Exploring Dacarbazine Complexation with a Cellobiose-Based Carrier: A Multimethod Theoretical, NMR, and Thermochemical Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

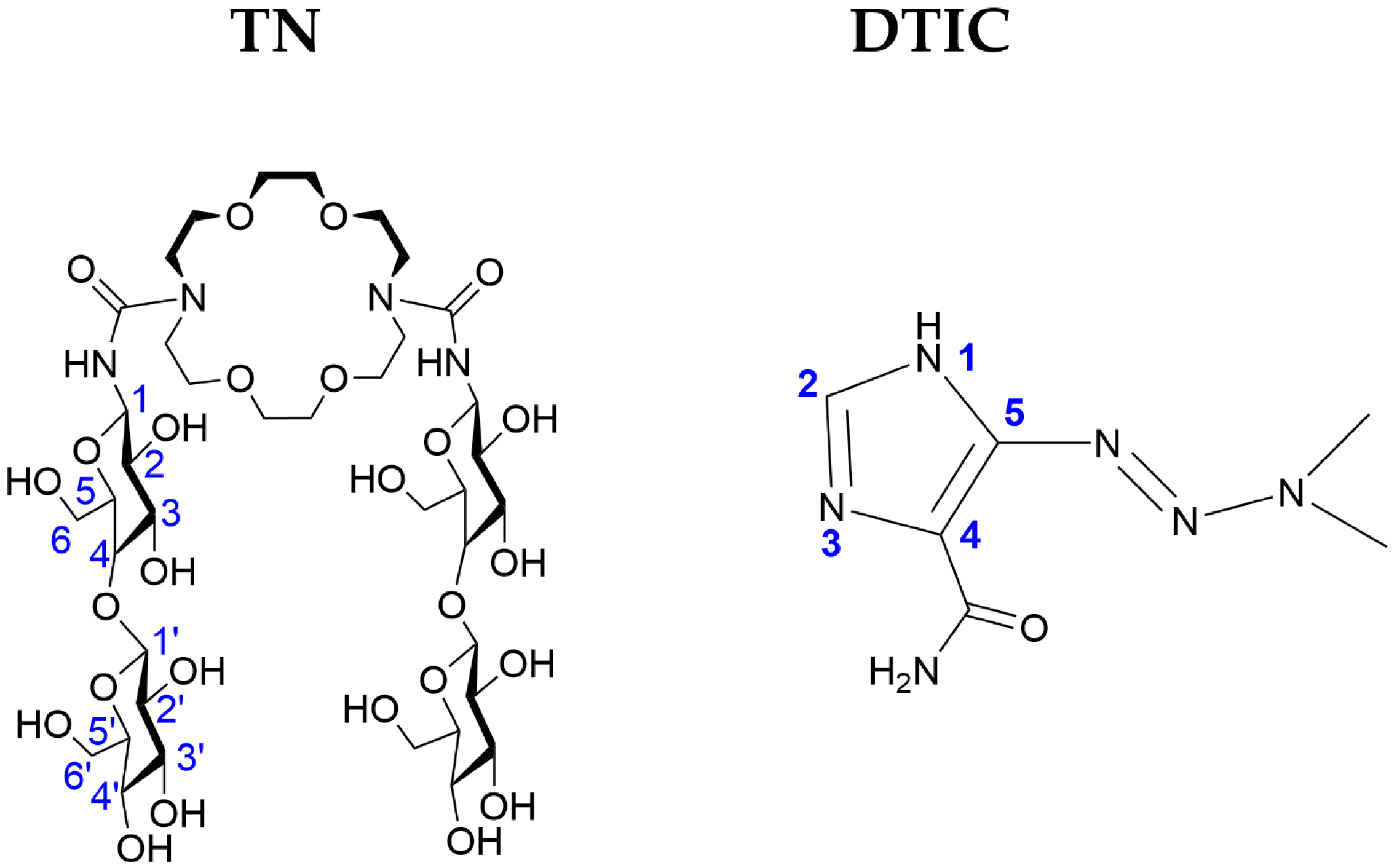

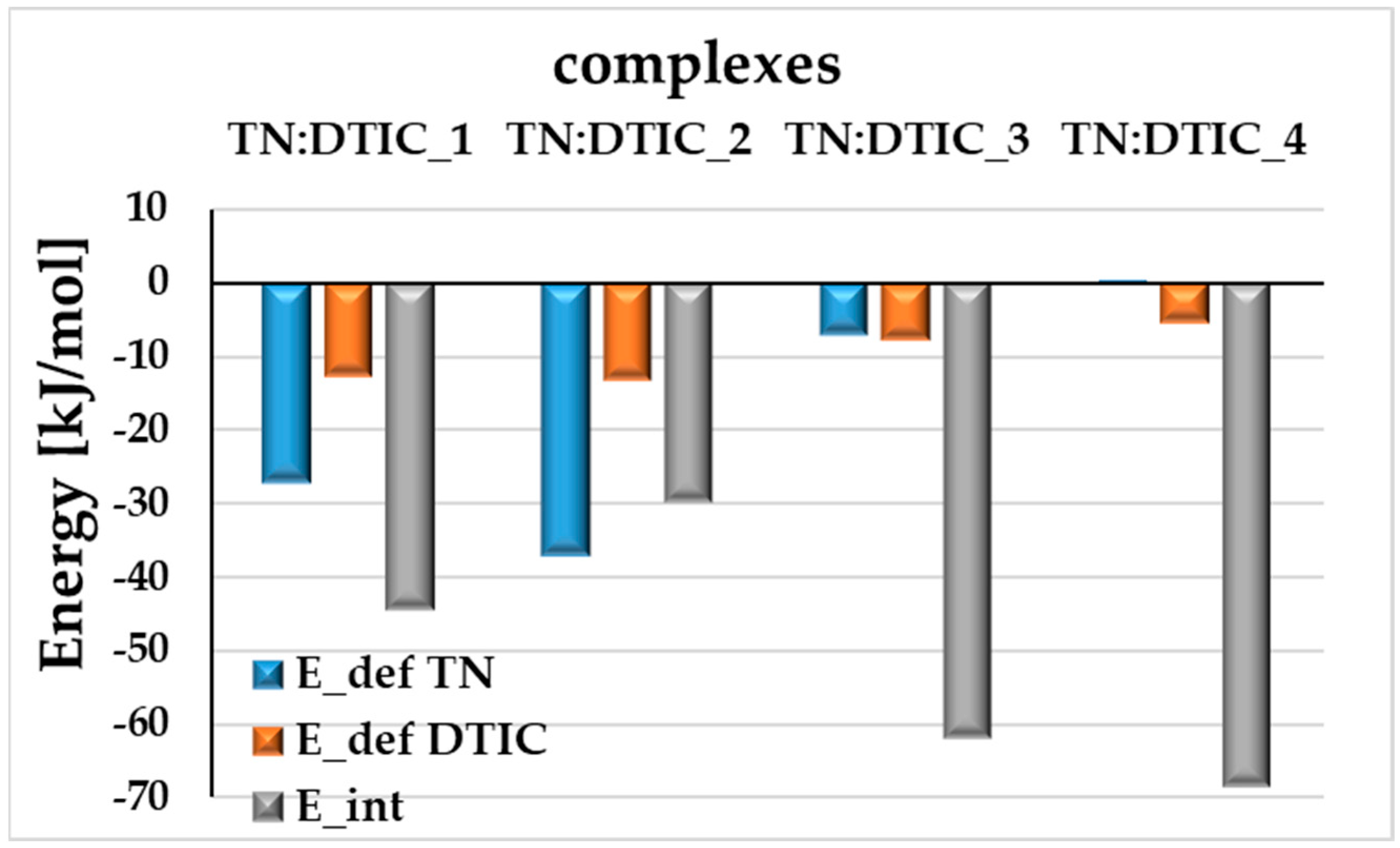

2.1. Analysis of Structural and Energetic Properties of the TN:DTIC Complex-Theoretical Study

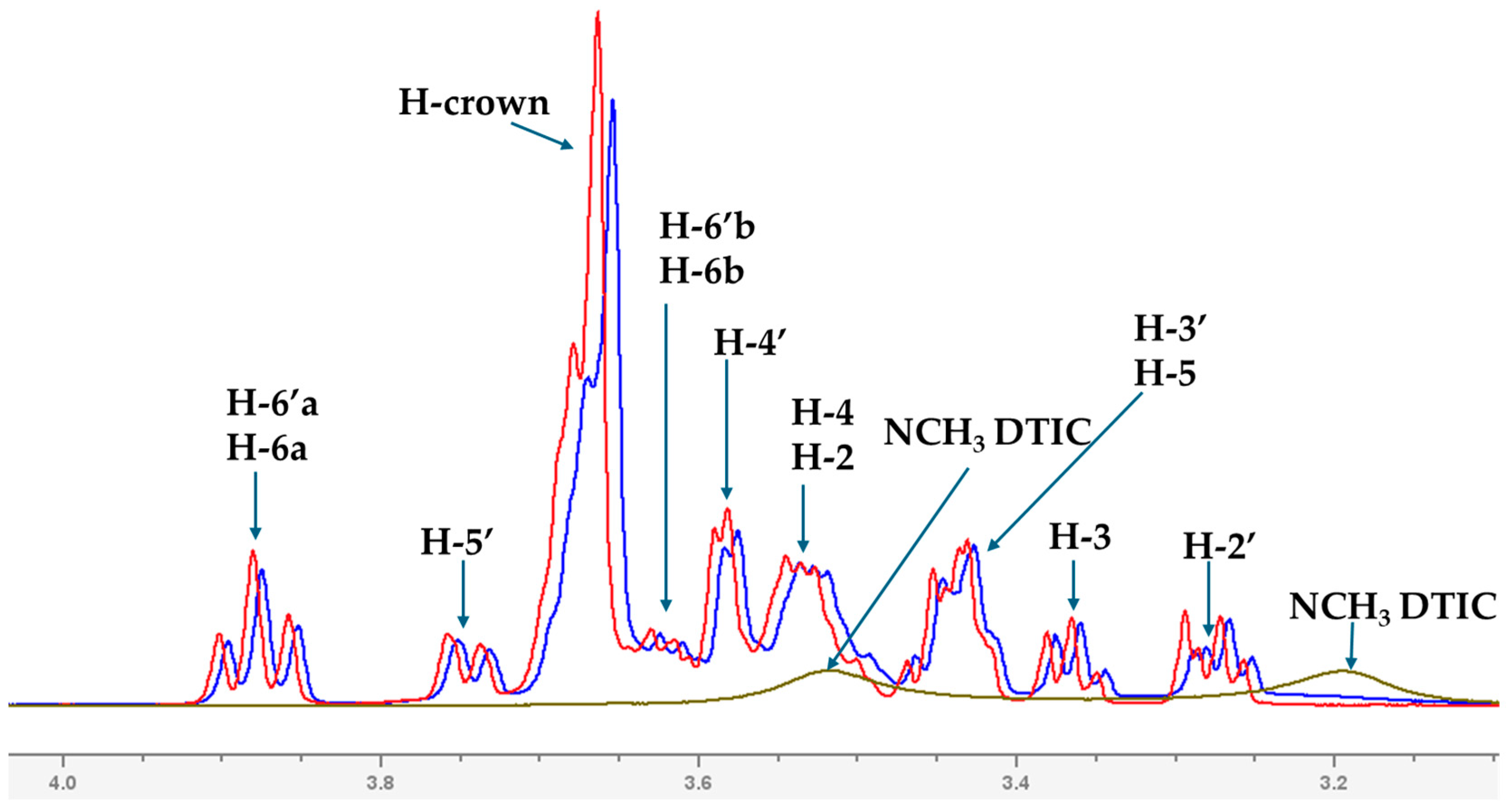

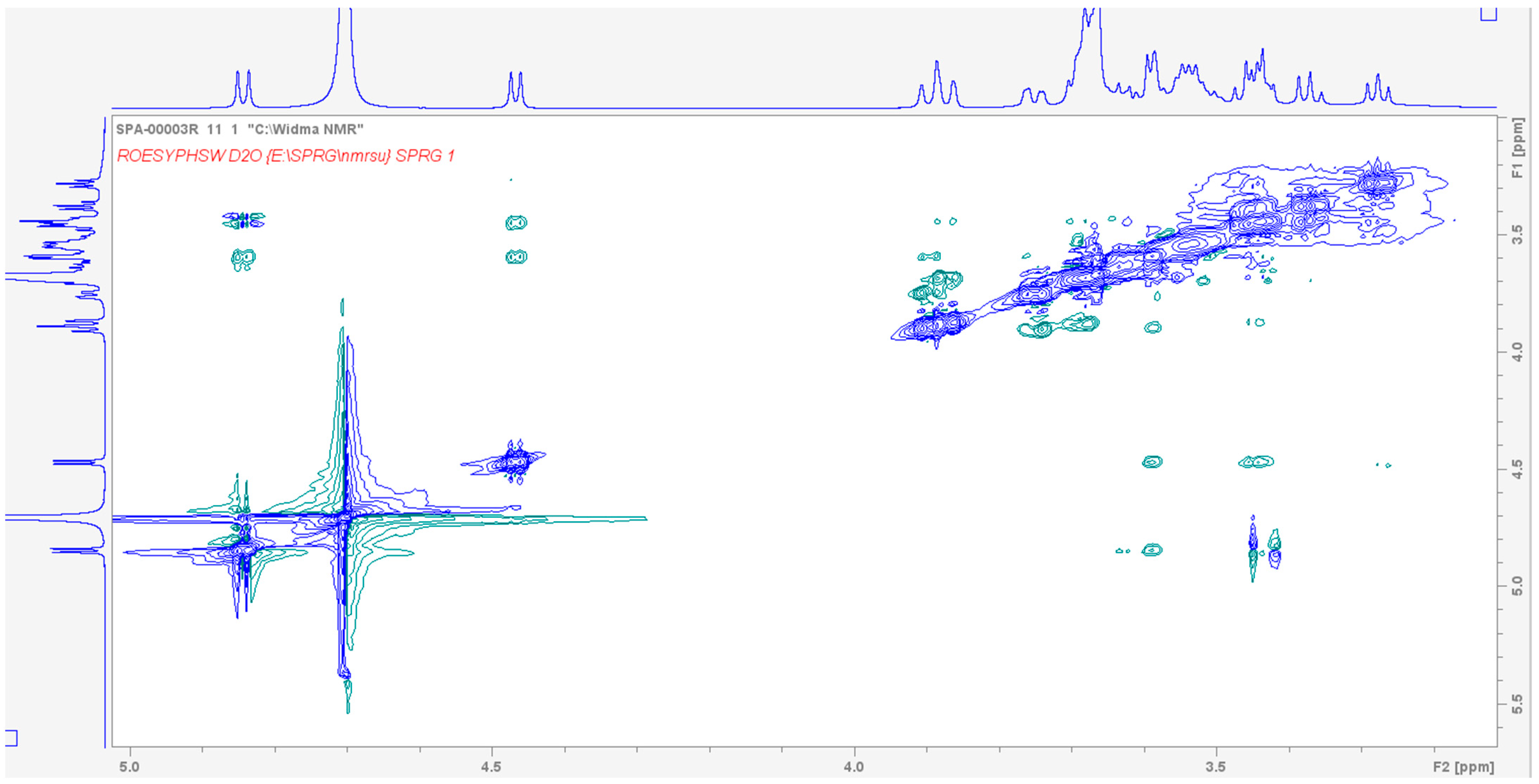

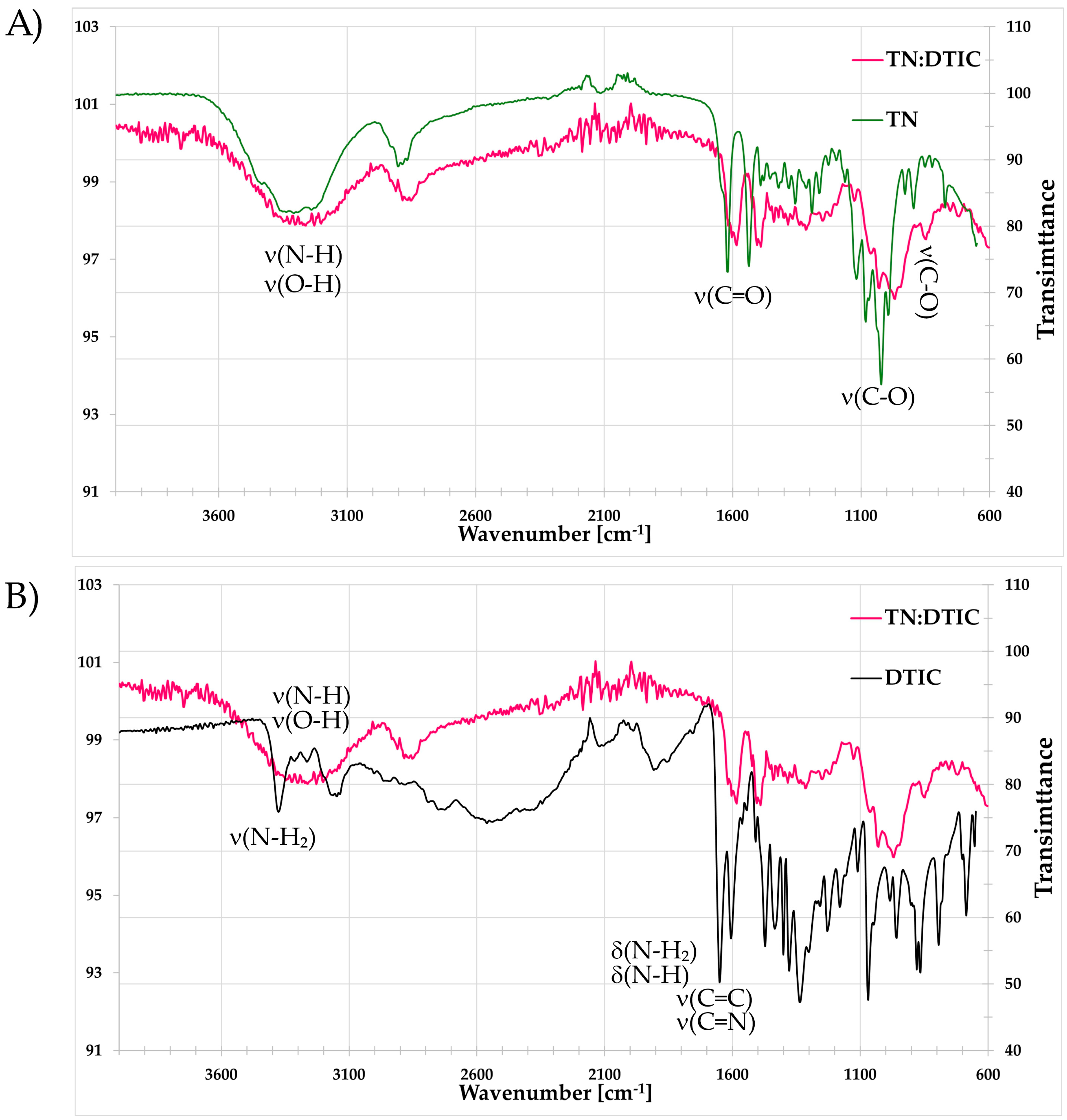

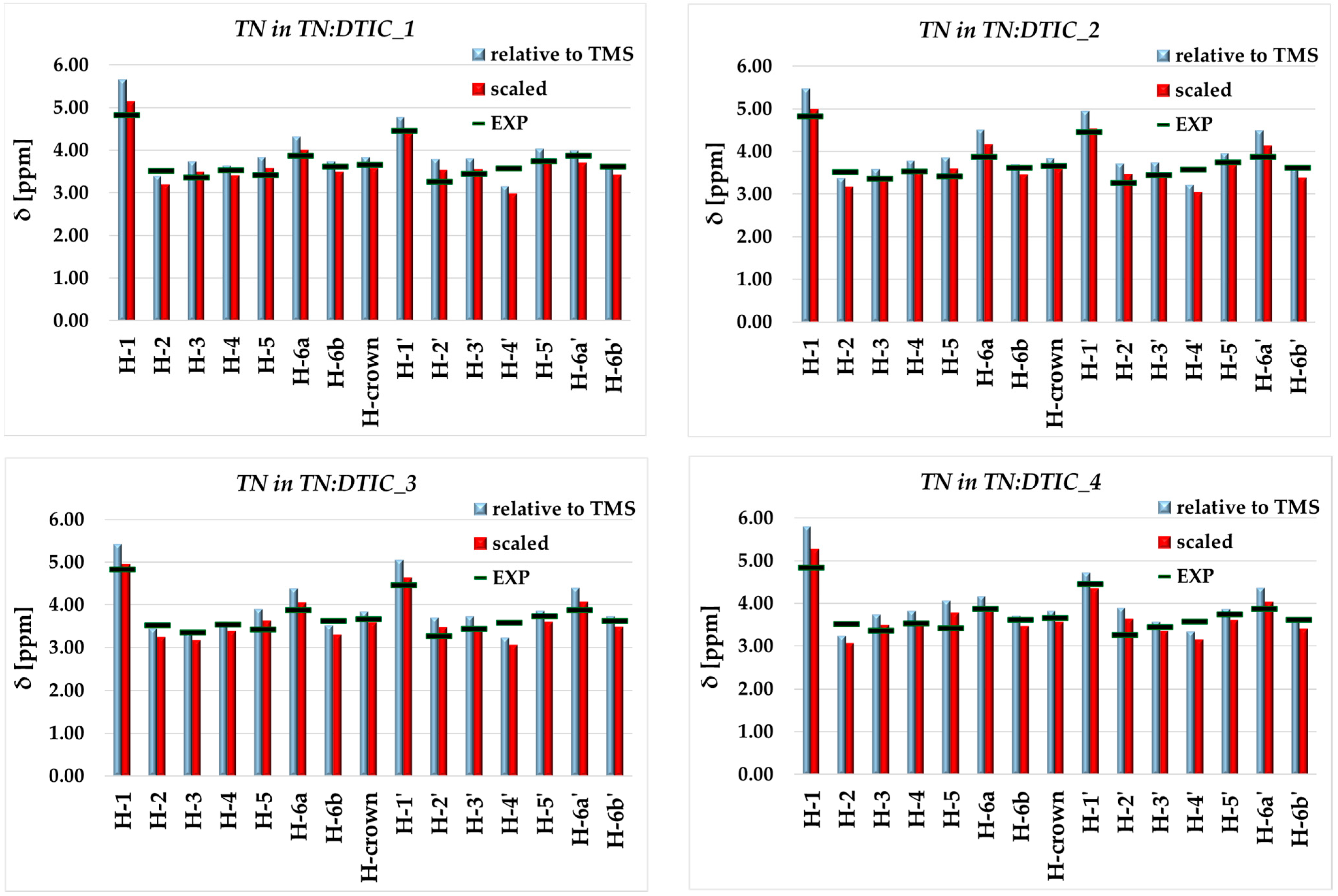

2.2. Analysis of Spectroscopic Properties of Complex-Comparison Between Theoretical and Experimental Results

2.3. Thermodynamic Analysis of the Complex

- —equilibrium concentration of free TN;

- —concentration of dacarbazine in solution;

- —observed molar conductivity of the solution in the presence of TN;

- —molar conductivity of the pure dacarbazine solution before TN addition;

- —molar conductivity of the solution containing the TN:DTIC complex;

- —molar conductivity of the complexed ion;

- —formation constant of the TN:DTIC complex.

- —number of experimental points;

- —experimentally determined molar conductivity;

- —conductivity value calculated from Equation (5).

- —limiting molar conductivity at infinite dilution;

- —empirical parameters obtained from data fitting;

- —concentration of dacarbazine;

- —concentration of the supporting electrolyte (background salt) used to correct for ionic strength effects.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Computational Analysis

- —is the energy of the optimized complex;

- and —are the energies of TN and DTIC, respectively, in their most stable geometries.

3.2. Synthesis of TN:DTIC Complex

3.3. Thermochemistry Analysis

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Al-Otaibi, J.S.; Mary, Y.S.; Mary, Y.S.; Ullah, Z.; Yadav, R.; Gupta, N.; Churchill, D.G. Adsorption Properties of Dacarbazine with Graphene/Fullerene/Metal Nanocages—Reactivity, Spectroscopic and SERS Analysis. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2022, 268, 120677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hersh, E.M.; Del Vecchio, M.; Brown, M.P.; Kefford, R.; Loquai, C.; Testori, A.; Bhatia, S.; Gutzmer, R.; Conry, R.; Haydon, A.; et al. A Randomized, Controlled Phase III Trial of Nab-Paclitaxel versus Dacarbazine in Chemotherapy-Naïve Patients with Metastatic Melanoma. Ann. Oncol. 2015, 26, 2267–2274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oh, C.S.; Sher, E.F.; Bieber, A.K. Melanoma in Pregnancy. Semin. Perinatol. 2025, 49, 152040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Józwiak-Hagymásy, J.; Széles, Á.; Dóczi, T.; Németh, B.; Mezei, D.; Varga, H.; Gronchi, A.; van Houdt, W.J.; Tordai, A.; Csanádi, M. Economic Evaluations and Health Economic Models of Soft Tissue Sarcomas: Systematic Literature Review from a European and North American Perspective. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2025, 209, 104661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourahmad, J.; Amirmostofian, M.; Kobarfard, F.; Shahraki, J. Biological Reactive Intermediates That Mediate Dacarbazine Cytotoxicity. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2009, 65, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Han, X. Co-Delivery of Dacarbazine and All-Trans Retinoic Acid (ATRA) Using Lipid Nanoformulations for Synergistic Antitumor Efficacy Against Malignant Melanoma. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2020, 15, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rihackova, E.; Rihacek, M.; Vyskocilova, M.; Valik, D.; Elbl, L. Revisiting Treatment-Related Cardiotoxicity in Patients with Malignant Lymphoma—A Review and Prospects for the Future. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2023, 10, 1243531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamazaki, N.; Uhara, H.; Fukushima, S.; Uchi, H.; Shibagaki, N.; Kiyohara, Y.; Tsutsumida, A.; Namikawa, K.; Okuyama, R.; Otsuka, Y.; et al. Phase II Study of the Immune-Checkpoint Inhibitor Ipilimumab plus Dacarbazine in Japanese Patients with Previously Untreated, Unresectable or Metastatic Melanoma. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2015, 76, 969–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira-Silva, J.M.; Oliveira, L.S.; Chiminazo, C.B.; Fonseca, R.; de Souza, C.V.E.; Aissa, A.F.; de Almeida Lima, G.D.; Ionta, M.; Castro-Gamero, A.M. WT161, a Selective HDAC6 Inhibitor, Decreases Growth, Enhances Chemosensitivity, Promotes Apoptosis, and Suppresses Motility of Melanoma Cells. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2025, 95, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berclaz, L.M.; Di Gioia, D.; Jurinovic, V.; Völkl, M.; Güler, S.E.; Albertsmeier, M.; Klein, A.; Dürr, H.R.; Mansoorian, S.; Knösel, T.; et al. LDH and Hemoglobin Outperform Systemic Inflammatory Indices as Prognostic Factors in Patients with Soft Tissue Sarcoma Undergoing Neoadjuvant Treatment. BMC Cancer 2025, 25, 496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, L.; Ma, J.; Zhou, Y.; Ying, X.; Liang, G.; Pi, G.; Li, Y.; Luo, Y.; Bi, J.; He, H.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of Ondansetron Orally Soluble Pellicle for Preventing Moderate- to High-Emetic Risk Chemotherapy-Induced Nausea and Vomiting. BMC Cancer 2025, 25, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, T.; He, X.; Wang, J.; Liu, J.; Hu, X.; Bai, C.; Yin, S.; Shi, Y.; Wang, Y.; Tan, Z.; et al. Self-Assembled Patient-Derived Tumor-like Cell Clusters for Personalized Drug Testing in Diverse Sarcomas. Cell Rep. Med. 2025, 6, 101990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Huang, J.; Zheng, X.; Huang, P.; Yang, X. Cost-Effectiveness Analysis of Eribulin versus Dacarbazine in Patients with Advanced Liposarcoma. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 2084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diniz, L.F.; Carvalho, P.S.; Souza, M.A.C.; Diniz, R.; Fernandes, C. Highly Soluble Dacarbazine Multicomponent Crystals Less Prone to Photodegradation. Mol. Pharm. 2024, 21, 3661–3673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, W.; Zou, Y.; Li, J.; Jiang, H.; Li, J.; Wu, J.; Zhu, S.; Ding, Y.; Xu, H.; Jia, F.; et al. Synergistic Therapy of Melanoma by Co-Delivery of Dacarbazine and Ferroptosis-Inducing Ursolic Acid Using Biomimetic Nanoparticles. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 41532–41543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, S.; Sharma, S. Dacarbazine-Encapsulated Solid Lipid Nanoparticles for Skin Cancer: Physical Characterization, Stability, in-Vivo Activity, Histopathology, and Immunohistochemistry. Front. Oncol. 2023, 13, 1102269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vankudre, S.; Shirkoli, N.; Hawaldar, R.; Shetti, H. Enhanced Delivery of Dacarbazine Using Nanosponge Loaded Hydrogel for Targeted Melanoma Treatment: Formulation, Statistical Optimization and Pre-Clinical Evaluation. J. Pharm. Innov. 2025, 20, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, B.; Li, M.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, X.; Gao, H.; Gao, J.; Shen, C.; Zhou, Y.; Li, F.; Liu, A. Co-Delivery of Dacarbazine and MiRNA 34a Combinations to Synergistically Improve Malignant Melanoma Treatments. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 2025, 19, 553–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahmoud, A.H.H.; Mohamed, L.A.; Sidhom, P.A.; Al-Fahemi, J.H.; Ibrahim, M.A.A. A DFT Investigation of Beryllium Oxide (Be12O12) as a Nanocarrier for Dacarbazine Anticancer Drug. Polyhedron 2025, 279, 117657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.-Y.; Al-Yasiri, S.A.M.; Shather, A.H.; Jalil, A.; Al-Athari, A.J.H.; Mahmoud, Z.H.; Hadrawi, S.K.; Kadhim, M.M. The Capability of Pure and Modified Boron Carbide Nanosheet as a Nanocarrier for Dacarbazine Anticancer Drug Delivery: DFT Study. Pramana 2024, 98, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintana-Contardo, S.; Donoso-González, O.; Lang, E.; Guerrero, A.R.; Noyong, M.; Simon, U.; Kogan, M.J.; Yutronic, N.; Sierpe, R. Optimizing Dacarbazine Therapy: Design of a Laser-Triggered Delivery System Based on β-Cyclodextrin and Plasmonic Gold Nanoparticles. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mishra, H.; Mishra, P.K.; Iqbal, Z.; Jaggi, M.; Madaan, A.; Bhuyan, K.; Gupta, N.; Gupta, N.; Vats, K.; Verma, R.; et al. Co-Delivery of Eugenol and Dacarbazine by Hyaluronic Acid-Coated Liposomes for Targeted Inhibition of Survivin in Treatment of Resistant Metastatic Melanoma. Pharmaceutics 2019, 11, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiong, W.; Guo, Z.; Zeng, B.; Wang, T.; Zeng, X.; Cao, W.; Lian, D. Dacarbazine-Loaded Targeted Polymeric Nanoparticles for Enhancing Malignant Melanoma Therapy. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2022, 10, 847901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoelm, M.; Kinart, Z.; Porwański, S. Theoretical and Preliminary Experimental Investigations on the Interactions between Sugar Cryptand and Treosulfan. Sci. Rep. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoelm, M.; Porwański, S.; Jóźwiak, P.; Krześlak, A. Combined Theoretical and Experimental Investigations: Design, Synthesis, Characterization, and In Vitro Cytotoxic Activity Assessment of a Complex of a Novel Ureacellobiose Drug Carrier with the Anticancer Drug Carmustine. Molecules 2024, 29, 3359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoelm, M.; Porwański, S.; Jóźwiak, P.; Krześlak, A. Theoretical Analysis, Synthesis and Biological Activity against Normal and Cancer Cells of a Complex Formed by a Novel Sugar Cryptand and Anticancer Drug Mitomycin C. Carbohydr. Res. 2025, 551, 109425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kinart, Z.; Hoelm, M.; Imińska, M. Evaluating Theoretical Solvent Models for Thermodynamic and Structural Descriptions of Dacarbazine–Cyclodextrin Complexes. The Theoretical and Conductometric Study. Molecules 2025, 30, 2309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Shugulí, C.; Vidal, C.P.; Cantero-López, P.; Lopez-Polo, J. Encapsulation of Plant Extract Compounds Using Cyclodextrin Inclusion Complexes, Liposomes, Electrospinning and Their Combinations for Food Purposes. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 108, 177–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isare, B.; Linares, M.; Lazzaroni, R.; Bouteiller, L. Engineering the Cavity of Self-Assembled Dynamic Nanotubes. J. Phys. Chem. B 2009, 113, 3360–3364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, A.J. An Introduction to Hydrogen Bonding; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Pocrnić, M.; Hoelm, M.; Ignaczak, A.; Čikoš, A.; Budimir, A.; Tomišić, V.; Galić, N. Inclusion Complexes of Loratadine with β-Cyclodextrin and Its Derivatives in Solution. Integrated Spectroscopic, Thermodynamic and Computational Studies. J. Mol. Liq. 2024, 410, 125515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tantillo, D.J. Chemical Shift Repository. Available online: http://cheshirenmr.info/instructions.htm (accessed on 16 December 2025).

- Kinart, Z.; Tomaš, R. Studies of the Formation of Inclusion Complexes Derivatives of Cinnamon Acid with α-Cyclodextrin in a Wide Range of Temperatures Using Conductometric Methods. Molecules 2022, 27, 4420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salomon, M. Conductometric Study of Cationic and Anionic Complexes in Propylene Carbonate. J. Solut. Chem. 1990, 19, 1225–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salomon, M.; Hefter, G.T. Mobilities of Cation-Macrocyclic Ligand Complexes. Pure Appl. Chem. 1993, 65, 1533–1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neese, F. Software Update: The ORCA Program System—Version 6.0. WIREs Comput. Mol. Sci. 2025, 15, e70019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bannwarth, C.; Ehlert, S.; Grimme, S. GFN2-XTB—An Accurate and Broadly Parametrized Self-Consistent Tight-Binding Quantum Chemical Method with Multipole Electrostatics and Density-Dependent Dispersion Contributions. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2019, 15, 1652–1671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hypercube, Inc. HyperChem (TM), Professional 8.0; Hypercube, Inc.: Gainesville, FL, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart, J.J.P. Optimization of Parameters for Semiempirical Methods VI: More Modifications to the NDDO Approximations and Re-Optimization of Parameters. J. Mol. Model. 2013, 19, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, J.P. Stewart MOPAC2016; Stewart Computational Chemistry: Colorado Springs, CO, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y.; Truhlar, D.G. Exploring the Limit of Accuracy of the Global Hybrid Meta Density Functional for Main-Group Thermochemistry, Kinetics, and Noncovalent Interactions. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2008, 4, 1849–1868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimme, S.; Antony, J.; Ehrlich, S.; Krieg, H. A Consistent and Accurate Ab Initio Parametrization of Density Functional Dispersion Correction (DFT-D) for the 94 Elements H-Pu. J. Chem. Phys. 2010, 132, 154104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rassolov, V.A.; Ratner, M.A.; Pople, J.A.; Redfern, P.C.; Curtiss, L.A. 6-31G* Basis Set for Third-row Atoms. J. Comput. Chem. 2001, 22, 976–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frisch, M.J.; Trucks, G.W.; Schlegel, H.B.; Scuseria, G.E.; Robb, M.A.; Cheeseman, J.R.; Scalmani, G.; Barone, V.; Petersson, G.A.; Nakatsuji, H.; et al. Gaussian 16, Revision C.01 2016; Gaussian, Inc.: Wallingford, CT, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Boys, S.F.; Bernardi, F. The Calculation of Small Molecular Interactions by the Differences of Separate Total Energies. Some Procedures with Reduced Errors. Mol. Phys. 1970, 19, 553–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheeseman, J.R.; Trucks, G.W.; Keith, T.A.; Frisch, M.J. A Comparison of Models for Calculating Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Shielding Tensors. J. Chem. Phys. 1996, 104, 5497–5509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porwanski, S.; Dumarcay-Charbonnier, F.; Menuel, S.; Joly, J.-P.; Bulach, V.; Marsura, A. Bis-β-Cyclodextrinyl- and Bis-Cellobiosyl-Diazacrowns: Synthesis and Molecular Complexation Behaviors toward Busulfan Anticancer Agent and Two Basic Aminoacids. Tetrahedron 2009, 65, 6196–6203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bešter-Rogač, M.; Habe, D. Modern Advances in Electrical Conductivity Measurements of Solutions. Acta Chim. Slov. 2006, 53, 391–395. [Google Scholar]

- Bešter-Rogač, M.; Hunger, J.; Stoppa, A.; Buchner, R. 1-Ethyl-3-Methylimidazolium Ethylsulfate in Water, Acetonitrile, and Dichloromethane: Molar Conductivities and Association Constants. J. Chem. Eng. Data 2011, 56, 1261–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bald, A.; Kinart, Z. Conductance Studies of NaCl, KCl, NaBr, KBr, NaI, Bu4NI, and NaBPh4 in Water + 2-Propoxyethanol Mixtures at 298.15 K. Ionics 2015, 21, 2781–2787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinart, Z. Conductance Studies of Sodium Salts of Some Aliphatic Carboxylic Acids in Water at Different Temperatures. J. Mol. Liq. 2017, 248, 1059–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boruń, A.; Bald, A. Ionic Association and Conductance of Ionic Liquids in Dichloromethane at Temperatures from 278.15 to 303.15 K. Ionics 2016, 22, 859–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| T/K | ΛTN(DTIC) [S∙cm2/mol−1] | Kf/dm3·mol−1 | σ(Λ) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 293.15 | 40.52 ± 0.01 | 11,526.9 ± 2 | 0.02 |

| 298.15 | 44.85 ± 0.01 | 8657.4 ± 2 | 0.01 |

| 303.15 | 47.90 ± 0.02 | 6717.8 ± 3 | 0.01 |

| 308.15 | 50.75 ± 0.01 | 5287.4 ± 2 | 0.01 |

| 313.15 | 53.30 ± 0.01 | 4293.3 ± 2 | 0.02 |

| T/K | ΔH0/kJ·mol−1 | ΔG0/kJ·mol−1 | ΔS0/kJ·mol−1·K−1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 293.15 | −42.55 | −22.79 | −0.0674 |

| 298.15 | −40.07 | −22.47 | −0.0590 |

| 303.15 | −37.57 | −22.21 | −0.0507 |

| 308.15 | −35.00 | −21.96 | −0.0423 |

| 313.15 | −32.41 | −21.78 | −0.0340 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hoelm, M.; Kinart, Z.; Porwański, S. Exploring Dacarbazine Complexation with a Cellobiose-Based Carrier: A Multimethod Theoretical, NMR, and Thermochemical Study. Molecules 2025, 30, 4819. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244819

Hoelm M, Kinart Z, Porwański S. Exploring Dacarbazine Complexation with a Cellobiose-Based Carrier: A Multimethod Theoretical, NMR, and Thermochemical Study. Molecules. 2025; 30(24):4819. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244819

Chicago/Turabian StyleHoelm, Marta, Zdzisław Kinart, and Stanisław Porwański. 2025. "Exploring Dacarbazine Complexation with a Cellobiose-Based Carrier: A Multimethod Theoretical, NMR, and Thermochemical Study" Molecules 30, no. 24: 4819. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244819

APA StyleHoelm, M., Kinart, Z., & Porwański, S. (2025). Exploring Dacarbazine Complexation with a Cellobiose-Based Carrier: A Multimethod Theoretical, NMR, and Thermochemical Study. Molecules, 30(24), 4819. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244819