Acetylenic Fatty Acids and Stilbene Glycosides Isolated from Santalum yasi Collected from the Fiji Islands

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

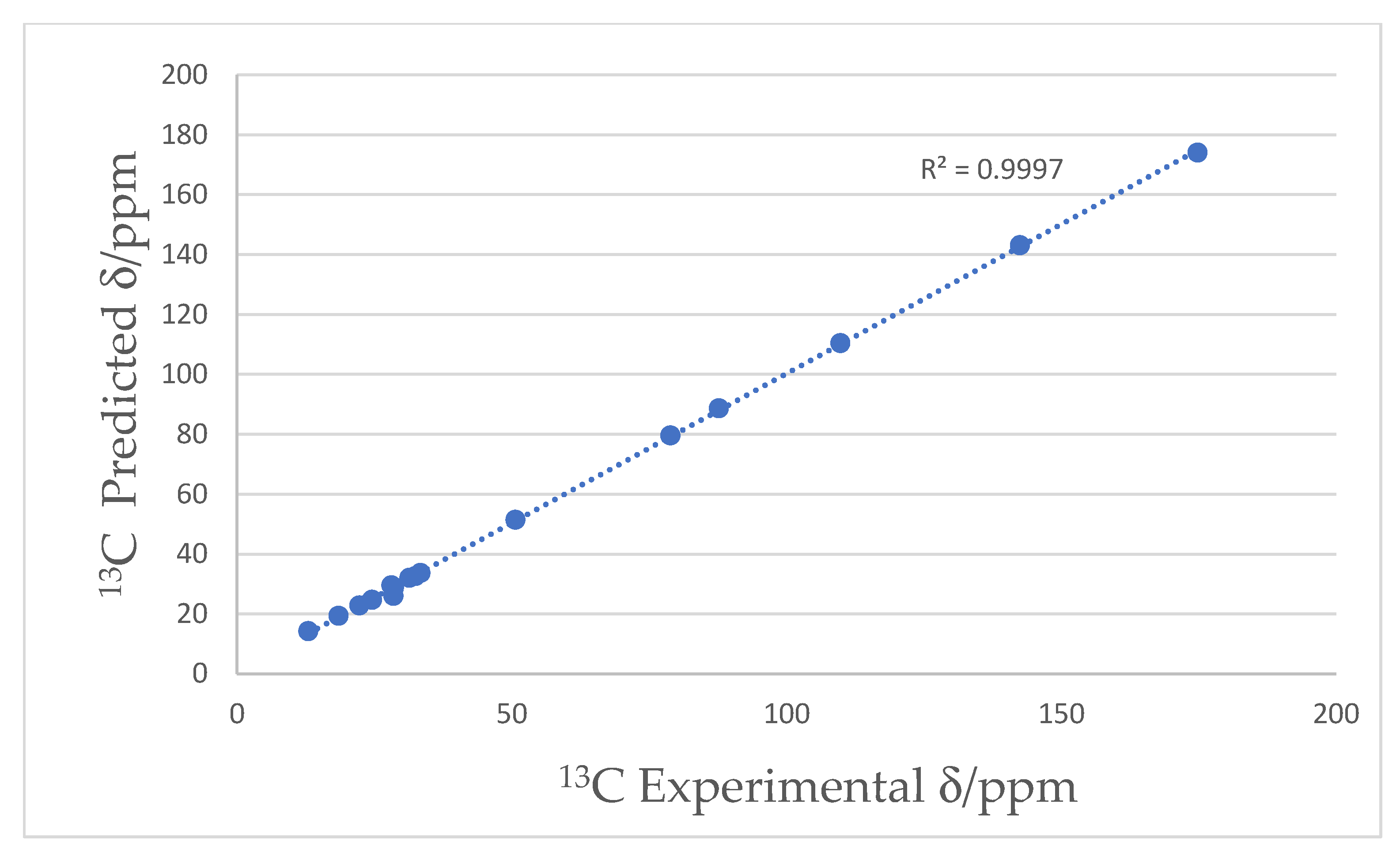

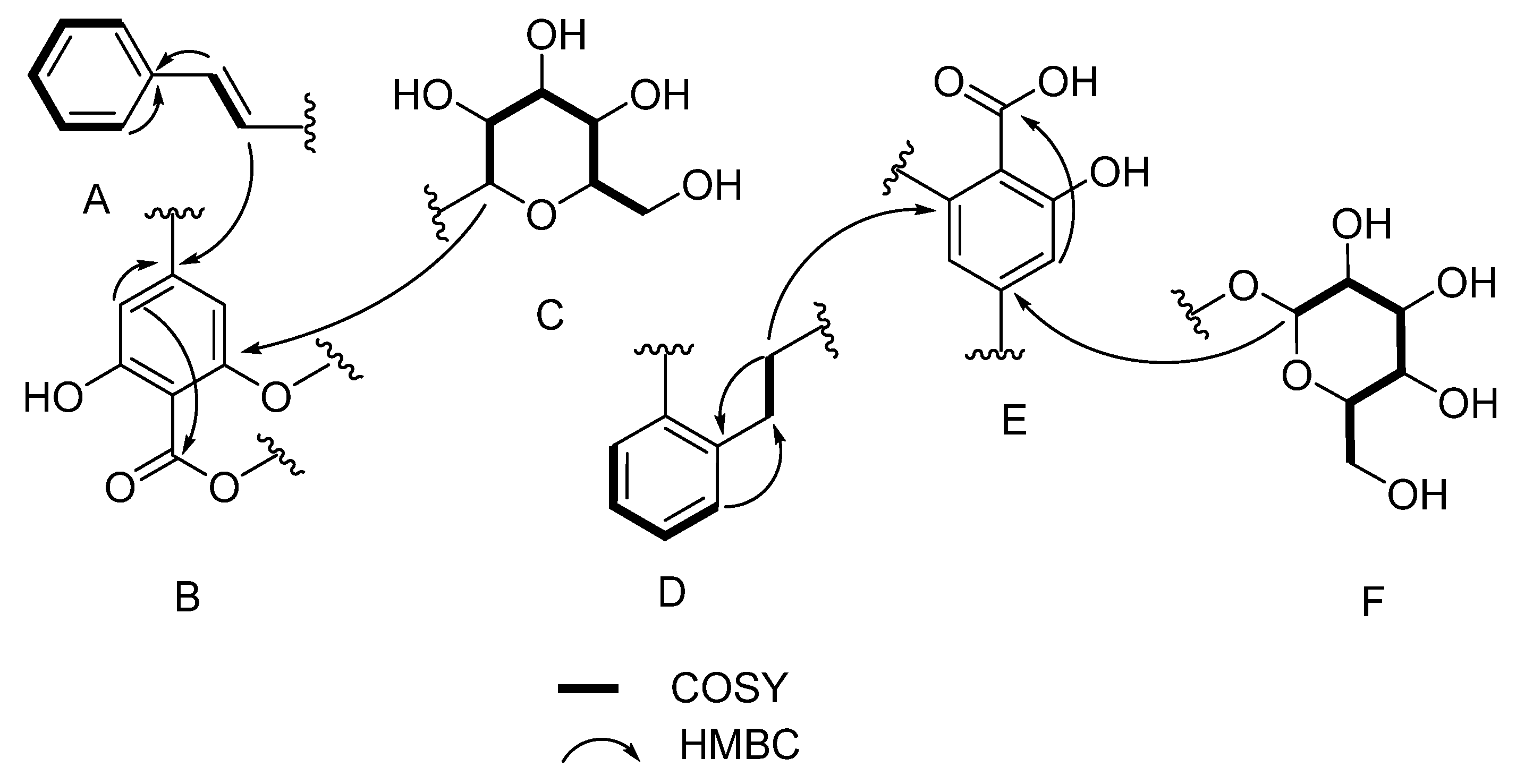

2.1. Structure Elucidation

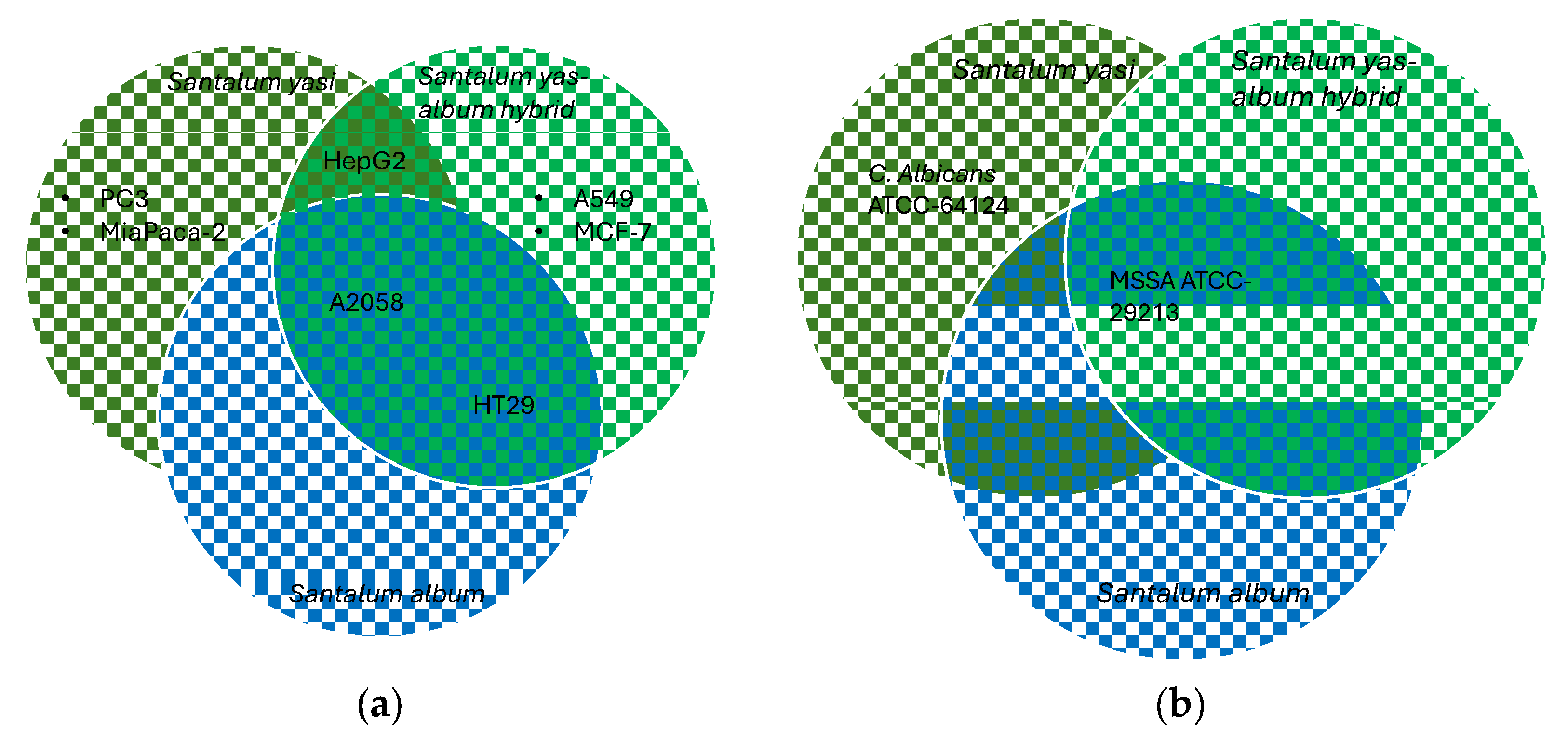

2.2. Biological Activity

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Reagents and Solvents

3.2. Main Instruments

3.3. Chromatography

3.4. Plant Collection and Extraction

3.5. Purification and Isolation

3.6. Cytotoxicity Assays

3.7. Antimicrobial Assays

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Diaz-Chavez, M.L.; Moniodis, J.; Madilao, L.L.; Jancsik, S.; Keeling, C.I.; Barbour, E.L.; Ghisalberti, E.L.; Plummer, J.A.; Jones, C.G.; Bohlmann, J. Biosynthesis of Sandalwood Oil: Santalum Album CYP76F Cytochromes P450 Produce Santalols and Bergamotol. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e75053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boruah, T.; Parashar, P.; Ujir, C.; Dey, S.K.; Nayik, G.A.; Ansari, M.J.; Nejad, A.S.M. Chapter 6—Sandalwood Essential Oil. In Essential Oils; Nayik, G.A., Ansari, M.J., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2023; pp. 121–145. ISBN 978-0-323-91740-7. [Google Scholar]

- Santalum, L. Plants of the World Online|Kew Science. Available online: http://powo.science.kew.org/taxon/urn:lsid:ipni.org:names:30113685-2 (accessed on 31 March 2025).

- Parham, J.W. Plants of the Fiji Islands. Available online: https://www.pemberleybooks.com/product/plants-of-the-fiji-islands/16584/ (accessed on 28 September 2024).

- Thomson, L.A.J.; Bush, D.; Lesubula, M. Participatory Value Chain Study for Yasi Sandalwood (Santalum yasi) in Fiji. Aust. For. 2020, 83, 227–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CSIRO Research Publications Repository—Publication. Available online: https://publications.csiro.au/publications/publication/PIcsiro:EP204211 (accessed on 29 September 2025).

- Solanki, N.S.; Chauhan, C.S.; Vyas, B.; Marothia, D. Santalum Album Linn: A Review. Int. J. PharmTech Res. 2015, 7, 629–640. [Google Scholar]

- (PDF) Assessing Genetic Diversity of Natural and Hybrid Populations of Santalum Yasi in Fiji and Tonga. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/299425345_Assessing_genetic_diversity_of_natural_and_hybrid_populations_of_Santalum_yasi_in_Fiji_and_Tonga (accessed on 23 March 2025).

- ThriftBooks Secrets of Fijian Medicine Book by Michael A Weiner. Available online: https://www.thriftbooks.com/w/secrets-of-fijian-medicine_unknown/22012057/ (accessed on 12 July 2025).

- Struthers, R.; Lamont, B.B.; Fox, J.E.D.; Wijesuriya, S.; Crossland, T. Mineral Nutrition of Sandalwood (Santalum spicatum). J. Exp. Bot. 1986, 37, 1274–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochi, T.; Shibata, H.; Higuti, T.; Kodama, K.; Kusumi, T.; Takaishi, Y. Anti- Helicobacter p ylori Compounds from Santalum album. J. Nat. Prod. 2005, 68, 819–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuttan, R.; Nair, N.G.; Radhakrishnan, A.N.; Spande, T.F.; Yeh, H.J.; Witkop, B. Isolation and Characterization of γ-L-Glutamyl-S-(Trans-1-Propenyl)-L-Cysteine Sulfoxide from Sandal (Santalum album). Interesting Occurrence of Sulfoxide Diastereoisomers in Nature. Biochemistry 1974, 13, 4394–4400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butaud, J.-F.; Raharivelomanana, P.; Bianchini, J.-P.; Gaydou, E.M. Santalum Insulare Acetylenic Fatty Acid Seed Oils: Comparison within the Santalum Genus. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 2008, 85, 353–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howes, M.-J.R.; Simmonds, M.S.J.; Kite, G.C. Evaluation of the Quality of Sandalwood Essential Oils by Gas Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. A 2004, 1028, 307–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kupchan, S.M.; Stevens, K.L.; Rohlfing, E.A.; Sickles, B.R.; Sneden, A.T.; Miller, R.W.; Bryan, R.F. Tumor Inhibitors. 126. New Cytotoxic Neolignans from Aniba Megaphylla Mez. J. Org. Chem. 1978, 43, 586–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sephadex|Sigma-Aldrich. Available online: https://www.sigmaaldrich.com/GB/en/search/sephadex?focus=products&page=1&perpage=30&sort=relevance&term=sephadex&type=product (accessed on 23 March 2025).

- Fred, W.; McLafferty. Interpretation of Mass Spectra, Third Edition. University Science Books, Mill Valley, California, 1980. pp. Xvii + 303—White V—1982—Biological Mass Spectrometry—Wiley Online Library. Available online: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/bms.1200090610/abstract (accessed on 16 November 2016).

- Pellegrin, V. Molecular Formulas of Organic Compounds: The Nitrogen Rule and Degree of Unsaturation. J. Chem. Educ. 1983, 60, 626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CASE NMR Software|Structure Elucidator Suite. Available online: https://www.acdlabs.com/products/spectrus-platform/structure-elucidator-suite/ (accessed on 15 September 2023).

- Bremser, W. Hose—A Novel Substructure Code. Anal. Chim. Acta 1978, 103, 355–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elyashberg, M.; Williams, A. ACD/Structure Elucidator: 20 Years in the History of Development. Molecules 2021, 26, 6623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rateb, M.E.; Tabudravu, J.; Ebel, R. NMR Characterisation of Natural Products Derived from Under-Explored Microorganisms. In Nuclear Magnetic Resonance; Ramesh, V., Ed.; Royal Society of Chemistry: Cambridge, UK, 2016; Volume 45, pp. 240–268. ISBN 978-1-78262-053-2. [Google Scholar]

- Mass Spec Fragment Prediction Software|MS FragmenterTM. ACD/Labs. Available online: http://www.acdlabs.com (accessed on 29 September 2025).

- Elyashberg, M.E.; Williams, A.; Blinov, K. Contemporary Computer-Assisted Approaches to Molecular Structure Elucidation; New Developments in NMR; The Royal Society of Chemistry: London, UK, 2012; ISBN 978-1-84973-432-5. [Google Scholar]

- Roos, C.B.; Chiang, C.-H.; Murray, L.A.M.; Yang, D.; Schulert, L.; Narayan, A.R.H. Stereodynamic Strategies to Induce and Enrich Chirality of Atropisomers at a Late Stage. Chem. Rev. 2023, 123, 10641–10727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smyth, J.E.; Butler, N.M.; Keller, P.A. A Twist of Nature—The Significance of Atropisomers in Biological Systems. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2015, 32, 1562–1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- PerkinElmer ChemDraw Professional. Get the Software Safely and Easily. Available online: https://perkinelmer-chemdraw-professional.software.informer.com/16.0/ (accessed on 29 March 2025).

- Fragkiadakis, M.; Thomaidi, M.; Stergiannakos, T.; Chatziorfanou, E.; Gaidatzi, M.; Michailidis Barakat, A.; Stoumpos, C.; Neochoritis, C.G. High Rotational Barrier Atropisomers. Chem.—A Eur. J. 2024, 30, e202401461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanman, B.A.; Parsons, A.T.; Zech, S.G. Addressing Atropisomerism in the Development of Sotorasib, a Covalent Inhibitor of KRAS G12C: Structural, Analytical, and Synthetic Considerations. Acc. Chem. Res. 2022, 55, 2892–2903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, D.; Taylor, R.J.; Ferguson, G.; Tonge, A. Origins of the Proton NMR Chemical Shift Non-Equivalence in the Diastereotopic Methylene Protons of Camphanamides. Tetrahedron 1986, 42, 617–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PubChem Methyl (11E,13E)-Octadeca-11,13-Dien-9-Ynoate. Available online: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/92040344 (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- Methyl 9,11-Octadecadiynoate—PubChem—CompoundNCBI. Available online: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/14957561 (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- Askari, A.; Worthen, L.R.; Shimizu, Y. Gaylussacin, a New Stilbene Derivative from Species of Gaylussacia. Lloydia 1972, 35, 49–54. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chrysin-7beta-Monoglucoside—PubChem Compound—NCBI. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pccompound/?term=chrysin+monoglucoside (accessed on 23 March 2025).

- Chrysin-7beta-Monoglucoside—Chemical Compound|PlantaeDB. Available online: https://plantaedb.com/compounds/chrysin-7beta-monoglucoside (accessed on 23 March 2025).

- PubChem Neoschaftoside. Available online: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/442619 (accessed on 23 March 2025).

- Besson, E.; Chopin, J.; Markham, K.R.; Mues, R.; Wong, H.; Bouillant, M.-L. Identification of Neoschaftoside as 6-C-β-d-Glucopyranosyl-8-C-β-l-Arabinopyranosylapigenin. Phytochemistry 1984, 23, 159–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PubChem Chrysin 6-C-Glucoside 8-C-Arabinoside. Available online: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/21722007 (accessed on 23 March 2025).

- Lab Equipment and Lab Supplies | Fisher Scientific. Available online: https://www.fishersci.co.uk/gb/en/home.html (accessed on 19 June 2023).

- Stable Isotopes, NMR Solvents and Tubes. Available online: https://www.ukisotope.com/ (accessed on 13 June 2025).

- LC/MS Instruments, HPLC MS, LC/MS Systems, LC/MS Analysis|Agilent. Available online: https://www.agilent.com/en/product/liquid-chromatography-mass-spectrometry-lc-ms/lc-ms-instruments/quadrupole-time-of-flight-lc-ms (accessed on 8 August 2023).

- FTIR Spectroscopy. Available online: https://www.shimadzu.com/an/products/molecular-spectroscopy/ftir/index.html (accessed on 13 June 2025).

- University of Edinburgh—Connect NMR UK. Available online: https://www.connectnmruk.ac.uk/facility/edinburgh-university/ (accessed on 26 January 2025).

- Marine Biodiscovery. The School of Natural and Computing Sciences. The University of Aberdeen. Available online: https://www.abdn.ac.uk/ncs/departments/chemistry/research/marine-biodiscovery/ (accessed on 23 March 2025).

- High Sensitivity MS, High Sensitivity Ion Source, Jet Stream|Agilent. Available online: https://www.agilent.com/en/product/liquid-chromatography-mass-spectrometry-lc-ms/lc-ms-ion-sources/jet-stream-technology-ion-source-ajs (accessed on 11 November 2024).

- Robust Mass Spectrometry Application Software, MassHunter|Agilent. Available online: https://www.agilent.com/en/product/software-informatics/mass-spectrometry-software (accessed on 29 September 2025).

- Phenomenex UHPLC, HPLC, SPE, GC—Leader in Analytical Chemistry Solutions. Available online: https://www.phenomenex.com/?gclid=EAIaIQobChMIlYLs75LP_wIVw9_tCh0eAgYsEAAYASAAEgJA4PD_BwE (accessed on 19 June 2023).

- G1969-85000|Agilent. Available online: https://www.agilent.com/store/productDetail.jsp?catalogId=G1969-85000 (accessed on 11 November 2024).

- Quadrupole Spectrometer—maXis IITM—Bruker Daltonics—TOF-MS/MS/MS/for Pharmaceutical Applications. Available online: https://www.directindustry.com/prod/bruker-daltonics/product-30029-991983.html (accessed on 30 March 2025).

- Moore, P.M. Gel Filtration Chromatography. In Adsorption: Science and Technology; Rodrigues, A.E., LeVan, M.D., Tondeur, D., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1989; pp. 561–576. ISBN 978-94-009-2263-1. [Google Scholar]

- Solid Phase Extraction (SPE) Method Development Tool from Phenomenex. Available online: https://www.phenomenex.com/Tools/SPEMethodDevelopment (accessed on 10 January 2017).

- Google Maps. Available online: https://www.google.com/maps/place/Koronivia/@-18.0499986,178.5127337,8040m/data=!3m1!1e3!4m14!1m7!3m6!1s0x6e1be1dc6b6b9e01:0x3298dfc740562b9!2sKoronivia!8m2!3d-18.05!4d178.5333333!16s%2Fg%2F11cnyr0crw!3m5!1s0x6e1be1dc6b6b9e01:0x3298dfc740562b9!8m2!3d-18.05!4d178.5333333!16s%2Fg%2F11cnyr0crw?entry=ttu (accessed on 31 October 2023).

- The Institute of Applied Sciences—The Institute of Applied Sciences. Available online: https://www.usp.ac.fj/the-institute-of-applied-sciences/ (accessed on 23 March 2025).

- South Pacific Regional Herbarium and Biodiversity Centre. Available online: https://www.usp.ac.fj/the-institute-of-applied-sciences/south-pacific-regional-herbarium-and-biodiversity-centre/ (accessed on 14 October 2023).

- Tabudravu, J.N.; Jaspars, M. Stelliferin Riboside, a Triterpene Monosaccharide Isolated from the Fijian Sponge Geodia globostellifera. J. Nat. Prod. 2001, 64, 813–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schlüter, L.; Hansen, K.Ø.; Isaksson, J.; Andersen, J.H.; Hansen, E.H.; Kalinowski, J.; Schneider, Y.K.-H. Discovery of Thiazostatin D/E Using UPLC-HR-MS2-Based Metabolomics and σ-Factor Engineering of Actinoplanes sp. SE50/110. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2024, 12, 1497138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basic Colorimetric Proliferation Assays: MTT, WST, and Resazurin. Springer Nature Experiments. Available online: https://experiments.springernature.com/articles/10.1007/978-1-4939-6960-9_1 (accessed on 30 March 2025).

- Koagne, R.R.; Annang, F.; Cautain, B.; Martín, J.; Pérez-Moreno, G.; Bitchagno, G.T.M.; González-Pacanowska, D.; Vicente, F.; Simo, I.K.; Reyes, F.; et al. Cytotoxycity and Antiplasmodial Activity of Phenolic Derivatives from Albizia Zygia (DC.) J.F. Macbr. (Mimosaceae). BMC Complement Med. Ther. 2020, 20, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audoin, C.; Bonhomme, D.; Ivanisevic, J.; Cruz, M.D.l.; Cautain, B.; Monteiro, M.C.; Reyes, F.; Rios, L.; Perez, T.; Thomas, O.P. Balibalosides, an Original Family of Glucosylated Sesterterpenes Produced by the Mediterranean Sponge Oscarella balibaloi. Mar. Drugs 2013, 11, 1477–1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vickery, J.R.; Whitfield, F.B.; Ford, G.L.; Kennett, B.H. Ximenynic Acid in Santalum obtusifolium Seed Oil. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 1984, 61, 890–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, F.; Hettiarachchi, D.; Hu, X.; Singh, A.; Liu, Y.; Sunderland, B. Chapter 20—Ximenynic Acid and Its Bioactivities. In Advances in Dietary Lipids and Human Health; Li, D., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2022; pp. 303–328. ISBN 978-0-12-823914-8. [Google Scholar]

- XYMENYNIC ACID—Cosmetics Ingredient INCI. Available online: https://cosmetics.specialchem.com/inci-ingredients/xymenynic-acid (accessed on 25 May 2025).

- El-Jaber, N.; Estévez-Braun, A.; Ravelo, A.G.; Muñoz-Muñoz, O.; Rodríguez-Afonso, A.; Murguia, J.R. Acetylenic Acids from the Aerial Parts of Nanodea muscosa. J. Nat. Prod. 2003, 66, 722–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.-C.; Jacob, M.R.; ElSohly, H.N.; Nagle, D.G.; Smillie, T.J.; Walker, L.A.; Clark, A.M. Acetylenic Acids Inhibiting Azole-Resistant Candida Albicans from Pentagonia gigantifolia. J. Nat. Prod. 2003, 66, 1132–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.-C.; Jacob, M.R.; Khan, S.I.; Ashfaq, M.K.; Babu, K.S.; Agarwal, A.K.; ElSohly, H.N.; Manly, S.P.; Clark, A.M. Potent In Vitro Antifungal Activities of Naturally Occurring Acetylenic Acids. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2008, 52, 2442–2448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okada, S.; Zhou, X.-R.; Damcevski, K.; Gibb, N.; Wood, C.; Hamberg, M.; Haritos, V.S. Diversity of Δ12 Fatty Acid Desaturases in Santalaceae and Their Role in Production of Seed Oil Acetylenic Fatty Acids. J. Biol. Chem. 2013, 288, 32405–32413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sperling, P.; Lee, M.; Girke, T.; Zähringer, U.; Stymne, S.; Heinz, E. A Bifunctional Δ6-Fatty Acyl Acetylenase/Desaturase from the Moss Ceratodon Purpureus. Eur. J. Biochem. 2000, 267, 3801–3811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vierengel, A.; Kohn, G.; Vandekerkhove, O.; Hartmann, E. 9-Octadecen-6-Ynoic Acid from Riccia Fluitans. Phytochemistry 1987, 26, 2101–2102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acetylenic FA|Cyberlipid. Available online: https://cyberlipid.gerli.com/description/simple-lipids/fatty-acids/acetylenic-fa/ (accessed on 2 June 2025).

- Minto, R.E.; Blacklock, B.J. Biosynthesis and Function of Polyacetylenes and Allied Natural Products. Prog. Lipid Res. 2008, 47, 233–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ondeyka, J.G.; Zink, D.L.; Young, K.; Painter, R.; Kodali, S.; Galgoci, A.; Collado, J.; Tormo, J.R.; Basilio, A.; Vicente, F.; et al. Discovery of Bacterial Fatty Acid Synthase Inhibitors from a Phoma Species as Antimicrobial Agents Using a New Antisense-Based Strategy. J. Nat. Prod. 2006, 69, 377–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tobinaga, S.; Sharma, M.; Aalbersberg, W.; Watanabe, K.; Iguchi, K.; Narui, K.; Sasatsu, M.; Waki, S. Isolation and Identification of a Potent Antimalarial and Antibacterial Polyacetylene from Bidens pilosa. Planta Med. 2009, 75, 624–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, J.; Cerdeira, C.D.; Chavasco, J.M.; Cintra, A.B.P.; da Silva, C.B.P.; de Mendonça, A.N.; Ishikawa, T.; Boriollo, M.F.G.; Chavasco, J.K. In vitro screening antibacterial activity of Bidens pilosa linné and Annona crassiflora mart. against oxacillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus (ORSA) from the aerial environment at the dental clinic. Rev. Inst. Med. Trop. Sao Paulo 2014, 56, 333–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, Z.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, L.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Tian, Z. Bioactive Polyacetylenes from Bidens Pilosa L and Their Anti-Inflammatory Activity. Nat. Prod. Res. 2022, 36, 6353–6358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahamad, J.; Ismail, S.A.; Jalal, A.Z.; Akhtar, M.S.; Ahmad, J. Stilbenes in Breast Cancer Treatment: Nanostilbenes an Approach to Improve Therapeutic Efficacy. Pharmacol. Res. Nat. Prod. 2025, 6, 100173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.-H.; Chen, Y.-Y.; Yeh, Y.-L.; Wang, Y.-J.; Chen, R.-J. Stilbene Compounds Inhibit Tumor Growth by the Induction of Cellular Senescence and the Inhibition of Telomerase Activity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 2716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirerol, J.A.; Rodríguez, M.L.; Mena, S.; Asensi, M.A.; Estrela, J.M.; Ortega, A.L. Role of Natural Stilbenes in the Prevention of Cancer. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2016, 2016, 3128951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, J.; Jin, L.; Liu, H.; Hua, Z. Stilbenes: A Promising Small Molecule Modulator for Epigenetic Regulation in Human Diseases. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1326682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piekuś-Słomka, N.; Mikstacka, R.; Ronowicz, J.; Sobiak, S. Hybrid Cis-Stilbene Molecules: Novel Anticancer Agents. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breast Cancer Prevention: Tamoxifen and Raloxifene. Available online: https://www.cancer.org/cancer/types/breast-cancer/risk-and-prevention/tamoxifen-and-raloxifene-for-breast-cancer-prevention.html (accessed on 24 May 2025).

| Pos. | δC, Type | δH (J in Hz) | COSY 1H−1H | HMBC 1H→13C |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 174.8, C | |||

| 2 | 33.4, CH2 | 2.27, t, 7.6 | 3 | 1, 3, 4 |

| 3 | 24.6, CH2 | 1.56, t, 7.4 | 2, 4 | 1, 2, 4, 6 |

| 4 | 28.6, CH2 | 1.28, ovlp a | 3,4 | 6 |

| 5 | 32.5, CH2 | 2.02, m | 4, 6, 7 | 6, 5 |

| 6 | 142.5, CH | 5.92, m | 4,7 | 8 |

| 7 | 109.8, CH | 5.38, d, 15.7 | 5, 6, 5 | 9 |

| 8 | 78.9, C | |||

| 9 | 87.7, C | |||

| 10 | 18.5, CH2 | 2.20, t, 7.5 | 11 | 8, 9 |

| 11 | 28.5, CH2 | 1.45, ovlp | 10 | 9 |

| 12 | 28.4, CH2 | 1.36, ovlp | 11, 13 | 10 |

| 13 | 28.3, CH2 | 1.32, ovlp | 12, 14 | |

| 14 | 28.2, CH2 | 1.28, ovlp | 13,15 | |

| 15 | 28.1, CH2 | 1.29, ovlp | 14,16 | |

| 16 | 31.4, CH2 | 1.24, ovlp | 15, 17 | 15, 17 |

| 17 | 22.3, CH2 | 1.26, ovlp | 16,17 | 18 |

| 18 | 13.0, CH3 | 0.85, t, 7.02 | 17, 19 | 16, 17, 31 |

| 19 | 50.7, CH3 | 3.60, s | 18 | 1 |

| Pos | δC, a Type | δH (J/Hz) | COSY 1H−1H | HMBC 1H→13C |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 172.9, C | |||

| 2 | 106.4, C | |||

| 3 | 164.7, C | |||

| 4 | 101.8, CH | 6.50, d, 7.4 | 1, 3, 5 | |

| 5 | 161.5, C | |||

| 6 | 111.0, CH | 6.46, d, 2.3 | 1, 5, 7 | |

| 7 | 147.1, C | |||

| 8 | 38.5, CH2 | A: 3.20, m | 9 | 2, 6, 7, 10 |

| B: 3.17, m | 9 | 2, 7,10 | ||

| 9 | 37.9, CH2 | A: 2.89, m | 8A, 8B | 7, 10 |

| B: 2.85, m | 8A, 8B | 7, 10 | ||

| 10 | 142.0, C | |||

| 11 | 128.2, CH | 7.22, d, 8.0 | 12 | 10, 12, 15 |

| 12 | 125.6, CH | 7.17, t, 7.7 | 11 | 13 |

| 13 | 128.0, CH | 7.26, t, 8.0 | 14 | 12, 15 |

| 14 | 127.6, CH | 7.17, d, 8.0 | 13 | 12, 15 |

| 15 | 151.5, C | |||

| 16 | 172.7, C | |||

| 17 | 106.2, C | |||

| 18 | 164.0 C | |||

| 19 | 102.9, CH | 6.60, d, 2.3 | 21 | 16, 17, 18, 21, 23 |

| 20 | 142.8, C | |||

| 21 | 107.4, CH | 6.92, d, 2.2 | 19 | 16, 17, 19, 22, 23 |

| 22 | 161.6, C | |||

| 23 | 128.9, CH | 6.91, d, 16.0 | 24 | 19, 20 |

| 24 | 130.8, CH | 7.98, d, 16.0 | 23 | 20, 24 |

| 25 | 137.6, C | |||

| 26/30 | 126.3, CH | 7.52, d, 8.0 | 28 | 25, 27, 28 |

| 27/29 | 129.0, CH | 6.95, d, 8.0 | 28 | 25, 28 |

| 28 | 128.0, CH | 7.35, d, 8.0 | 27/29, 26/30 | |

| 1′ | 99.9, CH | 4.74, d, 7.0 | 2′ | 2′, 5 |

| 2′ | 73.4 CH | 3.49, m | 1′, 3′ | |

| 3′ | 76.8, CH | 3.39, m | 2′, 4′ | 2′ |

| 4′ | 69.8, CH | 3.48, m | 3′ | |

| 5′ | 76.5, CH | 3.44, m | 4′ | 5′ |

| 6′ | 61.0, CH2 | A: 3.91, dd, 11.8, 2.2 | 5′ | |

| B: 3.72, m | 5′ | |||

| 1″ | 100.1, CH | 5.05, d, 7.0 | 2″ | 22 |

| 2″ | 73.4, CH | 3.50, m | 1″, 4″ | 2″ |

| 3″ | 76.9, CH | 3.46, m | 2″, 4″ | |

| 4″ | 69.9, CH | 3.41, m | 3″ | 2″ |

| 5″ | 77.0, CH | 3.53, m | 4″, 6″A, 6″B | |

| 6″ | 61.1, CH2 | A: 3.93, dd, 11.8, 2.2 | 5″ | 5″ |

| B: 3.72, m | 5″ |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Maqbali, K.A.; Vuiyasawa, M.; Gube-Ibrahim, M.A.; Sewariya, S.; Balat, C.; Helland, K.; Garcia-Sorribes, T.; Cruz, M.d.l.; Cautain, B.; Andersen, J.H.; et al. Acetylenic Fatty Acids and Stilbene Glycosides Isolated from Santalum yasi Collected from the Fiji Islands. Molecules 2025, 30, 4752. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244752

Maqbali KA, Vuiyasawa M, Gube-Ibrahim MA, Sewariya S, Balat C, Helland K, Garcia-Sorribes T, Cruz Mdl, Cautain B, Andersen JH, et al. Acetylenic Fatty Acids and Stilbene Glycosides Isolated from Santalum yasi Collected from the Fiji Islands. Molecules. 2025; 30(24):4752. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244752

Chicago/Turabian StyleMaqbali, Khalid Al, Miriama Vuiyasawa, Mercy Ayinya Gube-Ibrahim, Shubham Sewariya, Clément Balat, Kirsti Helland, Tamar Garcia-Sorribes, Mercedes de la Cruz, Bastien Cautain, Jeanette Hammer Andersen, and et al. 2025. "Acetylenic Fatty Acids and Stilbene Glycosides Isolated from Santalum yasi Collected from the Fiji Islands" Molecules 30, no. 24: 4752. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244752

APA StyleMaqbali, K. A., Vuiyasawa, M., Gube-Ibrahim, M. A., Sewariya, S., Balat, C., Helland, K., Garcia-Sorribes, T., Cruz, M. d. l., Cautain, B., Andersen, J. H., Reyes, F., & Tabudravu, J. N. (2025). Acetylenic Fatty Acids and Stilbene Glycosides Isolated from Santalum yasi Collected from the Fiji Islands. Molecules, 30(24), 4752. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244752