Catalytic Transformation of Ginsenoside Re over Mesoporous Silica-Supported Heteropoly Acids: Generation of Diverse Rare Ginsenosides in Aqueous Ethanol Revealed by HPLC-HRMSn

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

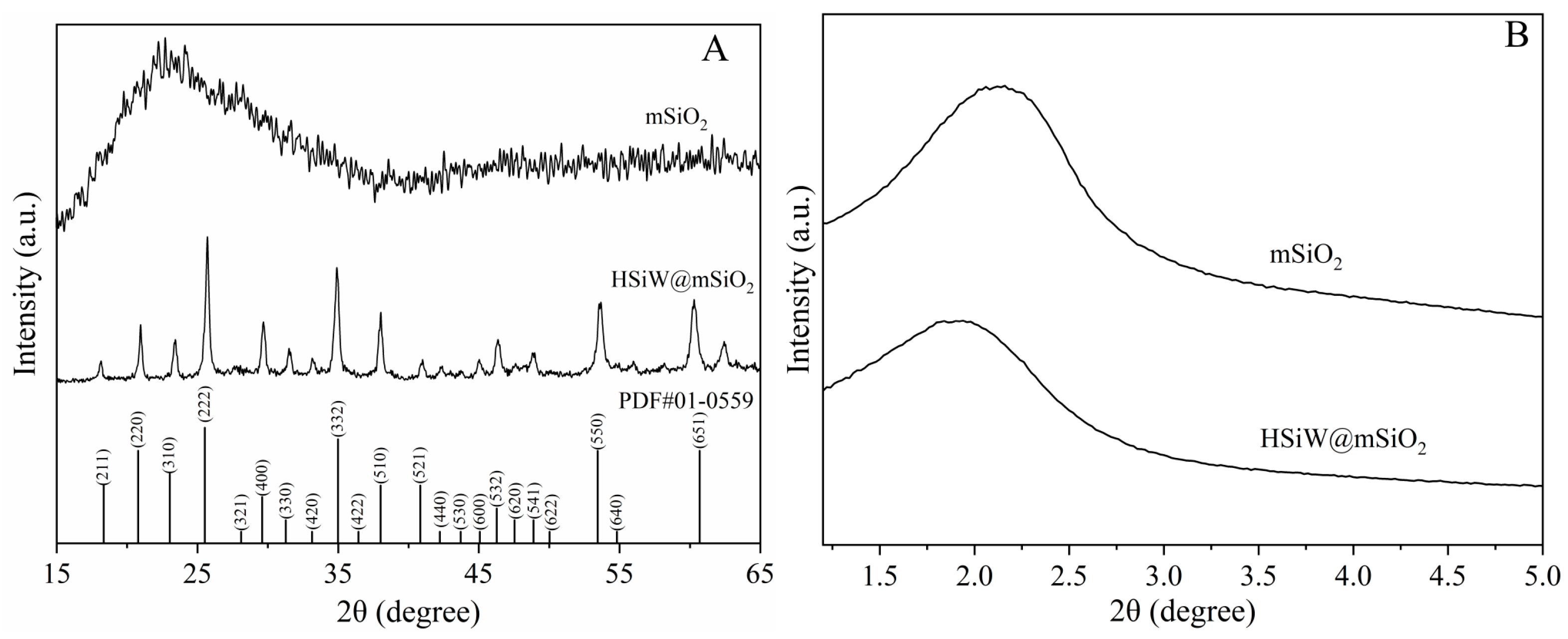

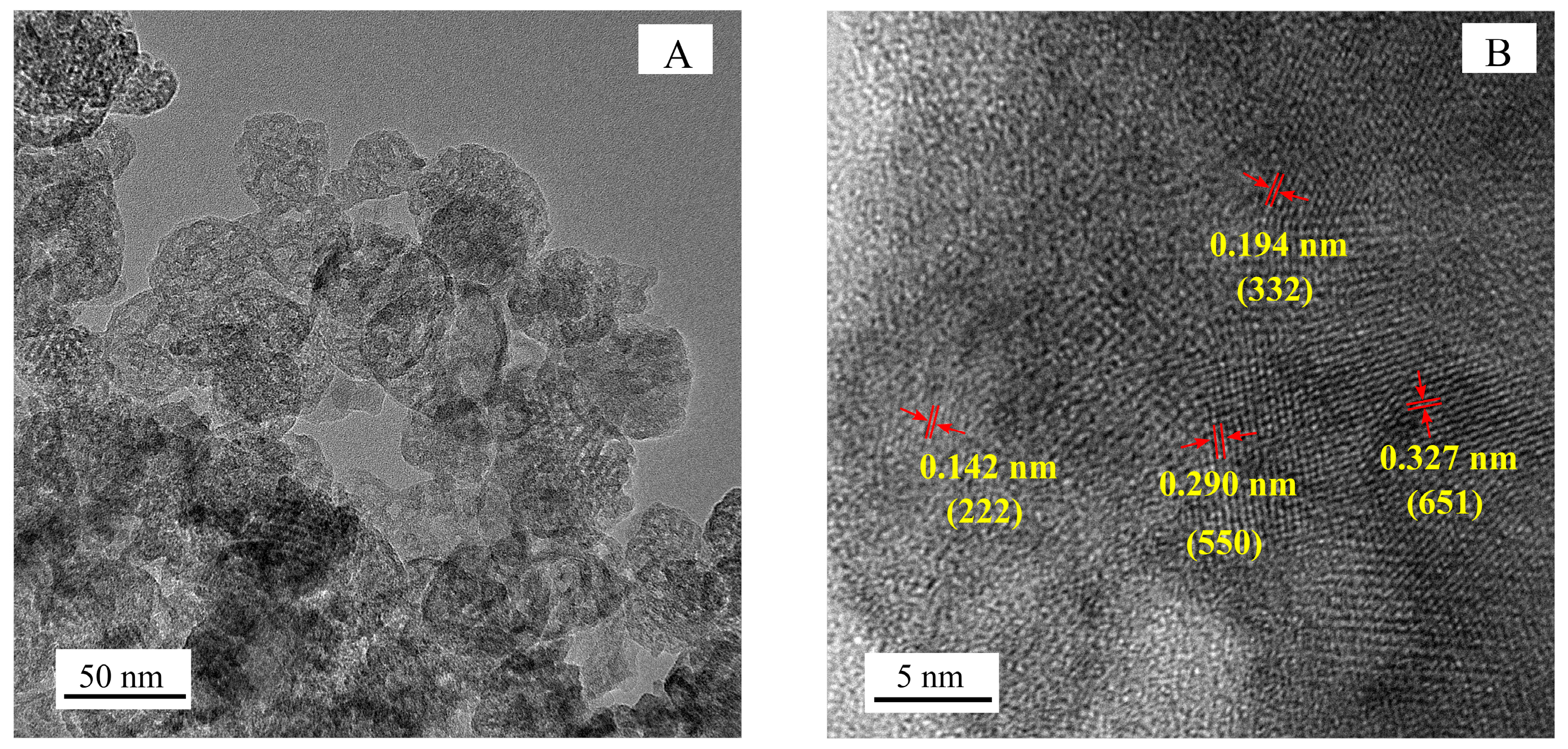

2.1. Characterization of HSiW@mSiO2

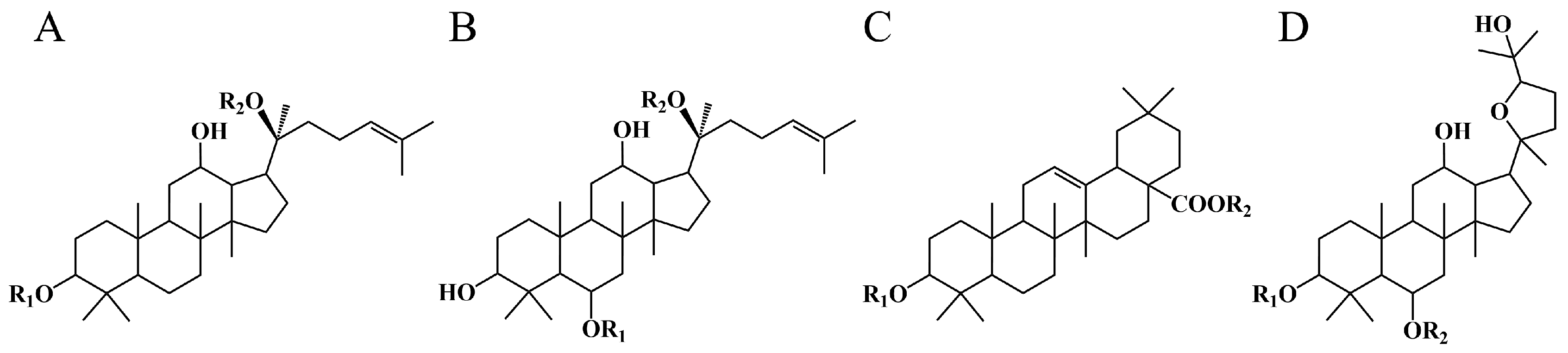

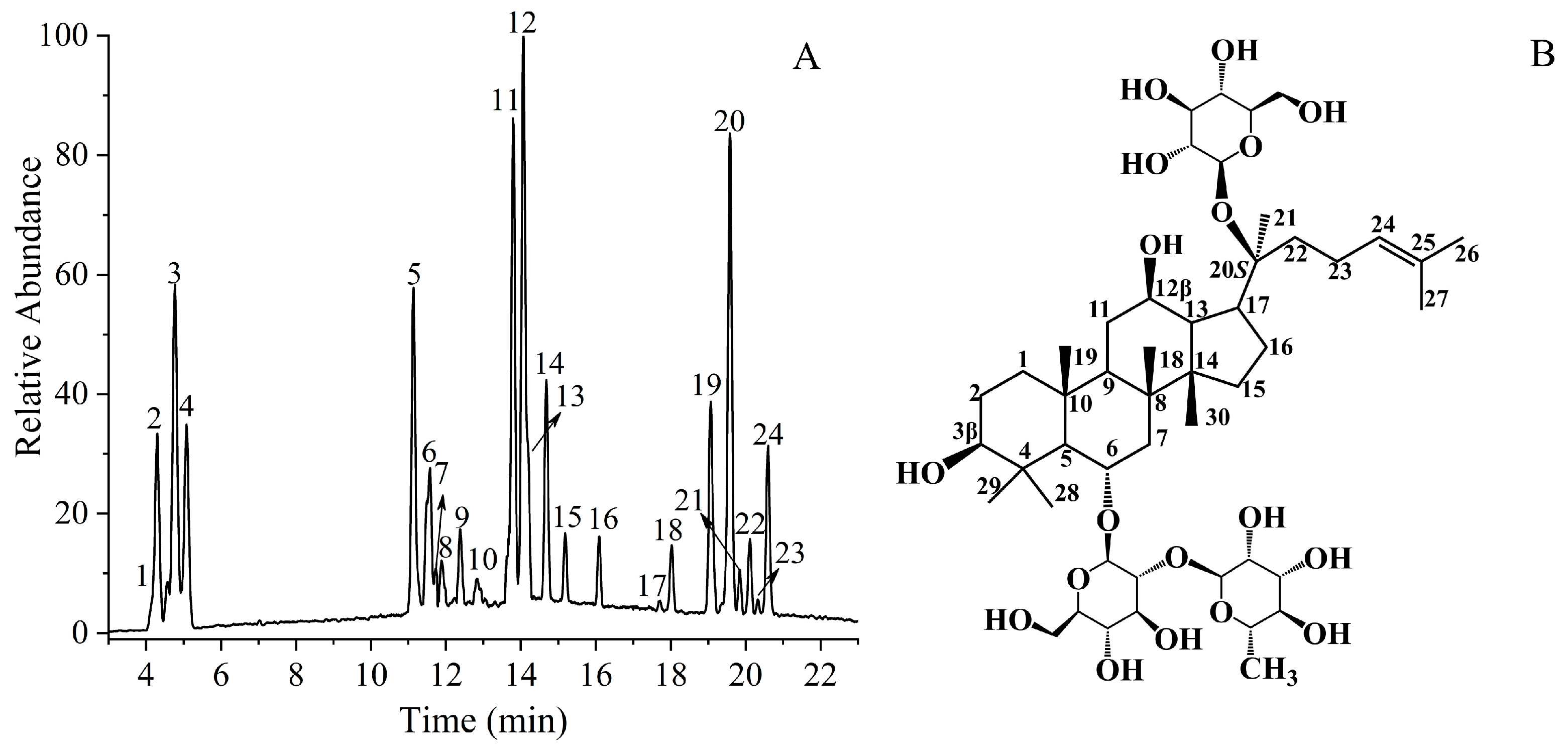

2.2. Structural Characterization and Identification of Ginsenoside Re Transformation Products in Aqueous Ethanol by HPLC-MS

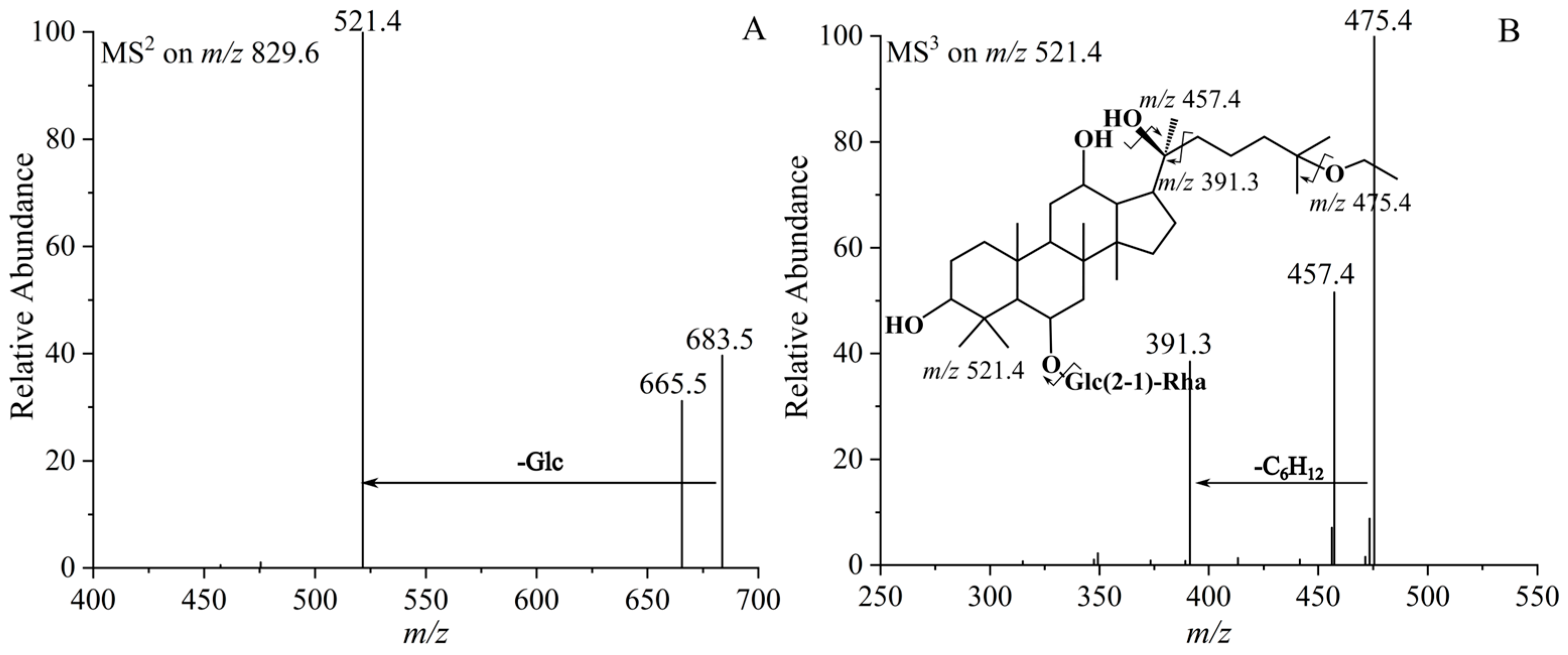

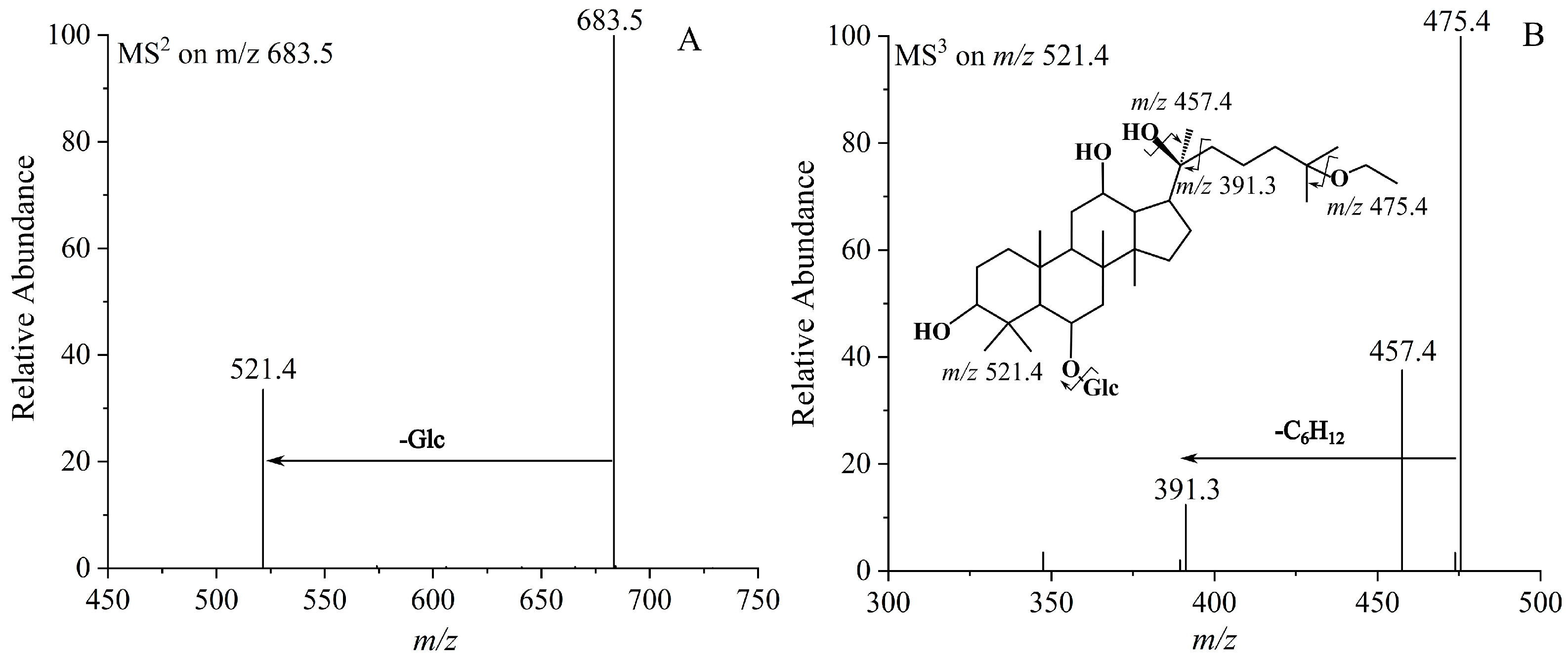

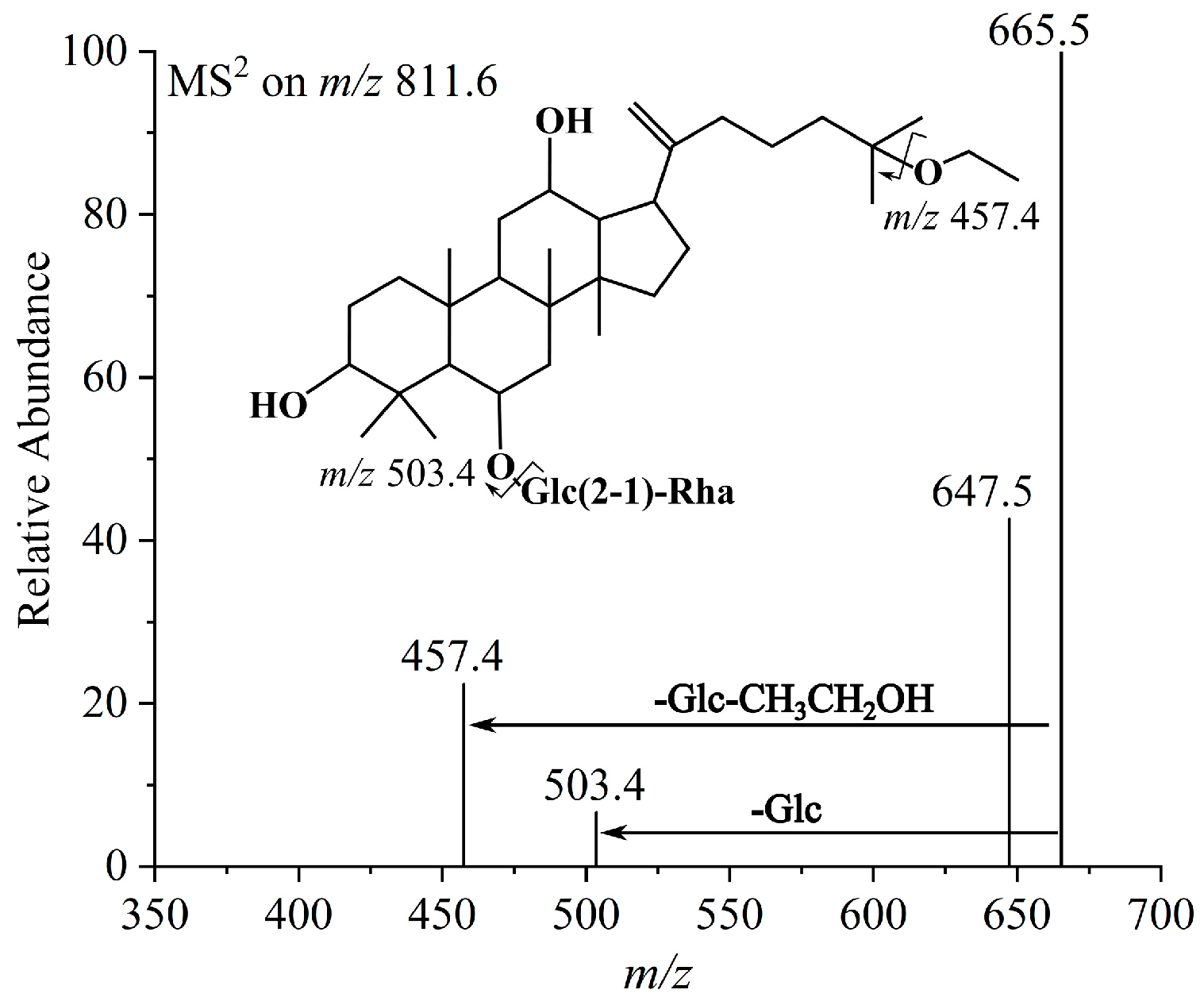

2.2.1. Identification of Ethanol Adducts

2.2.2. Identification of Hydration Adducts

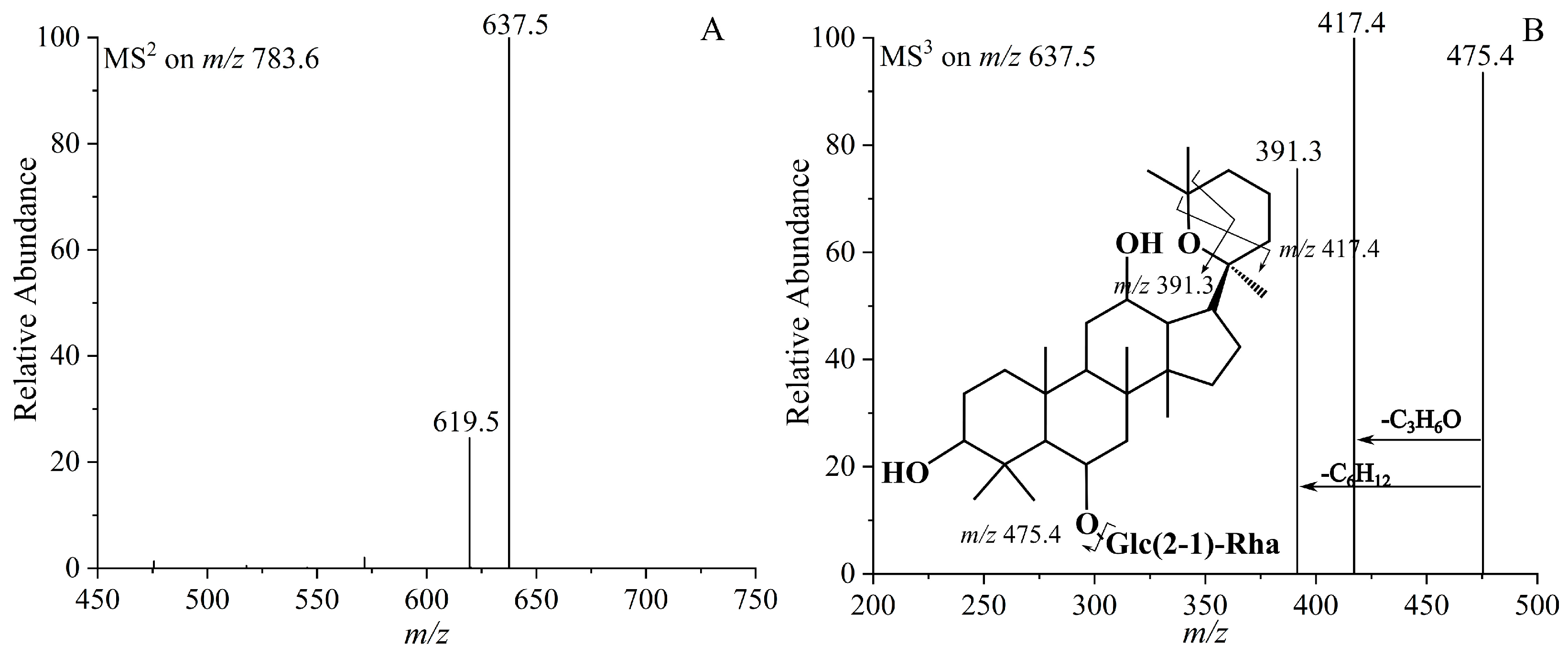

2.2.3. Identification of Cyclic Ether Derivatives

2.2.4. Identification by Comparison with Authentic Standards

2.3. Transformation Pathways and Mechanisms of Ginsenoside Re in Aqueous Ethanol

2.3.1. Regioselective Deglycosylation

2.3.2. E1 Dehydration

2.3.3. Nucleophilic Addition and Cyclization

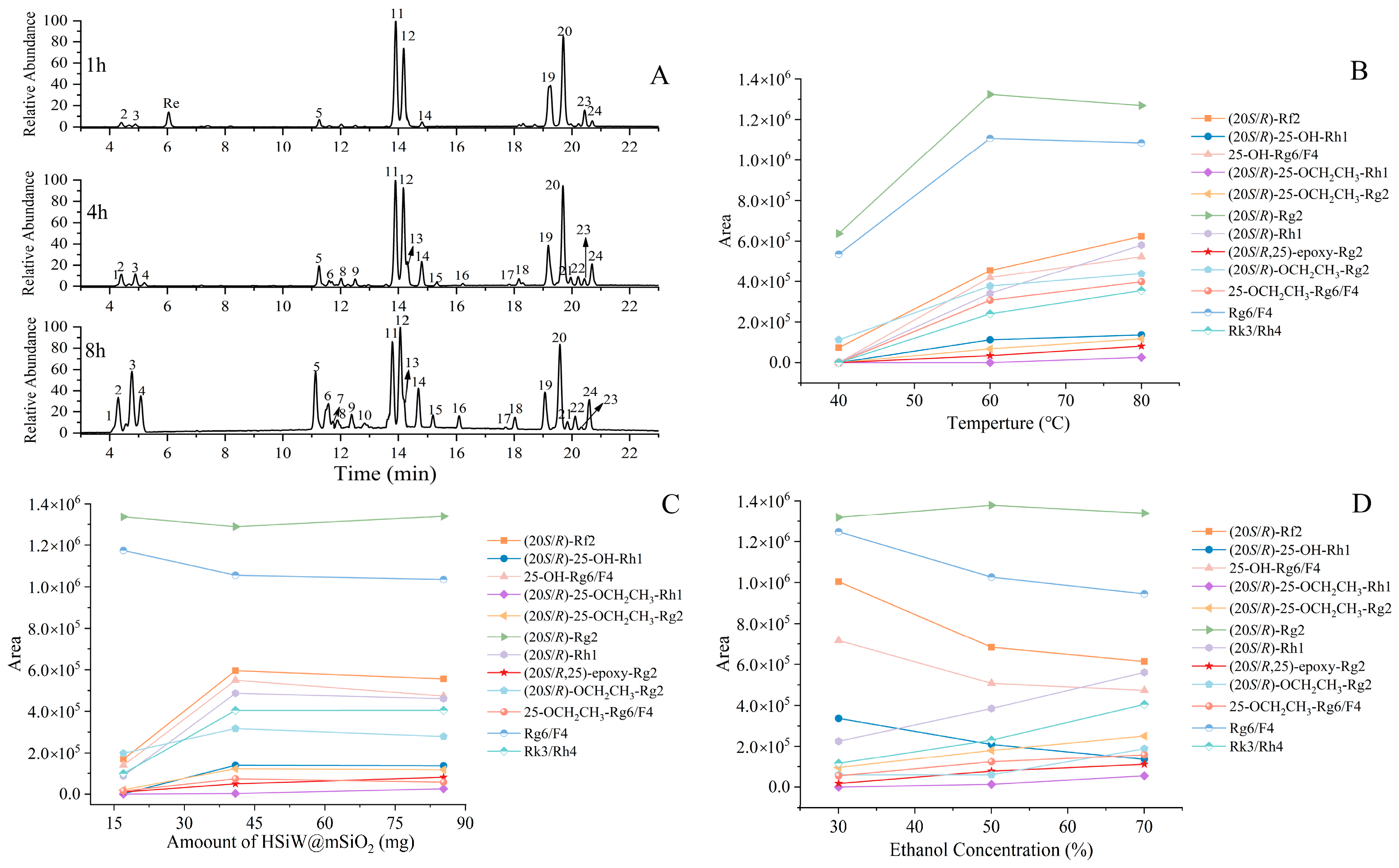

2.4. Effects of Reaction Conditions on Ginsenoside Re Transformation in Aqueous Ethanol

2.4.1. Time Course Analysis of Reaction Pathway

2.4.2. Temperature-Dependent Reaction Kinetics

2.4.3. Catalyst Dosage and Product Distribution

2.4.4. Solvent-Dependent Nucleophilic Addition Selectivity

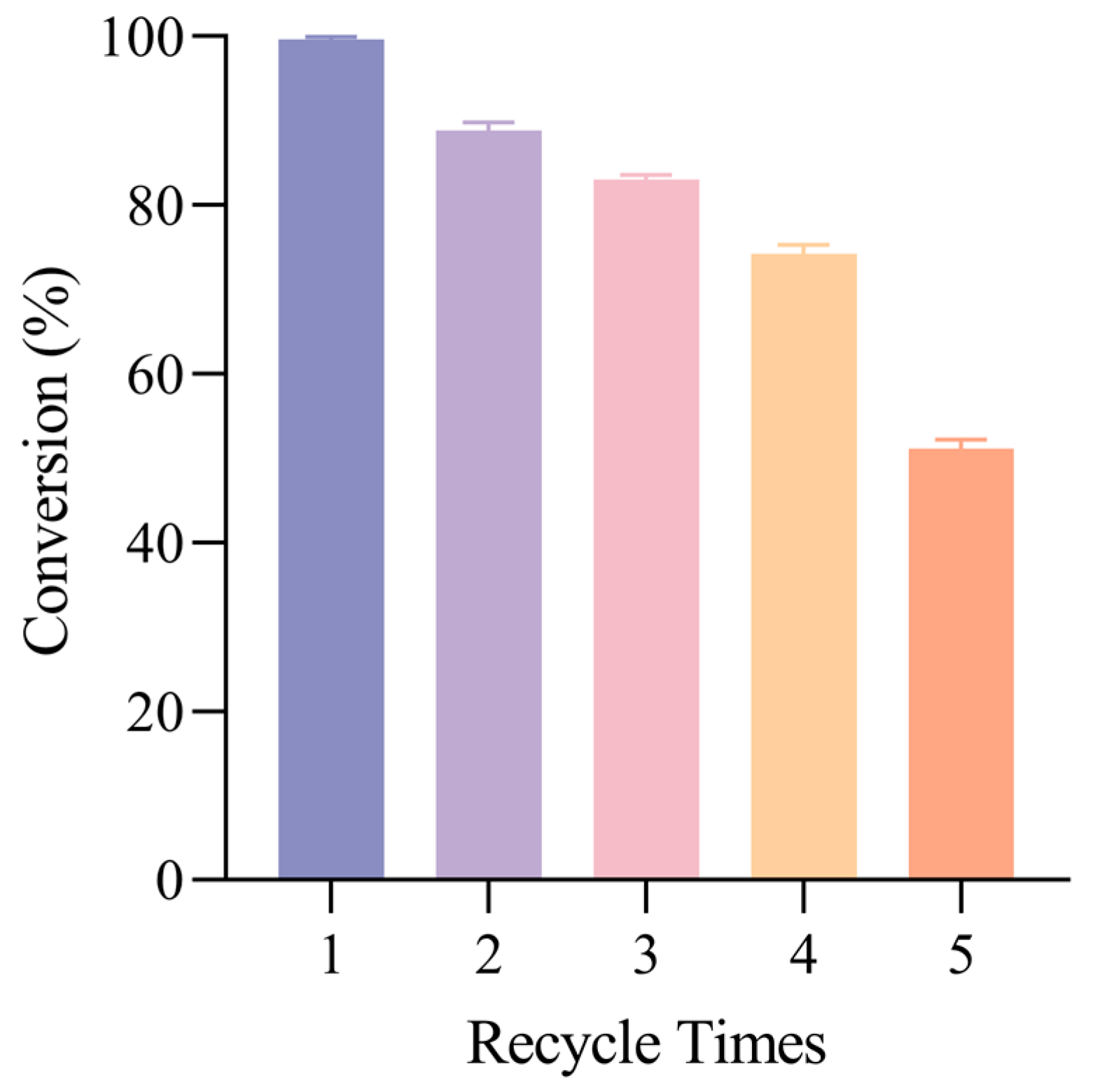

2.5. Reusability and Structural Stability of HSiW@mSiO2 in Sequential Cycles

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Chemicals and Materials

3.2. Instruments and Conditions

3.3. Sample Preparation

3.3.1. Preparation of mSiO2

3.3.2. Preparation of HSiW@mSiO2

3.3.3. Transformation of Ginsenoside Re

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- He, J.; Wang, J.; Qi, G.; Yao, L.; Li, X.; Paek, K.-Y.; Park, S.-Y.; Gao, W. Comparison of polysaccharides in ginseng root cultures and cultivated ginseng and establishment of high-content uronic acid plant synthesis system. Ind. Crops Prod. 2022, 186, 115155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, H.; Ito, M. Recent trends in ginseng research. J. Nat. Med. 2024, 78, 455–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Ren, C.; Li, H.-J.; Wu, Y.-C. Recent Progress on Processing Technologies, Chemical Components, and Bioactivities of Chinese Red Ginseng, American Red Ginseng, and Korean Red Ginseng. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2021, 15, 47–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, S.; Liu, J.; Liu, Y.; Song, J.; Wu, H.; Li, L.; Zhu, H.; Feng, B. Chemical Profiling, Quantitation, and Bioactivities of Ginseng Residue. Molecules 2023, 28, 7854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, X.; Wang, J.; Liu, Y.; Liu, L.; Liu, X.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, C.; Liu, J. Research progress on chemical diversity of saponins in Panax ginseng. Chin. Herb. Med. 2024, 16, 529–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.C.; Huang, T.H.; Yeh, K.W.; Chen, Y.L.; Shen, S.C.; Liou, C.J. Ginsenoside Rg3 ameliorates allergic airway inflammation and oxidative stress in mice. J. Ginseng Res. 2021, 45, 654–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Bai, L.; Dai, W.; Wu, Y.; Xi, P.; Zhang, J.; Zheng, L. Ginsenoside Rg3: A Review of its Anticancer Mechanisms and Potential Therapeutic Applications. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2024, 24, 869–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, R.; Kan, Q.; Wang, T.; Xiao, R.; Song, Y.; Li, D. Ginsenoside Rh2 regulates triple-negative breast cancer proliferation and apoptosis via the IL-6/JAK2/STAT3 pathway. Front. Pharmacol. 2025, 15, 1483896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiu, Y.; Zhao, H.; Gao, Y.; Liu, W.; Liu, S. Chemical transformation of ginsenoside Re by a heteropoly acid investigated using HPLC-MSn/HRMS. New J. Chem. 2016, 40, 9073–9080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Xiao, Y.; Chang, Y.; Tian, L.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, S.; Zhao, H.; Xiu, Y. Methanol-involved heterogeneous transformation of ginsenoside Rb1 to rare ginsenosides using heteropolyacids embedded in mesoporous silica with HPLC-MS investigation. J. Ginseng Res. 2024, 48, 366–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Tian, L.; Xiao, Y.; Chang, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, S.; Zhao, H.; Xiu, Y. Heterogeneous Transformation of Ginsenoside Rb1 with Ethanol Using Heteropolyacid-Loaded Mesoporous Silica and Identification by HPLC-MS. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 43285–43294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, Y.; Li, B.; Xiao, Y.; Zhao, M.; Zhou, Y.; Zhao, H.; Xiu, Y. Diverse rare ginsenosides derived from ginsenoside Re in aqueous methanol solution via heterogeneous catalysis and identified by HPLC-MS. RSC Adv. 2025, 15, 16455–16467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Feng, Y.; Chang, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Zhao, H.; Xu, W.; Zhao, M.; Xiao, Y.; Tian, L.; Xiu, Y. Biotransformation of Ginsenoside Rb1 to Ginsenoside Rd and 7 Rare Ginsenosides Using Irpex lacteus with HPLC-HRMS/MS Identification. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 22744–22753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.Y.; Lee, H.N.; Hong, S.J.; Kang, H.J.; Cho, J.Y.; Kim, D.; Ameer, K.; Kim, Y.M. Enhanced biotransformation of the minor ginsenosides in red ginseng extract by Penicillium decumbens β-glucosidase. Enzym. Microb. Technol. 2022, 153, 109941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, M.J.; Rodrigues, A.A.; Lopes, N.P.G. Keggin Heteropolyacid Salt Catalysts in Oxidation Reactions: A Review. Inorganics 2023, 11, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, C.N.; Santos-Vieira, I.C.M.S.; Gomes, C.R.; Mirante, F.; Balula, S.S. Heteropolyacids@Silica Heterogeneous Catalysts to Produce Solketal from Glycerol Acetalization. Nanomaterials 2024, 14, 733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escriche-Navarro, B.; Escudero, A.; Lucena-Sánchez, E.; Sancenón, F.; García-Fernández, A.; Martínez-Máñez, R. Mesoporous Silica Materials as an Emerging Tool for Cancer Immunotherapy. Adv. Sci. 2022, 9, 2200756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falcão, E.S.M.; Valadares, D.D.; dos Santos, G.M.; de Mendonça, E.S.D.; Santos, M.M.; Dias, S.C.L.; Dias, J.A. Preparation of 12-Tungstophosphoric Acid Embedded in a Silica Matrix and Its Effect on the Activity of 1-Propanol Dehydration. ACS Omega 2025, 10, 16277–16290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Shah, A.; Michel, F.C. Synthesis of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural from fructose and inulin catalyzed by magnetically-recoverable Fe3O4@SiO2@TiO2–HPW nanoparticles. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2019, 94, 3393–3402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, B.Y.; Jen, C.T.; Inbaraj, B.S.; Chen, B.H. A Comparative Study on Analysis of Ginsenosides in American Ginseng Root Residue by HPLC-DAD-ESI-MS and UPLC-HRMS-MS/MS. Molecules 2022, 27, 3071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.P.; Zhang, Y.B.; Yang, X.W.; Zhao, D.Q.; Wang, Y.P. Rapid characterization of ginsenosides in the roots and rhizomes of Panax ginseng by UPLC-DAD-QTOF-MS/MS and simultaneous determination of 19 ginsenosides by HPLC-ESI-MS. J. Ginseng Res. 2016, 40, 382–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.Y.; Luo, D.; Cheng, Y.J.; Ma, J.F.; Wang, Y.M.; Liang, Q.L.; Luo, G.A. Steaming-Induced Chemical Transformations and Holistic Quality Assessment of Red Ginseng Derived from Panax ginseng by Means of HPLC-ESI-MS/MSn-Based Multicomponent Quantification Fingerprint. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2012, 60, 8213–8224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abashev, M.; Stekolshchikova, E.; Stavrianidi, A. Quantitative aspects of the hydrolysis of ginseng saponins: Application in HPLC-MS analysis of herbal products. J. Ginseng Res. 2021, 45, 246–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.Q.; Yi, L.W.; Zhao, L.; Zhou, Y.Z.; Guo, F.; Huo, Y.S.; Zhao, D.Q.; Xu, F.; Wang, X.; Cai, S.Q. 177 Saponins, Including 11 New Compounds in Wild Ginseng Tentatively Identified via HPLC-IT-TOF-MSn, and Differences among Wild Ginseng, Ginseng under Forest, and Cultivated Ginseng. Molecules 2021, 26, 3371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ausavasukhi, A.; Noenkrathok, K.; Kongnok, N.; Wattanakul, T. Pivotal role of support architecture in encapsulating heteropolyacids: Enhancing water tolerance and suppressing leaching for aqueous ethanol dehydration. Sustain. Chem. Pharm. 2025, 48, 102212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zhang, X.; Dong, M.; Wu, Y.; Zheng, G.; Huang, J.; Guan, X.; Zheng, X. MCM-41 immobilized 12-silicotungstic acid mesoporous materials: Structural and catalytic properties for esterification of levulinic acid and oleic acid. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2016, 61, 147–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashtekar, S.; Hastings, J.J.; Barrie, P.J.; Gladden, L.F. Quantification of the Number of Silanol Groups in Silicalite and Mesoporous MCM-41: Use of Ft-Raman Spectroscopy. Spectrosc. Lett. 2000, 33, 569–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatt, N.; Patel, A. Esterification of 1° and 2° alcohol using an ecofriendly solid acid catalyst comprising 12-tungstosilicic acid and hydrous zirconia. J. Mol. Catal. A Chem. 2005, 238, 223–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.; Xu, H.; Zhang, Z.; Duan, Y.; Lu, X.; Lu, L.; Si, C.; Peng, Y.; Li, X. Optimizing acidic site control for selective conversion of biomass-based sugar to furfural and levulinic acid through HSiW/MCM-41 catalyst. Biomass Bioenergy 2024, 186, 107275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Xiong, W.; Liu, X.; Wang, J.; Wang, S.; Chen, Q.; Gao, K.; Li, C.; Li, Y. Biomimetic, folic acid-modified mesoporous silica nanoparticles with “stealth” and “homing” capabilities for tumor therapy. Mater. Des. 2024, 241, 112899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, A.A.; Khan, A.; Labis, J.P.; Alam, M.; Aslam Manthrammel, M.; Ahamed, M.; Akhtar, M.J.; Aldalbahi, A.; Ghaithan, H. Mesoporous multi-silica layer-coated Y2O3: Eu core-shell nanoparticles: Synthesis, luminescent properties and cytotoxicity evaluation. Mater. Sci. Eng. C Mater. Biol. Appl. 2019, 96, 365–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, X.; Garg, S.; Mortazavi, M.; Ma, J.; Waite, T.D. Heterogenous Iron Oxide Assemblages for Use in Catalytic Ozonation: Reactivity, Kinetics, and Reaction Mechanism. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 57, 18636–18646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, J.S.; Vartuli, J.C.; Roth, W.J.; Leonowicz, M.E.; Kresge, C.T.; Schmitt, K.D.; Chu, C.T.W.; Olson, D.H.; Sheppard, E.W.; McCullen, S.B.; et al. A new family of mesoporous molecular sieves prepared with liquid crystal templates. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1992, 114, 10834–10843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, G.; Kang, L.; Zhu, M.; Dai, B. Highly active phosphotungstic acid immobilized on amino functionalized MCM-41 for the oxidesulfurization of dibenzothiophene. Fuel Process. Technol. 2014, 118, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Lee, D.Y.; Kang, K.B.; Kim, J.Y.; Kim, S.O.; Yoo, Y.H.; Sung, S.H. Identification of ginsenoside markers from dry purified extract of Panax ginseng by a dereplication approach and UPLC–QTOF/MS analysis. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2015, 109, 91–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, Y.Z.; Guo, M.; Li, Y.F.; Shao, L.J.; Cui, X.M.; Yang, X.Y. Highly Regioselective Biotransformation of Protopanaxadiol-type and Protopanaxatriol-type Ginsenosides in the Underground Parts of Panax notoginseng to 18 Minor Ginsenosides by Talaromyces flavus. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 14910–14919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bockisch, C.; Lorance, E.D.; Hartnett, H.E.; Shock, E.L.; Gould, I.R. Kinetics and Mechanisms of Hydrothermal Dehydration of Cyclic 1,2- and 1,4-Diols. J. Org. Chem. 2022, 87, 14299–14307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mollar-Cuni, A.; Martín, S.; Guisado-Barrios, G.; Mata, J.A. Dual role of graphene as support of ligand-stabilized palladium nanoparticles and carbocatalyst for (de)hydrogenation of N-heterocycles. Carbon 2023, 206, 314–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahimi, L.; Mansoori, Y.; Nuri, A.; Koohi-Zargar, B.; Esquivel, D. A new Pd (II)-supported catalyst on magnetic SBA-15 for C-C bond formation via the Heck and Hiyama cross-coupling reactions. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 2020, 35, e6078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, Y.; Itonaga, K. Versatile Friedel–Crafts-Type Alkylation of Benzene Derivatives Using a Molybdenum Complex/ortho-Chloranil Catalytic System. Chem. Eur. J. 2008, 14, 10705–10715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Peak | Identification | Relative Molecular Mass | Molecular Formula | Measured [M−H]− (m/z) | Fragment Ions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | (20S)-25-OH-Rh1 | 656.4494 | C36H64O10 | 655.4478 | 493.4664 [M−Glc−H]−, 475.4215 [M−Glc−H2O−H]−, 417.4839 [M−Glc−C3H8O2−H]−, 391.3672 [M−Glc−C6H14O−H]− |

| 2 | (20S)-Rf2 | 802.5073 | C42H74O14 | 801.5087 | 655.5321 [M−Rha−H]−, 637.5381 [M−Rha−H2O−H]−, 493.4871 [M−Rha−Glc−H]−, 475.4267 [M−Glc−Rha−H2O−H]−, 417.4835 [M−Rha−Glc–C3H8O2−H]−, 391.3662 [M−Glc−Rha−C6H14O]− |

| 3 | (20R)-Rf2 | 802.5073 | C42H74O14 | 801.5081 | 655.5329 [M−Rha−H]−, 637.5385 [M−Rha−H2O−H]−, 493.4873 [M−Rha−Glc−H]−, 475.4361 [M−Glc−Rha−H2O−H]−, 417.4830 [M−Rha−Glc−C3H8O2−H]−, 391.3669 [M−Glc−Rha−C6H14O]− |

| 4 | (20R)-25-OH-Rh1 | 656.4494 | C36H64O10 | 655.4481 | 493.4668 [M−Glc−H]−, 475.4210 [M−Glc−H2O−H]−, 417.4830 [M−Glc−C3H8O2−H]−, 391.3678 [M−Glc−C6H14O−H]− |

| 5 | 25-OH-Rg6 | 784.4967 | C42H72O13 | 783.4977 | 637.5122 [M−Rha−H]−, 619.5321 [M−Rha−H2O−H]−, 475.4131 [M−Glc−Rha−H]−, 417.4831 [M−Glc−Rha−C3H6O]− |

| 6 | 25-OH-F4 | 784.4967 | C42H72O13 | 783.4982 | 637.5121 [M−Rha−H]−, 619.5322 [M−Rha−H2O−H]−, 475.4132 [M−Glc−Rha−H]−, 417.4832 [M−Glc−Rha−C3H6O]− |

| 7 | (20S)-25-OCH2CH3-Rh1 | 684.4807 | C38H68O10 | 683.4817 | 521.4324 [M−Glc−H]−, 475.4261 [M−Glc−CH3CH2OH−H]−, 457.4261 [M−Glc−CH3CH2OH−H2O−H]−, 391.4665 [M−Glc−C8H18O−H]− |

| 8 | (20S)-25-OCH2CH3-Rg2 | 830.5386 | C44H78O14 | 829.5376 | 683.5325 [M−Rha−H]−, 665.5180 [M−Rha−H2O−H]−, 521.4292 [M−Glc−Rha−H]−, 475.4261 [M−Glc−Rha−CH3CH2OH−H]−, 457.4312 [M−Glc−Rha−CH3CH2OH−H2O−H]−, 391.3662 [M−Glc−Rha−C8H18O−H]− |

| 9 | (20R)-25-OCH2CH3-Rg2 | 830.5386 | C44H78O14 | 829.5369 | 683.5323 [M−Rha−H]−, 665.5181 [M−Rha−H2O−H]−, 521.4290 [M−Glc−Rha−H]−, 475.4263 [M−Glc−Rha−CH3CH2OH−H]−, 457.4314 [M−Glc−Rha−CH3CH2OH−H2O−H]−, 391.3661 [M−Glc−Rha−C8H18O−H]− |

| 10 | (20R)-25-OCH2CH3-Rh1 | 684.4807 | C38H68O10 | 683.4816 | 521.4326 [M−Glc−H]−, 475.4263 [M−Glc−CH3CH2OH−H]−, 457.4262 [M−Glc−CH3CH2OH−H2O−H]−, 391.4661 [M−Glc−C8H18O−H]− |

| 11 | (20S)-Rg2 | 784.4967 | C42H72O13 | 783.4974 | 637.5124 [M−Rha−H]−, 619.5324 [M−Rha−H2O−H]−, 475.4133 [M−Glc−Rha−H]−, 391.3661 [M−Glc−Rha−C6H12−H]− |

| 12 | (20R)-Rg2 | 784.4967 | C42H72O13 | 783.4952 | 637.5121 [M−Rha−H]−, 619.5320 [M−Rha−H2O−H]−, 475.4134 [M−Glc−Rha−H]−, 391.3663 [M−Glc−Rha−C6H12−H]− |

| 13 | (20S)-Rh1 | 638.4388 | C36H62O9 | 637.4379 | 475.4260 [M−Glc−H]− |

| 14 | (20R)-Rh1 | 638.4388 | C36H62O9 | 637.4385 | 475.4261 [M−Glc−H]− |

| 15 | (20S, 25)-epoxy-Rg2 | 784.4967 | C42H72O13 | 784.4958 | 637.6121 [M−Rha−H]−, 619.6324 [M−Rha−H2O−H]−, 475.5131 [M−Glc−Rha−H]−, 417.5831 [M−Glc−Rha−C3H6O−H]−, 391.4 [M−Glc−Rha−C6H12−H]− |

| 16 | (20R, 25)-epoxy-Rg2 | 784.4967 | C42H72O13 | 783.4964 | 637.6121 [M−Rha−H]−, 619.6324 [M−Rha−H2O−H]−, 475.5131 [M−Glc−Rha−H]−, 417.5831 [M−Glc−Rha−C3H6O−H]−, 391.4 [M−Glc−Rha−C6H12−H]− |

| 17 | 25-OCH2CH3-Rg6 | 812.5280 | C44H76O13 | 811.5273 | 665.5441 [M−Rha−H]−, 647.5322 [M−Rha−H2O−H]−, 503.4433 [M−Glc−Rha−H]−, 457.4133 [M−Glc−Rha−CH3CH2OH−H]− |

| 18 | 25-OCH2CH3-F4 | 812.5280 | C44H76O13 | 811.5279 | 665.5443 [M−Rha−H]−, 647.5321 [M−Rha−H2O−H]−, 503.4431 [M−Glc−Rha−H]−, 457.4131 [M−Glc−Rha−CH3CH2OH−H]− |

| 19 | Rg6 | 766.4862 | C42H70O12 | 765.4842 | 619.5321 [M−Rha−H]−, 601.5550 [M−Rha−H2O−H]−, 457.4131 [M−Glc−Rha−H]− |

| 20 | F4 | 766.4862 | C42H70O12 | 765.4849 | 619.5324 [M−Rha−H]−, 601.5551 [M−Rha−H2O−H]−, 457.4133 [M−Glc−Rha−H]− |

| 21 | (20S)-OCH2CH3-Rg2 | 812.5280 | C44H76O13 | 811.5266 | 665.5443 [M−Rha−H]−, 647.5324 [M−Rha−H2O−H]−, 503.4432 [M−Glc−Rha−H]−, 457.4136 [M−Glc−Rha−CH3CH2OH−H]− |

| 22 | Rk3 | 620.4283 | C36H60O8 | 619.4269 | 457.4138 [M−Glc−H]− |

| 23 | (20R)-OCH2CH3-Rg2 | 812.5280 | C44H76O13 | 811.5265 | 665.5442 [M−Rha−H]−, 647.5321 [M−Rha−H2O−H]−, 503.4430 [M−Glc−Rha−H]−, 457.4134 [M−Glc−Rha−CH3CH2OH−H]− |

| 24 | Rh4 | 620.4283 | C36H60O8 | 619.4274 | 457.4133 [M−Glc−H]− |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, Q.; Chang, Y.; Li, B.; Zhang, Z.; Zhao, M.; Zhao, H.; Xiu, Y. Catalytic Transformation of Ginsenoside Re over Mesoporous Silica-Supported Heteropoly Acids: Generation of Diverse Rare Ginsenosides in Aqueous Ethanol Revealed by HPLC-HRMSn. Molecules 2025, 30, 4753. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244753

Wang Q, Chang Y, Li B, Zhang Z, Zhao M, Zhao H, Xiu Y. Catalytic Transformation of Ginsenoside Re over Mesoporous Silica-Supported Heteropoly Acids: Generation of Diverse Rare Ginsenosides in Aqueous Ethanol Revealed by HPLC-HRMSn. Molecules. 2025; 30(24):4753. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244753

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Qi, Yanyan Chang, Bing Li, Zhenxuan Zhang, Mengya Zhao, Huanxi Zhao, and Yang Xiu. 2025. "Catalytic Transformation of Ginsenoside Re over Mesoporous Silica-Supported Heteropoly Acids: Generation of Diverse Rare Ginsenosides in Aqueous Ethanol Revealed by HPLC-HRMSn" Molecules 30, no. 24: 4753. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244753

APA StyleWang, Q., Chang, Y., Li, B., Zhang, Z., Zhao, M., Zhao, H., & Xiu, Y. (2025). Catalytic Transformation of Ginsenoside Re over Mesoporous Silica-Supported Heteropoly Acids: Generation of Diverse Rare Ginsenosides in Aqueous Ethanol Revealed by HPLC-HRMSn. Molecules, 30(24), 4753. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244753