The Role of Proteases in the Virulence of Plant Pathogenic Bacteria

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. General Characterization of the Selected Proteases

2.1. Metalloproteases

2.2. Cysteine Proteases

2.2.1. YopT Family

2.2.2. SUMO Proteases

2.3. Serine Proteases

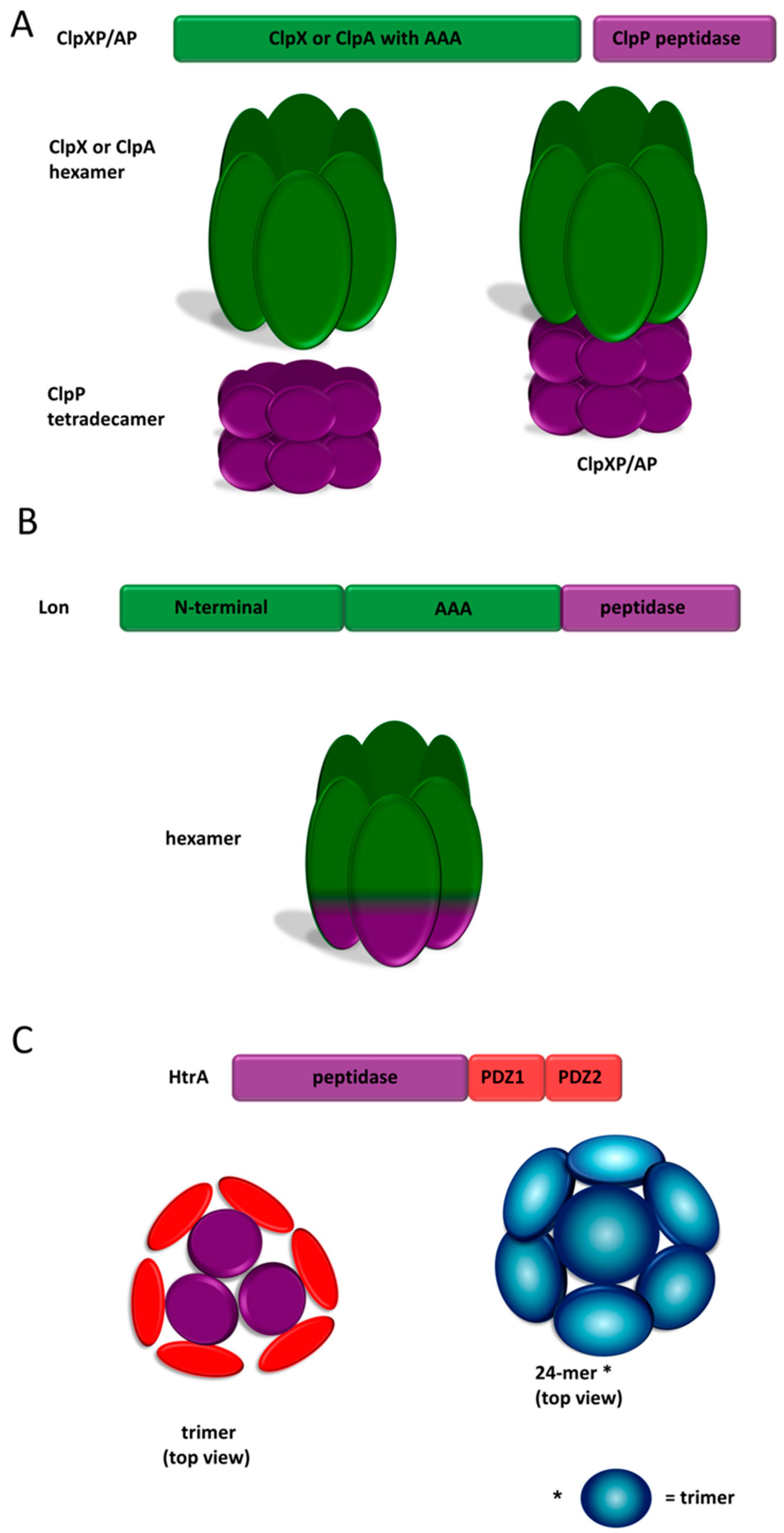

2.3.1. ClpP

2.3.2. Lon

2.3.3. High Temperature Requirement A (HtrA) Proteases

3. Proteases as Direct Virulence Factors

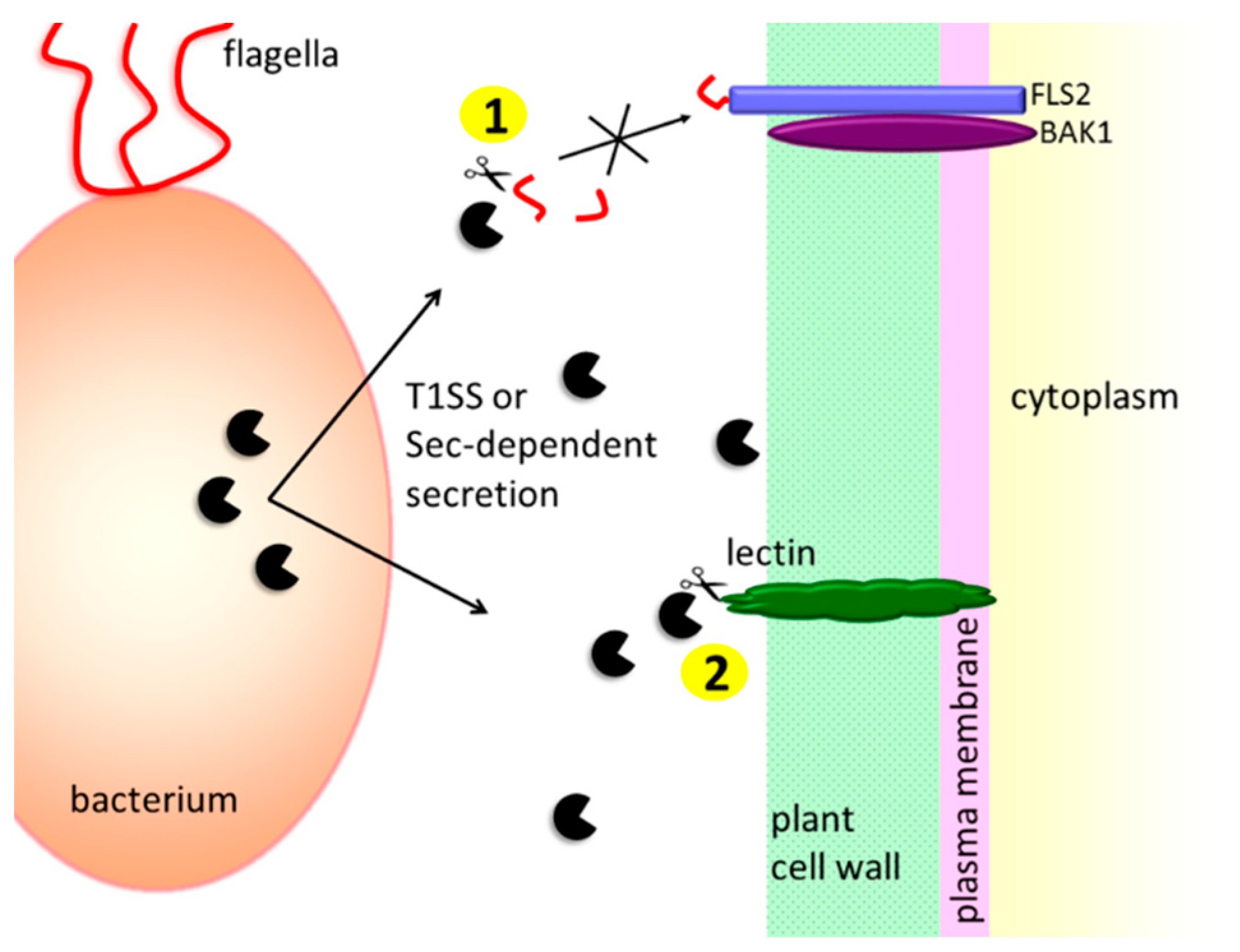

3.1. Extracellular Bacterial Proteases

3.1.1. Protection against the Host’s Extracellular Defense Mechanisms

3.1.2. Contribution to the Plant Cell Wall Degradation

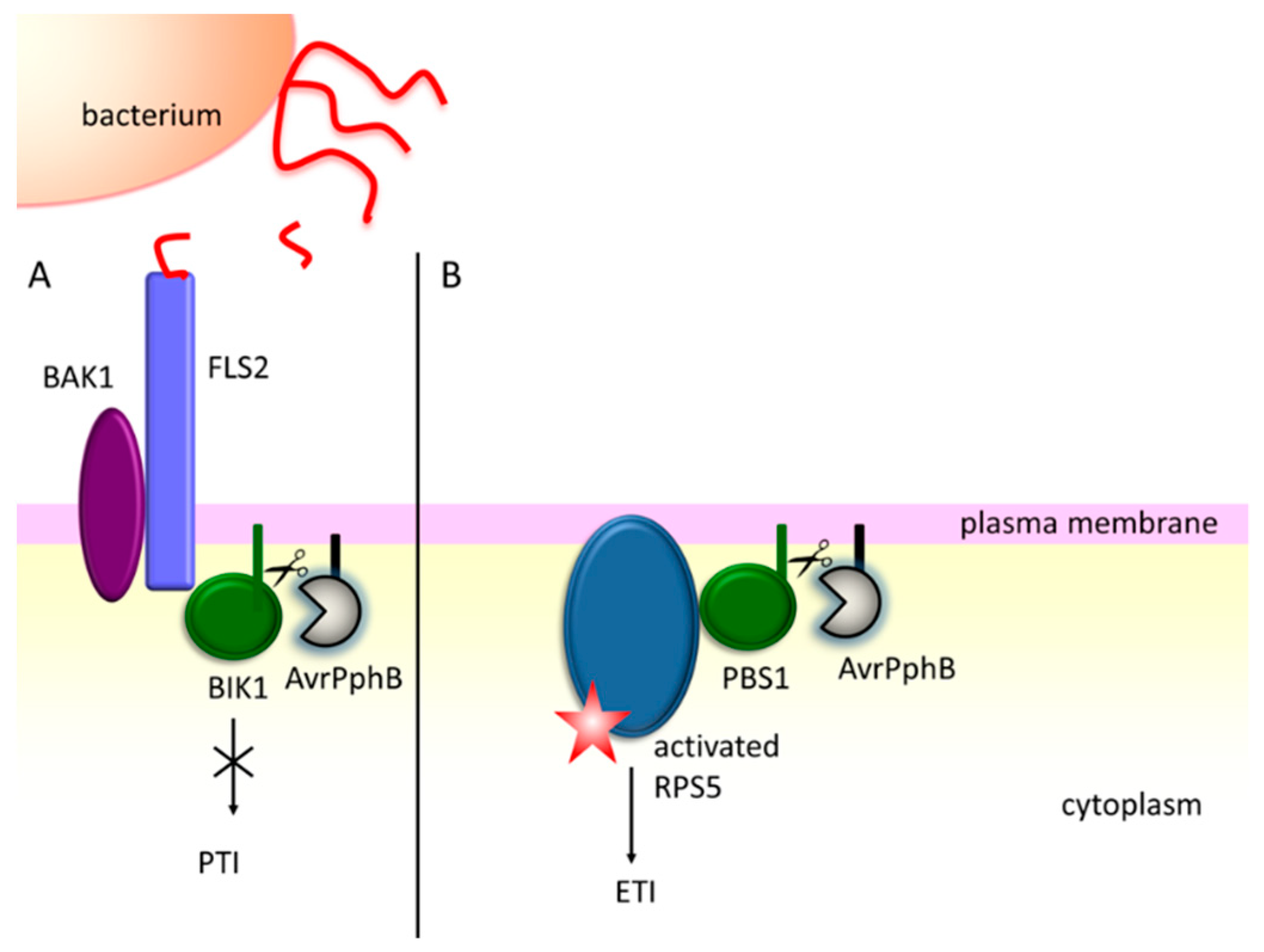

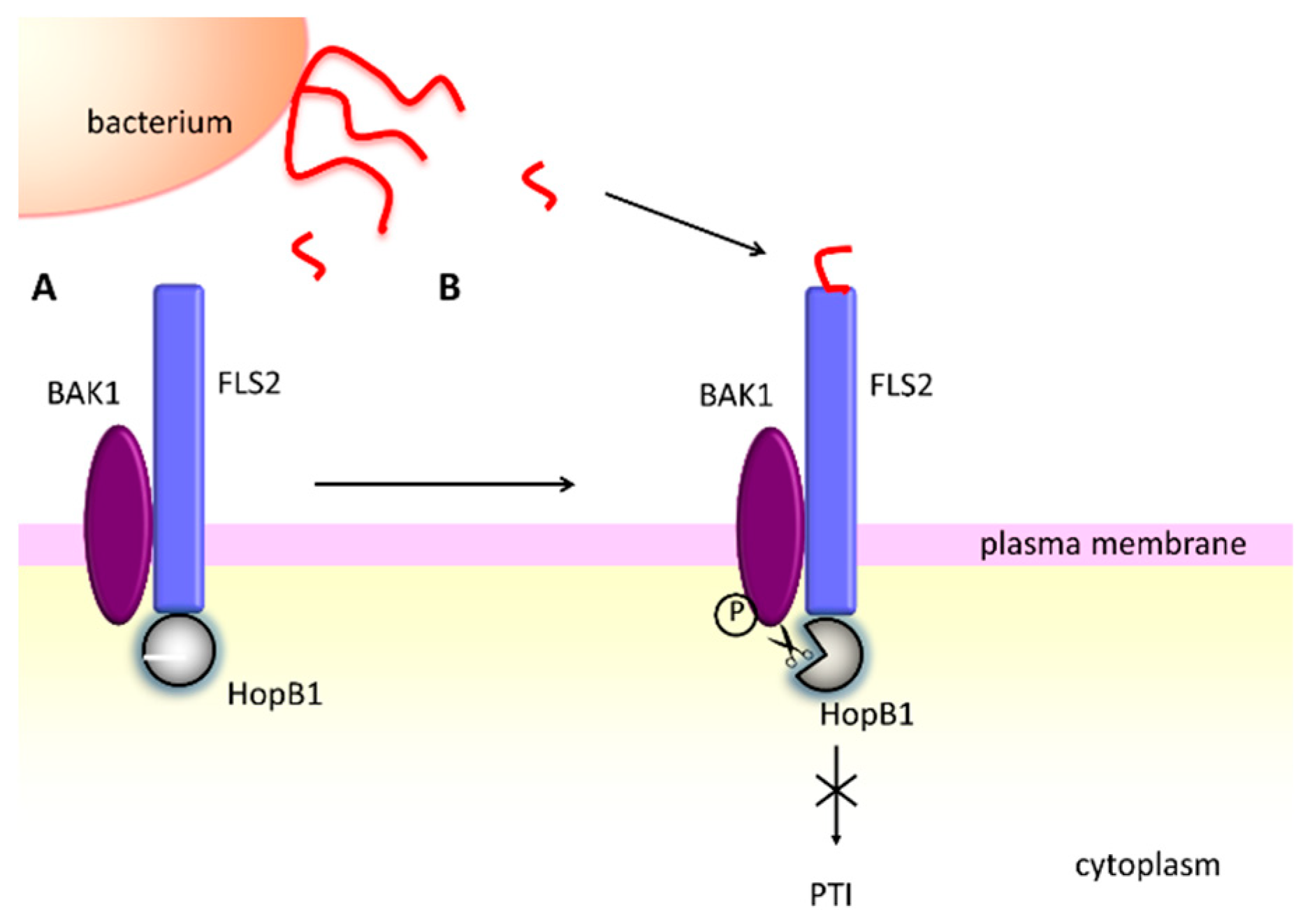

3.2. Effector Proteins Injected into the Host

4. Regulatory Proteolysis

5. Maintenance of Cellular Proteostasis

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AAA+ family of ATPases | ATPases associated with diverse cellular activities |

| AXR | auxin-resistant |

| BAK1 | brassinosteroid insensitive 1-associated kinase 1 |

| BIK1 kinase | botrytis-induced kinase 1 |

| BSA | bovine serum albumin |

| DFP | diisopropylfluorophosphate |

| Dps | DNA-binding protein of starved cells |

| DTT | ditiotreitol |

| ECF | extracytoplasmic function |

| EDTA | (ethylenedinitrilo)tetraacetic acid |

| EF-Tu | elongation factor thermos unstable |

| EGTA | ethylene glycol-bis(2-aminoethylether)-N,N,N’,N’-tetraacetic acid |

| EAR | ERF-associated amphiphilic repression |

| ERF | ethylene response factor |

| ET | ethylene |

| ETI | effector-triggered immunity |

| FLS2 | flagellin sensing 2 |

| HopZ4 | hypersensitivity and pathogenesis-dependent outer protein Z4 |

| HR | hypersensitive response |

| hrc genes | HR and conserved genes |

| Hrp | hypersensitive response and pathogenicity |

| HtrA | high temperature requirement A |

| JA | jasmonic acid |

| JAZs | jasmonate zimdomain proteins |

| MarA | multiple antibiotic resistance activator |

| MKK | mitogen-activated protein kinase kinases |

| MPK | mitogen-activated protein kinase |

| NOI | nitrate-induced |

| NPR1 | Nonexpressor of Pathogenesis-Related1 |

| OEC | oxygen evolving complex |

| PAMPs | pathogen-associated molecular patterns |

| PBS1 | AvrPphB susceptible1 |

| PDZ | post synaptic density protein 95, Drosophila disc large tumor suppressor, and Zonula occludens-1 protein domain |

| Pel | pectate lyase |

| PGA | polygalacturonic acid |

| PRRs | pattern recognition receptors |

| PTI | pattern-triggered immunity |

| PBL1 | PBS-like 1 |

| PS II | photosystem II |

| RPM1 | resistance to Pseudomonas syringae pv. maculicola1 |

| R-protein | resistance (R) protein |

| RLCK | receptor-like cytoplasmic kinase |

| RIN4 | RPM1-interacting protein 4 |

| ROS | reactive oxygen species |

| RsmA | a small RNA-binding protein |

| RpoE | sigma E |

| Rcs | regulator of capsule synthesis |

| RpoS | sigma S |

| RPS5 | resistance to Pseudomonas syringae 5 |

| RPT6 | regulatory particle AAA-ATPase 6 |

| SA | salicylic acid |

| SDS | sodium dodecyl sulfate |

| SERK | somatic embryogenesis receptor like kinase |

| Sox | Sry-related high-mobility-group box |

| sRNAs | small RNAs |

| SsrA | peptide tag encoded by small stable RNA A |

| SspB | stringent starvation protein B |

| SUMO | small ubiquitin-like modifier |

| Tsp | tail-specific protease |

| T1SS | type one secretion system |

| T3SS | type three secretion system |

| ULPs | ubiquitin-like protein proteases |

| UmuD’ | umu: UV mutagenesis |

| wt | wild type |

| Xop | Xanthomonas outer protein |

| Yop | Yersinia outer protein |

References

- Vorholt, J.A. Microbial life in the phyllosphere. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2012, 10, 828–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colwell, R.R. Viable but nonculturable bacteria: A survival strategy. J. Infect. Chemother. 2000, 6, 121–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hueck, C.J. Type III protein secretion systems in bacterial pathogens of animals and plants. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 1998, 62, 379–433. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gasser, B.; Saloheimo, M.; Rinas, U.; Dragosits, M.; Rodríguez-Carmona, E.; Baumann, K.; Giuliani, M.; Parrilli, E.; Branduardi, P.; Lang, C.; et al. Protein folding and conformational stress in microbial cells producing recombinant proteins: A host comparative overview. Microb. Cell Fact. 2008, 7, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gur, E.; Biran, D.; Ron, E.Z. Regulated proteolysis in Gram-negative bacteria—How and when? Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2011, 9, 839–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mansfield, J.; Genin, S.; Magori, S.; Citovsky, V.; Sriariyanum, M.; Ronald, P.; Dow, M.; Verdier, V.; Beer, S.V.; Machado, M.A.; et al. Top 10 plant pathogenic bacteria in molecular plant pathology. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2012, 13, 614–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnold, D.L.; Preston, G.M. Pseudomonas syringae: Enterprising epiphyte and stealthy parasite. Microbiology 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peeters, N.; Guidot, A.; Vailleau, F.; Valls, M. Ralstonia solanacearum, a widespread bacterial plant pathogen in the post-genomic era. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2013, 14, 651–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramoni, S.; Nathoo, N.; Klimov, E.; Yuan, Z.-C. Agrobacterium tumefaciens responses to plant-derived signaling molecules. Front. Plant Sci. 2014, 5, 322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niño-Liu, D.O.; Ronald, P.C.; Bogdanove, A.J. Xanthomonas oryzae pathovars: Model pathogens of a model crop. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2006, 7, 303–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, B.D.; Vicente, J.G.; Manandhar, H.K.; Roberts, S.J. Occurrence and Diversity of Xanthomonas campestris pv. campestris in Vegetable Brassica Fields in Nepal. Plant Dis. 2010, 94, 298–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mhedbi-Hajri, N.; Hajri, A.; Boureau, T.; Darrasse, A.; Durand, K.; Brin, C.; Saux, M.F.-L.; Manceau, C.; Poussier, S.; Pruvost, O.; et al. Evolutionary History of the Plant Pathogenic Bacterium Xanthomonas axonopodis. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e58474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baldi, P.; La Porta, N. Xylella fastidiosa: Host Range and Advance in Molecular Identification Techniques. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denancé, N.; Legendre, B.; Briand, M.; Olivier, V.; de Boisseson, C.; Poliakoff, F.; Jacques, M.-A. Several subspecies and sequence types are associated with the emergence of Xylella fastidiosa in natural settings in France. Plant Pathol. 2017, 66, 1054–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reverchon, S.; Muskhelisvili, G.; Nasser, W. Virulence Program of a Bacterial Plant Pathogen: The Dickeya Model. Prog. Mol. Biol. Transl. Sci. 2016, 142, 51–92. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yishay, M.; Burdman, S.; Valverde, A.; Luzzatto, T.; Ophir, R.; Yedidia, I. Differential pathogenicity and genetic diversity among Pectobacterium carotovorum ssp. carotovorum isolates from monocot and dicot hosts support early genomic divergence within this taxon: Pathogenicity and genetic diversity of Pectobacterium. Environ. Microbiol. 2008, 10, 2746–2759. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rawlings, N.D.; Barrett, A.J.; Thomas, P.D.; Huang, X.; Bateman, A.; Finn, R.D. The MEROPS database of proteolytic enzymes, their substrates and inhibitors in 2017 and a comparison with peptidases in the PANTHER database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, D624–D632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MEROPS—The Peptidase Database. Available online: https://www.ebi.ac.uk/merops/ (accessed on 5 December 2018).

- Culp, E.; Wright, G.D. Bacterial proteases, untapped antimicrobial drug targets. J. Antibiot. 2017, 70, 366–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Supuran, C.T.; Scozzafava, A.; Mastrolorenzo, A. Bacterial proteases: Current therapeutic use and future prospects for the development of new antibiotics. Expert Opin. Ther. Pat. 2001, 11, 221–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pel, M.J.C.; van Dijken, A.J.H.; Bardoel, B.W.; Seidl, M.F.; van der Ent, S.; van Strijp, J.A.G.; Pieterse, C.M.J. Pseudomonas syringae evades host immunity by degrading flagellin monomers with alkaline protease AprA. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 2014, 27, 603–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shevchik, V.E.; Boccara, M.; Vedel, R.; Hugouvieux-Cotte-Pattat, N. Processing of the pectate lyase PelI by extracellular proteases of Erwinia chrysanthemi 3937. Mol. Microbiol. 1998, 29, 1459–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, D.H.; Lim, J.-A.; Lee, J.; Roh, E.; Jung, K.; Choi, M.; Oh, C.; Ryu, S.; Yun, J.; Heu, S. Characterization of genes required for the pathogenicity of Pectobacterium carotovorum subsp. carotovorum Pcc21 in Chinese cabbage. Microbiology 2013, 159, 1487–1496. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Feng, T.; Nyffenegger, C.; Højrup, P.; Vidal-Melgosa, S.; Yan, K.-P.; Fangel, J.U.; Meyer, A.S.; Kirpekar, F.; Willats, W.G.; Mikkelsen, J.D. Characterization of an extensin-modifying metalloprotease: N-terminal processing and substrate cleavage pattern of Pectobacterium carotovorum Prt1. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2014, 98, 10077–10089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dow, J.M.; Fan, M.J.; Newman, M.A.; Daniels, M.J. Differential expression of conserved protease genes in crucifer-attacking pathovars of Xanthomonas campestris. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1993, 59, 3996–4003. [Google Scholar]

- Dow, J.M.; Clarke, B.R.; Milligan, D.E.; Tang, J.L.; Daniels, M.J. Extracellular proteases from Xanthomonas campestris pv. campestris, the black rot pathogen. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1990, 56, 2994–2998. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kyöstiö, S.R.; Cramer, C.L.; Lacy, G.H. Erwinia carotovora subsp. carotovora extracellular protease: Characterization and nucleotide sequence of the gene. J. Bacteriol. 1991, 173, 6537–6546. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Marits, R.; Tshuikina, M.; Pirhonen, M.; Laasik, E.; Mäe, A. Regulation of the expression of prtW::gusA fusions in Erwinia carotovora subsp. carotovora. Microbiology 2002, 148, 835–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marits, R.; Kõiv, V.; Laasik, E.; Mäe, A. Isolation of an extracellular protease gene of Erwinia carotovora subsp. carotovora strain SCC3193 by transposon mutagenesis and the role of protease in phytopathogenicity. Microbiology 1999, 145 Pt 8, 1959–1966. [Google Scholar]

- Wandersman, C.; Delepelaire, P.; Letoffe, S.; Schwartz, M. Characterization of Erwinia chrysanthemi extracellular proteases: Cloning and expression of the protease genes in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 1987, 169, 5046–5053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghigo, J.M.; Wandersman, C. Cloning, nucleotide sequence and characterization of the gene encoding the Erwinia chrysanthemi B374 PrtA metalloprotease: A third metalloprotease secreted via a C-terminal secretion signal. Mol. Gen. Genet. 1992, 236, 135–144. [Google Scholar]

- Delepelaire, P.; Wandersman, C. Protease secretion by Erwinia chrysanthemi. Proteases B and C are synthesized and secreted as zymogens without a signal peptide. J. Biol. Chem. 1989, 264, 9083–9089. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ghigo, J.M.; Wandersman, C. A fourth metalloprotease gene in Erwinia chrysanthemi. Res. Microbiol. 1992, 143, 857–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, F.; Merritt, P.M.; Bao, Z.; Innes, R.W.; Dixon, J.E. A Yersinia effector and a Pseudomonas avirulence protein define a family of cysteine proteases functioning in bacterial pathogenesis. Cell 2002, 109, 575–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petnicki-Ocwieja, T.; Schneider, D.J.; Tam, V.C.; Chancey, S.T.; Shan, L.; Jamir, Y.; Schechter, L.M.; Janes, M.D.; Buell, C.R.; Tang, X.; et al. Genomewide identification of proteins secreted by the Hrp type III protein secretion system of Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato DC3000. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2002, 99, 7652–7657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, R.W.; Athanassopoulos, E.; Tsiamis, G.; Mansfield, J.W.; Sesma, A.; Arnold, D.L.; Gibbon, M.J.; Murillo, J.; Taylor, J.D.; Vivian, A. Identification of a pathogenicity island, which contains genes for virulence and avirulence, on a large native plasmid in the bean pathogen Pseudomonas syringae pathovar phaseolicola. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1999, 96, 10875–10880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cunnac, S.; Occhialini, A.; Barberis, P.; Boucher, C.; Genin, S. Inventory and functional analysis of the large Hrp regulon in Ralstonia solanacearum: Identification of novel effector proteins translocated to plant host cells through the type III secretion system. Mol. Microbiol. 2004, 53, 115–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.; Shao, F.; Innes, R.W.; Dixon, J.E.; Xu, Z. The crystal structure of Pseudomonas avirulence protein AvrPphB: A papain-like fold with a distinct substrate-binding site. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 302–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hotson, A.; Chosed, R.; Shu, H.; Orth, K.; Mudgett, M.B. Xanthomonas type III effector XopD targets SUMO-conjugated proteins in planta. Mol. Microbiol. 2003, 50, 377–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-G.; Taylor, K.W.; Mudgett, M.B. Comparative analysis of the XopD type III secretion (T3S) effector family in plant pathogenic bacteria. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2011, 12, 715–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazan, K. Negative regulation of defence and stress genes by EAR-motif-containing repressors. Trends Plant Sci. 2006, 11, 109–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hay, R.T. SUMO: A history of modification. Mol. Cell 2005, 18, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.-G.; Taylor, K.W.; Hotson, A.; Keegan, M.; Schmelz, E.A.; Mudgett, M.B. XopD SUMO protease affects host transcription, promotes pathogen growth, and delays symptom development in Xanthomonas-infected tomato leaves. Plant Cell 2008, 20, 1915–1929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chosed, R.; Tomchick, D.R.; Brautigam, C.A.; Mukherjee, S.; Negi, V.S.; Machius, M.; Orth, K. Structural analysis of Xanthomonas XopD provides insights into substrate specificity of ubiquitin-like protein proteases. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 6773–6782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, A.Y.H.; Houry, W.A. ClpP: A distinctive family of cylindrical energy-dependent serine proteases. FEBS Lett. 2007, 581, 3749–3757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neuwald, A.F.; Aravind, L.; Spouge, J.L.; Koonin, E.V. AAA+: A class of chaperone-like ATPases associated with the assembly, operation, and disassembly of protein complexes. Genome Res. 1999, 9, 27–43. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mayer, R.J.; Ciechanover, A.J.; Rechsteiner, M. (Eds.) Protein Degradation; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 2005; Volume 2, p. 235. [Google Scholar]

- Olivares, A.O.; Baker, T.A.; Sauer, R.T. Mechanistic insights into bacterial AAA+ proteases and protein-remodelling machines. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2016, 14, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baker, T.A.; Sauer, R.T. ClpXP, an ATP-powered unfolding and protein-degradation machine. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2012, 1823, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottesman, S.; Roche, E.; Zhou, Y.; Sauer, R.T. The ClpXP and ClpAP proteases degrade proteins with carboxy-terminal peptide tails added by the SsrA-tagging system. Genes Dev. 1998, 12, 1338–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flynn, J.M.; Levchenko, I.; Seidel, M.; Wickner, S.H.; Sauer, R.T.; Baker, T.A. Overlapping recognition determinants within the ssrA degradation tag allow modulation of proteolysis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2001, 98, 10584–10589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keiler, K.C.; Waller, P.R.; Sauer, R.T. Role of a peptide tagging system in degradation of proteins synthesized from damaged messenger RNA. Science 1996, 271, 990–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillet, R.; Felden, B. Emerging views on tmRNA-mediated protein tagging and ribosome rescue. Mol. Microbiol. 2001, 42, 879–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dougan, D.A.; Weber-Ban, E.; Bukau, B. Targeted delivery of an ssrA-tagged substrate by the adaptor protein SspB to its cognate AAA+ protein ClpX. Mol. Cell 2003, 12, 373–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tobias, J.W.; Shrader, T.E.; Rocap, G.; Varshavsky, A. The N-end rule in bacteria. Science 1991, 254, 1374–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erbse, A.; Schmidt, R.; Bornemann, T.; Schneider-Mergener, J.; Mogk, A.; Zahn, R.; Dougan, D.A.; Bukau, B. ClpS is an essential component of the N-end rule pathway in Escherichia coli. Nature 2006, 439, 753–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Román-Hernández, G.; Hou, J.Y.; Grant, R.A.; Sauer, R.T.; Baker, T.A. The ClpS adaptor mediates staged delivery of N-end rule substrates to the AAA+ ClpAP protease. Mol. Cell 2011, 43, 217–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varshavsky, A. The N-end rule pathway and regulation by proteolysis. Protein Sci. 2011, 20, 1298–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schweder, T.; Lee, K.H.; Lomovskaya, O.; Matin, A. Regulation of Escherichia coli starvation sigma factor (sigma s) by ClpXP protease. J. Bacteriol. 1996, 178, 470–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, M.; Rasulova, F.; Maurizi, M.R.; Woodgate, R. Subunit-specific degradation of the UmuD/D’ heterodimer by the ClpXP protease: The role of trans recognition in UmuD’ stability. EMBO J. 2000, 19, 5251–5258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flynn, J.M.; Levchenko, I.; Sauer, R.T.; Baker, T.A. Modulating substrate choice: The SspB adaptor delivers a regulator of the extracytoplasmic-stress response to the AAA+ protease ClpXP for degradation. Genes Dev. 2004, 18, 2292–2301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, R.; Zahn, R.; Bukau, B.; Mogk, A. ClpS is the recognition component for Escherichia coli substrates of the N-end rule degradation pathway. Mol. Microbiol. 2009, 72, 506–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickner, S.; Maurizi, M.R. Here’s the hook: Similar substrate binding sites in the chaperone domains of Clp and Lon. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1999, 96, 8318–8320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

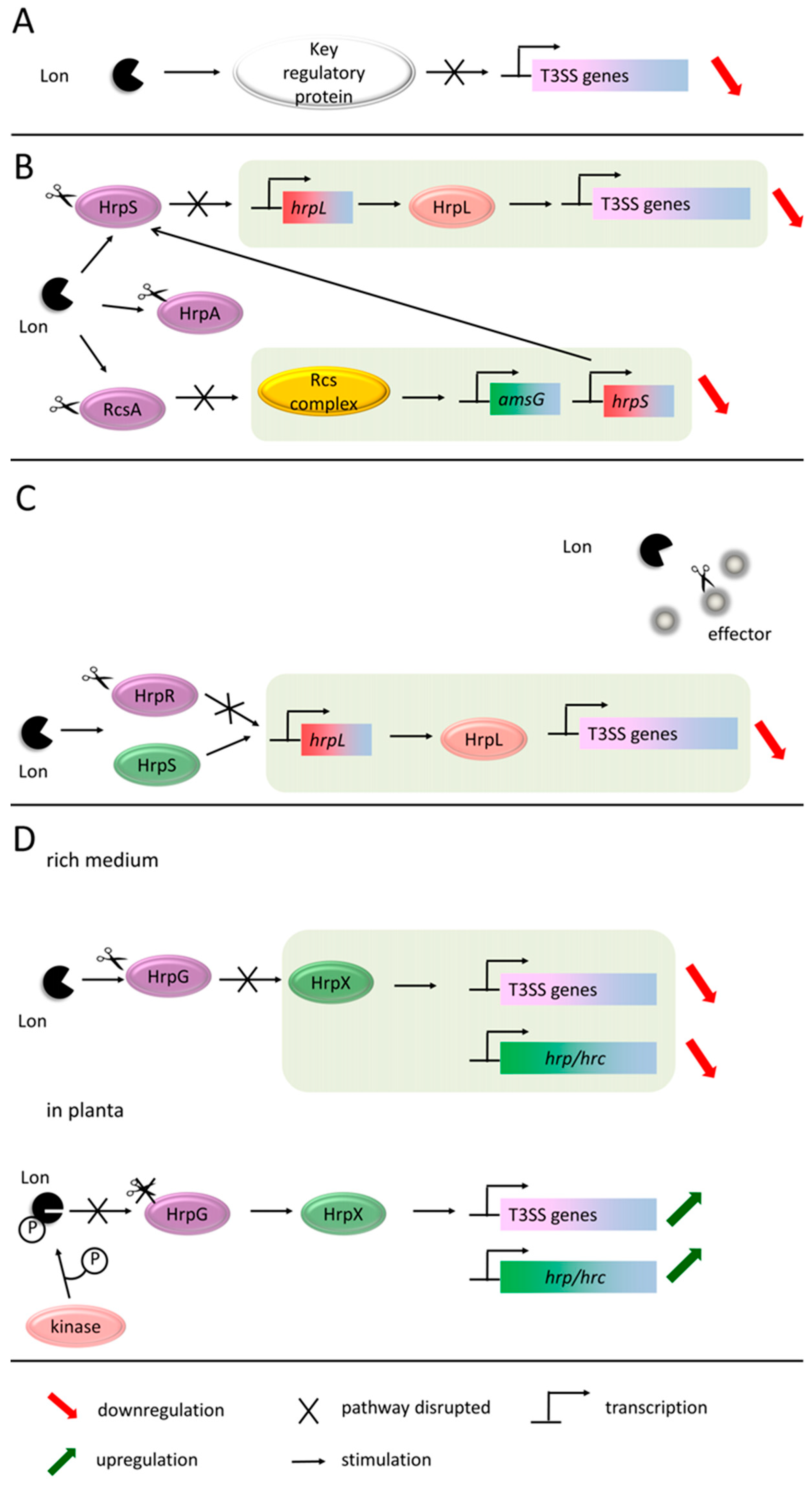

- Bretz, J.; Losada, L.; Lisboa, K.; Hutcheson, S.W. Lon protease functions as a negative regulator of type III protein secretion in Pseudomonas syringae. Mol. Microbiol. 2002, 45, 397–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rotanova, T.V.; Botos, I.; Melnikov, E.E.; Rasulova, F.; Gustchina, A.; Maurizi, M.R.; Wlodawer, A. Slicing a protease: Structural features of the ATP-dependent Lon proteases gleaned from investigations of isolated domains. Protein Sci. 2006, 15, 1815–1828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wohlever, M.L.; Baker, T.A.; Sauer, R.T. A mutation in the N domain of Escherichia coli Lon stabilizes dodecamers and selectively alters degradation of model substrates. J. Bacteriol. 2013, 195, 5622–5628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wohlever, M.L.; Baker, T.A.; Sauer, R.T. Roles of the N domain of the AAA+ Lon protease in substrate recognition, allosteric regulation and chaperone activity. Mol. Microbiol. 2014, 91, 66–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fischer, H.; Glockshuber, R. A point mutation within the ATP-binding site inactivates both catalytic functions of the ATP-dependent protease La (Lon) from Escherichia coli. FEBS Lett. 1994, 356, 101–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amerik, A.Y.; Antonov, V.K.; Gorbalenya, A.E.; Kotova, S.A.; Rotanova, T.V.; Shimbarevich, E.V. Site-directed mutagenesis of La protease. a catalytically active serine residue. FEBS Lett. 1991, 287, 211–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botos, I.; Melnikov, E.E.; Cherry, S.; Tropea, J.E.; Khalatova, A.G.; Rasulova, F.; Dauter, Z.; Maurizi, M.R.; Rotanova, T.V.; Wlodawer, A.; et al. The catalytic domain of Escherichia coli Lon protease has a unique fold and a Ser-Lys dyad in the active site. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 8140–8148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S.-C.; Jia, B.; Yang, J.-K.; Van, D.L.; Shao, Y.G.; Han, S.W.; Jeon, Y.-J.; Chung, C.H.; Cheong, G.-W. Oligomeric structure of the ATP-dependent protease La (Lon) of Escherichia coli. Mol. Cells 2006, 21, 129–134. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Vieux, E.F.; Wohlever, M.L.; Chen, J.Z.; Sauer, R.T.; Baker, T.A. Distinct quaternary structures of the AAA+ Lon protease control substrate degradation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, E2002–E2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gur, E.; Sauer, R.T. Recognition of misfolded proteins by Lon, a AAA(+) protease. Genes Dev. 2008, 22, 2267–2277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maurizi, M.R. Degradation in vitro of bacteriophage lambda N protein by Lon protease from Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 1987, 262, 2696–2703. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Menon, A.S.; Waxman, L.; Goldberg, A.L. The energy utilized in protein breakdown by the ATP-dependent protease (La) from Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 1987, 262, 722–726. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ishii, Y.; Sonezaki, S.; Iwasaki, Y.; Miyata, Y.; Akita, K.; Kato, Y.; Amano, F. Regulatory role of C-terminal residues of SulA in its degradation by Lon protease in Escherichia coli. J. Biochem. 2000, 127, 837–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez, M.; Frank, E.G.; Levine, A.S.; Woodgate, R. Lon-mediated proteolysis of the Escherichia coli UmuD mutagenesis protein: In vitro degradation and identification of residues required for proteolysis. Genes Dev. 1998, 12, 3889–3899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waxman, L.; Goldberg, A.L. Protease La from Escherichia coli hydrolyzes ATP and proteins in a linked fashion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1982, 79, 4883–4887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menon, A.S.; Goldberg, A.L. Binding of nucleotides to the ATP-dependent protease La from Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 1987, 262, 14921–14928. [Google Scholar]

- Waxman, L.; Goldberg, A.L. Selectivity of intracellular proteolysis: Protein substrates activate the ATP-dependent protease (La). Science 1986, 232, 500–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuroda, A.; Nomura, K.; Takiguchi, N.; Kato, J.; Ohtake, H. Inorganic polyphosphate stimulates lon-mediated proteolysis of nucleoid proteins in Escherichia coli. Cell. Mol. Biol. 2006, 52, 23–29. [Google Scholar]

- Chung, C.H.; Goldberg, A.L. DNA stimulates ATP-dependent proteolysis and protein-dependent ATPase activity of protease La from Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1982, 79, 795–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, A.L.; Waxman, L. The role of ATP hydrolysis in the breakdown of proteins and peptides by protease La from Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 1985, 260, 12029–12034. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Waxman, L.; Goldberg, A.L. Protease La, the lon gene product, cleaves specific fluorogenic peptides in an ATP-dependent reaction. J. Biol. Chem. 1985, 260, 12022–12028. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mizusawa, S.; Gottesman, S. Protein degradation in Escherichia coli: The lon gene controls the stability of sulA protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1983, 80, 358–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stout, V.; Torres-Cabassa, A.; Maurizi, M.R.; Gutnick, D.; Gottesman, S. RcsA, an unstable positive regulator of capsular polysaccharide synthesis. J. Bacteriol. 1991, 173, 1738–1747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griffith, K.L.; Shah, I.M.; Wolf, R.E. Proteolytic degradation of Escherichia coli transcription activators SoxS and MarA as the mechanism for reversing the induction of the superoxide (SoxRS) and multiple antibiotic resistance (Mar) regulons. Mol. Microbiol. 2004, 51, 1801–1816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arends, J.; Griego, M.; Thomanek, N.; Lindemann, C.; Kutscher, B.; Meyer, H.E.; Narberhaus, F. An Integrated Proteomic Approach Uncovers Novel Substrates and Functions of the Lon Protease in Escherichia coli. Proteomics 2018, 18, e1800080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, L.; Deng, X.; Xiao, Y.; Zhou, J.-M.; Tang, X. Mutation of Lon protease differentially affects the expression of Pseudomonas syringae type III secretion system genes in rich and minimal media and reduces pathogenicity. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 2007, 20, 682–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, S.; Stephens, B.B.; Alexandre, G.; Farrand, S.K. Lon protease of the alpha-proteobacterium Agrobacterium tumefaciens is required for normal growth, cellular morphology and full virulence. Microbiology 2006, 152, 1197–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skorko-Glonek, J.; Zurawa-Janicka, D.; Koper, T.; Jarzab, M.; Figaj, D.; Glaza, P.; Lipinska, B. HtrA protease family as therapeutic targets. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2013, 19, 977–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clausen, T.; Southan, C.; Ehrmann, M. The HtrA family of proteases: Implications for protein composition and cell fate. Mol. Cell 2002, 10, 443–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krojer, T.; Garrido-Franco, M.; Huber, R.; Ehrmann, M.; Clausen, T. Crystal structure of DegP (HtrA) reveals a new protease-chaperone machine. Nature 2002, 416, 455–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iwanczyk, J.; Damjanovic, D.; Kooistra, J.; Leong, V.; Jomaa, A.; Ghirlando, R.; Ortega, J. Role of the PDZ domains in Escherichia coli DegP protein. J. Bacteriol. 2007, 189, 3176–3186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krojer, T.; Pangerl, K.; Kurt, J.; Sawa, J.; Stingl, C.; Mechtler, K.; Huber, R.; Ehrmann, M.; Clausen, T. Interplay of PDZ and protease domain of DegP ensures efficient elimination of misfolded proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 7702–7707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hansen, G.; Hilgenfeld, R. Architecture and regulation of HtrA-family proteins involved in protein quality control and stress response. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2013, 70, 761–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skórko-Glonek, J.; Figaj, D.; Zarzecka, U.; Przepiora, T.; Renke, J.; Lipinska, B. The Extracellular Bacterial HtrA Proteins as Potential Therapeutic Targets and Vaccine Candidates. Curr. Med. Chem. 2017, 24, 2174–2204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Q.-T.; Bai, X.-C.; Chang, L.-F.; Wu, Y.; Wang, H.-W.; Sui, S.-F. Bowl-shaped oligomeric structures on membranes as DegP’s new functional forms in protein quality control. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 4858–4863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Sauer, R.T. Cage assembly of DegP protease is not required for substrate-dependent regulation of proteolytic activity or high-temperature cell survival. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 7263–7268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, C.H.; Dexter, P.; Evans, A.K.; Liu, C.; Hultgren, S.J.; Hruby, D.E. Escherichia coli DegP protease cleaves between paired hydrophobic residues in a natural substrate: The PapA pilin. J. Bacteriol. 2002, 184, 5762–5771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarzecka, U.; Modrak-Wojcik, A.; Bayassi, M.; Szewczyk, M.; Gieldon, A.; Lesner, A.; Koper, T.; Bzowska, A.; Sanguinetti, M.; Backert, S.; et al. Biochemical properties of the HtrA homolog from bacterium Stenotrophomonas maltophilia. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 109, 992–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, L.F.; Ohman, D.E. Use of cell wall stress to characterize sigma 22 (AlgT/U) activation by regulated proteolysis and its regulon in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Mol. Microbiol. 2009, 72, 183–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yorgey, P.; Rahme, L.G.; Tan, M.W.; Ausubel, F.M. The roles of mucD and alginate in the virulence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in plants, nematodes and mice. Mol. Microbiol. 2001, 41, 1063–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bordes, P.; Lavatine, L.; Phok, K.; Barriot, R.; Boulanger, A.; Castanié-Cornet, M.-P.; Déjean, G.; Lauber, E.; Becker, A.; Arlat, M.; et al. Insights into the extracytoplasmic stress response of Xanthomonas campestris pv. campestris: Role and regulation of sigma E-dependent activity. J. Bacteriol. 2011, 193, 246–264. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Block, A.; Alfano, J.R. Plant targets for Pseudomonas syringae type III effectors: Virulence targets or guarded decoys? Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2011, 14, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macho, A.P.; Zipfel, C. Plant PRRs and the activation of innate immune signaling. Mol. Cell 2014, 54, 263–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bigeard, J.; Colcombet, J.; Hirt, H. Signaling Mechanisms in Pattern-Triggered Immunity (PTI). Mol. Plant 2015, 8, 521–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, S.; Jamieson, P.; He, P. The cloak, dagger, and shield: Proteases in plant-pathogen interactions. Biochem. J. 2018, 475, 2491–2509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collmer, A.; Lindeberg, M.; Petnicki-Ocwieja, T.; Schneider, D.J.; Alfano, J.R. Genomic mining type III secretion system effectors in Pseudomonas syringae yields new picks for all TTSS prospectors. Trends Microbiol. 2002, 10, 462–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornelis, G.R. The Yersinia Ysc-Yop “type III” weaponry. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2002, 3, 742–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, W.; Marshall, N.C.; Rowland, J.L.; McCoy, J.M.; Worrall, L.J.; Santos, A.S.; Strynadka, N.C.J.; Finlay, B.B. Assembly, structure, function and regulation of type III secretion systems. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2017, 15, 323–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, J.D.G.; Dangl, J.L. The plant immune system. Nature 2006, 444, 323–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhou, J.-M. Plant immunity triggered by microbial molecular signatures. Mol. Plant 2010, 3, 783–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katagiri, F.; Tsuda, K. Understanding the plant immune system. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 2010, 23, 1531–1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muthamilarasan, M.; Prasad, M. Plant innate immunity: An updated insight into defense mechanism. J. Biosci. 2013, 38, 433–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bardoel, B.W.; van der Ent, S.; Pel, M.J.C.; Tommassen, J.; Pieterse, C.M.J.; van Kessel, K.P.M.; van Strijp, J.A.G. Pseudomonas evades immune recognition of flagellin in both mammals and plants. PLoS Pathog. 2011, 7, e1002206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komoriya, K.; Shibano, N.; Higano, T.; Azuma, N.; Yamaguchi, S.; Aizawa, S.I. Flagellar proteins and type III-exported virulence factors are the predominant proteins secreted into the culture media of Salmonella typhimurium. Mol. Microbiol. 1999, 34, 767–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walton, J.D. Deconstructing the Cell Wall. Plant Physiol. 1994, 104, 1113–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hématy, K.; Cherk, C.; Somerville, S. Host-pathogen warfare at the plant cell wall. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2009, 12, 406–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mudgett, M.B. New insights to the function of phytopathogenic bacterial type III effectors in plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2005, 56, 509–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, D.W.; Bogdanove, A.J.; Beer, S.V.; Collmer, A. Erwinia chrysanthemi hrp genes and their involvement in soft rot pathogenesis and elicitation of the hypersensitive response. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 1994, 7, 573–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.-H.; Gavilanes-Ruiz, M.; Okinaka, Y.; Vedel, R.; Berthuy, I.; Boccara, M.; Chen, J.W.-T.; Perna, N.T.; Keen, N.T. hrp genes of Erwinia chrysanthemi 3937 are important virulence factors. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 2002, 15, 472–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nissinen, R.M.; Ytterberg, A.J.; Bogdanove, A.J.; Van Wijk, K.J.; Beer, S.V. Analyses of the secretomes of Erwinia amylovora and selected hrp mutants reveal novel type III secreted proteins and an effect of HrpJ on extracellular harpin levels. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2007, 8, 55–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cunnac, S.; Lindeberg, M.; Collmer, A. Pseudomonas syringae type III secretion system effectors: Repertoires in search of functions. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2009, 12, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dodds, P.N.; Rathjen, J.P. Plant immunity: Towards an integrated view of plant-pathogen interactions. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2010, 11, 539–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chisholm, S.T.; Coaker, G.; Day, B.; Staskawicz, B.J. Host-microbe interactions: Shaping the evolution of the plant immune response. Cell 2006, 124, 803–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guttman, D.S.; Vinatzer, B.A.; Sarkar, S.F.; Ranall, M.V.; Kettler, G.; Greenberg, J.T. A functional screen for the type III (Hrp) secretome of the plant pathogen Pseudomonas syringae. Science 2002, 295, 1722–1726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salomon, D.; Guo, Y.; Kinch, L.N.; Grishin, N.V.; Gardner, K.H.; Orth, K. Effectors of animal and plant pathogens use a common domain to bind host phosphoinositides. Nat. Commun. 2013, 4, 2973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Li, W.; Xiang, T.; Liu, Z.; Laluk, K.; Ding, X.; Zou, Y.; Gao, M.; Zhang, X.; Chen, S.; et al. Receptor-like cytoplasmic kinases integrate signaling from multiple plant immune receptors and are targeted by a Pseudomonas syringae effector. Cell Host Microbe 2010, 7, 290–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chinchilla, D.; Zipfel, C.; Robatzek, S.; Kemmerling, B.; Nürnberger, T.; Jones, J.D.G.; Felix, G.; Boller, T. A flagellin-induced complex of the receptor FLS2 and BAK1 initiates plant defence. Nature 2007, 448, 497–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heese, A.; Hann, D.R.; Gimenez-Ibanez, S.; Jones, A.M.E.; He, K.; Li, J.; Schroeder, J.I.; Peck, S.C.; Rathjen, J.P. The receptor-like kinase SERK3/BAK1 is a central regulator of innate immunity in plants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 12217–12222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kadota, Y.; Sklenar, J.; Derbyshire, P.; Stransfeld, L.; Asai, S.; Ntoukakis, V.; Jones, J.D.; Shirasu, K.; Menke, F.; Jones, A.; et al. Direct regulation of the NADPH oxidase RBOHD by the PRR-associated kinase BIK1 during plant immunity. Mol. Cell 2014, 54, 43–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, D.; Wu, S.; Gao, X.; Zhang, Y.; Shan, L.; He, P. A receptor-like cytoplasmic kinase, BIK1, associates with a flagellin receptor complex to initiate plant innate immunity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 496–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ade, J.; DeYoung, B.J.; Golstein, C.; Innes, R.W. Indirect activation of a plant nucleotide binding site-leucine-rich repeat protein by a bacterial protease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 2531–2536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Kim, P.; Yu, L.; Cai, G.; Chen, S.; Alfano, J.R.; Zhou, J.-M. Activation-Dependent Destruction of a Co-receptor by a Pseudomonas syringae Effector Dampens Plant Immunity. Cell Host Microbe 2016, 20, 504–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mudgett, M.B.; Staskawicz, B.J. Characterization of the Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato AvrRpt2 protein: Demonstration of secretion and processing during bacterial pathogenesis. Mol. Microbiol. 1999, 32, 927–941. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Axtell, M.J.; Chisholm, S.T.; Dahlbeck, D.; Staskawicz, B.J. Genetic and molecular evidence that the Pseudomonas syringae type III effector protein AvrRpt2 is a cysteine protease. Mol. Microbiol. 2003, 49, 1537–1546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coaker, G.; Zhu, G.; Ding, Z.; Van Doren, S.R.; Staskawicz, B. Eukaryotic cyclophilin as a molecular switch for effector activation. Mol. Microbiol. 2006, 61, 1485–1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coaker, G.; Falick, A.; Staskawicz, B. Activation of a phytopathogenic bacterial effector protein by a eukaryotic cyclophilin. Science 2005, 308, 548–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

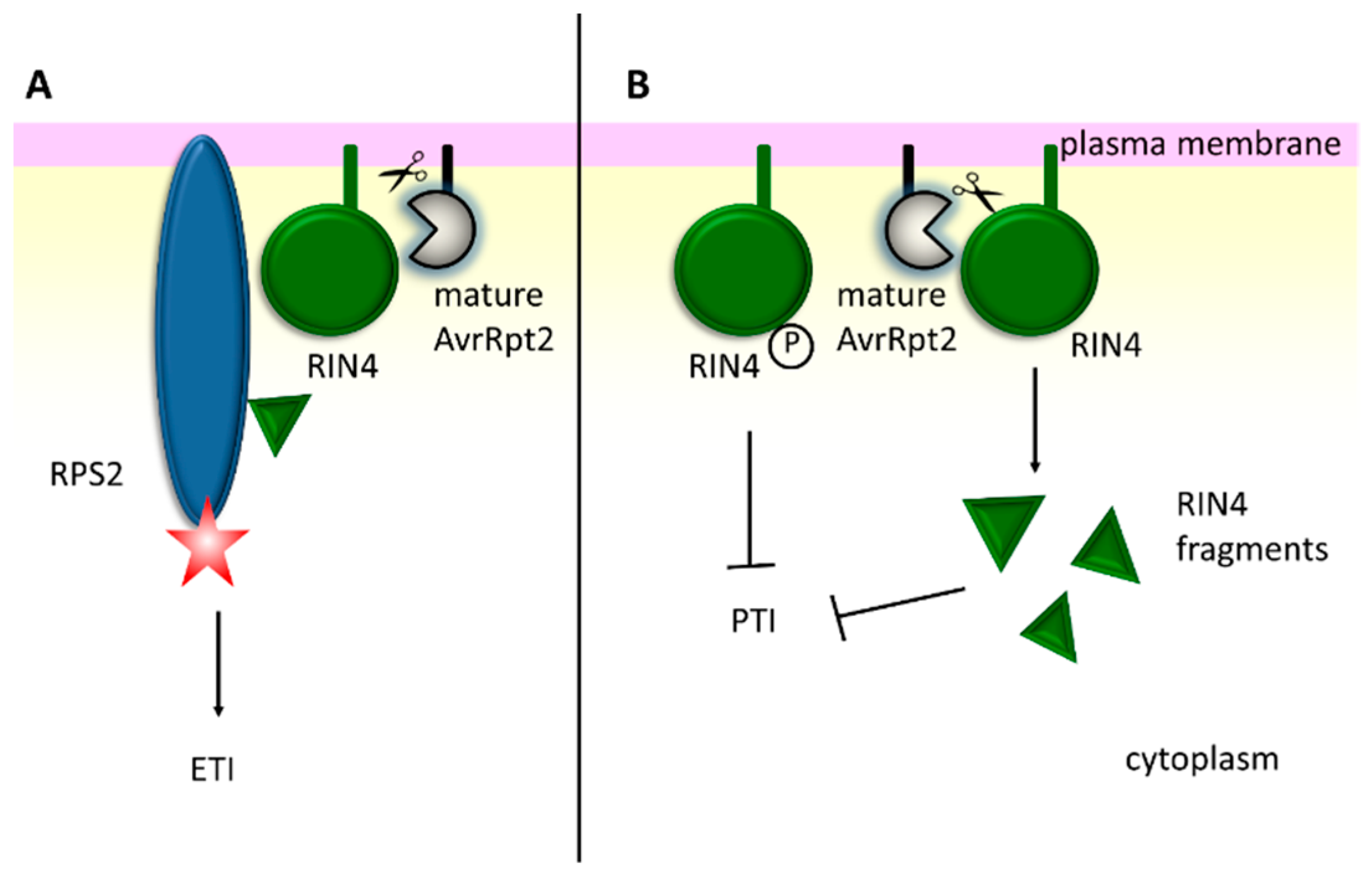

- Mackey, D.; Belkhadir, Y.; Alonso, J.M.; Ecker, J.R.; Dangl, J.L. Arabidopsis RIN4 is a target of the type III virulence effector AvrRpt2 and modulates RPS2-mediated resistance. Cell 2003, 112, 379–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Elmore, J.M.; Fuglsang, A.T.; Palmgren, M.G.; Staskawicz, B.J.; Coaker, G. RIN4 functions with plasma membrane H+-ATPases to regulate stomatal apertures during pathogen attack. PLoS Biol. 2009, 7, e1000139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.; Bourdais, G.; Yu, G.; Robatzek, S.; Coaker, G. Phosphorylation of the Plant Immune Regulator RPM1-INTERACTING PROTEIN4 Enhances Plant Plasma Membrane H+-ATPase Activity and Inhibits Flagellin-Triggered Immune Responses in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2015, 27, 2042–2056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afzal, A.J.; da Cunha, L.; Mackey, D. Separable fragments and membrane tethering of Arabidopsis RIN4 regulate its suppression of PAMP-triggered immunity. Plant Cell 2011, 23, 3798–3811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Afzal, A.J.; Kim, J.H.; Mackey, D. The role of NOI-domain containing proteins in plant immune signaling. BMC Genom. 2013, 14, 327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eschen-Lippold, L.; Jiang, X.; Elmore, J.M.; Mackey, D.; Shan, L.; Coaker, G.; Scheel, D.; Lee, J. Bacterial AvrRpt2-Like Cysteine Proteases Block Activation of the Arabidopsis Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinases, MPK4 and MPK11. Plant Physiol. 2016, 171, 2223–2238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, K.-W.; Ma, W. Phytohormone pathways as targets of pathogens to facilitate infection. Plant Mol. Biol. 2016, 91, 713–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Üstün, S.; Bartetzko, V.; Börnke, F. The Xanthomonas campestris type III effector XopJ targets the host cell proteasome to suppress salicylic-acid mediated plant defence. PLoS Pathog. 2013, 9, e1003427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Üstün, S.; Börnke, F. The Xanthomonas campestris type III effector XopJ proteolytically degrades proteasome subunit RPT6. Plant Physiol. 2015, 168, 107–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spoel, S.H.; Mou, Z.; Tada, Y.; Spivey, N.W.; Genschik, P.; Dong, X. Proteasome-mediated turnover of the transcription coactivator NPR1 plays dual roles in regulating plant immunity. Cell 2009, 137, 860–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Üstün, S.; König, P.; Guttman, D.S.; Börnke, F. HopZ4 from Pseudomonas syringae, a member of the HopZ type III effector family from the YopJ superfamily, inhibits the proteasome in plants. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 2014, 27, 611–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staswick, P.E. JAZing up jasmonate signaling. Trends Plant Sci. 2008, 13, 66–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gimenez-Ibanez, S.; Boter, M.; Fernández-Barbero, G.; Chini, A.; Rathjen, J.P.; Solano, R. The bacterial effector HopX1 targets JAZ transcriptional repressors to activate jasmonate signaling and promote infection in Arabidopsis. PLoS Biol. 2014, 12, e1001792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weingart, H.; Volksch, B. Ethylene Production by Pseudomonas syringae Pathovars In Vitro and In Planta. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1997, 63, 156–161. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Valls, M.; Genin, S.; Boucher, C. Integrated regulation of the type III secretion system and other virulence determinants in Ralstonia solanacearum. PLoS Pathog. 2006, 2, e82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weingart, H.; Ullrich, H.; Geider, K.; Völksch, B. The Role of Ethylene Production in Virulence of Pseudomonas syringae pvs. glycinea and phaseolicola. Phytopathology 2001, 91, 511–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.-G.; Stork, W.; Mudgett, M.B. Xanthomonas type III effector XopD desumoylates tomato transcription factor SlERF4 to suppress ethylene responses and promote pathogen growth. Cell Host Microbe 2013, 13, 143–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chandler, J.W.; Werr, W. Cytokinin-auxin crosstalk in cell type specification. Trends Plant Sci. 2015, 20, 291–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaller, G.E.; Bishopp, A.; Kieber, J.J. The yin-yang of hormones: Cytokinin and auxin interactions in plant development. Plant Cell 2015, 27, 44–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludwig-Müller, J. Bacteria and fungi controlling plant growth by manipulating auxin: Balance between development and defense. J. Plant Physiol. 2015, 172, 4–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naseem, M.; Kaltdorf, M.; Dandekar, T. The nexus between growth and defence signalling: Auxin and cytokinin modulate plant immune response pathways. J. Exp. Bot. 2015, 66, 4885–4896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.; Agnew, J.L.; Cohen, J.D.; He, P.; Shan, L.; Sheen, J.; Kunkel, B.N. Pseudomonas syringae type III effector AvrRpt2 alters Arabidopsis thaliana auxin physiology. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 20131–20136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, F.; Wu, S.; Sun, W.; Coaker, G.; Kunkel, B.; He, P.; Shan, L. The Pseudomonas syringae type III effector AvrRpt2 promotes pathogen virulence via stimulating Arabidopsis auxin/indole acetic acid protein turnover. Plant Physiol. 2013, 162, 1018–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Solanilla, E.; Bronstein, P.A.; Schneider, A.R.; Collmer, A. HopPtoN is a Pseudomonas syringae Hrp (type III secretion system) cysteine protease effector that suppresses pathogen-induced necrosis associated with both compatible and incompatible plant interactions. Mol. Microbiol. 2004, 54, 353–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez-Herva, J.J.; González-Melendi, P.; Cuartas-Lanza, R.; Antúnez-Lamas, M.; Río-Alvarez, I.; Li, Z.; López-Torrejón, G.; Díaz, I.; Del Pozo, J.C.; Chakravarthy, S.; et al. A bacterial cysteine protease effector protein interferes with photosynthesis to suppress plant innate immune responses. Cell. Microbiol. 2012, 14, 669–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coker, J.S.; Vian, A.; Davies, E. Identification, accumulation, and functional prediction of novel tomato transcripts systemically upregulated after fire damage. Physiol. Plant. 2005, 124, 311–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, X.; Hargett, S.R.; Frankel, L.K.; Bricker, T.M. The PsbQ protein is required in Arabidopsis for photosystem II assembly/stability and photoautotrophy under low light conditions. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 26260–26267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csonka, L.N. Physiological and genetic responses of bacteria to osmotic stress. Microbiol. Rev. 1989, 53, 121–147. [Google Scholar]

- Jordan, S.; Hutchings, M.I.; Mascher, T. Cell envelope stress response in Gram-positive bacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2008, 32, 107–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raivio, T.L. Envelope stress responses and Gram-negative bacterial pathogenesis. Mol. Microbiol. 2005, 56, 1119–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, S.M.; Festa, R.A.; Pearce, M.J.; Darwin, K.H. Self-compartmentalized bacterial proteases and pathogenesis. Mol. Microbiol. 2006, 60, 553–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ades, S.E.; Connolly, L.E.; Alba, B.M.; Gross, C.A. The Escherichia coli sigma(E)-dependent extracytoplasmic stress response is controlled by the regulated proteolysis of an anti-sigma factor. Genes Dev. 1999, 13, 2449–2461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battesti, A.; Majdalani, N.; Gottesman, S. The RpoS-mediated general stress response in Escherichia coli. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2011, 65, 189–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, G.; Klauck, E.; Hengge-Aronis, R. Regulation of RpoS proteolysis in Escherichia coli: The response regulator RssB is a recognition factor that interacts with the turnover element in RpoS. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1999, 96, 6439–6444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pruteanu, M.; Hengge-Aronis, R. The cellular level of the recognition factor RssB is rate-limiting for sigmaS proteolysis: Implications for RssB regulation and signal transduction in sigma S turnover in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 2002, 45, 1701–1713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bougdour, A.; Wickner, S.; Gottesman, S. Modulating RssB activity: IraP, a novel regulator of sigma(S) stability in Escherichia coli. Genes Dev. 2006, 20, 884–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bougdour, A.; Cunning, C.; Baptiste, P.J.; Elliott, T.; Gottesman, S. Multiple pathways for regulation of sigma S (RpoS) stability in Escherichia coli via the action of multiple anti-adaptors. Mol. Microbiol. 2008, 68, 298–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peterson, C.N.; Levchenko, I.; Rabinowitz, J.D.; Baker, T.A.; Silhavy, T.J. RpoS proteolysis is controlled directly by ATP levels in Escherichia coli. Genes Dev. 2012, 26, 548–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine, 8600 Rockville Pike, Bethesda MD, 20894 USA. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ (accessed on 27 January 2019).

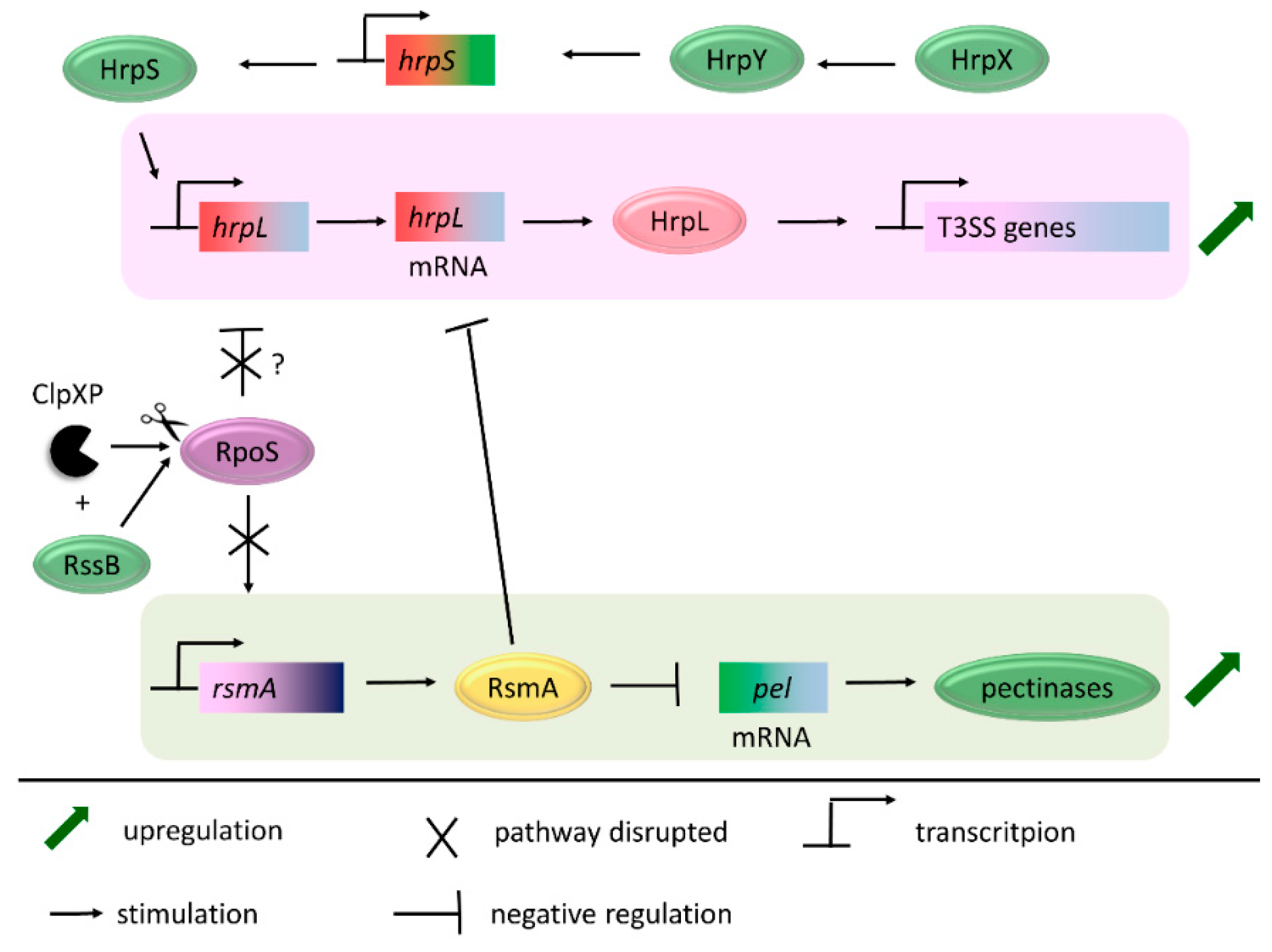

- Li, Y.; Yamazaki, A.; Zou, L.; Biddle, E.; Zeng, Q.; Wang, Y.; Lin, H.; Wang, Q.; Yang, C.-H. ClpXP protease regulates the type III secretion system of Dickeya dadantii 3937 and is essential for the bacterial virulence. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 2010, 23, 871–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.H.; Zhao, Y. ClpXP-Dependent RpoS Degradation Enables Full Activation of Type III Secretion System, Amylovoran Production, and Motility in Erwinia amylovora. Phytopathology 2017, 107, 1346–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vakulskas, C.A.; Potts, A.H.; Babitzke, P.; Ahmer, B.M.M.; Romeo, T. Regulation of bacterial virulence by Csr (Rsm) systems. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2015, 79, 193–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Chatterjee, A.; Liu, Y.; Dumenyo, C.K.; Chatterjee, A.K. Identification of a global repressor gene, rsmA, of Erwinia carotovora subsp. carotovora that controls extracellular enzymes, N-(3-oxohexanoyl)-l-homoserine lactone, and pathogenicity in soft-rotting Erwinia spp. J. Bacteriol. 1995, 177, 5108–5115. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, X.; Teper, D.; Andrade, M.O.; Zhang, T.; Chen, S.; Song, W.-Y.; Wang, N. A Phosphorylation Switch on Lon Protease Regulates Bacterial Type III Secretion System in Host. MBio 2018, 9, e02146-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.H.; Ancona, V.; Zhao, Y. Lon protease modulates virulence traits in Erwinia amylovora by direct monitoring of major regulators and indirectly through the Rcs and Gac-Csr regulatory systems. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2018, 19, 827–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eastgate, J.A.; Taylor, N.; Coleman, M.J.; Healy, B.; Thompson, L.; Roberts, I.S. Cloning, expression, and characterization of the lon gene of Erwinia amylovora: Evidence for a heat shock response. J. Bacteriol. 1995, 177, 932–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hutcheson, S.W.; Bretz, J.; Sussan, T.; Jin, S.; Pak, K. Enhancer-binding proteins HrpR and HrpS interact to regulate hrp-encoded type III protein secretion in Pseudomonas syringae strains. J. Bacteriol. 2001, 183, 5589–5598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Losada, L.C.; Hutcheson, S.W. Type III secretion chaperones of Pseudomonas syringae protect effectors from Lon-associated degradation. Mol. Microbiol. 2005, 55, 941–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huisman, O.; D’Ari, R.; Gottesman, S. Cell-division control in Escherichia coli: Specific induction of the SOS function SfiA protein is sufficient to block septation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1984, 81, 4490–4494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koebnik, R.; Krüger, A.; Thieme, F.; Urban, A.; Bonas, U. Specific binding of the Xanthomonas campestris pv. vesicatoria AraC-type transcriptional activator HrpX to plant-inducible promoter boxes. J. Bacteriol. 2006, 188, 7652–7660. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Guo, Y.; Figueiredo, F.; Jones, J.; Wang, N. HrpG and HrpX play global roles in coordinating different virulence traits of Xanthomonas axonopodis pv. citri. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 2011, 24, 649–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kogenaru, S.; Qing, Y.; Guo, Y.; Wang, N. RNA-seq and microarray complement each other in transcriptome profiling. BMC Genom. 2012, 13, 629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Callaway, E.M.; Jones, J.B.; Wilson, M. Visualisation of hrp gene expression in Xanthomonas euvesicatoria in the tomato phyllosphere. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2009, 124, 379–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.; Xiao, Y.; Zhou, J.-M. Regulation of the type III secretion system in phytopathogenic bacteria. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 2006, 19, 1159–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrancken, K.; Holtappels, M.; Schoofs, H.; Deckers, T.; Valcke, R. Pathogenicity and infection strategies of the fire blight pathogen Erwinia amylovora in Rosaceae: State of the art. Microbiology 2013, 159, 823–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reverchon, S.; Nasser, W. Dickeya ecology, environment sensing and regulation of virulence programme. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 2013, 5, 622–636. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Miller, S.B.M.; Mogk, A.; Bukau, B. Spatially organized aggregation of misfolded proteins as cellular stress defense strategy. J. Mol. Biol. 2015, 427, 1564–1574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flanagan, J.M.; Bewley, M.C. Protein quality control in bacterial cells: Integrated networks of chaperones and ATP-dependent proteases. Genet. Eng. 2002, 24, 17–47. [Google Scholar]

- Merdanovic, M.; Clausen, T.; Kaiser, M.; Huber, R.; Ehrmann, M. Protein quality control in the bacterial periplasm. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2011, 65, 149–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, C.-Y.; Deng, A.-H.; Sun, S.-T.; Wang, L.; Wu, J.; Wu, Y.; Chen, X.-Y.; Fang, R.-X.; Wen, T.-Y.; Qian, W. The periplasmic PDZ domain-containing protein Prc modulates full virulence, envelops stress responses, and directly interacts with dipeptidyl peptidase of Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 2014, 27, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, X.; Zghidi-Abouzid, O.; Oger-Desfeux, C.; Hommais, F.; Greliche, N.; Muskhelishvili, G.; Nasser, W.; Reverchon, S. Global transcriptional response of Dickeya dadantii to environmental stimuli relevant to the plant infection. Environ. Microbiol. 2016, 18, 3651–3672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T.; Yin, C.; Zhang, Y.; Shi, H.; Wang, J.; Sun, L.; Shao, X.; Gao, R.; Wang, W.; Deng, X. Lon Protease Is Involved in RhpRS-Mediated Regulation of Type III Secretion in Pseudomonas syringae. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 2016, 29, 807–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Bacterial Pathogen | Plant Host | Disease | Disease Symptoms | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pseudomonas syringae | Wide range (e.g., tomato, beans, horse-chestnut, and tobacco), depending on the pathovar. | Bacterial speck, halo blight, and bleeding canker | Chlorosis, necrosis, cankers, blights, and water-soaked lesions | [7] |

| Ralstonia solanacearum | Two hundred plant species (e.g., potato, tomato, tobacco, eggplant, ornamentals, and banana) | Brown rot, bacterial wilt, and Moko disease of banana | Plant wilting and rotting | [6,8] |

| Agrobacterium tumefaciens | Wide range (e.g., woody ornamental shrubs, vines, shade trees, fruit trees, cherry, berry, walnut, and herbaceous perennials) | Crown gall tumor | Neoplastic and in consequence limiting plant’s growth | [6,9] |

| Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae | Rice | Leaf blight and leaf streak | Pale-green to grey-green and water-soaked streaks near the leaf tip and margins | [6,10] |

| Xanthomonas campestris | A large number of species of the Brassicaceae family, such as pepper, tomato, and cotton | Black rot | Blackening of the leaf veins | [6,11] |

| Xanthomonas axonopodis | Wide range (e.g., citrus, cassava, mango, ornamentals, and bean) | Bacterial blight and citrus canker | Angular leaf spots and leaf wilting | [6,12] |

| Erwinia amylovora | young fruit trees (apple, pear, quince, blackberry, and raspberry), and rosaceous ornamentals | Fire blight | Grey-green water soaking and necrosis | [6] |

| Xylella fastidiosa | Wide range (e.g., citrus, peach, elm, oak, oleander, maple, sycamore, coffee, peach, mulberry, plum, periwinkle, and pear) | Pierce’s disease and leaf scorch disease | Chlorosis and premature abscission of leaves and fruits | [6,13,14] |

| Dickeya dadantii and solani | Wide range (e.g., potato, rice, maize, pineapple, banana, and chicory) | Blackleg and soft rot | Stem and tuber rotting | [6,15] |

| Pectobacterium carotovorum | Wide range (e.g., potato, ornamentals, cabbage, and carrot) | Soft rot | Tuber, stem, and leaves rotting | [6,16] |

| Protease Name | MEROPS | Co-factor | Inhibitors | Processing | Secretion Conditions | Gene Expression | Role in Virulence | Proteolytic Activity | Additional Features | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prt1 from P. carotovorum subsp. carotovorum EC14 | Clan MA, Family M4 | Zn2+ not Ca2+ | Phenan-throline, phosphoramidon, EGTA, Fe2+, and Cu2+ | N-terminal pre-pro-processing | Not secreted in the rich medium; induction of secretion by gelatin | Induced in planta | Unknown | Optimal temperature is 50 °C, optimal pH is 6.0; activity against gelatin casein, potato lectin, ribonuclease A, and BSA; peptide bond cleavage preferentially after proline followed by Ala, Val, or Phe | Low thermal stabiity | [24,27] |

| PrtW from P. carotovorum subsp. carotovorum SCC3193 | Clan MA, Family M10 | Not shown, but protease has Zn2+ and Ca2+ binding motifs | EDTA | Unknown | Unknown | In vitro induction by celery and potato extract with a maximum in the early exponential phase and in the presence of PGA at the beginning of stationary phase; in vivo induction in planta in the early stage of infection | The PrtW mutants infected tobacco plants less efficiently in the in vitro culture and showed reduced maceration of potato tubers. | Activity against casein | Synthesis regulated by ExpI and ExpA–ExpS | [28,29] |

| PrtA from D. chrysanthemii B374 | Clan MA, Family M10 | Not shown but protease has Zn2+ and Ca2+ binding motifs | EDTA | The N-terminal propeptide is cleaved after secretion | Rich medium during exponential and stationary phase | Unknown | Unknown | Activity against casein | Secretion via T1SS and secretion signal at the C-terminus | [30,31] |

| PrtB from D. chrysanthemii B374 | Clan MA and Family M10 | Zn2+ is required for activity and Ca2+ is required for stability | EDTA and phenan-throline | The N-terminal propeptide is cleaved after secretion in the rich medium (not minimal) | Rich medium during exponential and stationary phase | Unknown | Unknown | Activity against casein | Secretion via T1SS and secretion signal at the C-terminus | [30,32] |

| PrtC from D. chrysanthemii B374 | Clan MA and Family M10 | Zn2+ is required for activity, and Ca2+ and Mg2+ for stability | EDTA and phenan-throline | The N-terminal propeptide is cleaved after secretion in the rich medium (not minimal) | Rich medium during exponential and stationary phase | Unknown | Unknown | Activity against casein | Secretion via T1SS and secretion signal at the c-terminus | [30,32] |

| PrtG from D. chrysanthemii B374 | Clan MA, Family M10 | Unknown | EDTA | The N-terminal propeptide is cleaved after secretion | Rich medium | Unknown | Unknown | Activity against gelatin | Secretion via T1SS and secretion signal at the C-terminus; low abundance protease | [33] |

| Prt2 form X. campestris pv. campestris | Unassigned | Zn2+ is required for activity, in addition, Ca2+, Mn2+, and Mg2+ are required for activity and/or stability | EDTA; phenan-throline | Unknown | Rich medium and minimal medium supplemented with plant cell walls | Unknown | The mutant lacking Prt1 (serine protease) and Prt2 showed reduced maceration symptoms in the turnip leaves | Optimal pH of around 8; activity against casein | Prt2 and Prt1 are major proteases of the vascular pathovars of X. campestris | [26] |

| Prt3 from X. campestris pv. raphanin and X. campestris pv. armoraciae | Unassigned | Zn2+ | Phenan-throline, DTT, and insensitive to EDTA | Probably by cutting the signal peptide | Secreted in rich medium and in planta | Unknown | Unknown | Optimal pH of 8–9; activity against β-casein | The major protease of the mesophilic pathovars of X. campestris | [25] |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Figaj, D.; Ambroziak, P.; Przepiora, T.; Skorko-Glonek, J. The Role of Proteases in the Virulence of Plant Pathogenic Bacteria. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 672. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms20030672

Figaj D, Ambroziak P, Przepiora T, Skorko-Glonek J. The Role of Proteases in the Virulence of Plant Pathogenic Bacteria. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2019; 20(3):672. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms20030672

Chicago/Turabian StyleFigaj, Donata, Patrycja Ambroziak, Tomasz Przepiora, and Joanna Skorko-Glonek. 2019. "The Role of Proteases in the Virulence of Plant Pathogenic Bacteria" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 20, no. 3: 672. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms20030672

APA StyleFigaj, D., Ambroziak, P., Przepiora, T., & Skorko-Glonek, J. (2019). The Role of Proteases in the Virulence of Plant Pathogenic Bacteria. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 20(3), 672. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms20030672