The Effects of High Fat Diet-Induced Stress on Olfactory Sensitivity, Behaviors, and Transcriptional Profiling in Drosophila melanogaster

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results

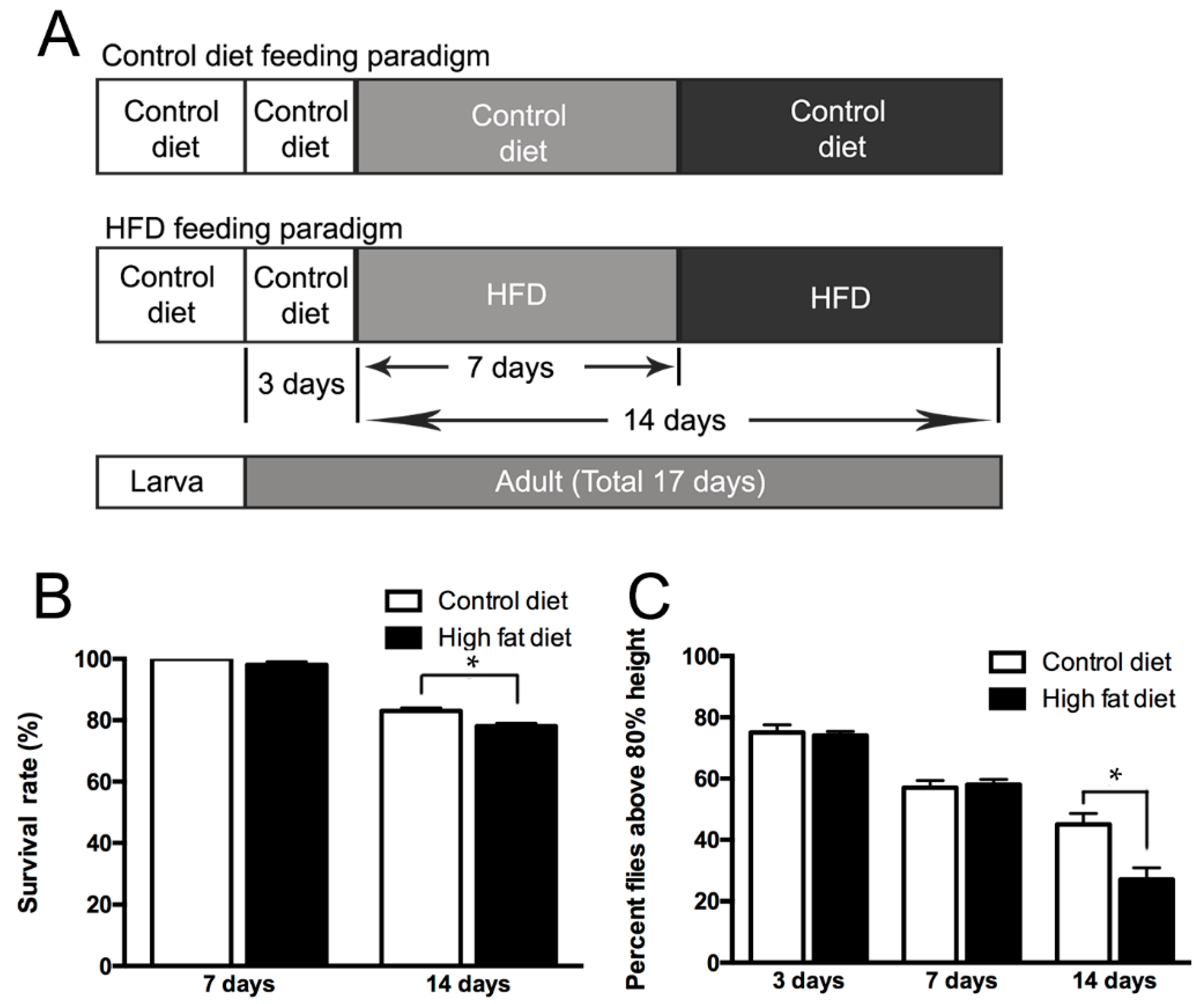

2.1. Life Span and Climbing Abilities of Flies Fed with HFD

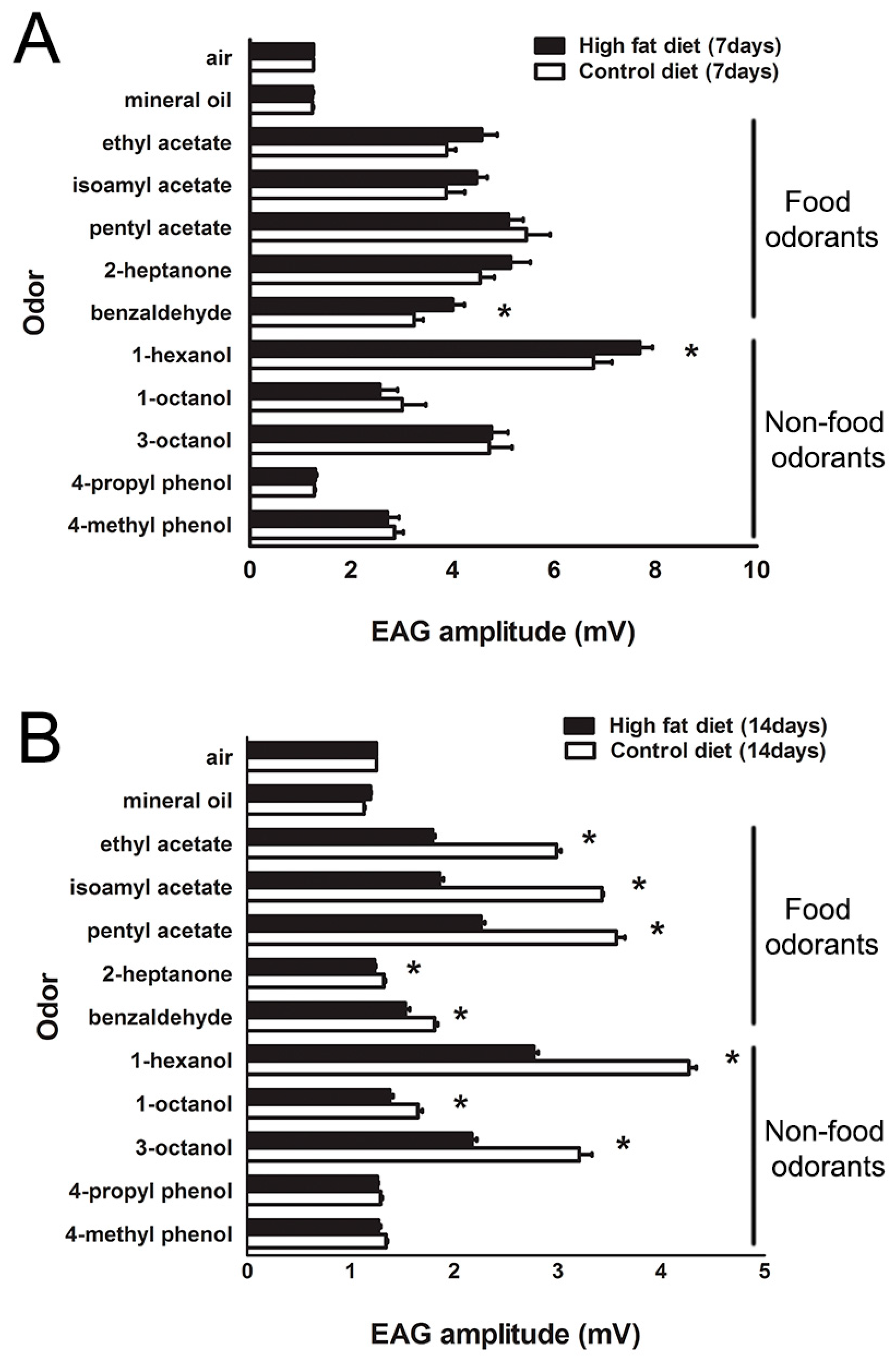

2.2. Modification of Olfactory Sensitivity by HFD Treatment

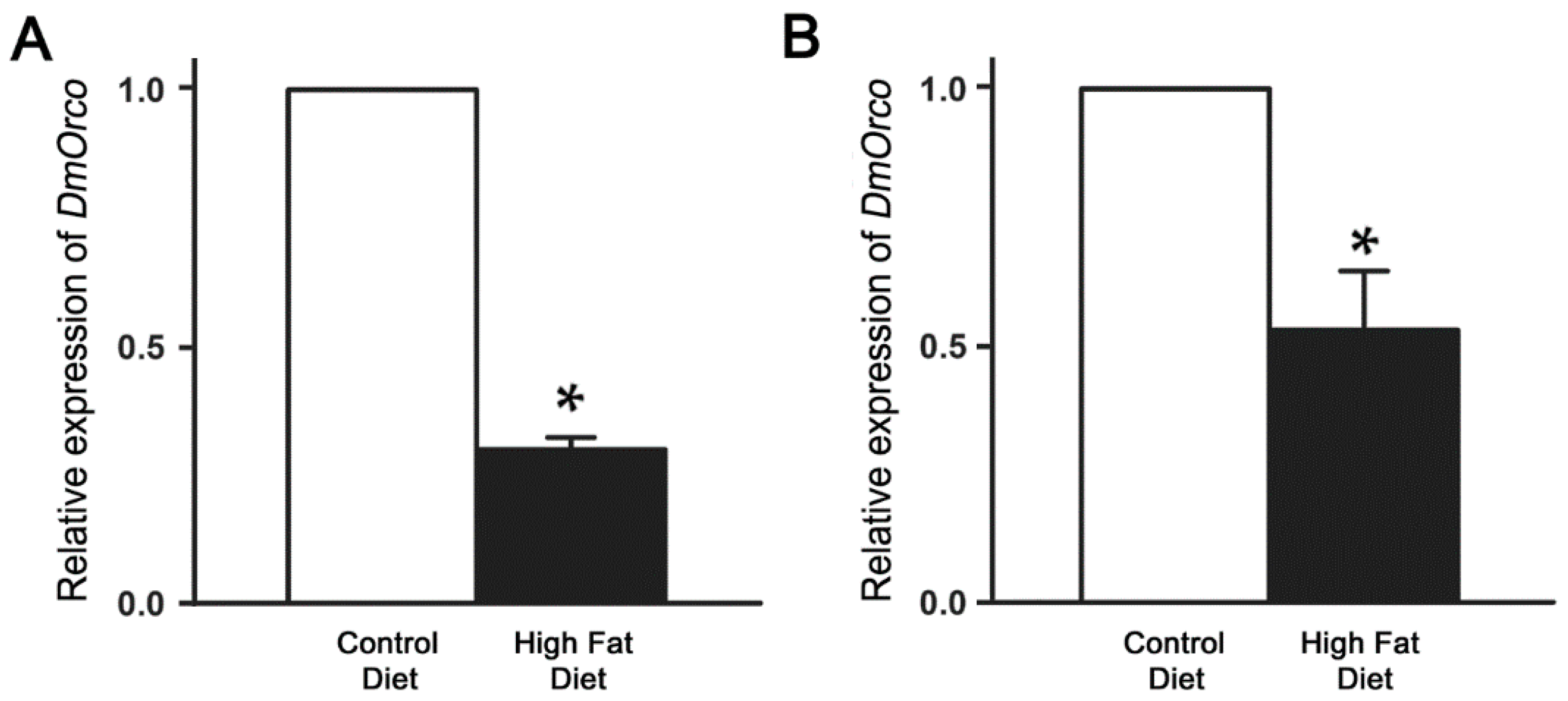

2.3. Reduction of DmOrco Gene Expression in the Fly Antenna after HFD Treatment

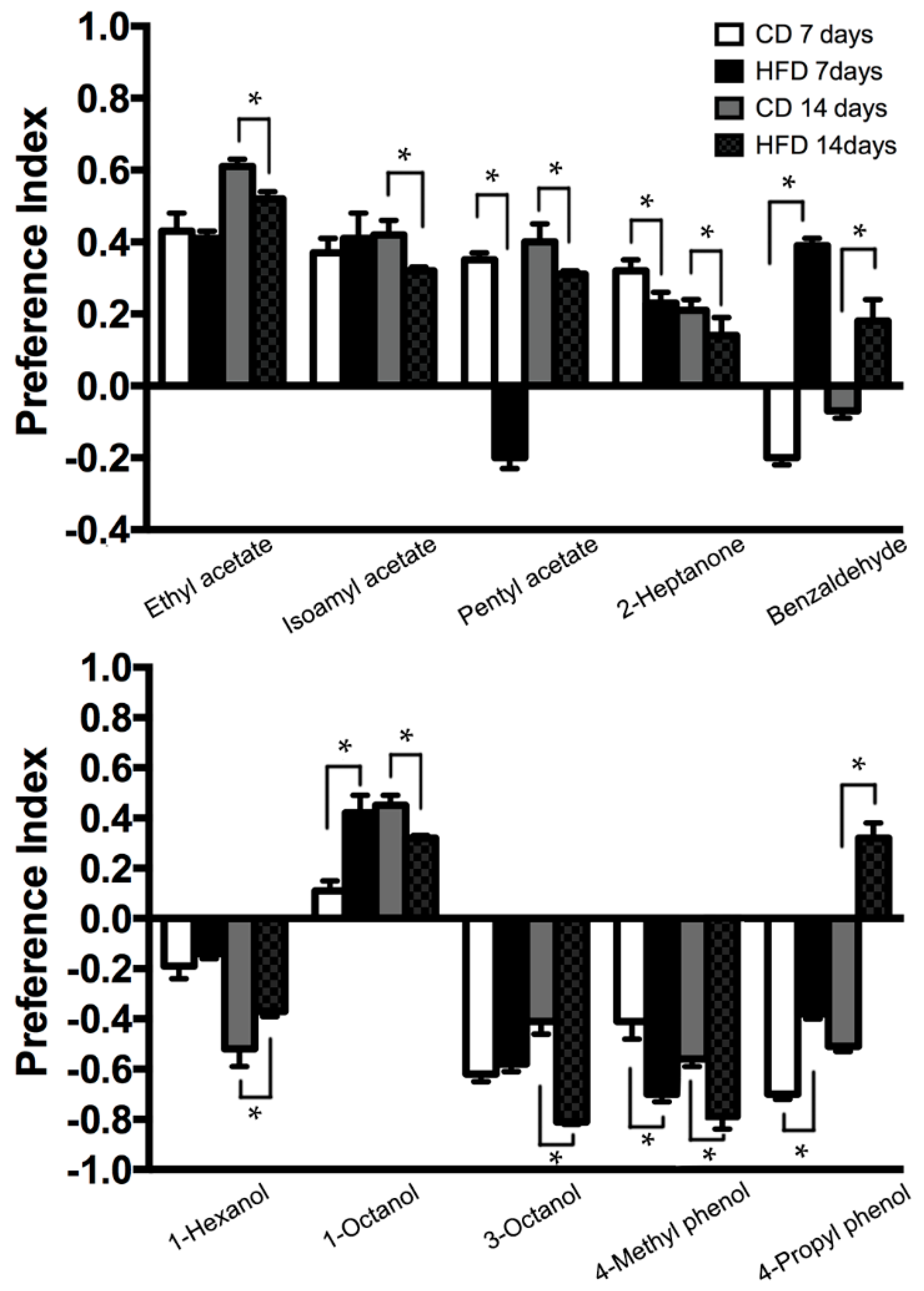

2.4. Modification of Odorant Choice Behaviors by HFD Treatment

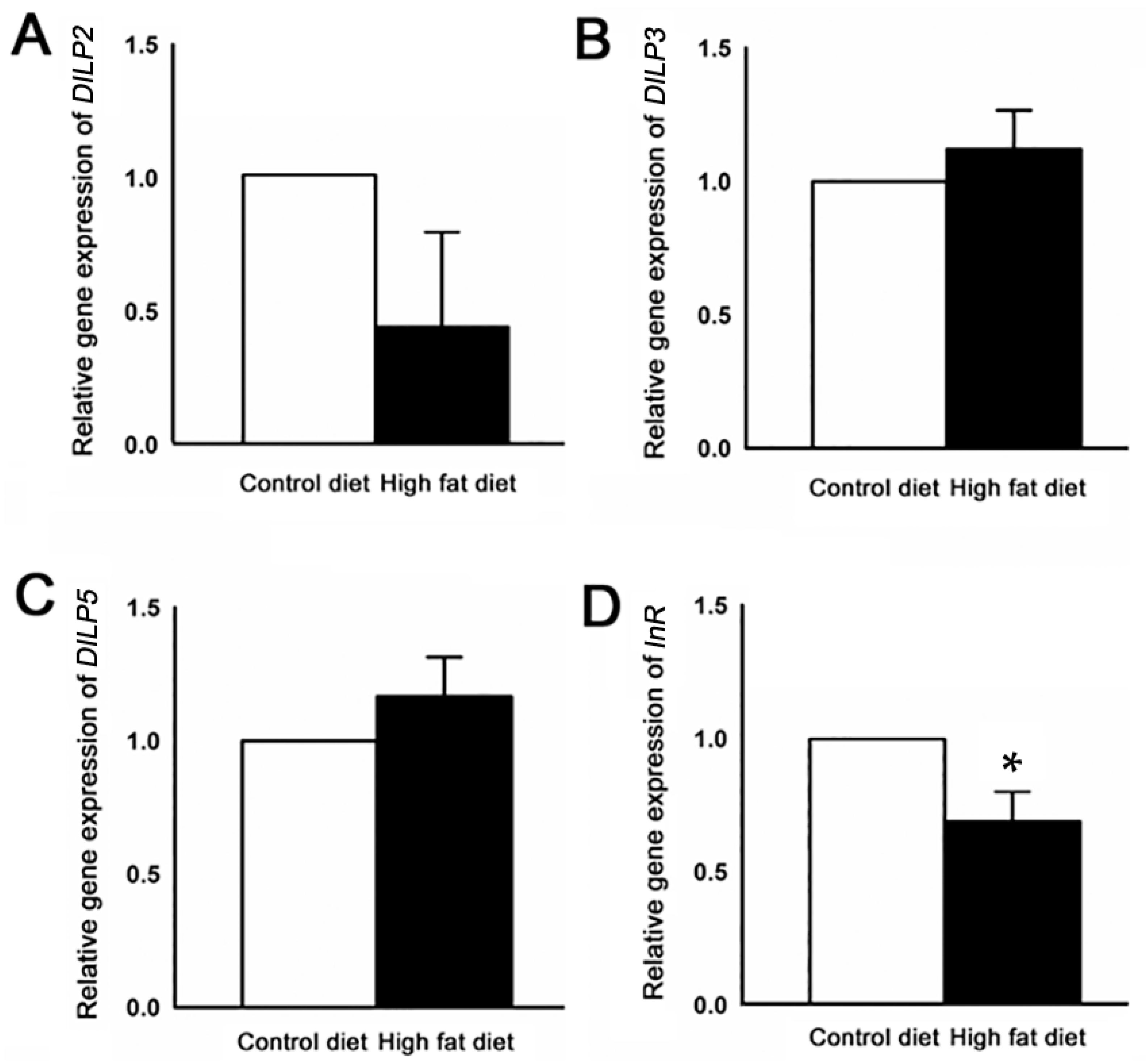

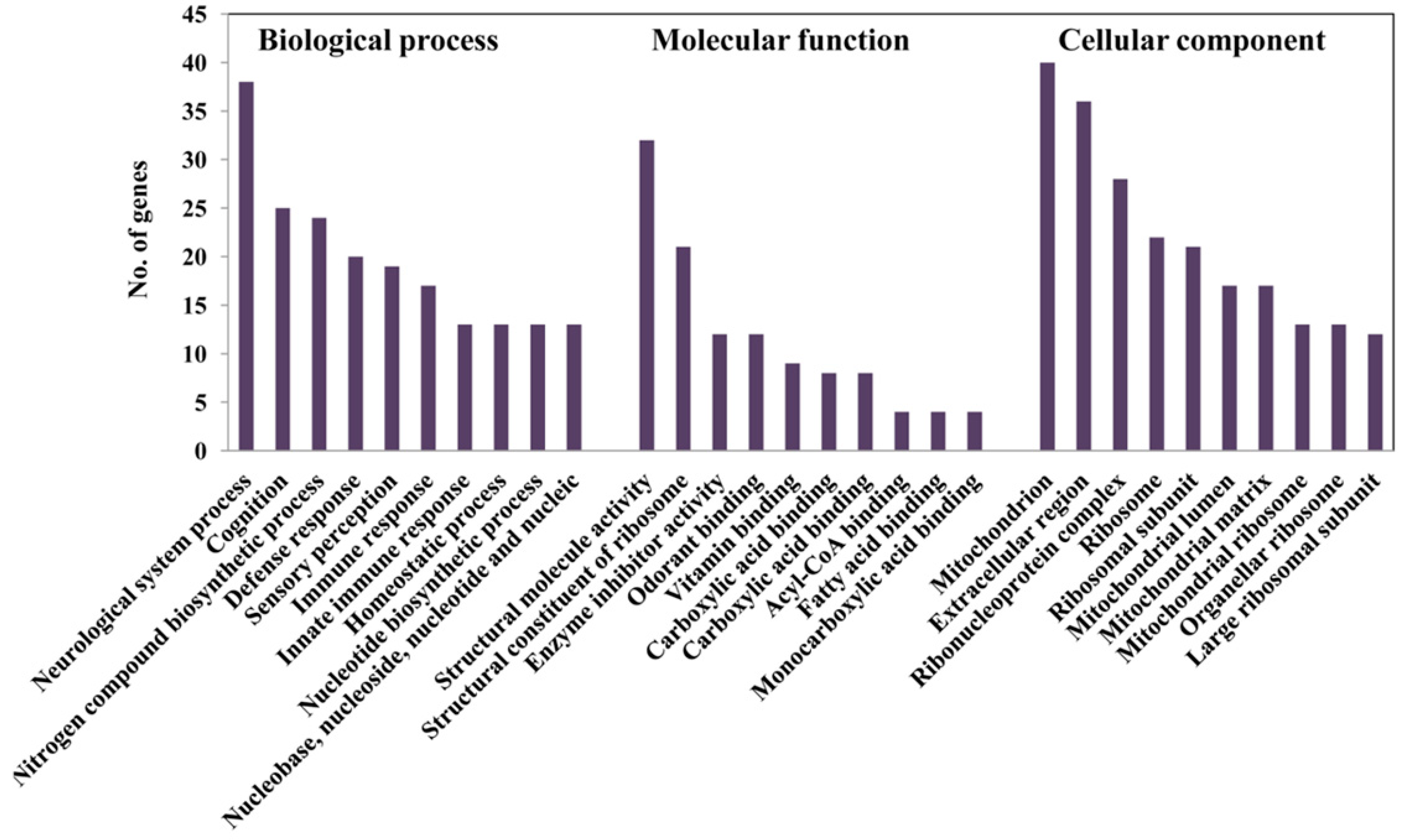

2.5. Alteration of Gene Expression Profiles by HFD Treatment

3. Discussion

A High-Fat Diet Leads to Olfactory Dysfunction in Homeostatic Processing in Drosophila

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Drosophila Stocks and Diet Treatment

4.2. Life Span and Climbing Assays

4.3. Odor Stimulation

4.4. Electrophysiological Recordings

4.5. Quantitative RT-PCR

4.6. Behavioral Assay

4.7. Analysis for Differentially Expressed Genes (DEG) and Gene Ontology of HFD-Fed Flies

4.8. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rajan, A.; Perrimon, N. Drosophila as a model for interorgan communication: Lessons from studies on energy homeostasis. Dev. Cell 2011, 21, 29–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajan, A.; Perrimon, N. Of flies and men: Insights on organismal metabolism from fruit flies. BMC Biol. 2013, 11, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Baker, K.D.; Thummel, C.S. Diabetic larvae and obese flies-emerging studies of metabolism in Drosophila. Cell Metab. 2007, 6, 257–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skorupa, D.A.; Dervisefendic, A.; Zwiener, J.; Pletcher, S.D. Dietary composition specifies consumption, obesity, and lifespan in Drosophila melanogaster. Aging Cell 2008, 7, 478–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gale, S.M.; Castracane, V.D.; Mantzoros, C.S. Energy homeostasis, obesity and eating disorders: Recent advances in endocrinology. J. Nutr. 2004, 134, 295–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trinh, I.; Boulianne, G.L. Modeling obesity and its associated disorders in Drosophila. Physiology 2013, 28, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teleman, A.A.; Ratzenbock, I.; Oldham, S. Drosophila: A model for understanding obesity and diabetic complications. Exp. Clin. Endocrinol. Diabetes 2012, 120, 184–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, D.A.; Moskowitz, H.R.; Campbell, R.G. Taste and olfaction in human obesity. Physiol. Behav. 1977, 19, 335–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Withcher, D. Metabolic regulation and behavior: How hunger produces arousal-an insect study. Endocr. Metab. Immune 2007, 7, 304–310. [Google Scholar]

- Crowley, V.E. Overview of human obesity and central mechanisms regulating energy homeostasis. Ann. Clin. Biochem. 2008, 45, 245–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melcher, C.; Bader, R.; Pankratz, M.J. Amino acids, taste circuits, and feeding behavior in Drosophila: Towards understanding the psychology of feeding in flies and man. J. Endocrinol. 2007, 192, 467–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herrero, P. Fruit fly behavior in response to chemosensory signals. Peptides 2012, 38, 228–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sato, K.; Touhara, K. Insect olfaction: Receptors, signal transduction, and behavior. Results Probl. Cell Differ. 2009, 47, 121–138. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Carlson, J.R. Olfaction in Drosophila: From odor to behavior. Trends Genet. 1996, 12, 175–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacroix, M.C.; Badonnel, K.; Meunier, N.; Tan, F.; Schlegel-Le Poupon, C.; Durieux, D.; Monnerie, R.; Baly, C.; Congar, P.; Salesse, R.; et al. Expression of insulin system in the olfactory epithelium: First approaches to its role and regulation. J. Neuroendocrinol. 2008, 20, 1176–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vosshall, L.B. Into the mind of a fly. Nature 2007, 450, 193–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Diop, S.B.; Bodmer, R. Drosophila as a model to study the genetic mechanisms of obesity-associated heart dysfunction. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2012, 16, 966–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Root, C.M.; Ko, K.I.; Jafari, A.; Wang, J.W. Presynaptic facilitation by neuropeptide signaling mediates odor-driven food search. Cell 2011, 145, 133–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palouzier-Paulignan, B.; Lacroix, M.C.; Aime, P.; Baly, C.; Caillol, M.; Congar, P.; Julliard, A.K.; Tucker, K.; Fadool, D.A. Olfaction under metabolic influences. Chem. Senses 2012, 37, 769–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nassel, D.R.; Winther, A.M. Drosophila neuropeptides in regulation of physiology and behavior. Prog. Neurobiol. 2010, 92, 42–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Libert, S.; Zwiener, J.; Chu, X.; Vanvoorhies, W.; Roman, G.; Pletcher, S.D. Regulation of Drosophila life span by olfaction and food-derived odors. Science 2007, 315, 1133–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, X.; Seeberger, J.; Alberico, T.; Wang, C.; Wheeler, C.T.; Schauss, A.G.; Zou, S. Acai palm fruit (Euterpe oleracea Mart.) pulp improves survival of flies on a high fat diet. Exp. Gerontol. 2010, 45, 243–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyd, O.; Weng, P.; Sun, X.; Alberico, T.; Laslo, M.; Obenland, D.M.; Kern, B.; Zou, S. Nectarine promotes longevity in Drosophila melanogaster. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2011, 50, 1669–1678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Birse, R.T.; Choi, J.; Reardon, K.; Rodriguez, J.; Graham, S.; Diop, S.; Ocorr, K.; Bodmer, R.; Oldham, S. High-fat-diet-induced obesity and heart dysfunction are regulated by the TOR pathway in Drosophila. Cell Metab. 2010, 12, 533–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leinwand, S.G.; Chalasani, S.H. Olfactory networks: From sensation to perception. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2011, 21, 806–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riveron, J.; Boto, T.; Alcorta, E. Transcriptional basis of the acclimation to high environmental temperature at the olfactory receptor organs of Drosophila melanogaster. BMC Genomics 2013, 14, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takase, K.; Tsuneoka, Y.; Oda, S.; Kuroda, M.; Funato, H. High-fat diet feeding alters olfactory-, social-, and reward-related behaviors of mice independent of obesity. Obesity 2016, 24, 886–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Feinstein, P.; Bozza, T.; Rodriguez, I.; Vassalli, A.; Mombaerts, P. Axon guidance of mouse olfactory sensory neurons by odorant receptor sand the β2 adrenergic receptor. Cell 2004, 117, 833–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barish, S.; Volkan, P.C. Mechanisms of olfactory receptorneuron specification in Drosophila. WIREs. Dev. Biol. 2015, 4, 609–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gregor, M.F.; Hotamisligil, G. Inflammatory mechanisms in obesity. Ann. Rev. Immunol. 2011, 29, 415–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moraes, J.C.; Coope, A.; Morari, J.; Cintra, D.E.; Roman, E.A.; Pauli, J.R.; Romanatto, T.; Carvalheira, J.B.; Oliveira, A.L.R.; Saad, M.J.; et al. High-fat diet induces apoptosis of hypothalamic neurons. PLoS ONE 2009, 4, e5045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farhadian, S.F.; Suarez-Farinas, M.; Cho, C.E.; Pellegrino, M.; Vosshall, L.B. Post-fasting olfactory, transcriptional, and feeding responses in Drosophila. Physiol. Behav. 2012, 105, 544–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thiebaud, N.; Johnson, M.C.; Butler, J.L.; Bell, G.A.; Ferguson, K.L.; Fadool, A.R.; Fadool, J.C.; Gale, A.M.; Gale, D.S.; Fadool, D.A. Hyperlipidemic diet causes loss of olfactory sensory neurons, reduces olfactory discrimination, and disrupts odor-reversal learning. J. Neurosci. 2014, 34, 6970–6984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fadool, D.A.; Tucker, K.; Pedarzani, P. Mitral cells of the olfactory bulb perform metabolic sensing and are disrupted by obesity at the level of the Kv1.3 ion channel. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e24921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Musselman, L.P.; Fink, J.L.; Narzinski, K.; Ramachandran, P.V.; Hathiramani, S.S.; Cagan, R.L.; Baranski, T.J. A high-sugar diet produces obesity and insulin resistance in wild-type Drosophila. Dis. Mod. Mech. 2011, 4, 842–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heinrichsen, E.T.; Haddad, G.G. Role of high-fat diet in stress response of Drosophila. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e42587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris, S.N.; Coogan, C.; Chamseddin, K.; Fernandez-Kim, S.O.; Kolli, S.; Keller, J.N.; Bauer, J.H. Development of diet-induced insulin resistance in adult Drosophila melanogaster. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2012, 1822, 1230–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benton, R. On the ORigin of smell: Odorant receptors in insects. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2006, 63, 1579–1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, K.S.; Kwon, O.Y.; Lee, J.H.; Kwon, K.; Min, K.J.; Jung, S.A.; Kim, A.K.; You, K.H.; Tatar, M.; Yu, K. Drosophila short neuropeptide F signalling regulates growth by ERK-mediated insulin signalling. Nat. Cell Biol. 2008, 10, 468–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winther, A.M.; Acebes, A.; Ferrus, A. Tachykinin-related peptides modulate odor perception and locomotor activity in Drosophila. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 2006, 31, 399–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kahsai, L.; Kapan, N.; Dircksen, H.; Winther, A.M.; Nassel, D.R. Metabolic stress responses in Drosophila are modulated by brain neurosecretory cells that produce multiple neuropeptides. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e11480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carlsson, M.A.; Diesner, M.; Schachtner, J.; Nassel, D.R. Multiple neuropeptides in the Drosophila antennal lobe suggest complex modulatory circuits. J. Comp. Neurol. 2010, 518, 3359–3380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carlsson, M.A.; Enell, L.E.; Nassel, D.R. Distribution of short neuropeptide F and its receptor in neuronal circuits related to feeding in larval Drosophila. Cell Tissue Res. 2013, 353, 511–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Störtkuhl, K.F.; Kettler, R.; Fischer, S.; Hovemann, B. An increased receptive field of olfactory receptor Or43a in the antennal lobe of Drosophila reduces benzaldehyde-driven avoidance behavior. Chem. Senses 2005, 30, 81–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, M.S.; Repp, A.; Smith, D.P. LUSH odorant-binding protein mediates chemosensory responses to alcohols in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics 1998, 150, 711–721. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Xu, P.; Atkinson, R.; Jones, D.N.M.; Smith, D.P. Drosophila OBP LUSH is required for activity of pheromone-sensitive neurons. Neuron 2005, 45, 193–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tom, W.; de Bruyne, M.; Haehnel, M.; Carlson, J.R.; Ray, A. Disruption of olfactory receptor neuron patterning in Scutoid mutant Drosophila. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 2011, 46, 252–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, S.H.; Lee, K.S.; Kwak, S.J.; Kim, A.K.; Bai, H.; Jung, M.S.; Kwon, O.Y.; Song, W.J.; Tatar, M.; Yu, K. Minibrain/Dyrk1a regulates food intake through the Sir2-FOXO-sNPF/NPY pathway in Drosophila and mammals. PLoS Genet. 2012, 8, e1002857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, S.; Ai, M.; Shin, S.A.; Suh, G.S. Dedicated olfactory neurons mediating attraction behavior to ammonia and amines in Drosophila. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, E1321–E1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trapnell, C.; Roberts, A.; Goff, L.; Pertea, G.; Kim, D.; Kelley, D.R.; Pimentel, H.; Salzberg, S.L.; Rinn, J.L.; Pachter, L. Differential gene and transcript expression analysis of RNA-seq experiments with TopHat and Cufflinks. Nat. Protoc. 2012, 7, 562–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

| Gene ID | Functional Description | Gene ID | Functional Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Upregulated | Downregulated | ||

| FBtr0086664 | IM2 | FBtr0025595 | Akhr |

| FBtr0028381 | Decay | FBgn0052523 | Serine protease |

| FBtr0070099 | Cyp4g1 | FBgn0026389 | Or43a |

| FBtr0100231 | RpL41 | FBtr0082607 | GstD1 |

| FBtr0086662 | IM1 | FBtr0073062 | Drsl5 |

| FBtr0074176 | sun | FBgn0053532 | Lectin-37Da |

| FBtr0088035 | eEF1α1 | FBgn0037324 | Orco |

| FBtr0073468 | antdh | FBtr0085805 | RpL6 |

| FBtr0087992 | Cyp6g1 | FBgn0036926 | CG7646 |

| FBgn0001179 | Hay | FBgn0026385 | Or47b |

| FBtr0072924 | RpL8 | FBtr0074969 | lush |

| FBtr0307212 | CG16978 | FBtr0079455 | Obp28a |

| FBtr0086477 | Obp56d | FBtr0076229 | Sod1 |

| FBtr0072185 | RpL39 | FBgn0036009 | Or67a |

| FBgn0013343 | Syntaxin-1A | FBtr0081427 | CG9336 |

| FBgn0035505 | Teh2 | FBtr0081855 | COX7A |

| FBtr0113742 | RpL15 | FBtr0086292 | Obp57c |

| FBtr0086216 | CG18067 | FBtr0087494 | CG30197 |

| FBtr0081597 | Obp84a | FBgn0038798 | Or92a |

| FBgn0033483 | Egr | FBgn0034474 | Obp56g |

| FBtr0080306 | CG6770 | FBtr0071135 | RpS6 |

| FBtr0265464 | Traf6 | FBtr0078769 | RpL35A |

| FBtr0084410 | RpS3 | FBgn0034475 | Obp56h |

| FBtr0300322 | Sfp84E | FBgn0033789 | CG13324 |

| FBtr0085463 | Obp99c | FBgn0038203 | Or88a |

| FBgn0053502 | CG33502 | FBtr0088525 | RpL31 |

| FBtr0070983 | RpL17 | FBtr0082370 | RpS25 |

| FBtr0087747 | CG4716 | FBtr0086672 | GstE4 |

| FBgn0041625 | Or65a | FBgn0028416 | Met75Ca |

| FBgn0036078 | Or67c | FBtr0071935 | RpS24 |

| FBtr0071096 | RpS14b | FBtr0075217 | CG7630 |

| FBtr0075884 | RpS4 | FBgn0032008 | CG14277 |

| FBtr0300635 | CG42502 | FBtr0070290 | sta |

| FBtr0087105 | RpLP2 | FBtr0307166 | Obp19a |

| FBtr0072805 | RpL23A | FBtr0302899 | CG6503 |

| FBtr0305965 | CG14661 | FBtr0073097 | RpL28 |

| FBtr0075839 | Nplp2 | FBtr0078656 | Obp83a |

| FBtr0075955 | Obp69a | FBtr0072164 | EbpIII |

| FBtr0075066 | RpL26 | FBtr0112740 | ND-MWFE |

| FBtr0077470 | RpL40 | FBtr0071392 | CG9691 |

| FBtr0076423 | RpS9 | FBtr0307366 | lncRNA:CR34335 |

| FBtr0082962 | His4r | FBtr040734 | CG15065 |

| FBtr0081920 | CG8369 | FBtr0077922 | a5 |

| FBtr0072173 | eEF5 | FBtr0040735 | CG16386 |

| FBtr0071360 | RpS28b | FBtr0083969 | RpS30 |

| FBtr0076273 | CG6409 | FBtr0075290 | a10 |

| FBtr0078655 | Obp83b | FBtr0300828 | RpS15Aa |

| FBtr0300321 | Os-C | FBtr0076032 | RpL10Ab |

| FBtr0332183 | OS9 |

| Gene ID | Functional Description | Gene ID | Functional Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Upregulated | Downregulated | ||

| FBgn0026398 | Or22a | FBgn0037324 | Orco |

| FBgn0026397 | Or22b | FBgn0030204 | Or9a |

| FBgn0041625 | Or65a | FBgn0041626 | Or19a |

| FBgn0036078 | Or67c | FBgn0062565 | Or19b |

| FBgn0037399 | Or83c | FBgn0026395 | Or23a |

| FBgn0037685 | Or85f | FBgn0026392 | Or33a |

| FBgn0026391 | Or33b | ||

| FBgn0028946 | Or35a | ||

| FBgn0033041 | Or42a | ||

| FBgn0033043 | Or42b | ||

| FBgn0026389 | Or43a | ||

| FBgn0033404 | Or45a | ||

| FBgn0026386 | Or47a | ||

| FBgn0026385 | Or47b | ||

| FBgn0028963 | Or49b | ||

| FBgn0034473 | Or56a | ||

| FBgn0041624 | Or65b | ||

| FBgn0041623 | Or65c | ||

| FBgn0036009 | Or67a | ||

| FBgn0036019 | Or67b | ||

| FBgn0041622 | Or69a | ||

| FBgn0037576 | Or85a | ||

| FBgn0026399 | Or85e | ||

| FBgn0038203 | Or88a | ||

| FBgn0038798 | Or92a | ||

| FBgn0039551 | Or98a | ||

| FBgn0038798 | Or92a |

| Gene ID | Functional Description | Gene ID | Functional description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Upregulated | Downregulated | ||

| FBgn0050067 | Obp50a | FBgn0030103 | Obp8a |

| FBgn0033931 | Obp50e | FBgn0030985 | Obp18a |

| FBgn0034468 | Obp56a | FBgn0031109 | Obp19a |

| FBgn0034470 | Obp56d | FBgn0031110 | Obp19b |

| FBtr0075955 | Obp69a | FBgn0031111 | Obp19c |

| FBgn0046876 | Obp83ef | FBgn0050052 | Obp49a |

| FBtr0078655 | Obp83b | FBgn0043530 | Obp51a |

| FBtr0081597 | Obp84a | FBgn0046879 | Obp56c |

| FBgn0039682 | Obp99c | FBgn0034471 | Obp56e |

| FBgn0043533 | Obp56f | ||

| FBgn0034474 | Obp56g | ||

| FBgn0034475 | Obp56h | ||

| FBgn0034509 | Obp57c | ||

| FBgn0050145 | Obp57e | ||

| FBgn0034768 | Obp58b | ||

| FBgn0034769 | Obp58c | ||

| FBgn0034770 | Obp58d | ||

| FBgn0034766 | Obp59a | ||

| FBgn0046875 | Obp83a | ||

| FBgn0039685 | Obp99b | ||

| FBgn0039684 | Obp99d |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jung, J.; Kim, D.-I.; Han, G.-Y.; Kwon, H.W. The Effects of High Fat Diet-Induced Stress on Olfactory Sensitivity, Behaviors, and Transcriptional Profiling in Drosophila melanogaster. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 2855. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms19102855

Jung J, Kim D-I, Han G-Y, Kwon HW. The Effects of High Fat Diet-Induced Stress on Olfactory Sensitivity, Behaviors, and Transcriptional Profiling in Drosophila melanogaster. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2018; 19(10):2855. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms19102855

Chicago/Turabian StyleJung, Jewon, Dong-In Kim, Gi-Youn Han, and Hyung Wook Kwon. 2018. "The Effects of High Fat Diet-Induced Stress on Olfactory Sensitivity, Behaviors, and Transcriptional Profiling in Drosophila melanogaster" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 19, no. 10: 2855. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms19102855