Adsorption of Zinc Ions from Aqueous Solutions on Polymeric Sorbents Based on Acrylonitrile-Divinylbenzene Networks Bearing Aminophosphonate Groups

Abstract

1. Introduction

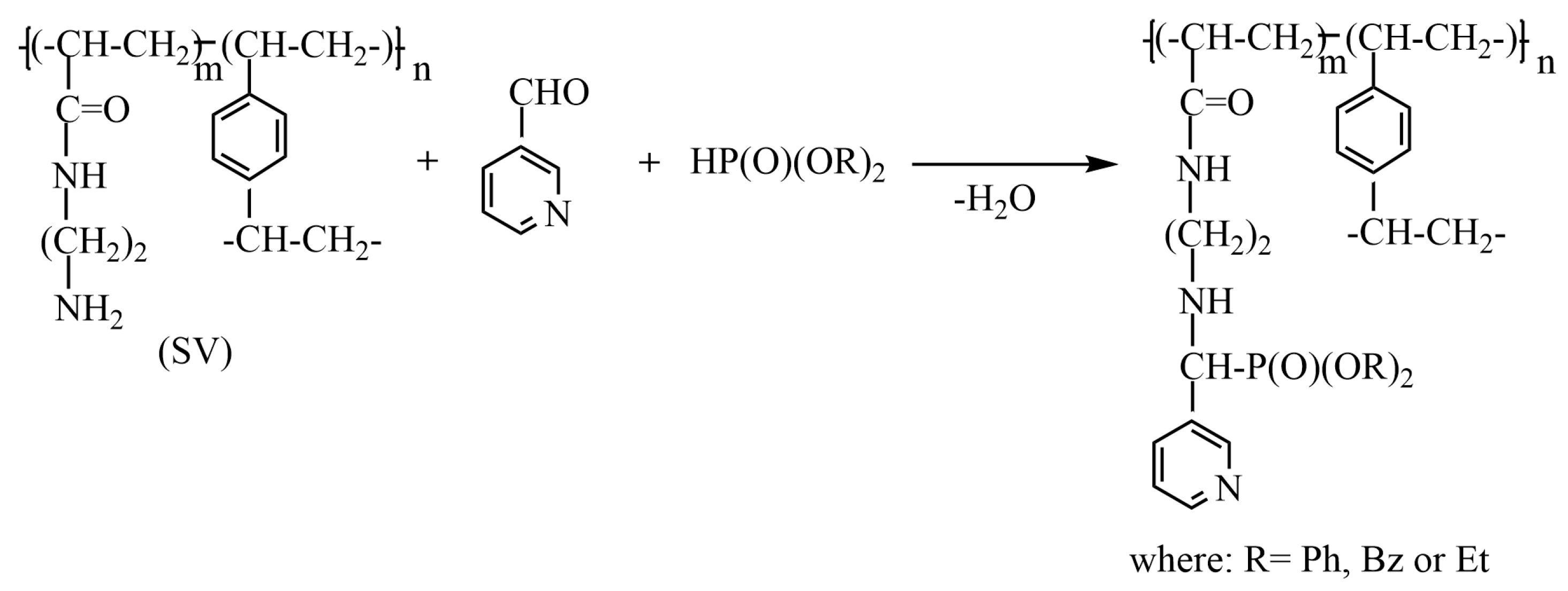

2. Results and Discussion

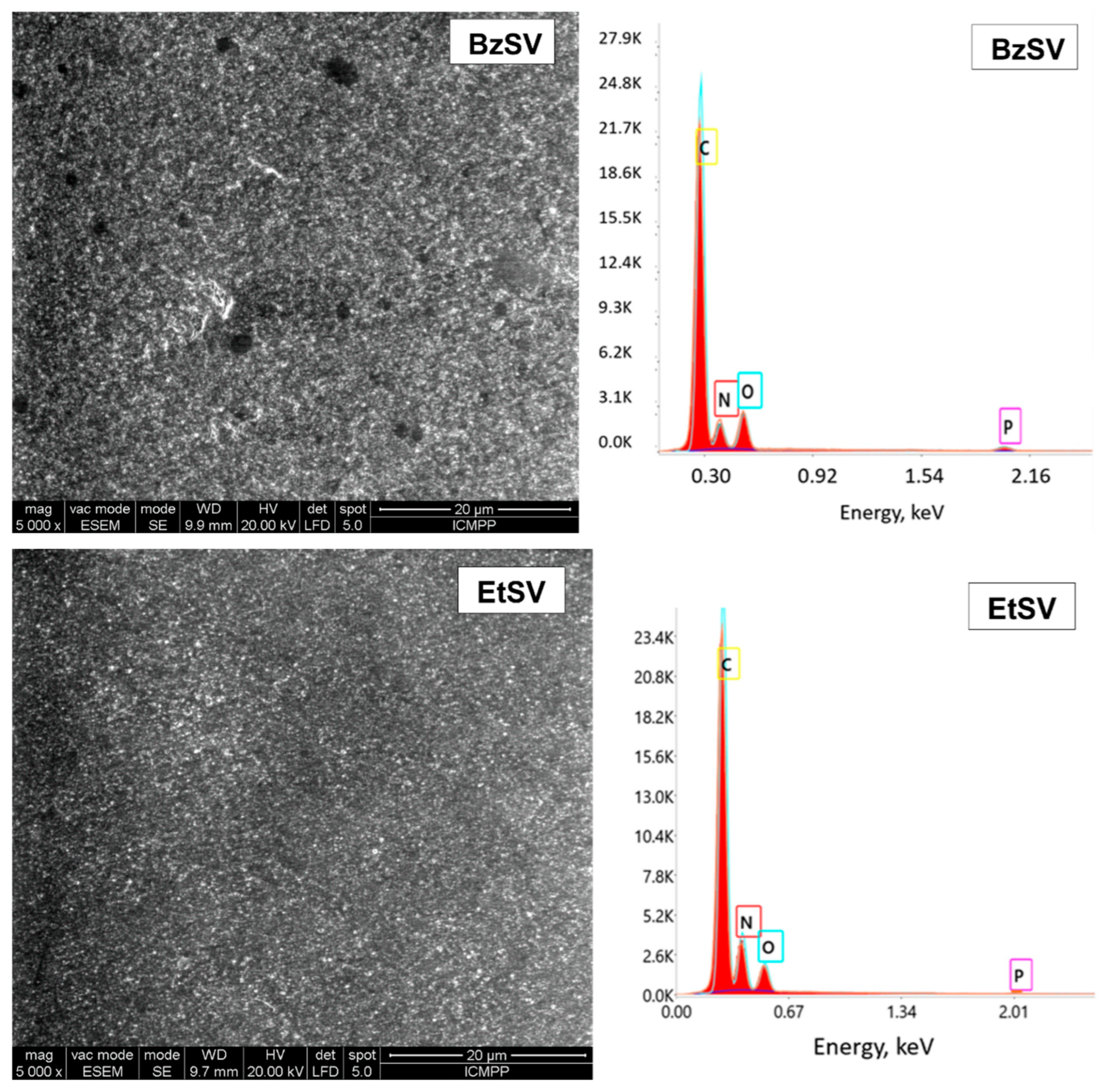

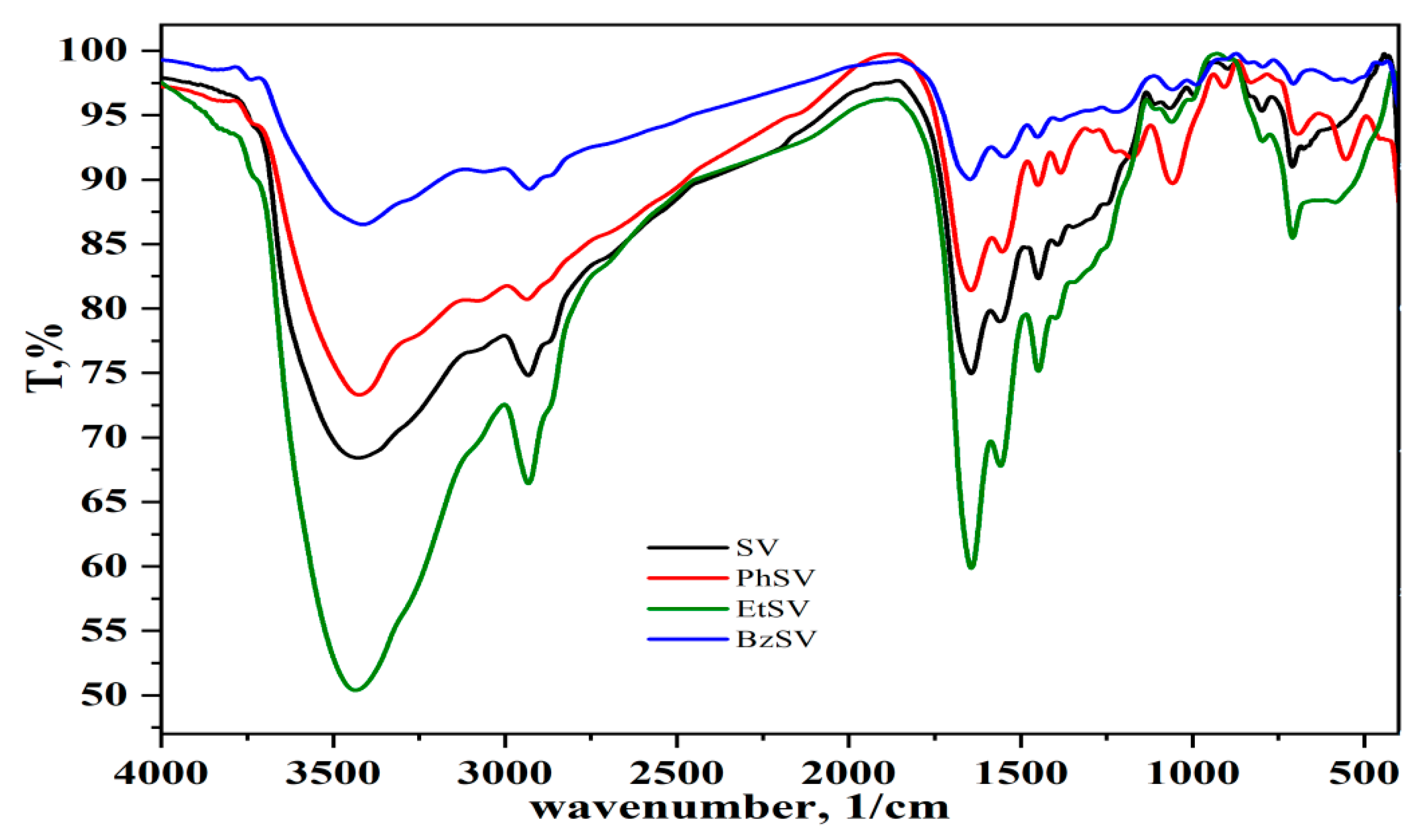

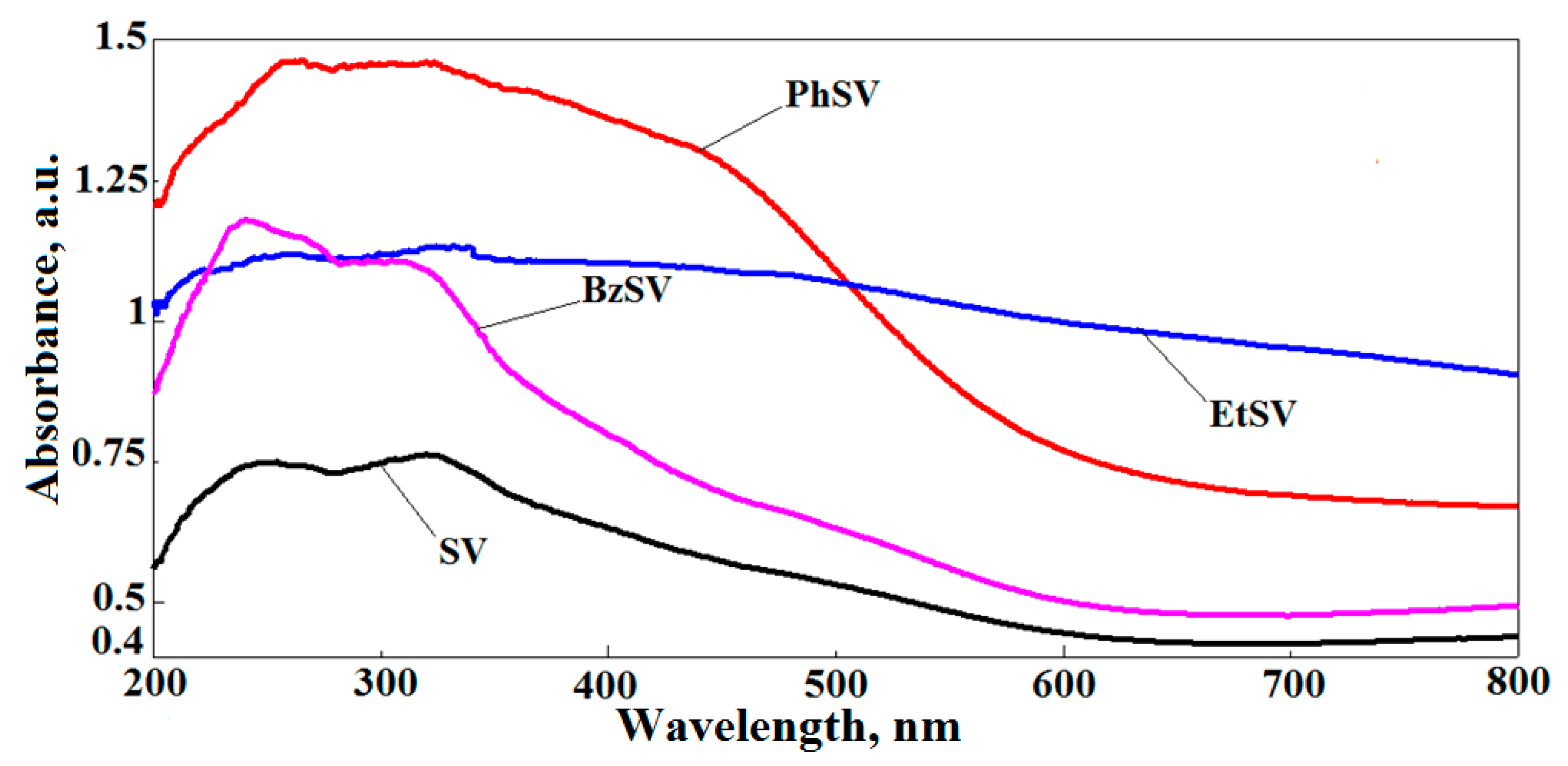

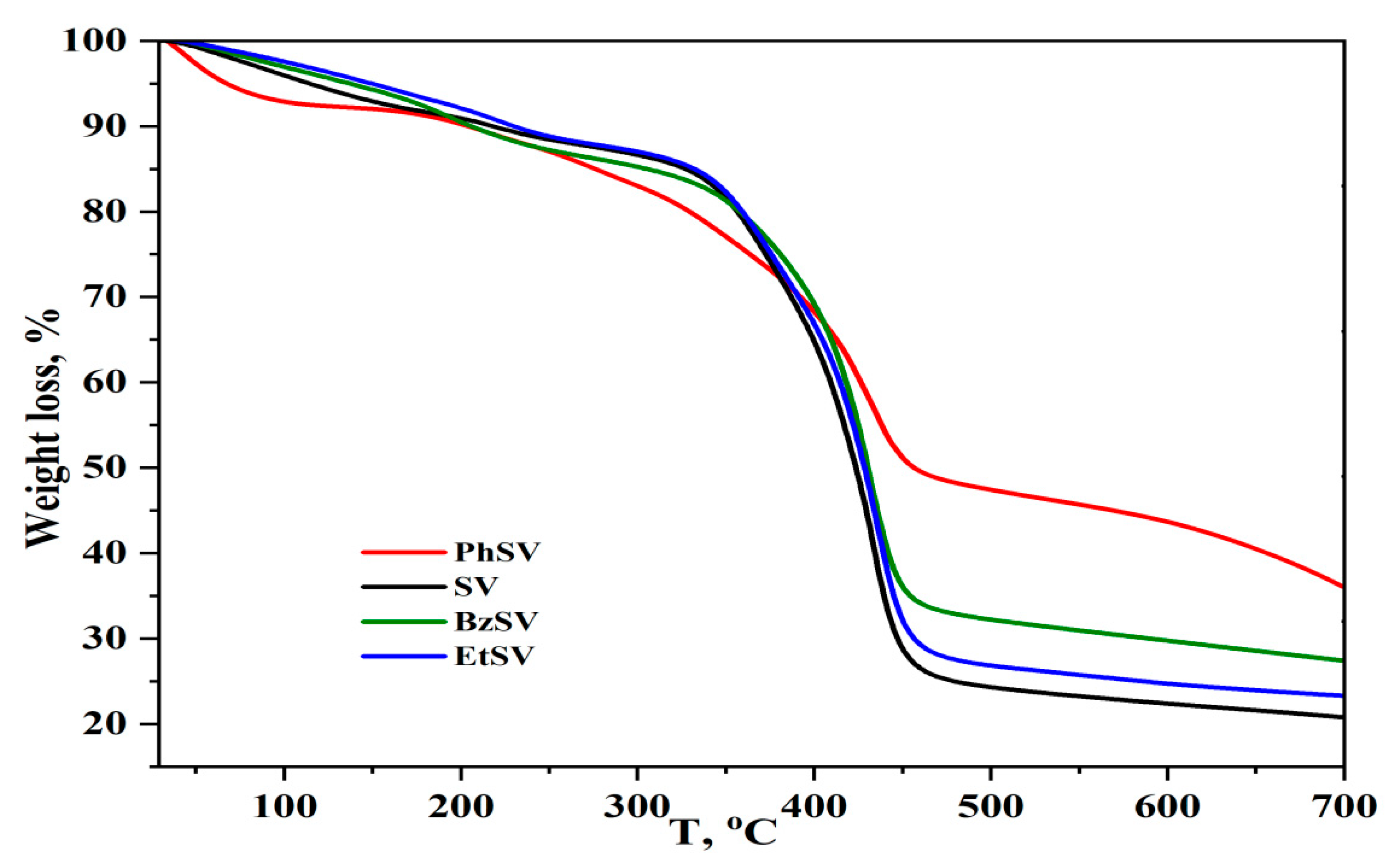

2.1. Chemical and Morphological Characterization of Polymer Chelators

2.2. Adsorption Study

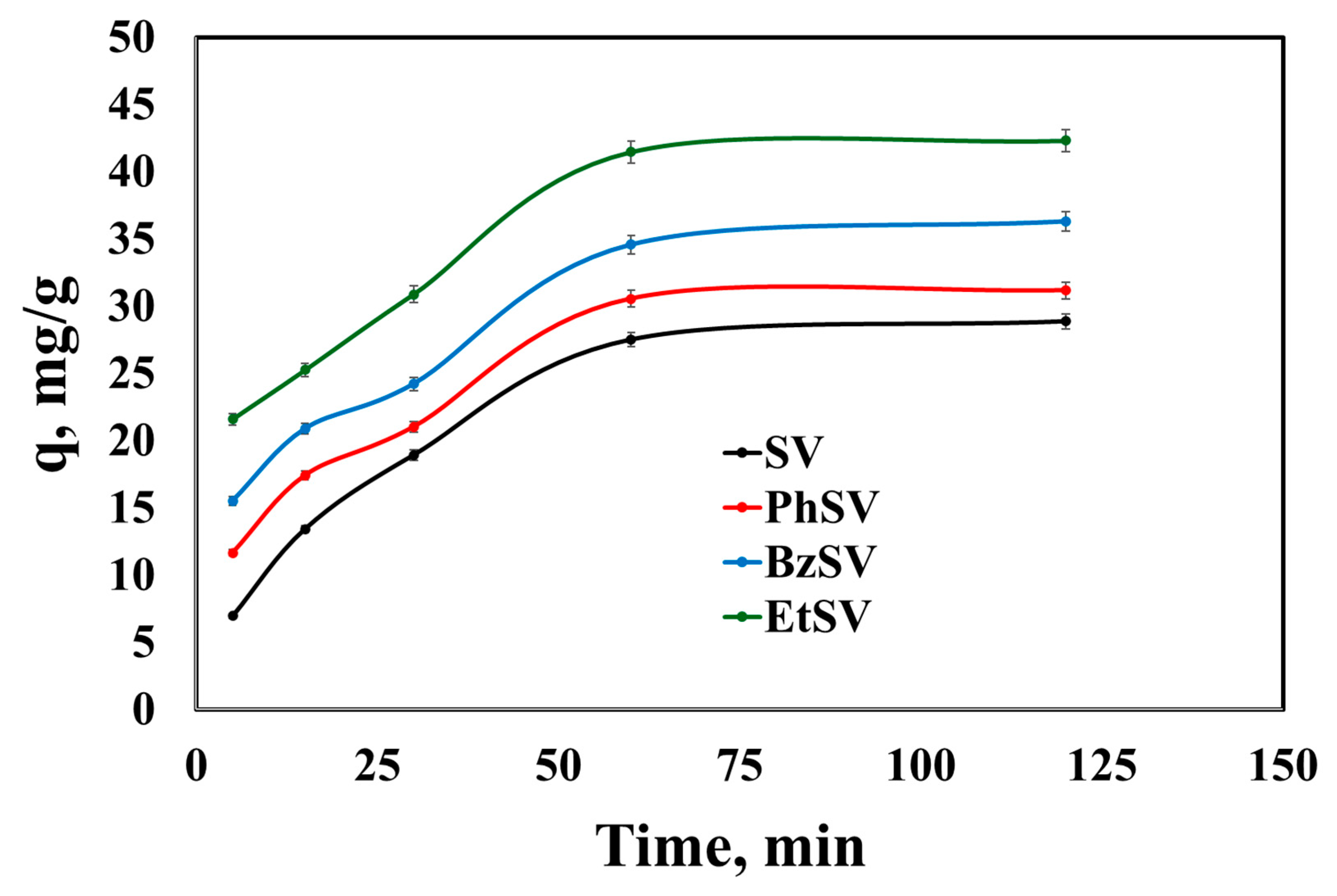

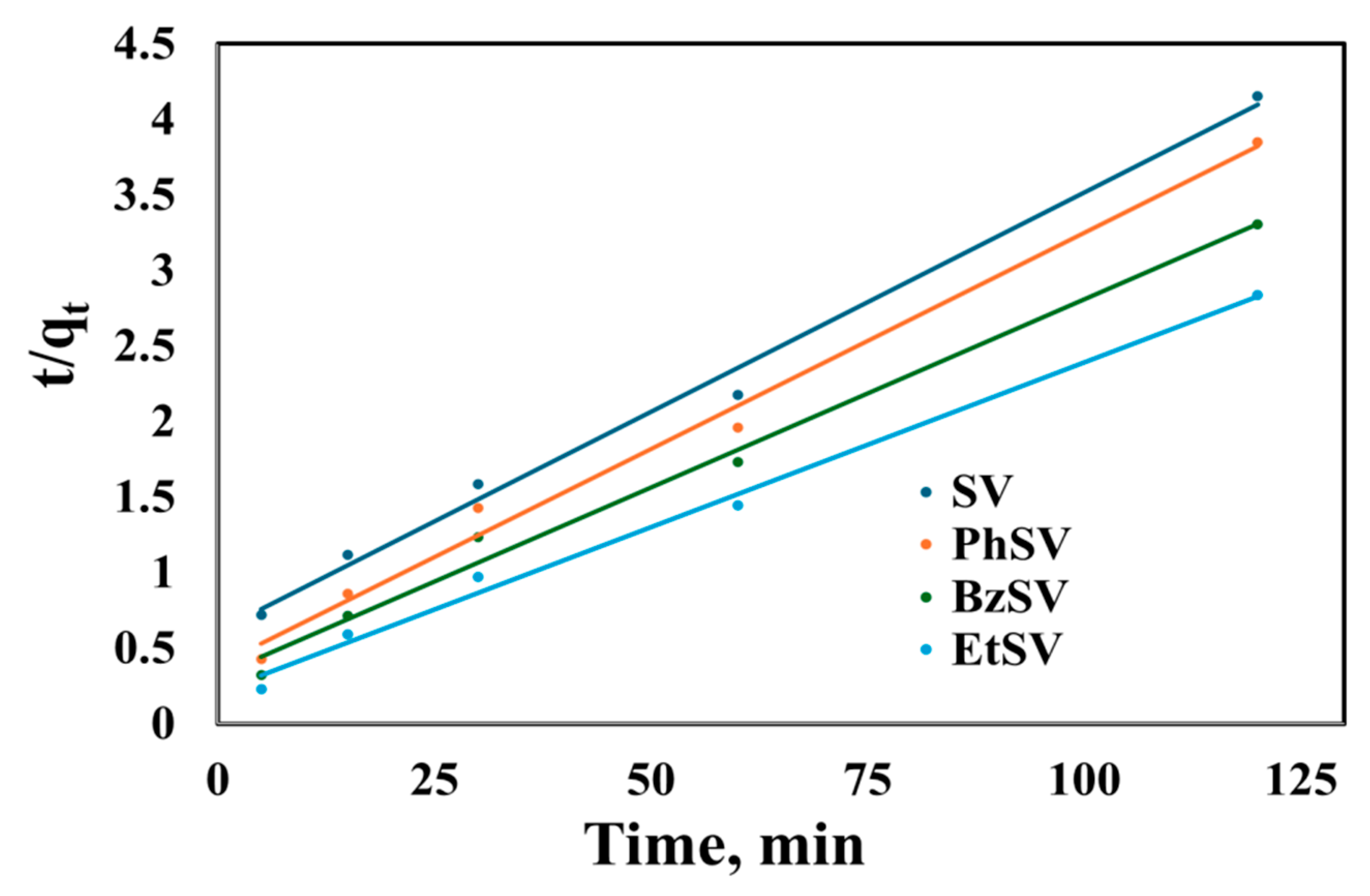

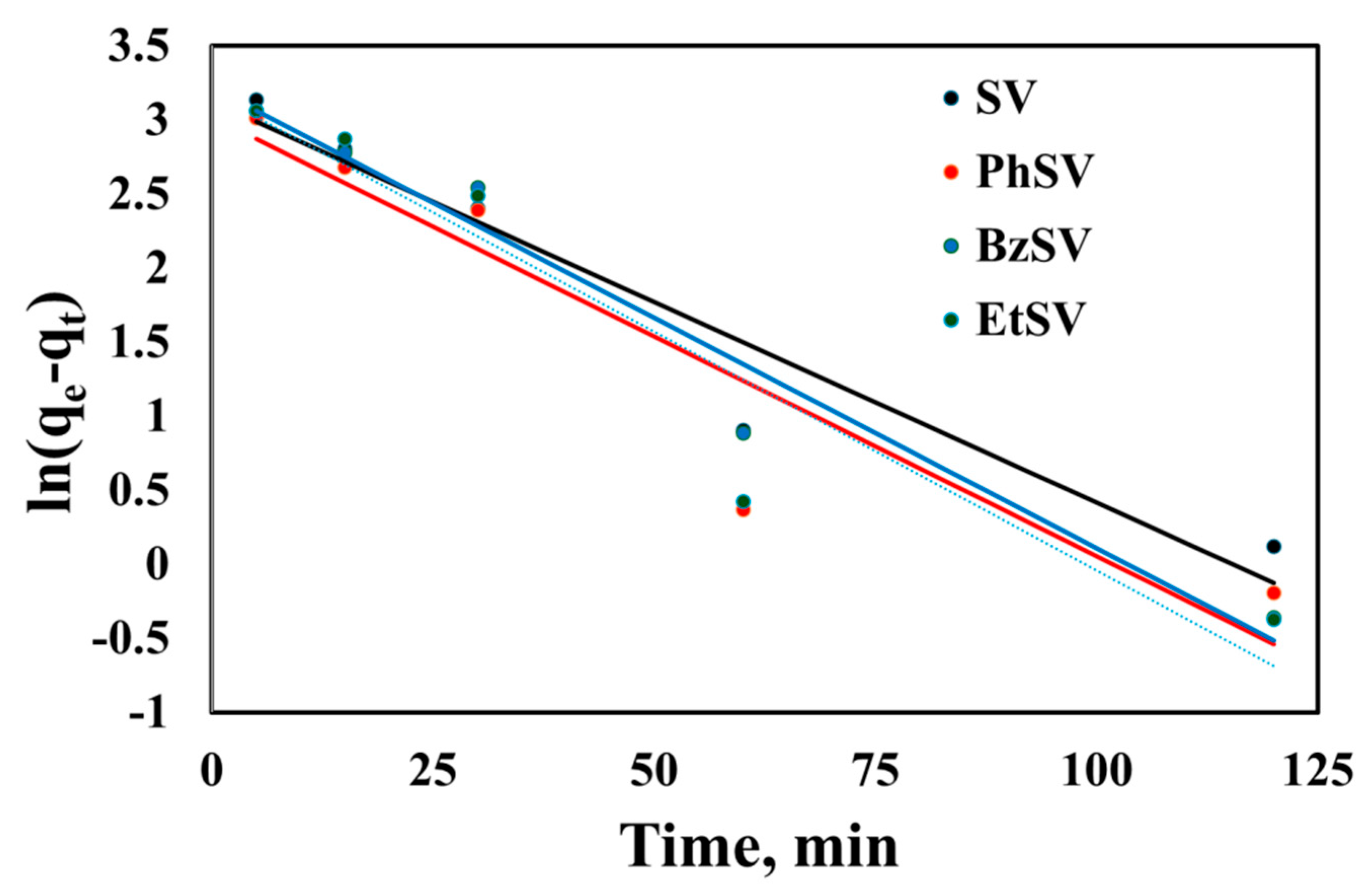

2.2.1. Kinetic Studies

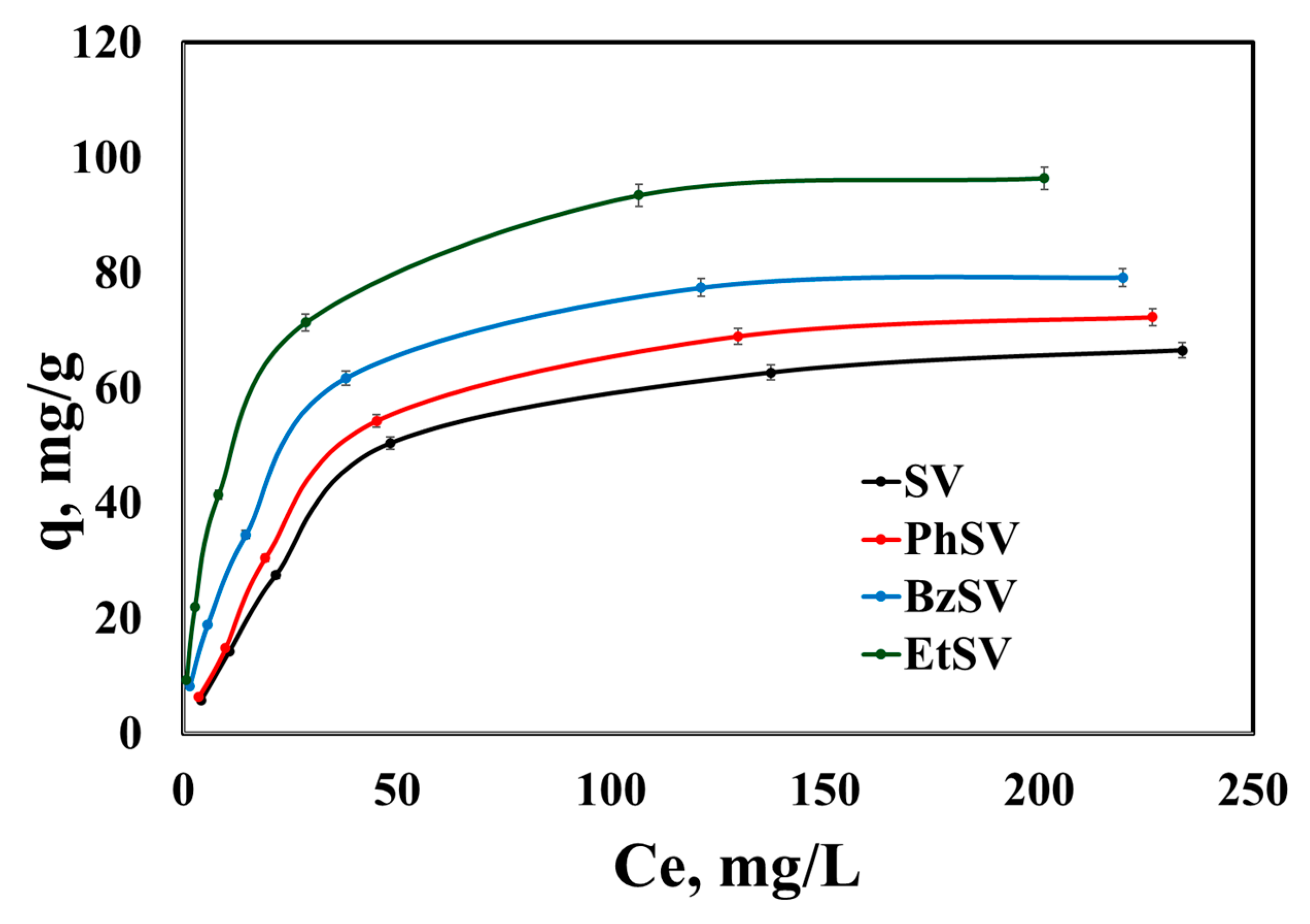

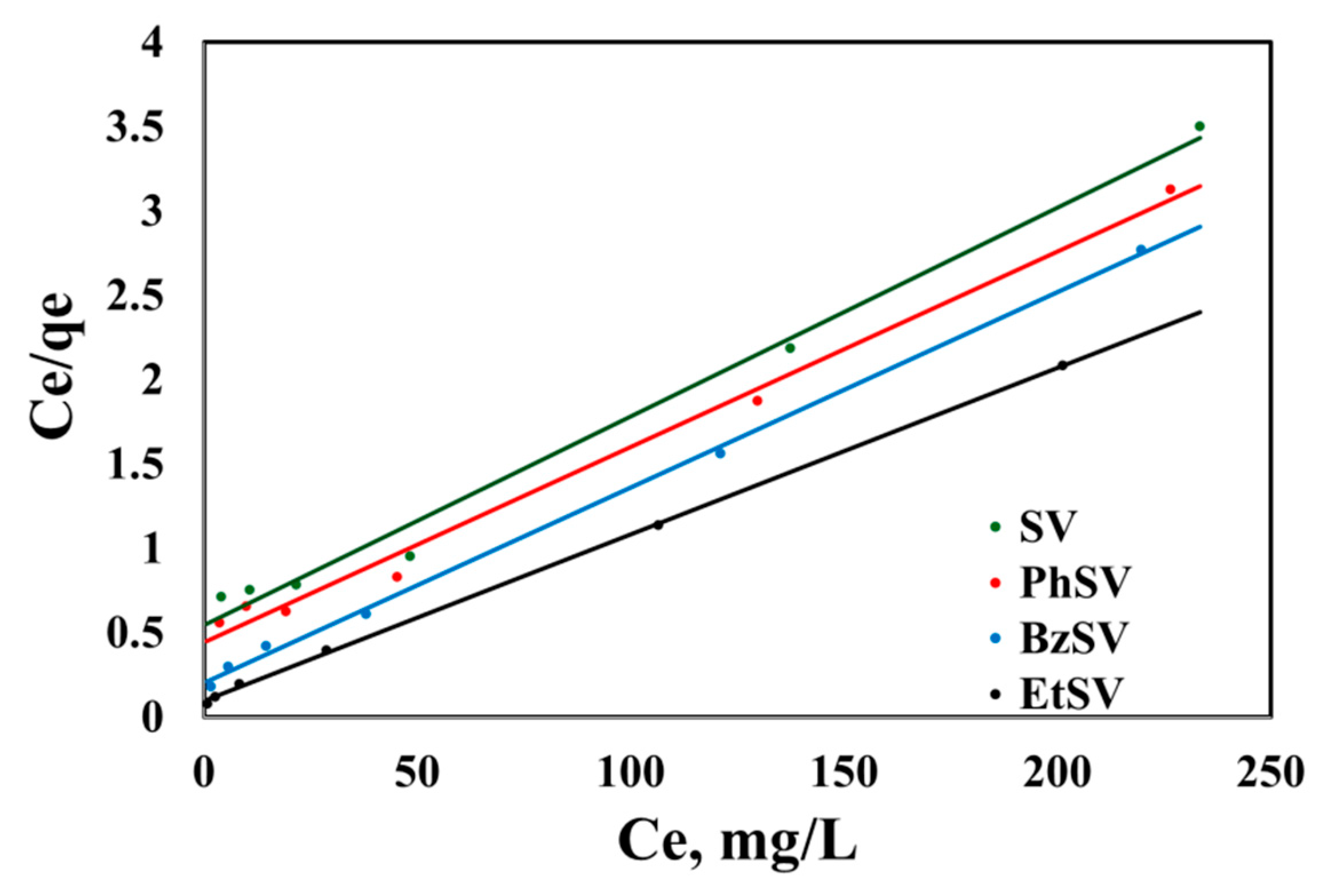

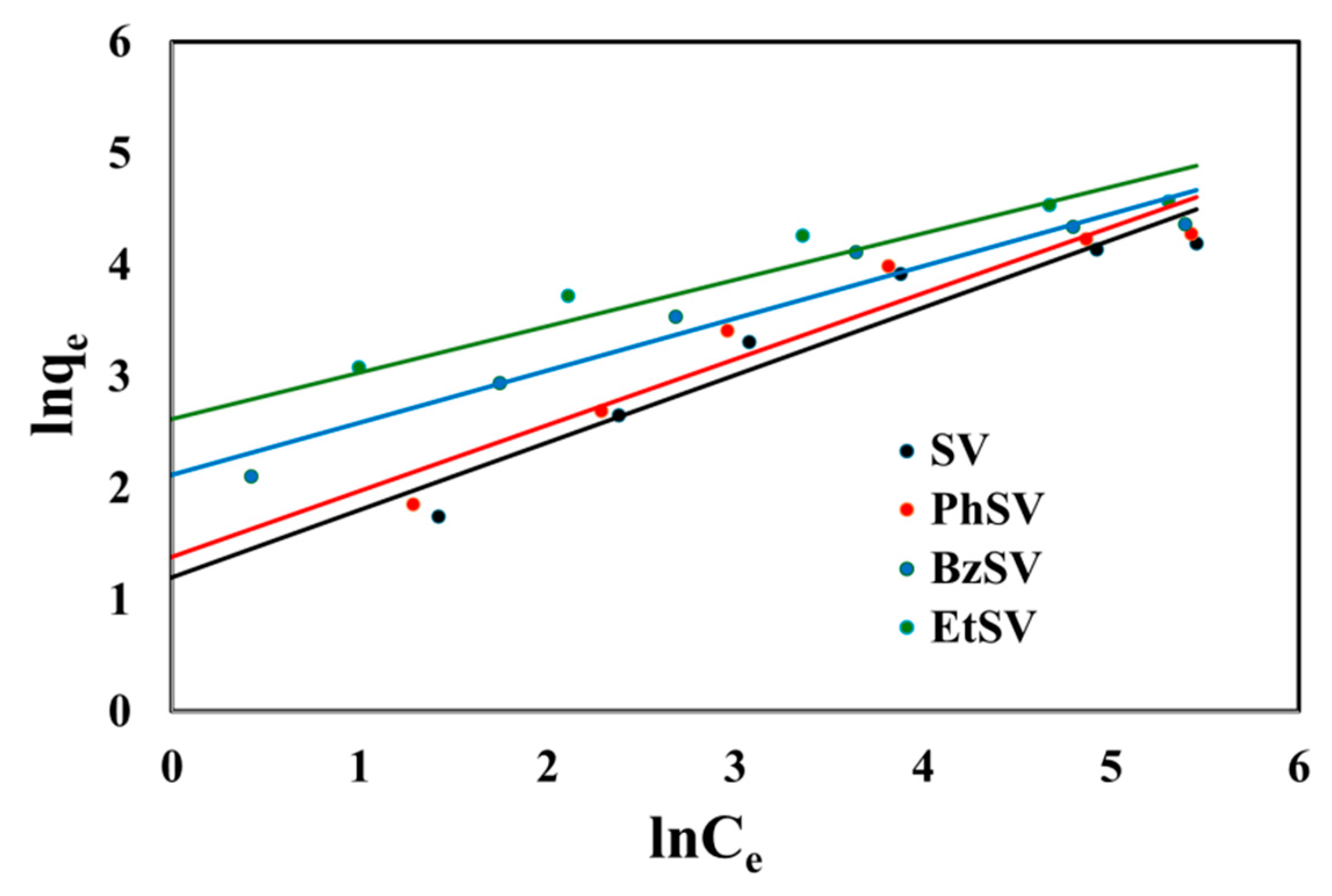

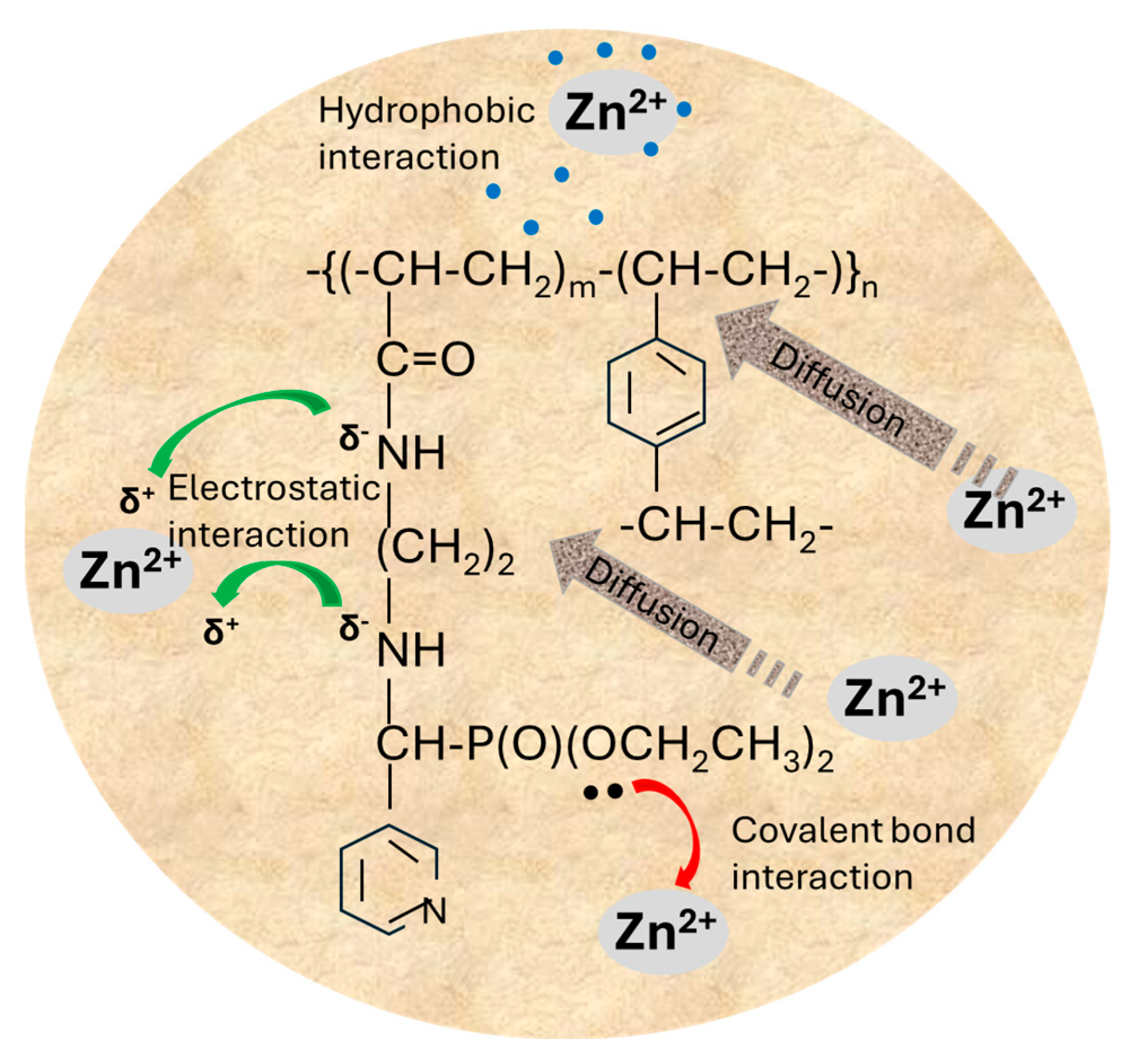

2.2.2. Equilibrium Studies

2.2.3. Influence of the Nature of Polymeric Supports on Their Adsorptive Properties

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials

3.2. Equipments

3.3. Preparation of Pure SV Copolymer with Primary Amine Groups

3.4. Functionalization of Amino Groups in AN-DVB Copolymers with Aminophosphonate Groups

3.5. Adsorption of Zinc Ions

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rashid, R.; Shafiq, I.; Akhter, P.; Iqbal, M.J.; Hussain, M. A state-of-the-art review on wastewater treatment techniques: The effectiveness of adsorption method. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 9050–9066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, K.H.H.; Mustafa, F.S.; Omer, K.M.; Hama, S.; Hamarawf, R.F.; Rahman, K.O. Heavy metal pollution in the aquatic environment: Efficient and low-cost removal approaches to eliminate their toxicity: A review. RSC Adv. 2023, 13, 17595–17610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raji, Z.; Karim, A.; Karam, A.; Khalloufi, S. Adsorption of heavy metals: Mechanisms, kinetics, and applications of various adsorbents in wastewater remediation—A review. Waste 2023, 1, 775–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karim, A.; Raji, Z.; Karam, A.; Khalloufi, S. Valorization of fibrous plant-based food waste as biosorbents for remediation of heavy metals from wastewater—A review. Molecules 2023, 28, 4205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azimi, A.; Azari, A.; Rezakazemi, M.; Ansarpour, M. Removal of heavy metals from industrial wastewaters: A review. ChemBioEng Rev. 2017, 4, 37–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alengebawy, A.; Abdelkhalek, S.T.; Qureshi, S.R.; Wang, M.-Q. Heavy metals and pesticides toxicity in agricultural soil and plants: Ecological risks and human health implications. Toxics 2021, 9, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vecino, X.; Reig, M. Wastewater Treatment by Adsorption and/or Ion-Exchange Processes for Resource Recovery. Water 2022, 14, 911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamshaid, A.; Hamid, A.; Muhammad, N.; Naseer, A.; Ghauri, M.; Iqbal, J.; Rafiq, S.; Shah, N.S. Cellulose-based materials for the removal of heavy metals from wastewater—An overview. ChemBioEng Rev. 2017, 4, 240–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duranoğlu, D.; Trochimczuk, A.W.; Beker, Ü. A comparison study of peach stone and acrylonitrile-divinylbenzene copolymer based activated carbons as chromium(VI) sorbents. Chem. Eng. J. 2010, 165, 56–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duranoğlu, D.; Trochimczuk, A.W.; Beker, U. Kinetics and thermodynamics of hexavalent chromium adsorption onto activated carbon derived from acrylonitrile-divinylbenzene copolymer. Chem. Eng. J. 2012, 187, 193–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carolin, C.F.; Kumar, P.S.; Saravanan, A.; Joshiba, G.J.; Naushad, M. Efficient techniques for the removal of toxic heavy metals from aquatic environment: A review. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2017, 5, 2782–2799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otero, M.; Coimbra, R.N. Polymeric materials for wastewater treatment applications. Polymers 2025, 17, 552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkhaldi, H.; Alharthi, S.; Alharthi, S.; AlGhamdi, H.A.; AlZahrani, Y.M.; Mahmoud, S.A.; Amin, L.G.; Al-Shaalan, N.H.; Boraie, W.E.; Attia, M.S.; et al. Sustainable polymeric adsorbents for adsorption-based water remediation and pathogen deactivation: A review. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 33143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, S.; Kim, J.-H.; Yang, K.S.; Chang, M. Facile preparation of amino-functionalized polymeric microcapsules as efficient adsorbent for heavy metal ions removal. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 425, 130645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dragan, E.S.; Avram, E.; Axente, D.; Marcu, C. Ion-exchange resins. III. Functionalization–morphology correlations in the synthesis of some macroporous, strong basic anion exchangers and uranium-sorption properties evaluation. J. Polym. Sci. Part A Polym. Chem. 2004, 42, 2451–2461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dragan, E.S.; Humelnicu, D.; Dinu, M.V. Design of porous strong base anion exchangers bearing N,N-dialkyl 2-hydroxyethyl ammonium groups with enhanced retention of Cr(VI) ions from aqueous solution. React. Funct. Polym. 2018, 124, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Nie, Y.; Wang, B. Simulation Study on the Relationship between the Crosslinking Degree and Structure, Hydrophobic Behavior for Poly(styrene-co-divinylbenzene) Copolymer. J. Mol. Struct. 2018, 1173, 120–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nichita, I.; Lupa, L.; Stoia, M.; Dragan, E.S.; Popa, A. Aminophosphonic groups grafted onto the structure of macroporous styrene–divinylbenzene copolymer: Preparation and studies on the antimicrobial effect. Polym. Bull. 2019, 76, 4539–4557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexandratos, S.D.; Zhu, X. ATR-FTIR Spectroscopy as a Probe for Metal Ion Binding onto Immobilized Ligands. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2018, 218, 196–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, R.; He, X.; Zhu, C.; Tao, L. Recent developments in functional polymers via the Kabachnik–Fields reaction: The state of the art. Molecules 2024, 29, 727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nichita, I.; Lupa, L.; Visa, A.; Dragan, E.S.; Dinu, M.V.; Popa, A. Chemical modification of acrylonitrile-divinylbenzene polymer supports with aminophosphonate groups and their antibacterial activity testing. Molecules 2024, 29, 6054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Salih, K.A.M.; Hamza, M.F.; Fujita, T.; Rodríguez-Castellón, E.; Guibal, E. Synthesis of a New Phosphonate-Based Sorbent and Characterization of Its Interactions with Lanthanum (III) and Terbium (III). Polymers 2021, 13, 1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popa, A.; Ilia, G.; Iliescu, S.; Plesu, N.; Ene, R.; Parvulescu, V. Styrene-co-divinylbenzene/silica hybrid supports for immobilization of transitional metals and their application in catalysis. Polym. Bull. 2019, 76, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legan, M.; Trochimczuk, A.W. Bis-Imidazolium Type Ion-Exchange Resin with Poly(HIPE) Structure for the Selective Separation of Anions from Aqueous Solutions. Sep. Sci. Technol. 2018, 53, 1163–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalifa, R.E.; Omer, A.M.; Tamer, T.M.; Salem, W.M.; Mohy Eldin, M.S. Removal of Methylene Blue Dye from Synthetic Aqueous Solutions Using Novel Phosphonate Cellulose Acetate Membranes: Adsorption Kinetic, Equilibrium, and Thermodynamic Studies. Desalination Water Treat. 2019, 144, 272–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Głowińska, A.; Trochimczuk, A.W. Polymer-supported phosphoric, phosphonic and phosphinic acids—From synthesis to properties and applications in separation processes. Molecules 2020, 25, 4236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkins, C.L. Molecular anchors for self-assembled monolayers on ZnO: A direct comparison of the thiol and phosphonic acid moieties. J. Phys. Chem. C 2009, 113, 18276–18286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, A.K.; Mandal, S.N.; Das, S.K. Adsorption of Zn(II) from Aqueous Solution by Using Different Adsorbents. Chem. Eng. J. 2006, 123, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousavi, S.J.; Parvini, M.; Ghorbani, M. Experimental Design Data for the Zinc Ions Adsorption Based on Mesoporous Modified Chitosan Using Central Composite Design Method. Carbohydr. Polym. 2018, 188, 197–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burham, N.; Sayed, M. Adsorption Behavior of Cd2+ and Zn2+ onto Natural Egyptian Bentonitic Clay. Minerals 2016, 6, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Wang, H.; Cao, Y. Pb(II) Sorption by Biochar Derived from Cinnamomum camphora and Its Improvement with Ultrasound-Assisted Alkali Activation. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2018, 556, 177–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, J.; Wang, H.; Wang, C. Adsorption of Toxic Zinc by Functionalized Lignocellulose Derived from Waste Biomass: Kinetics, Isotherms and Thermodynamics. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Guo, W.; Ji, Z.; Liu, Y.; Hu, X.; Liu, Z. Static and Dynamic Sorption Study of Heavy Metal Ions on Amino-Functionalized SBA-15. J. Dispers. Sci. Technol. 2018, 39, 594–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, T.; Qiao, X.; Lu, X.; Fan, X. Selective Adsorption of Zn2+ on Surface Ion-Imprinted Polymer. Desalination Water Treat. 2016, 57, 15455–15466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Element/ Sample | Wt.% | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SV | PhSV | BzSV | EtSV | |

| C | 67.70 | 68.43 | 68.0 | 69.0 |

| N | 21.0 | 16.13 | 17.70 | 19.6 |

| O | 11.30 | 10.73 | 13.0 | 10.2 |

| P | - | 4.71 | 1.3 | 1.2 |

| Adsorbent Material | qe, exp, mg/g | PFO Kinetic Model | PSO Kinetic Model | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| qe, calc, mg/g | k1, min−1 | R2 | qe, Calc, mg/g | k2, min−1 (mg/g)−1 | R2 | ||

| SV | 28.9 | 22.7 | 0.0271 | 0.9334 | 34.5 | 0.00136 | 0.9931 |

| PhSV | 31.2 | 20.4 | 0.0297 | 0.8848 | 34.9 | 0.00211 | 0.9907 |

| BzSV | 36.3 | 24.9 | 0.0311 | 0.9639 | 40.2 | 0.00195 | 0.9905 |

| EtSV | 42.3 | 24.1 | 0.0322 | 0.9095 | 45.9 | 0.00222 | 0.9933 |

| Adsorbent Material | qm, exp mg/g | Langmuir Isotherm | Freundlich Isotherm | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KL L/mg | qm, calc mg/g | R2 | KF mg/g | 1/n | R2 | ||

| SV | 66.6 | 0.0228 | 80.6 | 0.9903 | 3.32 | 0.6053 | 0.9169 |

| PhSV | 72.3 | 0.0003 | 86.2 | 0.9915 | 3.98 | 0.5913 | 0.9170 |

| BzSV | 79.2 | 0.0572 | 86.2 | 0.9984 | 8.36 | 0.4665 | 0.9427 |

| EtSV | 96.5 | 0.1002 | 101 | 0.9995 | 13.7 | 0.4163 | 0.9408 |

| Adsorbent. | qm, mg/g | T, K | t, min | pH | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fe2O3@SBA-15-CS-AEAPTMS | 102.6 | 298 | 60 | 6 | [29] |

| Na-Bentonite | 9.45 | 299 | 60 | 6.5 | [30] |

| Spirodela polyrhiza | 28.5 | 303 | 120 | 6 | [31] |

| CC | 46.49 | 303 | 30 | 6 | [32] |

| SBA-15-NN | 52.3 | 298 | 40 | 5 | [33] |

| ion-imprinted polymer | 21.61 | 200 | 298 | 6 | [34] |

| EtSV | 101 | 60 | 298 | 6 | This work |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lupa, L.; Visa, A.; Popa, A.; Dinu, M.V.; Fringu, I.; Dragan, E.S. Adsorption of Zinc Ions from Aqueous Solutions on Polymeric Sorbents Based on Acrylonitrile-Divinylbenzene Networks Bearing Aminophosphonate Groups. Molecules 2025, 30, 4805. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244805

Lupa L, Visa A, Popa A, Dinu MV, Fringu I, Dragan ES. Adsorption of Zinc Ions from Aqueous Solutions on Polymeric Sorbents Based on Acrylonitrile-Divinylbenzene Networks Bearing Aminophosphonate Groups. Molecules. 2025; 30(24):4805. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244805

Chicago/Turabian StyleLupa, Lavinia, Aurelia Visa, Adriana Popa, Maria Valentina Dinu, Ionela Fringu, and Ecaterina Stela Dragan. 2025. "Adsorption of Zinc Ions from Aqueous Solutions on Polymeric Sorbents Based on Acrylonitrile-Divinylbenzene Networks Bearing Aminophosphonate Groups" Molecules 30, no. 24: 4805. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244805

APA StyleLupa, L., Visa, A., Popa, A., Dinu, M. V., Fringu, I., & Dragan, E. S. (2025). Adsorption of Zinc Ions from Aqueous Solutions on Polymeric Sorbents Based on Acrylonitrile-Divinylbenzene Networks Bearing Aminophosphonate Groups. Molecules, 30(24), 4805. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244805