Germination as a Sustainable Green Pre-Treatment for the Recovery and Enhancement of High-Value Compounds in Broccoli and Kale

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Method

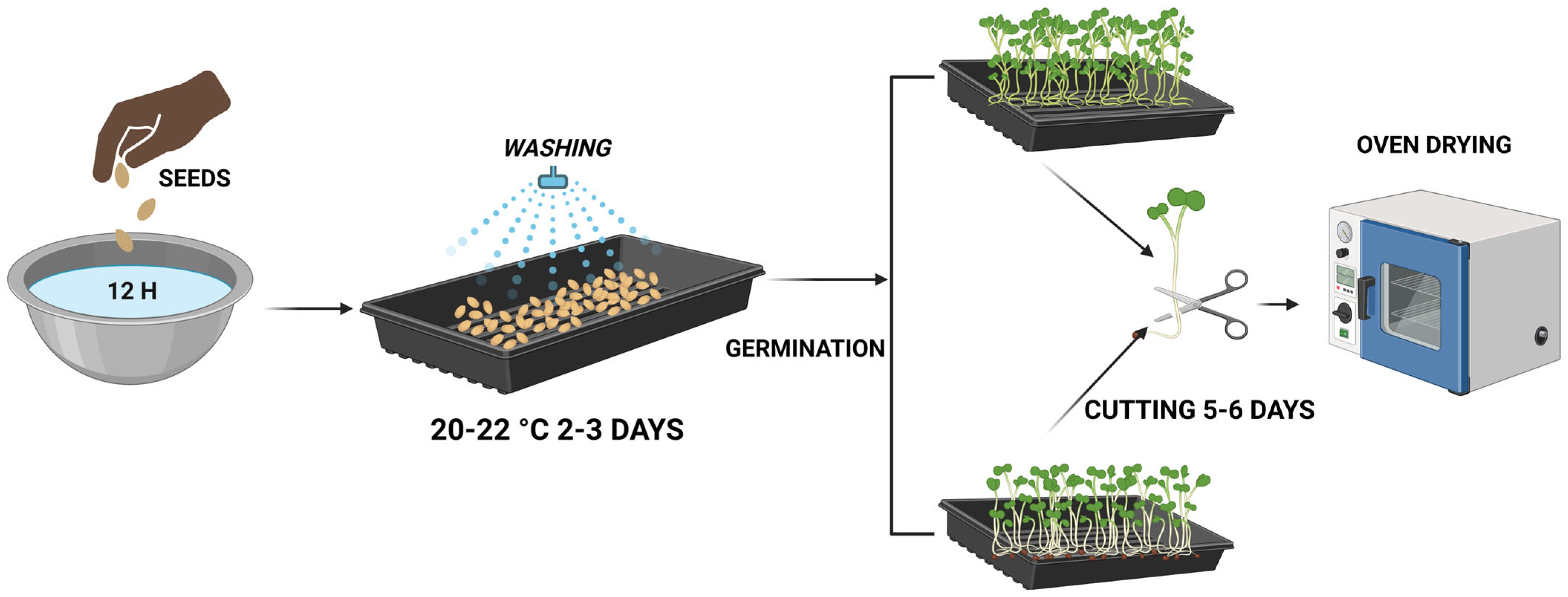

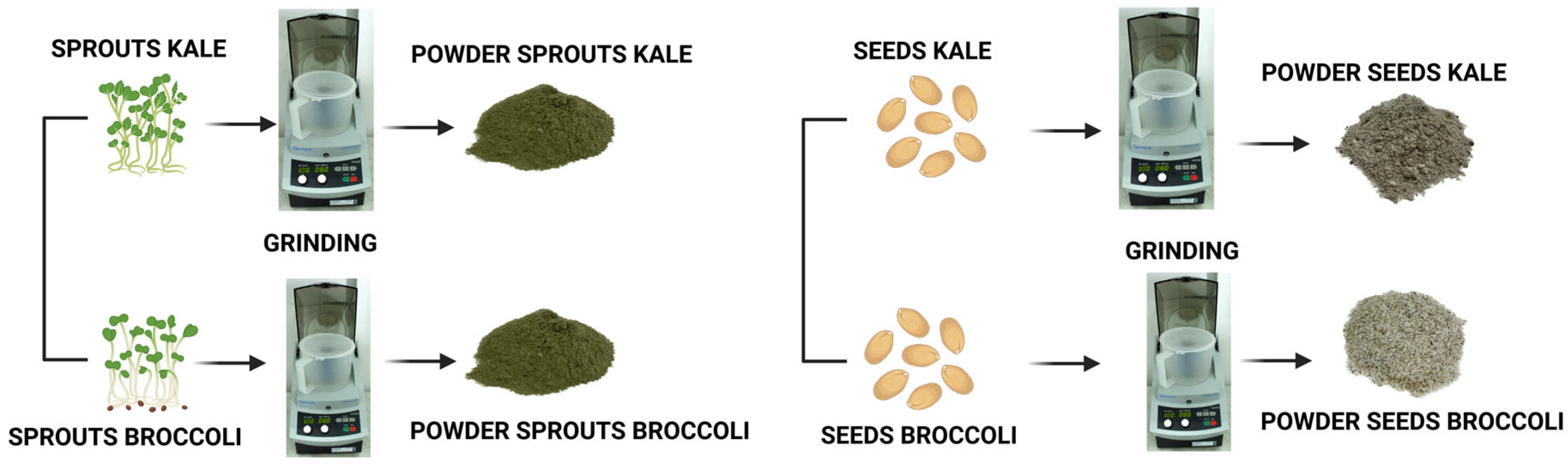

2.1. Seeds Germination

2.2. The Obtaining of Seed and Sprout Powders

2.3. Evaluation of the Nutritional Composition of Kale and Broccoli Seed and Sprout Powders

2.4. Phytochemical Analysis of Kale and Broccoli Seed and Sprout Powders

2.4.1. Total and Individual Phenolics Content

2.4.2. Macro and Microelements Composition

2.5. Antinutritional Compounds (Phytic Acid) of Kale and Broccoli Seed and Sprout Powders

2.6. Structural Analysis of Kale and Broccoli Seed and Sprout Powders

2.6.1. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR)

2.6.2. Small- and Wide-Angle X-Ray Scattering (SAXS/WAXS)

2.7. Determination of Antibacterial Activity of Kale and Broccoli Seed and Sprout Powders

2.7.1. Kirby-Bauer Disk Diffusion Susceptibility Test Protocol

2.7.2. Determination of the Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC)

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Nutritional Composition of Kale and Broccoli Seed and Sprout Powders

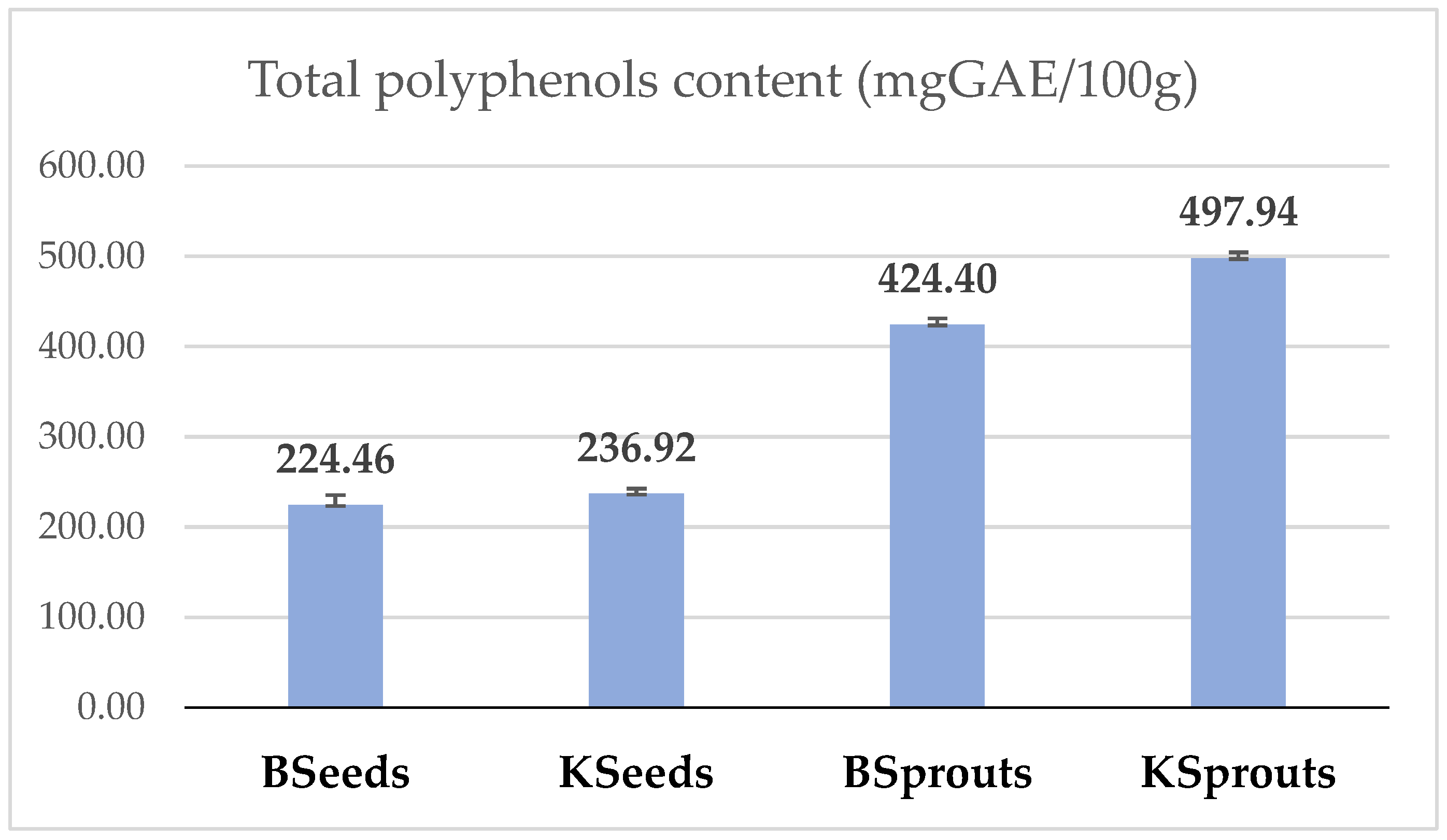

3.2. Total Phenolic Content and Individual Polyphenols of Kale and Broccoli Seed and Sprout Powders

3.3. Macro and Microelements Composition of Kale and Broccoli Seed and Sprout Powders

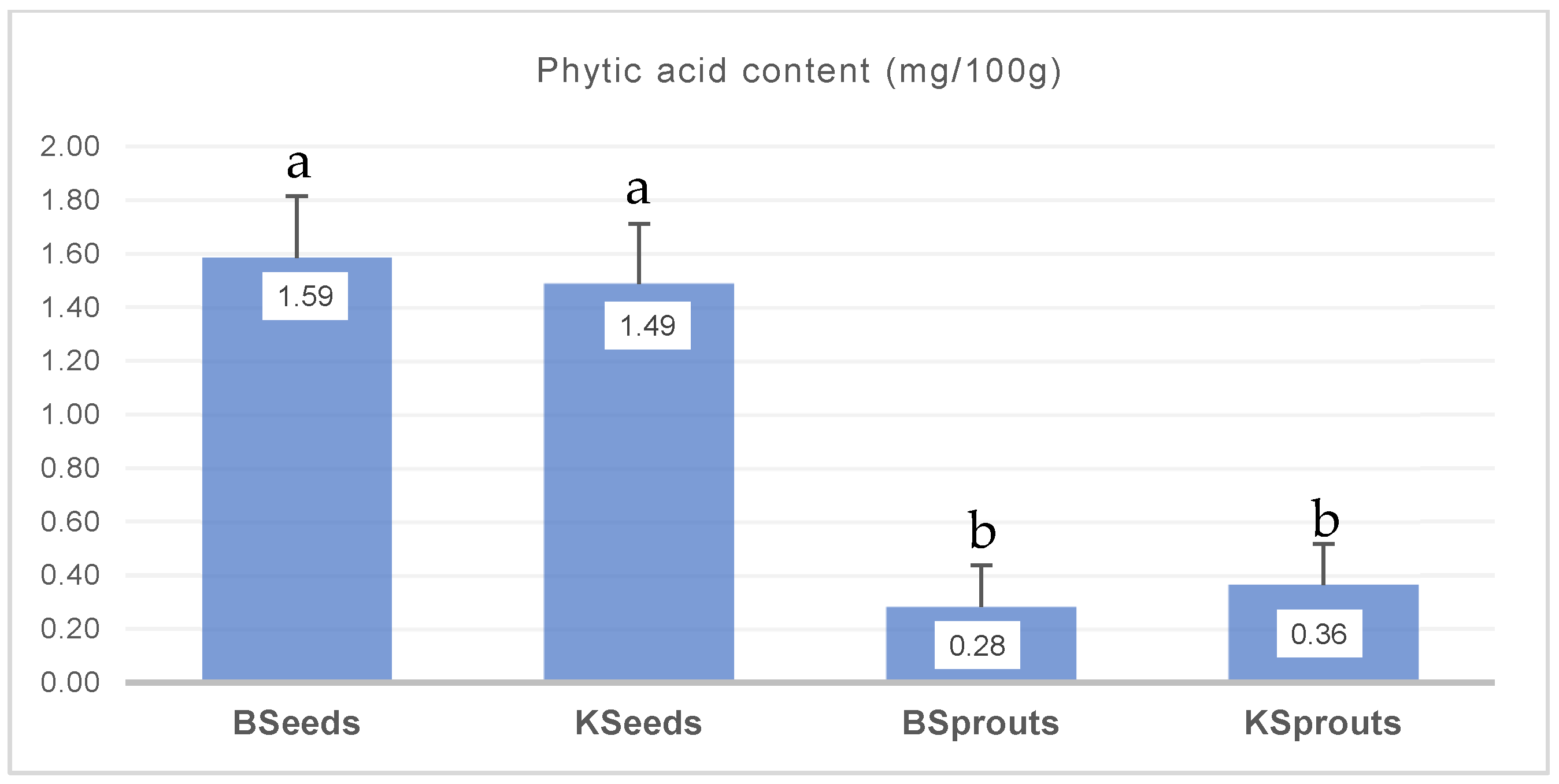

3.4. Antinutritional Compounds—Phytic Acid of Kale and Broccoli Seed and Sprout Powders

3.5. Structural Characteristics of Kale and Broccoli Seed and Sprout Powders

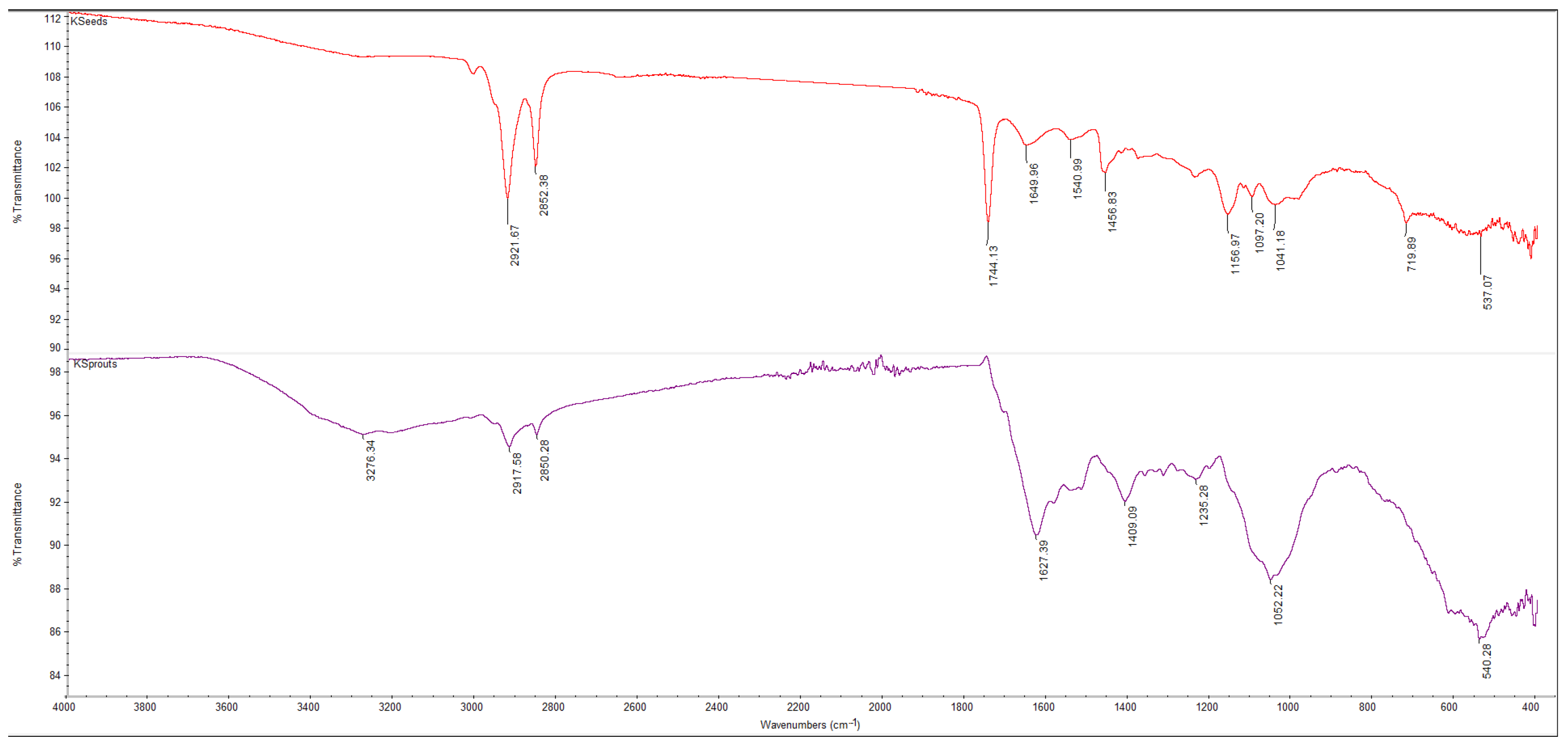

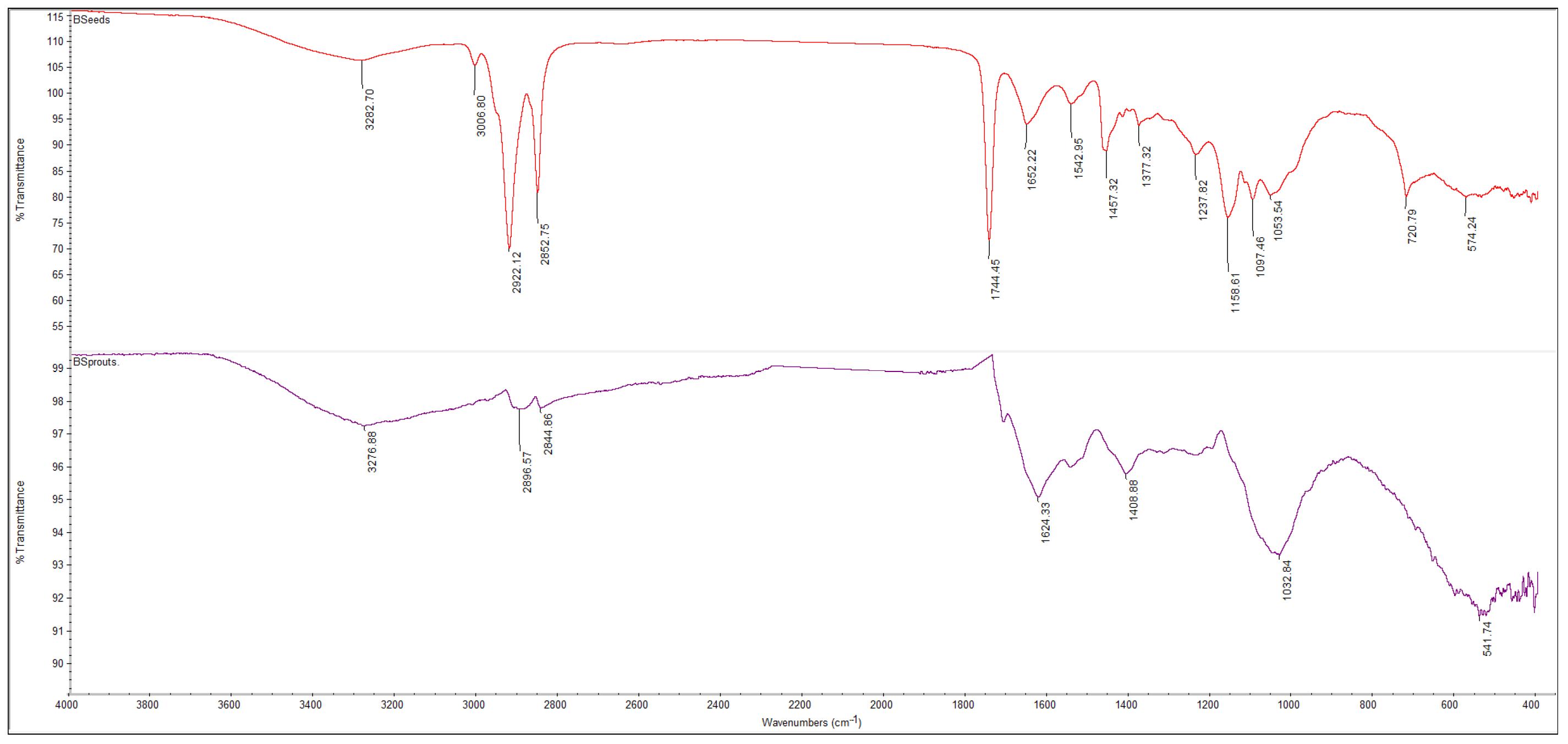

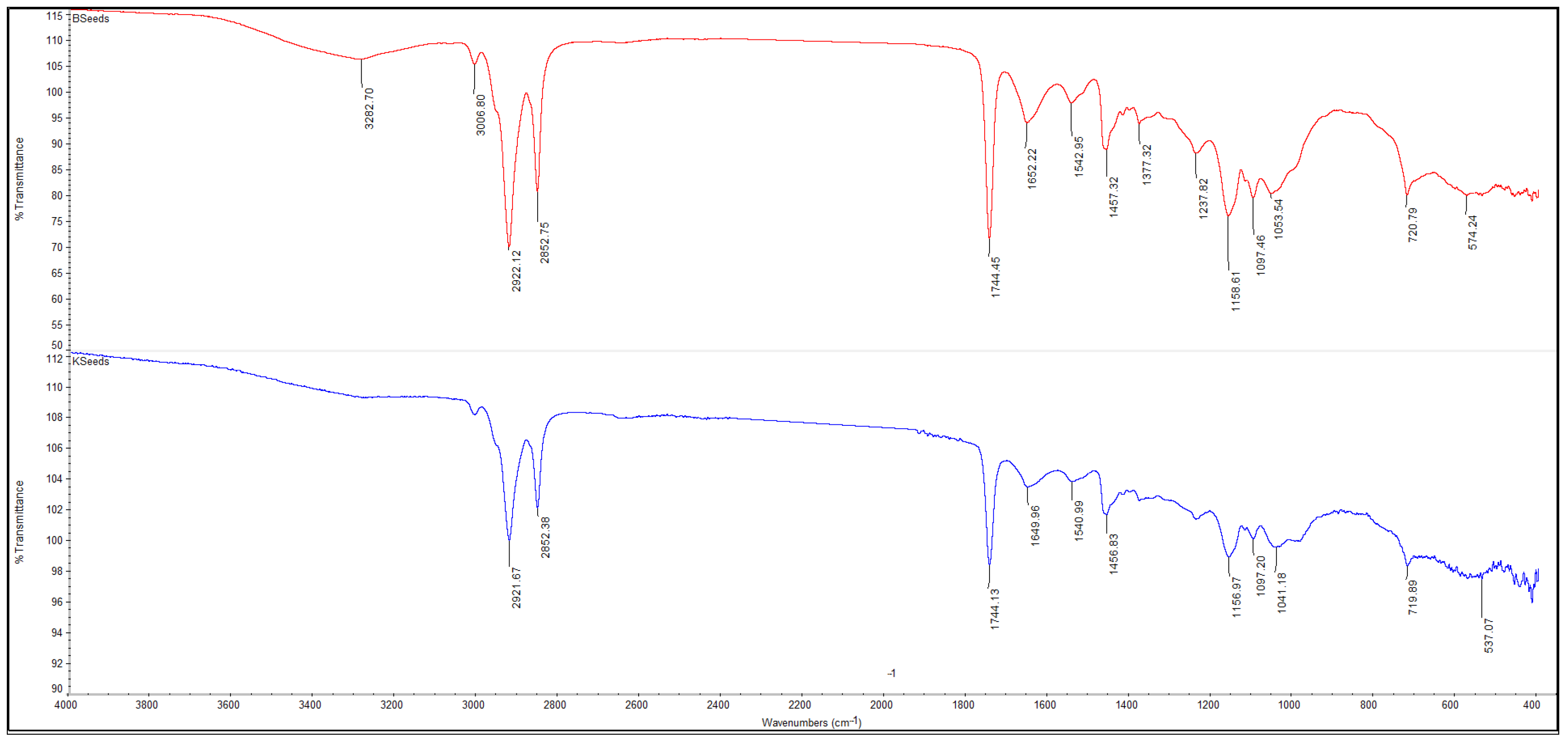

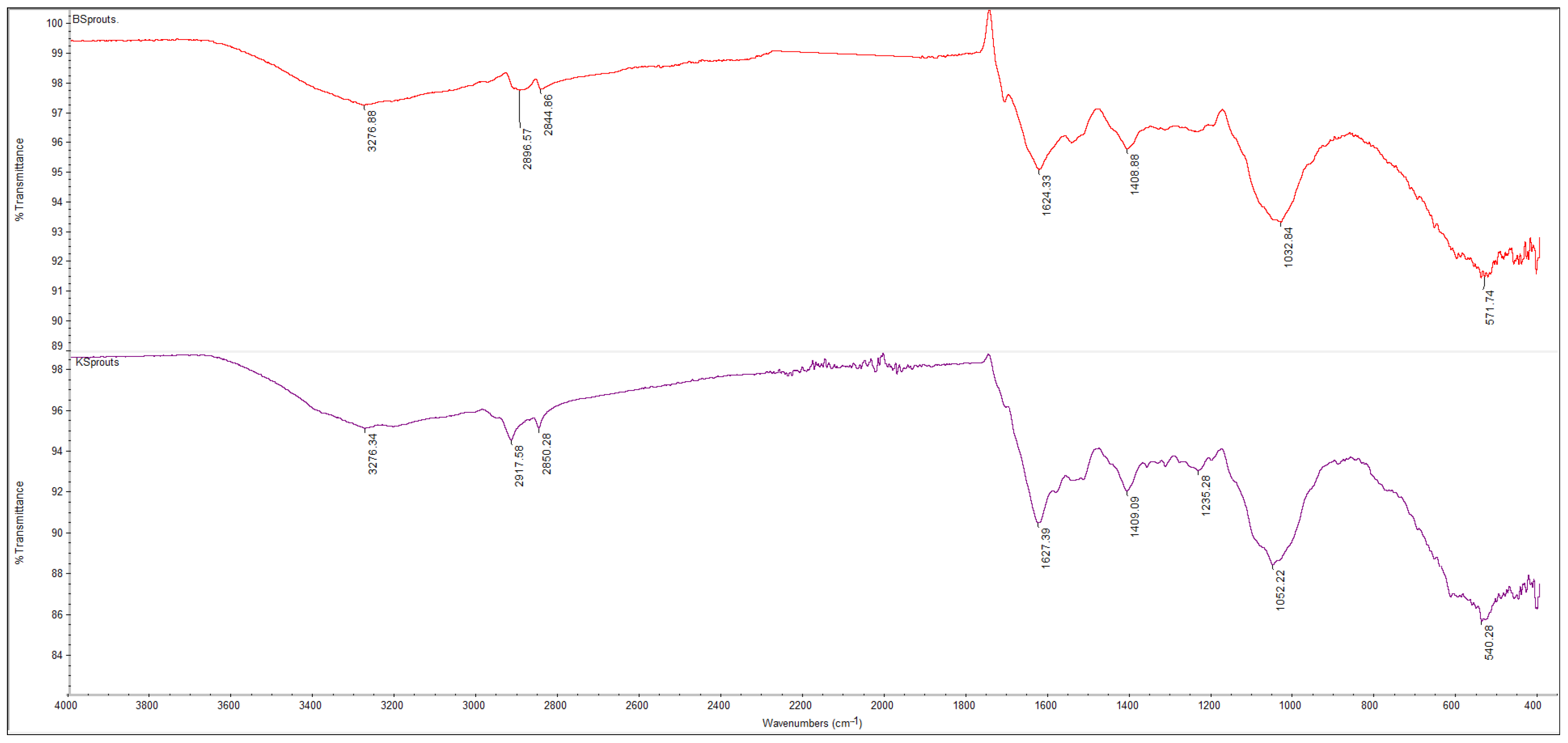

3.5.1. FTIR Spectra

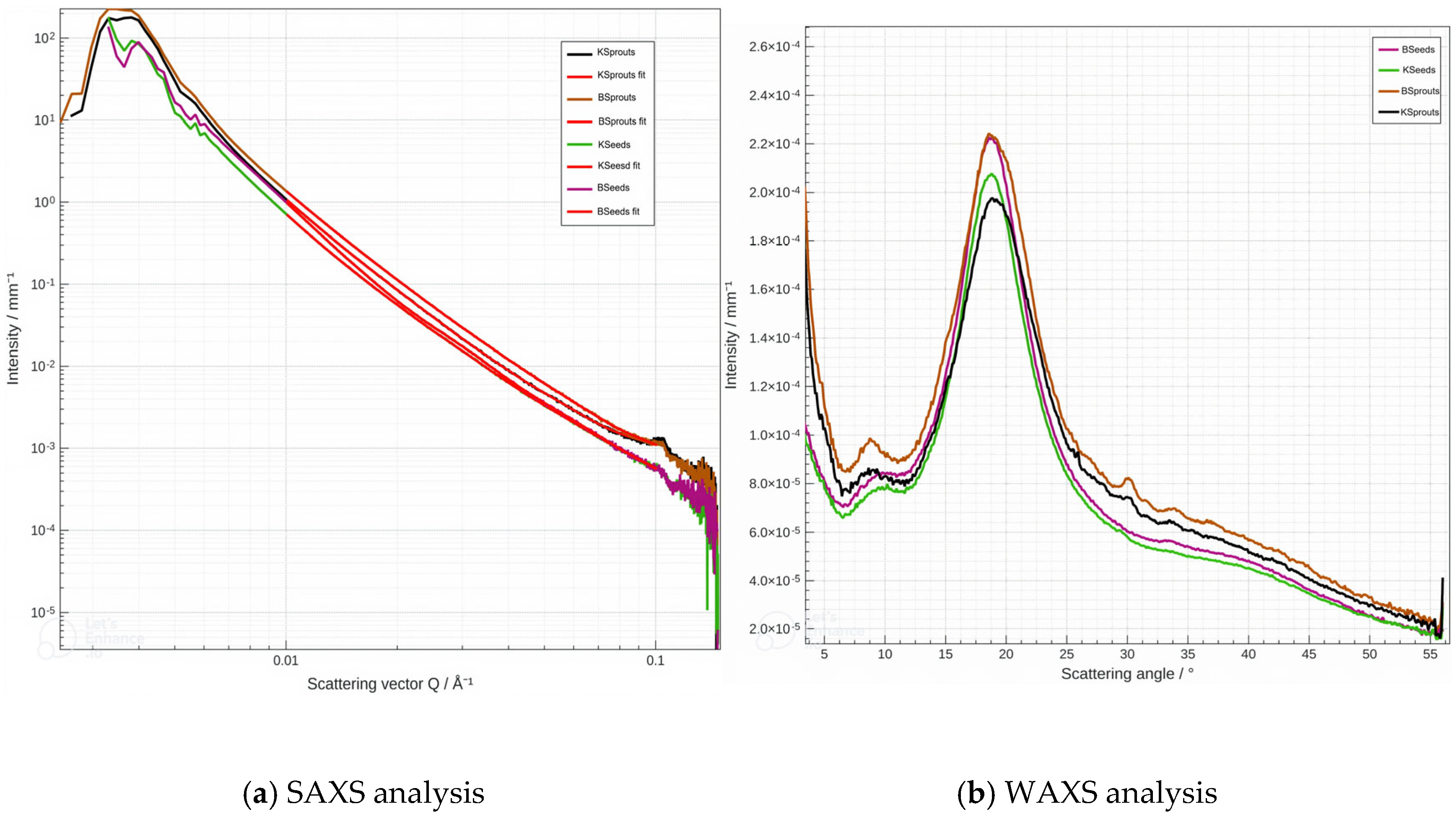

3.5.2. Small-Wide Angle X-Ray Scattering (SAXS/WAXS)

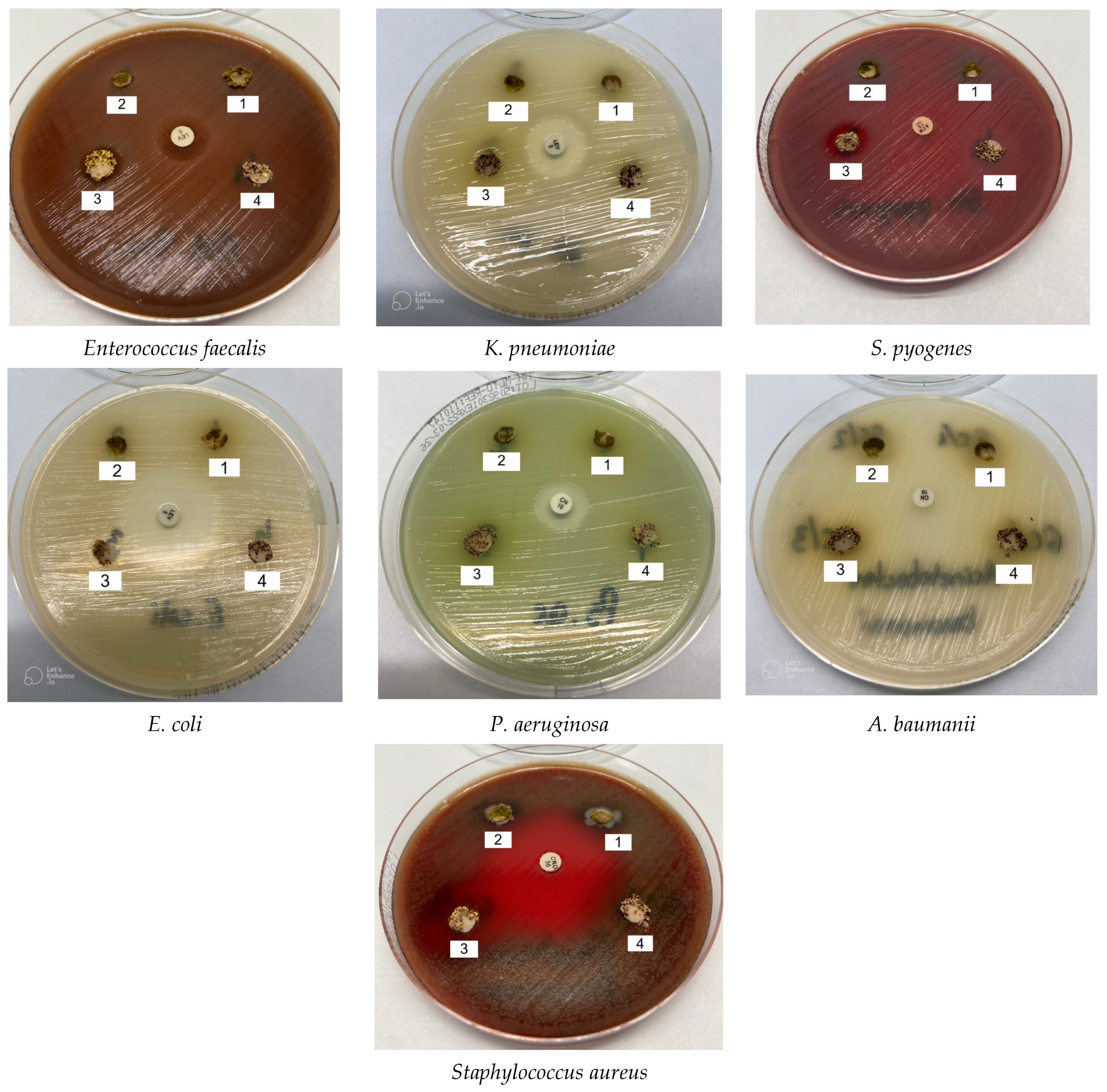

3.6. Antibacterial Activity of Kale and Broccoli Seed and Sprout Powders

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Šamec, D.; Urlić, B.; Salopek-Sondi, B. Kale (Brassica oleracea var. acephala) as a superfood: Review of the scientific evidence behind the statement. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2019, 59, 2411–2422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mancini, L.; Farooq, M.; Apa, C.A.; Bleve, G.; Celano, G.; Calabrese, F.M.; De Angelis, M. Type II sourdough fermentation as a strategy to improve the nutritional profile of kale-enriched wheat flour wheat flour and semolina flatbreads. Food Biosci. 2025, 71, 107115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, M.; Song, C.; Su, S.; Li, J.; Hu, Z.; Lin, S.; Zou, H.; Tang, Z.; Yan, X. Quantification and Diversity Analyses of Glucosinolates in 191 Broccoli Genotypes Highlight Valuable Genetic Resources for Molecular Breeding. Agronomy 2023, 13, 2928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, H.; Xu, Z.; Li, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, W.; Deng, J. A comparative metabolomics analysis of phytochemcials and antioxidant activity between broccoli floret and by-products (leaves and stalks). Food Chem. 2024, 443, 138517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; Yan, M.; Song, C.; Sato, M.; Su, S.; Lin, S.; Li, J.; Zou, H.; Tang, Z.; Hirai, M.Y.; et al. An Integrated Approach for the Comprehensive Characterization of Metabolites in Broccoli (Brassica oleracea var. Italica) by Liquid Chromatography High-Resolution Tandem Mass Spectrometry. Plants 2025, 14, 3223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebert, A.W. Sprouts and Microgreens—Novel Food Sources for Healthy Diets. Plants 2022, 11, 571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, H.; Debs, E.; Koubaa, M.; Alrayess, Z.; Maroun, R.G.; Louka, N. Sprouts use as functional foods. Optimization of germination of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.), alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.), and radish (Raphanus sativus L.) seeds based on their nutritional content evolution. Foods 2022, 11, 1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobrowolska-Iwanek, J.; Zagrodzki, P.; Galanty, A.; Fołta, M.; Kryczyk-Kozioł, J.; Szlósarczyk, M.; Rubio, P.S.; Saraiva de Carvalho, I.; Paśko, P. Determination of Essential Minerals and Trace Elements in Edible Sprouts from Different Botanical Families—Application of Chemometric Analysis. Foods 2022, 11, 371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kathuria, D.; Hamid; Chavan, P.; Jaiswal, A.K.; Thakur, A.; Dhiman, A.K. A comprehensive review on sprouted seeds bioactives, the impact of novel processing techniques and health benefits. Food Rev. Int. 2024, 40, 370–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majzoobi, M.; Wang, Z.; Teimouri, S.; Pematilleke, N.; Brennan, C.S.; Farahnaky, A. Unlocking the potential of sprouted cereals, pseudocereals, and pulses in combating malnutrition. Foods 2023, 12, 3901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waliat, S.; Arshad, M.S.; Hanif, H.; Ejaz, A.; Khalid, W.; Kauser, S.; Al-Farga, A. A review on bioactive compounds in sprouts: Extraction techniques, food application and health functionality. Int. J. Food Prop. 2023, 26, 647–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidal, J.D.; Beres, C.; Brito, F.O.; Zago, L.; Miyahira, R.F. Unlocking the functional potential of sprouts: A scientific exploration on simulated gastrointestinal digestion and colonic fermentation. J. Funct. Foods 2024, 117, 106235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syed, R.U.; Moni, S.S.; Break, M.K.B.; Khojali, W.M.; Jafar, M.; Alshammari, M.D.; Abdelsalam, K.; Taymour, S.; Alreshidi, K.S.M.; Elhassan Taha, M.M. Broccoli: A multi-faceted vegetable for health: An in-depth review of its nutritional attributes, antimicrobial abilities, and anti-inflammatory properties. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baralić, K.; Živanović, J.; Marić, Đ.; Bozic, D.; Grahovac, L.; Antonijević Miljaković, E.; Ćurčić, M.; Buha Djordjevic, A.; Bulat, Z.; Antonijević, B. Sulforaphane—A compound with potential health benefits for disease prevention and treatment: Insights from pharmacological and toxicological experimental studies. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Steenwijk, H.P.; Vinken, A.; van Osch, F.H.; Peppelenbos, H.; Troost, F.J.; Bast, A.; Semen, K.O.; de Boer, A. Sulforaphane as a potential modifier of calorie-induced inflammation: A double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover trial. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1245355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanaka, A.; Ohmori, T.; Ochi, M.; Suzuki, H. Dietary intake of sulforaphane-rich broccoli sprouts decreases fecal calprotectin levels in patients with ulcerative colitis. Funct. Foods Health Dis. 2024, 14, 688–703. [Google Scholar]

- Fahey, J.W.; Liu, H.; Batt, H.; Panjwani, A.A.; Tsuji, P. Sulforaphane and Brain Health: From Pathways of Action to Effects on Specific Disorders. Nutrients 2025, 17, 1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Li, C.; Lee, A. Sprouted grains as a source of bioactive compounds for modulating insulin resistance. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 8574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Kai, Y.; Huang, D.; Liu, S.Q.; Lu, Y. A Comprehensive Review of Germination Impact on Moringa Seeds and Sprouts: Physiological and Biochemical Changes, Bioactive Compounds, Health Benefits, and Food Applications. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2025, 24, e70296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, H.; Woods, P.; Green, B.D.; Nugent, A.P. Can sprouting reduce phytate and improve the nutritional composition and nutrient bioaccessibility in cereals and legumes? Nutr. Bull. 2022, 47, 138–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maldonado-Alvarado, P.; Pavón-Vargas, D.J.; Abarca-Robles, J.; Valencia-Chamorro, S.; Haros, C.M. Effect of germination on the nutritional properties, phytic acid content, and phytase activity of quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa Willd). Foods 2023, 12, 389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakumanu, A.; Gorrepati, R.; Kakumanu, B. Nutrient limitations of the edible sprouts: A review. Int. J. Biosci. 2023, 22, 133–148. Available online: http://www.innspub.net (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Egli, I.; Davidsson, L.; Juillerat, M.; Barclay, D.; Hurrell, R. The influence of soaking and germination on the phytase activity and phytic acid content of grains and seeds potentially useful for complementary feedin. J. Food Sci. 2002, 67, 3484–3488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, M.V.; Batabyal, A.N. Broccoli seed germination enhances their nutritional composition, antioxidant, anticancer, and antimicrobial activities, and in vitro nutrient digestibility. Indian J. Nat. Prod. Resour. (IJNPR) 2025, 16, 102–112. [Google Scholar]

- Khattak, A.B.; Zeb, A.; Bibi, N.; Khalil, S.A.; Khattak, M.S. Influence of germination techniques on phytic acid and polyphenols content of chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) sprouts. Food Chem. 2007, 104, 1074–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dragomir, C.; Misca, C.D.; Dossa, S.; Jianu, C.; Radulov, I.; Negrea, M.; Paven, L.; Alexa, E. Chemical Composition, Antibacterial Activity, and Food Application of Sprouts from Fabaceae and Brassicaceae Species. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 1896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dragomir, C.; Dossa, S.; Jianu, C.; Cocan, I.; Radulov, I.; Berbecea, A.; Radu, F.; Alexa, E. Composite Flours Based on Black Lentil Seeds and Sprouts with Nutritional, Phytochemical and Rheological Impact on Bakery/Pastry Products. Foods 2025, 14, 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ISO 2171:2023; Cereals, Pulses and By-Products—Determination of Ash Yield by Incineration. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2007.

- Latimer, G.W., Jr. Official Methods of Analysis of AOAC International; AOAC International: Rockville, MD, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Dossa, S.; Negrea, M.; Cocan, I.; Berbecea, A.; Obistioiu, D.; Dragomir, C.; Alexa, E.; Rivis, A. Nutritional, physico-chemical, phytochemical, and rheological characteristics of composite flour substituted by baobab pulp flour (Adansonia digitata L.) for bread making. Foods 2023, 12, 2697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poșta, D.S.; Radulov, I.; Cocan, I.; Berbecea, A.A.; Alexa, E.; Hotea, I.; Iordănescu, O.A.; Băla, M.; Cântar, I.C.; Rózsa, S. Hazelnuts (Corylus avellana L.) from spontaneous flora of the west part of Romania: A source of nutrients for locals. Agronomy 2022, 12, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Megazyme/Neogen, Lansing, MI, USA. Phytic Acid Protocol. Available online: https://prod-docs.megazyme.com/documents/Assay_Protocol/K-PHYT_DATA.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- McKie, V.A.; MccleAry, B.V. A novel and rapid colorimetric method for measuring total phosphorus and phytic acid in foods and animal feeds. J. AOAC Int. 2016, 99, 738–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dossa, S.; Neagu, C.; Lalescu, D.; Negrea, M.; Stoin, D.; Jianu, C.; Berbecea, A.; Cseh, L.; Rivis, A.; Suba, M.; et al. Evaluation of the Nutritional, Rheological, Functional, and Sensory Properties of Cookies Enriched with Taro (Colocasia esculenta) Flour as a Partial Substitute for Wheat Flour. Foods 2025, 14, 3526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fluerasu, D.; Neagu, C.; Dossa, S.; Negrea, M.; Jianu, C.; Berbecea, A.; Stoin, D.; Lalescu, D.; Brezovan, D.; Cseh, L.; et al. The Use of Whey Powder to Improve Bread Quality: A Sustainable Solution for Utilizing Dairy By-Products. Foods 2025, 14, 2911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. Routine and Extended Internal Quality Control for MIC Determination and Disk Diffusion as Recommended by EUCAST, 15th ed.; The European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing: Växjö, Sweden, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Jianu, C.; Mişcă, C.; Muntean, S.G.; Gruia, A.T. Composition, antioxidant and antimicrobial activity of the essential oil of Achillea collina Becker growing wild in western Romania. Hem. Ind. 2015, 69, 381–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowitcharoen, L.; Phornvillay, S.; Lekkham, P.; Pongprasert, N.; Srilaong, V. Bioactive Composition and Nutritional Profile of Microgreens Cultivated in Thailand. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 7981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, C.F. Broccoli microgreens: A mineral-rich crop that can diversify food systems. Front. Nutr. 2017, 4, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhaswant, M.; Shanmugam, D.K.; Miyazawa, T.; Abe, C.; Miyazawa, T. Microgreens—A comprehensive review of bioactive molecules and health benefits. Molecules 2023, 28, 867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatt, P.; Sharma, S.; Grover, K.; Sharma, S.; Dharni, K.; Dhatt, A.S. Optimization of nutritional composition, bioactive compounds and antioxidant activity in broccoli (Brassica oleracea) microgreen sprinkler using alternate drying techniques. Asian J. Dairy Food Res. 2023, 1955, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dziki, D.; Habza-Kowalska, E.; Gawlik-Dziki, U.; Miś, A.; Różyło, R.; Krzysiak, Z.; Hassoon, W.H. Drying Kinetics, Grinding Characteristics, and Physicochemical Properties of Broccoli Sprouts. Processes 2020, 8, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baenas, N.; González-Trujano, M.E.; Guadarrama-Enríquez, O.; Pellicer, F.; García-Viguera, C.; Moreno, D.A. Broccoli sprouts in analgesia–preclinical in vivo studies. Food Funct. 2017, 8, 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pająk, P.; Socha, R.; Gałkowska, D.; Rożnowski, J.; Fortuna, T. Phenolic profile and antioxidant activity in selected seeds and sprouts. Food Chem. 2014, 143, 300–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baenas, N.; García-Viguera, C.; Moreno, D.A. Biotic elicitors effectively increase the glucosinolates content in Brassicaceae sprouts. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2014, 62, 1881–1889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Balibrea, S.; Moreno, D.A.; García-Viguera, C. Improving the phytochemical composition of broccoli sprouts by elicitation. Food Chem. 2011, 129, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Sánchez, A.; Gil-Izquierdo, A.; Gil, M.I.; Ferreres, F. A comparative study of flavonoid compounds, vitamin C, and antioxidant properties of baby leaf Brassicaceae species. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2008, 56, 2330–2340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.-H.; Dhungana, S.K.; Kim, I.-D.; Adhikari, A.; Kim, J.-H. Effect of Illite Treatment on Quality Characteristics and Antioxidant Activity of Broccoli (Brassica oleracea L. var. italica) Sprouts. Molecules 2024, 29, 4347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.; Jiang, H.; Li, Y.; He, R.; Liu, K.; Chen, Y.; He, X.; Liu, X.; Liu, H. Growth, Phytochemicals, and Antioxidant Activity of Kale Grown under Different Nutrient-Solution Depths in Hydroponic. Horticulturae 2023, 9, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen-Forbes, C.; Armstrong, E.; Moses, A.; Fahlman, R.; Koosha, H.; Yager, J.Y. Broccoli, Kale, and Radish Sprouts: Key Phytochemical Constituents and DPPH Free Radical Scavenging Activity. Molecules 2023, 28, 4266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okaiyeto, S.A.; Liu, D.; Zhang, C.; Bai, J.-W.; Chen, C.; Sharma, P.; Venugopal, A.P.; Asiamah, E.; Ketemepi, H.K.; Imadegbor, F.A.; et al. Anti-nutrients of plant-based food: Physicochemical properties, effects on health and degradation techniques—A comprehensive review. J. Future Foods 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galieni, A.; Falcinelli, B.; Stagnari, F.; Datti, A.; Benincasa, P. Sprouts and Microgreens: Trends, Opportunities, and Horizons for Novel Research. Agronomy 2020, 10, 1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillen, M.D.; Cabo, N. Characterization of edible oils and lard by Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy. Relationships between composition and frequency of concrete bands in the fingerprint region. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 1997, 74, 1281–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlachos, N.; Skopelitis, Y.; Psaroudaki, M.; Konstantinidou, V.; Chatzilazarou, A.; Tegou, E. Applications of Fourier transform-infrared spectroscopy to edible oils. Anal. Chim. Acta 2006, 573, 459–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso-Simón, A.; García-Angulo, P.; Mélida, H.; Encina, A.; Álvarez, J.M.; Acebes, J.L. The use of FTIR spectroscopy to monitor modifications in plant cell wall architecture caused by cellulose biosynthesis inhibitors. Plant Signal. Behav. 2011, 6, 1104–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van de Voort, F.; Ismail, A.; Sedman, J. A rapid, automated method for the determination of cis and trans content of fats and oils by Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 1995, 72, 873–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickramasinghe, M.A.; Nadeeshani, H.; Sewwandi, S.M.; Rathnayake, I.; Kananke, T.C.; Liyanage, R. Comparison of nutritional composition, bioactivities, and FTIR-ATR microstructural properties of commercially grown four mushroom species in Sri Lanka; Agaricus bisporus, Pleurotus ostreatus, Calocybe sp. (MK-white), Ganoderma lucidum. Food Prod. Process. Nutr. 2023, 5, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kizil, R.; Irudayaraj, J.; Seetharaman, K. Characterization of irradiated starches by using FT-Raman and FTIR spectroscopy. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2002, 50, 3912–3918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barth, A. Infrared spectroscopy of proteins. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Bioenerg. 2007, 1767, 1073–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atudorei, D.; Stroe, S.-G.; Codină, G.G. Impact of germination on the microstructural and physicochemical properties of different legume types. Plants 2021, 10, 592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, E.P. Small-angle X-Ray and neutron scattering in food colloids. Curr. Opin. Colloid. Interface Sci. 2019, 42, 55–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Li, X.; Chen, R.; Liu, F.; Wei, S. Recent advances in structural characterization of biomacromolecules in foods via small-angle X-ray scattering. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 1039762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertoft, E. Understanding starch structure: Recent progress. Agronomy 2017, 7, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, P.V.; Maeda, T.; Yamamoto, S.; Morita, N. Effects of germination on nutritional composition of waxy wheat. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2012, 92, 667–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vale, A.; Santos, J.; Melia, N.; Peixoto, V.; Brito, N.; Oliveira, M.B.P. Phytochemical composition and antimicrobial properties of four varieties of Brassica oleracea sprouts. Food Control 2015, 55, 248–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, J.-K.; Kim, J.-R.; Ahn, Y.-J.; Shibamoto, T. Analysis and anti-Helicobacter activity of sulforaphane and related compounds present in broccoli (Brassica oleracea L.) sprouts. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2010, 58, 6672–6677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le, T.N.; Chiu, C.-H.; Hsieh, P.-C. Bioactive compounds and bioactivities of Brassica oleracea L. var. italica sprouts and microgreens: An updated overview from a nutraceutical perspective. Plants 2020, 9, 946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pacheco-Cano, R.; Salcedo-Hernández, R.; López-Meza, J.; Bideshi, D.; Barboza-Corona, J. Antimicrobial activity of broccoli (Brassica oleracea var. italica) cultivar Avenger against pathogenic bacteria, phytopathogenic filamentous fungi and yeast. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2018, 124, 126–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamokou, J.D.D.; Mbaveng, A.; Kuete, V. Antimicrobial activities of African medicinal spices and vegetables. In Medicinal Spices and Vegetables from Africa; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017; pp. 207–237. [Google Scholar]

| Samples | Scientific Name | Samples Code |

|---|---|---|

| Broccoli seeds | (Brassica oleracea var. italica) | BSeeds |

| Kale seeds | (Brassica oleracea var. acephala) | KSeeds |

| Broccoli sprouts | (Brassica oleracea var. italica) | BSprouts |

| Kale sprouts | (Brassica oleracea var. acephala) | KSprouts |

| Parameters | Methods | References |

|---|---|---|

| Protein content (%) | Protein content was calculated based on the nitrogen content obtained by the Kjeldahl method, using a conversion factor of 6.5. | [27] |

| Moisture (%) | Moisture content was measured by drying the samples at 105 °C until a constant mass was obtained, then the results were expressed as a percentage of the total weight of the sample. | [27] |

| Ash (%) | Ash content was determined by incinerating the samples in a muffle furnace at 650 °C, until complete removal of organic materials. | [28] |

| Fat (%) | Fat content was determined using petroleum ether solvent with Soxhlet equipment (Velp Scientifica SER 148 Solvent Extractor, Via Stazione 16, USMATE, Italy). | [29] |

| Carbohydrates (g/100 g) | The carbohydrate content was calculated as fraction remaining in the sample after taking into account moisture, ash, fat and protein using the formula: carbohydrate (%) = 100 − (moisture + ash + fat + protein) | [27] |

| Energy value (kcal) | Energy value was calculated according to the formula: kcal = (Proteins × 4) + (Carbohydrates × 4) + (Fat × 9) | [27] |

| Bacterial Strain | Family | Order | Antibiotic (Positive Control) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gram-negative | |||

| Escherichia coli (E. coli) | Fam. Enterobacteriaceae, | Ord. Enterobacterales | levofloxacin |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae (K. pneumoniae) | Fam. Enterobacteriaceae | Ord. Enterobacterales | levofloxacin |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa (P. aeruginosa) | Fam. Pseumonadaceae | Ord. Pseudomonadales | gentamicin |

| Acinetobacter baumanii (A. baumanii) | Fam. Moraxellaceae | Ord. Pseudomonadales | gentamicin |

| Gram-positive | |||

| Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus) | Fam. Staphylococcaceae | Ord. Bacillales | linezolid |

| Enterococcus faecalis (E. faecalis) | Fam. Enterococcaceae | Ord. Lactobacillales | levofloxacin |

| Streptococcus pyogenes (S. pyogenes) | Fam. Streptococcaceae | Ord. Lactobacillales | azitromicyn |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae (S. pneumoniae) | Fam. Streptococcaceae | Ord. Lactobacillales | ceftriaxone |

| Samples | Nutritional Characteristics | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moisture | Ash | Proteins | Lipids | Carbohydrates | Energy Values | |

| (%) | (%) | (%) | (%) | (g/100 g) | (Kcal/100 g) | |

| seed powders | ||||||

| BSeeds | 2.58 ± 0.82 a | 0.55 ± 0.27 a | 10.32 ± 0.30 a | 30.91 ± 0.04 a | 55.64 ± 0.43 a | 542.07 ± 3.21 a |

| KSeeds | 2.76 ± 0.11 b | 1.43 ± 0.12 b | 11.79 ± 0.70 b | 30.90 ± 0.29 a | 53.12 ± 0.76 b | 537.72 ± 1.10 b |

| sprout powders | ||||||

| BSprouts | 1.83 ± 0.41 c | 2.41 ± 0.15 c | 30.33 ± 0.66 c | 2.65 ± 0.22 b | 62.77 ± 0.90 c | 396.27 ± 2.20 c |

| KSprouts | 2.30 ± 0.37 d | 0.93 ± 0.22 d | 30.21 ± 0.17 c | 3.45 ± 0.19 c | 63.12 ± 0.42 c | 404.35 ± 2.33 d |

| Samples | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Epicatechin | Caffeic Acid | Beta-Rezorcilic Acid | P-Coumaric Acid | Ferulic Acid | Rosmarinic Acid | Resveratrol | Quercetin | |

| Composite powder | ||||||||

| BSprouts | ND | 7.16 ± 1.2 a | ND * | 16.87 ± 0.6 a | 25.40 ± 0.5 a | 200.87 ± 1.3 a | ND | 12.94 ± 1.9 a |

| KSprouts | ND | 75.33 ± 0.7 b | ND | ND | 23.09 ± 1.5 a | 17.68 ± 2.6 b | 7.46 ± 2.3 a | 9.40 ± 1.2 b |

| BSeeds | ND | 3.45 ± 1.3 c | ND | 9.14 ± 0.2 b | 35.25 ± 0.5 b | ND | ND | 9.86 ± 1.5 b |

| KSeeds | ND | 35.34 ± 0.8 d | ND | ND | 76.02 ± 0.7 c | ND | ND | 8.31 ± 2.6 b |

| Samples | Elements | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cu | Ni | Zn | Fe | Mn | Ca | Mg | K | Na | |

| seed powders | |||||||||

| BSeeds | 4.27 ± 0.02 a | 0.74 ± 0.06 a | 39.15 ± 0.29 a | 62.86 ± 0.15 a | 24.58 ± 0.23 a | 391.15 ± 8.90 a | 60.14 ± 0.23 a | 59.13 ± 0.09 a | 26.01 ± 0.05 a |

| KSeeds | 3.26 ± 0.06 b | 3.72 ± 0.34 b | 48.24 ± 0.57 b | 81.20 ± 1.08 b | 13.61 ± 0.24 b | 348.37 ± 13.39 b | 60.16 ± 0.04 a | 58.58 ± 0.65 a | 30.52 ± 0.16 b |

| Sprout powders | |||||||||

| BSprouts | 7.30 ± 0.13 c | 1.03 ± 0.06 c | 70.37 ± 1.32 c | 65.93 ± 0.46 c | 34.26 ± 0.14 c | 413.93 ± 8.39 c | 62.59. ± 0.16 a | 61.21 ± 0.17 a | 39.20 ± 0.18 c |

| KSprouts | 3.86 ± 0.09 ab | 2.03 ± 0.06 d | 54.72 ± 0.61 d | 47.95 ± 0.74 d | 10.42 ± 0.07 b | 329.06 ± 0.13 b | 61.21 ± 0.27 a | 103.96 ± 0.33 b | 37.88 ± 0.20 d |

| Sample | Median of the Distribution, nm | Surface Equivalent Mean Size, nm | Goodness of Fit |

|---|---|---|---|

| BSeeds | 819.84 | 29.69 | 1.27 |

| KSeeds | 841.82 | 38.86 | 1.04 |

| BSprouts | 849.29 | 43.08 | 1.00 |

| KSprouts | 865.21 | 53.03 | 1.01 |

| The Tested Microorganism | The Halo Diameter of the Antibiotic Used as a Control | The Halo Diameter of 2 µL Suspension Dilution 10−1 KSprouts | The Halo Diameter of 2 µL Suspension Dilution 10−1 BSprouts | The Halo Diameter of 2 µL Suspension Dilution 10−1 KSeeds | The Halo Diameter of 2 µL Suspension Dilution 10−1 BSeeds |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli | Levofloxacin 30 mm | 6 mm | 6 mm | 12 mm | 6 mm |

| K. pneumoniae | Levofloxacin 17 mm | 6 mm | 6 mm | 6 mm | 6 mm |

| P. aeruginosa | Gentamicin 15 mm | 6 mm | 6 mm | 6 mm | 6 mm |

| A. baumanii | Gentamicin 6 mm | 6 mm | 6 mm | 6 mm | 6 mm |

| S. aureus | Linezolid 31 mm | 6 mm | 6 mm | 16 mm | 6 mm |

| E. faecalis | Levofloxacin 16 mm | 6 mm | 6 mm | 14 mm | 12 mm |

| S. pyogenes | Azitromicyn 6 mm | 6 mm | 6 mm | 14 mm | 12 mm |

| S. pneumoniae | Ceftriaxone 43 mm | 6 mm | 6 mm | 20 mm | 6 mm |

| MIC µg/mL | KSprouts µg/mL | BSprouts µg/mL | KSeeds µg/mL | BSeeds µg/mL | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 200 | 400 | 600 | 1000 | 200 | 400 | 600 | 1000 | 200 | 400 | 600 | 1000 | 200 | 400 | 600 | 1000 | ||

| E. coli | Levofloxacin 0.06 | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | IS | R | R | R | R |

| K. pneumoniae | Levofloxacin 0.06 | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R |

| P. aeruginosa | Gentamicin 1 | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R |

| A. baumanii | Gentamicin 1 | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R |

| S. aureus | Linezolid 2 | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | S | R | R | R | S |

| E. faecalis | Levofloxacin 1 | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | IS | R | R | R | IS |

| S. pyogenes | Azitromicyn 1 | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | IS | R | R | R | IS |

| S. pneumoniae | Ceftriaxone 0.1 | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | S | R | R | R | R |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Dragomir, C.; Misca, C.D.; Dossa, S.; Stoin, D.; Velciov, A.; Jianu, C.; Radulov, I.; Suba, M.; Ianasi, C.; Alexa, E. Germination as a Sustainable Green Pre-Treatment for the Recovery and Enhancement of High-Value Compounds in Broccoli and Kale. Molecules 2026, 31, 350. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31020350

Dragomir C, Misca CD, Dossa S, Stoin D, Velciov A, Jianu C, Radulov I, Suba M, Ianasi C, Alexa E. Germination as a Sustainable Green Pre-Treatment for the Recovery and Enhancement of High-Value Compounds in Broccoli and Kale. Molecules. 2026; 31(2):350. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31020350

Chicago/Turabian StyleDragomir, Christine (Neagu), Corina Dana Misca, Sylvestre Dossa, Daniela Stoin, Ariana Velciov, Călin Jianu, Isidora Radulov, Mariana Suba, Catalin Ianasi, and Ersilia Alexa. 2026. "Germination as a Sustainable Green Pre-Treatment for the Recovery and Enhancement of High-Value Compounds in Broccoli and Kale" Molecules 31, no. 2: 350. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31020350

APA StyleDragomir, C., Misca, C. D., Dossa, S., Stoin, D., Velciov, A., Jianu, C., Radulov, I., Suba, M., Ianasi, C., & Alexa, E. (2026). Germination as a Sustainable Green Pre-Treatment for the Recovery and Enhancement of High-Value Compounds in Broccoli and Kale. Molecules, 31(2), 350. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31020350