The Role of Estradiol in Traumatic Brain Injury: Mechanism and Treatment Potential

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. TBI Classification

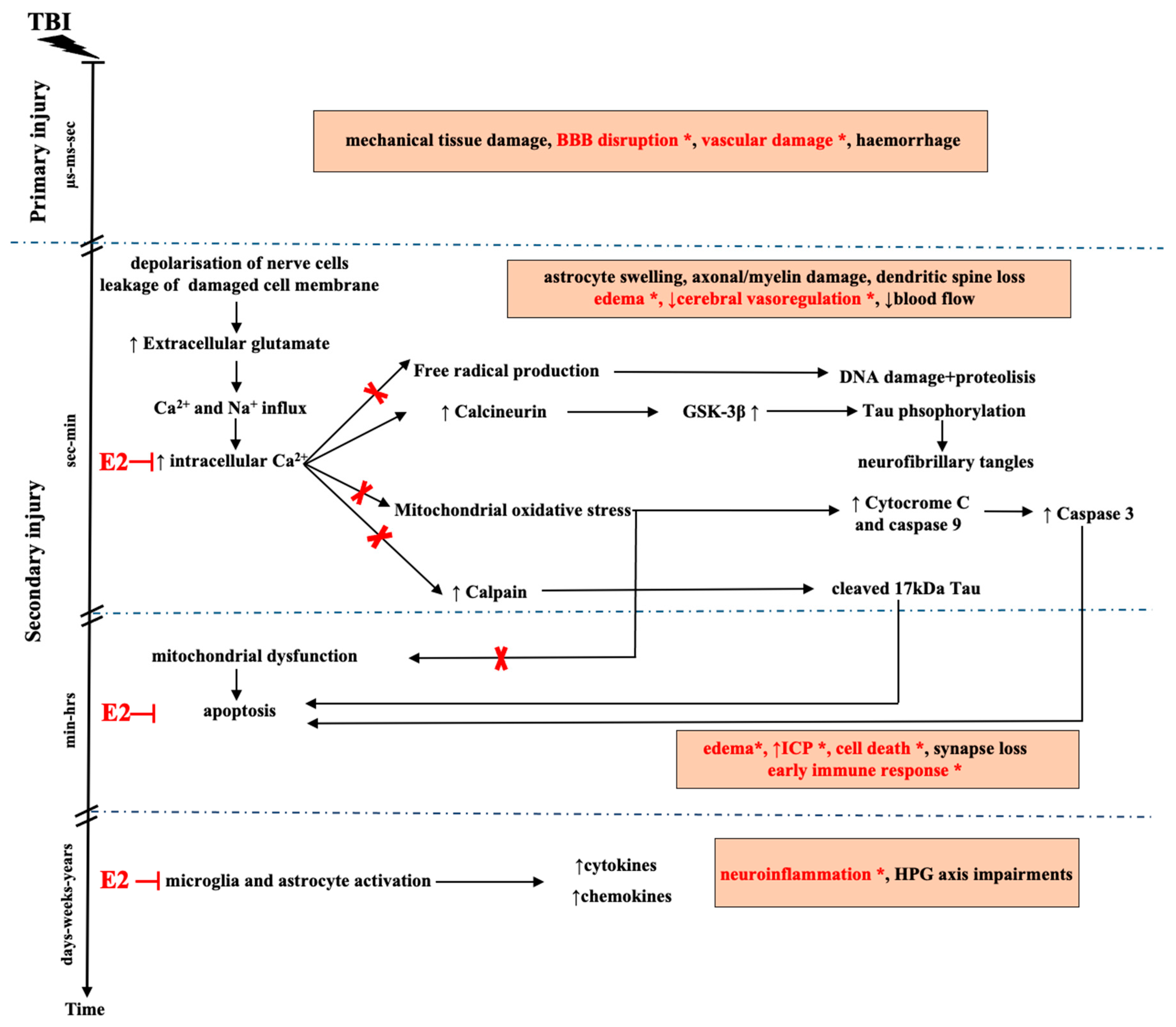

3. Pathomechanism of TBI

4. Animal Models of TBI

5. E2 and Neuroprotection

6. Potential Targets of E2 Action in TBI

6.1. E2 Effect on BBB and Mitochondria

6.2. Inhibition of TBI-Induced Intracellular Ca2+ Increase after E2 Application

6.3. Effect of E2 on the Calpain/Caspase Activity in TBI

6.4. Effect of E2 on Free Radical Production and Oxidative Stress after TBI

6.5. E2 and Inflammation in TBI

7. TBI and the Impairment of the HPG Axis

8. Potential Therapeutic Interventions with Estrogenic Compounds in TBI

9. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 3NPA | 3-nitropropionic acid |

| ANGELS | activator of non-genomic estrogen like signaling |

| AMPA | α-amino-3-hydroxy5-methyl-4-isoxazole-propionic acid |

| Bcl2 | B-cell lymphoma 2 |

| BZA | bazedoxifen |

| BBB | blood brain barrier |

| CCI | controlled cortical impact injury |

| CORT | cortisol |

| CPP | cerebral perfusion pressure |

| CREB | cAMP-responsive element-binding protein |

| CT | computed tomography |

| E2 | 17β-estradiol |

| eNOS | endothelial nitric oxide synthase |

| EPM | elevated plus maze |

| ERα | estrogen receptor alpha |

| ERβ | estrogen receptor beta |

| ERE | estrogen response element |

| ERK1/2 | extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 |

| FPI | fluid percussion injury |

| FSH | follicle stimulating hormone |

| GFAP | glial fibrillary acidic protein |

| GPER1 | G protein-coupled estrogen receptor 1 |

| GSK3β | glycogen synthase kinase 3 beta |

| HPG | hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal |

| HRT | hormonal replacement therapy |

| ICP | intracranial pressure |

| KNDy | kisspeptin, neurokinin B and dynorphin |

| LPF | lateral fluid percussion injury |

| LH | luteinizing hormone |

| MAPK | mitogen-activated protein kinase |

| MFP | midline fluid percussion injury |

| MPP | 1,3-Bis(4-hydroxyphenyl)-4-methyl-5-(4-(2-piperidinylethoxy)phenol)-1H-pyrazole hydrochloride |

| MRI | magnetic resonance imaging |

| MWM | Morris water maze |

| NF-κB | nuclear factor kappa B |

| NMDA | N-methyl-D-aspartic acid |

| OCs | oral contraceptives |

| OVX | ovariectomized |

| P2X7 | P2X purinoceptor 7 |

| p-ERK1/2 | phosphorylated extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1 and 2 |

| PI3K | phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase |

| PHTPP | 4-(2-Phenyl-5, 7-bis (trifluoromethyl) pyrazolo (1,5-a) pyrimidine-3- yl) phenol |

| SERMs | selective estrogen receptor modulators |

| ROS | reactive oxygen species |

| STEARs | selective tissue estrogenic activity regulators |

| TBI | traumatic brain injury |

| TNF-α | tumor necrosis factor alpha |

| TMX | tamoxifen |

| VGCCs | voltage-gated calcium channels |

References

- Menon, D.K.; Schwab, K.; Wright, D.W.; Maas, A.I. Demographics and clinical assessment working group of the international and interagency initiative toward common data elements for research on traumatic brain injury and psychological health. Position statement: Definition of traumatic brain injury. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2010, 91, 1637–1640. [Google Scholar]

- Maas, A.I.; Stocchetti, N.; Bullock, R. Moderate and severe traumatic brain injury in adults. Lancet Neurol. 2008, 7, 728–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustavsson, A.; Svensson, M.; Jacobi, F.; Allgulander, C.; Alonso, J.; Beghi, E.; Dodel, R.; Ekman, M.; Faravelli, C.; Fratiglioni, L.; et al. Cost of disorders of the brain in Europe 2010. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2011, 21, 718–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marik, P.E.; Varon, J.; Trask, T. Management of head trauma. Chest 2002, 122, 699–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riggio, S.; Wong, M. Neurobehavioral sequelae of traumatic brain injury. Mt. Sinai J. Med. 2009, 76, 163–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baethmann, A.; Maier-Hauff, K.; Kempski, O.; Unterberg, A.; Wahl, M.; Schurer, L. Mediators of brain edema and secondary brain damage. Crit. Care Med. 1988, 16, 972–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marklund, N.; Bakshi, A.; Castelbuono, D.J.; Conte, V.; McIntosh, T.K. Evaluation of pharmacological treatment strategies in traumatic brain injury. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2006, 12, 1645–1680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loane, D.J.; Faden, A.I. Neuroprotection for traumatic brain injury: Translational challenges and emerging therapeutic strategies. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2010, 31, 596–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McConeghy, K.W.; Hatton, J.; Hughes, L.; Cook, A.M. A review of neuroprotection pharmacology and therapies in patients with acute traumatic brain injury. CNS Drugs 2012, 26, 613–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angele, M.K.; Frantz, M.C.; Chaudry, I.H. Gender and sex hormones influence the response to trauma and sepsis: Potential therapeutic approaches. Clinics (Sao Paulo) 2006, 61, 479–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudry, I.H.; Bland, K.I. Cellular mechanisms of injury after major trauma. Br. J. Surg. 2009, 96, 1097–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haider, A.H.; Crompton, J.G.; Oyetunji, T.; Stevens, K.A.; Efron, D.T.; Kieninger, A.N.; Chang, D.C.; Cornwell, E.E.; Haut, E.R. Females have fewer complications and lower mortality following trauma than similarly injured males: A risk adjusted analysis of adults in the national trauma data bank. Surgery 2009, 146, 308–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Day, N.L.; Carle, M.S.; Floyd, C.L. Post-injury administration of a combination of memantine and 17beta-estradiol is protective in a rat model of traumatic brain injury. Neurochem. Int. 2017, 111, 57–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bao, Y.J.; Li, L.Z.; Li, X.G.; Wang, Y.J. 17Beta-estradiol differentially protects cortical pericontusional zone from programmed cell death after traumatic cerebral contusion at distinct stages via non-genomic and genomic pathways. Mol. Cell Neurosci. 2011, 48, 185–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Connor, C.A.; Cernak, I.; Vink, R. Both estrogen and progesterone attenuate edema formation following diffuse traumatic brain injury in rats. Brain Res. 2005, 1062, 171–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrone, A.B.; Gatson, J.W.; Simpkins, J.W.; Reed, M.N. Non-feminizing estrogens: A novel neuroprotective therapy. Mol. Cell Endocrinol. 2014, 389, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, D.W.; Yeatts, S.D.; Silbergleit, R.; Palesch, Y.Y.; Hertzberg, V.S.; Frankel, M.; Goldstein, F.C.; Caveney, A.F.; Howlett-Smith, H.; Bengelink, E.M.; et al. Very early administration of progesterone for acute traumatic brain injury. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014, 371, 2457–2466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mofid, B.; Soltani, Z.; Khaksari, M.; Shahrokhi, N.; Nakhaee, N.; Karamouzian, S.; Ahmadinejad, M.; Maiel, M.; Khazaeli, P. What are the progesterone-induced changes of the outcome and the serum markers of injury, oxidant activity and inflammation in diffuse axonal injury patients? Int. Immunopharmacol. 2016, 32, 103–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, K.A. Estrogen formation and inactivation following TBI: What we know and where we could go. Front. Endocrinol. 2020, 11, 345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin-Jimenez, C.; Gaitan-Vaca, D.M.; Areiza, N.; Echeverria, V.; Ashraf, G.M.; Gonzalez, J.; Sahebkar, A.; Garcia-Segura, L.M.; Barreto, G.E. Astrocytes mediate protective actions of estrogenic compounds after traumatic brain injury. Neuroendocrinology 2019, 108, 142–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaksari, M.; Soltani, Z.; Shahrokhi, N. Effects of female sex steroids administration on pathophysiologic mechanisms in traumatic brain injury. Transl. Stroke Res. 2018, 9, 393–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spani, C.B.; Braun, D.J.; Van Eldik, L.J. Sex-related responses after traumatic brain injury: Considerations for preclinical modeling. Front. Neuroendocrinol. 2018, 50, 52–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santiago, L.A.; Oh, B.C.; Dash, P.K.; Holcomb, J.B.; Wade, C.E. A clinical comparison of penetrating and blunt traumatic brain injuries. Brain Inj. 2012, 26, 107–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.J.; Segar, D.J.; Asaad, W.F. Comprehensive assessment of isolated traumatic subarachnoid hemorrhage. J. Neurotrauma. 2014, 31, 595–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGinn, M.J.; Povlishock, J.T. Pathophysiology of traumatic brain injury. Neurosurg. Clin. N. Am. 2016, 27, 397–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKee, A.C.; Daneshvar, D.H. The neuropathology of traumatic brain injury. Handb. Clin. Neurol. 2015, 127, 45–66. [Google Scholar]

- Graham, D.I.; Gennarelli, T.A.; McIntosh, T.K. Trauma. In Greenfield’s Neuropathology; Graham, D.I., Lantos, P.L., Eds.; Arnold: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Mondello, S.; Jeromin, A.; Buki, A.; Bullock, R.; Czeiter, E.; Kovacs, N.; Barzo, P.; Schmid, K.; Tortella, F.; Wang, K.K.; et al. Glial neuronal ratio: A novel index for differentiating injury type in patients with severe traumatic brain injury. J. Neurotrauma 2012, 29, 1096–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papa, L.; Lewis, L.M.; Falk, J.L.; Zhang, Z.; Silvestri, S.; Giordano, P.; Brophy, G.M.; Demery, J.A.; Dixit, N.K.; Ferguson, I.; et al. Elevated levels of serum glial fibrillary acidic protein breakdown products in mild and moderate traumatic brain injury are associated with intracranial lesions and neurosurgical intervention. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2012, 59, 471–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.K.; Yang, Z.; Yue, J.K.; Zhang, Z.; Winkler, E.A.; Puccio, A.M.; Diaz-Arrastia, R.; Lingsma, H.F.; Yuh, E.L.; Mukherjee, P.; et al. Plasma anti-glial fibrillary acidic protein autoantibody levels during the acute and chronic phases of traumatic brain injury: A transforming research and clinical knowledge in traumatic brain injury pilot study. J. Neurotrauma 2016, 33, 1270–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bramlett, H.M.; Dietrich, W.D. Pathophysiology of cerebral ischemia and brain trauma: Similarities and differences. J. Cereb. Blood Flow. Metab. 2004, 24, 133–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saatman, K.E.; Creed, J.; Raghupathi, R. Calpain as a therapeutic target in traumatic brain injury. Neurotherapeutics 2010, 7, 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bullock, R.; Zauner, A.; Woodward, J.J.; Myseros, J.; Choi, S.C.; Ward, J.D.; Marmarou, A.; Young, H.F. Factors affecting excitatory amino acid release following severe human head injury. J. Neurosurg. 1998, 89, 507–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koura, S.S.; Doppenberg, E.M.; Marmarou, A.; Choi, S.; Young, H.F.; Bullock, R. Relationship between excitatory amino acid release and outcome after severe human head injury. Acta. Neurochir. Suppl. 1998, 71, 244–246. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chamoun, R.; Suki, D.; Gopinath, S.P.; Goodman, J.C.; Robertson, C. Role of extracellular glutamate measured by cerebral microdialysis in severe traumatic brain injury. J. Neurosurg. 2010, 113, 564–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lozano, D.; Gonzales-Portillo, G.S.; Acosta, S.; de la Pena, I.; Tajiri, N.; Kaneko, Y.; Borlongan, C.V. Neuroinflammatory responses to traumatic brain injury: Etiology, clinical consequences, and therapeutic opportunities. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2015, 11, 97–106. [Google Scholar]

- Katayama, Y.; Becker, D.P.; Tamura, T.; Hovda, D.A. Massive increases in extracellular potassium and the indiscriminate release of glutamate following concussive brain injury. J. Neurosurg. 1990, 73, 889–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, P.; Hillered, L.; Olsson, Y.; Sheardown, M.J.; Hansen, A.J. Regional changes in interstitial K+ and Ca2+ levels following cortical compression contusion trauma in rats. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 1993, 13, 183–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinert, M.; Khaldi, A.; Zauner, A.; Doppenberg, E.; Choi, S.; Bullock, R. High level of extracellular potassium and its correlates after severe head injury: Relationship to high intracranial pressure. J. Neurosurg. 2000, 93, 800–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, L.; Gamal El-Din, T.M.; Payandeh, J.; Martinez, G.Q.; Heard, T.M.; Scheuer, T.; Zheng, N.; Catterall, W.A. Structural basis for Ca2+ selectivity of a voltage-gated calcium channel. Nature 2014, 505, 56–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanika, R.I.; Villanueva, I.; Kazanina, G.; Andrews, S.B.; Pivovarova, N.B. Comparative impact of voltage-gated calcium channels and NMDA receptors on mitochondria-mediated neuronal injury. J. Neurosci. 2012, 32, 6642–6650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbeloa, J.; Perez-Samartin, A.; Gottlieb, M.; Matute, C. P2X7 receptor blockade prevents ATP excitotoxicity in neurons and reduces brain damage after ischemia. Neurobiol. Dis. 2012, 45, 954–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blennow, K.; Hardy, J.; Zetterberg, H. The neuropathology and neurobiology of traumatic brain injury. Neuron 2012, 76, 886–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masel, B.E.; DeWitt, D.S. Traumatic brain injury: A disease process, not an event. J. Neurotrauma 2010, 27, 1529–1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reeves, T.M.; Greer, J.E.; Vanderveer, A.S.; Phillips, L.L. Proteolysis of submembrane cytoskeletal proteins ankyrin-G and alphaII-spectrin following diffuse brain injury: A role in white matter vulnerability at Nodes of Ranvier. Brain Pathol. 2010, 20, 1055–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keane, R.W.; Kraydieh, S.; Lotocki, G.; Alonso, O.F.; Aldana, P.; Dietrich, W.D. Apoptotic and antiapoptotic mechanisms after traumatic brain injury. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2001, 21, 1189–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurz, J.E.; Hamm, R.J.; Singleton, R.H.; Povlishock, J.T.; Churn, S.B. A persistent change in subcellular distribution of calcineurin following fluid percussion injury in the rat. Brain Res. 2005, 1048, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurz, J.E.; Parsons, J.T.; Rana, A.; Gibson, C.J.; Hamm, R.J.; Churn, S.B. A significant increase in both basal and maximal calcineurin activity following fluid percussion injury in the rat. J. Neurotrauma 2005, 22, 476–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, K.R.; Tesco, G. Molecular mechanisms of cognitive dysfunction following traumatic brain injury. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2013, 5, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunker, J.M.; Wilson, L.; Jordan, M.A.; Feinstein, S.C. Modulation of microtubule dynamics by tau in living cells: Implications for development and neurodegeneration. Mol. Biol. Cell 2004, 15, 2720–2728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maeda, S.; Sahara, N.; Saito, Y.; Murayama, M.; Yoshiike, Y.; Kim, H.; Miyasaka, T.; Murayama, S.; Ikai, A.; Takashima, A. Granular tau oligomers as intermediates of tau filaments. Biochemistry 2007, 46, 3856–3861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Pietro, V.; Lazzarino, G.; Amorini, A.M.; Tavazzi, B.; D’Urso, S.; Longo, S.; Vagnozzi, R.; Signoretti, S.; Clementi, E.; Giardina, B.; et al. Neuroglobin expression and oxidant/antioxidant balance after graded traumatic brain injury in the rat. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2014, 69, 258–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahuquillo, J.; Vilalta, A. Cooling the injured brain: How does moderate hypothermia influence the pathophysiology of traumatic brain injury. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2007, 13, 2310–2322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acosta, S.A.; Tajiri, N.; Shinozuka, K.; Ishikawa, H.; Grimmig, B.; Diamond, D.M.; Sanberg, P.R.; Bickford, P.C.; Kaneko, Y.; Borlongan, C.V. Long-term upregulation of inflammation and suppression of cell proliferation in the brain of adult rats exposed to traumatic brain injury using the controlled cortical impact model. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e53376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubiano, A.M.; Sanchez, A.I.; Estebanez, G.; Peitzman, A.; Sperry, J.; Puyana, J.C. The effect of admission spontaneous hypothermia on patients with severe traumatic brain injury. Injury 2013, 44, 1219–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feeney, D.M.; Boyeson, M.G.; Linn, R.T.; Murray, H.M.; Dail, W.G. Responses to cortical injury: I. Methodology and local effects of contusions in the rat. Brain Res. 1981, 211, 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapira, Y.; Shohami, E.; Sidi, A.; Soffer, D.; Freeman, S.; Cotev, S. Experimental closed head injury in rats: Mechanical, pathophysiologic, and neurologic properties. Crit. Care Med. 1988, 16, 258–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buki, A.; Kovesdi, E.; Pal, J.; Czeiter, E. Clinical and model research of neurotrauma. Methods Mol. Biol. 2009, 566, 41–55. [Google Scholar]

- Xiong, Y.; Mahmood, A.; Chopp, M. Animal models of traumatic brain injury. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2013, 14, 128–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, C.E.; Clifton, G.L.; Lighthall, J.W.; Yaghmai, A.A.; Hayes, R.L. A controlled cortical impact model of traumatic brain injury in the rat. J. Neurosci. Methods 1991, 39, 253–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Shi, J.; Jin, W.; Wang, L.; Xie, W.; Sun, J.; Hang, C. Progesterone administration modulates TLRs/NF-kappaB signaling pathway in rat brain after cortical contusion. Ann. Clin. Lab. Sci. 2008, 38, 65–74. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, S.L.; Hall, E.D. Mild pre- and posttraumatic hypothermia attenuates blood-brain barrier damage following controlled cortical impact injury in the rat. J. Neurotrauma 1996, 13, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, H.J.; Lifshitz, J.; Marklund, N.; Grady, M.S.; Graham, D.I.; Hovda, D.A.; McIntosh, T.K. Lateral fluid percussion brain injury: A 15-year review and evaluation. J. Neurotrauma 2005, 22, 42–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alder, J.; Fujioka, W.; Lifshitz, J.; Crockett, D.P.; Thakker-Varia, S. Lateral fluid percussion: Model of traumatic brain injury in mice. J. Vis. Exp. 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Connor, W.T.; Smyth, A.; Gilchrist, M.D. Animal models of traumatic brain injury: A critical evaluation. Pharmacol. Ther. 2011, 130, 106–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McIntosh, T.K.; Vink, R.; Noble, L.; Yamakami, I.; Fernyak, S.; Soares, H.; Faden, A.L. Traumatic brain injury in the rat: Characterization of a lateral fluid-percussion model. Neuroscience 1989, 28, 233–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hicks, R.; Soares, H.; Smith, D.; McIntosh, T. Temporal and spatial characterization of neuronal injury following lateral fluid-percussion brain injury in the rat. Acta. Neuropathol. 1996, 91, 236–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marmarou, A.; Foda, M.A.; van den Brink, W.; Campbell, J.; Kita, H.; Demetriadou, K. A new model of diffuse brain injury in rats. Part I: Pathophysiology and biomechanics. J. Neurosurg. 1994, 80, 291–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albert-Weissenberger, C.; Varrallyay, C.; Raslan, F.; Kleinschnitz, C.; Siren, A.L. An experimental protocol for mimicking pathomechanisms of traumatic brain injury in mice. Exp. Transl. Stroke Med. 2012, 4, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dail, W.G.; Feeney, D.M.; Murray, H.M.; Linn, R.T.; Boyeson, M.G. Responses to cortical injury: II. Widespread depression of the activity of an enzyme in cortex remote from a focal injury. Brain Res. 1981, 211, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales, D.M.; Marklund, N.; Lebold, D.; Thompson, H.J.; Pitkanen, A.; Maxwell, W.L.; Longhi, L.; Laurer, H.; Maegele, M.; Neugebauer, E.; et al. Experimental models of traumatic brain injury: Do we really need to build a better mousetrap? Neuroscience 2005, 136, 971–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikawa, S.; Kinouchi, H.; Kamii, H.; Gobbel, G.T.; Chen, S.F.; Carlson, E.; Epstein, C.J.; Chan, P.H. Attenuation of acute and chronic damage following traumatic brain injury in copper, zinc-superoxide dismutase transgenic mice. J. Neurosurg. 1996, 85, 885–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellander, B.M.; von Holst, H.; Fredman, P.; Svensson, M. Activation of the complement cascade and increase of clusterin in the brain following a cortical contusion in the adult rat. J. Neurosurg. 1996, 85, 468–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Constantini, S.; Trembovler, V.; Weinstock, M.; Shohami, E. An experimental model of closed head injury in mice: Pathophysiology, histopathology, and cognitive deficits. J. Neurotrauma 1996, 13, 557–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haisenleder, D.J.; Dalkin, A.C.; Ortolano, G.A.; Marshall, J.C.; Shupnik, M.A. A pulsatile gonadotropin-releasing hormone stimulus is required to increase transcription of the gonadotropin subunit genes: Evidence for differential regulation of transcription by pulse frequency in vivo. Endocrinology 1991, 128, 509–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, A.M.; Coolen, L.M.; Porter, D.T.; Goodman, R.L.; Lehman, M.N. KNDy cells revisited. Endocrinology 2018, 159, 3219–3234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Cho, H.T.; Kim, Y.J. The role of estrogen in adipose tissue metabolism: Insights into glucose homeostasis regulation. Endocr. J. 2014, 61, 1055–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanikova, D.; Luck, T.; Bae, Y.J.; Thiery, J.; Ceglarek, U.; Engel, C.; Enzenbach, C.; Wirkner, K.; Stanik, J.; Kratzsch, J.; et al. Increased estrogen level can be associated with depression in males. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2018, 87, 196–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boon, W.C.; Chow, J.D.; Simpson, E.R. The multiple roles of estrogens and the enzyme aromatase. Prog. Brain Res. 2010, 181, 209–232. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, J.C. Proceedings: Hormonal regulation of breast development and activity. J. Invest Dermatol. 1974, 63, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, H.A.; King, G.J. Plasma concentrations of progesterone, oestrone, oestradiol-17beta and of oestrone sulphate in the pig at implantation, during pregnancy and at parturition. J. Reprod. Fertil. 1974, 40, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, O.K.; Ramirez, V.D. Spontaneous changes in LHRH release during the rat estrous cycle, as measured with repetitive push-pull perfusions of the pituitary gland in the same female rats. Neuroendocrinology 1989, 50, 66–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, D.P.; Woolfrey, K.M.; Penzes, P. Insights into rapid modulation of neuroplasticity by brain estrogens. Pharmacol. Rev. 2013, 65, 1318–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia-Segura, L.M.; Wozniak, A.; Azcoitia, I.; Rodriguez, J.R.; Hutchison, R.E.; Hutchison, J.B. Aromatase expression by astrocytes after brain injury: Implications for local estrogen formation in brain repair. Neuroscience 1999, 89, 567–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saldanha, C.J.; Duncan, K.A.; Walters, B.J. Neuroprotective actions of brain aromatase. Front. Neuroendocrinol. 2009, 30, 106–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pedersen, A.L.; Brownrout, J.L.; Saldanha, C.J. Neuroinflammation and neurosteroidogenesis: Reciprocal modulation during injury to the adult zebra finch brain. Physiol. Behav. 2018, 187, 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duncan, K.A.; Walters, B.J.; Saldanha, C.J. Traumatized and inflamed--but resilient: Glial aromatization and the avian brain. Horm. Behav. 2013, 63, 208–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fokidis, H.B.; Adomat, H.H.; Kharmate, G.; Hosseini-Beheshti, E.; Guns, E.S.; Soma, K.K. Regulation of local steroidogenesis in the brain and in prostate cancer: Lessons learned from interdisciplinary collaboration. Front. Neuroendocrinol. 2015, 36, 108–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azcoitia, I.; Yague, J.G.; Garcia-Segura, L.M. Estradiol synthesis within the human brain. Neuroscience 2011, 191, 139–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do Rego, J.L.; Seong, J.Y.; Burel, D.; Leprince, J.; Luu-The, V.; Tsutsui, K.; Tonon, M.C.; Pelletier, G.; Vaudry, H. Neurosteroid biosynthesis: Enzymatic pathways and neuroendocrine regulation by neurotransmitters and neuropeptides. Front. Neuroendocrinol. 2009, 30, 259–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merchenthaler, I.; Dellovade, T.L.; Shughrue, P.J. Neuroprotection by estrogen in animal models of global and focal ischemia. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2003, 1007, 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pike, A.C.; Brzozowski, A.M.; Hubbard, R.E. A structural biologist’s view of the oestrogen receptor. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2000, 74, 261–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verderame, M.; Scudiero, R. A comparative review on estrogen receptors in the reproductive male tract of non mammalian vertebrates. Steroids 2018, 134, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuiper, G.G.; Carlsson, B.; Grandien, K.; Enmark, E.; Haggblad, J.; Nilsson, S.; Gustafsson, J.A. Comparison of the ligand binding specificity and transcript tissue distribution of estrogen receptors alpha and beta. Endocrinology 1997, 138, 863–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cersosimo, M.G.; Benarroch, E.E. Estrogen actions in the nervous system: Complexity and clinical implications. Neurology 2015, 85, 263–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marin, R.; Casanas, V.; Perez, J.A.; Fabelo, N.; Fernandez, C.E.; Diaz, M. Oestrogens as modulators of neuronal signalosomes and brain lipid homeostasis related to protection against neurodegeneration. J. Neuroendocrinol. 2013, 25, 1104–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, R.; Cui, J.; Shen, Y. Brain sex matters: Estrogen in cognition and Alzheimer’s disease. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2014, 389, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shughrue, P.J.; Lane, M.V.; Merchenthaler, I. Comparative distribution of estrogen receptor-alpha and -beta mRNA in the rat central nervous system. J. Comp. Neurol. 1997, 388, 507–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, D.F.; Toft, D.O. Steroid receptors and their associated proteins. Mol Endocrinol 1993, 7, 4–11. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- McKenna, N.J.; Lanz, R.B.; O’Malley, B.W. Nuclear receptor coregulators: Cellular and molecular biology. Endocr. Rev. 1999, 20, 321–344. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Klinge, C.M. Estrogen receptor interaction with estrogen response elements. Nucleic Acids. Res. 2001, 29, 2905–2919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marino, M.; Galluzzo, P.; Ascenzi, P. Estrogen signaling multiple pathways to impact gene transcription. Curr. Genom. 2006, 7, 497–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revankar, C.M.; Cimino, D.F.; Sklar, L.A.; Arterburn, J.B.; Prossnitz, E.R. A transmembrane intracellular estrogen receptor mediates rapid cell signaling. Science 2005, 307, 1625–1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sawe, N.; Steinberg, G.; Zhao, H. Dual roles of the MAPK/ERK1/2 cell signaling pathway after stroke. J. Neurosci. Res. 2008, 86, 1659–1669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simoncini, T.; Hafezi-Moghadam, A.; Brazil, D.P.; Ley, K.; Chin, W.W.; Liao, J.K. Interaction of oestrogen receptor with the regulatory subunit of phosphatidylinositol-3-OH kinase. Nature 2000, 407, 538–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malyala, A.; Zhang, C.; Bryant, D.N.; Kelly, M.J.; Ronnekleiv, O.K. PI3K signaling effects in hypothalamic neurons mediated by estrogen. J. Comp. Neurol. 2008, 506, 895–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drevensek, G. 17β-Estradiol as a Neuroprotective Agen. In Sex Hormones in Neurodegenerative Processes and Diseases; Drevenšek, G., Ed.; IntechOpen: Rijeka, Croatia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Abraham, I.M.; Han, S.K.; Todman, M.G.; Korach, K.S.; Herbison, A.E. Estrogen receptor beta mediates rapid estrogen actions on gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons in vivo. J. Neurosci. 2003, 23, 5771–5777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlstrom, L.; Ke, Z.J.; Unnerstall, J.R.; Cohen, R.S.; Pandey, S.C. Estrogen modulation of the cyclic AMP response element-binding protein pathway. Effects of long-term and acute treatments. Neuroendocrinology 2001, 74, 227–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azcoitia, I.; Barreto, G.E.; Garcia-Segura, L.M. Molecular mechanisms and cellular events involved in the neuroprotective actions of estradiol. Analysis of sex differences. Front. Neuroendocrinol. 2019, 55, 100787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, P.S.; Bishop, J.; Simpkins, J.W. 17 alpha-estradiol exerts neuroprotective effects on SK-N-SH cells. J. Neurosci. 1997, 17, 511–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, P.S.; Gordon, K.; Simpkins, J.W. Phenolic a ring requirement for the neuroprotective effects of steroids. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 1997, 63, 229–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, P.S.; Gridley, K.E.; Simpkins, J.W. Nuclear estrogen receptor-independent neuroprotection by estratrienes: A novel interaction with glutathione. Neuroscience 1998, 84, 7–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pike, C.J. Estrogen modulates neuronal Bcl-xL expression and beta-amyloid-induced apoptosis: Relevance to Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neurochem. 1999, 72, 1552–1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Behl, C.; Widmann, M.; Trapp, T.; Holsboer, F. 17-beta estradiol protects neurons from oxidative stress-induced cell death in vitro. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1995, 216, 473–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sawada, H.; Ibi, M.; Kihara, T.; Urushitani, M.; Honda, K.; Nakanishi, M.; Akaike, A.; Shimohama, S. Mechanisms of antiapoptotic effects of estrogens in nigral dopaminergic neurons. FASEB J. 2000, 14, 1202–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perez, E.; Liu, R.; Yang, S.H.; Cai, Z.Y.; Covey, D.F.; Simpkins, J.W. Neuroprotective effects of an estratriene analog are estrogen receptor independent in vitro and in vivo. Brain Res. 2005, 1038, 216–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wise, P.M.; Dubal, D.B. Estradiol protects against ischemic brain injury in middle-aged rats. Biol. Reprod. 2000, 63, 982–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engler-Chiurazzi, E.B.; Singh, M.; Simpkins, J.W. From the 90′s to now: A brief historical perspective on more than two decades of estrogen neuroprotection. Brain Res. 2016, 1633, 96–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukuda, K.; Yao, H.; Ibayashi, S.; Nakahara, T.; Uchimura, H.; Fujishima, M.; Hall, E.D. Ovariectomy exacerbates and estrogen replacement attenuates photothrombotic focal ischemic brain injury in rats. Stroke 2000, 31, 155–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morissette, M.; Le Saux, M.; D’Astous, M.; Jourdain, S.; Al Sweidi, S.; Morin, N.; Estrada-Camarena, E.; Mendez, P.; Garcia-Segura, L.M.; Di Paolo, T. Contribution of estrogen receptors alpha and beta to the effects of estradiol in the brain. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2008, 108, 327–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Sweidi, S.; Sanchez, M.G.; Bourque, M.; Morissette, M.; Dluzen, D.; Di Paolo, T. Oestrogen receptors and signalling pathways: Implications for neuroprotective effects of sex steroids in Parkinson’s disease. J. Neuroendocrinol. 2012, 24, 48–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerra, B.; Diaz, M.; Alonso, R.; Marin, R. Plasma membrane oestrogen receptor mediates neuroprotection against beta-amyloid toxicity through activation of Raf-1/MEK/ERK cascade in septal-derived cholinergic SN56 cells. J. Neurochem. 2004, 91, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marin, R.; Guerra, B.; Morales, A.; Diaz, M.; Alonso, R. An oestrogen membrane receptor participates in estradiol actions for the prevention of amyloid-beta peptide1-40-induced toxicity in septal-derived cholinergic SN56 cells. J. Neurochem. 2003, 85, 1180–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spence, R.D.; Wisdom, A.J.; Cao, Y.; Hill, H.M.; Mongerson, C.R.; Stapornkul, B.; Itoh, N.; Sofroniew, M.V.; Voskuhl, R.R. Estrogen mediates neuroprotection and anti-inflammatory effects during EAE through ERalpha signaling on astrocytes but not through ERbeta signaling on astrocytes or neurons. J. Neurosci. 2013, 33, 10924–10933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bramlett, H.M.; Dietrich, W.D. Neuropathological protection after traumatic brain injury in intact female rats versus males or ovariectomized females. J. Neurotrauma 2001, 18, 891–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roof, R.L.; Hall, E.D. Estrogen-related gender difference in survival rate and cortical blood flow after impact-acceleration head injury in rats. J. Neurotrauma 2000, 17, 1155–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, H.; Ma, K.; Jin, L.; Zhu, H.; Cao, R. 17beta-estradiol rescues damages following traumatic brain injury from molecule to behavior in mice. J. Cell. Physiol. 2018, 233, 1712–1722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaksari, M.; Hajializadeh, Z.; Shahrokhi, N.; Esmaeili-Mahani, S. Changes in the gene expression of estrogen receptors involved in the protective effect of estrogen in rat’s trumatic brain injury. Brain Res. 2015, 1618, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahrokhi, N.; Khaksari, M.; Soltani, Z.; Mahmoodi, M.; Nakhaee, N. Effect of sex steroid hormones on brain edema, intracranial pressure, and neurologic outcomes after traumatic brain injury. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2010, 88, 414–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duckles, S.P.; Krause, D.N. Mechanisms of cerebrovascular protection: Oestrogen, inflammation and mitochondria. Acta. Physiol. (Oxf) 2011, 203, 149–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakrabarti, S.; Lekontseva, O.; Davidge, S.T. Estrogen is a modulator of vascular inflammation. IUBMB Life 2008, 60, 376–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naderi, V.; Khaksari, M.; Abbasi, R.; Maghool, F. Estrogen provides neuroprotection against brain edema and blood brain barrier disruption through both estrogen receptors alpha and beta following traumatic brain injury. Iran. J. Basic Med. Sci. 2015, 18, 138–144. [Google Scholar]

- Nakagami, F.; Nakagami, H.; Osako, M.K.; Iwabayashi, M.; Taniyama, Y.; Doi, T.; Shimizu, H.; Shimamura, M.; Rakugi, H.; Morishita, R. Estrogen attenuates vascular remodeling in Lp(a) transgenic mice. Atherosclerosis 2010, 211, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bake, S.; Friedman, J.A.; Sohrabji, F. Reproductive age-related changes in the blood brain barrier: Expression of IgG and tight junction proteins. Microvasc. Res. 2009, 78, 413–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burek, M.; Arias-Loza, P.A.; Roewer, N.; Forster, C.Y. Claudin-5 as a novel estrogen target in vascular endothelium. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2010, 30, 298–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, J.; Krause, D.N.; Horne, J.; Weiss, J.H.; Li, X.; Duckles, S.P. Estrogen-receptor-mediated protection of cerebral endothelial cell viability and mitochondrial function after ischemic insult in vitro. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2010, 30, 545–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpkins, J.W.; Dykens, J.A. Mitochondrial mechanisms of estrogen neuroprotection. Brain Res. Rev. 2008, 57, 421–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, S.; Jun, S.; Simpkins, J.W. Estrogen amelioration of Abeta-induced defects in mitochondria is mediated by mitochondrial signaling pathway involving ERbeta, AKAP and Drp1. Brain Res. 2015, 1616, 101–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsen, J.; Brinton, R.D. Mitochondria as therapeutic targets of estrogen action in the central nervous system. Curr. Drug Targets CNS Neurol. Disord. 2004, 3, 297–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Brinton, R.D. Estrogen receptor alpha and beta differentially regulate intracellular Ca(2+) dynamics leading to ERK phosphorylation and estrogen neuroprotection in hippocampal neurons. Brain Res. 2007, 1172, 48–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zup, S.L.; Madden, A.M. Gonadal hormone modulation of intracellular calcium as a mechanism of neuroprotection. Front. Neuroendocrinol. 2016, 42, 40–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sribnick, E.A.; Del Re, A.M.; Ray, S.K.; Woodward, J.J.; Banik, N.L. Estrogen attenuates glutamate-induced cell death by inhibiting Ca2+ influx through L-type voltage-gated Ca2+ channels. Brain Res. 2009, 1276, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Alkayed, N.J.; Goto, S.; Sugo, N.; Joh, H.D.; Klaus, J.; Crain, B.J.; Bernard, O.; Traystman, R.J.; Hurn, P.D. Estrogen and Bcl-2: Gene induction and effect of transgene in experimental stroke. J. Neurosci. 2001, 21, 7543–7550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Bhavnani, B.R. Glutamate-induced apoptosis in neuronal cells is mediated via caspase-dependent and independent mechanisms involving calpain and caspase-3 proteases as well as apoptosis inducing factor (AIF) and this process is inhibited by equine estrogens. BMC Neurosci. 2006, 7, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raghupathi, R. Cell death mechanisms following traumatic brain injury. Brain Pathol. 2004, 14, 215–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, J.M.; Shu, H.; Wang, L.; Xu, J.J.; Niu, X.C.; Zhang, L. SIRT1-dependent AMPK pathway in the protection of estrogen against ischemic brain injury. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 2017, 23, 360–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nuzzo, M.T.; Fiocchetti, M.; Totta, P.; Melone, M.A.B.; Cardinale, A.; Fusco, F.R.; Gustincich, S.; Persichetti, F.; Ascenzi, P.; Marino, M. Huntingtin polyQ mutation Impairs the 17beta-estradiol/neuroglobin pathway devoted to neuron survival. Mol. Neurobiol. 2017, 54, 6634–6646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Marinis, E.; Acaz-Fonseca, E.; Arevalo, M.A.; Ascenzi, P.; Fiocchetti, M.; Marino, M.; Garcia-Segura, L.M. 17beta-Oestradiol anti-inflammatory effects in primary astrocytes require oestrogen receptor beta-mediated neuroglobin up-regulation. J. Neuroendocrinol. 2013, 25, 260–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, M.; Nguyen, T.V.; Pike, C.J. Estrogen regulates Bcl-w and Bim expression: Role in protection against beta-amyloid peptide-induced neuronal death. J. Neurosci. 2007, 27, 1422–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.A.; Zhang, R.; Varma, A.K.; Das, A.; Ray, S.K.; Banik, N.L. Estrogen partially down-regulates PTEN to prevent apoptosis in VSC4.1 motoneurons following exposure to IFN-gamma. Brain Res. 2009, 1301, 163–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.Z.; Bao, Y.J.; Zhao, M. 17beta-estradiol attenuates programmed cell death in cortical pericontusional zone following traumatic brain injury via upregulation of ERalpha and inhibition of caspase-3 activation. Neurochem. Int. 2011, 58, 126–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliev, G.; Smith, M.A.; Seyidov, D.; Neal, M.L.; Lamb, B.T.; Nunomura, A.; Gasimov, E.K.; Vinters, H.V.; Perry, G.; LaManna, J.C.; et al. The role of oxidative stress in the pathophysiology of cerebrovascular lesions in Alzheimer’s disease. Brain Pathol. 2002, 12, 21–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calabrese, V.; Scapagnini, G.; Giuffrida Stella, A.M.; Bates, T.E.; Clark, J.B. Mitochondrial involvement in brain function and dysfunction: Relevance to aging, neurodegenerative disorders and longevity. Neurochem. Res. 2001, 26, 739–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Dykens, J.A.; Perez, E.; Liu, R.; Yang, S.; Covey, D.F.; Simpkins, J.W. Neuroprotective effects of 17beta-estradiol and nonfeminizing estrogens against H2O2 toxicity in human neuroblastoma SK-N-SH cells. Mol. Pharmacol. 2006, 70, 395–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishihara, Y.; Takemoto, T.; Ishida, A.; Yamazaki, T. Protective actions of 17beta-estradiol and progesterone on oxidative neuronal injury induced by organometallic compounds. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2015, 2015, 343706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Filardo, E.J.; Quinn, J.A.; Bland, K.I.; Frackelton, A.R., Jr. Estrogen-induced activation of Erk-1 and Erk-2 requires the G protein-coupled receptor homolog, GPR30, and occurs via trans-activation of the epidermal growth factor receptor through release of HB-EGF. Mol. Endocrinol. 2000, 14, 1649–1660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murakoshi, M.; Ikada, R.; Tagawa, M. Regulation of prostatic glutathione-peroxidase (GSH-PO) in rats treated with a combination of testosterone and 17 beta-estradiol. J. Toxicol. Sci. 1999, 24, 415–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vegeto, E.; Benedusi, V.; Maggi, A. Estrogen anti-inflammatory activity in brain: A therapeutic opportunity for menopause and neurodegenerative diseases. Front. Neuroendocrinol. 2008, 29, 507–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Simpkins, J.W.; Dykens, J.A.; Cammarata, P.R. Oxidative damage to human lens epithelial cells in culture: Estrogen protection of mitochondrial potential, ATP, and cell viability. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2003, 44, 2067–2075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vegeto, E.; Belcredito, S.; Ghisletti, S.; Meda, C.; Etteri, S.; Maggi, A. The endogenous estrogen status regulates microglia reactivity in animal models of neuroinflammation. Endocrinology 2006, 147, 2263–2272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Zendedel, A.; Monnink, F.; Hassanzadeh, G.; Zaminy, A.; Ansar, M.M.; Habib, P.; Slowik, A.; Kipp, M.; Beyer, C. Estrogen attenuates local inflammasome expression and activation after spinal cord injury. Mol. Neurobiol. 2018, 55, 1364–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Alvarez, M.J.; Villa Gonzalez, M.; Benito-Cuesta, I.; Wandosell, F.G. Role of mTORC1 controlling proteostasis after brain ischemia. Front. Neurosci. 2018, 12, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Qin, P.; Deng, Y.; Ma, Z.; Guo, H.; Guo, H.; Hou, Y.; Wang, S.; Zou, W.; Sun, Y.; et al. The novel estrogenic receptor GPR30 alleviates ischemic injury by inhibiting TLR4-mediated microglial inflammation. J. Neuroinflamm. 2018, 15, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopez Rodriguez, A.B.; Mateos Vicente, B.; Romero-Zerbo, S.Y.; Rodriguez-Rodriguez, N.; Bellini, M.J.; Rodriguez de Fonseca, F.; Bermudez-Silva, F.J.; Azcoitia, I.; Garcia-Segura, L.M.; Viveros, M.P. Estradiol decreases cortical reactive astrogliosis after brain injury by a mechanism involving cannabinoid receptors. Cereb. Cortex 2011, 21, 2046–2055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarkaki, A.R.; Khaksari Haddad, M.; Soltani, Z.; Shahrokhi, N.; Mahmoodi, M. Time- and dose-dependent neuroprotective effects of sex steroid hormones on inflammatory cytokines after a traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma 2013, 30, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conti, A.; Guli, C.; La Torre, D.; Tomasello, C.; Angileri, F.F.; Aguennouz, M. Role of inflammation and oxidative stress mediators in gliomas. Cancers (Basel) 2010, 2, 693–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ospina, J.A.; Brevig, H.N.; Krause, D.N.; Duckles, S.P. Estrogen suppresses IL-1beta-mediated induction of COX-2 pathway in rat cerebral blood vessels. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2004, 286, H2010-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghisletti, S.; Meda, C.; Maggi, A.; Vegeto, E. 17beta-estradiol inhibits inflammatory gene expression by controlling NF-kappaB intracellular localization. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2005, 25, 2957–2968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, A.; Fazal, F. Blocking NF-kappaB: An inflammatory issue. Proc. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2011, 8, 497–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohrabji, F.; Miranda, R.C.; Toran-Allerand, C.D. Identification of a putative estrogen response element in the gene encoding brain-derived neurotrophic factor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1995, 92, 11110–11114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leon, R.L.; Li, X.; Huber, J.D.; Rosen, C.L. Worsened outcome from middle cerebral artery occlusion in aged rats receiving 17beta-estradiol. Endocrinology 2012, 153, 3386–3393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, S.; Brown, C.M.; Dela Cruz, C.D.; Yang, E.; Bridwell, D.A.; Wise, P.M. Timing of estrogen therapy after ovariectomy dictates the efficacy of its neuroprotective and antiinflammatory actions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2007, 104, 6013–6018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvamani, A.; Sohrabji, F. Reproductive age modulates the impact of focal ischemia on the forebrain as well as the effects of estrogen treatment in female rats. Neurobiol. Aging 2010, 31, 1618–1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sohrabji, F.; Bake, S.; Lewis, D.K. Age-related changes in brain support cells: Implications for stroke severity. Neurochem. Int. 2013, 63, 291–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Westwood, F.R. The female rat reproductive cycle: A practical histological guide to staging. Toxicol. Pathol. 2008, 36, 375–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barton, D.J.; Kumar, R.G.; McCullough, E.H.; Galang, G.; Arenth, P.M.; Berga, S.L.; Wagner, A.K. Persistent hypogonadotropic hypogonadism in men after severe traumatic brain injury: Temporal hormone profiles and outcome prediction. J. Head Trauma Rehabil. 2016, 31, 277–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carlson, N.E.; Brenner, L.A.; Wierman, M.E.; Harrison-Felix, C.; Morey, C.; Gallagher, S.; Ripley, D. Hypogonadism on admission to acute rehabilitation is correlated with lower functional status at admission and discharge. Brain Inj. 2009, 23, 336–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, A.K.; McCullough, E.H.; Niyonkuru, C.; Ozawa, H.; Loucks, T.L.; Dobos, J.A.; Brett, C.A.; Santarsieri, M.; Dixon, C.E.; Berga, S.L.; et al. Acute serum hormone levels: Characterization and prognosis after severe traumatic brain injury. J. Neurotrauma 2011, 28, 871–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bavisetty, S.; Bavisetty, S.; McArthur, D.L.; Dusick, J.R.; Wang, C.; Cohan, P.; Boscardin, W.J.; Swerdloff, R.; Levin, H.; Chang, D.J.; et al. Chronic hypopituitarism after traumatic brain injury: Risk assessment and relationship to outcome. Neurosurgery 2008, 62, 1080–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinton, R.D. Neurosteroids as regenerative agents in the brain: Therapeutic implications. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2013, 9, 241–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranganathan, P.; Kumar, R.G.; Davis, K.; McCullough, E.H.; Berga, S.L.; Wagner, A.K. Longitudinal sex and stress hormone profiles among reproductive age and post-menopausal women after severe TBI: A case series analysis. Brain Inj. 2016, 30, 452–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melcangi, R.C.; Giatti, S.; Garcia-Segura, L.M. Levels and actions of neuroactive steroids in the nervous system under physiological and pathological conditions: Sex-specific features. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2016, 67, 25–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chisu, V.; Manca, P.; Lepore, G.; Gadau, S.; Zedda, M.; Farina, V. Testosterone induces neuroprotection from oxidative stress. Effects on catalase activity and 3-nitro-L-tyrosine incorporation into alpha-tubulin in a mouse neuroblastoma cell line. Arch. Ital. Biol. 2006, 144, 63–73. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hammond, J.; Le, Q.; Goodyer, C.; Gelfand, M.; Trifiro, M.; LeBlanc, A. Testosterone-mediated neuroprotection through the androgen receptor in human primary neurons. J. Neurochem. 2001, 77, 1319–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huppenbauer, C.B.; Tanzer, L.; DonCarlos, L.L.; Jones, K.J. Gonadal steroid attenuation of developing hamster facial motoneuron loss by axotomy: Equal efficacy of testosterone, dihydrotestosterone, and 17-beta estradiol. J. Neurosci. 2005, 25, 4004–4013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, T.V.; Yao, M.; Pike, C.J. Androgens activate mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling: Role in neuroprotection. J. Neurochem. 2005, 94, 1639–1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soustiel, J.F.; Palzur, E.; Nevo, O.; Thaler, I.; Vlodavsky, E. Neuroprotective anti-apoptosis effect of estrogens in traumatic brain injury. J. Neurotrauma 2005, 22, 345–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zolin, S.J.; Vodovotz, Y.; Forsythe, R.M.; Rosengart, M.R.; Namas, R.; Brown, J.B.; Peitzman, A.P.; Billiar, T.R.; Sperry, J.L. The early evolving sex hormone environment is associated with significant outcome and inflammatory response differences after injury. J. Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2015, 78, 451–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beale, E.; Zhu, J.; Belzberg, H. Changes in serum cortisol with age in critically ill patients. Gerontology 2002, 48, 84–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, A.K.; Dossett, L.A.; Norris, P.R.; Hansen, E.N.; Dorsett, R.C.; Popovsky, K.A.; Sawyer, R.G. Estradiol is associated with mortality in critically ill trauma and surgical patients. Crit. Care Med. 2008, 36, 62–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, E.R.; Merrill, J.C.; Hollub, A.J.; Graham-Lorence, S.; Mendelson, C.R. Regulation of estrogen biosynthesis by human adipose cells. Endocr. Rev. 1989, 10, 136–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colantonio, A.; Mar, W.; Escobar, M.; Yoshida, K.; Velikonja, D.; Rizoli, S.; Cusimano, M.; Cullen, N. Women’s health outcomes after traumatic brain injury. J. Womens Health (Larchmt) 2010, 19, 1109–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortress, A.M.; Avcu, P.; Wagner, A.K.; Dixon, C.E.; Pang, K.C.H. Experimental traumatic brain injury results in estrous cycle disruption, neurobehavioral deficits, and impaired GSK3beta/beta-catenin signaling in female rats. Exp. Neurol. 2019, 315, 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnes, D.E.; Kaup, A.; Kirby, K.A.; Byers, A.L.; Diaz-Arrastia, R.; Yaffe, K. Traumatic brain injury and risk of dementia in older veterans. Neurology 2014, 83, 312–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gardner, R.C.; Burke, J.F.; Nettiksimmons, J.; Kaup, A.; Barnes, D.E.; Yaffe, K. Dementia risk after traumatic brain injury vs nonbrain trauma: The role of age and severity. JAMA Neurol. 2014, 71, 1490–1497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berga, S.L.; Daniels, T.L.; Giles, D.E. Women with functional hypothalamic amenorrhea but not other forms of anovulation display amplified cortisol concentrations. Fertil. Steril. 1997, 67, 1024–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biller, B.M.; Federoff, H.J.; Koenig, J.I.; Klibanski, A. Abnormal cortisol secretion and responses to corticotropin-releasing hormone in women with hypothalamic amenorrhea. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1990, 70, 311–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spratt, D.I.; Kramer, R.S.; Morton, J.R.; Lucas, F.L.; Becker, K.; Longcope, C. Characterization of a prospective human model for study of the reproductive hormone responses to major illness. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2008, 295, E63–E69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bughi, S.; Shaw, S.J.; Mahmood, G.; Atkins, R.H.; Szlachcic, Y. Amenorrhea, pregnancy, and pregnancy outcomes in women following spinal cord injury: A retrospective cross-sectional study. Endocr. Pract. Off. J. Am. Coll. Endocrinol. Am. Assoc. Clin. Endocrinol. 2008, 14, 437–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niemeier, J.P.; Perrin, P.B.; Hurst, B.S.; Foureau, D.M.; Huynh, T.T.; Evans, S.L.; Silverman, J.E.; Elise McClannahan, M.; Brusch, B.D.; Newman, M.; et al. A repeated measures pilot comparison of trajectories of fluctuating endogenous hormones in young women with traumatic brain Injury, healthy controls. Behav. Neurol. 2019, 2019, 7694503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freedman, M.A. Quality of life and menopause: The role of estrogen. J. Womens Health (Larchmt) 2002, 11, 703–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherwin, B.B.; Henry, J.F. Brain aging modulates the neuroprotective effects of estrogen on selective aspects of cognition in women: A critical review. Front. Neuroendocr. 2008, 29, 88–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manson, J.E.; Hsia, J.; Johnson, K.C.; Rossouw, J.E.; Assaf, A.R.; Lasser, N.L.; Trevisan, M.; Black, H.R.; Heckbert, S.R.; Detrano, R.; et al. Women’s Health Initiative, I., Estrogen plus progestin and the risk of coronary heart disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003, 349, 523–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wassertheil-Smoller, S.; Hendrix, S.L.; Limacher, M.; Heiss, G.; Kooperberg, C.; Baird, A.; Kotchen, T.; Curb, J.D.; Black, H.; Rossouw, J.E.; et al. Investigators, W.H.I. Effect of estrogen plus progestin on stroke in postmenopausal women: The Women’s Health Initiative: A randomized trial. JAMA 2003, 289, 2673–2684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, G.L.; Limacher, M.; Assaf, A.R.; Bassford, T.; Beresford, S.A.; Black, H.; Bonds, D.; Brunner, R.; Brzyski, R.; Caan, B.; et al. Women’s Health Initiative Steering, C., Effects of conjugated equine estrogen in postmenopausal women with hysterectomy: The Women’s Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2004, 291, 1701–1712. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Engler-Chiurazzi, E.B.; Brown, C.M.; Povroznik, J.M.; Simpkins, J.W. Estrogens as neuroprotectants: Estrogenic actions in the context of cognitive aging and brain injury. Prog. Neurobiol. 2017, 157, 188–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, E.; Zhang, Q.G.; Wang, R.; Vadlamudi, R.; Brann, D. Estrogen neuroprotection and the critical period hypothesis. Front. Neuroendocr. 2012, 33, 85–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocca, W.A.; Grossardt, B.R.; Shuster, L.T. Oophorectomy, estrogen, and dementia: A 2014 update. Mol. Cell Endocrinol. 2014, 389, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otto, C.; Fuchs, I.; Altmann, H.; Klewer, M.; Schwarz, G.; Bohlmann, R.; Nguyen, D.; Zorn, L.; Vonk, R.; Prelle, K.; et al. In vivo characterization of estrogen receptor modulators with reduced genomic versus nongenomic activity in vitro. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2008, 111, 95–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kousteni, S.; Bellido, T.; Plotkin, L.I.; O’Brien, C.A.; Bodenner, D.L.; Han, L.; Han, K.; DiGregorio, G.B.; Katzenellenbogen, J.A.; Katzenellenbogen, B.S.; et al. Nongenotropic, sex-nonspecific signaling through the estrogen or androgen receptors: Dissociation from transcriptional activity. Cell 2001, 104, 719–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koszegi, Z.; Szego, E.M.; Cheong, R.Y.; Tolod-Kemp, E.; Abraham, I.M. Postlesion estradiol treatment increases cortical cholinergic innervations via estrogen receptor-alpha dependent nonclassical estrogen signaling in vivo. Endocrinology 2011, 152, 3471–3482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwakowsky, A.; Potapov, K.; Kim, S.; Peppercorn, K.; Tate, W.P.; Abraham, I.M. Treatment of beta amyloid 1-42 (Abeta(1-42))-induced basal forebrain cholinergic damage by a non-classical estrogen signaling activator in vivo. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 21101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soltani, Z.; Khaksari, M.; Jafari, E.; Iranpour, M.; Shahrokhi, N. Is genistein neuroprotective in traumatic brain injury? Physiol. Behav. 2015, 152(Pt A), 26–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azcoitia, I.; Moreno, A.; Carrero, P.; Palacios, S.; Garcia-Segura, L.M. Neuroprotective effects of soy phytoestrogens in the rat brain. Gynecol. Endocrinol. 2006, 22, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qian, Y.; Guan, T.; Huang, M.; Cao, L.; Li, Y.; Cheng, H.; Jin, H.; Yu, D. Neuroprotection by the soy isoflavone, genistein, via inhibition of mitochondria-dependent apoptosis pathways and reactive oxygen induced-NF-kappaB activation in a cerebral ischemia mouse model. Neurochem. Int. 2012, 60, 759–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Li, Z.; Yan, H.; Qin, J.; Li, T. Formononetin inhibits human bladder cancer cell proliferation and invasiveness via regulation of miR-21 and PTEN. Food Funct. 2017, 8, 1061–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu, G.; Tian, W.; Huan, M.; Chen, J.; Fu, H. Formononetin exhibits anti-hyperglycemic activity in alloxan-induced type 1 diabetic mice. Exp. Biol. Med. (Maywood) 2017, 242, 223–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Zeng, G.; Zheng, X.; Wang, W.; Ling, Y.; Tang, H.; Zhang, J. Neuroprotective effect of formononetin against TBI in rats via suppressing inflammatory reaction in cortical neurons. Biomed. Pharm. 2018, 106, 349–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.W.; Hou, C.C.; Zhou, X.; Yu, H.L.; Xi, Y.D.; Ding, J.; Zhao, X.; Xiao, R. Genistein alleviates the mitochondria-targeted DNA damage induced by beta-amyloid peptides 25–35 in C6 glioma cells. Neurochem. Res. 2013, 38, 1315–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Shi, J.X.; Zhang, D.M.; Wang, H.D.; Hang, C.H.; Chen, H.L.; Yin, H.X. Inhibition of hemolysate-induced iNOS and COX-2 expression by genistein through suppression of NF-small ka, CyrillicB activation in primary astrocytes. J. Neurol. Sci. 2009, 278, 91–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valles, S.L.; Dolz-Gaiton, P.; Gambini, J.; Borras, C.; Lloret, A.; Pallardo, F.V.; Vina, J. Estradiol or genistein prevent Alzheimer’s disease-associated inflammation correlating with an increase PPAR gamma expression in cultured astrocytes. Brain Res. 2010, 1312, 138–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DonCarlos, L.L.; Azcoitia, I.; Garcia-Segura, L.M. Neuroprotective actions of selective estrogen receptor modulators. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2009, 34 (Suppl. 1), S113–S122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, D.; Kumar, S.; Narasimhan, B. Estrogen alpha receptor antagonists for the treatment of breast cancer: A review. Chem. Cent. J. 2018, 12, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lien, E.A.; Wester, K.; Lonning, P.E.; Solheim, E.; Ueland, P.M. Distribution of tamoxifen and metabolites into brain tissue and brain metastases in breast cancer patients. Br. J. Cancer 1991, 63, 641–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, C.L.; O’Malley, B.W. Coregulator function: A key to understanding tissue specificity of selective receptor modulators. Endocr. Rev. 2004, 25, 45–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, Y.T.; Wang, C.C.; Leung, P.O.; Lin, K.C.; Chio, C.C.; Hu, C.Y.; Kuo, J.R. Extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 is involved in a tamoxifen neuroprotective effect in a lateral fluid percussion injury rat model. J. Surg. Res. 2014, 189, 106–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, S.W.; Nyam Tt, E.; Hu, C.Y.; Chio, C.C.; Wang, C.C.; Kuo, J.R. Estrogen receptor-alpha is involved in tamoxifen neuroprotective effects in a traumatic brain injury male rat model. World Neurosurg 2018, 112, e278–e287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komm, B.S.; Kharode, Y.P.; Bodine, P.V.; Harris, H.A.; Miller, C.P.; Lyttle, C.R. Bazedoxifene acetate: A selective estrogen receptor modulator with improved selectivity. Endocrinology 2005, 146, 3999–4008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komm, B.S.; Lyttle, C.R. Developing a SERM: Stringent preclinical selection criteria leading to an acceptable candidate (WAY-140424) for clinical evaluation. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2001, 949, 317–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, Y.L.; Wang, X.; Zou, Y.J.; Xing, J.S.; Lou, J.C.; Zou, S.; Ma, B.B.; Ding, Y.; Zhang, B. Bazedoxifene protects cerebral autoregulation after traumatic brain injury and attenuates impairments in blood-brain barrier damage: Involvement of anti-inflammatory pathways by blocking MAPK signaling. Inflamm. Res. 2019, 68, 311–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, J.S.; Sites, C.K. Selective modulation of sex steroids. Ageing Res. Rev. 2002, 1, 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kloosterboer, H.J. Tibolone: A steroid with a tissue-specific mode of action. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2001, 76, 231–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Giraldo, Y.; Forero, D.A.; Echeverria, V.; Garcia-Segura, L.M.; Barreto, G.E. Tibolone attenuates inflammatory response by palmitic acid and preserves mitochondrial membrane potential in astrocytic cells through estrogen receptor beta. Mol. Cell Endocrinol. 2019, 486, 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avila-Rodriguez, M.; Garcia-Segura, L.M.; Hidalgo-Lanussa, O.; Baez, E.; Gonzalez, J.; Barreto, G.E. Tibolone protects astrocytic cells from glucose deprivation through a mechanism involving estrogen receptor beta and the upregulation of neuroglobin expression. Mol. Cell Endocrinol. 2016, 433, 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Acaz-Fonseca, E.; Avila-Rodriguez, M.; Garcia-Segura, L.M.; Barreto, G.E. Regulation of astroglia by gonadal steroid hormones under physiological and pathological conditions. Prog. Neurobiol. 2016, 144, 5–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crespo-Castrillo, A.; Yanguas-Casas, N.; Arevalo, M.A.; Azcoitia, I.; Barreto, G.E.; Garcia-Segura, L.M. The synthetic steroid tibolone decreases reactive gliosis and neuronal death in the cerebral cortex of female mice after a stab wound injury. Mol. Neurobiol. 2018, 55, 8651–8667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeWitt, D.S.; Hawkins, B.E.; Dixon, C.E.; Kochanek, P.M.; Armstead, W.; Bass, C.R.; Bramlett, H.M.; Buki, A.; Dietrich, W.D.; Ferguson, A.R.; et al. Pre-clinical testing of therapies for traumatic brain injury. J. Neurotrauma 2018, 35, 2737–2754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kövesdi, E.; Szabó-Meleg, E.; Abrahám, I.M. The Role of Estradiol in Traumatic Brain Injury: Mechanism and Treatment Potential. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22010011

Kövesdi E, Szabó-Meleg E, Abrahám IM. The Role of Estradiol in Traumatic Brain Injury: Mechanism and Treatment Potential. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2021; 22(1):11. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22010011

Chicago/Turabian StyleKövesdi, Erzsébet, Edina Szabó-Meleg, and István M. Abrahám. 2021. "The Role of Estradiol in Traumatic Brain Injury: Mechanism and Treatment Potential" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 22, no. 1: 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22010011

APA StyleKövesdi, E., Szabó-Meleg, E., & Abrahám, I. M. (2021). The Role of Estradiol in Traumatic Brain Injury: Mechanism and Treatment Potential. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 22(1), 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22010011