Mycobacterium tuberculosis β-Carbonic Anhydrases: Novel Targets for Developing Antituberculosis Drugs

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Molecular Biology

2.1. M. tuberculosis Rv1284

2.2. M. tuberculosis Rv3588c

2.3. M. tuberculosis Rv3273

3. M. marinum Is a Suitable Model for Studying the Roles of β-CAs

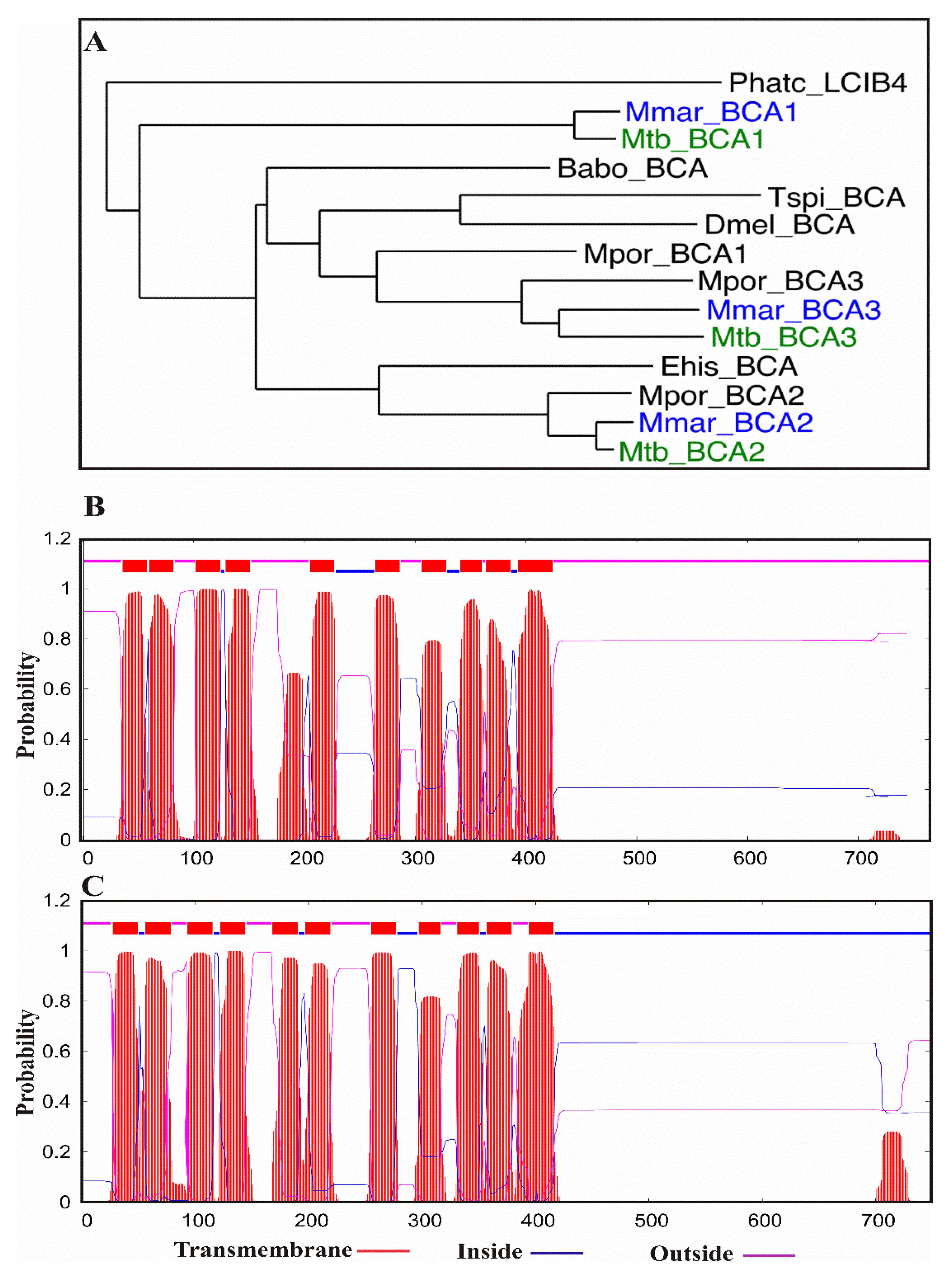

Sequence and Phylogenetic Analysis of β-CAs

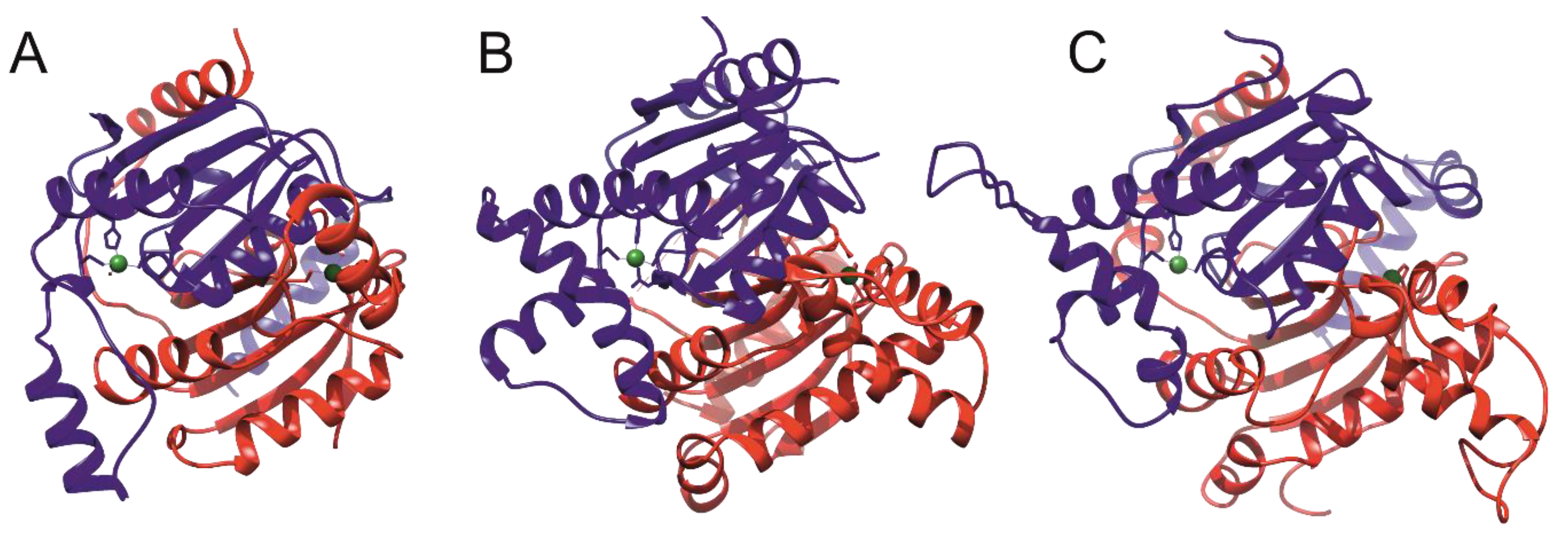

4. Structures of Mtb β-CAs

5. Expression Analysis of β-CAs from Mmar

6. In Vitro Inhibition of Mycobacterial β-CAs

6.1. Inhibition of Mtb β-CAs Using Sulfonamides and Their Derivatives

6.2. Mono and Dithiocarbamates as Inhibitors of Mycobacterial β-CAs

6.3. Phenolic Natural Products and Phenolic Acids as Mycobacterial β-CA Inhibitors

6.4. Carboxylic Acids as Inhibitors of Mycobacterial β-CA

7. Inhibition of Mycobacterial Strains in Culture

8. In Vivo Inhibition of Mycobacteria by CA Inhibitors

9. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CA | Carbonic anhydrase |

| Mtb | Mycobacteriumtuberculosis |

| Mmar | Mycobacteriummarinum |

| CAI | Carbonic anhydrase inhibitor |

| MDR-TB | Multidrug-resistant tuberculosis |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| TB | Tuberculosis |

| MTBC | Mycobacteriumtuberculosis complex |

| NTM | Nontuberculous mycobacteria |

| ETZ | Ethoxzolamide |

| β-CA1 | Beta-carbonic anhydrase 1 |

| β-CA2 | Beta-carbonic anhydrase 2 |

| β-CA3 | Beta-carbonic anhydrase 3 |

| RR-TB | Resistant to rifampicin Mycobacterium tuberculosis |

| eDNA | Extracellular DNA |

| PDB | Protein Data Bank |

| MTC | Monothiocarbamates |

| DTC | Dithiocarbamates |

| NP | Natural products |

| MIC | Minimal inhibitory concentration |

References

- Glaziou, P.; Floyd, K.; Raviglione, M.C. Global Epidemiology of Tuberculosis. Semin. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2018, 39, 271–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. Global Tuberculosis Report; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 1–277. ISBN 978-92-4-156564-6. [Google Scholar]

- Cole, S.T.; Brosch, R.; Parkhill, J.; Garnier, T.; Churcher, C.; Harris, D.; Gordon, S.V.; Eiglmeier, K.; Gas, S.; Barry, C.E., 3rd; et al. Deciphering the biology of Mycobacterium tuberculosis from the complete genome sequence. Nature 1998, 393, 537–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stinear, T.P.; Seemann, T.; Harrison, P.F.; Jenkin, G.A.; Davies, J.K.; Johnson, P.D.; Abdellah, Z.; Arrowsmith, C.; Chillingworth, T.; Churcher, C.; et al. Insights from the complete genome sequence of Mycobacterium marinum on the evolution of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Genome Res. 2008, 18, 729–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garnier, T.; Eiglmeier, K.; Camus, J.C.; Medina, N.; Mansoor, H.; Pryor, M.; Duthoy, S.; Grondin, S.; Lacroix, C.; Monsempe, C.; et al. The complete genome sequence of Mycobacterium bovis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 7877–7882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaul, G.; Kapoor, E.; Dasgupta, A.; Chopra, S. Management of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis in the 21st century. Drugs Today (Barc.) 2019, 55, 215–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saxena, A.K.; Singh, A. Mycobacterial tuberculosis Enzyme Targets and their Inhibitors. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2019, 19, 337–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aspatwar, A.; Haapanen, S.; Parkkila, S. An Update on the Metabolic Roles of Carbonic Anhydrases in the Model Alga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Metabolites 2018, 8, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aspatwar, A.; Winum, J.Y.; Carta, F.; Supuran, C.T.; Hammaren, M.; Parikka, M.; Parkkila, S. Carbonic Anhydrase Inhibitors as Novel Drugs against Mycobacterial beta-Carbonic Anhydrases: An Update on In Vitro and In Vivo Studies. Molecules 2018, 23, 2911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aspatwar, A.; Tolvanen, M.E.; Ortutay, C.; Parkkila, S. Carbonic anhydrase related proteins: Molecular biology and evolution. Subcell. Biochem. 2014, 75, 135–156. [Google Scholar]

- Supuran, C.T. Carbonic anhydrases: Novel therapeutic applications for inhibitors and activators. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2008, 7, 168–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishimori, I.; Minakuchi, T.; Kohsaki, T.; Onishi, S.; Takeuchi, H.; Vullo, D.; Scozzafava, A.; Supuran, C.T. Carbonic anhydrase inhibitors: The beta-carbonic anhydrase from Helicobacter pylori is a new target for sulfonamide and sulfamate inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2007, 17, 3585–3594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klengel, T.; Liang, W.J.; Chaloupka, J.; Ruoff, C.; Schroppel, K.; Naglik, J.R.; Eckert, S.E.; Mogensen, E.G.; Haynes, K.; Tuite, M.F.; et al. Fungal adenylyl cyclase integrates CO2 sensing with cAMP signaling and virulence. Curr. Biol. 2005, 15, 2021–2026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Innocenti, A.; Muhlschlegel, F.A.; Hall, R.A.; Steegborn, C.; Scozzafava, A.; Supuran, C.T. Carbonic anhydrase inhibitors: Inhibition of the beta-class enzymes from the fungal pathogens Candida albicans and Cryptococcus neoformans with simple anions. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2008, 18, 5066–5070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Innocenti, A.; Leewattanapasuk, W.; Muhlschlegel, F.A.; Mastrolorenzo, A.; Supuran, C.T. Carbonic anhydrase inhibitors. Inhibition of the beta-class enzyme from the pathogenic yeast Candida glabrata with anions. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2009, 19, 4802–4805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isik, S.; Kockar, F.; Aydin, M.; Arslan, O.; Guler, O.O.; Innocenti, A.; Scozzafava, A.; Supuran, C.T. Carbonic anhydrase inhibitors: Inhibition of the beta-class enzyme from the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae with sulfonamides and sulfamates. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2009, 17, 1158–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isik, S.; Kockar, F.; Arslan, O.; Guler, O.O.; Innocenti, A.; Supuran, C.T. Carbonic anhydrase inhibitors. Inhibition of the beta-class enzyme from the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae with anions. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2008, 18, 6327–6331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prete, S.D.; Angeli, A.; Ghobril, C.; Hitce, J.; Clavaud, C.; Marat, X.; Supuran, C.T.; Capasso, C. Anion Inhibition Profile of the beta-Carbonic Anhydrase from the Opportunist Pathogenic Fungus Malassezia Restricta Involved in Dandruff and Seborrheic Dermatitis. Metabolites 2019, 9, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nocentini, A.; Osman, S.M.; Almeida, I.A.; Cardoso, V.; Alasmary, F.A.S.; AlOthman, Z.; Vermelho, A.B.; Gratteri, P.; Supuran, C.T. Appraisal of anti-protozoan activity of nitroaromatic benzenesulfonamides inhibiting carbonic anhydrases from Trypanosoma cruzi and Leishmania donovani. J. Enzym. Inhib. Med. Chem. 2019, 34, 1164–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akdemir, A.; Angeli, A.; Goktas, F.; Eraslan Elma, P.; Karali, N.; Supuran, C.T. Novel 2-indolinones containing a sulfonamide moiety as selective inhibitors of candida beta-carbonic anhydrase enzyme. J. Enzym. Inhib. Med. Chem. 2019, 34, 528–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bua, S.; Osman, S.M.; Del Prete, S.; Capasso, C.; AlOthman, Z.; Nocentini, A.; Supuran, C.T. Click-tailed benzenesulfonamides as potent bacterial carbonic anhydrase inhibitors for targeting Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Vibrio cholerae. Bioorg. Chem. 2019, 86, 183–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bua, S.; Haapanen, S.; Kuuslahti, M.; Parkkila, S.; Supuran, C.T. Sulfonamide Inhibition Studies of a New beta-Carbonic Anhydrase from the Pathogenic Protozoan Entamoeba histolytica. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 3946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nocentini, A.; Bua, S.; Del Prete, S.; Heravi, Y.E.; Saboury, A.A.; Karioti, A.; Bilia, A.R.; Capasso, C.; Gratteri, P.; Supuran, C.T. Natural Polyphenols Selectively Inhibit beta-Carbonic Anhydrase from the Dandruff-Producing Fungus Malassezia globosa: Activity and Modeling Studies. ChemMedChem 2018, 13, 816–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nocentini, A.; Cadoni, R.; Dumy, P.; Supuran, C.T.; Winum, J.Y. Carbonic anhydrases from Trypanosoma cruzi and Leishmania donovani chagasi are inhibited by benzoxaboroles. J. Enzym. Inhib. Med. Chem. 2018, 33, 286–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishimori, I.; Onishi, S.; Takeuchi, H.; Supuran, C.T. The alpha and beta classes carbonic anhydrases from Helicobacter pylori as novel drug targets. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2008, 14, 622–630. [Google Scholar]

- Nishimori, I.; Minakuchi, T.; Maresca, A.; Carta, F.; Scozzafava, A.; Supuran, C.T. The beta-carbonic anhydrases from Mycobacterium tuberculosis as drug targets. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2010, 16, 3300–3309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strop, P.; Smith, K.S.; Iverson, T.M.; Ferry, J.G.; Rees, D.C. Crystal structure of the “cab”-type beta class carbonic anhydrase from the archaeon Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicum. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 10299–10305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, S.A.; Ferry, J.G.; Supuran, C.T. Inhibition of the archaeal beta-class (Cab) and gamma-class (Cam) carbonic anhydrases. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2007, 7, 901–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aspatwar, A.; Hammaren, M.; Koskinen, S.; Luukinen, B.; Barker, H.; Carta, F.; Supuran, C.T.; Parikka, M.; Parkkila, S. beta-CA-specific inhibitor dithiocarbamate Fc14-584B: A novel antimycobacterial agent with potential to treat drug-resistant tuberculosis. J. Enzym. Inhib. Med. Chem. 2017, 32, 832–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermelho, A.B.; Capaci, G.R.; Rodrigues, I.A.; Cardoso, V.S.; Mazotto, A.M.; Supuran, C.T. Carbonic anhydrases from Trypanosoma and Leishmania as anti-protozoan drug targets. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2017, 25, 1543–1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syrjanen, L.; Vermelho, A.B.; Rodrigues Ide, A.; Corte-Real, S.; Salonen, T.; Pan, P.; Vullo, D.; Parkkila, S.; Capasso, C.; Supuran, C.T. Cloning, characterization, and inhibition studies of a beta-carbonic anhydrase from Leishmania donovani chagasi, the protozoan parasite responsible for leishmaniasis. J. Med. Chem. 2013, 56, 7372–7381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapopoulou, A.; Lew, J.M.; Cole, S.T. The MycoBrowser portal: A comprehensive and manually annotated resource for mycobacterial genomes. Tuberculosis (Edinb.) 2011, 91, 8–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishimori, I.; Minakuchi, T.; Vullo, D.; Scozzafava, A.; Innocenti, A.; Supuran, C.T. Carbonic anhydrase inhibitors. Cloning, characterization, and inhibition studies of a new beta-carbonic anhydrase from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Med. Chem. 2009, 52, 3116–3120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minakuchi, T.; Nishimori, I.; Vullo, D.; Scozzafava, A.; Supuran, C.T. Molecular cloning, characterization, and inhibition studies of the Rv1284 beta-carbonic anhydrase from Mycobacterium tuberculosis with sulfonamides and a sulfamate. J. Med. Chem. 2009, 52, 2226–2232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carta, F.; Maresca, A.; Covarrubias, A.S.; Mowbray, S.L.; Jones, T.A.; Supuran, C.T. Carbonic anhydrase inhibitors. Characterization and inhibition studies of the most active beta-carbonic anhydrase from Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Rv3588c. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2009, 19, 6649–6654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suarez Covarrubias, A.; Larsson, A.M.; Hogbom, M.; Lindberg, J.; Bergfors, T.; Bjorkelid, C.; Mowbray, S.L.; Unge, T.; Jones, T.A. Structure and function of carbonic anhydrases from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 18782–18789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Covarrubias, A.S.; Bergfors, T.; Jones, T.A.; Hogbom, M. Structural mechanics of the pH-dependent activity of beta-carbonic anhydrase from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 4993–4999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, S.; Chen, J.; Dobos, K.M.; Bradbury, E.M.; Belisle, J.T.; Chen, X. Comprehensive proteomic profiling of the membrane constituents of a Mycobacterium tuberculosis strain. Mol. Cell. Proteom. 2003, 2, 1284–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenkrands, I.; King, A.; Weldingh, K.; Moniatte, M.; Moertz, E.; Andersen, P. Towards the proteome of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Electrophoresis 2000, 21, 3740–3756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betts, J.C.; Lukey, P.T.; Robb, L.C.; McAdam, R.A.; Duncan, K. Evaluation of a nutrient starvation model of Mycobacterium tuberculosis persistence by gene and protein expression profiling. Mol. Microbiol. 2002, 43, 717–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sassetti, C.M.; Boyd, D.H.; Rubin, E.J. Genes required for mycobacterial growth defined by high density mutagenesis. Mol. Microbiol. 2003, 48, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nienaber, L.; Cave-Freeman, E.; Cross, M.; Mason, L.; Bailey, U.M.; Amani, P.; A Davis, R.; Taylor, P.; Hofmann, A. Chemical probing suggests redox-regulation of the carbonic anhydrase activity of mycobacterial Rv1284. FEBS J. 2015, 282, 2708–2721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Malen, H.; Pathak, S.; Softeland, T.; de Souza, G.A.; Wiker, H.G. Definition of novel cell envelope associated proteins in Triton X-114 extracts of Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv. BMC Microbiol. 2010, 10, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelkar, D.S.; Kumar, D.; Kumar, P.; Balakrishnan, L.; Muthusamy, B.; Yadav, A.K.; Shrivastava, P.; Marimuthu, A.; Anand, S.; Sundaram, H.; et al. Proteogenomic analysis of Mycobacterium tuberculosis by high resolution mass spectrometry. Mol. Cell. Proteom. 2011, 10, M111.011627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camus, J.C.; Pryor, M.J.; Medigue, C.; Cole, S.T. Re-annotation of the genome sequence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv. Microbiology 2002, 148, 2967–2973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mawuenyega, K.G.; Forst, C.V.; Dobos, K.M.; Belisle, J.T.; Chen, J.; Bradbury, E.M.; Bradbury, A.R.; Chen, X. Mycobacterium tuberculosis functional network analysis by global subcellular protein profiling. Mol. Biol. Cell 2005, 16, 396–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiong, Y.; Chalmers, M.J.; Gao, F.P.; Cross, T.A.; Marshall, A.G. Identification of Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv integral membrane proteins by one-dimensional gel electrophoresis and liquid chromatography electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry. J. Proteome Res. 2005, 4, 855–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parikka, M.; Hammaren, M.M.; Harjula, S.K.; Halfpenny, N.J.; Oksanen, K.E.; Lahtinen, M.J.; Pajula, E.T.; Iivanainen, A.; Pesu, M.; Ramet, M. Mycobacterium marinum causes a latent infection that can be reactivated by gamma irradiation in adult zebrafish. PLoS Pathog. 2012, 8, e1002944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krogh, A.; Larsson, B.; von Heijne, G.; Sonnhammer, E.L. Predicting transmembrane protein topology with a hidden Markov model: Application to complete genomes. J. Mol. Biol. 2001, 305, 567–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bienert, S.; Waterhouse, A.; de Beer, T.A.; Tauriello, G.; Studer, G.; Bordoli, L.; Schwede, T. The SWISS-MODEL Repository-new features and functionality. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, D313–D319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowlett, R.S. Structure and catalytic mechanism of the beta-carbonic anhydrases. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2010, 1804, 362–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carta, F.; Maresca, A.; Scozzafava, A.; Vullo, D.; Supuran, C.T. Carbonic anhydrase inhibitors. Diazenylbenzenesulfonamides are potent and selective inhibitors of the tumor-associated isozymes IX and XII over the cytosolic isoforms I and II. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2009, 17, 7093–7099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maresca, A.; Carta, F.; Vullo, D.; Scozzafava, A.; Supuran, C.T. Carbonic anhydrase inhibitors. Inhibition of the Rv1284 and Rv3273 beta-carbonic anhydrases from Mycobacterium tuberculosis with diazenylbenzenesulfonamides. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2009, 19, 4929–4932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pacchiano, F.; Carta, F.; Vullo, D.; Scozzafava, A.; Supuran, C.T. Inhibition of beta-carbonic anhydrases with ureido-substituted benzenesulfonamides. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2011, 21, 102–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maresca, A.; Scozzafava, A.; Vullo, D.; Supuran, C.T. Dihalogenated sulfanilamides and benzolamides are effective inhibitors of the three beta-class carbonic anhydrases from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Enzym. Inhib. Med. Chem. 2013, 28, 384–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceruso, M.; Vullo, D.; Scozzafava, A.; Supuran, C.T. Sulfonamides incorporating fluorine and 1,3,5-triazine moieties are effective inhibitors of three beta-class carbonic anhydrases from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Enzym. Inhib. Med. Chem. 2014, 29, 686–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wani, T.V.; Bua, S.; Khude, P.S.; Chowdhary, A.H.; Supuran, C.T.; Toraskar, M.P. Evaluation of sulphonamide derivatives acting as inhibitors of human carbonic anhydrase isoforms I, II and Mycobacterium tuberculosis beta-class enzyme Rv3273. J. Enzym. Inhib. Med. Chem. 2018, 33, 962–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maresca, A.; Carta, F.; Vullo, D.; Supuran, C.T. Dithiocarbamates strongly inhibit the beta-class carbonic anhydrases from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Enzym. Inhib. Med. Chem. 2013, 28, 407–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, R.A.; Hofmann, A.; Osman, A.; Hall, R.A.; Muhlschlegel, F.A.; Vullo, D.; Innocenti, A.; Supuran, C.T.; Poulsen, S.A. Natural product-based phenols as novel probes for mycobacterial and fungal carbonic anhydrases. J. Med. Chem. 2011, 54, 1682–1692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cau, Y.; Mori, M.; Supuran, C.T.; Botta, M. Mycobacterial carbonic anhydrase inhibition with phenolic acids and esters: Kinetic and computational investigations. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2016, 14, 8322–8330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchieri, M.V.; Riafrecha, L.E.; Rodriguez, O.M.; Vullo, D.; Morbidoni, H.R.; Supuran, C.T.; Colinas, P.A. Inhibition of the beta-carbonic anhydrases from Mycobacterium tuberculosis with C-cinnamoyl glycosides: Identification of the first inhibitor with anti-mycobacterial activity. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2013, 23, 740–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maresca, A.; Vullo, D.; Scozzafava, A.; Manole, G.; Supuran, C.T. Inhibition of the beta-class carbonic anhydrases from Mycobacterium tuberculosis with carboxylic acids. J. Enzym. Inhib. Med. Chem. 2013, 28, 392–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scozzafava, A.; Mastrolorenzo, A.; Supuran, C.T. Antimycobacterial activity of 9-sulfonylated/sulfenylated-6-mercaptopurine derivatives. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2001, 11, 1675–1678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, B.K.; Colvin, C.J.; Needle, D.B.; Mba Medie, F.; Champion, P.A.; Abramovitch, R.B. The Carbonic Anhydrase Inhibitor Ethoxzolamide Inhibits the Mycobacterium tuberculosis PhoPR Regulon and Esx-1 Secretion and Attenuates Virulence. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2015, 59, 4436–4445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, B.K.; Abramovitch, R.B. Small Molecules That Sabotage Bacterial Virulence. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2017, 38, 339–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Rose, S.J.; Babrak, L.M.; Bermudez, L.E. Mycobacterium avium Possesses Extracellular DNA that Contributes to Biofilm Formation, Structural Integrity, and Tolerance to Antibiotics. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0128772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, S.J.; Bermudez, L.E. Identification of Bicarbonate as a Trigger and Genes Involved with Extracellular DNA Export in Mycobacterial Biofilms. mBio 2016, 7, e01597-16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| CAs | Gene ID | Protein | Kcat (S−1) | Kcat/Km (M−1S−1) | KI (nM) a | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mtb β-CA1 | Rv1284 | 163 aa | 3.9 × 105 | 3.7 × 107 | 480 | [34] |

| Mtb β-CA2 | Rv3588c | 207 aa | 9.8 × 105 | 9.3 × 107 | 9.8 | [35] |

| Mtb β-CA3 | Rv3273 | 764 aa b | 4.3 × 105 | 4.0 × 107 | 104 | [33] |

| hCA II | CA2 | 260 aa | 1.4 × 106 | 1.5 × 108 | 12 | [35] |

| CA Inhibitor | Mycobacterium | Group | Effect on the Bacterium | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ethoxzolamide | Mtb | MTC | Inhibits PhoPR regulon, attenuates virulence | [64] |

| Ethoxzolamide | M. avium | NTM | Reduces the transport of eDNA and biofilm formation | [67] |

| Dithiocarbamate | Mmar | NTM | Impairs growth of Mmar in zebrafish larvae | [29] |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Aspatwar, A.; Kairys, V.; Rala, S.; Parikka, M.; Bozdag, M.; Carta, F.; Supuran, C.T.; Parkkila, S. Mycobacterium tuberculosis β-Carbonic Anhydrases: Novel Targets for Developing Antituberculosis Drugs. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 5153. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms20205153

Aspatwar A, Kairys V, Rala S, Parikka M, Bozdag M, Carta F, Supuran CT, Parkkila S. Mycobacterium tuberculosis β-Carbonic Anhydrases: Novel Targets for Developing Antituberculosis Drugs. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2019; 20(20):5153. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms20205153

Chicago/Turabian StyleAspatwar, Ashok, Visvaldas Kairys, Sangeetha Rala, Mataleena Parikka, Murat Bozdag, Fabrizio Carta, Claudiu T. Supuran, and Seppo Parkkila. 2019. "Mycobacterium tuberculosis β-Carbonic Anhydrases: Novel Targets for Developing Antituberculosis Drugs" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 20, no. 20: 5153. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms20205153