De Novo Generation-Based Design of Potential Computational Hits Targeting the GluN1-GluN2A Receptor

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

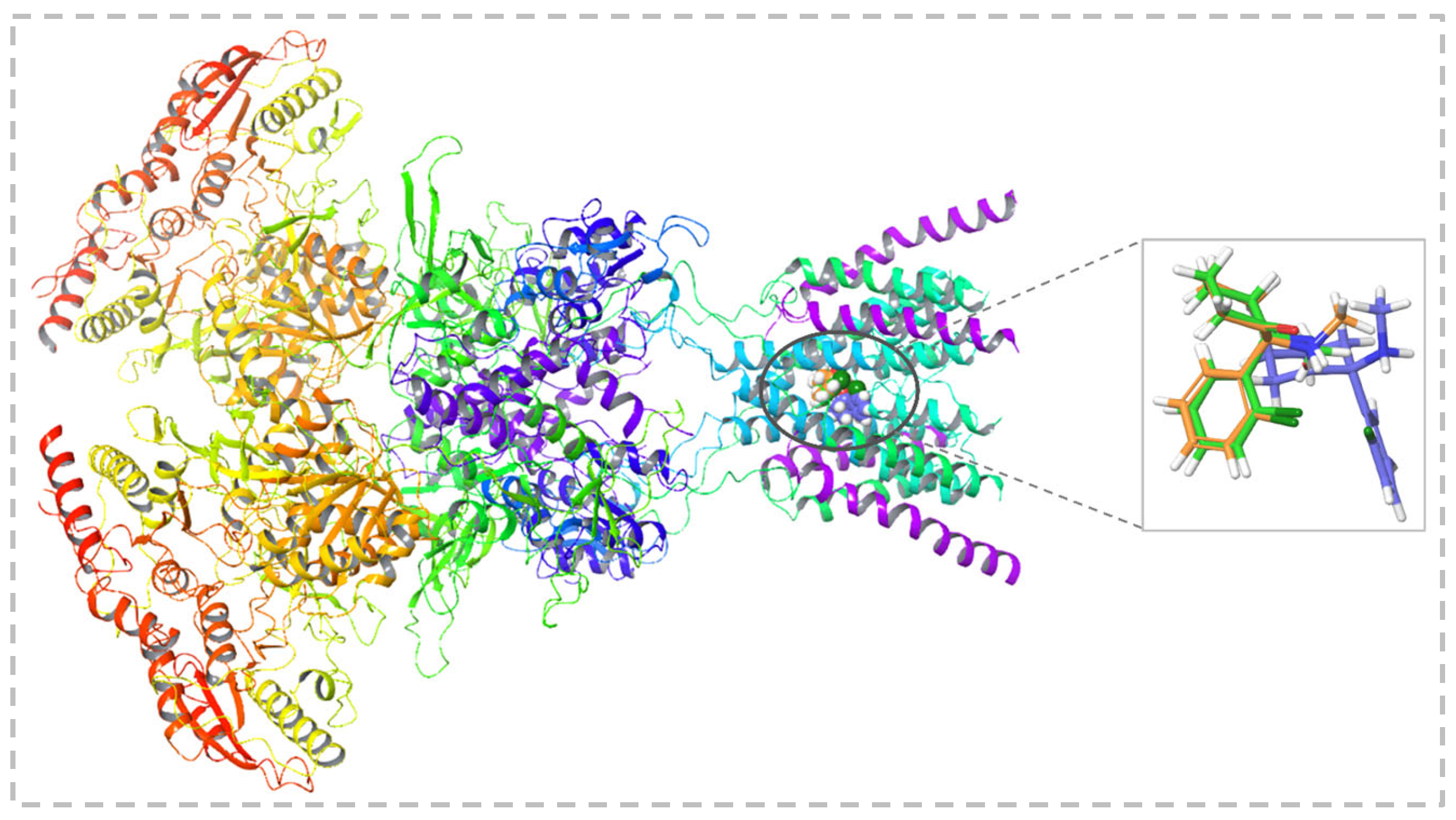

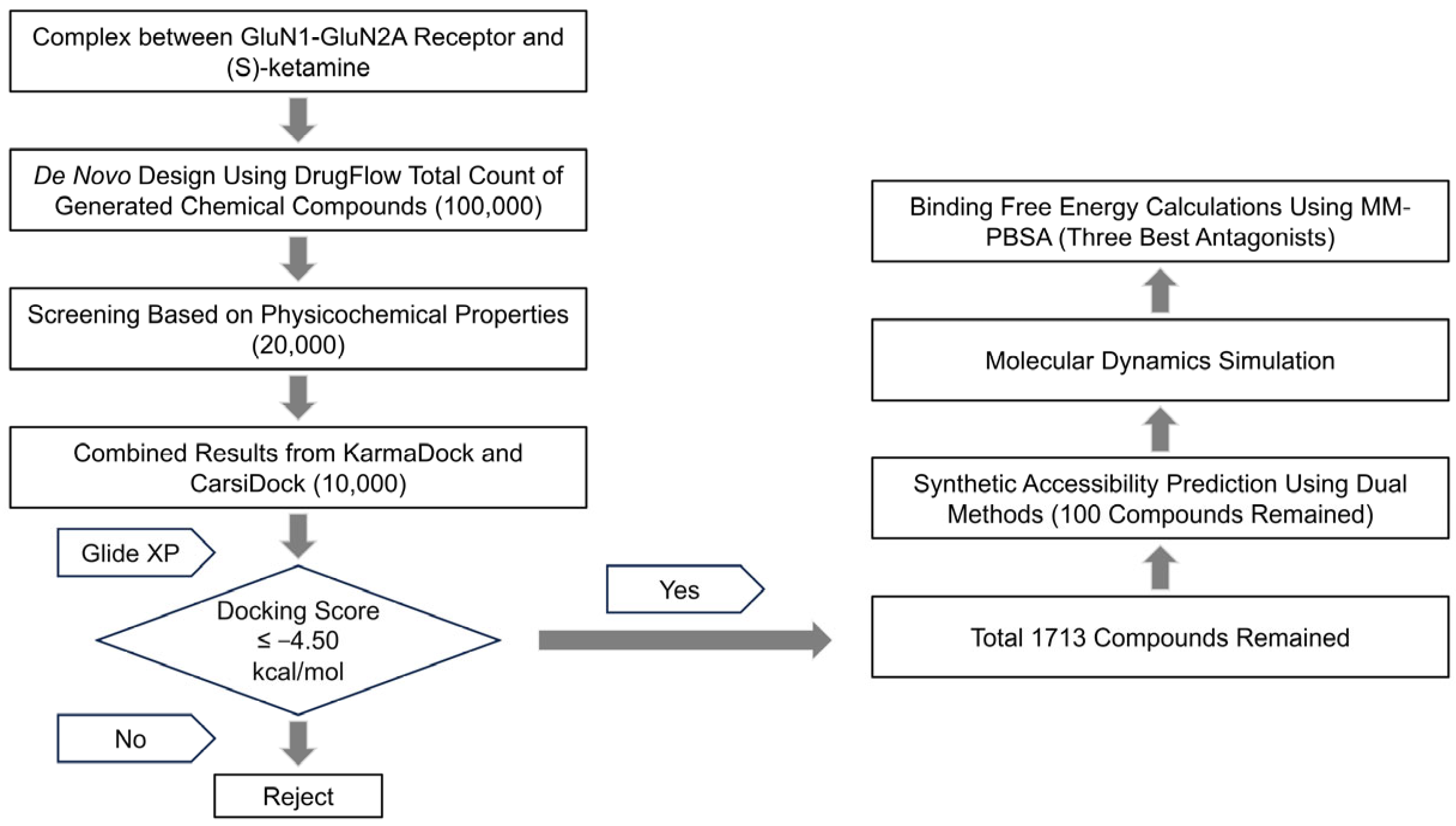

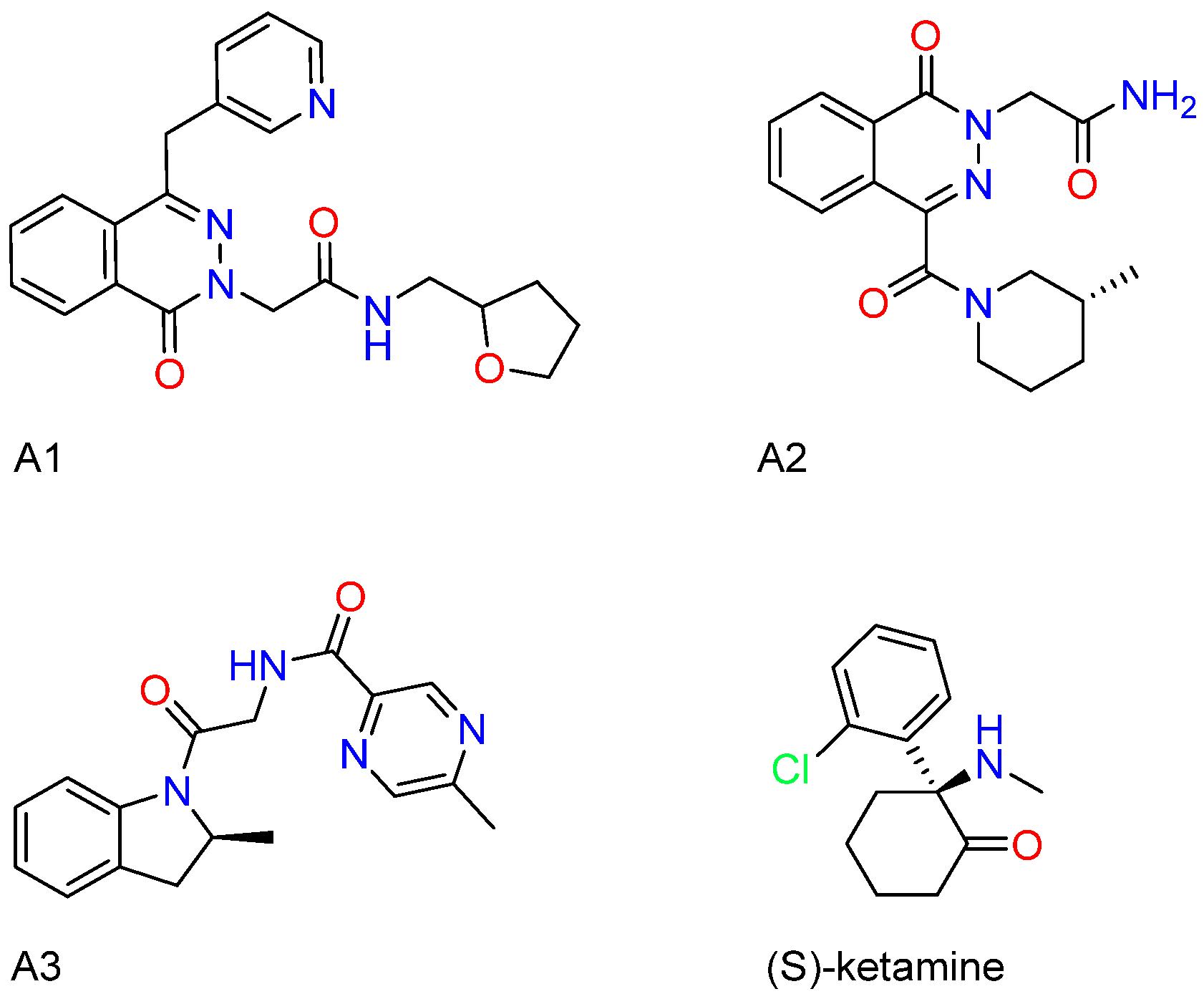

2.1. Results of Molecular Generation and Virtual Screening

2.2. ∆Gbinding Calculations Using the MM-PBSA Approach

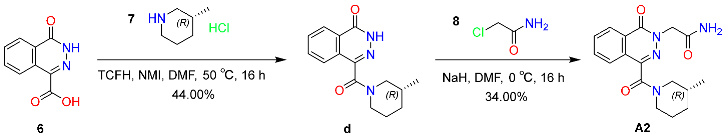

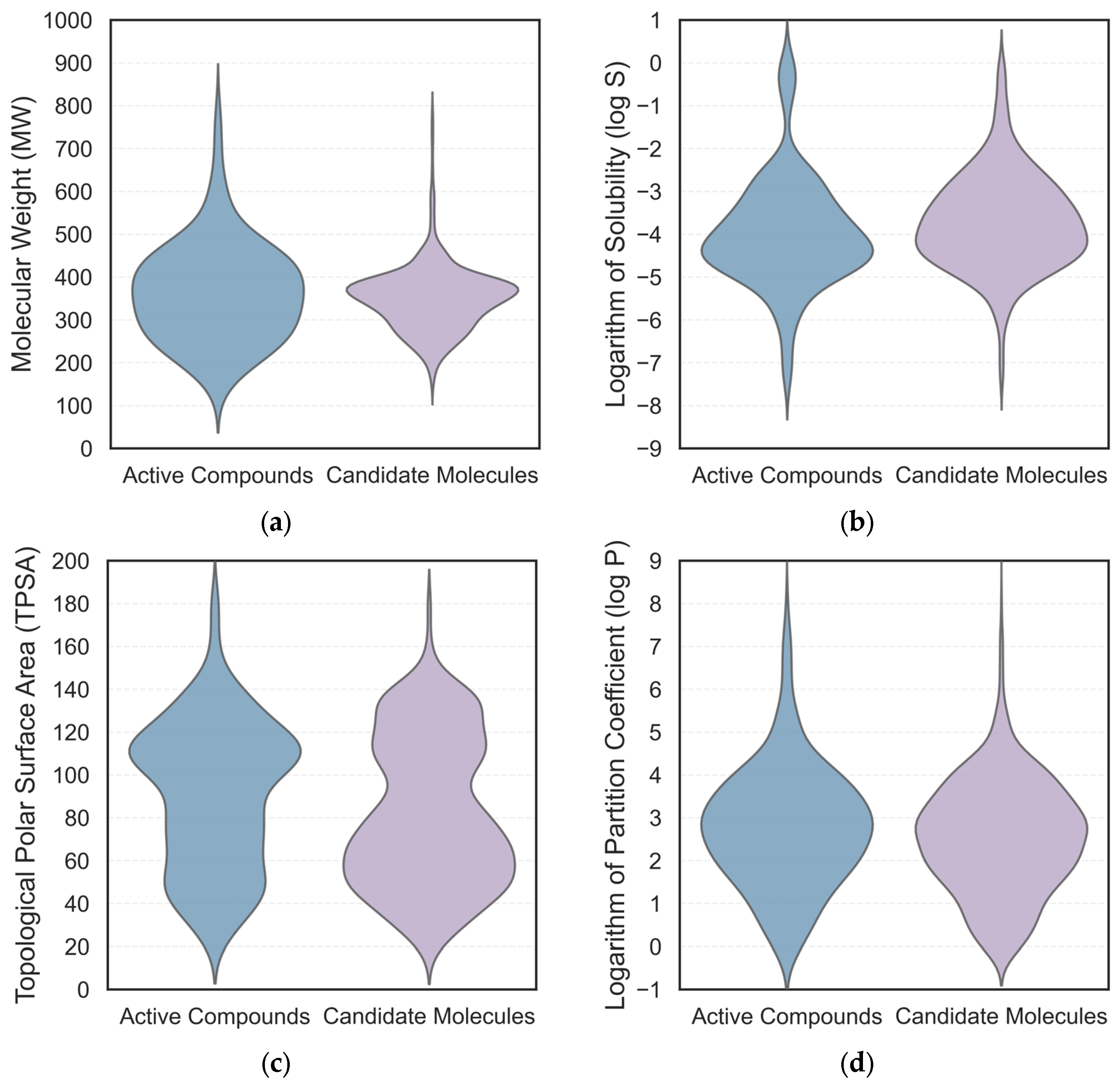

2.3. Pharmacokinetic and Drug-likeness Evaluation

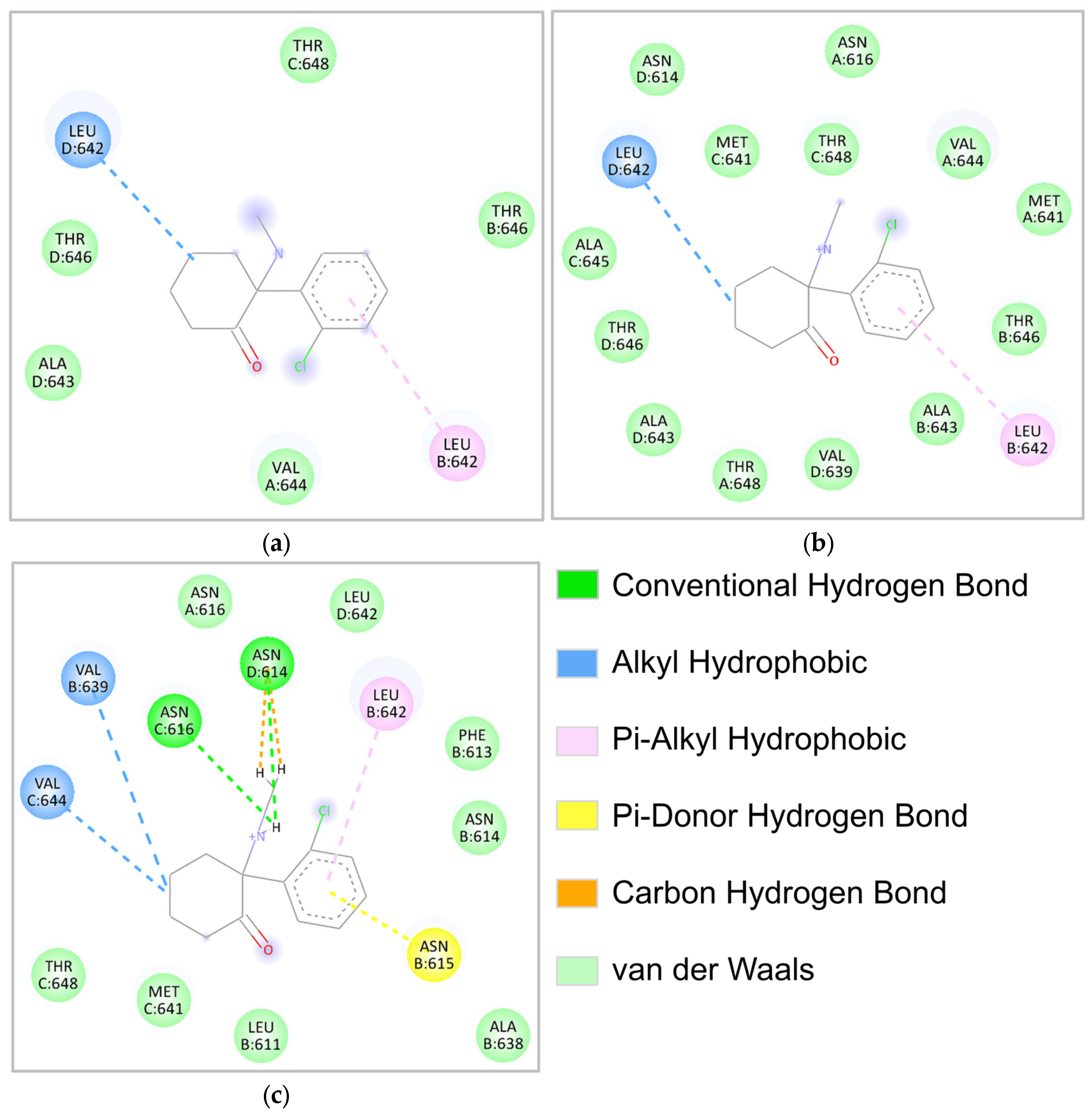

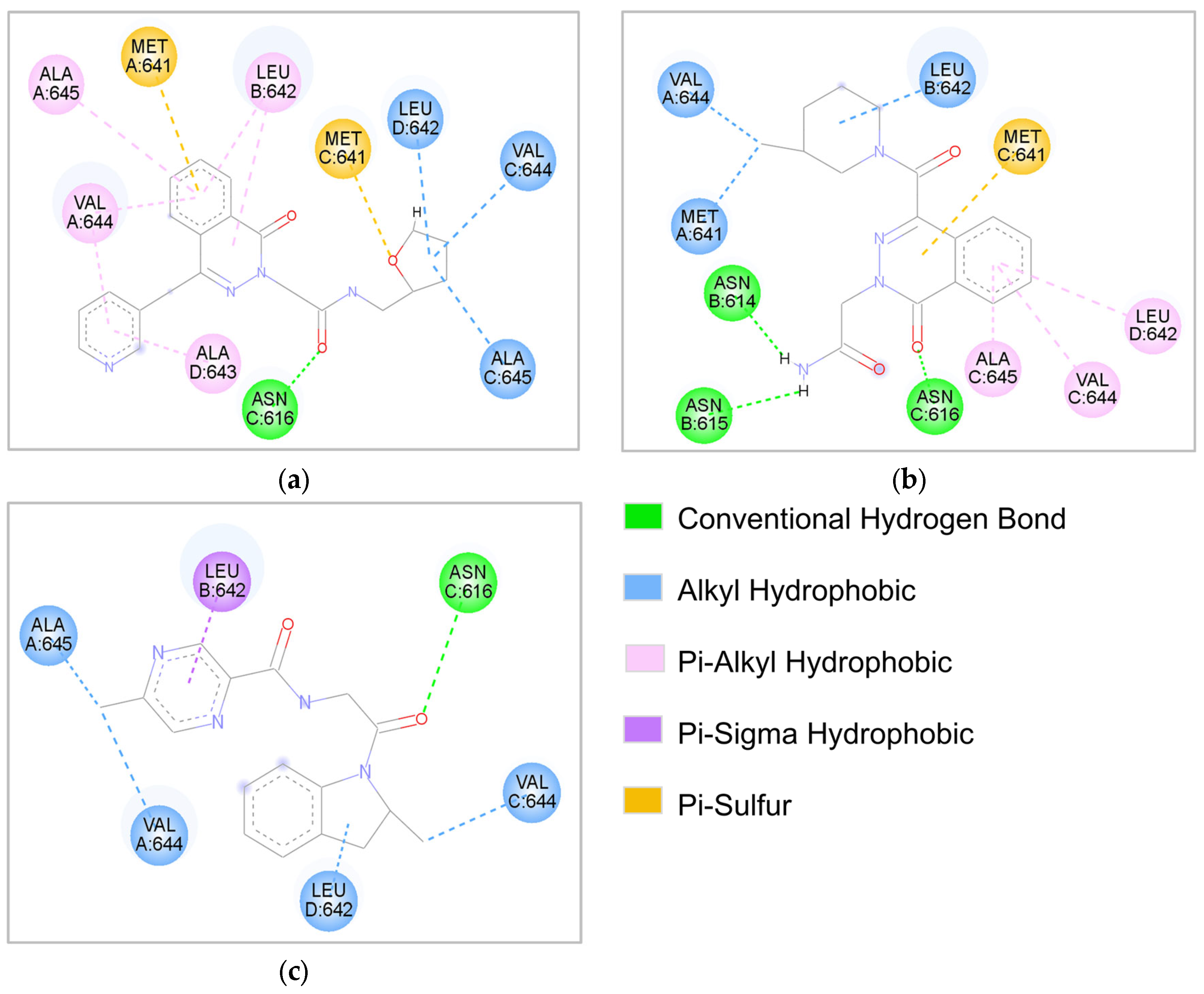

2.4. Molecular Interaction Analysis

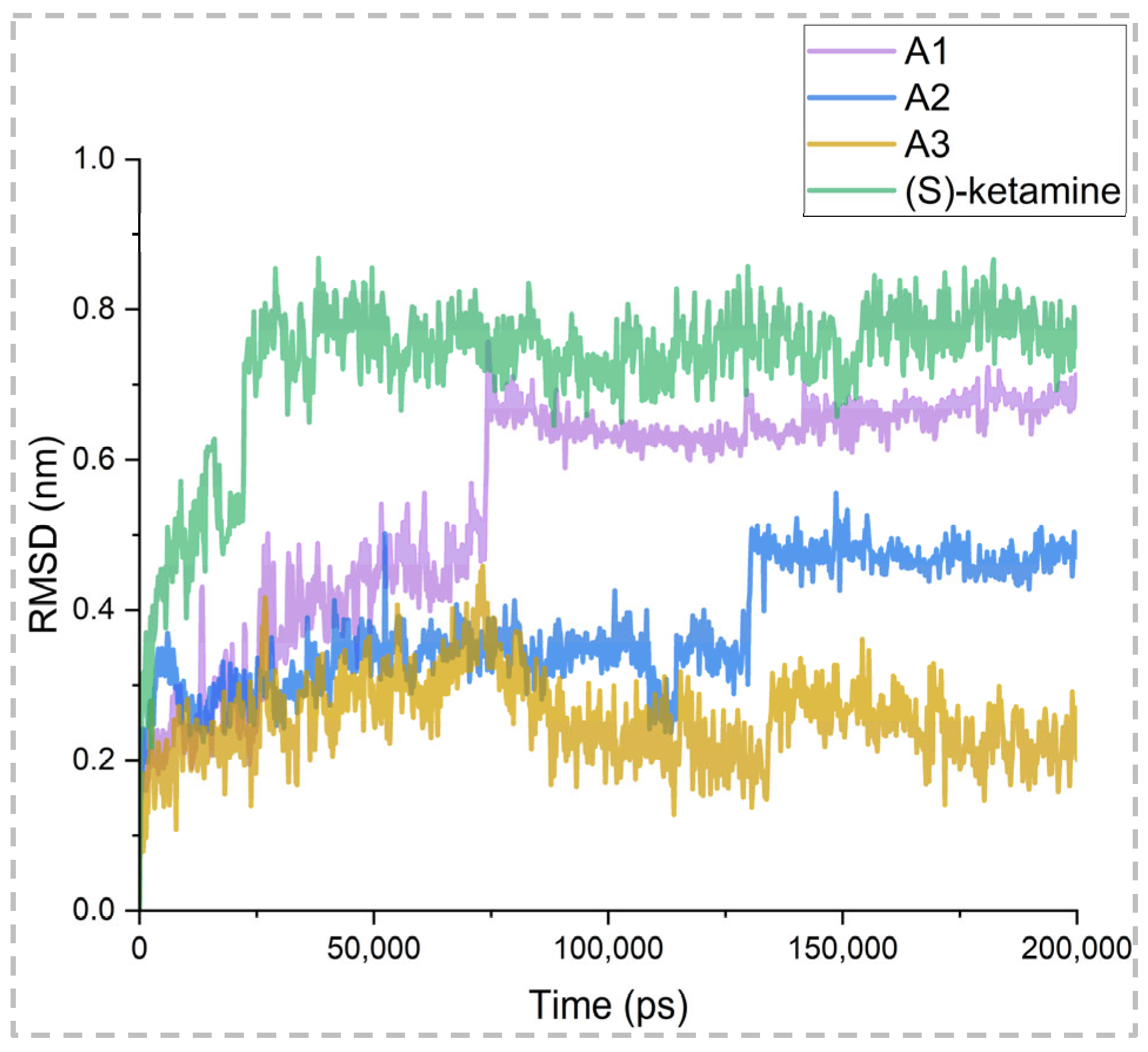

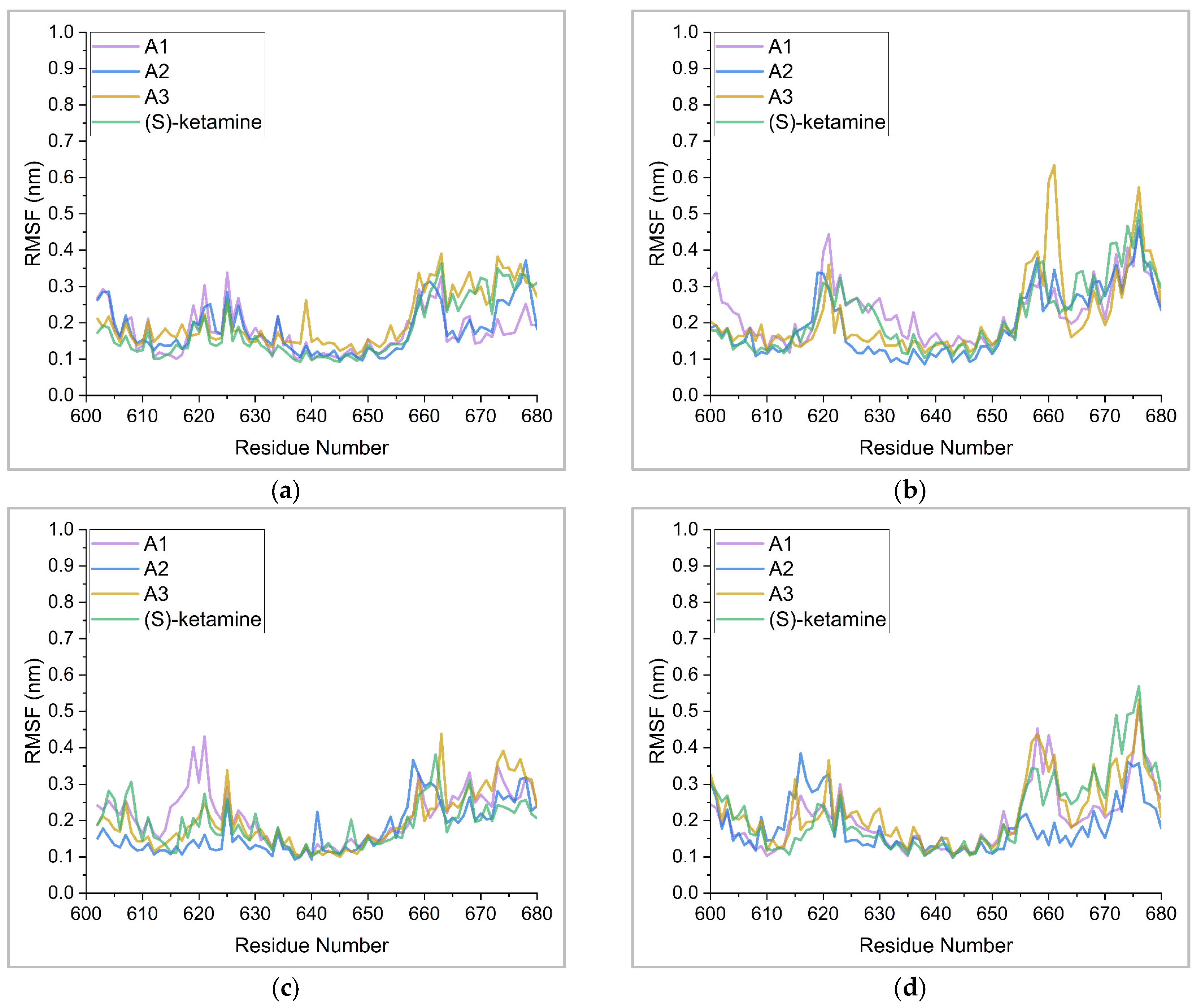

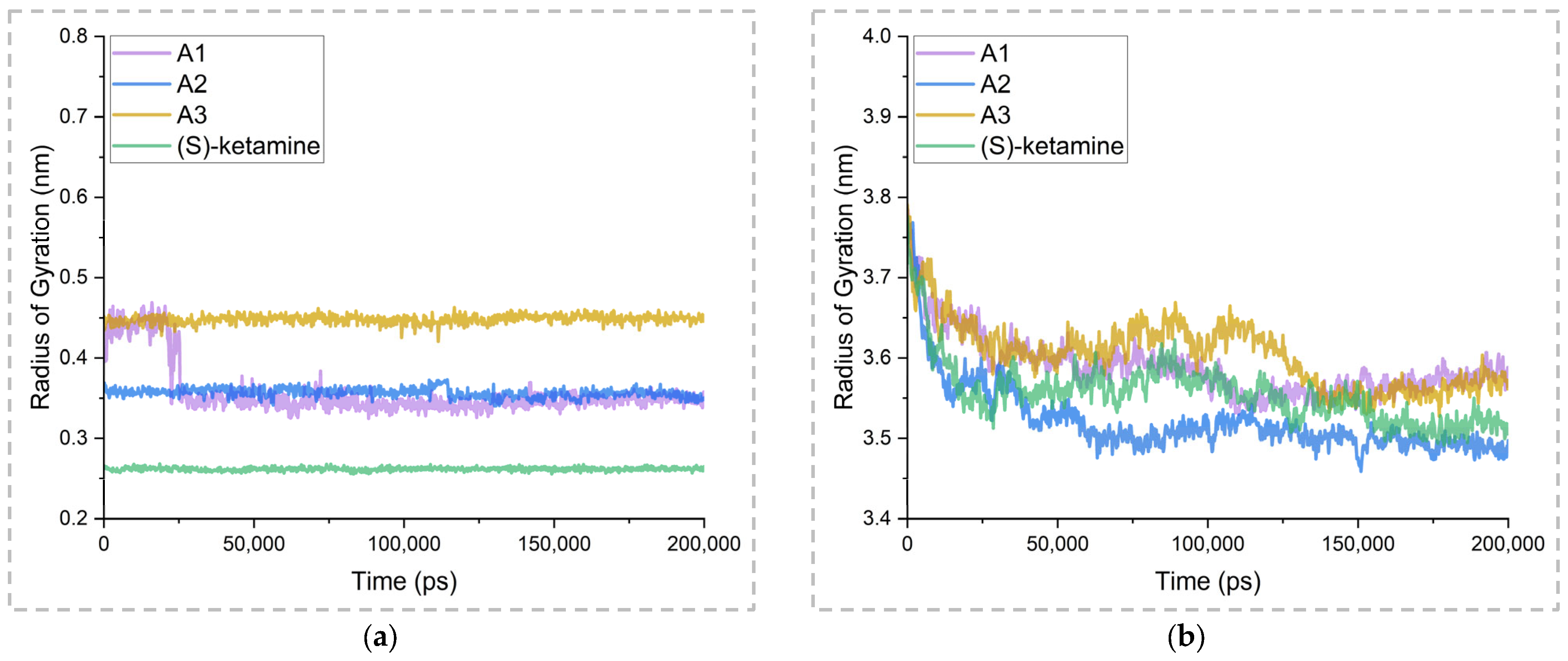

2.5. Binding Stability Analysis Based on Post-MD Simulations

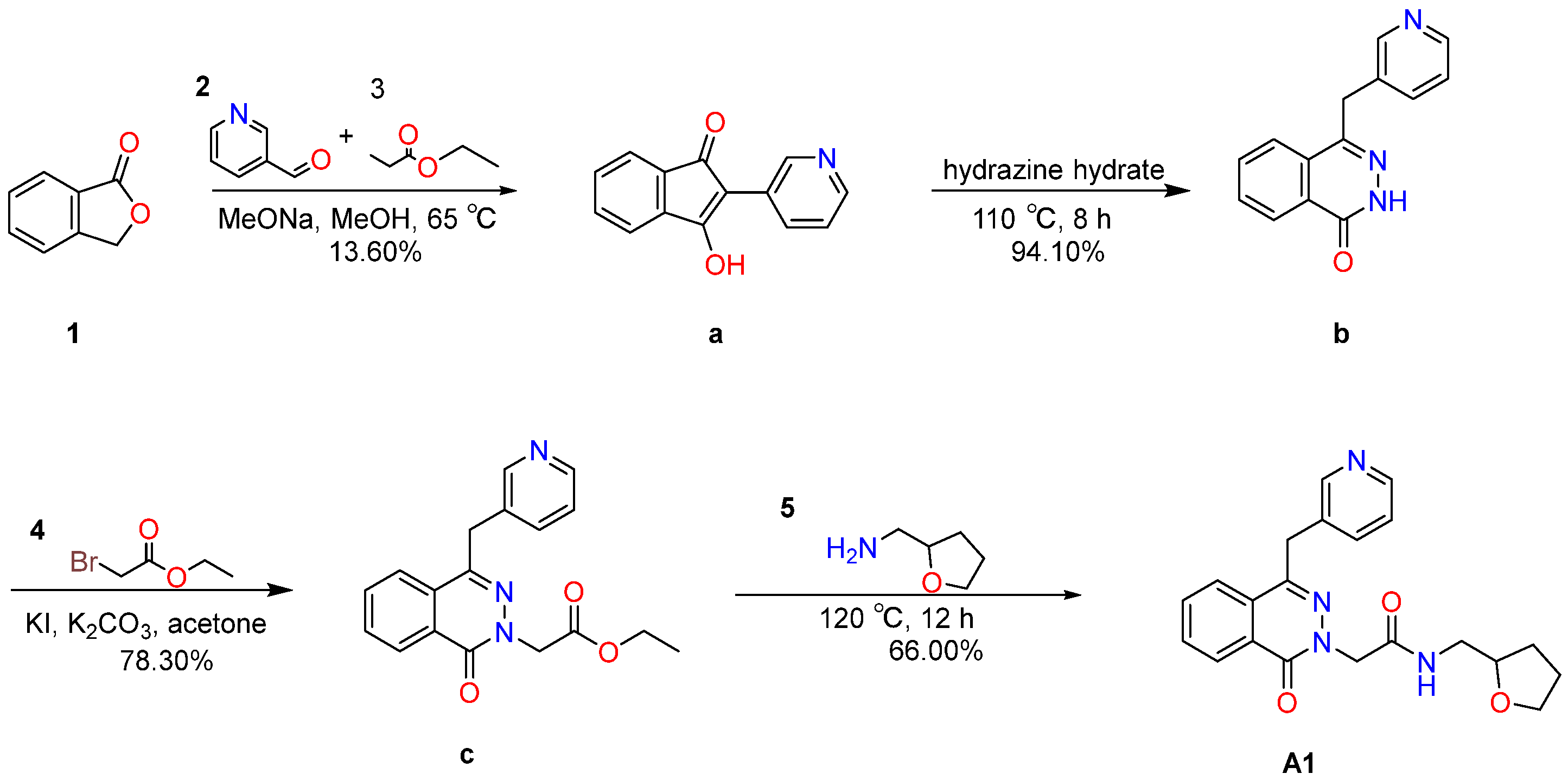

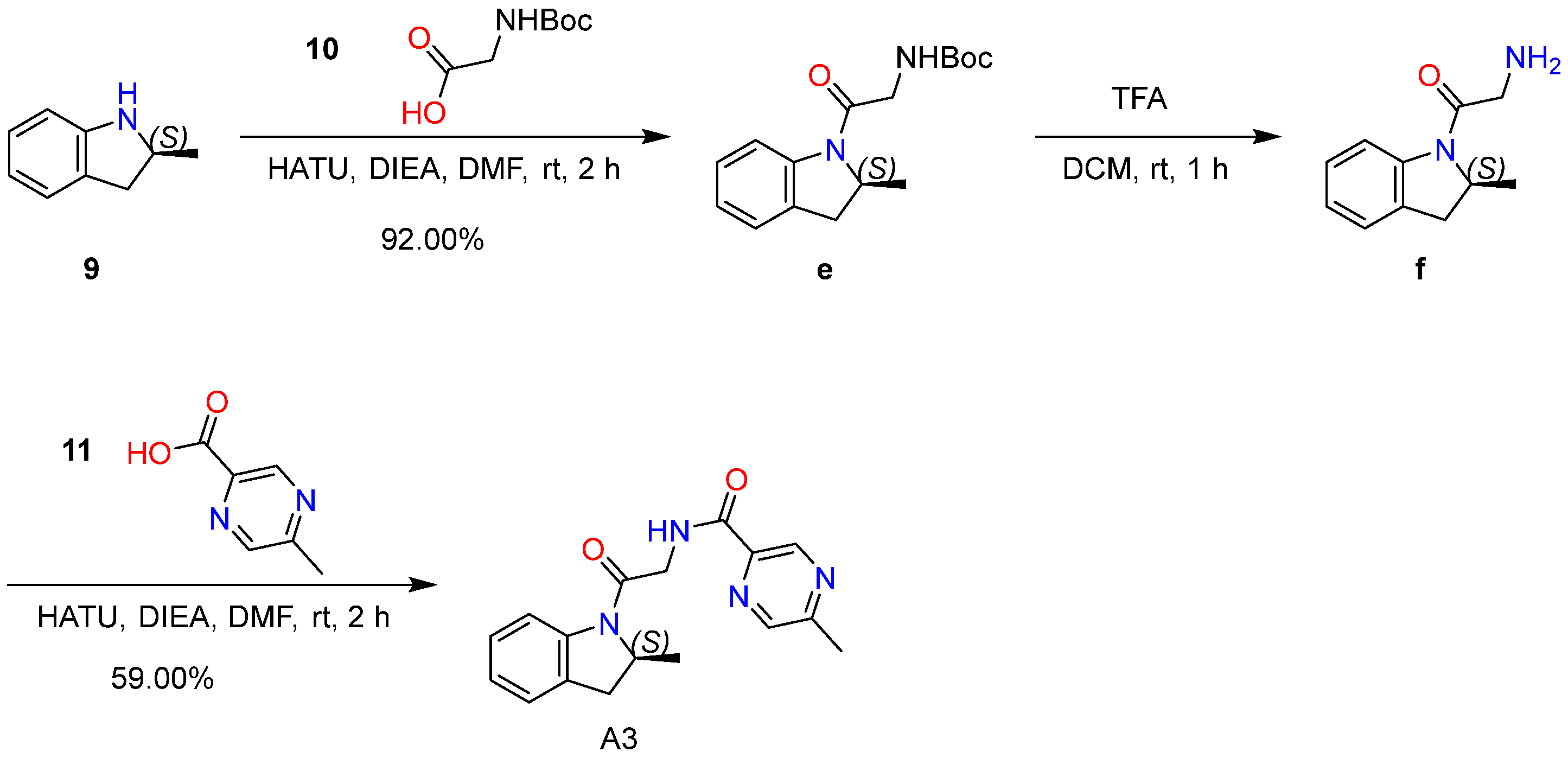

2.6. Compounds Synthesis and Characterization

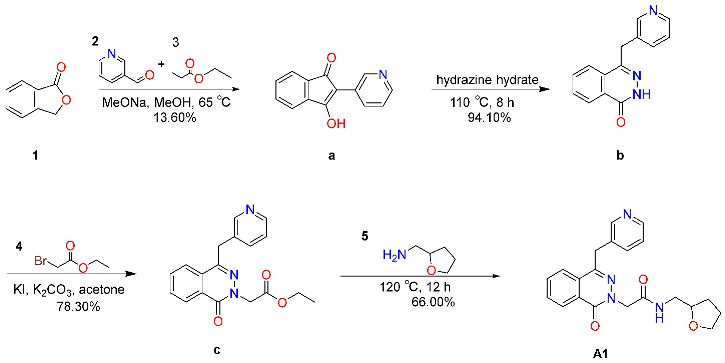

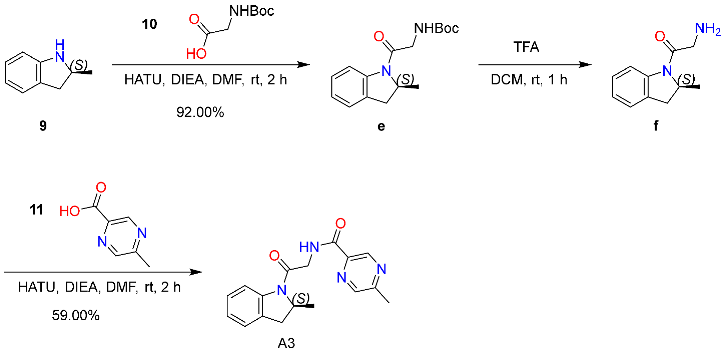

2.6.1. Synthesis and Characterization of Compound A1

2.6.2. Synthesis and Characterization of Compound A2

2.6.3. Synthesis and Characterization of Compound A3

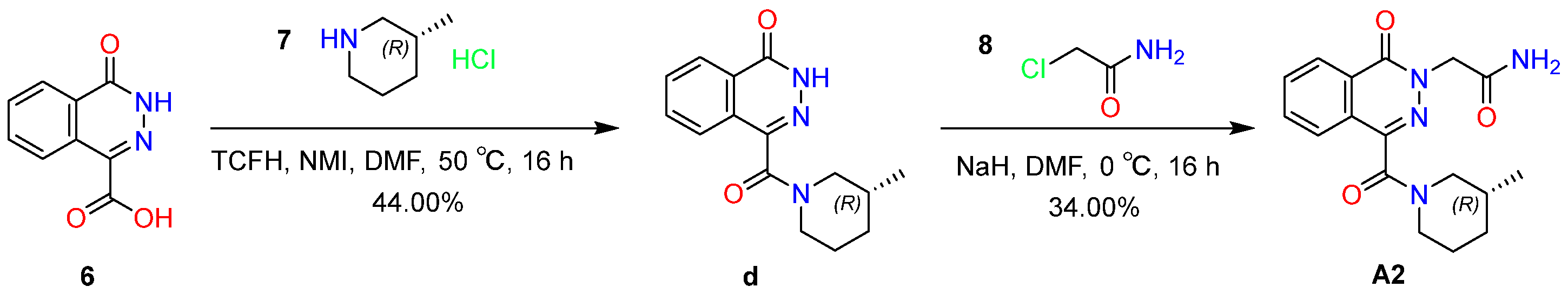

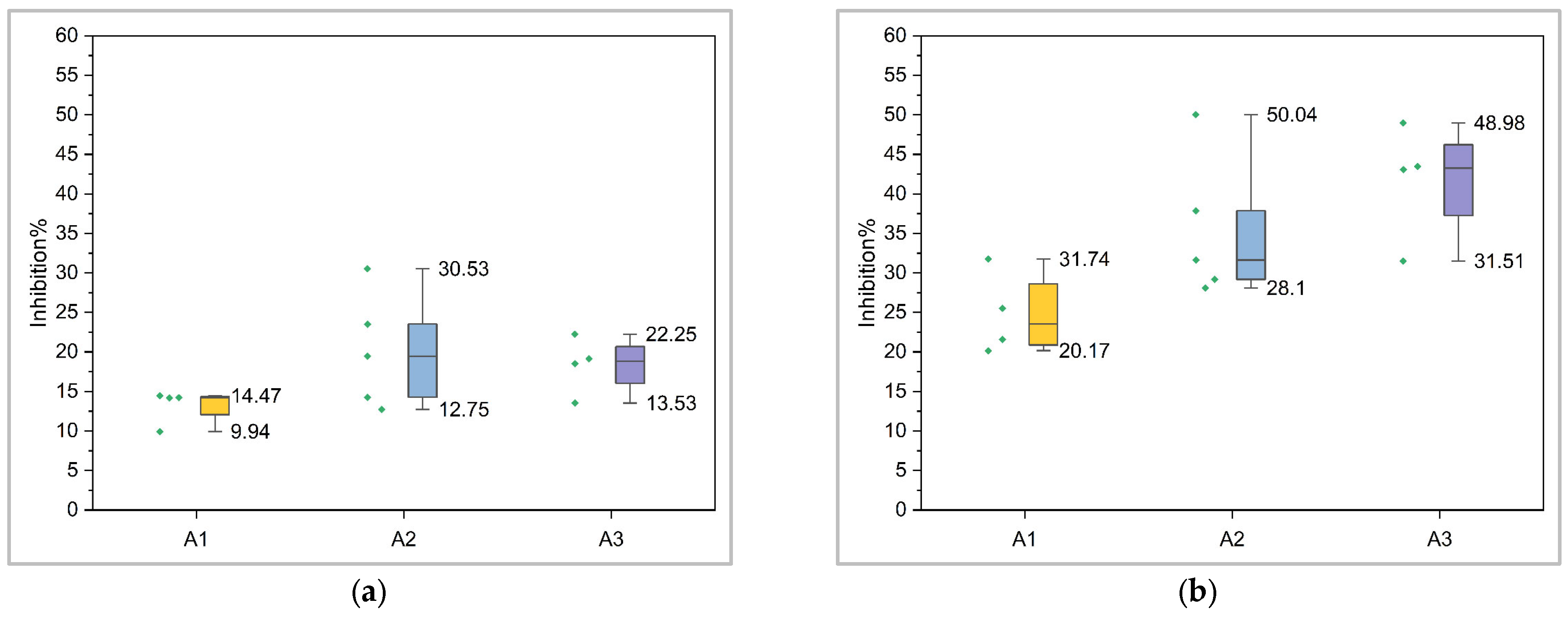

2.7. Electrophysiological Results

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Experimental Reagents

4.2. Preparation of Protein and Ligands

4.3. De Novo Design Using DrugFlow Platform

4.4. Virtual Screening Strategies

4.5. Molecular Dynamics Simulation

4.6. Binding Free Energy Calculations Using MM-PBSA

4.7. Synthetic Procedures

4.7.1. Synthesis of Compound A1

4.7.2. Synthesis of Compound A2

4.7.3. Synthesis of Compound A3

4.8. Electrophysiology

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| RCSB | Research collaboratory for structural bioinformatics |

| OPLS4 | Optimized potentials for liquid simulations 4 |

| ECFP4 | Extended connectivity fingerprints 4 |

| CHARMM-GUI | Chemistry at Harvard macromolecular mechanics graphical user interface |

| TIP3P | Three-point water model |

| AMBER | Assisted model building with energy refinement |

| GROMACS | Groningen machine for chemical simulation |

References

- Klodowski, D.A.; Goldenholz, S.R.; Goldenholz, D.M. Epilepsy and Placebo: A Literature Review. Neurol. Clin. 2026, 4, 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhi, G.S.; Mann, J.J. Depression. Lancet 2018, 392, 2299–2312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raffard, S.; de Connor, A.; Freeman, D.; Bortolon, C. Recent developments in the modeling and psychological management of persecutory ideation. L’encephale 2023, 50, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balmer, G.L.; Guha, S.; Poll, S. Engrams across diseases: Different pathologies-unifying mechanisms? Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 2025, 219, 108036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feigin, V.L.; Vos, T.; Nichols, E.; Owolabi, M.O.; Carroll, W.M.; Dichgans, M.; Deuschl, G.; Parmar, P.; Brainin, M.; Murray, C. The global burden of neurological disorders: Translating evidence into policy. Lancet Neurol. 2020, 19, 255–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capó, T.; Rebassa, J.B.; Raïch, I.; Lillo, J.; Badia, P.; Navarro, G.; Reyes-Resina, I. Future Perspectives of NMDAR in CNS Disorders. Molecules 2025, 30, 877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seillier, C.; Lesept, F.; Toutirais, O.; Potzeha, F.; Blanc, M.; Vivien, D. Targeting NMDA Receptors at the Neurovascular Unit: Past and Future Treatments for Central Nervous System Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 10336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakashima, M.; Suga, N.; Yoshikawa, S.; Matsuda, S. Caveolae with GLP-1 and NMDA Receptors as Crossfire Points for the Innovative Treatment of Cognitive Dysfunction Associated with Neurodegenerative Diseases. Molecules 2024, 29, 3922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, K.B.; Yi, F.; Perszyk, R.E.; Furukawa, H.; Wollmuth, L.P.; Gibb, A.J.; Traynelis, S.F. Structure, function, and allosteric modulation of NMDA receptors. J. Gen. Physiol. 2018, 150, 1081–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paoletti, P.; Bellone, C.; Zhou, Q. NMDA receptor subunit diversity: Impact on receptor properties, synaptic plasticity and disease. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2013, 14, 383–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booker, S.A.; Wyllie, D.J. NMDA receptor function in inhibitory neurons. Neuropharmacology 2021, 196, 108609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, D.K.; Stein, I.S.; Zito, K. Ion flux-independent NMDA receptor signaling. Neuropharmacology 2022, 210, 109019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, L.R.; Battle, A.R.; Martinac, B. Remembering Mechanosensitivity of NMDA Receptors. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, L.; Liu, N.; Zhao, F.; Huang, B.; Kang, D.; Zhan, P.; Liu, X. Discovery of GluN2A subtype-selective N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptor ligands. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2024, 14, 1987–2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deep, S.N.; Mitra, S.; Rajagopal, S.; Paul, S.; Poddar, R. GluN2A-NMDA receptor-mediated sustained Ca2+ influx leads to homocysteine-induced neuronal cell death. J. Biol. Chem. 2019, 294, 11154–11165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yavi, M.; Lee, H.; Henter, I.D.; Park, L.T.; Zarate, C.A., Jr. Ketamine treatment for depression: A review. Discov. Ment. Health 2022, 2, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gjerulfsen, C.E.; Krey, I.; Klöckner, C.; Rubboli, G.; Lemke, J.R.; Møller, R.S. Spectrum of NMDA Receptor Variants in Neurodevelopmental Disorders and Epilepsy. Methods Mol. Biol. 2024, 2799, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Su, T.; Lu, Y.; Fu, C.; Geng, Y.; Chen, Y. GluN2A mediates ketamine-induced rapid antidepressant-like responses. Nat. Neurosci. 2023, 26, 1751–1761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michael, A.; Onisiforou, A.; Georgiou, P.; Koumas, M.; Powels, C.; Mammadov, E.; Georgiou, A.N.; Zanos, P. (2R, 6R)-hydroxynorketamine prevents opioid abstinence-related negative affect and stress-induced reinstatement in mice. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2025, 182, 3428–3451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanos, P.; Brown, K.A.; Georgiou, P.; Yuan, P.; Zarate, C.A.; Thompson, S.M.; Gould, T.D. NMDA Receptor Activation-Dependent Antidepressant-Relevant Behavioral and Synaptic Actions of Ketamine. J. Neurosci. 2023, 43, 1038–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebert, B.; Mikkelsen, S.; Thorkildsen, C.; Borgbjerg, F.M. Norketamine, the main metabolite of ketamine, is a non-competitive NMDA receptor antagonist in the rat cortex and spinal cord. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1997, 333, 99–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Huang, H.; Li, Y.; Zhang, R.; Wei, Y.; Wu, W. Severe Encephalatrophy and Related Disorders From Long-Term Ketamine Abuse: A Case Report and Literature Review. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 707326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scotton, E.; Antqueviezc, B.; de Vasconcelos, M.F.; Dalpiaz, G.; Géa, L.P.; Goularte, J.F.; Colombo, R.; Rosa, A.R. Is (R)-ketamine a potential therapeutic agent for treatment-resistant depression with less detrimental side effects? A review of molecular mechanisms underlying ketamine and its enantiomers. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2022, 198, 114963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, S.; Han, Y.; Wei, Z.; Li, J. Binding Affinity and Mechanisms of Potential Antidepressants Targeting Human NMDA Receptors. Molecules 2023, 28, 4346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, C.; Kobayashi, S.; Nakao, K.; Dong, C.; Han, M.; Qu, Y.; Ren, Q.; Zhang, J.C.; Ma, M.; Toki, H. AMPA Receptor Activation-Independent Antidepressant Actions of Ketamine Metabolite (S)-Norketamine. Biol. Psychiatry 2018, 84, 591–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zhu, X.; Wu, M.; Yang, L.; Yao, Z.; Xie, Q.; Liu, X.; Li, C. Safety, tolerability, pharmacodynamics, and pharmacokinetics of CJC-1134-PC in healthy Chinese subjects and type-2 diabetic subjects. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs 2021, 30, 1241–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piazza, M.K.; Kavalali, E.T.; Monteggia, L.M. Ketamine induced synaptic plasticity operates independently of long-term potentiation. Neuropsychopharmacology 2024, 49, 1758–1766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angel, I.; Perelroizen, R.; Deffains, W.; Adraoui, F.W.; Pichinuk, E.; Aminov, E. KETAMIR-2, a new molecular entity and novel ketamine analog. Front. Pharmacol. 2025, 16, 1606976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinde, P.B.; Bhowmick, S.; Alfantoukh, E.; Patil, P.C.; Wabaidur, S.M.; Chikhale, R.V.; Islam, M.A. De novo design based identification of potential HIV-1 integrase inhibitors: A pharmacoinformatics study. Comput. Biol. Chem. 2020, 88, 107319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Chowdhury, S.; Kumar, S. In silico repurposing of antipsychotic drugs for Alzheimer’s disease. BMC Neurosci. 2017, 18, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhang, J.; Guo, R.; Dai, J.; Niu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Wang, T.; Jiang, X.; Hu, W. Progress of machine learning in the application of small molecule druggability prediction. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2025, 285, 117269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evren, A.E.; Hıdır, A.; Kurban, B.; Özkan, B.N.S.; Levent, S.; Şahin, A.; Özkay, Y.; Gündoğdu-Karaburun, N. Latest developments in small molecule analgesics: Heterocyclic scaffolds II. Future Med. Chem. 2025, 17, 2391–2405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Ye, F.; Zhang, T.; Lv, S.; Zhou, L.; Du, D.; Lin, H.; Guo, F.; Luo, C.; Zhu, S. Structural basis of ketamine action on human NMDA receptors. Nature 2021, 596, 301–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Cui, Y.; Sang, K.; Dong, Y.; Ni, Z.; Ma, S.; Hu, H. Ketamine blocks bursting in the lateral habenula to rapidly relieve depression. Nature 2018, 554, 317–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moda-Sava, R.N.; Murdock, M.H.; Parekh, P.K.; Fetcho, R.N.; Huang, B.S.; Huynh, T.N.; Witztum, J.; Shaver, D.C.; Rosenthal, D.L.; Alway, E.J. Sustained rescue of prefrontal circuit dysfunction by antidepressant-induced spine formation. Science 2019, 364, eaat8078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, O.; Zhang, J.; Jin, J.; Zhang, X.; Hu, R.; Shen, C.; Cao, H.; Du, H.; Kang, Y.; Deng, Y.; et al. ResGen is a pocket-aware 3D molecular generation model based on parallel multiscale modelling. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2023, 5, 1020–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, D.; Hahn, M. Extended-Connectivity Fingerprints. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2010, 50, 742–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, X.; Chen, R.; Yang, X.; He, X.; Pan, Z.; Yao, C.; Peng, H.; Yang, H.; Huang, W.; Chen, Z. Discovery of Novel DDR1 Inhibitors through a Hybrid Virtual Screening Pipeline, Biological Evaluation and Molecular Dynamics Simulations. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2025, 16, 602–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, O.; Shen, C.; Qu, W.; Chen, S.; Cao, H.; Kang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Wang, E.; Zhang, J.; et al. Efficient and accurate large library ligand docking with KarmaDock. Nat. Comput. Sci. 2023, 3, 789–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adasme, M.F.; Linnemann, K.L.; Bolz, S.N.; Kaiser, F.; Salentin, S.; Haupt, V.J.; Schroeder, M. PLIP 2021: Expanding the scope of the protein-ligand interaction profiler to DNA and RNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, W530–W534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, H.; Shen, C.; Jian, T.; Zhang, X.; Chen, T.; Han, X.; Yang, Z.; Dang, W.; Hsieh, C.-Y.; Kang, Y. CarsiDock: A deep learning paradigm for accurate protein-ligand docking and screening based on large-scale pre-training. Chem. Sci. 2024, 15, 1449–1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, C.; Zhang, X.; Deng, Y.; Gao, J.; Wang, D.; Xu, L.; Pan, P.; Hou, T.; Kang, Y. Boosting Protein-Ligand Binding Pose Prediction and Virtual Screening Based on Residue-Atom Distance Likelihood Potential and Graph Transformer. J. Med. Chem. 2022, 65, 10691–10706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maestro. Schrödinger, Inc. 15.0. 2025. Available online: https://www.schrodinger.com (accessed on 13 August 2025).

- Ertl, P.; Schuffenhauer, A. Estimation of synthetic accessibility score of drug-like molecules based on molecular complexity and fragment contributions. J. Cheminform. 2009, 1, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, E.; Sun, H.; Wang, J.; Wang, Z.; Liu, H.; Zhang, J.Z.; Hou, T. End-point binding free energy calculation with MM/PBSA and MM/GBSA: Strategies and applications in drug design. Chem. Rev. 2019, 119, 9478–9508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swetha, R.; Sharma, A.; Singh, R.; Ganeshpurkar, A.; Kumar, D.; Kumar, A.; Singh, S.K. Combined ligand-based and structure-based design of PDE 9A inhibitors against Alzheimer’s disease. Mol. Divers. 2022, 26, 2877–2892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajasekhar, S.; Das, S.; Karuppasamy, R.; Musuvathi Motilal, B.; Chanda, K. Identification of novel inhibitors for Prp protein of Mycobacterium tuberculosis by structure based drug design, and molecular dynamics simulations. J. Comput. Chem. 2022, 43, 619–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, L.; Shi, S.; Yi, J.; Wang, N.; He, Y.; Wu, Z.; Peng, J.; Deng, Y.; Wang, W.; Wu, C. ADMETlab 3.0: An updated comprehensive online ADMET prediction platform enhanced with broader coverage, improved performance, API functionality and decision support. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024, 52, W422–W431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajasekhar, S.; Karuppasamy, R.; Chanda, K. Exploration of potential inhibitors for tuberculosis via structure-based drug design, molecular docking, and molecular dynamics simulation studies. J. Comput. Chem. 2021, 42, 1736–1749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granzotto, A.; d’Aurora, M.; Bomba, M.; Gatta, V.; Onofrj, M.; Sensi, S.L. Long-Term Dynamic Changes of NMDA Receptors Following an Excitotoxic Challenge. Cells 2022, 11, 911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehinger, R.; Kuret, A.; Matt, L.; Frank, N.; Wild, K.; Kabagema-Bilan, C.; Bischof, H.; Malli, R.; Ruth, P.; Bausch, A.E. Slack K+ channels attenuate NMDA-induced excitotoxic brain damage and neuronal cell death. FASEB J. 2021, 35, e21568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammad Shehata, I.; Masood, W.; Nemr, N.; Anderson, A.; Bhusal, K.; Edinoff, A.N.; Cornett, E.M.; Kaye, A.M.; Kaye, A.D. The Possible Application of Ketamine in the Treatment of Depression in Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurol. Int. 2022, 14, 310–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Hwang, L.; Burley, S.K.; Nitsche, C.I.; Southan, C.; Walters, W.P.; Gilson, M.K. BindingDB in 2024: A FAIR knowledgebase of protein-small molecule binding data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2025, 53, D1633–D1644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zdrazil, B.; Felix, E.; Hunter, F.; Manners, E.J.; Blackshaw, J.; Corbett, S.; De Veij, M.; Ioannidis, H.; Lopez, D.M.; Mosquera, J.F. The ChEMBL Database in 2023: A drug discovery platform spanning multiple bioactivity data types and time periods. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024, 52, D1180–D1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, C.; Song, J.; Hsieh, C.-Y.; Cao, D.; Kang, Y.; Ye, W.; Wu, Z.; Wang, J.; Zhang, O.; Zhang, X. DrugFlow: An AI-driven One-Stop Platform for Innovative Drug Discovery. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2024, 64, 5381–5391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, D.; Lei, T.; Wang, Z.; Shen, C.; Cao, D.; Hou, T. ADMET evaluation in drug discovery. 20. Prediction of breast cancer resistance protein inhibition through machine learning. J. Cheminform. 2020, 12, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, G.; Wu, Z.; Yi, J.; Fu, L.; Yang, Z.; Hsieh, C.; Yin, M.; Zeng, X.; Wu, C.; Lu, A. ADMETlab 2.0: An integrated online platform for accurate and comprehensive predictions of ADMET properties. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, W5–W14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, X.; Su, Q.; Du, H.; Shen, C.; Li, D.; Wang, Z.; Pan, P.; Chen, G.; et al. Delete: Deep Lead Optimization Enveloped in Protein Pocket through Unified Deleting Strategies and a Structure-aware Network. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2308.02172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RDKit: Open-Source Cheminformatics. Available online: https://www.rdkit.org (accessed on 6 August 2025).

- Jo, S.; Kim, T.; Iyer, V.G.; Im, W. CHARMM-GUI: A web-based graphical user interface for CHARMM. J. Comput. Chem. 2008, 29, 1859–1865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdés-Tresanco, M.S.; Valdés-Tresanco, M.E.; Valiente, P.A.; Moreno, E. gmx_MMPBSA: A New Tool to Perform End-State Free Energy Calculations with GROMACS. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2021, 17, 6281–6291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Molecule | ΔGbinding | ΔEEL | ΔEVDWAALS | ΔENPOLAR | ΔEPB |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | −26.33 | −14.57 | −41.36 | −4.64 | 34.23 |

| A2 | −21.49 | −15.45 | −37.49 | −4.25 | 35.70 |

| A3 | −20.70 | −9.19 | −34.05 | −4.02 | 26.55 |

| (S)-ketamine | −18.98 | −2.88 | −26.73 | −3.09 | 13.71 |

| Molecule | QED | MW | TPSA | log S | log P | HIA− | BBB+ | CLplasma |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | 0.71 | 378.17 | 86.11 | −2.78 | 1.36 | 4.29 × 106 | 0.60 | 3.00 |

| A2 | 0.90 | 328.15 | 98.29 | −2.50 | 0.86 | 1.91 × 106 | 0.80 | 3.14 |

| A3 | 0.93 | 310.14 | 75.19 | −1.79 | 1.34 | 5.27 × 105 | 0.89 | 7.37 |

| (S)-ketamine | 0.86 | 237.09 | 29.10 | −2.90 | 2.10 | 1.80 × 105 | 0.99 | 7.55 |

| Complex | A1 | A2 | A3 | (S)-Ketamine |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Minimum | 3.94 × 105 | 4.93 × 105 | 4.20 × 105 | 4.29 × 105 |

| Maximum | 0.76 | 0.56 | 0.46 | 0.87 |

| Average | 0.55 | 0.38 | 0.25 | 0.73 |

| Complex | A1 | A2 | A3 | (S)-Ketamine | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protein A chain | Minimum | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.11 | 0.09 |

| Maximum | 0.34 | 0.37 | 0.39 | 0.36 | |

| Average | 0.17 | 0.18 | 0.21 | 0.18 | |

| Protein B chain | Minimum | 0.12 | 0.09 | 0.12 | 0.10 |

| Maximum | 0.48 | 0.46 | 0.63 | 0.51 | |

| Average | 0.23 | 0.20 | 0.22 | 0.22 | |

| Protein C chain | Minimum | 0.10 | 0.09 | 0.10 | 0.10 |

| Maximum | 0.43 | 0.37 | 0.44 | 0.38 | |

| Average | 0.21 | 0.17 | 0.20 | 0.19 | |

| Protein D chain | Minimum | 0.10 | 0.11 | 0.10 | 0.10 |

| Maximum | 0.51 | 0.38 | 0.53 | 0.57 | |

| Average | 0.20 | 0.18 | 0.22 | 0.22 | |

| Inhibitors/Complex | A1 | A2 | A3 | (S)-Ketamine | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inhibitors | Minimum | 0.32 | 0.34 | 0.42 | 0.26 |

| Maximum | 0.47 | 0.37 | 0.46 | 0.27 | |

| Average | 0.36 | 0.36 | 0.45 | 0.26 | |

| Complex | Minimum | 3.53 | 3.46 | 3.53 | 3.49 |

| Maximum | 3.79 | 3.78 | 3.79 | 3.78 | |

| Average | 3.59 | 3.52 | 3.61 | 3.56 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Liu, Y.; Yang, Z.; Guo, Y.; Huang, T.; Pan, L.; Ding, J.; Dong, W. De Novo Generation-Based Design of Potential Computational Hits Targeting the GluN1-GluN2A Receptor. Molecules 2026, 31, 522. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31030522

Liu Y, Yang Z, Guo Y, Huang T, Pan L, Ding J, Dong W. De Novo Generation-Based Design of Potential Computational Hits Targeting the GluN1-GluN2A Receptor. Molecules. 2026; 31(3):522. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31030522

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Yibo, Zhijiang Yang, Yixuan Guo, Tengxin Huang, Li Pan, Junjie Ding, and Weifu Dong. 2026. "De Novo Generation-Based Design of Potential Computational Hits Targeting the GluN1-GluN2A Receptor" Molecules 31, no. 3: 522. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31030522

APA StyleLiu, Y., Yang, Z., Guo, Y., Huang, T., Pan, L., Ding, J., & Dong, W. (2026). De Novo Generation-Based Design of Potential Computational Hits Targeting the GluN1-GluN2A Receptor. Molecules, 31(3), 522. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31030522