Optimization of Lipase-Mediated Synthesis of 1-Nonene Oxide Using Phenylacetic Acid and Hydrogen Peroxide

Abstract

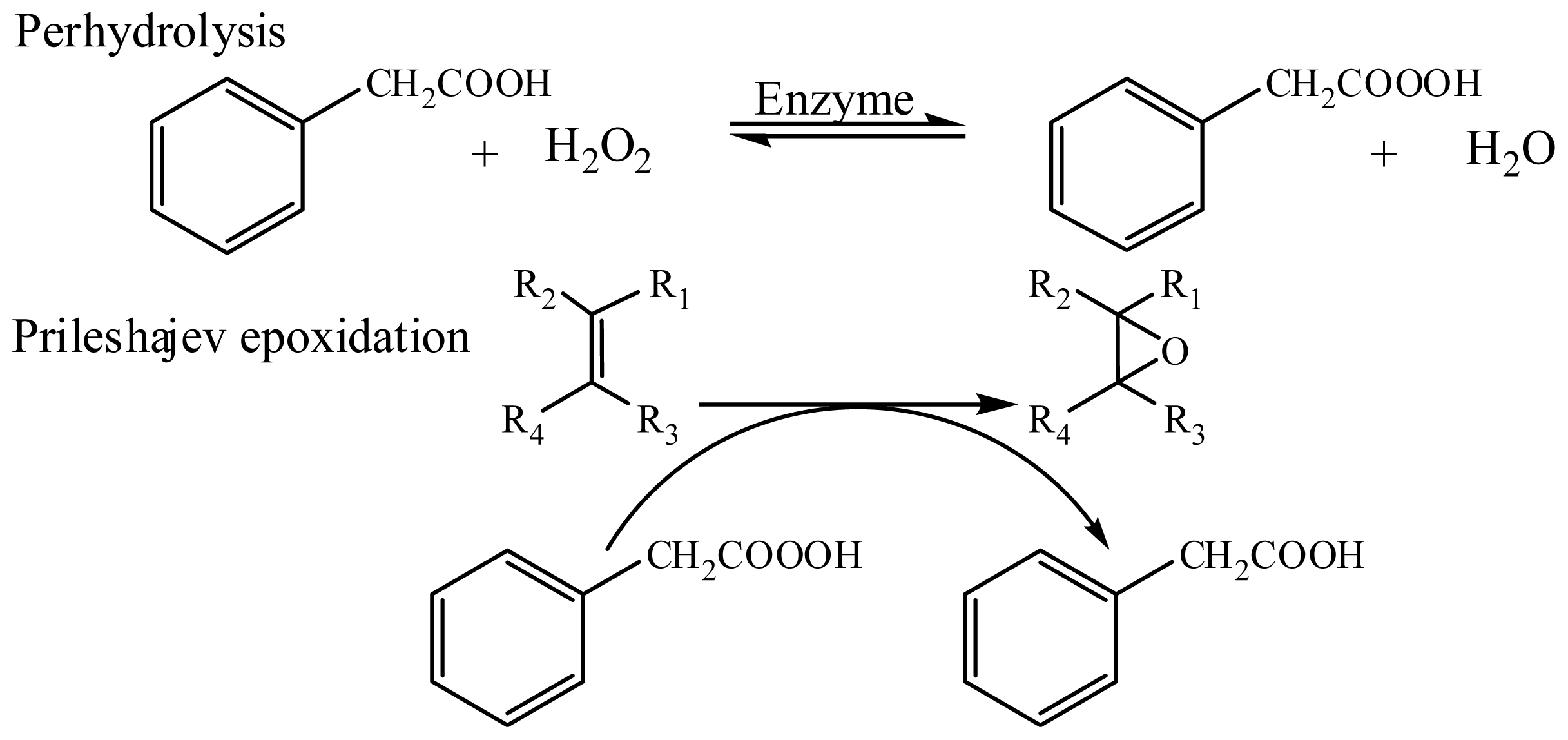

:1. Introduction

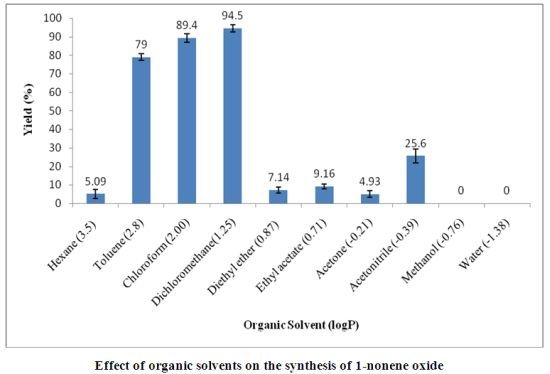

2. Results and Discussion

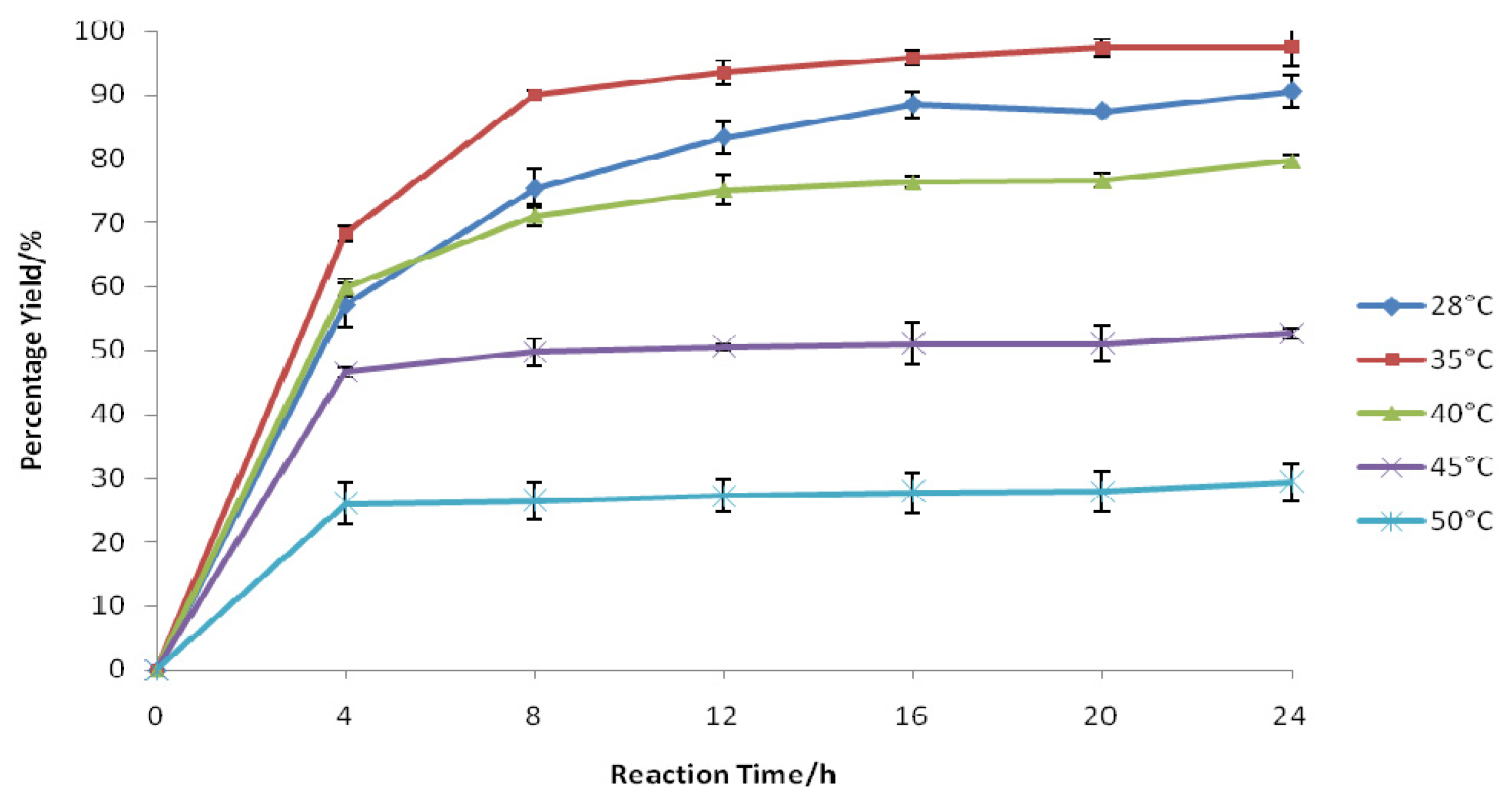

2.1. Influence of Temperature

2.2. Effect of H2O2

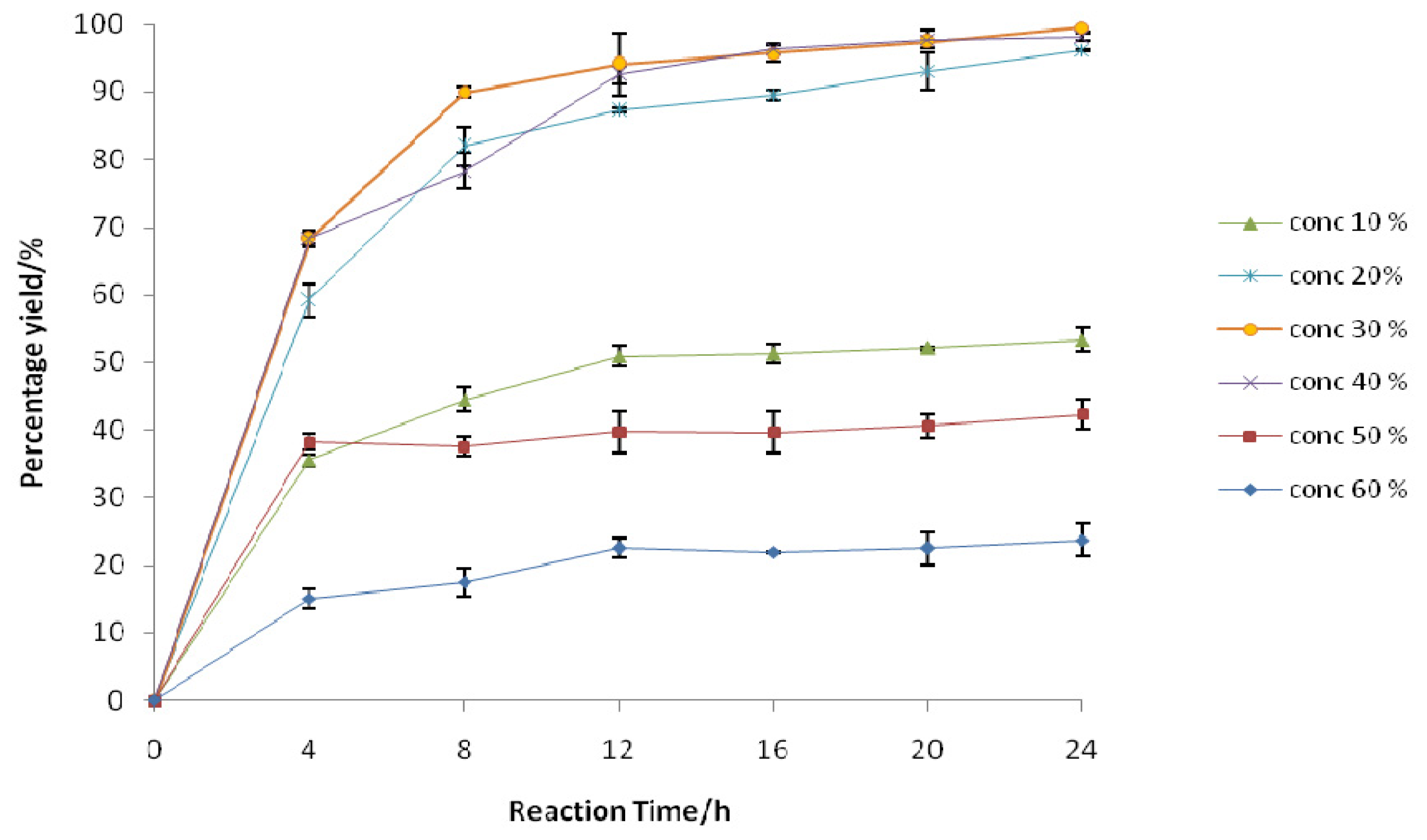

2.2.1. Effect of Initial H2O2 Concentration

2.2.2. Effect of H2O2 Amount

2.2.3. Effect of the Rate of H2O2 Addition

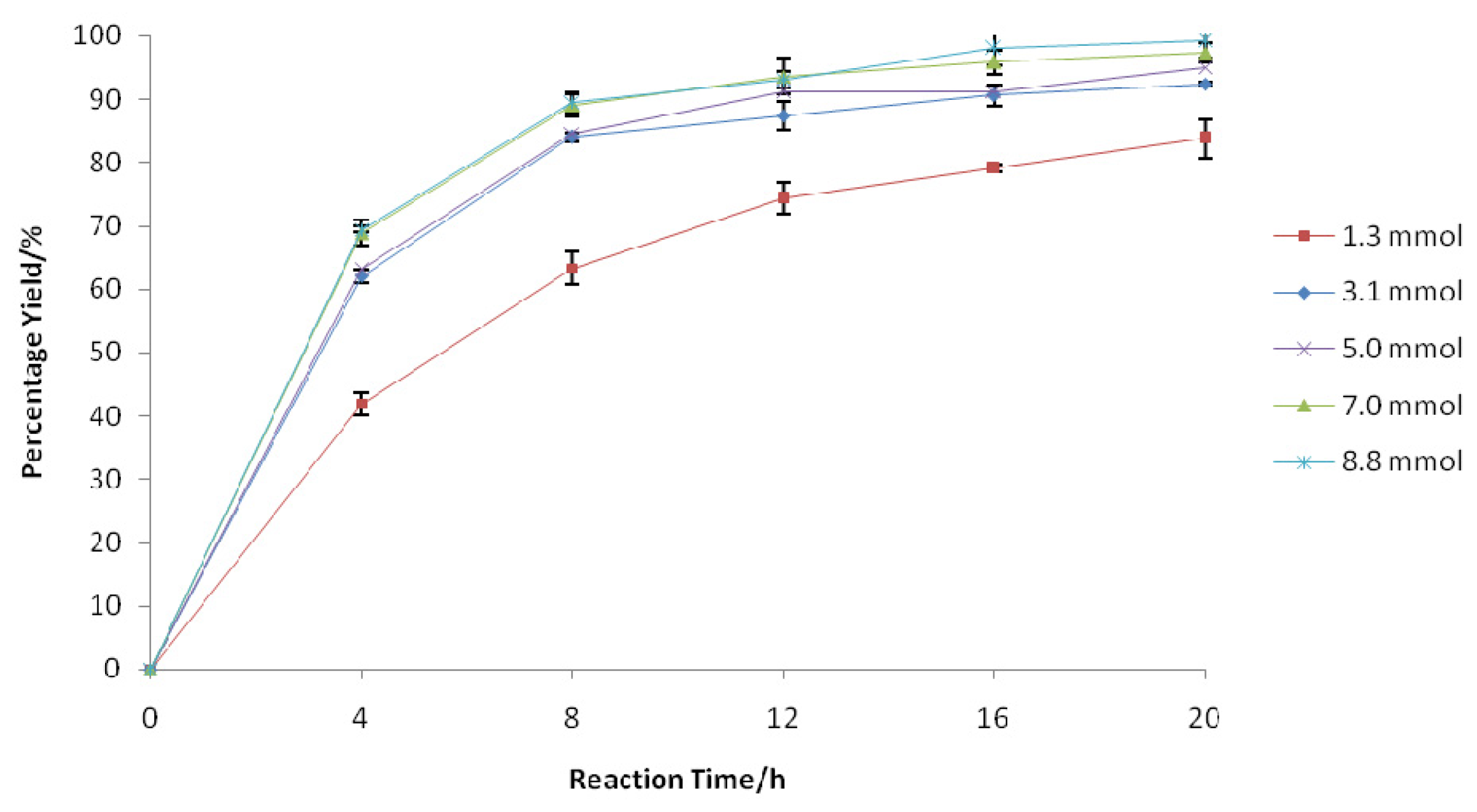

2.3. Effect of Phenylacetic Acid Amount

2.4. Effect of Stirring Rate

3. Experimental Section

3.1. Materials

3.2. Methods

3.2.1. General Synthetic Procedure for Chemoenzymatic Epoxidation

3.2.2. Analytical Procedure

3.2.3. Characterization

3.2.4. Spectral Data

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

References

- Kim-Piu, H.; Wing-Leung, W.; Kim-Ming, L.; Cheuk-Piu, L.; Tak, H.C.; Kwok-Yin, W. A simple and effective catalytic system of aliphatic terminal alkenes with manganese (II) as the catalyst. Chem. Eur. J 2008, 14, 7988–7996. [Google Scholar]

- Dinda, S.; Patwardhan, A.V.; Goud, V.V.; Pradhan, N.C. Epoxidation of cottonseed oil by aqueous hydrogen peroxide catalysed by liquid inorganic acids. Bioresour. Technol 2007, 99, 3737–3744. [Google Scholar]

- Peter, M.K.; Thomas, L.K.; Christopher, G.L.; Ann, W.K.; Robert, S.L.; Griffth, A.D. Aminoalcohol lipidoids and uses thereof. USA Application Number 12/716,732, 14 May 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Srihar, P.; Kumaraswamy, B.; Shankar, P.; Ravishashidhar, V.; Yadav, J.S. Stereoselective total synthesis of achaetolide and reconfirmation of its absolute configuration. Tetrahedron Lett 2010, 51, 6174–6176. [Google Scholar]

- Frost, C.G.; Penrose, S.D.; Gleave, R. Rhodium catalyst conjugate addition of a chiral alkenyltrifluoroborate salt: the enantionselective synthesis of hermitamides A and B. Org. Biomol. Chem 2008, 6, 4340–4347. [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira, E.O.; Graf, K.M.; Patel, M.K.; Baheti, A.; Hye-Sik, K.; MacArthur, L.H.; Dakshanamurthy, S.; Kan, W.; Brown, M.L.; Paige, M. Synthesis and evaluation of hermitamides A and B as human voltage-gated sodium channel blockers. Bioorg. Med. Chem 2011, 19, 4322–4329. [Google Scholar]

- Chandrasekhar, S.; Balaji, S.V.; Rajesh, G. First total synthesis of achaetolide. Tetrahedron Lett 2010, 51, 5164–5166. [Google Scholar]

- Xipu, H.; Xia, D.; Sengsheng, W.; Jun, X.; Yuxiang, G.U. Catalytic epoxidation of soybean oil methyl esters. Adv. Mater. Res 2012, 396–398, 833–836. [Google Scholar]

- Shangde, S.; Guolong, Y.; Yanlan, B.; Hui, L. Enzymatic epoxidation of corn oil by perstearic acid. J. Am. Oil. Chem. Soc 2011, 88, 1567–1571. [Google Scholar]

- Bjorkling, F.; Godtfredsen, S.E.; Kirk, O. Lipase-mediated formation of peroxycarboxylic acid used in catalytic epoxidation of alkenes. J. Chem. Soc 1990, 19, 1301–1303. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, W.S.D.; Lapis, A.A.M.; Suarez, P.A.Z.; Neto, B.A.D. Enzyme-mediated epoxidation of methyl oleate supported by imidazolium-based ionic liquids. J. Mol. Catal. B 2011, 68, 98–103. [Google Scholar]

- Sepulveda, J.; Teixeira, S.; Schuchardt, U. Alumina-catalyzed epoxidation of unsaturated fatty ester with hydrogen peroxide. Appl. Catal. A 2007, 218, 213–217. [Google Scholar]

- Klaas, M.R.; Warwel, S. Chemoenzymatic epoxidation of alkene by dimethyl carbonate and hydrogen peroxide. Org. Lett 1999, 1, 1025–1026. [Google Scholar]

- Orellana-Coca, C.; Billakanti, J.M.; Mattiasson, B.; Hatti-Kaul, R. Lipase mediated simultaneous esterification of oleic acid for the production of alkylepoxystearates. J. Mol. Catal. B 2007, 44, 133–137. [Google Scholar]

- Yi, X.; Na, R.B.J.K.; Zhi, L. Efficient epoxidation of alkene with hydrogen peroxide, lactone and lipase. Green Chem 2009, 11, 2047–2051. [Google Scholar]

- Abdulmalek, E.; Arumugam, M.; Rahman, M.B.A.; Basri, M.; Salleh, A.B. Enzyme-facilitated synthesis of 1-nonene oxide and simple GC-MS SIM method for rapid screening of epoxidation processes. Biocatal. Biotransform 2012, in press. [Google Scholar]

- Yankah, V.V.; Akoh, C.C. Lipase-catalysed acidolysis of tristearin with oleic acid or caprylic acids to produce structured lipids. J. Am. Oil. Chem. Soc 2000, 77, 495–500. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman, M.B.A.; Chaibakhsh, N.; Basri, M.; Salleh, A.B.; Rahman, R.N.Z.A. Application of artificial neural network for yield prediction of lipase-catalysed synthesis of dioctyl adipate. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol 2009, 158, 722–735. [Google Scholar]

- Adnani, A.; Basri, M.; Chaibakhsh, N.; Salleh, A.B.; Rahman, M.B.A. Lipase-catalyzed synthesis of a sugar alcohol-based non-ionic surfactant. Asian J. Chem 2011, 23, 388–392. [Google Scholar]

- Radzi, S.M. Enzymatic synthesis of oleyl oleate, a liquid wax ester, in stirred batch reactor. Ph.D. Thesis, Universiti Putra Malaysia, Serdang, Malaysia, 21 June 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Orellana-Coca, C.; Camocho, S.; Adlercreutz, D.; Mattiasson, B.; Hatti-Kaul, R. Chemo-enzymatic epoxidation of linoleic acid: Parameters influencing the reaction. Eur. J. Lipid. Sci. Technol 2005, 107, 864–870. [Google Scholar]

- Wiles, C.; Hammond, M.J.; Watts, P. The development and evaluation of a continuous flow process for the lipase-mediated oxidation of alkenes. Beilstein J. Org. Chem 2009, 5, 27. [Google Scholar]

- Tornvall, U.; Orellana-Coca, C.; Hatti-Kaul, R.; Adlercreutz, D. Stability of immobilized Candida antarctica lipase B during chemo-enzymatic epoxidation of fatty acid. Enzyme Microb. Tech 2007, 40, 447–451. [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez, K.; Garcia-Galen, C.; Fernandez-Lafuente, R. Simple and efficient immobilization of lipase B from Candida antarctica on porous styrene-divinylbenzene beads. Enzyme Microb. Tech 2011, 49, 72–78. [Google Scholar]

- Radzi, S.M.; Basri, M.; Salleh, A.B.; Ariff, A.; Rahman, M.B.A.; Rahman, R.N.Z.A. High performance enzymatic synthesis of oleyl oleate using immobilised lipase from Candida antarctica. Electron. J. Biotech 2005, 8, 291–298. [Google Scholar]

- Abdulmalek, E.; Saupi, H.S.M.; Tejo, B.A.; Basri, M.; Salleh, A.B.; Rahman, R.N.Z.R.A.; Rahman, M.B.A. Improved enzymatic galoctose ester synthesis in ionic liquids. J. Mol. Catal. B 2012, 76, 37–43. [Google Scholar]

© 2012 by the authors; licensee Molecular Diversity Preservation International, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open-access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Abdulmalek, E.; Arumugam, M.; Basri, M.; Rahman, M.B.A. Optimization of Lipase-Mediated Synthesis of 1-Nonene Oxide Using Phenylacetic Acid and Hydrogen Peroxide. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2012, 13, 13140-13149. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms131013140

Abdulmalek E, Arumugam M, Basri M, Rahman MBA. Optimization of Lipase-Mediated Synthesis of 1-Nonene Oxide Using Phenylacetic Acid and Hydrogen Peroxide. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2012; 13(10):13140-13149. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms131013140

Chicago/Turabian StyleAbdulmalek, Emilia, Mahashanon Arumugam, Mahiran Basri, and Mohd Basyaruddin Abdul Rahman. 2012. "Optimization of Lipase-Mediated Synthesis of 1-Nonene Oxide Using Phenylacetic Acid and Hydrogen Peroxide" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 13, no. 10: 13140-13149. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms131013140

APA StyleAbdulmalek, E., Arumugam, M., Basri, M., & Rahman, M. B. A. (2012). Optimization of Lipase-Mediated Synthesis of 1-Nonene Oxide Using Phenylacetic Acid and Hydrogen Peroxide. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 13(10), 13140-13149. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms131013140