Antibacterial Agent-Loaded, Novel In Situ Forming Implants Made with Poly(Isosorbide Sebacate) and Dimethyl Isosorbide as a Solvent for Periodontitis Treatment

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

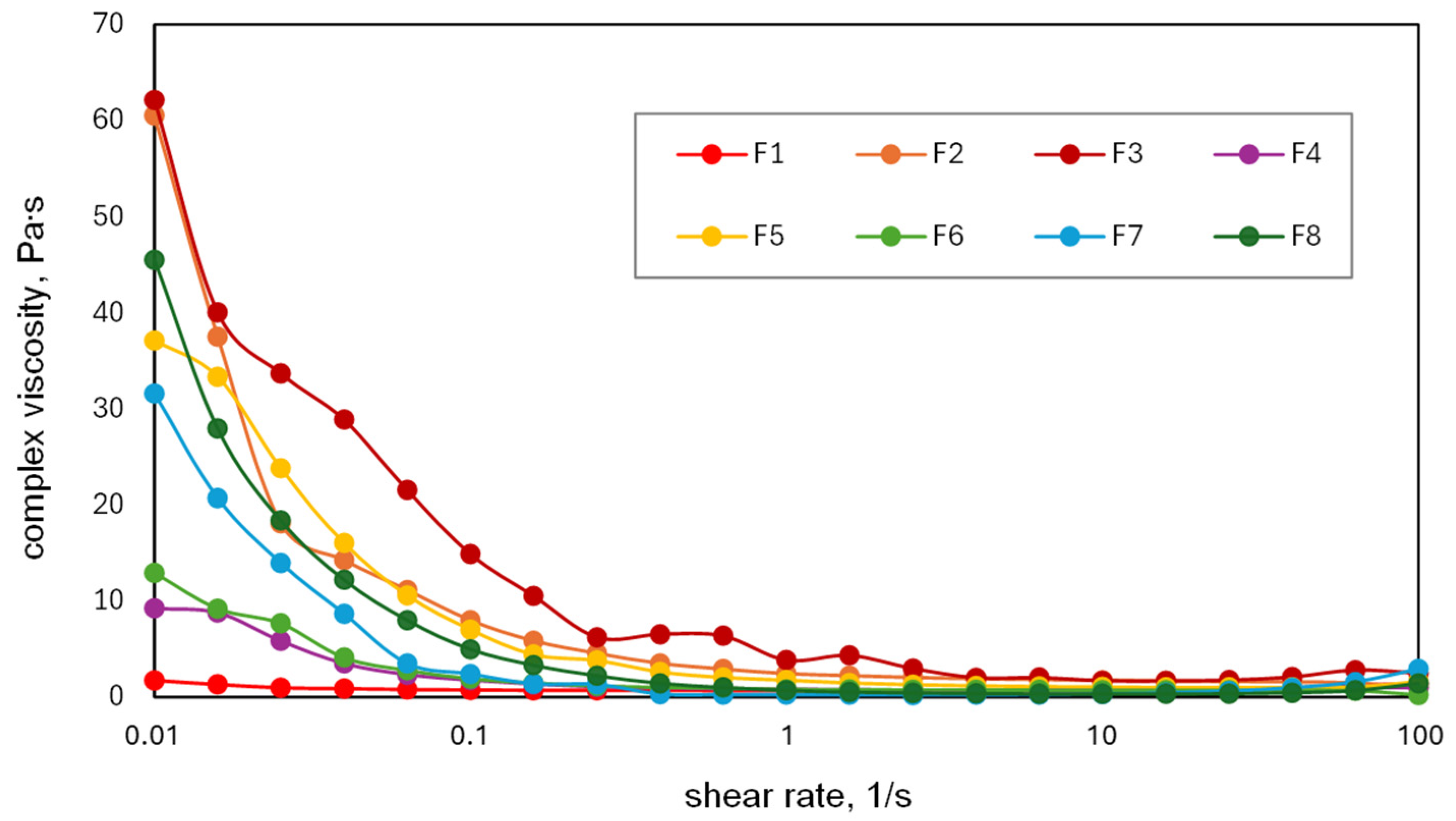

2.1. Preparation and Rheological Behavior of PISEB-Based Liquid Formulations

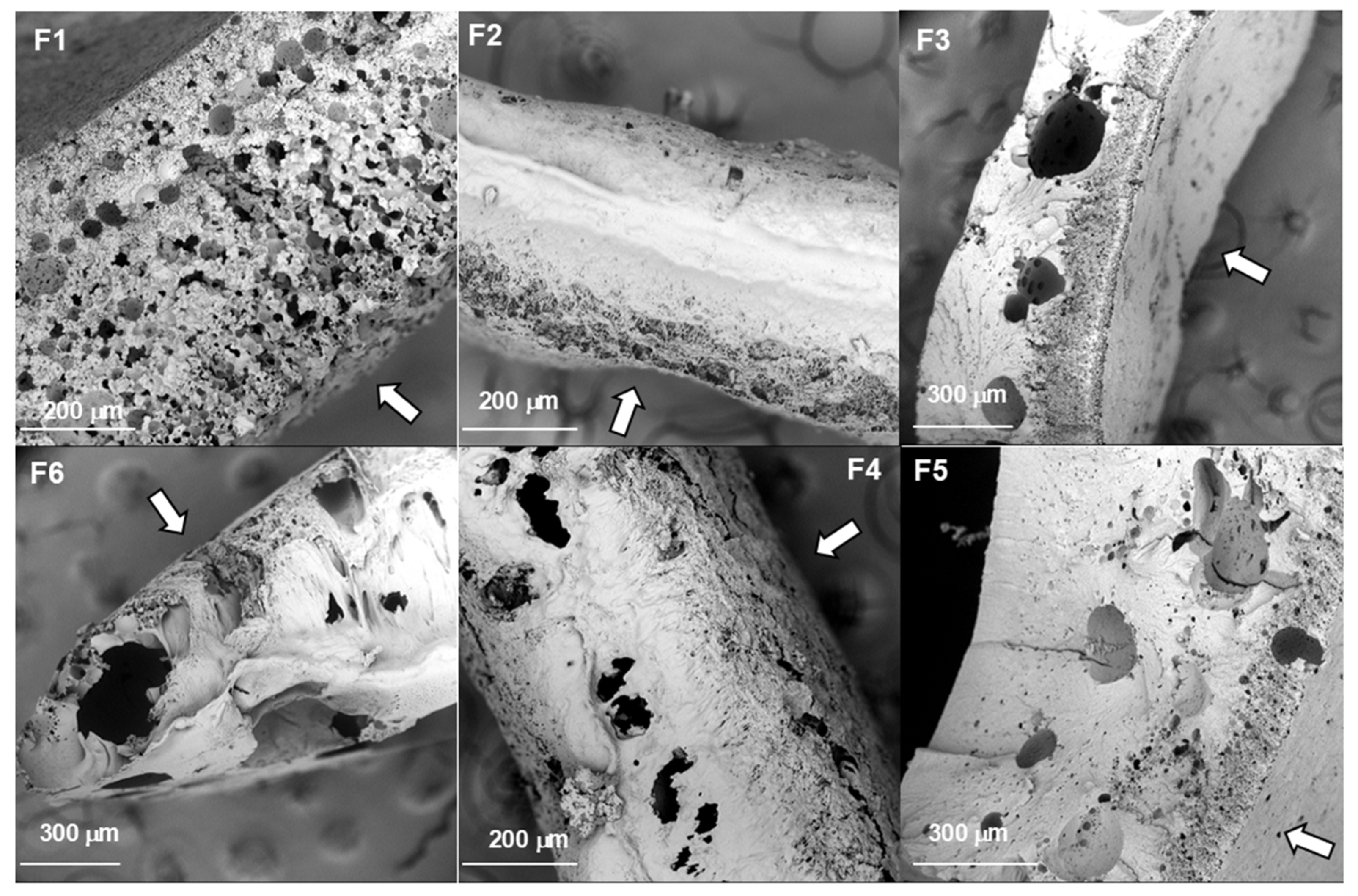

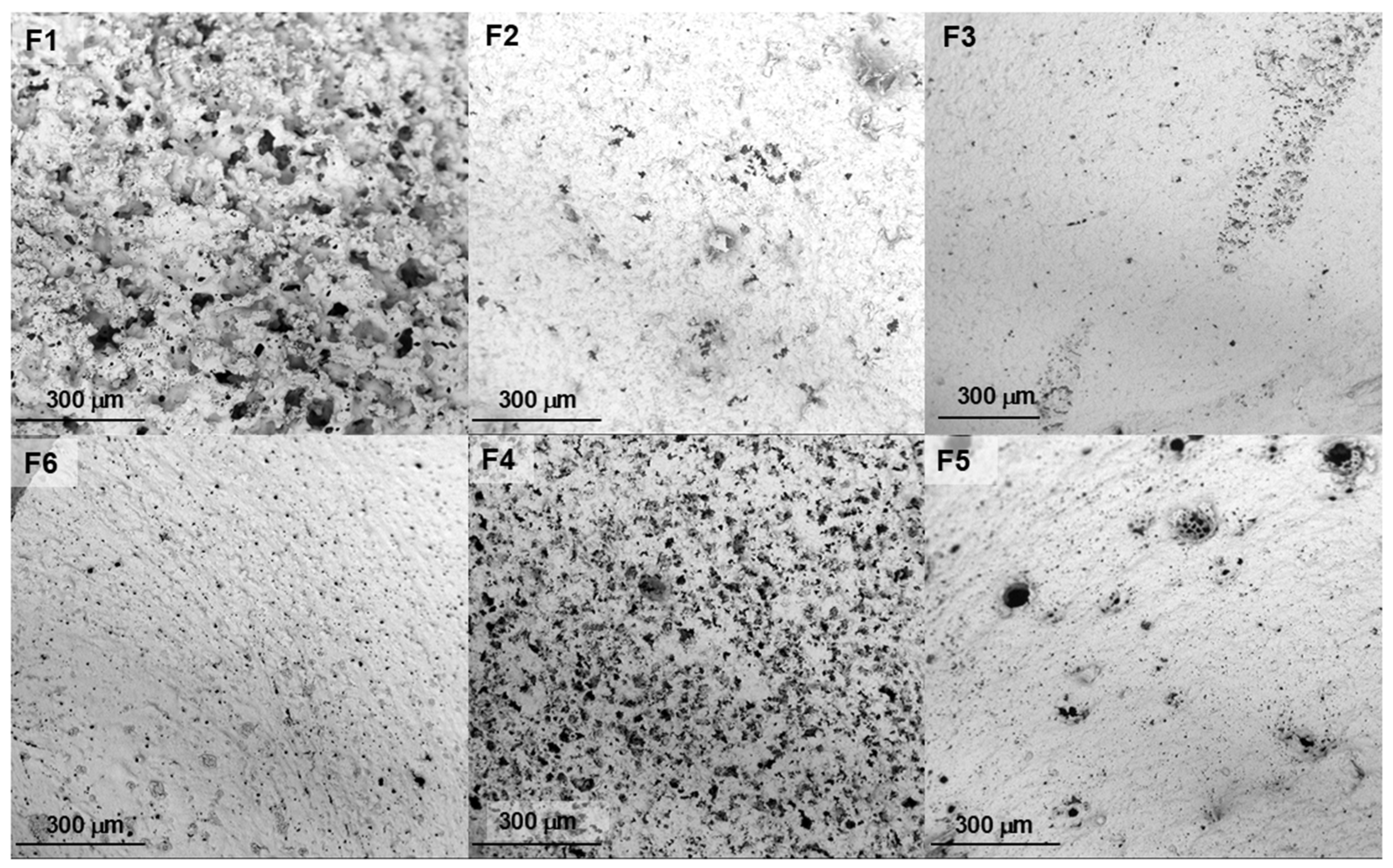

2.2. Morphology of the Implants

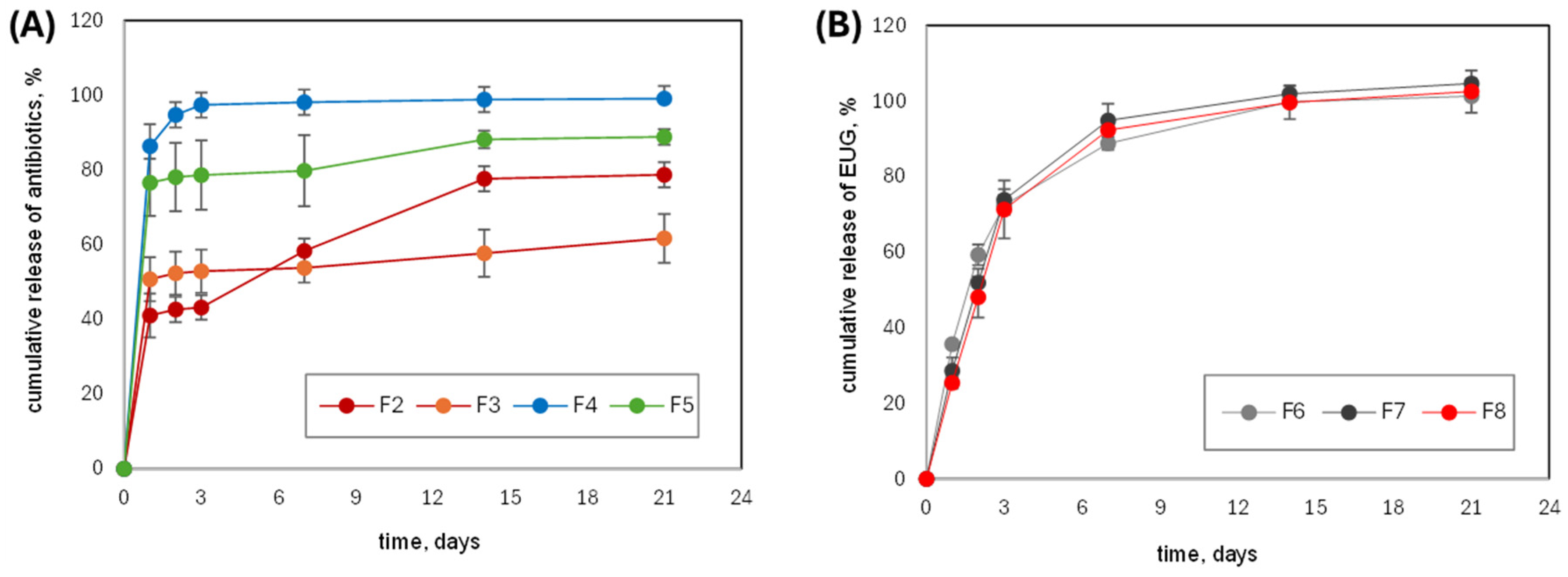

2.3. In Vitro Drug Release

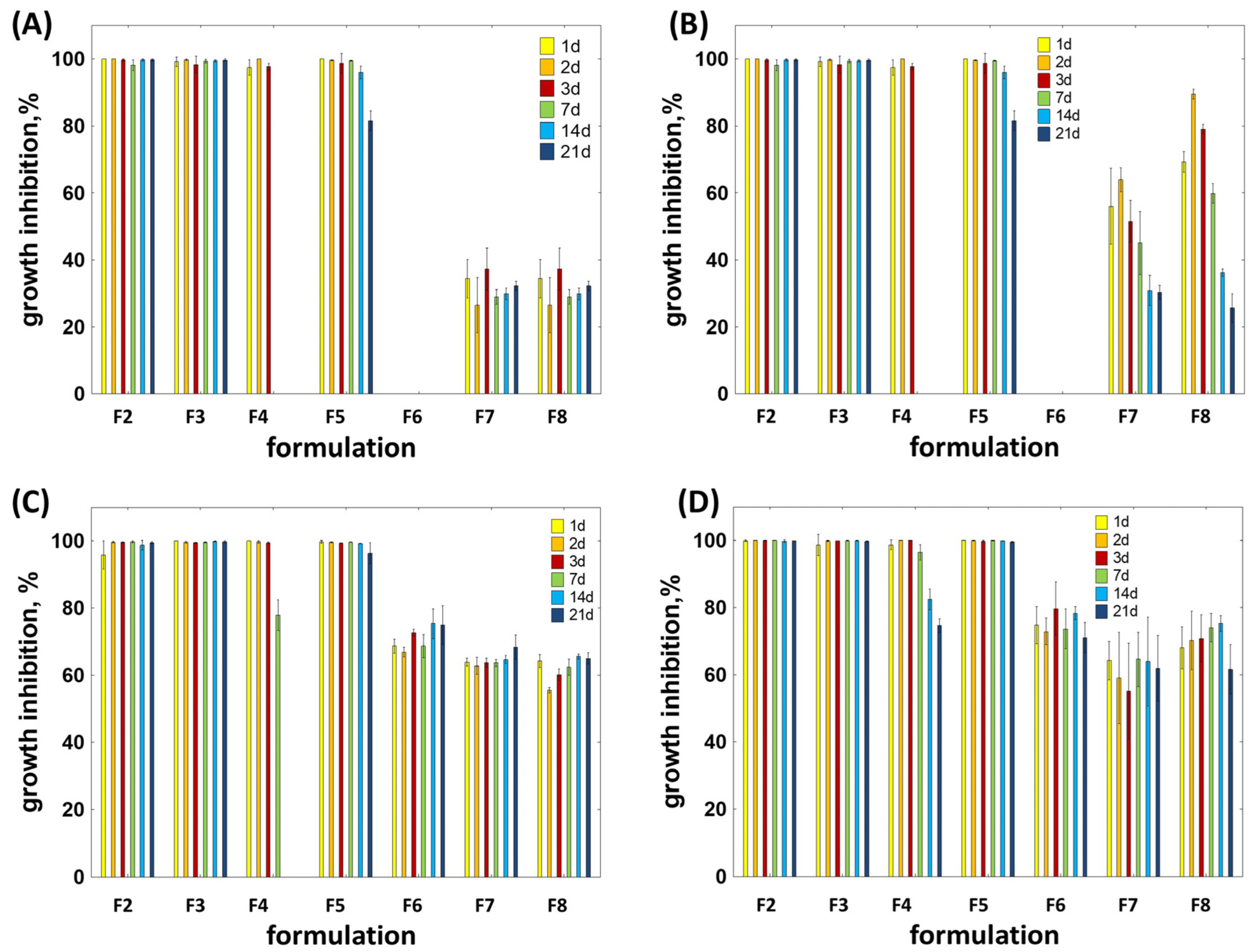

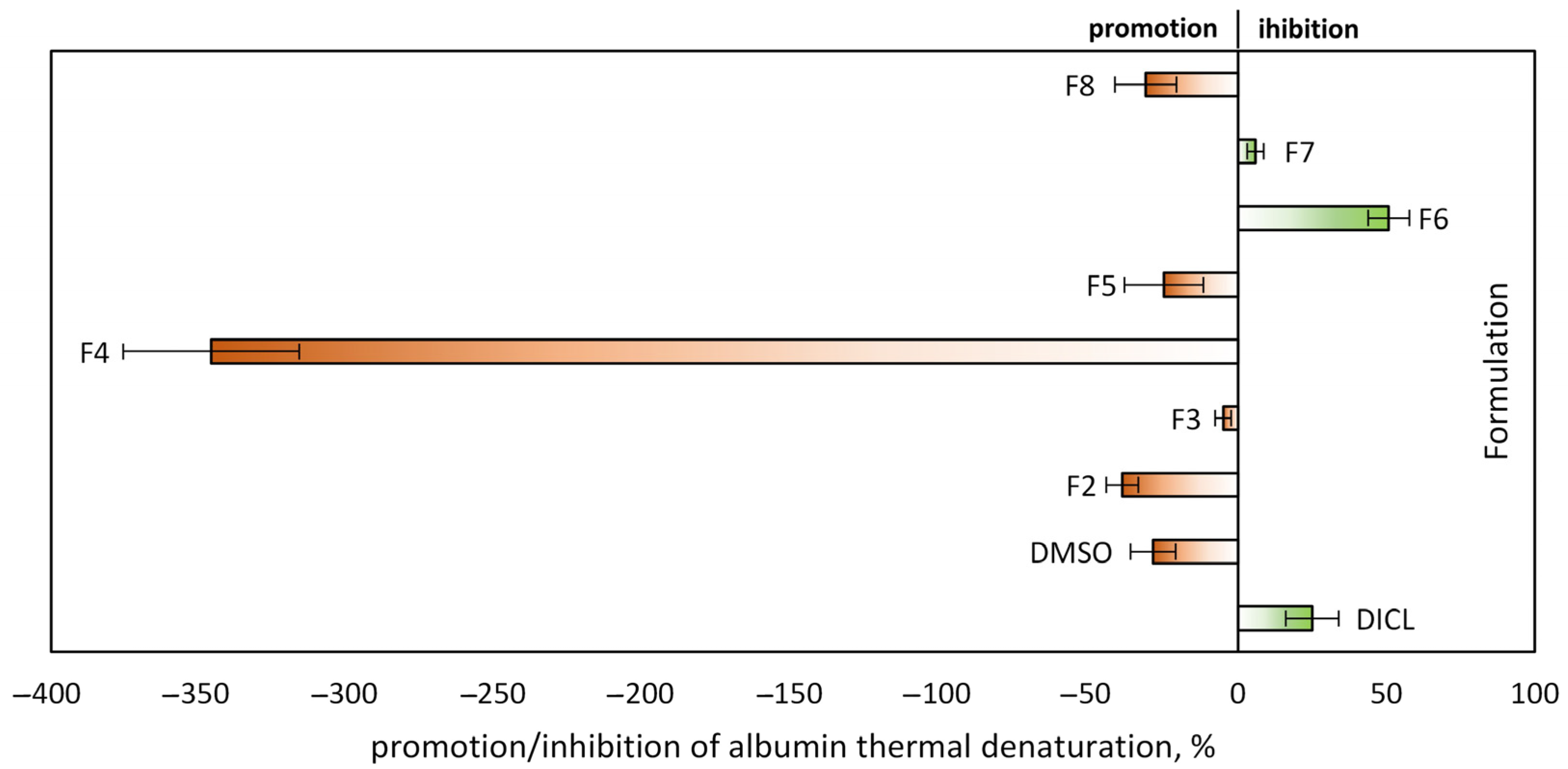

2.4. In Vitro Antibacterial and Inflammatory Potential

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Synthesis of Poly(Isosorbide Sebacate) (PISEB)

4.2. Preparation of PISEB-Based Formulation

4.3. Rheology

4.4. In Vitro Drug Release Study

4.5. Analysis of the in Vitro Release Kinetics

4.6. Characterization of PISEB and Precipitated Depots

4.7. In Vitro Antibacterial Activity Study

4.7.1. Microorganisms

4.7.2. Minimum Inhibitory Concentration Determination

4.7.3. Antibacterial Activity

4.7.4. Biofilm Formation

4.8. Anti-Inflammatory Test

4.9. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ATCC | American Type Culture Collection |

| CFU | Colony-forming units |

| DMI | Dimethyl isosorbide |

| DOXY | Doxycycline hyclate |

| EUG | Eugenol |

| IS | Isosorbide |

| ISFI | In situ forming implants |

| MIC | Minimum inhibitory concentration |

| MIN | Minocycline hydrochloride |

| PBS | Phosphate-buffered solution |

| PISEB | Poly(isosorbide sebacate) |

| PLA | Polylactide |

| PLGA | Poly(lactide-co-glycolide) |

References

- Pihlstrom, B.L.; Michalowicz, B.S.; Johnson, N.W. Periodontal diseases. Lancet 2005, 366, 1809–1820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benedyk-Machaczka, M.; Mydel, P.; Mäder, K.; Kaminska, M.; Taudte, N.; Naumann, M.; Kleinschmidt, M.; Sarembe, S.; Kiesow, A.; Eick, S.; et al. Preclinical Validation of MIN-T: A Novel Controlled-Released Formulation for the Adjunctive Local Application of Minocycline in Periodontitis. Antibiotics 2024, 13, 1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernebe, E.; GBD 2021 Oral Disorders Collaborators. Trends in the global, regional, and national burden of oral conditions from 1990 to 2021: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet 2025, 405, 897–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joshi, D.; Garg, T.; Goyal, A.K.; Rath, G. Advanced drug delivery approaches against periodontitis. Drug Deliv. 2016, 23, 363–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajeshwari, H.R.; Dhamecha, D.; Jagwani, S.; Rao, M.; Jadhav, K.; Shaikh, S.; Puzhankara, L.; Jalalpure, S. Local drug delivery systems in the management of periodontitis: A scientific review. J. Control. Release 2019, 307, 393–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Deng, Y.; Ma, S.; Ran, M.; Jia, Y.; Meng, J.; Han, F.; Gou, J.; Yin, T.; He, H.; et al. Local drug delivery systems as therapeutic strategies against periodontitis: A systematic review. J. Control. Release 2021, 333, 269–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, R.L.; English, J.P.; Cowsar, D.R.; Vanderbilt, D.P. Biodegradable In-Situ Forming Implants and Methods of Producing the Same. U.S. Patent US5990194A, 23 November 1999. Available online: https://patents.google.com/patent/US5990194A/en (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Wang, X.; Burgess, D.J. Drug release from in situ forming implants and advances in release testing. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2021, 178, 113912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakhrushina, E.O.; Titova, S.A.; Sakharova, P.S.; Plakhotnaya, O.N.; Grikh, V.V.; Patalova, A.R.; Gorbacheva, A.V.; Krasnyuk, I.I., Jr.; Krasnyuk, I.I. Phase-inversion in situ systems: Problems and prospects of biomedical application. Pharmaceutics 2025, 17, 750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandya, A.K.; Vora, L.K.; Umeyor, C.; Surve, D.; Patel, A.; Biswas, S.; Patel, K.; Patravale, V.B. Polymeric in situ forming depots for long-acting drug delivery systems. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2023, 200, 115003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, K.; Pack, D.W.; Klibanov, A.M.; Langer, R. Visual Evidence of Acidic Environment Within Degrading Poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) Microspheres. Pharm. Res. 2000, 17, 100–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houchin, M.L.; Topp, E.M. Chemical Degradation of Peptides and Proteins in PLGA: A Review of Reactions and Mechanisms. J. Pharm. Sci. 2008, 97, 2395–2404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ginjupalli, K.; Shavi, G.V.; Averineni, R.K.; Bhat, M.; Udupa, N.; Upadhya, P.N. Poly(α-hydroxy acid) based polymers: A review on material and degradation aspects. Polym. Degr. Stab. 2017, 144, 520–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinland, D.H.; van Putten, R.J.; Gruter, G.J.M. Evaluating the commercial application potential of polyesters with 1,4:3,6 dianhydrohexitols (isosorbide, isomannide and isoidide) by reviewing the synthetic challenges in step growth polymerization. Eur. Polym. J. 2022, 164, 110964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxon, D.J.; Luke, A.M.; Sajjad, H.; Tolman, W.B.; Reineke, T.M. Next-generation polymers: Isosorbide as a renewable alternative. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2020, 101, 101196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arico, F. Isosorbide as biobased platform chemical: Recent advances. Curr. Opin. Green Sust. 2020, 21, 82–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Śmiga-Matuszowicz, M.; Janicki, B.; Jaszcz, K.; Łukaszczyk, J.; Kaczmarek, M.; Lesiak, M.; Sieroń, A.L.; Simka, W.; Mierzwiński, M.; Kusz, D. Novel bioactive polyester scaffolds prepared from unsaturated resins based on isosorbide and succinic acid. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2014, 45, 64–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łukaszczyk, J.; Janicki, B.; López, A.; Skołucka, K.; Wojdyła, H.; Persson, C.; Piaskowski, S.; Śmiga-Matuszowicz, M. Novel injectable biomaterials for bone augmentation based on isosorbide dimethacrylic monomers. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2014, 40, 76–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Śmiga-Matuszowicz, M.; Korytkowska-Wałach, A.; Nowak, B.; Pilawka, R.; Lesiak, M.; Sieroń, A.L. Poly(isosorbide succinate) based in situ forming implants as potential systems for local drug delivery: Preliminary studies. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2018, 91, 311–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Śmiga-Matuszowicz, M.; Korytkowska-Wałach, A.; Nowak, B. Isosorbide-based polysebacates as polymeric components for development of in situ forming implants. Polym. Adv. Technol. 2019, 30, 1072–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Śmiga-Matuszowicz, M.; Włodarczyk, J.; Skorupa, M.; Czerwińska-Główka, D.; Fołta, K.; Pastusiak, M.; Adamiec-Organiściok, M.; Skonieczna, M.; Turczyn, R.; Sobota, M.; et al. Biodegradable scaffolds for vascular regeneration based on electrospun poly(L-lactide-co-glycolide)/poly(isosorbide sebacate) fibers. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, G.B.; Seo, J.I.; Gye, M.C.; Yoo, H.H. Isosorbide, a versatile green chemical: Elucidating its ADME properties for safe use. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2024, 272, 116051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tundo, P.; Aricò, F.; Gauthier, G.; Rossi, L.; Rosamilia, A.E.; Bevinakatti, H.S.; Sievert, R.L.; Newman, C.P. Green Synthesis of Dimethyl Isosorbide. ChemSusChem 2010, 3, 566–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arico, F.; Tundo, P. Isosorbide and dimethyl carbonate: A green match. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2016, 12, 2256–2266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russo, F.; Galiano, F.; Pedace, F.; Arico, F.; Figoli, A. Dimethyl Isosorbide As a Green Solvent for Sustainable Ultrafiltration and Microfiltration Membrane Preparation. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 659–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez d’Ayala, G.; Marino, T.; Bastos de Almeida, Y.M.; de Matos Costa, A.R.; Bezerra da Silva, L.; Argurio, P.; Laurienzo, P. Enhancing sustainability in PLA membrane preparation through the use of biobased solvents. Polymers 2024, 16, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Yang, X.; Meng, X.; Wang, L. Efficient pretreatment using dimethyl isosorbide as a biobased solvent for potential complete biomass valorization. Green Chem. 2022, 24, 4082–4094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Wang, Y.; Chen, L.; Wei, C.; Mu, T.; Xue, Z. Biobased dimethyl isosorbide as an efficient solvent for alkaline hydrolysis of waste polyethylene terephthalate to terephthalic acid. Green Chem. 2023, 25, 7807–7816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipp, R.; Gunther, C.; Riedl, J.; Tauber, U. Transdermal Therapeutic Systems That Contain Sex Steroids and Dimethyl Isosorbide. U.S. Patent 5,904,931, 18 May 1999. Available online: https://patents.google.com/patent/US5904931A/en (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Gers-Berlag, H.; Kroepke, R. Cosmetic and Dermatological Sunscreen Formulations Containing Triazine Derivatives and Dimethyl Isosorbide and Their Use. German Patent DE-19651055-B4, 16 March 2006. Available online: https://patents.google.com/patent/DE19651055B4/en (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Luzzi, L.A.; Ma, J.K.H. Dimethyl Isosorbide in Liquid Formulation of Aspirin. U.S. Patent 4,228,162, 14 October 1980. Available online: https://patents.google.com/patent/US4228162A/en (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Chen, J.L.; Battaglia, J.M. Topical and Other Type Pharmaceutical Formulations Containing Isosorbide Carrier. U.S. Patent 4,082,881, 4 April 1978. Available online: https://patents.google.com/patent/US4082881A/en (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Mottu, F.; Laurent, A.; Rüfenacht, D.A.; Doelker, E. Organic solvents for pharmaceutical parenterals and embolic liquids: A review of toxicity data. PDA J. Pharm. Sci. Technol. 2000, 54, 456–469. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mottu, F.; Gailloud, P.; Massuelle, D.; Rüfenacht, D.A.; Doelker, E. In vitro assessment of new embolic liquids prepared from preformed polymers and water-miscible solvents for aneurysm treatment. Biomaterials 2000, 21, 803–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrido-Mesa, N.; Zarzuelo, A.; Gálvez, J. Minocycline: Far Beyond an Antibiotic. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2013, 169, 337–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basegmez, C.; Berber, L.; Yalcin, F. Clinical and biochemical efficacy of minocycline in nonsurgical periodontal therapy: A randomized controlled pilot study. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2011, 51, 915–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomes, P.S.; Fernandes, M.H. Effect of therapeutic levels of doxycycline and minocycline in the proliferation and differentiation of human bone marrow osteoblastic cells. Arch. Oral Biol. 2007, 52, 251–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juvekar, S.; Kathpalia, H. Solvent removal precipitation based in situ forming implant for controlled drug delivery in periodontitis. J. Control. Release 2017, 251, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farzinnia, G.; Anvari, Y.S.; Siqueira, M.F. Antimicrobial Resistance in Oral Healthcare: A Growing Concern in Dentistry. Dent. J. 2025, 13, 391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerova-Vatsova, T.; Yotsova, R.; Parushev, I. Systemic Antibiotics in Periodontal Therapy: A Double-Edged Sword. Med. Inform. 2024, 11, 1950–1957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, M.V.; da Conceiçao Alves de Lima, A.; Silva, M.G.; Caetano, V.F.; de Andrade, M.F.; Casanova da Silva, R.G.; Pessoa Timeni de Moraes Filho, L.E.; de Lima Silva, I.D.; Vinhas, G.M. Clove essential oil and eugenol: A review of their significance and uses. Food Biosci. 2024, 62, 105112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, T.A.N.; dos Santos, G.A.; dos Santos, C.T.; Soares, D.C.F.; Saraiva, M.F.; Leal, D.H.S.; Sachs, D.; Ribeiro, T.A.N. Eugenol as a promising antibiofilm and anti-quorum sensing agent: A systematic review. Microbial Pathog. 2024, 196, 106937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulanowska, M.; Olas, B. Biological Properties and Prospects for the Application of Eugenol—A Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 3671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, S.-E.; Kim, H.-Y.; Cha, J.-D. Synergistic Effect between Clove Oil and Its Major Compounds and Antibiotics against Oral Bacteria. Arch. Oral Biol. 2011, 56, 907–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, R.C.; Kornman, K.S. The pathogenesis of human periodontitis: An introduction. Periodontology 2000 1997, 14, 9–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, M.P.; Neut, C.; Metz, H.; Delcourt, E.; Mäder, K.; Siepmann, J.; Siepmann, F. In-situ forming composite implants for periodontitis treatment: How the formulation determines system performance. Int. J. Pharm. 2015, 486, 38–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, H.S.; Gong, M.S.; Knowles, J.C. Synthesis and biocompatibility properties of polyester containing various diacid based on isosorbide. J. Biomater. Appl. 2012, 27, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katti, D.S.; Lakshmi, S.; Langer, R.; Laurencin, C.T. Toxicity, biodegradation and elimination of polyanhydrides. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2002, 54, 933–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pal, R. Non-Newtonian behaviour of suspensions and emulsions: Review of different mechanisms. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2024, 333, 103299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, R. Fundamental Rheology of Disperse Systems Based on Single-Particle Mechanics. Fluids 2016, 1, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parent, M.; Nouvel, C.; Koerber, M.; Maincent, P.; Boudier, A. PLGA in situ implants formed by phase inversion: Critical physicochemical parameters to modulate drug release. J. Control. Release 2013, 172, 292–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, R.R.S.; Mc Millan, H.L.; Jones, D.S. Solvent induced phase inversion-based in situ forming controlled release drug delivery implants. J. Control. Release 2014, 176, 8–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damjanoska, A.; Kristina Mitreska, K.; Petrova, M.; Jelena Acevska, J.; Katerina Brezovska, K.; Nakov, N. Dimethyl Isosorbide: An Innovative Bio-Renewable Solvent for Sustainable Chromatographic Applications. Molecules 2025, 30, 2713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, R.B.; Carlson, A.N.; Solorio, L.; Exner, A.A. Characterization of formulation parameters affecting low molecular weight drug release from in situ forming drug delivery systems. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 2010, 94A, 476–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Venkatraman, S.S. Cosolvent effects on the drug release and depot swelling in injectable in situ depot-forming systems. J. Pharm. Sci. 2012, 101, 1783–1793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomaa, E.; Eissa, N.G.; Ibrahim, T.M.; El-Bassossy, H.M.; El-Nahas, H.M.; Ayoub, M.M. Development of depot PLGA-based in-situ implant of Linagliptin: Sustained release and glycemic control. Saudi Pharm. J. 2023, 31, 499–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lozza, I.; Martín-Sabroso, C.; Torres-Suarez, A.I.; Fraguas-Sanchez, A.I. In situ forming PLA and PLGA implants for the parenteral administration of Cannabidiol. Int. J. Pharm. 2024, 661, 124468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phaechamud, T.; Thurein, S.M.; Chantadee, T. Role of clove oil in solvent exchange-induced doxycycline hyclate-loaded Eudragit RS in situ forming gel. Asian J. Pharm. Sci. 2018, 13, 131–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Zhang, W.; Ye, Z.; Pei, S.; Zheng, D.; Zhu, L. Safety evaluation and pharmacodynamics of minocycline hydrochloride eye drops. Mol. Vis. 2022, 28, 460–479. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Jantratid, E.; Strauch, S.; Becker, C.; Dressman, J.B.; Amidon, G.L.; Junginger, H.E.; Kopp, S.; Midha, K.K.; Shah, V.P.; Stavchansky, S.; et al. Biowaiver monographs for immediate release solid oral dosage forms: Doxycycline hyclate. J. Pharm. Sci. 2010, 99, 1639–1653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, D.R. Elaborations on the Higuchi model for drug delivery. Int. J. Pharm. 2011, 418, 13–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soueidan, A.; Idiri, K.; Becchina, C.; Esparbès, P.; Montassier, E. Pooled analysis of oral microbiome profiles defines robust signatures associated with periodontitis. mSystems 2024, 9, e00930-24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Jaimes, T.; Monroy-Pérez, E.; Garzón, J.; Morales-Espinosa, R.; Navarro-Ocaña, A.; García-Cortés, L.R.; Nolasco-Alonso, N.; Gaytán-Núñez, F.K.; Moreno-Noguez, M.; Vaca-Paniagua, F.; et al. High Virulence and Multidrug Resistance of Escherichia coli Isolated in Periodontal Disease. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monroy-Pérez, E.; Hernández-Jaimes, T.; Morales-Espinosa, R.; Delgado, G.; Martínez-Gregorio, H.; García-Cortés, L.R.; Herrera-Gabriel, J.P.; De Lira-Silva, A.; Vaca-Paniagua, F.; Paniagua-Contreras, G.L. Analysis of in vitro expression of virulence genes related to antibiotic and disinfectant resistance in Escherichia coli as an emerging periodontal pathogen. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2024, 14, 1412007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombo, A.P.V.; do Souto, R.M.; Araújo, L.L.; Espíndola, L.C.P.; Hartenbach, F.A.R.R.; Magalhães, C.B.; da Silva Oliveira Alves, G.; Lourenço, T.G.B.; da Silva-Boghossian, C.M. Antimicrobial Resistance and Virulence of Subgingival Staphylococci Isolated from Periodontal Health and Diseases. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 11613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szafrański, S.P.; Deng, Z.-L.; Tomasch, J.; Jarek, M.; Bhuju, S.; Rohde, M.; Wagner-Döbler, I. Quorum Sensing of Streptococcus mutans Is Activated by Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans and by the Periodontal Microbiome. BMC Genom. 2017, 18, 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buonavoglia, A.; Trotta, A.; Camero, M.; Cordisco, M.; Dimuccio, M.M.; Corrente, M. Streptococcus mutans Associated with Endo-Periodontal Lesions in Intact Teeth. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 11837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Chen, X.; Chu, C.H.; Yu, O.Y.; He, J.; Li, M. Roles of Streptococcus mutans in Human Health: Beyond Dental Caries. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1503657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loyola-Rodriguez, J.P.; Martinez-Martinez, R.E.; Flores-Ferreyra, B.I.; Patiño-Marin, N.; Alpuche-Solis, A.G.; Reyes-Macias, J.F. Distribution of Streptococcus mutans and Streptococcus sobrinus in Saliva of Mexican Preschool Caries-Free and Caries-Active Children by Microbial and Molecular (PCR) Assays. J. Clin. Pediatr. Dent. 2008, 32, 121–126. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18389677/ (accessed on 5 September 2025). [CrossRef]

- Marchese, A.; Barbieri, R.; Coppo, E.; Orhan, I.E.; Daglia, M.; Nabavi, S.F.; Izadi, M.; Abdollahi, M.; Nabavi, S.M.; Ajami, M. Antimicrobial Activity of Eugenol and Essential Oils Containing Eugenol: A Mechanistic View. Molecules 2017, 22, 722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemaiswarya, S.; Doble, M. Synergistic interaction of eugenol with antibiotics against Gram-negative bacteria. Phytomedicine 2009, 16, 997–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, M.K.; Chae, S.W.; Im, G.J.; Chung, J.W.; Song, J.J. Eugenol: A phyto-compound effective against methicillin-resistant and methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus clinical strain biofilms. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0119564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafri, H.; Khan, M.S.; Ahmad, I. In vitro efficacy of eugenol in inhibiting single and mixed-biofilms of drug-resistant strains of Candida albicans and Streptococcus mutans. Phytomedicine 2019, 54, 206–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Han, W.; Gu, J.; Qiu, C.; Jiang, Q.; Dong, J.; Lei, L.; Li, F. Recent advances on the regulation of bacterial biofilm formation by herbal medicines. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 1039297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miladi, H.; Zmantar, T.; Kouidhi, B.; Al Qurashi, Y.M.A.; Bakhrouf, A.; Chaabouni, Y.; Mahdouani, K.; Chaieb, K. Synergistic Effect of Eugenol, Carvacrol, Thymol, p-Cymene and γ-Terpinene on Inhibition of Drug Resistance and Biofilm Formation of Oral Bacteria. Microb. Pathog. 2017, 112, 156–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medeiros, M.H.; Dimascio, P.; Pinto, A.P.; Vargas, R.R.; Bechara, E.J.H. Horseradish peroxidase-catalyzed conjugation of eugenol with basic amino acids. Free. Radic. Res. 1996, 25, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezerra, D.P.; Militão, G.C.G.; De Morais, M.C.; De Sousa, D.P. The Dual Antioxidant/Prooxidant Effect of Eugenol and Its Action in Cancer Development and Treatment. Nutrients 2017, 9, 1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koh, T.; Murakami, Y.; Tanaka, S.; Machino, M.; Sakagami, H. Re-evaluation of Anti-inflammatory Potential of Eugenol in IL-1β-stimulated Gingival Fibroblast and Pulp Cells. In Vivo 2013, 27, 269–274. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23422489/ (accessed on 5 September 2025). [PubMed]

- O’Connor, B.C.; Newman, H.N.; Wilson, M. Susceptibility and resistance of plaque bacteria to minocycline. J. Periodontol. 1990, 61, 228–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valcourt, C.; Saulnier, P.; Umerska, A.; Zanelli, M.P.; Montagu, A.; Rossines, E.; Joly-Guillou, M.L. Synergistic interactions between doxycycline and terpenic components of essential oils encapsulated within lipid nanocapsules against gram-negative bacteria. Int. J. Pharm. 2016, 498, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Chu, T.H.; Su, H.; Guo, A.; Wu, W. Minocycline inhibited the pro-apoptotic effect of microglia on neural progenitor cells and protected their neuronal differentiation in vitro. Neurosci. Lett. 2013, 542, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, X.; Mao, M.; Xie, J.; Zhang, K.; Xu, D. Insights into the interactions between tetracycline, its degradation products and bovine serum albumin. SpringerPlus 2016, 5, 1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tretyakova, T.; Makharadze, M.; Uchaneishvili, S.; Shushanyan, M.; Khoshtariya, D. Exploring the role of preferential solvation in the stability of globular proteins through the study of ovalbumin interaction with organic additives. AIMS Biophys. 2023, 10, 440–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Zheng, W.; Wang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Feng, K.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, H.; Xiao, Y.; Sun, C.; Liu, X.; et al. Bioinspired hydrogel for sustained minocycline release: A superior periodontitis solution. Mater. Today Bio. 2025, 32, 101638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid, J.-L.; Kirchberg, M.; Sarembe, S.; Kiesow, A.; Sculean, A.; Mäder, K.; Buchholz, M.; Eick, S. In Vitro Evaluation of Antimicrobial Activity of Minocycline Formulations for Topical Application in Periodontal Therapy. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12, 352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, N.; Ahmad, F.J.; Bedi, S.; Sharma, S.; Umar, S.; Ansari, M.A. A novel nanoformulation development of euge-nol and their treatment in inflammation and periodontitis. Saudi Pharm. J. 2019, 27, 778–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Escobar-García, M.; Rodríguez-Contreras, K.; Ruiz-Rodríguez, S.; Pierdant-Pérez, M.; Cerda-Cristerna, B.; Pozos-Guillén, A. Eugenol Toxicity in Human Dental Pulp Fibroblasts of Primary Teeth. J. Clin. Pediatr. Dent. 2016, 40, 312–318. Available online: https://www.jocpd.com/articles/10.17796/1053-4628-40.4.312 (accessed on 3 December 2025). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Said, M.M. The protective effect of eugenol against gentamicin-induced nephrotoxicity and oxidative damage in rat kidney. Fundam. Clin. Pharmacol. 2011, 25, 708–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juais, D.; Naves, A.F.; Li, C.; Gross, R.A.; Catalani, L.H. Isosorbide polyesters from enzymatic catalysis. Macromolecules 2010, 43, 10315–10319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.W.; Wyllie, R.M.; Jensen, P.A. A Novel Competence Pathway in the Oral Pathogen Streptococcus sobrinus. J. Dent. Res. 2021, 100, 542–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. Clinical Breakpoints—Bacteria (v 15.0). 2025. Available online: https://www.eucast.org/fileadmin/src/media/PDFs/EUCAST_files/Breakpoint_tables/v_15.0_Breakpoint_Tables.pdf (accessed on 18 September 2025).

- Kowalska-Krochmal, B.; Dudek-Wicher, R. The Minimum Inhibitory Concentration of Antibiotics: Methods, Interpretation, Clinical Relevance. Pathogens 2021, 10, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anjum, N.F.; Shanmugarajan, D.; Shivaraju, V.K.; Faizan, S.; Naishima, N.L.; Prashantha Kumar, B.R.; Javid, S.; Purohit, M.N. Novel derivatives of eugenol as potent antiinflammatory agents via PPARγ agonism: Rational design, synthesis, analysis, PPARγ protein binding assay and computational studies. RSC Adv. 2022, 12, 16966–16978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giugliarelli, A.; Paolantoni, M.; Morresi, A.; Sassi, P. Denaturation and Preservation of Globular Proteins: The Role of DMSO. J. Phys. Chem. B 2012, 116, 13361–13367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Formulation | Composition * | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DMI, mg | EUG, mg | DOXY, mg | MIN, mg | |

| F1 | 1600 | - | - | - |

| F2 | 1600 | - | 200 | - |

| F3 | 1440 | 160 | 200 | - |

| F4 | 1600 | - | - | 200 |

| F5 | 1440 | 160 | - | 200 |

| F6 | 1440 | 160 | - | - |

| F7 | 1120 | 480 | - | - |

| F8 | 800 | 800 | - | 200 |

| Formulation | Zero-Order Model | First-Order Model | Higuchi Model | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| r2 | k0, h−1 | r2 | k1, h−1 | r2 | kH, h−1/2 | |

| F2 | 0.7025 | 0.1193 | 0.8774 | 0.00276 | 0.9548 | 2.493 |

| F3 | 0.2911 | 0.0603 | 0.3828 | 0.00092 | 0.9519 | 0.574 |

| F4 | 0.2053 | 0.0876 | 0.5693 | 0.06633 | 0.5355 | 0.514 |

| F5 | 0.2699 | 0.0861 | 0.5205 | 0.00276 | 0.9310 | 0.752 |

| F6 | 0.6225 | 0.1552 | 0.9885 | 0.01865 | 0.8392 | 3.404 |

| F7 | 0.6446 | 0.1705 | 0.9790 | 0.02464 | 0.8067 | 3.984 |

| F8 | 0.6577 | 0.1704 | 0.9955 | 0.01796 | 0.8088 | 4.054 |

| Bacteria | 1 Day | 21 Days | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| F2 | F3 | F2 | F3 | |

| E. coli ATCC 25922 | 18.7 ± 1.53 a | 22.3 ± 0.58 b | 0 ± 0 a | 9.33 ± 1.15 b |

| S. aureus ATCC 25923 | 31.7 ± 1.53 a | 37.3 ± 3.06 b | 13.0 ± 1 a | 22.7 ± 0.58 b |

| S. mutans ATCC 25175 | 33.3 ± 1.53 a | 35.0 ± 0.0 a | 0 ± 0 a | 19.0 ± 1.73 b |

| S. sobrinus ATCC 33478 | 31.0 ± 1.0 a | 40.0 ± 0.0 b | 0 ± 0 a | 18.0 ± 1.73 b |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Śmiga-Matuszowicz, M.; Nowak, B.; Wojcieszyńska, D. Antibacterial Agent-Loaded, Novel In Situ Forming Implants Made with Poly(Isosorbide Sebacate) and Dimethyl Isosorbide as a Solvent for Periodontitis Treatment. Molecules 2025, 30, 4717. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244717

Śmiga-Matuszowicz M, Nowak B, Wojcieszyńska D. Antibacterial Agent-Loaded, Novel In Situ Forming Implants Made with Poly(Isosorbide Sebacate) and Dimethyl Isosorbide as a Solvent for Periodontitis Treatment. Molecules. 2025; 30(24):4717. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244717

Chicago/Turabian StyleŚmiga-Matuszowicz, Monika, Bożena Nowak, and Danuta Wojcieszyńska. 2025. "Antibacterial Agent-Loaded, Novel In Situ Forming Implants Made with Poly(Isosorbide Sebacate) and Dimethyl Isosorbide as a Solvent for Periodontitis Treatment" Molecules 30, no. 24: 4717. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244717

APA StyleŚmiga-Matuszowicz, M., Nowak, B., & Wojcieszyńska, D. (2025). Antibacterial Agent-Loaded, Novel In Situ Forming Implants Made with Poly(Isosorbide Sebacate) and Dimethyl Isosorbide as a Solvent for Periodontitis Treatment. Molecules, 30(24), 4717. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244717