Biochemical Markers in Alzheimer’s Disease

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Discussion

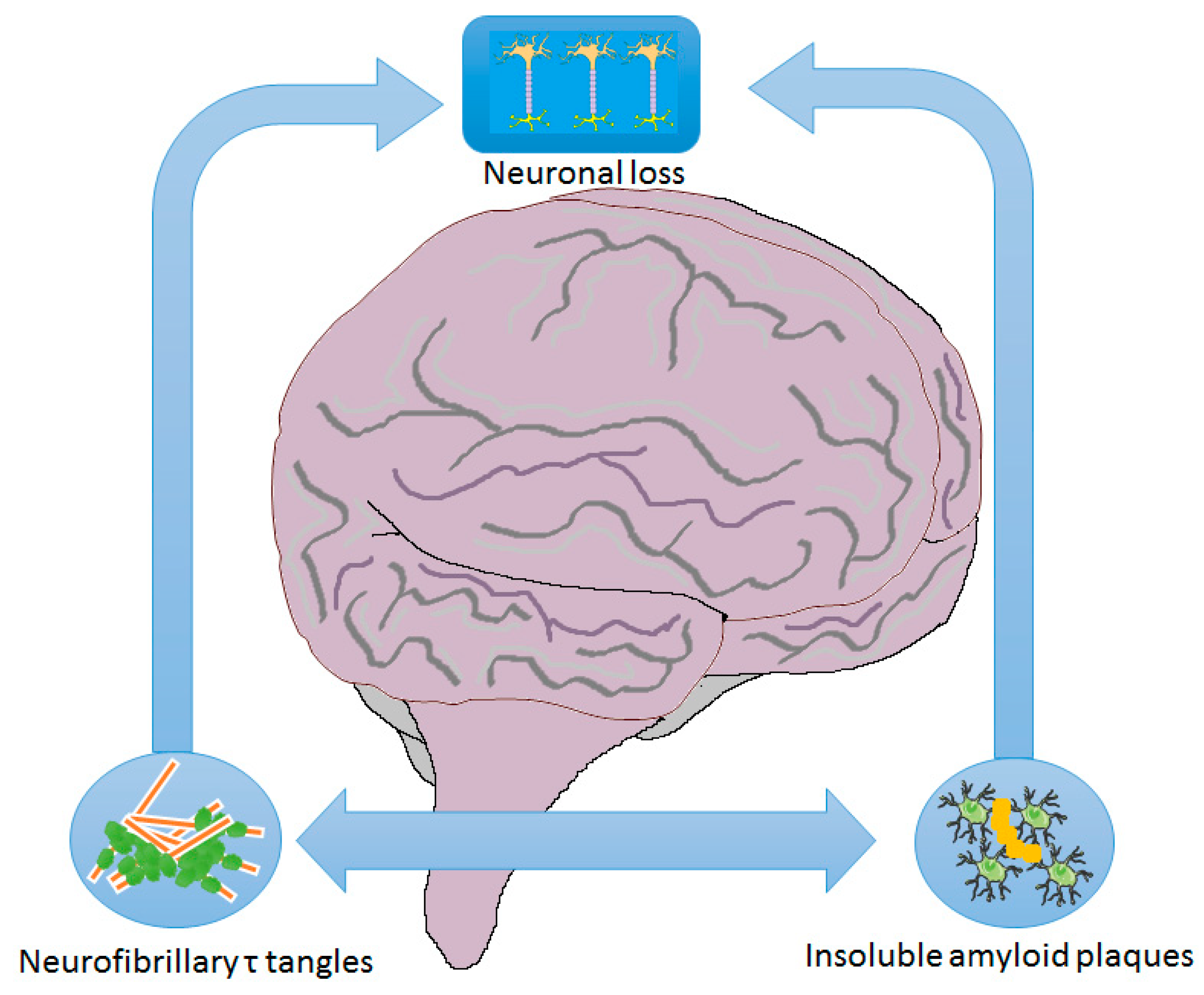

2.1. Mechanisms/Pathophysiology

2.2. Amyloid Hypothesis

2.3. Neurofibrillary Tangles Hypothesis

2.4. Glymphatic System Hypothesis

2.5. Dopaminergic Hypothesis

2.6. Diagnosis of AD

2.7. Promising Biomarkers

3. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alzheimer, A. Uber eine eigenartige Erkrankung der Hirnrinde. Allg Zeitschrift Psychiatr 1907, 146–148. [Google Scholar]

- 2010 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2010, 6, 158–194. [CrossRef]

- Ferri, C.P.; Prince, M.; Brayne, C.; Brodaty, H.; Fratiglioni, L.; Ganguli, M.; Hall, K.; Hasegawa, K.; Hendrie, H.; Huang, Y.; et al. Global prevalence of dementia: A Delphi consensus study. Lancet 2005, 366, 2112–2117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerreiro, R.J.; Gustafson, D.R.; Hardy, J. The genetic architecture of Alzheimer’s disease: Beyond APP, PSENS and APOE. Neurobiol. Aging 2012, 33, 437–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reitz, C.; Mayeux, R. Alzheimer disease: Epidemiology, diagnostic criteria, risk factors and biomarkers. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2014, 88, 640–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, H.K.; Gim, J.-A.; Yeo, S.H.; Kim, H.-S. Integrated late onset Alzheimer’s disease (LOAD) susceptibility genes: Cholesterol metabolism and trafficking perspectives. Gene 2017, 597, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewczuk, P.; Kamrowski-Kruck, H.; Peters, O.; Heuser, I.; Jessen, F.; Popp, J.; Bürger, K.; Hampel, H.; Frölich, L.; Wolf, S.; et al. Soluble amyloid precursor proteins in the cerebrospinal fluid as novel potential biomarkers of Alzheimer’s disease: A multicenter study. Mol. Psychiatry 2010, 15, 138–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isbert, S.; Wagner, K.; Eggert, S.; Schweitzer, A.; Multhaup, G.; Weggen, S.; Kins, S.; Pietrzik, C.U. APP dimer formation is initiated in the endoplasmic reticulumand differs between APP isoforms. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2012, 69, 1353–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Roher, A.; Maarouf, C.; Kokjohn, T.; Whiteside, C.; Macias, M.; Kalback, W.; Sabbagh, M.; Beach, T.; Vassar, R. Molecular Differences and Similarities Between Alzheimer’s Disease and the 5XFAD Transgenic Mouse Model of Amyloidosis. Biochem. Insights 2013, 6, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, M.K.; Borchelt, D.R.; Kim, G.; Thinakaran, G.; Slunt, H.H.; Ratovitski, T.; Martin, L.J.; Kittur, A.; Gandy, S.; Levey, A.I.; et al. Hyperaccumulation of FAD-linked presenilin 1 variants in vivo. Nat. Med. 1997, 3, 756–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, O.; Supnet, C.; Liu, H.; Bezprozvanny, I. Familial Alzheimer’s disease mutations in presenilins: Effects on endoplasmic reticulum calcium homeostasis and correlation with clinical phenotypes. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2010, 21, 781–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cruts, M.; Theuns, J.; Van Broeckhoven, C. Locus-specific mutation databases for neurodegenerative brain diseases. Hum. Mutat. 2012, 33, 1340–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verghese, P.B.; Castellano, J.M.; Garai, K.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, H.; Shah, A.; Bu, G.; Frieden, C.; Holtzman, D.M. ApoE influences amyloid-β (Aβ) clearance despite minimal apoE/Aβ association in physiological conditions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, E1807–E1816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farrer, L.A.; Cupples, L.A.; Haines, J.L.; Hyman, B.; Kukull, W.A.; Mayeux, R.; Myers, R.H.; Pericak-Vance, M.A.; Risch, N.; Van Duijn, C.M. Effects of age, sex, and ethnicity on the association between apolipoprotein E genotype and Alzheimer disease: A meta-analysis. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 1997, 278, 1349–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khachaturian, A.S.; Corcoran, C.D.; Mayer, L.S.; Zandi, P.P.; Breitner, J.C.S. Apolipoprotein E ε4 Count Affects Age at Onset of Alzheimer Disease, but Not Lifetime Susceptibility: The Cache County Study. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2004, 61, 518–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corder, E.H.; Saunders, A.M.; Strittmatter, W.J.; Schmechel, D.E.; Gaskell, P.C.; Small, G.W.; Roses, A.D.; Haines, J.L.; Pericak-Vance, M.A. Gene dose of apolipoprotein E type 4 allele and the risk of Alzheimer’s disease in late onset families. Science 1993, 261, 921–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corder, E.H.; Saunders, A.M.; Risch, N.J.; Strittmatter, W.J.; Schmechel, D.E.; Gaskell, P.C.; Rimmler, J.B.; Locke, P.A.; Conneally, P.M.; Schmader, K.E.; et al. Protective effect of apolipoprotein E type 2 allele for late onset Alzheimer disease. Nat. Genet. 1994, 7, 180–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lashley, T.; Schott, J.M.; Weston, P.; Murray, C.E.; Wellington, H.; Keshavan, A.; Foti, S.C.; Foiani, M.; Toombs, J.; Rohrer, J.D. Molecular biomarkers of Alzheimer’s disease: Progress and prospects. Dis. Model. Mech. 2018, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varghese, M.; Santa-Maria, I.; Ho, L.; Ward, L.; Yemul, S.; Dubner, L.; Ksieak-Reding, H.; Pasinetti, G.M. Extracellular Tau Paired Helical Filaments Differentially Affect Tau Pathogenic Mechanisms in Mitotic and Post-Mitotic Cells: Implications for Mechanisms of Tau Propagation in the Brain. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2016, 54, 477–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molinuevo, J.L.; Ayton, S.; Batrla, R.; Bednar, M.M.; Bittner, T.; Cummings, J.; Fagan, A.M.; Hampel, H.; Mielke, M.M.; Mikulskis, A.; et al. Current state of Alzheimer’s fluid biomarkers. Acta Neuropathol. 2018, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewczuk, P.; Lelental, N.; Lachmann, I.; Holzer, M.; Flach, K.; Brandner, S.; Engelborghs, S.; Teunissen, C.E.; Zetterberg, H.; Molinuevo, J.L.; et al. Non-phosphorylated tau as a potential biomarker of Alzheimer’s Disease: Analytical and diagnostic characterization. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2017, 55, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hugon, J.; Mouton-Liger, F.; Cognat, E.; Dumurgier, J.; Paquet, C. Blood-Based Kinase Assessments in Alzheimer’s Disease. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2018, 10, 338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castro-Alvarez, J.F.; Alejandro Uribe-Arias, S.; Kosik, K.S.; Cardona-Gómez, G.P. Long- and short-term CDK5 knockdown prevents spatial memory dysfunction and tau pathology of triple transgenic Alzheimer’s mice. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2014, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kimura, T.; Tsutsumi, K.; Taoka, M.; Saito, T.; Masuda-Suzukake, M.; Ishiguro, K.; Plattner, F.; Uchida, T.; Isobe, T.; Hasegawa, M.; et al. Isomerase Pin1 stimulates dephosphorylation of Tau protein at cyclin-dependent kinase (Cdk5)-dependent Alzheimer phosphorylation sites. J. Biol. Chem. 2013, 288, 7968–7977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Hall, G.F.; Shea, T.B. Potentiation of tau aggregation by cdk5 and GSK3β. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2011, 26, 355–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morita, T.; Mcclain, S.P.; Batia, L.M.; Pellegrino, M.; Sarah, R.; Kienzler, M.A.; Lyman, K.; Sofie, A.; Olsen, B.; Wong, J.F.; et al. The Glymphatic System–A Beginner’s Guide. Neurochem. Res. 2016, 87, 124–138. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, L.; Nedergaard, M.; Chen, M.J.; Liao, Y.; Deane, R.; Iliff, J.J.; Nicholson, C.; Christensen, D.J.; Kang, H.; Takano, T.; et al. Sleep Drives Metabolite Clearance from the Adult Brain. Science 2013, 342, 373–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iliff, J.J.; Wang, M.; Liao, Y.; Plogg, B.A.; Peng, W.; Gundersen, G.A.; Benveniste, H.; Vates, G.E.; Deane, R.; Goldman, S.A.; et al. A Paravascular Pathway Facilitates CSF Flow Through the Brain Parenchyma and the Clearance of Interstitial Solutes, Including Amyloid. Sci. Transl. Med. 2012, 4, 147ra111-147ra1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iliff, J.J.; Lee, H.; Yu, M.; Feng, T.; Logan, J.; Nedergaard, M.; Benveniste, H.; Wang, M.; Zeppenfeld, D.M.; Venkataraman, A.; et al. A Paravascular Pathway Facilitates CSF Flow Through the Brain Parenchyma and the Clearance of Interstitial Solutes, Including Amyloid β. Sci. Transl. Med. 2015, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikeshima-Kataoka, H. Neuroimmunological implications of AQP4 in astrocytes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeppenfeld, D.M.; Simon, M.; Haswell, J.D.; D’Abreo, D.; Murchison, C.; Quinn, J.F.; Grafe, M.R.; Woltjer, R.L.; Kaye, J.; Iliff, J.J. Association of Perivascular Localization of Aquaporin-4 With Cognition and Alzheimer Disease in Aging Brains. JAMA Neurol. 2017, 74, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mander, B.A.; Winer, J.R.; Jagust, W.J.; Walker, M.P. Sleep: A Novel Mechanistic Pathway, Biomarker, and Treatment Target in the Pathology of Alzheimer’s Disease? Trends Neurosci. 2016, 39, 552–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benveniste, H.; Liu, X.; Koundal, S.; Sanggaard, S.; Lee, H.; Wardlaw, J. The Glymphatic System and Waste Clearance with Brain Aging: A Review. Gerontology 2018, 06519, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murray, A.M.; Weihmueller, F.B.; Marshall, J.F.; Hurtig, H.I.; Gottleib, G.L.; Joyce, J.N. Damage to dopamine systems differs between parkinson’s disease and alzheimer’s disease with parkinsonism. Ann. Neurol. 1995, 37, 300–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, J.M.; Galvin, J.E.; Roe, C.M.; Morris, J.C.; McKeel, D.W. The pathology of the substantia nigra in Alzheimer disease with extrapyramidal signs. Neurology 2005, 64, 1397–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, X.; Kaminga, A.C.; Wen, S.W.; Wu, X.; Acheampong, K.; Liu, A. Dopamine and dopamine receptors in Alzheimer’s disease: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2019, 10, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, G.; Di Lorenzo, F.; Bonnì1, S.B.; Giacobbe, V.; Bozzali, M.; Caltagirone, C.; Martorana, A. Dopaminergic Modulation of Cortical Plasticity in Alzheimer’s Disease Patients. Neuropsychopharmacology 2014, 39, 2654–2661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nobili, A.; Latagliata, E.C.; Viscomi, M.T.; Cavallucci, V.; Cutuli, D.; Giacovazzo, G.; Krashia, P.; Rizzo, F.R.; Marino, R.; Federici, M.; et al. ARTICLE Dopamine neuronal loss contributes to memory and reward dysfunction in a model of Alzheimer’s disease. Nat. Commun. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sperling, R.A.; Aisen, P.S.; Beckett, L.A.; Bennett, D.A.; Craft, S.; Fagan, A.M.; Iwatsubo, T.; Jack, C.R.; Kaye, J.; Montine, T.J.; et al. Toward defining the preclinical stages of Alzheimer’s disease: Recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2011, 7, 280–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKhann, G.M.; Knopman, D.S.; Chertkow, H.; Hyman, B.T.; Jack, C.R.; Kawas, C.H.; Klunk, W.E.; Koroshetz, W.J.; Manly, J.J.; Mayeux, R.; et al. The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease: Recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2011, 7, 263–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubois, B.; Feldman, H.H.; Jacova, C.; Hampel, H.; Molinuevo, J.L.; Blennow, K.; Dekosky, S.T.; Gauthier, S.; Selkoe, D.; Bateman, R.; et al. Advancing research diagnostic criteria for Alzheimer’s disease: The IWG-2 criteria. Lancet Neurol. 2014, 13, 614–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathis, C.A.; Bacskai, B.J.; Kajdasz, S.T.; McLellan, M.E.; Frosch, M.P.; Hyman, B.T.; Holt, D.P.; Wang, Y.; Huang, G.F.; Debnath, M.L.; et al. A lipophilic thioflavin-T derivative for positron emission tomography (PET) imaging of amyloid in brain. Bioorganic Med. Chem. Lett. 2002, 12, 295–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klunk, W.E.; Engler, H.; Nordberg, A.; Wang, Y.; Blomqvist, G.; Holt, D.P.; Bergström, M.; Savitcheva, I.; Huang, G.F.; Estrada, S.; et al. Imaging Brain Amyloid in Alzheimer’s Disease with Pittsburgh Compound-B. Ann. Neurol. 2004, 55, 306–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hort, J.; O’Brien, J.T.; Gainotti, G.; Pirttila, T.; Popescu, B.O.; Rektorova, I.; Sorbi, S.; Scheltens, P. EFNS guidelines for the diagnosis and management of Alzheimer’s disease. Eur. J. Neurol. 2010, 17, 1236–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blennow, K.; Hampel, H.; Weiner, M.; Zetterberg, H. Cerebrospinal fluid and plasma biomarkers in Alzheimer disease. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2010, 6, 131–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiltfang, J.; Esselmann, H.; Smirnov, A.; Bibl, M.; Cepek, L.; Steinacker, P.; Mollenhauer, B.; Buerger, K.; Hampel, H.; Paul, S.; et al. β-amyloid peptides in cerebrospinal fluid of patients with Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. Ann. Neurol. 2003, 54, 263–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sjögren, M.; Gisslén, M.; Vanmechelen, E.; Blennow, K. Low cerebrospinal fluid beta-amyloid 42 in patients with acute bacterial meningitis and normalization after treatment. Neurosci. Lett. 2001, 314, 33–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janelidze, S.; Zetterberg, H.; Mattsson, N.; Palmqvist, S.; Vanderstichele, H.; Lindberg, O.; van Westen, D.; Stomrud, E.; Minthon, L.; Blennow, K.; et al. CSF A β 42/A β 40 and A β 42/A β 38 ratios: Better diagnostic markers of Alzheimer disease. Ann. Clin. Transl. Neurol. 2016, 3, 154–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öst, M.; Nylén, K.; Csajbok, L.; Öhrfelt, A.O.; Tullberg, M.; Wikkelsö, C.; Nellgård, P.; Rosengren, L.; Blennow, K.; Nellgård, B. Initial CSF total tau correlates with 1-year outcome in patients with traumatic brain injury. Neurology 2006, 67, 1600–1604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hesse, C.; Rosengren, L.; Andreasen, N.; Davidsson, P.; Vanderstichele, H.; Vanmechelen, E.; Blennow, K. Transient increase in total tau but not phospho-tau in human cerebrospinal fluid after acute stroke. Neurosci. Lett. 2001, 297, 187–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hampel, H.; Bürger, K.; Pruessner, J.C.; Zinkowski, R.; DeBernardis, J.; Kerkman, D.; Leinsinger, G.; Evans, A.C.; Davies, P.; Möller, H.J.; et al. Correlation of cerebrospinal fluid levels of tau protein phosphorylated at threonine 231 with rates of hippocampal atrophy in Alzheimer disease. Arch. Neurol. 2005, 62, 770–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buerger, K.; Ewers, M.; Pirttilä, T.; Zinkowski, R.; Alafuzoff, I.; Teipel, S.J.; DeBernardis, J.; Kerkman, D.; McCulloch, C.; Soininen, H.; et al. CSF phosphorylated tau protein correlates with neocortical neurofibrillary pathology in Alzheimer’s disease. Brain 2006, 129, 3035–3041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewczuk, P.; Rüdiger, A.E.; Ae, Z.; Ae, J.W.; Kornhuber, J. Neurochemical dementia diagnostics: A simple algorithm for interpretation of the CSF biomarkers. J. Neural Transm. 2009, 116, 1163–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baldeiras, I.; Santana, I.; Leitão, M.J.; Vieira, D.; Duro, D.; Mroczko, B.; Kornhuber, J.; Lewczuk, P. Erlangen Score as a tool to predict progression from mild cognitive impairment to dementia in Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s Res. Ther. 2019, 11, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rasmussen, M.K.; Mestre, H.; Nedergaard, M. The glymphatic pathway in neurological disorders. Lancet Neurol. 2018, 17, 1016–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattsson, N.; Andreasson, U.; Zetterberg, H.; Blennow, K.; Weiner, M.W.; Aisen, P.; Toga, A.W.; Petersen, R.; Jack, C.R.; Jagust, W.; et al. Association of plasma neurofilament light with neurodegeneration in patients with Alzheimer disease. JAMA Neurol. 2017, 74, 557–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaetani, L.; Blennow, K.; Calabresi, P.; Di Filippo, M.; Parnetti, L.; Zetterberg, H. Neurofilament light chain as a biomarker in neurological disorders. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Repress, A.; Deloulme, J.C.; Sensenbrenner, M.; Ben-Ari, Y.; Baudier, J. Neurogranin: Immunocytochemical localization of a brain-specific protein kinase C substrate. J. Neurosci. 1990, 10, 3782–3792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guadaño-Ferraz, A.; Viñuela, A.; Oeding, G.; Bernal, J.; Rausell, E. RC3/neurogranin is expressed in pyramidal neurons of motor and somatosensory cortex in normal and denervated monkeys. J. Comp. Neurol. 2005, 493, 554–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wellington, H.; Paterson, R.W.; Portelius, E.; Törnqvist, U.; Magdalinou, N.; Fox, N.C.; Blennow, K.; Schott, J.M.; Zetterberg, H. Increased CSF neurogranin concentration is specific to Alzheimer disease. Neurology 2016, 86, 829–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Italiani, P.; Puxeddu, I.; Napoletano, S.; Scala, E.; Melillo, D.; Manocchio, S.; Angiolillo, A.; Migliorini, P.; Boraschi, D.; Vitale, E.; et al. Circulating levels of IL-1 family cytokines and receptors in Alzheimer’s disease: New markers of disease progression? J. Neuroinflammation 2018, 15, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dursun, E.; Gezen-Ak, D.; Hanağasi, H.; Bilgiç, B.; Lohmann, E.; Ertan, S.; Atasoy, I.L.; Alaylioğlu, M.; Araz, Ö.S.; Önal, B.; et al. The interleukin 1 alpha, interleukin 1 beta, interleukin 6 and alpha-2-macroglobulin serum levels in patients with early or late onset Alzheimer’s disease, mild cognitive impairment or Parkinson’s disease. J. Neuroimmunol. 2015, 283, 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rocha, N.P.; Teixeira, A.L.; Coelho, F.M.; Caramelli, P.; Guimarães, H.C.; Barbosa, I.G.; da Silva, T.A.; Mukhamedyarov, M.A.; Zefirov, A.L.; Rizvanov, A.A.; et al. Peripheral blood mono-nuclear cells derived from Alzheimer’s disease patients show elevated baseline levels of secreted cytokines but resist stimulation with β-amyloid peptide. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 2012, 49, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forlenza, O.V.; Diniz, B.S.; Talib, L.L.; Mendonça, V.A.; Ojopi, E.B.; Gattaz, W.F.; Teixeira, A.L. Increased serum IL-1beta level in Alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment. Dement. Geriatr. Cogn. Disord. 2009, 28, 507–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Miller, R.G.; Madison, C.; Jin, X.; Honrada, R.; Harris, W.; Katz, J.; Forshew, D.A.; McGrath, M.S. Systemic immune system alterations in early stages of Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neuroimmunol. 2013, 256, 38–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galimberti, D.; Schoonenboom, N.; Scarpini, E.; Scheltens, P. Chemokines in serum and cerebrospinal fluid of Alzheimer’s disease patients. Ann. Neurol. 2003, 53, 547–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsadany, M.A.; Shehata, H.H.; Mohamad, M.I.; Mahfouz, R.G. Histone deacetylases enzyme, copper, and IL-8 levels in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Am. J. Alzheimers. Dis. Other Demen. 2013, 28, 54–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.S.; Chung, J.H.; Choi, T.K.; Suh, S.Y.; Oh, B.H.; Hong, C.H. Peripheral Cytokines and Chemokines in Alzheimer’s Disease. Dement. Geriatr. Cogn. Disord. 2009, 28, 281–287. [Google Scholar]

- Tripathy, D.; Thirumangalakudi, L.; Grammas, P. RANTES upregulation in the Alzheimer’s disease brain: A possible neuroprotective role. Neurobiol. Aging 2010, 31, 8–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laske, C.; Stellos, K.; Eschweiler, G.W.; Leyhe, T.; Gawaz, M. Decreased CXCL12 (SDF-1) plasma levels in early Alzheimer’s disease: A contribution to a deficient hematopoietic brain support? J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2008, 15, 83–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.S.; Lim, H.K.; Lee, J.Y.; Kim, D.J.; Park, S.; Lee, C.; Lee, C.U. Changes in the levels of plasma soluble fractalkine in patients with mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease. Neurosci. Lett. 2008, 436, 196–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murray, C.J.L.; Mokdad, A.H.; Ballestros, K.; Echko, M.; Glenn, S.; Olsen, H.E.; Mullany, E.; Lee, A.; Khan, A.R.; Ahmadi, A.; et al. The state of US health, 1990-2016: Burden of diseases, injuries, and risk factors among US states. JAMA - J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2018, 319, 1444–1472. [Google Scholar]

| Sample | Protein | AD vs. Control | MMSE | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CSF | Neurogranin | ↑ (NA) | AD (median) 21 (17–25) HC (median) 30 (29–30) | [60] |

| CSF | CCL2 | ↑ (EA) | AD (mean) (24.5 ± 2.1) | [65] |

| CSF | CXCL8 | ↑ (NA) | NA | [66] |

| CSF | CXCL10 | ↑ (NA) | NA | [66] |

| CSF | CXCL12 | ↑ (EA) | AD (mean) (18.9 ± 4.1) | [70] |

| Serum | CXCL12 | ↑ (NA) | AD (mean) (23.6 ± 1.6) CTRL (mean) (28.4 ± 1.6) | [70] |

| Serum | NFL | ↑ (NA) | *AD (mean) (23.2 ± 2.1) *CTRL (mean) (29.1 ± 1.0) | [56,57] |

| Serum | CCL5 | ↓ (NA) | NA | [69] |

| Serum | CX3CL1 | ↓ (NA) | AD (mean) (15.3 ± 3.6) CTRL (mean) (27.3 ± 1.0) | [71] |

| Whole Blood | CXCL9 | ↑ (NA) | NA | [68] |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rabbito, A.; Dulewicz, M.; Kulczyńska-Przybik, A.; Mroczko, B. Biochemical Markers in Alzheimer’s Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 1989. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21061989

Rabbito A, Dulewicz M, Kulczyńska-Przybik A, Mroczko B. Biochemical Markers in Alzheimer’s Disease. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2020; 21(6):1989. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21061989

Chicago/Turabian StyleRabbito, Alessandro, Maciej Dulewicz, Agnieszka Kulczyńska-Przybik, and Barbara Mroczko. 2020. "Biochemical Markers in Alzheimer’s Disease" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 21, no. 6: 1989. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21061989

APA StyleRabbito, A., Dulewicz, M., Kulczyńska-Przybik, A., & Mroczko, B. (2020). Biochemical Markers in Alzheimer’s Disease. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 21(6), 1989. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21061989