Plant Alkaloids as Promising Anticancer Compounds with Blood–Brain Barrier Penetration in the Treatment of Glioblastoma: In Vitro and In Vivo Models

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Description of Glioblastoma

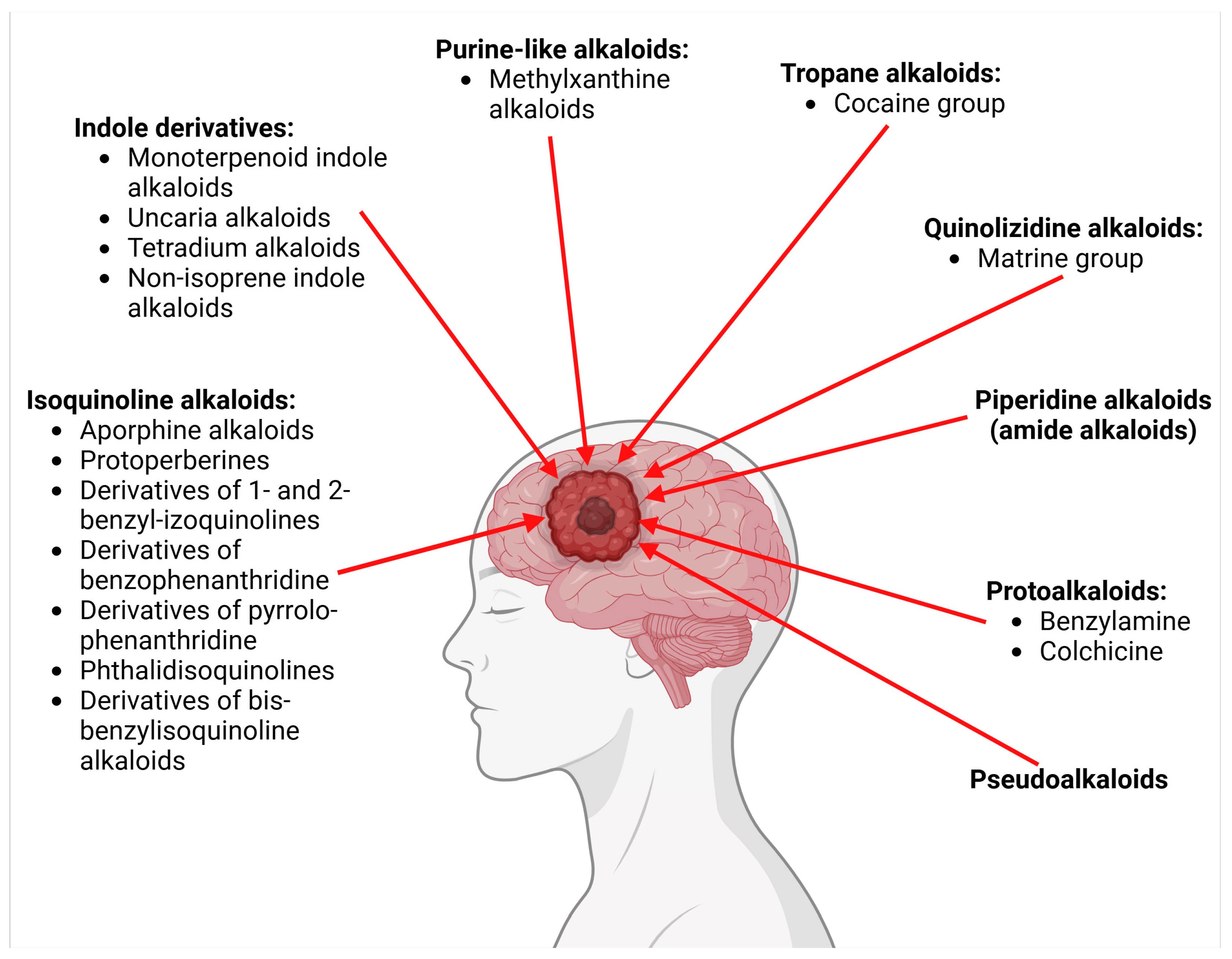

1.2. Review of Alkaloids (Group of Plant Metabolites and Group of Chemical Compounds Classified According to Chemical Structure)

- I.

- Alkaloids with nitrogen heterocycles (true alkaloids)—six classes.

- II.

- Protoalkaloids (alkaloids with nitrogen in the side chain)—two classes.

- III.

- Pseudoalkaloids—one class of chemical compounds.

- IV.

- Polyamines alkaloids.

- Apocynaceae (Catharanthus roseus);

- Aquifoliaceae (Ilex paraguariensis—yerba mate);

- Amaryllidaceae (Clivia miniata, Lycoris radiata, Crinum americanum);

- Berberidaceae (Berberis aquifolium, B. vulgaris, B. aristata);

- Buxaceae (Buxus sinica);

- Colchicaceae (Colchicum autumnale);

- Erythroxylaceae (Erythroxylum coca);

- Fabaceae (Sophora flavescens);

- Lauraceae (Litsea glutinosa, Neolitsea konishii);

- Loganiaceae (Strychnos nux-vomica);

- Malvaceae (Theobroma cacao);

- Melanthiaceae (Veratrum californicum);

- Monimiaceae (Peumus boldus);

- Nitrariaceae (Peganum harmala);

- Papaveraceae (Chelidonium majus, Papaver somniferum);

- Piperaceae (Piper nigrum, P. longum, P. sarmentosum);

- Ranunculaceae (Coptis chinensis, Hydrastis canadensis);

- Rubiaceae (Coffea arabica—Arabica coffee, Uncaria tomentosa);

- Rutaceae (Evodia rutaecarpa, Zanthoxylum simulans, Z. ailanthoides, Z. stelligerum, Z. nitidum);

- Sapindaceae (Paullinia cupana—guarana);

- Solanaceae (Capsicum annuum, Lycium chinense, Solanum lycocarpum, S. nigrum);

- Menispermaceae (Stephania tetrandra).

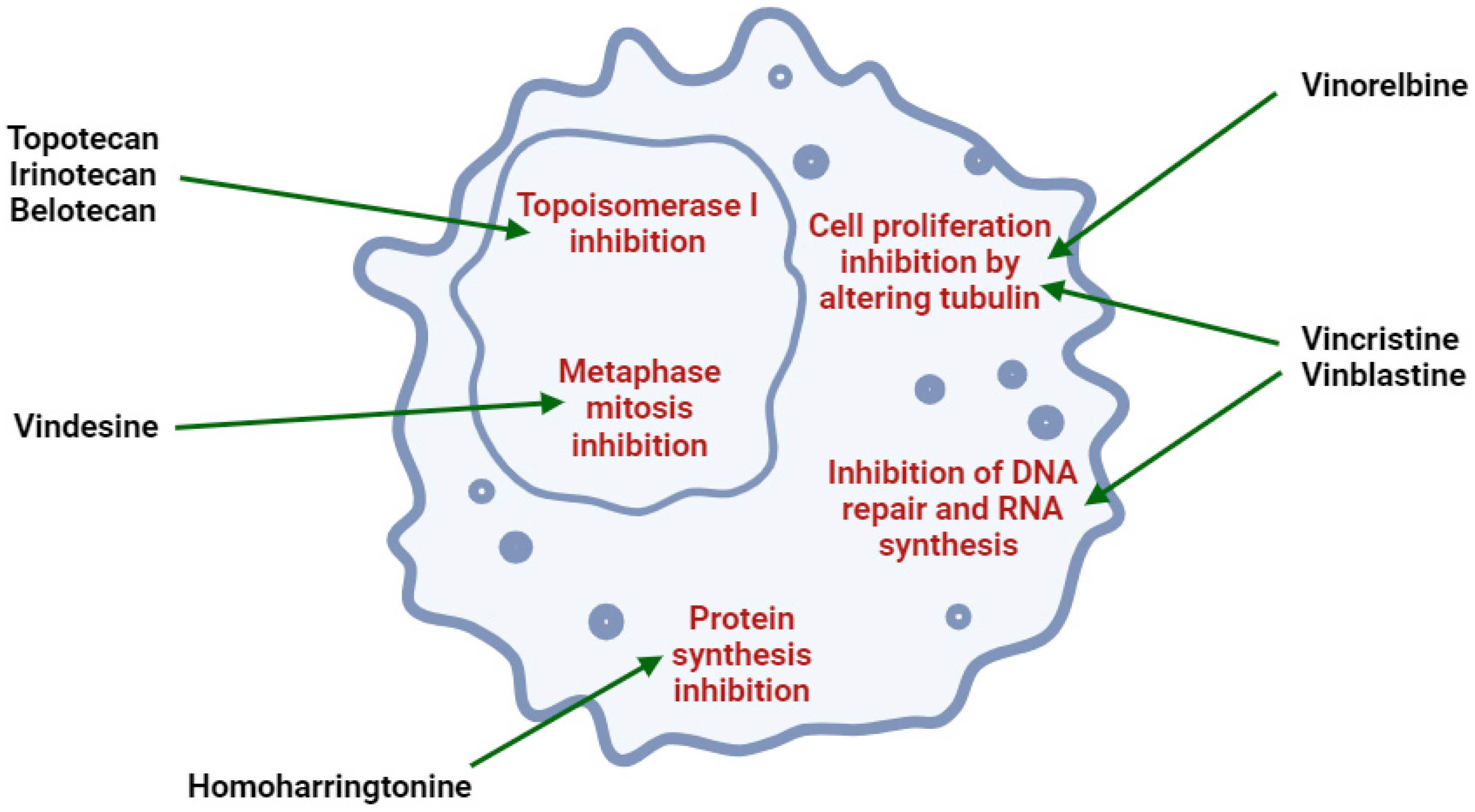

1.3. The Use of Alkaloids in Potential Anticancer Therapies and Prognoses for Improving the Effectiveness of These Therapies

2. Current Status in Medicinal Products Based on Plant Alkaloids as Anticancer Drugs in Various Groups of Cancers

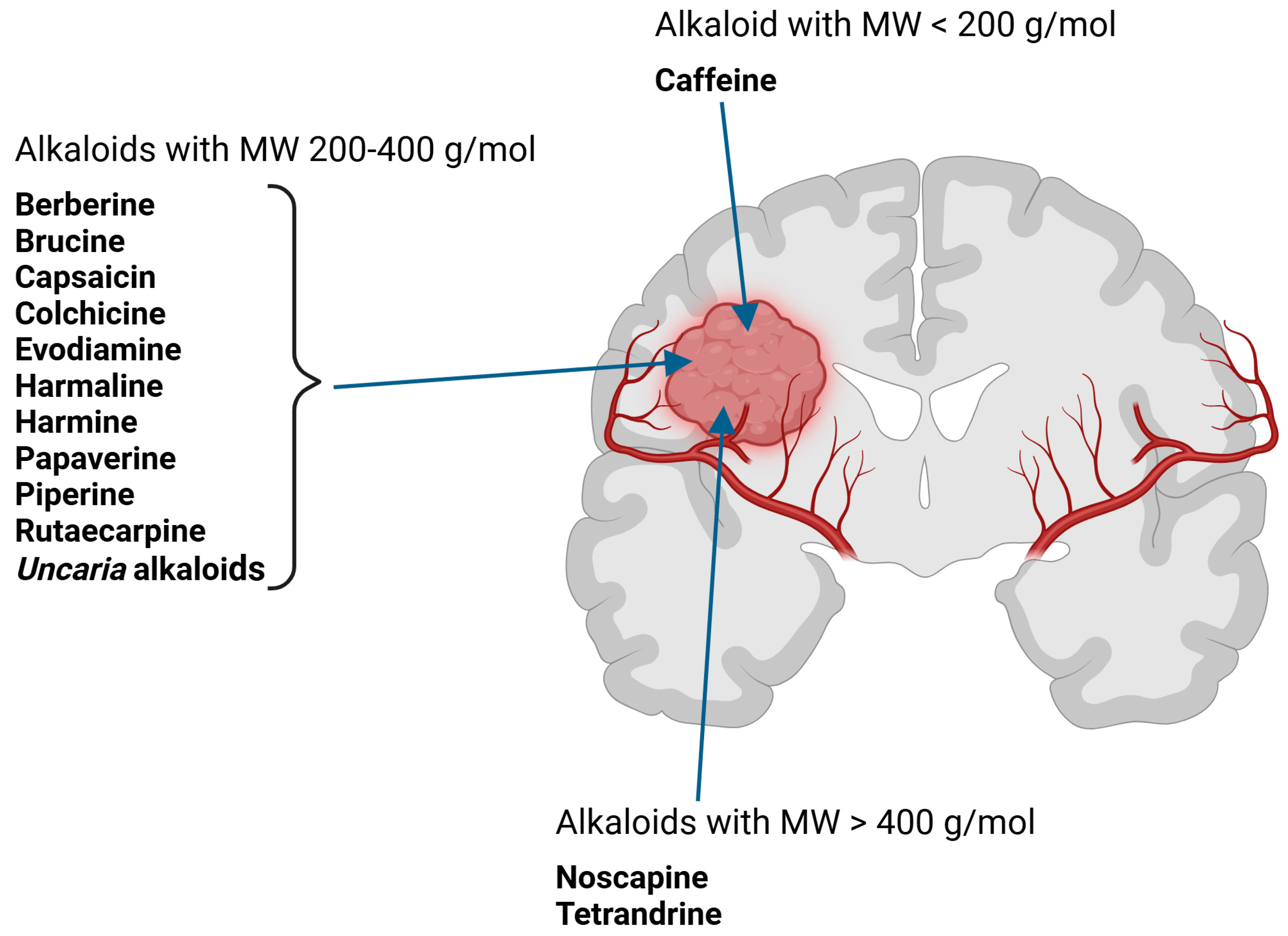

3. Penetration/Transport of Selected Alkaloids Across the Blood–Brain Barrier—In Vitro and In Vivo Studies (Progress in Basic Research)

3.1. Caffeine

3.2. Harmine and Harmaline

3.3. Piperine

3.4. Evodiamine and Rutaecarpine

3.5. Capsaicin

3.6. Berberine and Derivatives

3.7. Papaverine

3.8. Brucine and Strychnine

3.9. Uncaria Alkaloids

3.10. Colchicine

3.11. Noscapine

3.12. Tertrandrine (with Borneol, Vinorelbine, Vincristine)

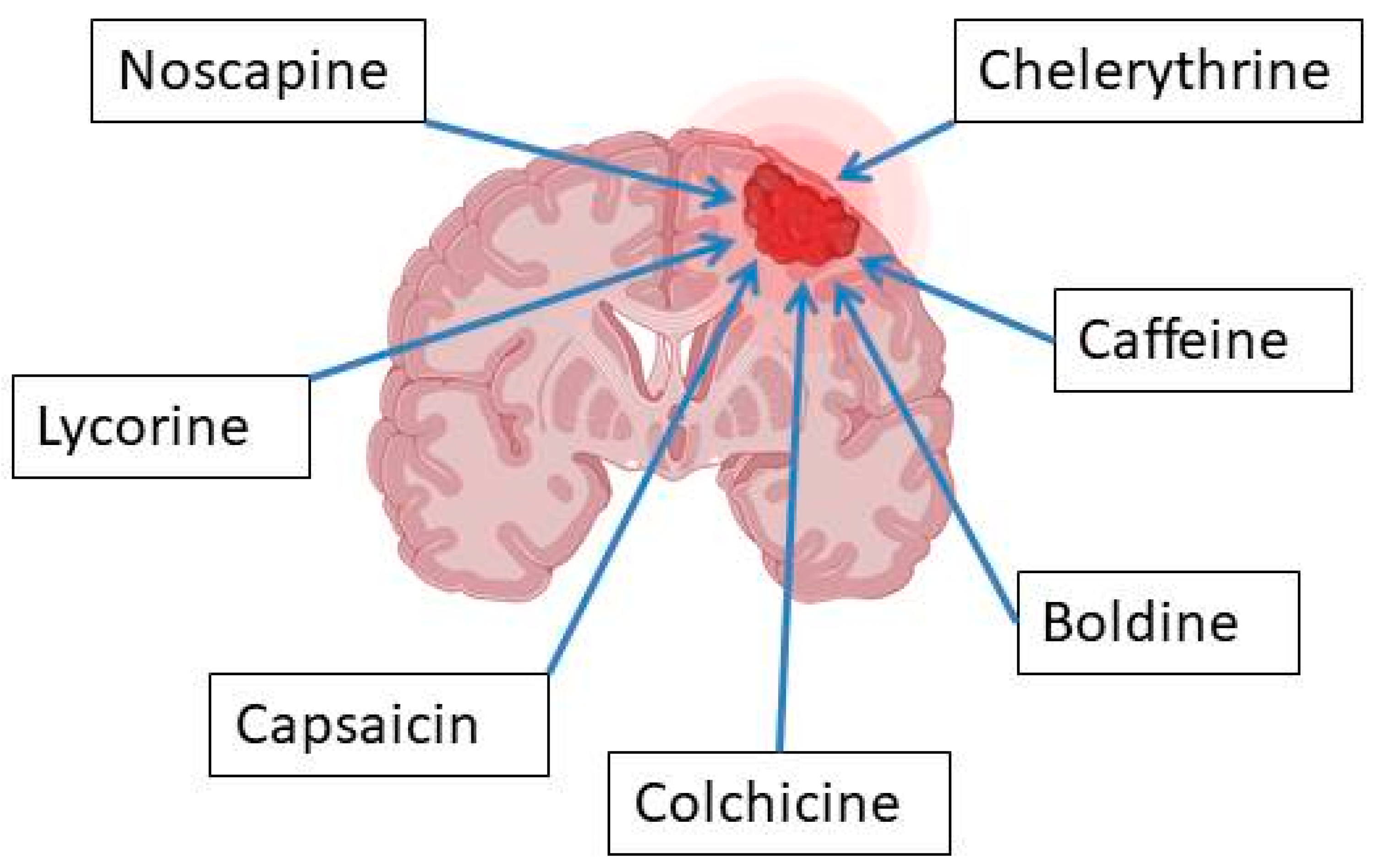

4. Progress in Studies of Plant Alkaloids in Glioblastoma Models with Indication of Mechanism of Actions

- (1)

- Decreasing the viability of glioma cells;

- (2)

- Suppressing cell proliferation;

- (3)

- Inhibiting migration and invasion of glioma cells;

- (4)

- Inducing apoptosis (increasing the percentage of apoptotic glioma cells);

- (5)

- Decreasing the expression of Bcl-2 (an antiapoptotic marker) and other genes, as well as key signaling pathways.

- (1)

- Antiangiogenic effects;

- (2)

- Decreasing tumor weight;

- (3)

- Improving the survival rate of animals (Table 2).

4.1. Boldine, Berberine and Papaverine

4.2. Chelerythrine, Dihydrochelerythrine and Nitidine

4.3. Lycorine

4.4. Noscapine

4.5. Tetrandrine

4.6. Brucine, Uncaria Alkaloids, Tetradium Alkaloids, Rutaecarpine, Derivatives of β-Carboline

4.7. Piperine

4.8. Colchicine

| I. Alkaloids with nitrogen heterocycles (true alkaloids) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Class: Isoquinoline alkaloids 1.1. Major group: Aporphine alkaloids | |||||

| Family name: Lauraceae, Monimiaceae | |||||

| No | Name of alkaloid | Natural source/derivative | Pharmacological model | Effect/IC50 | Ref |

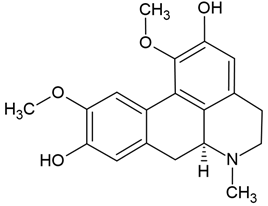

| 1 | Boldine | Peumus boldus (Monimiaceae), Litsea glutinosa (Lauraceae), Neolitsea konishii (Lauraceae) | glioma cell lines (GBM59, GBM96, U87-MG) |

| [28] |

Chemical structure: | C19H21NO4 MW = 327.4 g/mol IUPAC Name: (6aS)-1,10-dimethoxy-6-methyl-5,6,6a,7-tetrahydro-4H-dibenzo[de,g]quinoline-2,9-diol | ||||

| 1.2. Major group: Protoperberines | |||||

| Family name: Berberidaceae, Ranunculaceae | |||||

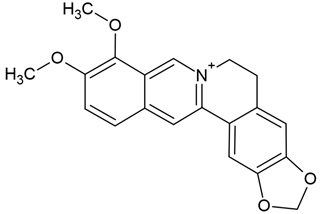

| 2 | Berberine - isoquinoline alkaloid | Hydrastis canadensis (Ranunculaceae), Coptis chinensis (Ranunculaceae), Berberis aquifolium, Berberis vulgaris, Berberis aristata (Berberidaceae) | glioma cell lines (U-87 and LN229) |

| [43] |

| Berberine | glioma cell lines (U87MG) |

| [20] | ||

| Berberine | ectopic and orthotopic xenograft models in BALB/c nude mice |

| [44] | ||

| Berberine | (1) glioblastoma cell lines (U87 and U251) (2) the ectopic tumor xenograft mouse model | In vitro

| [44] | ||

| Berberine | glioma cell lines (U87 and U251) | In vitro

| [46] | ||

| Berberine | glioma cell line (U343) |

| |||

| Berberine | glioma cell lines (U87 and U251) |

| [46] | ||

| Berberine | Berberine chloride | (1) glioma cell lines (U-87 MG, U251 MG, U-118 MG, and SHG-44) (2) U87 cells inoculated into the right striatum of mouse brains - berberine (50 and 100 mg/kg body weight) daily for 5 weeks. | In vitro:

| [47] | |

Chemical structure: | C20H18NO4+ MW = 336.4 g/mol IUPAC Name: 16,17-dimethoxy-5,7-dioxa-13-azoniapentacyclo[11.8.0.02,10.04,8.015,20]henicosa-1(13),2,4(8),9,14,16,18,20-octaene | ||||

| 1.3. Major group: Derivatives of 1- and 2-benzyl-izoquinolines | |||||

| Family name: Papaveraceae | |||||

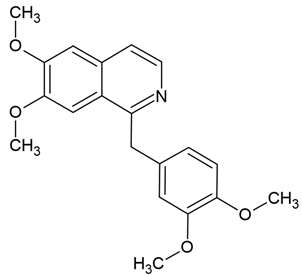

| 3 | Papaverine (non-narcotic opium alkaloid) | Papaver somniferum | (1) human GBM U87MG, T98G cells (2) U87MG xenograft mouse model |

EC50 = 40 μM (T98G cells) Suppressing the tumor cell growth in a U87MG xenograft mouse model and reducing the tumor volume by 63% with papaverine treatment in comparison with the vehicle control (on day 47) | [59] |

Chemical structure: | C20H21NO4 MW = 339.4 g/mol IUPAC Name: 1-[(3,4-dimethoxyphenyl)methyl]-6,7-dimethoxyisoquinoline | ||||

| 1.4. Major group: Derivatives of benzophenanthridine | |||||

| Family name: Papaveraceae | |||||

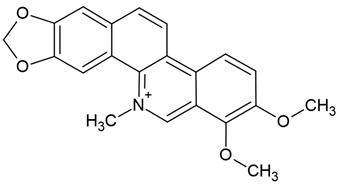

| 4 | Chelerythrine | Chelidonium maius | glioblastoma cell lines (U251 and T98G); BALB/c nude mice |

| [29] |

| Chelerythrine | (1) glioma cell lines (rat C6 and human U87), (2) U87 xenograft animal model |

| [32] | ||

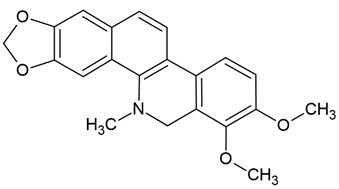

Chemical structure: | C21H18NO4+ MW = 348.4 g/mol IUPAC Name: 1,2-dimethoxy-12-methyl-[1,3]benzodioxolo[5,6-c]phenanthridin-12-ium | ||||

| Family name: Rutaceae | |||||

| 5 | Dihydrochelerythrine (DHC) | Zanthoxylum simulans, Z. ailanthoides, Z. stelligerum | human glioblastoma cells (U251, GL-15), murine glioblastoma cells (C6) |

| [30] |

Chemical structure: | C21H19NO4 MW = 349.4 g/mol IUPAC Name: 1,2-dimethoxy-12-methyl-13H-[1,3]benzodioxolo[5,6-c]phenanthridine | ||||

| 6 | Nitidine chloride | Zanthoxylum nitidum (root) | human glioblastoma cell lines U87 and LN18 |

| [31] |

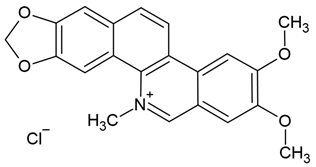

Chemical structure: | C21H18NO4+ MW = 348.4 g/mol IUPAC Name: 2,3-dimethoxy-12-methyl-[1,3]benzodioxolo[5,6-c]phenanthridin-12-ium;chloride | ||||

| 1.5. Major group: Derivatives of pyrrolo-phenanthridine (Amarylis alkaloids) | |||||

| Family name: Amaryllidaceae | |||||

| 7 | Lycorine (narcissine) | Clivia miniata, Lycoris radiata, Crinum americanum | (1) glioblastoma cell line (U-87); (2) the protein–protein interaction (PPI) network (the STRING online database) | In vitro:

| [66,88] |

| Lycorine (narcissine) | (1) molecular docking modeling assay (2) 10 cell lines (i.e., U87, LN229, U251, A172, Gli36vIII, GBM6) (3) In vitro EGFR kinase assay (4) xenograft models |

| [65] | ||

| Lycorine hydrochloride | (1) human GBM cells (temozolomide-resistant LN229 and U251 cells = 251R, 229R cells) (2) 229R xenograft mouse model |

| [64] | ||

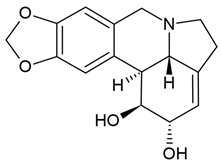

Chemical structure: | C16H17NO4 MW = 287.3 g/mol IUPAC Name: (1S,17S,18S,19S)-5,7-dioxa-12-azapentacyclo[10.6.1.02,10.04,8.015,19]nonadeca-2,4(8),9,15-tetraene-17,18-diol | ||||

| 1.6. Major group: Phthalidisoquinolines | |||||

| Family name: Papaveraceae | |||||

| 8 | Noscapine | Papaver somniferum | various glioblastoma cell lines |

| [83] |

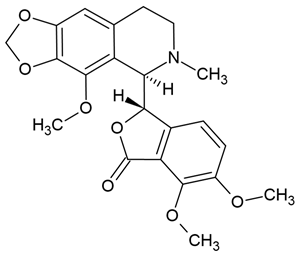

Chemical structure: | C22H23NO7 MW = 413.4 g/mol IUPAC Name: (3S)-6,7-dimethoxy-3-[(5R)-4-methoxy-6-methyl-7,8-dihydro-5H-[1,3]dioxolo[4,5-g]isoquinolin-5-yl]-3H-2-benzofuran-1-one | ||||

| 1.7. Major group: Derivatives of bis-benzylisoquinoline alkaloids | |||||

| Family name: Menispermaceae | |||||

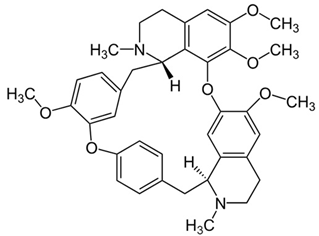

| 9 | Tetrandrine | Stephania tetrandra (root) | (1) GBM 8401/luc2 human glioblastoma cells (2) xenografted nude mice | In vitro:

| [36] |

| Tetrandrine | GBM 8401 cells |

| [37,44] | ||

| Tetrandrine | glioma stem-like cells (GSLCs) from the human glioblastoma cell lines U87 and U251 |

| [38] | ||

Chemical structure: | C38H42N2O6 MW = 622.7 g/mol IUPAC Name: (1S,14S)-9,20,21,25-tetramethoxy-15,30-dimethyl-7,23-dioxa-15,30-diazaheptacyclo[22.6.2.23,6.18,12.114,18.027,31.022,33]hexatriaconta-3(36),4,6(35),8,10,12(34),18,20,22(33),24,26,31-dodecaene | ||||

| 2. Class: Indole derivatives | |||||

| 2.1. Group: Monoterpenoid indole alkaloids | |||||

| Family name: Loganiaceae | |||||

| No | Name of alkaloid | Natural source/derivative | Pharmacological model | Effect/IC50 | Ref. |

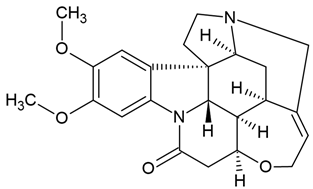

| 1 | Brucine | glioblastoma lines (U118, U87, U251, and A172) |

| [42] | |

Chemical structure: | C23H26N2O4 MW = 394.5 g/mol IUPAC Name: (4aR,5aS,8aR,13aS,15aS,15bR)-10,11-dimethoxy-4a,5,5a,7,8,13a,15,15a,15b,16-decahydro-2H-4,6-methanoindolo[3,2,1-ij]oxepino[2,3,4-de]pyrrolo[2,3-h]quinolin-14-one | ||||

| 2.2. Group: Uncaria alkaloids | |||||

| Family name: Rubiaceae | |||||

| 2 | Oxindole alkaloids-pentacyclic alkaloids | Uncaria tomentosa (stem bark and leaves) | human glioblastoma cell line-U-251-MG |

SI = 0.10–0.19 for chemotype I SI = 0.21–0.57 for chemotype III Hirsuteine (MW = 366.5 g/mol), hirsutine (MW = 368.5 g/mol), isocorynoxeine (MW = 382.5 g/mol), corynoxeine (MW = 382.5 g/mol), and isorhynchophylline (MW = 384.5 g/mol) | [60] |

| 2.3. Group: Tetradium alkaloids | |||||

| Family name: Rutaceae | |||||

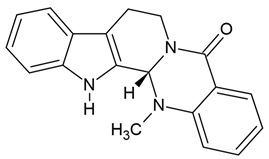

| 3 | Evodiamine (quinazolinocar-boline alkaloid) | Evodia rutaecarpa = Tetradium ruticarpum | human GBM cell lines U251 and LN229 |

| [67] |

Chemical structure: | C19H17N3O MW = 303.4 g/mol IUPAC Name: (1S)-21-methyl-3,13,21-triazapentacyclo[11.8.0.02,10.04,9.015,20]henicosa-2(10),4,6,8,15,17,19-heptaen-14-one | ||||

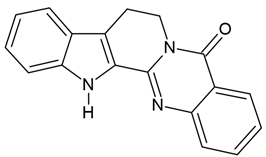

| 4 | Rutaecarpine (indolopyridoquinazoline alkaloids) (in comparison with other main alkaloids: evodiamine, dehydroarutaecar-pine) | Evodia rutaecarpa | U87 human glioblastoma cells |

| [41] |

Chemical structure: | C18H13N3O MW = 287.3 g/mol IUPAC Name: 3,13,21-triazapentacyclo[11.8.0.02,10.04,9.015,20]henicosa-1(21),2(10),4,6,8,15,17,19-octaen-14-one | ||||

| 2.4. Group: Non-isoprene indole alkaloids—Derivatives of β-carboline | |||||

| Family name: Nitrariaceae | |||||

| 5 | Harmine | Peganum harmala (the seeds) | glioblastoma (GBM) cell lines (U251-MG and U373-MG cells) |

| [33,34] |

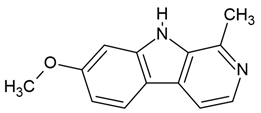

Chemical structure: | C13H12N2O MW = 212.3 g/mol IUPAC Name: 7-methoxy-1-methyl-9H-pyrido[3,4-b]indole | ||||

| 6 | Harmaline | Peganum harmala (the seeds) | human malignant glioblastoma cell line (U-87) |

| [35] |

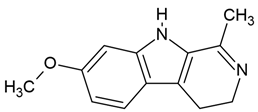

Chemical structure: | C13H14N2O MW = 214.3 g/mol IUPAC Name: 7-methoxy-1-methyl-4,9-dihydro-3H-pyrido[3,4-b]indole | ||||

| 3. Class: Purine-like alkaloids | |||||

| 3.1. Group: Methylxanthine alkaloids | |||||

| Family name: Aquifoliaceae, Malvaceae, Rubiaceae, Sapindaceae | |||||

| No | Name of alkaloid | Natural source/derivative | Pharmacological model | Effect/IC50 | Ref. |

| 1 | Caffeine (1,3,7-trimethylxanthine) | Coffea arabica (Rubiaceae), Paulinia cumana (Sapindaceae), Ilex paraguariensis (Aquifoliaceae), Theobroma cacao (Malvaceae) | glioblastoma line: U87-MG (with or without temozolomid (500 μM TMZ) |

| [51] |

| Caffeine | glioblastoma cell lines (U-87MG and LN229) |

| [52] | ||

| Caffeine | glioblastoma lines (C6 and U87MG) |

| [53] | ||

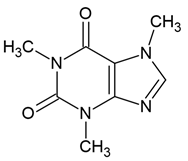

Chemical structure: | C8H10N4O2 MW = 194.2 g/mol IUPAC Name: 1,3,7-trimethylpurine-2,6-dione | ||||

| 4. Class: Tropane alkaloid | |||||

| 4.1. Group:Cocaine group | |||||

| Family name: Erythroxylaceae | |||||

| No | Name of alkaloid/class of alkaloids | Natural source/derivative | Pharmacological model | Effect/IC50 | Ref. |

| 1 | Cocaine | Erythroxylum coca | C6 glioblastoma cells |

| [79] |

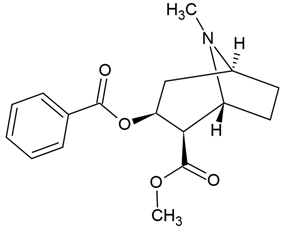

Chemical structure: | C17H21NO4 MW = 303.4 g/mol IUPAC Name: methyl (1R,2R,3S,5S)-3-benzoyloxy-8-methyl-8-azabicyclo[3.2.1]octane-2-carboxylate | ||||

| 5. Class: Quinolizidine alkaloids | |||||

| 5.1. Group: Matrine group | |||||

| Family name: Fabaceae | |||||

| No | Name of alkaloid/class of alkaloids | Natural source/derivative | Pharmacological model | Effect/IC50 | Ref. |

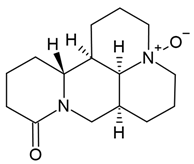

| 1 | Oxymatrine | Sophora flavescens | U251MG human malignant glioma cells |

| [70] |

Chemical structure: | C15H24N2O2 MW = 264.4 g/mol IUPAC Name: (1R,2R,9S,17S)-13-oxido-7-aza-13-azoniatetracyclo[7.7.1.02,7.013,17]heptadecan-6-one | ||||

| 6. Class: Piperidine alkaloids (amide alkaloids) | |||||

| Family name: Piperaceae | |||||

| No | Name of alkaloid/class of alkaloids | Natural source/derivative | Pharmacological model | Effect/IC50 | Ref. |

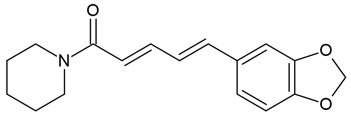

| 1 | Piperine (bioperine; 1-piperoylpiperidine) | Piper nigrum, P. longum (fruits), P. sarmentosum (roots) | human cells T98G |

| [90] |

| Piperine (bioperine; 1-piperoylpiperidine) | (1) human GBM U87 cells; (2) GBM cancer stem cells (GSCs); (3) in silico; the cancer genome atlas (TCGA) database |

| [89] | ||

Chemical structure: | C17H19NO3 MW = 285.3 g/mol IUPAC Name: (2E,4E)-5-(1,3-benzodioxol-5-yl)-1-piperidin-1-ylpenta-2,4-dien-1-one | ||||

| II. Protoalkaloids–alkaloids with nitrogen in the side chain | |||||

| 1. Class: Benzylamine | |||||

| Family name: Solanaceae | |||||

| No | Name of alkaloid/class of alkaloids | Natural source/derivative | Pharmacological model | Effect/IC50 | Ref. |

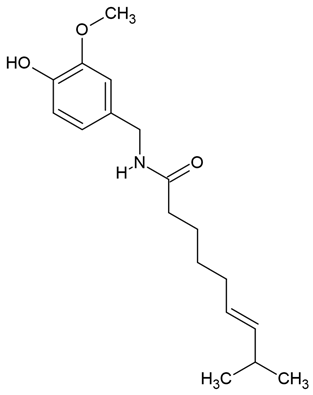

| 1 | Capsaicin (N-vanillyl-8-methyl-alpha-nonenamide) -a lipophilic protoalkaloid | Capsicum genus i.e., Capsicum annuum | glioblastoma cell line (LN-18) |

| [61] |

| Capsaicin | glioblastoma cell lines (U87-MG and U251) |

| [62] | ||

| Capsaicin and methoxy polyethylene glycol-poly(caprolactone) (mPEG-PCL) in nanoparticles | human glioblastoma cells (U251) |

| [175] | ||

Chemical structure: | C18H27NO3 MW = 305.4 g/mol IUPAC Name: (E)-N-[(4-hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl)methyl]-8-methylnon-6-enamide | ||||

| 2. Class: Colchicine | |||||

| Family name: Colchicaceae | |||||

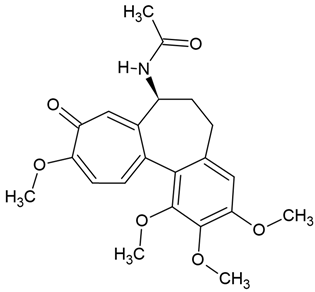

| 2 | Colchicine derivative (tricyclic alkaloid) | Colchicum autumnale | (1) glioblkastoma cell lines (U87MG and U373MG) (2) rat glioma animal model |

| [75] |

Chemical structure: | C22H25NO6 MW = 399.4 g/mol IUPAC Name: N-[(7S)-1,2,3,10-tetramethoxy-9-oxo-6,7-dihydro-5H-benzo[a]heptalen-7-yl]acetamide | ||||

| III. Pseudoalkaloids | |||||

| 1. Class: steroidal alkaloids | |||||

| Family name: Solanaceae | |||||

| No | Name of alkaloid/class of alkaloids | Natural source/derivative | Pharmacological model | Effect/IC50 | Ref. |

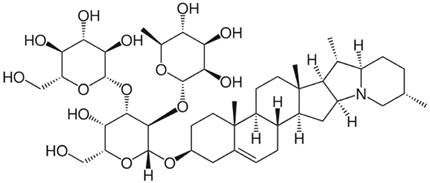

| 1 | α-Solanine (glycoalkaloid) | Solanum nigrum and Solanum tuberosum, and Solanum aculeastrum | (1) glioma cells (2) Traditional Chinese Medicine Systems Pharmacology Database (3) GeneCards, networks (STRING online database) |

| [39] |

Chemical structure: | C45H73NO16 MW = 868.1 g/mol IUPAC Name: 2-[5-hydroxy-6-(hydroxymethyl)-2-[(10,14,16,20-tetramethyl-22-azahexacyclo[12.10.0.02,11.05,10.015,23.017,22]tetracos-4-en-7-yl)oxy]-4-[3,4,5-trihydroxy-6-(hydroxymethyl)oxan-2-yl]oxyoxan-3-yl]oxy-6-methyloxane-3,4,5-triol | ||||

| Family name: Melanthiaceae | |||||

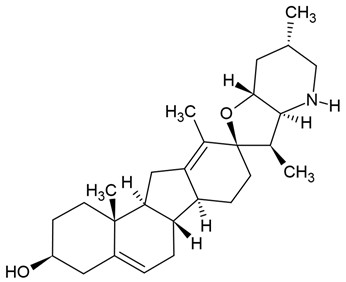

| 1 | Cyclopamine (steroidal alkaloid), cyclopamine glucuronide prodrug | in vitro, ex vivo, and in vivo: - glioma stem cells (GSCs) - C6 rat GBM cells |

| [73] | |

Chemical structure: | C27H41NO2 MW = 411.6 g/mol IUPAC Name: (3S,3′R,3′aS,6′S,6aS,6bS,7′aR,9R,11aS,11bR)-3′,6′,10,11b-tetramethylspiro[2,3,4,6,6a,6b,7,8,11,11a-decahydro-1H-benzo[a]fluorene-9,2′-3a,4,5,6,7,7a-hexahydro-3H-furo[3,2-b]pyridine]-3-ol | ||||

| Family name: Buxaceae | |||||

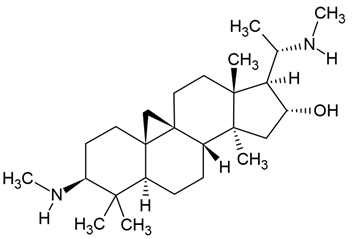

| 5 | Cyclovirobuxine D (CVBD) | Buxus sinica (Buxaceae) | glioblastoma (GBM) cell lines (T98G, U251) |

| [73] |

Chemical structure: | C26H46N2O MW = 402.7 g/mol IUPAC Name: (1S,3R,6S,8R,11S,12S,14R,15S,16R)-7,7,12,16-tetramethyl-6-(methylamino)-15-[(1S)-1-(methylamino)ethyl]pentacyclo[9.7.0.01,3.03,8.012,16]octadecan-14-ol | ||||

| IV. Polyamines alkaloids | |||||

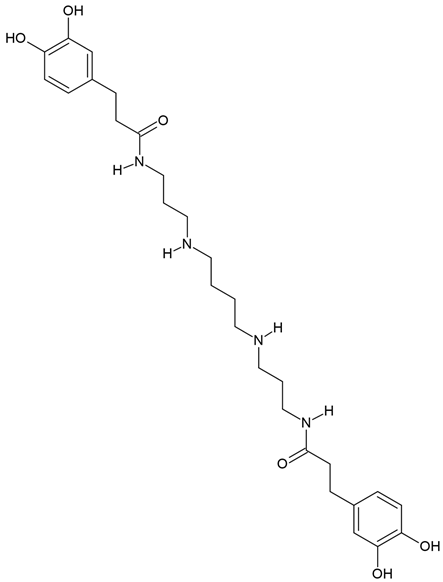

| Kukoamine A | Lycium chinense, potatoes, and tomatoes | human GBM cells (U251and WJ1) |

| [72] | |

Chemical structure: | C28H42N4O6 MW = 530.7 g/mol IUPAC Name: 3-(3,4-dihydroxyphenyl)-N-[3-[4-[3-[3-(3,4-dihydroxyphenyl)propanoylamino]propylamino]butylamino]propyl]propanamide | ||||

5. Comparison of Cytotoxicity and Safety Profile of Selected Alkaloids

- High-toxicity alkaloids (where risks outweigh benefits);

- Limited-toxicity alkaloids (where benefits exceed risks);

- Alkaloids under investigation in liposomal and nanoformulations (to mitigate toxicity concerns).

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ostrom, Q.T.; Bauchet, L.; Davis, F.G.; Deltour, I.; Fisher, J.L.; Langer, C.E.; Pekmezci, M.; Schwartzbaum, J.A.; Turner, M.C.; Walsh, K.M.; et al. The Epidemiology of Glioma in Adults: A “State of the Science” Review. Neuro Oncol. 2014, 16, 896–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, A.P.; Fisher, J.L.; Nichols, E.; Abd-Allah, F.; Abdela, J.; Abdelalim, A.; Abraha, H.N.; Agius, D.; Alahdab, F.; Alam, T.; et al. Global, Regional, and National Burden of Brain and Other CNS Cancer, 1990–2016: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Neurol. 2019, 18, 376–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grech, N.; Dalli, T.; Mizzi, S.; Meilak, L.; Calleja, N.; Zrinzo, A. Rising Incidence of Glioblastoma Multiforme in a Well-Defined Population. Cureus 2020, 12, e8195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kubelt, C.; Hattermann, K.; Sebens, S.; Mehdorn, H.M.; Held-Feindt, J. Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition in Paired Human Primary and Recurrent Glioblastomas. Int. J. Oncol. 2015, 46, 2515–2525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rong, L.; Li, N.; Zhang, Z. Emerging Therapies for Glioblastoma: Current State and Future Directions. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2022, 41, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanderi, T.; Munakomi, S.; Gupta, V. Glioblastoma Multiforme. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Deo, S.V.S.; Sharma, J.; Kumar, S. GLOBOCAN 2020 Report on Global Cancer Burden: Challenges and Opportunities for Surgical Oncologists. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2022, 29, 6497–6500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA A Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, Z.; Li, X.; Zhang, X. Glioblastoma: An Update in Pathology, Molecular Mechanisms and Biomarkers. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 3040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Gekas, C.; Verduzco, D.; Petiwala, S.; Jeffries, C.; Lu, C.; Murphy, E.; Anton, T.; Vo, A.H.; Xiao, Z.; et al. Building a Translational Cancer Dependency Map for The Cancer Genome Atlas. Nat. Cancer 2024, 5, 1176–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- General Principles of Cancer Chemotherapy. Available online: https://accesspharmacy.mhmedical.com/content.aspx?bookid=1810§ionid=124496835 (accessed on 28 December 2024).

- Bousbaa, H. Novel Anticancer Strategies. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuura, H.N.; Fett-Neto, A.G. Plant Alkaloids: Main Features, Toxicity, and Mechanisms of Action. In Plant Toxins; Gopalakrishnakone, P., Carlini, C.R., Ligabue-Braun, R., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2015; pp. 1–15. ISBN 978-94-007-6728-7. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, A.H.; Abdelrahman, M.; El-Sayed, M.A. Alkaloid Role in Plant Defense Response to Growth and Stress. In Bioactive Molecules in Plant Defense; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 145–158. ISBN 978-3-030-27165-7. [Google Scholar]

- Olofinsan, K.; Abrahamse, H.; George, B.P. Therapeutic Role of Alkaloids and Alkaloid Derivatives in Cancer Management. Molecules 2023, 28, 5578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Q.; Zhang, C.; Fang, H.; Yi, L.; Li, M. Indispensable Biomolecules for Plant Defense against Pathogens: NBS-LRR and “Nitrogen Pool” Alkaloids. Plant Sci. 2023, 334, 111752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adamski, Z.; Blythe, L.L.; Milella, L.; Bufo, S.A. Biological Activities of Alkaloids: From Toxicology to Pharmacology. Toxins 2020, 12, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karpiński, T.M.; Ożarowski, M.; Seremak-Mrozikiewicz, A.; Wolski, H.; Adamczak, A. Plant Preparations and Compounds with Activities against Biofilms Formed by Candida Spp. J. Fungi 2021, 7, 360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, A.G.; Cassani, L.; Garcia-Oliveira, P.; Otero, P.; Mansoor, S.; Echave, J.; Xiao, J.; Simal-Gándara, J.; Prieto, M.A. Plant Alkaloids: Production, Extraction, and Potential Therapeutic Properties. In Natural Secondary Metabolites: From Nature, Through Science, to Industry; Carocho, M., Heleno, S.A., Barros, L., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 157–200. ISBN 978-3-031-18587-8. [Google Scholar]

- Palma, T.V.; Lenz, L.S.; Bottari, N.B.; Pereira, A.; Schetinger, M.R.C.; Morsch, V.M.; Ulrich, H.; Pillat, M.M.; de Andrade, C.M. Berberine Induces Apoptosis in Glioblastoma Multiforme U87MG Cells via Oxidative Stress and Independent of AMPK Activity. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2020, 47, 4393–4400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajput, A.; Sharma, R.; Bharti, R. Pharmacological Activities and Toxicities of Alkaloids on Human Health. Mater. Today Proc. 2022, 48, 1407–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aalinezhad, S.; Dabaghian, F.; Namdari, A.; Akaberi, M.; Emami, S.A. Phytochemistry and Pharmacology of Alkaloids from Papaver Spp.: A Structure–Activity Based Study. Phytochem. Rev. 2024, 24, 585–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, L.Y.; Battulga, A.; Han, E.; Chung, H.; Li, J.H. New psychoactive substances of natural origin: A brief review. J. Food Drug Anal. 2017, 25, 461–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benowitz, N.L. Pharmacology of nicotine: Addiction, smoking-induced disease, and therapeutics. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2009, 49, 57–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinrich, M.; Mah, J.; Amirkia, V. Alkaloids Used as Medicines: Structural Phytochemistry Meets Biodiversity-An Update and Forward Look. Molecules 2021, 26, 1836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, J.; Luís, Â.; Gallardo, E.; Duarte, A.P. Psychoactive Substances of Natural Origin: Toxicological Aspects, Therapeutic Properties and Analysis in Biological Samples. Molecules 2021, 26, 1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devereaux, A.L.; Mercer, S.L.; Cunningham, C.W. DARK Classics in Chemical Neuroscience: Morphine. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2018, 9, 2395–2407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiménez-Madrona, E.; Morado-Díaz, C.J.; Talaverón, R.; Tabernero, A.; Pastor, A.M.; Sáez, J.C.; Matarredona, E.R. Antiproliferative Effect of Boldine on Neural Progenitor Cells and on Glioblastoma Cells. Front. Neurosci. 2023, 17, 1211467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.; Niu, J.; Jiang, J.; Dong, T.; Chen, Y.; Yang, X.; Liu, P. Chelerythrine Inhibits the Progression of Glioblastoma by Suppressing the TGFB1-ERK1/2/Smad2/3-Snail/ZEB1 Signaling Pathway. Life Sci. 2022, 293, 120358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, T.C.C.; de Faria Lopes, G.P.; Menezes-Filho, N.d.J.; de Oliveira, D.M.; Pereira, E.; Pitanga, B.P.S.; Dos Santos Costa, R.; da Silva Velozo, E.; Freire, S.M.; Clarêncio, J.; et al. Specific Cytostatic and Cytotoxic Effect of Dihydrochelerythrine in Glioblastoma Cells: Role of NF-κB/β-Catenin and STAT3/IL-6 Pathways. Anticancer Agents Med. Chem. 2018, 18, 1386–1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, M.; Wang, Y.; Guo, Y.; Yu, P.; Sun, Y.; Song, Y.; Zhao, L. Nitidine Chloride Suppresses Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition and Stem Cell-like Properties in Glioblastoma by Regulating JAK2/STAT3 Signaling. Cancer Med. 2021, 10, 3113–3128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, P.; Zheng, S.-Y.; Jiang, R.-L.; Wu, H.-D.; Li, Y.-A.; Lu, J.-L.; Xiong, Y.; Han, B.; Lin, L. Necroptosis Signaling and Mitochondrial Dysfunction Cross-Talking Facilitate Cell Death Mediated by Chelerythrine in Glioma. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2023, 202, 76–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.-H.; Wang, Q.-Z.; Liu, T.; Bai, R.; Ma, M.-M.; Liu, Q.-L.; Zhou, H.-G.; Liu, J.; Wang, M. Enhanced Glioblastoma Selectivity of Harmine via the Albumin Carrier. J. Biomed. Nanotechnol. 2022, 18, 1052–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.-G.; Lv, Y.-X.; Guo, C.-Y.; Xiao, Z.-M.; Jiang, Q.-G.; Kuang, H.; Zhang, W.-H.; Hu, P. Harmine Inhibits the Proliferation and Migration of Glioblastoma Cells via the FAK/AKT Pathway. Life Sci. 2021, 270, 119112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vahedi, M.M.; Shahini, A.; Mottahedi, M.; Garousi, S.; Shariat Razavi, S.A.; Pouyamanesh, G.; Afshari, A.R.; Ferns, G.A.; Bahrami, A. Harmaline Exerts Potentially Anti-Cancer Effects on U-87 Human Malignant Glioblastoma Cells in Vitro. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2023, 50, 4357–4366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, C.-L.; Ma, Y.-S.; Hsia, T.-C.; Chou, Y.-C.; Lien, J.-C.; Peng, S.-F.; Kuo, C.-L.; Hsu, F.-T. Tetrandrine Suppresses Human Brain Glioblastoma GBM 8401/Luc2 Cell-Xenografted Subcutaneous Tumors in Nude Mice In Vivo. Molecules 2021, 26, 7105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Y.-W.; Cheng, H.-Y.; Kuo, C.-L.; Way, T.-D.; Lien, J.-C.; Chueh, F.-S.; Lin, Y.-L.; Chung, J.-G. Tetrandrine Inhibits Human Brain Glioblastoma Multiforme GBM 8401 Cancer Cell Migration and Invasion in Vitro. Environ. Toxicol. 2019, 34, 364–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Wen, Y.-L.; Ma, J.-W.; Ye, J.-C.; Wang, X.; Huang, J.-X.; Meng, C.-Y.; Xu, X.-Z.; Wang, S.-X.; Zhong, X.-Y. Tetrandrine Inhibits Glioma Stem-like Cells by Repressing β-Catenin Expression. Int. J. Oncol. 2017, 50, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Liu, X.; Guo, S. Network Pharmacology-Based Strategy to Investigate the Effect and Mechanism of α-Solanine against Glioma. BMC Complement. Med. Ther. 2023, 23, 371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zou, S.; Lan, Y.-L.; Xing, J.-S.; Lan, X.-Q.; Zhang, B. Solasonine Inhibits Glioma Growth through Anti-Inflammatory Pathways. Am. J. Transl. Res. 2017, 9, 3977–3989. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Zhu, R.; Xu, L.; Xie, H.Q.; Zhao, B. Rutaecarpine Inhibits U87 Glioblastoma Cell Migration by Activating the Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor Signaling Pathway. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2021, 14, 765712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Wang, Q.; Lv, C.; Liu, Z.; Gao, H.; Chen, Y.; Zhao, G. Brucine Inhibits Proliferation of Glioblastoma Cells by Targeting the G-Quadruplexes in the c-Myb Promoter. J. Cancer 2021, 12, 1990–1999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.; Zhang, J.; Pan, Y.; Shen, W. Berberine Suppressed the Progression of Human Glioma Cells by Inhibiting the TGF-Β1/SMAD2/3 Signaling Pathway. Integr. Cancer Ther. 2022, 21, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, F.; Xie, T.; Huang, X.; Zhao, X. Berberine Inhibits Angiogenesis in Glioblastoma Xenografts by Targeting the VEGFR2/ERK Pathway. Pharm. Biol. 2018, 56, 665–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnarelli, A.; Natali, M.; Garcia-Gil, M.; Pesi, R.; Tozzi, M.G.; Ippolito, C.; Bernardini, N.; Vignali, R.; Batistoni, R.; Bianucci, A.M.; et al. Cell-Specific Pattern of Berberine Pleiotropic Effects on Different Human Cell Lines. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 10599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Qi, Q.; Feng, Z.; Zhang, X.; Huang, B.; Chen, A.; Prestegarden, L.; Li, X.; Wang, J. Berberine Induces Autophagy in Glioblastoma by Targeting the AMPK/mTOR/ULK1-Pathway. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 66944–66958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Xu, X.; Zhao, M.; Wei, Z.; Li, X.; Zhang, X.; Liu, Z.; Gong, Y.; Shao, C. Berberine Induces Senescence of Human Glioblastoma Cells by Downregulating the EGFR-MEK-ERK Signaling Pathway. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2015, 14, 355–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bibak, B.; Shakeri, F.; Keshavarzi, Z.; Mollazadeh, H.; Javid, H.; Jalili-Nik, M.; Sathyapalan, T.; Afshari, A.R.; Sahebkar, A. Anticancer Mechanisms of Berberine: A Good Choice for Glioblastoma Multiforme Therapy. Curr. Med. Chem. 2022, 29, 4507–4528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Och, A.; Podgórski, R.; Nowak, R. Biological Activity of Berberine—A Summary Update. Toxins 2020, 12, 713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauf, A.; Abu-Izneid, T.; Khalil, A.A.; Imran, M.; Shah, Z.A.; Emran, T.B.; Mitra, S.; Khan, Z.; Alhumaydhi, F.A.; Aljohani, A.S.M.; et al. Berberine as a Potential Anticancer Agent: A Comprehensive Review. Molecules 2021, 26, 7368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Zhang, P.; Kiang, K.M.Y.; Cheng, Y.S.; Leung, G.K.K. Caffeine Sensitizes U87-MG Human Glioblastoma Cells to Temozolomide through Mitotic Catastrophe by Impeding G2 Arrest. BioMed Res. Int. 2018, 2018, 5364973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.-C.; Ding, Y.-M.; Hueng, D.-Y.; Chen, J.-Y.; Chen, Y. Caffeine Suppresses the Progression of Human Glioblastoma via Cathepsin B and MAPK Signaling Pathway. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2016, 33, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.-D.; Song, L.-J.; Yan, D.-J.; Feng, Y.-Y.; Zang, Y.-G.; Yang, Y. Caffeine Inhibits the Growth of Glioblastomas through Activating the Caspase-3 Signaling Pathway in Vitro. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2015, 19, 3080–3088. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, J.; Lan, Y.-Q.; Zhang, T.; Yu, M.; Liu, X.-Y.; Li, L.-H.; Chen, X.-P. The in Vitro Effects of Caffeine on Viability, Cycle Cycle Profiles, Proliferation, and Apoptosis of Glioblastomas. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2015, 19, 3201–3207. [Google Scholar]

- Bonafé, G.A.; Boschiero, M.N.; Sodré, A.R.; Ziegler, J.V.; Rocha, T.; Ortega, M.M. Natural Plant Compounds: Does Caffeine, Dipotassium Glycyrrhizinate, Curcumin, and Euphol Play Roles as Antitumoral Compounds in Glioblastoma Cell Lines? Front. Neurol. 2021, 12, 784330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Pérez, D.; Reyes-Vidal, I.; Chávez-Cortez, E.G.; Sotelo, J.; Magaña-Maldonado, R. Methylxanthines: Potential Therapeutic Agents for Glioblastoma. Pharmaceuticals 2019, 12, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, F.; Han, D.-F.; Cao, B.-Q.; Wang, B.; Dong, N.; Jiang, D.-H. Caffeine-Induced Nuclear Translocation of FoxO1 Triggers Bim-Mediated Apoptosis in Human Glioblastoma Cells. Tumour Biol. 2016, 37, 3417–3423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inada, M.; Sato, A.; Shindo, M.; Yamamoto, Y.; Akasaki, Y.; Ichimura, K.; Tanuma, S.-I. Anticancer Non-Narcotic Opium Alkaloid Papaverine Suppresses Human Glioblastoma Cell Growth. Anticancer Res. 2019, 39, 6743–6750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inada, M.; Shindo, M.; Kobayashi, K.; Sato, A.; Yamamoto, Y.; Akasaki, Y.; Ichimura, K.; Tanuma, S.-I. Anticancer Effects of a Non-Narcotic Opium Alkaloid Medicine, Papaverine, in Human Glioblastoma Cells. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0216358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, S.; Carvalho, Â.R.; Pittol, V.; Dietrich, F.; Manica, F.; Machado, M.M.; de Oliveira, L.F.S.; Oliveira Battastini, A.M.; Ortega, G.G. Genotoxicity and Cytotoxicity of Oxindole Alkaloids from Uncaria Tomentosa (Cat’s Claw): Chemotype Relevance. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2016, 189, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szoka, L.; Palka, J. Capsaicin Up-Regulates pro-Apoptotic Activity of Thiazolidinediones in Glioblastoma Cell Line. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2020, 132, 110741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hacioglu, C.; Kar, F. Capsaicin Induces Redox Imbalance and Ferroptosis through ACSL4/GPx4 Signaling Pathways in U87-MG and U251 Glioblastoma Cells. Metab. Brain Dis. 2023, 38, 393–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz-Vidal, T.; Armenta-Pérez, V.P.; Rosales-Rivera, L.C.; Basulto-Padilla, G.C.; Martínez-Pérez, R.B.; Mateos-Díaz, J.C.; Gutiérrez-Mercado, Y.K.; Canales-Aguirre, A.A.; Rodríguez, J.A. Long Chain Capsaicin Analogues Synthetized by CALB-CLEAs Show Cytotoxicity on Glioblastoma Cell Lines. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2024, 108, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Q.; Niu, W.; Mu, M.; Ye, C.; Wu, P.; Hu, S.; Niu, C. Lycorine Hydrochloride Interferes with Energy Metabolism to Inhibit Chemoresistant Glioblastoma Multiforme Cell Growth through Suppressing PDK3. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2024, 480, 355–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Zhang, T.; Cheng, Z.; Zhu, N.; Wang, H.; Lin, L.; Wang, Z.; Yi, H.; Hu, M. Lycorine Inhibits Glioblastoma Multiforme Growth through EGFR Suppression. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2018, 37, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, J.; Huo, M.; Xu, F.; Ding, L. Molecular Mechanism of Lycorine in the Treatment of Glioblastoma Based on Network Pharmacology and Molecular Docking. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg’s Arch. Pharmacol. 2024, 397, 1551–1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Deng, D.; Shao, N.; Xu, Y.; Xue, L.; Peng, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhi, F. Evodiamine Activates Cellular Apoptosis through Suppressing PI3K/AKT and Activating MAPK in Glioma. Onco Targets Ther. 2018, 11, 1183–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.; Bi, Y.; Qazi, J.I.; Fan, L.; Gao, H. Evodiamine Sensitizes U87 Glioblastoma Cells to TRAIL via the Death Receptor Pathway. Mol. Med. Rep. 2015, 11, 257–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.-S.; Chien, C.-C.; Liu, K.-H.; Chen, Y.-C.; Chiu, W.-T. Evodiamine Prevents Glioma Growth, Induces Glioblastoma Cell Apoptosis and Cell Cycle Arrest through JNK Activation. Am. J. Chin. Med. 2017, 45, 879–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, Z.; Wang, L.; Wang, X.; Zhao, B.; Zhao, W.; Bhardwaj, S.S.; Ye, J.; Yin, Z.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, S. Oxymatrine Induces Cell Cycle Arrest and Apoptosis and Suppresses the Invasion of Human Glioblastoma Cells through the EGFR/PI3K/Akt/mTOR Signaling Pathway and STAT3. Oncol. Rep. 2018, 40, 867–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Wang, B.; Wang, J.; Ling, X.; Li, Q.; Meng, W.; Ma, J. Oxymatrine Inhibits Proliferation and Migration While Inducing Apoptosis in Human Glioblastoma Cells. BioMed Res. Int. 2016, 2016, 1784161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Li, H.; Sun, Z.; Dong, L.; Gao, L.; Liu, C.; Wang, X. Kukoamine A Inhibits Human Glioblastoma Cell Growth and Migration through Apoptosis Induction and Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition Attenuation. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 36543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bensalma, S.; Chadeneau, C.; Legigan, T.; Renoux, B.; Gaillard, A.; de Boisvilliers, M.; Pinet-Charvet, C.; Papot, S.; Muller, J.M. Evaluation of Cytotoxic Properties of a Cyclopamine Glucuronide Prodrug in Rat Glioblastoma Cells and Tumors. J. Mol. Neurosci. 2015, 55, 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Fu, R.; Duan, D.; Li, Z.; Li, B.; Ming, Y.; Li, L.; Ni, R.; Chen, J. Cyclovirobuxine D Induces Apoptosis and Mitochondrial Damage in Glioblastoma Cells Through ROS-Mediated Mitochondrial Translocation of Cofilin. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 656184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, K.-M.; Liu, J.-J.; Li, C.-C.; Cheng, C.-C.; Hsieh, Y.-T.; Chai, K.M.; Lien, Y.-A.; Tzeng, S.-F. Colchicine Derivative as a Potential Anti-Glioma Compound. J. Neuro-Oncol. 2015, 124, 403–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zottel, A.; Jovčevska, I.; Šamec, N.; Komel, R. Cytoskeletal Proteins as Glioblastoma Biomarkers and Targets for Therapy: A Systematic Review. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2021, 160, 103283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbassi, R.H.; Recasens, A.; Indurthi, D.C.; Johns, T.G.; Stringer, B.W.; Day, B.W.; Munoz, L. Lower Tubulin Expression in Glioblastoma Stem Cells Attenuates Efficacy of Microtubule-Targeting Agents. ACS Pharmacol. Transl. Sci. 2019, 2, 402–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carone, C.; Genedani, S.; Leo, G.; Filaferro, M.; Fuxe, K.; Agnati, L.F. In Vitro Effects of Cocaine on Tunneling Nanotube Formation and Extracellular Vesicle Release in Glioblastoma Cell Cultures. J. Mol. Neurosci. 2015, 55, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steinmetz, A.; Steffens, L.; Morás, A.M.; Prezzi, F.; Braganhol, E.; Saffi, J.; Ortiz, R.S.; Barros, H.M.T.; Moura, D.J. In Vitro Model to Study Cocaine and Its Contaminants. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2018, 285, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, K.-J.; Yu, M.O.; Park, D.-H.; Park, J.-Y.; Chung, Y.-G.; Kang, S.-H. Role of Vincristine in the Inhibition of Angiogenesis in Glioblastoma. Neurol. Res. 2016, 38, 871–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Fan, Y.; Lv, S.; Xiao, B.; Ye, M.; Zhu, X. Vincristine and Temozolomide Combined Chemotherapy for the Treatment of Glioma: A Comparison of Solid Lipid Nanoparticles and Nanostructured Lipid Carriers for Dual Drugs Delivery. Drug Deliv. 2016, 23, 2720–2725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filippi-Chiela, E.C.; Vargas, J.E.; Bueno, E.; Silva, M.M.; Thomé, M.P.; Lenz, G. Vincristine Promotes Differential Levels of Apoptosis, Mitotic Catastrophe, and Senescence Depending on the Genetic Background of Glioblastoma Cells. Toxicol. Vitr. 2022, 85, 105472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altinoz, M.A.; Topcu, G.; Hacimuftuoglu, A.; Ozpinar, A.; Ozpinar, A.; Hacker, E.; Elmaci, İ. Noscapine, a Non-Addictive Opioid and Microtubule-Inhibitor in Potential Treatment of Glioblastoma. Neurochem. Res. 2019, 44, 1796–1806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhuang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, M.; Yao, L. The Recent Developments of Camptothecin and Its Derivatives as Potential Anti-Tumor Agents. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2023, 260, 115710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, A.; Gandhi, A.; Fimognari, C.; Atanasov, A.G.; Bishayee, A. Alkaloids for Cancer Prevention and Therapy: Current Progress and Future Perspectives. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2019, 858, 172472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turrini, E.; Sestili, P.; Fimognari, C. Overview of the Anticancer Potential of the “King of Spices” Piper Nigrum and Its Main Constituent Piperine. Toxins 2020, 12, 747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeong, S.; Jung, S.; Park, G.-S.; Shin, J.; Oh, J.-W. Piperine Synergistically Enhances the Effect of Temozolomide against Temozolomide-Resistant Human Glioma Cell Lines. Bioengineered 2020, 11, 791–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, J.; Yin, W.; Huo, M.; Yao, Q.; Ding, L. Induction of Apoptosis in Glioma Cells by Lycorine via Reactive Oxygen Species Generation and Regulation of NF-κB Pathways. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg’s Arch. Pharmacol. 2023, 396, 1247–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warrier, N.M.; Krishnan, R.K.; Prabhu, V.; Hariharapura, R.C.; Agarwal, P.; Kumar, P. Survivin Inhibition by Piperine Sensitizes Glioblastoma Cancer Stem Cells and Leads to Better Drug Response. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 7604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diehl, S.; Hildebrandt, G.; Manda, K. Pepper Alkaloid Piperine Increases Radiation Sensitivity of Cancer Cells from Glioblastoma and Hypopharynx In Vitro. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 8548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nellan, A.; Wright, E.; Campbell, K.; Davies, K.D.; Donson, A.M.; Amani, V.; Judd, A.; Hemenway, M.S.; Raybin, J.; Foreman, N.K.; et al. Retrospective Analysis of Combination Carboplatin and Vinblastine for Pediatric Low-Grade Glioma. J. Neuro-Oncol. 2020, 148, 569–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vairy, S.; Le Teuff, G.; Bautista, F.; De Carli, E.; Bertozzi, A.-I.; Pagnier, A.; Fouyssac, F.; Nysom, K.; Aerts, I.; Leblond, P.; et al. Phase I Study of Vinblastine in Combination with Nilotinib in Children, Adolescents, and Young Adults with Refractory or Recurrent Low-Grade Glioma. Neuro-Oncol. Adv. 2020, 2, vdaa075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roux, C.; Revon-Rivière, G.; Gentet, J.C.; Verschuur, A.; Scavarda, D.; Saultier, P.; Appay, R.; Padovani, L.; André, N. Metronomic Maintenance With Weekly Vinblastine After Induction With Bevacizumab-Irinotecan in Children With Low-Grade Glioma Prevents Early Relapse. J. Pediatr. Hematol. Oncol. 2021, 43, e630–e634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, C.; Ai, J.; Ren, E.; Li, J.; Feng, C.; Li, X.; Luo, X. Research Progress on Evodiamine, a Bioactive Alkaloid of Evodiae Fructus: Focus on Its Anti-Cancer Activity and Bioavailability (Review). Exp. Ther. Med. 2021, 22, 1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkaria, J.N.; Hu, L.S.; Parney, I.F.; Pafundi, D.H.; Brinkmann, D.H.; Laack, N.N.; Giannini, C.; Burns, T.C.; Kizilbash, S.H.; Laramy, J.K.; et al. Is the Blood-Brain Barrier Really Disrupted in All Glioblastomas? A Critical Assessment of Existing Clinical Data. Neuro-Oncology 2018, 20, 184–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmustine Medac (Previously Carmustine Obvius)|European Medicines Agency (EMA). Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/carmustine-medac (accessed on 28 December 2024).

- Temodal|European Medicines Agency (EMA). Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/temodal (accessed on 28 December 2024).

- Zhou, Y.; Jia, P.; Fang, Y.; Zhu, W.; Gong, Y.; Fan, T.; Yin, J. Comprehensive Understanding of the Adverse Effects Associated with Temozolomide: A Disproportionate Analysis Based on the FAERS Database. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1437436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Fei, Y.; Qu, H.; Zhang, H.; Wang, Y.; Wu, Z.; Fan, G. Five Years of Safety Profile of Bevacizumab: An Analysis of Real-World Pharmacovigilance and Randomized Clinical Trials. J. Pharm. Health Care Sci. 2024, 10, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Majchrzak-Celińska, A.; Studzińska-Sroka, E. New Avenues and Major Achievements in Phytocompounds Research for Glioblastoma Therapy. Molecules 2024, 29, 1682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dey, P.; Kundu, A.; Chakraborty, H.J.; Kar, B.; Choi, W.S.; Lee, B.M.; Bhakta, T.; Atanasov, A.G.; Kim, H.S. Therapeutic Value of Steroidal Alkaloids in Cancer: Current Trends and Future Perspectives. Int. J. Cancer 2019, 145, 1731–1744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tilaoui, M.; Ait Mouse, H.; Zyad, A. Update and New Insights on Future Cancer Drug Candidates From Plant-Based Alkaloids. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 719694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cragg, G.M.; Newman, D.J. Antineoplastic Agents from Natural Sources: Achievements and Future Directions. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs 2000, 9, 2783–2797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varela, C.; Silva, F.; Costa, G.; Cabral, C. Chapter 1—Alkaloids: Their Relevance in Cancer Treatment. In New Insights into Glioblastoma; Vitorino, C., Balaña, C., Cabral, C., Eds.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 361–401. ISBN 978-0-323-99873-4. [Google Scholar]

- Zishan, M.; Saidurrahman, S.; Anayatullah, A.; Azeemuddin, A.; Ahmad, Z.; Hussain, M.W. Natural Products Used as Anti-Cancer Agents. J. Drug Deliv. Ther. 2017, 7, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ferreira, M.-J.U. Alkaloids in Future Drug Discovery. Molecules 2022, 27, 1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhyani, P.; Quispe, C.; Sharma, E.; Bahukhandi, A.; Sati, P.; Attri, D.C.; Szopa, A.; Sharifi-Rad, J.; Docea, A.O.; Mardare, I.; et al. Anticancer Potential of Alkaloids: A Key Emphasis to Colchicine, Vinblastine, Vincristine, Vindesine, Vinorelbine and Vincamine. Cancer Cell Int. 2022, 22, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gach-Janczak, K.; Drogosz-Stachowicz, J.; Janecka, A.; Wtorek, K.; Mirowski, M. Historical Perspective and Current Trends in Anticancer Drug Development. Cancers 2024, 16, 1878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, C.; Mitchell, E.P.; Hoff, P.M. Irinotecan in the Treatment of Colorectal Cancer. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2006, 32, 491–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.H.; Kim, S.-W.; Suh, C.; Lee, J.-S.; Lee, J.H.; Lee, S.-J.; Ryoo, B.Y.; Park, K.; Kim, J.S.; Heo, D.S.; et al. Belotecan, New Camptothecin Analogue, Is Active in Patients with Small-Cell Lung Cancer: Results of a Multicenter Early Phase II Study. Ann. Oncol. 2008, 19, 123–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McBain, C.; Lawrie, T.A.; Rogozińska, E.; Kernohan, A.; Robinson, T.; Jefferies, S. Treatment Options for Progression or Recurrence of Glioblastoma: A Network Meta-Analysis. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2021, 5, CD013579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Upadhyayula, P.S.; Spinazzi, E.F.; Argenziano, M.G.; Canoll, P.; Bruce, J.N. Convection Enhanced Delivery of Topotecan for Gliomas: A Single-Center Experience. Pharmaceutics 2020, 13, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Food and Drug Administration. FDA Approves Irinotecan Liposome for First-Line Treatment of Metastatic Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma; Food and Drug Administration: Silver Spring, MD, USA, 2024.

- O’Brien, S.; Kantarjian, H.; Keating, M.; Beran, M.; Koller, C.; Robertson, L.E.; Hester, J.; Rios, M.B.; Andreeff, M.; Talpaz, M. Homoharringtonine Therapy Induces Responses in Patients with Chronic Myelogenous Leukemia in Late Chronic Phase. Blood 1995, 86, 3322–3326. [Google Scholar]

- Leonard, A.; Wolff, J.E. Etoposide Improves Survival in High-Grade Glioma: A Meta-Analysis. Anticancer Res. 2013, 33, 3307–3315. [Google Scholar]

- Mosca, L.; Ilari, A.; Fazi, F.; Assaraf, Y.G.; Colotti, G. Taxanes in Cancer Treatment: Activity, Chemoresistance and Its Overcoming. Drug Resist. Updates 2021, 54, 100742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rankovic, Z. CNS Drug Design: Balancing Physicochemical Properties for Optimal Brain Exposure. J. Med. Chem. 2015, 58, 2584–2608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz, J.A.; Hartz, A.M.S.; Bauer, B. ABCB1 and ABCG2 Regulation at the Blood-Brain Barrier: Potential New Targets to Improve Brain Drug Delivery. Pharmacol. Rev. 2023, 75, 815–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbott, N.J.; Patabendige, A.A.K.; Dolman, D.E.M.; Yusof, S.R.; Begley, D.J. Structure and Function of the Blood-Brain Barrier. Neurobiol. Dis. 2010, 37, 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, F.; Xiong, N.; Xu, H.; Chai, S.; Wang, H.; Wang, J.; Zhao, H.; Jiang, X.; Fu, P.; et al. Remodelling and Treatment of the Blood-Brain Barrier in Glioma. Cancer Manag. Res. 2021, 13, 4217–4232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noorani, I.; de la Rosa, J. Breaking Barriers for Glioblastoma with a Path to Enhanced Drug Delivery. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 5909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, M.; Blaney, S.; Balis, F.M. Pharmacokinetics of drug delivery to the central nervous system. In A Clinician’s Guide to Chemotherapy Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics; Grochow, L.B., Ames, M.M., Eds.; Williams & Wilkins, a Waverly Company: Baltimore, MD, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, D.; Chen, Q.; Chen, X.; Han, F.; Chen, Z.; Wang, Y. The blood–brain barrier: Structure, regulation, and drug delivery. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardridge, W.M. The blood-brain barrier: Bottleneck in brain drug development. NeuroRx 2005, 2, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardridge, W.M. Drug transport across the blood-brain barrier. J. Cereb. Blood Flow. Metab. 2012, 32, 1959–1972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mulvihill, J.J.; Cunnane, E.M.; Ross, A.M.; Duskey, J.T.; Tosi, G.; Grabrucker, A.M. Drug delivery across the blood-brain barrier: Recent advances in the use of nanocarriers. Nanomedicine 2020, 15, 205–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.-L.; Liu, S.; Jiang, Y.; Gu, L.-Y.; Xiao, Y.; Wang, X.; Cheng, L.; Li, X.-T. Targeting Vincristine plus Tetrandrine Liposomes Modified with DSPE-PEG2000-Transferrin in Treatment of Brain Glioma. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2017, 96, 129–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.-F.; Liu, Y.-S.; Huang, Y.-C.; Chi, C.-W.; Tsai, C.-C.; Tsai, T.-H.; Chen, Y.-J. Borneol and Tetrandrine Modulate the Blood-Brain Barrier and Blood-Tumor Barrier to Improve the Therapeutic Efficacy of 5-Fluorouracil in Brain Metastasis. Integr. Cancer Ther. 2022, 21, 15347354221077682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seelig, A. P-Glycoprotein: One Mechanism, Many Tasks and the Consequences for Pharmacotherapy of Cancers. Front. Oncol. 2020, 10, 576559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.-N.; Yang, Y.-F.; Yang, X.-W. Blood-Brain Barrier Permeability and Neuroprotective Effects of Three Main Alkaloids from the Fruits of Euodia Rutaecarpa with MDCK-pHaMDR Cell Monolayer and PC12 Cell Line. Biomed Pharmacother. 2018, 98, 82–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luan, F.; He, X.; Zeng, N. Tetrandrine: A Review of Its Anticancer Potentials, Clinical Settings, Pharmacokinetics and Drug Delivery Systems. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2020, 72, 1491–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iqbal, S.; Flux, C.; Briggs, D.A.; Deplazes, E.; Long, J.; Skrzypek, R.; Rothnie, A.; Kerr, I.D.; Callaghan, R. Vinca Alkaloid Binding to P-Glycoprotein Occurs in a Processive Manner. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. Biomembr. 2022, 1864, 184005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gai, Y.; Yang, N.; Chen, J. Inhibitory Activity of 8 Alkaloids on P-Gp and Their Distribution in Chinese Uncaria Species. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2020, 15, 1934578X20973506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, P.; Vishwakarma, R.A.; Bharate, S.B. Natural Alkaloids as P-Gp Inhibitors for Multidrug Resistance Reversal in Cancer. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2017, 138, 273–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, D.; Ajazuddin; Bhattacharya, S. Role of Natural P-Gp Inhibitor in the Effective Delivery for Chemotherapeutic Agents. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 149, 367–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Readi, M.Z.; Eid, S.; Abdelghany, A.A.; Al-Amoudi, H.S.; Efferth, T.; Wink, M. Resveratrol Mediated Cancer Cell Apoptosis, and Modulation of Multidrug Resistance Proteins and Metabolic Enzymes. Phytomedicine 2019, 55, 269–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewanjee, S.; Dua, T.K.; Bhattacharjee, N.; Das, A.; Gangopadhyay, M.; Khanra, R.; Joardar, S.; Riaz, M.; Feo, V.D.; Zia-Ul-Haq, M. Natural Products as Alternative Choices for P-Glycoprotein (P-Gp) Inhibition. Molecules 2017, 22, 871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravikumar Reddy, D.; Khurana, A.; Bale, S.; Ravirala, R.; Samba Siva Reddy, V.; Mohankumar, M.; Godugu, C. Natural Flavonoids Silymarin and Quercetin Improve the Brain Distribution of Co-Administered P-Gp Substrate Drugs. Springerplus 2016, 5, 1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Liu, Z. Progress in the Management of Acute Colchicine Poisoning in Adults. Intern. Emerg. Med. 2022, 17, 2069–2081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehan, S.; Arora, N.; Bhalla, S.; Khan, A.; Rehman, M.U.; Alghamdi, B.S.; Zughaibi, T.A.; Ashraf, G.M. Involvement of Phytochemical-Encapsulated Nanoparticles’ Interaction with Cellular Signalling in the Amelioration of Benign and Malignant Brain Tumours. Molecules 2022, 27, 3561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshammari, M.K.; Alghazwni, M.K.; Alharbi, A.S.; Alqurashi, G.G.; Kamal, M.; Alnufaie, S.R.; Alshammari, S.S.; Alshehri, B.A.; Tayeb, R.H.; Bougeis, R.J.M.; et al. Nanoplatform for the Delivery of Topotecan in the Cancer Milieu: An Appraisal of Its Therapeutic Efficacy. Cancers 2022, 15, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hiser, L.; Herrington, B.; Lobert, S. Effect of Noscapine and Vincristine Combination on Demyelination and Cell Proliferation in Vitro. Leuk. Lymphoma 2008, 49, 1603–1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landen, J.W.; Hau, V.; Wang, M.; Davis, T.; Ciliax, B.; Wainer, B.H.; Van Meir, E.G.; Glass, J.D.; Joshi, H.C.; Archer, D.R. Noscapine Crosses the Blood-Brain Barrier and Inhibits Glioblastoma Growth. Clin. Cancer Res. 2004, 10, 5187–5201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.-T.; Tang, W.; Xie, H.-J.; Liu, S.; Song, X.-L.; Xiao, Y.; Wang, X.; Cheng, L.; Chen, G.-R. The Efficacy of RGD Modified Liposomes Loaded with Vinorelbine plus Tetrandrine in Treating Resistant Brain Glioma. J. Liposome Res. 2019, 29, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, T.; Li, M.; Zheng, H.; Liu, W.; Zhang, J. Microdialysis Combined with RRLC-MS/MS for the Pharmacokinetics of Two Major Alkaloids of Bi Qi Capsule and the Potential Roles of P-Gp and BCRP on Their Penetration. J. Chromatogr. B Analyt. Technol. Biomed. Life Sci. 2018, 1092, 72–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, T.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, L.; Bai, X.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, X.; Chen, L.; Wang, L.; Cui, L. Pretreatment by Evodiamine Is Neuroprotective in Cerebral Ischemia: Up-Regulated pAkt, pGSK3β, Down-Regulated NF-κB Expression, and Ameliorated BBB Permeability. Neurochem. Res. 2014, 39, 1612–1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Yu, X.; Yang, L.; Xue, G.; Wei, Q.; Han, Z.; Chen, H. Research Progress on the Antitumor Effects of Harmine. Front. Oncol. 2024, 14, 1382142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miciaccia, M.; Rizzo, F.; Centonze, A.; Cavallaro, G.; Contino, M.; Armenise, D.; Baldelli, O.M.; Solidoro, R.; Ferorelli, S.; Scarcia, P.; et al. Harmaline to Human Mitochondrial Caseinolytic Serine Protease Activation for Pediatric Diffuse Intrinsic Pontine Glioma Treatment. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zetler, G.; Back, G.; Iven, H. Pharmacokinetics in the Rat of the Hallucinogenic Alkaloids Harmine and Harmaline. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg’s Arch. Pharmacol. 1974, 285, 273–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cisternino, S.; Rousselle, C.; Debray, M.; Scherrmann, J.-M. In Vivo Saturation of the Transport of Vinblastine and Colchicine by P-Glycoprotein at the Rat Blood-Brain Barrier. Pharm. Res. 2003, 20, 1607–1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drion, N.; Lemaire, M.; Lefauconnier, J.M.; Scherrmann, J.M. Role of P-Glycoprotein in the Blood-Brain Transport of Colchicine and Vinblastine. J. Neurochem. 1996, 67, 1688–1693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pranata, R.; Feraldho, A.; Lim, M.A.; Henrina, J.; Vania, R.; Golden, N.; July, J. Coffee and Tea Consumption and the Risk of Glioma: A Systematic Review and Dose-Response Meta-Analysis. Br. J. Nutr. 2022, 127, 78–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eigenmann, D.E.; Dürig, C.; Jähne, E.A.; Smieško, M.; Culot, M.; Gosselet, F.; Cecchelli, R.; Helms, H.C.C.; Brodin, B.; Wimmer, L.; et al. In Vitro Blood-Brain Barrier Permeability Predictions for GABAA Receptor Modulating Piperine Analogs. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2016, 103, 118–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, Y.; Chin Tan, T.M.; Lim, L.-Y. In Vitro and in Vivo Evaluation of the Effects of Piperine on P-Gp Function and Expression. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2008, 230, 283–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Z.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, P.; Luo, Z.; Li, J. Effect of Capsaicin-Loading Nanoparticles on Gliomas. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2015, 15, 9834–9839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weaver, T.; Nogrady, D.F. Medicinal chemistry. In A Molecular and Biochemical Approach; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Talevi, A. Central Nervous System Multiparameter Optimization Desirability. In The ADME Encyclopedia; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stéen, E.J.L.; Vugts, D.J.; Windhorst, A.D. The Application of in silico Methods for Prediction of Blood-Brain Barrier Permeability of Small Molecule PET Tracers. Front. Nucl. Med. 2022, 2, 853475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isabel, U.-V.; de la Belén, A.; Riera, M.; Serrano Dolores, R.; Elena, G.-B. A new frontier in neuropharmacology: Recent progress in natural products research for blood–brain barrier crossing. Curr. Res. Biotechnol. 2024, 8, 100235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsabri Sami, G.; Mari Walid, O.; Sara, Y.; Alsadawi Murad, A.; Oroszi Terry, L. Kinetic and Dynamic Description of Caffeine. J. Caffeine Adenosine Res. 2018, 8, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikeda-Murakami, K.; Tani, N.; Ikeda, T.; Aoki, Y.; Ishikawa, T. Central Nervous System Stimulants Limit Caffeine Transport at the Blood-Cerebrospinal Fluid Barrier. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 1862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Zhang, H.; Jia, L.; Zhang, Y.; Qin, R.; Xu, S.; Mei, Y. Health Benefits and Mechanisms of Theobromine. J. Funct. Foods 2024, 115, 106126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugimoto, N.; Katakura, M.; Matsuzaki, K.; Ohno-Shosaku, T.; Yachie, A.; Shido, O. Theobromine, the Primary Methylxanthine Found in Theobroma Cacao, Can Pass through the Blood-Brain Barrier in Mice. FASEB J. 2016, 30, lb635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugimoto, N.; Miwa, S.; Hitomi, Y.; Nakamura, H.; Tsuchiya, H.; Yachie, A. Theobromine, the Primary Methylxanthine Found in Theobroma Cacao, Prevents Malignant Glioblastoma Proliferation by Negatively Regulating Phosphodiesterase-4, Extracellular Signal-Regulated Kinase, Akt/Mammalian Target of Rapamycin Kinase, and Nuclear Factor-Kappa, B. Nutr. Cancer 2014, 66, 419–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Judelson, D.A.; Preston, A.G.; Miller, D.L.; Muñoz, C.X.; Kellogg, M.D.; Lieberman, H.R. Effects of Theobromine and Caffeine on Mood and Vigilance. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2013, 33, 499–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, D.; Wu, H.; Wei, Y.; Liu, W.; Huang, F.; Shi, H.; Zhang, B.; Wu, X.; Wang, C. Effects of Harmine, an Acetylcholinesterase Inhibitor, on Spatial Learning and Memory of APP/PS1 Transgenic Mice and Scopolamine-Induced Memory Impairment Mice. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2015, 768, 96–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, K. Black Pepper and Its Pungent Principle-Piperine: A Review of Diverse Physiological Effects. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2007, 47, 735–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tripathi, A.K.; Ray, A.K.; Mishra, S.K. Molecular and Pharmacological Aspects of Piperine as a Potential Molecule for Disease Prevention and Management: Evidence from Clinical Trials. Beni. Suef. Univ. J. Basic Appl. Sci. 2022, 11, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubey, R.K.; Leeners, B.; Imthurn, B.; Merki-Feld, G.S.; Rosselli, M. Piperine Decreases Binding of Drugs to Human Plasma and Increases Uptake by Brain Microvascular Endothelial Cells. Phytother. Res. 2017, 31, 1868–1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornton, T.; Mills, D.; Bliss, E. Capsaicin: A Potential Treatment to Improve Cerebrovascular Function and Cognition in Obesity and Ageing. Nutrients 2023, 15, 1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inyang, D.; Saumtally, T.; Nnadi, C.N.; Devi, S.; So, P.-W. A Systematic Review of the Effects of Capsaicin on Alzheimer’s Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 10176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saria, A.; Skofitsch, G.; Lembeck, F. Distribution of Capsaicin in Rat Tissues after Systemic Administration. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 1982, 34, 273–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 173 O’Neill, J.; Brock, C.; Olesen, A.E.; Andresen, T.; Nilsson, M.; Dickenson, A.H. Unravelling the Mystery of Capsaicin: A Tool to Understand and Treat Pain. Pharmacol. Rev. 2012, 64, 939–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pasierski, M.; Szulczyk, B. Beneficial Effects of Capsaicin in Disorders of the Central Nervous System. Molecules 2022, 27, 2484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donnerer, J.; Amann, R.; Schuligoi, R.; Lembeck, F. Absorption and Metabolism of Capsaicinoids Following Intragastric Administration in Rats. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg’s Arch. Pharmacol. 1990, 342, 357–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Salam, O.M.E.; Mózsik, G. Capsaicin, The Vanilloid Receptor TRPV1 Agonist in Neuroprotection: Mechanisms Involved and Significance. Neurochem. Res. 2023, 48, 3296–3315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Tao, Z.; Feng, M.; Li, X.; Deng, Z.; Zhao, G.; Yin, H.; Pan, T.; Chen, G.; Feng, Z.; et al. Dual PLK1 and STAT3 Inhibition Promotes Glioblastoma Cells Apoptosis through MYC. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2020, 533, 368–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhattacharjee, A.K.; Kondoh, T.; Nagashima, T.; Ikeda, M.; Ehara, K.; Tamaki, N. Quantitative Analysis of Papaverine-Mediated Blood-Brain Barrier Disruption in Rats. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2001, 289, 548–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.-H.; Yan, M.; Li, H.-D.; Fang, P.-F.; Liu, Y.-W. Influence of P-Glycoprotein on Brucine Transport at the in Vitro Blood-Brain Barrier. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2012, 690, 68–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Vega, J.; Gómez-Alonso, S.; Pérez-Navarro, J.; Pastene-Navarrete, E. Green Extraction of Alkaloids and Polyphenols from Peumus Boldus Leaves with Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents and Profiling by HPLC-PDA-IT-MS/MS and HPLC-QTOF-MS/MS. Plants 2020, 9, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazemi Noureini, S.; Tanavar, F. Boldine, a Natural Aporphine Alkaloid, Inhibits Telomerase at Non-Toxic Concentrations. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2015, 231, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennisi, G.; Bruzzaniti, P.; Burattini, B.; Piaser Guerrato, G.; Della Pepa, G.M.; Sturiale, C.L.; Lapolla, P.; Familiari, P.; La Pira, B.; D’Andrea, G.; et al. Advancements in Telomerase-Targeted Therapies for Glioblastoma: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 8700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Huang, H.; Zhan, Z.; Gao, H.; Zhang, C.; Lai, J.; Cao, J.; Li, C.; Chen, Y.; Liu, Z. Berberine Inhibits Glioma Cell Migration and Invasion by Suppressing TGF-Β1/COL11A1 Pathway. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2022, 625, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Chen, Y.; Gao, H.; Xu, W.; Zhang, C.; Lai, J.; Liu, X.; Sun, Y.; Huang, H. Berberine Inhibits Cell Proliferation by Interfering with Wild-Type and Mutant P53 in Human Glioma Cells. Onco Targets Ther. 2020, 13, 12151–12162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, N.; Qi, Y.; Ma, X.; Xiao, X.; Liu, Q.; Xia, T.; Xiang, J.; Zeng, J.; Tang, J. Rediscovery of Traditional Plant Medicine: An Underestimated Anticancer Drug of Chelerythrine. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 906301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golán-Cancela, I.; Caja, L. The TGF-β Family in Glioblastoma. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, W.; Hou, X.; Dong, L.; Hou, W. Roles of STAT3 in the Pathogenesis and Treatment of Glioblastoma. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2023, 11, 1098482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luwor, R.B.; Stylli, S.S.; Kaye, A.H. The Role of Stat3 in Glioblastoma Multiforme. J. Clin. Neurosci. 2013, 20, 907–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Z.; Yang, P.; Zhou, Q. Multiple Biological Functions and Pharmacological Effects of Lycorine. Sci. China Chem. 2013, 56, 1382–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuo, Y.-H.; Chan, T.-C.; Lai, H.-Y.; Chen, T.-J.; Wu, L.-C.; Hsing, C.-H.; Li, C.-F. Overexpression of Pyruvate Dehydrogenase Kinase-3 Predicts Poor Prognosis in Urothelial Carcinoma. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 749142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Li, L.; Liu, L.; Zhu, Z.; Yu, Y.; Zhan, S.; Luo, Z.; Li, Y.; Long, H.; Cai, J.; et al. PDK3 Drives Colorectal Carcinogenesis and Immune Evasion and Is a Therapeutic Target for Boosting Immunotherapy. Am. J. Cancer Res. 2024, 14, 3117–3129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Z.; Li, X.; Chen, H.; Zeng, A.; Shi, Y.; Tang, Y. The lncRNA-DLEU2/miR-186-5p/PDK3 Axis Promotes the Progress of Glioma Cells. Am. J. Transl. Res. 2019, 11, 4922–4934. [Google Scholar]

- Roy, M.; Liang, L.; Xiao, X.; Feng, P.; Ye, M.; Liu, J. Lycorine: A Prospective Natural Lead for Anticancer Drug Discovery. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2018, 107, 615–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soleimani, A.; Rahmani, F.; Ferns, G.A.; Ryzhikov, M.; Avan, A.; Hassanian, S.M. Role of the NF-κB Signaling Pathway in the Pathogenesis of Colorectal Cancer. Gene 2020, 726, 144132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahukari, R.; Punabaka, J.; Bhasha, S.; Ganjikunta, V.S.; Ramudu, S.K.; Kesireddy, S.R. Plant Compounds for the Treatment of Diabetes, a Metabolic Disorder: NF-κB as a Therapeutic Target. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2020, 26, 4955–4969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khabibov, M.; Garifullin, A.; Boumber, Y.; Khaddour, K.; Fernandez, M.; Khamitov, F.; Khalikova, L.; Kuznetsova, N.; Kit, O.; Kharin, L. Signaling Pathways and Therapeutic Approaches in Glioblastoma Multiforme (Review). Int. J. Oncol. 2022, 60, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, J.; Ding, K.; Luo, T.; Zhang, X.; Chen, A.; Zhang, D.; Li, G.; Thorsen, F.; Huang, B.; Li, X.; et al. TRIM22 Activates NF-κB Signaling in Glioblastoma by Accelerating the Degradation of IκBα. Cell Death Differ. 2021, 28, 367–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parasramka, S.; Talari, G.; Rosenfeld, M.; Guo, J.; Villano, J.L. Procarbazine, Lomustine and Vincristine for Recurrent High-Grade Glioma. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 7, CD011773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Chen, J.-C.; Tseng, S.-H. Tetrandrine Suppresses Tumor Growth and Angiogenesis of Gliomas in Rats. Int. J. Cancer 2009, 124, 2260–2269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manoranjan, B.; Provias, J.P. β-Catenin Marks Proliferating Endothelial Cells in Glioblastoma. J. Clin. Neurosci. 2022, 98, 203–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, R.; Wang, T.; Zhou, G.; Xu, M.; Yu, X.; Zhang, X.; Sui, F.; Li, C.; Tang, L.; Wang, Z. Botany, Phytochemistry, Pharmacology and Toxicity of Strychnos Nux-Vomica L.: A Review. Am. J. Chin. Med. 2018, 46, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senrung, A.; Tripathi, T.; Yadav, J.; Janjua, D.; Chaudhary, A.; Chhokar, A.; Aggarwal, N.; Joshi, U.; Goswami, N.; Bharti, A.C. In Vivo Antiangiogenic Effect of Nimbolide, Trans-Chalcone and Piperine for Use against Glioblastoma. BMC Cancer 2023, 23, 1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javed, B.; Zhao, X.; Cui, D.; Curtin, J.; Tian, F. Enhanced Anticancer Response of Curcumin- and Piperine-Loaded Lignin-g-p (NIPAM-Co-DMAEMA) Gold Nanogels against U-251 MG Glioblastoma Multiforme. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, L.-Y.; Zhang, Y.-L.; Yang, R.; Wang, Z.-C.; Lu, Y.-D.; Wang, B.-Z.; Zhu, H.-L. Tubulin Inhibitors Binding to Colchicine-Site: A Review from 2015 to 2019. Curr. Med. Chem. 2020, 27, 6787–6814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nandre, R.M.; Terse, P.S. An overview of immunotoxicity in drug discovery and development. Toxicol. Lett. 2025, 403, 66–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, N.; Vayer, P.; Tanwar, S.; Poyet, J.-L.; Tsaioun, K.; Villoutreix, B.O. Drug discovery and development: Introduction to the general public and patient groups. Front. Drug. Discov. 2023, 3, 1201419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, D.; Sanap, G.; Shenoy, S.; Kalyane, D.; Kalia, K.; Tekade, R.K. Artificial intelligence in drug discovery and development. Drug Discov. Today 2021, 26, 80–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Y.; Liu, X.; Wu, N.; Han, Y.; Wang, J.; Yu, Y.; Chen, Q. Efficacy and Safety of Berberine Alone for Several Metabolic Disorders: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Clinical Trials. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 653887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, Q.; Li, M.; Huang, C.; Yuan, Y.; Liang, Q.; Ma, X.; Qiu, T.; Li, J. The Clinical Efficacy and Safety of Berberine in the Treatment of Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: A Meta-Analysis and Systematic Review. J. Transl. Med. 2024, 22, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lau, Y.S.; Ling, W.C.; Murugan, D.; Mustafa, M.R. Boldine Ameliorates Vascular Oxidative Stress and Endothelial Dysfunction: Therapeutic Implication for Hypertension and Diabetes. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 2015, 65, 522–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behl, T.; Singh, S.; Sharma, N.; Zahoor, I.; Albarrati, A.; Albratty, M.; Meraya, A.M.; Najmi, A.; Bungau, S. Expatiating the Pharmacological and Nanotechnological Aspects of the Alkaloidal Drug Berberine: Current and Future Trends. Molecules 2022, 27, 3705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruijun, W.; Wenbin, M.; Yumin, W.; Ruijian, Z.; Puweizhong, H.; Yulin, L. Inhibition of Glioblastoma Cell Growth In Vitro and In Vivo by Brucine, a Component of Chinese Medicine. Oncol. Res. 2014, 22, 275–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.; Huang, R.; Wu, Y.; Jin, J.-M.; Chen, H.-Z.; Zhang, L.-J.; Luan, X. Brucine: A Review of Phytochemistry, Pharmacology, and Toxicology. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Sharma, M.; Dave, A.; Yang, Y.; Chen, Z.-S.; Radhakrishnan, R. The Antifibrotic and the Anticarcinogenic Activity of Capsaicin in Hot Chili Pepper in Relation to Oral Submucous Fibrosis. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 888280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Zhang, Y.; Fan, J.; Feng, Z.; Song, X. Pharmacological Activity of Capsaicin: Mechanisms and Controversies (Review). Mol. Med. Rep. 2024, 29, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yue, W.W.S.; Yuan, L.; Braz, J.M.; Basbaum, A.I.; Julius, D. TRPV1 Drugs Alter Core Body Temperature via Central Projections of Primary Afferent Sensory Neurons. Elife 2022, 11, e80139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kosina, P.; Walterová, D.; Ulrichová, J.; Lichnovský, V.; Stiborová, M.; Rýdlová, H.; Vicar, J.; Krecman, V.; Brabec, M.J.; Simánek, V. Sanguinarine and Chelerythrine: Assessment of Safety on Pigs in Ninety Days Feeding Experiment. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2004, 42, 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roque Bravo, R.; Faria, A.C.; Brito-da-Costa, A.M.; Carmo, H.; Mladěnka, P.; Dias da Silva, D.; Remião, F.; On Behalf of the Oemonom Researchers. Cocaine: An Updated Overview on Chemistry, Detection, Biokinetics, and Pharmacotoxicological Aspects Including Abuse Pattern. Toxins 2022, 14, 278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Liu, H.; Li, Y.; Zhao, D.; Wang, B.; Wang, H.; Wang, L.; Wang, K.; Yue, J.; Zhang, H.; et al. Melatonin Protects Against Cocaine-Induced Blood−Brain Barrier Dysfunction and Cognitive Impairment by Regulating miR-320a-Dependent GLUT1 Expression. J. Pineal Res. 2024, 76, e70002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipinski, R.J.; Hutson, P.R.; Hannam, P.W.; Nydza, R.J.; Washington, I.M.; Moore, R.W.; Girdaukas, G.G.; Peterson, R.E.; Bushman, W. Dose- and Route-Dependent Teratogenicity, Toxicity, and Pharmacokinetic Profiles of the Hedgehog Signaling Antagonist Cyclopamine in the Mouse. Toxicol. Sci. 2008, 104, 189–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.T.; Welch, K.D.; Panter, K.E.; Gardner, D.R.; Garrossian, M.; Chang, C.-W.T. Cyclopamine: From Cyclops Lambs to Cancer Treatment. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2014, 62, 7355–7362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Li, D.; Yu, S. Pharmacological Effects of Harmine and Its Derivatives: A Review. Arch. Pharm. Res. 2020, 43, 1259–1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ables, J.L.; Israel, L.; Wood, O.; Govindarajulu, U.; Fremont, R.T.; Banerjee, R.; Liu, H.; Cohen, J.; Wang, P.; Kumar, K.; et al. A Phase 1 Single Ascending Dose Study of Pure Oral Harmine in Healthy Volunteers. J. Psychopharmacol. 2024, 38, 911–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butts, C.A.; Hedderley, D.I.; Martell, S.; Dinnan, H.; Middlemiss-Kraak, S.; Bunn, B.J.; McGhie, T.K.; Lill, R.E. Influence of Oral Administration of Kukoamine A on Blood Pressure in a Rat Hypertension Model. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0267567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Q.; Luo, S.; Shi, Z.; Yu, M.; Guo, W.; Li, C. Nitidine Chloride, a Benzophenanthridine Alkaloid from Zanthoxylum Nitidum (Roxb.) DC., Exerts Multiple Beneficial Properties, Especially in Tumors and Inflammation-Related Diseases. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 1046402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daware, M.B.; Mujumdar, A.M.; Ghaskadbi, S. Reproductive Toxicity of Piperine in Swiss Albino Mice. Planta Med. 2000, 66, 231–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malini, T.; Manimaran, R.R.; Arunakaran, J.; Aruldhas, M.M.; Govindarajulu, P. Effects of Piperine on Testis of Albino Rats. J. Ethnopharmacol. 1999, 64, 219–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, X.; Yuan, Z.; Qu, B.; Zhou, H.; Liu, Z.; Xie, Y. Piperine Enhances the Bioavailability of Silybin via Inhibition of Efflux Transporters BCRP and MRP2. Phytomedicine 2019, 54, 98–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Z.-L.; Tay, V.; Guo, S.-Z.; Ren, J.; Shu, M.-G. Silibinin Induced Human Glioblastoma Cell Apoptosis Concomitant with Autophagy through Simultaneous Inhibition of mTOR and YAP. BioMed Res. Int. 2018, 2018, 6165192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Liu, X.; Li, W. Tetrandrine, a Chinese Plant-Derived Alkaloid, Is a Potential Candidate for Cancer Chemotherapy. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 40800–40815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schütz, R.; Müller, M.; Geisslinger, F.; Vollmar, A.; Bartel, K.; Bracher, F. Synthesis, Biological Evaluation and Toxicity of Novel Tetrandrine Analogues. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 207, 112810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP). Guideline on the Clinical Evaluation of Anticancer Medicinal Products; EMA/CHMP/205/95; European Medicines Agency: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023; pp. 1–43.

| Name of Anticancer Drug | Natural Alkaloid as Natural Matrices for Drug/Medicinal Plants | Mechanism of Action | Recommendations/Registered Clinical Trials | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Topotecan | Semi-synthetic derivative of camptothecin (quinoline alkaloid) extracted from the bark of the tree Camptotheca acuminata (Chinese tree) | Topoisomerase I inhibitors, apoptosis |

| [112] |

Chemical structure | C23H23N3O5 MW = 421.4 g/mol IUPAC name: (19S)-8-[(dimethylamino)methyl]-19-ethyl-7,19-dihydroxy-17-oxa-3,13-diazapentacyclo[11.8.0.02,11.04,9.015,20]henicosa-1(21),2,4(9),5,7,10,15(20)-heptaene-14,18-dione | |||

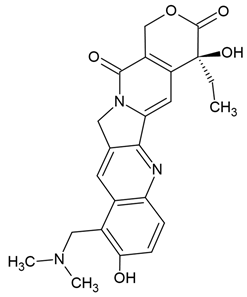

| Irinotecan | Semi-synthetic derivative of camptothecin (quinoline alkaloid) extracted from the bark of the tree Camptotheca acuminata (Chinese tree) | Topoisomerase I inhibitors |

| [109,111,113] |

Chemical structure | C33H38N4O6 MW = 586.7 g/mol IUPAC name: [(19S)-10,19-diethyl-19-hydroxy-14,18-dioxo-17-oxa-3,13-diazapentacyclo[11.8.0.02,11.04,9.015,20]henicosa-1(21),2,4(9),5,7,10,15(20)-heptaen-7-yl] 4-piperidin-1-ylpiperidine-1-carboxylate | |||

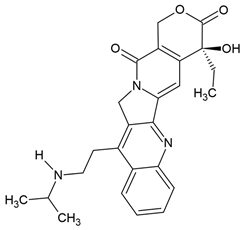

| Belotecan | Semi-synthetic derivative of camptothecin (quinoline alkaloid) extracted from the bark of the tree Camptotheca acuminata (Chinese tree) | Topoisomerase I inhibitors |

| [110] |

Chemical structure | C25H27N3O4 MW = 433.5 g/mol IUPAC name: (19S)-19-ethyl-19-hydroxy-10-[2-(propan-2-ylamino)ethyl]-17-oxa-3,13-diazapentacyclo[11.8.0.02,11.04,9.015,20]henicosa-1(21),2,4,6,8,10,15(20)-heptaene-14,18-dione | |||

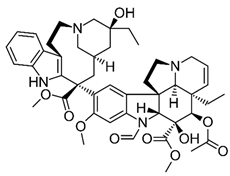

| Vincristine | Natural alkaloid from the Madagascar periwinkle Catharanthus roseus |

|

| [107] |

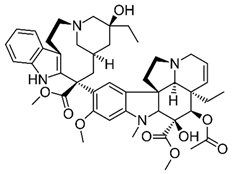

Chemical structure | C46H56N4O10 MW = 825.0 g/mol IUPAC name: methyl (1R,9R,10S,11R,12R,19R)-11-acetyloxy-12-ethyl-4-[(13S,15S,17S)-17-ethyl-17-hydroxy-13-methoxycarbonyl-1,11-diazatetracyclo[13.3.1.04,12.05,10]nonadeca-4(12),5,7,9-tetraen-13-yl]-8-formyl-10-hydroxy-5-methoxy-8,16-diazapentacyclo[10.6.1.01,9.02,7.016,19]nonadeca-2,4,6,13-tetraene-10-carboxylate | |||

| Vinblastine | Natural alkaloid from the Madagascar periwinkle Catharanthus roseu |

|

| [91,92,93,107] |

Chemical structure | C46H58N4O9 MW = 811.0 g/mol IUPAC name: methyl (1R,9R,10S,11R,12R,19R)-11-acetyloxy-12-ethyl-4-[(13S,15R,17S)-17-ethyl-17-hydroxy-13-methoxycarbonyl-1,11-diazatetracyclo[13.3.1.04,12.05,10]nonadeca-4(12),5,7,9-tetraen-13-yl]-10-hydroxy-5-methoxy-8-methyl-8,16-diazapentacyclo[10.6.1.01,9.02,7.016,19]nonadeca-2,4,6,13-tetraene-10-carboxylate | |||

| Vindesine | Semi-synthetic derivatives of vinblastine extracted from Catharanthus roseus |

|

| [107] |

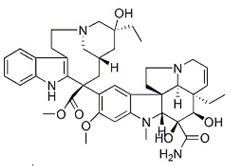

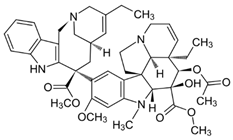

Chemical structure | C43H55N5O7 MW = 753.9 g/mol IUPAC name: methyl (13S,15S,17S)-13-[(1R,9R,10S,11R,12R,19R)-10-carbamoyl-12-ethyl-10,11-dihydroxy-5-methoxy-8-methyl-8,16-diazapentacyclo[10.6.1.01,9.02,7.016,19]nonadeca-2,4,6,13-tetraen-4-yl]-17-ethyl-17-hydroxy-1,11-diazatetracyclo[13.3.1.04,12.05,10]nonadeca-4(12),5,7,9-tetraene-13-carboxylate | |||

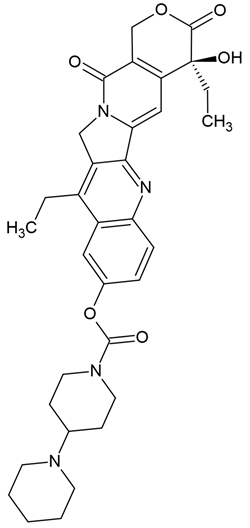

| Vinorelbine | Semi-synthetic derivatives of vinblastine extracted from Catharanthus roseus |

|

| [107] |

Chemical structure | C45H54N4O8 MW = 778.9 g/mol IUPAC name: methyl (1R,9R,10S,11R,12R,19R)-11-acetyloxy-12-ethyl-4-[(12S,14R)-16-ethyl-12-methoxycarbonyl-1,10-diazatetracyclo[12.3.1.03,11.04,9]octadeca-3(11),4,6,8,15-pentaen-12-yl]-10-hydroxy-5-methoxy-8-methyl-8,16-diazapentacyclo[10.6.1.01,9.02,7.016,19]nonadeca-2,4,6,13-tetraene-10-carboxylate | |||

| Homoharringtonine | Cephalotaxus fortunei |

|

| [111] |

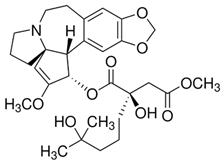

| [102] | |||

Chemical structure | C29H39NO9 MW = 545.6 g/mol IUPAC name: 1-O-[(2S,3S,6R)-4-methoxy-16,18-dioxa-10-azapentacyclo[11.7.0.02,6.06,10.015,19]icosa-1(20),4,13,15(19)-tetraen-3-yl] 4-O-methyl (2R)-2-hydroxy-2-(4-hydroxy-4-methylpentyl)butanedioate | |||

| Alkaloids | Efficiency Expressed by Values of the IC50 (Cancer Cell Viability—Cytotoxicity) | Safety Profile | Perspectives for Anti-Glioblastoma Therapies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Berberin | IC50 = from 21.76 μmol/L to 42 μmol/L (U87), IC50 = from 9.79 µmol/L to 32 μmol/L (U251) [60], IC50 = 35.54 µmol/L (U118) [47] |

| |

| Boldine | IC50 = 68.6 μM (GBM59), IC50 = 213.8 μM (for U87-MG), IC50 = 141.7 μM (GBM96) [28] |

|

|

| Brucine | IC50 = from 50 to 800 µmol/L (U251, U87, U118, A172) |

| |

| Capsaicin | IC50 = from 265.7 μM to 325.7 μM (LN18) [69] |

| |

| Chelerythrine | IC50 = from 8 μM to 15 μM (U87, C6) [39] |

| |

| Cocaine | IC50 = 6.76 mM (C6) [88] |

|

|

| Colchicine | IC50 = 10 nM (U87MG), IC50= 50 nM (U373MG) [84] |

| |

| Cyclopamine | IC50 = 11.4 μM (C6), IC50 = 7.7 μM (C6-GSCs) [82] |

| |