Experimental Models of Status Epilepticus and Neuronal Injury for Evaluation of Therapeutic Interventions

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Epilepsy

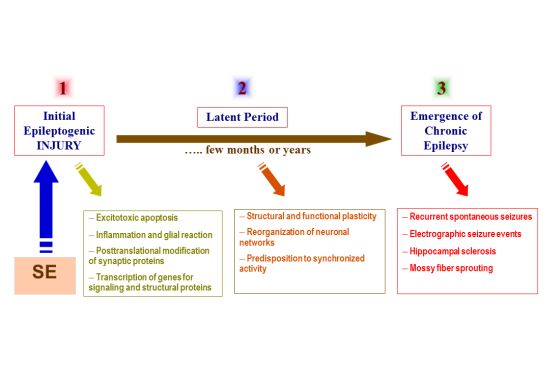

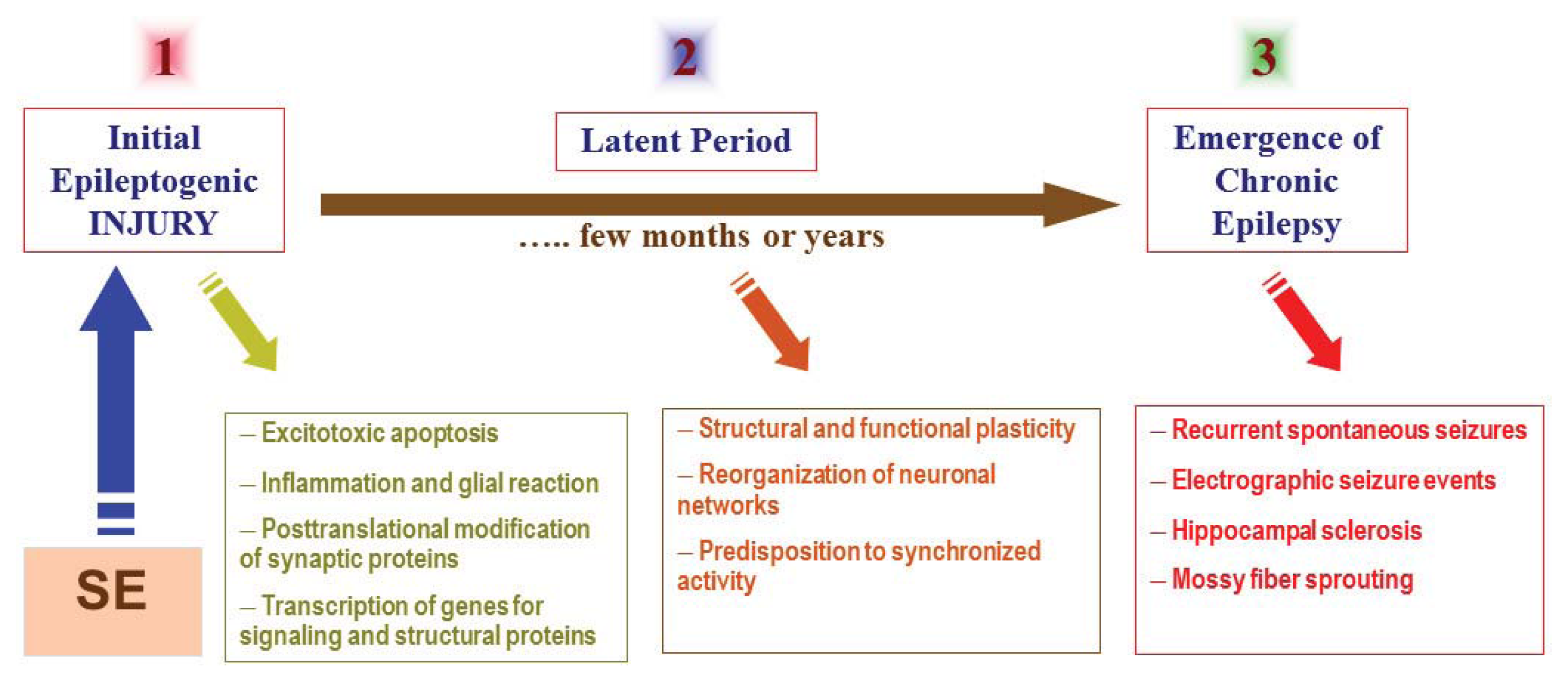

1.2. Status Epilepticus

- Exhibit appropriate seizure phenotype

- Consistent with the neuropathological features of human SE

- Exhibit appropriate latent period following initial insult

- Show post-SE chronic hyperexcitability and neuronal plasticity

- Express spontaneous seizures following a latent period

- Respond to drug therapy and exhibit resistance to certain anticonvulsants

- Allow rapid screening of novel compounds

2. Electrical Stimulation Models of SE

2.1. Perforant Path Stimulation Model

2.1.1. Methodology

2.1.2. Model Features

2.1.3. Pros and Cons

2.2. Self-Sustaining Stimulation Model

2.2.1. Methodology

2.2.2. Model Features

2.2.3. Pros and Cons

3. Pharmacological Models of SE

3.1. Kainic Acid Model

3.1.1. Methodology

3.1.2. Model Features

3.1.3. Pros and Cons

3.2. Pilocarpine Model

3.2.1. Methodology

3.2.2. Model Features

3.2.3. Pros and Cons

3.3. Lithium-Pilocarpine Combination Model

3.3.1. Methodology

3.3.2. Features

3.3.3. Pros and Cons

3.4. Organophosphate Pesticide Model

3.4.1. Methodology

3.4.2. Pros and Cons

3.5. Flurothyl Model

3.6. Cobalt-Homocysteine Model

4. Thermal Models

4.1. Hyperthermia (Complex Febrile) Model

4.1.1. Methodology

4.1.2. Pros and Cons

5. In Vitro Models of SE

5.1. Low Magnesium Model in Slices

5.2. High Potassium Model in Slices

5.3. 4-Aminopyridine Model in Slices

5.4. Organotypic Slice Culture Model

6. Refractory SE Models

6.1. Pilocarpine Model

6.2. KA Model

6.3. DFP Model

7. Morphological Approaches

7.1. Cell Necrosis and Apoptosis

7.1.1. Nissl Staining

7.1.2. TUNEL Assay

7.1.3. Fluoro-Jade B Staining

7.2. Neurodegeneration, Neurogenesis and Mossy Fiber Sprouting

7.2.1. Neurodegeneration

7.2.2. Neurogenesis

7.2.3. Mossy Fiber (MF) Sprouting

7.3. Neuroinflammation Markers

8. Conclusions and Perspectives

- Rapid onset of action and intermediate duration

- Ease of administration

- Broad spectrum of activity

- Minimal sedative potential

- Aqueous solubility for i.v. solution formulations

- Effective against convulsive and non-convulsive SE

- Lack of tolerance upon repeated administration

- Possess antiseizure activity for maintenance therapy

- Should be effective when given late (>40-min) after SE onset

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

Disclaimer Note

Abbreviations

| ACSF | Artificial cerebrospinal fluid |

| AD | Afterdischarge |

| AED | Antiepileptic drug |

| 4-AP | 4-Aminopyridine |

| DH | Dentate hilus |

| DFP | Diisopropylfluorophosphate |

| EEG | Electroencephalogram |

| FJB | Fluoro-Jade B |

| HCTL | Homocysteine thiolactone |

| KA | Kainic acid |

| MF | Mossy fibers |

| OP | Organophosphate |

| PPS | Perforant path stimulation |

| SSL | self-sustaining limbic |

| SE | Status epilepticus |

| TLE | Temporal lobe epilepsy |

References

- Jacobs, M.P.; Leblanc, G.G.; Brooks-Kayal, A.; Jensen, F.E.; Lowenstein, D.H.; Noebels, J.L.; Noebels, J.L.; Spencer, D.D.; Swann, J.W. Curing epilepsy: Progress and future directions. Epilepsy Behav 2009, 14, 438–445. [Google Scholar]

- Hesdorffer, D.C.; Beck, V.; Begley, C.E.; Bishop, M.L.; Cushner-Weinstein, S.; Holmes, G.L.; Shafer, P.O.; Sirven, J.I.; Austin, J.K. Research implications of the Institute of Medicine Report, Epilepsy Across the Spectrum: Promoting health and understanding. Epilepsia 2013, 54, 207–216. [Google Scholar]

- Pitkanen, A.; Immonen, R.J.; Grohn, O.H.; Kharatishvili, I. From traumatic brain injury to posttraumatic epilepsy: What animal models tell us about the process and treatment options. Epilepsia 2009, 50, 21–29. [Google Scholar]

- Sutula, T.P. Mechanisms of epilepsy progression: Current theories and perspectives from neuroplasticity in adulthood and development. Epilepsy Res 2004, 60, 161–171. [Google Scholar]

- Dudek, F.E.; Staley, K.J. The time course of acquired epilepsy: Implications for therapeutic intervention to suppress epileptogenesis. Neurosci. Lett 2011, 497, 240–246. [Google Scholar]

- Dudek, F.E.; Bertram, H.; Staley, K.J. Antiepileptogenesis therapy with levetiracetam: Data from kindling versus status epilepticus models. Epilepsy Curr 2008, 8, 28–30. [Google Scholar]

- Pitkänen, A.; Lukasiuk, K. Mechanisms of epileptogenesis and potential treatment targets. Lancet Neurol 2011, 10, 173–186. [Google Scholar]

- Duncan, J.S.; Sander, J.W.; Sisodiya, S.M.; Walker, M.C. Adult epilepsy. Lancet 2006, 367, 1087–1100. [Google Scholar]

- Babb, T.L. Synaptic reorganizations in human and rat hippocampal epilepsy. Adv. Neurol 1999, 79, 763–779. [Google Scholar]

- Engel, J., Jr. Clinical neurophysiology, neuroimaging, and the surgical treatment of epilepsy. Curr. Opin. Neurol. Neurosurg. 1993, 6, 240–249. [Google Scholar]

- Cendes, F. Progressive hippocampal and extrahippocampal atrophy in drug resistant epilepsy. Curr. Opin. Neurol 2005, 18, 173–177. [Google Scholar]

- Delgado-Escueta, A.V.; Wasterlain, C.; Treiman, D.M.; Porter, R.J. Status epilepticus: Summary. Adv. Neurol 1983, 34, 537–541. [Google Scholar]

- DeLorenzo, R.J.; Towne, A.R.; Pellock, J.M.; Ko, D. Status epilepticus in children, adults, and the elderly. Epilepsia 1992, 33, S15–S25. [Google Scholar]

- Lothman, E. The biochemical basis and pathophysiology of status epilepticus. Neurology 1990, 40, 13–23. [Google Scholar]

- Knake, S.; Hamer, H.M.; Rosenow, F. Status epilepticus: A critical review. Epilepsy Behav 2009, 15, 10–14. [Google Scholar]

- Brophy, G.M.; Bell, R.; Claassen, J.; Alldredge, B.; Bleck, T.P.; Glauser, T.; Laroche, S.M.; Riviello, J.J., Jr; Shutter, L.; Sperling, M.R.; et al. Guidelines for the evaluation and management of status epilepticus. Neurocrit. Care 2012, 17, 3–23. [Google Scholar]

- Silbergleit, R.; Durkalski, V.; Lowenstein, D.; Conwit, R.; Pancioli, A.; Palesch, Y.; Barsan, W. NETT Investigators. Intramuscular versus intravenous therapy for prehospital status epilepticus. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012, 366, 591–600. [Google Scholar]

- Mayer, S.A.; Claassen, J.; Lokin, J.; Mendelsohn, F.; Dennis, L.J.; Fitzsimmons, B.F. Refractory status epilepticus: Frequency, risk factors, and impact on outcome. Arch. Neurol 2002, 59, 205–210. [Google Scholar]

- Wheless, J.W.; Treiman, D.M. The role of the newer antiepileptic drugs in the treatment of generalized convulsive status epilepticus. Epilepsia 2008, 49, 74–78. [Google Scholar]

- Yaffe, K.; Lowenstein, D.H. Prognostic factors of pentobarbital therapy for refractory generalized status epilepticus. Neurology 1993, 43, 895–900. [Google Scholar]

- Krishnamurthy, K.B.; Drislane, F.W. Relapse and survival after barbiturate anesthetic treatment of refractory status epilepticus. Epilepsia 1996, 37, 863–867. [Google Scholar]

- Stecker, M.M.; Kramer, T.H.; Raps, E.C.; O’Meeghan, R.; Dulaney, E.; Skaar, D.J. Treatment of refractory status epilepticus with propofol: Clinical and pharmacokinetic findings. Epilepsia 1998, 39, 18–26. [Google Scholar]

- Claassen, J.; Hirsch, L.J.; Emerson, R.G.; Mayer, S.A. Treatment of refractory status epilepticus with pentobarbital, propofol, or midazolam: A systematic review. Epilepsia 2002, 43, 146–153. [Google Scholar]

- Nadler, J.V. Kainic acid: Neurophysiological and neurotoxic actions. Life Sci 1979, 24, 289–299. [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Ari, Y. Limbic seizure and brain damage produced by kainic acid: Mechanisms and relevance to human temporal lobe epilepsy. Neuroscience 1985, 14, 375–403. [Google Scholar]

- Clifford, D.B.; Olney, J.W.; Maniotis, A.; Collins, R.C.; Zorumski, C.F. The functional anatomy and pathology of lithium-pilocarpine and high-dose pilocarpine seizures. Neuroscience 1987, 23, 953–968. [Google Scholar]

- Turski, W.A.; Cavalheiro, E.A.; Schwarz, M.; Czuczwar, S.J.; Kleinrok, Z.; Turski, L. Limbic seizures produced by pilocarpine in rats: Behavioural, electroencephalographic and neuropathological study. Behav. Brain Res 1983, 9, 315–335. [Google Scholar]

- Sloviter, R.S. Epileptic brain damage in rats induced by sustained electrical stimulation of the perforant path. I. Acute electrophysiological and light microscopic studies. Brain Res. Bull 1983, 10, 675–697. [Google Scholar]

- Kapur, J.; Macdonald, R.L. Rapid seizure-induced reduction of benzodiazepine and Zn2+ sensitivity of hippocampal dentate granule cell GABA-A receptors. J. Neurosci 1997, 17, 7532–7540. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, D.M.; Esmaeil, N.; Maren, S.; Macdonald, R.L. Characterization of pharmacoresistance to benzodiazepine in the rat Li-Pilocarpine model of status epilepticus. Epilepsy Res 2002, 50, 301–312. [Google Scholar]

- Rao, M.S.; Hattiangady, B.; Reddy, D.S.; Shetty, A.K. Hippocampal neurodegeneration, spontaneous seizures, and mossy fiber sprouting in the F344 rat model of temporal lobe epilepsy. J. Neurosci. Res. 2006, 83, 1088–1105. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, A.K.; Reams, R.Y.; Jordan, W.H.; Miller, M.A.; Thacker, H.L.; Snyder, P.W. Mesial temporal lobe epilepsy: Pathogenesis, induced rodent models and lesions. Toxicol. Pathol. 2007, 35, 984–999. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, P.A.; White, A.M.; Clark, S.; Ferraro, D.J.; Swiercz, W.; Staley, K.J.; Dudek, F.E. Development of spontaneous recurrent seizures after kainate-induced status epilepticus. J. Neurosci 2009, 29, 2103–2112. [Google Scholar]

- White, A.; Williams, P.A.; Hellier, J.L.; Clark, S.; Dudek, E.F.; Staley, K.J. EEG spike activity precedes epilepsy after kainate-induced status epilepticus. Epilepsia 2010, 51, 371–383. [Google Scholar]

- Loscher, W. Animal models of epilepsy for the development of antiepileptogenic and disease-modifying drugs. A comparison of the pharmacology of kindling and post-status epilepticus models of temporal lobe epilepsy. Epilepsy Res 2002, 50, 105–123. [Google Scholar]

- Reddy, D.S.; Gangisetty, O.; Briyal, S. Disease-modifying activity of progesterone in the hippocampus kindling model of epileptogenesis. Neuropharmacology 2010, 59, 573–581. [Google Scholar]

- Reddy, D.S.; Kuruba, R.; Wu, X. Comparative Characterization of Organophosphate-intoxication and Lithium-pilocarpine Models of Refractory Status Epilepticus and Neurodegeneration. Proceedings of the 4th Biennial North American Epilepsy Congress, American Epilepsy Society, San Diego, December 2–6, 2012. AES Annual Meeting Abstract 2.028.

- Goodman, J.H. Experimental Models of Status Epilepticus. In Neuropharmacology Methods in Epilepsy Research; CRB Press LLC: New York, NY, USA, 1998; pp. 95–125. [Google Scholar]

- Reddy, D.S.; Mohan, A. Development and persistence of limbic epileptogenesis are impaired in mice lacking progesterone receptors. J. Neurosci 2011, 31, 650–658. [Google Scholar]

- Galanopoulou, A.S.; Buckmaster, P.S.; Staley, K.J.; Moshé, S.L.; Perucca, E.; Engel, J., Jr; Löscher, W.; Noebels, J.L.; Pitkänen, A.; Stables, J.; White, H.S.; et al. Epilepsia 2012, 53, 571–582.

- Sloviter, R.S. Decreased hippocampal inhibition and a selective loss of interneurons in experimental epilepsy. Science 1987, 235, 73–76. [Google Scholar]

- Tilelli, C.Q.; Del Vecchio, F.; Fernandes, A.; Garcia-Cairasco, N. Different types of status epilepticus lead to different levels of brain damage in rats. Epilepsy Behav 2005, 7, 401–410. [Google Scholar]

- Lothman, E.W.; Collins, R.C. Kainic acid induced limbic seizures: Metabolic, behavioral, electroencephalographic and neuropathological correlates. Brain Res 1981, 218, 299–318. [Google Scholar]

- Vicedomini, J.P.; Nadler, J.V. A model of status epilepticus based on electrical stimulation of hippocampal afferent pathways. Exp. Neurol 1987, 96, 681–691. [Google Scholar]

- Lothman, E.W.; Bertram, E.H.; Bekenstein, J.W.; Perlin, J.B. Self-sustaining limbic status epilepticus induced by ‘continuous’ hippocampal stimulation: Electrographic and behavioral characteristics. Epilepsy Res 1989, 3, 107–119. [Google Scholar]

- McIntyre, D.C.; Stokes, K.A.; Edson, N. Status epilepticus following stimulation of a kindled hippocampal focus in intact and commissurotomized rats. Exp. Neurol 1986, 94, 554–570. [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Ari, Y.; Tremblay, E.; Riche, D.; Ghilini, G.; Naquet, R. Electrographic, clinical and pathological alterations following systemic administration of kainic acid, bicuculline or pentetrazole: Metabolic mapping using the deoxyglucose method with special reference to the pathology of epilepsy. Neuroscience 1981, 6, 1361–1391. [Google Scholar]

- Scerrati, M.; Onofrj, M.; Pacifici, L.; Pola, P.; Ramacci, M.T.; Rossi, G.F. Electrocerebral and behavioural analysis of systemic kainic acid-induced epilepsy in the rat. Drugs Exp. Clin. Res 1986, 12, 671–680. [Google Scholar]

- Sperk, G. Kainic acid seizures in the rat. Prog. Neurobiol 1994, 42, 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Sperk, G.; Lassmann, H.; Baran, H.; Kish, S.J.; Seitelberger, F.; Hornykiewicz, O. Kainic acid induced seizures: Neurochemical and histopathological changes. Neuroscience 1983, 10, 1301–1315. [Google Scholar]

- Sperk, G.; Lassmann, H.; Baran, H.; Seitelberger, F.; Hornykiewicz, O. Kainic acid-induced seizures: Dose-relationship of behavioural, neurochemical and histopathological changes. Brain Res 1985, 338, 289–295. [Google Scholar]

- Sutula, T.; Harrison, C.; Steward, O. Chronic epileptogenesis induced by kindling of the entorhinal cortex: The role of the dentate gyrus. Brain Res 1986, 385, 291–299. [Google Scholar]

- Turski, W.A.; Cavalheiro, E.A.; Bortolotto, Z.A.; Mello, L.M.; Schwarz, M.; Turski, L. Seizures produced by pilocarpine in mice: A behavioral, electroencephalographic and morphological analysis. Brain Res 1984, 321, 237–253. [Google Scholar]

- Turski, L.; Cavalheiro, E.A.; Sieklucka-Dziuba, M.; Ikonomidou-Turski, C.; Czuczwar, S.J.; Turski, W.A. Seizures produced by pilocarpine: Neuropathological sequelae and activity of glutamate decarboxylase in the rat forebrain. Brain Res 1986, 398, 37–48. [Google Scholar]

- Turski, W.A.; Czuczwar, S.J.; Kleinrok, Z.; Schwarz, M.; Turski, L. Intraamygdaloid morphine produce., seizures and brain damage in rats. Life Sci 1983, 33, 615–618. [Google Scholar]

- Turski, W.A.; Cavalheiro, E.A.; Turski, L.; Kleinrok, Z. Intrahippocampal bethanechol in rats: Behavioural, electroencephalographic and neuropathological correlates. Behav. Brain Res 1983, 7, 361–370. [Google Scholar]

- Turski, W.A.; Czuczwar, S.J.; Kleinrok, Z.; Turski, L. Cholinomimetics produce seizures and brain damage in rats. Experientia 1983, 39, 1408–1411. [Google Scholar]

- Cavalheiro, E.A.; Silva, D.F.; Turski, W.A.; Calderazzo-Filho, L.S.; Bortolotto, Z.A.; Turski, L. The susceptibility of rats to pilocarpine-induced seizures is age-dependent. Brain Res 1987, 465, 43–58. [Google Scholar]

- Jope, R.S.; Morrisett, R.A. Neurochemical consequences of status epilepticus induced in rats by coadministration of lithium and pilocarpine. Exp. Neurol 1986, 93, 404–414. [Google Scholar]

- Morrisett, R.A.; Jope, R.S.; Snead, O.C. Effects of drugs on the initiation and maintenance of status epilepticus induced by administration of pilocarpine to lithium-pretreated rats. Exp. Neurol 1987, 97, 193–200. [Google Scholar]

- McDonough, J.H., Jr; Dochterman, L.W.; Smith, C.D.; Shih, T.M. Protection against nerve agent-induced neuropathology, but not cardiac pathology, is associated with the anticonvulsant action of drug treatment. Neurotoxicology 1995, 16, 123–132. [Google Scholar]

- Deshpande, L.S.; Carter, D.S.; Blair, R.E.; Delorenzo, R.J. Development of a prolonged calcium plateau in hippocampal neurons in rats surviving status epilepticus induced by the organophosphate diisopropylfluorophosphate. Toxicol. Sci 2010, 116, 623–631. [Google Scholar]

- Todorovic, M.S.; Cowan, M.L.; Balint, C.A.; Sun, C.; Kapur, J. Characterization of status epilepticus induced by two organophosphates in rats. Epilepsy Res 2012, 101, 268–276. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, W.M.; King, W.T. Pharmacogenetic factor in the convulsive responses of mice to flurothyl. Experientia 1967, 23, 214–215. [Google Scholar]

- Wasterlain, C.G. Developmental brain damage after chemically induced epileptic seizures. Eur. Neurol 1975, 3, 495–498. [Google Scholar]

- Sperber, E.F.; Moshé, S.L. Age-related differences in seizure susceptibility to flurothyl. Dev. Brain Res 1988, 39, 295–297. [Google Scholar]

- Velíšková, J.; Velíšek, L.; Nunes, M.; Moshé, S. Developmental regulation of regional functionality of substantia nigra GABAA receptors involved in seizures. Eur. J. Pharmacol 1996, 309, 167–173. [Google Scholar]

- Walton, N.Y.; Treiman, D.M. Experimental secondarily generalized convulsive status epilepticus induced by d,l-homocysteine thiolactone. Epilepsy Res 1988, 2, 79–86. [Google Scholar]

- Dubé, C.; Chen, K.; Eghbal-Ahmadi, M.; Brunson, K.; Soltesz, I.; Baram, T.Z. Prolonged febrile seizures in the immature rat model enhance hippocampal excitability long term. Ann. Neurol 2000, 47, 336–344. [Google Scholar]

- Dubé, C.; Richichi, C.; Bender, R.A.; Chung, G.; Litt, B.; Baram, T.Z. Temporal lobe epilepsy after experimental prolonged febrile seizures: Prospective analysis. Brain 2006, 129, 911–922. [Google Scholar]

- Dubé, C.; Vezzani, A.; Behrens, M.; Bartfai, T.; Baram, T.Z. Interleukin-1beta contributes to the generation of experimental febrile seizures. Ann. Neurol 2005, 57, 152–155. [Google Scholar]

- Dubé, C.M.; Ravizza, T.; Hamamura, M.; Zha, Q.; Keebaugh, A.; Fok, K.; Andres, A.L.; Nalcioglu, O.; Obenaus, A.; Vezzani, A.; et al. Epileptogenesis provoked by prolonged experimental febrile seizures: Mechanisms and biomarkers. J. Neurosci 2010, 30, 7484–7494. [Google Scholar]

- Baram, T.Z.; Gerth, A.; Schultz, L. Febrile seizures: An appropriate-aged model suitable for long-term studies. Dev. Brain. Res 1997, 98, 265–270. [Google Scholar]

- Dubé, C.; Yu, H.; Nalcioglu, O.; Baram, T.Z. Serial MRI after experimental febrile seizures: Altered T2 signal without neuronal death. Ann. Neurol 2004, 56, 709–714. [Google Scholar]

- Dreier, J.P.; Zhang, C.L.; Heinemann, U. Phenytoin, phenobarbital, and midazolam fail to stop status epilepticus-like activity induced by low magnesium in rat entorhinal slices, but can prevent its development. Acta Neurol. Scand 1998, 98, 154–160. [Google Scholar]

- Fueta, Y.; Kunugita, N.; Schwarz, W. Antiepileptic action induced by a combination of vigabatrin and tiagabine. Neuroscience 2005, 132, 335–345. [Google Scholar]

- Pfeiffer, M.; Draguhn, A.; Meierkord, H.; Heinemann, U. Effects of gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) agonists and GABA uptake inhibitors on pharmacosensitive and pharmacoresistant epileptiform activity in vitro. Br. J. Pharmacol 1996, 119, 569–577. [Google Scholar]

- Balestrino, M.; Aitken, P.G.; Somjen, G.G. The effects of moderate changes of extracellular K+ and Ca2+ on synaptic and neural function in the CA1 region of the hippocampal slice. Brain Res 1986, 377, 229–239. [Google Scholar]

- Poolos, N.P.; Mauk, M.D.; Kocsis, J.D. Activity-evoked increases in extracellular potassium modulate presynaptic excitability in the CA1 region of the hippocampus. Neurophysiology 1987, 58, 404–416. [Google Scholar]

- Poolos, N.P.; Kocsis, J.D. Elevated extracellular potassium concentration enhances synaptic activation of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors in hippocampus. Brain Res 1990, 508, 7–12. [Google Scholar]

- Spyker, D.A.; Lynch, C.; Shabanowitz, J.; Sinn, J.A. Poisoning with 4-aminopyridine: Report of three cases. Clin. Toxicol 1980, 16, 487–497. [Google Scholar]

- Salazar, P.; Tapia, R.; Rogawski, M.A. Effects of neurosteroids on epileptiform activity induced by picrotoxin and 4-aminopyridine in the rat hippocampal slice. Epilepsy Res 2003, 55, 71–82. [Google Scholar]

- Reddy, D.S. Testosterone modulation of seizure susceptibility is mediated by neurosteroids 3alpha-androstanediol and 17beta-estradiol. Neuroscience 2004, 129, 195–207. [Google Scholar]

- Avoli, M.; Perreault, P.; Olivier, A.; Villemure, J.G. 4-Aminopyridine induces a long-lasting depolarizing GABA-ergic potential in human neocortical and hippocampal neurons maintained in vitro. Neurosci. Lett 1988, 94, 327–332. [Google Scholar]

- Gähwiler, B.H. Organotypic cultures of neural tissue. Trends Neurosci 1988, 11, 484–489. [Google Scholar]

- Stoppini, L.; Buchs, P.A.; Muller, D. A simple method for organotypic cultures of nervous tissue. J. Neurosci. Methods 1991, 37, 173–182. [Google Scholar]

- Muller, D.; Buchs, P.A.; Stoppini, L. Time course of synaptic development in hippocampal organotypic cultures. Dev. Brain Res 1993, 71, 93–100. [Google Scholar]

- Buchs, P.A.; Stoppini, L.; Muller, D. Structural modifications associated with synaptic development in area CA1 of rat hippocampal organotypic cultures. Dev. Brain Res 1993, 71, 81–91. [Google Scholar]

- Gähwiler, B.H.; Capogna, M.; Debanne, D.; McKinney, R.A.; Thompson, S.M. Organotypic slice cultures: A technique has come of age. Trends Neurosci 1997, 20, 471–477. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, B.S.; Kapur, J. A combination of ketamine and diazepam synergistically controls refractory status epilepticus induced by cholinergic stimulation. Epilepsia 2008, 49, 248–255. [Google Scholar]

- Glien, M.; Brandt, C.; Potschka, H.; Voigt, H.; Ebert, U.; Löscher, W. Repeated low-dose treatment of rats with pilocarpine: Low mortality but high proportion of rats developing epilepsy. Epilepsy Res 2001, 46, 111–119. [Google Scholar]

- Hellier, J.L.; Patrylo, J.R.; Buckmaster, P.S.; Dudek, F.E. Recurrent spontaneous motor seizures after repeated low-dose systemic treatment with kainate: Assessment of a rat model of temporal lobe epilepsy. Epilepsy Res 1998, 31, 73–84. [Google Scholar]

- Goodkin, H.P.; Kapur, J. The impact of diazepam’s discovery on the treatment and understanding of status epilepticus. Epilepsia 2009, 50, 2011–2018. [Google Scholar]

- Naylor, D.E.; Liu, H.; Wasterlain, C.G. Trafficking of GABA-A receptors, loss of inhibition, and a mechanism for pharmacoresistance in status epilepticus. J. Neurosci 2005, 25, 7724–7733. [Google Scholar]

- Kadriu, B.; Guidotti, A.; Costa, E.; Auta, J. Imidazenil, a nonsedating anticonvulsant benzodiazepine, is more potent than diazepam in protecting against DFP-induced seizures and neuronal damage. Toxicology 2009, 256, 164–174. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Lein, P.J.; Liu, C.; Bruun, D.A.; Tewolde, T.; Ford, G.; Ford, B.D. Spatiotemporal pattern of neuronal injury induced by DFP in rats: A model for delayed neuronal cell death following acute OP intoxication. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol 2011, 253, 261–269. [Google Scholar]

- Sloviter, R.S. Feedforward and feedback inhibition of hippocampal principal cell activity evoked by perforant path stimulation: GABA-mediated mechanisms that regulate excitability in vivo. Hippocampus 1991, 1, 31–40. [Google Scholar]

- Sloviter, R.S.; Dean, E.; Sollas, A.L.; Goodman, J.H. Apoptosis and necrosis induced in different hippocampal neuron populations by repetitive perforant path stimulation in the rat. J. Comp. Neurol 1996, 366, 516–533. [Google Scholar]

- Gorter, J.A.; Vliet, E.A.; Aronica, E.; Lopes da Silva, F.H. Progression of spontaneous seizures after van status epilepticus is associated with mossy fibre sprouting and extensive bilateral loss of hilar parvalbumin and somatostatin-immunoreactive neurons. Eur. J. Neurosci 2001, 13, 657–669. [Google Scholar]

- Mazarati, A.; Lu, X.; Shinmei, S.; Badie-Mahdavi, H.; Bartfai, T. Patterns of seizures, hippocampal injury and neurogenesis in three models of status epilepticus in galanin receptor type 1 (GalR1) knockout mice. Neuroscience 2004, 128, 431–441. [Google Scholar]

- Ribak, C.E.; Tran, P.H.; Spigelman, I.; Okazaki, M.M.; Nadler, J.V. Status epilepticus-induced hilar basal dendrites on rodent granule cells contribute to recurrent excitatory circuitry. J. Comp. Neurol 2000, 428, 240–253. [Google Scholar]

- Schwob, J.E.; Fuller, T.; Price, J.L.; Olney, J.W. Widespread patterns of neuronal damage following systemic or intracerebral injections of kainic acid: A histological study. Neuroscience 1980, 5, 991–1014. [Google Scholar]

- Bastlund, J.F.; Jennum, P.; Mohapel, P.; Penschuck, S.; Watson, W.P. Spontaneous epileptic rats show changes in sleep architecture and hypothalamic pathology. Epilepsia 2005, 46, 934–938. [Google Scholar]

- Racine, R.J. Modification of seizure activity by electrical stimulation. II. Motor seizure. Electroencephalogr. Clin. Neurophysiol 1972, 32, 281–294. [Google Scholar]

- Vezzani, A.; Conti, M.; de Luigi, A.; Ravizza, T.; Moneta, D.; Marchesi, F.; de Simoni, M.G. Interleukin-1β immunoreactivity and microglia are enhanced in the rat hippocampus by focal kainate application: Functional evidence for enhancement of electrographic seizures. J. Neurosci. 1999, 19, 5054–5065. [Google Scholar]

- Cavazos, J.E.; Sutula, T.P. Progressive neuronal loss induced by kindling: A possible mechanism for mossy fiber synaptic reorganization and hippocampal sclerosis. Brain Res 1990, 527, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Brandt, C.; Glien, M.; Potschka, H.; Volk, H.; Loscher, W. Epileptogenesis and neuropathology after different types of status epilepticus induced by prolonged electrical stimulation of the basolateral amygdala in rats. Epilepsy Res 2003, 55, 83–103. [Google Scholar]

- Bertram, E.H.; Lothman, E.W. NMDA receptor antagonists and limbic status epilepticus: A comparison with standard anticonvulsants. Epilepsy Res 1990, 5, 177–184. [Google Scholar]

- Bertram, E.H.; Lothman, E.W.; Lenn, N.J. The hippocampus in experimental chronic epilepsy: A morphometric analysis. Ann. Neurol 1990, 27, 43–48. [Google Scholar]

- Lothman, E.W.; Bertram, E.H. Epileptogenic effects of status epilepticus. Epilepsia 1993, 34, S59–S70. [Google Scholar]

- Lothman, E.W.; Bertram, E.H.; Kapur, J.; Stringer, J.L. Recurrent spontaneous hippocampal seizures in the rat as a chronic sequela to limbic status epilepticus. Epilepsy Res 1990, 6, 110–118. [Google Scholar]

- McIntyre, D.C.; Nathanson, D.; Edson, N. A new model of partial status epilepticus based on kindling. Brain Res 1982, 250, 53–63. [Google Scholar]

- Olney, J.W.; Rhee, V.; Ho, O.L. Kainic acid: A powerful neurotoxic analogue of glutamate. Brain Res 1974, 77, 507–512. [Google Scholar]

- Collingridge, G.L.; Lester, R.A. Excitatory amino acid receptors in the vertebrate central nervous system. Pharmacol. Rev 1989, 41, 143–210. [Google Scholar]

- Sutula, T.; Cascino, G.; Cavazos, J.; Parada, I.; Ramirez, L. Mossy fiber synaptic reorganization in the epileptic human temporal lobe. Ann. Neurol 1989, 26, 321–30. [Google Scholar]

- Houser, C.R. Granule cell dispersion in the dentate gyrus of humans with temporal lobe epilepsy. Brain Res 1990, 535, 195–204. [Google Scholar]

- Tauck, D.L.; Nadler, J.V. Evidence of functional mossy fiber sprouting in hippocampal formation of kainic acid-treated rats. J. Neurosci 1985, 5, 1016–1022. [Google Scholar]

- Treiman, D.M. Efficacy and safety of antiepileptic drugs: A review of controlled trials. Epilepsia 1987, 28, S1–S8. [Google Scholar]

- Kuruba, R.; Hattiangady, B.; Parihar, V.K.; Shuai, B.; Shetty, A.K. Differential susceptibility of interneurons expressing neuropeptide Y or parvalbumin in the aged hippocampus to acute seizure activity. PLoS One 2011, 6, e24493. [Google Scholar]

- Hattiangady, B.; Kuruba, R.; Shetty, A.K. Acute seizures in old age leads to a greater loss of CA1 pyramidal neurons, an increased propensity for developing chronic TLE and a severe cognitive dysfunction. Aging Dis 2011, 2, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Loscher, W.; Schmidt, D. Which animal models should be used in the search for new antiepileptic drugs? A proposal based on experimental and clinical considerations. Epilepsy Res 1988, 2, 145–181. [Google Scholar]

- Honchar, M.P.; Olney, J.W.; Sherman, W.R. Systemic cholinergic agents induce seizures and brain damage in lithium-treated rats. Science 1983, 220, 323–325. [Google Scholar]

- Mello, L.E.; Covolan, L. Spontaneous seizures preferentially injure interneurons in the pilocarpine model of chronic spontaneous seizures. Epilepsy Res 1996, 26, 123–129. [Google Scholar]

- Covolan, L.; Mello, L.E. Temporal profile of neuronal injury following pilocarpine or kainic acid-induced status epilepticus. Epilepsy Res 2000, 39, 133–152. [Google Scholar]

- Covolan, L.; Ribeiro, L.T.; Longo, B.M.; Mello, L.E. Cell damage and neurogenesis in the dentate granule cell layer of adult rats after pilocarpine- or kainate-induced status epilepticus. Hippocampus 2000, 10, 169–180. [Google Scholar]

- Buckmaster, P.S.; Zhang, G.F.; Yamawaki, R. Axon sprouting in a model of temporal lobe epilepsy creates a predominantly excitatory feedback circuit. J. Neurosci 2002, 22, 6650–6658. [Google Scholar]

- Mello, L.E.; Cavalheiro, E.A.; Tan, A.M.; Kupfer, W.R.; Pretorius, J.K.; Babb, T.L.; Finch, D.M. Circuit mechanisms of seizures in the pilocarpine model of chronic epilepsy: Cell loss and mossy fiber sprouting. Epilepsia 1993, 34, 985–995. [Google Scholar]

- Babb, T.L.; Kupfer, W.R.; Pretorius, J.K.; Crandall, P.H.; Levesque, M.F. Synaptic reorganization by mossy fibers in human epileptic fascia dentata. Neuroscience 1991, 42, 351–363. [Google Scholar]

- Buckmaster, P.S.; Haney, M.M. Factors affecting outcomes of pilocarpine treatment in a mouse model of temporal lobe epilepsy. Epilepsy Res 2012, 102, 153–159. [Google Scholar]

- Jope, R.S.; Morrisett, R.A.; Snead, O.C. Characterization of lithium potentiation of pilocarpine-induced status epilepticus in rats. Exp. Neurol 1986, 91, 471–480. [Google Scholar]

- Karalliedde, L.; Senanayake, N. Organophosphorus insecticide poisoning. Br. J. Anaesth 1989, 63, 736–750. [Google Scholar]

- Bajgar, J. Organophosphates/nerve agent poisoning: Mechanism of action, diagnosis, prophylaxis, and treatment. Adv. Clin. Chem 2004, 38, 151–216. [Google Scholar]

- Bouzarth, W.F.; Himwich, H.E. Mechanism of seizures induced by diisopropyl-flurophosphate (DFP). Am. J. Psychiatry 1952, 108, 847–855. [Google Scholar]

- McDonough, J.H., Jr; Shih, T.M. Neuropharmacological mechanisms of nerve agent-induced seizure and neuropathology. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 1997, 21, 559–579. [Google Scholar]

- Shih, T.M.; Duniho, S.M.; McDonough, J.H. Control of nerve agent-induced seizures is critical for neuroprotection and survival. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol 2003, 188, 69–80. [Google Scholar]

- Lánský, P.; Velíšková, J.; Velíšek, L. An indirect method for absorption rate estimation: Flurothyl-induced seizures. Bull. Math. Biol 1997, 59, 569–579. [Google Scholar]

- Treiman, D.M. Generalized convulsive status epilepticus in the adult. Epilepsia 1993, 34, S2–S11. [Google Scholar]

- Cendes, F. Febrile seizures and mesial temporal sclerosis. Curr. Opin. Neurol 2004, 17, 161–164. [Google Scholar]

- Shinnar, S.; Hesdorffer, D.C.; Nordli, D.R., Jr; Pellock, J.M.; O’Dell, C.O.; Lewis, D.V.; Frank, L.M.; Moshé, S.L.; Epstein, L.G.; Marmarou, A.; et al. Neurology 2008, 71, 170–176.

- Heida, J.G.; Teskey, G.C.; Pittman, Q.J. Febrile convulsions induced by the combination of lipopolysaccharide and low-dose kainic acid enhance seizure susceptibility, not epileptogenesis, in rats. Epilepsia 2005, 46, 1898–1905. [Google Scholar]

- Dudek, F.E.; Ekstrand, J.J.; Staley, K.J. Is neuronal death necessary for acquired epileptogenesis in the immature brain? Epilepsy Curr 2010, 10, 95–99. [Google Scholar]

- Galvan, M.; Grafe, P.; Bruggencate, G. Convulsant actions of 4-aminopyridine on the guinea-pig olfactory cortex slice. Brain Res 1982, 241, 75–86. [Google Scholar]

- Voskuyl, R.A.; Albus, H. Spontaneous epileptiform discharges in hippocampal slices induced by 4-aminopyridine. Brain Res 1985, 342, 54–66. [Google Scholar]

- Rutecki, P.A.; Lebeda, F.J.; Johnston, D. 4-Aminopyridine produces epileptiform activity in hippocampus and enhances synaptic excitation and inhibition. J. Neurophysiol 1987, 57, 1911–1924. [Google Scholar]

- Szente, M.; Baranyi, A. Mechanism of aminopyridine-induced ictal seizure activity in the cat neocortex. Brain Res 1987, 413, 368–373. [Google Scholar]

- Dreier, J.P.; Heinemann, U. Regional and time dependent variations of low Mg2+ induced epileptiform activity in rat temporal cortex slices. Exp. Brain Res 1991, 87, 581–96. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, W.W.; Lewis, D.V.; Swartzwelder, H.S.; Wilson, W.A. Magnesium-free medium activates seizure-like events in the rat hippocampal slice. Brain Res 1986, 398, 215–219. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, R.S. Ictal epileptiform events induced by removal of extracellular magnesium in slices of entorhinal cortex are blocked by baclofen. Exp. Neurol 1989, 104, 155–161. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C.L.; Dreier, J.P.; Heinemann, U. Paroxysmal epileptiform discharges in temporal lobe slices after prolonged exposure to low magnesium are resistant to clinically used anticonvulsants. Epilepsy Res 1995, 20, 105–111. [Google Scholar]

- Behr, J.; Gloveli, T.; Gutierrez, R.; Heinemann, U. Spread of low Mg2+ induced epileptiform activity from the rat entorhinal cortex to the hippocampus after kindling studied in vitro. Neurosci. Lett 1996, 216, 41–44. [Google Scholar]

- Chesnut, T.J.; Swann, J.W. Epileptiform activity induced by 4-aminopyridine in immature hippocampus. Epilepsy Res 1988, 2, 187–195. [Google Scholar]

- Perreault, P.; Avoli, M. Effects of low concentrations of 4-aminopyridine on CA1 pyramidal cells of the hippocampus. J. Neurophysiol 1989, 61, 953–970. [Google Scholar]

- Ferland, R.J.; Applegate, C.D. Decreased brainstem seizure thresholds and facilitated seizure propagation in mice exposed to repeated flurothyl-induced generalized forebrain seizures. Epilepsy Res 1998, 30, 49–62. [Google Scholar]

- Bausch, S.B.; McNamara, J.O. Synaptic connections from multiple subfields contribute to granule cell hyperexcitability in hippocampal slice cultures. J. Neurophysiol 2000, 84, 2918–2932. [Google Scholar]

- Berdichevsky, Y.; Sabolek, H.; Levine, J.B.; Staley, K.J.; Yarmush, M.L. Microfluidics and multielectrode array-compatible organotypic slice culture method. J. Neurosci. Methods 2009, 178, 59–64. [Google Scholar]

- Dyhrfjeld-Johnsen, J.; Berdichevsky, Y.; Swiercz, W.; Sabolek, H.; Staley, K.J. Interictal spikes precede ictal discharges in an organotypic hippocampal slice culture model of epileptogenesis. J. Clin. Neurophysiol 2010, 27, 418–424. [Google Scholar]

- Järvelä, J.T.; Ruohonen, S.; Kukko-Lukjanov, T.K.; Plysjuk, A.; Lopez-Picon, F.R.; Holopainen, I.E. Kainic acid-induced neurodegeneration and activation of inflammatory processes in organotypic hippocampal slice cultures: Treatment with cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor does not prevent neuronal death. Neuropharmacology 2011, 60, 1116–1125. [Google Scholar]

- Tong, G.; Endersfelder, S.; Rosenthal, L.M.; Wollersheim, S.; Sauer, I.M.; Bührer, C.; Berger, F.; Schmitt, K.R. Effects of moderate and deep hypothermia on RNA-binding proteins RBM3 and CIRP expressions in murine hippocampal brain slices. Brain Res 2013, 1504, 74–84. [Google Scholar]

- Walton, N.Y.; Treiman, D.M. Response of status epilepticus induced by lithium and pilocarpine to treatment with diazepam. Exp. Neurol 1988, 101, 267–275. [Google Scholar]

- Wasterlain, C.G.; Chen, J.W. Mechanistic and pharmacologic aspects of status epilepticus and its treatment with new antiepileptic drugs. Epilepsia 2008, 49, 63–73. [Google Scholar]

- Mazarati, A.M.; Baldwin, R.A.; Sankar, R.; Wasterlain, C.G. Time-dependent decrease in the effectiveness of antiepileptic drugs during the course of self-sustaining status epilepticus. Brain Res 1998, 814, 179–185. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, L.Z.; Abbott, L.C.; Winzer-Serhan, U.H. Effects of chronic neonatal nicotine exposure on nicotinic acetylcholine receptor binding, cell death and morphology in hippocampus and cerebellum. Neuroscience 2007, 146, 1854–1868. [Google Scholar]

- Schmued, L.C.; Albertson, C.; Slikker, W. Fluoro-Jade: A novel fluorochrome for the sensitive and reliable histochemical localization of neuronal degeneration. Brain Res 1997, 751, 37–46. [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins, K.J.; Wang, G.; Schmued, L.C. Temporal progression of kainic acid induced neuronal and myelin degeneration in the rat forebrain. Brain Res 2000, 864, 69–80. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, L.H.; Rensing, N.R.; Wong, M. The mammalian target of rapamycin signaling pathway mediates epileptogenesis in a model of temporal lobe epilepsy. J. Neurosci 2009, 29, 6964–6972. [Google Scholar]

- Kuruba, R.; Hattiangady, B.; Shetty, A.K. Hippocampal neurogenesis and neural stem cells in temporal lobe epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav 2009, 14, 65–73. [Google Scholar]

- Wojtowicz, J.M.; Kee, N. BrdU assay for neurogenesis in rodents. Nat. Protoc 2006, 1, 1399–1405. [Google Scholar]

- Parihar, V.K.; Hattiangady, B.; Kuruba, R.; Shuai, B.; Shetty, A.K. Predictable chronic mild stress improves mood, hippocampal neurogenesis and memory. Mol. Psychiatry 2009, 16, 171–183. [Google Scholar]

- Kuruba, R.; Shetty, A.K. Could hippocampal neurogenesis be a future drug target for treating temporal lobe epilepsy? CNS Neurol. Disord. Drug Targets 2007, 6, 342–357. [Google Scholar]

- Sloviter, R.S. A simplified Timm stain procedure compatible with formaldehyde fixation and routine paraffin embedding of rat brain. Brain Res. Bull 1982, 8, 771–774. [Google Scholar]

- Minami, M.; Kuraishi, Y.; Satoh, M. Effects of kainic acid on messenger RNA levels of IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α and LIF in the rat brain. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun 1991, 176, 593–598. [Google Scholar]

- De Simoni, M.G.; Perego, C.; Ravizza, T.; Moneta, D.; Conti, M.; Marchesi, F.; de Luigi, A.; Garattini, S.; Vezzani, A. Inflammatory cytokines and related genes are induced in the rat hippocampus by limbic status epilepticus. Eur. J. Neurosci 2000, 12, 2623–2633. [Google Scholar]

- Vezzani, A.; Granata, T. Brain inflammation in epilepsy: Experimental and clinical evidence. Epilepsia 2005, 46, 1724–1743. [Google Scholar]

- Turrin, N.P.; Rivest, S. Innate immune reaction in response to seizures: Implications for the neuropathology associated with epilepsy. Neurobiol. Dis 2004, 16, 321–334. [Google Scholar]

- Voutsinos-Porche, B.; Koning, E.; Kaplan, H.; Ferrandon, A.; Guenounou, M.; Nehlig, A.; Motte, J. Temporal patterns of the cerebral inflammatory response in the rat lithium-pilocarpine model of temporal lobe epilepsy. Neurobiol. Dis 2004, 17, 385–402. [Google Scholar]

- Librizzi, L.; Noè, F.; Vezzani, A.; de Curtis, M.; Ravizza, T. Seizure-induced brain-borne inflammation sustains seizure recurrence and blood-brain barrier damage. Ann Neurol 2012, 72, 82–90. [Google Scholar]

- He, J.; Evans, C.O.; Hoffman, S.W.; Oyesiku, N.M.; Stein, D.G. Progesterone and allopregnanolone reduce inflammatory cytokines after traumatic brain injury. Exp. Neurol. 2004, 189, 404–412. [Google Scholar]

- VanLandingham, J.W.; Cekic, M.; Cutler, S.; Hoffman, S.W.; Stein, D.G. Neurosteroids reduce inflammation after TBI through CD55 induction. Neurosci. Lett 2007, 425, 94–98. [Google Scholar]

- White, S.H. Epilepsy and Disease Modification: Animal Models for Novel Drug Discovery. In Epilepsy: Mechanisms, Models, and Translatioal Perspectives; Rho, J.M., Sankar, R., Stafstrom,, C.E., Eds.; CRS Press: New York, 2010; pp. 143–153. [Google Scholar]

- Hellier, J.L.; Patrylo, J.R.; Dou, P.; Nett, M.; Rose, G.M.; Dudek, F.E. Assessment of inhibition and epileptiform activity in the septal dentate gyrus of freely behaving rats during the first week after kainate treatment. J. Neurosci 1999, 19, 100053–100064. [Google Scholar]

- Turski, W.A.; Cavalheiro, E.A.; Coimbra, C.; da Penha Berzaghi, M.; Ikonomidou-Turski, C.; Turski, L. Only certain antiepileptic drugs prevent seizures induced by pilocarpine. Brain Res 1987, 434, 281–305. [Google Scholar]

- Kadriu, B.; Guidotti, A.; Costa, E.; Davis, J.M.; Auta, J. Acute imidazenil treatment after the onset of DFP-induced seizure is more effective and longer lasting than midazolam at preventing seizure activity and brain neuropathology. Toxicol. Sci 2011, 120, 136–145. [Google Scholar]

| Mechanism | Drug |

|---|---|

| Blockage of voltage-gated sodium channels | Phenytoin |

| Fosphenytoin | |

| Carbamazepine | |

| Valproate | |

| Lamotrigine | |

| Oxcarbazepine | |

| Enhancement of GABA inhibition | Phenobarbital |

| Primidone | |

| Diazepam | |

| Lorazepam | |

| Clonazepam | |

| Tiagabine | |

| Valproate | |

| Blockage of low-threshold (T-type) Ca2+ channels | Ethosuximide |

| Gabapentin | |

| Valproate | |

| Reduction of glutamate excitation | Felbamate |

| Gabapentin | |

| Parampanel | |

| Classification | Model | References |

|---|---|---|

| Electrical models | Perforant pathway stimulation | [28,41–43] |

| Self-sustaining stimulation | [44–46] | |

| Chemical models | Kainic acid | [25,31,47–52] |

| Pilocarpine | [26,53–58] | |

| Lithium-pilocarpine | [26,59,60] | |

| Organophosphates | [37,61–63] | |

| Flurothyl | [64–67] | |

| Cobalt-homocysteine thiolactone | [68] | |

| Thermal models | Hyperthermia or febrile seizures | [69–74] |

| In vitro models | Low magnesium in brain slices | [75–77] |

| High potassium in brain slices | [78–80] | |

| 4-Aminopyridine in brain slices | [81–84] | |

| Organotypic slice cultures | [85–89] | |

| Refractory models | Lithium-pilocarpine | [37,90,91] |

| Kainic acid | [25,31,92–94] | |

| DFP | [37,62,95,96] | |

| Feature | Kainic acid | Pilocarpine | DFP | PPS | Hyperthermia |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Technical feasibility | Simple | Simple | Complex | Tedious | Tedious |

| Mortality rate | High | High | Medium | Low | Low |

| Acute neuronal injury | Severe | Severe | Severe | Moderate | Minimal |

| Diazepam response (early: <10-min) | Sensitive | Sensitive | Sensitive | Sensitive | Sensitive |

| Diazepam response (late: >40-min) | Insensitive | Insensitive | Insensitive | Sensitive | Sensitive |

| Neuroinflammation | Robust | Robust | Robust | Moderate | Moderate |

| Chronic hyperexcitability | Severe | Severe | Severe | Severe | Moderate |

| Neurodegeneration (>2 months post SE) | Severe | Severe | Severe | Moderate | Minimal |

| Spontaneous seizures (>2 months post SE) | Severe | Severe | Severe | Moderate | Minimal |

| Mossy fiber sprouting (>2 months post SE) | Severe | Severe | Severe | Moderate | Moderate |

© 2013 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Reddy, D.S.; Kuruba, R. Experimental Models of Status Epilepticus and Neuronal Injury for Evaluation of Therapeutic Interventions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013, 14, 18284-18318. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms140918284

Reddy DS, Kuruba R. Experimental Models of Status Epilepticus and Neuronal Injury for Evaluation of Therapeutic Interventions. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2013; 14(9):18284-18318. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms140918284

Chicago/Turabian StyleReddy, Doodipala Samba, and Ramkumar Kuruba. 2013. "Experimental Models of Status Epilepticus and Neuronal Injury for Evaluation of Therapeutic Interventions" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 14, no. 9: 18284-18318. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms140918284

APA StyleReddy, D. S., & Kuruba, R. (2013). Experimental Models of Status Epilepticus and Neuronal Injury for Evaluation of Therapeutic Interventions. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 14(9), 18284-18318. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms140918284