Chemical Composition and Free Radical Content During Saharan Dust Episode in SE Poland

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

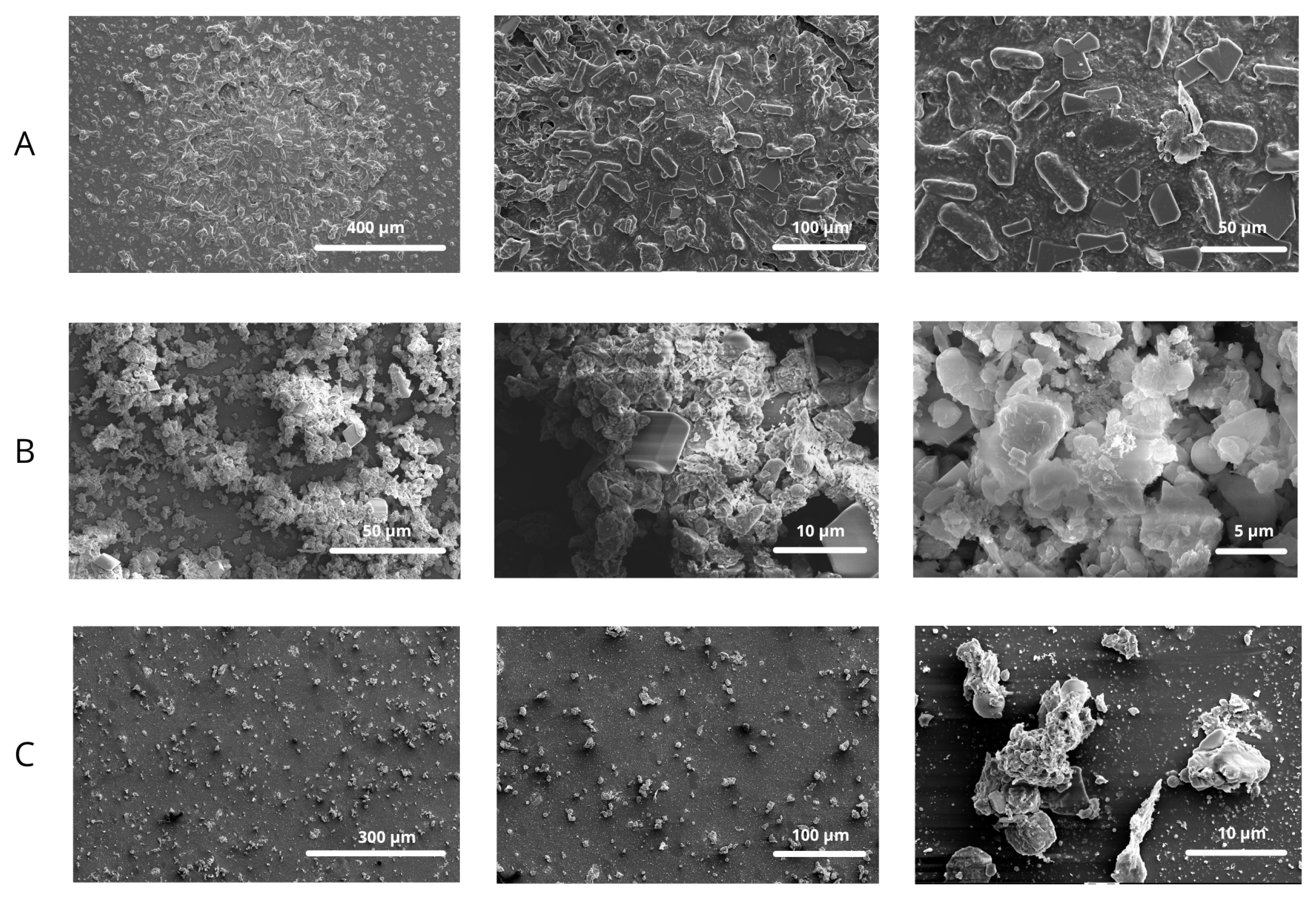

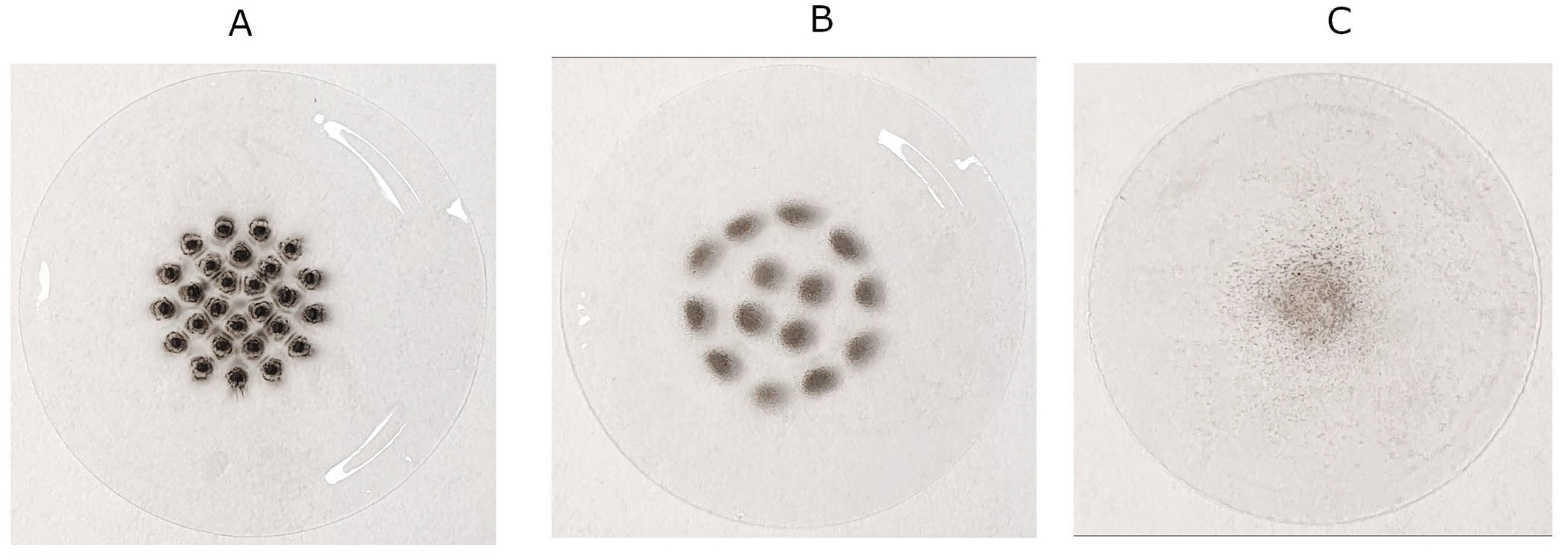

2.1. Structural Properties

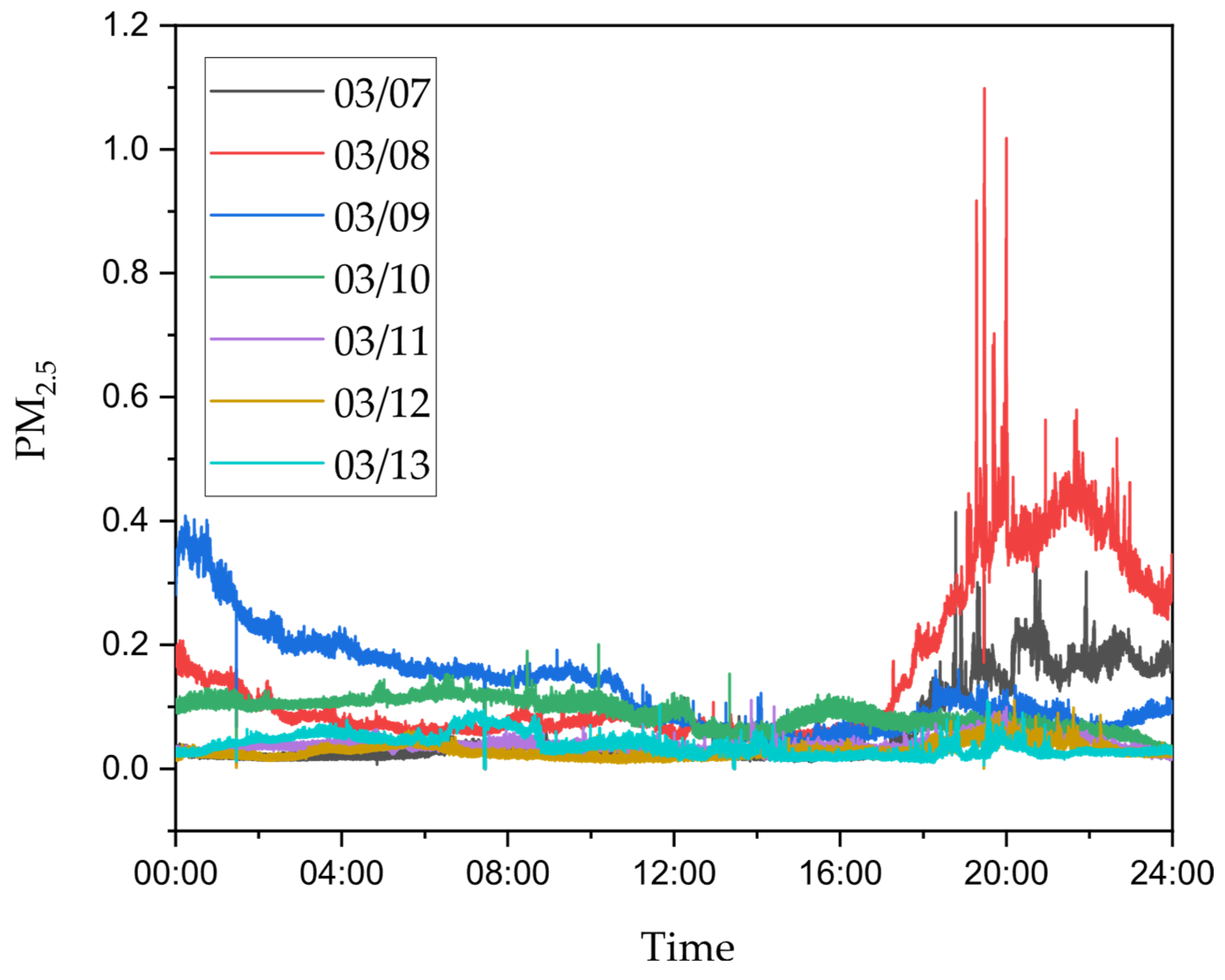

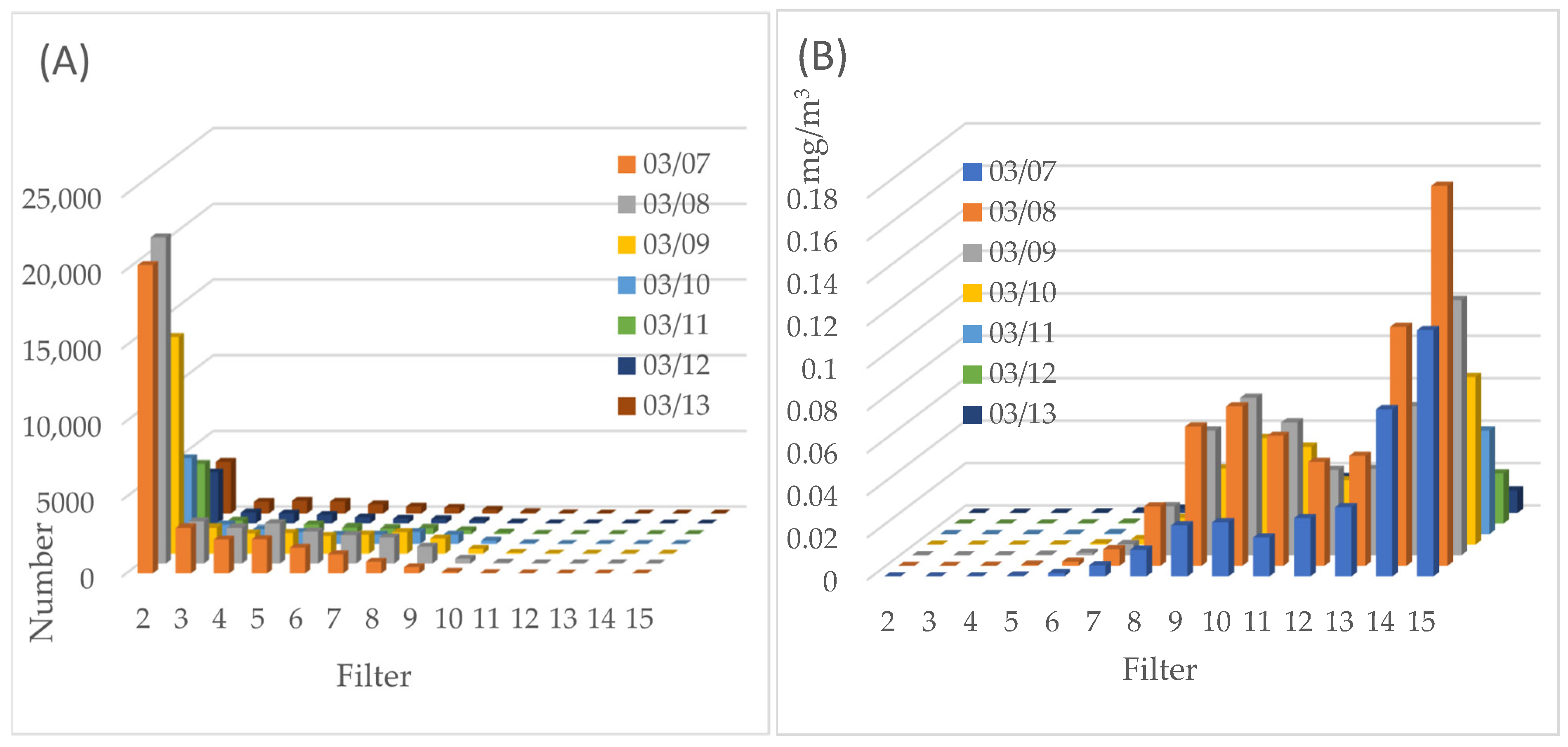

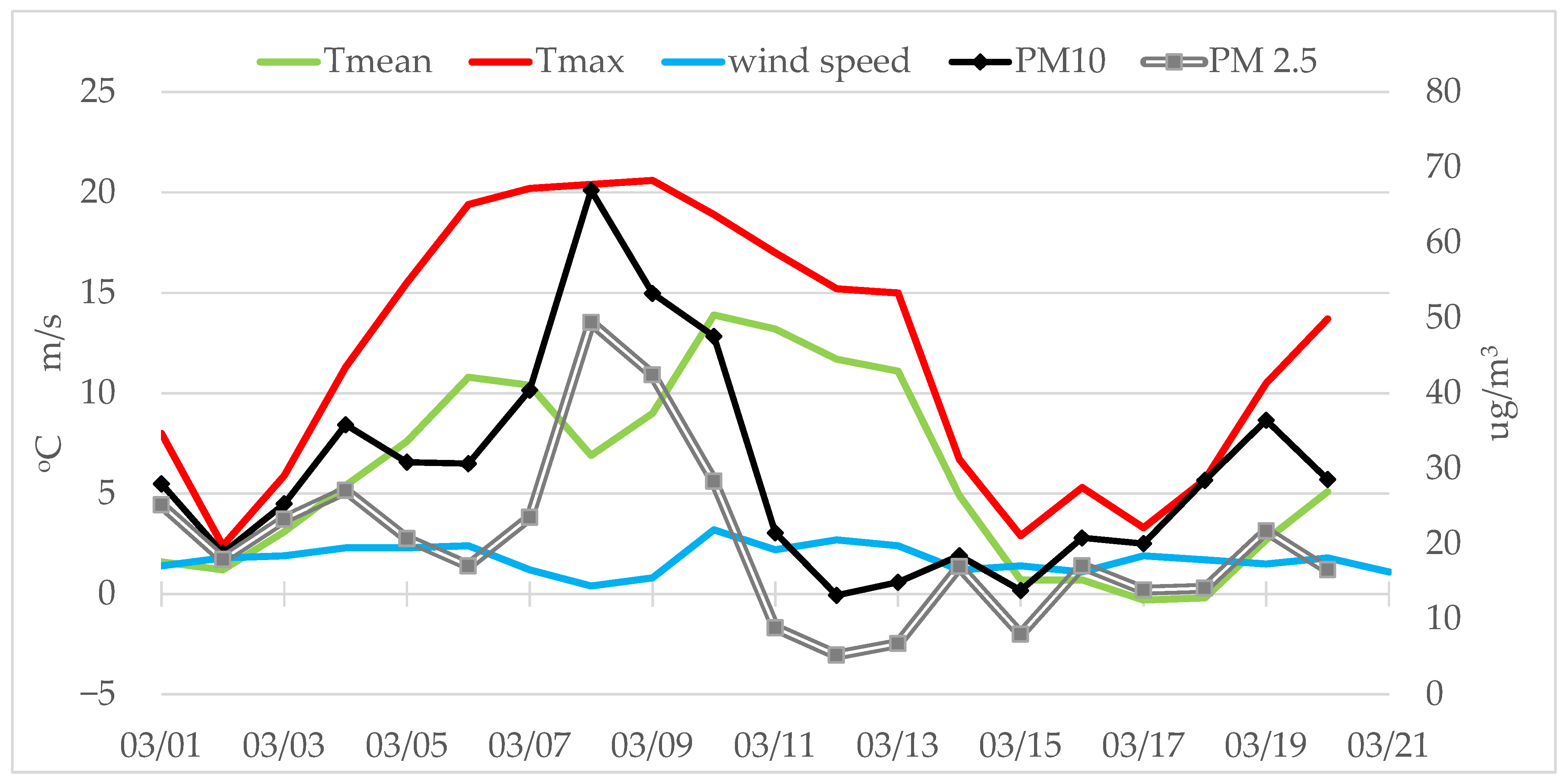

2.2. Dekati Measurements

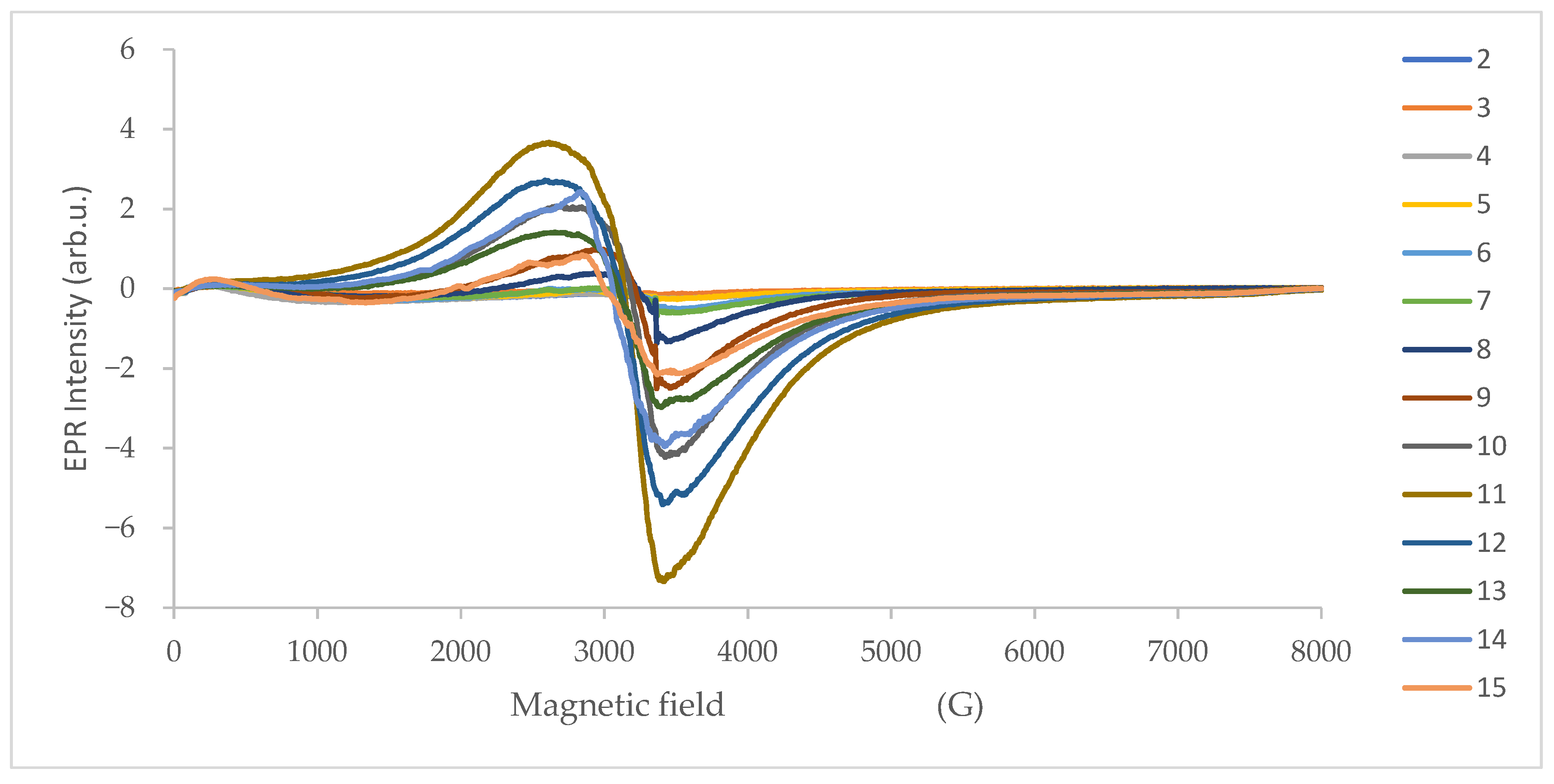

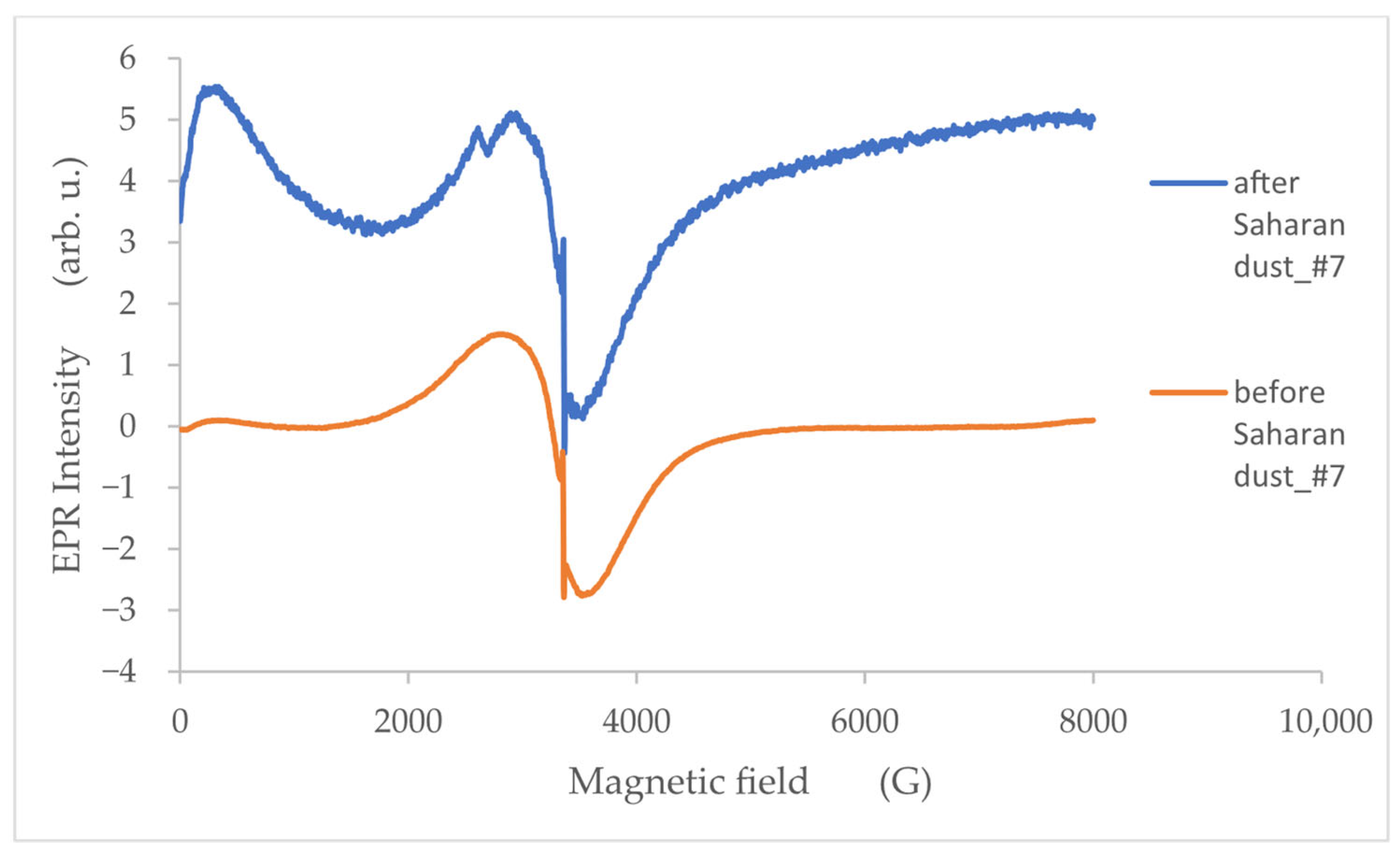

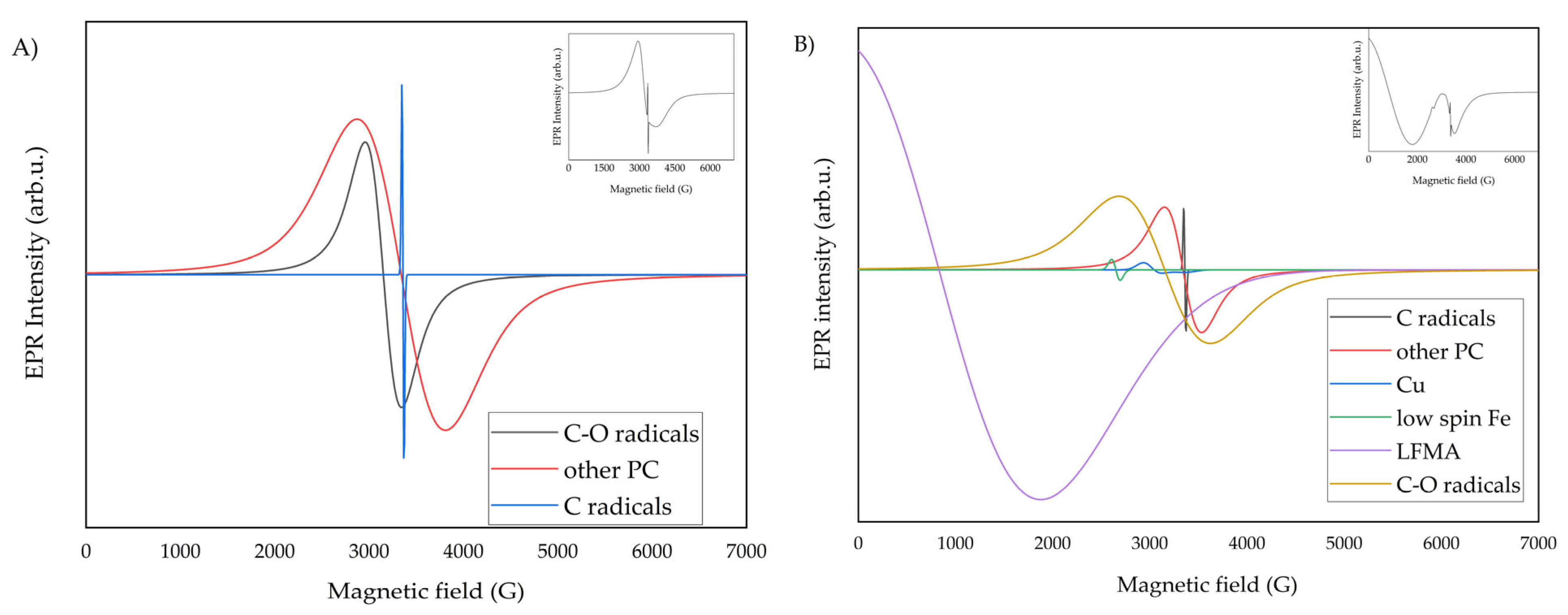

2.3. EPR Spectroscopy

3. Materials and Methods

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Juda-Rezler, K.; Reizer, M.; Oudinet, J.P. Determination and Analysis of PM10 Source Apportionment during Episodes of Air Pollution in Central Eastern European Urban Areas: The Case of Wintertime 2006. Atmos Environ. 2011, 45, 6557–6566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyły Drobne w Atmosferze. Kompendium Wiedzy o Zanieczyszczeniu Powietrza Pyłem Zawieszonym w Polsce; Juda-Rezler, K., Toczko, B., Eds.; Biblioteka Monitoringu Środowiska: Warszawa, Poland, 2016; ISBN 978-83-61227-73-1. [Google Scholar]

- Putaud, J.-P.; Van Dingenen, R.; Alastuey, A.; Bauer, H.; Birmili, W.; Cyrys, J.; Flentje, H.; Fuzzi, S.; Gehrig, R.; Hansson, H.C.; et al. A European Aerosol Phenomenology–3: Physical and Chemical Characteristics of Particulate Matter from 60 Rural, Urban, and Kerbside Sites across Europe. Atmos. Environ. 2010, 44, 1308–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishikawa, M.; Matsui, I.; Batdorj, D.; Jugder, D.; Mori, I.; Shimizu, A.; Sugimoto, N.; Takahashi, K. Chemical Composition of Urban Airborne Particulate Matter in Ulaanbaatar. Atmos. Environ. 2011, 45, 5710–5715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sówka, I.; Chlebowska-Stys, A.; Pachurka, Ł.; Rogula-Kozłowska, W.; Mathews, B. Analysis of Particulate Matter Concentration Variability and Origin in Selected Urban Areas in Poland. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varga, G. Changing Nature of Saharan Dust Deposition in the Carpathian Basin (Central Europe): 40 Years of Identified North African Dust Events (1979–2018). Environ. Int. 2020, 139, 105712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varga, G.; Meinander, O.; Rostási, Á.; Dagsson-Waldhauserova, P.; Csávics, A.; Gresina, F. Saharan, Aral-Caspian and Middle East Dust Travels to Finland (1980–2022). Environ. Int. 2023, 180, 108243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varga, G.; Rostási, Á.; Meiramova, A.; Dagsson-Waldhauserová, P.; Gresina, F. Increasing Frequency and Changing Nature of Saharan Dust Storm Events in the Carpathian Basin (2019–2023)—The New Normal? Hung. Geogr. Bull. 2023, 72, 319–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczepanik, D.M.; Ortiz-Amezcua, P.; Heese, B.; D’Amico, G.; Stachlewska, I.S. First Ever Observations of Mineral Dust in Wintertime over Warsaw, Poland. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 3788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Gu, J.; Wang, X. The Impact of Sahara Dust on Air Quality and Public Health in European Countries. Atmos. Environ. 2020, 241, 117771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansmann, A.; Bösenberg, J.; Chaikovsky, A.; Comerón, A.; Eckhardt, S.; Eixmann, R.; Freudenthaler, V.; Ginoux, P.; Komguem, L.; Linné, H.; et al. Long-range Transport of Saharan Dust to Northern Europe: The 11–16 October 2001 Outbreak Observed with EARLINET. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2003, 108, 4783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papayannis, A.; Amiridis, V.; Mona, L.; Tsaknakis, G.; Balis, D.; Bösenberg, J.; Chaikovski, A.; De Tomasi, F.; Grigorov, I.; Mattis, I.; et al. Systematic Lidar Observations of Saharan Dust over Europe in the Frame of EARLINET (2000–2002). J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2008, 113, D10204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janicka, L.; Stachlewska, I.S.; Veselovskii, I.; Baars, H. Temporal Variations in Optical and Microphysical Properties of Mineral Dust and Biomass Burning Aerosol Derived from Daytime Raman Lidar Observations over Warsaw, Poland. Atmos. Environ. 2017, 169, 162–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szuszkiewicz, M.M.; Łukasik, A.; Petrovský, E.; Grison, H.; Błońska, E.; Lasota, J.; Szuszkiewicz, M. Magneto-Chemical Characterisation of Saharan Dust Deposited on Snow in Poland. Environ. Res. 2023, 216, 114605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remoundaki, E.; Bourliva, A.; Kokkalis, P.; Mamouri, R.E.; Papayannis, A.; Grigoratos, T.; Samara, C.; Tsezos, M. PM10 Composition during an Intense Saharan Dust Transport Event over Athens (Greece). Sci. Total Environ. 2011, 409, 4361–4372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szoboszlai, Z.; Kertész, Z.; Szikszai, Z.; Borbély-Kiss, I.; Koltay, E. Ion Beam Microanalysis of Individual Aerosol Particles Originating from Saharan Dust Episodes Observed in Debrecen, Hungary. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. B 2009, 267, 2241–2244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatzikonstantinou, N.; Mertzimekis, T.J.; Godelitsas, A.; Gamaletsos, P.; Nastos, P.; Goettlicher, J.; Steininger, R. Using Synchrotron Radiation to Study Iron Phases in Saharan Dust Samples from Athens Skies. HNPS Proc. 2019, 21, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Middleton, N.; Yiallouros, P.; Kleanthous, S.; Kolokotroni, O.; Schwartz, J.; Dockery, D.W.; Demokritou, P.; Koutrakis, P. A 10-Year Time-Series Analysis of Respiratory and Cardiovascular Morbidity in Nicosia, Cyprus: The Effect of Short-Term Changes in Air Pollution and Dust Storms. Environ. Health 2008, 7, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, L.; Tobias, A.; Querol, X.; Küzli, N.; Pey, J.; Alastuey, A.; Viana, M.; Valero, N.; González-Cabré, M.; Sunyer, J. Coarse Particles from Saharan Dust and Daily Mortality. Epidemiology 2008, 19, 800–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bredeck, G.; Dobner, J.; Rossi, A.; Schins, R.P.F. Saharan Dust Induces the Lung Disease-Related Cytokines Granulocyte–Macrophage Colony-Stimulating Factor and Granulocyte Colony-Stimulating Factor. Environ. Int. 2024, 186, 108580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Yousaf, M.; Xu, J.; Ma, X. Ultrafine Particles: Sources, Toxicity, and Deposition Dynamics in the Human Respiratory Tract—Experimental and Computational Approaches. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 376, 124458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyana, T.J.; Lomnicki, S.M.; Guo, C.; Cormier, S.A. A Scalable Field Study Protocol and Rationale for Passive Ambient Air Sampling: A Spatial Phytosampling for Leaf Data Collection. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017, 51, 10663–10673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vejerano, E.P.; Rao, G.; Khachatryan, L.; Cormier, S.A.; Lomnicki, S. Environmentally Persistent Free Radicals: Insights on a New Class of Pollutants. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018, 52, 2468–2481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, B.; Li, H.; Lang, D.; Xing, B. Environmentally Persistent Free Radicals: Occurrence, Formation Mechanisms and Implications. Environ. Pollut. 2019, 248, 320–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stefaniuk, I.; Cieniek, B.; Ćwik, A.; Kluska, K.; Kasprzyk, I. Tracking Long-Lived Free Radicals in Dandelion Caused by Air Pollution Using Electron Paramagnetic Resonance Spectroscopy. Molecules 2024, 29, 5173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- An, J.; Liu, H.; Wang, X.; Talifu, D.; Abulizi, A.; Maihemuti, M.; Li, K.; Bai, H.; Luo, P.; Xie, X. Oxidative Potential of Size-Segregated Particulate Matter in the Dust-Storm Impacted Hotan, Northwest China. Atmos. Environ. 2022, 280, 119142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varrica, D.; Alaimo, M.G. Influence of Saharan Dust on the Composition of Urban Aerosols in Palermo City (Italy). Atmosphere 2024, 15, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, L.; Yang, L.; Liu, L.; Tong, S.; Liu, Q.; Li, G.; Zhang, H.; Zhu, W.Y.; Liu, G.; Zheng, M.; et al. Oxidative Potential and Persistent Free Radicals in Dust Storm Particles and Their Associations with Hospitalization. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 10827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goudie, A.S. Desert Dust and Human Health Disorders. Environ. Int. 2014, 63, 101–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariam; Joshi, M.; Khan, A.; Sapra, B.K. Improving the Accuracy of Charge Size Distribution Measurement Using Electrical Low Pressure Impactor. Part. Sci. Technol. 2022, 40, 290–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamminen, E. Accurate Measurement of Nanoparticle Charge, Number and Size with the ELPI+ TM Instrument. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2011, 304, 012064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaral, S.; De Carvalho, J.; Costa, M.; Pinheiro, C. An Overview of Particulate Matter Measurement Instruments. Atmosphere 2015, 6, 1327–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczepanik, D.M.; Stachlewska, I.S.; Tetoni, E.; Althausen, D. Properties of Saharan Dust Versus Local Urban Dust—A Case Study. Earth Space Sci. 2021, 8, e2021EA001816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Górka, M.; Jędrysek, M.-O.; Lewicka-Szczebak, D.; Krajniak, J. Mineralogical and Oxygen Isotope Composition of Inorganic Dust-Fall in Wrocław (SW Poland) Urban Area–Test of a New Monitoring Tool. Geol. Q. 2011, 55, 71–80. [Google Scholar]

- Ainur, D.; Chen, Q.; Wang, Y.; Li, H.; Lin, H.; Ma, X.; Xu, X. Pollution Characteristics and Sources of Environmentally Persistent Free Radicals and Oxidation Potential in Fine Particulate Matter Related to City Lockdown (CLD) in Xi’an, China. Environ. Res. 2022, 210, 112899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, S.G.; Eberly, S.; Paatero, P.; Norris, G.A. Methods for Estimating Uncertainty in PMF Solutions: Examples with Ambient Air and Water Quality Data and Guidance on Reporting PMF Results. Sci. Total Environ. 2015, 518–519, 626–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paatero, P.; Eberly, S.; Brown, S.G.; Norris, G.A. Methods for Estimating Uncertainty in Factor Analytic Solutions. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 2014, 7, 781–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefaniuk, I.; Cieniek, B.; Kluska, K.; Brewka, J.; Ćwik, A.; Płoch, D.; Kasprzyk, I. Characteristics of Fractions of Air Pollution Particles of Different Sizes in the Range of 6 nm–10 μm in the Autumn Season in Rzeszów; Kluska, K., Ed.; Rzeszów University Press: Rzeszów, Poland, 2025; p. 11. [Google Scholar]

- Dubiel, Ł.; Cieniek, B.; Maziarz, W.; Stefaniuk, I. Electron Magnetic Resonance Study of Ni50.2Mn28.3Ga21.5 Powders. Materials 2024, 17, 4391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arangio, A.M.; Tong, H.; Socorro, J.; Pöschl, U.; Shiraiwa, M. Quantification of Environmentally Persistent Free Radicals and Reactive Oxygen Species in Atmospheric Aerosol Particles. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2016, 16, 13105–13119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaltout, A.A.; Boman, J.; Shehadeh, Z.F.; Al-Malawi, D.-A.R.; Hemeda, O.M.; Morsy, M.M. Spectroscopic Investigation of PM2.5 Collected at Industrial, Residential and Traffic Sites in Taif, Saudi Arabia. J. Aerosol Sci. 2015, 79, 97–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, A.L.N.D.; Cook, R.L.; Lomnicki, S.M.; Dellinger, B. Effect of Low Temperature Thermal Treatment on Soils Contaminated with Pentachlorophenol and Environmentally Persistent Free Radicals. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2012, 46, 5971–5978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Blackburn. In Recommendations for and Documentation of Biological Values for Use in Risk Assessment; U.S. Environmental Protection Agency: Washington, DC, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Gehling, W.; Khachatryan, L.; Dellinger, B. Hydroxyl Radical Generation from Environmentally Persistent Free Radicals (EPFRs) in PM2.5. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014, 48, 4266–4272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gehling, W.; Dellinger, B. Environmentally Persistent Free Radicals and Their Lifetimes in PM 2.5. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013, 47, 8172–8178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoll, S.; Schweiger, A. EasySpin, a Comprehensive Software Package for Spectral Simulation and Analysis in EPR. J. Magn. Reson. 2006, 178, 42–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kubiak, T.; Krzyminiewski, R.; Dobosz, B. EPR Study of Paramagnetic Centers in Human Blood. Curr. Top. Biophys. 2013, 36, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Wójcik-Kanach, M.; Kasprzyk, I. Fungal Spore Calendar for the Warm Temperate Climate Zone. What Else besides Cladosporium Spores? Fungal Biol. 2025, 129, 101641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bank Danych Pomiarowych-GIOŚ. Available online: https://powietrze.gios.gov.pl/pjp/archives (accessed on 13 December 2025).

- Komunikat GIOŚ z dnia 7.03.2025 r. w Sprawie Aktualnej i Prognozowanej Jakości Powietrza w Polsce. Available online: https://powietrze.gios.gov.pl/pjp/content/show/1005683 (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- Virtanen, A.; Marjamäki, M.; Ristimäki, J.; Keskinen, J. Fine Particle Losses in Electrical Low-Pressure Impactor. J. Aerosol Sci. 2001, 32, 389–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saari, S.; Arffman, A.; Harra, J.; Rönkkö, T.; Keskinen, J. Performance Evaluation of the HR-ELPI + Inversion. Aerosol Sci. Technol. 2018, 52, 1037–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefaniuk, I. Electron Paramagnetic Resonance Study of Impurities and Point Defects in Oxide Crystals. Opto-Electron. Rev. 2018, 26, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| % Weight | C | N | O | Co | Na | Mg | Al | Si | S | Cl | K | Cu | Ca | Fe | Ti | Zn |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| filter #7 | 39.35 | 6.83 | 29.67 | 0.00 | 1.04 | 0.00 | 0.08 | 0.40 | 10.40 | 1.78 | 9.67 | 1.79 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| filter #12 | 12.65 | 2.99 | 28.71 | 0.85 | 3.27 | 1.91 | 6.14 | 17.42 | 2.00 | 3.90 | 1.60 | 0.00 | 8.69 | 9.49 | 0.39 | 0.00 |

| filter #14 | 21.23 | 0.00 | 21.89 | 0.12 | 5.81 | 0.93 | 4.43 | 14.00 | 1.22 | 9.06 | 1.05 | 1.35 | 13.19 | 3.29 | 0.12 | 1.35 |

| % atom | C | N | O | Co | Na | Mg | Al | Si | S | Cl | K | Cu | Ca | Fe | Ti | Zn |

| filter #7 | 51.88 | 7.76 | 29.39 | 0.00 | 0.71 | 0.00 | 0.05 | 0.22 | 5.35 | 0.79 | 3.40 | 0.44 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| filter #12 | 21.94 | 4.34 | 37.91 | 0.30 | 2.96 | 1.66 | 4.84 | 13.18 | 1.35 | 1.75 | 0.87 | 0.00 | 4.00 | 2.77 | 0.18 | 0.00 |

| filter #14 | 36.00 | 0.00 | 28.11 | 0.04 | 5.46 | 0.78 | 3.41 | 10.23 | 0.79 | 5.50 | 0.54 | 0.76 | 6.73 | 1.19 | 0.05 | 0.45 |

| Impactor | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 |

| D50% (µm) | 0.006 | 0.0153 | 0.0303 | 0.0544 | 0.0949 | 0.155 | 0.257 | 0.384 | 0.606 | 0.953 | 1.64 | 2.48 | 3.67 | 5.4 | 9.94 |

| Filter # | - | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 0 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cieniek, B.; Płoch, D.; Brewka, J.; Kluska, K.; Stefaniuk, I.; Kasprzyk, I. Chemical Composition and Free Radical Content During Saharan Dust Episode in SE Poland. Molecules 2025, 30, 4799. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244799

Cieniek B, Płoch D, Brewka J, Kluska K, Stefaniuk I, Kasprzyk I. Chemical Composition and Free Radical Content During Saharan Dust Episode in SE Poland. Molecules. 2025; 30(24):4799. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244799

Chicago/Turabian StyleCieniek, Bogumił, Dariusz Płoch, Julia Brewka, Katarzyna Kluska, Ireneusz Stefaniuk, and Idalia Kasprzyk. 2025. "Chemical Composition and Free Radical Content During Saharan Dust Episode in SE Poland" Molecules 30, no. 24: 4799. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244799

APA StyleCieniek, B., Płoch, D., Brewka, J., Kluska, K., Stefaniuk, I., & Kasprzyk, I. (2025). Chemical Composition and Free Radical Content During Saharan Dust Episode in SE Poland. Molecules, 30(24), 4799. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244799