ITGB6-Knockout Suppresses Cholangiocarcinoma Cell Migration and Invasion with Declining PODXL2 Expression

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

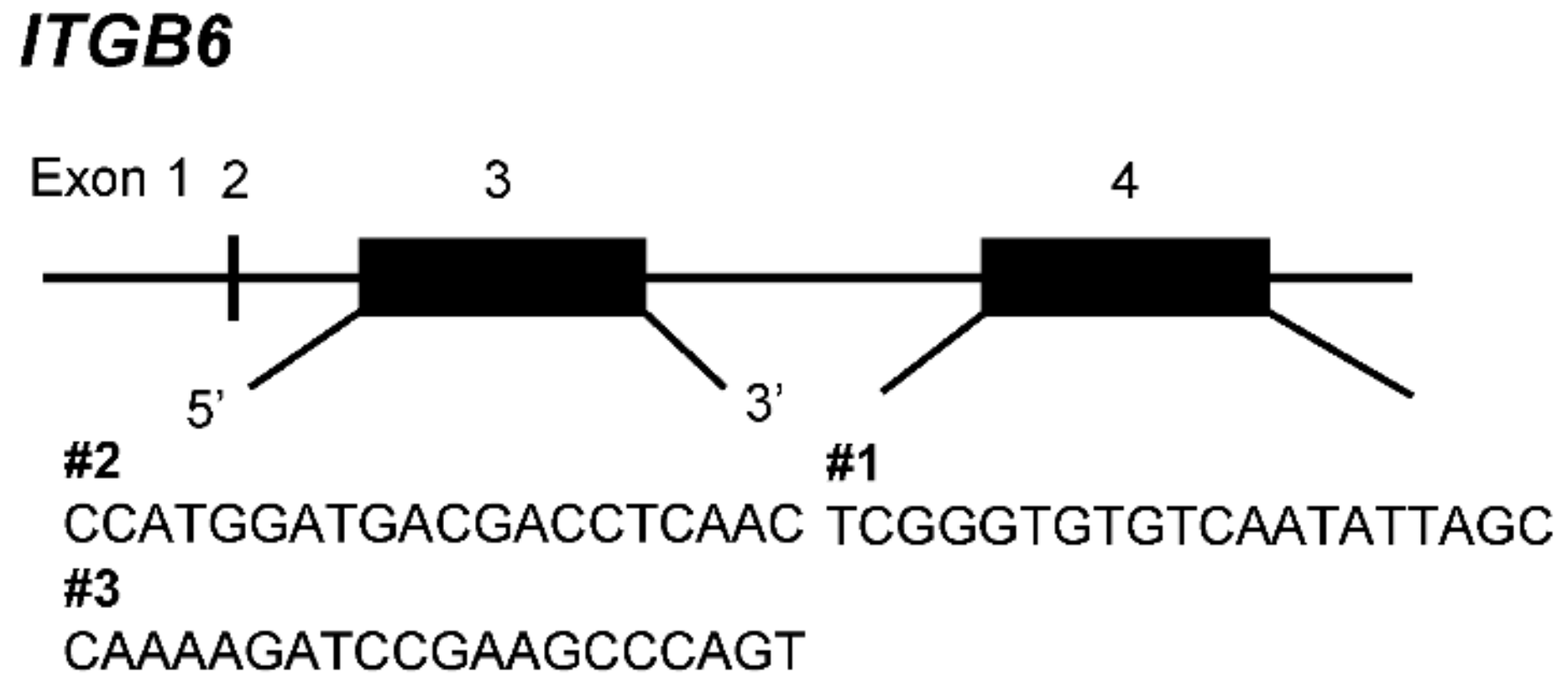

2.1. Establishment of ITGB6-Knockout (ko) Cell Lines

2.2. ITGB6-Knockout Reduced the Migration and Invasion of iCCA Cells

2.3. ITGB6-Knockout Inhibited Colony Formation and Induced Cell Cycle Dysregulation in iCCA Cells

2.4. RNA-Seq and Real-Time PCR Analysis Revealed a Significant Decrease in PODXL2 Expression in ITGB6-ko Cells

2.5. Immunofluorescence Staining of PODXL2, CEACAM6, S100P, MUC1, and CD56

2.6. Relationship between PODXL2 Expression and Clinicopathological Features in Patients with Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma (iCCA)

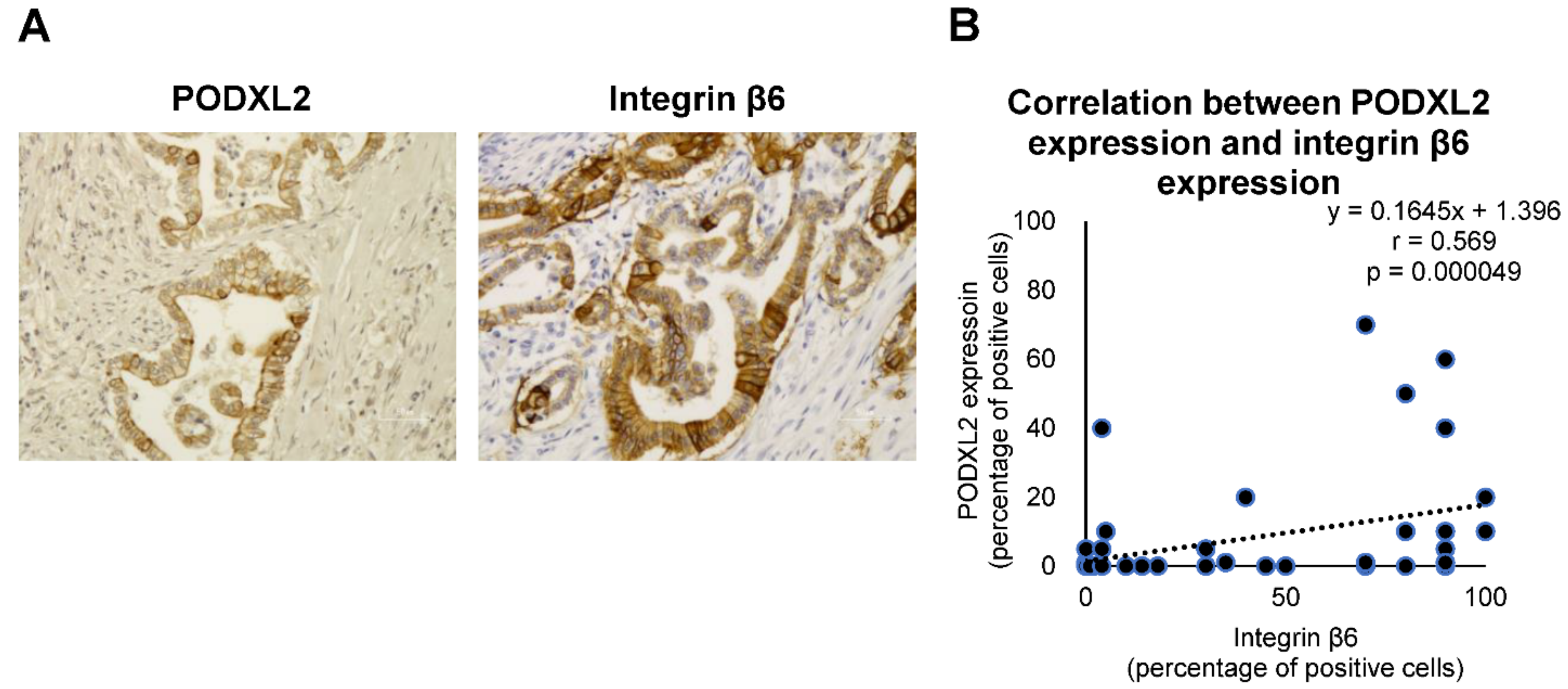

2.7. Correlation between Integrin β6 Expression and PODXL2 Expression in iCCA Tissues

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Cell Line and Cell Culture

4.2. Patients and Tissue Samples

4.3. Transfection and Genomic Cleavage Detection

4.4. Single-Cell Cloning and Direct Sequence Analysis

4.5. Immunofluorescence Staining

4.6. Flow Cytometry

4.7. In Vitro Transwell Migration and Invasion Assays

4.8. Wound-Healing Assay

4.9. Colony Formation Assay

4.10. Cell Cycle Analysis

4.11. RNA-Seq Analysis

4.12. Real-Time PCR

4.13. Immunohistochemistry and Evaluation

4.14. Statistical Analysis

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rizvi, S.; Khan, S.A.; Hallemeier, C.L.; Kelley, R.K.; Gores, G.J. Cholangiocarcinoma — evolving concepts and therapeutic strategies. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 15, 95–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clements, O.; Eliahoo, J.; Kim, J.U.; Taylor-Robinson, S.D.; Khan, S.A. Risk factors for intrahepatic and extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Hepatol. 2020, 72, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sirica, A.E.; Gores, G.J.; Groopman, J.D.; Selaru, F.M.; Strazzabosco, M.; Wang, X.W.; Zhu, A.X. Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma: Continuing Challenges and Translational Advances. Hepatology 2019, 69, 1803–1815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakanuma, Y.; Klimstra, D.; Komuta, M.; Zen, Y. Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. In WHO Classification of Tumors: Digestive System Tumours, 5th ed.; Lokuhetty, D., White, V.A., Watanabe, R., Cree, I.A., Eds.; International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC): Lyon, France, 2019; pp. 254–259. [Google Scholar]

- Sia, D.; Hoshida, Y.; Villanueva, A.; Roayaie, S.; Ferrer-Fabrega, J.; Tabak, B.; Peix, J.; Sole, M.; Tovar, V.; Alsinet, C.; et al. Integrative Molecular Analysis of Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma Reveals 2 Classes That Have Different Outcomes. Gastroenterology 2013, 144, 829–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizvi, S.; Gores, G.J. Emerging molecular therapeutic targets for cholangiocarcinoma. J. Hepatol. 2017, 67, 632–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soejima, Y.; Inoue, M.; Takahashi, Y.; Uozaki, H.; Sawabe, M.; Fukusato, T. Integrins αvβ6, α6β4 and α3β1 are down-regulated in cholangiolocellular carcinoma but not cholangiocarcinoma. Hepatol. Res. 2014, 44, E320–E334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hynes, R.O. Integrins: Bidirectional, Allosteric Signaling Machines. Cell 2002, 110, 673–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kechagia, J.Z.; Ivaska, J.; Roca-Cusachs, P. Integrins as biomechanical sensors of the microenvironment. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2019, 20, 457–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamidi, H.; Ivaska, J. Every step of the way: Integrins in cancer progression and metastasis. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2018, 18, 533–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, J.; Giancotti, F.G. Integrin Signaling in Cancer: Mechanotransduction, Stemness, Epithelial Plasticity, and Therapeutic Resistance. Cancer Cell 2019, 35, 347–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koivisto, L.; Bi, J.; Häkkinen, L.; Larjava, H. Integrin αvβ6: Structure, function and role in health and disease. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2018, 99, 186–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desnoyers, A.; González, C.; Pérez-Segura, P.; Pandiella, A.; Amir, E.; Ocaña, A. Integrin ανβ6 Protein Expression and Prognosis in Solid Tumors: A Meta-Analysis. Mol. Diagn. Ther. 2020, 24, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieberler, M.; Reuning, U.; Reichart, F.; Notni, J.; Wester, H.-J.; Schwaiger, M.; Weinmüller, M.; Räder, A.; Steiger, K.; Kessler, H. Exploring the Role of RGD-Recognizing Integrins in Cancer. Cancers 2017, 9, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.-Y. Integrin αvβ6 sustains and promotes tumor invasive growth in colon cancer progression. World J. Gastroenterol. 2015, 21, 7457–7467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reader, C.S.; Vallath, S.; Steele, C.W.; Haider, S.; Brentnall, A.; Desai, A.; Moore, K.M.; Jamieson, N.B.; Chang, D.; Bailey, P.; et al. The integrin αvβ6 drives pancreatic cancer through diverse mechanisms and represents an effective target for therapy. J. Pathol. 2019, 249, 332–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.-B.; Deng, B.; Huang, Y.-S.; Xiao, W.-M.; Wu, J.; Zhang, Y.-Q.; Wang, Y.-Z.; Wu, D.-C.; Lu, G.-T.; Wu, K.-Y. A High Level of Integrin α6 Expression in Human Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma Cells Is Associated with a Migratory and Invasive Phenotype. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2013, 58, 1627–1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Biswas, S.; Liang, B.; Zou, X.; Shan, L.; Li, Y.; Fang, R.; Niu, J. Integrin β6 serves as an immunohistochemical marker for lymph node metastasis and promotes cell invasiveness in cholangiocarcinoma. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 30081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Dong, X.; Shang, Y.; Sun, F.; Niu, J.; Li, F. Integrin αvβ6 predicts poor prognosis and promotes resistance to cisplatin in hilar cholangiocarcinoma. Pathol. Res. Pract. 2020, 216, 153022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soejima, Y.; Takeuchi, M.; Akashi, T.; Sawabe, M.; Fukusato, T. β4 and β6 Integrin Expression Is Associated with the Subclassification and Clinicopathological Features of Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liau, J.-Y.; Tsai, J.-H.; Yuan, R.-H.; Chang, C.-N.; Lee, H.-J.; Jeng, Y.-M. Morphological subclassification of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: Etiological, clinicopathological, and molecular features. Mod. Pathol. 2014, 27, 1163–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayashi, A.; Misumi, K.; Shibahara, J.; Arita, J.; Sakamoto, Y.; Hasegawa, K.; Kokudo, N.; Fukayama, M. Distinct Clinicopathologic and Genetic Features of 2 Histologic Subtypes of Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2016, 40, 1021–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sassetti, C.; Van Zante, A.; Rosen, S.D. Identification of Endoglycan, a Member of the CD34/Podocalyxin Family of Sialomucins. J. Biol. Chem. 2000, 275, 9001–9010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fieger, C.B.; Sassetti, C.M.; Rosen, S.D. Endoglycan, a Member of the CD34 Family, Functions as an L-selectin Ligand through Modification with Tyrosine Sulfation and Sialyl Lewis x. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 27390–27398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerr, S.C.; Fieger, C.B.; Snapp, K.R.; Rosen, S.D. Endoglycan, a Member of the CD34 Family of Sialomucins, Is a Ligand for the Vascular Selectins. J. Immunol. 2008, 181, 1480–1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taniuchi, K.; Furihata, M.; Naganuma, S.; Sakaguchi, M.; Saibara, T. Overexpression of PODXL/ITGB1 and BCL7B/ITGB1 accurately predicts unfavorable prognosis compared to the TNM staging system in postoperative pancreatic cancer patients. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0217920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.; Du, W.; Li, M.; Yan, M.; Zheng, F. PODXL might be a new prognostic biomarker in various cancers: A meta-analysis and sequential verification with TCGA datasets. BMC Cancer 2020, 20, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.-Y.; Wang, C.-Y.; Phan, N.N.; Chiao, C.-C.; Li, C.-Y.; Sun, Z.; Hung, J.-H.; Chen, Y.-L.; Yen, M.-C.; Weng, T.-Y.; et al. PODXL2 maintains cellular stemness and promotes breast cancer development through the Rac1/Akt pathway. Int. J. Med. Sci. 2020, 17, 1639–1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Saber, A.; Haisma, H.J. CRISPR/Cas9: A powerful tool for identification of new targets for cancer treatment. Drug Discov. Today 2019, 24, 955–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, T.; Rindtorff, N.; Betge, J.; Ebert, M.P.; Boutros, M. CRISPR/Cas9 for cancer research and therapy. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2019, 55, 106–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ran, F.A.; Hsu, P.D.; Lin, C.-Y.; Gootenberg, J.; Konermann, S.; Trevino, A.E.; Scott, D.A.; Inoue, A.; Matoba, S.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Double Nicking by RNA-Guided CRISPR Cas9 for Enhanced Genome Editing Specificity. Cell 2013, 154, 1380–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eberlein, C.; Kendrew, J.; McDaid, K.; Alfred, A.; Kang, J.S.; Jacobs, V.N.; Ross, S.J.; Rooney, C.; Smith, N.R.; Rinkenberger, J.; et al. A human monoclonal antibody 264RAD targeting αvβ6 integrin reduces tumour growth and metastasis, and modulates key biomarkers in vivo. Oncogene 2012, 32, 4406–4416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hausner, S.H.; Bold, R.J.; Cheuy, L.Y.; Chew, H.K.; Daly, M.E.; Davis, R.A.; Foster, C.C.; Kim, E.J.; Sutcliffe, J.L. Preclinical Development and First-in-Human Imaging of the Integrin αvβ6 with [18F]αvβ6-Binding Peptide in Metastatic Carcinoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2018, 25, 1206–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyagiwa, M.; Ichida, T.; Tokiwa, T.; Sato, J.; Sasaki, H. A new human cholangiocellular carcinoma cell line (HuCC-T1) producing carbohydrate antigen 19/9 in serum-free medium. Vitr. Cell. Dev. Biol. - Anim. 1989, 25, 503–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kusaka, Y.; Tokiwa, T.; Sato, J. Establishment and characterization of a cell line from a human cholangiocellular carcinoma. Res. Exp. Med. 1988, 188, 367–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| HuCCT1 | Sequence of Target Genes | Results | Amino Acid |

|---|---|---|---|

| wt | (T)CCATGGATGACGACCTCAAC | SMDDDLN | |

| ITGB6-ko 1 | (T)CCATTGGATGACGACCTCAAC | +1 | SIG(STOP) |

| ITGB6-ko 2 | (T)CCATTGGATGACGACCTCAAC | +1 | SIG(STOP) |

| ATG----------ACCTCAACACAATAAAGG | −25 | MTSTQ(STOP) |

| Entrez Gene ID | Gene Symbol | Gene Name | Log2 Fold Change | Adjusted p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 50512 | PODXL2 | podocalyxin-like 2 | −7.50 | 0.021 |

| 5915 | RARB | retinoic acid receptor beta | −4.42 | 0.015 |

| 93659 | CGB5 | chorionic gonadotropin subunit beta 5 | −2.91 | 0.017 |

| 23584 | VSIG2 | V-set and immunoglobulin domain-containing 2 | −2.88 | 0.023 |

| 9075 | CLDN2 | claudin 2 | −2.82 | 0.021 |

| 79966 | SCD5 | stearoyl-CoA desaturase 5 | −2.59 | 0.045 |

| 4495 | MT1G | metallothionein 1G | −2.42 | 0.045 |

| 6273 | S100A2 | S100 calcium-binding protein A2 | −2.23 | 0.025 |

| 9022 | CLIC3 | chloride intracellular channel 3 | −1.89 | 0.017 |

| 725 | C4BPB | complement component 4-binding protein beta | −1.83 | 0.045 |

| 56925 | LXN | latexin | −1.74 | 0.039 |

| 7103 | TSPAN8 | tetraspanin 8 | −1.53 | 0.042 |

| 5054 | SERPINE1 | serpin family E member 1 | −1.51 | 0.023 |

| 3956 | LGALS1 | galectin 1 | −1.35 | 0.017 |

| 8263 | F8A1 | coagulation factor VIII-associated 1 | −1.34 | 0.026 |

| 230 | ALDOC | aldolase, fructose-bisphosphate C | −1.21 | 0.019 |

| 1075 | CTSC | cathepsin C | −1.15 | 0.018 |

| 6319 | SCD | stearoyl-CoA desaturase | −1.12 | 0.007 |

| 3149 | HMGB3 | high mobility group box 3 | −1.08 | 0.021 |

| 39 | ACAT2 | acetyl-CoA acetyltransferase 2 | −1.03 | 0.017 |

| Entrez Gene ID | Gene Symbol | Gene Name | Log2 Fold Change | Adjusted p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3620 | IDO1 | indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase 1 | 4.88 | 0.036 |

| 2537 | IFI6 | interferon alpha inducible protein 6 | 3.41 | 0.044 |

| 4680 | CEACAM6 | CEA cell adhesion molecule 6 | 3.05 | 0.028 |

| 91543 | RSAD2 | radical S-adenosyl methionine domain-containing 2 | 2.91 | 0.017 |

| 27074 | LAMP3 | lysosomal associated membrane protein 3 | 2.90 | 0.015 |

| 4600 | MX2 | MX dynamin-like GTPase 2 | 2.84 | 0.017 |

| 4599 | MX1 | MX dynamin-like GTPase 1 | 2.79 | 0.030 |

| 4939 | OAS2 | 2’-5’-oligoadenylate synthetase 2 | 2.67 | 0.017 |

| 8638 | OASL | 2’-5’-oligoadenylate synthetase-like | 2.67 | 0.014 |

| 8519 | IFITM1 | interferon-induced transmembrane protein 1 | 2.62 | 0.040 |

| 9636 | ISG15 | ISG15 ubiquitin-like modifier | 2.61 | 0.008 |

| 115361 | GBP4 | guanylate-binding protein 4 | 2.57 | 0.047 |

| 3437 | IFIT3 | interferon-induced protein with tetratricopeptide repeats 3 | 2.55 | 0.017 |

| 81030 | ZBP1 | Z-DNA-binding protein 1 | 2.48 | 0.011 |

| 4938 | OAS1 | 2’-5’-oligoadenylate synthetase 1 | 2.43 | 0.008 |

| 10406 | WFDC2 | WAP four-disulfide core domain 2 | 2.38 | 0.031 |

| 3075 | CFH | complement factor H | 2.38 | 0.022 |

| 3434 | IFIT1 | interferon-induced protein with tetratricopeptide repeats 1 | 2.36 | 0.017 |

| 25984 | KRT23 | keratin 23 | 2.31 | 0.008 |

| 3433 | IFIT2 | interferon-induced protein with tetratricopeptide repeats 2 | 2.30 | 0.018 |

| Number of Cases (n = 52) | PODXL2 Expression | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative (n = 35) | Positive (n = 17) | p-Value | |||

| Gender | Male | 39 | 26 | 13 | 0.575 |

| Female | 13 | 9 | 4 | ||

| Age (mean) (years) | 73.9 (39–84) | 73.7 (51–81) | 0.731 | ||

| Tumor size (mean) (mm) | 66.2 (18–220) | 63.9 (20–114) | 0.519 | ||

| Localization | Peripheral | 41 | 31 | 10 | 0.0197 * |

| Non-peripheral | 11 | 4 | 7 | ||

| Macroscopic | MF | 46 | 33 | 13 | 0.0808 |

| type | MF + PI, IG + PI, PI | 6 | 2 | 4 | |

| Histological | Well | 7 | 3 | 4 | 0.0104 * |

| differentiation | Moderate | 32 | 19 | 13 | |

| Poor | 13 | 13 | 0 | ||

| Growth type | Expansive | 24 | 20 | 4 | 0.0223 * |

| Infiltrative | 28 | 15 | 13 | ||

| Serosa invasion | + | 25 | 13 | 12 | 0.0239 * |

| − | 27 | 22 | 5 | ||

| Portal vein | + | 42 | 27 | 15 | 0.290 |

| invasion | − | 10 | 8 | 2 | |

| Hepatic vein | + | 22 | 13 | 9 | 0.217 |

| invasion | − | 30 | 22 | 8 | |

| Hepatic artery | + | 5 | 3 | 2 | 0.533 |

| invasion | − | 47 | 32 | 15 | |

| Bile duct | + | 27 | 13 | 13 | 0.0038 ** |

| invasion | − | 25 | 22 | 3 | |

| Intrahepatic | + | 21 | 12 | 9 | 0.162 |

| metastasis | − | 31 | 23 | 8 | |

| Lymph node | + | 14 | 8 | 6 | 0.266 |

| metastasis | − | 38 | 27 | 11 | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Soejima, Y.; Takeuchi, M.; Miyamoto, N.; Sawabe, M.; Fukusato, T. ITGB6-Knockout Suppresses Cholangiocarcinoma Cell Migration and Invasion with Declining PODXL2 Expression. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 6303. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22126303

Soejima Y, Takeuchi M, Miyamoto N, Sawabe M, Fukusato T. ITGB6-Knockout Suppresses Cholangiocarcinoma Cell Migration and Invasion with Declining PODXL2 Expression. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2021; 22(12):6303. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22126303

Chicago/Turabian StyleSoejima, Yurie, Miho Takeuchi, Nao Miyamoto, Motoji Sawabe, and Toshio Fukusato. 2021. "ITGB6-Knockout Suppresses Cholangiocarcinoma Cell Migration and Invasion with Declining PODXL2 Expression" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 22, no. 12: 6303. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22126303

APA StyleSoejima, Y., Takeuchi, M., Miyamoto, N., Sawabe, M., & Fukusato, T. (2021). ITGB6-Knockout Suppresses Cholangiocarcinoma Cell Migration and Invasion with Declining PODXL2 Expression. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 22(12), 6303. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22126303