2. Results and Discussion

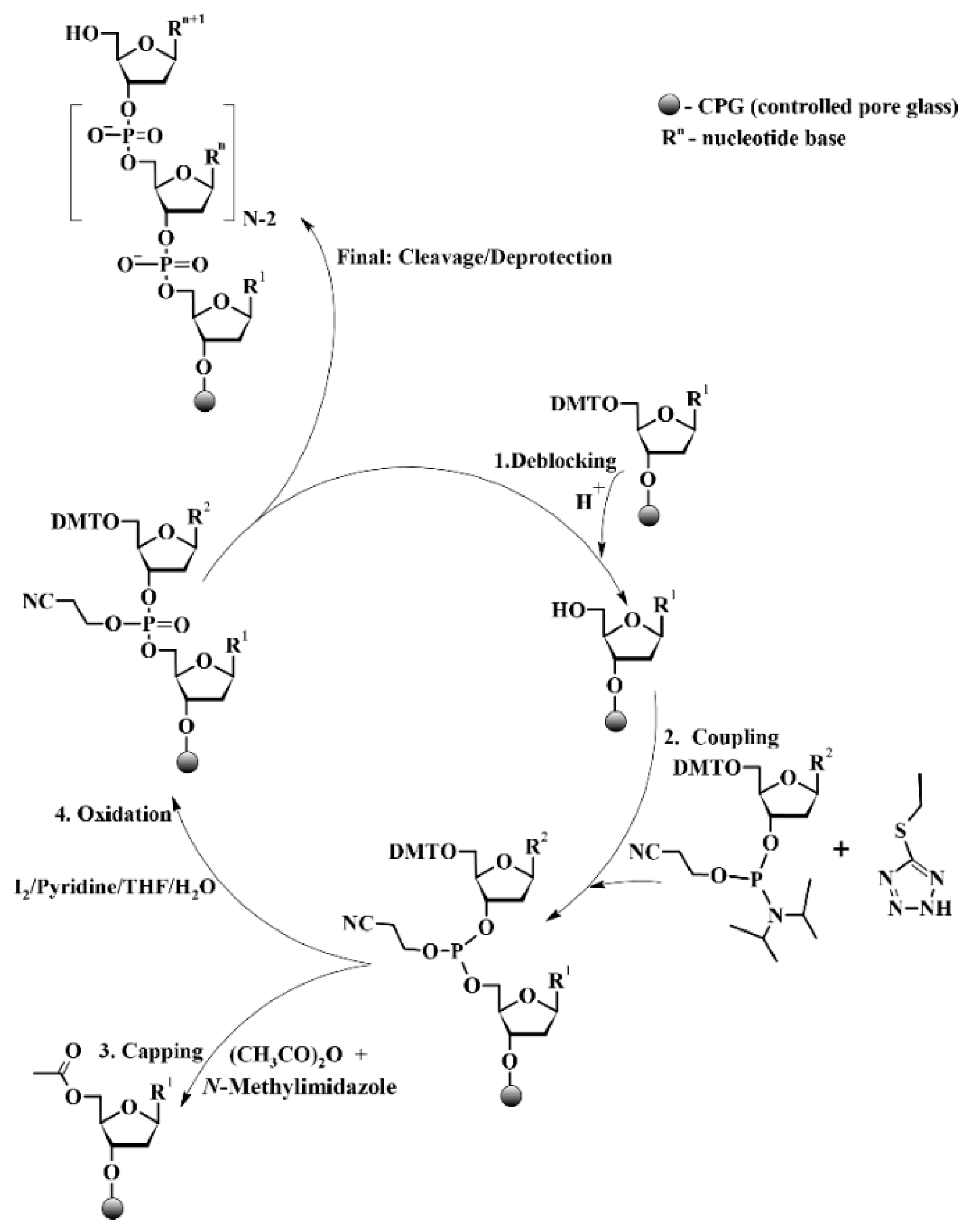

In our laboratory, oligonucleotides were synthesized using the solid-phase phosphoramidite method (see

Scheme 1), developed by M. H. Caruthers [

14].

We carried out the synthesis on a 96-well DNA synthesizer ASM-2000 (Biosset, Russia) according to the following protocol, see

Table 1.

Dry reagents and anhydrous solvents were used in the synthesis. For clarity, propionic anhydride (Pr

2O) was employed in capping reagent A (CapA) in our laboratory instead of the commonly used acetic anhydride (Ac

2O), as the latter is subject to regulatory controls in the Russian Federation. In our experience, Pr

2O in CapA is as effective as Ac

2O for this application. After the synthesis, CPG-bound protected oligonucleotides were treated with AMA reagent (see

Table 1). The resulting deprotected oligonucleotides were then precipitated in ethanol with 0.3 M NaCl. The dried precipitates were dissolved in water and used directly, without further purification, for the assembly of long DNA sequences via polymerase cycling assembly (PCA) [

15].

Synthesis accuracy was assessed via Sanger sequencing, using the T5 exonuclease gene as a model (see

Supplementary File S1.Fasta S1). The gene sequence was divided into partially overlapping oligonucleotides using GeneCut software (

http://genecut.unipro.ru/) (access date: 25 November 2024) (see

Supplementary File S1.Table S1) [

16]. These oligonucleotides were synthesized as described above and used for PCA. The assembled T5 exonuclease gene was amplified and cloned into the

pUC19 vector. Recombinant vectors were transformed into

E. coli (NovaBlue) cells, which were then plated on antibiotic-containing agar. Ten colonies containing inserts of the expected length were selected via colony PCR screening and subjected to Sanger sequencing. To account for potential variability during assembly, cloning, or host–cell variability, the entire process was independently repeated three times. A Kruskal–Wallis test [

17] comparing error distributions across the three experiments revealed no statistically significant differences (

p-value = 0.93). Detailed error types and statistical analyses are provided in

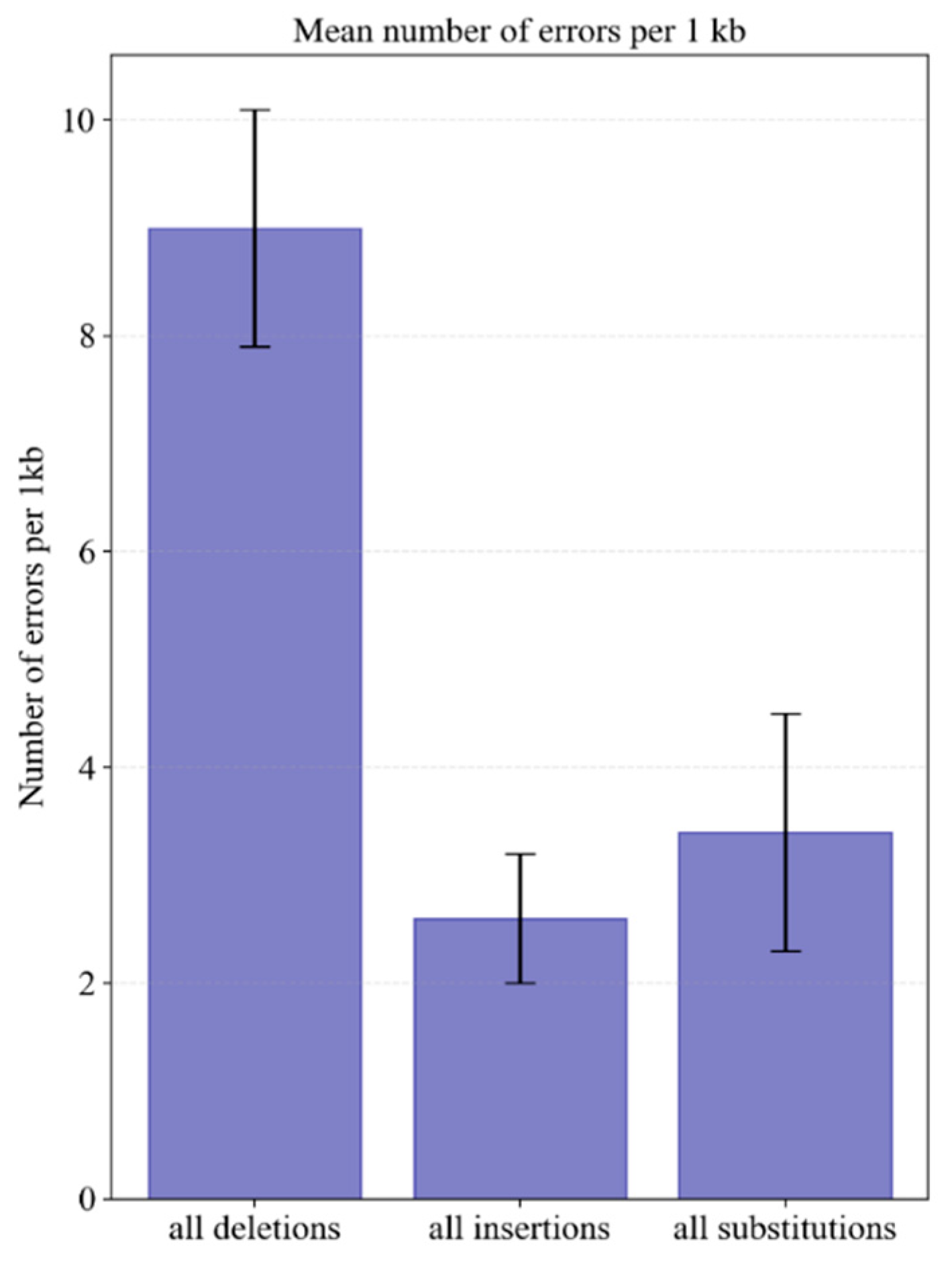

Supplementary File S2. Analysis of Sanger sequencing data revealed that deletions were the most frequent error (9 ± 1.1 per kb), followed by substitutions (3.4 ± 1.1 per kb) and insertions (2.4 ± 0.6 per kb) (

Figure 1,

Supplementary File S2).

The high frequency of deletions, along with the presence of insertions, can be attributed to the use of crude oligonucleotide mixtures containing N-1 truncated failure sequences. Nevertheless, despite this error rate, sequencing only nine clones is statistically sufficient to obtain a correct 1 kb fragment with 90% probability (see

Supplementary File S2).

After deletions, base substitutions were the most frequent errors (

Figure 1), with G/A and C/T being the predominant types (see

Figure 2).

The prevalence of G/A and C/T substitutions may result from: (i) mechanical defects in the DNA synthesizer leading to incorrect phosphoramidite dispensing; (ii) polymerase-induced errors during PCA or gene amplification; or (iii) side reactions involving nucleobases during oligonucleotide synthesis or post-synthetic processing. We excluded accidental cross-contamination with dA or dT phosphoramidites as such an event would produce comparable levels of T/A, C/A, A/T, and G/T substitutions, which were not observed. Indeed, in the assembly of the T5 exonuclease gene, we did not detect any T/A, C/A, or G/T substitutions at all (

Figure 2,

Supplementary File S2). We also ruled out polymerase-related errors during PCA and amplification as the source of G/A and C/T substitutions. In our experiments, we used high-fidelity Phusion polymerase [

18].

Therefore, we hypothesize that G/A and C/T substitutions arise from the chemical modification of cytosine and/or guanine bases during oligonucleotide synthesis or post-synthetic processing. These modified bases are misread by the polymerase during PCA, leading to the observed G/A and C/T substitutions in the final gene construct.

A similar predominance of G/A and C/T substitutions over other substitution types was observed in the assembly of the interleukin-2 (IL-2) gene and the gene encoding the Sso7d protein (see

Supplementary File S2). This consistency raises the question of whether such a distribution is general or specifically associated with our synthesis protocol (

Table 1).

There is a notable lack of studies providing comprehensive statistical data on the accumulation of specific error types in synthetic DNA. Such data are only occasionally reported in studies focused on error correction in assembled gene constructs. For instance, several reports indicate that, prior to correction, the majority of the mismatches in the original constructs were G:T/A:C mismatches [

19,

20,

21]. However, this information remains difficult to interpret without precise knowledge of the specific synthesis protocols used for the constituent oligonucleotides.

In 2021, S. Filges et al. published a study evaluating errors in chemically synthesized oligonucleotides using a digital sequencing approach with unique molecular identifiers [

13]. By analyzing oligonucleotides from various suppliers, the authors found that deletions were the predominant error type across nearly all batches. Substitutions were also reported, although a detailed breakdown of substitution types was not provided. The average substitution frequency across all oligonucleotide types was 0.025%, which was seven times lower than the observed deletion rate.

Later, in 2022, Y. Masaki et al. reported a quantitative assessment of errors in synthetic oligonucleotides using NGS [

22]. They demonstrated that G/A substitutions accumulate depending on the capping conditions. The authors hypothesized that these substitutions result from the modification of the

O6-position of guanine residues by components of the capping mixture, leading to the formation of 2,6-diaminopurine (DAP). This hypothesis was indirectly supported by experiments in which standard deoxyguanosine phosphoramidites were replaced with analogs bearing modified bases, such as 7-deazaguanine and 8-aza-7-deazaguanine. The use of these modified phosphoramidites reduced the G/A substitution frequency by 10-fold for 7-deazaguanine and by 50-fold for 8-aza-7-deazaguanine, compared to standard guanine.

Several research groups have previously reported side reactions involving the guanine base during solid-phase phosphoramidite synthesis [

23,

24]. Specifically, Rodriguez et al. investigated the formation of side products under excessive capping conditions (86 equivalents of Ac

2O over 15 min for cycle 1, and 17.2 equivalents over 1.5 min for cycles 2 through the penultimate cycle) [

23]. Oligonucleotides synthesized under these conditions contained 9.2% of an impurity with an additional mass of +41 amu, identified via reverse-phase high-performance liquid chromatography–electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (RP-HPLC-ESI-MS). This +41 amu impurity was absent when the capping step was omitted. Based on these findings, the authors concluded that the additional mass resulted from the formation of an

N2-acetyl-2,6-diaminopurine derivative induced by the excessive capping (prolonged reaction time and high reagent equivalents).

Earlier, Eadie and Davidson reported the presence of a fluorescent impurity in deprotected oligonucleotides synthesized using acetic anhydride, 4-dimethylaminopyridine (DMAP), and lutidine as capping reagents [

24]. They demonstrated that this modification occurs at guanine residues, generating an impurity with an absorption spectrum in the 330–400 nm range. This fluorescent intermediate was shown to partially convert in ammonium hydroxide solution to a 2,6-diaminopurine deoxyribonucleoside. Notably, the authors also observed the accumulation of this impurity under conditions where only DMAP and lutidine in tetrahydrofuran—without acetic anhydride—were used as the capping mixture. This finding, combined with prior reports that phosphoramidite derivatives of protected nucleosides can react with the

N2-protected guanine base as well as the 5′-hydroxyl group [

25,

26], led the authors [

24] to propose that DAP nucleoside formation may originate from a phosphite triester adduct at the

O6-position of guanine formed during the coupling step. Furthermore, they reported that replacing DMAP with

N-methylimidazole (NMI) during capping completely eliminated the fluorescent product, although the amount of DAP nucleoside was reduced only 15-fold [

24].

As indicated in the literature review above, the presumed cause of the G/A substitutions is modification of the N2-protected guanine residue. However, for over 35 years, a comprehensive understanding of the mechanisms underlying these modifications during solid-phase synthesis has remained elusive, beyond their general association with the capping step.

To investigate how different capping conditions influence the probability of G/A substitutions, we synthesized six pairs of 107 bp DNA duplexes and analyzed them using NGS (

Figure 3).

Duplex-forming oligonucleotides were synthesized using our baseline protocol in which capping was performed with a Pr

2O/NMI mixture (see

Table 1), as well as modified protocols featuring variations in the capping step (

Table 2).

The synthesized oligonucleotides were purified by PAGE to minimize the impact of deletions and insertions. For each capping condition, duplicate syntheses were performed for each strand of the duplex (designated as #1 and #2). The NGS results are presented in

Figure 4, with the corresponding raw data provided in

Supplementary File S3. A comparison between the two independent syntheses for each capping condition demonstrates the high reproducibility of the errors profile for each protocol (

Figure 4).

In the protocol without capping (Capping I,

Table 3), deletions were the predominant error types (

Figure 5). The median error probabilities for the G/− + C/− and A/− + T/− pairs were 0.128% and 0.153%, respectively.

In addition to deletions, the most frequent errors were base substitutions, specifically G/A + C/T and A/G + T/C. The median error probability for G/A + C/T substitutions was 0.067%, while for A/G + T/C substitutions, it was 0.055%.

Introduction of the capping step into the synthesis protocol significantly increases the frequency of G/A + C/T substitutions (blue circles,

Figure 4 and

Figure 5). For instance, using Pr

2O/NMI (Capping II,

Table 2), the G/A + C/T substitution probability rises to 0.22%, and with Pr

2O/DMAP (Capping III,

Table 2), it increases further to 0.451%. Notably, under capping conditions, G/A + C/T substitutions became more frequent than deletions, a reversal of the trend observed in Capping I (

Table 2). Analysis revealed that deletions and A/G + T/C substitutions, identified as the most prevalent errors in the no-capping protocol, remained unaffected by the presence of the capping step. Based on these data, we concluded that the capping step promotes side reactions leading to guanine base modification, consistent with previously reported finding [

22,

23,

24].

Can the frequency of G/A + C/T substitutions be modulated by altering the composition of the capping reagents? Furthermore, how do modifications to the synthesis protocol affect the magnitude of deletion errors? To address these questions, we performed a series of experiments (

Figure 3) with specific adjustments. Since a key objective was to investigate the impact of capping conditions on deletion frequency, we utilized crude (unpurified) oligonucleotides for this analysis.

As chain length increases, the efficiency of all steps in the oligonucleotide synthesis cycle typically decreases, promoting the accumulation of deletions [

27]. To eliminate the influence of chain length on deletion error frequency, we employed a shortened 50 bp duplex instead of the previously used 107 bp duplex. Each strand of the duplex was synthesized using both the baseline protocol (see

Table 1) as well as modified protocol where the capping reagent composition, the number of capping cycles, and their order were varied (see

Table 3).

For the study, acetic and propionic anhydrides in combination with

N-methylimidazole, as well as the commercially available UniCap Phosphoramidite (Glen Research) used with 5-ethylthio-1H-tetrazole, were selected as capping reagents. The rationale for employing a phosphoramidite-derived capping agent originated from our sequencing data (

Table 2,

Figure 5), which show that 107-mer oligonucleotides synthesized without a capping step exhibited the lowest levels of G/A + C/T substitutions (

Figure 5). Based on this observation, we hypothesized that utilizing phosphoramidite-based chemistry for capping would maintain these low substitutions frequencies.

Consequently, 50-mer oligonucleotides were synthesized under seven distinct capping conditions. An analysis of NGS data from the corresponding duplexes revealed a pattern consistent with our previous experiment: variations in capping conditions exclusively influenced the frequencies of G/A + C/T substitutions and deletions (

Supplementary File S1.Figures S1 and S2,

Supplementary File S3). Moreover, the proportion of G/A + C/T substitutions varied significantly depending on the specific composition of the capping mixture (

Figure 6 and

Supplementary File S1.Figure S2).

Among the single-step capping protocol (conditions II, V, and VII in

Figure 6), the highest frequency of G/A + C/T substitutions was observed with the Ac

2O/NMI-based mixture (condition VII,

Figure 6), yielding a median value of 0.607%. Replacing acetic anhydride with propionic anhydride (condition II,

Figure 6) reduced the frequency of these substitutions to 0.343% (

Supplementary File S1.Figure S2). Meanwhile, the level of deletion errors remained comparable between the acetic and propionic anhydrides treatments (

Figure 6).

Double capping—performing both before and after the oxidation step—using either Ac

2O/NMI or Pr

2O/NMI mixtures significantly reduced the frequency of deletion errors compared to single-step capping protocols (compare conditions VII/II with VIII/IV in

Figure 6). No difference in deletion rates was observed between conditions VIII and IV (

Table 3,

Figure 6). However, the introduction of an additional capping step—and consequently increased exposure to carboxylic acid anhydrides—led to an elevated median frequency of G/A + C/T substitutions. Nevertheless, these increases were not statistically significant when comparing single versus double capping for either Ac

2O/NMI (VII vs. VIII) or Pr

2O/NMI (IV vs. II). Notable, the second capping step further amplified the performance gap between the two anhydrides (

Supplementary File S1.Figure S2).

These findings indicate that the use of carboxylic acid anhydrides of less acidic carboxylic acids is preferable for capping. As demonstrated, propionic anhydride maintains the effective elimination of N − 1 sequences during synthesis, while the associated increase in G/A + C/T substitution frequency is less pronounced than that observed with acetic anhydride.

Switching to an alternative capping method based on phosphoramidite chemistry (Capping V,

Table 3) did not result in the pronounced increase in G/A + C/T substitutions observed with carboxylic acid anhydrides (

Figure 6,

Supplementary File S1.Figure S2 and

Supplementary File S3). The median frequency of these substitutions using UniCap Phosphoramidite (Capping V) was 0.079%, which is 4-fold lower than with Pr

2O/NMI (Capping II) and 7.5-fold lower than with Ac

2O/NMI (Capping VII). Notably, the level of deletion errors with UniCap remained comparable to that of anhydride-based protocols (

Figure 6).

The introduction of a second capping step—using either acetic (Capping IX,

Table 3) or propionic (Capping VI,

Table 3) anhydride—significantly increased the median frequency of G/A + C/T substitutions from 0.079% (Capping V) to 0.243% (Capping IX) and 0.213% (Capping VI) (

Supplementary File S1.Figure S2). Nevertheless, this hybrid capping approach significantly reduced the frequency of deletion errors (

Figure 6).

It has been previously hypothesized that guanosine modification arises from a side reaction between the activated phosphoramidite and the

O6-atom of guanine [

24], where subsequent capping and ammonolysis lead to the formation of the DAP nucleoside. However, our data indicate that carboxylic acid anhydride-based capping mixtures are independently capable of reacting with the guanine base. This is evidenced by the increase in G/A + C/T substitution frequencies in two key scenarios: (1) when a hybrid approach was employed—initial capping with UniCap followed by treatment with acetic or propionic anhydride after oxidation—and (2) when the substitution profile shifted specifically in response to the change from acetic to propionic anhydride.

While the precise mechanism of guanine modification during oligonucleotide synthesis remains speculative—given the limitations of monitoring transient intermediates during automated solid-phase synthesis—our results provide strong evidence that components of carboxylic acid anhydrides-based capping mixtures react directly with N2-protected guanosine. This interaction likely involves the O6-position, leading to the observed permanent modifications in the final product.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Chemistry

For oligonucleotides up to 50 nucleotides in length, Universal CPG 1000Å (Biosset, Novosibirsk, Russia) was used as the solid support; for 107-mer oligonucleotides—Universal CPG 2000Å (Glen Research, Sterling, VA, USA). Deprotection of the 5′-dimethoxytrityl group was carried out using 3% (v/v) solution of dichloroacetic acid (>99%, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MA, USA) in toluene (>99%, Reakhim, Moscow, Russia). For coupling step, 0.45 M solution of 5-ethylthio-1H-tetrazole (>99%, ChemGenes, Wilmington, MA, USA) in anhydrous acetonitrile (HPLC grade, Fisher Chemical, Pittsburgh, PA, USA) and 0.1 M solutions of phosphoramidite monomers (N2-isobutyryl-5′-O-(4,4′-dimethoxytrityl)-2′-deoxyguanosine-3′-O-[O-(2-cyanoethyl)-N,N′-diisopropylphosphoramidite], N6-benzoyl-5′-O-(4,4′-dimethoxytrityl)-2′-deoxyadenosine-3′-O-[O-(2-cyanoethyl)-N,N′-diisopropylphosphoramidite], N4-acetyl-5′-O-dimethoxytrityl-(4,4′-dimethoxytrityl)-2′-deoxycytidine-3′-O-[O-(2-cyanoethyl)-N,N′-diisopropylphosphoramidite] and 5′-O-dimethoxytrityl-(4,4′-dimethoxytrityl)-2′-deoxythymidine-3′-O-[O-(2-cyanoethyl)-N,N′-diisopropylphosphoramidite] (all >98% purity, Sigma-Aldrich, USA)) in acetonitrile were used. Capping of unreacted 5′-hydroxyl groups was performed using a mixture of propionic anhydride (99%, Acros Organics, Wilmington, MA, USA) or acetic anhydride (≥99%, Sigma-Aldrich, USA) in the presence of 4-dimethylaminopyridine (99%, Acros Organics, USA) or N-methylimidazole (99%, Alfa Aesar, Haverhill, MA, USA). Also, Unicap Phosphoramidite (Glen Research, USA) was used as an alternative capping reagent. Solvents for capping were either acetonitrile or tetrahydrofuran (>99.5%, Panreac Applichem, Castellar del Vallès, Spain). Oxidation of the phosphite triester was achieved using a solution of 0.02 M iodine (Reakhim, Russia) in pyridine (99%, Panreac Applichem, Spain) and deionized water (milli-Q grade), with tetrahydrofuran serving as the solvent carrier. Following synthesis, oligonucleotides were cleaved from the solid support and deprotected using a 40% aqueous methylamine solution (>99%, Acros Organics, USA) and 30% aqueous ammonia (Reakhim, Russia). Other chemicals were supplied by Merck (Darmstadt, Germany), Acros Organics (USA), and Reakhim (Russia).

3.2. Oligonucleotide Synthesis

Oligodeoxyribonucleotides were synthesized on an automatic ASM-2000 DNA/RNA synthesizer (Biosset, Russia) at a 0.2-µmol scale using 2′-deoxyphosphoramidites and solid-phase phosphoramidite synthesis protocols [

28], optimized for the synthesizer (

Table 1,

Table 2 and

Table 3). The oligonucleotides were cleaved from the solid support, and the protective groups were removed from the nucleobases by treatment with AMA mixture (30% ammonia hydroxide/40% methylamine mixture, 1:1

v/

v) for 80 min at 25 °C, followed by 120 min at 45 °C. The crude oligonucleotides were then precipitated with ethanol in the presence of 0.3 M NaCl. The resulting precipitate was washed with ethanol, dried, and dissolved in 100 µL of deionized water.

3.3. Purification of Oligonucleotides and Duplexes

Oligonucleotides (olig_107_1 and olig_107_2) and 107 bp duplexes were purified by PAGE. For purification of 107-mer single-stranded oligonucleotides, the following denaturing conditions were used: 12% gel (acrylamide:bisacrylamide = 19:1) containing 8 M urea, 89 mM Tris-borate (pH 8.3), and 2 mM Na2EDTA, electrophoresis was performed at 50 V/cm. For 107 bp duplexes purification, identical gel compositions but without urea were applied and the voltage was 40 V/cm. Gel pieces containing oligonucleotide material were incubated in water for 12 h. The resulting aqueous eluates of the target oligonucleotide fractions were concentrated to dryness and precipitated with ethanol as Na+ salts.

3.4. Duplex Assembly

Duplexes were obtained by annealing of equimolar amounts of complementary strands. The buffer used for annealing contained 50 mM NaCl, 10 mM Tris-HCl and 10 mM MgCl2, pH 7.9 at 25 °C. The mixture of two oligonucleotides in buffer was heated to 95 °C for 5 min and then gradually cooled to 20 °C at a rate of 2.0 °C/min using a thermal cycler.

3.5. Assembly of T5 Exonuclease Gene

The assembly of T5 exonuclease gene was performed by polymerase chain assembly (PCA) using a set of oligonucleotides (

Supplementary File S1.Table S1). All thermocycling protocols had fixed conditions of a 2 min hot start at 98 °C, denaturation of 98 °C for 20 s, extension of 72 °C for 20 s, and a final extension at 72 °C for 3 min. The number of cycles and annealing conditions were varied.

For PCA, a mix containing a solution of oligonucleotides (

Supplementary File S1.Table S1) 4 µL (0.1 µM of each oligonucleotide strand), 4 µL of 5× GC buffer, 2 µL of dNTP, 1 µL of Mg

2+ (50 mM), 8.75 µL of nuclease-free water and 0.25 µL of Phusion High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase (2 U/µL, New England BioLabs, Ipswich, MA, USA) was prepared. Annealing conditions for PCA were 60 °C for 30 s and 25 cycles.

Follow-up PCRs were prepared with 1 µL of PCA mix, 4 µL of 5× GC buffer, 1 µL of each primer (10 µM) 0.4 µL of dNTP, 12.4 µL of nuclease-free water and 0.2 µL of Phusion High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase (2 U/µL, New England BioLabs, USA). Annealing conditions for PCR were 56 °C for 30 s and 30 cycles.

3.6. Cloning and Sequencing of Synthetic T5 Exonuclease Gene

Synthetic gene constructs were cloned into the pUC19 vector using a traditional cloning workflow. Amplified T5 exonuclease gene and vector were digested with 20U of each restriction enzyme (Sybenzyme, Novosibirsk, Russia). The linearized vector was treated with 10U thermolabile alkaline phosphatase (Sybenzyme, Russia). DNA fragments with sticky ends were purified with “DNA isolation kit for Isolation of DNA from Reaction Mixtures” (Biolabmix, Novosibirsk, Russia). For ligation, the vector and gene fragment were mixed in a 1:3 molar ratio. The sticky ends were ligated using 100 U of T4 ligase (Evrogene, Moscow, Russia).

Five microliters of the cloning product were transformed into E. coli NovaBlue (Merk, Germany) electrocompetent cells. A BioRad MicroPulser Electroporator (Hercules, CA, USA) was used for electroporation. The procedure was performed in 1 mm cuvettes and with a standard Ec1 program (1.8 kV, 2.5 ms).

Cells were grown on agar plates with 100 µg/mL ampicillin for 16 h and then white colonies were collected for screening. Colony screening was carried out with PCR using M13 primers. Colonies containing T5 exonuclease gene insert were analyzed by Sanger sequencing, which was carried out at the Genomics Core Facility (ICBFM SB RAS, Novosibirsk, Russia).

3.7. NGS

To prepare NGS libraries, oligonucleotide duplexes were phosphorylated with polynucleotide kinase, dA-tailed, and ligated to NGS adapters followed by the inclusion of index and sequencing adaptors with PCR, as was described earlier [

29]. NGS libraries were pooled in equimolar concentrations and sequenced with MiniSeq Mid-Output kit (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) 300 cycles and MiniSeq Illumina device (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA).

3.8. Processing of NGS Results

NGS reads were mapped onto the reference nucleotide sequences with bwa version 0.7.17-r1188 “mem” command [

30] followed by SAM to BAM file conversion with picard (version 2.0.1) “AddOReplaceReadGroups” command. Positions and types of the mismatches, insertions, and deletions were registered with in-house Python (3.13.5) scripts, considering only events observed in both NGS reads (R1 and R2) simultaneously. Since NGS and DNA-polymerase accuracies (both values are about 99.99%) are much higher than the oligonucleotide synthesis accuracy (about 95–99%), most of the differences between reference sequence and NGS read were likely to be due to errors caused by chemical oligonucleotide synthesis.

3.9. Statistics

Data are expressed as the median or, if not specified, as the mean ± SD for at least three independent experiments.

The relative error frequency per 1 kb (

f) was calculated using the number of sequenced clones (

n), the number of errors in clone

i (

xi), and the length of sequence data from clone

i (

li):

To estimate the number of clones required for screening to obtain at least one error-free clone with 90% probability, the experimental data were fitted to a Poisson distribution.

Every pair of errors, obtained with NGS, at each position was counted and divided by two, because we analyzed two chains simultaneously, and by the total number of reads, and was then multiplied by 100 to calculate the error rates, %. Subsequent statistical analysis was performed using the Mann–Whitney U test.