal branches. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e39483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Liu, S.; Liu, G.; Oztürk, A.; Hicks, G.G. ALS-associated FUS mutations result in compromised FUS alternative splicing and autoregulation. PLoS Genet. 2013, 9, e1003895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bosco, D.A.; Lemay, N.; Ko, H.K.; Zhou, H.; Burke, C.; Kwiatkowski, T.J., Jr.; Sapp, P.; McKenna-Yasek, D.; Brown, R.H., Jr.; Hayward, L.J. Mutant FUS proteins that cause amyotrophic lateral sclerosis incorporate into stress granules. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2010, 19, 4160–4175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.R.; King, O.D.; Shorter, J.; Gitler, A.D. Stress granules as crucibles of ALS pathogenesis. J. Cell Biol. 2013, 201, 361–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Z.; Diaz, Z.; Fang, X.; Hart, M.P.; Chesi, A.; Shorter, J.; Gitler, A.D. Molecular determinants and genetic modifiers of aggregation and toxicity for the ALS disease protein FUS/TLS. PLoS Biol. 2011, 9, e1000614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bourefis, A.R.; Campanari, M.L.; Buee-Scherrer, V.; Kabashi, E. Functional characterization of a FUS mutant zebrafish line as a novel genetic model for ALS. Neurobiol. Dis. 2020, 142, 104935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jackson, K.L.; Dhaibar, H.A.; Dayton, R.D.; Cananzi, S.G.; Mayhan, W.G.; Glasscock, E.; Klein, R.L. Severe respiratory changes at end stage in a FUS-induced disease state in adult rats. BMC Neurosci. 2016, 17, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Lyashchenko, A.K.; Lu, L.; Nasrabady, S.E.; Elmaleh, M.; Mendelsohn, M.; Nemes, A.; Tapia, J.C.; Mentis, G.Z.; Shneider, N.A. ALS-associated mutant FUS induces selective motor neuron degeneration through toxic gain of function. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 10465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanson, N.A., Jr.; Maltare, A.; King, H.; Smith, R.; Kim, J.H.; Taylor, J.P.; Lloyd, T.E.; Pandey, U.B. A Drosophila model of FUS-related neurodegeneration reveals genetic interaction between FUS and TDP-43. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2011, 20, 2510–2523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.W.; Brent, J.R.; Tomlinson, A.; Shneider, N.A.; McCabe, B.D. The ALS-associated proteins FUS and TDP-43 function together to affect Drosophila locomotion and life span. J. Clin. Investig. 2011, 121, 4118–4126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, R.; Liu, Y.; Yang, L.; Gal, J.; Zhu, H.; Jia, J. Motor neuron apoptosis and neuromuscular junction perturbation are prominent features in a Drosophila model of Fus-mediated ALS. Mol. Neurodegener. 2012, 7, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogaert, E.; Boeynaems, S.; Kato, M.; Guo, L.; Caulfield, T.R.; Steyaert, J.; Scheveneels, W.; Wilmans, N.; Haeck, W.; Hersmus, N.; et al. Molecular Dissection of FUS Points at Synergistic Effect of Low-Complexity Domains in Toxicity. Cell Rep. 2018, 24, 529–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miguel, L.; Avequin, T.; Delarue, M.; Feuillette, S.; Frébourg, T.; Campion, D.; Lecourtois, M. Accumulation of insoluble forms of FUS protein correlates with toxicity in Drosophila. Neurobiol. Aging 2012, 33, 1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, J.; Yang, M.; Chen, Y.; Chen, X.; Liu, J.; Sun, S.; Cheng, H.; Li, Y.; Bigio, E.H.; Mesulam, M.; et al. FUS Interacts with HSP60 to Promote Mitochondrial Damage. PLoS Genet. 2015, 11, e1005357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jäckel, S.; Summerer, A.K.; Thömmes, C.M.; Pan, X.; Voigt, A.; Schulz, J.B.; Rasse, T.M.; Dormann, D.; Haass, C.; Kahle, P.J. Nuclear import factor transportin and arginine methyltransferase 1 modify FUS neurotoxicity in Drosophila. Neurobiol. Dis. 2015, 74, 76–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daigle, J.G.; Lanson, N.A., Jr.; Smith, R.B.; Casci, I.; Maltare, A.; Monaghan, J.; Nichols, C.D.; Kryndushkin, D.; Shewmaker, F.; Pandey, U.B. RNA-binding ability of FUS regulates neurodegeneration, cytoplasmic mislocalization and incorporation into stress granules associated with FUS carrying ALS-linked mutations. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2013, 22, 1193–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steyaert, J.; Scheveneels, W.; Vanneste, J.; van Damme, P.; Robberecht, W.; Callaerts, P.; Bogaert, E.; van den Bosch, L. FUS-induced neurotoxicity in Drosophila is prevented by downregulating nucleocytoplasmic transport proteins. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2018, 27, 4103–4116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gogia, N.; Sarkar, A.; Mehta, A.S.; Ramesh, N.; Deshpande, P.; Kango-Singh, M.; Pandey, U.B.; Singh, A. Inactivation of Hippo and cJun-N-terminal Kinase (JNK) signaling mitigate FUS mediated neurodegeneration in vivo. Neurobiol. Dis. 2020, 140, 104837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machamer, J.B.; Collins, S.E.; Lloyd, T.E. The ALS gene FUS regulates synaptic transmission at the Drosophila neuromuscular junction. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2014, 23, 3810–3822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Shahidullah, M.; Le Marchand, S.J.; Fei, H.; Zhang, J.; Pandey, U.B.; Dalva, M.B.; Pasinelli, P.; Levitan, I.B. Defects in synapse structure and function precede motor neuron degeneration in Drosophila models of FUS-related ALS. J. Neurosci. 2013, 33, 19590–19598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, D.; Seki, M.; Tsunoda, Y.; Uchiyama, H.; Suzuki, N. Nuclear transport impairment of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis-linked mutations in FUS/TLS. Ann. Neurol. 2011, 69, 152–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kino, Y.; Washizu, C.; Aquilanti, E.; Okuno, M.; Kurosawa, M.; Yamada, M.; Doi, H.; Nukina, N. Intracellular localization and splicing regulation of FUS/TLS are variably affected by amyotrophic lateral sclerosis-linked mutations. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011, 39, 2781–2798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, B.J.; Cansizoglu, A.E.; Süel, K.E.; Louis, T.H.; Zhang, Z.; Chook, Y.M. Rules for nuclear localization sequence recognition by karyopherin beta 2. Cell 2006, 126, 543–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stolow, D.T.; Haynes, S.R. Cabeza, a Drosophila gene encoding a novel RNA binding protein, shares homology with EWS and TLS, two genes involved in human sarcoma formation. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995, 23, 835–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Xia, Q.; Wang, H.; Hao, Z.; Fu, C.; Hu, Q.; Gao, F.; Ren, H.; Chen, D.; Han, J.; Ying, Z.; et al. TDP-43 loss of function increases TFEB activity and blocks autophagosome-lysosome fusion. EMBO J. 2016, 35, 121–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frickenhaus, M.; Wagner, M.; Mallik, M.; Catinozzi, M.; Storkebaum, E. Highly efficient cell-type-specific gene inactivation reveals a key function for the Drosophila FUS homolog cabeza in neurons. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 9107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimamura, M.; Kyotani, A.; Azuma, Y.; Yoshida, H.; Binh Nguyen, T.; Mizuta, I.; Yoshida, T.; Mizuno, T.; Nakagawa, M.; Tokuda, T.; et al. Genetic link between Cabeza, a Drosophila homologue of Fused in Sarcoma (FUS), and the EGFR signaling pathway. Exp. Cell Res. 2014, 326, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azuma, Y.; Tokuda, T.; Kushimura, Y.; Yamamoto, I.; Mizuta, I.; Mizuno, T.; Nakagawa, M.; Ueyama, M.; Nagai, Y.; Iwasaki, Y.; et al. Hippo, Drosophila MST, is a novel modifier of motor neuron degeneration induced by knockdown of Caz, Drosophila FUS. Exp. Cell Res. 2018, 371, 311–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azuma, Y.; Tokuda, T.; Shimamura, M.; Kyotani, A.; Sasayama, H.; Yoshida, T.; Mizuta, I.; Mizuno, T.; Nakagawa, M.; Fujikake, N.; et al. Identification of ter94, Drosophila VCP, as a strong modulator of motor neuron degeneration induced by knockdown of Caz, Drosophila FUS. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2014, 23, 3467–3480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo Piccolo, L.; Jantrapirom, S.; Nagai, Y.; Yamaguchi, M. FUS toxicity is rescued by the modulation of lncRNA hsrω expression in Drosophila melanogaster. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 15660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakisaka, K.T.; Tanaka, R.; Hirashima, T.; Muraoka, Y.; Azuma, Y.; Yoshida, H.; Tokuda, T.; Asada, S.; Suda, K.; Ichiyanagi, K.; et al. Novel roles of Drosophila FUS and Aub responsible for piRNA biogenesis in neuronal disorders. Brain Res. 2019, 1708, 207–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machamer, J.B.; Woolums, B.M.; Fuller, G.G.; Lloyd, T.E. FUS causes synaptic hyperexcitability in Drosophila dendritic arborization neurons. Brain Res. 2018, 1693, 55–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirano, A.; Nakano, I.; Kurland, L.T.; Mulder, D.W.; Holley, P.W.; Saccomanno, G. Fine structural study of neurofibrillary changes in a family with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 1984, 43, 471–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sasaki, S.; Horie, Y.; Iwata, M. Mitochondrial alterations in dorsal root ganglion cells in sporadic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Acta Neuropathol. 2007, 114, 633–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, E.F.; Shaw, P.J.; de Vos, K.J. The role of mitochondria in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neurosci. Lett. 2019, 710, 132933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altanbyek, V.; Cha, S.J.; Kang, G.U.; Im, D.S.; Lee, S.; Kim, H.J.; Kim, K. Imbalance of mitochondrial dynamics in Drosophila models of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2016, 481, 259–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Deng, J.; Wang, P.; Yang, M.; Chen, X.; Zhu, L.; Liu, J.; Lu, B.; Shen, Y.; Fushimi, K.; et al. PINK1 and Parkin are genetic modifiers for FUS-induced neurodegeneration. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2016, 25, 5059–5068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Mayer, M.P. Gymnastics of molecular chaperones. Mol. Cell 2010, 39, 321–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S. Review: Perinucleolar structures. J. Struct. Biol. 2000, 129, 233–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Y.S.; Zhang, B.; Spector, D.L. Biogenesis and function of nuclear bodies. Trends Genet. 2011, 27, 295–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, F.; Na, I.; Kurgan, L.; Uversky, V.N. Compartmentalization and Functionality of Nuclear Disorder: Intrinsic Disorder and Protein-Protein Interactions in Intra-Nuclear Compartments. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015, 17, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ninomiya, K.; Hirose, T. Short Tandem Repeat-Enriched Architectural RNAs in Nuclear Bodies: Functions and Associated Diseases. Non-Coding RNA 2020, 6, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chujo, T.; Yamazaki, T.; Hirose, T. Architectural RNAs (arcRNAs): A class of long noncoding RNAs that function as the scaffold of nuclear bodies. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2016, 1859, 139–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Q.; Hao, Q.; Prasanth, K.V. Nuclear Long Noncoding RNAs: Key Regulators of Gene Expression. Trends Genet. 2018, 34, 142–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shelkovnikova, T.A.; Robinson, H.K.; Troakes, C.; Ninkina, N.; Buchman, V.L. Compromised paraspeckle formation as a pathogenic factor in FUSopathies. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2014, 23, 2298–2312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jolly, C.; Lakhotia, S.C. Human sat III and Drosophila hsr omega transcripts: A common paradigm for regulation of nuclear RNA processing in stressed cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006, 34, 5508–5514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onorati, M.C.; Lazzaro, S.; Mallik, M.; Ingrassia, A.M.; Carreca, A.P.; Singh, A.K.; Chaturvedi, D.P.; Lakhotia, S.C.; Corona, D.F. The ISWI chromatin remodeler organizes the hsrω ncRNA-containing omega speckle nuclear compartments. PLoS Genet. 2011, 7, e1002096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piccolo, L.L.; Corona, D.; Onorati, M.C. Emerging roles for hnRNPs in post-transcriptional regulation: What can we learn from flies? Chromosoma 2014, 123, 515–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasanth, K.V.; Rajendra, T.K.; Lal, A.K.; Lakhotia, S.C. Omega speckles—A novel class of nuclear speckles containing hnRNPs associated with noncoding hsr-omega RNA in Drosophila. J. Cell Sci. 2000, 113 Pt 19, 3485–3497. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, A.K.; Lakhotia, S.C. Dynamics of hnRNPs and omega speckles in normal and heat shocked live cell nuclei of Drosophila melanogaster. Chromosoma 2015, 124, 367–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terasawa, K.; Tomabechi, Y.; Ikeda, M.; Ehara, H.; Kukimoto-Niino, M.; Wakiyama, M.; Podyma-Inoue, K.A.; Rajapakshe, A.R.; Watabe, T.; Shirouzu, M.; et al. Lysosome-associated membrane proteins-1 and -2 (LAMP-1 and LAMP-2) assemble via distinct modes. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2016, 479, 489–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, K.A.; Janke, A.M.; Rhine, C.L.; Fawzi, N.L. Residue-by-Residue View of In Vitro FUS Granules that Bind the C-Terminal Domain of RNA Polymerase II. Mol. Cell 2015, 60, 231–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, T.W.; Kato, M.; Xie, S.; Wu, L.C.; Mirzaei, H.; Pei, J.; Chen, M.; Xie, Y.; Allen, J.; Xiao, G.; et al. Cell-free formation of RNA granules: Bound RNAs identify features and components of cellular assemblies. Cell 2012, 149, 768–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kato, M.; Han, T.W.; Xie, S.; Shi, K.; Du, X.; Wu, L.C.; Mirzaei, H.; Goldsmith, E.J.; Longgood, J.; Pei, J.; et al. Cell-free formation of RNA granules: Low complexity sequence domains form dynamic fibers within hydrogels. Cell 2012, 149, 753–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Protter, D.S.; Rosen, M.K.; Parker, R. Formation and Maturation of Phase-Separated Liquid Droplets by RNA-Binding Proteins. Mol. Cell 2015, 60, 208–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsumoto, T.; Matsukawa, K.; Watanabe, N.; Kishino, Y.; Kunugi, H.; Ihara, R.; Wakabayashi, T.; Hashimoto, T.; Iwatsubo, T. Self-assembly of FUS through its low-complexity domain contributes to neurodegeneration. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2018, 27, 1353–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Kim, H.J.; Wang, H.; Monaghan, J.; Freyermuth, F.; Sung, J.C.; O’Donovan, K.; Fare, C.M.; Diaz, Z.; Singh, N.; et al. Nuclear-Import Receptors Reverse Aberrant Phase Transitions of RNA-Binding Proteins with Prion-like Domains. Cell 2018, 173, 677–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couthouis, J.; Hart, M.P.; Shorter, J.; DeJesus-Hernandez, M.; Erion, R.; Oristano, R.; Liu, A.X.; Ramos, D.; Jethava, N.; Hosangadi, D.; et al. A yeast functional screen predicts new candidate ALS disease genes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 20881–20890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennig, S.; Kong, G.; Mannen, T.; Sadowska, A.; Kobelke, S.; Blythe, A.; Knott, G.J.; Iyer, K.S.; Ho, D.; Newcombe, E.A.; et al. Prion-like domains in RNA binding proteins are essential for building subnuclear paraspeckles. J. Cell Biol. 2015, 210, 529–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, J.C.; Wang, X.; Podell, E.R.; Cech, T.R. RNA seeds higher-order assembly of FUS protein. Cell Rep. 2013, 5, 918–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boeynaems, S.; Alberti, S.; Fawzi, N.L.; Mittag, T.; Polymenidou, M.; Rousseau, F.; Schymkowitz, J.; Shorter, J.; Wolozin, B.; van den Bosch, L.; et al. Protein Phase Separation: A New Phase in Cell Biology. Trends Cell Biol. 2018, 28, 420–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molliex, A.; Temirov, J.; Lee, J.; Coughlin, M.; Kanagaraj, A.P.; Kim, H.J.; Mittag, T.; Taylor, J.P. Phase separation by low complexity domains promotes stress granule assembly and drives pathological fibrillization. Cell 2015, 163, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, A.; Lee, H.O.; Jawerth, L.; Maharana, S.; Jahnel, M.; Hein, M.Y.; Stoynov, S.; Mahamid, J.; Saha, S.; Franzmann, T.M.; et al. A Liquid-to-Solid Phase Transition of the ALS Protein FUS Accelerated by Disease Mutation. Cell 2015, 162, 1066–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- March, Z.M.; King, O.D.; Shorter, J. Prion-like domains as epigenetic regulators, scaffolds for subcellular organization, and drivers of neurodegenerative disease. Brain Res. 2016, 1647, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dudman, J.; Qi, X. Stress Granule Dysregulation in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2020, 14, 598517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmann, S.; Kedersha, N.; Anderson, P.; Ivanov, P. Molecular mechanisms of stress granule assembly and disassembly. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. Mol. Cell Res. 2021, 1868, 118876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolozin, B.; Ivanov, P. Stress granules and neurodegeneration. Nature Rev. Neurosci. 2019, 20, 649–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, F.; Hu, Y.; Chen, R.; Meng, D.; Guo, L.; Lv, H.; Guan, J.; Jia, Y. In vivo stress granule misprocessing evidenced in a FUS knock-in ALS mouse model. Brain 2020, 143, 1350–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratovitski, T.; O’Meally, R.N.; Jiang, M.; Chaerkady, R.; Chighladze, E.; Stewart, J.C.; Wang, X.; Arbez, N.; Roby, E.; Alexandris, A.; et al. Post-Translational Modifications (PTMs), Identified on Endogenous Huntingtin, Cluster within Proteolytic Domains between HEAT Repeats. J. Proteome Res. 2017, 16, 2692–2708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, P.J.; Timothy, G.J. Post-translational modification of α-synuclein in Parkinson’s disease. Brain Res. 2015, 1628, 247–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correia, S.C.; Carvalho, C.; Cardoso, S.; Moreira, P.I. Post-translational modifications in brain health and disease. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. Mol. Basis dis. 2019, 1865, 1947–1948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurtishi, A.; Rosen, B.; Patil, K.S.; Alves, G.W.; Møller, S.G. Cellular Proteostasis in Neurodegeneration. Mol. Neurobiol. 2019, 56, 3676–3689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Mandelkow, E. Tau in physiology and pathology. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2016, 17, 5–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rhoads, S.N.; Monahan, Z.T.; Yee, D.S.; Shewmaker, F.P. The Role of Post-Translational Modifications on Prion-Like Aggregation and Liquid-Phase Separation of FUS. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Y.C.; Ng, C.S.; Xiang, P.; Liu, H.; Zhang, K.; Mohamud, Y.; Luo, H. Dysregulation of RNA-Binding Proteins in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2020, 13, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dormann, D.; Madl, T.; Valori, C.F.; Bentmann, E.; Tahirovic, S.; Abou-Ajram, C.; Kremmer, E.; Ansorge, O.; Mackenzie, I.R.; Neumann, M.; et al. Arginine methylation next to the PY-NLS modulates Transportin binding and nuclear import of FUS. EMBO J. 2012, 31, 4258–4275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofweber, M.; Hutten, S.; Bourgeois, B.; Spreitzer, E.; Niedner-Boblenz, A.; Schifferer, M.; Ruepp, M.D.; Simons, M.; Niessing, D.; Madl, T.; et al. Phase Separation of FUS Is Suppressed by Its Nuclear Import Receptor and Arginine Methylation. Cell 2018, 173, 706–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qamar, S.; Wang, G.; Randle, S.J.; Ruggeri, F.S.; Varela, J.A.; Lin, J.Q.; Phillips, E.C.; Miyashita, A.; Williams, D.; Ströhl, F.; et al. FUS Phase Separation Is Modulated by a Molecular Chaperone and Methylation of Arginine Cation-π Interactions. Cell 2018, 173, 720–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulanger, M.C.; Miranda, T.B.; Clarke, S.; di Fruscio, M.; Suter, B.; Lasko, P.; Richard, S. Characterization of the Drosophila protein arginine methyltransferases DART1 and DART4. Biochem. J. 2004, 379, 283–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scaramuzzino, C.; Casci, I.; Parodi, S.; Lievens, P.M.J.; Polanco, M.J.; Milioto, C.; Chivet, M.; Monaghan, J.; Mishra, A.; Badders, N.; et al. Protein arginine methyltransferase 6 enhances polyglutamine-expanded androgen receptor function and toxicity in spinal and bulbar muscular atrophy. Neuron 2015, 85, 88–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.C.; Li, C. Evolutionarily conserved protein arginine methyltransferases in non-mammalian animal systems. FEBS J. 2012, 279, 932–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo Piccolo, L.; Mochizuki, H.; Nagai, Y. The lncRNA hsrω regulates arginine dimethylation of human FUS to cause its proteasomal degradation in Drosophila. J. Cell Sci. 2019, 132, jcs236836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braun, R.J.; Zischka, H. Mechanisms of Cdc48/VCP-mediated cell death: From yeast apoptosis to human disease. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2008, 1783, 1418–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Kobayashi, H.; Tomari, Y. Identification of an AGO (Argonaute) protein as a prey of TER94/VCP. Autophagy 2020, 16, 190–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer, H.; Bug, M.; Bremer, S. Emerging functions of the VCP/p97 AAA-ATPase in the ubiquitin system. Nature Cell Biol. 2012, 14, 117–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, J.O.; Mandrioli, J.; Benatar, M.; Abramzon, Y.; van Deerlin, V.M.; Trojanowski, J.Q.; Gibbs, J.R.; Brunetti, M.; Gronka, S.; Wuu, J.; et al. Exome sequencing reveals VCP mutations as a cause of familial ALS. Neuron 2010, 68, 857–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harley, J.; Hagemann, C.; Serio, A.; Patani, R. FUS is lost from nuclei and gained in neurites of motor neurons in a human stem cell model of VCP-related ALS. Brain 2020, 143, e103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyzack, G.E.; Luisier, R.; Taha, D.M.; Neeves, J.; Modic, M.; Mitchell, J.S.; Meyer, I.; Greensmith, L.; Newcombe, J.; Ule, J.; et al. Widespread FUS mislocalization is a molecular hallmark of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Brain 2019, 142, 2572–2580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baillon, L.; Germani, F.; Rockel, C.; Hilchenbach, J.; Basler, K. Xrp1 is a transcription factor required for cell competition-driven elimination of loser cells. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 17712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeves, R. Nuclear functions of the HMG proteins. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2010, 1799, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallik, M.; Catinozzi, M.; Hug, C.B.; Zhang, L.; Wagner, M.; Bussmann, J.; Bittern, J.; Mersmann, S.; Klämbt, C.; Drexler, H.C.A.; et al. Xrp1 genetically interacts with the ALS-associated FUS orthologue caz and mediates its toxicity. J. Cell Biol. 2018, 217, 3947–3964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwasaki, Y.W.; Murano, K.; Ishizu, H.; Shibuya, A.; Iyoda, Y.; Siomi, M.C.; Siomi, H.; Saito, K. Piwi Modulates Chromatin Accessibility by Regulating Multiple Factors Including Histone H1 to Repress Transposons. Mol. Cell 2016, 63, 408–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le, T.A.; Rogers, A.K.; Webster, A.; Marinov, G.K.; Liao, S.E.; Perkins, E.M.; Hur, J.K.; Aravin, A.A.; Tóth, K.F. Piwi induces piRNA-guided transcriptional silencing and establishment of a repressive chromatin state. Genes Dev. 2013, 27, 390–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamanaka, S.; Siomi, M.C.; Siomi, H. piRNA clusters and open chromatin structure. Mob. DNA 2014, 5, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghildiyal, M.; Seitz, H.; Horwich, M.D.; Li, C.; Du, T.; Lee, S.; Xu, J.; Kittler, E.L.; Zapp, M.L.; Weng, Z.; et al. Endogenous siRNAs derived from transposons and mRNAs in Drosophila somatic cells. Science (New York, NY) 2008, 320, 1077–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perrat, P.N.; DasGupta, S.; Wang, J.; Theurkauf, W.; Weng, Z.; Rosbash, M.; Waddell, S. Transposition-driven genomic heterogeneity in the Drosophila brain. Science (New York, NY) 2013, 340, 91–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Youle, R.J.; Narendra, D.P. Mechanisms of mitophagy. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2011, 12, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Chen, Y.; Xu, W.; Wu, N.; Li, M.; Cao, Y.; Wu, S.; Li, Q.; Xue, L. Impaired Hippo signaling promotes Rho1-JNK-dependent growth. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 1065–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, X.; Wang, H.; Ji, J.; Xu, W.; Sun, Y.; Li, W.; Zhang, X.; Chen, J.; Xue, L. Hippo signaling promotes JNK-dependent cell migration. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 1934–1939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kango-Singh, M.; Singh, A. Regulation of organ size: Insights from the Drosophila Hippo signaling pathway. Dev. Dyn. Off. Publ. Am. Assoc. Anat. 2009, 238, 1627–1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manning, S.A.; Kroeger, B.; Harvey, K.F. The regulation of Yorkie, YAP and TAZ: New insights into the Hippo pathway. Development (Cambridge, UK) 2020, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahu, M.R.; Mondal, A.C. The emerging role of Hippo signaling in neurodegeneration. J. Neurosci. Res. 2020, 98, 796–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brunet, M.A.; Jacques, J.F.; Nassari, S.; Tyzack, G.E.; McGoldrick, P.; Zinman, L.; Jean, S.; Robertson, J.; Patani, R.; Roucou, X. The FUS gene is dual-coding with both proteins contributing to FUS-mediated toxicity. EMBO Rep. 2020, 22, e50640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arai, T.; Hasegawa, M.; Akiyama, H.; Ikeda, K.; Nonaka, T.; Mori, H.; Mann, D.; Tsuchiya, K.; Yoshida, M.; Hashizume, Y.; et al. TDP-43 is a component of ubiquitin-positive tau-negative inclusions in frontotemporal lobar degeneration and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2006, 351, 602–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gitcho, M.A.; Baloh, R.H.; Chakraverty, S.; Mayo, K.; Norton, J.B.; Levitch, D.; Hatanpaa, K.J.; White, C.L., 3rd; Bigio, E.H.; Caselli, R.; et al. TDP-43 A315T mutation in familial motor neuron disease. Ann. Neurol. 2008, 63, 535–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kabashi, E.; Valdmanis, P.N.; Dion, P.; Spiegelman, D.; McConkey, B.J.; Vande Velde, C.; Bouchard, J.P.; Lacomblez, L.; Pochigaeva, K.; Salachas, F.; et al. TARDBP mutations in individuals with sporadic and familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Nat. Genet. 2008, 40, 572–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rutherford, N.J.; Zhang, Y.J.; Baker, M.; Gass, J.M.; Finch, N.A.; Xu, Y.F.; Stewart, H.; Kelley, B.J.; Kuntz, K.; Crook, R.J.; et al. Novel mutations in TARDBP (TDP-43) in patients with familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. PLoS Genet. 2008, 4, e1000193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreedharan, J.; Blair, I.P.; Tripathi, V.B.; Hu, X.; Vance, C.; Rogelj, B.; Ackerley, S.; Durnall, J.C.; Williams, K.L.; Buratti, E.; et al. TDP-43 mutations in familial and sporadic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Science (New York, NY) 2008, 319, 1668–1672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Deerlin, V.M.; Leverenz, J.B.; Bekris, L.M.; Bird, T.D.; Yuan, W.; Elman, L.B.; Clay, D.; Wood, E.M.; Chen-Plotkin, A.S.; Martinez-Lage, M.; et al. TARDBP mutations in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis with TDP-43 neuropathology: A genetic and histopathological analysis. Lancet Neurol. 2008, 7, 409–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yokoseki, A.; Shiga, A.; Tan, C.F.; Tagawa, A.; Kaneko, H.; Koyama, A.; Eguchi, H.; Tsujino, A.; Ikeuchi, T.; Kakita, A.; et al. TDP-43 mutation in familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Ann. Neurol. 2008, 63, 538–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapeli, K.; Martinez, F.J.; Yeo, G.W. Genetic mutations in RNA-binding proteins and their roles in ALS. Human Genet. 2017, 136, 1193–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picher-Martel, V.; Valdmanis, P.N.; Gould, P.V.; Julien, J.P.; Dupré, N. From animal models to human disease: A genetic approach for personalized medicine in ALS. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2016, 4, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buratti, E.; Baralle, F.E. The multiple roles of TDP-43 in pre-mRNA processing and gene expression regulation. RNA Biol. 2010, 7, 420–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suk, T.R.; Rousseaux, M.W.C. The role of TDP-43 mislocalization in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Molecular Neurodegener. 2020, 15, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.Y.; Wang, I.F.; Bose, J.; Shen, C.K. Structural diversity and functional implications of the eukaryotic TDP gene family. Genomics 2004, 83, 130–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, M.J.; Cheng, C.W.; Shen, C.K. Neuronal function and dysfunction of Drosophila dTDP. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e20371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaper, D.C.; Adachi, Y.; Sutcliffe, B.; Humphrey, D.M.; Elliott, C.J.; Stepto, A.; Ludlow, Z.N.; Vanden, B.L.; Callaerts, P.; Dermaut, B.; et al. Loss and gain of Drosophila TDP-43 impair synaptic efficacy and motor control leading to age-related neurodegeneration by loss-of-function phenotypes. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2013, 22, 1539–1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feiguin, F.; Godena, V.K.; Romano, G.; D’Ambrogio, A.; Klima, R.; Baralle, F.E. Depletion of TDP-43 affects Drosophila motoneurons terminal synapsis and locomotive behavior. FEBS Lett. 2009, 583, 1586–1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiesel, F.C.; Voigt, A.; Weber, S.S.; van den Haute, C.; Waldenmaier, A.; Görner, K.; Walter, M.; Anderson, M.L.; Kern, J.V.; Rasse, T.M.; et al. Knockdown of transactive response DNA-binding protein (TDP-43) downregulates histone deacetylase 6. EMBO J. 2010, 29, 209–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kushimura, Y.; Tokuda, T.; Azuma, Y.; Yamamoto, I.; Mizuta, I.; Mizuno, T.; Nakagawa, M.; Ueyama, M.; Nagai, Y.; Yoshida, H.; et al. Overexpression of ter94, Drosophila VCP, improves motor neuron degeneration induced by knockdown of TBPH, Drosophila TDP-43. Am. J. Neurodegener. Dis. 2018, 7, 11–31. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Diaper, D.C.; Adachi, Y.; Lazarou, L.; Greenstein, M.; Simoes, F.A.; di Domenico, A.; Solomon, D.A.; Lowe, S.; Alsubaie, R.; Cheng, D.; et al. Drosophila TDP-43 dysfunction in glia and muscle cells cause cytological and behavioural phenotypes that characterize ALS and FTLD. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2013, 22, 3883–3893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romano, G.; Appocher, C.; Scorzeto, M.; Klima, R.; Baralle, F.E.; Megighian, A.; Feiguin, F. Glial TDP-43 regulates axon wrapping, GluRIIA clustering and fly motility by autonomous and non-autonomous mechanisms. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2015, 24, 6134–6145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Llamusi, B.; Bargiela, A.; Fernandez-Costa, J.M.; Garcia-Lopez, A.; Klima, R.; Feiguin, F.; Artero, R. Muscleblind, BSF and TBPH are mislocalized in the muscle sarcomere of a Drosophila myotonic dystrophy model. Dis. Models Mech. 2013, 6, 184–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.J.H.; Sinclair, D.A.R.; Kim, H.Y.; Kinsey, S.D.; Yoo, B.; Shih, C.R.Y.; Wong, K.K.L.; Krieger, C.; Harden, N.; Verheyen, E.M. Homeodomain-interacting protein kinase (Hipk) plays roles in nervous system and muscle structure and function. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0221006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, Y.; Ferris, J.; Gao, F.B. Frontotemporal dementia and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis-associated disease protein TDP-43 promotes dendritic branching. Mol. Brain 2009, 2, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hazelett, D.J.; Chang, J.C.; Lakeland, D.L.; Morton, D.B. Comparison of parallel high-throughput RNA sequencing between knockout of TDP-43 and its overexpression reveals primarily nonreciprocal and nonoverlapping gene expression changes in the central nervous system of Drosophila. G3 Genes Genomes Genet. 2012, 2, 789–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vanden, B.L.; Naval-Sánchez, M.; Adachi, Y.; Diaper, D.; Dourlen, P.; Chapuis, J.; Kleinberger, G.; Gistelinck, M.; van Broeckhoven, C.; Lambert, J.C.; et al. TDP-43 loss-of-function causes neuronal loss due to defective steroid receptor-mediated gene program switching in Drosophila. Cell Rep. 2013, 3, 160–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, J.C.; Hazelett, D.J.; Stewart, J.A.; Morton, D.B. Motor neuron expression of the voltage-gated calcium channel cacophony restores locomotion defects in a Drosophila, TDP-43 loss of function model of ALS. Brain Res. 2014, 1584, 39–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lembke, K.M.; Scudder, C.; Morton, D.B. Restoration of Motor Defects Caused by Loss of Drosophila TDP-43 by Expression of the Voltage-Gated Calcium Channel, Cacophony, in Central Neurons. J. Neurosci. 2017, 37, 9486–9497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godena, V.K.; Romano, G.; Romano, M.; Appocher, C.; Klima, R.; Buratti, E.; Baralle, F.E.; Feiguin, F. TDP-43 regulates Drosophila neuromuscular junctions growth by modulating Futsch/MAP1B levels and synaptic microtubules organization. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e17808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donde, A.; Sun, M.; Ling, J.P.; Braunstein, K.E.; Pang, B.; Wen, X.; Cheng, X.; Chen, L.; Wong, P.C. Splicing repression is a major function of TDP-43 in motor neurons. Acta Neuropathol. 2019, 138, 813–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]