Granulosa-Lutein Cell Sirtuin Gene Expression Profiles Differ between Normal Donors and Infertile Women

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Descriptive Statistics and Clinical Variables

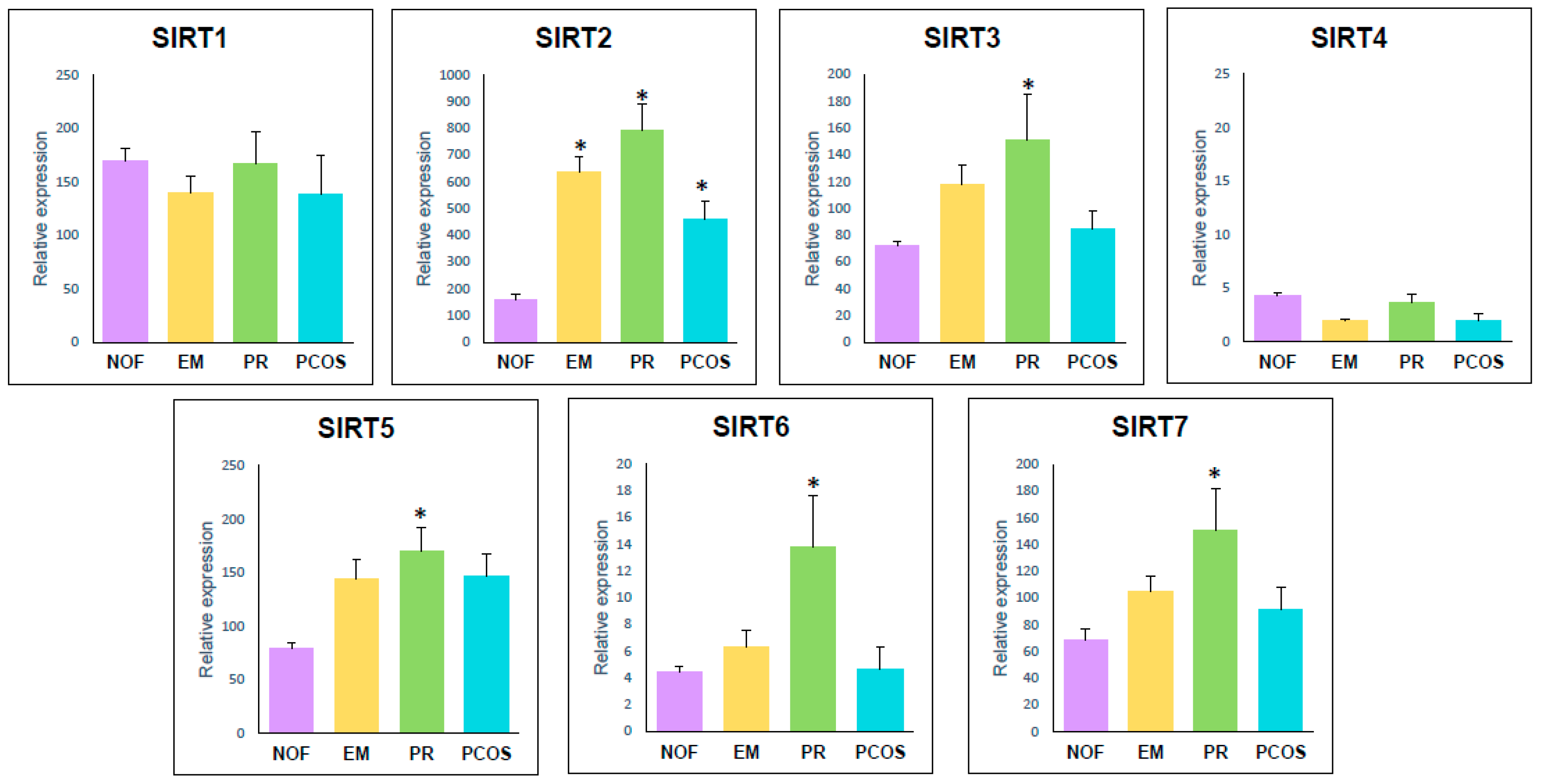

2.2. Sirtuin Gene Expression

2.2.1. Study 1: Sirtuin Gene Expression Level and Correlations with Age and IVF Parameters in Women with No Ovarian Factor

2.2.2. Study 2: Correlations between Sirtuin Gene Expression and IVF Parameters in Women with Different Infertility Diagnosis compared to NOF.

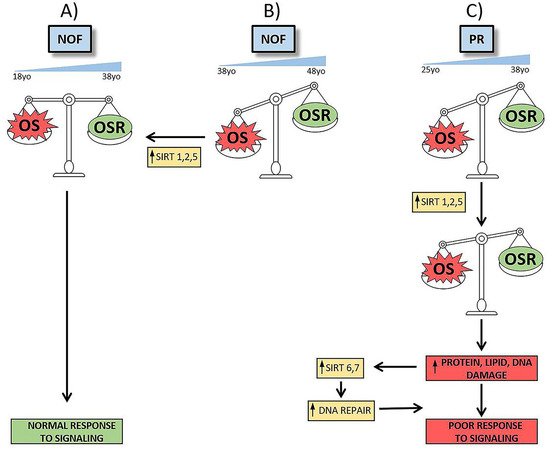

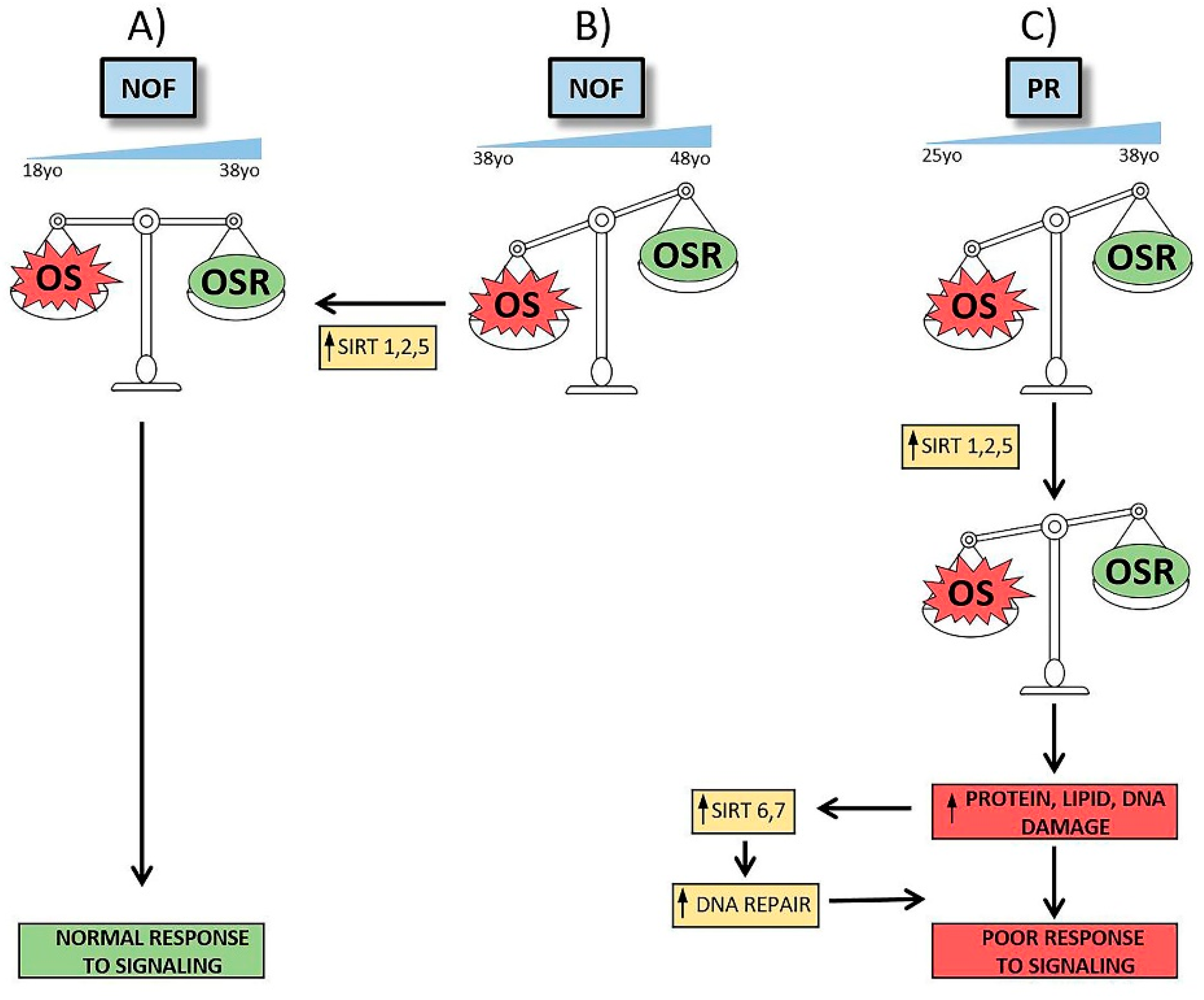

3. Discussion

3.1. These Are Novel Findings Regarding the Possible Role of the Sirtuin Gene Family in Reproductive Failure

3.2. These Findings Have Implications for Ovarian Aging.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Patients

4.1.1. Study 1: Women with No Ovarian Factor

4.1.2. Study 2: Women with Different Infertility Diagnosis Compared to NOF

4.2. Ovulation Induction and Intracytoplasmic Sperm Injection (ICSI)

4.3. Isolation of hGL Cells

4.4. Extraction of RNA

4.5. Synthesis of Complementary DNA

4.6. Quantitative Reverse Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction

4.7. Statistical Analysis

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Days | Total number of days of stimulation |

| FF | Follicular fluid |

| FSH | Follicle stimulating hormone |

| hCG | Human chorionic gonadotropin |

| hGL | Human granulosa-lutein cells |

| hMG | Human menopausal gonadotropins |

| ICSI | Intracytoplasmic sperm injection |

| IVF | In vitro fertilization |

| LH | Luteinizing hormone |

| OD | Oocyte donors |

| NOF | Women with no ovarian factor |

| PCOS | Polycystic ovarian syndrome |

| Peak E2 | Estradiol concentration on the last day of stimulation |

| PR | Poor responders |

| rFSH | Recombinant follicle stimulating hormone |

| rLH | Recombinant luteinizing hormone |

| SIRT | Sirtuin |

| UI | International unit |

| ≥40 yo | Women ≥40 years old with tubal or male factor and no ovarian factor |

References

- Morris, B.J. Seven sirtuins for seven deadly diseases of aging. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2013, 56, 133–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schemies, J.; Uciechowska, U.; Sippl, W.; Jung, M. NAD (+) -dependent histone deacetylases (sirtuins) as novel therapeutic targets. Med. Res. Rev. 2010, 30, 861–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van de Ven, R.A.H.; Santos, D.; Haigis, M.C. Mitochondrial Sirtuins and Molecular Mechanisms of Aging. Trends Mol. Med. 2017, 23, 320–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roessler, C.; Tuting, C.; Meleshin, M.; Steegborn, C.; Schutkowski, M. A Novel Continuous Assay for the Deacylase Sirtuin 5 and Other Deacetylases. J. Med. Chem. 2015, 58, 7217–7223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alageel, A.; Tomasi, J.; Tersigni, C.; Brietzke, E.; Zuckerman, H.; Subramaniapillai, M.; Lee, Y.; Iacobucci, M.; Rosenblat, J.D.; Mansur, R.B.; et al. Evidence supporting a mechanistic role of sirtuins in mood and metabolic disorders. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2018, 86, 95–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mei, Z.; Zhang, X.; Yi, J.; Huang, J.; He, J.; Tao, Y. Sirtuins in metabolism, DNA repair and cancer. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2016, 35, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parodi-Rullan, R.M.; Chapa-Dubocq, X.R.; Javadov, S. Acetylation of Mitochondrial Proteins in the Heart: The Role of SIRT3. Front. Physiol. 2018, 9, 1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinho, A.V.; Mawson, A.; Gill, A.; Arshi, M.; Warmerdam, M.; Giry-Laterriere, M.; Eling, N.; Lie, T.; Kuster, E.; Camargo, S.; et al. Sirtuin 1 stimulates the proliferation and the expression of glycolysis genes in pancreatic neoplastic lesions. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 74768–74778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michishita, E.; Park, J.Y.; Burneskis, J.M.; Barrett, J.C.; Horikawa, I. Evolutionarily conserved and nonconserved cellular localizations and functions of human SIRT proteins. Mol. Biol. Cell 2005, 16, 4623–4635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanno, M.; Sakamoto, J.; Miura, T.; Shimamoto, K.; Horio, Y. Nucleocytoplasmic shuttling of the NAD+-dependent histone deacetylase SIRT1. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 6823–6832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeung, F.; Hoberg, J.E.; Ramsey, C.S.; Keller, M.D.; Jones, D.R.; Frye, R.A.; Mayo, M.W. Modulation of NF-kappaB-dependent transcription and cell survival by the SIRT1 deacetylase. EMBO J. 2004, 23, 2369–2380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Lowry, S.F.; Guarente, L.; Haimovich, B. Roles of SIRT1 in the acute and restorative phases following induction of inflammation. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 41391–41401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tran, D.; Bergholz, J.; Zhang, H.; He, H.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Q.; Kirkland, J.L.; Xiao, Z.X. Insulin-like growth factor-1 regulates the SIRT1-p53 pathway in cellular senescence. Aging Cell 2014, 13, 669–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaziri, H.; Dessain, S.K.; Ng, E.E.; Imai, S.I.; Frye, R.A.; Pandita, T.K.; Guarente, L.; Weinberg, R.A. hSIR2 (SIRT1) functions as an NAD-dependent p53 deacetylase. Cell 2001, 107, 149–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picard, F.; Kurtev, M.; Chung, N.; Topark-Ngarm, A.; Senawong, T.; De Machado, O.R.; Leid, M.; McBurney, M.W.; Guarente, L. Sirt1 promotes fat mobilization in white adipocytes by repressing PPAR-gamma. Nature 2004, 429, 771–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burnett, C.; Valentini, S.; Cabreiro, F.; Goss, M.; Somogyvari, M.; Piper, M.D.; Hoddinott, M.; Sutphin, G.L.; Leko, V.; McElwee, J.J.; et al. Absence of effects of Sir2 overexpression on lifespan in C. elegans and Drosophila. Nature 2011, 477, 482–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, H.; Wada-Hiraike, O.; Hirano, M.; Kawamura, Y.; Sakurabashi, A.; Shirane, A.; Morita, Y.; Isono, W.; Oishi, H.; Koga, K.; et al. SIRT3 positively regulates the expression of folliculogenesis- and luteinization-related genes and progesterone secretion by manipulating oxidative stress in human luteinized granulosa cells. Endocrinology 2014, 155, 3079–3087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, F.; Zhao, W.; Ren, S.; Fu, Y.; Fang, X.; Wang, X.; Li, B. Roles of SIRT1 in granulosa cell apoptosis during the process of follicular atresia in porcine ovary. Anim. Reprod. Sci. 2014, 151, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.M.; Li, L.; Xu, J.J.; Wang, N.; Liu, W.J.; Lin, X.H.; Fu, Y.C.; Luo, L.L. Rapamycin preserves the follicle pool reserve and prolongs the ovarian lifespan of female rats via modulating mTOR activation and sirtuin expression. Gene 2013, 523, 82–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, W.W.; Wu, B.; Liu, W.R. Sirtuins 1 and 2 Are Universal Histone Deacetylases. ACS Chem. Biol. 2016, 11, 792–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skoge, R.H.; Dolle, C.; Ziegler, M. Regulation of SIRT2-dependent alpha-tubulin deacetylation by cellular NAD levels. DNA Repair 2014, 23, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoffmann, G.; Breitenbucher, F.; Schuler, M.; Ehrenhofer-Murray, A.E. A novel sirtuin 2 (SIRT2) inhibitor with p53-dependent pro-apoptotic activity in non-small cell lung cancer. J. Biol. Chem. 2014, 289, 5208–5216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, F.; Nguyen, M.; Qin, F.X.; Tong, Q. SIRT2 deacetylates FOXO3a in response to oxidative stress and caloric restriction. Aging Cell 2007, 6, 505–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, F.; Chan, C.H.; Chen, K.; Guan, X.; Lin, H.K.; Tong, Q. Deacetylation of FOXO3 by SIRT1 or SIRT2 leads to Skp2-mediated FOXO3 ubiquitination and degradation. Oncogene 2012, 31, 1546–1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, B.H.; Kim, H.S.; Song, S.; Lee, I.H.; Liu, J.; Vassilopoulos, A.; Deng, C.X.; Finkel, T. A role for the mitochondrial deacetylase Sirt3 in regulating energy homeostasis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 14447–14452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rardin, M.J.; Newman, J.C.; Held, J.M.; Cusack, M.P.; Sorensen, D.J.; Li, B.; Schilling, B.; Mooney, S.D.; Kahn, C.R.; Verdin, E.; et al. Label-free quantitative proteomics of the lysine acetylome in mitochondria identifies substrates of SIRT3 in metabolic pathways. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 6601–6606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhazzazi, T.Y.; Kamarajan, P.; Xu, Y.; Ai, T.; Chen, L.; Verdin, E.; Kapila, Y.L. A Novel Sirtuin-3 Inhibitor, LC-0296, Inhibits Cell Survival and Proliferation, and Promotes Apoptosis of Head and Neck Cancer Cells. Anticancer Res. 2016, 36, 49–60. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Zhang, J.; Lin, Y.; Lei, Q.; Guan, K.L.; Zhao, S.; Xiong, Y. Tumour suppressor SIRT3 deacetylates and activates manganese superoxide dismutase to scavenge ROS. EMBO Rep. 2011, 12, 534–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonnell, E.; Peterson, B.S.; Bomze, H.M.; Hirschey, M.D. SIRT3 regulates progression and development of diseases of aging. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2015, 26, 486–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di, E.G.; Falone, S.; Vitti, M.; D’Alessandro, A.M.; Vento, M.; Di, P.C.; Amicarelli, F.; Tatone, C. SIRT1 signalling protects mouse oocytes against oxidative stress and is deregulated during aging. Hum. Reprod. 2014, 29, 2006–2017. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, M.; Yin, Y.; Ye, X.; Zeng, M.; Zhao, Q.; Keefe, D.L.; Liu, L. Resveratrol protects against age-associated infertility in mice. Hum. Reprod. 2013, 28, 707–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pacella-Inc, L.; Zander-Fox, D.L.; Lan, M. Mitochondrial SIRT3 and its target glutamate dehydrogenase are altered in follicular cells of women with reduced ovarian reserve or advanced maternal age. Hum. Reprod. 2014, 29, 1490–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laurent, G.; German, N.J.; Saha, A.K.; de Boer, V.C.; Davies, M.; Koves, T.R.; Dephoure, N.; Fischer, F.; Boanca, G.; Vaitheesvaran, B.; et al. SIRT4 coordinates the balance between lipid synthesis and catabolism by repressing malonyl CoA decarboxylase. Mol. Cell 2013, 50, 686–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nasrin, N.; Wu, X.; Fortier, E.; Feng, Y.; Bare, O.C.; Chen, S.; Ren, X.; Wu, Z.; Streeper, R.S.; Bordone, L. SIRT4 regulates fatty acid oxidation mitochondrial gene expression in liver muscle cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 31995–32002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haigis, M.C.; Mostoslavsky, R.; Haigis, K.M.; Fahie, K.; Christodoulou, D.C.; Murphy, A.J.; Valenzuela, D.M.; Yancopoulos, G.D.; Karow, M.; Blander, G.; et al. SIRT4 inhibits glutamate dehydrogenase and opposes the effects of calorie restriction in pancreatic beta cells. Cell 2006, 126, 941–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schlicker, C.; Gertz, M.; Papatheodorou, P.; Kachholz, B.; Becker, C.F.; Steegborn, C. Substrates and regulation mechanisms for the human mitochondrial sirtuins Sirt3 and Sirt5. J. Mol. Biol. 2008, 382, 790–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gertz, M.; Steegborn, C. Function and regulation of the mitochondrial sirtuin isoform Sirt5 in Mammalia. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2010, 1804, 1658–1665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakagawa, T.; Guarente, L. Urea cycle regulation by mitochondrial sirtuin, SIRT5. Aging 2009, 1, 578–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Wang, F.; Sun, R.; Chen, X.; Zhang, M.; Xu, Q.; Wang, Y.; Wang, S.; Xiong, Y.; Guan, K.L.; et al. SIRT5 promotes IDH2 desuccinylation and G6PD deglutarylation to enhance cellular antioxidant defense. EMBO Rep. 2016, 17, 811–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacella-Inc, L.; Zander-Fox, D.L.; Lane, M. Mitochondrial SIRT5 is present in follicular cells and is altered by reduced ovarian reserve and advanced maternal age. Reprod. Fertil. Dev. 2014, 26, 1072–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cea, M.; Cagnetta, A.; Adamia, S.; Acharya, C.; Tai, Y.T.; Fulciniti, M.; Ohguchi, H.; Munshi, A.; Acharya, P.; Bhasin, M.K.; et al. Evidence for a role of the histone deacetylase SIRT6 in DNA damage response of multiple myeloma cells. Blood 2016, 127, 1138–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawahara, T.L.; Rapicavoli, N.A.; Wu, A.R.; Qu, K.; Quake, S.R.; Chang, H.Y. Dynamic chromatin localization of Sirt6 shapes stress- and aging-related transcriptional networks. PLoS Genet. 2011, 7, e1002153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCord, R.A.; Michishita, E.; Hong, T.; Berber, E.; Boxer, L.D.; Kusumoto, R.; Guan, S.; Shi, X.; Gozani, O.; Burlingame, A.L.; et al. SIRT6 stabilizes DNA-dependent protein kinase at chromatin for DNA double-strand break repair. Aging 2009, 1, 109–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagai, K.; Matsushita, T.; Matsuzaki, T.; Takayama, K.; Matsumoto, T.; Kuroda, R.; Kurosaka, M. Depletion of SIRT6 causes cellular senescence, DNA damage, and telomere dysfunction in human chondrocytes. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2015, 23, 1412–1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanfi, Y.; Naiman, S.; Amir, G.; Peshti, V.; Zinman, G.; Nahum, L.; Bar-Joseph, Z.; Cohen, H.Y. The sirtuin SIRT6 regulates lifespan in male mice. Nature 2012, 483, 218–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ford, E.; Voit, R.; Liszt, G.; Magin, C.; Grummt, I.; Guarente, L. Mammalian Sir2 homolog SIRT7 is an activator of RNA polymerase I transcription. Genes Dev. 2006, 20, 1075–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grob, A.; Roussel, P.; Wright, J.E.; McStay, B.; Hernandez-Verdun, D.; Sirri, V. Involvement of SIRT7 in resumption of rDNA transcription at the exit from mitosis. J. Cell Sci. 2009, 122, 489–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Percipalle, P.; Fomproix, N.; Cavellan, E.; Voit, R.; Reimer, G.; Kruger, T.; Thyberg, J.; Scheer, U.; Grummt, I.; Farrants, A.K. The chromatin remodelling complex WSTF-SNF2h interacts with nuclear myosin 1 and has a role in RNA polymerase I transcription. EMBO Rep. 2006, 7, 525–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubbi, M.E.; Hu, H.; Kshitiz Gilkes, D.M.; Semenza, G.L. Sirtuin-7 inhibits the activity of hypoxia-inducible factors. J. Biol. Chem. 2013, 288, 20768–20775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiran, S.; Oddi, V.; Ramakrishna, G. Sirtuin 7 promotes cellular survival following genomic stress by attenuation of DNA damage, SAPK activation and p53 response. Exp. Cell Res. 2015, 331, 123–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, J.; He, M.; Liu, Y.; Paredes, S.; Villanova, L.; Brown, K.; Qiu, X.; Nabavi, N.; Mohrin, M.; Wojnoonski, K.; et al. SIRT7 represses Myc activity to suppress ER stress and prevent fatty liver disease. Cell Rep. 2013, 5, 654–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferraretti, A.P.; La, M.A.; Fauser, B.C.; Tarlatzis, B.; Nargund, G.; Gianaroli, L. ESHRE consensus on the definition of ‘poor response’ to ovarian stimulation for in vitro fertilization: The Bologna criteria. Hum. Reprod. 2011, 26, 1616–1624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ku, S.Y.; Suh, C.S.; Kim, S.H.; Choi, Y.M.; Kim, J.G.; Moon, S.Y. A pilot study of the use of low dose human menopausal gonadotropin in ovulation induction. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2003, 109, 55–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Otin, C.; Blasco, M.A.; Partridge, L.; Serrano, M.; Kroemer, G. The hallmarks of aging. Cell 2013, 153, 1194–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vijg, J.; Kennedy, B.K. The Essence of Aging. Gerontology 2016, 62, 381–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, D.; Hou, X.; Han, L.; Li, X.; Ge, J.; Wang, Q. Sirt2-BubR1 acetylation pathway mediates the effects of advanced maternal age on oocyte quality. Aging Cell 2018, 17, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatone, C.; Di, E.G.; Barbonetti, A.; Carta, G.; Luciano, A.M.; Falone, S.; Amicarelli, F. Sirtuins in gamete biology and reproductive physiology: Emerging roles and therapeutic potential in female and male infertility. Hum. Reprod. Update 2018, 24, 267–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Hou, X.; Ma, R.; Moley, K.; Schedl, T.; Wang, Q. Sirt2 functions in spindle organization and chromosome alignment in mouse oocyte meiosis. FASEB J. 2014, 28, 1435–1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatone, C.; Di, E.G.; Vitti, M.; Di, C.M.; Santini, S., Jr.; D’Alessandro, A.M.; Falone, S.; Amicarelli, F. Sirtuin Functions in Female Fertility: Possible Role in Oxidative Stress and Aging. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avila, J.; Gonzalez-Fernandez, R.; Rotoli, D.; Hernandez, J.; Palumbo, A. Oxidative Stress in Granulosa-Lutein Cells From In Vitro Fertilization Patients. Reprod. Sci. 2016, 23, 1656–1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Fernandez, R.; Hernandez, J.; Martin-Vasallo, P.; Puopolo, M.; Palumbo, A.; Avila, J. Expression Levels of the Oxidative Stress Response Gene ALDH3A2 in Granulosa-Lutein Cells Are Related to Female Age and Infertility Diagnosis. Reprod. Sci. 2016, 23, 604–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guedouari, H.; Daigle, T.; Scorrano, L.; Hebert-Chatelain, E. Sirtuin 5 protects mitochondria from fragmentation and degradation during starvation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Res. 2017, 1864, 169–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.; Chen, Y.; Tishkoff, D.X.; Peng, C.; Tan, M.; Dai, L.; Xie, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Zwaans, B.M.; Skinner, M.E.; et al. SIRT5-mediated lysine desuccinylation impacts diverse metabolic pathways. Mol. Cell 2013, 50, 919–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Acosta, E.; Peña, O.; Naftolin, F.; Avila, J.; Palumbo, A. Angiotensin II induces apoptosis in human mural granulosa-lutein cells, but not in cumulus cells. Fertil. Steril. 2009, 91, 1984–1989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peña, O.; Palumbo, A.; González-Fernández, R.; Hernández, J.; Naftolin, F.; Avila, J. Expression of angiotensin II type 1 (AT1) and angiotensin II type 2 (AT2) receptors in human granulosa-lutein (GL) cells: Correlation with infertility diagnoses. Fertil. Steril. 2010, 93, 1601–1608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karakaya, C.; Guzeloglu-Kayisli, O.; Uyar, A.; Kallen, A.N.; Babayev, E.; Bozkurt, N.; Unsal, E.; Karabacak, O.; Seli, E. Poor ovarian response in women undergoing in vitro fertilization is associated with altered microRNA expression in cumulus cells. Fertil. Steril. 2015, 103, 1469–1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnik Papler, T.; Vrtačnik Bokal, E.; Prosenc Zmrzljak, U.; Stimpfel, M.; Laganà, A.S.; Ghezzi, F.; Jančar, N. PGR and PTX3 gene expression in cumulus cells from obese and normal weighting women after administration of long-acting recombinant follicle-stimulating hormone for controlled ovarian stimulation. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2019, 299, 863–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snider, A.P.; Wood, J.R. Obesity Induces Ovarian Inflammation and Reduces Oocyte Quality. Reproduction 2019, 158, R79–R90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vazquez, B.N.; Thackray, J.K.; Serrano, L. Sirtuins and DNA damage repair: SIRT7 comes to play. Nucleus 2017, 8, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revised American Society for Reproductive Medicine classification of endometriosis. Fertil. Steril. 1997, 67, 817–821. [CrossRef]

- Revised 2003 consensus on diagnostic criteria and long-term health risks related to polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). Hum. Reprod. 2004, 19, 41–47. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmittgen, T.D.; Livak, K.J. Analyzing real-time PCR data by the comparative C (T) method. Nat. Protoc. 2008, 3, 1101–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Parameters | OD | ≥40 yo | NOF | EM | PR | PCOS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N of patients | 17 | 15 | 24 | 18 | 16 | 16 |

| Age | 22 ± 1 a | 41 ± 1 b | 34 ± 1 c | 36 ± 1 c | 36 ± 1 c | 33 ± 1 c |

| Days | 11 ± 1 a | 11 ± 1 a | 11 ± 1 a | 11 ± 1 a | 11 ± 1 a | 10 ± 1 a |

| rFSH (IU) | 2812 ± 255 a | 5750 ± 560 b | 3199 ± 391 a | 5622 ± 442 b | 6154 ± 397 b | 1723 ± 143 a |

| rLH (IU) | 1081 ± 161 a | 2645 ± 335 b | 1115 ± 13 a | 2606 ± 263 b | 2981 ± 274 b | 430 ± 70 a |

| Peak E2 (pg/mL) | 3171 ± 307 a | 2797 ± 188 a | 3054 ± 230 a | 2763 ± 298 a | 2032 ± 214 a | 2901 ± 321 a |

| Total oocytes | 25 ± 2 a | 13 ± 2 c/d | 17 ± 2 b/c | 9 ± 1 c/d | 6 ± 1 d | 21 ± 2 a/b |

| Mature oocytes | 20 ± 2 a | 11 ± 2 c/d | 13 ± 1 b/c | 8 ± 1 c/d | 5 ± 1 d | 18 ± 2 a/b |

| Study 1 | Study 2 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene | OD | NOF | ≥40 | NOF | EM | PR | PCOS |

| SIRT1 | 225.2 ± 46.0 a | 169.1 ± 11.7 a | 478.3 ± 111.1 b | 169.1 ± 11.7 a | 139.3 ± 16.2 a | 166.4 ± 30.2 a | 138.5 ± 36.4 a |

| SIRT2 | 271.4 ± 36.6 a | 161 ± 16.1 a | 600.1 ± 97.0 b | 161 ± 16.1 a | 637.5 ± 57.1 b/c | 793.0 ± 97.7 b | 460.4 ± 68.5 c |

| SIRT3 | 70.8 ± 8.9 a | 72.1 ± 3.1 a | 115.3 ± 27.6 a | 72.1 ± 3.1 a | 117.7 ± 14.7 a/b | 150.9 ± 34.3 b | 84.3 ± 14.3 a/b |

| SIRT4 | 2.5 ± 0.6 a | 4.3 ± 0.3 a | 2.7 ± 0.9 a | 4.3 ± 0.3 a | 1.9 ± 0.2 a | 3.6 ± 0.9 a | 2.01 ± 0.6 a |

| SIRT5 | 83.2 ±10.5 a | 79.2 ± 4.9 a | 171.6 ± 37.2 b | 79.2 ± 4.9 a | 143.8 ± 18.1 a/b | 169.7 ± 22.2 b | 146.8 ± 20.3 a/b |

| SIRT6 | 3.2 ± 0.7 a | 4.4 ± 0.5 a | 2.5 ± 0.5 a | 4.4 ± 0.5 a | 6.3 ± 1.3 a | 13.8 ± 3.8 b | 4.7 ± 1.6 a |

| SIRT7 | 32.7 ± 7.3 a | 68.6 ± 8.8 a | 66.5 ± 14.5 a | 68.6 ± 8.8 a | 104.9 ± 11.3 a | 151.2 ± 30.8 b | 91.4 ± 17.2 a/b |

| Gene | Oligonucleotide | Sequence (5′→3′) | Tm (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|

| SIRT1 | SIRT1-F | CTATACCCAGAACATAGACACG | 54.1 |

| SIRT1-R | ACAAATCAGGCAAGATGC | 54.5 | |

| SIRT2 | SIRT2-F | CCATCTGTCACTACTTCATGC | 55.8 |

| SIRT2-R | AAGTCCTCCTGTTCCAGC | 55.1 | |

| SIRT3 | SIRT3-F | GCTGGACAGAAGAGATGC | 54.1 |

| SIRT3-R | GTGGATGTCTCCTATGTTACC | 47.6 | |

| SIRT4 | SIRT4-F | CAGATGTCGTTTTCTTCG | 44.4 |

| SIRT4-R | CCAGAGTATACCTGCAAGG | 52.6 | |

| SIRT5 | SIRT5-F | CCCAGAACATCGATGAGC | 55.6 |

| SIRT5-R | GCCACAACTCCACAAGAGG | 57.9 | |

| SIRT6 | SIRT6-F | AGGGACAAACTGGCAGAGC | 60.4 |

| SIRT6-R | TTAGCCACGGTGCAGAGC | 61.1 | |

| SIRT7 | SIRT7-F | GCAGAGCAGACACCATCC | 57.7 |

| SIRT7-R | GTTCACGATGTAAAGCTTCG | 56.1 | |

| β-Actin | ACTB-F | CTTCCTTCCTGGGCATGG | 61.6 |

| ACTB-R | GCCGCCAGACAGCACTGT | 63.7 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

González-Fernández, R.; Martín-Ramírez, R.; Rotoli, D.; Hernández, J.; Naftolin, F.; Martín-Vasallo, P.; Palumbo, A.; Ávila, J. Granulosa-Lutein Cell Sirtuin Gene Expression Profiles Differ between Normal Donors and Infertile Women. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 295. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21010295

González-Fernández R, Martín-Ramírez R, Rotoli D, Hernández J, Naftolin F, Martín-Vasallo P, Palumbo A, Ávila J. Granulosa-Lutein Cell Sirtuin Gene Expression Profiles Differ between Normal Donors and Infertile Women. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2020; 21(1):295. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21010295

Chicago/Turabian StyleGonzález-Fernández, Rebeca, Rita Martín-Ramírez, Deborah Rotoli, Jairo Hernández, Frederick Naftolin, Pablo Martín-Vasallo, Angela Palumbo, and Julio Ávila. 2020. "Granulosa-Lutein Cell Sirtuin Gene Expression Profiles Differ between Normal Donors and Infertile Women" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 21, no. 1: 295. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21010295

APA StyleGonzález-Fernández, R., Martín-Ramírez, R., Rotoli, D., Hernández, J., Naftolin, F., Martín-Vasallo, P., Palumbo, A., & Ávila, J. (2020). Granulosa-Lutein Cell Sirtuin Gene Expression Profiles Differ between Normal Donors and Infertile Women. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 21(1), 295. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21010295