Modulating the Bioavailability and Bioaccessibility of Polyphenolic Compounds and Enhancing Health-Promoting Properties Through the Addition of Herbal Extracts to a Functional Beverage

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Physicochemical Properties of Obtained Functional Beverages

2.2. Bioactive Compound Contents in the Functional Beverages

2.3. Bioaccessibility and Bioavailability of Polyphenolic Compounds in the Functional Beverages

2.4. Analysis of Health-Promoting Potential of the Obtained Products Using In Vitro Methods

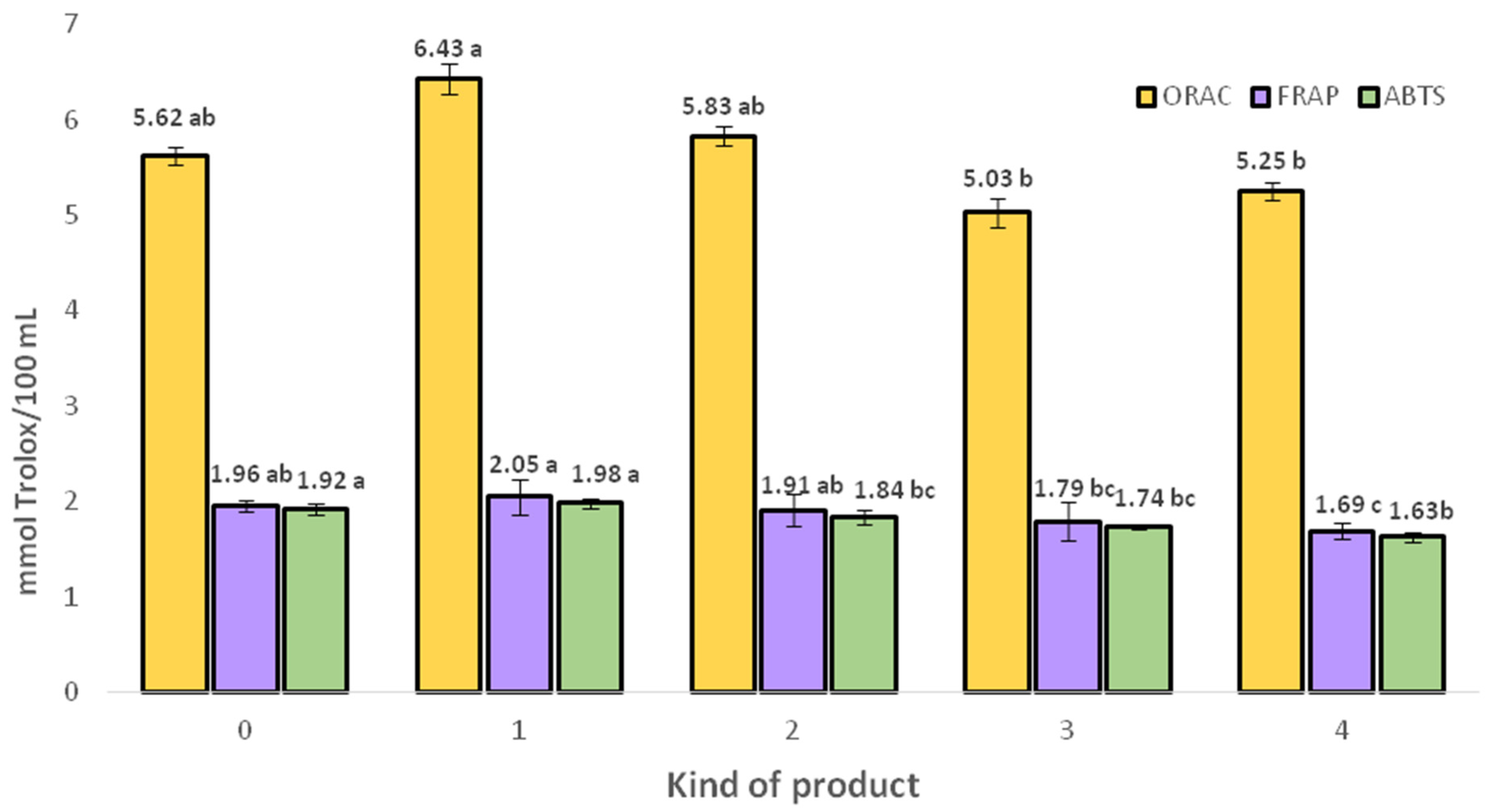

2.4.1. Antioxidant Activity of Analyzed Functional Beverages

2.4.2. Ability to Inhibit α-Amylase, α-Glucosidase, Pancreatic Lipase, and Lipoxygenase-15 of Functional Beverages

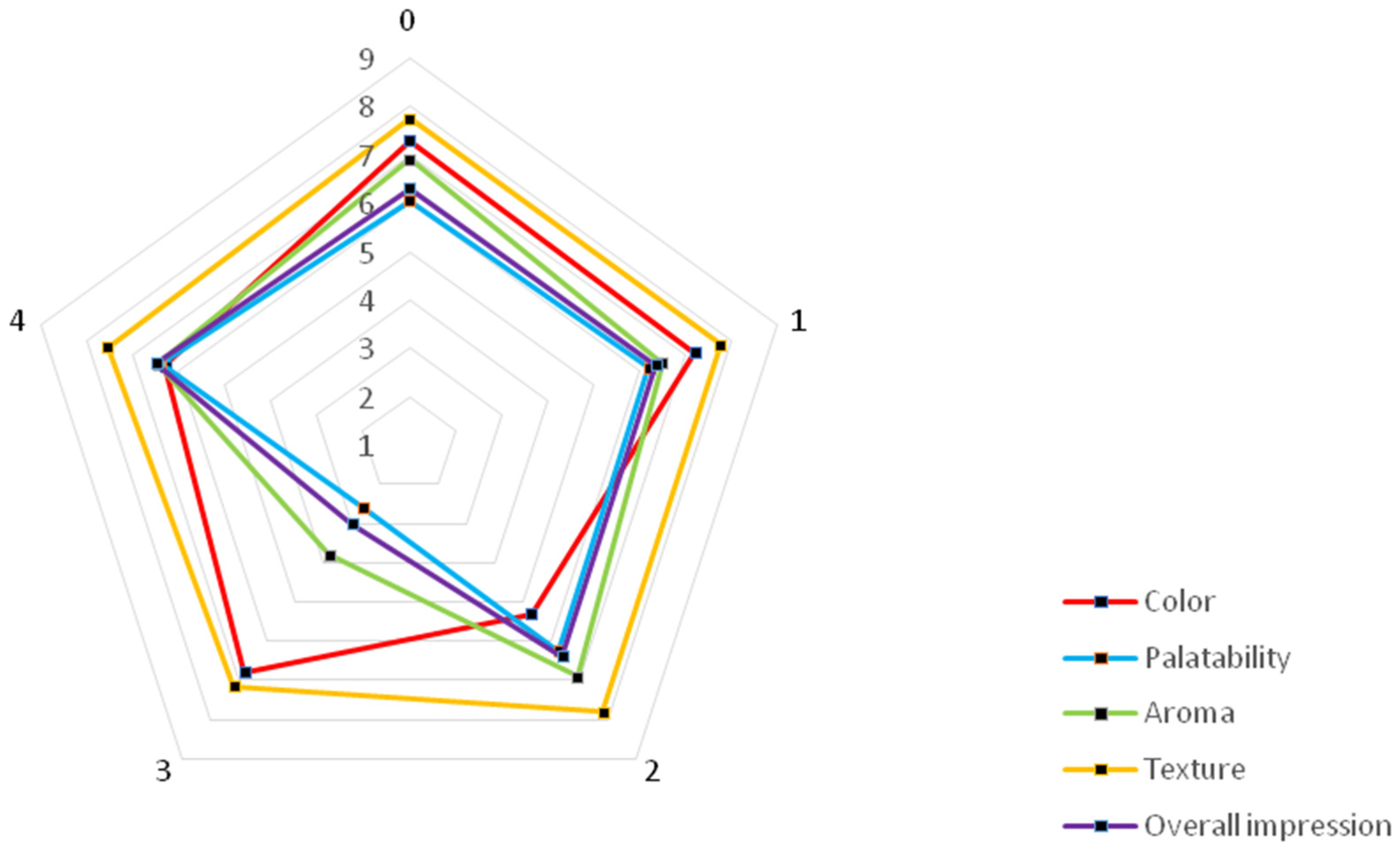

2.5. Sensory Evaluation of the Obtained Functional Beverages

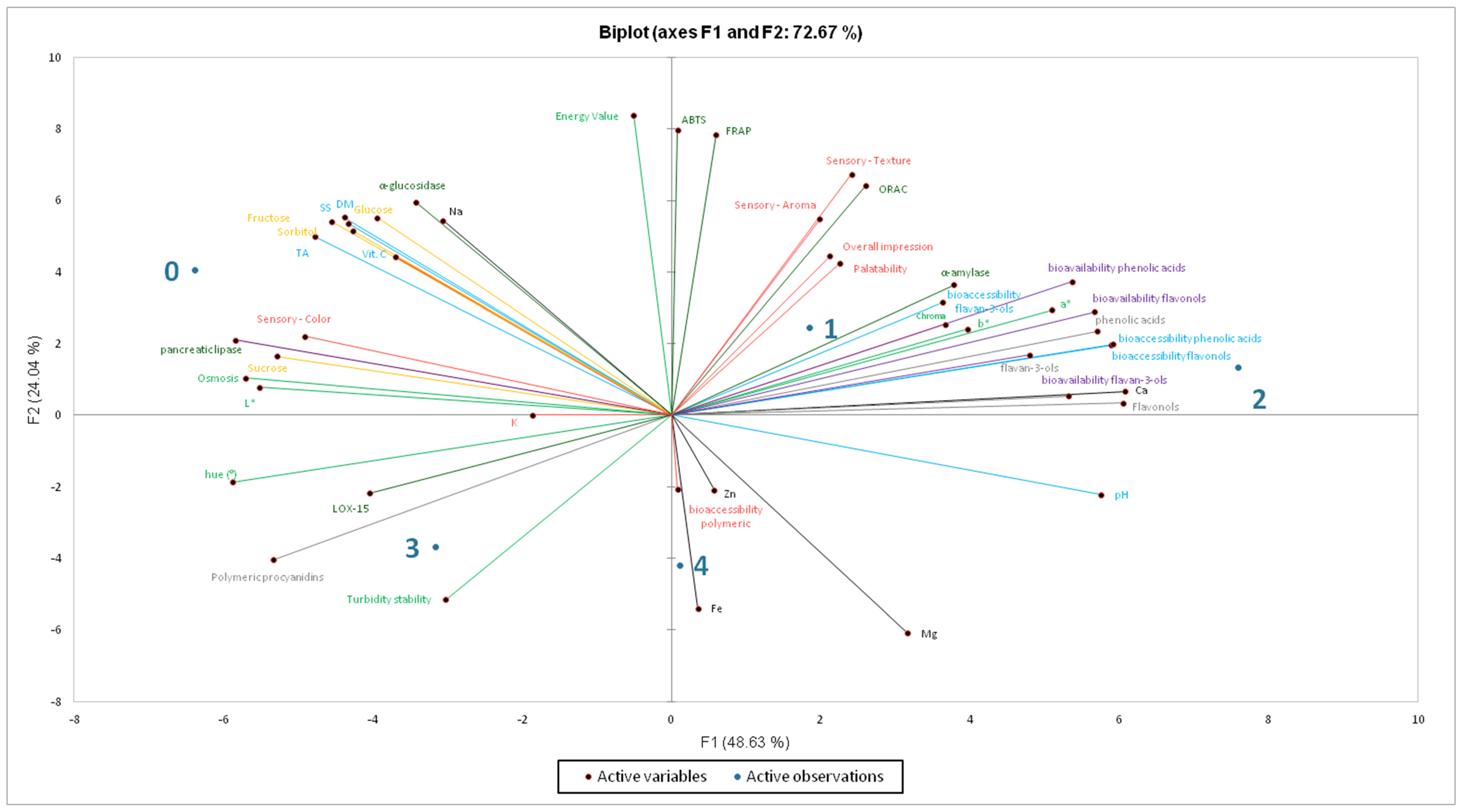

2.6. PCA

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Plant Material

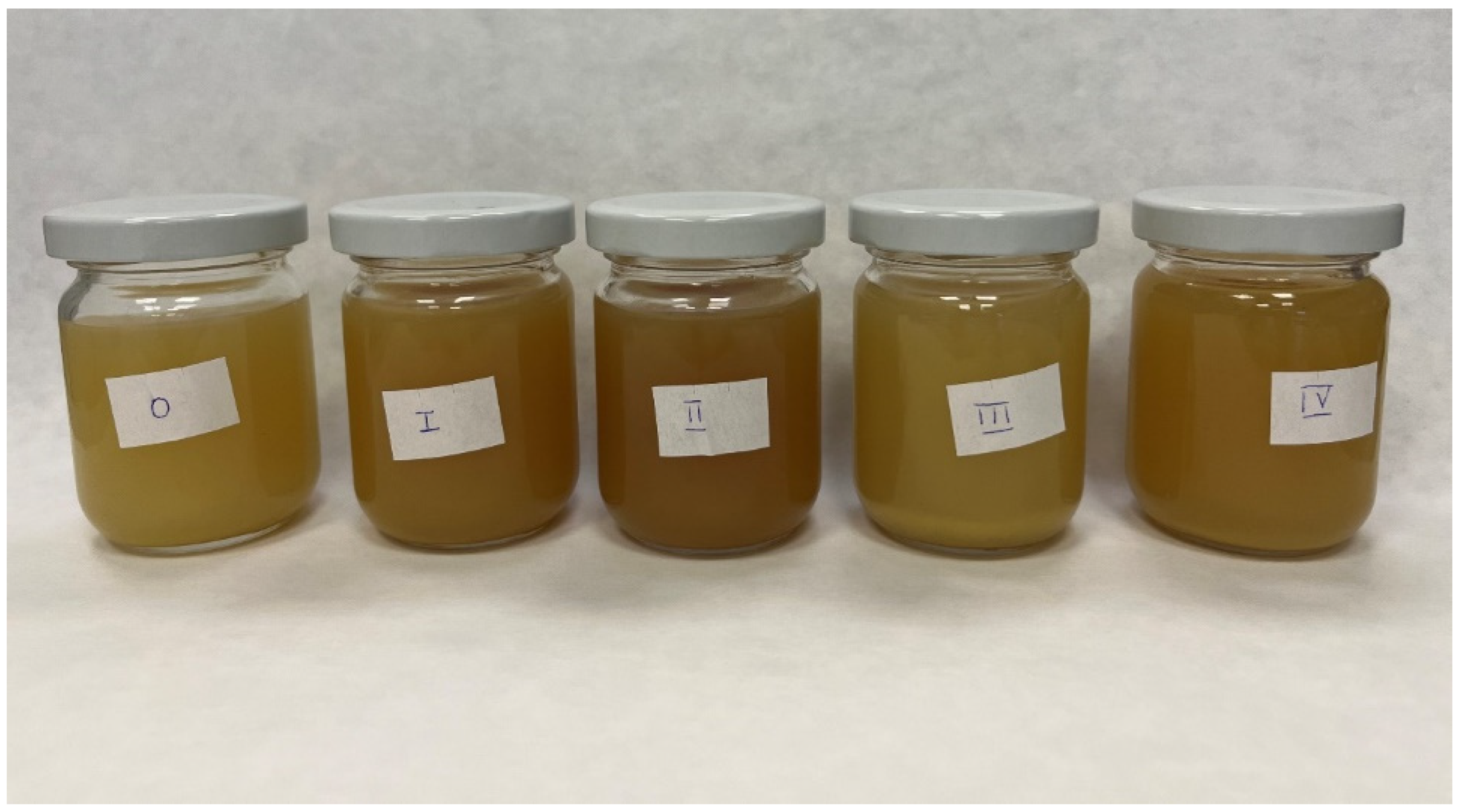

3.2. Herbal Shots Preparation

3.3. Physical Parameters

3.4. Calorific Value

3.5. Basic Chemical Composition

3.6. Determination of Sugar Content

3.7. Determination of Vitamin C

3.8. Determination of Mineral Content by Atomic AAS

3.9. Identification and Quantification of Polyphenolic Compounds, Including Polymers Procyanidins

3.10. Analysis of Bioaccessibility and Bioavailability

3.11. Analysis of Health-Promoting Potential Using In Vitro Methods

3.11.1. Antioxidant Activity

3.11.2. Ability to Inhibit α-Amylase and α-Glucosidase

3.11.3. Determination of Anti-Inflammatory Capacity by 15-Lipoxygenase (LOX-15) and Lipase Inhibitory Inhibition

3.12. Consumer Evaluation of the Herbal Shots

3.13. Statistical Analysis

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SD | standard deviation |

| AAS | atomic absorption spectrometry |

| UPLC-PDA-FL | ultra performance liquid chromatography with photodiode array and fluorescence detectors |

| IC50 | half maximal inhibitory concentration |

| ABTS | 2,2′-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) |

| FRAP | the ferric reducing ability of plasma |

| ORAC | the oxygen radical absorbance capacity |

| LOX-15 | 15-Lipoxygenase |

References

- Fardet, A.; Rock, E. Toward a New Philosophy of Preventive Nutrition: From a Reductionist to a Holistic Paradigm to Improve Nutritional Recommendations. Adv. Nutr. 2014, 5, 430–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srour, B.; Fezeu, L.K.; Kesse-Guyot, E.; Allès, B.; Méjean, C.; Andrianasolo, R.M.; Chazelas, E.; Deschasaux, M.; Hercberg, S.; Galan, P.; et al. Ultra-processed food intake and risk of cardiovascular disease: Prospective cohort study (NutriNet-Santé). BMJ 2019, 365, l1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Yuan, C.; Zhang, Y.; Abdelaty, N.S.; Chen, C.; Shen, J.; Zhang, L.; Lu, B.; Liu, R.; Li, P. Food inflammation index reveals the key inflammatory components in foods and heterogeneity within food groups: How do we choose food? J. Adv. Res. 2024, 74, 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandimali, N.; Bak, S.G.; Park, E.H.; Lim, H.-J.; Won, Y.-S.; Kim, E.-K.; Park, S.-I.; Lee, S.J. Free radicals and their impact on health and antioxidant defenses: A review. Cell Death Discov. 2025, 11, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miraj, S.; Rafieian, K.; Kiani, S. Melissa officinalis L.: A Review Study with an Antioxidant Prospective. J. Evid.-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2017, 22, 385–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Męczarska, K.; Cyboran-Mikołajczyk, S.; Solarska-Ściuk, K.; Oszmiański, J.; Siejak, K.; Bonarska-Kujawa, D. Protective Effect of Field Horsetail Polyphenolic Extract on Erythrocytes and Their Membranes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 3213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krawęcka, A.; Sobota, A.; Pankiewicz, U.; Zielińska, E.; Zarzycki, P. Stinging nettle (Urtica dioica L.) as a Functional Component in Durum Wheat Pasta Production: Impact on Chemical Composition, In Vitro Glycemic Index, and Quality Properties. Molecules 2021, 26, 6909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pavlešić, T.; Poljak, S.; Mišetić Ostojić, D.; Lučin, I.; Reynolds, C.A.; Kalafatovic, D.; Saftić Martinović, L. Mint (Mentha spp.) Honey: Analysis of the Phenolic Profile and Antioxidant Activity. Food Technol. Biotechnol. 2022, 60, 509–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zam, W.; al Asaad, N.; Jarkas, B.; Nukari, Z.; Dunia, S. Extracting and studying the antioxidant capacity of polyphenols in dry linden leaves (Tilia cordata). J. Pharmacogn. Phytochem. 2017, 258, 258–262. [Google Scholar]

- Lyu, J.I.; Ryu, J.; Seo, K.-S.; Kang, K.-Y.; Park, S.H.; Ha, T.H.; Ahn, J.-W.; Kang, S.-Y. Comparative Study on Phenolic Compounds and Antioxidant Activities of Hop (Humulus lupulus L.) Strobile Extracts. Plants 2022, 11, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witkowska, A.; Gryn-Rynko, A.; Syrkiewicz, P.; Kitala-Tańska, K.; Majewski, M.S. Characterizations of White Mulberry, Sea-Buckthorn, Garlic, Lily of the Valley, Motherwort, and Hawthorn as Potential Candidates for Managing Cardiovascular Disease-In Vitro and Ex Vivo Animal Studies. Nutrients 2024, 16, 1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noda, K.; Kato, E.; Kawabata, J. Intestinal α-Glucosidase Inhibitors in Achillea millefolium. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2017, 12, 1934578X1701200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalska, A.; Leoniak, K.; Sołowiej, B.G. Consumers’ attitudes and intentions toward functional beverages: A lesson for producers and retailers. Decision 2024, 51, 321–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbo, M.R.; Bevilacqua, A.; Petruzzi, L.; Casanova, F.P.; Sinigaglia, M. Functional Beverages: The Emerging Side of Functional Foods. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2014, 13, 1192–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grand View Research. Functional Drinks Market Size, Share & Trends Analysis Report. Available online: https://www.grandviewresearch.com/industry-analysis/functional-drinks-market (accessed on 15 November 2025).

- Panou, A.; Karabagias, I.K. Composition, Properties, and Beneficial Effects of Functional Beverages on Human Health. Beverages 2025, 11, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.J.; Kim, M.O.; Kim, J.H.; Jeong, S.; Kim, M.H.; Yang, S.J.; Lee, J.; Lee, H.J. Antioxidant Activities of Functional Beverage Concentrates Containing Herbal Medicine Extracts. Prev. Nutr. Food Sci. 2017, 22, 16–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marat, N.; Danowska-Oziewicz, M.; Narwojsz, A. Chaenomeles Species—Characteristics of Plant, Fruit and Processed Products: A Review. Plants 2022, 11, 3036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Li, X.; Zhou, B.; Li, H.; Zeng, J. Anti-diabetic activity in type 2 diabetic mice and α-glucosidase inhibitory, antioxidant and anti-inflammatory potential of chemically profiled pear peel and pulp extracts (Pyrus spp.). J. Funct. Foods 2015, 13, 276–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turkiewicz, I.P.; Wojdyło, A.; Tkacz, K.; Lech, K.; Nowicka, P. Osmotic Dehydration as a Pretreatment Modulating the Physicochemical and Biological Properties of the Japanese Quince Fruit Dried by the Convective and Vacuum-Microwave Method. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2020, 13, 1801–1816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Repajić, M.; Cegledi, E.; Zorić, Z.; Pedisić, S.; Elez Garofulić, I.; Radman, S.; Palčić, I.; Dragović-Uzelac, V. Bioactive Compounds in Wild nettle (Urtica dioica L.) Leaves and Stalks: Polyphenols and Pigments upon Seasonal and Habitat Variations. Foods 2021, 10, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wojdyło, A.; Teleszko, M.; Oszmiański, J. Physicochemical characterisation of quince fruits for industrial use: Yield, turbidity, viscosity and colour properties of juices. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2014, 49, 1818–1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghoshal, G.; Kansal, S.K. 2—The Emerging Trends in Functional and Medicinal Beverage Research and Its Health Implication. In Functional and Medicinal Beverages; Grumezescu, A.M., Holban, A.M., Eds.; Academic Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 41–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowicka, P.; Wojdyło, A.; Laskowski, P. Principal component analysis (PCA) of physicochemical compounds’ content in different cultivars of peach fruits, including qualification and quantification of sugars and organic acids by HPLC. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2019, 245, 929–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowicka, P.; Wojdyło, A.; Lech, K.; Figiel, A. Chemical Composition, Antioxidant Capacity, and Sensory Quality of Dried Sour Cherry Fruits pre-Dehydrated in Fruit Concentrates. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2015, 8, 2076–2095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaik, M.I.; Hamdi, I.H.; Sarbon, N.M. A comprehensive review on traditional herbal drinks: Physicochemical, phytochemicals and pharmacology properties. Food Chem. Adv. 2023, 3, 100460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorathiya, K.B.; Melo, A.; Hogg, M.C.; Pintado, M. Organic Acids in Food Preservation: Exploring Synergies, Molecular Insights, and Sustainable Applications. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turkiewicz, I.P.; Wojdyło, A.; Tkacz, K.; Nowicka, P.; Golis, T.; Bąbelewski, P. ABTS On-Line Antioxidant, α-Amylase, α-Glucosidase, Pancreatic Lipase, Acetyl- and Butyrylcholinesterase Inhibition Activity of Chaenomeles Fruits Determined by Polyphenols and other Chemical Compounds. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akagić, A.; Oras, A.; Gaši, F.; Meland, M.; Drkenda, P.; Memić, S.; Spaho, N.; Žuljević, S.O.; Jerković, I.; Musić, O.; et al. A Comparative Study of Ten Pear (Pyrus communis L.) Cultivars in Relation to the Content of Sugars, Organic Acids, and Polyphenol Compounds. Foods 2022, 11, 3031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Msomi, N.Z.; Erukainure, O.L.; Islam, M.S. Suitability of sugar alcohols as antidiabetic supplements: A review. J. Food Drug Anal. 2021, 29, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shkembi, B.; Huppertz, T. Calcium Absorption from Food Products: Food Matrix Effects. Nutrients 2021, 14, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urdampilleta, A.; Gómez-Zorita, S.; Soriano, J.M.; Martínez-Sanz, J.M.; Medina, S.; Gil-Izquierdo, A. Hydration and chemical ingredients in sport drinks: Food safety in the European context. Nutr. Hosp. 2015, 31, 1889–1899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, C.; Zhao, W.; Zhang, Y.; Li, L.; Lu, J.; Jiang, L.; Wang, C.; Jia, W. Low serum magnesium levels are associated with impaired peripheral nerve function in type 2 diabetic patients. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 32623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva Neto, L.G.R.; Santos Neto, J.E.D.; Bueno, N.B.; de Oliveira, S.L.; Ataide, T.D.R. Effects of iron supplementation versus dietary iron on the nutritional iron status: Systematic review with meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2019, 59, 2553–2561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, K.J.; de Oliveira, A.R.; Marreiro Ddo, N. Antioxidant role of zinc in diabetes mellitus. World J. Diabetes 2015, 6, 333–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Đurović, S.; Micić, D.; Šorgić, S.; Popov, S.; Gašić, U.; Tosti, T.; Kostić, M.; Smyatskaya, Y.A.; Blagojević, S.; Zeković, Z. Recovery of Polyphenolic Compounds and Vitamins from the Stinging Nettle Leaves: Thermal and Behavior and Biological Activity of Obtained Extracts. Molecules 2023, 28, 2278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masood, A.; Nadeem, A.; Mustafa, S.J.; O’Donnell, J.M. Reversal of oxidative stress-induced anxiety by inhibition of phosphodiesterase-2 in mice. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2008, 326, 369–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nowicka, P.; Wojdyło, A. Anti-Hyperglycemic and Anticholinergic Effects of Natural Antioxidant Contents in Edible Flowers. Antioxidants 2019, 8, 308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daryanavard, H.; Postiglione, A.E.; Mühlemann, J.K.; Muday, G.K. Flavonols modulate plant development, signaling, and stress responses. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2023, 72, 102350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreyra, M.L.F.; Serra, P.; Casati, P. Recent advances on the roles of flavonoids as plant protective molecules after UV and high light exposure. Physiol. Plant. 2021, 173, 736–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojdyło, A.; Oszmiański, J.; Czemerys, R. Antioxidant activity and phenolic compounds in 32 selected herbs. Food Chem. 2007, 105, 940–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Tuo, X.; Wang, L.; Tundis, R.; Portillo, M.P.; Simal-Gandara, J.; Yu, Y.; Zou, L.; Xiao, J.; Deng, J. Bioactive procyanidins from dietary sources: The relationship between bioactivity and polymerization degree. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 111, 114–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozłowska, M.; Ścibisz, I.; Przybył, J.; Ziarno, M.; Żbikowska, A.; Majewska, E. Phenolic Contents and Antioxidant Activity of Extracts of Selected Fresh and Dried Herbal Materials. Pol. J. Food Nutr. Sci. 2021, 71, 269–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, L.; Mengjun, M.; Chen, L.; Luo, L. Stability of tea polyphenols solution with different pH at different temperatures. Int. J. Food Prop. 2017, 20, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Su, X.; Jia, Q.; Chen, H.; Zeng, S.; Xu, H. Influence of Heat Treatment on Tea Polyphenols and Their Impact on Improving Heat Tolerance in Drosophila melanogaster. Foods 2023, 12, 3874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imran, I.B.; Karonen, M.; Salminen, J.P.; Engström, M.T. Modification of Natural Proanthocyanidin Oligomers and Polymers Via Chemical Oxidation under Alkaline Conditions. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 4726–4739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.M.; Rahaman, M.S.; Islam, M.R.; Rahman, F.; Mithi, F.M.; Alqahtani, T.; Almikhlafi, M.A.; Alghamdi, S.Q.; Alruwaili, A.S.; Hossain, M.S.; et al. Role of Phenolic Compounds in Human Disease: Current Knowledge and Future Prospects. Molecules 2021, 27, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahadoran, Z.; Mirmiran, P.; Azizi, F. Dietary polyphenols as potential nutraceuticals in management of diabetes: A review. J. Diabetes Metab. Disord. 2013, 12, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barros, L.; Dueñas, M.; Inês, M.; Sousa, M.; Santos Buelga, C.; Ferreira, I. Phenolic profiles of cultivated, in vitro cultured and commercial samples of Melissa officinalis L. infusions. Food Chem. 2013, 136, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ćavar Zeljković, S.; Šišková, J.; Komzáková, K.; De Diego, N.; Kaffková, K.; Tarkowski, P. Phenolic Compounds and Biological Activity of Selected Mentha Species. Plants 2021, 10, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sęczyk, Ł.; Jariene, E.; Sugier, D.; Kołodziej, B. Effects of the dose of administration, co-antioxidants, food matrix, and digestion-related factors on the in vitro bioaccessibility of rosmarinic acid—A model study. Food Chem. 2024, 449, 139201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Li, X.; Xu, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhang, W.; Guo, R.; Song, J. Progress, pharmacokinetics and future perspectives of luteolin modulating signaling pathways to exert anticancer effects: A review. Medicine 2024, 103, e39398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Wang, M.; Chen, L.; Liu, Y.; Liu, H.; Huo, H.; Sun, L.; Ren, X.; Deng, Y.; Qi, A. Structure-solubility relationships and thermodynamic aspects of solubility of some flavonoids in the solvents modeling biological media. J. Mol. Liq. 2017, 225, 439–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cilla, A.; Laparra Llopis, J.M.; Alegría, A.; Barbera, R.; Farre, R. Antioxidant effect derived from bioaccessible fractions of fruit beverages against H2O2-induced oxidative stress in Caco-2 cells. Food Chem. 2008, 106, 1180–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falé, P.; Ascensao, L.; Serralheiro, M.L. Effect of luteolin and apigenin on rosmarinic acid bioavailability in Caco-2 cell monolayers. Food Funct. 2012, 4, 426–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, H.; Xu, Y.; Wang, D.; Zhu, X.; Wang, M.; Teng, J. Menthol-based hydrophobic deep eutectic solvents for the purification of tea peroxidase using a three-phase partition method. LWT 2025, 218, 117528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baeza, G.; Sarriá, B.; Bravo, L.; Mateos, R. Polyphenol content, in vitro bioaccessibility and antioxidant capacity of widely consumed beverages. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2018, 98, 1397–1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantele, C.; Rojo-Poveda, O.; Bertolino, M.; Ghirardello, D.; Cardenia, V.; Barbosa-Pereira, L.; Zeppa, G. In Vitro Bioaccessibility and Functional Properties of Phenolic Compounds from Enriched Beverages Based on Cocoa Bean Shell. Foods 2020, 9, 715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Romero, J.D.; Arce-Reynoso, A.; Parra-Torres, C.G.; Zamora-Gasga, V.M.; Mendivil, E.J.; Sáyago-Ayerdi, S.G. In Vitro Gastrointestinal Digestion Affects the Bioaccessibility of Bioactive Compounds in Hibiscus sabdariffa Beverages. Molecules 2023, 28, 1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuvas-Limon, R.B.; Ferreira-Santos, P.; Cruz, M.; Teixeira, J.A.; Belmares, R.; Nobre, C. Effect of Gastrointestinal Digestion on the Bioaccessibility of Phenolic Compounds and Antioxidant Activity of Fermented Aloe vera Juices. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 2479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Wang, Y.; Li, D.; Ho, C.T.; Li, J.; Wan, X. The absorption, distribution, metabolism and excretion of procyanidins. Food Funct. 2016, 7, 1273–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Déprez, S.; Mila, I.; Lapierre, C.; Brezillon, C.; Rabot, S.; Philippe, C.; Scalbert, A. Polymeric Proanthocyanidins Are Catabolized by Human Colonic Microflora into Low-Molecular-Weight Phenolic Acids. J. Nutr. 2000, 130, 2733–2738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil, K.A.; Wojdyło, A.; Nowicka, P.; Montoro, P.; Tuberoso, C.I.G. Effect of Apple Juice Enrichment with Selected Plant Materials: Focus on Bioactive Compounds and Antioxidant Activity. Foods 2023, 12, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nowicka, P.; Wojdyło, A.; Laskowski, P. Inhibitory Potential against Digestive Enzymes Linked to Obesity and Type 2 Diabetes and Content of Bioactive Compounds in 20 Cultivars of the Peach Fruit Grown in Poland. Plant Foods Hum. Nutr. 2018, 73, 314–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owczarek, L.; Jasińska, U.; Osińska, M.; Skapska, S. Juices and beverages with a controlled phenolic content and antioxidant capacity. Pol. J. Food Nutr. Sci. 2004, 13, 261–268. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, L.; Xu, B.T.; Gan, R.Y.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, X.R.; Xia, E.Q.; Li, H.B. Total phenolic contents and antioxidant capacities of herbal and tea infusions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2011, 12, 2112–2124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrasekara, A.; Shahidi, F. Herbal beverages: Bioactive compounds and their role in disease risk reduction—A review. J. Tradit. Complement. Med. 2018, 8, 451–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowicka, P.; Wojdyło, A.; Samoticha, J. Evaluation of phytochemicals, antioxidant capacity, and antidiabetic activity of novel smoothies from selected Prunus fruits. J. Funct. Foods 2016, 25, 397–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Mijalli, S.H.; Mrabti, N.N.; Ouassou, H.; Sheikh, R.A.; Assaggaf, H.; Bakrim, S.; Abdallah, E.M.; Alshahrani, M.M.; Al Awadh, A.A.; Lee, L.-H.; et al. Chemical Composition and Antioxidant, Antimicrobial, and Anti-Inflammatory Properties of Origanum compactum Benth Essential Oils from Two Regions: In Vitro and In Vivo Evidence and In Silico Molecular Investigations. Molecules 2022, 27, 7329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altamimi, M.A.; Abu-Reidah, I.M.; Altamimi, A.; Jaradat, N. Hydroethanolic Extract of Urtica dioica L. (Stinging nettle) Leaves as Disaccharidase Inhibitor and Glucose Transport in Caco-2 Hinderer. Molecules 2022, 27, 8872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohebbi, S.; Naserkheil, M.; Kamalinejad, M.; Hosseini, S.H.; Noubarani, M.; Mirmohammadlu, M.; Eskandari, M.R. Antihyperglycemic activity of quince (Cydonia oblonga Mill.) fruit extract and its fractions in the rat model of diabetes. Int. Pharm. Acta 2019, 2, 2e7:1-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowicka, P.; Wojdyło, A.; Tkacz, K.; Turkiewicz, I.P. Quantitative and qualitative determination of carotenoids and polyphenolics compounds in selected cultivars of Prunus persica L. and their ability to in vitro inhibit lipoxygenase, cholinoesterase, α-amylase, α-glucosidase and pancreatic lipase. Food Chem. X 2023, 17, 100619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dancey, C.P.; Reidy, J. Statistics Without Maths for Psychology; Pearson Education Limited: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Terra, X.; Valls, J.; Vitrac, X.; Mérrillon, J.M.; Arola, L.; Ardèvol, A.; Bladé, C.; Fernandez-Larrea, J.; Pujadas, G.; Salvadó, J.; et al. Grape-seed procyanidins act as antiinflammatory agents in endotoxin-stimulated RAW 264.7 macrophages by inhibiting NFkB signaling pathway. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2007, 55, 4357–4365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitzer, Z.T.; Glisan, S.L.; Dorenkott, M.R.; Goodrich, K.M.; Ye, L.; O’Keefe, S.F.; Lambert, J.D.; Neilson, A.P. Cocoa procyanidins with different degrees of polymerization possess distinct activities in models of colonic inflammation. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2015, 26, 827–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bak, M.J.; Truong, V.L.; Kang, H.S.; Jun, M.; Jeong, W.S. Anti-inflammatory effect of procyanidins from wild grape (Vitis amurensis) seeds in LPS-induced RAW 264.7 cells. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2013, 2013, 409321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 12145:2001; Soki Owocowe i Warzywne. Oznaczanie Całkowitej Suchej Substancji. Metoda Grawimetryczna Oznaczania Ubytku Masy w Wyniku Suszenia. Polish Committee for Standardization: Warsaw, Poland, 2001.

- 12147:2000; Soki Owocowe i Warzywne. Oznaczanie Kwasowości Miareczkowej. Polish Committee for Standardization: Warsaw, Poland, 2000.

- Wojdyło, A.; Nowicka, P.; Carbonell-Barrachina, Á.A.; Hernández, F. Phenolic compounds, antioxidant and antidiabetic activity of different cultivars of Ficus carica L. fruits. J. Funct. Foods 2016, 25, 421–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojdyło, A.; Oszmiański, J.; Bielicki, P. Polyphenolic composition, antioxidant activity, and polyphenol oxidase (PPO) activity of quince (Cydonia oblonga Miller) varieties. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2013, 61, 2762–2772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, J.A.; Jones, G.P. Analysis of proanthocyanidin cleavage products following acid-catalysis in the presence of excess phloroglucinol. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2001, 49, 1740–1746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Świeca, M.; Gawlik-Dziki, U.; Dziki, D.; Baraniak, B. Wheat bread enriched with green coffee—In vitro bioaccessibility and bioavailability of phenolics and antioxidant activity. Food Chem. 2017, 221, 1451–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Re, R.; Pellegrini, N.; Proteggente, A.; Pannala, A.; Yang, M.; Rice-Evans, C. Antioxidant activity applying an improved ABTS radical cation decolorization assay. Free. Radic. Biol. Med. 1999, 26, 1231–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benzie, I.F.; Strain, J.J. The ferric reducing ability of plasma (FRAP) as a measure of “antioxidant power”: The FRAP assay. Anal. Biochem. 1996, 239, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, B.; Huang, D.; Hampsch-Woodill, M.; Flanagan, J.A.; Deemer, E.K. Analysis of antioxidant activities of common vegetables employing oxygen radical absorbance capacity (ORAC) and ferric reducing antioxidant power (FRAP) assays: A comparative study. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2002, 50, 3122–3128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 8589:2009; Sensory Analysis—General Guidelines for the Design of Sensory Analysis Laboratories. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2009.

| No. | Final Products | |

|---|---|---|

| Juice | Herbal | |

| 0 | 100% pear ÷ flowering quince juice (4 ÷ 1) | |

| 1 | 85% pear ÷ flowering quince juice (4 ÷ 1) | 15% infusion of lemon balm ÷ horsetail (1 ÷ 1) |

| 2 | 85% pear ÷ flowering quince juice (4 ÷ 1) | 15% infusion of mint ÷ nettle (1 ÷ 1) |

| 3 | 85% pear ÷ flowering quince juice (4 ÷ 1) | 15% infusion small leaved lime ÷ hops (1 ÷ 1) |

| 4 | 85% pear ÷ flowering quince juice (4 ÷ 1) | 15% infusion white mulberry ÷ common yarrow (1 ÷ 1) |

| Parameter | 100% Pear–Flowering Quince Juice (0) | No. of Product * | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |||

| Colour | L* | 51.62 ± 0.08 a | 49.39 ± 0.26 d | 45.31 ± 0.03 b | 51.62 ± 0.16 a | 46.79 ± 0.17 c |

| a* | −3.52 ± 0.01 a | −0.93 ± 0.05 c | 0.28 ± 0.04 d | −3.4 ± 0.09 a | −2.3 ± 0.03 b | |

| b* | 13.46 ± 0.05 b | 18.10 ± 0.11 d | 16.08 ± 0.11 c | 14.50 ± 0.42 a | 14.30 ± 0.27 a | |

| hue (°) | 104.66 ± 0.07 | 92.94 ± 0.16 | 89.00 ± 0.14 | 103.20 ± 0.50 | 99.14 ± 0.21 | |

| Chroma (C*) | 13.91 ± 0.05 | 18.12 ± 0.11 | 16.08 ± 0.11 | 14.89 ± 0.41 | 14.48 ± 0.27 | |

| Turbidity stability (% NTU) | 6.87 ± 0.55 a | 5.77 ± 0.11 ab | 4.35 ± 0.36 b | 6.72 ± 0.45 a | 9.65 ± 0.91 c | |

| Dry matter (%) | 12.51 ± 0.01 c | 11.15 ± 0.05 b | 10.98 ± 0.01 a | 11.19 ± 0.03 b | 10.87 ± 0.03 a | |

| Soluble solid (°Brix) | 11.4 ± 0.0 a | 10.2 ± 0.1 b | 10.1 ± 0.0 b | 10.2 ± 0.1 b | 10.1 ± 0.0 b | |

| Total acidity (g malic acid/100 mL) | 1.38 ± 0.00 c | 1.25 ± 0.00 ab | 1.22 ± 0.00 ab | 1.27 ± 0.03 b | 1.21 ± 0.02 a | |

| pH | 3.03 ± 0.01 c | 3.13 ± 0.01 ab | 3.17 ± 0.03 b | 3.08 ± 0.02 ac | 3.14 ± 0.01 ab | |

| Vitamin C content (mg/100 mL) | 96.15 ± 2.88 a | 98.33 ± 1.97 a | 78.61 ± 1.57 c | 89.54 ± 1.34 b | 82.09 ± 1.64 c | |

| Osmosis (mOsm/kg H2O) | 785.5 ± 3.5 a | 638.0 ± 55.2 a | 666.0 ± 20.0 b | 636.0 ± 24.0 a | 631.5 ± 64.4 a | |

| Energy Value (kcal/100 mL) | 42.78 ± 0.94 a | 39.03 ± 1.02 b | 39.53 ± 0.59 b | 34.44 ± 0.23 c | 34.99 ± 0.77 c | |

| Sugar Content (g/100 mL) | 100% Pear–Flowering Quince Juice (0) | No. of Product * | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | ||

| Fructose | 6.80 ± 0.17 a | 5.96 ± 0.16 b | 5.79 ± 0.15 b | 6.00 ± 0.18 b | 5.73 ± 0.12 b |

| Sorbitol | 2.32 ± 0.04 a | 1.99 ± 0.03 b | 2.00 ± 0.04 b | 2.03 ± 0.05 b | 1.97 ± 0.02 b |

| Glucose | 1.70 ± 0.02 a | 1.48 ± 0.01 b | 1.50 ± 0.03 b | 1.51 ± 0.02 b | 1.45 ± 0.04 b |

| Sucrose | 0.86 ± 0.01 a | 0.50 ± 0.00 c | 0.49 ± 0.01 c | 0.62 ± 0.01 b | 0.64 ± 0.01 b |

| Total | 11.68 ± 0.24 a | 9.93 ± 0.20 b | 9.78 ± 0.23 b | 10.16 ± 0.26 b | 9.79 ± 0.20 b |

| Minerals Content (mg/100 mL) | 100% Pear–Flowering Quince Juice (0) | No. of Product * | Recommended Dietary Allowance (mg/day) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |||

| Ca | 3.93 ± 0.04 e | 6.38 ± 0.02 b | 8.23 ± 0.00 a | 4.53 ± 0.00 d | 5.76 ± 0.37 c | 800 **/1000 *** |

| Na | 0.91 ± 0.02 a | 0.70 ± 0.11 a | 0.74 ± 0.10 a | 0.68 ± 0.12 a | 0.73 ± 0.16 a | 2000/1500 |

| K | 7.07 ± 0.25 ab | 7.77 ± 0.29 a | 6.30 ± 0.27 c | 6.81 ± 0.24 bc | 7.46 ± 0.28 a | 2000/4700 |

| Mg | 0.29 ± 0.02 d | 0.37 ± 0.03 d | 10.43 ± 0.03 a | 7.86 ± 0.06 c | 9.26 ± 0.04 b | 375/310–420 |

| Fe | 0.28 ± 0.03 c | 0.31 ± 0.07 c | 0.54 ± 0.03 b | 0.27 ± 0.03 c | 4.96 ± 0.39 a | 14/8–18 |

| Zn | nd | 0.03 ± 0.00 a | nd | 0.01 ± 0.01 b | 0.02 ± 0.01 ab | 10/11 |

| Total | 12.47 ± 0.36 e | 15.54 ± 0.52 d | 26.23 ± 0.43 b | 20.16 ± 0.46 c | 28.19 ± 1.25 a | |

| Polyphenolic Content (mg/100 mL) | 100% Pear–Flowering Quince Juice (0) | No. of Product * | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | ||

| in fresh product | |||||

| Phenolic acids | 8.28 ± 0.14 d | 14.92 ± 0.24 b | 17.04 ± 0.51 a | 7.44 ± 0.22 e | 11.74 ± 0.35 c |

| Flavonols | 2.13 ± 0.06 e | 13.41 ± 0.20 b | 24.83 ± 0.74 a | 6.89 ± 0.21 d | 10.66 ± 0.21 c |

| Flavan-3-ols (monomeric & dimeric) | 81.96 ± 1.46 e | 90.25 ± 1.70 c | 167.41 ± 2.02 a | 87.34 ± 1.62 d | 101.90 ± 2.06 b |

| Polymeric procyanidins | 402.48 ± 9.07 a | 388.70 ± 8.66 b | 369.90 ± 7.10 c | 410.48 ± 9.31 a | 403.55 ± 9.11 a |

| Total | 494.85 ± 10.73 c | 507.28 ± 10.80 bc | 579.18 ± 10.37 a | 512.15 ± 11.36 bc | 527.85 ± 11.73 b |

| bioaccessibility | |||||

| Phenolic acids | 0.58 (7.00% **) | 2.16 (14.48%) | 3.08 (18.08%) | 0.51 (6.85%) | 1.50 (12.78%) |

| Flavonols | nd *** | 4.36 (32.51%) | 6.44 (25.94%) | 0.33 (4.79%) | 2.11 (19.79%) |

| Flavan-3-ols (monomeric & dimeric) | 9.73 (11.87%) | 5.23 (5.80%) | 17.37 (10.38%) | 5.05 (5.78%) | 7.06 (6.93%) |

| Polymeric procyanidins | 30.33 (7.54%) | 23.89 (6.15%) | 29.12 (7.87%) | 23.38 (5.70%) | 36.93 (9.15%) |

| Total | 40.64 (8.21%) | 35.64 (6.63%) | 56.01 (9.67%) | 29.27 (5.72%) | 47.06 (9.02%) |

| bioavailability | |||||

| Phenolic acids | nd | 0.64 (29.62%) | 0.92 (29.87%) | nd | nd |

| Flavonols | nd | 0.91 (20.87%) | 1.19 (18.48%) | nd | 0.27 (12.80%) |

| Flavan-3-ols (monomeric & dimeric) | 1.52 (15.62% ****) | 1.24 (23.71%) | 4.14 (23.83%) | 0.89 (17.62%) | 1.86 (26.35%) |

| Polymeric procyanidins | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd |

| Total | 1.52 (3.74%) | 2.79 (7.83%) | 6.25 (11.16%) | 0.89 (3.04%) | 2.13 (4.53) |

| Kind of Effect | Inhibition Effect IC50 (mg/mL) | 100% Pear–Flowering Quince Juice (0) | No. of Product * | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |||

| anti-diabetic | α-amylase | 0.5000.999 ** e | 0.5260.999 c | 0.3660.942 a | 0.5180.999 d | 0.5721.000 b |

| α-glucosidase | <0.0200.999 a | 0.0930.747 b | 1.5230.798 d | 0.9710.992 c | 1.4950.999 d | |

| anti-obesity | pancreatic lipase | 0.0500.995 a | 0.0570.991 b | 0.0630.991 c | 0.0560.954 b | 0.0570.998 b |

| anti-inflammatory | LOX-15 | 0.1530.995 b | 0.1490.971 b | 0.2950.746 d | 0.1790.911 c | 0.1110.991 a |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mikołajczak, H.; Nowicka, P. Modulating the Bioavailability and Bioaccessibility of Polyphenolic Compounds and Enhancing Health-Promoting Properties Through the Addition of Herbal Extracts to a Functional Beverage. Molecules 2025, 30, 4796. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244796

Mikołajczak H, Nowicka P. Modulating the Bioavailability and Bioaccessibility of Polyphenolic Compounds and Enhancing Health-Promoting Properties Through the Addition of Herbal Extracts to a Functional Beverage. Molecules. 2025; 30(24):4796. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244796

Chicago/Turabian StyleMikołajczak, Hanna, and Paulina Nowicka. 2025. "Modulating the Bioavailability and Bioaccessibility of Polyphenolic Compounds and Enhancing Health-Promoting Properties Through the Addition of Herbal Extracts to a Functional Beverage" Molecules 30, no. 24: 4796. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244796

APA StyleMikołajczak, H., & Nowicka, P. (2025). Modulating the Bioavailability and Bioaccessibility of Polyphenolic Compounds and Enhancing Health-Promoting Properties Through the Addition of Herbal Extracts to a Functional Beverage. Molecules, 30(24), 4796. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244796