Upconversion Nanoparticles with Mesoporous Silica Coatings for Doxorubicin Targeted Delivery to Melanoma Cells

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Characterization of UCNP@mSiO2-FA

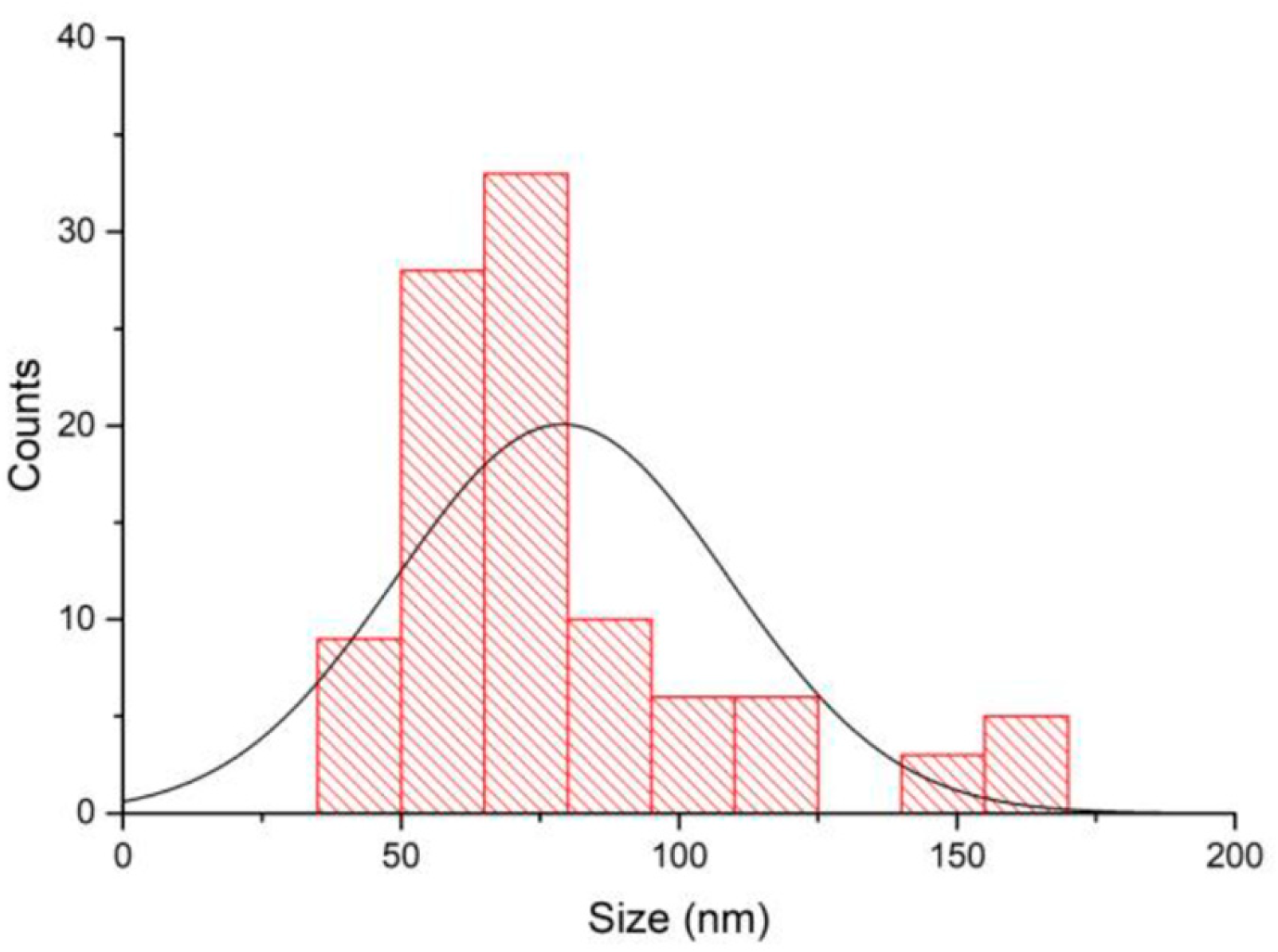

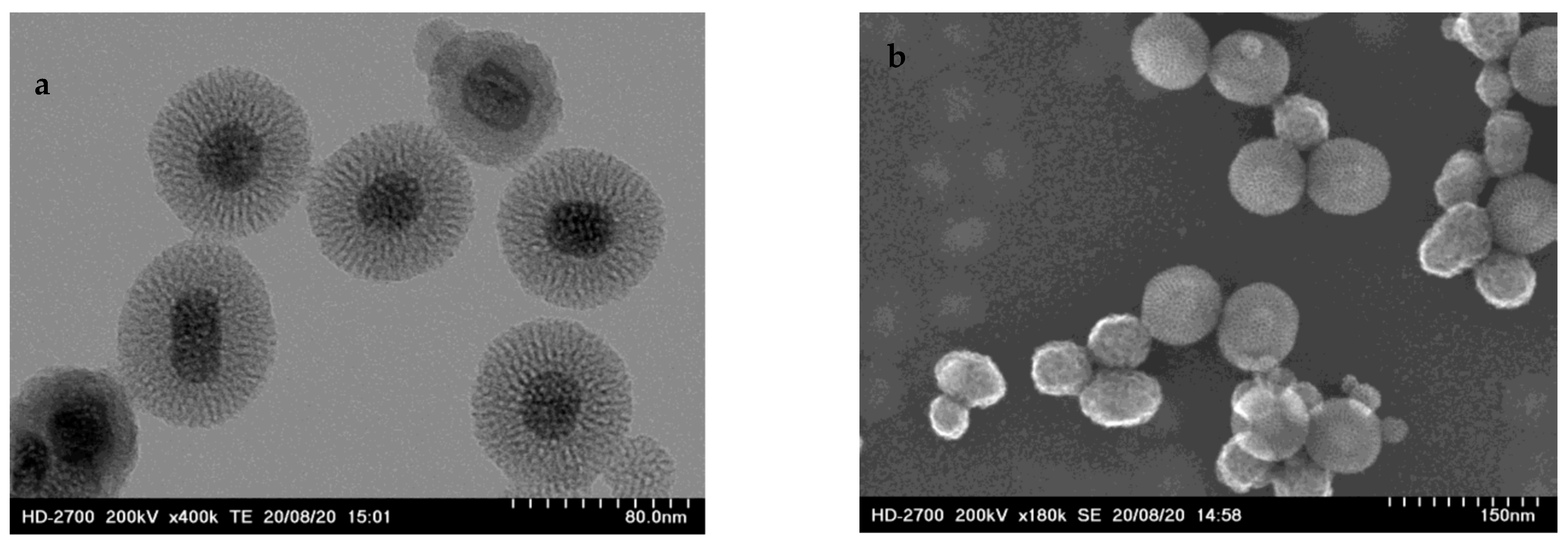

2.1.1. Size of the Nanoparticles

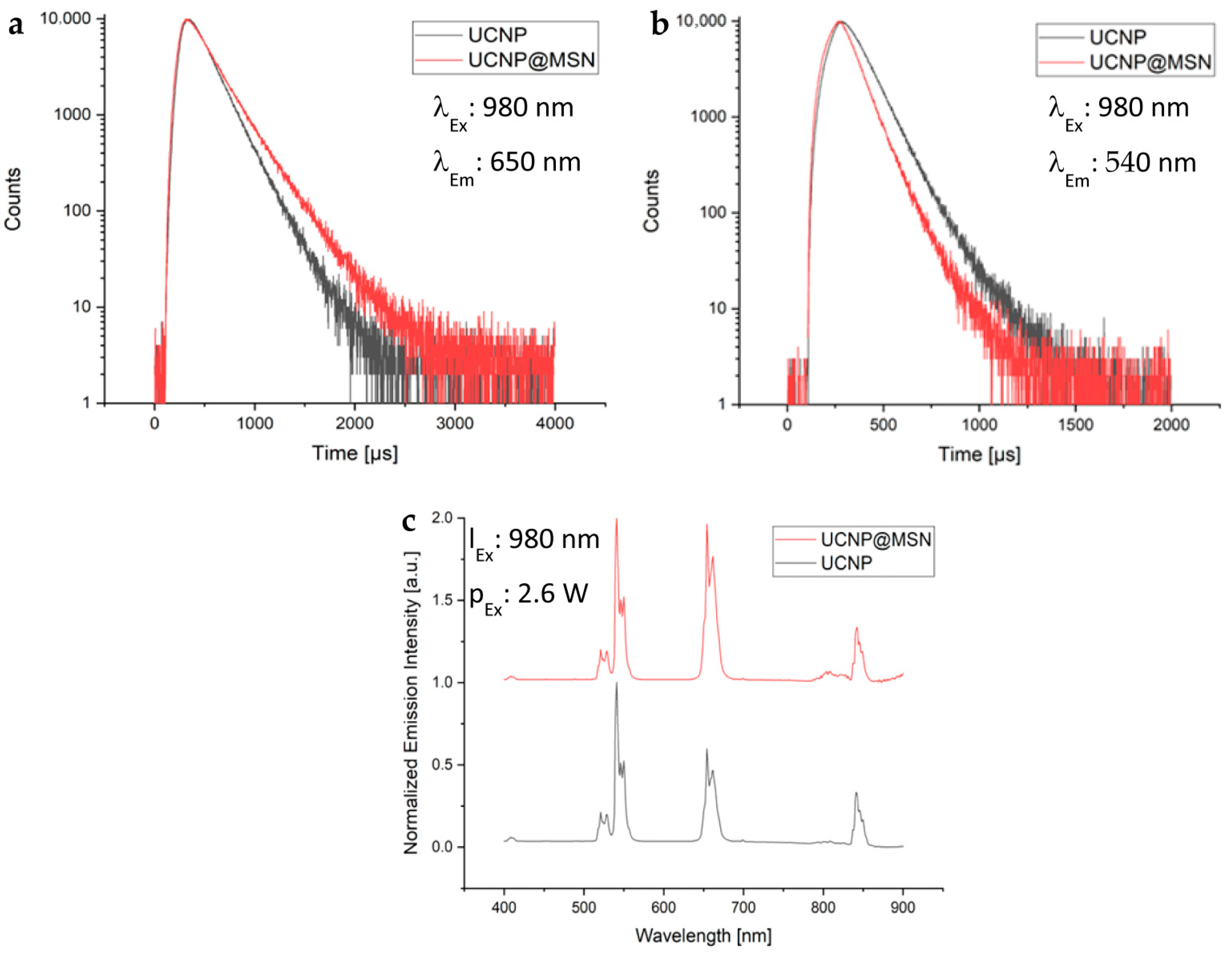

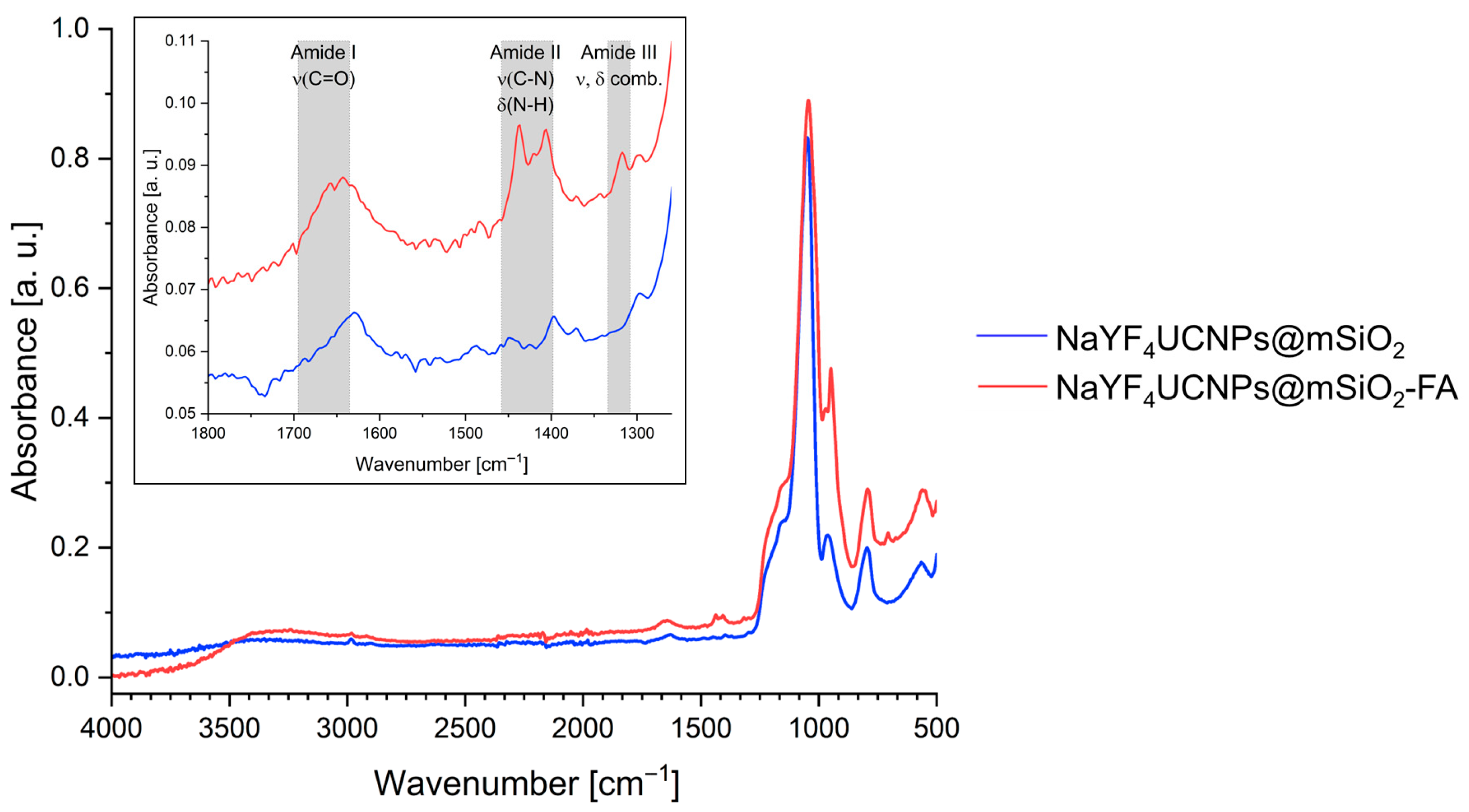

2.1.2. Surface Functionalization and Characterization

2.1.3. Hydrodynamic Diameter and Surface Charge in Biological and Aqueous Media

2.2. Loading of Doxorubicin

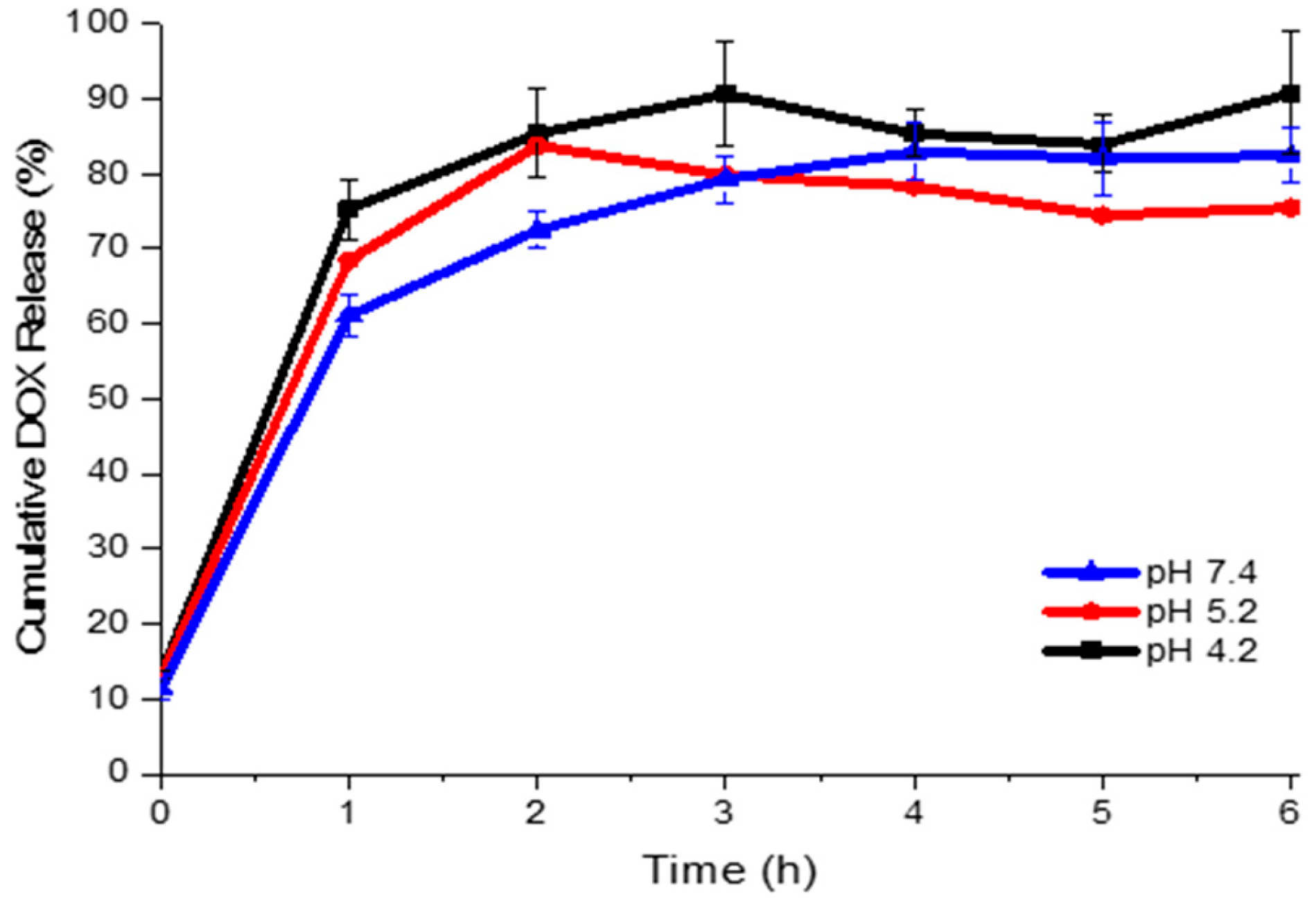

2.3. Doxorubicin Release

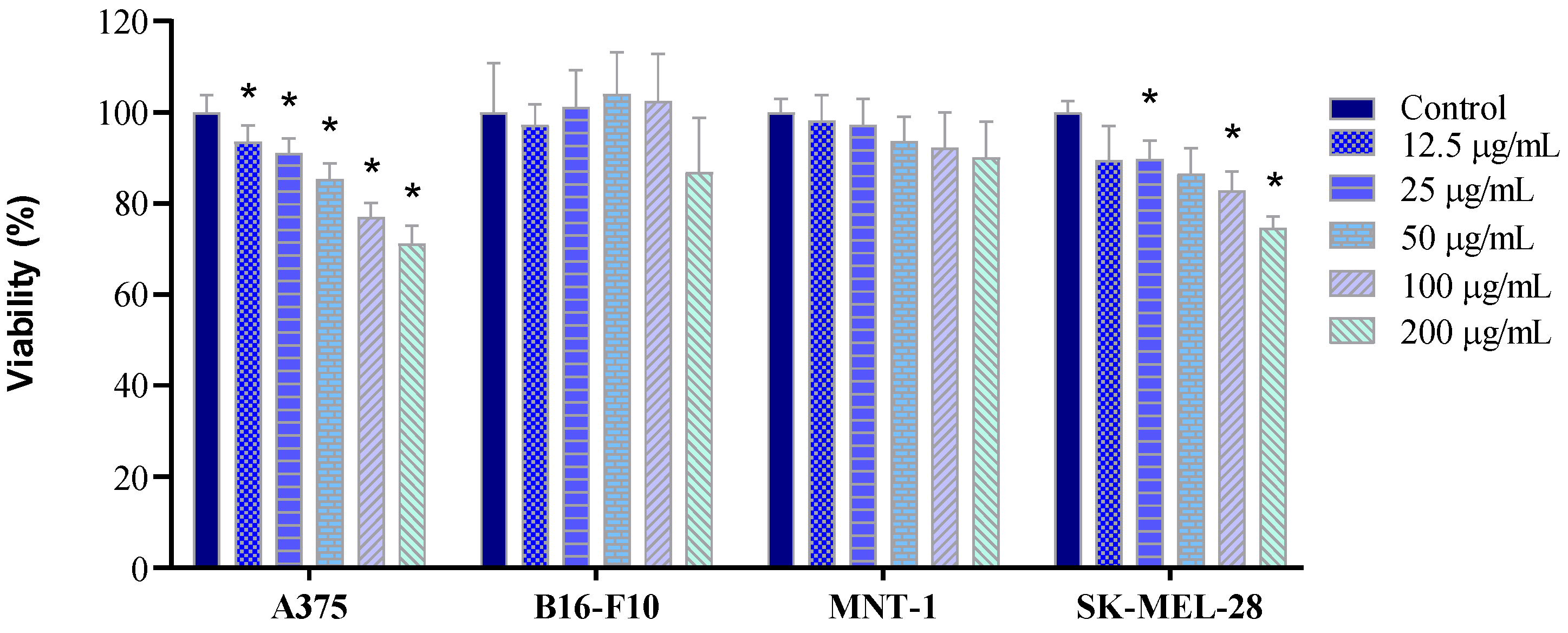

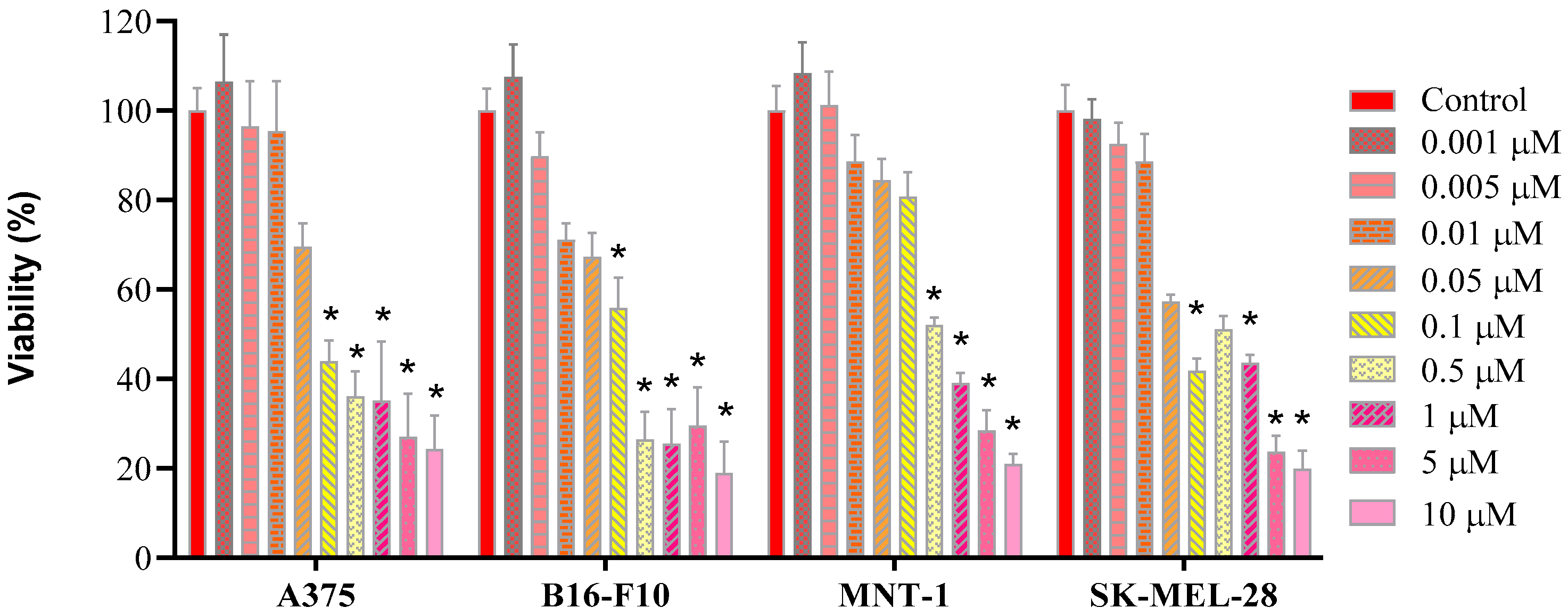

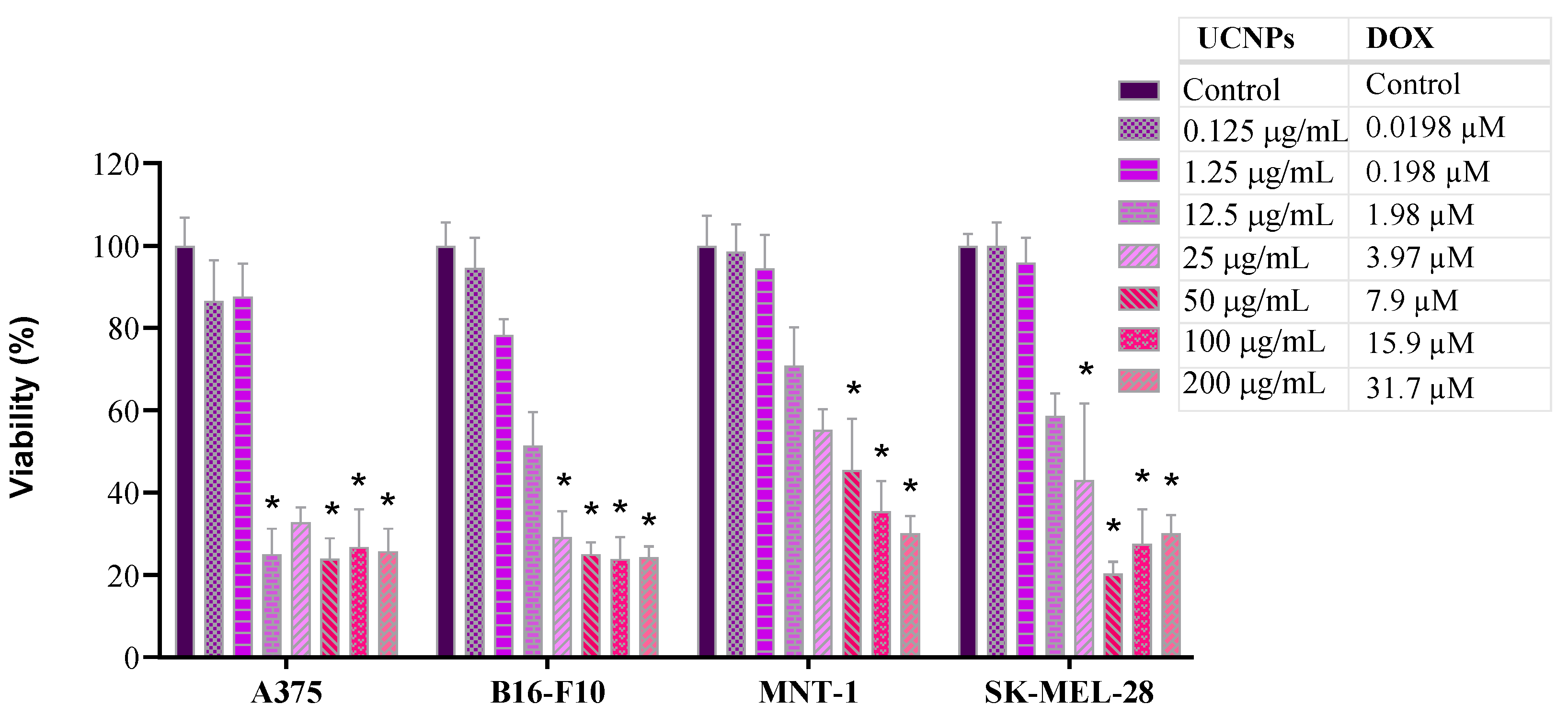

2.4. Cell Viability

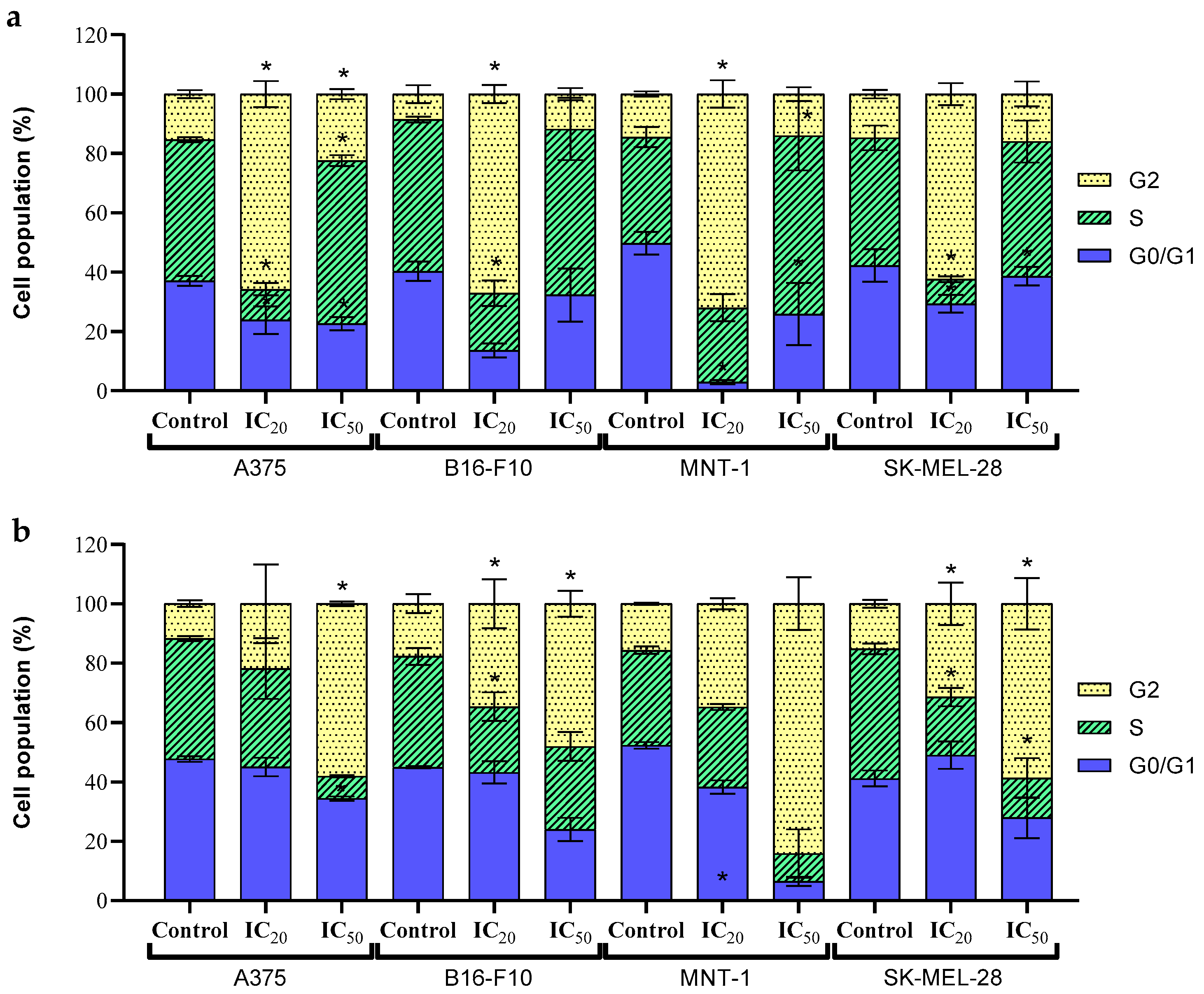

2.5. Cell Cycle

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Chemicals

3.2. Synthesis of UCNP

3.3. Coating of UCNP with a Mesoporous Silica Shell (UCNP@mSiO2)

3.4. Functionalization of UCNP@mSiO2 with Folic Acid

3.5. Nanoparticle Characterization

3.6. Doxorubicin Loading

3.7. Drug Release Profile

3.8. Cell Culture

3.9. Cell Viability Evaluation

3.10. Cell Cycle Analysis

3.11. Statistical Analyses

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Initial [DOX] (μg/mL) | % Efficiency | Loaded DOX (μg/mg) |

|---|---|---|

| 145.57 | 74.83 | 92.25 |

| 73.92 | 94.32 | |

| 75.85 | 92.72 | |

| 73.97 | 91.58 | |

| 72.40 | 91.59 | |

| 75.18 | 88.91 |

References

- Schadendorf, D.; van Akkooi, A.C.J.; Berking, C.; Griewank, K.G.; Gutzmer, R.; Hauschild, A.; Stang, A.; Roesch, A.; Ugurel, S. Melanoma. Lancet 2018, 392, 971–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bray, F.; Ferlay, J.; Soerjomataram, I.; Siegel, R.L.; Torre, L.A.; Jemal, A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2018, 68, 394–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Survival Rates for Melanoma Skin Cancer. Available online: https://www.cancer.org/cancer/melanoma-skin-cancer/detection-diagnosis-staging/survival-rates-for-melanoma-skin-cancer-by-stage.html (accessed on 26 July 2025).

- Rühle, B.; Saint-Cricq, P.; Zink, J.I. Externally Controlled Nanomachines on Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles for Biomedical Applications. ChemPhysChem 2016, 17, 1769–1779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McNamara, K.; Tofail, S.A.M. Nanoparticles in biomedical applications. Adv. Phys. X 2017, 2, 54–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, J.; Li, P.; Li, L.; Yang, M. Biochemistry and biomedicine of quantum dots: From biodetection to bioimaging, drug discovery, diagnostics, and therapy. Acta Biomater. 2018, 74, 36–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, J.; Rodrigues, C.M.P.; Gaspar, M.M.; Reis, C.P. How to Treat Melanoma? The Current Status of Innovative Nanotechnological Strategies and the Role of Minimally Invasive Approaches like PTT and PDT. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 1817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rühle, B.; Clemens, D.L.; Lee, B.-Y.; Horwitz, M.A.; Zink, J.I. A Pathogen-Specific Cargo Delivery Platform Based on Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 6663–6668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, L.; Gowda, B.H.J.; Ahmed, M.G.; Abourehab, M.A.S.; Chen, Z.-S.; Zhang, C.; Li, J.; Kesharwani, P. Advancements in nanoparticle-based treatment approaches for skin cancer therapy. Mol. Cancer 2023, 22, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parveen, R.; Shamsi, T.N.; Fatima, S. Nanoparticles-protein interaction: Role in protein aggregation and clinical implications. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2017, 94, 386–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wang, Y.; Liang, R.; An, X.; Wang, K.; Shen, G.; Tu, Y.; Zhu, J.; Tao, J. Recent advances in targeted nanoparticles drug delivery to melanoma. Nanomed. Nanotechnol. Biol. Med. 2015, 11, 769–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhari, H.S.; Lohar, M.S.; Amritkar, A.S.; Jain, D.K.; Baviskar, D.T. Targeted drug delivery system: A Review. Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Rev. Res. 2011, 8, 160–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djayanti, K.; Maharjan, P.; Cho, K.H.; Jeong, S.; Kim, M.S.; Shin, M.C.; Min, K.A. Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles as a Potential Nanoplatform: Therapeutic Applications and Considerations. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 6349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ansari, A.A.; Parchur, A.K.; Li, Y.; Jia, T.; Lv, R.; Wang, Y.; Chen, G. Cytotoxicity and genotoxicity evaluation of chemically synthesized and functionalized upconversion nanoparticles. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2024, 504, 215672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palanikumar, L.; Kalmouni, M.; Houhou, T.; Abdullah, O.; Ali, L.; Pasricha, R.; Straubinger, R.; Thomas, S.; Afzal, A.J.; Barrera, F.N.; et al. pH-Responsive Upconversion Mesoporous Silica Nanospheres for Combined Multimodal Diagnostic Imaging and Targeted Photodynamic and Photothermal Cancer Therapy. ACS Nano 2023, 17, 18979–18999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Yang, Y.; Liu, C.; Guo, H.; Chen, Z.; Xia, J.; Liao, Y.; Tang, C.Y.; Law, W.C. Photo- and pH-responsive drug delivery nanocomposite based on o-nitrobenzyl functionalized upconversion nanoparticles. Polymer 2021, 229, 123961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thanasekaran, P.; Chu, C.H.; Wang, S.B.; Chen, K.-Y.; Gao, H.-D.; Lee, M.M.; Sun, S.-S.; Li, J.-P.; Chen, J.-Y.; Chen, J.-K.; et al. Lipid-Wrapped Upconversion Nanoconstruct/Photosensitizer Complex for Near-Infrared Light-Mediated Photodynamic Therapy. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 84–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastos, V.; Oskoei, P.; Andresen, E.; Saleh, M.I.; Rühle, B.; Resch-Genger, U.; Oliveira, H. Stability, dissolution, and cytotoxicity of NaYF4-upconversion nanoparticles with different coatings. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 3770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Lu, G.; Yu, Y.; Zhang, H.; Gao, J.; Sun, Z.; Lu, Y.; Zou, H. NIR-Responsive Copolymer Upconversion Nanocomposites for Triggered Drug Release in Vitro and in Vivo. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2019, 2, 495–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendez-Gonzalez, D.; Lopez-Cabarcos, E.; Rubio-Retama, J.; Laurenti, M. Sensors and bioassays powered by upconverting materials. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2017, 249, 66–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Generalova, A.N.; Chichkov, B.N.; Khaydukov, E.V. Multicomponent nanocrystals with anti-Stokes luminescence as contrast agents for modern imaging techniques. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2017, 245, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, S.; Zhou, J.; Zheng, K.; Bednarkiewicz, A.; Liu, X.; Jin, D. Advances in highly doped upconversion nanoparticles. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 2415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rafique, R.; Kailasa, S.K.; Park, T.J. Recent advances of upconversion nanoparticles in theranostics and bioimaging applications. TrAC-Trends Anal. Chem. 2019, 120, 115646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, L.; Li, W.; Li, Y.; Yin, S. Nanoparticle-based drug delivery systems targeting cancer cell surfaces. RSC Adv. 2023, 13, 21365–21382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ebrahimnejad, P.; Taleghani, A.S.; Asare-Addo, K.; Nokhodchi, A. An updated review of folate-functionalized nanocarriers: A promising ligand in cancer. Drug Discov. Today 2022, 27, 471–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-del-Campo, L.; Montenegro, M.F.; Cabezas-Herrera, J.; Rodríguez-López, J.N. The critical role of alpha-folate receptor in the resistance of melanoma to methotrexate. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2009, 22, 588–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuster, M.G.; Wang, J.; Fandiño, O.; Víllora, G.; Paredes, A.J. Folic Acid-Decorated Nanocrystals as Highly Loaded Trojan Horses to Target Cancer Cells. Mol. Pharm. 2024, 21, 2781–2794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majidi, F.S.; Mohammadi, E.; Mehravi, B.; Nouri, S.; Ashtari, K.; Neshasteh-riz, A. Investigating the effect of near infrared photo thermal therapy folic acid conjugated gold nano shell on melanoma cancer cell line A375. Artif. Cells Nanomed. Biotechnol. 2019, 47, 2161–2170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohade, A.A.; Jain, R.R.; Iyer, K.; Roy, S.K.; Shimpi, H.H.; Pawar, Y.; Rajan, M.G.R.; Menon, M.D. A Novel Folate-Targeted Nanoliposomal System of Doxorubicin for Cancer Targeting. AAPS PharmSciTech 2016, 17, 1298–1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tacar, O.; Sriamornsak, P.; Dass, C.R. Doxorubicin: An update on anticancer molecular action, toxicity and novel drug delivery systems. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2013, 65, 157–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Xu, X.; Chen, X.; Yang, R.; Xiao, Q.; Li, Y. Mesoporous silica coated Gd2(CO3)3:Eu hollow nanospheres for simultaneous cell imaging and drug delivery. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 62320–62326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, G.; Yin, W.; Jin, J.; Zhang, X.; Xing, G.; Li, S.; Gu, Z.; Zhao, Y. Engineered design of theranostic upconversion nanoparticles for tri-modal upconversion luminescence/magnetic resonance/X-ray computed tomography imaging and targeted delivery of combined anticancer drugs. J. Mater. Chem. B 2014, 2, 1379–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, G.; Zheng, X.; Zhang, X.; Yin, W.; Yu, J.; Wang, D.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, X.; Gu, Z.; Zhao, Y. TPGS-stabilized NaYbF4: ER Upconversion nanoparticles for dual-modal fluorescent/CT imaging and anticancer drug delivery to overcome multi-drug resistance. Biomaterials 2015, 40, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalilian, A.R.; Hosseini-Salekdeh, S.L.; Mahmoudi, M.; Yousefnia, H.; Majdabadi, A.; Majid Pouladian, M. Preparation and biological evaluation of radiolabeled-folate embedded superparamagnetic nanoparticles in wild-type rats. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 2011, 287, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Fan, J.; Zhao, Y.; Cheng, M.; Wang, X.; Jin, R.; Sun, T. A targeted drug delivery system based on folic acid-functionalized upconversion luminescent nanoparticles. J. Biomater. Appl. 2017, 31, 1247–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, Z.; Liu, X.; Niu, D.; Qin, L.; Li, Y. Upconversion Nanoparticle-Based Organosilica-Micellar Hybrid Nanoplatforms for Redox-Responsive Chemotherapy and NIR-Mediated Photodynamic Therapy. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2020, 3, 4655–4664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yang, P.; Ma, P.; Qu, F.; Gai, S.; Niu, N.; He, F.; Lin, J. Hollow structured SrMoO4:Yb3+, Ln3+ (Ln = Tm, Ho, Tm/Ho) microspheres: Tunable up-conversion emissions and application as drug carriers. J. Mater. Chem. B 2013, 1, 2056–2065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Xue, R.; Gulzar, A.; Kuang, Y.; Shao, H.; Gai, S.; Yang, D.; He, F.; Yang, P. Targeted and imaging-guided chemo-photothermal ablation achieved by combining upconversion nanoparticles and protein-capped gold nanodots. Chem. Eng. J. 2019, 370, 1239–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, X.; Zhao, F.; Wang, Y.; Yan, X.; Jia, S.; Du, B. CuS as a gatekeeper of mesoporous upconversion nanoparticles-based drug controlled release system for tumor-targeted multimodal imaging and synergetic chemo-thermotherapy. Nanomed. Nanotechnol. Biol. Med. 2017, 13, 1761–1772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, C.; Wang, W.; Wang, P.; Zhao, M.; Li, X.; Zhang, F. Near-Infrared Upconversion Mesoporous Cerium Oxide Hollow Biophotocatalyst for Concurrent pH-/H2O2-Responsive O2-Evolving Synergetic Cancer Therapy. Adv. Mater. 2018, 30, 1704833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, N.; Wu, B.; Hu, X.; Xing, D. NIR-triggered high-efficient photodynamic and chemo-cascade therapy using caspase-3 responsive functionalized upconversion nanoparticles. Biomaterials 2017, 141, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, B.; Shao, S.; Yu, C.; Teng, B.; Wang, M.; Cheng, Z.; Wong, K.-L.; Ma, P.; Lin, J. Large-Pore Mesoporous-Silica-Coated Upconversion Nanoparticles as Multifunctional Immunoadjuvants with Ultrahigh Photosensitizer and Antigen Loading Efficiency for Improved Cancer Photodynamic Immunotherapy. Adv. Mater. 2018, 30, 1802479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bastos, V.; Pascoal, S.; Lopes, K.; Mortari, M.; Oliveira, H. Cytotoxic effects of Chartergellus communis wasp venom peptide against melanoma cells. Biochimie 2024, 216, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cunha, C.; Marinheiro, D.; Ferreira, B.J.M.L.; Oliveira, H.; Daniel-da-Silva, A.L. Morin Hydrate Encapsulation and Release from Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles for Melanoma Therapy. Molecules 2023, 28, 4776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvador, D.; Bastos, V.; Oliveira, H. Hyperthermia Enhances Doxorubicin Therapeutic Efficacy against A375 and MNT-1 Melanoma Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ebbert, L.; von Montfort, C.; Wenzel, C.-K.; Reichert, A.S.; Stahl, W.; Brenneisen, P. A Combination of Cardamonin and Doxorubicin Selectively Affect Cell Viability of Melanoma Cells: An In Vitro Study. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svensson, S.P.S.; Lindgren, S.; Powell, W.; Green, H. Melanin inhibits cytotoxic effects of doxorubicin and daunorubicin in MOLT 4 cells. Pigment Cell Res. 2003, 16, 351–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomankova, K.; Polakova, K.; Pizova, K.; Binder, S.; Havrdova, M.; Kolarova, M.; Kriegova, E.; Zapletalova, J.; Malina, L.; Horakova, J.; et al. In vitro cytotoxicity analysis of doxorubicin-loaded/superparamagnetic iron oxide colloidal nanoassemblies on MCF7 and NIH3T3 cell lines. Int. J. Nanomed. 2015, 10, 949–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Cheng, L.; Liu, Z. Drug delivery with upconversion nanoparticles for multi-functional targeted cancer cell imaging and therapy. Biomaterials 2011, 32, 1110–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Grailer, J.J.; Rowland, I.J.; Javadi, A.; Hurley, S.A.; Steeber, D.A.; Gong, S. Multifunctional SPIO/DOX-loaded wormlike polymer vesicles for cancer therapy and MR imaging. Biomaterials 2010, 31, 9065–9073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz-Moralli, S.; Tarrado-Castellarnau, M.; Miranda, A.; Cascante, M. Targeting cell cycle regulation in cancer therapy. Pharmacol. Ther. 2013, 138, 255–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilmer, S.N.; Cogger, V.C.; Muller, M.; Couteur, D.G.L. The hepatic pharmacokinetics of doxorubicin and liposomal doxorubicin. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2004, 32, 794–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.S.; Lee, Y.S.; Kim, D.K. Doxorubicin exerts cytotoxic effects through cell cycle arrest and Fas-mediated cell death. Pharmacology 2009, 84, 300–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soe, Z.C.; Kwon, J.B.; Thapa, R.K.; Ou, W.; Nguyen, H.T.; Gautam, M.; Oh, K.T.; Choi, H.-G.; Ku, S.K.; Yong, C.S.; et al. Transferrin-conjugated polymeric nanoparticle for receptor-mediated delivery of doxorubicin in doxorubicin-resistant breast cancer cells. Pharmaceutics 2019, 11, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Purohit, M.P.; Verma, N.K.; Kar, A.K.; Singh, A.; Ghosh, D.; Patnaik, S. Inhibition of Thioredoxin Reductase by Targeted Selenopolymeric Nanocarriers Synergizes the Therapeutic Efficacy of Doxorubicin in MCF7 Human Breast Cancer Cells. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 36493–36512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andresen, E.; Islam, F.; Prinz, C.; Gehrmann, P.; Licha, K.; Roik, J.; Recknagel, S.; Resch-Genger, U. Assessing the reproducibility and up-scaling of the synthesis of Er,Yb-doped NaYF4-based upconverting nanoparticles and control of size, morphology, and optical properties. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 2288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilhelm, S.; Kaiser, M.; Würth, C.; Heiland, J.; Carrillo-Carrion, C.; Muhr, V.; Wolfbeis, O.S.; Parak, W.J.; Resch-Genger, U.; Hirsch, T. Water dispersible upconverting nanoparticles: Effects of surface modification on their luminescence and colloidal stability. Nanoscale 2015, 7, 1403–1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Liu, J.; Alonso, S.; Li, F.; Zhang, Y. Upconversion nanoparticles for sensitive and in-depth detection of Cu2+ ions. Nanoscale 2012, 4, 6065–6071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saint-Cricq, P.; Deshayes, S.; Zink, J.I.; Kasko, A.M. Magnetic field activated drug delivery using thermodegradable azo-functionalised PEG-coated core–shell mesoporous silica nanoparticles. Nanoscale 2015, 7, 13168–13172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnanasammandhan, M.K.; Idris, N.M.; Bansal, A.; Huang, K.; Zhang, Y. Near-IR photoactivation using mesoporous silica-coated NaYF4:Yb,Er/Tm upconversion nanoparticles. Nat. Protoc. 2016, 11, 688–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zar, J. Biostatistical Analysis, 3rd ed.; Prentice Hall International Inc.: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

| Sample | % C | % H | % N |

|---|---|---|---|

| UCNP@mSiO2 | 4.646 | 1.998 | 0.069 |

| UCNP@mSiO2-FA | 5.865 | 3.251 | 0.688 |

| DMEM | dH2O | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25 μg/mL | 100 μg/mL | 25 μg/mL | 100 μg/mL | |

| Dh (nm) | 82.1 ± 24.91 | 114.77 ± 13.71 | 174 ± 20.31 | 123.73 ± 13.07 |

| Peak 1 Area (%) | 66.07 ± 2.45 | 77.03 ± 3.02 | 96.77 ± 1.01 | 99.63 ± 0.64 |

| Dh Peak 1 (nm) | 305.37 ± 11.11 | 257.93 ± 19.45 | 79.57 ± 5.48 | 124.86 ± 13.71 |

| PdI | 0.676 ± 0.044 | 0.826 ± 0.068 | 0.342 ± 0.10 | 0.300 ± 0.011 |

| Zeta (mV) | −15.47 ± 0.74 | −13.07 ± 1.63 | −10.47 ± 0.61 | −10.8 ± 0.56 |

| Free DOX | UCNP@mSiO2-FA-DOX | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (µg/mL) | (µM DOX) | |||

| A375 | IC20 IC50 | 0.018 | 0.567 | 0.091 |

| 0.168 | 7.111 | 1.138 | ||

| B16-F10 | IC20 IC50 | 0.010 | 0.924 | 0.148 |

| 0.120 | 9.794 | 1.567 | ||

| MNT-1 | IC20 IC50 | 0.070 | 6.220 | 0.995 |

| 0.575 | 41.701 | 6.672 | ||

| SK-MEL 28 | IC20 IC50 | 0.010 | 2.598 | 0.416 |

| 0.200 | 13.187 | 2.110 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Oskoei, P.; Afonso, R.; Bastos, V.; Nogueira, J.; Keller, L.-M.; Andresen, E.; Saleh, M.I.; Rühle, B.; Resch-Genger, U.; Daniel-da-Silva, A.L.; et al. Upconversion Nanoparticles with Mesoporous Silica Coatings for Doxorubicin Targeted Delivery to Melanoma Cells. Molecules 2026, 31, 74. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010074

Oskoei P, Afonso R, Bastos V, Nogueira J, Keller L-M, Andresen E, Saleh MI, Rühle B, Resch-Genger U, Daniel-da-Silva AL, et al. Upconversion Nanoparticles with Mesoporous Silica Coatings for Doxorubicin Targeted Delivery to Melanoma Cells. Molecules. 2026; 31(1):74. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010074

Chicago/Turabian StyleOskoei, Párástu, Rúben Afonso, Verónica Bastos, João Nogueira, Lisa-Marie Keller, Elina Andresen, Maysoon I. Saleh, Bastian Rühle, Ute Resch-Genger, Ana L. Daniel-da-Silva, and et al. 2026. "Upconversion Nanoparticles with Mesoporous Silica Coatings for Doxorubicin Targeted Delivery to Melanoma Cells" Molecules 31, no. 1: 74. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010074

APA StyleOskoei, P., Afonso, R., Bastos, V., Nogueira, J., Keller, L.-M., Andresen, E., Saleh, M. I., Rühle, B., Resch-Genger, U., Daniel-da-Silva, A. L., & Oliveira, H. (2026). Upconversion Nanoparticles with Mesoporous Silica Coatings for Doxorubicin Targeted Delivery to Melanoma Cells. Molecules, 31(1), 74. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010074