Pioneering Role of T.C. Merigan in the Treatment of Various Virus Infections

Abstract

1. Introduction

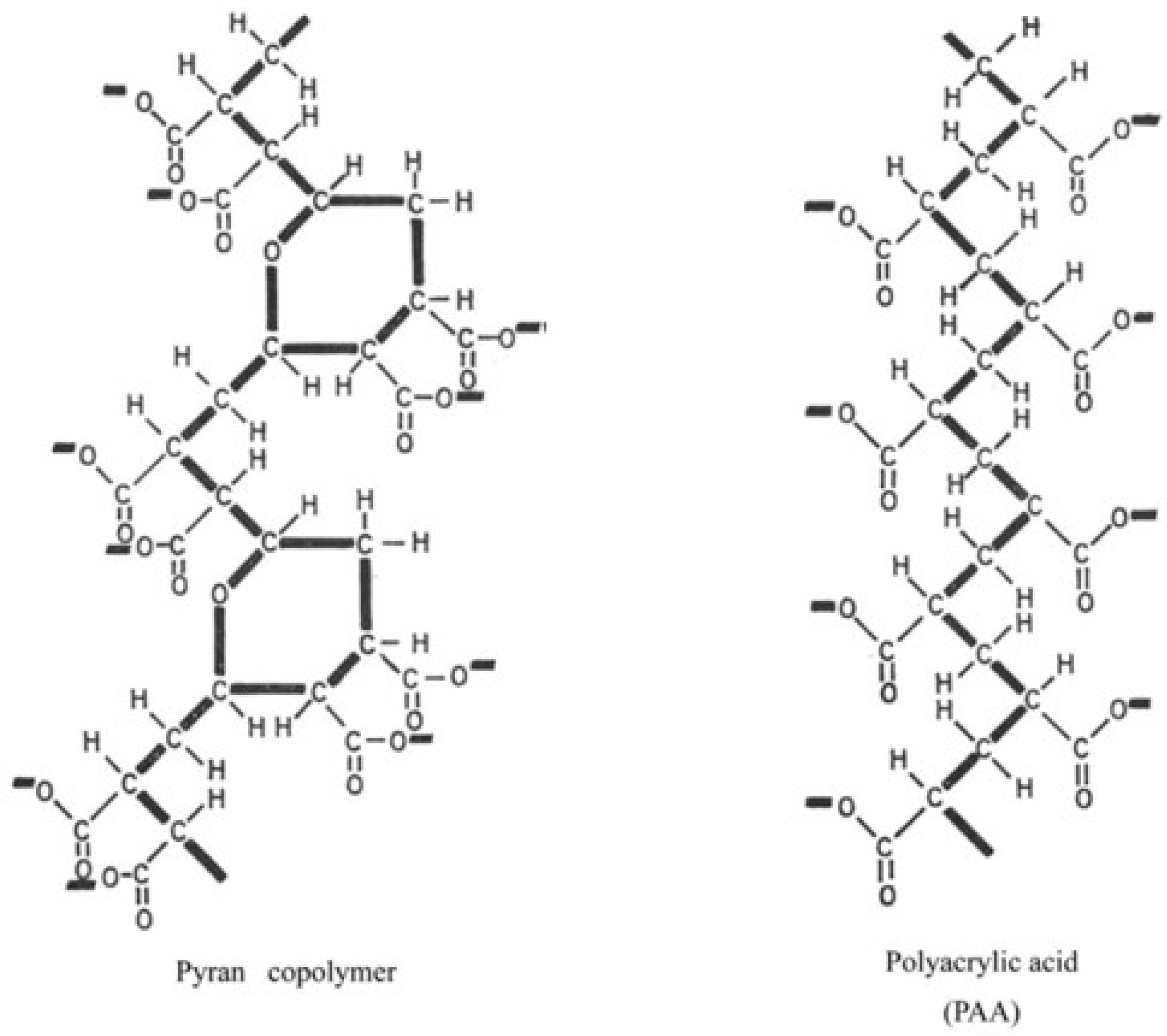

2. Pyran (Maleic Divinyl Ether) Copolymer

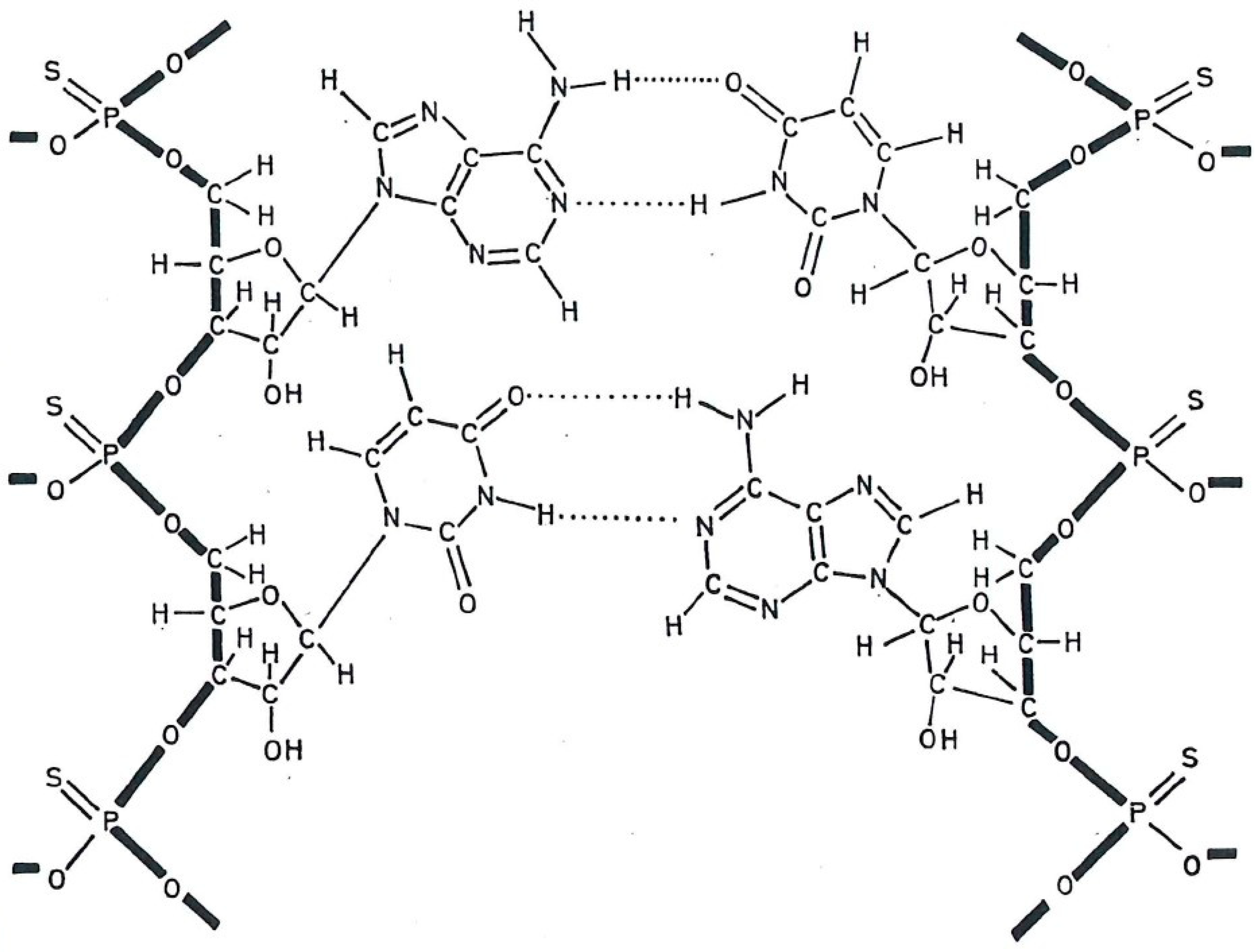

3. Thiophosphate-Substituted Polyribonucleotides

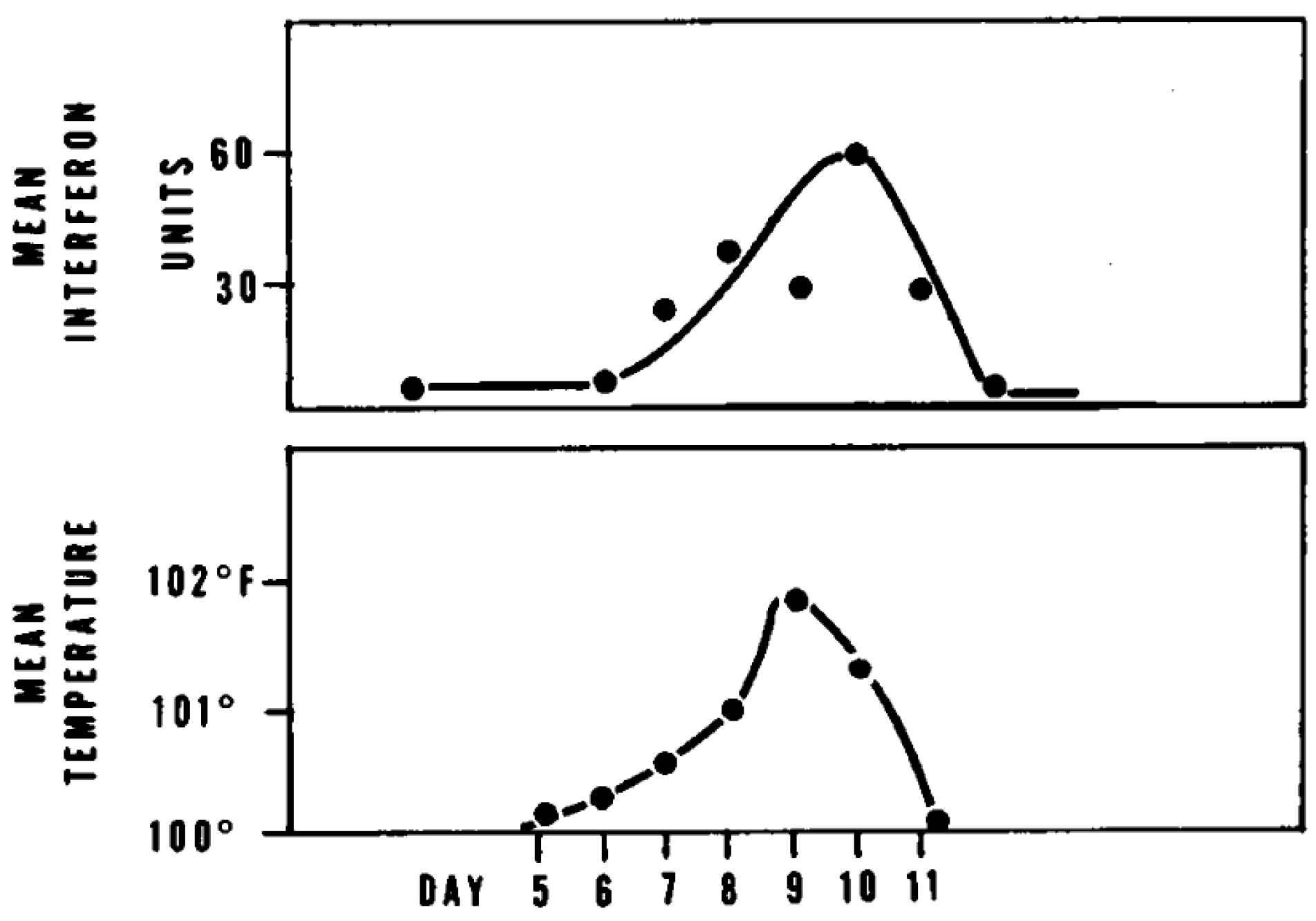

4. Host Defenses Against Viral Infections

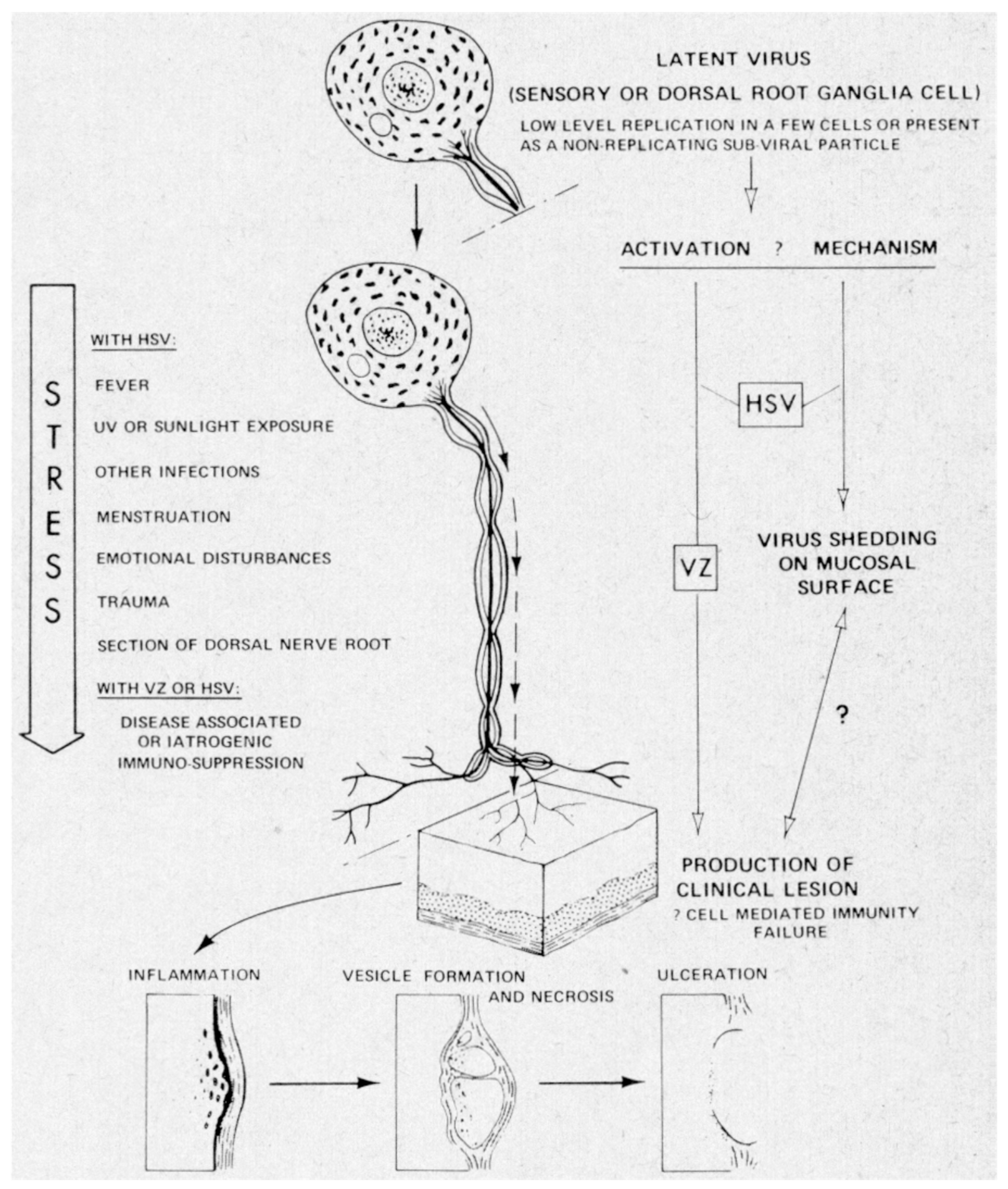

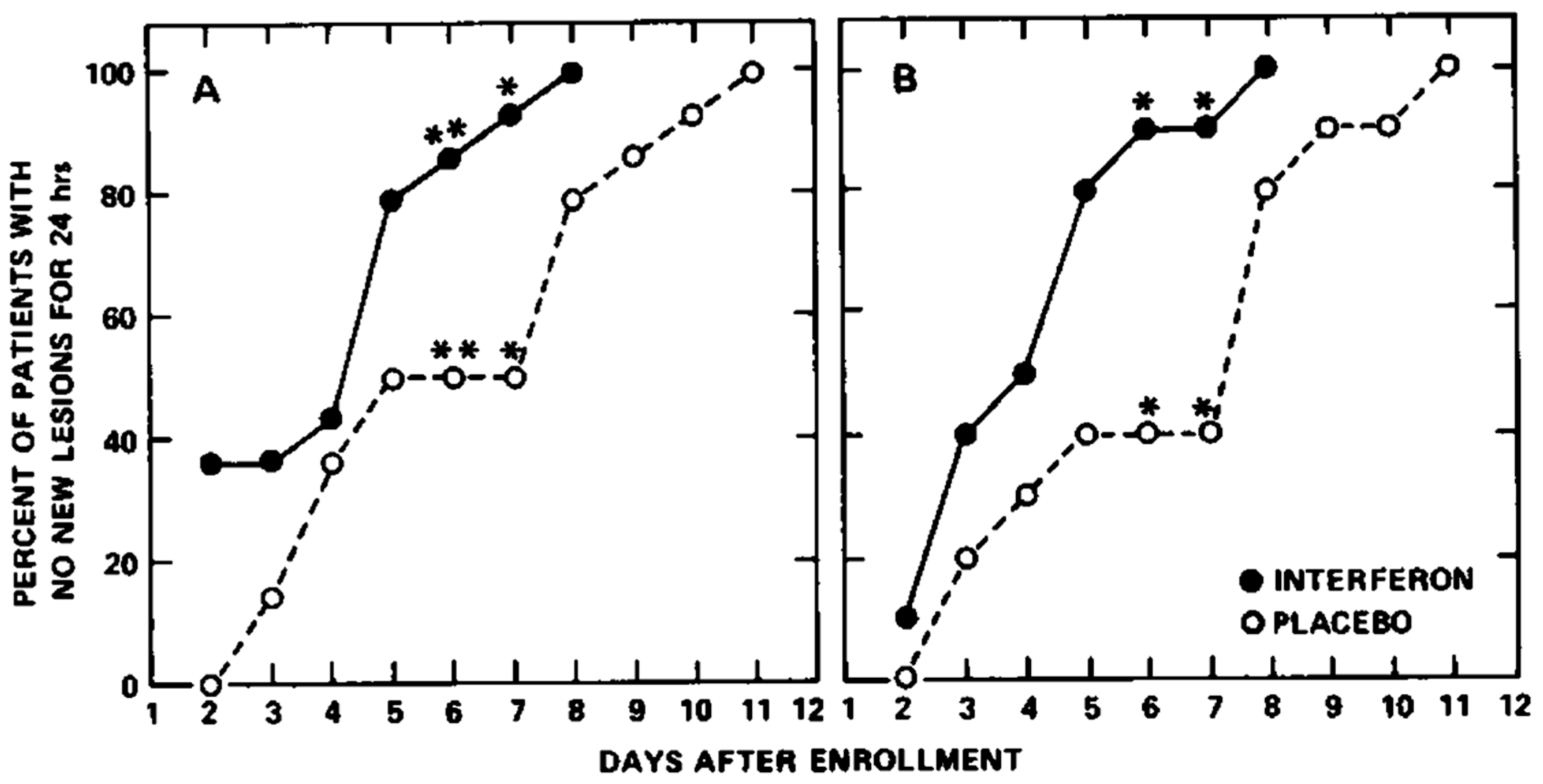

5. Human Leukocyte Interferon in the Treatment of VZV Infections

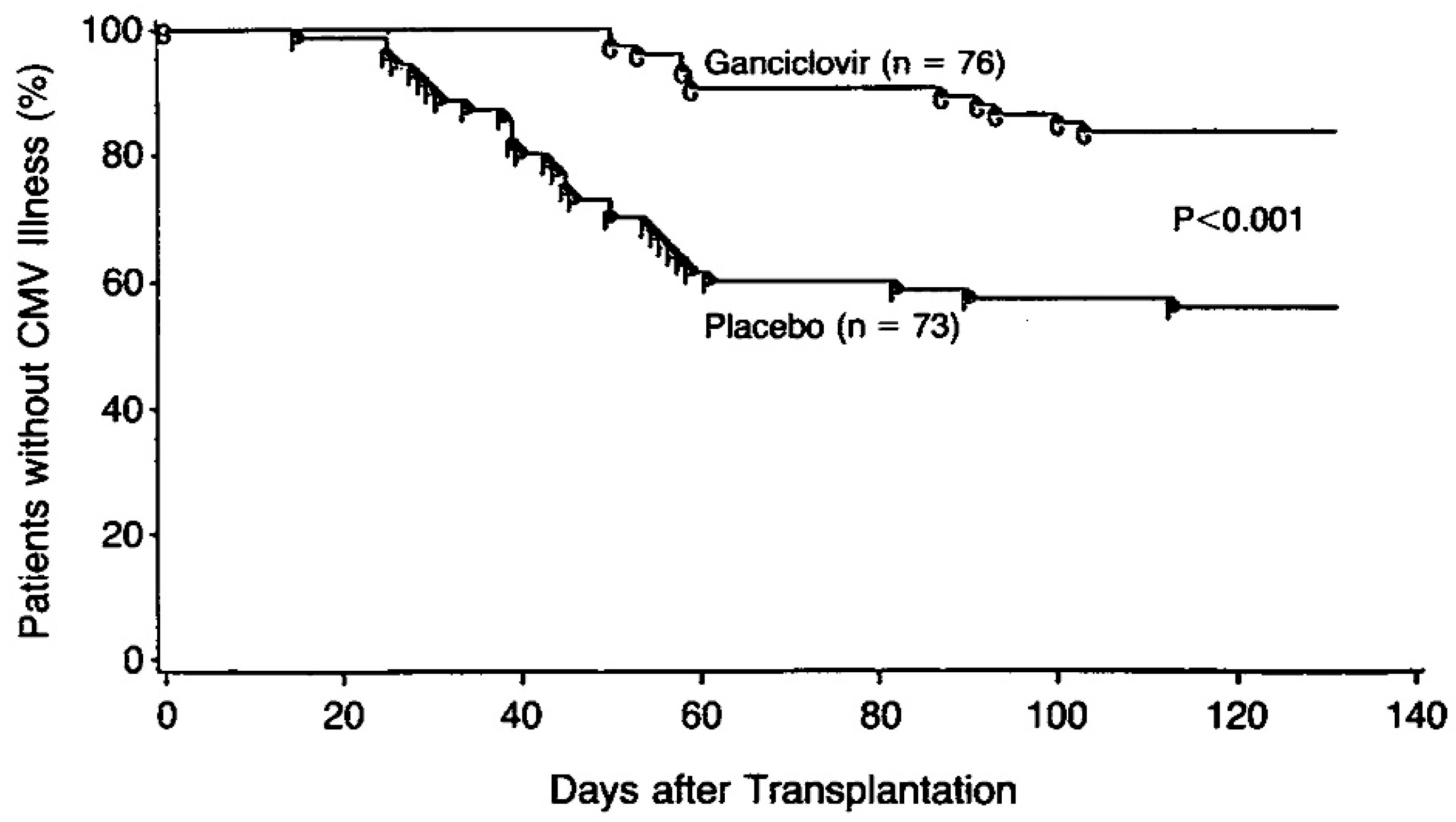

6. Interferon, ara-A, Acyclovir, and Ganciclovir in the Treatment of HSV and CMV Infections

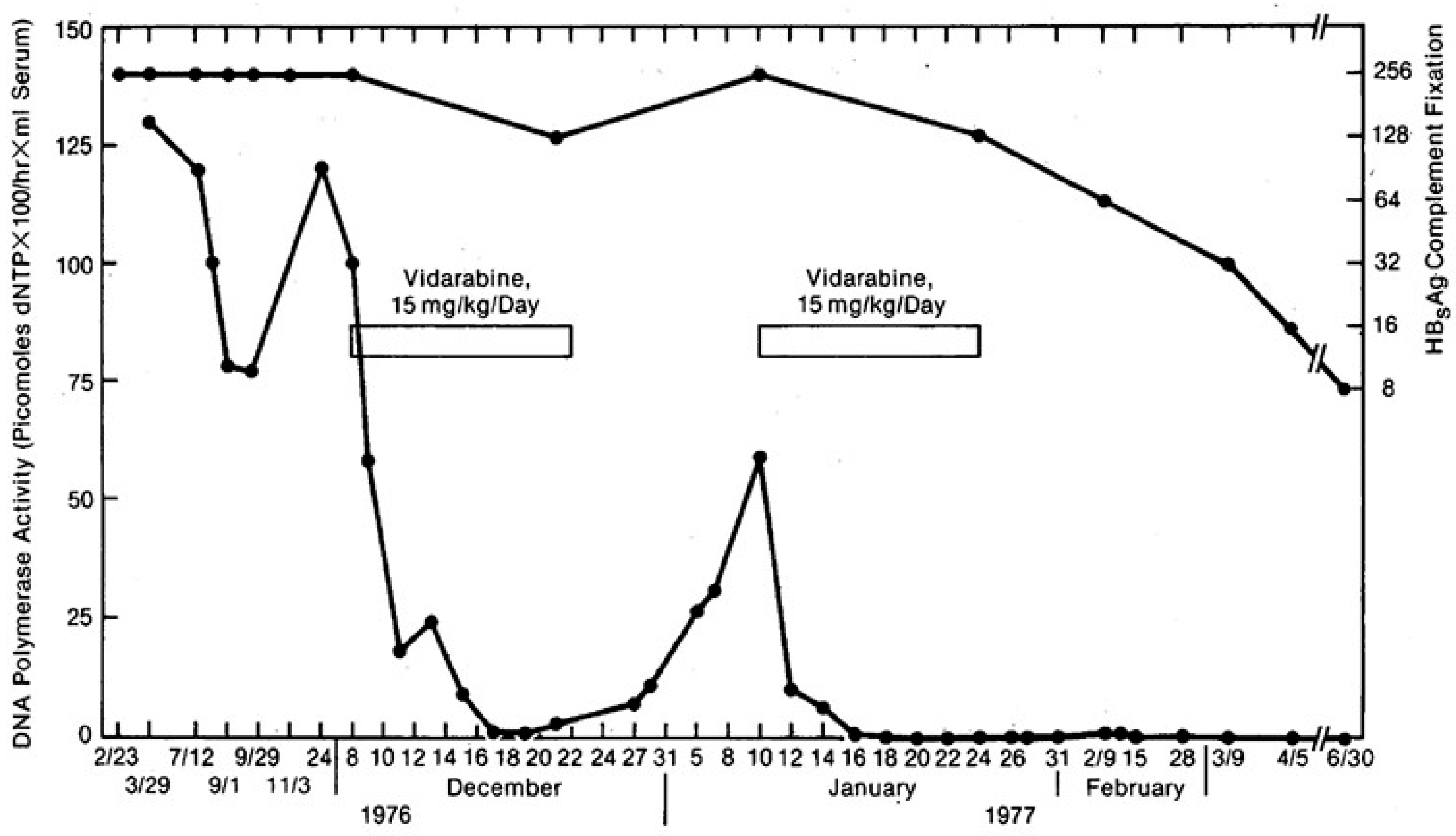

7. Interferon and ara-A in the Treatment of Chronic Hepatitis B Virus (HBV) Infection

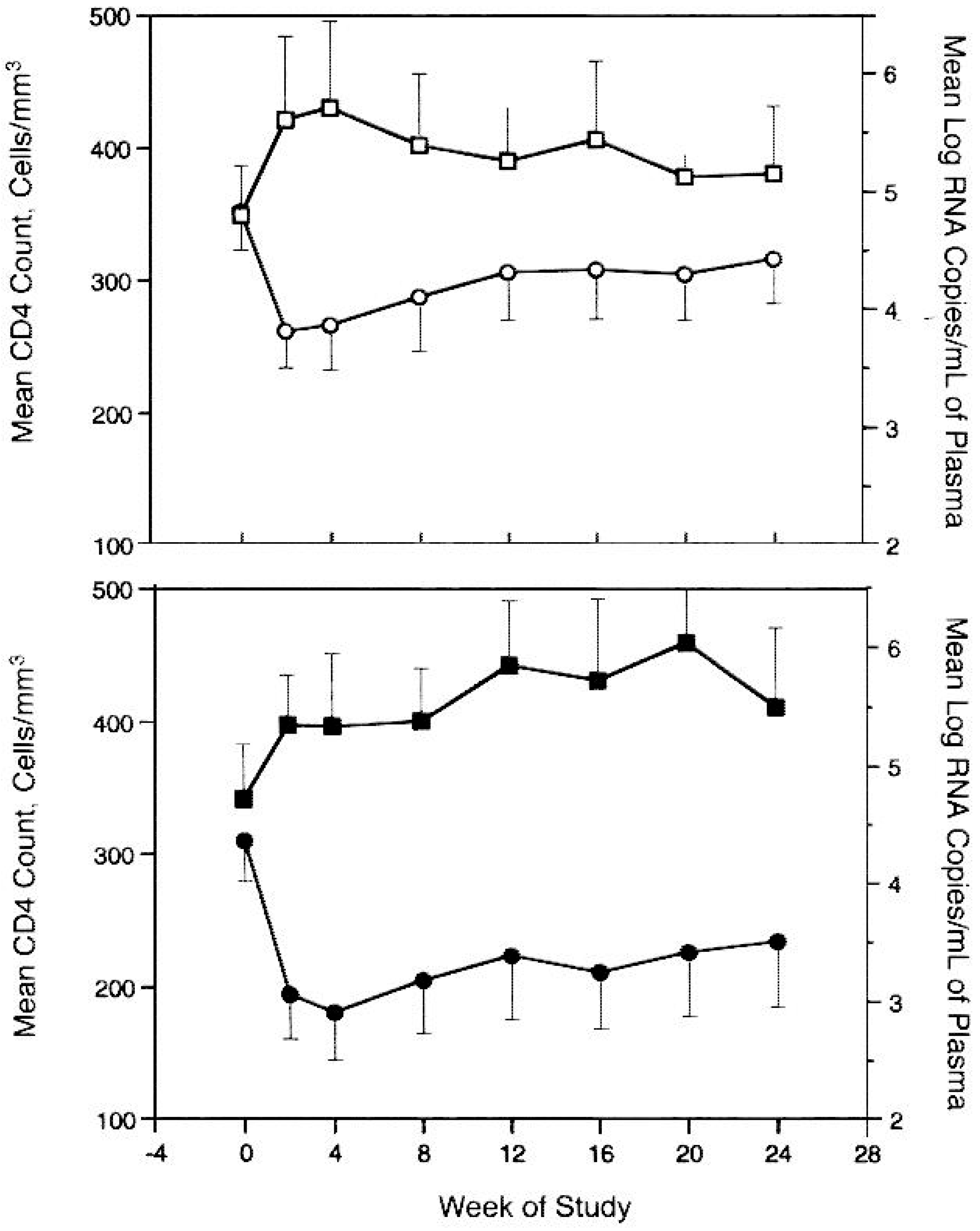

8. Treatment of HIV Infections

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Merigan, T.C. Purified interferons: Physical properties and species specificity. Science 1964, 145, 811–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petralli, J.K.; Merigan, T.C.; Wilbur, J.R. Circulating interferon after measles vaccination. N. Engl. J. Med. 1965, 273, 198–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petralli, J.K.; Merigan, T.C.; Wilbur, J.R. Action of endogenous interferon against vaccinia infection in children. Lancet 1965, 2, 401–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merigan, T.C. Interferons of mice and men. N. Engl. J. Med. 1967, 276, 913–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merigan, T.C. Induction of circulating interferon by synthetic anionic polymers of known composition. Nature 1967, 214, 416–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merigan, T.C.; Regelson, W. Interferon induction in man by a synthetic polyanion of defined composition. N. Engl. J. Med. 1967, 277, 1283–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Somer, P.; De Clercq, E.; Billiau, A.; Schonne, E.; Claesen, M. Antiviral activity of polyacrylic and polymethacrylic acids. I. Mode of action in vitro. J. Virol. 1968, 2, 878–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Somer, P.; De Clercq, E.; Billiau, A.; Schonne, E.; Claesen, M. Antiviral activity of polyacrylic and polymethacrylic acids. II. Mode of action in vivo. J. Virol. 1968, 2, 886–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merigan, T.C.; Finkelstein, M.S. Interferon-stimulating and in vivo antiviral effects of various synthetic anionic polymers. Virology 1968, 35, 363–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Clercq, E. Mechanism of the Antiviral Activity of Synthetic Polyanions. Ph.D. Thesis, KU Leuven, Leuven, Belgium, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- De Clercq, E.; Merigan, T.C. Requirement of a stable secondary structure for the antiviral activity of polynucleotides. Nature 1969, 222, 1148–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Clercq, E.; Eckstein, E.; Merigan, T.C. Interferon induction increased through chemical modification of a synthetic polyribonucleotide. Science 1969, 165, 1137–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Clercq, E.; Eckstein, F.; Sternbach, H.; Merigan, T.C. Interferon induction by and ribonuclease sensitivity of thiophosphate-substituted polyribonucleotides. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1969, 9, 187–191. [Google Scholar]

- De Clercq, E.; Merigan, T.C. An active interferon inducer obtained from Hemophilus influenzae type B. J. Immunol. 1969, 103, 899–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaacs, A.; Lindenmann, J. Virus interference. I. The interferon. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 1957, 147, 258–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Clercq, E.; Merigan, T.C. Current concepts of interferon and interferon induction. Annu. Rev. Med. 1970, 21, 17–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Clercq, E.; Wells, R.D.; Merigan, T.C. Increase in antiviral activity of polynucleotides by thermal activation. Nature 1970, 226, 364–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Clercq, E.; Merigan, T.C. Induction of interferon by nonviral agents. Arch. Intern. Med. 1970, 126, 94–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merigan, T.C.; De Clercq, E.; Bausek, G.H. Nonviral interferon inducers. J. Gen. Physiol. 1970, 56, 57–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Clercq, E.; Nuwer, M.R.; Merigan, T.C. The role of interferon in the protective effect of a synthetic double-stranded polyribonucleotide against intranasal vesicular stomatitis virus challenge in mice. J. Clin. Investig. 1970, 49, 1565–1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merigan, T.C. Interferon stimulated by double stranded RNA. Nature 1970, 228, 219–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Clercq, E.; Wells, R.D.; Grant, R.C.; Merigan, T.C. Thermal activation of the antiviral activity of synthetic double-stranded polyribonucleotides. J. Mol. Biol. 1971, 56, 83–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krueger, R.E.; Mayer, G.D. Tilorone hydrochloride: An orally active antiviral agent. Science 1970, 169, 1213–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, G.D.; Krueger, R.F. Tilorone hydrochloride: Mode of action. Science 1970, 169, 1214–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Clercq, E.; Merigan, T.C. Bis-DEAE-fluorenone: Mechanism of antiviral protection and stimulation of interferon production in the mouse. J. Infect. Dis. 1971, 123, 190–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Clercq, E.; Wells, R.D.; Merigan, T.C. Studies on the antiviral activity and cell interaction of synthetic double-stranded polyribo- and polydeoxyribonucleotides. Virology 1972, 47, 405–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, A.K.; Tytell, A.A.; Lampson, G.P.; Hilleman, M.R. Inducers of interferon and host resistance. II. Multistranded synthetic polynucleotide complexes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1967, 58, 1004–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Black, D.R.; Eckstein, F.; DeClercq, E.; Merigan, T.C. Studies on the toxicity and antiviral activity of various polynucleotides. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1973, 3, 198–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merigan, T.C.; Reed, S.E.; Hall, T.S.; Tyrrell, D.A. Inhibition of respiratory virus infection by locally applied interferon. Lancet 1973, 1, 563–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keay, S.; Teng, N.; Eisenberg, M.; Story, B.; Sellers, P.W.; Merigan, T.C. Topical interferon for treating condyloma acuminata in women. J. Infect. Dis. 1988, 158, 934–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merigan, T.C. Host defenses against viral disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 1974, 290, 323–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merigan, T.C. Human interferon as a therapeutic agent. N. Engl. J. Med. 1979, 300, 42–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merigan, T.C. Human interferon as a therapeutic agent—current status. N. Engl. J. Med. 1983, 308, 1530–1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirsch, M.S.; Schooley, R.T.; Cosimi, A.B.; Russell, P.S.; Delmonico, F.L.; Tolkoff-Rubin, N.E.; Herrin, J.T.; Cantell, K.; Farrell, M.L.; Rota, T.R.; et al. Effects of interferon-alpha on cytomegalovirus reactivation syndromes in renal-transplant recipients. N. Engl. J. Med. 1983, 308, 1489–1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, D.A.; Jordan, G.W.; Waddell, T.F.; Merigan, T.C. Adverse effect of cytosine arabinoside on disseminated zoster in a controlled trial. N. Engl. J. Med. 1973, 289, 873–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, G.W.; Fried, R.P.; Merigan, T.C. Administration of human leukocyte interferon in herpes zoster. I. Safety, circulating, antiviral activity, and host responses to infection. J. Infect. Dis. 1974, 130, 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merigan, T.C. Editorial: Efficacy of adenine arabinoside in herpes zoster. N. Engl. J. Med. 1976, 294, 1233–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whitley, R.J.; Ch’ien, L.T.; Dolin, R.; Galasso, G.J.; Alford, C.A., Jr. Adenine arabinoside therapy of herpes zoster in the immunosuppressed. NIAID collaborative antiviral study. N. Engl. J. Med. 1976, 294, 1193–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arvin, A.M.; Feldman, S.; Merigan, T.C. Human leukocyte interferon in the treatment of varicella in children with cancer: A preliminary controlled trial. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1978, 13, 605–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merigan, T.C.; Rand, K.H.; Pollard, R.B.; Abdallah, P.S.; Jordan, G.W.; Fried, R.P. Human leukocyte interferon for the treatment of herpes zoster in patients with cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 1978, 298, 981–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arvin, A.M.; Kushner, J.H.; Feldman, S.; Baehner, R.L.; Hammond, D.; Merigan, T.C. Human leukocyte interferon for the treatment of varicella in children with cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 1982, 306, 761–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, S.; Gallagher, J.G.; Merigan, T.C. Controlled clinical trial of intravenous acyclovir in heart-transplant patients with mucocutaneous herpes simplex infections. Lancet 1981, 1, 1392–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollard, R.B.; Egbert, P.R.; Gallagher, J.G.; Merigan, T.C. Cytomegalovirus retinitis in immunosuppressed hosts. I. Natural history and effects of treatment with adenine arabinoside. Ann. Intern. Med. 1980, 93, 655–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, S.W.; Dylewski, J.S.; Gaynon, M.W.; Egbert, P.R.; Merigan, T.C. Alpha-interferon administration in cytomegalovirus retinitis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1984, 25, 25–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keay, S.; Bissett, J.; Merigan, T.C. Ganciclovir treatment of cytomegalovirus infections in iatrogenically immunocompromised patients. J. Infect. Dis. 1987, 156, 1016–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keay, S.; Petersen, E.; Icenogle, T.; Zeluff, B.J.; Samo, T.; Busch, D.; Newman, C.L.; Buhles, W.C., Jr.; Merigan, T.C. Ganciclovir treatment of serious cytomegalovirus infection in heart and heart-lung transplant recipients. Rev. Infect. Dis. 1988, 10, S563–S572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merigan, T.C. Treatment of cytomegalovirus infection in the AIDS patient. Transplant. Proc. 1991, 23, 122–125. [Google Scholar]

- Merigan, T.C.; Renlund, D.G.; Keay, S.; Bristow, M.R.; Starnes, V.; O’Connell, J.B.; Resta, S.; Dunn, D.; Gamberg, P.; Ratkovec, R.M.; et al. A controlled trial of ganciclovir to prevent cytomegalovirus disease after heart transplantation. N. Engl. J. Med. 1992, 326, 1182–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenberg, H.B.; Pollard, R.B.; Lutwick, L.I.; Gregory, P.B.; Robinson, W.S.; Merigan, T.C. Effect of human leukocyte interferon on hepatitis B virus infection in patients with chronic active hepatitis. N. Engl. J. Med. 1976, 295, 517–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pollard, R.B.; Smith, J.L.; Neal, A.; Gregory, P.B.; Merigan, T.C.; Robinson, W.S. Effect of vidarabine on chronic hepatitis B virus infection. JAMA 1978, 239, 1648–1650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scullard, G.H.; Andres, L.L.; Greenberg, H.B.; Smith, J.L.; Sawhney, V.K.; Neal, E.A.; Mahal, A.S.; Popper, H.; Merigan, T.C.; Robinson, W.S.; et al. Antiviral treatment of chronic hepatitis B virus infection: Improvement in liver disease with interferon and adenine arabinoside. Hepatology 1981, 1, 228–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scullard, G.H.; Pollard, R.B.; Smith, J.L.; Sacks, S.L.; Gregory, P.B.; Robinson, W.S.; Merigan, T.C. Antiviral treatment of chronic hepatitis B virus infection. I. Changes in viral markers with interferon combined with adenine arabinoside. J. Infect. Dis. 1981, 143, 772–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scullard, G.H.; Greenberg, H.B.; Smith, J.L.; Gregory, P.B.; Merigan, T.C.; Robinson, W.S. Antiviral treatment of chronic hepatitis B virus infection: Infectious virus cannot be detected in patient serum after permanent responses to treatment. Hepatology 1982, 2, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacks, S.L.; Scullard, G.H.; Pollard, R.B.; Gregory, P.B.; Robinson, W.S.; Merigan, T.C. Antiviral treatment of chronic hepatitis B virus infection: Pharmacokinetics and side effects of interferon and adenine arabinoside alone and in combination. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1982, 21, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, C.I.; Merigan, T.C. Therapeutic approaches to chronic hepatitis B. Prog. Liver Dis. 1982, 7, 481–494. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, C.I.; Kitchen, L.W.; Scullard, G.H.; Robinson, W.S.; Gregory, P.B.; Merigan, T.C. Vidarabine monophosphate and human leukocyte interferon in chronic hepatitis B infection. JAMA 1982, 247, 2261–2265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberg, M.; Rosno, S.; Garcia, G.; Konrad, M.W.; Gregory, P.B.; Robinson, W.S.; Merigan, T.C. Preliminary trial of recombinant fibroblast interferon in chronic hepatitis B virus infection. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1986, 29, 122–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bissett, J.; Eisenberg, M.; Gregory, P.; Robinson, W.S.; Merigan, T.C. Recombinant fibroblast interferon and immune interferon for treating chronic hepatitis B virus infection: Patients’ tolerance and the effect on viral markers. J. Infect. Dis. 1988, 157, 1076–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merigan, T.C. What are we going to do about AIDS and HTLV-III/LAV infection? N. Engl. J. Med. 1984, 311, 1311–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merigan, T.C. A personal view of efforts in treatment of human immunodeficiency virus infection in 1988. J. Infect. Dis. 1989, 159, 390–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schooley, R.T.; Merigan, T.C.; Gaut, P.; Hirsch, M.S.; Holodniy, M.; Flynn, T.; Liu, S.; Byington, R.E.; Henochowicz, S.; Gubish, E.; et al. Recombinant soluble CD4 therapy in patients with the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) and AIDS-related complex. A phase I-II escalating dosage trial. Ann. Intern. Med. 1990, 112, 247–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merigan, T.C.; Skowron, G. Safety and tolerance of dideoxycytidine as a single agent. Results of early-phase studies in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) or advanced AIDS-related complex. Study Group of the AIDS Clinical Trials Group of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. Am. J. Med. 1990, 88, 11s–15s. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skowron, G.; Merigan, T.C. Alternating and intermittent regimens of zidovudine (3′-azido-3′-deoxythymidine) and dideoxycytidine (2′,3′-dideoxycytidine) in the treatment of patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) and AIDS-related complex. Am. J. Med. 1990, 88, 20s–23s. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merigan, T.C. Treatment of AIDS with combinations of antiretroviral agents. Am. J. Med. 1991, 90, 8s–17s. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skowron, G.; Bozzette, S.A.; Lim, L.; Pettinelli, C.B.; Schaumburg, H.H.; Arezzo, J.; Fischl, M.A.; Powderly, W.G.; Gocke, D.J.; Richman, D.D.; et al. Alternating and intermittent regimens of zidovudine and dideoxycytidine in patients with AIDS or AIDS-related complex. Ann. Intern. Med. 1993, 118, 321–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozal, M.J.; Kroodsma, K.; Winters, M.A.; Shafer, R.W.; Efron, B.; Katzenstein, D.A.; Merigan, T.C. Didanosine resistance in HIV-infected patients switched from zidovudine to didanosine monotherapy. Ann. Intern. Med. 1994, 121, 263–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafer, R.W.; Iversen, A.K.; Winters, M.A.; Aguiniga, E.; Katzenstein, D.A.; Merigan, T.C.; The AIDS Clinical Trials Group 143 Virology Team. Drug resistance and heterogeneous long-term virologic responses of human immunodeficiency virus type 1-infected subjects to zidovudine and didanosine combination therapy. J. Infect. Dis. 1995, 172, 70–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collier, A.C.; Coombs, R.W.; Schoenfeld, D.A.; Bassett, R.L.; Timpone, J.; Baruch, A.; Jones, M.; Facey, K.; Whitacre, C.; McAuliffe, V.J.; et al. Treatment of human immunodeficiency virus infection with saquinavir, zidovudine, and zalcitabine. N. Engl. J. Med. 1996, 334, 1011–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

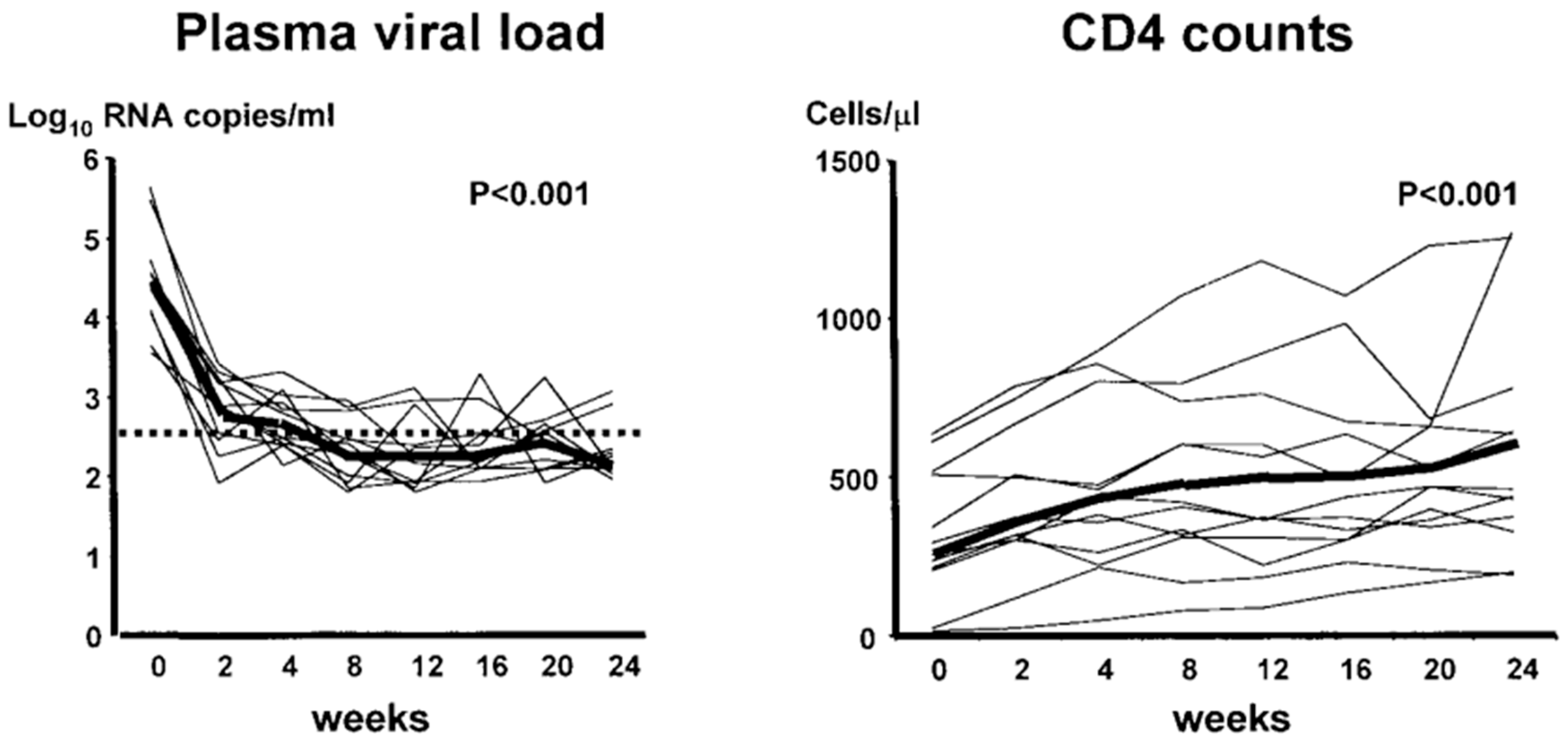

- Schapiro, J.M.; Winters, M.A.; Stewart, F.; Efron, B.; Norris, J.; Kozal, M.J.; Merigan, T.C. The effect of high-dose saquinavir on viral load and CD4+ T-cell counts in HIV-infected patients. Ann. Intern. Med. 1996, 124, 1039–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hammer, S.M.; Katzenstein, D.A.; Hughes, M.D.; Gundacker, H.; Schooley, R.T.; Haubrich, R.H.; Henry, W.K.; Lederman, M.M.; Phair, J.P.; Niu, M.; et al. A trial comparing nucleoside monotherapy with combination therapy in HIV-infected adults with CD4 cell counts from 200 to 500 per cubic millimeter. AIDS Clinical Trials Group Study 175 Study Team. N. Engl. J. Med. 1996, 335, 1081–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafer, R.W.; Winters, M.A.; Palmer, S.; Merigan, T.C. Multiple concurrent reverse transcriptase and protease mutations and multidrug resistance of HIV-1 isolates from heavily treated patients. Ann. Intern. Med. 1998, 128, 906–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schapiro, J.M.; Lawrence, J.; Speck, R.; Winters, M.A.; Efron, B.; Coombs, R.W.; Collier, A.C.; Merigan, T.C. Resistance mutations to zidovudine and saquinavir in patients receiving zidovudine plus saquinavir or zidovudine and zalcitabine plus saquinavir in AIDS clinical trials group 229. J. Infect. Dis. 1999, 179, 249–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winters, M.A.; Coolley, K.L.; Girard, Y.A.; Levee, D.J.; Hamdan, H.; Shafer, R.W.; Katzenstein, D.A.; Merigan, T.C. A 6-basepair insert in the reverse transcriptase gene of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 confers resistance to multiple nucleoside inhibitors. J. Clin. Investig. 1998, 102, 1769–1775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, J.; Schapiro, J.; Winters, M.; Montoya, J.; Zolopa, A.; Pesano, R.; Efron, B.; Winslow, D.; Merigan, T.C. Clinical resistance patterns and responses to two sequential protease inhibitor regimens in saquinavir and reverse transcriptase inhibitor-experienced persons. J. Infect. Dis. 1999, 179, 1356–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winters, M.A.; Merigan, T.C. Variants other than aspartic acid at codon 69 of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 reverse transcriptase gene affect susceptibility to nuleoside analogs. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2001, 45, 2276–2279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winters, M.A.; Baxter, J.D.; Mayers, D.L.; Wentworth, D.N.; Hoover, M.L.; Neaton, J.D.; Merigan, T.C. Frequency of antiretroviral drug resistance mutations in HIV-1 strains from patients failing triple drug regimens. The Terry Beirn Community Programs for Clinical Research on AIDS. Antivir. Ther. 2000, 5, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, C.M.; Lawrence, J.; Ranheim, E.A.; Vierra, M.; Zupancic, M.; Winters, M.; Altman, J.; Montoya, J.; Zolopa, A.; Schapiro, J.; et al. Highly active antiretroviral therapy results in HIV type 1 suppression in lymph nodes, increased pools of naive T cells, decreased pools of activated T cells, and diminished frequencies of peripheral activated HIV type 1-specific CD8+ T cells. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses 2000, 16, 1357–1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robbins, G.K.; De Gruttola, V.; Shafer, R.W.; Smeaton, L.M.; Snyder, S.W.; Pettinelli, C.; Dubé, M.P.; Fischl, M.A.; Pollard, R.B.; Delapenha, R.; et al. Comparison of sequential three-drug regimens as initial therapy for HIV-1 infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003, 349, 2293–2303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shafer, R.W.; Smeaton, L.M.; Robbins, G.K.; De Gruttola, V.; Snyder, S.W.; D’Aquila, R.T.; Johnson, V.A.; Morse, G.D.; Nokta, M.A.; Martinez, A.I.; et al. Comparison of four-drug regimens and pairs of sequential three-drug regimens as initial therapy for HIV-1 infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003, 349, 2304–2315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haas, D.W.; Smeaton, L.M.; Shafer, R.W.; Robbins, G.K.; Morse, G.D.; Labbe, L.; Wilkinson, G.R.; Clifford, D.B.; D’Aquila, R.T.; De Gruttola, V.; et al. Pharmacogenetics of long-term responses to antiretroviral regimens containing Efavirenz and/or Nelfinavir: An Adult Aids Clinical Trials Group Study. J. Infect. Dis. 2005, 192, 1931–1942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

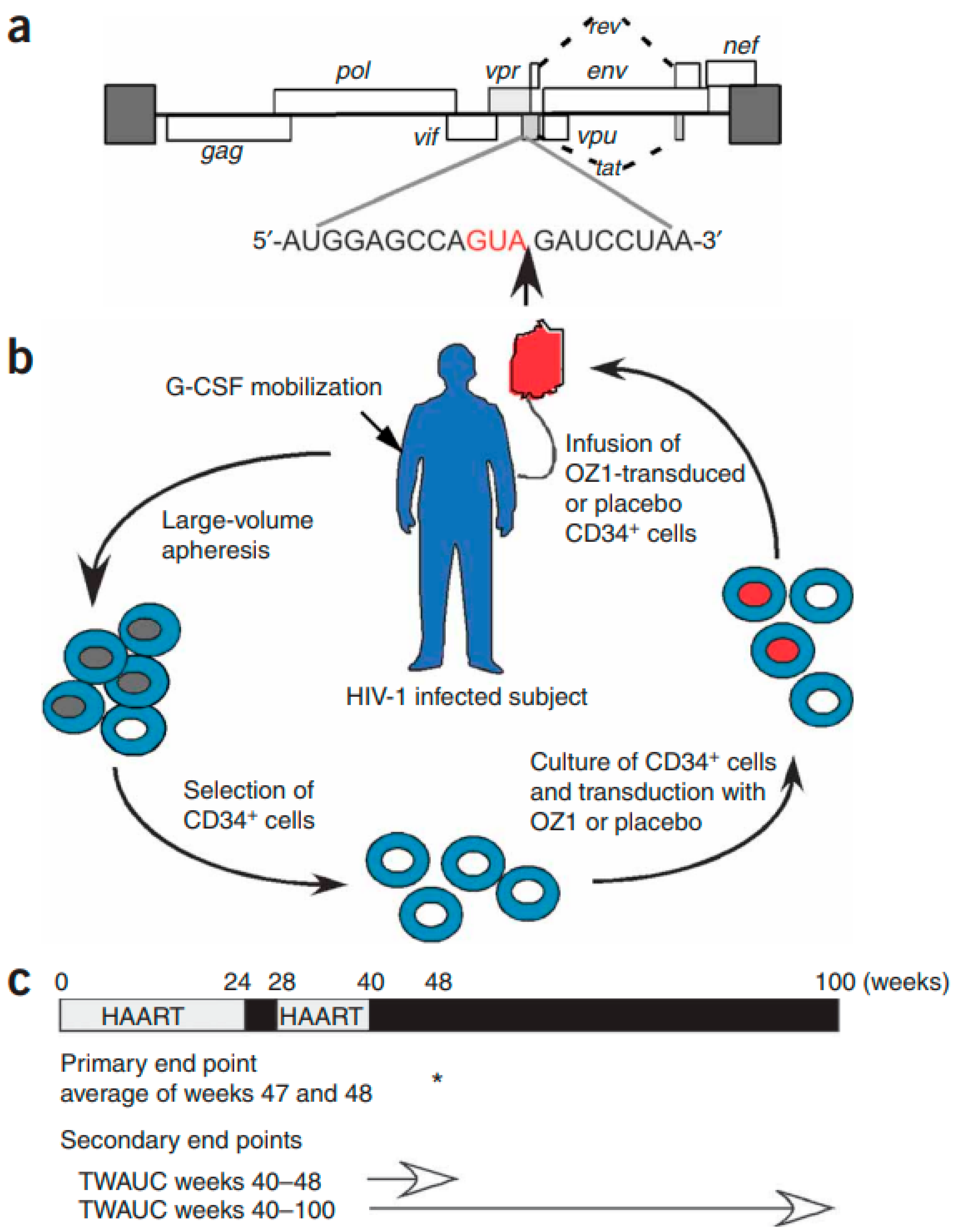

- Mitsuyasu, R.T.; Merigan, T.C.; Carr, A.; Zack, J.A.; Winters, M.A.; Workman, C.; Bloch, M.; Lalezari, J.; Becker, S.; Thornton, L.; et al. Phase 2 gene therapy trial of an anti-HIV ribozyme in autologous CD34+ cells. Nat. Med. 2009, 15, 285–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

De Clercq, E. Pioneering Role of T.C. Merigan in the Treatment of Various Virus Infections. Molecules 2026, 31, 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010025

De Clercq E. Pioneering Role of T.C. Merigan in the Treatment of Various Virus Infections. Molecules. 2026; 31(1):25. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010025

Chicago/Turabian StyleDe Clercq, Erik. 2026. "Pioneering Role of T.C. Merigan in the Treatment of Various Virus Infections" Molecules 31, no. 1: 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010025

APA StyleDe Clercq, E. (2026). Pioneering Role of T.C. Merigan in the Treatment of Various Virus Infections. Molecules, 31(1), 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010025