Preparation and Whitening Activity of Sialoglycopeptide of Chalaza from Liquid Egg Process

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

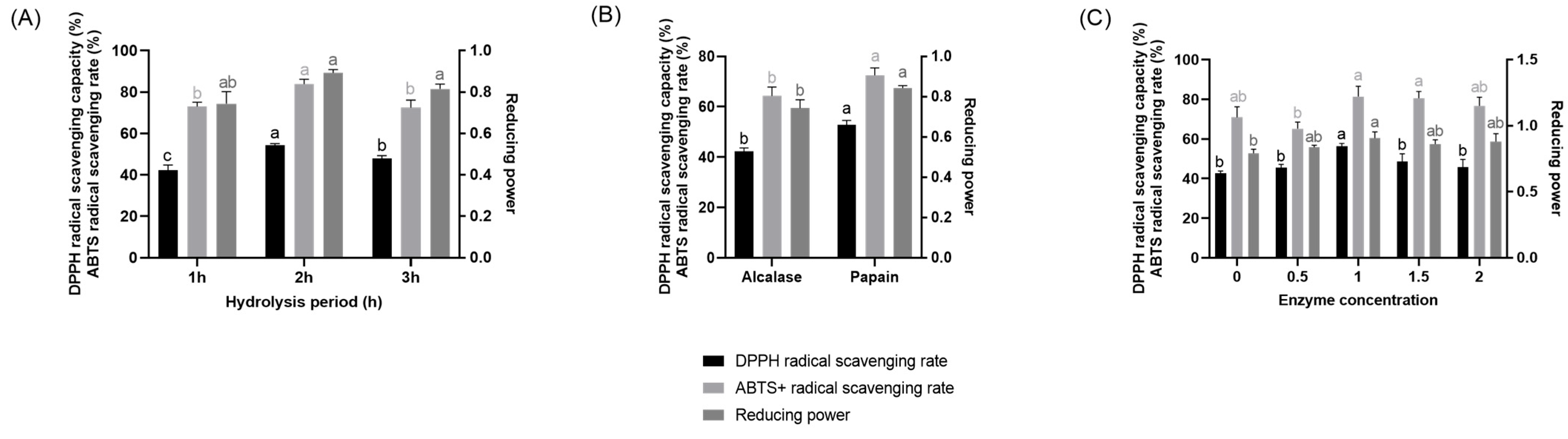

2.1. Preparation of CHAH

2.2. Sialic Acid (N-Acetylneuraminic Acid) Content in CHAH and CHA

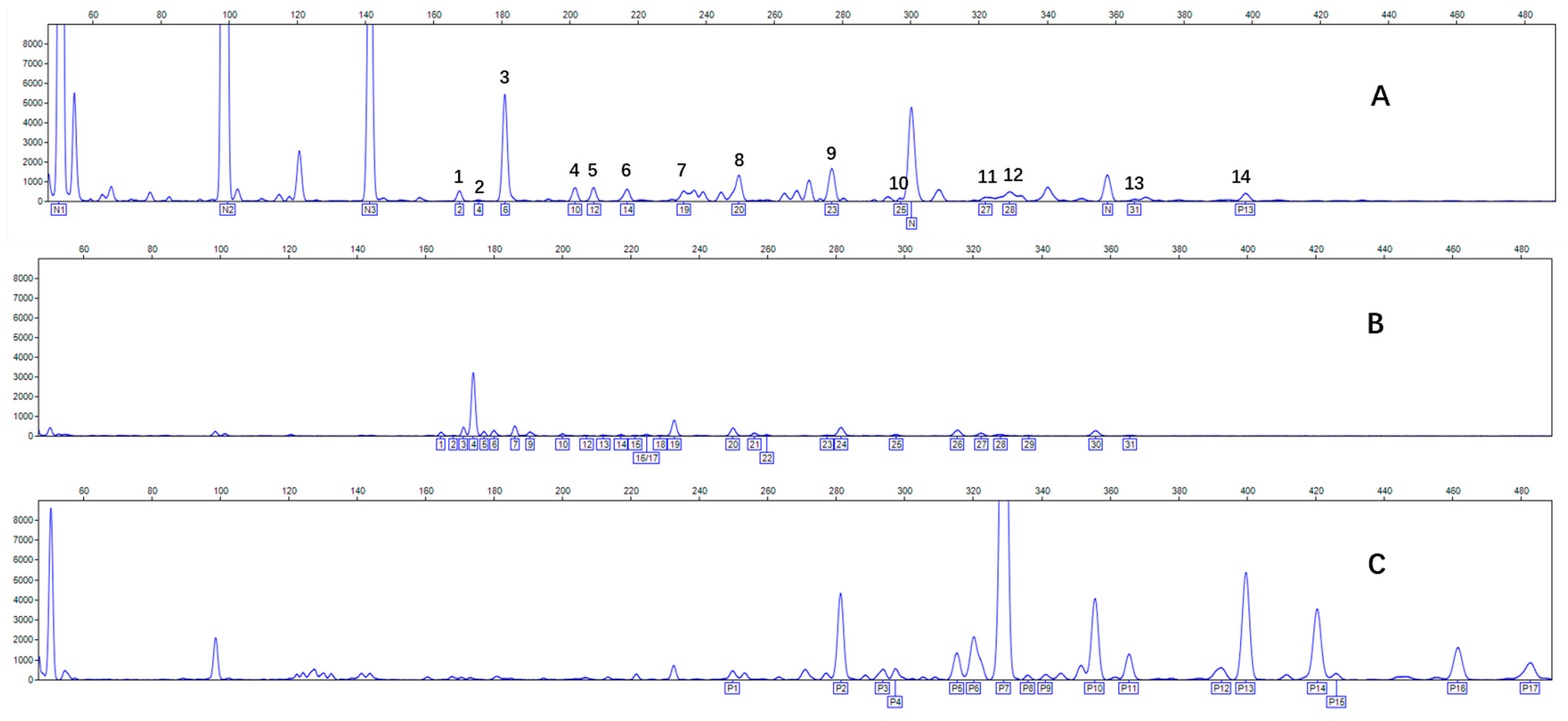

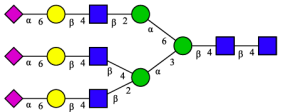

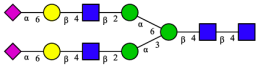

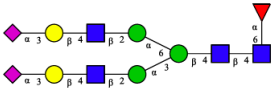

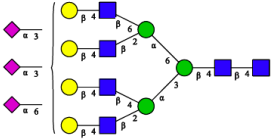

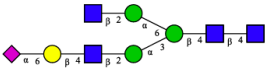

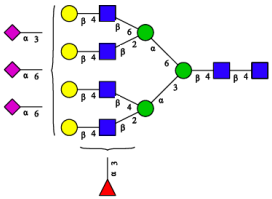

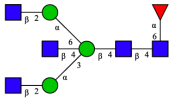

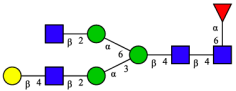

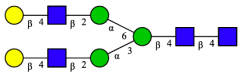

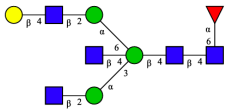

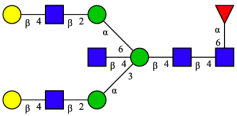

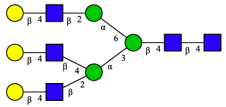

2.3. N-Glycomic Analysis of CHAH

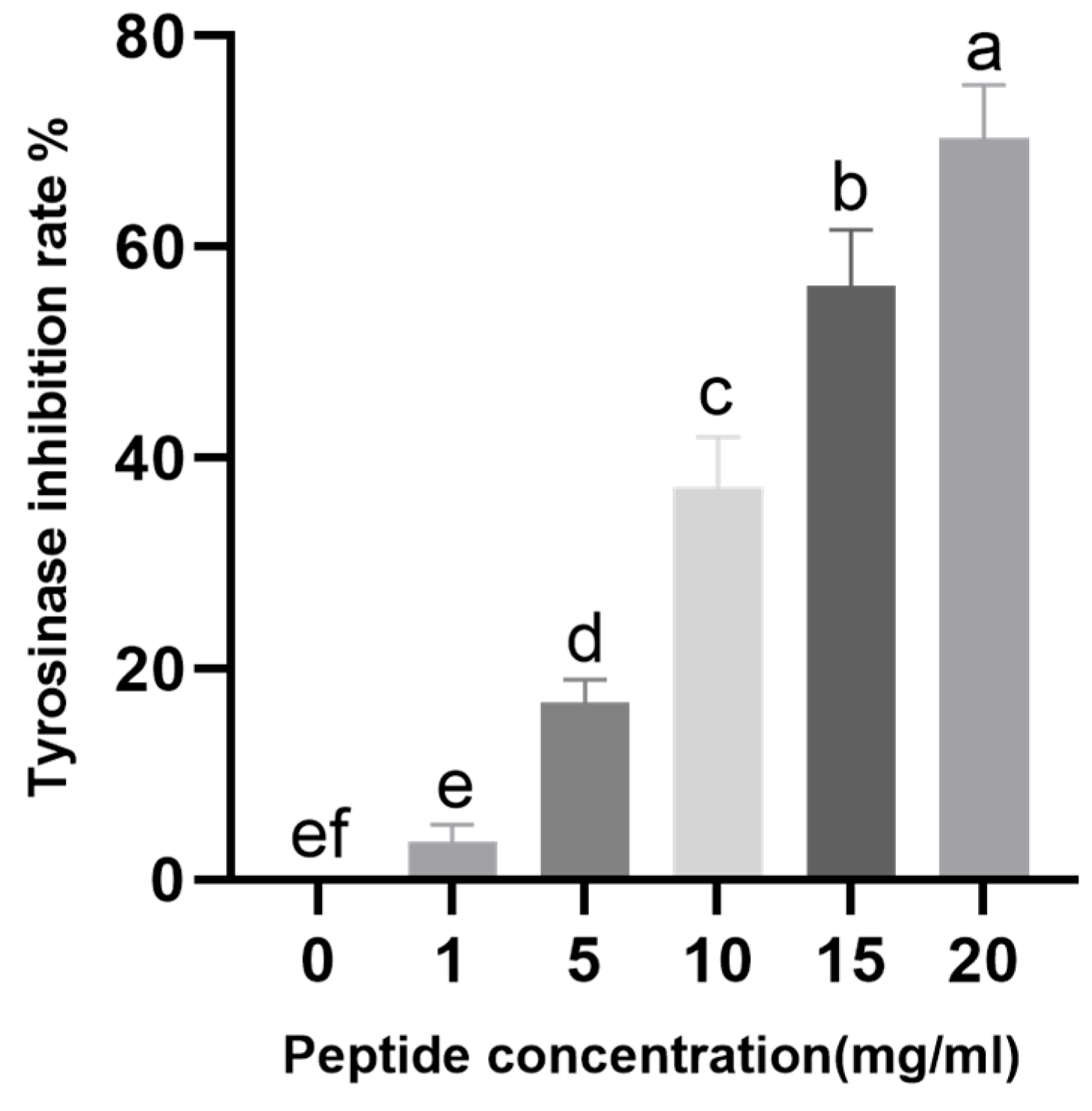

2.4. Effect of CHAH on Tyrosinase Activity

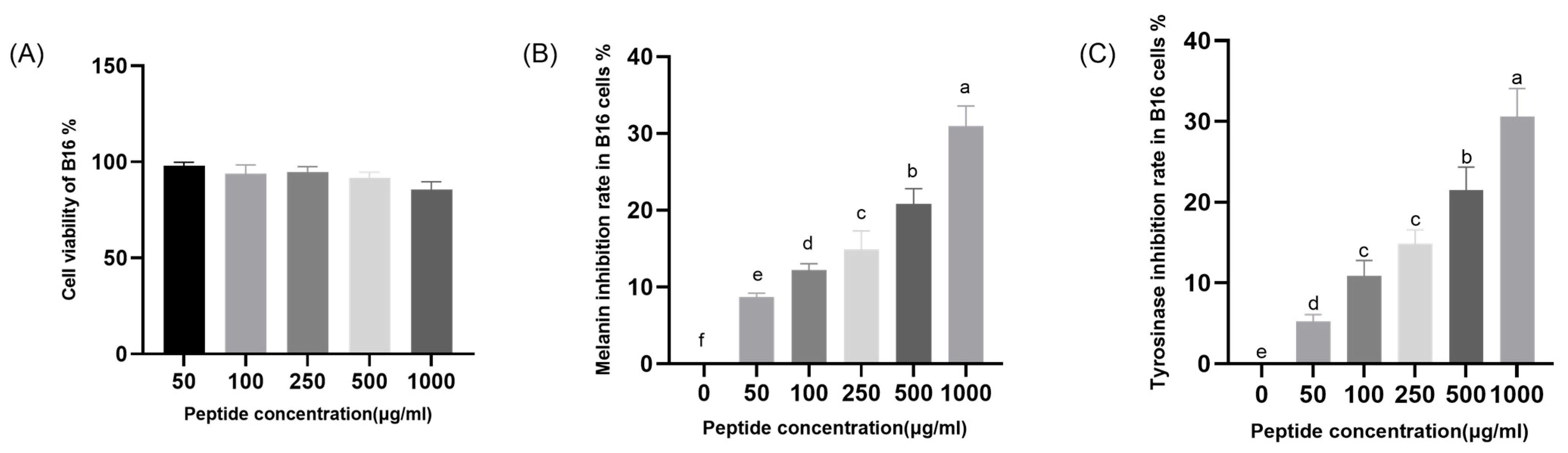

2.5. Analysis of the In Vitro Skin-Whitening Efficacy of CHAH

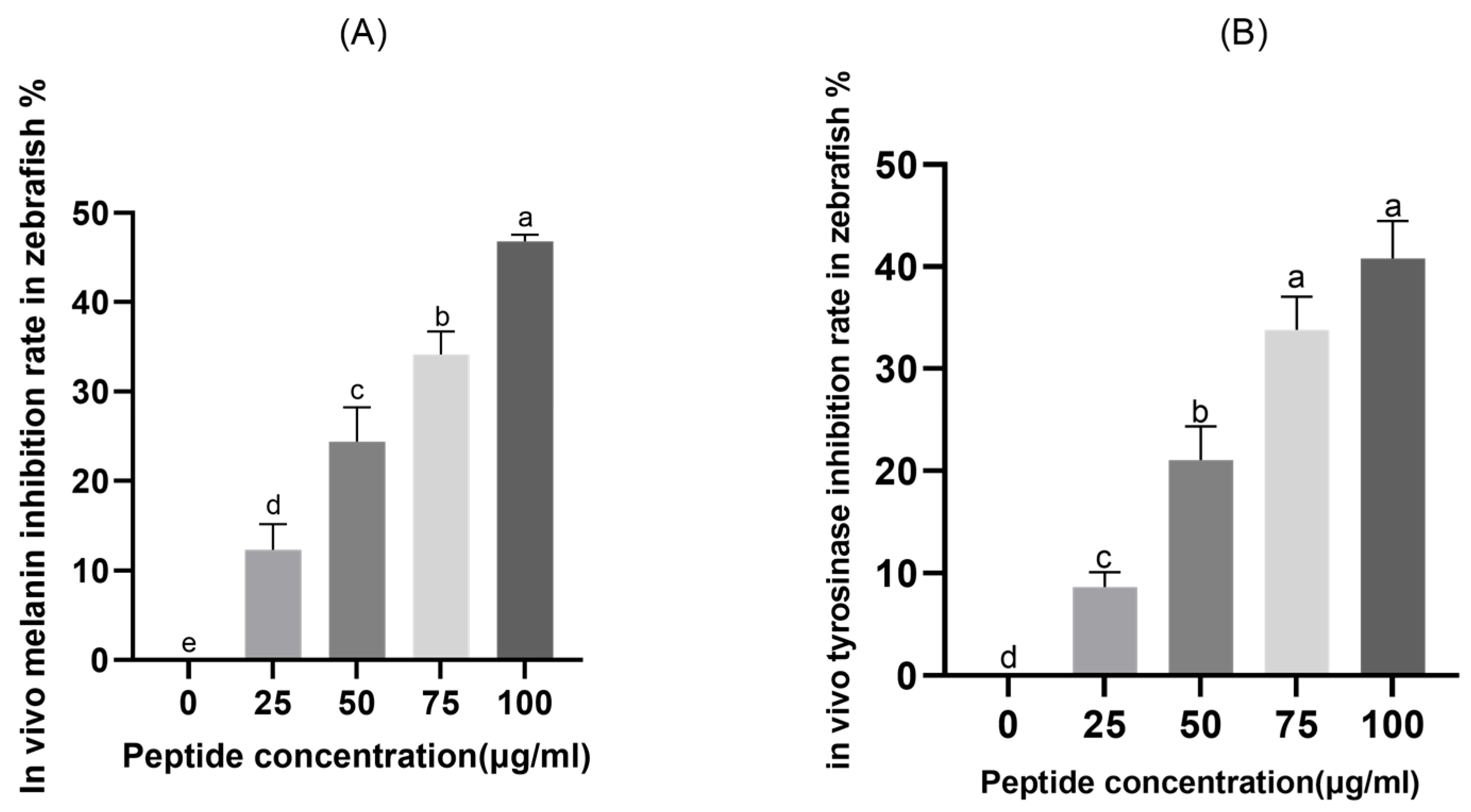

2.6. In Vivo Skin-Whitening Efficacy of CHAH in Zebrafish Embryos

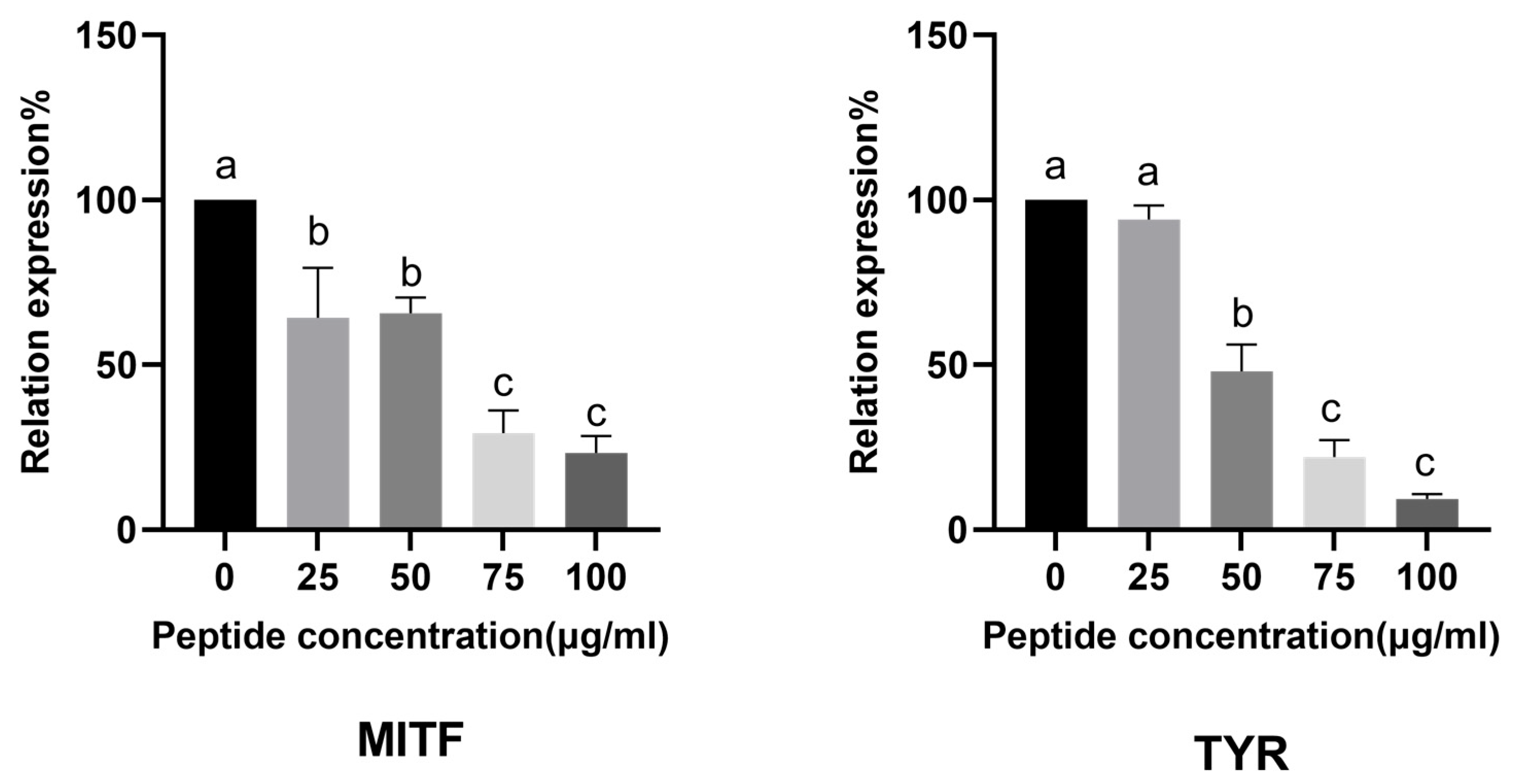

2.7. Skin-Whitening Mechanism of CHAH

2.7.1. CHAH Downregulates Melanogenesis-Related Genes Expression in B16 Cells

2.7.2. CHAH Downregulates Melanogenesis-Related Genes Expression in Zebrafish

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials

4.2. Preparation of CHAH

4.3. Antioxidant Activity Assays

4.4. Determination of Sialic Acid Content

4.5. N-Glycan Profiling of CHAH

4.6. Inhibitory Effect of CHAH on Tyrosinase Activity

4.7. Effect of CHAH on Melanogenesis in B16 Cells

4.7.1. Cell Culture of B16 Melanoma Cells

4.7.2. Determination of Melanin Content in B16 Melanoma Cells

4.7.3. Inhibition of Intracellular Tyrosinase Activity in B16 Melanoma Cells

4.7.4. Expression of Melanogenesis-Related Genes in B16 Melanoma Cells

4.8. In Vivo Skin-Whitening Activity of CHAH

4.8.1. Zebrafish Rearing and Survival Assay

4.8.2. Determination of Melanin Content and Tyrosinase Activity in Zebrafish

4.8.3. Expression of Melanogenesis-Related Genes in Zebrafish

4.9. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CHA | Chalaza |

| CHAH | CHA-derived glycopeptides |

| VC | L-ascorbic acid |

| PBS | Phosphate-buffered saline |

| DMSO | Dimethyl sulfoxide |

| FBS | Fetal bovine serum |

| DMEM | Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium |

| ECM | Embryo culture medium |

| MWCO | Molecular weight cut-off |

| MITF | Microphthalmia-associated Transcription Factor |

| TYR | Tyrosinase |

| TYRP1 | Tyrosinase-related protein 1 |

| TYRP2 | Tyrosinase-related protein 2 |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| TNF-α | Tumor necrosis factor-α |

| IL-1β | Interleukin-1β |

| SOD | Superoxide dismutase |

| GSH-Px | Glutathione peroxidase |

| Neu5Ac | N-acetylneuraminic acid |

| OPD | o-phenylenediamine |

| HPLC | High-Performance Liquid Chromatography |

| DSA-FACE | DNA sequencer-assisted fluorophore-assisted carbohydrate electrophoresis |

| RT-PCR | Reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction |

| CCK-8 | Cell Counting Kit-8 |

| DPPH | 1,1-Diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl |

| ABTS | 2,2′-Azinobis-(3-ethylbenzthiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) |

| ANOVA | One-way analysis of variance |

| DH | Degree of hydrolysis |

| hpf | Hours post-fertilization |

| TAA | Thioacetamide |

References

- Kawakami, A.; Fisher, D.E. Key discoveries in melanocyte development. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2011, 131, E2–E4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hida, T.; Kamiya, T.; Kawakami, A.; Ogino, J.; Sohma, H.; Uhara, H.; Jimbow, K. Elucidation of melanogenesis cascade for identifying pathophysiology and therapeutic approach of pigmentary disorders and melanoma. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 6129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lynde, C.B.; Kraft, J.N.; Lynde, C.W. Topical treatments for melasma and postinflammatory hyperpigmentation. Ski. Ther. Lett. 2006, 11, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Pillaiyar, T.; Manickam, M.; Jung, S.-H. Downregulation of melanogenesis: Drug discovery and therapeutic options. Drug Discov. Today 2017, 22, 282–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, R.; Ko, H.J.; Kim, K.; Sohn, Y.; Min, S.Y.; Kim, J.A.; Na, D.; Yeon, J.H. Anti-melanogenic effects of extracellular vesicles derived from plant leaves and stems in mouse melanoma cells and human healthy skin. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2020, 9, 1703480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, T.; Hearing, V.J. Direct interaction of tyrosinase with Tyrp1 to form heterodimeric complexes in vivo. J. Cell Sci. 2007, 120, 4261–4268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, W.; Deng, F.; Liu, X.; Yin, X.; Qiu, X.; Yang, J.; Yang, W.; Zhang, X.; Lian, J.; Fan, Q.; et al. Edible bird’s nest peptide (EBNP) with high whitening activity: Sequences analysis, whitening activity characterization and molecular docking study. J. Funct. Foods 2024, 123, 106617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Qu, L.; Li, H.; He, J.; Wang, L.; Fang, Y.; Yan, X.; Yang, Q.; Peng, B.; Wu, W.; et al. Advances in biomedical functions of natural whitening substances in the treatment of skin pigmentation diseases. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 2308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briganti, S.; Camera, E.; Picardo, M. Chemical and instrumental approaches to treat hyperpigmentation. Pigment Cell Res. 2003, 16, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamford, N.P.J. Stability, transdermal penetration, and cutaneous effects of ascorbic acid and its derivatives. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2012, 11, 310–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Huang, L.; Zhang, C.; Xie, P.; Cheng, J.; Wang, X.; Liu, L. Skin-care functions of peptides prepared from Chinese quince seed protein: Sequences analysis, tyrosinase inhibition and molecular docking study. Ind. Crops Prod. 2020, 148, 112331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qorbani, A.; Mubasher, A.; Sarantopoulos, G.P.; Nelson, S.; Fung, M.A. Exogenous Ochronosis (EO): Skin lightening cream causing rare caviar-like lesion with banana-like pigments; review of literature and histological comparison with endogenous counterpart. Autops. Case Rep. 2020, 10, e2020197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujimoto, N.; Onodera, H.; Mitsumori, K.; Tamura, T.; Maruyama, S.; Ito, A. Changes in thyroid function during development of thyroid hyperplasia induced by kojic acid in F344 rats. Carcinogenesis 1999, 20, 1567–1572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mishra, P.; Ahsan, F.; Mahmood, T.; Bano, S.; Ansari, V.A.; Yadav, J.; Ansari, J.A.; Khan, M.M.U. Acute and Subacute Toxicity Study of α-Arbutin: An In Vivo Evidence. J. Appl. Toxicol. 2025, 45, 2020–2041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Chen, S.; Li, L.; Zeng, Y.; Hu, X. The hypopigmentation mechanism of tyrosinase inhibitory peptides derived from food proteins: An overview. Molecules 2022, 27, 2710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gǎlbǎu, C.-Ş.; Irimie, M.; Neculau, A.E.; Dima, L.; Pogačnik da Silva, L.; Vârciu, M.; Badea, M. The Potential of Plant Extracts Used in Cosmetic Product Applications—Antioxidants Delivery and Mechanism of Actions. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, W.; Liu, X.; Fan, Q.; Lian, J.; Guo, B. Study of the antiaging effects of bird’s nest peptide based on biochemical, cellular, and animal models. J. Funct. Foods 2023, 103, 105479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, P.; Miao, J.; Liao, W.; Huang, C.; Chen, B.; Li, Y.; Wang, X.; Yu, Y.; Liang, X.; Zhao, H.; et al. Rapid screening of novel tyrosinase inhibitory peptides from a pearl shell meat hydrolysate by molecular docking and the anti-melanin mechanism. Food Funct. 2023, 14, 1446–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devita, L.; Lioe, H.N.; Nurilmala, M.; Suhartono, M.T. The Bioactivity Prediction of Peptides from Tuna Skin Collagen Using Integrated Method Combining In Vitro and In Silico. Foods 2021, 10, 2739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morakul, B.; Teeranachaideekul, V.; Wongrakpanich, A.; Leanpolchareanchai, J. The evidence from in vitro primary fibroblasts and a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial of tuna collagen peptides intake on skin health. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2024, 23, 4255–4267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byun, K.A.; Lee, S.Y.; Oh, S.; Batsukh, S.; Jang, J.W.; Lee, B.J.; Rheu, K.M.; Li, S.; Jeong, M.S.; Son, K.H.; et al. Fermented Fish Collagen Attenuates Melanogenesis via Decreasing UV-Induced Oxidative Stress. Mar. Drugs 2024, 22, 421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kose, A.; Oncel, S.S. Design of melanogenesis regulatory peptides derived from phycocyanin of the microalgae Spirulina platensis. Peptides 2022, 152, 170783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bodurlar, Y.; Caliskan, M. Inhibitory activity of soybean (Glycine max L. Merr.) Cell Culture Extract on tyrosinase activity and melanin formation in alpha-melanocyte stimulating Hormone-Induced B16-F10 melanoma cells. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2022, 49, 7827–7836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Wu, Q.; Yang, T.; Yang, F.; Guo, T.; Zhou, Y.; Han, S.; Luo, Y.; Guo, T.; Luo, F.; et al. Bioactive peptide F2d isolated from rice residue exerts antioxidant effects via Nrf2 signaling pathway. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2021, 2021, 2637577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vichit, W.; Saewan, N. Anti-Oxidant and Anti-Aging Activities of Callus Culture from Three Rice Varieties. Cosmetics 2022, 9, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fossa Shirata, M.M.; Maia Campos, P.M.B.G. Sunscreens and cosmetic formulations containing ascorbyl tetraisopalmitate and rice peptides for the improvement of skin photoaging: A double-blind, randomized placebo-controlled clinical study. Photochem. Photobiol. 2021, 97, 805–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, L.; Wang, L.; Liu, C.; Liang, Y.; Lin, Q. Bioactive peptides from foods: Production, function, and application. Food Funct. 2021, 12, 7108–7125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabl, A.; Spadaro, J.V.; Zoughaib, A. Environmental impacts and costs of solid waste: A comparison of landfill and incineration. Waste Manag. Res. 2008, 26, 147–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, J.; Hu, J.; Xiao, J.; Li, S.; Wang, B.; Wang, J.; Geng, F. Integrated landscape of chicken egg chalaza proteomics. Poult. Sci. 2024, 103, 103629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, C.-J.; Tseng, J.-K.; Wang, S.-Y.; Lin, Y.-L.; Wu, Y.-H.S.; Chen, J.-W.; Chen, Y.-C. Ameliorative effects of functional chalaza hydrolysates prepared from protease-A digestion on cognitive dysfunction and brain oxidative damages. Poult. Sci. 2020, 99, 2819–2832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.-L.; Lu, C.-F.; Wu, Y.-H.S.; Yang, K.-T.; Yang, W.-Y.; Chen, J.-W.; Tseng, J.-K.; Chen, Y.-C. Protective effects of crude chalaza hydrolysates against liver fibrogenesis via antioxidation, anti-inflammation/anti-fibrogenesis, and apoptosis promotion of damaged hepatocytes. Poult. Sci. 2021, 100, 101175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Najafian, L.; Babji, A. A review of fish-derived antioxidant and antimicrobial peptides: Their production, assessment, and applications. Peptides 2012, 33, 178–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takada, H.; Katoh, T.; Katayama, T. Sialylated O -Glycans from Hen Egg White Ovomucin are Decomposed by Mucin-degrading Gut Microbes. J. Appl. Glycosci. 2020, 67, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laroy, W.; Contreras, R.; Callewaert, N. Glycome mapping on DNA sequencing equipment. Nat. Protoc. 2006, 1, 397–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varki, A.; Cummings, R.D.; Esko, J.D.; Freeze, H.H.; Stanley, P.; Marth, J.D.; Bertozzi, C.R.; Hart, G.W.; Etzler, M.E. Symbol nomenclature for glycan representation. Proteomics 2009, 9, 5398–5399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.J.; Kim, K.S.; Yu, B.J. Optimization of antioxidant and skin-whitening compounds extraction condition from Tenebrio molitor larvae (mealworm). Molecules 2018, 23, 2340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Meng, F.; Sun, T.; Hao, Z.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, Y.; Ding, Y. Peptides from Dalian Stichopus japonicus: Antioxidant Activity and Melanogenesis Inhibition In Vitro Cell Models and In Vivo Zebrafish Models Guided by Molecular Docking Screening. Mar. Biotechnol. 2025, 27, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pillaiyar, T.; Manickam, M.; Jung, S.-H. Recent development of signaling pathways inhibitors of melanogenesis. Cell. Signal. 2017, 40, 99–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyman, M.; Walsdorf, R.E.; Wix, S.N.; Gill, J.G. The metabolism of melanin synthesis—From melanocytes to melanoma. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2024, 37, 438–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronin, J.C.; Wunderlich, J.; Loftus, S.K.; Prickett, T.D.; Wei, X.; Ridd, K.; Vemula, S.; Burrell, A.S.; Agrawal, N.S.; Lin, J.C.; et al. Frequent mutations in the MITF pathway in melanoma. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2009, 22, 435–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roider, E.; Lakatos, A.I.T.; McConnell, A.M.; Wang, P.; Mueller, A.; Kawakami, A.; Tsoi, J.; Szabolcs, B.L.; Ascsillán, A.A.; Suita, Y.; et al. MITF regulates IDH1, NNT, and a transcriptional program protecting melanoma from reactive oxygen species. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 21527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Zhang, J.; Peng, Z. Tyrosinase inhibitory mechanism of pyrimidine-thiols and their potential application in the anti-browning of fresh-cut apples. Food Chem. 2025, 493, 146057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahuja, K.; Raju, S.; Dahiya, S.; Motiani, R.K. ROS and calcium signaling are critical determinant of skin pigmentation. Cell Calcium 2025, 125, 102987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, D.; Lee, K.J.; Kim, Y.; Kim, M.; Ju, H.M.; Kim, M.J.; Choi, D.H.; Choi, J.; Kim, S.; Kang, D.; et al. A Basic Domain-Derived Tripeptide Inhibits MITF Activity by Reducing its Binding to the Promoter of Target Genes. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2021, 141, 2459–2469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, L.; Xiong, H.; Huang, X.; Guyonnet, V.; Ma, M.; Chen, X.; Zheng, Y.; Wang, L.; Hu, G. Identification and molecular mechanisms of novel antioxidant peptides from two sources of eggshell membrane hydrolysates showing cytoprotection against oxidative stress: A combined in silico and in vitro study. Food Res. Int. 2022, 157, 111266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yubolphan, R.; Phongsiri, K.; Mongkhammee, N.; Pidech, J.; Roytrakul, S.; Suwattanasophon, C.; Choowongkomon, K.; Daduang, S.; Khunkitti, W.; Jangpromma, N. Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Hen Egg White Hydrolysate and Its Specific Peptides IS8, PA11, and PK8 on LPS-Induced Macrophage Inflammation. Food Sci. Nutr. 2025, 13, e70713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.T.; Lin, Y.L.; Lin, Y.X.; Wang, S.Y.; Wu, Y.H.S.; Chou, C.H.; Fu, S.G.; Chen, Y.C. Protective effects of antioxidant egg-chalaza hydrolysates against chronic alcohol consumption-induced liver steatosis in mice. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2018, 99, 2300–2310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ak, T.; Gülçin, I. Antioxidant and radical scavenging properties of curcumin. Chem.-Biol. Interact. 2008, 174, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, Y.; Cao, Y.; Guo, S.; Xu, J.; Li, Z.; Wang, J.; Xue, C. Purification and identification of α 2–3 linked sialoglycoprotein and α 2–6 linked sialoglycoprotein in edible bird’s nest. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2015, 240, 389–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín, M.J.; Vázquez, E.; Rueda, R. Application of a sensitive fluorometric HPLC assay to determine the sialic acid content of infant formulas. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2007, 387, 2943–2949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

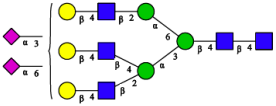

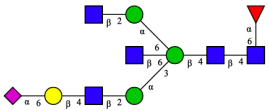

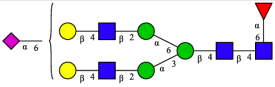

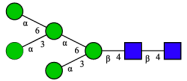

| Peak | N-Glycan Name | N-Glycan Structure |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | A3G3S3(2,6) |  |

| 2 | A2G2S2(2,6) |  |

| 3 | A2G2S1(2,6)S1(2,3) |  |

| 4 | FA2G2S2(2,3) |  |

| A4G4S2(2,3)S1(2,6) |  | |

| 5 | A2G1S1(2,6)[3] |  |

| A4F(3)G4S1(2,3)S2(2,6) |  | |

| 6 | A3G3S1(2,3)S1(2,6) |  |

| 7 | A2G2S1(2,6) |  |

| FA2BG1S1(2,6)[3] |  | |

| 8 | FA2G2S1(2,6) |  |

| Man5 |  | |

| 9 | Man6 |  |

| 10 | FA2G1[6] |  |

| 11 | FA2G1[3] |  |

| 12 | A2G2 |  |

| FA2BG1[6] |  | |

| 13 | FA2BG2 |  |

| 14 | A3G3[2,4] |  |

| Matter | IC50 |

|---|---|

| CHAH | 13.80 mg/mL |

| Edible Bird’s Nest Peptide | 7.55 mg/mL |

| Arbutin | 1.09 mM |

| L-Ascorbic Acid | 12.5 μM |

| Kojic Acid | ~2.8 μM |

| Gene | Upstream Primers (5′-3′) | Downstream Primers (5′-3′) |

|---|---|---|

| β-actin | GTGACGTTGACATCCGTAAAGA | GCCGGACTCATCGTACTCC |

| MITF | CCAACAGCCCTATGGCTATGC | CTGGGCACTCACTCTCTGC |

| TYR | CAAAGGGGTGGATGACCGTG | AACTTACAGTTTCCGCAGTTGA |

| TYRP1 | CCCCTAGCCTATATCTCCCTTTT | TACCATCGTGGGGATAATGGC |

| TYRP2 | CTTGGGGTTGCTGGCTTTTC | CGCTGAAGAGTTCCACCTGT |

| Gene | Upstream Primers (5′-3′) | Downstream Primers (5′-3′) |

|---|---|---|

| β-actin | TCGAGCATGGAGATGGGAACC | CTCGTGGATACCGCAAGATTC |

| MITF | GGATACTTCATGGTGCCCTT | TCAGGAACTCCTGCACAAAC |

| TYR | CCTTCCCAGTCCTGACATGT | GTTCGTCCATACTGCTGCTG |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ma, Y.; Jiang, Z.; Jin, X.; Wu, J.; Gao, M. Preparation and Whitening Activity of Sialoglycopeptide of Chalaza from Liquid Egg Process. Molecules 2026, 31, 59. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010059

Ma Y, Jiang Z, Jin X, Wu J, Gao M. Preparation and Whitening Activity of Sialoglycopeptide of Chalaza from Liquid Egg Process. Molecules. 2026; 31(1):59. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010059

Chicago/Turabian StyleMa, Yanzhao, Ziyi Jiang, Xinyi Jin, Jianrong Wu, and Minjie Gao. 2026. "Preparation and Whitening Activity of Sialoglycopeptide of Chalaza from Liquid Egg Process" Molecules 31, no. 1: 59. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010059

APA StyleMa, Y., Jiang, Z., Jin, X., Wu, J., & Gao, M. (2026). Preparation and Whitening Activity of Sialoglycopeptide of Chalaza from Liquid Egg Process. Molecules, 31(1), 59. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010059