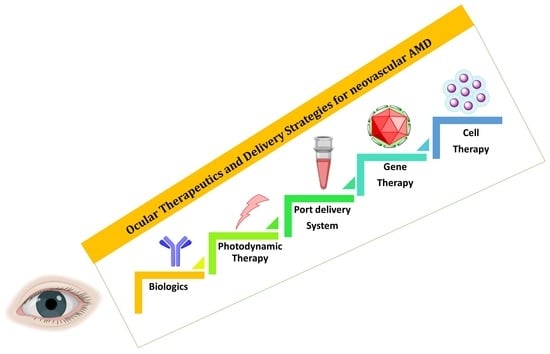

Ocular Therapeutics and Molecular Delivery Strategies for Neovascular Age-Related Macular Degeneration (nAMD)

Abstract

1. Introduction

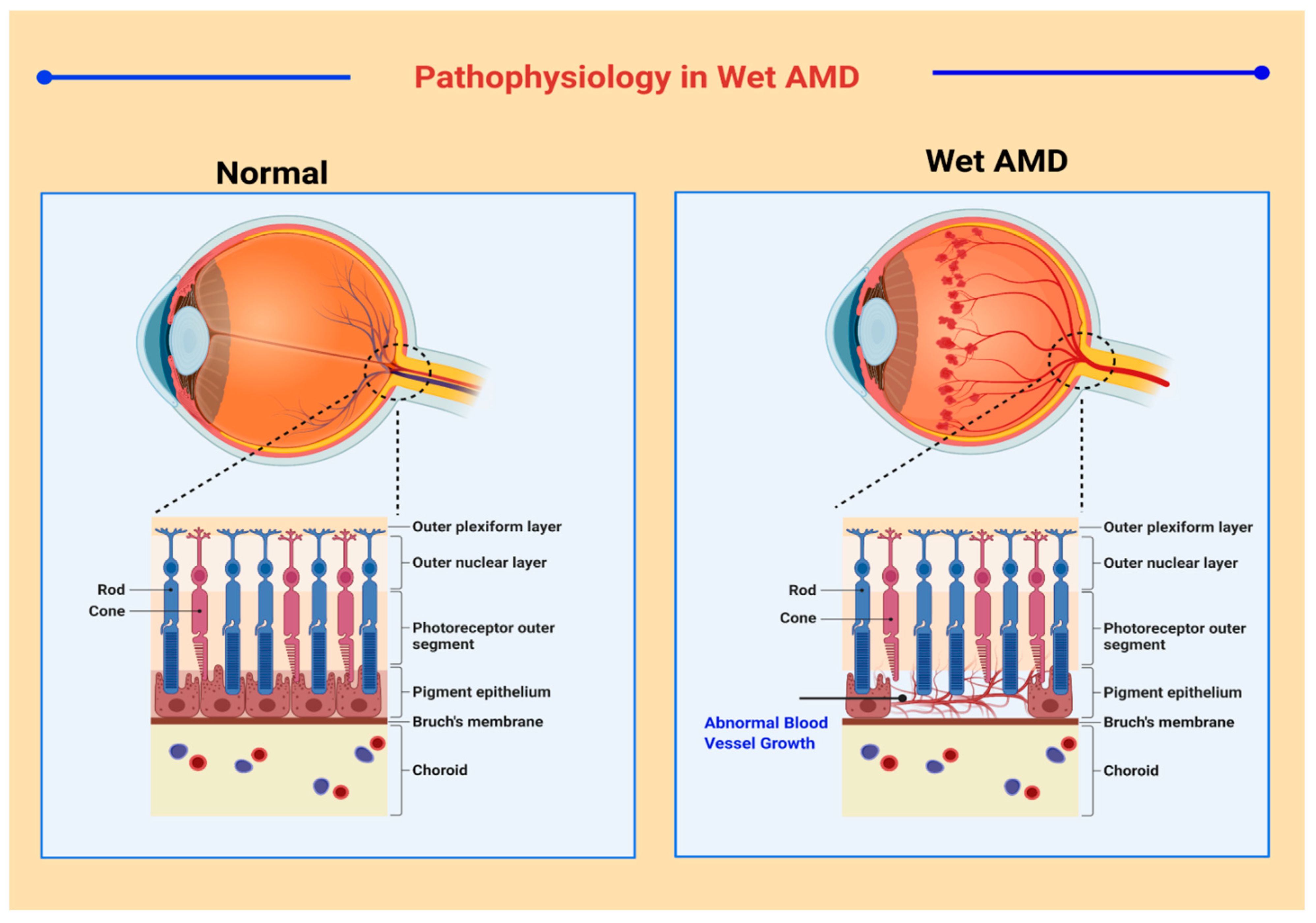

2. Pathogenesis of AMD

3. Advanced Therapeutics and Delivery Strategies for nAMD

3.1. Anti-VEGF Therapy and Its Delivery Strategies

3.1.1. Bevacizumab

3.1.2. Ranibizumab

3.1.3. Aflibercept

3.1.4. Pegaptanib

3.1.5. Brolucizumab

3.1.6. Bispecific Antibodies

3.1.7. Abicipar Pegol

3.1.8. Limitations of Anti-VEGF Therapy

3.1.9. Bioavailability, Dosing, and Pharmacokinetic Considerations of Anti-VEGF Agents

3.2. Novel Therapeutic Agents for AMD: Beyond Anti-VEGF Therapy

3.2.1. Platelet-Derived Growth Factor (PDGF) Inhibitors

3.2.2. Pigment Epithelium-Derived Factor (PEDF) as a Treatment Agent

3.2.3. Angiopoietin Inhibitors

3.2.4. Anti-Inflammatory Agents and Other Small Molecules

3.3. Port Delivery System (PDS)

3.4. Photodynamic Therapy and Its Delivery Strategies

3.5. Radiation Therapy

3.6. Gene Therapy and Its Delivery Strategies

3.6.1. Description of Viral Vectors

3.6.2. Mode of Administration

3.6.3. Viral Vectors for Gene Therapy

Pigment Epithelium-Derived Factor Gene Therapy

VEGF Gene Therapy

Other Factors

3.7. Cell Therapy

4. Concluding Remarks and Future Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AMD | Age-related macular degeneration |

| AAV | Adeno associated virus |

| ANG | Angiopoietins |

| AREDS | Age-Related Eye Disease Study |

| ARM | Age-related maculopathy |

| AuNPs | Gold Nanoparticles |

| CNV | Choroidal neovascularization |

| DME | Diabetic macular edema |

| EBT | External beam therapy |

| EMBT | Epimacular brachytherapy |

| ESC | Embryonic stem cells |

| GA | Geographic atrophy |

| HSA | Human serum albumin |

| HUVECs | Human umbilical vein endothelial cells |

| ICG | Indocyanine green |

| IgG | Immunoglobulin G |

| iPSC | induced Pluripotent stem cell |

| mAb | Monoclonal antibody |

| NPs | Nanoparticles |

| PDGF | Platelet derived growth factor |

| PDS | Port delivery system |

| PDT | Photodynamic therapy |

| PEG | Polyethylene glycol |

| PGB | Pegaptanib |

| PLGA | Poly (D, L-lactide-co-glycolide) |

| PPV | Pars plana vitrectomy |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| RPE | Retinal pigment epithelium |

| SSC | Somatic stem cells |

| TKI | Tyrosine kinase inhibitor. |

| VEGF | Vascular endothelial growth factor |

References

- Wong, W.L.; Su, X.; Li, X.; Cheung, C.M.G.; Klein, R.; Cheng, C.Y.; Wong, T.Y. Global prevalence of age-related macular degeneration and disease burden projection for 2020 and 2040: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Glob. Health 2014, 2, e106–e116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonas, J.B.; Cheung, C.M.G.; Panda-Jonas, S. Updates on the Epidemiology of Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Asia-Pac. J. Ophthalmol. 2017, 6, 493–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleckenstein, M.; Keenan, T.D.L.; Guymer, R.H.; Chakravarthy, U.; Schmitz-Valckenberg, S.; Klaver, C.C.; Wong, W.T.; Chew, E.Y. Age-related macular degeneration. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 2021, 7, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulbake, U.; Doppalapudi, S.; Kommineni, N.; Khan, W. Liposomal Formulations in Clinical Use: An Updated Review. Pharmaceutics 2017, 9, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- del Amo, E.M.; Rimpelä, A.-K.; Heikkinen, E.; Kari, O.K.; Ramsay, E.; Lajunen, T.; Schmitt, M.; Pelkonen, L.; Bhattacharya, M.; Richardson, D.; et al. Pharmacokinetic aspects of retinal drug delivery. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2017, 57, 134–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wan, C.-R.; Muya, L.; Kansara, V.; Ciulla, T. Suprachoroidal Delivery of Small Molecules, Nanoparticles, Gene and Cell Therapies for Ocular Diseases. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, M.S.; Park, S.S.; Albini, T.A.; Canto-Soler, M.V.; Klassen, H.; MacLaren, R.E.; Takahashi, M.; Nagiel, A.; Schwartz, S.D.; Bharti, K. Retinal stem cell transplantation: Balancing safety and potential. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2020, 75, 100779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Tang, Z.; Gu, P. Stem/progenitor cell-based transplantation for retinal degeneration: A review of clinical trials. Cell Death Dis. 2020, 11, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholl, H.P.N.; Strauss, R.W.; Singh, M.S.; Dalkara, D.; Roska, B.; Picaud, S.; Sahel, J.-A. Emerging therapies for inherited retinal degeneration. Sci. Transl. Med. 2016, 8, 368rv6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baradaran-Rafii, A.; Sarvari, M.; Alavi-Moghadam, S.; Payab, M.; Goodarzi, P.; Aghayan, H.R.; Larijani, B.; Rezaei-Tavirani, M.; Biglar, M.; Arjmand, B. Cell-based approaches towards treating age-related macular degeneration. Cell Tissue Bank. 2020, 21, 339–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wels, M.; Roels, D.; Raemdonck, K.; De Smedt, S.; Sauvage, F. Challenges and strategies for the delivery of biologics to the cornea. J. Control. Release 2021, 333, 560–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patil, A.; Dyawanapelly, S.; Dandekar, P.; Jain, R. Fabrication and Characterization of Non-spherical Polymeric Particles. J. Pharm. Innov. 2020, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atale, S.S.; Dyawanapelly, S.; Jagtap, D.D.; Jain, R.; Dandekar, P. Understanding the nano-bio interactions using real-time surface plasmon resonance tool. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 123, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anselmo, A.C.; Mitragotri, S. Nanoparticles in the clinic. Bioeng. Transl. Med. 2016, 1, 10–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anselmo, A.C.; Mitragotri, S. Nanoparticles in the clinic: An update post COVID-19 vaccines. Bioeng. Transl. Med. 2021, 6, e10246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Junnuthula, V.; Boroujeni, A.S.; Cao, S.; Tavakoli, S.; Ridolfo, R.; Toropainen, E.; Ruponen, M.; van Hest, J.; Urtti, A. Intravitreal Polymeric Nanocarriers with Long Ocular Retention and Targeted Delivery to the Retina and Optic Nerve Head Region. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ridolfo, R.; Tavakoli, S.; Junnuthula, V.; Williams, D.S.; Urtti, A.; Van Hest, J.C.M. Exploring the Impact of Morphology on the Properties of Biodegradable Nanoparticles and Their Diffusion in Complex Biological Medium. Biomacromolecules 2021, 22, 126–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Mittal, S. Nanotechnology: Revolutionizing the delivery of drugs to treat age-related macular degeneration. Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 2021, 18, 1131–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iglicki, M.; González, D.P.; Loewenstein, A.; Zur, D. Longer-acting treatments for neovascular age-related macular degeneration—Present and future. Eye 2021, 35, 1111–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Formica, M.L.; Alfonso, H.G.A.; Palma, S.D. Biological drug therapy for ocular angiogenesis: Anti-VEGF agents and novel strategies based on nanotechnology. Pharmacol. Res. Perspect. 2021, 9, e00723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyer, S.; Radwan, A.E.; Hafezi-Moghadam, A.; Malyala, P.; Amiji, M. Long-acting intraocular Delivery strategies for biological therapy of age-related macular degeneration. J. Control. Release 2019, 296, 140–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarkar, A.; Dyawanapelly, S. Nanodiagnostics and Nanotherapeutics for age-related macular degeneration. J. Control. Release 2021, 329, 1262–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skelly, A.; Bezlyak, V.; Liew, G.; Kap, E.; Sagkriotis, A.; Liew, K. Treat and Extend Treatment Interval Patterns with Anti-VEGF Therapy in nAMD Patients. Vision 2019, 3, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Zamil, W.M.; Yassin, S.A. Recent developments in age-related macular degeneration: A review. Clin. Interv. Aging 2017, 12, 1313–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitchell, P.; Liew, G.; Gopinath, B.; Wong, T.Y. Age-related macular degeneration. Lancet 2018, 392, 1147–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, V. Ranibizumab for the treatment of wet AMD: A summary of real-world studies. Eye 2016, 30, 270–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holz, F.G.; Schmitz-valckenberg, S.; Invest, J.C.; Holz, F.G.; Schmitz-valckenberg, S.; Fleckenstein, M. Recent developments in the treatment of age- related macular degeneration Find the latest version: Recent developments in the treatment of age-related macular degeneration. J. Clin. Investig. 2014, 124, 1430–1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, R.; Dana, T.; Bougatsos, C.; Grusing, S.; Blazina, I. Screening for Impaired Visual Acuity in Older Adults: A Systematic Review to Update the 2009 U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA 2016, 315, 915–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tielsch, J.; Javitt, J.C.; Coleman, A.; Katz, J.; Sommer, A. The Prevalence of Blindness and Visual Impairment among Nursing Home Residents in Baltimore. N. Engl. J. Med. 1995, 332, 1205–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, R.; Davis, M.D.; Magli, Y.L.; Segal, P.; Klein, B.E.; Hubbard, L. The Wisconsin Age-related Maculopathy Grading System. Ophthalmology 1991, 98, 1128–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bird, A.; Bressler, N.; Bressler, S.; Chisholm, I.; Coscas, G.; Davis, M.; de Jong, P.; Klaver, C.; Klein, B.; Klein, R.; et al. An international classification and grading system for age-related maculopathy and age-related macular degeneration. Surv. Ophthalmol. 1995, 39, 367–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, M.D.; Gangnon, R.E.; Lee, L.-Y.; Hubbard, L.D. The Age-Related Eye Disease Study Severity Scale for Age-Related Macular Degeneration. AREDS Rep. 2005, 123, 1484–1498. [Google Scholar]

- Ferris, F.; Wilkinson, C.; Bird, A.; Chakravarthy, U.; Chew, E.; Csaky, K.; Sadda, S.R. Clinical Classification of Age-related Macular Degeneration. Am. Acad. Ophthalmol. 2013, 120, 844–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, R.; Meuer, S.M.; Myers, C.E.; Buitendijk, G.H.S.; Rochtchina, E.; Choudhury, F.; De Jong, P.T.V.M.; McKean-Cowdin, R.; Iyengar, S.; Gao, X.; et al. Harmonizing the Classification of Age-related Macular Degeneration in the Three-Continent AMD Consortium. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2014, 21, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ribatti, D. The crucial role of vascular permeability factor/vascular endothelial growth factor in angiogenesis: A historical review. Br. J. Haematol. 2005, 128, 303–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfesberger, B.; de Arespacohaga, A.G.; Willmann, M.; Gerner, W.; Miller, I.; Schwendenwein, I.; Kleiter, M.; Egerbacher, M.; Thalhammer, J.; Muellauer, L.; et al. Expression of Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor and its Receptors in Canine Lymphoma. J. Comp. Pathol. 2007, 137, 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shima, D.T.; Adamis, A.P.; Ferrara, N.; Yeo, K.T.; Yeo, T.K.; Allende, R.; Folkman, J.; D’Amore, P.A. Hypoxic Induction of Endothelial Cell Growth Factors in Retinal Cells: Identification and Characterization of Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF) as the Mitogen. Mol. Med. 1995, 1, 182–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, J.-P.; Chan, W.-M.; Liu, D.T.; Lai, T.; Choy, K.W.; Pang, C.-P.; Lam, D.S. Aqueous Humor Levels of Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor and Pigment Epithelium–Derived Factor in Polypoidal Choroidal Vasculopathy and Choroidal Neovascularization. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2006, 141, 456–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llabot, J.M.; de Redin, I.L.; Agüeros, M.; Caballero, M.J.D.; Boiero, C.; Irache, J.M.; Allemandi, D. In vitro characterization of new stabilizing albumin nanoparticles as a potential topical drug delivery system in the treatment of corneal neovascularization (CNV). J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2019, 52, 379–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bressler, S.B. Introduction: Understanding the Role of Angiogenesis and Antiangiogenic Agents in Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Ophthalmology 2009, 116, S1–S7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luaces-Rodríguez, A.; Mondelo-García, C.; Zarra-Ferro, I.; González-Barcia, M.; Aguiar, P.; Fernández-Ferreiro, A.; Otero-Espinar, F.J. Intravitreal anti-VEGF drug delivery systems for age-related macular degeneration. Int. J. Pharm. 2020, 573, 118767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solomon, S.D.; Lindsley, K.; Vedula, S.S.; Krzystolik, M.G.; Hawkins, B.S. Anti-vascular endothelial growth factor for neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2019, 2019, CD005139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hussain, R.M.; Ciulla, T.A. Emerging vascular endothelial growth factor antagonists to treat neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Expert Opin. Emerg. Drugs 2017, 22, 235–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blick, S.; Keating, G.; Wagstaff, A. Ranibizumab. Drugs. 2007, 67, 1199–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaudreault, J.; Fei, D.; Rusit, J.; Suboc, P.; Shiu, V. Preclinical Pharmacokinetics of Ranibizumab (rhuFabV2) after a Single Intravitreal Administration. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2005, 46, 726–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fogli, S.; Del Re, M.; Rofi, E.; Posarelli, C.; Figus, M.; Danesi, R. Clinical pharmacology of intravitreal anti-VEGF drugs. Eye 2018, 32, 1010–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, E.W.M.; Shima, D.T.; Calias, P.; Cunningham, E.T.C., Jr.; Guyer, D.R.; Adamis, A.P. Pegaptanib, a targeted anti-VEGF aptamer for ocular vascular disease. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2006, 5, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Khersan, H.; Hussain, R.M.; Ciulla, T.; Dugel, P.U. Innovative therapies for neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 2019, 20, 1879–1891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plückthun, A. Designed ankyrin repeat proteins (DARPins): Binding proteins for research, diagnostics, and therapy. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2015, 55, 489–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Lu, X. Profile of conbercept in the treatment of neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 2015, 9, 2311–2320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, S.S.; Janer, D.; Miller, B.; Ehrlich, J.S.; Perlroth, V.; Velazquez-Martin, J.P. Updated Results of Phase 1b Study of KSI-301, an Anti-VEGF Antibody Biopolymer Conjugate with Extended Durability, in wAMD, DME, and RVO. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2020, 61, 4286. [Google Scholar]

- Asahi, M.G.; Avaylon, J.; Wallsh, J.; Gallemore, R.P. Emerging biological therapies for the treatment of age-related macular degeneration. Expert Opin. Emerg. Drugs 2021, 26, 193–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrukhin, K. Recent Developments in Agents for the Treatment of Age-Related Macular Degeneration and Stargardt Disease. Drug Deliv. Chall. Nov. Ther. Approaches Retin. Dis. 2020, 35, 125–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, M.; Awwad, S.; Ibeanu, N.; Khaw, P.T.; Guiliano, D.; Brocchini, S.; Khalili, H. Dual-acting therapeutic proteins for intraocular use. Drug Discov. Today 2021, 26, 44–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, X.; Li, J.; Xu, X.; Wang, C.; Cheng, Y. IBI302, a promising candidate for AMD treatment, targeting both the VEGF and complement system with high binding affinity in vitro and effective targeting of the ocular tissue in healthy rhesus monkeys. Exp. Eye Res. 2016, 145, 352–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Regula, J.T.; Von Leithner, P.L.; Foxton, R.; Barathi, V.A.; Cheung, C.M.G.; Tun, S.B.B.; Wey, Y.S.; Iwata, D.; Dostalek, M.; Moelleken, J.; et al. Targeting key angiogenic pathways with a bispecific Cross MA b optimized for neovascular eye diseases. EMBO Mol. Med. 2016, 8, 1265–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spaide, R.F.; Sorenson, J.; Maranan, L. Combined photodynamic therapy with verteporfin and intravitreal triamcinolone acetonide for choroidal neovascularization. Ophthalmology 2003, 110, 1517–1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blinder, K.; Blumenkranz, M.; DeSmet, M.; Fish, G.; Friedlander, M.; Gitter, K. Anecortave acetate as monotherapy for the treatment of subfoveal lesions in patients with exudative age-related macular degeneration (AMD)—Interim (month 6) analysis of clinical safety and efficacy. Retina 2003, 23, 14–23. [Google Scholar]

- Diago, T.; Pulido, J.S.; Molina, J.R.; Collet, L.C.; Link, T.P.; Ryan, E.H. Ranibizumab Combined With Low-Dose Sorafenib for Exudative Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2008, 83, 231–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsujinaka, H.; Fu, J.; Shen, J.; Yu, Y.; Hafiz, Z.; Kays, J.; McKenzie, D.; Cardona, D.; Culp, D.; Peterson, W.; et al. Sustained treatment of retinal vascular diseases with self-aggregating sunitinib microparticles. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB-102 for Wet AMD: A Novel Injectable Formulation that Safely Delivers Active Levels of Sunitinib to the Retina and RPE/Choroid for Over Four Months|IOVS|ARVO Journals. Available online: https://iovs.arvojournals.org/article.aspx?articleid=2563200 (accessed on 19 May 2021).

- Powers, J.H.; Wisely, C.E.; Sastry, A.; Fekrat, S. Prompt Improvement of an Enlarging Pigment Epithelial Detachment Following Intravitreal Dexamethasone in Neovascular Age-Related Macular Degeneration. J. Vitr. Dis. 2019, 4, 327–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, V.M.; Decatur, C.L.; Stamer, W.D.; Lynch, R.M.; McKay, B.S. L-DOPA Is an Endogenous Ligand for OA1. PLoS Biol. 2008, 6, e236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Mello, S.A.N.; Finlay, G.J.; Baguley, B.C.; Askarian-Amiri, M.E. Signaling Pathways in Melanogenesis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falk, T.; Congrove, N.R.; Zhang, S.; McCourt, A.D.; Sherman, S.J.; McKay, B. PEDF and VEGF-A Output from Human Retinal Pigment Epithelial Cells Grown on Novel Microcarriers. J. Biomed. Biotechnol. 2012, 2012, 278932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, M.H.; Gootenberg, J.; Keegan, P.; Pazdur, R. FDA Drug Approval Summary: Bevacizumab (Avastin®) Plus Carboplatin and Paclitaxel as First-Line Treatment of Advanced/Metastatic Recurrent Nonsquamous Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Oncologist 2007, 12, 713–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Redín, I.L.; Boiero, C.; Recalde, S.; Agüeros, M.; Allemandi, D.; Llabot, J.M.; García-Layana, A.; Irache, J.M. In vivo effect of bevacizumab-loaded albumin nanoparticles in the treatment of corneal neovascularization. Exp. Eye Res. 2019, 185, 107697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Badiee, P.; Varshochian, R.; Rafiee-Tehrani, M.; Dorkoosh, F.A.; Khoshayand, M.R.; Dinarvand, R. Ocular implant containing bevacizumab-loaded chitosan nanoparticles intended for choroidal neovascularization treatment. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part A 2018, 106, 2261–2271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrishami, M.; Ganavati, S.Z.; Soroush, D.; Rouhbakhsh, M.; Jaafari, M.R.; Malaekeh-Nikouei, B. Preparation, Characterization, and in Vivo Evaluation of Nanoliposomes-Encapsulated Bevacizumab (Avastin) for Intravitreal Administration. Retina 2009, 29, 699–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, F.; Cruz, A.; Fonte, P.; Pinto, I.M.; Neves-Petersen, M.T.; Sarmento, B. A new paradigm for antiangiogenic therapy through controlled release of bevacizumab from PLGA nanoparticles. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.-P.; Sun, J.-G.; Yao, J.; Shan, K.; Liu, B.-H.; Yao, M.-D.; Ge, H.-M.; Jiang, Q.; Zhao, C.; Yan, B. Effect of nanoencapsulation using poly (lactide-co-glycolide) (PLGA) on anti-angiogenic activity of bevacizumab for ocular angiogenesis therapy. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2018, 107, 1056–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malakouti-Nejad, M.; Bardania, H.; Aliakbari, F.; Baradaran-Rafii, A.; Elahi, E.; Monti, D.; Morshedi, D. Formulation of nanoliposome-encapsulated bevacizumab (Avastin): Statistical optimization for enhanced drug encapsulation and properties evaluation. Int. J. Pharm. 2020, 590, 119895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kratz, F. Albumin as a drug carrier: Design of prodrugs, drug conjugates and nanoparticles. J. Control. Release 2008, 132, 171–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, Z.; Ji, Y.-L.; Ma, X.; Wen, J.-G.; Wei, W.; Huang, S.-M. Pharmacokinetics and distributions of bevacizumab by intravitreal injection of bevacizumab-PLGA microspheres in rabbits. Int. J. Ophthalmol. 2015, 8, 653–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauck, B.M.; Friberg, T.R.; Mendez, C.A.M.; Park, D.; Shah, V.; Bilonick, R.A.; Wang, Y. Biocompatible Reverse Thermal Gel Sustains the Release of Intravitreal Bevacizumab In Vivo. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2014, 55, 469–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farjo, K.M.; Ma, J.-X. The potential of nanomedicine therapies to treat neovascular disease in the retina. J. Angiogenesis Res. 2010, 2, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Presta, L.G.; Chen, H.; O’Connor, S.J.; Chisholm, V.; Meng, Y.G.; Krummen, L.; Winkler, M.; Ferrara, N. Humanization of an anti-vascular endothelial growth factor monoclonal antibody for the therapy of solid tumors and other disorders. Cancer Res. 1997, 57, 4593–4599. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, D.J.; Keenan, T.D.; Faes, L.; Lim, E.; Wagner, S.K.; Moraes, G.; Huemer, J.; Kern, C.; Patel, P.J.; Balaskas, K.; et al. Insights From Survival Analyses During 12 Years of Anti–Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Therapy for Neovascular Age-Related Macular Degeneration. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2021, 139, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Peng, X.; Cai, Y.; Cong, W. Development of facile drug delivery platform of ranibizumab fabricated PLGA-PEGylated magnetic nanoparticles for age-related macular degeneration therapy. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 2018, 183, 133–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vollrath, M.; Engert, J.; Winter, G. Long-term release and stability of pharmaceutical proteins delivered from solid lipid implants. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2017, 117, 244–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanetsugu, Y.; Tagami, T.; Terukina, T.; Ogawa, T.; Ohta, M.; Ozeki, T. Development of a Sustainable Release System for a Ranibizumab Biosimilar Using Poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) Biodegradable Polymer-Based Microparticles as a Platform. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2017, 40, 145–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoszyk, A.N.; Tuomi, L.; Chung, C.Y.; Singh, A. Ranibizumab Combined with Verteporfin Photodynamic Therapy in Neovascular Age-related Macular Degeneration (FOCUS): Year 2 Results. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2008, 145, 862–874.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Supuran, C.T. Agents for the prevention and treatment of age-related macular degeneration and macular edema: A literature and patent review. Expert Opin. Ther. Patents 2019, 29, 761–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazzara, F.; Fidilio, A.; Platania, C.B.M.; Giurdanella, G.; Salomone, S.; Leggio, G.M.; Tarallo, V.; Cicatiello, V.; De Falco, S.; Eandi, C.M.; et al. Aflibercept regulates retinal inflammation elicited by high glucose via the PlGF/ERK pathway. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2019, 168, 341–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radhakrishnan, K.; Sonali, N.; Moreno, M.; Nirmal, J.; Fernandez, A.A.; Venkatraman, S.; Agrawal, R. Protein delivery to the back of the eye: Barriers, carriers and stability of anti-VEGF proteins. Drug Discov. Today 2017, 22, 416–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, Q.D. Ranibizumab for diabetic macular edema. Ophthalmology 2012, 119, 789–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohr, M.; Kaiser, P.K. Intravitreal aflibercept injection for neovascular (wet) age-related macular degeneration. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 2012, 13, 585–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, W.; Lee, B.-S.; Mieler, W.F.; Kang-Mieler, J.J. Biodegradable Microsphere-Hydrogel Ocular Drug Delivery System for Controlled and Extended Release of Bioactive Aflibercept In Vitro. Curr. Eye Res. 2019, 44, 264–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, N.M. An overview of the pathophysiology and the past, current, and future treatments of neovascular age-related macular degeneration. N. Z. Med. Stud. J. 2020, 31, 23–27. [Google Scholar]

- Basile, A.S.; Hutmacher, M.; Nickens, D.; Nielsen, J.; Kowalski, K.; Whitfield, L.; Masayo, O.; Nakane, M. Population Pharmacokinetics of Pegaptanib in Patients With Neovascular, Age-Related Macular Degeneration. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2012, 52, 1186–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keizer, R.J.; Huitema, A.D.R.; Schellens, J.H.M.; Beijnen, J.H. Clinical Pharmacokinetics of Therapeutic Monoclonal Antibodies. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 2010, 49, 493–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, G.P.; Burgess, L.; Wing, J.; Dowie, T.; Calias, P.; Shima, D.T.; Campbell, K.; Allison, D.; Volker, S.; Schmidt, P. Preparation and characterization of pegaptanib sustained release microsphere formulations for intraocular application. Investig Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2006, 47, 5123. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, Q.D.; Das, A.; Do, D.V.; Dugel, P.U.; Gomes, A.; Holz, F.G.; Koh, A.; Pan, C.K.; Sepah, Y.J.; Patel, N.; et al. Brolucizumab: Evolution through Preclinical and Clinical Studies and the Implications for the Management of Neovascular Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Ophthalmology 2020, 127, 963–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Markham, A. Brolucizumab: First Approval. Drugs 2019, 79, 1997–2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schlottmann, A.; Alezzandrini, P.G.; Zas, M.; Rodriguez, F.; Luna, J.; Wu, L. New treatment modalities for neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Asia-Pac. J. Ophthalmol. 2017, 6, 514–519. [Google Scholar]

- Haug, S.J.; Hien, D.L.; Uludag, G.; Ngoc, T.T.T.; Lajevardi, S.; Halim, M.S.; Sepah, Y.J.; Do, D.V.; Khanani, A.M. Retinal arterial occlusive vasculitis following intravitreal brolucizumab administration. Am. J. Ophthalmol. Case Rep. 2020, 18, 100680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Home|Brolucizumab. Available online: https://www.brolucizumab.info/ (accessed on 21 September 2021).

- Sheridan, C. Bispecific antibodies poised to deliver wave of cancer therapies. Nat. Biotechnol. 2021, 39, 251–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Development of Novel Bispecific Anti-Inflammatory and Anti-Angiogenic Therapy for the Treatment of Both Retinal Vascular and Inflammatory Diseases|IOVS|ARVO Journals. Available online: https://iovs.arvojournals.org/article.aspx?articleid=2744712 (accessed on 25 May 2021).

- Beacon Targeted Therapies Beacon Bispecific. Available online: https://www.beacon-intelligence.com/bispecifics (accessed on 25 May 2021).

- Callanan, D.; Kunimoto, D.; Maturi, R.K.; Patel, S.S.; Staurenghi, G.; Wolf, S.; Cheetham, J.K.; Hohman, T.C.; Kim, K.; López, F.J.; et al. Double-Masked, Randomized, Phase 2 Evaluation of Abicipar Pegol (an Anti-VEGF DARPin Therapeutic) in Neovascular Age-Related Macular Degeneration. J. Ocul. Pharmacol. Ther. 2018, 34, 700–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battaglia, L.; Gallarate, M.; Serpe, L.; Foglietta, F.; Muntoni, E.; Rodriguez, A.D.P.; Aspiazu, M.; Ángeles, S. Ocular Delivery of Solid Lipid Nanoparticles; Elsevier Inc.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 269–312. [Google Scholar]

- Pikuleva, I.A.; Curcio, C.A. Cholesterol in the retina: The best is yet to come. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2014, 41, 64–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahaling, B.; Srinivasarao, D.A.; Raghu, G.; Kasam, R.K.; Reddy, G.B.; Katti, D.S. A non-invasive nanoparticle mediated delivery of triamcinolone acetonide ameliorates diabetic retinopathy in rats. Nanoscale 2018, 10, 16485–16498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falavarjani, K.G.; Nguyen, Q.D. Adverse events and complications associated with intravitreal injection of anti-VEGF agents: A review of literature. Eye 2013, 27, 787–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishie, H.; Kataoka, H.; Yano, S.; Kikuchi, J.-I.; Hayashi, N.; Narumi, A.; Nomoto, A.; Kubota, E.; Joh, T. A next-generation bifunctional photosensitizer with improved water-solubility for photodynamic therapy and diagnosis. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 74259–74268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schargus, M.; Frings, A. Issues with Intravitreal Administration of Anti-VEGF Drugs. Clin. Ophthalmol. 2020, 14, 897–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; Zhou, M.; Xia, S.; Jing, Q.; Gao, L. Sustained Elevation of Intraocular Pressure Associated with Intravitreal Administration of Anti-vascular Endothelial Growth Factor: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 39301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakri, S.J.; Moshfeghi, D.M.; Francom, S.; Rundle, A.C.; Reshef, D.S.; Lee, P.P.; Schaeffer, C.; Rubio, R.G.; Lai, P. Intraocular Pressure in Eyes Receiving Monthly Ranibizumab in 2 Pivotal Age-Related Macular Degeneration Clinical Trials. Ophthalmology 2014, 121, 1102–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricca, A.M.; Morshedi, R.G.; Wirostko, B.M. High Intraocular Pressure Following Anti-Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Therapy: Proposed Pathophysiology due to Altered Nitric Oxide Metabolism. J. Ocul. Pharmacol. Ther. 2015, 31, 2–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakri, S.J.; Ekdawi, N.S. Intravitreal Silicone Oil Droplets After Intravitreal Drug Injections. Retina 2008, 28, 996–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahook, M.Y.; Ammar, D.A. In Vitro Effects of Antivascular Endothelial Growth Factors on Cultured Human Trabecular Meshwork Cells. J. Glaucoma 2010, 19, 437–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Ammar, D.A.; Ross, L.A.; Mandava, N.; Kahook, M.Y.; Carpenter, J.F. Silicone Oil Microdroplets and Protein Aggregates in Repackaged Bevacizumab and Ranibizumab: Effects of Long-term Storage and Product Mishandling. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2011, 52, 1023–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baudin, F.; Benzenine, E.; Mariet, A.-S.; Bron, A.M.; Daien, V.; Korobelnik, J.F.; Quantin, C.; Creuzot-Garcher, C. Association of Acute Endophthalmitis With Intravitreal Injections of Corticosteroids or Anti–Vascular Growth Factor Agents in a Nationwide Study in France. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2018, 136, 1352–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storey, P.P.; Tauqeer, Z.; Yonekawa, Y.; Todorich, B.; Wolfe, J.D.; Shah, S.P.; Shah, A.R.; Koto, T.; Abbey, A.M.; Morizane, Y.; et al. The Impact of Prefilled Syringes on Endophthalmitis Following Intravitreal Injection of Ranibizumab. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2019, 199, 200–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edison, L.S.; Dishman, H.O.; Tobin-D’Angelo, M.J.; Allen, C.R.; Guh, A.Y.; Drenzek, C.L. Endophthalmitis Outbreak Associated with Repackaged Bevacizumab. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2015, 21, 171–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheyman, A.T.; Cohen, B.Z.; Friedman, A.H.; Ackert, J.M. An Outbreak of Fungal Endophthalmitis After Intravitreal Injection of Compounded Combined Bevacizumab and Triamcinolone. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2013, 131, 864–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bande, M.F.; Mansilla, R.; Pata, M.P.; Fernández, M.; Blanco-Teijeiro, M.J.; Piñeiro, A.; Gómez-Ulla, F. Intravitreal injections of anti-VEGF agents and antibiotic prophylaxis for endophthalmitis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, I.U.; Oden, N.L.; VanVeldhuisen, P.C.; Ip, M.S.; Blodi, B.A.; Antoszyk, A.N. SCORE Study Report 7: Incidence of Intravitreal Silicone Oil Droplets Associated With Staked-on vs Luer Cone Syringe Design. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2009, 148, 725–732.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Sampat, K.M.; Wolfe, J.D.; Shah, M.K.; Garg, S.J. Accuracy and Reproducibility of Seven Brands of Small-Volume Syringes Used for Intraocular Drug Delivery. Ophthalmic Surg. Lasers Imaging Retin. 2013, 44, 385–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinbrook, R. The Price of Sight—Ranibizumab, Bevacizumab, and the Treatment of Macular Degeneration. N. Engl. J. Med. 2006, 355, 1409–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; Fong, W.-K.; Caliph, S.; Boyd, B.J. Lipid-based drug delivery systems in the treatment of wet age-related macular degeneration. Drug Deliv. Transl. Res. 2016, 6, 781–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Subrizi, A.; del Amo, E.M.; Korzhikov-Vlakh, V.; Tennikova, T.; Ruponen, M.; Urtti, A. Design principles of ocular drug delivery systems: Importance of drug payload, release rate, and material properties. Drug Discov. Today 2019, 24, 1446–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rimpelä, A.-K.; Kiiski, I.; Deng, F.; Kidron, H.; Urtti, A. Pharmacokinetic Simulations of Intravitreal Biologicals: Aspects of Drug Delivery to the Posterior and Anterior Segments. Pharmaceutics 2018, 11, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadiq, M.A.; Hanout, M.; Sarwar, S.; Hassan, M.; Agarwal, A.; Sepah, Y.J.; Do, D.V.; Nguyen, Q.D. Platelet-Derived Growth Factor Inhibitors: A Potential Therapeutic Approach for Ocular Neovascularization. Dev. Ophthalmol. 2015, 55, 310–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, S. Combination Therapy for Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Retina 2009, 29, S45–S48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, E.N.; Sheth, V.S.; Hariprasad, S.M. An Overview of the Fovista and Rinucumab Trials and the Fate of Anti-PDGF Medications. Ophthalmic Surg. Lasers Imaging Retin. 2017, 48, 100–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Do, D.V. Antiangiogenic Approaches to Age-Related Macular Degeneration in the Future. Ophthalmology 2009, 116, S24–S26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tombran-Tink, J.; Johnson, L.V. Neuronal differentiation of retinoblastoma cells induced by medium conditioned by human RPE cells. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 1989, 30, 1700–1707. [Google Scholar]

- He, X.; Cheng, R.; Benyajati, S.; Ma, J.-X. PEDF and its roles in physiological and pathological conditions: Implication in diabetic and hypoxia-induced angiogenic diseases. Clin. Sci. 2015, 128, 805–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.X.; Ma, J.-X. Ocular neovascularization: Implication of endogenous angiogenic inhibitors and potential therapy. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2007, 26, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steele, F.R.; Chader, G.J.; Johnson, L.V.; Tombran-Tink, J. Pigment epithelium-derived factor: Neurotrophic activity and identification as a member of the serine protease inhibitor gene family. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1993, 90, 1526–1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Becerra, S.P. Structure-Function Studies on PEDF. Results Probl. Cell Differ. 1997, 425, 223–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson, D.W.; Volpert, O.V.; Gillis, P.; Crawford, S.E.; Xu, H.-J.; Benedict, W.; Bouck, N.P. Pigment Epithelium-Derived Factor: A Potent Inhibitor of Angiogenesis. Science 1999, 285, 245–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holekamp, N.M. Review of neovascular age-related macular degeneration treatment options. Am. J. Manag. Care 2019, 25, S172–S181. [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz-Ramón, P.; Martínez, P.H.; Muñoz-Negrete, F. New therapeutic targets in the treatment of age-related macular degeneration. Arch. Soc. Española Oftalmol. 2020, 95, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cabral, T.; Mello, L.; Lima, L. Retinal and choroidal angiogenesis: A review of new targets. Int. J. Retin. Vitr. 2017, 3, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saharinen, P.; Eklund, L.; Alitalo, K. Therapeutic targeting of the angiopoietin--TIE pathway. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2017, 16, 635–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hackett, S.; Ozaki, H.; Strauss, R. Angiopoietin 2 expression in the retina: Upregulation during physiologic and pathologic neovascularization. J. Cell Physiol. 2000, 184, 275–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahni, J.; Patel, S.S.; Dugel, P.U.; Khanani, A.M.; Jhaveri, C.D.; Wykoff, C.C.; Hershberger, V.S.; Pauly-Evers, M.; Sadikhov, S.; Szczesny, P.; et al. Simultaneous inhibition of angiopoietin-2 and vascular endothelial growth factor-A with faricimab in diabetic macular edema: BOULEVARD phase 2 randomized trial. Ophthalmology 2019, 126, 1155–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.J.; Mitchell, P.; Smith, W.; Gillies, M.; Billson, F. Systemic use of anti-inflammatory medications and age-related maculopathy: The Blue Mountains Eye Study. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2003, 10, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jermak, C.; Dellacroce, J.; Heffez, J.; Peyman, G. Triamcinolone Acetonide in Ocular Therapeutics. Surv. Ophthalmol. 2007, 52, 503–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becerra, E.M.; Morescalchi, F.; Gandolfo, F.; Danzi, P.; Nascimbeni, G.; Arcidiacono, B.; Semeraro, F. Clinical Evidence of Intravitreal Triamcinolone Acetonide in the Management of Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Curr. Drug Targets 2011, 12, 149–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Friedrichs, U.; Eichler, W.; Hoffmann, S.; Wiedemann, P. Inhibitory effects of triamcinolone acetonide on bFGF-induced migration and tube formation in choroidal microvascular endothelial cells. Graefe’s Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2002, 240, 42–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciulla, T.A.; Criswell, M.H.; Danis, R.P.; Hill, T.E. Intravitreal triamcinolone acetonide inhibits choroidal neovascularization in a laser-treated rat model. Arch. Ophthalmol. 2001, 119, 399–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Gillies, M.; Simpson, J.; Luo, W.; Penfold, P.; Hunyor, A. A randomized clinical trial of a single dose of intravitreal triamcinolone acetonide for neovascular agerelated macular degeneration: One year results. Arch. Ophthalmol. 2003, 121, 667–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sutter, F.; Gillies, M. Pseudo-endophthalmitis after intravitreal injection of triamcinolone. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2003, 87, 972–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vakalis, N.; Echiadis, G.; Pervena, A.; Deligiannis, I.; Kavalarakis, E.; Giannikakis, S.; Papaefthymiou, I. Intravitreal Combination of Dexamethasone Sodium Phosphate and Bevacizumab in The Treatment of Exudative AMD. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 8627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calvo, P.; Ferreras, A.; Al Adel, F.; Wang, Y.; Brent, M.H. Dexamethasone intravitreal implant as adjunct therapy for patients with wet age-related macular degeneration with incomplete response to ranibizumab. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2014, 99, 723–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iovino, C.; Mastropasqua, R.; Lupidi, M.; Bacherini, D.; Pellegrini, M.; Bernabei, F.; Borrelli, E.; Sacconi, R.; Carnevali, A.; D’Aloisio, R.; et al. Intravitreal Dexamethasone Implant as a Sustained Release Drug Delivery Device for the Treatment of Ocular Diseases: A Comprehensive Review of the Literature. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12, 703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaudhary, V.; Barbosa, J.; Lam, W.-C.; Mak, M.; Mavrikakis, E. Ozurdex in age-related macular degeneration as adjunct to ranibizumab (The OARA Study). Can. J. Ophthalmol. 2016, 51, 302–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, P.-L.; Peavey, J.; Malek, G. Leveraging Nuclear Receptors as Targets for Pathological Ocular Vascular Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 2889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penn, J.S.; Rajaratnam, V.S.; Collier, R.J.; Clark, A.F. The effect of an angiostatic steroid on neovascularization in a rat model of retinopathy of prematurity. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2001, 42, 283–290. [Google Scholar]

- Dib, E.; Maia, M.; Lima, A.D.S.; Costa, E.D.P.F.; De Moraes-Filho, M.N.; Rodrigues, E.B.; Penha, F.M.; Coppini, L.P.; De Barros, N.M.T.; Coimbra, R.D.C.S.G.; et al. In Vivo, In Vitro Toxicity and In Vitro Angiogenic Inhibition of Sunitinib Malate. Curr. Eye Res. 2012, 37, 567–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunitinib-Loaded Injectable Polymer Depot Formulation for Potential Once per Year Treatment of Neovascular Age-Related Macular Degeneration (Wet AMD)|IOVS|ARVO Journals. Available online: https://iovs.arvojournals.org/article.aspx?articleid=2688905 (accessed on 19 May 2021).

- Figueroa, A.G.; Boyd, B.M.; Christensen, C.A.; Javid, C.G.; McKay, B.S.; Fagan, T.C.; Snyder, R.W. Levodopa Positively Affects Neovascular Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Am. J. Med. 2021, 134, 122–128.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, E.; Kaiser, P.K. Therapeutic Potential of the Ranibizumab Port Delivery System in the Treatment of AMD: Evidence to Date. Clin. Ophthalmol. 2020, 14, 1349–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campochiaro, P.A.; Marcus, D.M.; Awh, C.C.; Regillo, C.; Adamis, A.P.; Bantseev, V.; Chiang, Y.; Ehrlich, J.S.; Erickson, S.; Hanley, W.D.; et al. The Port Delivery System with Ranibizumab for Neovascular Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Ophthalmology 2019, 126, 1141–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubio, R. Long-acting anti-VEGF delivery. Retin. Today 2014, 2014, 78–80. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenfeld, P.; Brown, D.; Heier, J. Ranibizumab for neovascular age-related macular degeneration. N. Engl. J. Med. 2006, 355, 1419–1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, D.M.; Kaiser, P.; Michels, M.; Soubrane, G.; Heier, J.S.; Kim, R.Y.; Sy, J.P.; Schneider, S. Ranibizumab versus Verteporfin for Neovascular Age-Related Macular Degeneration. N. Engl. J. Med. 2006, 355, 1432–1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michels, S.; Rosenfeld, P.J.; Puliafito, C.A.; Marcus, E.N.; Venkatraman, A.S. Systemic Bevacizumab (Avastin) Therapy for Neovascular Age-Related Macular Degeneration: Twelve-Week Results of an Uncontrolled Open-Label Clinical Study. Ophthalmology 2005, 112, 1035–1047.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bantseev, V.; Schuetz, C.; Booler, H.S.; Horvath, J.; Hovaten, K.; Erickson, S.; Bentley, E.; Nork, T.M.; Freeman, W.R.; Stewart, J.M.; et al. Evaluation of surgical factors affecting vitreous hemorrhage following port delivery system with ranibizumab implant insertion in a minipig model. J. Retin. Vitr. Dis. 2020, 40, 1520–1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanani, A.M.; Aziz, A.A.; Weng, C.Y.; Lin, W.V.; Vannavong, J.; Chhablani, J.; Danzig, C.J.; Kaiser, P.K. Port delivery system: A novel drug delivery platform to treat retinal diseases. Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 2021, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christie, J.G.; Kompella, U.B. Ophthalmic light sensitive nanocarrier systems. Drug Discov. Today 2008, 13, 124–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Recommendations|Age-Related Macular Degeneration|Guidance|NICE. Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng82/chapter/Recommendations#pharmacological-management-of-amd (accessed on 21 September 2021).

- AMD Treatment Guidelines|Harvard Medical School Department of Ophthalmology. Available online: https://eye.hms.harvard.edu/eyeinsights/2015-january/age-related-macular-degeneration-amd (accessed on 21 September 2021).

- Gross, N.; Ranjbar, M.; Evers, C.; Hua, J.; Martin, G.; Schulze, B.; Michaelis, U.; Hansen, L.L.; Agostini, H.T. Choroidal neovascularization reduced by targeted drug delivery with cationic liposome-encapsulated paclitaxel or targeted photodynamic therapy with verteporfin encapsulated in cationic liposomes. Mol. Vis. 2013, 19, 54–61. [Google Scholar]

- Li, T.; Hou, X.; Deng, H.; Zhao, J.; Huang, N.; Zeng, J.; Chen, H.; Gu, Y. Liposomal hypocrellin B as a potential photosensitizer for age-related macular degeneration: Pharmacokinetics, photodynamic efficacy, and skin phototoxicity in vivo. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2015, 14, 972–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimazaki, H.; Hironaka, K.; Fujisawa, T.; Tsuruma, K.; Tozuka, Y.; Shimazawa, M.; Takeuchi, H.; Hara, H. Edaravone-Loaded Liposome Eyedrops Protect against Light-Induced Retinal Damage in Mice. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2011, 52, 7289–7297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lajunen, T.; Viitala, L.; Kontturi, L.-S.; Laaksonen, T.; Liang, H.; Vuorimaa-Laukkanen, E.; Viitala, T.; Le Guével, X.; Yliperttula, M.; Murtomäki, L.; et al. Light induced cytosolic drug delivery from liposomes with gold nanoparticles. J. Control. Release 2015, 203, 85–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lajunen, T.; Nurmi, R.; Wilbie, D.; Ruoslahti, T.; Johansson, N.; Korhonen, O.; Rog, T.; Bunker, A.; Ruponen, M.; Urtti, A. The effect of light sensitizer localization on the stability of indocyanine green liposomes. J. Control. Release 2018, 284, 213–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.-L.; Xi, Y.; Liu, Y.-L.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, Q. Combination of Targeted PDT and Anti-VEGF Therapy for Rat CNV by RGD-Modified Liposomal Photocyanine and Sorafenib. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2013, 54, 7983–7989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Y.; Yu, T.; Zhang, Y.; Dang, G. Anti-VEGF Monotherapy Versus Photodynamic Therapy and Anti-VEGF Combination Treatment for Neovascular Age-Related Macular Degeneration: A Meta-Analysis. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2018, 59, 4307–4317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campochiaro, P.A. Gene transfer for ocular neovascularization and macular edema. Gene Ther. 2011, 19, 121–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campochiaro, P.A.; Nguyen, Q.D.; Shah, S.M.; Klein, M.L.; Holz, E.; Frank, R.N.; Saperstein, D.A.; Gupta, A.; Stout, J.T.; Macko, J.; et al. Adenoviral Vector-Delivered Pigment Epithelium-Derived Factor for Neovascular Age-Related Macular Degeneration: Results of a Phase I Clinical Trial. Hum. Gene Ther. 2006, 17, 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, C.-M.; Estcourt, M.J.; Himbeck, R.P.; Lee, S.-Y.; Yeo, I.Y.-S.; Luu, C.; Loh, B.K.; Lee, M.W.; Barathi, A.; Villano, J.; et al. Preclinical safety evaluation of subretinal AAV2.sFlt-1 in non-human primates. Gene Ther. 2011, 19, 999–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, C.-M.; Brankov, M.; Zaknich, T.; Lai, Y.K.-Y.; Shen, W.-Y.; Constable, I.J.; Kovesdi, I.; Rakoczy, P.E. Inhibition of Angiogenesis by Adenovirus-Mediated sFlt-1 Expression in a Rat Model of Corneal Neovascularization. Hum. Gene Ther. 2001, 12, 1299–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, Y.K.Y.; Sharma, S.; Lai, C.-M.; Brankov, M.; Constable, I.J.; Rakoczy, P.E. Virus-mediated secretion gene therapy--A potential treatment for ocular neovascularization. Single Mol. Single Cell Seq. 2003, 533, 447–453. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, N.A.; Bracha, P.; Hussain, R.M.; Morral, N.; Ciulla, T.A. Gene therapy for age-related macular degeneration. Expert Opin. Biol. Ther. 2017, 17, 1235–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heier, J.S.; Kherani, S.; Desai, S.; Dugel, P.; Kaushal, S.; Cheng, S.H.; Delacono, C.; Purvis, A.; Richards, S.; Le-Halpere, A.; et al. Intravitreous injection of AAV2-sFLT01 in patients with advanced neovascular age-related macular degeneration: A phase 1, open-label trial. Lancet 2017, 390, 50–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Guimaraes, T.A.C.; Georgiou, M.; Bainbridge, J.W.B.; Michaelides, M. Gene therapy for neovascular age-related macular degeneration: Rationale, clinical trials and future directions. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2021, 105, 151–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campochiaro, P.A.; Lauer, A.K.; Sohn, E.H.; Mir, T.A.; Naylor, S.; Anderton, M.C.; Kelleher, M.; Harrop, R.; Ellis, S.; Mitrophanous, K.A. Lentiviral Vector Gene Transfer of Endostatin/Angiostatin for Macular Degeneration (GEM) Study. Hum. Gene Ther. 2017, 28, 99–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ling, S.; Yang, S.; Hu, X.; Yin, D.; Dai, Y.; Qian, X.; Wang, D.; Pan, X.; Hong, J.; Sun, X.; et al. Lentiviral delivery of co-packaged Cas9 mRNA and a Vegfa-targeting guide RNA prevents wet age-related macular degeneration in mice. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2021, 5, 144–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maeda, T.; Sugita, S.; Kurimoto, Y.; Takahashi, M. Trends of Stem Cell Therapies in Age-Related Macular Degeneration. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 1785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashani, A.H.; Lebkowski, J.S.; Rahhal, F.M.; Avery, R.L.; Salehi-Had, H.; Dang, W.; Lin, C.-M.; Mitra, D.; Zhu, D.; Thomas, B.B.; et al. A bioengineered retinal pigment epithelial monolayer for advanced, dry age-related macular degeneration. Sci. Transl. Med. 2018, 10, eaao4097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honda, M.; Asai, T.; Oku, N.; Araki, Y.; Tanaka, M.; Ebihara, N. Liposomes and nanotechnology in drug development: Focus on ocular targets. Int. J. Nanomed. 2013, 8, 495–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kari, O.K.; Tavakoli, S.; Parkkila, P.; Baan, S.; Savolainen, R.; Ruoslahti, T.; Johansson, N.G.; Ndika, J.; Alenius, H.; Viitala, T.; et al. Light-Activated Liposomes Coated with Hyaluronic Acid as a Potential Drug Delivery System. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12, 763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lajunen, T.; Kontturi, L.-S.; Viitala, L.; Manna, M.; Cramariuc, O.; Róg, T.; Bunker, A.; Laaksonen, T.; Viitala, T.; Murtomäki, L.; et al. Indocyanine Green-Loaded Liposomes for Light-Triggered Drug Release. Mol. Pharm. 2016, 13, 2095–2107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Treatment of Age-Related Macular Degeneration with Photodynamic Therapy (TAP) Study Group. Photodynamic therapy of subfoveal choroidal neovascularization in age-related macular degeneration with verteporfin: One-year results of 2 randomized clinical trials—TAP report. Arch. Ophthalmol. 1999, 117, 1329–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamaki, Y. Prospects for nanomedicine in treating age-related macular degeneration. Future Med. 2009, 4, 341–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoon, J.U.; Byun, Y.J.; Koh, H.J. Intravitreal anti-vegf versus photodynamic therapy with verteporfin for treatment of myopic choroidal neovascularization. Retina 2010, 30, 418–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, Y.; Zhao, K.-K.; Feng, D.; Biswal, M.; Zhao, P.-Q.; Wang, Z.-Y.; Zhang, Y. Comparison of the efficacy of anti-VEGF monotherapy versus PDT and intravitreal anti-VEGF combination treatment in AMD: A Meta-analysis and systematic review. Int. J. Ophthalmol. 2016, 9, 1028–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrarca, R.; Jackson, T.L. Radiation therapy for neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Clin. Ophthalmol. 2011, 5, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Jaakkola, A.; Heikkonen, J.; Tommila, P.; Laatikainen, L.; Immonen, I. Strontium Plaque Brachytherapy for Exudative Age-Related Macular Degeneration: Three-year results of a randomized study. Ophthalmology 2005, 112, 567–573.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivagnanavel, V.; Evans, J.R.; Ockrim, Z.; Chong, V. Radiotherapy for neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2004, 5, CD004004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ávila, M.; Farah, M.; Santos, A.; Duprat, J.; Woodward, B.; Nau, J. Twelve-month short-term safety and visual-acuity results from a multicentre prospective study of epiretinal strontium-90 brachytherapy with bevacizumab for the treatment of subfoveal choroidal neovascularisation secondary to age-related macular degenerati. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2009, 93, 305–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, J.R.; Igwe, C.; Jackson, T.; Chong, V. Radiotherapy for neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2020, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodward, B.W. Comparison of Efficacy of Proton Beam and 90Sr/90Y Beta Radiation in Treatment of Exudative Age-Related Macular Degeneration; NeoVista Inc.: Fremont, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Kishan, A.U.; Modjtahedi, B.S.; Morse, L.S.; Lee, P. Radiation Therapy for Neovascular Age-related Macular Degeneration. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. 2013, 85, 583–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sengillo, J.D.; Justus, S.; Tsai, Y.-T.; Cabral, T.; Tsang, S.H. Gene and cell-based therapies for inherited retinal disorders: An update. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part C Semin. Med. Genet. 2016, 172, 349–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Constable, I.; Lai, C.; Magno, A. Gene therapy in neovascular age-related macular degeneration: Three year follow-up of a phase 1 randomised dose escalation trial. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2017, 177, 150–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, G.; Tang, Y.; Wilson, J. Biology of adenovirus vectors with E1 and E4 deletions for liver-directed gene therapy. J. Virol. 1996, 70, 8934–8943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morral, N.; O’Neal, W.; Zhou, H.; Langston, C.; Beaudet, A. Immune Responses to Reporter Proteins and High Viral Dose Limit Duration of Expression with Adenoviral Vectors: Comparison of E2a Wild Type and E2a Deleted Vectors. Hum. Gene Ther. 1997, 8, 1275–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kay, M.A.; Nakai, H. Looking into the safety of AAV vectors. Nat. Cell Biol. 2003, 424, 251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisowski, L.; Tay, S.S.; Alexander, I.E. Adeno-associated virus serotypes for gene therapeutics. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2015, 24, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stieger, K.; Cronin, T.; Bennett, J.; Rolling, F. Adeno-Associated Virus Mediated Gene Therapy for Retinal Degenerative Diseases. Stem Cells Aging 2012, 807, 179–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daya, S.; Berns, K.I. Gene Therapy Using Adeno-Associated Virus Vectors. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2008, 21, 583–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surace, E.M.; Auricchio, A. Versatility of AAV vectors for retinal gene transfer. Vis. Res. 2008, 48, 353–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hareendran, S.; Balakrishnan, B.; Sen, D.; Kumar, S.; Srivastava, A.; Jayandharan, G.R. Adeno-associated virus (AAV) vectors in gene therapy: Immune challenges and strategies to circumvent them. Rev. Med. Virol. 2013, 23, 399–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Everson, E.M.; Trobridge, G.D. Retroviral vector interactions with hematopoietic cells. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2016, 21, 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, M.; Keller, B.; Makalou, N.; Sutton, R.E. Systematic Determination of the Packaging Limit of Lentiviral Vectors. Hum. Gene Ther. 2001, 12, 1893–1905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Booth, C.; Gaspar, H.B.; Thrasher, A.J. Treating Immunodeficiency through HSC Gene Therapy. Trends Mol. Med. 2016, 22, 317–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zufferey, R.; Dull, T.; Manel, R. Self-inactivating lentivirus vector for safe and efficient in vivo gene delivery. J. Virol. 1998, 72, 9873–9880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaw, A.; Cornetta, K. Design and Potential of Non-Integrating Lentiviral Vectors. Biomedicines 2014, 2, 14–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Streilein, J.W. Ocular immune privilege: Therapeutic opportunities from an experiment of nature. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2003, 3, 879–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu-Wai-Man, P. Genetic manipulation for inherited neurodegenerative diseases: Myth or reality? Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2016, 100, 1322–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.; Toyoguchi, M.; Looney, D.J.; Lee, J.; Davidson, M.C.; Freeman, W.R. Efficient gene transfer to retinal pigment epithelium cells with long-term expression. Retina 2005, 25, 193–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mori, K.; Duh, E.; Gehlbach, P.; Ando, A.; Takahashi, K.; Pearlman, J.; Mori, K.; Yang, H.S.; Zack, D.; Ettyreddy, D.; et al. Pigment epithelium-derived factor inhibits retinal and choroidal neovascularization. J. Cell. Physiol. 2001, 188, 253–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mori, K.; Gehlbach, P.; Ando, A.; McVey, D.; Wei, L.; Campochiaro, P.A. Regression of ocular neovascularization in response to increased expression of pigment epithelium-derived factor. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2002, 43, 2428. [Google Scholar]

- Rakoczy, E.P.; Lai, C.-M.; Magno, A.L.; Wikstrom, M.E.; French, M.A.; Pierce, C.M.; Schwartz, S.D.; Blumenkranz, M.S.; Chalberg, T.W.; Degli-Esposti, M.A.; et al. Gene therapy with recombinant adeno-associated vectors for neovascular age-related macular degeneration: 1 year follow-up of a phase 1 randomised clinical trial. Lancet 2015, 386, 2395–2403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constable, I.; Pierce, C.; Lai, C. Phase 2a randomized clinical trial: Safety and post hoc analysis of subretinal rAAV.sFLT-1 for wet age-related macular degeneration. EBioMedicine 2016, 14, 168–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adverum Down after Clinical Development Shift for Gene Therapy Program|BioSpace. Available online: https://www.biospace.com/article/adverum-falls-after-shift-in-clinical-development-for-gene-therapy-program/ (accessed on 26 September 2021).

- Serious Adverse Reaction Halts Gene Therapy for Diabetic Macular Edema. Available online: https://www.modernretina.com/view/serious-adverse-reaction-halts-gene-therapy-for-diabetic-macular-edema (accessed on 26 September 2021).

- Adverum Halt Raises More Gene Therapy Questions|Evaluate. Available online: https://www.evaluate.com/vantage/articles/news/trial-results/adverum-halt-raises-more-gene-therapy-questions (accessed on 26 September 2021).

- Yin, L.; Greenberg, K.; Hunter, J.; Dalkara, D.; Kolstad, K.D.; Masella, B.D.; Wolfe, R.; Visel, M.; Stone, D.; Libby, R.; et al. Intravitreal Injection of AAV2 Transduces Macaque Inner Retina. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2011, 52, 2775–2783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, L.-J.; Xiao, X.; Wu, J.H. Inhibition of corneal neovascularization with endostatin delivered by adeno-associated viral (AAV) vector in a mouse corneal injury model. J. Biomed. Sci. 2007, 14, 313–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uyama, H.; Mandai, M.; Takahashi, M. Stem-cell-based therapies for retinal degenerative diseases: Current challenges in the establishment of new treatment strategies. Dev. Growth Differ. 2021, 63, 59–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mandai, M.; Watanabe, A.; Kurimoto, Y.; Hirami, Y.; Morinaga, C.; Daimon, T.; Fujihara, M.; Akimaru, H.; Sakai, N.; Shibata, Y.; et al. Autologous Induced Stem-Cell–Derived Retinal Cells for Macular Degeneration. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 376, 1038–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Da Cruz, L.; Fynes, K.; Georgiadis, O.; Kerby, J.; Luo, Y.H.; Ahmado, A.; Vernon, A.; Daniels, J.T.; Nommiste, B.; Hasan, S.M.; et al. Phase 1 clinical study of an embryonic stem cell–derived retinal pigment epithelium patch in age-related macular degeneration. Nat. Biotechnol. 2018, 36, 328–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwartz, S.D.; Regillo, C.D.; Lam, B.L.; Eliott, D.; Rosenfeld, P.J.; Gregori, N.Z.; Hubschman, J.-P.; Davis, J.L.; Heilwell, G.; Spirn, M.; et al. Human embryonic stem cell-derived retinal pigment epithelium in patients with age-related macular degeneration and Stargardt’s macular dystrophy: Follow-up of two open-label phase 1/2 studies. Lancet 2015, 385, 509–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugita, S.; Mandai, M.; Hirami, Y.; Takagi, S.; Maeda, T.; Fujihara, M.; Matsuzaki, M.; Yamamoto, M.; Iseki, K.; Hayashi, N.; et al. HLA-Matched Allogeneic iPS Cells-Derived RPE Transplantation for Macular Degeneration. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 2217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sung, Y.; Lee, M.J.; Choi, J.; Jung, S.Y.; Chong, S.Y.; Sung, J.H.; Shim, S.H.; Song, W.K. Long-term safety and tolerability of subretinal transplantation of embryonic stem cell-derived retinal pigment epithelium in Asian Stargardt disease patients. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2021, 10, 1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Robredo, P.; Sancho, A.; Johnen, S.; Recalde, S.; Gama, N.; Thumann, G.; Groll, J.; García-Layana, A. Current Treatment Limitations in Age-Related Macular Degeneration and Future Approaches Based on Cell Therapy and Tissue Engineering. J. Ophthalmol. 2014, 2014, 510285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakrabarty, K.; Shetty, R.; Ghosh, A. Corneal cell therapy: With iPSCs, it is no more a far-sight. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2018, 9, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takagi, S.; Mandai, M.; Gocho, K.; Hirami, Y.; Yamamoto, M.; Fujihara, M.; Sugita, S.; Kurimoto, Y.; Takahashi, M. Evaluation of Transplanted Autologous Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell-Derived Retinal Pigment Epithelium in Exudative Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Ophthalmol. Retin. 2019, 3, 850–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gandhi, J.K.; Mano, F.; Iezzi, R.; LoBue, S.A.; Holman, B.H.; Fautsch, M.P.; Olsen, T.W.; Pulido, J.S.; Marmorstein, A.D. Fibrin hydrogels are safe, degradable scaffolds for sub-retinal implantation. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0227641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gandhi, J.K.; Manzar, Z.; Bachman, L.A.; Andrews-Pfannkoch, C.; Knudsen, T.; Hill, M.; Schmidt, H.; Iezzi, R.; Pulido, J.S.; Marmorstein, A.D. Fibrin hydrogels as a xenofree and rapidly degradable support for transplantation of retinal pigment epithelium monolayers. Acta Biomater. 2018, 67, 134–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuriyan, A.E.; Albini, T.A.; Townsend, J.H.; Rodriguez, M.; Pandya, H.K.; Leonard, R.E.; Parrott, M.B.; Rosenfeld, P.J.; Flynn, H.W., Jr.; Goldberg, J.L. Vision Loss after Intravitreal Injection of Autologous ‘Stem Cells’ for AMD. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 376, 1047–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Molecular Target | Molecule Name | Specific Molecular Target | Format | Clinical Progress | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VEGF | Bevacizumab | All VEGF isoforms | Humanized full length monoclonal IgG1 | Used clinically/Off-label | [40] |

| Ranibizumab | All VEGF-A isoforms including VEGF 165, VEGF 121, and VEGF 110 | Fragment of humanized monoclonal IgG1k | Used clinically | [44,45] | |

| Aflibercept | VEGF-A, B, C, and D isoforms | Fusion protein composed of binding domains of VEGFR-1 and 2 fused with the Fc region of IgG1 | Used clinically | [46] | |

| Pegaptanib | VEGF 165 isoform | PEGylated form of a neutralizing RNA aptamer | Practically off the market or used in cases where the patient is already using | [47] | |

| Brolucizumab | All VEGF isoforms | scFv | Used clinically | [48] | |

| Abicipar pegal (MP0112) | All VEGF-A isoforms | PEGylated DARPin | Phase III clinical trials | [49] | |

| Conbercept | VEGF-A, B and C | Fc fusion | Phase III clinical trials with Lucentis® | [50] | |

| KSI—301 | VEGF-A | IgG1 biopolymer conjugate | Phase II clinical trials | [51] | |

| OPT—302 | VEGF-C and VEGF-D | Fc fusion | Phase III clinical trials | [52] | |

| PDGF | Pegpleranib | PDGF-B | 32-nucleotide PEGylated DNA aptamer | Phase III Clinical trials with Lucentis® | [53] |

| Rinucumab | PDGF-B | IgG4 | Phase II Clinical trials with Eylea® | [54] | |

| ANG | Nesvacumab | ANG-2 | IgG1 | Discontinued Phase II Clinical trials with Eylea® | [43] |

| Bispecific targets | IBI302 | VEGF/ Complement Activation System | Recombinant human anti-VEGF- and anti-complement bispecific fusion protein | Phase I Clinical trials | [55] |

| RG7716 | VEGF/ANG-2 | Bispecific domain-exchanged mAb (CrossMAb) | Phase III Clinical trials | [56] | |

| Small molecules and others | Triamcinolone acetonide | Multiple targets | Synthetic corticosteroid | Phase III Clinical trials with PDT | [57] |

| Anecortave acetate | Protease | Glucocorticoid analogue | Phase II Clinical trials with PDT | [58] | |

| Sorafenib | VEGFR-1 and 2 | TKI | Discontinued clinical trials | [59] | |

| Sunitinib Malate | TK receptors | TKI | Formulation Development | [60,61] | |

| Dexamethasone | Multiple targets | Synthetic glucocorticoid | Phase II clinical trials | [62] | |

| Levodopa | GPR143, PEDF, and VEGF | Amino acid precursor of dopamine | Phase II clinical trials | [63,64,65] |

| Drug Name | Target | Sponsors | Phase | Status | ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Faricimab (RG7716) | VEGF-A, ANG-2 | Hoffmann-La Roche | 3 | Active, Not recruiting/Enrolling by invitation/Recruiting | NCT03823287 NCT03823300 NCT04777201 |

| 2 | Completed | NCT03038880 NCT02484690 | |||

| Faricimab (RO6867461) | VEGF-A, ANG-2 | Chugai Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd. | 1 | Completed | JapicCTI-173634 |

| IBI302 | VEGF, CR1 | Innovent Biologics Co. Ltd. | 1 | Active, Not yet recruiting | NCT03814291 NCT04370379 |

| 2 | Not yet recruiting | NCT04820452 | |||

| BI 836880 | VEGF-A, ANG-2 | Boehringer Ingelheim | 1 | Recruiting | NCT03861234 |

| RC28-E | VEGF, FGFR | RemeGen Co. Ltd. | 1/2 | Active, Not recruiting | NCT04270669 |

| 1 | Completed | NCT03777254 |

| Type of Molecule | Vitreal Clearance | Target Concentration in Vitreous | Required Dose for 3 Months | Required Dose for 12 Months |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Small molecule (500 Da) | 0.05–1 mL/h | 100 µM | 30 mg | 120 mg |

| 10 µM | 3 mg | 12 mg | ||

| 1 µM | 305 µg | 1.2 mg | ||

| 0.1 µM | 30 µg | 120 µg | ||

| Antibodies (149 k Da) | 0.01–0.07 mL/h | 10 µM | 55 mg | 220 mg |

| 1 µM | 5.5 mg | 22 mg | ||

| 0.1 µM | 550 µg | 2.2 mg | ||

| 10 nM | 55 µg | 220 µg |

| Therapeutic Modality | Active Ingredient | Delivery System | Clinical Progress | Highlights | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Port Delivery System | Ranibizumab | Ocular implant | Clinical development | Sustained and controlled release of Ranibizumab to neutralize VEGF | [158] |

| Photodynamic Therapy | Verteporfin | Liposomes | Approved for clinical use (Visudyne®) | Cessation of bleeding and selective occlusion of the newly formed blood vessels along with decreased exudate formation | [165] |

| Verteporfin | Cationic liposomes | Exploratory studies | CNV occlusion and reduced retinal deterioration compared to Visudyne® | [168] | |

| Paclitaxel/Succinyl-paclitaxel | Cationic liposomes | Exploratory studies | Inhibition of angiogenesis in rat models | [168] | |

| Hypocrellin B | Liposomes | Exploratory studies | Significant reduction in CNV area with reduced tissue damage | [169] | |

| Edaravone | Liposomes | Exploratory studies | Inhibition of ROS generation, reduced thickness of outer nuclear layer and no cytotoxicity | [170] | |

| Calcein | Gold nanoparticles | Exploratory studies | Light activated sustained and controlled drug release | [171] | |

| Calcein | ICG loaded liposomes | Exploratory studies | Light induced improved permeability of liposomes to control drug release | [172] | |

| Photocyanine and Sorafenib | RGD modified liposomes | Exploratory studies | Reduced CNV area and improved safety profile | [173] | |

| Verteporfin | Liposomes | Exploratory studies | Combination with anti-VEGF agents is more efficacious than anti-VEGF monotherapy | [174] | |

| Gene therapy | PEDF gene | AAV | Clinical trials | Inhibition of angiogenesis | [175] |

| PEDF gene | E1-, partial E3-, E4-deleted AAV | Clinical trials | No deleterious adverse effects were observed, however no concrete evidence is available to show the improved therapeutic efficacy and the relation between response and dose escalation | [176] | |

| sFLT-1 | Recombinant AAV | Clinical trials | Antiangiogenic activity and reduced progression of CNV but no promising results | [177,178,179] | |

| ADVM-022 and ADVM-032 | Vector capsid, AAV.7m8 | Clinical trials | Antiangiogenic activity in murine models with laser induced CNV | [180] | |

| sFLT1 | AAV2 with CBA promoter | Clinical trials | Higher expression with promoter introduction, however disappointing results | [181] | |

| Anti-VEGF mAb | AAV8 vector, RGX-314 | Clinical trials | High protein expression therefore tolerability is being studied | [182] | |

| Angiostatin and Endostatin | EIAV-lentiviral particle | Clinical trials | No specific complications observed and high levels of active maintained. | [183] | |

| mLP-CRISPR | Lentiviral particle | Clinical trials | Prevented progression of nAMD and no specific immune responses | [184] | |

| Stem cell therapy | Autologous iPSC derived RPE cells | Cell sheet | Clinical trials | Retained stability of transplanted sheet, corrected vision and no rejection of graft observed after 5 years | [7] |

| Allogeneic iPSC derived RPE cells | Cell suspension | Clinical trials | No specific cases of graft rejection were observed and mild cases of immune rejection that can be managed | [185] | |

| Allogeneic ESC derived RPE cells | Cell sheet | Clinical trials | Few cases of immediate adverse effect observed, no immune rejection responses. | [186] |

| Expressed Gene | Vector | Phase | Route of Delivery | Status | Sponsor | Trial Registration Number |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PEDF | AAV5 | I | Intravitreal | Completed | GenVec | NCT00109499 |

| sFLT01 | AAV2 | I/II | Subretinal | Completed | Lions Eye Institute, Adverum Biotechnologies | NCT01494805 |

| Aflibercept | AAV2 | I | Intravitreal | Ongoing | Adverum Biotechnologies | NCT03748784 |

| sFLT01 | AAV2 | I | Intravitreal | Completed | Sanofi Genzyme | NCT01024998 |

| Anti-VEGF Fab | AAV8 | I/IIa | Subretinal | Ongoing | Regenxbio | NCT03066258 |

| Endostatin and angiostatin | EIAV | I | Subretinal | Completed | Oxford BioMedica | NCT01301443 |

| sCD59 | AAV2 | I | Intravitreal | Ongoing | Hemera Biosciences | NCT03585556 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sarkar, A.; Junnuthula, V.; Dyawanapelly, S. Ocular Therapeutics and Molecular Delivery Strategies for Neovascular Age-Related Macular Degeneration (nAMD). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 10594. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms221910594

Sarkar A, Junnuthula V, Dyawanapelly S. Ocular Therapeutics and Molecular Delivery Strategies for Neovascular Age-Related Macular Degeneration (nAMD). International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2021; 22(19):10594. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms221910594

Chicago/Turabian StyleSarkar, Aira, Vijayabhaskarreddy Junnuthula, and Sathish Dyawanapelly. 2021. "Ocular Therapeutics and Molecular Delivery Strategies for Neovascular Age-Related Macular Degeneration (nAMD)" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 22, no. 19: 10594. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms221910594

APA StyleSarkar, A., Junnuthula, V., & Dyawanapelly, S. (2021). Ocular Therapeutics and Molecular Delivery Strategies for Neovascular Age-Related Macular Degeneration (nAMD). International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 22(19), 10594. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms221910594