1. Introduction

Pu-erh tea is produced in the Yunnan province of China. The key process of Pu-erh preparation includes the step of fermentation, in which microorganisms play a very important role in producing the taste, color, fragrances, as well as the functional components. This special preparation process makes Pu-erh tea unique in terms of its shelf life, as well as its bioactivities. As we know, green tea needs to be consumed as fresh as possible, mainly due to the instability of its anti-oxidant components. However, it is believed in Chinese tradition that the taste, as well as the function of Pu-erh tea gets better with increasing shelf time, mainly because the fermentation process is still ongoing during storage. This leads to a very interesting hypothesis, that the bioactivity components of Pu-erh tea are produced during the fermentation process.

Literature researching the chemical components and bioactivities of Pu-erh tea is very limited. It has been shown that the Trolox equivalent antioxidant capacity (TEAC) values of the water extracts of Pu-erh tea (WEPT) is similar to green tea, oolong tea, and black tea, indicating that WEPT had a significant antioxidant activity [

1]. However, due to the fermentation and preservation period, the concentration of total catechins in Pu-erh tea is one tenth of that in green tea suggesting the active substances contributing to the antioxidant activity of Pu-erh tea might be formed during fermentation [

1]. Another study also found that Pu-erh tea ethyl acetate extract fraction has almost no monomeric polyphenols, theaflavins, and gallic acid, but showed a much stronger antioxidant effect than typical green tea catechin (−)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate [

2]. A very recent study isolated a new amide,

N-(3,4-dihydroxybenzoyl)-3,4-dihydroxybenzamide from the Pu-erh tea and showed it prevented H

2O

2-induced cell death of human micro-vascular endothelial cell [

3]. However, it has also been shown by HPLC-DAD-MS coupled with 2,2′-azinobis (3-ethylbenzthiazolinesulfonic acid) diammonium salt (ABTS) assay that free radical scavengers in Pu-erh tea still attributed to gallic acid, (−)-gallocatechin, (−)-epigallocatechin, (+)-catechin, caffeine, (−)-epicatechin, (−)-epigallocatechingallate, rutin, (−)-epicatechingallate, quercetin-3-glucoside, and kaempferol-3-glucoside. They proposed that free radical scavenger activity in Pu-erh raw tea was stronger than the ripe one, and the activity decreased with the increase of preservation [

4]. A recent study also showed that the raw Pu-erh tea had significantly higher antioxidant activities than the ripened pu-erh teas in the 1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl, Trolox equivalent antioxidant capacity. The epigallocatechin-3-gallate, epigallocatechin, epicatechin-3-gallate, and quinic acid were decreased and gallic acid was increased in a year-dependent manner [

5].

In spite of the debates on its anti-oxidant activity, Pu-erh tea has been shown to have anti-obesity and anti-tumor activity. An earlier study showed that high molecular weight fractions of green tea, black tea, oolong tea, and Pu-erh tea induced apoptosis in human monoblastic leukemia U937 cells as well as in stomach cancer MKN-45 cells [

6]. It has also been shown that the gains in body weight, levels of triacylglycerol, and total cholesterol were suppressed in Pu-erh tea-treated rats, which correlated with the down-regulation of fatty acid synthase (FAS) expression in the livers of rats fed with tea leaves.

In vitro study revealed that FAS expression in hepatoma HepG2 cells was suppressed by the extracts of Pu-erh tea at both protein and mRNA levels, which might contribute to the cell growth inhibition [

7]. Further study showed the extract of Pu-erh raw tea with ethyl acetate (PR-3) contributed to the most effective hypolipidemic potential and decreased the expression of FAS and inhibited the activity of acetyl-coenzyme A carboxylase by stimulating AMP-activated protein kinase. Moreover, PR-3-5s blocked the progression of the cell cycle at the G1 phase by inducing p53 and p21 expression [

8]. Our previous study also showed that Pu-erh tea could cause cell cycle arrest of the human gastric cancer cell line SGC-7901, but not affecting normal CCC-HEL-1 cells [

9]. These studies suggested that Pu-erh tea has the potential of anti-tumor activity. However, the mechanism and the molecular targets of its bioactivity are still not clear. Due to the unique procedure during preparation, it is speculated that Pu-erh tea might be different with green tea in terms of its anti-tumor action. The understanding of its mechanism in tumor cell growth inhibition will greatly facilitate its use in cancer prevention.

In this study, we engineered several mouse tumor cell lines by introducing either p53 mutant (p53N236S, p53N239S in human) or/and Ras mutant (H-RasV12) into mouse embryo fibroblasts (MEFs) with

p53−/− genetic background. IARC TP53 database (version R14, November 2009) [

10] shows that human p53N239S (or p.N239S) has been reported as a somatic mutation in 32 tumor cases, tumor origin tissues including breast, colon, stomach, hematopoietic and reticuloendothelial systems, liver and intrahepatic bile ducts, bronchus and lung, and brain. The widespread tumor spectrum of p53N239S suggested its importance in tumorigenesis. These engineered cell lines are very clear in terms of their genetic background and the oncogenic proteins they expressed; thus providing us with useful tools in screening and finding the molecular targets of drugs. Because the mutation rates of p53 and Ras are most frequent in human tumors, these tumor cell lines were used to screen anti-tumor activity. Most importantly, we could use the wild type MEFs as a control to test toxicity of drugs.

By using these cell lines with a clear genetic background, we found that water extracts of Pu-erh tea could induce cellular apoptosis in tumor cells but not in control wild type cells. Further study revealed that water extracts of Pu-erh tea could reduce the oncogenic mutant p53 level and thus selectively eliminate the growth advantages of tumor cells.

3. Discussion

The toxicity of chemotherapeutic drugs has become one of the major issues in chemotherapy. The new developments in cancer fields have focused more and more on cancer prevention, early diagnosis and personalized medicine. Thus, chemicals which could target tumor specific molecules and selectively kill tumor cells become one of the most popular topics in drug screening.

In this study, using the wild type control and genetically engineered tumor cell lines as our screening system, we could easily differentiate the toxicity of drug treatment to normal cells from the tumor cell growth inhibition activity. Furthermore, the specific genetic background provided advantages in identifying the molecular target of the treatment.

Green tea has been reported extensively as anti-tumor reagents, which mainly attributes to its anti-oxidant components, such as EGCG,

etc., and multiple tumorigenic proteins were found to be regulated by EGCG at different concentrations. Among those, tumor promoting factors like DNA methyltransferase (DNMT), epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), hepatocyte growth factor receptor (HGFR), insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor (IGF1R), matrix metalloproteinase (MMP), vascular endothelial growth factor A (VEGFA) and BCL-2 are down-regulated by EGCG while tumor suppressor p53 is up-regulated [

11]. These mechanisms provided the basis for the selective inhibition of tumor growth by green tea while not affecting wild type cells.

Due to its special fermented processing and the incorporation of microbes, Pu-erh tea might be different from green tea in terms of its tumor cell growth inhibition activity, as well as its molecular targets. Also, the fermentation by microbes might increase the bioavailability of Pu-erh tea components. Nevertheless, as a regular drink in human life, we speculated that the toxicity of Pu-erh tea to normal cells should be very limited. It has been also reported that the safe dosage for Sprague-Dawley and Wistar rats could be 5000 mg/kg/day [

12,

13].

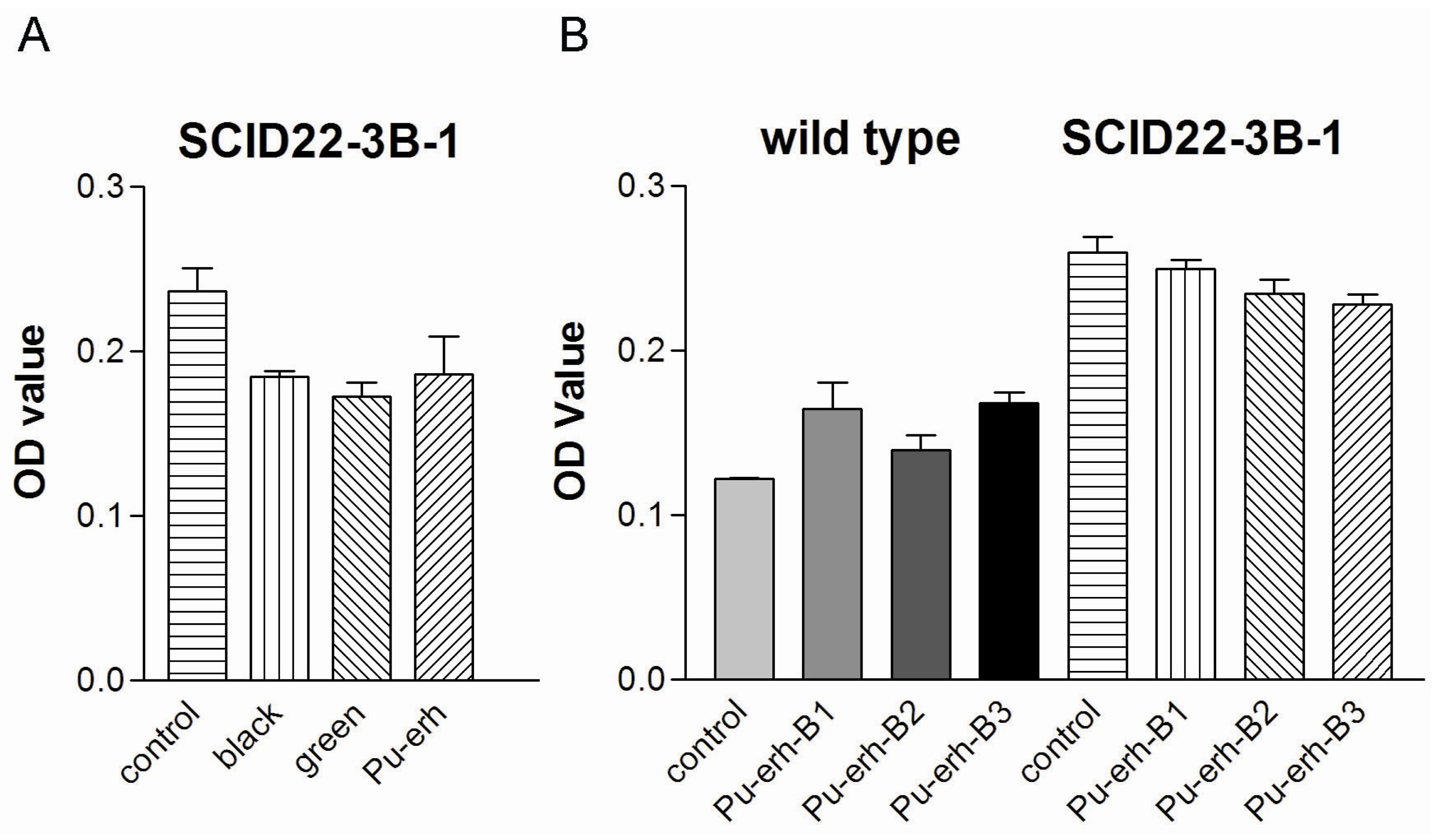

In this study, we showed that Pu-erh tea has comparable tumor cell growth inhibition activity with black tea and green tea. However, several independent groups have shown that the fermentation process of Pu-erh tea could reduce its total catechins and related anti-oxidant activity [

1,

4,

5]. It is reasonable to speculate that the tumor cell growth inhibition activity of Pu-erh tea is due to other natural compounds. Further studies are ongoing in finding the natural compound(s) responsible for its bioactivity.

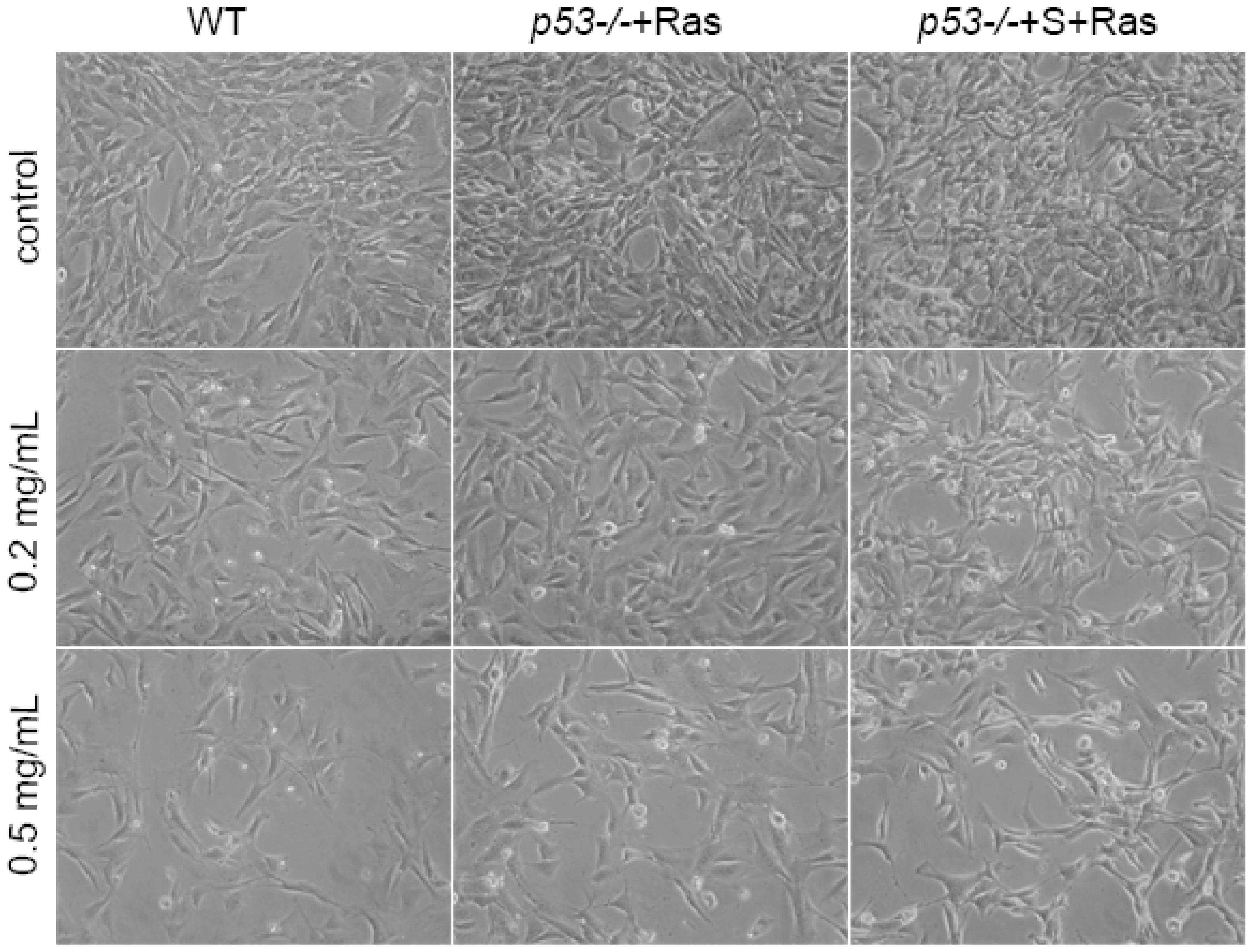

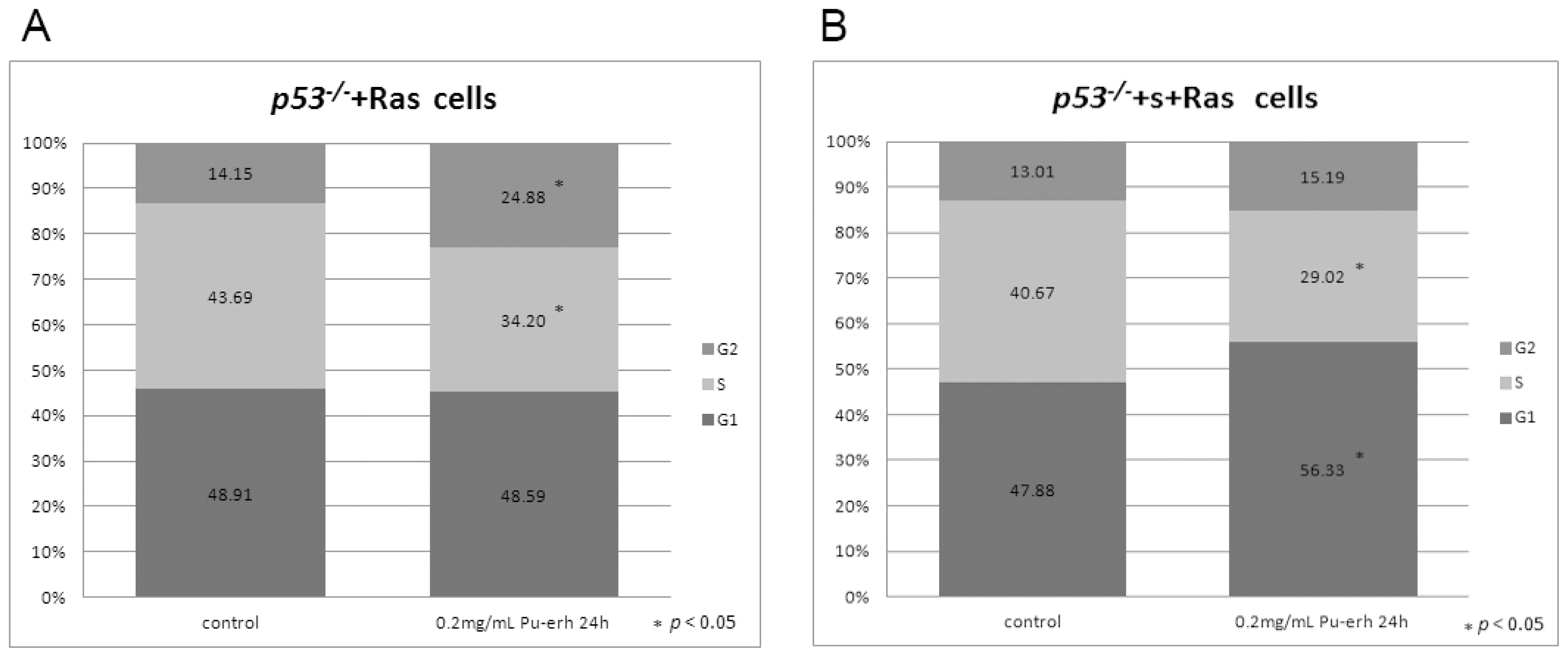

We also found that Pu-erh tea water extracts selectively inhibit tumor cell growth at a concentration that does not affect wild type cells. At this concentration, Pu-erh tea water extracts inhibited tumor cell growth by down-regulated S phase and caused G1 or G2 arrest. This selective inhibition of tumor cells would greatly reduce the non-specific cyto-toxicity and provide a way of cancer prevention or treatment that potentially helps to solve the current problem of cyto-toxicity of most conventional chemotherapy drugs.

Furthermore, our studies revealed that Pu-erh tea water extracts down-regulated the expression of p53 mutant at both mRNA and protein levels. The down-regulation of mutant p53 by Pu-erh tea might eliminate the growth advantage of tumor cells with mutant p53. As we know, more than 50% of human tumors have p53 mutation, and mutant p53 proteins could gain oncogenic function and impact tumor progression and metastasis [

14]. Thus, targeting mutant p53 has become one important strategy in drug screening and personalized cancer treatment [

15]. Because of its regulation on mutant p53, Pu-erh tea has a potential in cancer treatment with low side effects.

HSP70 and HSP90 proteins have been targeted for cancer therapy [

16,

17] due to their high expression level in tumor cells and their chaperon characteristics for other oncogenic proteins, e.g., mutant p53 [

18]. Here we also found that Pu-erh tea treatment could slightly down-regulate both HSP70 and HSP90 protein levels in tumor cells. However, the down-regulation of HSP70 and HSP90 by Pu-erh tea seemed to depend on genetic background since we did not observe obvious changes of HSP70 and HSP90 in cells with lower p53S or null p53 expression,

i.e.,

p53S/S cells,

p53S/S +Ras cells and

p53−/−+Ras cells.

On the other hand, our data showed that the same concentration of Pu-erh tea solution did not cause p53 stabilization or activation of its downstream pathways in the wild type cells. Growth curve analysis also did not show any growth inhibition of wild type cells by Pu-erh tea treatment. Altogether our data revealed the action of Pu-erh tea on tumor cells and provided a possible mechanism for Pu-erh tea’s selectivity in inhibiting tumor cells without affecting wild type cells.

4. Experimental Section

4.2. Cell Lines, Constructs and Antibodies

Wild type MEFs were harvested and prepared from individual day 13.5 wild type C57/B6 mouse embryos. Wild type MEFs were used for experiments before passage 10 and the cells were passed at the ratio of 1:2 or 1:3 so that the cells would not be diluted and senesced quickly.

Immortalized cell lines 395-3B-1 harboring a p53 point mutation (p53S) were established as described [

19]. 395-3B-1 cells immortalized from MEFs double knocked out telomerase and Werner (

mTR−/−Wrn−/−) were injected subcutaneously into SCID mouse. The tumors growing from the injected cells were harvested and the tumor cells were cultured to establish SCID22-3B-1 cell line. Sequencing of p53 cDNA from these tumor cells revealed a p53S mutation. Thus the genetic background of SCID22-3B-1 tumor cell line is

mTR−/−Wrn−/− p53S/S.

pBabe-H-RasV12 construct and either empty vector PQCXIH or PQCXIH-p53S construct (as described previously [

20]) were introduced into

p53−/− MEF. After 1–2 months antibiotics selection, cell colonies were picked up, expression of p53S or H-RasV12 was analyzed by both Western blot and immunostaining. By this way,

p53−/− MEFs stably introduced both p53S and H-RasV12 (

p53−/−+S+Ras MEFs), or H-RasV12 and empty PQCXIH vector (

p53−/−+Ras MEFs) were established. MEFs were cultured and injected into SCID mice to get

p53−/−+S+Ras and

p53−/−+Ras tumor cells.

p53S/S and p53S/+ MEFs were harvested and prepared from individual day 13.5 embryos from p53S/+ mice. pBabe-H-RasV12 construct were introduced into these cells to establish p53S/S+Ras or p53S/++Ras MEFs.

All cell lines were cultured in DMEM media supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Hyclone, CA, USA) in a 3% oxygen and 5% CO2 incubator at 37 °C.

Antibodies used for Western blot were anti-p16Ink4a (M-156) (1:500, Santa Cruz, CA, USA), anti-p21 (F-5) (1:500, Santa Cruz, CA, USA), anti-p53 Ab1(clone PAb240) (1:250, Neomarker, CA, USA), anti-phospho-p53 (Ser15) (1:500, Cell Signaling, MA, USA), anti-Hsp70 (1:1000, Stressgen, BC, Canada), anti-Hsp90 (1:1000, Stressgen, BC, Canada), anti-γ-tubulin (1:5000, Upstate, NY, USA).

4.3. Growth Curve Assay

2.5 × 104 cells were seeded per well in 12 well plates, triplicates were prepared for each sample. At each time point, cells were fixed for 20 min at room temperature in 10% buffered formalin, and stained with 1 mL 0.1% crystal violet for 20 min at room temperature. After washing and drying the plates, cells were treated with 2 mL 10% acetic acid and OD of the extracted dye was measured at 595 nm.

4.4. Real-Time RT-PCR

RNA was extracted from cells and cDNA was synthesized by reverse transcription. Real-time PCR was performed using SYBR-Green PCR master mix following the manufacturer’s instruction (Applied Biosystems, CA). The primers used are as following: p53 (Forward primer: 5′-TGATGGAGAGTATTTCACCC-3′, Reverse primer: 5′-GGGCATCCTTTAACTCTAAG-3′). β-actin (Forward primer: 5′-AGAGGGAAATCGTGCGTGAC-3′, Reverse primer: 5′-CAATAGTGATGACCTGGCCGT-3′).

4.5. Cell Cycle Analysis

Cell cycle analysis was done by flow cytometry (BD, FACS Vantage SE). Data were analyzed by Flowjo. Percentages of cells in G1, S, and G2 were determined using the Dean-Jett-Fox algorithm.