From Metabolism to Genetics and Vice Versa: The Rising Role of Oncometabolites in Cancer Development and Therapy

Abstract

1. The Rebirth of Cancer Metabolism

2. Oncometabolites: The Emerging of a New Paradigm

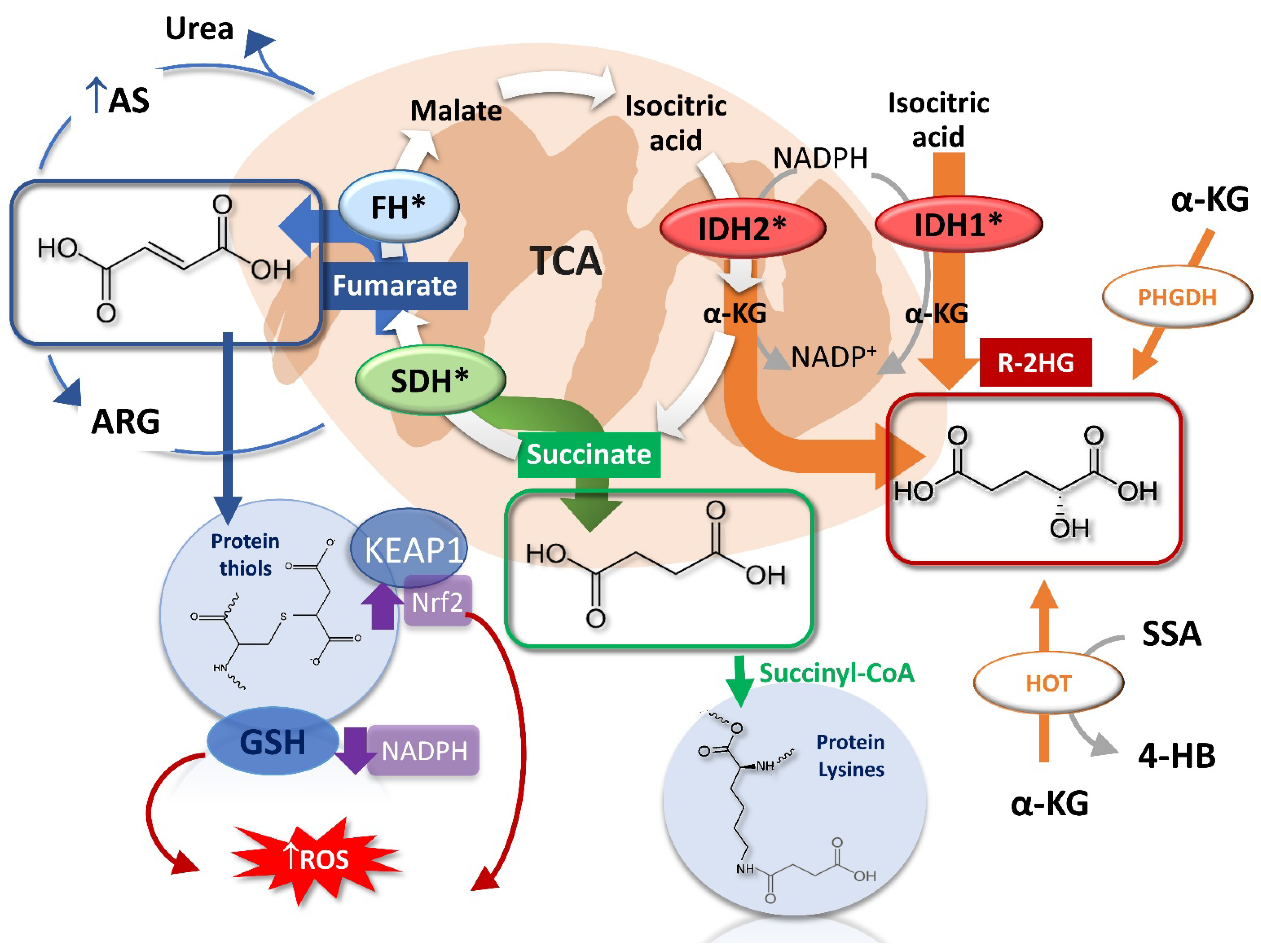

2.1. The Succinate

2.2. The Fumarate

2.3. The R-2-Hydroxyglutarate

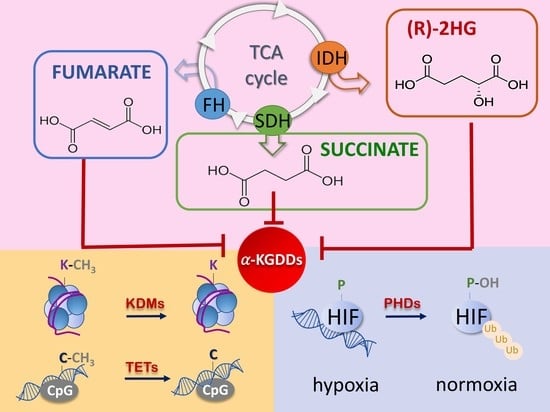

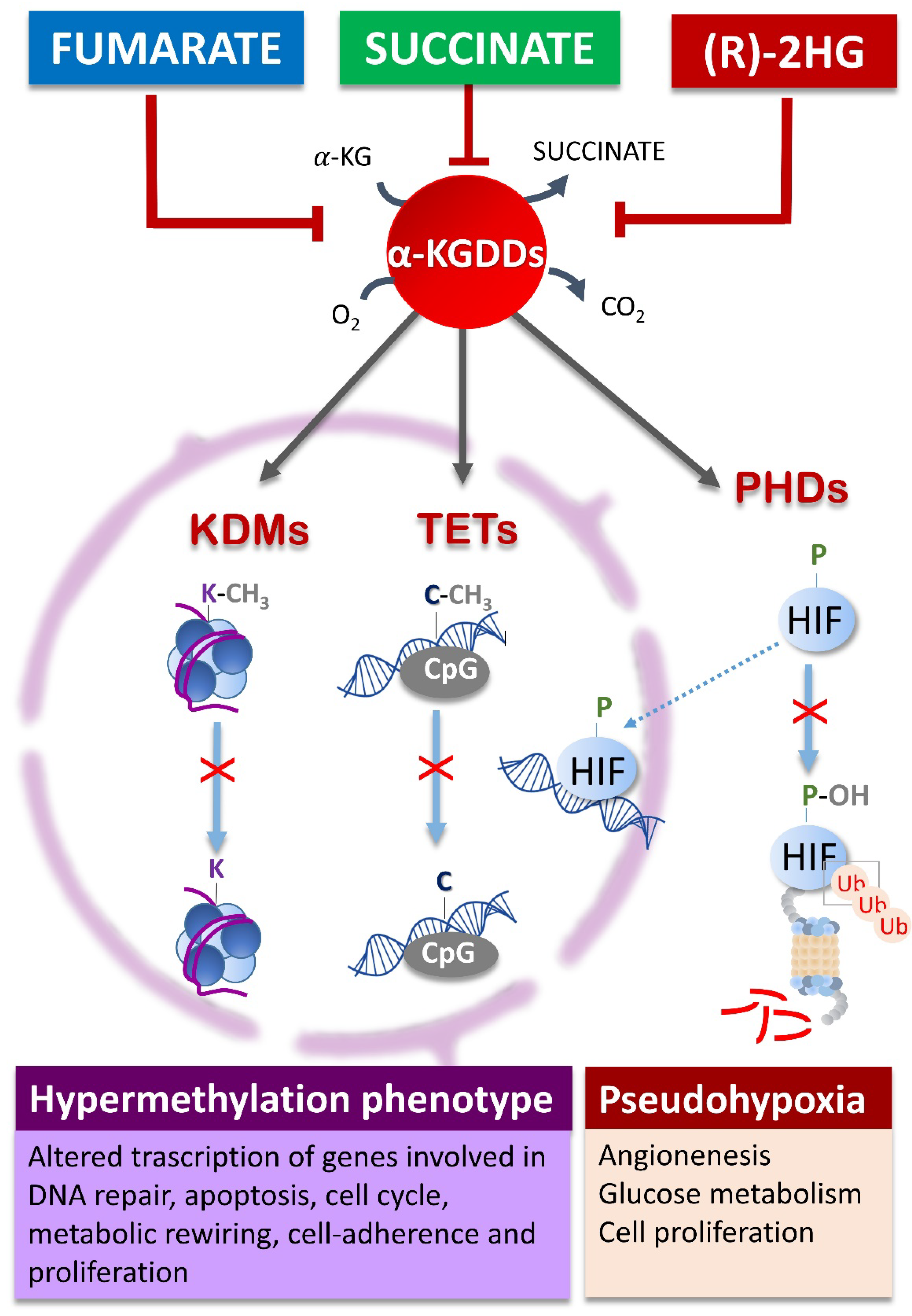

3. Oncometabolites Mechanism of Cancer Induction

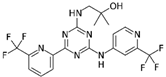

4. Targeted Therapies

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Warburg, O. Beobachtungen über die oxydationsprozesse im seeigelei. Biol. Chem. 1908, 57, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warburg, O. On Respiratory Impairment in Cancer Cells. Science 1956, 124, 269–270. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Warburg, O.; Wind, F.; Negelein, E. The metabolism of tumors in the body. J. Gen. Physiol. 1927, 8, 519–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warburg, O.; Minami, S. Versuche an Überlebendem Carcinom-gewebe. Klin. Wochenschr. 1923, 2, 776–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warburg, O. On the Origin of Cancer Cells. Science 1956, 123, 309–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinhouse, S. Studies on the Fate of Isotopically Labeled Metabolites in the Oxidative Metabolism of Tumors. Cancer Res. 1951, 11, 585–591. [Google Scholar]

- Boveri, T. The Origin of Malignant Tumors; The Williams & Wilkins Company: Baltimore, MD, USA, 1929. [Google Scholar]

- Duesberg, P.H.; Vogt, P.K. Differences between the Ribonucleic Acids of Transforming and Nontransforming Avian Tumor Viruses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1970, 67, 1673–1680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, G.S. Rous Sarcoma Virus: A Function Required for the Maintenance of the Transformed State. Nature 1970, 227, 1021–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rous, P. A sarcoma of the fowl transmissible by an agent separable from the tumor cells. J. Exp. Med. 1911, 13, 397–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toyoshima, K.; Vogt, P.K. Temperature Sensitive Mutants of an Avian Sarcoma Virus. Virology 1969, 39, 930–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stehelin, D.; Varmus, H.E.; Bishop, J.M.; Vogt, P.K. DNA Related to the Transforming Gene(s) of Avian Sarcoma Viruses Is Present in Normal Avian DNA. Nature 1976, 260, 170–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirsten, W.H.; Mayer, L.A. Morphologic Responses to a Murine Erythroblastosis Virus. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1967, 39, 311–335. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, J.J. An unidentified virus which causes the rapid production of tumours in mice. Nature 1964, 204, 1104–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Der, C.J.; Krontiris, T.G.; Cooper, G.M. Transforming Genes of Human Bladder and Lung Carcinoma Cell Lines Are Homologous to the Ras Genes of Harvey and Kirsten Sarcoma Viruses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1982, 79, 3637–3640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parada, L.F.; Tabin, C.J.; Shih, C.; Weinberg, R.A. Human EJ Bladder Carcinoma Oncogene Is Homologue of Harvey Sarcoma Virus Ras Gene. Nature 1982, 297, 474–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, E.; Martin-Zanca, D.; Reddy, E.P.; Pierotti, M.A.; Della Porta, G.; Barbacid, M. Malignant Activation of a K-Ras Oncogene in Lung Carcinoma but Not in Normal Tissue of the Same Patient. Science 1984, 223, 661–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalla-Favera, R.; Bregni, M.; Erikson, J.; Patterson, D.; Gallo, R.C.; Croce, C.M. Human C-Myc Onc Gene Is Located on the Region of Chromosome 8 That Is Translocated in Burkitt Lymphoma Cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1982, 79, 7824–7827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwab, M.; Ellison, J.; Busch, M.; Rosenau, W.; Varmus, H.E.; Bishop, J.M. Enhanced Expression of the Human Gene N-Myc Consequent to Amplification of DNA May Contribute to Malignant Progression of Neuroblastoma. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1984, 81, 4940–4944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shim, H.; Dolde, C.; Lewis, B.C.; Wu, C.S.; Dang, G.; Jungmann, R.A.; Dalla-Favera, R.; Dang, C.V. C-Myc Transactivation of LDH-A: Implications for Tumor Metabolism and Growth. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1997, 94, 6658–6663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elstrom, R.L.; Bauer, D.E.; Buzzai, M.; Karnauskas, R.; Harris, M.H.; Plas, D.R.; Zhuang, H.; Cinalli, R.M.; Alavi, A.; Rudin, C.M.; et al. Akt Stimulates Aerobic Glycolysis in Cancer Cells. Cancer Res. 2004, 64, 3892–3899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, A.J.; Puzio-Kuter, A.M. The Control of the Metabolic Switch in Cancers by Oncogenes and Tumor Suppressor Genes. Science 2010, 330, 1340–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartzenberg-Bar-Yoseph, F.; Armoni, M.; Karnieli, E. The Tumor Suppressor P53 Down-Regulates Glucose Transporters GLUT1 and GLUT4 Gene Expression. Cancer Res. 2004, 64, 2627–2633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying, H.; Kimmelman, A.C.; Lyssiotis, C.A.; Hua, S.; Chu, G.C.; Fletcher-Sananikone, E.; Locasale, J.W.; Son, J.; Zhang, H.; Coloff, J.L.; et al. Oncogenic Kras Maintains Pancreatic Tumors through Regulation of Anabolic Glucose Metabolism. Cell 2012, 149, 656–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baysal, B.E.; Ferrell, R.E.; Willett-Brozick, J.E.; Lawrence, E.C.; Myssiorek, D.; Bosch, A.; van der Mey, A.; Taschner, P.E.; Rubinstein, W.S.; Myers, E.N.; et al. Mutations in SDHD, a Mitochondrial Complex II Gene, in Hereditary Paraganglioma. Science 2000, 287, 848–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astuti, D.; Latif, F.; Dallol, A.; Dahia, P.L.; Douglas, F.; George, E.; Sköldberg, F.; Husebye, E.S.; Eng, C.; Maher, E.R. Gene Mutations in the Succinate Dehydrogenase Subunit SDHB Cause Susceptibility to Familial Pheochromocytoma and to Familial Paraganglioma. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2001, 69, 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomlinson, I.P.M.; Alam, N.A.; Rowan, A.J.; Barclay, E.; Jaeger, E.E.M.; Kelsell, D.; Leigh, I.; Gorman, P.; Lamlum, H.; Rahman, S.; et al. Germline Mutations in FH Predispose to Dominantly Inherited Uterine Fibroids, Skin Leiomyomata and Papillary Renal Cell Cancer. Nat. Genet. 2002, 30, 406–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottlieb, E.; Tomlinson, I.P.M. Mitochondrial Tumour Suppressors: A Genetic and Biochemical Update. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2005, 5, 857–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balss, J.; Meyer, J.; Mueller, W.; Korshunov, A.; Hartmann, C.; von Deimling, A. Analysis of the IDH1 Codon 132 Mutation in Brain Tumors. Acta Neuropathol. 2008, 116, 597–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, M.R.; Kim, M.S.; Oh, J.E.; Kim, Y.R.; Song, S.Y.; Seo, S.I.; Lee, J.Y.; Yoo, N.J.; Lee, S.H. Mutational Analysis of IDH1 Codon 132 in Glioblastomas and Other Common Cancers. Int. J. Cancer 2009, 125, 353–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsons, D.W.; Jones, S.; Zhang, X.; Lin, J.C.-H.; Leary, R.J.; Angenendt, P.; Mankoo, P.; Carter, H.; Siu, I.-M.; Gallia, G.L.; et al. An Integrated Genomic Analysis of Human Glioblastoma Multiforme. Science 2008, 321, 1807–1812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Missiroli, S.; Perrone, M.; Genovese, I.; Pinton, P.; Giorgi, C. Cancer Metabolism and Mitochondria: Finding Novel Mechanisms to Fight Tumours. EBioMedicine 2020, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lancaster, C.R.D. Succinate:Quinone Oxidoreductases: An Overview. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA) Bioenerg 2002, 1553, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Vranken, J.G.; Na, U.; Winge, D.R.; Rutter, J. Protein-Mediated Assembly of Succinate Dehydrogenase and Its Cofactors. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2015, 50, 168–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbara, P.; Stratakis, C.A. Sdh mutations in tumourigenesis and inherited endocrine tumours. J. Intern. Med. 2009, 266, 19–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dannenberg, H.; Speel, E.J.; Zhao, J.; Saremaslani, P.; van Der Harst, E.; Roth, J.; Heitz, P.U.; Bonjer, H.J.; Dinjens, W.N.; Mooi, W.J.; et al. Losses of Chromosomes 1p and 3q Are Early Genetic Events in the Development of Sporadic Pheochromocytomas. Am. J. Pathol. 2000, 157, 353–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Pollard, P.J.; Brière, J.J.; Alam, N.A.; Barwell, J.; Barclay, E.; Wortham, N.C.; Hunt, T.; Mitchell, M.; Olpin, S.; Moat, S.J.; et al. Accumulation of Krebs Cycle Intermediates and Over-Expression of HIF1alpha in Tumours Which Result from Germline FH and SDH Mutations. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2005, 14, 2231–2239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imperiale, A.; Moussallieh, F.-M.; Roche, P.; Battini, S.; Cicek, A.E.; Sebag, F.; Brunaud, L.; Barlier, A.; Elbayed, K.; Loundou, A.; et al. Metabolome Profiling by HRMAS NMR Spectroscopy of Pheochromocytomas and Paragangliomas Detects SDH Deficiency: Clinical and Pathophysiological Implications. Neoplasia 2015, 17, 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.; Wright, M.J.P.; Sioson, L.; Novos, T.; Gill, A.J.; Benn, D.E.; White, C.; Dwight, T.; Clifton-Bligh, R.J. Utility of the Succinate:Fumarate Ratio for Assessing SDH Dysfunction in Different Tumor Types. Mol. Genet. Metab. Rep. 2016, 10, 45–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lendvai, N.; Pawlosky, R.; Bullova, P.; Eisenhofer, G.; Patocs, A.; Veech, R.L.; Pacak, K. Succinate-to-Fumarate Ratio as a New Metabolic Marker to Detect the Presence of SDHB/D-Related Paraganglioma: Initial Experimental and Ex Vivo Findings. Endocrinology 2014, 155, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, S.; Gieldon, L.; Pang, Y.; Peitzsch, M.; Huynh, T.; Leton, R.; Viana, B.; Ercolino, T.; Mangelis, A.; Rapizzi, E.; et al. Metabolome-Guided Genomics to Identify Mutations in Isocitrate Dehydrogenase, Fumarate Hydratase and Succinate Dehydrogenase Genes in Pheochromocytoma and Paraganglioma. Genet. Med. 2019, 21, 705–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, S.; Peitzsch, M.; Rapizzi, E.; Lenders, J.W.; Qin, N.; de Cubas, A.A.; Schiavi, F.; Rao, J.U.; Beuschlein, F.; Quinkler, M.; et al. Krebs Cycle Metabolite Profiling for Identification and Stratification of Pheochromocytomas/Paragangliomas Due to Succinate Dehydrogenase Deficiency. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2014, 99, 3903–3911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghamir, S.M.K.; Heshmat, R.; Ebrahimi, M.; Ketabchi, S.E.; Dizaji, S.P.; Khatami, F. The Impact of Succinate Dehydrogenase Gene (SDH) Mutations in Renal Cell Carcinoma (RCC): A Systematic Review. OTT 2019, 12, 7929–7940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niemeijer, N.D.; Papathomas, T.G.; Korpershoek, E.; de Krijger, R.R.; Oudijk, L.; Morreau, H.; Bayley, J.-P.; Hes, F.J.; Jansen, J.C.; Dinjens, W.N.M.; et al. Succinate Dehydrogenase (SDH)-Deficient Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumor Expands the SDH-Related Tumor Spectrum. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2015, 100, E1386–E1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, S.-S.; Wang, Y.-F.; Bao, W.; Ye, S.-B.; Wu, N.; Wang, X.; Xia, Q.-Y.; Li, R.; Shen, Q.; Zhou, X.-J. Genetic and Epigenetic Alterations of SDH Genes in Patients with Sporadic Succinate Dehydrogenase-Deficient Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumors. Pathol. Int. 2019, 69, 350–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, S.R.; Eble, J.N.; Amin, M.B.; Gupta, N.S.; Smith, S.C.; Sholl, L.M.; Montironi, R.; Hirsch, M.S.; Hornick, J.L. Succinate Dehydrogenase-Deficient Renal Cell Carcinoma: Detailed Characterization of 11 Tumors Defining a Unique Subtype of Renal Cell Carcinoma. Mod. Pathol. 2015, 28, 80–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xekouki, P.; Szarek, E.; Bullova, P.; Giubellino, A.; Quezado, M.; Mastroyannis, S.A.; Mastorakos, P.; Wassif, C.A.; Raygada, M.; Rentia, N.; et al. Pituitary Adenoma with Paraganglioma/Pheochromocytoma (3PAs) and Succinate Dehydrogenase Defects in Humans and Mice. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2015, 100, E710–E719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Feng, F.; Guo, Q.-H.; Wang, Y.-P.; Zhao, R. Role of Succinate Dehydrogenase Deficiency and Oncometabolites in Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumors. World J. Gastroenterol. 2020, 26, 5074–5089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snezhkina, A.V.; Kalinin, D.V.; Pavlov, V.S.; Lukyanova, E.N.; Golovyuk, A.L.; Fedorova, M.S.; Pudova, E.A.; Savvateeva, M.V.; Stepanov, O.A.; Poloznikov, A.A.; et al. Immunohistochemistry and Mutation Analysis of SDHx Genes in Carotid Paragangliomas. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 6950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Nederveen, F.H.; Gaal, J.; Favier, J.; Korpershoek, E.; Oldenburg, R.A.; de Bruyn, E.M.C.A.; Sleddens, H.F.B.M.; Derkx, P.; Rivière, J.; Dannenberg, H.; et al. An Immunohistochemical Procedure to Detect Patients with Paraganglioma and Phaeochromocytoma with Germline SDHB, SDHC, or SDHD Gene Mutations: A Retrospective and Prospective Analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2009, 10, 764–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papathomas, T.G.; Oudijk, L.; Persu, A.; Gill, A.J.; van Nederveen, F.; Tischler, A.S.; Tissier, F.; Volante, M.; Matias-Guiu, X.; Smid, M.; et al. SDHB/SDHA Immunohistochemistry in Pheochromocytomas and Paragangliomas: A Multicenter Interobserver Variation Analysis Using Virtual Microscopy: A Multinational Study of the European Network for the Study of Adrenal Tumors (ENS@T). Mod. Pathol. 2015, 28, 807–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santi, R.; Rapizzi, E.; Canu, L.; Ercolino, T.; Baroni, G.; Fucci, R.; Costa, G.; Mannelli, M.; Nesi, G. Potential Pitfalls of SDH Immunohistochemical Detection in Paragangliomas and Phaeochromocytomas Harbouring Germline SDHx Gene Mutation. Anticancer Res. 2017, 37, 805–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casey, R.T.; McLean, M.A.; Madhu, B.; Challis, B.G.; Ten Hoopen, R.; Roberts, T.; Clark, G.R.; Pittfield, D.; Simpson, H.L.; Bulusu, V.R.; et al. Translating in Vivo Metabolomic Analysis of Succinate Dehydrogenase Deficient Tumours into Clinical Utility. JCO Precis Oncol. 2018, 2, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lussey-Lepoutre, C.; Bellucci, A.; Morin, A.; Buffet, A.; Amar, L.; Janin, M.; Ottolenghi, C.; Zinzindohoué, F.; Autret, G.; Burnichon, N.; et al. In Vivo Detection of Succinate by Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy as a Hallmark of SDHx Mutations in Paraganglioma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2016, 22, 1120–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzy, R.D.; Sharma, B.; Bell, E.; Chandel, N.S.; Schumacker, P.T. Loss of the SdhB, but Not the SdhA, Subunit of Complex II Triggers Reactive Oxygen Species-Dependent Hypoxia-Inducible Factor Activation and Tumorigenesis. Mol. Cell Biol. 2008, 28, 718–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yankovskaya, V.; Horsefield, R.; Törnroth, S.; Luna-Chavez, C.; Miyoshi, H.; Léger, C.; Byrne, B.; Cecchini, G.; Iwata, S. Architecture of Succinate Dehydrogenase and Reactive Oxygen Species Generation. Science 2003, 299, 700–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishii, T.; Yasuda, K.; Akatsuka, A.; Hino, O.; Hartman, P.S.; Ishii, N. A Mutation in the SDHC Gene of Complex II Increases Oxidative Stress, Resulting in Apoptosis and Tumorigenesis. Cancer Res. 2005, 65, 203–209. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Owens, K.M.; Aykin-Burns, N.; Dayal, D.; Coleman, M.C.; Domann, F.E.; Spitz, D.R. Genomic Instability Induced by Mutant Succinate Dehydrogenase Subunit D (SDHD) Is Mediated by O2(-•) and H2O2. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2012, 52, 160–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slane, B.G.; Aykin-Burns, N.; Smith, B.J.; Kalen, A.L.; Goswami, P.C.; Domann, F.E.; Spitz, D.R. Mutation of Succinate Dehydrogenase Subunit C Results in Increased O2.-, Oxidative Stress, and Genomic Instability. Cancer Res. 2006, 66, 7615–7620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flavahan, W.A.; Drier, Y.; Johnstone, S.E.; Hemming, M.L.; Tarjan, D.R.; Hegazi, E.; Shareef, S.J.; Javed, N.M.; Raut, C.P.; Eschle, B.K.; et al. Altered Chromosomal Topology Drives Oncogenic Programs in SDH-Deficient GISTs. Nature 2019, 575, 229–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyvekens, N.; Valtcheva, N.; Mischo, A.; Helmchen, B.; Hermanns, T.; Choschzick, M.; Hötker, A.M.; Rauch, A.; Mühleisen, B.; Akhoundova, D.; et al. Novel Morphological and Genetic Features of Fumarate Hydratase Deficient Renal Cell Carcinoma in HLRCC Syndrome Patients with a Tailored Therapeutic Approach. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 2020, 59, 611–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayley, J.-P.; Launonen, V.; Tomlinson, I.P. The FH Mutation Database: An Online Database of Fumarate Hydratase Mutations Involved in the MCUL (HLRCC) Tumor Syndrome and Congenital Fumarase Deficiency. BMC Med. Genet. 2008, 9, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Heras, A.B.; Castillejo, A.; García-Díaz, J.D.; Robledo, M.; Teulé, A.; Sánchez, R.; Zúñiga, Á.; Lastra, E.; Durán, M.; Llort, G.; et al. Hereditary Leiomyomatosis and Renal Cell Cancer Syndrome in Spain: Clinical and Genetic Characterization. Cancers 2020, 12, 3277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro-Vega, L.J.; Buffet, A.; De Cubas, A.A.; Cascón, A.; Menara, M.; Khalifa, E.; Amar, L.; Azriel, S.; Bourdeau, I.; Chabre, O.; et al. Germline Mutations in FH Confer Predisposition to Malignant Pheochromocytomas and Paragangliomas. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2014, 23, 2440–2446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, G.R.; Sciacovelli, M.; Gaude, E.; Walsh, D.M.; Kirby, G.; Simpson, M.A.; Trembath, R.C.; Berg, J.N.; Woodward, E.R.; Kinning, E.; et al. Germline FH Mutations Presenting with Pheochromocytoma. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2014, 99, E2046–E2050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, N.A.; Rowan, A.J.; Wortham, N.C.; Pollard, P.J.; Mitchell, M.; Tyrer, J.P.; Barclay, E.; Calonje, E.; Manek, S.; Adams, S.J.; et al. Genetic and Functional Analyses of FH Mutations in Multiple Cutaneous and Uterine Leiomyomatosis, Hereditary Leiomyomatosis and Renal Cancer, and Fumarate Hydratase Deficiency. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2003, 12, 1241–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toro, J.R.; Nickerson, M.L.; Wei, M.-H.; Warren, M.B.; Glenn, G.M.; Turner, M.L.; Stewart, L.; Duray, P.; Tourre, O.; Sharma, N.; et al. Mutations in the Fumarate Hydratase Gene Cause Hereditary Leiomyomatosis and Renal Cell Cancer in Families in North America. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2003, 73, 95–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picaud, S.; Kavanagh, K.L.; Yue, W.W.; Lee, W.H.; Muller-Knapp, S.; Gileadi, O.; Sacchettini, J.; Oppermann, U. Structural Basis of Fumarate Hydratase Deficiency. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2011, 34, 671–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estévez, M.; Skarda, J.; Spencer, J.; Banaszak, L.; Weaver, T.M. X-Ray Crystallographic and Kinetic Correlation of a Clinically Observed Human Fumarase Mutation. Protein Sci 2002, 11, 1552–1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casey, R.T.; McLean, M.A.; Challis, B.G.; McVeigh, T.P.; Warren, A.Y.; Mendil, L.; Houghton, R.; Sanctis, S.D.; Kosmoliaptsis, V.; Sandford, R.N.; et al. Fumarate Metabolic Signature for the Detection of Reed Syndrome in Humans. Clin. Cancer Res. 2020, 26, 391–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buelow, B.; Cohen, J.; Nagymanyoki, Z.; Frizzell, N.; Joseph, N.M.; McCalmont, T.; Garg, K. Immunohistochemistry for 2-Succinocysteine (2SC) and Fumarate Hydratase (FH) in Cutaneous Leiomyomas May Aid in Identification of Patients With HLRCC (Hereditary Leiomyomatosis and Renal Cell Carcinoma Syndrome). Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2016, 40, 982–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.-B.; Brannon, A.R.; Toubaji, A.; Dudas, M.E.; Won, H.H.; Al-Ahmadie, H.A.; Fine, S.W.; Gopalan, A.; Frizzell, N.; Voss, M.H.; et al. Hereditary Leiomyomatosis and Renal Cell Carcinoma Syndrome-Associated Renal Cancer: Recognition of the Syndrome by Pathologic Features and the Utility of Detecting Aberrant Succination by Immunohistochemistry. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2014, 38, 627–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joseph, N.M.; Solomon, D.A.; Frizzell, N.; Rabban, J.T.; Zaloudek, C.; Garg, K. Morphology and Immunohistochemistry for 2SC and FH Aid in Detection of Fumarate Hydratase Gene Aberrations in Uterine Leiomyomas from Young Patients. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2015, 39, 1529–1539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trpkov, K.; Hes, O.; Agaimy, A.; Bonert, M.; Martinek, P.; Magi-Galluzzi, C.; Kristiansen, G.; Lüders, C.; Nesi, G.; Compérat, E.; et al. Fumarate Hydratase-Deficient Renal Cell Carcinoma Is Strongly Correlated with Fumarate Hydratase Mutation and Hereditary Leiomyomatosis and Renal Cell Carcinoma Syndrome. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2016, 40, 865–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carter, C.S.; Skala, S.L.; Chinnaiyan, A.M.; McHugh, J.B.; Siddiqui, J.; Cao, X.; Dhanasekaran, S.M.; Fullen, D.R.; Lagstein, A.; Chan, M.P.; et al. Immunohistochemical Characterization of Fumarate Hydratase (FH) and Succinate Dehydrogenase (SDH) in Cutaneous Leiomyomas for Detection of Familial Cancer Syndromes. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2017, 41, 801–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinonen, H.-R.; Mehine, M.; Mäkinen, N.; Pasanen, A.; Pitkänen, E.; Karhu, A.; Sarvilinna, N.S.; Sjöberg, J.; Heikinheimo, O.; Bützow, R.; et al. Global Metabolomic Profiling of Uterine Leiomyomas. Br. J. Cancer 2017, 117, 1855–1864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.; MacKenzie, E.D.; Karim, S.A.; Hedley, A.; Blyth, K.; Kalna, G.; Watson, D.G.; Szlosarek, P.; Frezza, C.; Gottlieb, E. Reversed Argininosuccinate Lyase Activity in Fumarate Hydratase-Deficient Cancer Cells. Cancer Metab. 2013, 1, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borger, D.R.; Goyal, L.; Yau, T.; Poon, R.T.; Ancukiewicz, M.; Deshpande, V.; Christiani, D.C.; Liebman, H.M.; Yang, H.; Kim, H.; et al. Circulating Oncometabolite 2-Hydroxyglutarate Is a Potential Surrogate Biomarker in Patients with Isocitrate Dehydrogenase-Mutant Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2014, 20, 1884–1890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, L.; White, D.W.; Gross, S.; Bennett, B.D.; Bittinger, M.A.; Driggers, E.M.; Fantin, V.R.; Jang, H.G.; Jin, S.; Keenan, M.C.; et al. Cancer-Associated IDH1 Mutations Produce 2-Hydroxyglutarate. Nature 2009, 462, 739–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delahousse, J.; Verlingue, L.; Broutin, S.; Legoupil, C.; Touat, M.; Doucet, L.; Ammari, S.; Lacroix, L.; Ducreux, M.; Scoazec, J.-Y.; et al. Circulating Oncometabolite D-2-Hydroxyglutarate Enantiomer Is a Surrogate Marker of Isocitrate Dehydrogenase-Mutated Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinomas. Eur. J. Cancer 2018, 90, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombardi, G.; Corona, G.; Bellu, L.; Puppa, A.D.; Pambuku, A.; Fiduccia, P.; Bertorelle, R.; Gardiman, M.P.; D’Avella, D.; Toffoli, G.; et al. Diagnostic Value of Plasma and Urinary 2-Hydroxyglutarate to Identify Patients With Isocitrate Dehydrogenase-Mutated Glioma. Oncologist 2015, 20, 562–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natsumeda, M.; Igarashi, H.; Nomura, T.; Ogura, R.; Tsukamoto, Y.; Kobayashi, T.; Aoki, H.; Okamoto, K.; Kakita, A.; Takahashi, H.; et al. Accumulation of 2-Hydroxyglutarate in Gliomas Correlates with Survival: A Study by 3.0-Tesla Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2014, 2, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sim, H.-W.; Nejad, R.; Zhang, W.; Nassiri, F.; Mason, W.; Aldape, K.D.; Zadeh, G.; Chen, E.X. Tissue 2-Hydroxyglutarate as a Biomarker for Isocitrate Dehydrogenase Mutations in Gliomas. Clin. Cancer Res. 2019, 25, 3366–3373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winter, H.; Kaisaki, P.J.; Harvey, J.; Giacopuzzi, E.; Ferla, M.P.; Pentony, M.M.; Knight, S.J.L.; Sharma, R.A.; Taylor, J.C.; McCullagh, J.S.O. Identification of Circulating Genomic and Metabolic Biomarkers in Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma. Cancers 2019, 11, 1895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mardis, E.R.; Ding, L.; Dooling, D.J.; Larson, D.E.; McLellan, M.D.; Chen, K.; Koboldt, D.C.; Fulton, R.S.; Delehaunty, K.D.; McGrath, S.D.; et al. Recurring Mutations Found by Sequencing an Acute Myeloid Leukemia Genome. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009, 361, 1058–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borger, D.R.; Tanabe, K.K.; Fan, K.C.; Lopez, H.U.; Fantin, V.R.; Straley, K.S.; Schenkein, D.P.; Hezel, A.F.; Ancukiewicz, M.; Liebman, H.M.; et al. Frequent Mutation of Isocitrate Dehydrogenase (IDH)1 and IDH2 in Cholangiocarcinoma Identified through Broad-Based Tumor Genotyping. Oncologist 2012, 17, 72–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amary, M.F.; Bacsi, K.; Maggiani, F.; Damato, S.; Halai, D.; Berisha, F.; Pollock, R.; O’Donnell, P.; Grigoriadis, A.; Diss, T.; et al. IDH1 and IDH2 Mutations Are Frequent Events in Central Chondrosarcoma and Central and Periosteal Chondromas but Not in Other Mesenchymal Tumours. J. Pathol. 2011, 224, 334–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, S.; Weigelt, B.; Wen, H.-C.; Pareja, F.; Raghavendra, A.; Martelotto, L.G.; Burke, K.A.; Basili, T.; Li, A.; Geyer, F.C.; et al. IDH2 Mutations Define a Unique Subtype of Breast Cancer with Altered Nuclear Polarity. Cancer Res. 2016, 76, 7118–7129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fathi, A.T.; Sadrzadeh, H.; Comander, A.H.; Higgins, M.J.; Bardia, A.; Perry, A.; Burke, M.; Silver, R.; Matulis, C.R.; Straley, K.S.; et al. Isocitrate Dehydrogenase 1 (IDH1) Mutation in Breast Adenocarcinoma Is Associated with Elevated Levels of Serum and Urine 2-Hydroxyglutarate. Oncologist 2014, 19, 602–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minemura, H.; Takagi, K.; Sato, A.; Yamaguchi, M.; Hayashi, C.; Miki, Y.; Harada-Shoji, N.; Miyashita, M.; Sasano, H.; Suzuki, T. Isoforms of IDH in Breast Carcinoma: IDH2 as a Potent Prognostic Factor Associated with Proliferation in Estrogen-Receptor Positive Cases. Breast Cancer 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.; Parsons, D.W.; Jin, G.; McLendon, R.; Rasheed, B.A.; Yuan, W.; Kos, I.; Batinic-Haberle, I.; Jones, S.; Riggins, G.J.; et al. IDH1 and IDH2 Mutations in Gliomas. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009, 360, 765–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.-Y.; Tang, K.; Liang, T.-Y.; Zhang, W.-Z.; Li, J.-Y.; Wang, W.; Hu, H.-M.; Li, M.-Y.; Wang, H.-Q.; He, X.-Z.; et al. The Comparison of Clinical and Biological Characteristics between IDH1 and IDH2 Mutations in Gliomas. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2016, 35, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, Y.; Zhu, Y.-M.; Fan, X.; Shi, J.-Y.; Wang, Q.-R.; Yan, X.-J.; Gu, Z.-H.; Wang, Y.-Y.; Chen, B.; Jiang, C.-L.; et al. Gene Mutation Patterns and Their Prognostic Impact in a Cohort of 1185 Patients with Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Blood 2011, 118, 5593–5603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, C.; Ganji, S.K.; DeBerardinis, R.J.; Hatanpaa, K.J.; Rakheja, D.; Kovacs, Z.; Yang, X.-L.; Mashimo, T.; Raisanen, J.M.; Marin-Valencia, I.; et al. 2-Hydroxyglutarate Detection by Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy in IDH-Mutated Patients with Gliomas. Nat. Med. 2012, 18, 624–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gross, S.; Cairns, R.A.; Minden, M.D.; Driggers, E.M.; Bittinger, M.A.; Jang, H.G.; Sasaki, M.; Jin, S.; Schenkein, D.P.; Su, S.M.; et al. Cancer-Associated Metabolite 2-Hydroxyglutarate Accumulates in Acute Myelogenous Leukemia with Isocitrate Dehydrogenase 1 and 2 Mutations. J. Exp. Med. 2010, 207, 339–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, A.-P.; Abbas, S.; Kim, S.-W.; Ortega, M.; Bouamar, H.; Escobedo, Y.; Varadarajan, P.; Qin, Y.; Sudderth, J.; Schulz, E.; et al. D2HGDH Regulates Alpha-Ketoglutarate Levels and Dioxygenase Function by Modulating IDH2. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 7768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, G.; Reitman, Z.J.; Duncan, C.G.; Spasojevic, I.; Gooden, D.M.; Rasheed, B.A.; Yang, R.; Lopez, G.Y.; He, Y.; McLendon, R.E.; et al. Disruption of Wild Type IDH1 Suppresses D-2-Hydroxyglutarate Production in IDH1-Mutated Gliomas. Cancer Res. 2013, 73, 496–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louis, D.N.; Perry, A.; Reifenberger, G.; von Deimling, A.; Figarella-Branger, D.; Cavenee, W.K.; Ohgaki, H.; Wiestler, O.D.; Kleihues, P.; Ellison, D.W. The 2016 World Health Organization Classification of Tumors of the Central Nervous System: A Summary. Acta Neuropathol. 2016, 131, 803–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bleeker, F.E.; Atai, N.A.; Lamba, S.; Jonker, A.; Rijkeboer, D.; Bosch, K.S.; Tigchelaar, W.; Troost, D.; Vandertop, W.P.; Bardelli, A.; et al. The Prognostic IDH1(R132) Mutation Is Associated with Reduced NADP+-Dependent IDH Activity in Glioblastoma. Acta Neuropathol. 2010, 119, 487–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, C.; Hentschel, B.; Wick, W.; Capper, D.; Felsberg, J.; Simon, M.; Westphal, M.; Schackert, G.; Meyermann, R.; Pietsch, T.; et al. Patients with IDH1 Wild Type Anaplastic Astrocytomas Exhibit Worse Prognosis than IDH1-Mutated Glioblastomas, and IDH1 Mutation Status Accounts for the Unfavorable Prognostic Effect of Higher Age: Implications for Classification of Gliomas. Acta Neuropathol. 2010, 120, 707–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanson, M.; Marie, Y.; Paris, S.; Idbaih, A.; Laffaire, J.; Ducray, F.; El Hallani, S.; Boisselier, B.; Mokhtari, K.; Hoang-Xuan, K.; et al. Isocitrate Dehydrogenase 1 Codon 132 Mutation Is an Important Prognostic Biomarker in Gliomas. J. Clin. Oncol. 2009, 27, 4150–4154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Zheng, Z.; Guan, J.; Qi, D.; Zhou, S.; Shen, X.; Wang, F.; Wenkert, D.; Kirmani, B.; Solouki, T.; et al. Identification of a Panel of Genes as a Prognostic Biomarker for Glioblastoma. EBioMedicine 2018, 37, 68–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiNardo, C.D.; Propert, K.J.; Loren, A.W.; Paietta, E.; Sun, Z.; Levine, R.L.; Straley, K.S.; Yen, K.; Patel, J.P.; Agresta, S.; et al. Serum 2-Hydroxyglutarate Levels Predict Isocitrate Dehydrogenase Mutations and Clinical Outcome in Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Blood 2013, 121, 4917–4924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, A.; Tong, A.W.; Sweetman, L.; Theiss, A.; Murtaza, M.; Daoud, Y.; Wong, L. Characterization of Acute Myeloid Leukaemia (AML) Patients with Elevated Peripheral Blood Plasma D-2-Hydroxyglutarate (D-2HG) and/or Isocitrate Dehydrogenase (IDH) Mutational Status. Blood 2017, 130, 3923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balss, J.; Thiede, C.; Bochtler, T.; Okun, J.G.; Saadati, M.; Benner, A.; Pusch, S.; Ehninger, G.; Schaich, M.; Ho, A.D.; et al. Pretreatment d -2-Hydroxyglutarate Serum Levels Negatively Impact on Outcome in IDH1-Mutated Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Leukemia 2016, 30, 782–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunner, A.M.; Neuberg, D.S.; Wander, S.A.; Sadrzadeh, H.; Ballen, K.K.; Amrein, P.C.; Attar, E.; Hobbs, G.S.; Chen, Y.-B.; Perry, A.; et al. Isocitrate Dehydrogenase 1 and 2 Mutations, 2-Hydroxyglutarate Levels, and Response to Standard Chemotherapy for Patients with Newly Diagnosed Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Cancer 2019, 125, 541–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andronesi, O.C.; Kim, G.S.; Gerstner, E.; Batchelor, T.; Tzika, A.A.; Fantin, V.R.; Vander Heiden, M.G.; Sorensen, A.G. Detection of 2-Hydroxyglutarate in IDH-Mutated Glioma Patients by in Vivo Spectral-Editing and 2D Correlation Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy. Sci. Transl. Med. 2012, 4, 116ra4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branzoli, F.; Di Stefano, A.L.; Capelle, L.; Ottolenghi, C.; Valabrègue, R.; Deelchand, D.K.; Bielle, F.; Villa, C.; Baussart, B.; Lehéricy, S.; et al. Highly Specific Determination of IDH Status Using Edited in Vivo Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy. Neuro-oncology 2018, 20, 907–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, C.; Raisanen, J.M.; Ganji, S.K.; Zhang, S.; McNeil, S.S.; An, Z.; Madan, A.; Hatanpaa, K.J.; Vemireddy, V.; Sheppard, C.A.; et al. Prospective Longitudinal Analysis of 2-Hydroxyglutarate Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy Identifies Broad Clinical Utility for the Management of Patients With IDH-Mutant Glioma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2016, 34, 4030–4039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esmaeili, M.; Vettukattil, R.; Bathen, T.F. 2-Hydroxyglutarate as a Magnetic Resonance Biomarker for Glioma Subtyping. Transl. Oncol. 2013, 6, 92–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tietze, A.; Choi, C.; Mickey, B.; Maher, E.A.; Parm Ulhøi, B.; Sangill, R.; Lassen-Ramshad, Y.; Lukacova, S.; Østergaard, L.; von Oettingen, G.; et al. Noninvasive Assessment of Isocitrate Dehydrogenase Mutation Status in Cerebral Gliomas by Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy in a Clinical Setting. J. Neurosurg. 2018, 128, 391–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radoul, M.; Hong, D.; Gillespie, A.M.; Najac, C.; Viswanath, P.; Pieper, R.O.; Costello, J.F.; Luchman, H.A.; Ronen, S.M. Early Noninvasive Metabolic Biomarkers of Mutant IDH Inhibition in Glioma. Metabolites 2021, 11, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ballester, L.Y.; Lu, G.; Zorofchian, S.; Vantaku, V.; Putluri, V.; Yan, Y.; Arevalo, O.; Zhu, P.; Riascos, R.F.; Sreekumar, A.; et al. Analysis of Cerebrospinal Fluid Metabolites in Patients with Primary or Metastatic Central Nervous System Tumors. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2018, 6, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalinina, J.; Ahn, J.; Devi, N.S.; Wang, L.; Li, Y.; Olson, J.J.; Glantz, M.; Smith, T.; Kim, E.L.; Giese, A.; et al. Selective Detection of the D-Enantiomer of 2-Hydroxyglutarate in the CSF of Glioma Patients with Mutated Isocitrate Dehydrogenase. Clin. Cancer Res. 2016, 22, 6256–6265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuccarini, V.; Antelmi, L.; Pollo, B.; Paterra, R.; Calatozzolo, C.; Nigri, A.; DiMeco, F.; Eoli, M.; Finocchiaro, G.; Brenna, G.; et al. In Vivo 2-Hydroxyglutarate-Proton Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy (3 T, PRESS Technique) in Treatment-Naïve Suspect Lower-Grade Gliomas: Feasibility and Accuracy in a Clinical Setting. Neurol. Sci. 2020, 41, 347–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fathi, A.T.; Nahed, B.V.; Wander, S.A.; Iafrate, A.J.; Borger, D.R.; Hu, R.; Thabet, A.; Cahill, D.P.; Perry, A.M.; Joseph, C.P.; et al. Elevation of Urinary 2-Hydroxyglutarate in IDH-Mutant Glioma. Oncologist 2016, 21, 214–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belykh, E.; Shaffer, K.V.; Lin, C.; Byvaltsev, V.A.; Preul, M.C.; Chen, L. Blood-Brain Barrier, Blood-Brain Tumor Barrier, and Fluorescence-Guided Neurosurgical Oncology: Delivering Optical Labels to Brain Tumors. Front. Oncol. 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nduom, E.K.; Yang, C.; Merrill, M.J.; Zhuang, Z.; Lonser, R.R. Characterization of the Blood-Brain Barrier of Metastatic and Primary Malignant Neoplasms. J. Neurosurg. 2013, 119, 427–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engqvist, M.K.M.; Eßer, C.; Maier, A.; Lercher, M.J.; Maurino, V.G. Mitochondrial 2-Hydroxyglutarate Metabolism. Mitochondrion 2014, 19 Pt B, 275–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; Teng, X.; Liu, L.; Mattaini, K.R.; Looper, R.E.; VanderHeiden, M.G.; Rabinowitz, J.D. Human Phosphoglycerate Dehydrogenase Produces the Oncometabolite D-2-Hydroxyglutarate. ACS Chem. Biol. 2015, 10, 510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, P.; Tang, W.; Putluri, V.; Dorsey, T.H.; Jin, F.; Wang, F.; Zhu, D.; Amable, L.; Deng, T.; Zhang, S.; et al. ADHFE1 Is a Breast Cancer Oncogene and Induces Metabolic Reprogramming. J. Clin. Investig. 2018, 128, 323–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Struys, E.A.; Verhoeven, N.M.; Brunengraber, H.; Jakobs, C. Investigations by Mass Isotopomer Analysis of the Formation of D-2-Hydroxyglutarate by Cultured Lymphoblasts from Two Patients with D-2-Hydroxyglutaric Aciduria. FEBS Lett. 2004, 557, 115–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.; Stewart, K.M.; Wang, X.; Liu, K.; Xie, M.; Ryu, J.K.; Li, K.; Ma, T.; Wang, H.; Ni, L.; et al. Metabolic Control of TH17 and Induced Treg Cell Balance by an Epigenetic Mechanism. Nature 2017, 548, 228–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlova, N.N.; Thompson, C.B. The Emerging Hallmarks of Cancer Metabolism. Cell Metab. 2016, 23, 27–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colvin, H.; Nishida, N.; Konno, M.; Haraguchi, N.; Takahashi, H.; Nishimura, J.; Hata, T.; Kawamoto, K.; Asai, A.; Tsunekuni, K.; et al. Oncometabolite D-2-Hydroxyglurate Directly Induces Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition and Is Associated with Distant Metastasis in Colorectal Cancer. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 36289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoekstra, A.S.; de Graaff, M.A.; Briaire-de Bruijn, I.H.; Ras, C.; Seifar, R.M.; van Minderhout, I.; Cornelisse, C.J.; Hogendoorn, P.C.W.; Breuning, M.H.; Suijker, J.; et al. Inactivation of SDH and FH Cause Loss of 5hmC and Increased H3K9me3 in Paraganglioma/Pheochromocytoma and Smooth Muscle Tumors. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 38777–38788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, M.; Yang, H.; Xu, W.; Ma, S.; Lin, H.; Zhu, H.; Liu, L.; Liu, Y.; Yang, C.; Xu, Y.; et al. Inhibition of α-KG-Dependent Histone and DNA Demethylases by Fumarate and Succinate That Are Accumulated in Mutations of FH and SDH Tumor Suppressors. Genes Dev. 2012, 26, 1326–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Yang, H.; Liu, Y.; Yang, Y.; Wang, P.; Kim, S.-H.; Ito, S.; Yang, C.; Wang, P.; Xiao, M.-T.; et al. Oncometabolite 2-Hydroxyglutarate Is a Competitive Inhibitor of α-Ketoglutarate-Dependent Dioxygenases. Cancer Cell 2011, 19, 17–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, S.; Hausinger, R.P. Catalytic Mechanisms of Fe(II)- and 2-Oxoglutarate-Dependent Oxygenases. J. Biol. Chem. 2015, 290, 20702–20711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Hu, K.; Feng, J.; Wang, H.; Fu, S.; Wang, B.; Wang, L.; Xu, Y.; Yu, X.; Huang, H. The Oncometabolite R-2-Hydroxyglutarate Dysregulates the Differentiation of Human Mesenchymal Stromal Cells via Inducing DNA Hypermethylation. BMC Cancer 2021, 21, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scourzic, L.; Mouly, E.; Bernard, O.A. TET Proteins and the Control of Cytosine Demethylation in Cancer. Genome Med. 2015, 7, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsukada, Y.; Fang, J.; Erdjument-Bromage, H.; Warren, M.E.; Borchers, C.H.; Tempst, P.; Zhang, Y. Histone Demethylation by a Family of JmjC Domain-Containing Proteins. Nature 2006, 439, 811–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahiliani, M.; Koh, K.P.; Shen, Y.; Pastor, W.A.; Bandukwala, H.; Brudno, Y.; Agarwal, S.; Iyer, L.M.; Liu, D.R.; Aravind, L.; et al. Conversion of 5-Methylcytosine to 5-Hydroxymethylcytosine in Mammalian DNA by MLL Partner TET1. Science 2009, 324, 930–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarhonskaya, H.; Nowak, R.P.; Johansson, C.; Szykowska, A.; Tumber, A.; Hancock, R.L.; Lang, P.; Flashman, E.; Oppermann, U.; Schofield, C.J.; et al. Studies on the Interaction of the Histone Demethylase KDM5B with Tricarboxylic Acid Cycle Intermediates. J. Mol. Biol. 2017, 429, 2895–2906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malta, T.M.; de Souza, C.F.; Sabedot, T.S.; Silva, T.C.; Mosella, M.S.; Kalkanis, S.N.; Snyder, J.; Castro, A.V.B.; Noushmehr, H. Glioma CpG Island Methylator Phenotype (G-CIMP): Biological and Clinical Implications. Neuro Oncol. 2018, 20, 608–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Letouzé, E.; Martinelli, C.; Loriot, C.; Burnichon, N.; Abermil, N.; Ottolenghi, C.; Janin, M.; Menara, M.; Nguyen, A.T.; Benit, P.; et al. SDH Mutations Establish a Hypermethylator Phenotype in Paraganglioma. Cancer Cell 2013, 23, 739–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Illiano, M.; Conte, M.; Salzillo, A.; Ragone, A.; Spina, A.; Nebbioso, A.; Altucci, L.; Sapio, L.; Naviglio, S. The KDM Inhibitor GSKJ4 Triggers CREB Downregulation via a Protein Kinase A and Proteasome-Dependent Mechanism in Human Acute Myeloid Leukemia Cells. Front. Oncol. 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inoue, S.; Li, W.Y.; Tseng, A.; Beerman, I.; Elia, A.J.; Bendall, S.C.; Lemonnier, F.; Kron, K.J.; Cescon, D.W.; Hao, Z.; et al. Mutant IDH1 Downregulates ATM and Alters DNA Repair and Sensitivity to DNA Damage Independent of TET2. Cancer Cell 2016, 30, 337–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulkowski, P.L.; Oeck, S.; Dow, J.; Economos, N.G.; Mirfakhraie, L.; Liu, Y.; Noronha, K.; Bao, X.; Li, J.; Shuch, B.M.; et al. Oncometabolites Suppress DNA Repair by Disrupting Local Chromatin Signaling. Nature 2020, 582, 586–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batsios, G.; Viswanath, P.; Subramani, E.; Najac, C.; Gillespie, A.M.; Santos, R.D.; Molloy, A.R.; Pieper, R.O.; Ronen, S.M. PI3K/MTOR Inhibition of IDH1 Mutant Glioma Leads to Reduced 2HG Production That Is Associated with Increased Survival. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 10521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbonneau, M.; Gagné, L.M.; Lalonde, M.-E.; Germain, M.-A.; Motorina, A.; Guiot, M.-C.; Secco, B.; Vincent, E.E.; Tumber, A.; Hulea, L.; et al. The Oncometabolite 2-Hydroxyglutarate Activates the MTOR Signalling Pathway. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueroa, M.E.; Abdel-Wahab, O.; Lu, C.; Ward, P.S.; Patel, J.; Shih, A.; Li, Y.; Bhagwat, N.; Vasanthakumar, A.; Fernandez, H.F.; et al. Leukemic IDH1 and IDH2 Mutations Result in a Hypermethylation Phenotype, Disrupt TET2 Function, and Impair Hematopoietic Differentiation. Cancer Cell 2010, 18, 553–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaGory, E.L.; Giaccia, A.J. The Ever-Expanding Role of HIF in Tumour and Stromal Biology. Nat. Cell Biol. 2016, 18, 356–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semenza, G.L. Targeting HIF-1 for Cancer Therapy. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2003, 3, 721–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardo-Castiñeira, C.; Sáenz-de-Santa-María, I.; Valdés, N.; Astudillo, A.; Balbín, M.; Pitiot, A.S.; Jiménez-Fonseca, P.; Scola, B.; Tena, I.; Molina-Garrido, M.-J.; et al. Clinical Significance and Peculiarities of Succinate Dehydrogenase B and Hypoxia Inducible Factor 1α Expression in Parasympathetic versus Sympathetic Paragangliomas. Head Neck 2019, 41, 79–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaacs, J.S.; Jung, Y.J.; Mole, D.R.; Lee, S.; Torres-Cabala, C.; Chung, Y.-L.; Merino, M.; Trepel, J.; Zbar, B.; Toro, J.; et al. HIF Overexpression Correlates with Biallelic Loss of Fumarate Hydratase in Renal Cancer: Novel Role of Fumarate in Regulation of HIF Stability. Cancer Cell 2005, 8, 143–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selak, M.A.; Armour, S.M.; MacKenzie, E.D.; Boulahbel, H.; Watson, D.G.; Mansfield, K.D.; Pan, Y.; Simon, M.C.; Thompson, C.B.; Gottlieb, E. Succinate Links TCA Cycle Dysfunction to Oncogenesis by Inhibiting HIF-Alpha Prolyl Hydroxylase. Cancer Cell 2005, 7, 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yalaza, C.; Ak, H.; Cagli, M.S.; Ozgiray, E.; Atay, S.; Aydin, H.H. R132H Mutation in IDH1 Gene Is Associated with Increased Tumor HIF1-Alpha and Serum VEGF Levels in Primary Glioblastoma Multiforme. Ann. Clin. Lab. Sci. 2017, 47, 362–364. [Google Scholar]

- Laukka, T.; Mariani, C.J.; Ihantola, T.; Cao, J.Z.; Hokkanen, J.; Kaelin, W.G.; Godley, L.A.; Koivunen, P. Fumarate and Succinate Regulate Expression of Hypoxia-Inducible Genes via TET Enzymes. J. Biol. Chem. 2016, 291, 4256–4265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sourbier, C.; Ricketts, C.J.; Matsumoto, S.; Crooks, D.R.; Liao, P.-J.; Mannes, P.Z.; Yang, Y.; Wei, M.-H.; Srivastava, G.; Ghosh, S.; et al. Targeting ABL1-Mediated Oxidative Stress Adaptation in Fumarate Hydratase-Deficient Cancer. Cancer Cell 2014, 26, 840–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, X.; Zhao, T.; Xu, C.; Shi, W.; Geng, B.; Shen, J.; Zhang, C.; Pan, J.; Yang, J.; Hu, S.; et al. Oncometabolite Succinate Promotes Angiogenesis by Upregulating VEGF Expression through GPR91-Mediated STAT3 and ERK Activation. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 13174–13185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapieha, P.; Sirinyan, M.; Hamel, D.; Zaniolo, K.; Joyal, J.-S.; Cho, J.-H.; Honoré, J.-C.; Kermorvant-Duchemin, E.; Varma, D.R.; Tremblay, S.; et al. The Succinate Receptor GPR91 in Neurons Has a Major Role in Retinal Angiogenesis. Nat. Med. 2008, 14, 1067–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burr, S.P.; Costa, A.S.H.; Grice, G.L.; Timms, R.T.; Lobb, I.T.; Freisinger, P.; Dodd, R.B.; Dougan, G.; Lehner, P.J.; Frezza, C.; et al. Mitochondrial Protein Lipoylation and the 2-Oxoglutarate Dehydrogenase Complex Controls HIF1α Stability in Aerobic Conditions. Cell Metab. 2016, 24, 740–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koivunen, P.; Lee, S.; Duncan, C.G.; Lopez, G.; Lu, G.; Ramkissoon, S.; Losman, J.A.; Joensuu, P.; Bergmann, U.; Gross, S.; et al. Transformation by the (R)-Enantiomer of 2-Hydroxyglutarate Linked to EGLN Activation. Nature 2012, 483, 484–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koivunen, P.; Hirsilä, M.; Remes, A.M.; Hassinen, I.E.; Kivirikko, K.I.; Myllyharju, J. Inhibition of Hypoxia-Inducible Factor (HIF) Hydroxylases by Citric Acid Cycle Intermediates: Possible Links between Cell Metabolism and Stabilization of HIF. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 4524–4532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, S.; Lin, Y.; Xu, W.; Jiang, W.; Zha, Z.; Wang, P.; Yu, W.; Li, Z.; Gong, L.; Peng, Y.; et al. Glioma-Derived Mutations in IDH1 Dominantly Inhibit IDH1 Catalytic Activity and Induce HIF-1alpha. Science 2009, 324, 261–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metellus, P.; Colin, C.; Taieb, D.; Guedj, E.; Nanni-Metellus, I.; de Paula, A.M.; Colavolpe, C.; Fuentes, S.; Dufour, H.; Barrie, M.; et al. IDH Mutation Status Impact on in Vivo Hypoxia Biomarkers Expression: New Insights from a Clinical, Nuclear Imaging and Immunohistochemical Study in 33 Glioma Patients. J. Neurooncol. 2011, 105, 591–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, S.C.; Karajannis, M.A.; Chiriboga, L.; Golfinos, J.G.; von Deimling, A.; Zagzag, D. R132H-Mutation of Isocitrate Dehydrogenase-1 Is Not Sufficient for HIF-1α Upregulation in Adult Glioma. Acta Neuropathol. 2011, 121, 279–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alderson, N.L.; Wang, Y.; Blatnik, M.; Frizzell, N.; Walla, M.D.; Lyons, T.J.; Alt, N.; Carson, J.A.; Nagai, R.; Thorpe, S.R.; et al. S-(2-Succinyl)Cysteine: A Novel Chemical Modification of Tissue Proteins by a Krebs Cycle Intermediate. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2006, 450, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Z.; Zhang, S.; Chan, J.Y.; Zhang, D.D. Keap1 Controls Postinduction Repression of the Nrf2-Mediated Antioxidant Response by Escorting Nuclear Export of Nrf2. Mol. Cell Biol. 2007, 27, 6334–6349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzuki, T.; Muramatsu, A.; Saito, R.; Iso, T.; Shibata, T.; Kuwata, K.; Kawaguchi, S.-I.; Iwawaki, T.; Adachi, S.; Suda, H.; et al. Molecular Mechanism of Cellular Oxidative Stress Sensing by Keap1. Cell Rep. 2019, 28, 746–758.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kinch, L.; Grishin, N.V.; Brugarolas, J. Succination of Keap1 and Activation of Nrf2-Dependent Antioxidant Pathways in FH-Deficient Papillary Renal Cell Carcinoma Type 2. Cancer Cell 2011, 20, 418–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeNicola, G.M.; Karreth, F.A.; Humpton, T.J.; Gopinathan, A.; Wei, C.; Frese, K.; Mangal, D.; Yu, K.H.; Yeo, C.J.; Calhoun, E.S.; et al. Oncogene-Induced Nrf2 Transcription Promotes ROS Detoxification and Tumorigenesis. Nature 2011, 475, 106–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, M.; Kensler, T.W.; Motohashi, H. The KEAP1-NRF2 System: A Thiol-Based Sensor-Effector Apparatus for Maintaining Redox Homeostasis. Physiol. Rev. 2018, 98, 1169–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panieri, E.; Telkoparan-Akillilar, P.; Suzen, S.; Saso, L. The NRF2/KEAP1 Axis in the Regulation of Tumor Metabolism: Mechanisms and Therapeutic Perspectives. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, L.B.; Martinez-Garcia, E.; Nguyen, H.; Mullen, A.R.; Dufour, E.; Sudarshan, S.; Licht, J.D.; Deberardinis, R.J.; Chandel, N.S. The Proto-Oncometabolite Fumarate Binds Glutathione to Amplify ROS-Dependent Signaling. Mol. Cell 2013, 51, 236–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.; Cardaci, S.; Jerby, L.; MacKenzie, E.D.; Sciacovelli, M.; Johnson, T.I.; Gaude, E.; King, A.; Leach, J.D.G.; Edrada-Ebel, R.; et al. Fumarate Induces Redox-Dependent Senescence by Modifying Glutathione Metabolism. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 6001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudryavtseva, A.V.; Krasnov, G.S.; Dmitriev, A.A.; Alekseev, B.Y.; Kardymon, O.L.; Sadritdinova, A.F.; Fedorova, M.S.; Pokrovsky, A.V.; Melnikova, N.V.; Kaprin, A.D.; et al. Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Oxidative Stress in Aging and Cancer. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 44879–44905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smestad, J.; Erber, L.; Chen, Y.; Maher, L.J. Chromatin Succinylation Correlates with Active Gene Expression and Is Perturbed by Defective TCA Cycle Metabolism. iScience 2018, 2, 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Tan, M.; Xie, Z.; Dai, L.; Chen, Y.; Zhao, Y. Identification of Lysine Succinylation as a New Post-Translational Modification. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2011, 7, 58–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Shi, L.; Yang, S.; Yan, R.; Zhang, D.; Yang, J.; He, L.; Li, W.; Yi, X.; Sun, L.; et al. SIRT7 Is a Histone Desuccinylase That Functionally Links to Chromatin Compaction and Genome Stability. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 12235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Chen, Y.; Tishkoff, D.X.; Peng, C.; Tan, M.; Dai, L.; Xie, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Zwaans, B.M.M.; Skinner, M.E.; et al. SIRT5-Mediated Lysine Desuccinylation Impacts Diverse Metabolic Pathways. Mol. Cell 2013, 50, 919–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sreedhar, A.; Wiese, E.K.; Hitosugi, T. Enzymatic and Metabolic Regulation of Lysine Succinylation. Genes Dis. 2019, 7, 166–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Gibson, G.E. Succinylation Links Metabolism to Protein Functions. Neurochem. Res. 2019, 44, 2346–2359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.; Liu, Y.; Chen, L.; Zhang, M.; Li, W.; Cheng, H.; Zhang, B. Quantitative Proteome and Lysine Succinylome Analyses Provide Insights into Metabolic Regulation in Breast Cancer. Breast Cancer 2019, 26, 93–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, K.-Y.; Hsu, J.B.-K.; Lee, T.-Y. Characterization and Identification of Lysine Succinylation Sites Based on Deep Learning Method. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 16175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, F.; He, X.; Ye, D.; Lin, Y.; Yu, H.; Yao, C.; Huang, L.; Zhang, J.; Wang, F.; Xu, S.; et al. NADP+-IDH Mutations Promote Hypersuccinylation That Impairs Mitochondria Respiration and Induces Apoptosis Resistance. Mol. Cell 2015, 60, 661–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McBrayer, S.K.; Mayers, J.R.; DiNatale, G.J.; Shi, D.D.; Khanal, J.; Chakraborty, A.A.; Sarosiek, K.A.; Briggs, K.J.; Robbins, A.K.; Sewastianik, T.; et al. Transaminase Inhibition by 2-Hydroxyglutarate Impairs Glutamate Biosynthesis and Redox Homeostasis in Glioma. Cell 2018, 175, 101–116.e25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Nishimura, M.C.; Kharbanda, S.; Peale, F.; Deng, Y.; Daemen, A.; Forrest, W.F.; Kwong, M.; Hedehus, M.; Hatzivassiliou, G.; et al. Hominoid-Specific Enzyme GLUD2 Promotes Growth of IDH1R132H Glioma. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 14217–14222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Wu, J.; Ma, S.; Zhang, L.; Yao, J.; Hoadley, K.A.; Wilkerson, M.D.; Perou, C.M.; Guan, K.-L.; Ye, D.; et al. Oncometabolite D-2-Hydroxyglutarate Inhibits ALKBH DNA Repair Enzymes and Sensitizes IDH Mutant Cells to Alkylating Agents. Cell Rep. 2015, 13, 2353–2361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alimohammadi, E.; Bagheri, S.R.; Taheri, S.; Dayani, M.; Abdi, A. The Impact of Extended Adjuvant Temozolomide in Newly Diagnosed Glioblastoma Multiforme: A Meta-Analysis and Systematic Review. Oncol. Rev. 2020, 14, 461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emadi, A.; Jun, S.A.; Tsukamoto, T.; Fathi, A.T.; Minden, M.D.; Dang, C.V. Inhibition of Glutaminase Selectively Suppresses the Growth of Primary Acute Myeloid Leukemia Cells with IDH Mutations. Exp. Hematol. 2014, 42, 247–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohka, F.; Ito, M.; Ranjit, M.; Senga, T.; Motomura, A.; Motomura, K.; Saito, K.; Kato, K.; Kato, Y.; Wakabayashi, T.; et al. Quantitative Metabolome Analysis Profiles Activation of Glutaminolysis in Glioma with IDH1 Mutation. Tumour. Biol. 2014, 35, 5911–5920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matre, P.; Velez, J.; Jacamo, R.; Qi, Y.; Su, X.; Cai, T.; Chan, M.; Lodi, A.; Sweeney, S.; Ma, H.; et al. Inhibiting Glutaminase in Acute Myeloid Leukemia: Metabolic Dependency of Selected AML Subtypes. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 79722–79735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Rodado, V.; Lita, A.; Dowdy, T.; Celiku, O.; Saldana, A.C.; Wang, H.; Yang, C.Z.; Chari, R.; Li, A.; Zhang, W.; et al. Metabolic Plasticity of IDH1-Mutant Glioma Cell Lines Is Responsible for Low Sensitivity to Glutaminase Inhibition. Cancer Metab. 2020, 8, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tateishi, K.; Higuchi, F.; Miller, J.J.; Koerner, M.V.A.; Lelic, N.; Shankar, G.M.; Tanaka, S.; Fisher, D.E.; Batchelor, T.T.; Iafrate, A.J.; et al. The Alkylating Chemotherapeutic Temozolomide Induces Metabolic Stress in IDH1-Mutant Cancers and Potentiates NAD+ Depletion-Mediated Cytotoxicity. Cancer Res. 2017, 77, 4102–4115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SongTao, Q.; Lei, Y.; Si, G.; YanQing, D.; HuiXia, H.; XueLin, Z.; LanXiao, W.; Fei, Y. IDH Mutations Predict Longer Survival and Response to Temozolomide in Secondary Glioblastoma. Cancer Sci. 2012, 103, 269–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, P.; Zhang, W.; Wang, Y.; Peng, X.; Chen, B.; Qiu, X.; Li, G.; Li, S.; Wu, C.; Yao, K.; et al. IDH Mutation and MGMT Promoter Methylation in Glioblastoma: Results of a Prospective Registry. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 40896–40906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, G.-H.; Choi, S.Y.; Oh, T.-I.; Kan, S.-Y.; Kang, H.; Lee, S.; Oh, T.; Ko, H.M.; Lim, J.-H. IDH1R132H Causes Resistance to HDAC Inhibitors by Increasing NANOG in Glioblastoma Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 2679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohanbash, G.; Carrera, D.A.; Shrivastav, S.; Ahn, B.J.; Jahan, N.; Mazor, T.; Chheda, Z.S.; Downey, K.M.; Watchmaker, P.B.; Beppler, C.; et al. Isocitrate Dehydrogenase Mutations Suppress STAT1 and CD8+ T Cell Accumulation in Gliomas. J. Clin. Investig. 2017, 127, 1425–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amankulor, N.M.; Kim, Y.; Arora, S.; Kargl, J.; Szulzewsky, F.; Hanke, M.; Margineantu, D.H.; Rao, A.; Bolouri, H.; Delrow, J.; et al. Mutant IDH1 Regulates the Tumor-Associated Immune System in Gliomas. Genes Dev. 2017, 31, 774–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cejalvo, T.; Gargini, R.; Segura-Collar, B.; Mata-Martínez, P.; Herranz, B.; Cantero, D.; Ruano, Y.; García-Pérez, D.; Pérez-Núñez, Á.; Ramos, A.; et al. Immune Profiling of Gliomas Reveals a Connection with IDH1/2 Mutations, Tau Function and the Vascular Phenotype. Cancers 2020, 12, 3230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Böttcher, M.; Renner, K.; Berger, R.; Mentz, K.; Thomas, S.; Cardenas-Conejo, Z.E.; Dettmer, K.; Oefner, P.J.; Mackensen, A.; Kreutz, M.; et al. D-2-Hydroxyglutarate Interferes with HIF-1α Stability Skewing T-Cell Metabolism towards Oxidative Phosphorylation and Impairing Th17 Polarization. Oncoimmunology 2018, 7, e1445454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunse, L.; Pusch, S.; Bunse, T.; Sahm, F.; Sanghvi, K.; Friedrich, M.; Alansary, D.; Sonner, J.K.; Green, E.; Deumelandt, K.; et al. Suppression of Antitumor T Cell Immunity by the Oncometabolite (R)-2-Hydroxyglutarate. Nat. Med. 2018, 24, 1192–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Romero, P. Metabolic Control of CD8+ T Cell Fate Decisions and Antitumor Immunity. Trends Mol. Med. 2018, 24, 30–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Sorensen, M.D.; Kristensen, B.W.; Reifenberger, G.; McIntyre, T.M.; Lin, F. D-2-Hydroxyglutarate Is an Intercellular Mediator in IDH-Mutant Gliomas Inhibiting Complement and T Cells. Clin. Cancer Res. 2018, 24, 5381–5391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimolizzi, F.; Arranz, L. Multiple Faces of Succinate beyond Metabolism in Blood. Haematologica 2018, 103, 1586–1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, Y.S.; Levell, J.R.; Liu, G.; Caferro, T.; Sutton, J.; Shafer, C.M.; Costales, A.; Manning, J.R.; Zhao, Q.; Sendzik, M.; et al. Discovery and Evaluation of Clinical Candidate IDH305, a Brain Penetrant Mutant IDH1 Inhibitor. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2017, 8, 1116–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, R.; Yun, C.-H. Crystal Structures of Pan-IDH Inhibitor AG-881 in Complex with Mutant Human IDH1 and IDH2. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2018, 503, 2912–2917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norsworthy, K.J.; Luo, L.; Hsu, V.; Gudi, R.; Dorff, S.E.; Przepiorka, D.; Deisseroth, A.; Shen, Y.-L.; Sheth, C.M.; Charlab, R.; et al. FDA Approval Summary: Ivosidenib for Relapsed or Refractory Acute Myeloid Leukemia with an Isocitrate Dehydrogenase-1 Mutation. Clin. Cancer Res. 2019, 25, 3205–3209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stein, E.M.; DiNardo, C.D.; Pollyea, D.A.; Fathi, A.T.; Roboz, G.J.; Altman, J.K.; Stone, R.M.; DeAngelo, D.J.; Levine, R.L.; Flinn, I.W.; et al. Enasidenib in Mutant IDH2 Relapsed or Refractory Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Blood 2017, 130, 722–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watts, J.M.; Baer, M.R.; Yang, J.; Prebet, T.; Lee, S.; Schiller, G.J.; Dinner, S.; Pigneux, A.; Montesinos, P.; Wang, E.S.; et al. Olutasidenib (FT-2102), an IDH1m Inhibitor as a Single Agent or in Combination with Azacitidine, Induces Deep Clinical Responses with Mutation Clearance in Patients with Acute Myeloid Leukemia Treated in a Phase 1 Dose Escalation and Expansion Study. Blood 2019, 134, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, L.; Su, S.-S.M. Isocitrate Dehydrogenase Mutation and (R)-2-Hydroxyglutarate: From Basic Discovery to Therapeutics Development. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2017, 86, 305–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IDHIFA® (Enasidenib) Tablets, for Oral Use Initial U.S. Approval: 2017. Available online: https://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/fda/fdaDrugXsl.cfm?setid=a5b4cdf0-3fa8-4c6c-80f6-8d8a00e3a5b6&type=display (accessed on 12 May 2021).

- DiNardo, C.D.; Schuh, A.C.; Stein, E.M.; Fernandez, P.M.; Wei, A.; De Botton, S.; Zeidan, A.M.; Fathi, A.T.; Quek, L.; Kantarjian, H.M.; et al. Enasidenib Plus Azacitidine Significantly Improves Complete Remission and Overall Response Compared with Azacitidine Alone in Patients with Newly Diagnosed Acute Myeloid Leukemia (AML) with Isocitrate Dehydrogenase 2 (IDH2) Mutations: Interim Phase II Results from an Ongoing, Randomized Study. Blood 2019, 134, 643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiNardo, C.D.; Stein, E.M.; de Botton, S.; Roboz, G.J.; Altman, J.K.; Mims, A.S.; Swords, R.; Collins, R.H.; Mannis, G.N.; Pollyea, D.A.; et al. Durable Remissions with Ivosidenib in IDH1-Mutated Relapsed or Refractory AML. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 378, 2386–2398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TIBSOVO® (Ivosidenib Tablets). Available online: https://www.tibsovo.com/treatment/#possible-side-effects (accessed on 13 May 2021).

- Research, C. for D.E. and FDA Approves Ivosidenib as First-Line Treatment for AML with IDH1 Mutation. FDA 2019. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/drugs/resources-information-approved-drugs/fda-approves-ivosidenib-first-line-treatment-aml-idh1-mutation (accessed on 12 March 2021).

- Abou-Alfa, G.K.; Macarulla, T.; Javle, M.M.; Kelley, R.K.; Lubner, S.J.; Adeva, J.; Cleary, J.M.; Catenacci, D.V.; Borad, M.J.; Bridgewater, J.; et al. Ivosidenib in IDH1-Mutant, Chemotherapy-Refractory Cholangiocarcinoma (ClarIDHy): A Multicentre, Randomised, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Phase 3 Study. Lancet Oncol. 2020, 21, 796–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Intlekofer, A.M.; Shih, A.H.; Wang, B.; Nazir, A.; Rustenburg, A.S.; Albanese, S.K.; Patel, M.; Famulare, C.; Correa, F.M.; Takemoto, N.; et al. Acquired Resistance to IDH Inhibition through Trans or Cis Dimer-Interface Mutations. Nature 2018, 559, 125–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oltvai, Z.N.; Harley, S.E.; Koes, D.; Michel, S.; Warlick, E.D.; Nelson, A.C.; Yohe, S.; Mroz, P. Assessing Acquired Resistance to IDH1 Inhibitor Therapy by Full-Exon IDH1 Sequencing and Structural Modeling. Cold Spring Harb. Mol. Case Stud. 2021, 7, a006007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harding, J.J.; Lowery, M.A.; Shih, A.H.; Schvartzman, J.M.; Hou, S.; Famulare, C.; Patel, M.; Roshal, M.; Do, R.K.; Zehir, A.; et al. Isoform Switching as a Mechanism of Acquired Resistance to Mutant Isocitrate Dehydrogenase Inhibition. Cancer Discov. 2018, 8, 1540–1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, J.; Hohmann, T.; Güttler, A.; Petrenko, M.; Ostheimer, C.; Hohmann, U.; Bache, M.; Dehghani, F.; Vordermark, D. Radiosensitization and a Less Aggressive Phenotype of Human Malignant Glioma Cells Expressing Isocitrate Dehydrogenase 1 (IDH1) Mutant Protein: Dissecting the Mechanisms. Cancers 2019, 11, 889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Ouyang, L.; He, M.; Luo, M.; Cai, W.; Tu, Y.; Pi, R.; Liu, A. IDH1 R132H Mutation Regulates Glioma Chemosensitivity through Nrf2 Pathway. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 28865–28879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.; Cai, J.; Tan, Z.; Meng, X.; Li, R.; Li, Y.; Jiang, C. Mutant IDH1 Enhances Temozolomide Sensitivity via Regulation of the ATM/CHK2 Pathway in Glioma. Cancer Res. Treat. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Sun, B.; Shi, W.; Zuo, H.; Cui, D.; Ni, L.; Chen, J. Decreasing GSH and Increasing ROS in Chemosensitivity Gliomas with IDH1 Mutation. Tumour. Biol. 2015, 36, 655–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, D.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Ruiz-Rodado, V.; Larion, M.; Xu, G.; Yang, C. Triptolide Suppresses IDH1-Mutated Malignancy via Nrf2-Driven Glutathione Metabolism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 9964–9972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cairncross, J.G.; Wang, M.; Jenkins, R.B.; Shaw, E.G.; Giannini, C.; Brachman, D.G.; Buckner, J.C.; Fink, K.L.; Souhami, L.; Laperriere, N.J.; et al. Benefit from Procarbazine, Lomustine, and Vincristine in Oligodendroglial Tumors Is Associated with Mutation of IDH. J. Clin. Oncol. 2014, 32, 783–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohrenz, I.V.; Antonietti, P.; Pusch, S.; Capper, D.; Balss, J.; Voigt, S.; Weissert, S.; Mukrowsky, A.; Frank, J.; Senft, C.; et al. Isocitrate Dehydrogenase 1 Mutant R132H Sensitizes Glioma Cells to BCNU-Induced Oxidative Stress and Cell Death. Apoptosis 2013, 18, 1416–1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molenaar, R.J.; Botman, D.; Smits, M.A.; Hira, V.V.; van Lith, S.A.; Stap, J.; Henneman, P.; Khurshed, M.; Lenting, K.; Mul, A.N.; et al. Radioprotection of IDH1-Mutated Cancer Cells by the IDH1-Mutant Inhibitor AGI-5198. Cancer Res. 2015, 75, 4790–4802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tran, A.N.; Lai, A.; Li, S.; Pope, W.B.; Teixeira, S.; Harris, R.J.; Woodworth, D.C.; Nghiemphu, P.L.; Cloughesy, T.F.; Ellingson, B.M. Increased Sensitivity to Radiochemotherapy in IDH1 Mutant Glioblastoma as Demonstrated by Serial Quantitative MR Volumetry. Neuro Oncol. 2014, 16, 414–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Platten, M.; Schilling, D.; Bunse, L.; Wick, A.; Bunse, T.; Riehl, D.; Karapanagiotou-Schenkel, I.; Harting, I.; Sahm, F.; Schmitt, A.; et al. A Mutation-Specific Peptide Vaccine Targeting IDH1R132H in Patients with Newly Diagnosed Malignant Astrocytomas: A First-in-Man Multicenter Phase I Clinical Trial of the German Neurooncology Working Group (NOA-16). JCO 2018, 36, 2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumacher, T.; Bunse, L.; Pusch, S.; Sahm, F.; Wiestler, B.; Quandt, J.; Menn, O.; Osswald, M.; Oezen, I.; Ott, M.; et al. A Vaccine Targeting Mutant IDH1 Induces Antitumour Immunity. Nature 2014, 512, 324–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilf, N.; Kuttruff-Coqui, S.; Frenzel, K.; Bukur, V.; Stevanović, S.; Gouttefangeas, C.; Platten, M.; Tabatabai, G.; Dutoit, V.; van der Burg, S.H.; et al. Actively Personalized Vaccination Trial for Newly Diagnosed Glioblastoma. Nature 2019, 565, 240–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollack, I.F.; Jakacki, R.I.; Butterfield, L.H.; Hamilton, R.L.; Panigrahy, A.; Normolle, D.P.; Connelly, A.K.; Dibridge, S.; Mason, G.; Whiteside, T.L.; et al. Antigen-Specific Immunoreactivity and Clinical Outcome Following Vaccination with Glioma-Associated Antigen Peptides in Children with Recurrent High-Grade Gliomas: Results of a Pilot Study. J. Neurooncol. 2016, 130, 517–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platten, M.; Bunse, L.; Wick, A.; Bunse, T.; Le Cornet, L.; Harting, I.; Sahm, F.; Sanghvi, K.; Tan, C.L.; Poschke, I.; et al. A Vaccine Targeting Mutant IDH1 in Newly Diagnosed Glioma. Nature 2021, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calithera Biosciences, Inc. Ph1 Study of the Safety, PK, and PDn of Escalating Oral Doses of the Glutaminase Inhibitor CB-839, as a Single Agent and in Combination with Standard Chemotherapy in Patients With Advanced and/or Treatment-Refractory Solid Tumors. 2020. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02071862 (accessed on 12 March 2021).

- Kitazawa, S.; Ebara, S.; Ando, A.; Baba, Y.; Satomi, Y.; Soga, T.; Hara, T. Succinate Dehydrogenase B-Deficient Cancer Cells Are Highly Sensitive to Bromodomain and Extra-Terminal Inhibitors. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 28922–28938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkadi, B.; Meszaros, K.; Krencz, I.; Canu, L.; Krokker, L.; Zakarias, S.; Barna, G.; Sebestyen, A.; Papay, J.; Hujber, Z.; et al. Glutaminases as a Novel Target for SDHB-Associated Pheochromocytomas/Paragangliomas. Cancers 2020, 12, 599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salamanca-Cardona, L.; Shah, H.; Poot, A.J.; Correa, F.M.; Di Gialleonardo, V.; Lui, H.; Miloushev, V.Z.; Granlund, K.L.; Tee, S.S.; Cross, J.R.; et al. In Vivo Imaging of Glutamine Metabolism to the Oncometabolite 2-Hydroxyglutarate in IDH1/2 Mutant Tumors. Cell Metab. 2017, 26, 830–841.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terunuma, A.; Putluri, N.; Mishra, P.; Mathé, E.A.; Dorsey, T.H.; Yi, M.; Wallace, T.A.; Issaq, H.J.; Zhou, M.; Killian, J.K.; et al. MYC-Driven Accumulation of 2-Hydroxyglutarate Is Associated with Breast Cancer Prognosis. J. Clin. Investig. 2014, 124, 398–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamashita, A.S.; da Costa Rosa, M.; Stumpo, V.; Rais, R.; Slusher, B.S.; Riggins, G.J. The Glutamine Antagonist Prodrug JHU-083 Slows Malignant Glioma Growth and Disrupts MTOR Signaling. Neurooncol. Adv. 2021, 3, vdaa149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKenzie, E.D.; Selak, M.A.; Tennant, D.A.; Payne, L.J.; Crosby, S.; Frederiksen, C.M.; Watson, D.G.; Gottlieb, E. Cell-Permeating α-Ketoglutarate Derivatives Alleviate Pseudohypoxia in Succinate Dehydrogenase-Deficient Cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2007, 27, 3282–3289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loriot, C.; Domingues, M.; Berger, A.; Menara, M.; Ruel, M.; Morin, A.; Castro-Vega, L.-J.; Letouzé, É.; Martinelli, C.; Bemelmans, A.-P.; et al. Deciphering the Molecular Basis of Invasiveness in Sdhb-Deficient Cells. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 32955–32965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borodovsky, A.; Salmasi, V.; Turcan, S.; Fabius, A.W.M.; Baia, G.S.; Eberhart, C.G.; Weingart, J.D.; Gallia, G.L.; Baylin, S.B.; Chan, T.A.; et al. 5-Azacytidine Reduces Methylation, Promotes Differentiation and Induces Tumor Regression in a Patient-Derived IDH1 Mutant Glioma Xenograft. Oncotarget 2013, 4, 1737–1747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Federici, L.; Capelle, L.; Annereau, M.; Bielle, F.; Willekens, C.; Dehais, C.; Laigle-Donadey, F.; Hoang-Xuan, K.; Delattre, J.-Y.; Idbaih, A.; et al. 5-Azacitidine in Patients with IDH1/2-Mutant Recurrent Glioma. Neuro Oncol. 2020, 22, 1226–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turcan, S.; Fabius, A.W.M.; Borodovsky, A.; Pedraza, A.; Brennan, C.; Huse, J.; Viale, A.; Riggins, G.J.; Chan, T.A. Efficient Induction of Differentiation and Growth Inhibition in IDH1 Mutant Glioma Cells by the DNMT Inhibitor Decitabine. Oncotarget 2013, 4, 1729–1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamashita, A.S.; da Costa Rosa, M.; Borodovsky, A.; Festuccia, W.T.; Chan, T.; Riggins, G.J. Demethylation and Epigenetic Modification with 5-Azacytidine Reduces IDH1 Mutant Glioma Growth in Combination with Temozolomide. Neuro Oncol. 2019, 21, 189–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DiNardo, C.D.; Pratz, K.; Pullarkat, V.; Jonas, B.A.; Arellano, M.; Becker, P.S.; Frankfurt, O.; Konopleva, M.; Wei, A.H.; Kantarjian, H.M.; et al. Venetoclax Combined with Decitabine or Azacitidine in Treatment-Naive, Elderly Patients with Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Blood 2019, 133, 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pollyea, D.A.; Stevens, B.M.; Jones, C.L.; Winters, A.; Pei, S.; Minhajuddin, M.; D’Alessandro, A.; Culp-Hill, R.; Riemondy, K.A.; Gillen, A.E.; et al. Venetoclax with Azacitidine Disrupts Energy Metabolism and Targets Leukemia Stem Cells in Patients with Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Nat. Med. 2018, 24, 1859–1866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaturvedi, A.; Gupta, C.; Goparaju, R.; Gabdoulline, R.; Kaulfuss, S.; Görlich, K.; Schottmann, R.; Panknin, O.; Wagner, M.; Geffers, R.; et al. Synergistic Activity of IDH1 Inhibitor Bay-1436032 with Azacitidine in IDH1 Mutant Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Blood 2017, 130, 1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yen, K.; Travins, J.; Wang, F.; David, M.D.; Artin, E.; Straley, K.; Padyana, A.; Gross, S.; DeLaBarre, B.; Tobin, E.; et al. AG-221, a First-in-Class Therapy Targeting Acute Myeloid Leukemia Harboring Oncogenic IDH2 Mutations. Cancer Discov. 2017, 7, 478–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, G.; Shen, J.; Yin, M.; McManus, J.; Mathieu, M.; Gee, P.; He, T.; Shi, C.; Bedel, O.; McLean, L.R.; et al. Selective Inhibition of Mutant Isocitrate Dehydrogenase 1 (IDH1) via Disruption of a Metal Binding Network by an Allosteric Small Molecule. J. Biol. Chem. 2015, 290, 762–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaturvedi, A.; Herbst, L.; Pusch, S.; Klett, L.; Goparaju, R.; Stichel, D.; Kaulfuss, S.; Panknin, O.; Zimmermann, K.; Toschi, L.; et al. Pan-Mutant-IDH1 Inhibitor BAY1436032 Is Highly Effective against Human IDH1 Mutant Acute Myeloid Leukemia in Vivo. Leukemia 2017, 31, 2020–2028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heuser, M.; Palmisiano, N.; Mantzaris, I.; Mims, A.; DiNardo, C.; Silverman, L.R.; Wang, E.S.; Fiedler, W.; Baldus, C.; Schwind, S.; et al. Safety and Efficacy of BAY1436032 in IDH1-Mutant AML: Phase I Study Results. Leukemia 2020, 34, 2903–2913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pusch, S.; Krausert, S.; Fischer, V.; Balss, J.; Ott, M.; Schrimpf, D.; Capper, D.; Sahm, F.; Eisel, J.; Beck, A.-C.; et al. Pan-Mutant IDH1 Inhibitor BAY 1436032 for Effective Treatment of IDH1 Mutant Astrocytoma in Vivo. Acta Neuropathol. 2017, 133, 629–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Paz, A.C.; Wilky, B.A.; Johnson, B.; Galoian, K.; Rosenberg, A.; Hu, G.; Tinoco, G.; Bodamer, O.; Trent, J.C. Treatment with a Small Molecule Mutant IDH1 Inhibitor Suppresses Tumorigenic Activity and Decreases Production of the Oncometabolite 2-Hydroxyglutarate in Human Chondrosarcoma Cells. PLoS ONE 2015, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohle, D.; Popovici-Muller, J.; Palaskas, N.; Turcan, S.; Grommes, C.; Campos, C.; Tsoi, J.; Clark, O.; Oldrini, B.; Komisopoulou, E.; et al. An Inhibitor of Mutant IDH1 Delays Growth and Promotes Differentiation of Glioma Cells. Science 2013, 340, 626–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urban, D.J.; Martinez, N.J.; Davis, M.I.; Brimacombe, K.R.; Cheff, D.M.; Lee, T.D.; Henderson, M.J.; Titus, S.A.; Pragani, R.; Rohde, J.M.; et al. Assessing Inhibitors of Mutant Isocitrate Dehydrogenase Using a Suite of Pre-Clinical Discovery Assays. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 12758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Travins, J.; DeLaBarre, B.; Penard-Lacronique, V.; Schalm, S.; Hansen, E.; Straley, K.; Kernytsky, A.; Liu, W.; Gliser, C.; et al. Targeted Inhibition of Mutant IDH2 in Leukemia Cells Induces Cellular Differentiation. Science 2013, 340, 622–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okoye-Okafor, U.C.; Bartholdy, B.; Cartier, J.; Gao, E.N.; Pietrak, B.; Rendina, A.R.; Rominger, C.; Quinn, C.; Smallwood, A.; Wiggall, K.J.; et al. New IDH1 Mutant Inhibitors for Treatment of Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2015, 11, 878–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

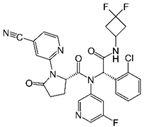

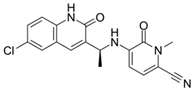

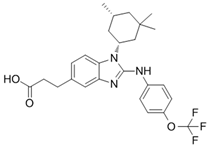

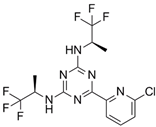

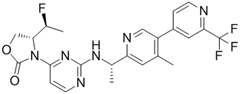

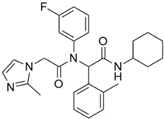

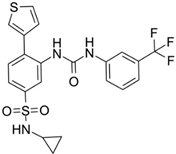

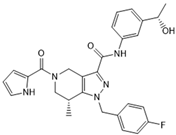

| Drug | Phase | Target | Mechanism of Action | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enasidenib (AG-221)  | FDA approval | IDH2 | Reversible, allosteric non-competitive inhibition via stabilization of the mutated IDH non-catalytic open conformation that prevents R-2HG formation [242]. | [201] |

| Ivosidenib (AG-120)  | FDA approval | IDH1 | Reversible, allosteric inhibition of IDH1 R132 mutants competing with the cofactor Mg ion and preventing the formation of the catalytically active protein conformation [243] | [200] |

| Olutasidenib (FT-2102)  | I/II | IDH1 | Competitive inhibition at isocitrate-binding pocket blocking the conformational changes necessary for the catalysis. | [202] |

BAY-1436032 | I | IDH1 | Non-competitive, allosteric inhibition by binding at the interface of two monomers and stabilization of open inactive conformation. | [244,245,246] |

Vorasidenib (AG-881) | III | IDH1/2 | Non-competitive, allosteric inhibition by binding at the interface of two monomers and stabilization of open inactive conformation. | [199] |

IDH-305 | I | IDH1 | Allosteric, non-competitive inhibition via stabilization of open, inactive enzyme dimer conformation (steric hindrance). | [198] |

AGI-5198 | Pre-clinical | IDH1 | Allosteric, competitive inhibition of α-KG. | [247,248] |

AGI-6780 | Pre-clinical | IDH2 | Allosteric inhibition by binding at the monomers interface preventing the transition for the active enzyme conformation. | [249,250] |

GSK321 | Pre-clinical | IDH1 | Allosteric inhibition by blocking the enzyme in the inactive conformation. | [251] |

| PEPIDH1M vaccine | I | IDH1 | T-helper-1 (TH1) responses are activated by presentation to major histocompatibility complexes (MHC) class II of the peptide encompassing the immunogenic epitope of the mutated IDH region. | [223] |

| IDH1 peptide vaccine | I | IDH1 | IDH1(R132H)-specific peptide vaccine enhances T helper cell responses against tumours in synergism with the mutated IDH immunogenic epitope. | [222,226] |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Di Gregorio, E.; Miolo, G.; Saorin, A.; Steffan, A.; Corona, G. From Metabolism to Genetics and Vice Versa: The Rising Role of Oncometabolites in Cancer Development and Therapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 5574. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22115574

Di Gregorio E, Miolo G, Saorin A, Steffan A, Corona G. From Metabolism to Genetics and Vice Versa: The Rising Role of Oncometabolites in Cancer Development and Therapy. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2021; 22(11):5574. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22115574

Chicago/Turabian StyleDi Gregorio, Emanuela, Gianmaria Miolo, Asia Saorin, Agostino Steffan, and Giuseppe Corona. 2021. "From Metabolism to Genetics and Vice Versa: The Rising Role of Oncometabolites in Cancer Development and Therapy" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 22, no. 11: 5574. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22115574

APA StyleDi Gregorio, E., Miolo, G., Saorin, A., Steffan, A., & Corona, G. (2021). From Metabolism to Genetics and Vice Versa: The Rising Role of Oncometabolites in Cancer Development and Therapy. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 22(11), 5574. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22115574