Photocatalytic Synthesis of 3,4-Dihydroquinolone from Tetrahydroquinolines by a High-Throughput Microfluidic System and Insights into the Role of Organic Bases

Abstract

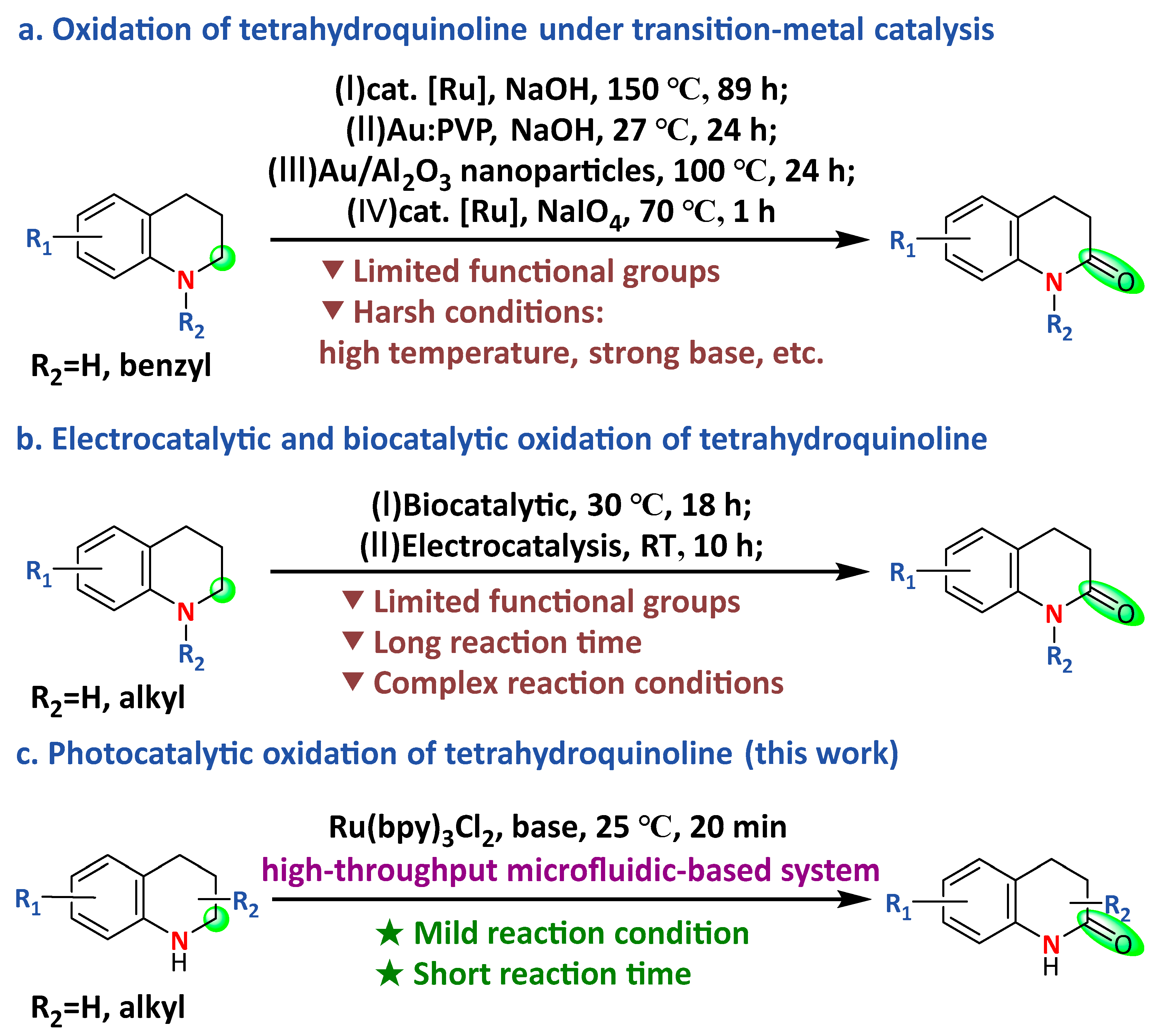

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

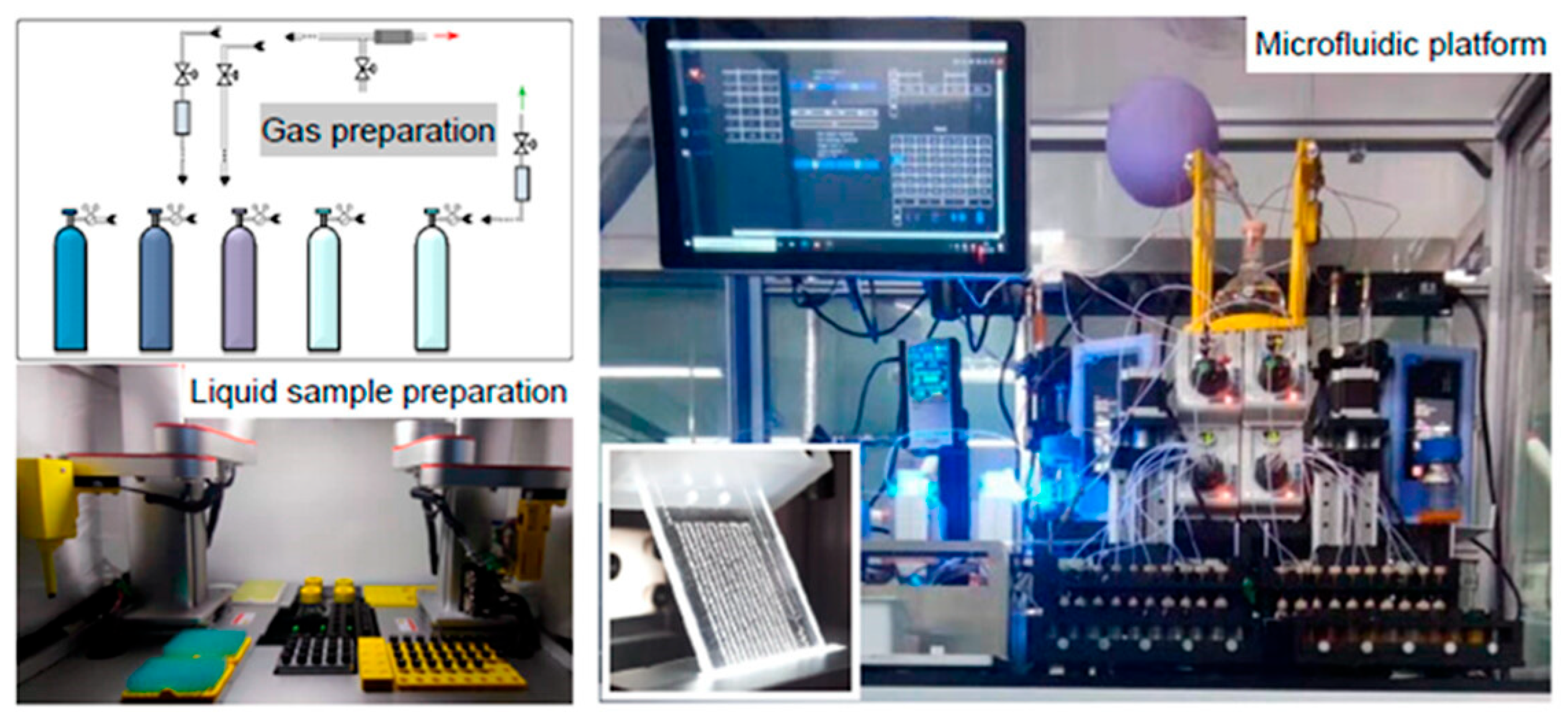

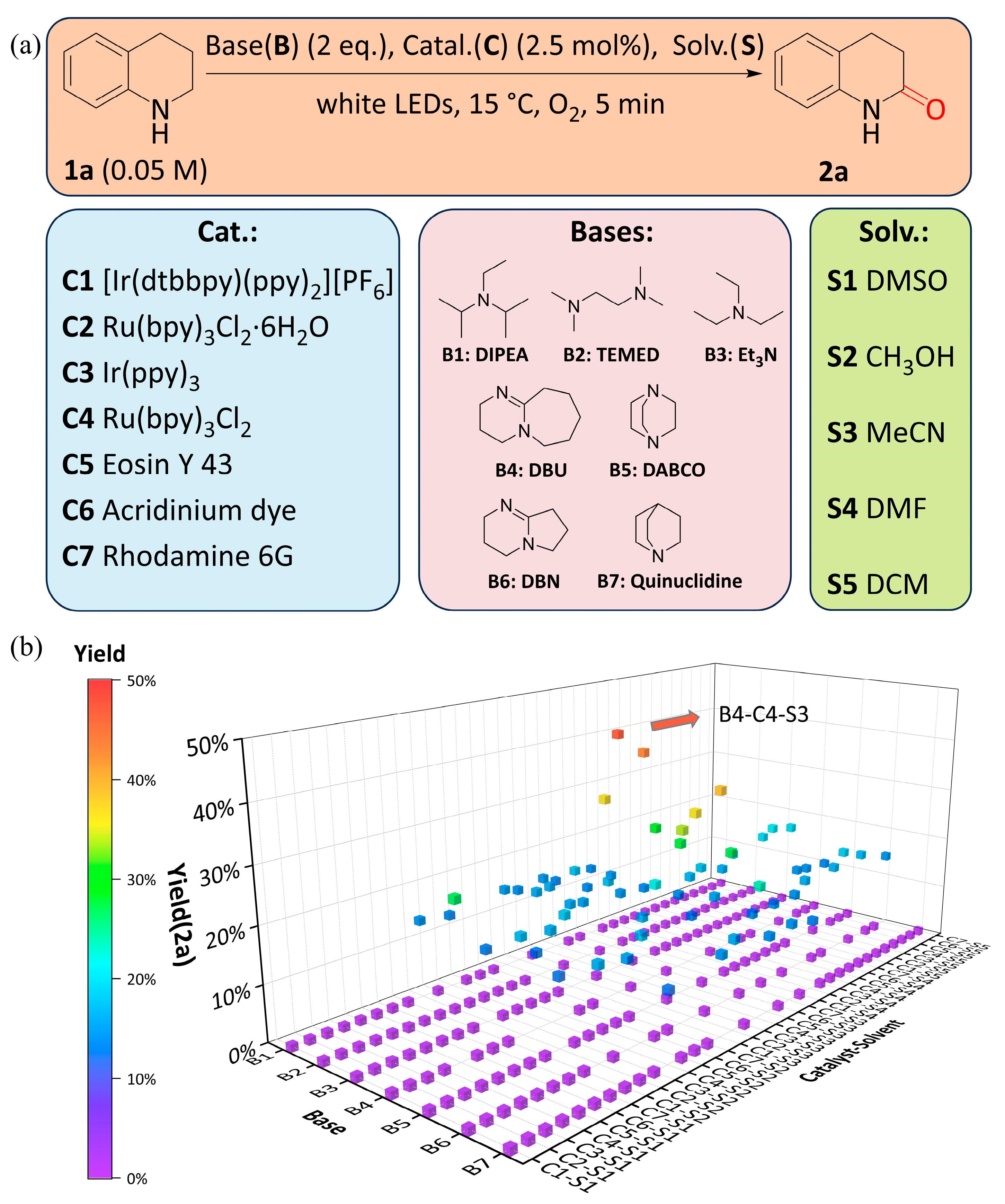

2.1. The Optimization of Reaction Conditions

2.1.1. The Optimization of Discrete Variables

2.1.2. The Optimization of Continuous Variables

2.2. The Substrate Scope of the Reaction

2.3. The Mechanistic Study of the Reaction

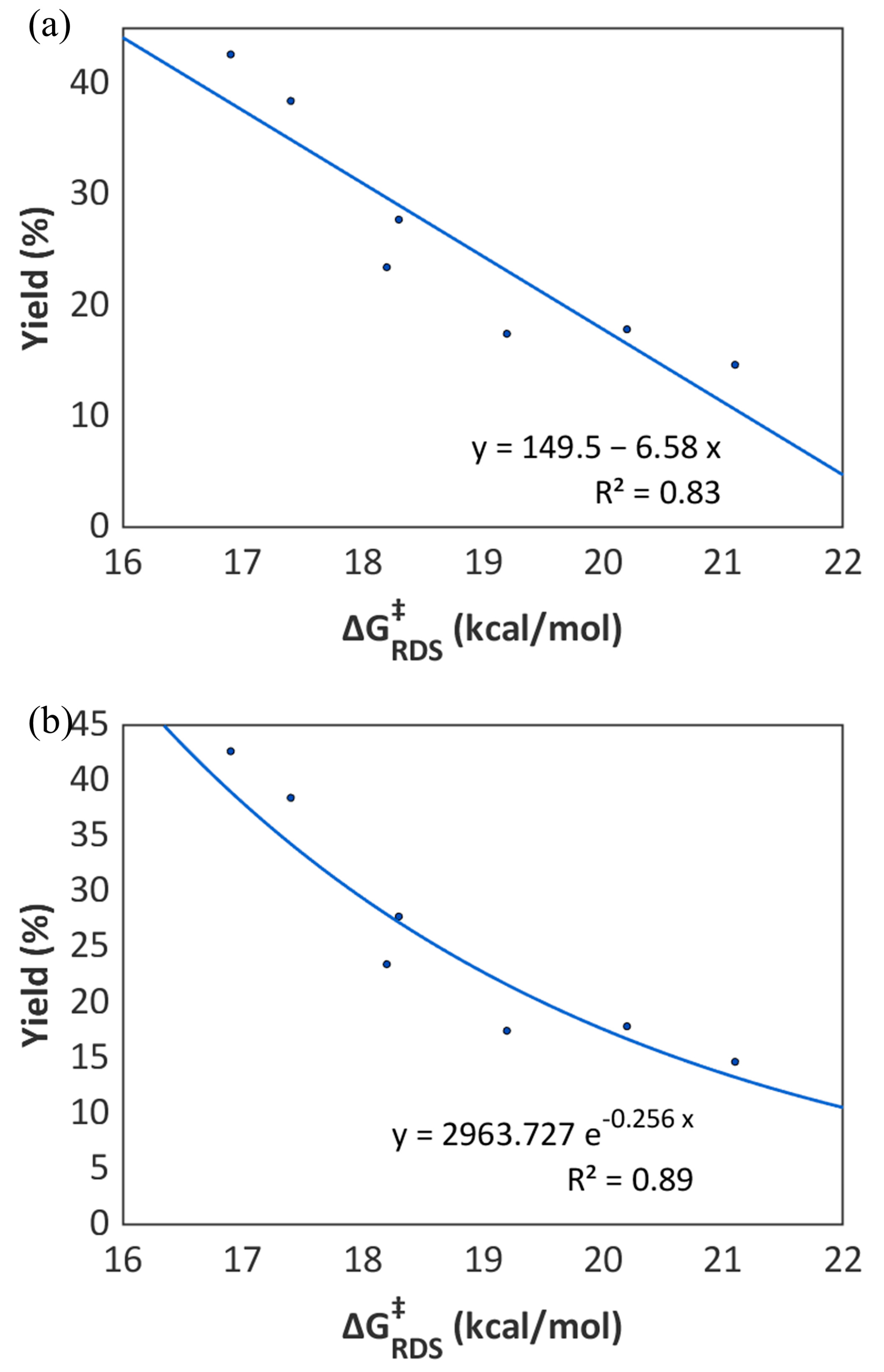

2.4. The Role of Organic Bases

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. General Methods

3.2. Experimental Procedures

3.3. Reaction Conditions Screening

3.3.1. System

3.3.2. Machine Learning

3.3.3. Screening of Discrete Variables

3.3.4. Screening of Continuous Variables

3.4. Computational Details

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fujita, K.; Takahashi, Y.; Owaki, M.; Yamamoto, K.; Yamaguchi, R. Synthesis of Five-, Six-, and Seven-Membered Ring Lactams by cp*Rh Complex-Catalyzed Oxidative N-Heterocyclization of Amino Alcohols. Org. Lett. 2004, 6, 2785–2788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Q.; Yin, L.; Hartmann, R.W. Selective Dual Inhibitors of CYP19 and CYP11B2: Targeting Cardiovascular Diseases Hiding in the Shadow of Breast Cancer. J. Med. Chem. 2012, 55, 7080–7089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, X.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Qiu, Y.; Yu, M.; Xu, X.; Liu, X.; Liu, B.-F.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, G. Synthesis and Biological Evaluation of Fused Tricyclic Heterocycle Piperazine (Piperidine) Derivatives as Potential Multireceptor Atypical Antipsychotics. J. Med. Chem. 2018, 61, 10017–10039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, L.; Hao, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Q. NIS-Mediated Oxidative Arene C(Sp2)–H Amidation toward 3,4-Dihydro-2(1H)-Quinolinone, Phenanthridone, and N-Fused Spirolactam Derivatives. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2019, 17, 6762–6770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, T.-T.; Huang, P.-T.; Chen, B.-H.; Zhong, Y.-J.; Han, B.; Peng, C.; Zhan, G.; Huang, W.; Zhao, Q. Construction of 3,4-Dihydroquinolone Derivatives through Pd-Catalyzed [4+2] Cycloaddition of Vinyl Benzoxazinanones with α-Alkylidene Succinimides. J. Org. Chem. 2024, 89, 3279–3291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, A. Cilostazol. Pract. Diabetes Int. 2011, 28, 43–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- See, Y.Y.; Dang, T.T.; Chen, A.; Seayad, A.M. Concise Synthesis of Vesnarinone and Its Analogues by Using Pd-Catalyzed C–N Bond-Forming Reactions. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2014, 2014, 7405–7412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, R.D.; MacCoss, M.; Lawson, A.D.G. Rings in Drugs. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 57, 5845–5859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, M.; Pang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, Y. Pd-Catalyzed Sequential β-C(Sp 3)–H Arylation and Intramolecular Amination of δ-C(Sp 2)–H Bonds for Synthesis of Quinolinones via an N,O-Bidentate Directing Group. Chem. Commun. 2016, 52, 7043–7046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Kashef, D.H.; Daletos, G.; Plenker, M.; Hartmann, R.; Mándi, A.; Kurtán, T.; Weber, H.; Lin, W.; Ancheeva, E.; Proksch, P. Polyketides and a Dihydroquinolone Alkaloid from a Marine-Derived Strain of the Fungus Metarhizium marquandii. J. Nat. Prod. 2019, 82, 2460–2469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthukrishnan, I.; Sridharan, V.; Menéndez, J.C. Progress in the Chemistry of Tetrahydroquinolines. Chem. Rev. 2019, 119, 5057–5191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.-Y.; Huang, Y.-H.; Zhou, J.; Wang, P. Pd-Catalyzed Site-Selective Borylation of Simple Arenes via Thianthrenation†. Chin. J. Chem. 2020, 38, 1269–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, T.; Lückemeier, L.; Daniliuc, C.; Glorius, F. Ru-NHC-Catalyzed Asymmetric Hydrogenation of 2-Quinolones to Chiral 3,4-Dihydro-2-Quinolones. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 23193–23196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kikugawa, Y.; Nagashima, A.; Sakamoto, T.; Miyazawa, E.; Shiiya, M. Intramolecular Cyclization with Nitrenium Ions Generated by Treatment of N-Acylaminophthalimides with Hypervalent Iodine Compounds: Formation of Lactams and Spiro-Fused Lactams. J. Org. Chem. 2003, 68, 6739–6744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Egle, B.; de Muñoz, J.M.; Alonso, N.; De Borggraeve, W.M.; de la Hoz, A.; Díaz-Ortiz, A.; Alcázar, J. First Example of Alkyl–Aryl Negishi Cross-Coupling in Flow: Mild, Efficient and Clean Introduction of Functionalized Alkyl Groups. J. Flow Chem. 2014, 4, 22–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, Y.; Park, Y.; Kim, Y.B.; Kim, D.; Chang, S. Revisiting Arene C(Sp2)−H Amidation by Intramolecular Transfer of Iridium Nitrenoids: Evidence for a Spirocyclization Pathway. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 13565–13569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, T.; Mazumdar, W.; Ford, R.L.; Jana, N.; Izar, R.; Wink, D.J.; Driver, T.G. Oxidation of Nonactivated Anilines to Generate N-Aryl Nitrenoids. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 4456–4463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, S.; Kant, R.; Kuram, M.R. Metal-Free Transfer Hydrogenation/Cycloaddition Cascade of Activated Quinolines and Isoquinolines with Tosyl Azides. Chem. Commun. 2023, 59, 7088–7091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preedasuriyachai, P.; Chavasiri, W.; Sakurai, H. Aerobic Oxidation of Cyclic Amines to Lactams Catalyzed by PVP-Stabilized Nanogold. Synlett 2011, 2011, 1121–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khusnutdinova, J.R.; Ben-David, Y.; Milstein, D. Oxidant-Free Conversion of Cyclic Amines to Lactams and H 2 Using Water As the Oxygen Atom Source. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 2998–3001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Kataoka, K.; Yatabe, T.; Yamaguchi, K.; Mizuno, N. Supported Gold Nanoparticles for Efficient α-Oxygenation of Secondary and Tertiary Amines into Amides. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 7212–7217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konwar, M.; Das, T.; Das, A. Cyclometalated Ruthenium Catalyst Enables Selective Oxidation of N-Substituted Tetrahydroquinolines to Lactams. Org. Lett. 2024, 26, 1184–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, D.; Zhou, X.; Cui, B.; Han, W.; Wan, N.; Chen, Y. Biocatalytic α-Oxidation of Cyclic Amines and N -Methylanilines for the Synthesis of Lactams and Formamides. ChemCatChem 2017, 9, 937–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.-F.; Long, C.-J.; Guan, Z.; He, Y.-H. Selective Electrochemical Oxidation of Tetrahydroquinolines to 3,4-Dihydroquinolones. Green Chem. 2022, 24, 4581–4587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Wan, Q.; Badu-Tawiah, A.K. Picomole-Scale Real-Time Photoreaction Screening: Discovery of the Visible-Light-Promoted Dehydrogenation of Tetrahydroquinolines under Ambient Conditions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 9345–9349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Riemer, D.; Schilling, W.; Kollmann, J.; Das, S. Visible-Light-Mediated Efficient Metal-Free Catalyst for α-Oxygenation of Tertiary Amines to Amides. ACS Catal. 2018, 8, 6659–6664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aganda, K.C.C.; Hong, B.; Lee, A. Aerobic α-Oxidation of N-Substituted Tetrahydroisoquinolines to Dihydroisoquinolones via Organo-photocatalysis. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2019, 361, 1124–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xuan, J.; Xiao, W. Visible-light Photoredox Catalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 6828–6838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prier, C.K.; Rankic, D.A.; MacMillan, D.W.C. Visible Light Photoredox Catalysis with Transition Metal Complexes: Applications in Organic Synthesis. Chem. Rev. 2013, 113, 5322–5363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravelli, D.; Protti, S.; Fagnoni, M. Carbon–Carbon Bond Forming Reactions via Photogenerated Intermediates. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 9850–9913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzo, L.; Pagire, S.K.; Reiser, O.; König, B. Visible-light Photocatalysis: Does It Make a Difference in Organic Synthesis? Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 10034–10072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, H.; Chen, Y.; Huang, M.; Liu, T.; Wu, Y.-D.; Zhang, X. Exploring New Reactions with an Accessible High-Throughput Screening (Open-HTS) Chemical Robotic System. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2025, 29, 1423–1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Z.; Wan, C.; Jiang, H.; Wang, Y.; Xing, Y.; Wang, J.; Liu, Z.; Guo, X.; An, Y.; Han, W.; et al. Photocatalytic Acylation of Lysine Screened Using a Microfluidic-Based Chemical Robotic System. Green Chem. 2024, 26, 11238–11248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondo, M.; Wathsala, H.D.P.; Sako, M.; Hanatani, Y.; Ishikawa, K.; Hara, S.; Takaai, T.; Washio, T.; Takizawa, S.; Sasai, H. Exploration of Flow Reaction Conditions Using Machine-Learning for Enantioselective Organocatalyzed Rauhut–Currier and [3+2] Annulation Sequence. Chem. Commun. 2020, 56, 1259–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deringer, V.L.; Bartók, A.P.; Bernstein, N.; Wilkins, D.M.; Ceriotti, M.; Csányi, G. Gaussian Process Regression for Materials and Molecules. Chem. Rev. 2021, 121, 10073–10141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denzel, A.; Kästner, J. Gaussian Process Regression for Transition State Search. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2018, 14, 5777–5786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roucan, M.; Kielmann, M.; Connon, S.J.; Bernhard, S.S.R.; Senge, M.O. Conformational Control of Nonplanar Free Base Porphyrins: Towards Bifunctional Catalysts of Tunable Basicity. Chem. Commun. 2018, 54, 26–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandgude, A.L.; Dömling, A. Convergent Three-Component Tetrazole Synthesis. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2016, 2016, 2383–2387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, M.H.; Twilton, J.; MacMillan, D.W.C. Photoredox Catalysis in Organic Chemistry. J. Org. Chem. 2016, 81, 6898–6926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, D.; Ren, T.; Luo, Z.; Sun, F.; Han, Y.; Chen, K.; Zhang, X.; Zhou, M.; Gong, P.; Chao, M. Visible-Light-Induced Aerobic Epoxidation with Vitamin B2-Based Photocatalyst. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2023, 21, 4955–4961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frisch, M.J.; Trucks, G.W.; Schlegel, H.B.; Scuseria, G.E.; Robb, M.A.; Cheeseman, J.R.; Scalmani, G.; Barone, V.; Petersson, G.A.; Nakatsuji, H.; et al. Gaussian 16 Rev. C.01; Gaussian, Inc.: Wallingford, CT, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y.; Truhlar, D.G. The M06 Suite of Density Functionals for Main Group Thermochemistry, Thermochemical Kinetics, Noncovalent Interactions, Excited States, and Transition Elements: Two New Functionals and Systematic Testing of Four M06-Class Functionals and 12 Other Functionals. Theor. Chem. Account. 2008, 120, 215–241. [Google Scholar]

- Grimme, S.; Ehrlich, S.; Goerigk, L. Effect of the Damping Function in Dispersion Corrected Density Functional Theory. J. Comput. Chem. 2011, 32, 1456–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weigend, F.; Ahlrichs, R. Balanced Basis Sets of Split Valence, Triple Zeta Valence and Quadruple Zeta Valence Quality for H to Rn: Design and Assessment of Accuracy. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2005, 7, 3297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weigend, F. Accurate Coulomb-Fitting Basis Sets for H to Rn. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2006, 8, 1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marenich, A.V.; Cramer, C.J.; Truhlar, D.G. Universal Solvation Model Based on Solute Electron Density and on a Continuum Model of the Solvent Defined by the Bulk Dielectric Constant and Atomic Surface Tensions. J. Phys. Chem. B 2009, 113, 6378–6396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Ling, C.-H.; Au, C.-M.; Yu, W.-Y. Ruthenium-Catalyzed Intramolecular Arene C(Sp2)–H Amidation for Synthesis of 3,4-Dihydroquinolin-2(1 H)-Ones. Org. Lett. 2021, 23, 3310–3314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Shi, L.; Xing, Q.; Huang, K.-W.; Xia, C.; Li, F. Enabling CO Insertion into o -Nitrostyrenes beyond Reduction for Selective Access to Indolin-2-One and Dihydroquinolin-2-One Derivatives. ACS Catal. 2018, 8, 10340–10348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, D.; Zhang, S. Selective Reduction of Quinolinones Promoted by a SmI2/H2O/MeOH System. J. Org. Chem. 2022, 87, 8757–8763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, X.; Li, X.; Duan, S.; Du, Y.; Liu, T.; Fang, Y.; Chen, W.; Zhang, H.; Li, M.; Yang, X. Room Temperature Benzofused Lactam Synthesis Enabled by Cobalt(III)-Catalyzed C(Sp2)-H Amidation. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2021, 363, 1050–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linsenmeier, A.M.; Braje, W.M. Efficient One-Pot Synthesis of Dihydroquinolinones in Water at Room Temperature. Tetrahedron 2015, 71, 6913–6919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Wang, L.; Hu, F.; Xu, L.; Li, S.; Li, S.-S. Redox-Triggered Switchable Synthesis of 3,4-Dihydroquinolin-2(1 H)-One Derivatives via Hydride Transfer/N-Dealkylation/N-Acylation. Org. Lett. 2021, 23, 358–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bases | ΔGox. | ΔG0HAT | ΔG‡RDS | Yield (2a) 1 |

| B1 | −1.5 | 21.1 | 21.1 | 14.7% |

| B2 | −2.0 | 20.2 | 20.2 | 17.9% |

| B3 | 4.2 | 15.0 | 19.2 | 17.5% |

| B4 | 11.6 | 5.3 | 16.9 | 42.7% |

| B5 | −3.0 | 18.3 | 18.3 | 27.8% |

| B6 | 13.4 | 4.0 | 17.4 | 38.5% |

| B7 | 7.2 | 11.0 | 18.2 | 23.5% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ding, S.; Sun, T.-Y.; Jiang, H.; Wu, Y.-D.; Zhang, X. Photocatalytic Synthesis of 3,4-Dihydroquinolone from Tetrahydroquinolines by a High-Throughput Microfluidic System and Insights into the Role of Organic Bases. Molecules 2026, 31, 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010026

Ding S, Sun T-Y, Jiang H, Wu Y-D, Zhang X. Photocatalytic Synthesis of 3,4-Dihydroquinolone from Tetrahydroquinolines by a High-Throughput Microfluidic System and Insights into the Role of Organic Bases. Molecules. 2026; 31(1):26. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010026

Chicago/Turabian StyleDing, Shuyuan, Tian-Yu Sun, Heming Jiang, Yun-Dong Wu, and Xinhao Zhang. 2026. "Photocatalytic Synthesis of 3,4-Dihydroquinolone from Tetrahydroquinolines by a High-Throughput Microfluidic System and Insights into the Role of Organic Bases" Molecules 31, no. 1: 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010026

APA StyleDing, S., Sun, T.-Y., Jiang, H., Wu, Y.-D., & Zhang, X. (2026). Photocatalytic Synthesis of 3,4-Dihydroquinolone from Tetrahydroquinolines by a High-Throughput Microfluidic System and Insights into the Role of Organic Bases. Molecules, 31(1), 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010026