DNA Damage and Pulmonary Hypertension

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. DNA Damage and Repair

2.1. Single-Strand Damage

2.2. Double-Strand Breaks

3. DNA Damage in Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension

3.1. Evidences DNA Damage in PAH

3.2. Inflammation

3.3. Oxidative Stress

3.4. Anorexigen Drugs and Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors

3.5. Alkylating Chemotherapies

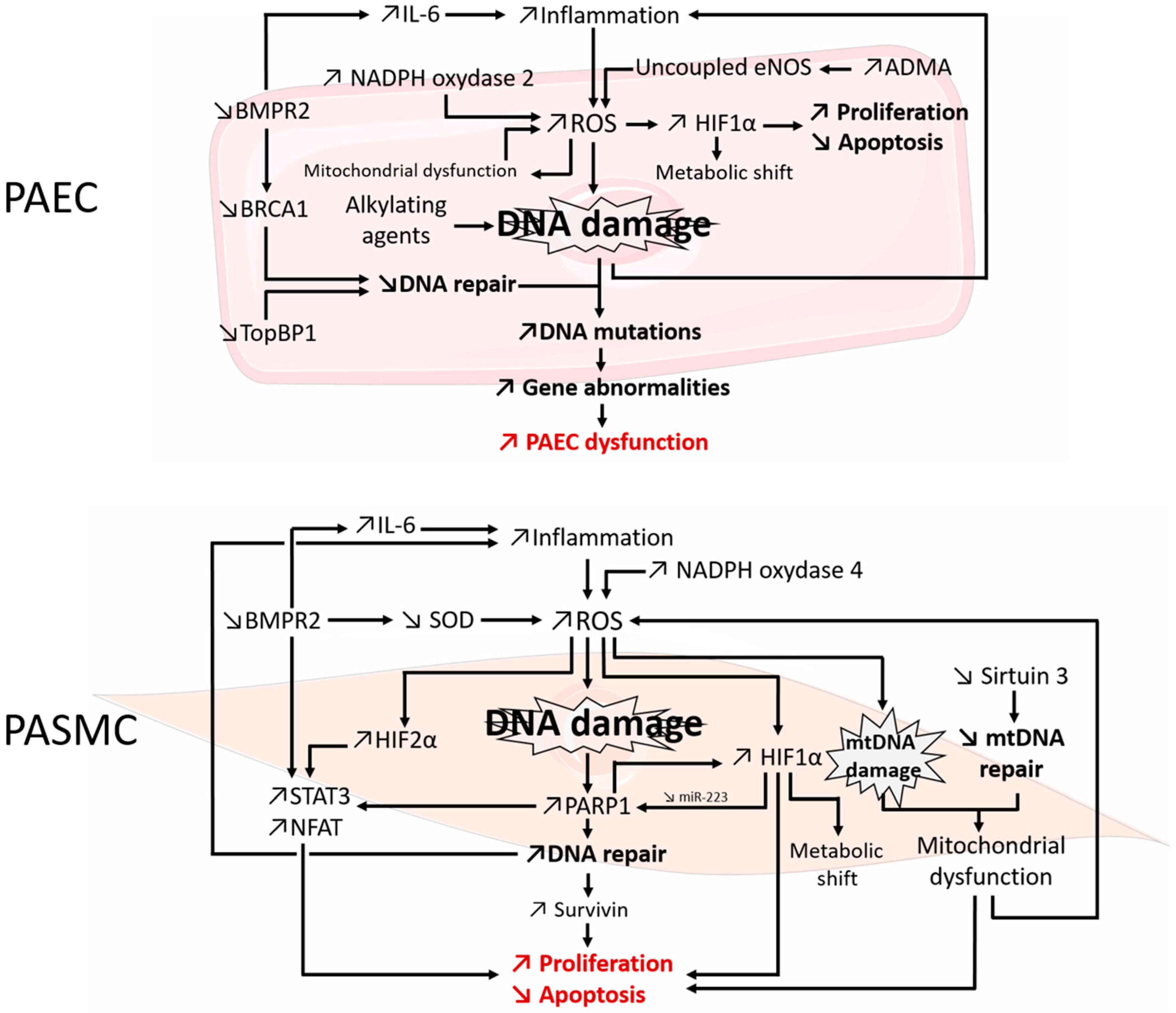

4. DNA Repair Mechanisms in PAH Pathogenesis

5. DNA Damage: Beyond the Nucleus

6. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ADMA | asymmetric dimethyl-l-arginine |

| AP site | apurinic/apyrimidinic site; abasic site |

| BER | base excision repair |

| BRCA1 | breast cancer 1 |

| DDR | DNA-damage response |

| DSB | DNA double strand breaks |

| EC | endothelial cell |

| HR | homologous recombination |

| MMEJ | microhomology-mediated end joining |

| MMR | mismatch repair |

| NER | nucleotide excision repair |

| NHEJ | non-homologous end joining |

| PAEC | pulmonary artery endothelial cell |

| PAH | pulmonary arterial hypertension |

| PARP1 | poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase 1 |

| PASMC | pulmonary artery smooth muscle cell |

| PH | pulmonary hypertension |

| RNS | reactive nitrogen species |

| ROS | reactive oxygen species |

| SSB | DNA single-strand break |

References

- Hoeper, M.M.; Humbert, M.; Souza, R.; Idrees, M.; Kawut, S.M.; Sliwa-Hahnle, K.; Jing, Z.-C.; Gibbs, J.S.R. A global view of pulmonary hypertension. Lancet Respir. Med. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoeper, M.M.; McLaughlin, V.V.; Dalaan, A.M.A.; Satoh, T.; Galiè, N. Treatment of pulmonary hypertension. Lancet Respir. Med. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuder, R.M.; Archer, S.L.; Dorfmüller, P.; Erzurum, S.C.; Guignabert, C.; Michelakis, E.; Rabinovitch, M.; Schermuly, R.; Stenmark, K.R.; Morrell, N.W. Relevant issues in the pathology and pathobiology of pulmonary hypertension. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2013, 62, D4–D12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Humbert, M.; Montani, D.; Perros, F.; Dorfmüller, P.; Adnot, S.; Eddahibi, S. Endothelial cell dysfunction and cross talk between endothelium and smooth muscle cells in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Vascul. Pharmacol. 2008, 49, 113–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rabinovitch, M. Molecular pathogenesis of pulmonary arterial hypertension. J. Clin. Investig. 2012, 122, 4306–4313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen-Kaminsky, S.; Hautefort, A.; Price, L.; Humbert, M.; Perros, F. Inflammation in pulmonary hypertension: What we know and what we could logically and safely target first. Drug Discov. Today 2014, 19, 1251–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryan, J.; Dasgupta, A.; Huston, J.; Chen, K.-H.; Archer, S.L. Mitochondrial dynamics in pulmonary arterial hypertension. J. Mol. Med. 2015, 93, 229–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Potus, F.; Ruffenach, G.; Dahou, A.; Thebault, C.; Breuils-Bonnet, S.; Tremblay, È.; Nadeau, V.; Paradis, R.; Graydon, C.; Wong, R.; et al. Downregulation of MicroRNA-126 Contributes to the Failing Right Ventricle in Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. Circulation 2015, 132, 932–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Potus, F.; Malenfant, S.; Graydon, C.; Mainguy, V.; Tremblay, È.; Breuils-Bonnet, S.; Ribeiro, F.; Porlier, A.; Maltais, F.; Bonnet, S.; et al. Impaired angiogenesis and peripheral muscle microcirculation loss contribute to exercise intolerance in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2014, 190, 318–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ranchoux, B.; Antigny, F.; Rucker-Martin, C.; Hautefort, A.; Péchoux, C.; Bogaard, H.J.; Dorfmüller, P.; Remy, S.; Lecerf, F.; Planté, S.; et al. Endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition in pulmonary hypertension. Circulation 2015, 131, 1006–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kherbeck, N.; Tamby, M.C.; Bussone, G.; Dib, H.; Perros, F.; Humbert, M.; Mouthon, L. The role of inflammation and autoimmunity in the pathophysiology of pulmonary arterial hypertension. Clin. Rev. Allergy Immunol. 2013, 44, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malenfant, S.; Neyron, A.-S.; Paulin, R.; Potus, F.; Meloche, J.; Provencher, S.; Bonnet, S. Signal transduction in the development of pulmonary arterial hypertension. Pulm. Circ. 2013, 3, 278–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perros, F.; Humbert, M.; Cohen-Kaminsky, S. Pulmonary arterial hypertension: A flavor of autoimmunity. Méd. Sci. 2013, 29, 607–616. [Google Scholar]

- Montani, D.; Günther, S.; Dorfmüller, P.; Perros, F.; Girerd, B.; Garcia, G.; Jaïs, X.; Savale, L.; Artaud-Macari, E.; Price, L.C.; et al. Pulmonary arterial hypertension. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2013, 8, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montani, D.; Chaumais, M.-C.; Guignabert, C.; Günther, S.; Girerd, B.; Jaïs, X.; Algalarrondo, V.; Price, L.C.; Savale, L.; Sitbon, O.; et al. Targeted therapies in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Pharmacol. Ther. 2014, 141, 172–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Humbert, M.; Sitbon, O.; Chaouat, A.; Bertocchi, M.; Habib, G.; Gressin, V.; Yaïci, A.; Weitzenblum, E.; Cordier, J.-F.; Chabot, F.; et al. Survival in patients with idiopathic, familial, and anorexigen-associated pulmonary arterial hypertension in the modern management era. Circulation 2010, 122, 156–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rabinovitch, M.; Guignabert, C.; Humbert, M.; Nicolls, M.R. Inflammation and immunity in the pathogenesis of pulmonary arterial hypertension. Circ. Res. 2014, 115, 165–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Intengan, H.D.; Schiffrin, E.L. Vascular remodeling in hypertension: Roles of apoptosis, inflammation, and fibrosis. Hypertension 2001, 38, 581–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lodish, H.; Berk, A.; Zipursky, S.L.; Matsudaira, P.; Baltimore, D.; Darnell, J. DNA Damage and Repair and Their Role in Carcinogenesis. In Molecular Cell Biology; W.H. Freeman: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Vaillancourt, M.; Ruffenach, G.; Meloche, J.; Bonnet, S. Adaptation and remodelling of the pulmonary circulation in pulmonary hypertension. Can. J. Cardiol. 2015, 31, 407–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindahl, T. Instability and decay of the primary structure of DNA. Nature 1993, 362, 709–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esterbauer, H.; Eckl, P.; Ortner, A. Possible mutagens derived from lipids and lipid precursors. Mutat. Res. 1990, 238, 223–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holliday, R.; Ho, T. Gene silencing and endogenous DNA methylation in mammalian cells. Mutat. Res. 1998, 400, 361–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bont, R.; van Larebeke, N. Endogenous DNA damage in humans: A review of quantitative data. Mutagenesis 2004, 19, 169–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoeijmakers, J.H.J. DNA damage, aging, and cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009, 361, 1475–1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ribezzo, F.; Shiloh, Y.; Schumacher, B. Systemic DNA damage responses in aging and diseases. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Helleday, T.; Eshtad, S.; Nik-Zainal, S. Mechanisms underlying mutational signatures in human cancers. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2014, 15, 585–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindahl, T.; Nyberg, B. Rate of depurination of native deoxyribonucleic acid. Biochemistry 1972, 11, 3610–3618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boiteux, S.; Guillet, M. Abasic sites in DNA: Repair and biological consequences in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. DNA Repair 2004, 3, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caldecott, K.W. Single-strand break repair and genetic disease. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2008, 9, 619–631. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Negritto, C. Double-Strand Breaks in DNA Can Be Lethal to a Cell. How Do Cells Fix Them? Available online: http://www.nature.com/scitable/topicpage/repairing-double-strand-dna-breaks-14432332 (accessed on 23 March 2016).

- Stingele, J.; Jentsch, S. DNA-protein crosslink repair. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2015, 16, 455–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noll, D.M.; Mason, T.M.; Miller, P.S. Formation and repair of interstrand cross-links in DNA. Chem. Rev. 2006, 106, 277–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lenart, P.; Krejci, L. DNA, the central molecule of aging. Mutat. Res. 2016, 786, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rouse, J.; Jackson, S.P. Interfaces between the detection, signaling, and repair of DNA damage. Science 2002, 297, 547–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harrison, J.C.; Haber, J.E. Surviving the breakup: The DNA damage checkpoint. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2006, 40, 209–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harper, J.W.; Elledge, S.J. The DNA damage response: Ten years after. Mol. Cell 2007, 28, 739–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKinnon, P.J.; Caldecott, K.W. DNA strand break repair and human genetic disease. Annu. Rev. Genom. Hum. Genet. 2007, 8, 37–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, D.M.; Barsky, D. The major human abasic endonuclease: Formation, consequences and repair of abasic lesions in DNA. Mutat. Res. 2001, 485, 283–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demple, B.; Sung, J.-S. Molecular and biological roles of Ape1 protein in mammalian base excision repair. DNA Repair 2005, 4, 1442–1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Izumi, T.; Wiederhold, L.R.; Roy, G.; Roy, R.; Jaiswal, A.; Bhakat, K.K.; Mitra, S.; Hazra, T.K. Mammalian DNA base excision repair proteins: Their interactions and role in repair of oxidative DNA damage. Toxicology 2003, 193, 43–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dianov, G.L.; Sleeth, K.M.; Dianova, I.I.; Allinson, S.L. Repair of abasic sites in DNA. Mutat. Res. 2003, 531, 157–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.-J.; Wilson, D.M. Overview of base excision repair biochemistry. Curr. Mol. Pharmacol. 2012, 5, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ménissier-de Murcia, J.; Molinete, M.; Gradwohl, G.; Simonin, F.; de Murcia, G. Zinc-binding domain of poly(ADP-ribose)polymerase participates in the recognition of single strand breaks on DNA. J. Mol. Biol. 1989, 210, 229–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khodyreva, S.N.; Prasad, R.; Ilina, E.S.; Sukhanova, M.V.; Kutuzov, M.M.; Liu, Y.; Hou, E.W.; Wilson, S.H.; Lavrik, O.I. Apurinic/apyrimidinic (AP) site recognition by the 5′-dRP/AP lyase in poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 (PARP-1). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 22090–22095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fisher, A.E.O.; Hochegger, H.; Takeda, S.; Caldecott, K.W. Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase 1 accelerates single-strand break repair in concert with poly(ADP-ribose) glycohydrolase. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2007, 27, 5597–5605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dianova, I.I.; Sleeth, K.M.; Allinson, S.L.; Parsons, J.L.; Breslin, C.; Caldecott, K.W.; Dianov, G.L. XRCC1-DNA polymerase beta interaction is required for efficient base excision repair. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004, 32, 2550–2555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caldecott, K.W.; Aoufouchi, S.; Johnson, P.; Shall, S. XRCC1 polypeptide interacts with DNA polymerase beta and possibly poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase, and DNA ligase III is a novel molecular “nick-sensor” in vitro. Nucleic Acids Res. 1996, 24, 4387–4394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masson, M.; Niedergang, C.; Schreiber, V.; Muller, S.; Menissier-de Murcia, J.; de Murcia, G. XRCC1 is specifically associated with poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase and negatively regulates its activity following DNA damage. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1998, 18, 3563–3571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beneke, S. Regulation of chromatin structure by poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation. Front. Genet. 2012, 3, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rouleau, M.; Patel, A.; Hendzel, M.J.; Kaufmann, S.H.; Poirier, G.G. PARP inhibition: PARP1 and beyond. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2010, 10, 293–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schreiber, V.; Dantzer, F.; Ame, J.-C.; de Murcia, G. Poly(ADP-ribose): Novel functions for an old molecule. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2006, 7, 517–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marteijn, J.A.; Lans, H.; Vermeulen, W.; Hoeijmakers, J.H.J. Understanding nucleotide excision repair and its roles in cancer and ageing. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2014, 15, 465–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torgovnick, A.; Schumacher, B. DNA repair mechanisms in cancer development and therapy. Front. Genet. 2015, 6, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanawalt, P.C.; Spivak, G. Transcription-coupled DNA repair: Two decades of progress and surprises. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2008, 9, 958–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knoch, J.; Kamenisch, Y.; Kubisch, C.; Berneburg, M. Rare hereditary diseases with defects in DNA-repair. Eur. J. Dermatol. 2012, 22, 443–455. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Guillotin, D.; Martin, S.A. Exploiting DNA mismatch repair deficiency as a therapeutic strategy. Exp. Cell Res. 2014, 329, 110–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, G.-M. Mechanisms and functions of DNA mismatch repair. Cell Res. 2008, 18, 85–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Modrich, P.; Lahue, R. Mismatch repair in replication fidelity, genetic recombination, and cancer biology. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1996, 65, 101–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kunkel, T.A.; Erie, D.A. DNA mismatch repair. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2005, 74, 681–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiricny, J. The multifaceted mismatch-repair system. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2006, 7, 335–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iyama, T.; Wilson, D.M. DNA repair mechanisms in dividing and non-dividing cells. DNA Repair 2013, 12, 620–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnheim, N.; Shibata, D. DNA mismatch repair in mammals: Role in disease and meiosis. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 1997, 7, 364–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peltomäki, P. DNA mismatch repair and cancer. Mutat. Res. 2001, 488, 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Q.; Reddy, Y.V.R.; Wang, W.; Woods, T.; Douglas, P.; Ramsden, D.A.; Lees-Miller, S.P.; Meek, K. Autophosphorylation of the catalytic subunit of the DNA-dependent protein kinase is required for efficient end processing during DNA double-strand break repair. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2003, 23, 5836–5848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Helleday, T.; Lo, J.; van Gent, D.C.; Engelward, B.P. DNA double-strand break repair: From mechanistic understanding to cancer treatment. DNA Repair 2007, 6, 923–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deriano, L.; Roth, D.B. Modernizing the nonhomologous end-joining repertoire: Alternative and classical NHEJ share the stage. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2013, 47, 433–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicolai, S.; Rossi, A.; di Daniele, N.; Melino, G.; Annicchiarico-Petruzzelli, M.; Raschellà, G. DNA repair and aging: The impact of the p53 family. Aging 2015, 7, 1050–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahnesorg, P.; Smith, P.; Jackson, S.P. XLF interacts with the XRCC4-DNA ligase IV complex to promote DNA nonhomologous end-joining. Cell 2006, 124, 301–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roy, S.; de Melo, A.J.; Xu, Y.; Tadi, S.K.; Négrel, A.; Hendrickson, E.; Modesti, M.; Meek, K. XRCC4/XLF Interaction is variably required for DNA repair and is not required for ligase IV stimulation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2015, 35, 3017–3028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Della-Maria, J.; Zhou, Y.; Tsai, M.-S.; Kuhnlein, J.; Carney, J.P.; Paull, T.T.; Tomkinson, A.E. Human Mre11/human Rad50/Nbs1 and DNA ligase IIIalpha/XRCC1 protein complexes act together in an alternative nonhomologous end joining pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 33845–33853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boboila, C.; Alt, F.W.; Schwer, B. Classical and alternative end-joining pathways for repair of lymphocyte-specific and general DNA double-strand breaks. Adv. Immunol. 2012, 116, 1–49. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Metzger, M.J.; Stoddard, B.L.; Monnat, R.J. PARP-mediated repair, homologous recombination, and back-up non-homologous end joining-like repair of single-strand nicks. DNA Repair 2013, 12, 529–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bunting, S.F.; Nussenzweig, A. End-joining, translocations and cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2013, 13, 443–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Audebert, M.; Salles, B.; Calsou, P. Involvement of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 and XRCC1/DNA ligase III in an alternative route for DNA double-strand breaks rejoining. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 55117–55126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuneo, M.J.; Gabel, S.A.; Krahn, J.M.; Ricker, M.A.; London, R.E. The structural basis for partitioning of the XRCC1/DNA ligase III-α BRCT-mediated dimer complexes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011, 39, 7816–7827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sfeir, A.; Symington, L.S. Microhomology-mediated end joining: A back-up survival mechanism or dedicated pathway? Trends Biochem. Sci. 2015, 40, 701–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Czornak, K.; Chughtai, S.; Chrzanowska, K.H. Mystery of DNA repair: The role of the MRN complex and ATM kinase in DNA damage repair. J. Appl. Genet. 2008, 49, 383–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamarche, B.J.; Orazio, N.I.; Weitzman, M.D. The MRN complex in double-strand break repair and telomere maintenance. FEBS Lett. 2010, 584, 3682–3695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aravind, L.; Makarova, K.S.; Koonin, E.V. SURVEY AND SUMMARY: Holliday junction resolvases and related nucleases: Identification of new families, phyletic distribution and evolutionary trajectories. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000, 28, 3417–3432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wyatt, H.D.M.; West, S.C. Holliday junction resolvases. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2014, 6, a023192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ip, S.C.Y.; Rass, U.; Blanco, M.G.; Flynn, H.R.; Skehel, J.M.; West, S.C. Identification of Holliday junction resolvases from humans and yeast. Nature 2008, 456, 357–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bizard, A.H.; Hickson, I.D. The dissolution of double Holliday junctions. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2014, 6, a016477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swuec, P.; Costa, A. Molecular mechanism of double Holliday junction dissolution. Cell Biosci. 2014, 4, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bocquet, N.; Bizard, A.H.; Abdulrahman, W.; Larsen, N.B.; Faty, M.; Cavadini, S.; Bunker, R.D.; Kowalczykowski, S.C.; Cejka, P.; Hickson, I.D.; et al. Structural and mechanistic insight into Holliday-junction dissolution by topoisomerase IIIα and RMI1. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2014, 21, 261–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- San Filippo, J.; Sung, P.; Klein, H. Mechanism of eukaryotic homologous recombination. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2008, 77, 229–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moynahan, M.E.; Jasin, M. Mitotic homologous recombination maintains genomic stability and suppresses tumorigenesis. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2010, 11, 196–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Symington, L.S.; Gautier, J. Double-strand break end resection and repair pathway choice. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2011, 45, 247–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakr, A.; Oing, C.; Köcher, S.; Borgmann, K.; Dornreiter, I.; Petersen, C.; Dikomey, E.; Mansour, W.Y. Involvement of ATM in homologous recombination after end resection and RAD51 nucleofilament formation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015, 43, 3154–3166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dahm-Daphi, J.; Hubbe, P.; Horvath, F.; El-Awady, R.A.; Bouffard, K.E.; Powell, S.N.; Willers, H. Nonhomologous end-joining of site-specific but not of radiation-induced DNA double-strand breaks is reduced in the presence of wild-type p53. Oncogene 2005, 24, 1663–1672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menon, V.; Povirk, L. Involvement of p53 in the repair of DNA double strand breaks: Multifaceted roles of p53 in homologous recombination repair (HRR) and non-homologous end joining (NHEJ). Subcell. Biochem. 2014, 85, 321–336. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Panier, S.; Boulton, S.J. Double-strand break repair: 53BP1 comes into focus. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2014, 15, 7–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bau, D.-T.; Mau, Y.-C.; Shen, C.-Y. The role of BRCA1 in non-homologous end-joining. Cancer Lett. 2006, 240, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Welcsh, P.L.; King, M.C. BRCA1 and BRCA2 and the genetics of breast and ovarian cancer. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2001, 10, 705–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haupt, S.; Raghu, D.; Haupt, Y. Mutant p53 drives cancer by subverting multiple tumor suppression pathways. Front. Oncol. 2016, 6, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guirouilh-Barbat, J.; Lambert, S.; Bertrand, P.; Lopez, B.S. Is homologous recombination really an error-free process? Front. Genet. 2014, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, S.; Javadekar, S.M.; Pandey, M.; Srivastava, M.; Kumari, R.; Raghavan, S.C. Homology and enzymatic requirements of microhomology-dependent alternative end joining. Cell Death Dis. 2015, 6, e1697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aparicio, T.; Baer, R.; Gautier, J. DNA double-strand break repair pathway choice and cancer. DNA Repair 2014, 19, 169–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sinha, S.; Villarreal, D.; Shim, E.Y.; Lee, S.E. Risky business: Microhomology-mediated end joining. Mutat. Res. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kent, T.; Chandramouly, G.; McDevitt, S.M.; Ozdemir, A.Y.; Pomerantz, R.T. Mechanism of microhomology-mediated end-joining promoted by human DNA polymerase θ. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2015, 22, 230–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lemée, F.; Bergoglio, V.; Fernandez-Vidal, A.; Machado-Silva, A.; Pillaire, M.-J.; Bieth, A.; Gentil, C.; Baker, L.; Martin, A.-L.; Leduc, C.; et al. DNA polymerase theta up-regulation is associated with poor survival in breast cancer, perturbs DNA replication, and promotes genetic instability. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 13390–13395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgins, G.S.; Harris, A.L.; Prevo, R.; Helleday, T.; McKenna, W.G.; Buffa, F.M. Overexpression of POLQ confers a poor prognosis in early breast cancer patients. Oncotarget 2010, 1, 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.D.; Shroyer, K.R.; Markham, N.E.; Cool, C.D.; Voelkel, N.F.; Tuder, R.M. Monoclonal endothelial cell proliferation is present in primary but not secondary pulmonary hypertension. J. Clin. Investig. 1998, 101, 927–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuder, R.M.; Radisavljevic, Z.; Shroyer, K.R.; Polak, J.M.; Voelkel, N.F. Monoclonal endothelial cells in appetite suppressant-associated pulmonary hypertension. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 1998, 158, 1999–2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeager, M.E.; Halley, G.R.; Golpon, H.A.; Voelkel, N.F.; Tuder, R.M. Microsatellite instability of endothelial cell growth and apoptosis genes within plexiform lesions in primary pulmonary hypertension. Circ. Res. 2001, 88, E2–E11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aldred, M.A.; Comhair, S.A.; Varella-Garcia, M.; Asosingh, K.; Xu, W.; Noon, G.P.; Thistlethwaite, P.A.; Tuder, R.M.; Erzurum, S.C.; Geraci, M.W.; et al. Somatic chromosome abnormalities in the lungs of patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2010, 182, 1153–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Federici, C.; Drake, K.M.; Rigelsky, C.M.; McNelly, L.N.; Meade, S.L.; Comhair, S.A.A.; Erzurum, S.C.; Aldred, M.A. Increased Mutagen Sensitivity and DNA Damage in Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2015, 192, 219–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simonneau, G.; Gatzoulis, M.A.; Adatia, I.; Celermajer, D.; Denton, C.; Ghofrani, A.; Gomez Sanchez, M.A.; Krishna Kumar, R.; Landzberg, M.; Machado, R.F.; et al. Updated clinical classification of pulmonary hypertension. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2013, 62, D34–D41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanchez, O.; Sitbon, O.; Jaïs, X.; Simonneau, G.; Humbert, M. Immunosuppressive therapy in connective tissue diseases-associated pulmonary arterial hypertension. Chest 2006, 130, 182–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karmochkine, M.; Wechsler, B.; Godeau, P.; Brenot, F.; Jagot, J.L.; Simonneau, G. Improvement of severe pulmonary hypertension in a patient with SLE. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 1996, 55, 561–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meloche, J.; Renard, S.; Provencher, S.; Bonnet, S. Anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive agents in PAH. Handb. Exp. Pharmacol. 2013, 218, 437–476. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jouve, P.; Humbert, M.; Chauveheid, M.-P.; Jaïs, X.; Papo, T. POEMS syndrome-related pulmonary hypertension is steroid-responsive. Respir. Med. 2007, 101, 353–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dorfmüller, P.; Perros, F.; Balabanian, K.; Humbert, M. Inflammation in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur. Respir. J. 2003, 22, 358–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perros, F.; Dorfmüller, P.; Montani, D.; Hammad, H.; Waelput, W.; Girerd, B.; Raymond, N.; Mercier, O.; Mussot, S.; Cohen-Kaminsky, S.; et al. Pulmonary lymphoid neogenesis in idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2012, 185, 311–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen-Kaminsky, S.; Ranchoux, B.; Perros, F. CXCL13 in tertiary lymphoid tissues: Sites of production are different from sites of functional localization. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2014, 189, 369–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Price, L.C.; Wort, S.J.; Perros, F.; Dorfmüller, P.; Huertas, A.; Montani, D.; Cohen-Kaminsky, S.; Humbert, M. Inflammation in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Chest 2012, 141, 210–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perros, F.; Cohen-Kaminsky, S.; Gambaryan, N.; Girerd, B.; Raymond, N.; Klingelschmitt, I.; Huertas, A.; Mercier, O.; Fadel, E.; Simonneau, G.; et al. Cytotoxic cells and granulysin in pulmonary arterial hypertension and pulmonary veno-occlusive disease. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2013, 187, 189–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montani, D.; Perros, F.; Gambaryan, N.; Girerd, B.; Dorfmuller, P.; Price, L.C.; Huertas, A.; Hammad, H.; Lambrecht, B.; Simonneau, G.; et al. C-Kit-positive cells accumulate in remodeled vessels of idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2011, 184, 116–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perros, F.; Dorfmüller, P.; Souza, R.; Durand-Gasselin, I.; Mussot, S.; Mazmanian, M.; Hervé, P.; Emilie, D.; Simonneau, G.; Humbert, M. Dendritic cell recruitment in lesions of human and experimental pulmonary hypertension. Eur. Respir. J. 2007, 29, 462–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Humbert, M.; Monti, G.; Brenot, F.; Sitbon, O.; Portier, A.; Grangeot-Keros, L.; Duroux, P.; Galanaud, P.; Simonneau, G.; Emilie, D. Increased interleukin-1 and interleukin-6 serum concentrations in severe primary pulmonary hypertension. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 1995, 151, 1628–1631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soon, E.; Holmes, A.M.; Treacy, C.M.; Doughty, N.J.; Southgate, L.; Machado, R.D.; Trembath, R.C.; Jennings, S.; Barker, L.; Nicklin, P.; et al. Elevated levels of inflammatory cytokines predict survival in idiopathic and familial pulmonary arterial hypertension. Circulation 2010, 122, 920–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hautefort, A.; Girerd, B.; Montani, D.; Cohen-Kaminsky, S.; Price, L.; Lambrecht, B.N.; Humbert, M.; Perros, F. T-helper 17 cell polarization in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Chest 2015, 147, 1610–1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Itoh, T.; Nagaya, N.; Ishibashi-Ueda, H.; Kyotani, S.; Oya, H.; Sakamaki, F.; Kimura, H.; Nakanishi, N. Increased plasma monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 level in idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension. Respirology 2006, 11, 158–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Golembeski, S.M.; West, J.; Tada, Y.; Fagan, K.A. Interleukin-6 causes mild pulmonary hypertension and augments hypoxia-induced pulmonary hypertension in mice. Chest 2005, 128, 572S–573S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyata, M.; Sakuma, F.; Yoshimura, A.; Ishikawa, H.; Nishimaki, T.; Kasukawa, R. Pulmonary hypertension in rats. 2. Role of interleukin-6. Int. Arch. Allergy Immunol. 1995, 108, 287–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steiner, M.K.; Syrkina, O.L.; Kolliputi, N.; Mark, E.J.; Hales, C.A.; Waxman, A.B. Interleukin-6 overexpression induces pulmonary hypertension. Circ. Res. 2009, 104, 236–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savale, L.; Tu, L.; Rideau, D.; Izziki, M.; Maitre, B.; Adnot, S.; Eddahibi, S. Impact of interleukin-6 on hypoxia-induced pulmonary hypertension and lung inflammation in mice. Respir. Res. 2009, 10, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meira, L.B.; Bugni, J.M.; Green, S.L.; Lee, C.-W.; Pang, B.; Borenshtein, D.; Rickman, B.H.; Rogers, A.B.; Moroski-Erkul, C.A.; McFaline, J.L.; et al. DNA damage induced by chronic inflammation contributes to colon carcinogenesis in mice. J. Clin. Investig. 2008, 118, 2516–2525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wheelhouse, N.M.; Chan, Y.-S.; Gillies, S.E.; Caldwell, H.; Ross, J.A.; Harrison, D.J.; Prost, S. TNF-α induced DNA damage in primary murine hepatocytes. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2003, 12, 889–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suematsu, N.; Tsutsui, H.; Wen, J.; Kang, D.; Ikeuchi, M.; Ide, T.; Hayashidani, S.; Shiomi, T.; Kubota, T.; Hamasaki, N.; et al. Oxidative stress mediates tumor necrosis factor-alpha-induced mitochondrial DNA damage and dysfunction in cardiac myocytes. Circulation 2003, 107, 1418–1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poltz, R.; Naumann, M. Dynamics of p53 and NF-κB regulation in response to DNA damage and identification of target proteins suitable for therapeutic intervention. BMC Syst. Biol. 2012, 6, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pikarsky, E.; Porat, R.M.; Stein, I.; Abramovitch, R.; Amit, S.; Kasem, S.; Gutkovich-Pyest, E.; Urieli-Shoval, S.; Galun, E.; Ben-Neriah, Y. NF-kappaB functions as a tumour promoter in inflammation-associated cancer. Nature 2004, 431, 461–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kidane, D.; Chae, W.J.; Czochor, J.; Eckert, K.A.; Glazer, P.M.; Bothwell, A.L.M.; Sweasy, J.B. Interplay between DNA repair and inflammation, and the link to cancer. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2014, 49, 116–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hussain, S.P.; Harris, C.C. Inflammation and cancer: An ancient link with novel potentials. Int. J. Cancer 2007, 121, 2373–2380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schetter, A.J.; Heegaard, N.H.H.; Harris, C.C. Inflammation and cancer: Interweaving microRNA, free radical, cytokine and p53 pathways. Carcinogenesis 2010, 31, 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pálmai-Pallag, T.; Bachrati, C.Z. Inflammation-induced DNA damage and damage-induced inflammation: A vicious cycle. Microbes Infect. Inst. Pasteur 2014, 16, 822–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olivieri, F.; Albertini, M.C.; Orciani, M.; Ceka, A.; Cricca, M.; Procopio, A.D.; Bonafè, M. DNA damage response (DDR) and senescence: Shuttled inflamma-miRNAs on the stage of inflamm-aging. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 35509–35521. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yun, U.J.; Park, S.E.; Jo, Y.S.; Kim, J.; Shin, D.Y. DNA damage induces the IL-6/STAT3 signaling pathway, which has anti-senescence and growth-promoting functions in human tumors. Cancer Lett. 2012, 323, 155–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grivennikov, S.; Karin, E.; Terzic, J.; Mucida, D.; Yu, G.-Y.; Vallabhapurapu, S.; Scheller, J.; Rose-John, S.; Cheroutre, H.; Eckmann, L.; et al. IL-6 and Stat3 are required for survival of intestinal epithelial cells and development of colitis-associated cancer. Cancer Cell 2009, 15, 103–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bromberg, J.; Wang, T.C. Inflammation and cancer: IL-6 and STAT3 complete the link. Cancer Cell 2009, 15, 79–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morrell, N.W. Pulmonary hypertension due to BMPR2 mutation: A new paradigm for tissue remodeling? Proc. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2006, 3, 680–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hagen, M.; Fagan, K.; Steudel, W.; Carr, M.; Lane, K.; Rodman, D.M.; West, J. Interaction of interleukin-6 and the BMP pathway in pulmonary smooth muscle. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2007, 292, L1473–L1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perros, F.; Bonnet, S. Bone morphogenetic protein receptor type II and inflammation are bringing old concepts into the new pulmonary arterial hypertension world. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2015, 192, 777–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soon, E.; Crosby, A.; Southwood, M.; Yang, P.; Tajsic, T.; Toshner, M.; Appleby, S.; Shanahan, C.M.; Bloch, K.D.; Pepke-Zaba, J.; et al. Bone morphogenetic protein receptor type II deficiency and increased inflammatory cytokine production. A gateway to pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2015, 192, 859–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paulin, R.; Meloche, J.; Bonnet, S. STAT3 signaling in pulmonary arterial hypertension. JAK-STAT 2012, 1, 223–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perros, F.; Montani, D.; Dorfmüller, P.; Durand-Gasselin, I.; Tcherakian, C.; Le Pavec, J.; Mazmanian, M.; Fadel, E.; Mussot, S.; Mercier, O.; et al. Platelet-derived growth factor expression and function in idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2008, 178, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aggarwal, S.; Gross, C.M.; Sharma, S.; Fineman, J.R.; Black, S.M. Reactive oxygen species in pulmonary vascular remodeling. Compr. Physiol. 2013, 3, 1011–1034. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bowers, R.; Cool, C.; Murphy, R.C.; Tuder, R.M.; Hopken, M.W.; Flores, S.C.; Voelkel, N.F. Oxidative stress in severe pulmonary hypertension. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2004, 169, 764–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demarco, V.G.; Whaley-Connell, A.T.; Sowers, J.R.; Habibi, J.; Dellsperger, K.C. Contribution of oxidative stress to pulmonary arterial hypertension. World J. Cardiol. 2010, 2, 316–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dorfmüller, P.; Chaumais, M.-C.; Giannakouli, M.; Durand-Gasselin, I.; Raymond, N.; Fadel, E.; Mercier, O.; Charlotte, F.; Montani, D.; Simonneau, G.; et al. Increased oxidative stress and severe arterial remodeling induced by permanent high-flow challenge in experimental pulmonary hypertension. Respir. Res. 2011, 12, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Black, S.M.; DeVol, J.M.; Wedgwood, S. Regulation of fibroblast growth factor-2 expression in pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells involves increased reactive oxygen species generation. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2008, 294, C345–C354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montisano, D.F.; Mann, T.; Spragg, R.G. H2O2 increases expression of pulmonary artery endothelial cell platelet-derived growth factor mRNA. J. Appl. Physiol. 1992, 73, 2255–2262. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wedgwood, S.; Dettman, R.W.; Black, S.M. ET-1 stimulates pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cell proliferation via induction of reactive oxygen species. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2001, 281, L1058–1067. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Block, K.; Gorin, Y.; Hoover, P.; Williams, P.; Chelmicki, T.; Clark, R.A.; Yoneda, T.; Abboud, H.E. NAD(P)H oxidases regulate HIF-2alpha protein expression. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 8019–8026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chandel, N.S.; McClintock, D.S.; Feliciano, C.E.; Wood, T.M.; Melendez, J.A.; Rodriguez, A.M.; Schumacker, P.T. Reactive oxygen species generated at mitochondrial complex III stabilize hypoxia-inducible factor-1α during hypoxia A MECHANISM OF O2 SENSING. J. Biol. Chem. 2000, 275, 25130–25138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gale, D.P.; Harten, S.K.; Reid, C.D.L.; Tuddenham, E.G.D.; Maxwell, P.H. Autosomal dominant erythrocytosis and pulmonary arterial hypertension associated with an activating HIF2α mutation. Blood 2008, 112, 919–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brusselmans, K.; Compernolle, V.; Tjwa, M.; Wiesener, M.S.; Maxwell, P.H.; Collen, D.; Carmeliet, P. Heterozygous deficiency of hypoxia-inducible factor–2α protects mice against pulmonary hypertension and right ventricular dysfunction during prolonged hypoxia. J. Clin. Investig. 2003, 111, 1519–1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, T.H.; Shih, N.L.; Chen, S.Y.; Loh, S.H.; Cheng, P.Y.; Tsai, C.S.; Liu, S.H.; Wang, D.L.; Chen, J.J. Reactive oxygen species mediate cyclic strain-induced endothelin-1 gene expression via Ras/Raf/extracellular signal-regulated kinase pathway in endothelial cells. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2001, 33, 1805–1814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tate, R.M.; Morris, H.G.; Schroeder, W.R.; Repine, J.E. Oxygen metabolites stimulate thromboxane production and vasoconstriction in isolated saline-perfused rabbit lungs. J. Clin. Investig. 1984, 74, 608–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, D.S.; McCallum, E.A.; Olson, D.M. Effects of reactive oxygen species on prostacyclin production in perinatal rat lung cells. J. Appl. Physiol. 1989, 66, 1321–1327. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Brito, R.; Castillo, G.; González, J.; Valls, N.; Rodrigo, R. Oxidative stress in hypertension: Mechanisms and therapeutic opportunities. Exp. Clin. Endocrinol. Diabetes 2015, 123, 325–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weissmann, N.; Winterhalder, S.; Nollen, M.; Voswinckel, R.; Quanz, K.; Ghofrani, H.A.; Schermuly, R.T.; Seeger, W.; Grimminger, F. NO and reactive oxygen species are involved in biphasic hypoxic vasoconstriction of isolated rabbit lungs. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2001, 280, L638–L645. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Waypa, G.B.; Marks, J.D.; Mack, M.M.; Boriboun, C.; Mungai, P.T.; Schumacker, P.T. Mitochondrial Reactive oxygen species trigger calcium increases during hypoxia in pulmonary arterial myocytes. Circ. Res. 2002, 91, 719–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoshikawa, Y.; Ono, S.; Suzuki, S.; Tanita, T.; Chida, M.; Song, C.; Noda, M.; Tabata, T.; Voelkel, N.F.; Fujimura, S. Generation of oxidative stress contributes to the development of pulmonary hypertension induced by hypoxia. J. Appl. Physiol. 2001, 90, 1299–1306. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jankov, R.P.; Kantores, C.; Pan, J.; Belik, J. Contribution of xanthine oxidase-derived superoxide to chronic hypoxic pulmonary hypertension in neonatal rats. Am. J. Physiol. 2008, 294, L233–L245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rafikova, O.; Rafikov, R.; Kangath, A.; Qu, N.; Aggarwal, S.; Sharma, S.; Desai, J.; Fields, T.; Ludewig, B.; Yuan, J.X.-Y.; et al. Redox regulation of epidermal growth factor receptor signaling during the development of pulmonary hypertension. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rawat, D.K.; Alzoubi, A.; Gupte, R.; Chettimada, S.; Watanabe, M.; Kahn, A.G.; Okada, T.; McMurtry, I.F.; Gupte, S.A. Increased reactive oxygen species, metabolic maladaptation, and autophagy contribute to pulmonary arterial hypertension-induced ventricular hypertrophy and diastolic heart failure. Hypertension 2014, 64, 1266–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.Q.; Zelko, I.N.; Erbynn, E.M.; Sham, J.S.K.; Folz, R.J. Hypoxic pulmonary hypertension: Role of superoxide and NADPH oxidase (gp91phox). Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2006, 290, L2–L10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsui, H.; Shimosawa, T.; Itakura, K.; Guanqun, X.; Ando, K.; Fujita, T. Adrenomedullin can protect against pulmonary vascular remodeling induced by hypoxia. Circulation 2004, 109, 2246–2251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, M.; Wang, Y.; Zheng, L.; Zheng, W.; Dong, K.; Chen, S.; Zhang, B.; Li, Z. Fasudil reversed MCT-induced and chronic hypoxia-induced pulmonary hypertension by attenuating oxidative stress and inhibiting the expression of Trx1 and HIF-1α. Respir. Physiol. Neurobiol. 2014, 201, 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, B.; Niu, W.; Xu, D.; Li, Y.; Liu, M.; Wang, Y.; Luo, Y.; Zhao, P.; Liu, Y.; Dong, M.; et al. Oxymatrine prevents hypoxia- and monocrotaline-induced pulmonary hypertension in rats. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2014, 69, 198–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaumais, M.-C.; Ranchoux, B.; Montani, D.; Dorfmüller, P.; Tu, L.; Lecerf, F.; Raymond, N.; Guignabert, C.; Price, L.; Simonneau, G.; et al. N-acetylcysteine improves established monocrotaline-induced pulmonary hypertension in rats. Respir. Res. 2014, 15, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mittal, M.; Roth, M.; König, P.; Hofmann, S.; Dony, E.; Goyal, P.; Selbitz, A.-C.; Schermuly, R.T.; Ghofrani, H.A.; Kwapiszewska, G.; et al. Hypoxia-dependent regulation of nonphagocytic NADPH oxidase subunit NOX4 in the pulmonary vasculature. Circ. Res. 2007, 101, 258–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Babior, B.M. The NADPH oxidase of endothelial cells. IUBMB Life 2000, 50, 267–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vignais, P.V. The superoxide-generating NADPH oxidase: Structural aspects and activation mechanism. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2002, 59, 1428–1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fresquet, F.; Pourageaud, F.; Leblais, V.; Brandes, R.P.; Savineau, J.-P.; Marthan, R.; Muller, B. Role of reactive oxygen species and gp91phox in endothelial dysfunction of pulmonary arteries induced by chronic hypoxia. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2006, 148, 714–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paravicini, T.M.; Gulluyan, L.M.; Dusting, G.J.; Drummond, G.R. Increased NADPH oxidase activity, gp91phox expression, and endothelium-dependent vasorelaxation during neointima formation in rabbits. Circ. Res. 2002, 91, 54–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Tabar, S.S.; Malec, V.; Eul, B.G.; Klepetko, W.; Weissmann, N.; Grimminger, F.; Seeger, W.; Rose, F.; Hänze, J. NOX4 regulates ROS levels under normoxic and hypoxic conditions, triggers proliferation, and inhibits apoptosis in pulmonary artery adventitial fibroblasts. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2008, 10, 1687–1698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sturrock, A.; Cahill, B.; Norman, K.; Huecksteadt, T.P.; Hill, K.; Sanders, K.; Karwande, S.V.; Stringham, J.C.; Bull, D.A.; Gleich, M.; et al. Transforming growth factor-beta1 induces Nox4 NAD(P)H oxidase and reactive oxygen species-dependent proliferation in human pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2006, 290, L661–L673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selimovic, N.; Bergh, C.-H.; Andersson, B.; Sakiniene, E.; Carlsten, H.; Rundqvist, B. Growth factors and interleukin-6 across the lung circulation in pulmonary hypertension. Eur. Respir. J. 2009, 34, 662–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landmesser, U.; Dikalov, S.; Price, S.R.; McCann, L.; Fukai, T.; Holland, S.M.; Mitch, W.E.; Harrison, D.G. Oxidation of tetrahydrobiopterin leads to uncoupling of endothelial cell nitric oxide synthase in hypertension. J. Clin. Investig. 2003, 111, 1201–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris, C.R.; Kato, G.J.; Poljakovic, M.; Wang, X.; Blackwelder, W.C.; Sachdev, V.; Hazen, S.L.; Vichinsky, E.P.; Morris, S.M.; Gladwin, M.T. Dysregulated arginine metabolism, hemolysis-associated pulmonary hypertension, and mortality in sickle cell disease. JAMA 2005, 294, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pullamsetti, S.; Kiss, L.; Ghofrani, H.A.; Voswinckel, R.; Haredza, P.; Klepetko, W.; Aigner, C.; Fink, L.; Muyal, J.P.; Weissmann, N.; et al. Increased levels and reduced catabolism of asymmetric and symmetric dimethylarginines in pulmonary hypertension. FASEB J. Off. Publ. Fed. Am. Soc. Exp. Biol. 2005, 19, 1175–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iannone, L.; Zhao, L.; Dubois, O.; Duluc, L.; Rhodes, C.J.; Wharton, J.; Wilkins, M.R.; Leiper, J.; Wojciak-Stothard, B. miR-21/DDAH1 pathway regulates pulmonary vascular responses to hypoxia. Biochem. J. 2014, 462, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.-H.; Peng, J.; Tan, N.; Wu, W.-H.; Li, T.-T.; Shi, R.-Z.; Li, Y.-J. Involvement of asymmetric dimethylarginine and Rho kinase in the vascular remodeling in monocrotaline-induced pulmonary hypertension. Vascul. Pharmacol. 2010, 53, 223–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Archer, S.L.; Marsboom, G.; Kim, G.H.; Zhang, H.J.; Toth, P.T.; Svensson, E.C.; Dyck, J.R.B.; Gomberg-Maitland, M.; Thébaud, B.; Husain, A.N.; et al. Epigenetic attenuation of mitochondrial superoxide dismutase 2 (SOD2) in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Circulation 2010, 121, 2661–2671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reis, G.S.; Augusto, V.S.; Silveira, A.P.C.; Jordão, A.A.; Baddini-Martinez, J.; Poli Neto, O.; Rodrigues, A.J.; Evora, P.R.B. Oxidative-stress biomarkers in patients with pulmonary hypertension. Pulm. Circ. 2013, 3, 856–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cracowski, J.L.; Cracowski, C.; Bessard, G.; Pepin, J.L.; Bessard, J.; Schwebel, C.; Stanke-Labesque, F.; Pison, C. Increased lipid peroxidation in patients with pulmonary hypertension. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2001, 164, 1038–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, C.-M.; Bansal, G.; Pavlickova, L.; Marcocci, L.; Suzuki, Y.J. Reactive oxygen species and antioxidants in pulmonary hypertension. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2013, 18, 1789–1796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tabima, D.M.; Frizzell, S.; Gladwin, M.T. Reactive oxygen and nitrogen species in pulmonary hypertension. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2012, 52, 1970–1986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crosswhite, P.; Sun, Z. Nitric oxide, oxidative stress and inflammation in pulmonary arterial hypertension. J. Hypertens. 2010, 28, 201–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yasui, M.; Kanemaru, Y.; Kamoshita, N.; Suzuki, T.; Arakawa, T.; Honma, M. Tracing the fates of site-specifically introduced DNA adducts in the human genome. DNA Repair 2014, 15, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez, G.R.; Loureiro, A.P.M.; Marques, S.A.; Miyamoto, S.; Yamaguchi, L.F.; Onuki, J.; Almeida, E.A.; Garcia, C.C.M.; Barbosa, L.F.; Medeiros, M.H.G.; et al. Oxidative and alkylating damage in DNA. Mutat. Res. 2003, 544, 115–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klaunig, J.E.; Kamendulis, L.M.; Hocevar, B.A. Oxidative stress and oxidative damage in carcinogenesis. Toxicol. Pathol. 2010, 38, 96–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gurtner, H.P. Aminorex and pulmonary hypertension. A review. Cor et Vasa 1985, 27, 160–171. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Simonneau, G.; Fartoukh, M.; Sitbon, O.; Humbert, M.; Jagot, J.L.; Hervé, P. Primary pulmonary hypertension associated with the use of fenfluramine derivatives. Chest 1998, 114, 195S–199S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Douglas, J.G.; Munro, J.F.; Kitchin, A.H.; Muir, A.L.; Proudfoot, A.T. Pulmonary hypertension and fenfluramine. Br. Med. J. Clin. Res. Ed. 1981, 283, 881–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sitbon, O.; Humbert, M.; Simonneau, G. Pulmonary hypertension related to appetite suppressants. In Pulmonary Circulation: Diseases and Their Treatment, 3rd ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Chin, K.M.; Channick, R.N.; Rubin, L.J. Is methamphetamine use associated with idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension? Chest 2006, 130, 1657–1663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaiberger, P.H.; Kennedy, T.C.; Miller, F.C.; Gal, J.; Petty, T.L. Pulmonary hypertension associated with long-term inhalation of “crank” methamphetamine. Chest 1993, 104, 614–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montani, D.; Seferian, A.; Savale, L.; Simonneau, G.; Humbert, M. Drug-induced pulmonary arterial hypertension: A recent outbreak. Eur. Respir. Rev. 2013, 22, 244–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonçalves, C.L.; Rezin, G.T.; Ferreira, G.K.; Jeremias, I.C.; Cardoso, M.R.; Valvassori, S.S.; Munhoz, B.J.P.; Borges, G.D.; Bristot, B.N.; Leffa, D.D.; et al. Effects of acute and chronic administration of fenproporex on DNA damage parameters in young and adult rats. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2013, 380, 171–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alvarenga, T.A.; Andersen, M.L.; Ribeiro, D.A.; Araujo, P.; Hirotsu, C.; Costa, J.L.; Battisti, M.C.; Tufik, S. Single exposure to cocaine or ecstasy induces DNA damage in brain and other organs of mice. Addict. Biol. 2010, 15, 96–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andreazza, A.C.; Kauer-Sant’Anna, M.; Frey, B.N.; Stertz, L.; Zanotto, C.; Ribeiro, L.; Giasson, K.; Valvassori, S.S.; Réus, G.Z.; Salvador, M.; et al. Effects of mood stabilizers on DNA damage in an animal model of mania. J. Psychiatry Neurosci. 2008, 33, 516–524. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Agarwal, K.; Mukherjee, A.; Sharma, A.; Sharma, R.; Bhardwaj, K.R.; Sen, S. Clastogenic effect of fenfluramine in mice bone marrow cells in vivo. Environ. Mol. Mutagen. 1992, 19, 323–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, Z.; Venters, J.; Guarraci, F.A.; Zewail-Foote, M. Methamphetamine induces DNA damage in specific regions of the female rat brain. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 2015, 42, 570–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakagawa, Y.; Tayama, S.; Ogata, A.; Suzuki, T.; Ishii, H. ATP-generating glycolytic substrates prevent N-nitrosofenfluramine-induced cytotoxicity in isolated rat hepatocytes. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2006, 164, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parolini, M.; Magni, S.; Castiglioni, S.; Binelli, A. Amphetamine exposure imbalanced antioxidant activity in the bivalve Dreissena polymorpha causing oxidative and genetic damage. Chemosphere 2016, 144, 207–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Da Silva, C.J.; dos Santos, J.E.; Satie Takahashi, C. An evaluation of the genotoxic and cytotoxic effects of the anti-obesity drugs sibutramine and fenproporex. Hum. Exp. Toxicol. 2010, 29, 187–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perfeito, R.; Cunha-Oliveira, T.; Rego, A.C. Reprint of: Revisiting oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction in the pathogenesis of Parkinson disease-resemblance to the effect of amphetamine drugs of abuse. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2013, 62, 186–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bengel, D.; Isaacs, K.R.; Heils, A.; Lesch, K.P.; Murphy, D.L. The appetite suppressant d-fenfluramine induces apoptosis in human serotonergic cells. Neuroreport 1998, 9, 2989–2993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eddahibi, S.; Adnot, S. Anorexigen-induced pulmonary hypertension and the serotonin (5-HT) hypothesis: Lessons for the future in pathogenesis. Respir. Res. 2002, 3, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alwan, S.; Bandoli, G.; Chambers, C.D. Maternal use of selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitors and risk of persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fornaro, E.; Li, D.; Pan, J.; Belik, J. Prenatal exposure to fluoxetine induces fetal pulmonary hypertension in the rat. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2007, 176, 1035–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadoughi, A.; Roberts, K.E.; Preston, I.R.; Lai, G.P.; McCollister, D.H.; Farber, H.W.; Hill, N.S. Use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and outcomes in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Chest 2013, 144, 531–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhalla, I.A.; Juurlink, D.N.; Gomes, T.; Granton, J.T.; Zheng, H.; Mamdani, M.M. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and pulmonary arterial hypertension: A case-control study. Chest 2012, 141, 348–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eddahibi, S.; Humbert, M.; Fadel, E.; Raffestin, B.; Darmon, M.; Capron, F.; Simonneau, G.; Dartevelle, P.; Hamon, M.; Adnot, S. Serotonin transporter overexpression is responsible for pulmonary artery smooth muscle hyperplasia in primary pulmonary hypertension. J. Clin. Investig. 2001, 108, 1141–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eddahibi, S.; Hanoun, N.; Lanfumey, L.; Lesch, K.P.; Raffestin, B.; Hamon, M.; Adnot, S. Attenuated hypoxic pulmonary hypertension in mice lacking the 5-hydroxytryptamine transporter gene. J. Clin. Investig. 2000, 105, 1555–1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gürbüzel, M.; Oral, E.; Kizilet, H.; Halici, Z.; Gulec, M. Genotoxic evaluation of selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitors by use of the somatic mutation and recombination test in Drosophila melanogaster. Mutat. Res. 2012, 748, 17–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Djordjevic, J.; Djordjevic, A.; Adzic, M.; Elaković, I.; Matić, G.; Radojcic, M.B. Fluoxetine affects antioxidant system and promotes apoptotic signaling in Wistar rat liver. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2011, 659, 61–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alzahrani, H.A.S. Sister chromatid exchanges and sperm abnormalities produced by antidepressant drug fluoxetine in mouse treated in vivo. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2012, 16, 2154–2161. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Riggin, L.; Koren, G. Effects of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors on sperm and male fertility. Can. Fam. Physician 2015, 61, 529–530. [Google Scholar]

- Attia, S.M.; Bakheet, S.A. Citalopram at the recommended human doses after long-term treatment is genotoxic for male germ cell. Food Chem. Toxicol. Int. J. Publ. Br. Ind. Biol. Res. Assoc. 2013, 53, 281–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanrikut, C.; Feldman, A.S.; Altemus, M.; Paduch, D.A.; Schlegel, P.N. Adverse effect of paroxetine on sperm. Fertil. Steril. 2010, 94, 1021–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fox, B.D.; Azoulay, L.; Dell’Aniello, S.; Langleben, D.; Lapi, F.; Benisty, J.; Suissa, S. The use of antidepressants and the risk of idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension. Can. J. Cardiol. 2014, 30, 1633–1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Czarny, P.; Kwiatkowski, D.; Kacperska, D.; Kawczyńska, D.; Talarowska, M.; Orzechowska, A.; Bielecka-Kowalska, A.; Szemraj, J.; Gałecki, P.; Śliwiński, T. Elevated level of DNA damage and impaired repair of oxidative DNA damage in patients with recurrent depressive disorder. Med. Sci. Monit. Int. Med. J. Exp. Clin. Res. 2015, 21, 412–418. [Google Scholar]

- Black, C.N.; Bot, M.; Scheffer, P.G.; Cuijpers, P.; Penninx, B.W.J.H. Is depression associated with increased oxidative stress? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2015, 51, 164–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lacave, R.; Larsen, C.-J.; Robert, J. Cancérologie Fondamentale; John Libbey Eurotext: Paris, France, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Kondo, N.; Takahashi, A.; Ono, K.; Ohnishi, T. DNA damage induced by alkylating agents and repair pathways. J. Nucleic Acids 2010, 2010, 543531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, D.; Calvo, J.A.; Samson, L.D. Balancing repair and tolerance of DNA damage caused by alkylating agents. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2012, 12, 104–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoorn, C.M.; Wagner, J.G.; Petry, T.W.; Roth, R.A. Toxicity of mitomycin C toward cultured pulmonary artery endothelium. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 1995, 130, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lushnikova, E.L.; Molodykh, O.P.; Nepomnyashchikh, L.M.; Bakulina, A.A.; Sorokina, Y.A. Ultrastructurural picture of cyclophosphamide-induced damage to the liver. Bull. Exp. Biol. Med. 2011, 151, 751–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ranchoux, B.; Günther, S.; Quarck, R.; Chaumais, M.-C.; Dorfmüller, P.; Antigny, F.; Dumas, S.J.; Raymond, N.; Lau, E.; Savale, L.; et al. Chemotherapy-induced pulmonary hypertension: Role of alkylating agents. Am. J. Pathol. 2015, 185, 356–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perros, F.; Günther, S.; Ranchoux, B.; Godinas, L.; Antigny, F.; Chaumais, M.-C.; Dorfmüller, P.; Hautefort, A.; Raymond, N.; Savale, L.; et al. Mitomycin-induced pulmonary veno-occlusive disease: Evidence from human disease and animal models. Circulation 2015, 132, 834–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montani, D.; Lau, E.M.; Dorfmüller, P.; Girerd, B.; Jaïs, X.; Savale, L.; Perros, F.; Nossent, E.; Garcia, G.; Parent, F.; et al. Pulmonary veno-occlusive disease. Eur. Respir. J. 2016, 47, 1518–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siegel, D.; Franklin, W.A.; Ross, D. Immunohistochemical detection of NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase in human lung and lung tumors. Clin. Cancer Res. 1998, 4, 2065–2070. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cooper, J.A.; Merrill, W.W.; Reynolds, H.Y. Cyclophosphamide modulation of bronchoalveolar cellular populations and macrophage oxidative metabolism. Possible mechanisms of pulmonary pharmacotoxicity. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 1986, 134, 108–114. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hamano, Y.; Sugimoto, H.; Soubasakos, M.A.; Kieran, M.; Olsen, B.R.; Lawler, J.; Sudhakar, A.; Kalluri, R. Thrombospondin-1 associated with tumor microenvironment contributes to low-dose cyclophosphamide-mediated endothelial cell apoptosis and tumor growth suppression. Cancer Res. 2004, 64, 1570–1574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohtani, T.; Nakamura, T.; Toda, K.-I.; Furukawa, F. Cyclophosphamide enhances TNF-α-induced apoptotic cell death in murine vascular endothelial cell. FEBS Lett. 2006, 580, 1597–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mytilineou, C.; Kramer, B.C.; Yabut, J.A. Glutathione depletion and oxidative stress. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 2002, 8, 385–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, A.; Poonkuzhali, B.; Shaji, R.V.; George, B.; Mathews, V.; Chandy, M.; Krishnamoorthy, R. Glutathione S-transferase M1 polymorphism: A risk factor for hepatic venoocclusive disease in bone marrow transplantation. Blood 2004, 104, 1574–1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeLeve, L.D. Cellular target of cyclophosphamide toxicity in the murine liver: Role of glutathione and site of metabolic activation. Hepatology 1996, 24, 830–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montani, D.; Lau, E.M.; Descatha, A.; Jaïs, X.; Savale, L.; Andujar, P.; Bensefa-Colas, L.; Girerd, B.; Zendah, I.; Le Pavec, J.; et al. Occupational exposure to organic solvents: A risk factor for pulmonary veno-occlusive disease. Eur. Respir. J. 2015, 46, 1721–1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, C.; Jiang, L.; Geng, C.; Zhang, X.; Cao, J.; Zhong, L. Possible involvement of oxidative stress in trichloroethylene-induced genotoxicity in human HepG2 cells. Mutat. Res. 2008, 652, 88–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roth, R.A.; Reindel, J.F. Lung vascular injury from monocrotaline pyrrole, a putative hepatic metabolite. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 1991, 283, 477–487. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yan, C.C.; Huxtable, R.J. Release of an alkylating metabolite, dehydromonocrotaline, from the isolated liver perfused with the pyrrolizidine alkaloid, monocrotaline. Proc. West. Pharmacol. Soc. 1994, 37, 107–108. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mattocks, A.R.; Jukes, R. Trapping and measurement of short-lived alkylating agents in a recirculating flow system. Chem. Biol. Interact. 1990, 76, 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meloche, J.; Pflieger, A.; Vaillancourt, M.; Paulin, R.; Potus, F.; Zervopoulos, S.; Graydon, C.; Courboulin, A.; Breuils-Bonnet, S.; Tremblay, E.; et al. Role for DNA damage signaling in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Circulation 2014, 129, 786–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meloche, J.; Le Guen, M.; Potus, F.; Vinck, J.; Ranchoux, B.; Johnson, I.; Antigny, F.; Tremblay, E.; Breuils-Bonnet, S.; Perros, F.; et al. miR-223 reverses experimental pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2015, 309, C363–C372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong, Z.; Wen, Z.; Darnell, J.E. Stat3: A STAT family member activated by tyrosine phosphorylation in response to epidermal growth factor and interleukin-6. Science 1994, 264, 95–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meloche, J.; Potus, F.; Vaillancourt, M.; Bourgeois, A.; Johnson, I.; Deschamps, L.; Chabot, S.; Ruffenach, G.; Henry, S.; Breuils-Bonnet, S.; et al. Bromodomain-containing protein 4: The epigenetic origin of pulmonary arterial hypertension. Circ. Res. 2015, 117, 525–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.; Wu, W.; Wu, W.; Rosidi, B.; Zhang, L.; Wang, H.; Iliakis, G. PARP-1 and Ku compete for repair of DNA double strand breaks by distinct NHEJ pathways. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006, 34, 6170–6182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Byrne, M.; Wray, J.; Reinert, B.; Wu, Y.; Nickoloff, J.; Lee, S.-H.; Hromas, R.; Williamson, E. Mechanisms of oncogenic chromosomal translocations. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2014, 1310, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wray, J.; Williamson, E.A.; Singh, S.B.; Wu, Y.; Cogle, C.R.; Weinstock, D.M.; Zhang, Y.; Lee, S.-H.; Zhou, D.; Shao, L.; et al. PARP1 is required for chromosomal translocations. Blood 2013, 121, 4359–4365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soni, A.; Siemann, M.; Grabos, M.; Murmann, T.; Pantelias, G.E.; Iliakis, G. Requirement for Parp-1 and DNA ligases 1 or 3 but not of Xrcc1 in chromosomal translocation formation by backup end joining. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014, 42, 6380–6392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, R. Nuclear Signaling Pathways and Targeting Transcription in Cancer; Springer Science & Business Media: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, S.; Qu, Y.; Xu, X.; Xu, Q.; Geng, J.; Xu, J. Nuclear survivin and its relationship to DNA damage repair genes in non-small cell lung cancer investigated using tissue array. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e74161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulin, R.; Meloche, J.; Jacob, M.H.; Bisserier, M.; Courboulin, A.; Bonnet, S. Dehydroepiandrosterone inhibits the Src/STAT3 constitutive activation in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2011, 301, H1798–H1809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMurtry, M.S.; Archer, S.L.; Altieri, D.C.; Bonnet, S.; Haromy, A.; Harry, G.; Bonnet, S.; Puttagunta, L.; Michelakis, E.D. Gene therapy targeting survivin selectively induces pulmonary vascular apoptosis and reverses pulmonary arterial hypertension. J. Clin. Investig. 2005, 115, 1479–1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.; Vattulainen, S.; Aho, J.; Orcholski, M.; Rojas, V.; Yuan, K.; Helenius, M.; Taimen, P.; Myllykangas, S.; de Jesus Perez, V.; et al. Loss of bone morphogenetic protein receptor 2 is associated with abnormal DNA repair in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2014, 50, 1118–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Jesus Perez, V.A.; Yuan, K.; Lyuksyutova, M.A.; Dewey, F.; Orcholski, M.E.; Shuffle, E.M.; Mathur, M.; Yancy, L.; Rojas, V.; Li, C.G.; et al. Whole-exome sequencing reveals topbp1 as a novel gene in idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2014, 189, 1260–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Y.; Katyal, S.; Downing, S.M.; Zhao, J.; Russell, H.R.; McKinnon, P.J. Neurogenesis requires TopBP1 to prevent catastrophic replicative DNA damage in early progenitors. Nat. Neurosci. 2012, 15, 819–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamane, K.; Wu, X.; Chen, J. A DNA damage-regulated BRCT-containing protein, TopBP1, is required for cell survival. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2002, 22, 555–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mäkiniemi, M.; Hillukkala, T.; Tuusa, J.; Reini, K.; Vaara, M.; Huang, D.; Pospiech, H.; Majuri, I.; Westerling, T.; Mäkelä, T.P.; et al. BRCT domain-containing protein TopBP1 functions in DNA replication and damage response. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 30399–30406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ngo, J.; Matsuyama, M.; Kim, C.; Poventud-Fuentes, I.; Bates, A.; Siedlak, S.L.; Lee, H.; Doughman, Y.Q.; Watanabe, M.; Liner, A.; et al. Bax deficiency extends the survival of Ku70 knockout mice that develop lung and heart diseases. Cell Death Dis. 2015, 6, e1706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacquin, S.; Rincheval, V.; Mignotte, B.; Richard, S.; Humbert, M.; Mercier, O.; Londoño-Vallejo, A.; Fadel, E.; Eddahibi, S. Inactivation of p53 is sufficient to induce development of pulmonary hypertension in rats. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0131940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mizuno, S.; Bogaard, H.J.; Kraskauskas, D.; Alhussaini, A.; Gomez-Arroyo, J.; Voelkel, N.F.; Ishizaki, T. p53 Gene deficiency promotes hypoxia-induced pulmonary hypertension and vascular remodeling in mice. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2011, 300, L753–L761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mouraret, N.; Marcos, E.; Abid, S.; Gary-Bobo, G.; Saker, M.; Houssaini, A.; Dubois-Rande, J.-L.; Boyer, L.; Boczkowski, J.; Derumeaux, G.; et al. Activation of lung p53 by Nutlin-3a prevents and reverses experimental pulmonary hypertension. Circulation 2013, 127, 1664–1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Potus, F.; LeGuen, M.; Provencher, S.; Meloche, J.; Bonnet, S. DNA damage at the dawn of micro-RNA pathway impairment in pulmonary arterial hypertension. RNA Dis. 2015, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courboulin, A.; Ranchoux, B.; Cohen-Kaminsky, S.; Perros, F.; Bonnet, S. MicroRNA networks in pulmonary arterial hypertension: Share mechanisms with cancer? Curr. Opin. Oncol. 2016, 28, 72–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, E.F.; Scheibye-Knudsen, M.; Chua, K.F.; Mattson, M.P.; Croteau, D.L.; Bohr, V.A. Nuclear DNA damage signalling to mitochondria in ageing. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- King, A.; Selak, M.A.; Gottlieb, E. Succinate dehydrogenase and fumarate hydratase: Linking mitochondrial dysfunction and cancer. Oncogene 2006, 25, 4675–4682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boland, M.L.; Chourasia, A.H.; Macleod, K.F. Mitochondrial dysfunction in cancer. Front. Oncol. 2013, 3, 292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sureshbabu, A.; Bhandari, V. Targeting mitochondrial dysfunction in lung diseases: Emphasis on mitophagy. Front. Physiol. 2013, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, X.; Luo, Y.-X.; Chen, H.-Z.; Liu, D.-P. Mitochondria, endothelial cell function, and vascular diseases. Front. Physiol. 2014, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, W.; Koeck, T.; Lara, A.R.; Neumann, D.; DiFilippo, F.P.; Koo, M.; Janocha, A.J.; Masri, F.A.; Arroliga, A.C.; Jennings, C.; et al. Alterations of cellular bioenergetics in pulmonary artery endothelial cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 1342–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dromparis, P.; Michelakis, E.D. Mitochondria in vascular health and disease. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2013, 75, 95–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dromparis, P.; Sutendra, G.; Michelakis, E.D. The role of mitochondria in pulmonary vascular remodeling. J. Mol. Med. 2010, 88, 1003–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quintero, M.; Colombo, S.L.; Godfrey, A.; Moncada, S. Mitochondria as signaling organelles in the vascular endothelium. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 5379–5384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kluge, M.A.; Fetterman, J.L.; Vita, J.A. Mitochondria and Endothelial Function. Circ. Res. 2013, 112, 1171–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaseva, A.V.; Moll, U.M. The mitochondrial p53 pathway. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Bioenerg. 2009, 1787, 414–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonnet, S.; Michelakis, E.D.; Porter, C.J.; Andrade-Navarro, M.A.; Thébaud, B.; Bonnet, S.; Haromy, A.; Harry, G.; Moudgil, R.; McMurtry, M.S.; et al. An abnormal mitochondrial–hypoxia inducible factor-1α–Kv channel pathway disrupts oxygen sensing and triggers pulmonary arterial hypertension in fawn hooded rats similarities to human pulmonary arterial hypertension. Circulation 2006, 113, 2630–2641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paulin, R.; Michelakis, E.D. The metabolic theory of pulmonary arterial hypertension. Circ. Res. 2014, 115, 148–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sutendra, G.; Dromparis, P.; Wright, P.; Bonnet, S.; Haromy, A.; Hao, Z.; McMurtry, M.S.; Michalak, M.; Vance, J.E.; Sessa, W.C.; et al. The role of Nogo and the mitochondria-endoplasmic reticulum unit in pulmonary hypertension. Sci. Transl. Med. 2011, 3, 88ra55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dromparis, P.; Paulin, R.; Stenson, T.H.; Haromy, A.; Sutendra, G.; Michelakis, E.D. Attenuating endoplasmic reticulum stress as a novel therapeutic strategy in pulmonary hypertension. Circulation 2013, 127, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cottrill, K.A.; Chan, S.Y. Metabolic dysfunction in pulmonary hypertension: The expanding relevance of the Warburg effect. Eur. J. Clin. Investig. 2013, 43, 855–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antigny, F.; Hautefort, A.; Meloche, J.; Belacel-Ouari, M.; Manoury, B.; Rucker-Martin, C.; Péchoux, C.; Potus, F.; Nadeau, V.; Tremblay, E.; et al. Potassium-channel subfamily k-member 3 (KCNK3) contributes to the development of pulmonary arterial hypertension. Circulation 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boucherat, O.; Chabot, S.; Antigny, F.; Perros, F.; Provencher, S.; Bonnet, S. Potassium channels in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur. Respir. J. 2015, 46, 1167–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMurtry, M.S.; Bonnet, S.; Wu, X.; Dyck, J.R.B.; Haromy, A.; Hashimoto, K.; Michelakis, E.D. Dichloroacetate prevents and reverses pulmonary hypertension by inducing pulmonary artery smooth muscle cell apoptosis. Circ. Res. 2004, 95, 830–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michelakis, E.D.; McMurtry, M.S.; Wu, X.-C.; Dyck, J.R.B.; Moudgil, R.; Hopkins, T.A.; Lopaschuk, G.D.; Puttagunta, L.; Waite, R.; Archer, S.L. Dichloroacetate, a metabolic modulator, prevents and reverses chronic hypoxic pulmonary hypertension in rats: Role of increased expression and activity of voltage-gated potassium channels. Circulation 2002, 105, 244–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diebold, I.; Hennigs, J.K.; Miyagawa, K.; Li, C.G.; Nickel, N.P.; Kaschwich, M.; Cao, A.; Wang, L.; Reddy, S.; Chen, P.-I.; et al. BMPR2 preserves mitochondrial function and DNA during reoxygenation to promote endothelial cell survival and reverse pulmonary hypertension. Cell Metab. 2015, 21, 596–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fessel, J.P.; Flynn, C.R.; Robinson, L.J.; Penner, N.L.; Gladson, S.; Kang, C.J.; Wasserman, D.H.; Hemnes, A.R.; West, J.D. Hyperoxia synergizes with mutant bone morphogenic protein receptor 2 to cause metabolic stress, oxidant injury, and pulmonary hypertension. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2013, 49, 778–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomez-Arroyo, J.; Mizuno, S.; Szczepanek, K.; van Tassell, B.; Natarajan, R.; dos Remedios, C.G.; Drake, J.I.; Farkas, L.; Kraskauskas, D.; Wijesinghe, D.S.; et al. Metabolic gene remodeling and mitochondrial dysfunction in failing right ventricular hypertrophy due to pulmonary arterial hypertension. Circ. Heart Fail. 2013, 6, 136–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sutendra, G.; Dromparis, P.; Paulin, R.; Zervopoulos, S.; Haromy, A.; Nagendran, J.; Michelakis, E.D. A metabolic remodeling in right ventricular hypertrophy is associated with decreased angiogenesis and a transition from a compensated to a decompensated state in pulmonary hypertension. J. Mol. Med. 2013, 91, 1315–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Archer, S.L.; Fang, Y.-H.; Ryan, J.J.; Piao, L. Metabolism and bioenergetics in the right ventricle and pulmonary vasculature in pulmonary hypertension. Pulm. Circ. 2013, 3, 144–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cline, S.D. Mitochondrial DNA damage and its consequences for mitochondrial gene expression. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2012, 1819, 979–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barja, G.; Herrero, A. Oxidative damage to mitochondrial DNA is inversely related to maximum life span in the heart and brain of mammals. FASEB J. 2000, 14, 312–318. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yakes, F.M.; Van Houten, B. Mitochondrial DNA damage is more extensive and persists longer than nuclear DNA damage in human cells following oxidative stress. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1997, 94, 514–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tadi, S.K.; Sebastian, R.; Dahal, S.; Babu, R.K.; Choudhary, B.; Raghavan, S.C. Microhomology-mediated end joining is the principal mediator of double-strand break repair during mitochondrial DNA lesions. Mol. Biol. Cell 2016, 27, 223–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grishko, V.; Solomon, M.; Wilson, G.L.; LeDoux, S.P.; Gillespie, M.N. Oxygen radical-induced mitochondrial DNA damage and repair in pulmonary vascular endothelial cell phenotypes. Am. J. Physiol. 2001, 280, L1300–L1308. [Google Scholar]

- López-López, L.; Nieves-Plaza, M.; del Castro, M.R.; Font, Y.M.; Torres-Ramos, C.A.; Vilá, L.M.; Ayala-Peña, S. Mitochondrial DNA damage is associated with damage accrual and disease duration in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus 2014, 23, 1133–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akdogan, A.; Kilic, L.; Dogan, I.; Okutucu, S.; Er, E.; Kaya, B.; Coplu, L.; Calguneri, M.; Tokgozoglu, L.; Ertenli, I. Pulmonary hypertension in systemic lupus erythematosus: Pulmonary thromboembolism is the leading cause. J. Clin. Rheumatol. Pract. Rep. Rheum. Musculoskelet. Dis. 2013, 19, 421–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asherson, R.A. Pulmonary hypertension in systemic lupus erythematosus. J. Rheumatol. 1990, 17, 414–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fetterman, J.L.; Holbrook, M.; Westbrook, D.G.; Brown, J.A.; Feeley, K.P.; Bretón-Romero, R.; Linder, E.A.; Berk, B.D.; Weisbrod, R.M.; Widlansky, M.E.; et al. Mitochondrial DNA damage and vascular function in patients with diabetes mellitus and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2016, 15, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, Y.; Ren, X.; Gowda, A.S.P.; Shan, Y.; Zhang, L.; Yuan, Y.-S.; Patel, R.; Wu, H.; Huber-Keener, K.; Yang, J.W.; et al. Interaction of Sirt3 with OGG1 contributes to repair of mitochondrial DNA and protects from apoptotic cell death under oxidative stress. Cell Death Dis. 2013, 4, e731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paulin, R.; Dromparis, P.; Sutendra, G.; Gurtu, V.; Zervopoulos, S.; Bowers, L.; Haromy, A.; Webster, L.; Provencher, S.; Bonnet, S.; et al. Sirtuin 3 deficiency is associated with inhibited mitochondrial function and pulmonary arterial hypertension in rodents and humans. Cell Metab. 2014, 20, 827–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szczesny, B.; Brunyanszki, A.; Olah, G.; Mitra, S.; Szabo, C. Opposing roles of mitochondrial and nuclear PARP1 in the regulation of mitochondrial and nuclear DNA integrity: Implications for the regulation of mitochondrial function. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014, 42, 13161–13173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, E.F.; Scheibye-Knudsen, M.; Brace, L.E.; Kassahun, H.; SenGupta, T.; Nilsen, H.; Mitchell, J.R.; Croteau, D.L.; Bohr, V.A. Defective mitophagy in XPA via PARP1 hyperactivation and NAD/+SIRT1 Reduction. Cell 2014, 157, 882–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2016 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ranchoux, B.; Meloche, J.; Paulin, R.; Boucherat, O.; Provencher, S.; Bonnet, S. DNA Damage and Pulmonary Hypertension. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 990. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms17060990

Ranchoux B, Meloche J, Paulin R, Boucherat O, Provencher S, Bonnet S. DNA Damage and Pulmonary Hypertension. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2016; 17(6):990. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms17060990

Chicago/Turabian StyleRanchoux, Benoît, Jolyane Meloche, Roxane Paulin, Olivier Boucherat, Steeve Provencher, and Sébastien Bonnet. 2016. "DNA Damage and Pulmonary Hypertension" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 17, no. 6: 990. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms17060990

APA StyleRanchoux, B., Meloche, J., Paulin, R., Boucherat, O., Provencher, S., & Bonnet, S. (2016). DNA Damage and Pulmonary Hypertension. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 17(6), 990. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms17060990