Feasibility Analysis of Tetracycline Degradation in Water by O3/PMS/FeMoBC Process

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Reagents

2.2. Analysis and Detection Methods

2.3. Overview of Characterization Results of FeMoBC Materials

3. Results

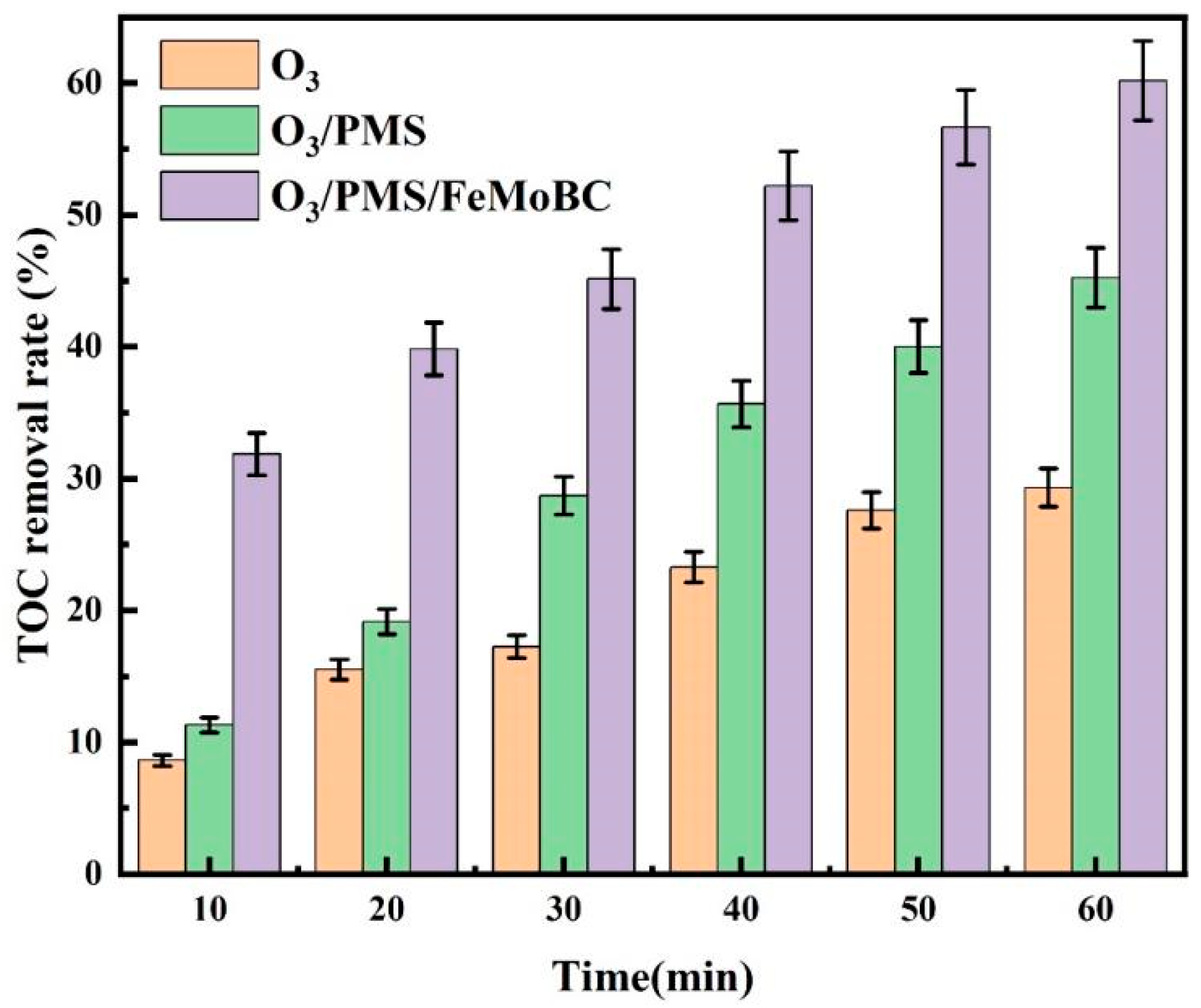

3.1. TOC Removal Rate of TC Degraded by O3, O3/PMS and O3/PMS/FeMoBC Processes

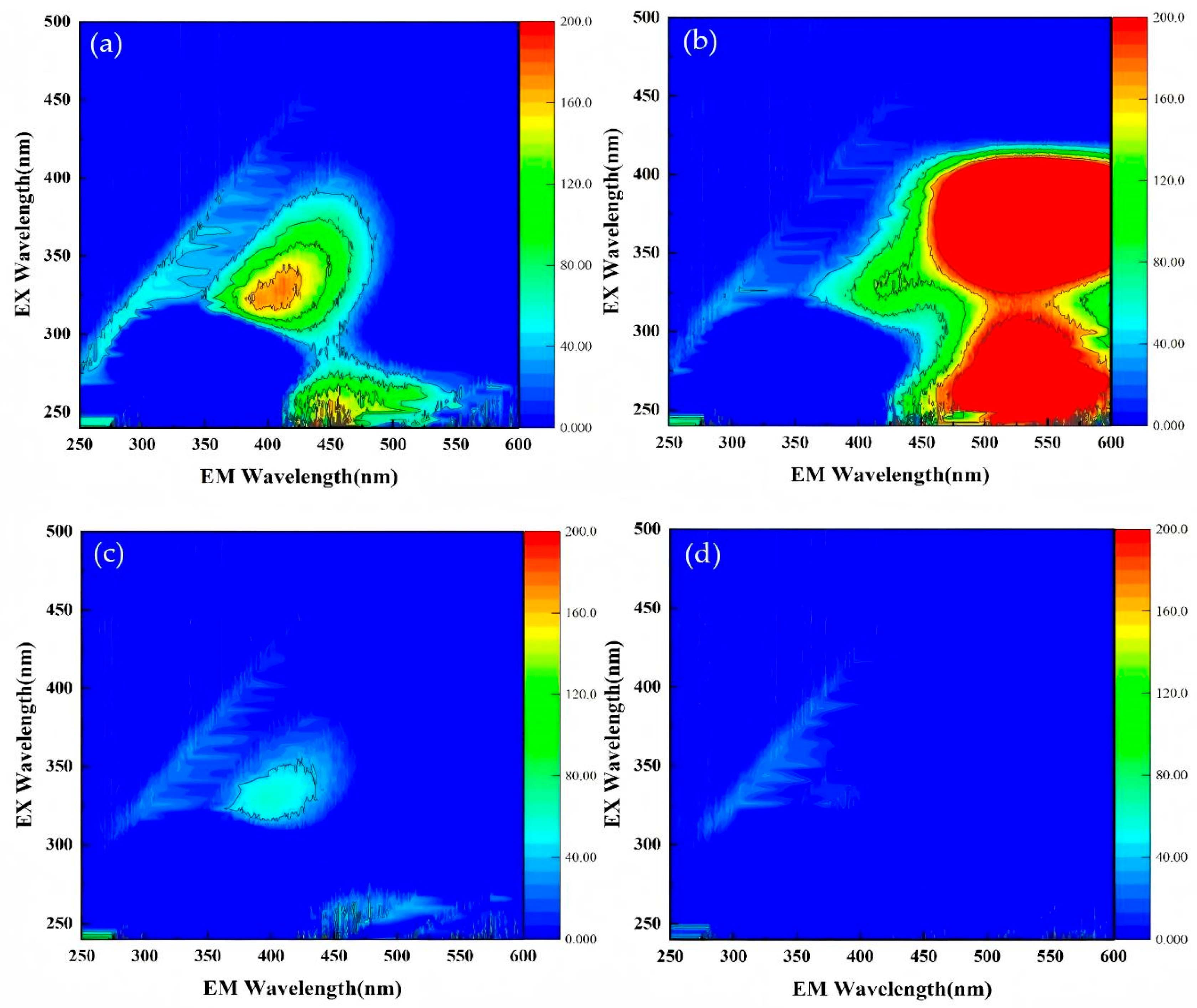

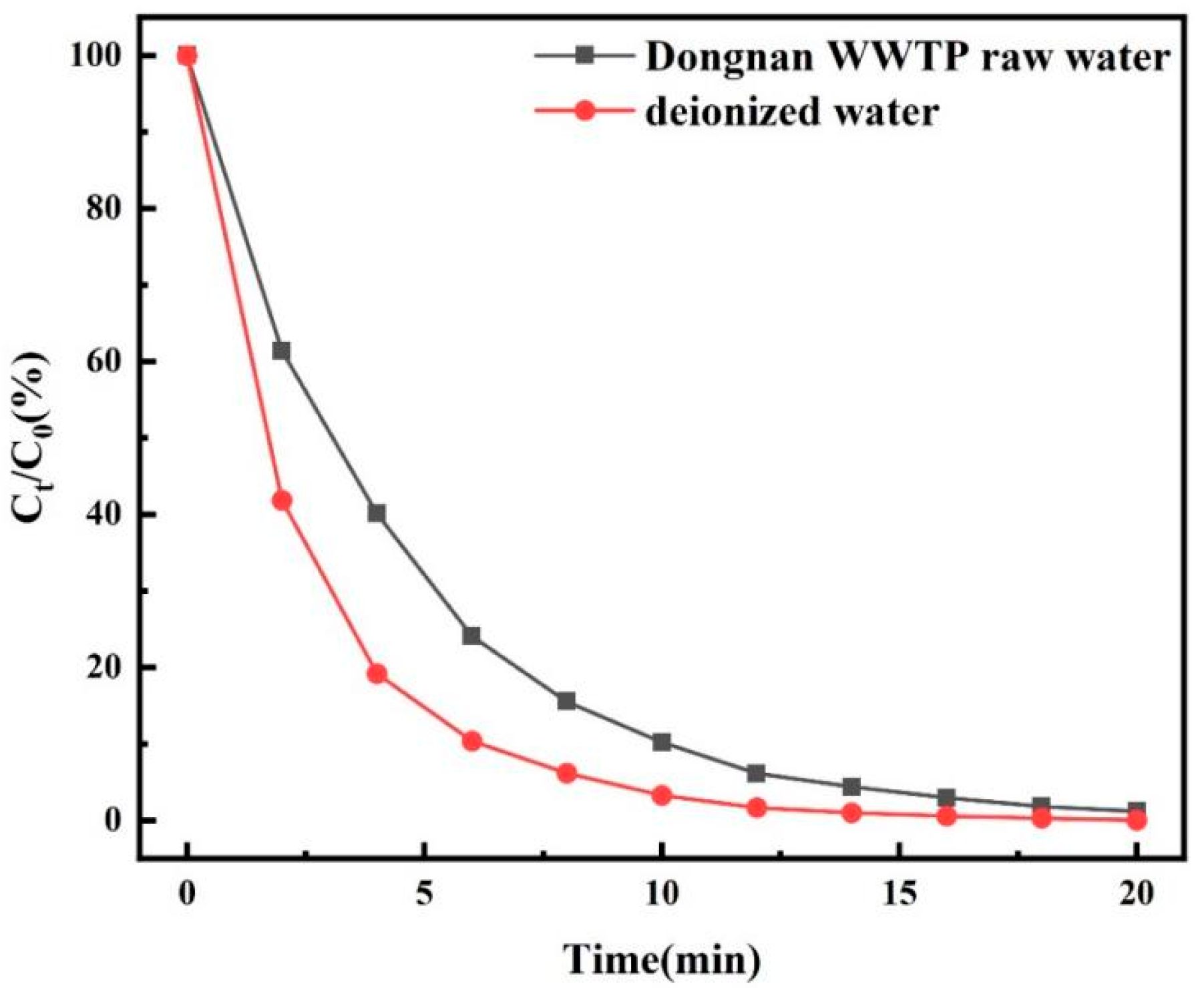

3.2. Degradation of TC by O3/PMS/FeMoBC Under the Background of Actual Water Body

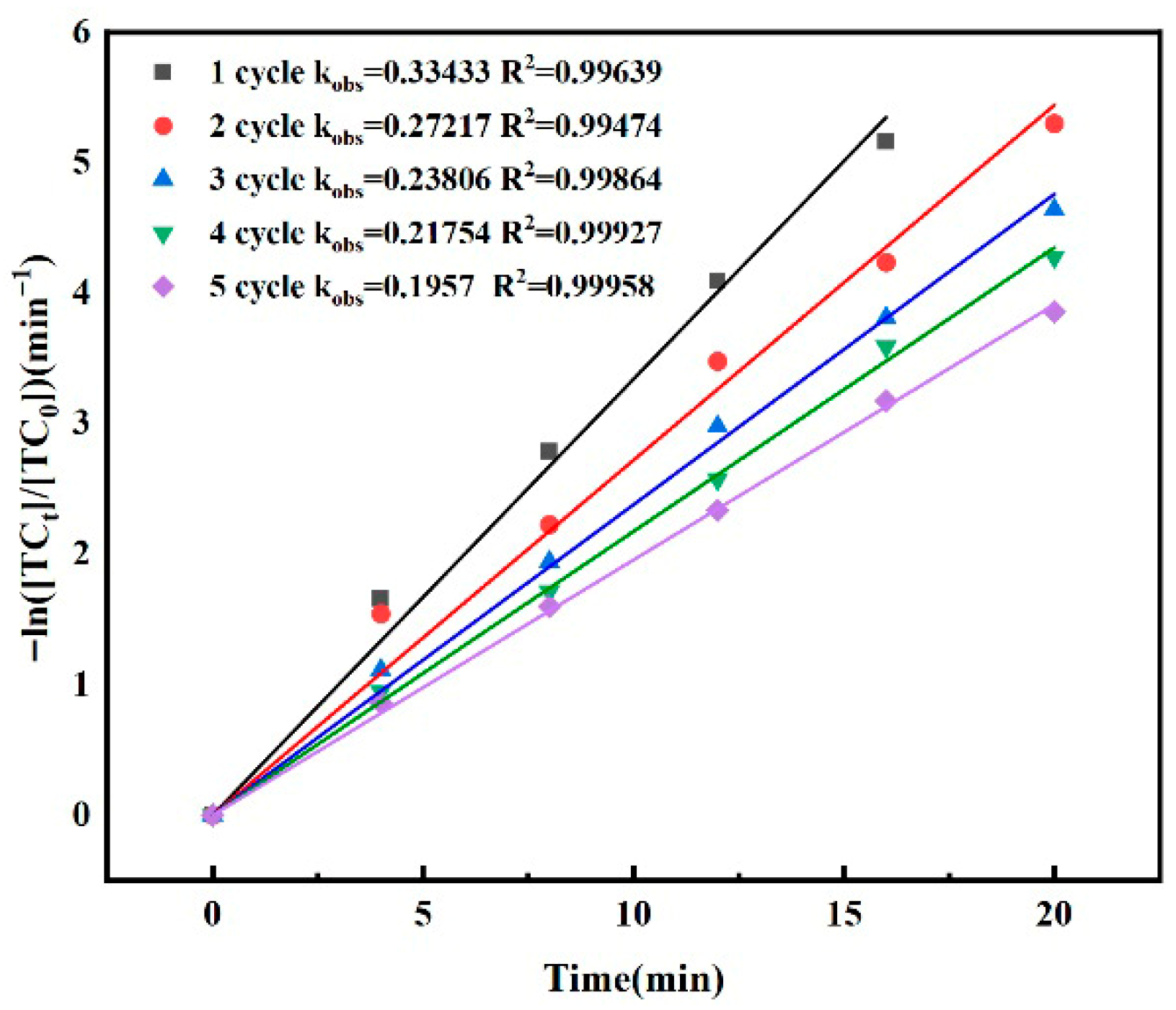

3.3. Effect of Catalyst Cycle Attenuation

4. Discussion

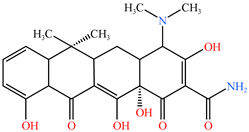

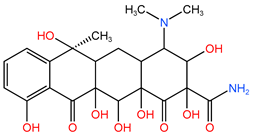

4.1. Construction of TC Molecular Model

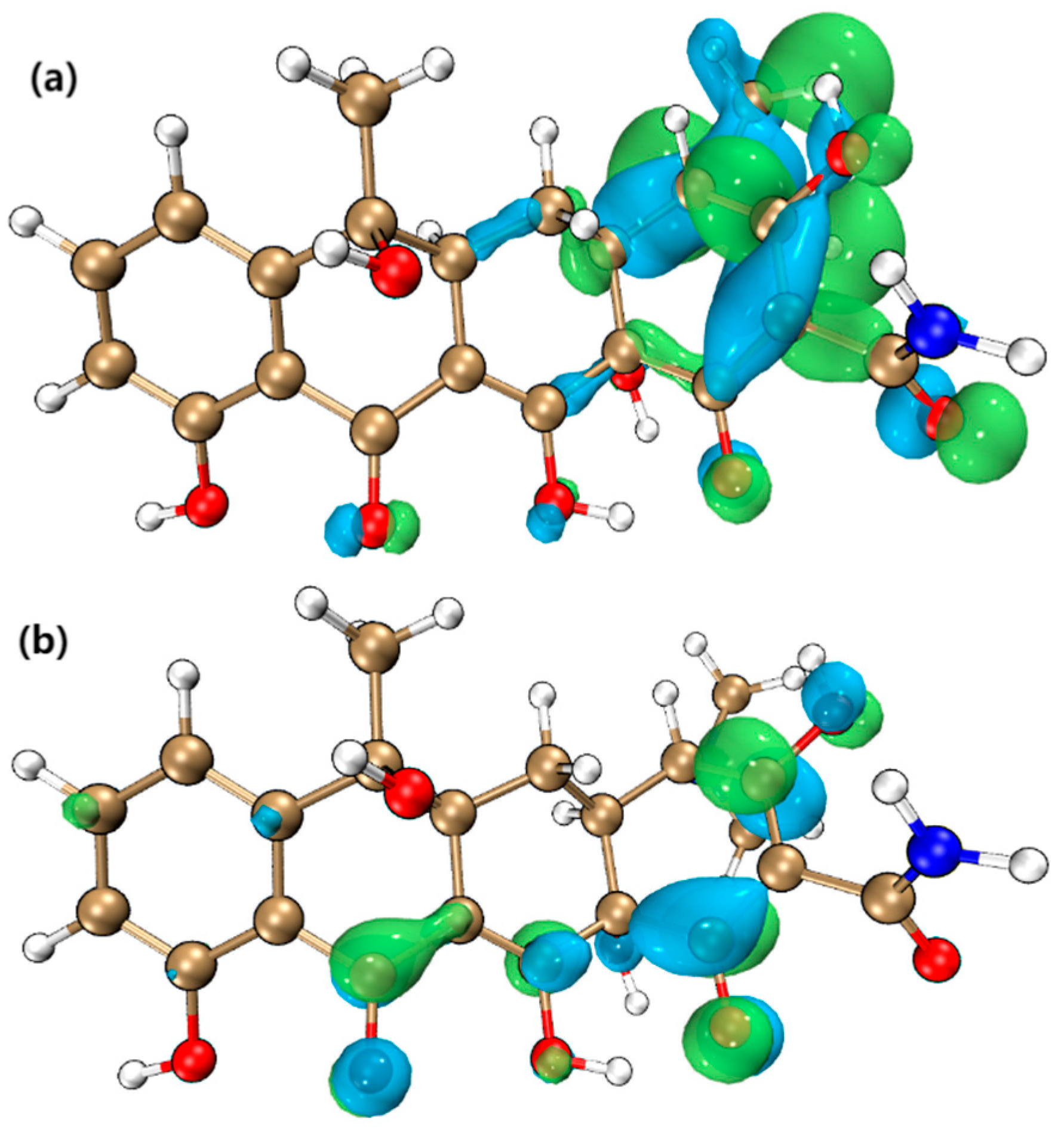

4.2. Electron Cloud Distribution

4.3. Frontier Molecular Orbital (FMO) Analysis

4.4. Fukui Index Analysis

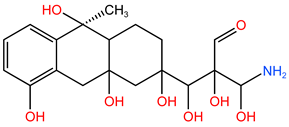

4.5. Degradation Pathway Analysis

4.6. Toxicological Analysis of TC and Its Intermediate Products

4.6.1. ECOSAR Analysis

4.6.2. T.E.S.T. Analysis

5. Conclusions and Future Directions

- (1)

- Among the three O3 processes, the O3/PMS/FeMoBC process achieved the highest mineralization degree, while the O3 process showed the lowest mineralization effect. This showed that the synergistic effect of various active oxidation substances in O3/PMS/FeMoBC system significantly improved its mineralization ability to organic matter. In contrast, when ozone only was used as oxidant, the degradation effect of organic matter was not ideal due to the limitation of its oxidation ability.

- (2)

- The raw water experiment showed that the raw water sample had a certain influence on the degradation efficiency of O3/PMS/FeMoBC, mainly because there were many types of inorganic salts and other complex organic substances in the raw water sample. These complex fluorescent substances interfered with electron transfer in the system and consumed some active oxidizing substances. However, the O3/PMS/FeMoBC process still had a 98.8% degradation rate of TC in raw water. After 60 min of treatment, the fluorescent substances in the water almost completely disappeared.

- (3)

- In the cyclic catalytic experiment, the kobs value of the material decreased after repeated use, indicating that the catalytic activity of the catalyst decreased, but the material still had certain activity after five cyclic experiments.

- (4)

- Based on the experimental results of LC–MS/MS and the quantum chemical calculation of molecular structure, the degradation path of TC was inferred. According to the theoretical calculation of DFT of Gaussian09 software, the main attack sites of TC molecular degradation were inferred. Twelve kinds of fragments with different mass-to-nucleus ratios (m/z) could be detected according to the scanning mass spectrum and the data of the intermediate products, and it could be clearly determined that the decomposition of TC main parent ions mainly occurred at C, N, O and other heteroatoms. At the initial stage of degradation, the hydrogen abstraction and substitution reactions were mainly initiated by •OH, accompanied by deamination. The hydroxyl groups of alcohols connected to benzene rings were easily converted into aldehyde groups during oxidation, but these aldehyde groups would be lost in subsequent reactions. With the deepening of degradation, the benzene ring structure would also undergo ring opening and eventually be transformed into a series of small molecular products.

- (5)

- In the toxicological analysis of TC degradation, the results of ECOSAR showed that with the gradual ring-opening and bond-breaking of TC to form small molecular compounds, its overall toxicity showed a downward trend. The analysis results of T.E.S.T. software showed that the LD50 values of intermediate products were generally low, indicating that the acute toxicity of these products was relatively small. Nevertheless, P1, P2, P3, P4 and P8 showed positive reactions in the Ames mutation test, suggesting that these specific intermediates might have genotoxicity. The prediction of developmental toxicity revealed that TC and some of its intermediate products might have a potential impact on the development of organisms, which needed to be paid attention to in environmental risk assessment.

- (6)

- Based on the above results, this study demonstrated the feasibility of the O3/PMS/FeMoBC process to degrade TC in a water environment, which provided a new idea for the treatment of high-concentrated organic wastewater. However, the discussion between the theoretical analysis of intermediate products formation and the role of catalysts in the reaction system is not still known. It might be realized through more advanced characterization means or a detailed theoretical analysis process. Therefore, the full combination of theoretical analysis and experimental means is a valuable future research direction.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sarmah, A.K.; Meyer, M.T.; Boxall, A.B.A. A global perspective on the use, sales, exposure pathways, occurrence, fate and effects of veterinary antibiotics (VAs) in the environment. Chemosphere 2006, 65, 725–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gothwal, R.; Shashidhar, T. Antibiotic pollution in the environment: A review. Clean-Soil Air Water 2015, 43, 479–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Zhou, J.L. Occurrence and behavior of antibiotics in water and sediments from the Huangpu River, Shanghai, China. Chemosphere 2014, 95, 604–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Jiang, J.; Lu, X.; Ma, J.; Liu, Y. Production of Sulfate Radical and Hydroxyl Radical by Reaction of Ozone with Peroxymonosulfate: A Novel Advanced Oxidation Process. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015, 49, 7330–7339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anipsitakis, G.P.; Dionysiou, D.D. Radical Generation by the Interaction of Transition Metals with Common Oxidants. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2004, 38, 3705–3712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ge, D.; Zeng, Z.; Arowo, M.; Zou, H.; Chen, J.; Shao, L. Degradation of methyl orange by ozone in the presence of ferrous and persulfate ions in a rotating packed bed. Chemosphere 2016, 146, 413–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, S.; Yang, X.; Shao, X.; Niu, R.; Wang, L. Activated carbon catalyzed persulfate oxidation of Azo dye acid orange 7 at ambient temperature. J. Hazard. Mater. 2011, 186, 659–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shabiimam, M.A.; Anil, K.D. Treatment of Municipal Landfill Leachate by Oxidants. Am. J. Environ. Eng. 2012, 2, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Xiao, W.; Zhang, C.; Sun, Y.; Wang, Y.; Gong, Z.; Zhan, M.; Fu, Y.; Liu, K. Effective removal of refractory organic contaminants from reverse osmosis concentrated leachate using PFS–nZVI/PMS/O3 process. Waste Manag. 2021, 128, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaafarzadeh, N.; Ghanbari, F.; Ahmadi, M. Efficient degradation of 2,4–dichlorophenoxyacetic acid by peroxymonosulfate/magnetic copper ferrite nanoparticles/ozone: A novel combination of advanced oxidation processes. Chem. Eng. J. 2017, 320, 436–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodges, B.C.; Cates, E.L.; Kim, J. Challenges and prospects of advanced oxidation water treatment processes using catalytic nanomaterials. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2018, 13, 642–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, B.; Wu, Z.; Zhou, H.; Li, J.; Zhou, C.; Xiong, Z.; Pan, Z.; Yao, G.; Lai, B. Recent advances in single–atom catalysts for advanced oxidation processes in water purification. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 412, 125253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, N.; Vione, D.; Rivoira, L.; Carena, L.; Castiglioni, M.; Bruzzoniti, M.C. A review on the degradation of pollutants by fenton-like systems based on zero-valent iron and persulfate: Effects of reduction potentials, pH, and anions occurring in waste waters. Molecules 2021, 26, 4584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.; Wang, J.; Zhang, S.; Pang, H.; Wang, X.; Chen, Z.; Li, M.; Song, G.; Qiu, M.; Yu, S. Recent advances in nanoscale zero-valent iron-based materials: Characteristics, environmental remediation and challenges. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 319, 128641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.P.; Zheng, C.H.; Huang, Y.Y.; Chen, Y.R. Removal of chlortetracycline from water using spent tea leaves-based biochar as adsorption-enhanced persulfate activator. Chemosphere 2022, 286, 131770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, H.Q.; Sun, S.D.; Cui, J.; Li, X.F. Synthesis, functional modifications, and diversified applications of molybdenum oxides micro-/nanocrystals: A review. Cryst. Growth Des. 2018, 18, 6326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, T.B.; Lan, D.; Jia, Z.R.; Gao, Z.G.; Wu, G.L. Hierarchical porous molybdenum carbide synergic morphological engineering towards broad multi-band tunable microwave absorption. Nano Res. 2024, 17, 9845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, X.Z.; Li, R.T.; Xin, H.; Fan, Y.M.; Liu, C.X.; Feng, X.H.; Wang, J.Y.; Dong, C.; Wang, C.; Li, D.; et al. In-situ dynamic carburization of Mo oxide with unprecedented high CO formation rate in reverse water-gas shift reaction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2024, 63, e202411761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Wang, S.; Ma, W.; Wang, J.; Xu, H.; Li, K.; Huang, T.; Ma, J.; Wen, G. Adding CuCo2O4–GO to inhibit bromate formation and enhance sulfamethoxazole degradation during the ozone/peroxymonosulfate process: Efficiency and mechanism. Chemosphere 2022, 286, 131829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, W.; Yi, J.; Cheng, M.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, G.; Li, L.; Du, L.; Li, B.; Wang, G.; Yang, X. When bimetallic oxides and their complexes meet Fenton-like process. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 424, 127419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Corma, A. Bimetallic Sites for Catalysis: From Binuclear Metal Sites to Bimetallic Nanoclusters and Nanoparticles. Chem. Rev. 2023, 123, 4855–4933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Li, Q.; Chen, X.; Yan, B.; Li, S.; Deng, H.; Lu, H. Efficacy, Kinetics, and Mechanism of Tetracycline Degradation in Water by O3/PMS/FeMoBC Process. Nanomaterials 2025, 15, 1108. [Google Scholar]

- Choe, Y.J.; Kim, J.S.; Kim, H.; Kim, J. Open Ni site coupled with SO42– functionality to prompt the radical interconversion of[rad] •OH ↔ SO4•− exploited to decompose refractory pollutants. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 400, 125971. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, F.; Huang, Y.; Wen, P.; Li, Q. Transformation mechanisms of refractory organic matter in mature landfill leachate treated using an Fe0–participated O3/H2O2 process. Chemosphere 2021, 263, 128198. [Google Scholar]

- Li, T.; Wang, X.; Chen, Y.; Liang, J.; Zhou, L. Producing •OH, SO4•− and •O2− in heteroge–neous Fenton reaction induced by Fe3O4− modified schwertmannite. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 393, 124735. [Google Scholar]

- Nasser, A.H.; Mathew, A.P. Cellulose–zeolitic imidazolate frameworks (CelloZIFs) for multifunctional environmental remediation: Adsorption and catalytic degradation. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 426, 131733. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, Z.; Dwivedi, A.D.; Lee, W.N.; Zhao, X.; Liu, W.; Sillanp, M.; Zhao, D.; Huang, C.; Fu, J. Application of nanotechnologies for removing pharmaceutically active compounds from water: Development and future trends. Environ. Sci. Nano 2018, 5, 27–47. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, H.; Feng, W.; Li, Q. Degradation Efficiency Analysis of Sulfadiazine in Water by Ozone/Persulfate Advanced Oxidation Process. Water 2022, 14, 2476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, S.; Chen, M.; Bai, Y.; Liu, Y.; Mei, J.; Lai, B. Enhanced TC degradation by persulfate activation with carbon–coated CuFe2O4: The radical and non–radical co–dominant mechanism, DFT calculations and toxicity evaluation. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 461, 132417. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zhang, T.; Zhang, S.; Wu, C.; Zuo, H.; Yan, Q. Novel La3+/Sm3+ co–doped Bi5O7I with efficient visible–light photocatalytic activity for advanced treatment of wastewater: Internal mechanism, TC degradation pathway, and toxicity analysis. Chemosphere 2023, 313, 137540. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y.; Rong, C.; Zhang, R.; Liu, S. Evaluating frontier orbital energy and HOMO/LUMO gap with descriptors from density functional reactivity theory. J. Mol. Model. 2017, 23, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janani, S.; Rajagopal, H.; Muthu, S.; Aayisha, S.; Raja, M. Molecular structure, spectroscopic (FT–IR, FT–Raman, NMR), HOMO–LUMO, chemical reactivity, AIM, ELF, LOL and Molecular docking studies on 1–Benzyl–4–(N–Boc–amino) piperidine. J. Mol. Struct. 2021, 1230, 129657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janani, S.; Rajagopal, H.; Sakthivel, S.; Aayisha, S.; Raja, M.; Irfan, A.; Javed, S.; Muthu, S. Molecular structure, electronic properties, ESP map (polar aprotic and polar protic solvents), and topology investigations on 1–(tert-Butoxycarbonyl)–3–piperidinecarboxylic acid–Anticancer therapeutic agent. J. Mol. Struct. 2022, 1268, 133696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadre, S.R.; Surehs, C.H.; Mohan, N. Electrostatic Potential Topology for Probing Molecular Structure, Bonding and Reactivity. Molecules 2021, 26, 3289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aihara, J. Reduced HOMO−LUMO Gap as an Index of Kinetic Stability for Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons. J. Phys. Chem. A 1999, 103, 7487–7495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dokmeci, M.; Kopreski, R.; Miller, G. Substituent Effects in Pentacenes: Gaining Control over HOMO−LUMO Gaps and Photooxidative Resistances. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 16274–16286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mineva, T.; Parvanov, V.; Petrov, N.; Russo, N. Fukui Indices from Perturbed Kohn−Sham Orbitals and Regional Softness from Mayer Atomic Valences. J. Phys. Chem. A 2001, 105, 1959–1967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omoto, K.; Fujimoto, H. Electron–Donating and –Accepting Strength of Enoxysilanes and Allylsilanes in the Reaction with Aldehydes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997, 119, 5366–5372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaklika, J.; Hladyszowski, J.; Ordon, P.; Komorowski, L. From the Electron Den–sity Gradient to the Quantitative Reactivity Indicators: Local Softness and the Fukui Function. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 7745–7758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, L.; Wang, K.; Day, G.S.; Ryder, M.R.; Zhou, H. Destruction of Metal–Organic Frameworks: Positive and Negative Aspects of Stability and Lability. Chem. Rev. 2020, 120, 13087–13133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Z.; Xia, D.; Shen, M.; Zhu, D.; Cai, H.; Wu, M.; Zhu, Q.; Kang, Y. Tetracycline degradation by Klebsiella sp. strain TR5: Proposed degradation pathway and possible genes involved. Chemosphere 2020, 253, 126729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.; Dai, H.; Tan, C.; Pan, Q.; Hu, F.; Peng, X. Photo–Fenton degradation of tetracycline over Z–scheme Fe–g–C3N4/Bi2WO6 heterojunctions: Mechanism insight, degradation pathways and DFT calculation. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2022, 310, 121326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Yin, R.; Zeng, L.; Guo, W.; Zhu, M. Insight into the effects of hydroxyl groups on the rates and pathways of tetracycline antibiotics degradation in the carbon black activated peroxydisulfate oxidation process. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 412, 125256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sre, V.V.; Syed, A.; Janani, B.; Elgorban, A.M.; Al-Shwaiman, H.A.; Wong, L.S.; Khan, S.S. Construction of novel S-defects rich ZnCdS nanoparticles for synergistic visible light assisted photocatalytic degradation of rhodamine B: Insights into mechanism, pathway and by-products toxicity evaluation. Colloids Surf. A 2024, 697, 134447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallika, B.; Nagaraja, K.; Arunpandian, M.; Oh, T.H. Enhanced photocatalytic detoxification of emerging carcinogenic pollutants using bael gum-stabilized CuO@ZnO nanoparticles for antibacterial activity and environmental risk evaluation. Colloids Surf. A 2025, 725, 137624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damia, B.; Bozo, Z.; Antoni, G. Toxicity tests in wastewater and drinking water treatment processes: A complementary assessment tool to be on your radar. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 104262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gramatica, P. Principles of QSAR Modeling: Comments and Suggestions from Personal Experience. Int. J. Quant. Struct. Prop. Relatsh. (IJQSPR) 2020, 5, 61–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De, P.; Kar, S.; Ambure, P.; Roy, K. Prediction reliability of QSAR models: An overview of various validation tools. Arch. Toxicol. 2022, 96, 1279–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Water Quality Index | Before Treatment (Including TC) | After Treatment |

|---|---|---|

| chemical oxygen demand (COD) | 204.68 mg/L | 45.61 mg/L |

| total nitrogen (TN) | 39.68 mg/L | 25.06 mg/L |

| ammonia nitrogen (NH3–N) | 33.93 mg/L | 21.24 mg/L |

| total phosphorus (TP) | 5.59 mg/L | 4.55 mg/L |

| pH | 7.41 | 6.48 |

| Zone | Organic Matter Type | Fluorescence Peak Position (Ex/Em) |

|---|---|---|

| I | Simple aromatic protein I (Tyrosine) | 240–250 nm/280–330 nm |

| II | Simple aromatic protein II (Tryptophan) | 240–250 nm/330–380 nm |

| III | Aromatic protein or phenols (Fulvic acid) | 240–250 nm/380–550 nm |

| IV | Aromatic protein or phenols (Fulvic acid) | 250–400 nm/300–380 nm |

| V | Humic acids | 250–400 nm/380–550 nm |

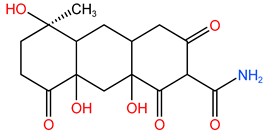

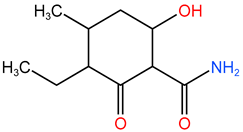

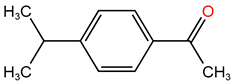

| Compound ID | Experimental m/z | Molecular Formula | Proposed Chemical Structure |

|---|---|---|---|

| TC | 445.16 | C22H24N2O8 |  |

| P1 | 481.569 | C22H28O10N2 |  |

| P2 | 477.152 | C22H24O10N2 |  |

| P3 | 437.314 | C20H24O9N2 |  |

| P4 | 419.458 | C20H22O8N2 |  |

| P5 | 397.55 | C19H27O8N |  |

| P6 | 338.393 | C16H21O7N |  |

| P7 | 148.151 | C9H8O2 |  |

| P8 | 340.345 | C19H16O6 |  |

| P9 | 217.226 | C13H14O3 |  |

| P10 | 199.092 | C10H17O3N |  |

| P11 | 162.18 | C11H14O |  |

| P12 | 134.117 | C6H14O3 |  |

| Atom | fk+ | fk− | fk0 | Atom | fk+ | fk− | fk0 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (C) | 0.03019 | 0.03378 | 0.03198 | 29 (O) | 0.01981 | 0.0335 | 0.02665 |

| 2 (C) | 0.0346 | 0.02794 | 0.03127 | 30 (H) | 0.00286 | 0.003 | 0.00293 |

| 3 (C) | 0.01293 | 0.01309 | 0.01301 | 31 (H) | 0.00087 | 0.0027 | 0.00178 |

| 4 (C) | 0.02114 | 0.01392 | 0.01753 | 32 (C) | 0.02732 | 0.01332 | 0.02032 |

| 5 (C) | 0.02513 | 0.03568 | 0.0304 | 33 (N) | 0.01131 | 0.02909 | 0.0202 |

| 6 (C) | 0.04273 | 0.02554 | 0.03414 | 34 (H) | 0.00176 | 0.00245 | 0.0021 |

| 7 (C) | 0.00683 | 0.01317 | 0.01 | 35 (H) | 0.00182 | 0.00248 | 0.00215 |

| 8 (C) | 0.00495 | 0.01405 | 0.0095 | 36 (O) | 0.01658 | 0.06473 | 0.04065 |

| 9 (C) | 0.03007 | 0.0506 | 0.04033 | 37 (O) | 0.03648 | 0.01495 | 0.02571 |

| 10 (C) | 0.05907 | 0.03024 | 0.04465 | 38 (H) | 0.00439 | 0.00121 | 0.0028 |

| 11 (C) | 0.04058 | 0.03177 | 0.03618 | 39 (N) | 0.01113 | 0.08643 | 0.04878 |

| 12 (C) | 0.00372 | 0.0102 | 0.00696 | 40 (C) | 0.0021 | 0.01255 | 0.00733 |

| 13 (C) | 0.00279 | 0.00891 | 0.00585 | 41 (H) | 0.00086 | 0.00808 | 0.00447 |

| 14 (H) | 0.00325 | 0.00273 | 0.00299 | 42 (H) | 0.00076 | 0.00278 | 0.00177 |

| 15 (H) | 0.00254 | 0.00317 | 0.00285 | 43 (H) | 0.00065 | 0.00183 | 0.00124 |

| 16 (H) | 0.00454 | 0.00227 | 0.00341 | 44 (C) | 0.00286 | 0.0132 | 0.00803 |

| 17 (H) | 0.00074 | 0.002 | 0.00137 | 45 (H) | 0.00053 | 0.00262 | 0.00157 |

| 18 (C) | 0.03936 | 0.03418 | 0.03677 | 46 (H) | 0.00126 | 0.00824 | 0.00475 |

| 19 (C) | 0.0977 | 0.01822 | 0.05796 | 47 (H) | 0.00137 | 0.00254 | 0.00195 |

| 20 (C) | 0.03522 | 0.04101 | 0.03811 | 48 (C) | 0.10183 | 0.01352 | 0.05768 |

| 21 (H) | 0.0017 | 0.0023 | 0.002 | 49 (C) | 0.0729 | 0.021 | 0.04695 |

| 22 (H) | 0.00377 | 0.00169 | 0.00273 | 50 (O) | 0.07231 | 0.04059 | 0.05645 |

| 23 (C) | 0.0013 | 0.00738 | 0.00434 | 51 (O) | 0.06216 | 0.08442 | 0.07329 |

| 24 (H) | 0.0003 | 0.00121 | 0.00076 | 52 (O) | 0.01558 | 0.02516 | 0.02037 |

| 25 (H) | 0.00065 | 0.00168 | 0.00117 | 53 (H) | 0.00216 | 0.00193 | 0.00204 |

| 26 (H) | 0.00056 | 0.00131 | 0.00094 | 54 (O) | 0.01006 | 0.03036 | 0.02021 |

| 27 (O) | 0.00607 | 0.03957 | 0.02282 | 55 (H) | 0.00174 | 0.00201 | 0.00187 |

| 28 (H) | 0.002 | 0.00264 | 0.00232 | 56 (H) | 0.0022 | 0.00515 | 0.00367 |

| Compound | Acute Toxicity (mg/L) | Chronic Toxicity (ChV) (mg/L) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fish LC50 (96 h) | Daphnid LC50 (48 h) | Green Algae EC50 (96 h) | Fish LC50 | Daphnid LC50 | Green Algae EC50 | |

| TC | 13,100 | 1060 | 1890 | 2490 | 59.9 | 474 |

| P1 | 66,500 | 4780 | 10,700 | 18,100 | 240 | 2470 |

| P2 | 56.70 | 7.02 | 5.38 | 2.950 | 0.597 | 1.83 |

| P3 | 321,000 | 20,300 | 58,800 | 129,000 | 901 | 12400 |

| P4 | 49,200 | 3580 | 7850 | 12,900 | 182 | 1830 |

| P5 | 3480 | 4900 | 1740 | 4700 | 23 | 334 |

| P6 | 772,000 | 308,000 | 53,100 | 49,700 | 11200 | 6320 |

| P7 | 62.10 | 36.40 | 30.70 | 6.290 | 3.850 | 8.58 |

| P8 | 9030 | 4390 | 1720 | 735 | 278 | 319 |

| P9 | 6.99 | 4.59 | 6.22 | 0.811 | 0.670 | 2.25 |

| P10 | 14,800 | 6880 | 2230 | 1140 | 383 | 373 |

| P11 | 12.90 | 8.12 | 9.31 | 1.420 | 1.060 | 3.08 |

| P12 | 5020 | 2410 | 885 | 402 | 146 | 159 |

| Compound | Oral Rat LD50 | Ames Mutagenicity | Developmental Toxicity | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predicted Value (mg/kg) | Predicted Value | Predicted Result | Developmental Toxicity Value | Developmental Toxicity Result | |

| TC | 806.96 | 0.60 | Positive | 0.86 | toxicant |

| P1 | 1042.49 | 0.68 | Positive | 0.60 | toxicant |

| P2 | 964.51 | 0.61 | Positive | 0.72 | toxicant |

| P3 | 1299.00 | 0.69 | Positive | 0.71 | toxicant |

| P4 | 1531.92 | 0.70 | Positive | 0.89 | toxicant |

| P5 | 414.69 | 0.20 | Negative | 0.50 | toxicant |

| P6 | 1068.17 | 0.45 | Negative | 0.78 | toxicant |

| P7 | N/A | 0.27 | Negative | 0.43 | non-toxicant |

| P8 | 419.99 | 0.55 | Positive | 0.92 | toxicant |

| P9 | 381.32 | 0.49 | Negative | 0.89 | toxicant |

| P10 | 5941.00 | 0.21 | Negative | 0.90 | toxicant |

| P11 | 1711.39 | 0.34 | Negative | 0.83 | toxicant |

| P12 | 7445.82 | 0.09 | Negative | 0.32 | non-toxicant |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, X.; Li, Q.; Wang, J.; Wu, Z.; Li, S.; Lu, H. Feasibility Analysis of Tetracycline Degradation in Water by O3/PMS/FeMoBC Process. Molecules 2025, 30, 4810. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244810

Li X, Li Q, Wang J, Wu Z, Li S, Lu H. Feasibility Analysis of Tetracycline Degradation in Water by O3/PMS/FeMoBC Process. Molecules. 2025; 30(24):4810. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244810

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Xuemei, Qingpo Li, Jian Wang, Zheng Wu, Shengnan Li, and Hai Lu. 2025. "Feasibility Analysis of Tetracycline Degradation in Water by O3/PMS/FeMoBC Process" Molecules 30, no. 24: 4810. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244810

APA StyleLi, X., Li, Q., Wang, J., Wu, Z., Li, S., & Lu, H. (2025). Feasibility Analysis of Tetracycline Degradation in Water by O3/PMS/FeMoBC Process. Molecules, 30(24), 4810. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244810