First In Vitro Human Islet Assessment of Oleanolic Acid (OA) and Its Serine Conjugate: Enhanced Solubility with Comparable Effects

Abstract

1. Introduction

Advantages of Choosing Human Islets Compared to Rodent Islets

2. Results and Discussion

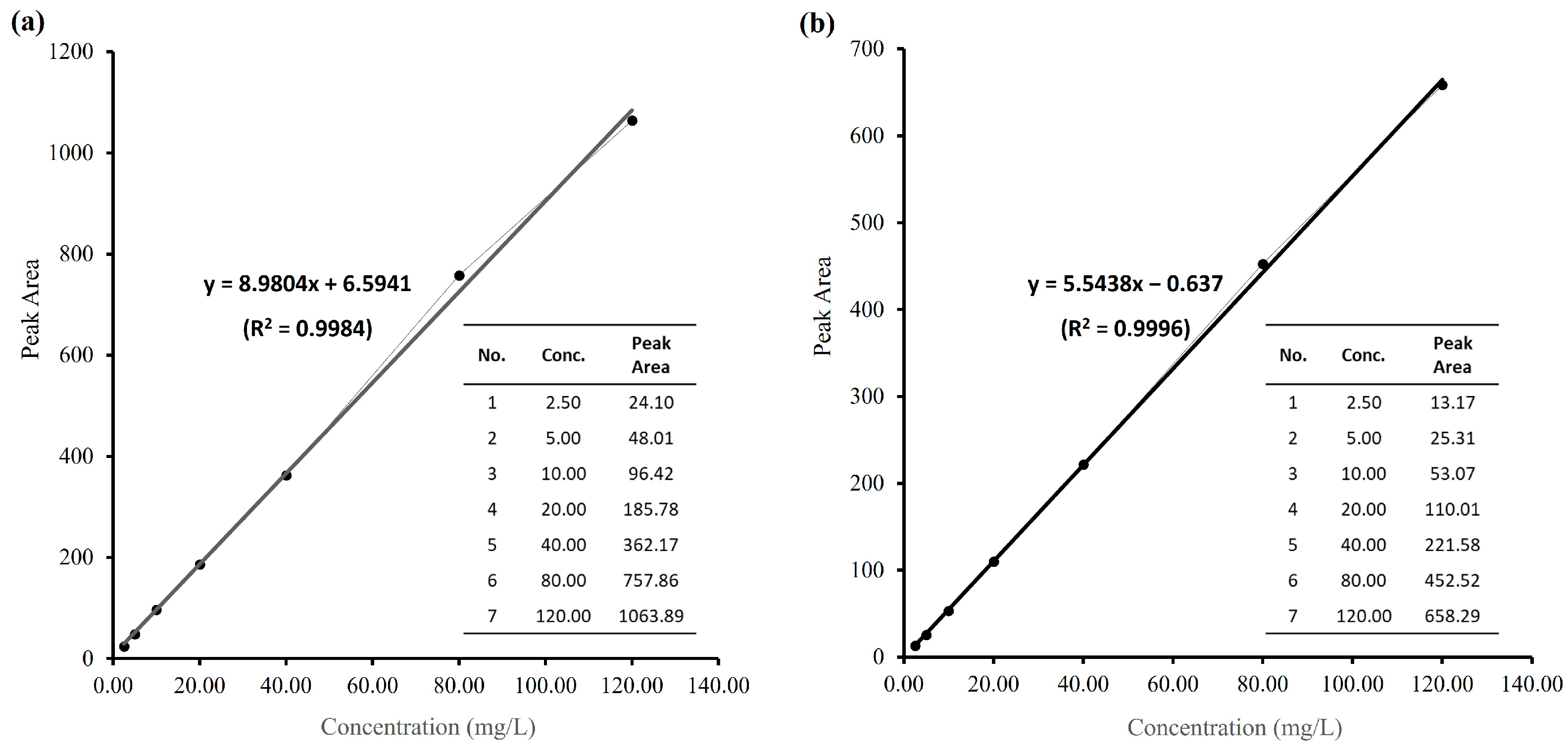

2.1. Measurement of Log Pow Values for OA and 1a

2.2. Evaluation for Human Islets Cultured with OA and Its Derivative 1a

2.2.1. OA/1a Culture Concentration and Culture Period

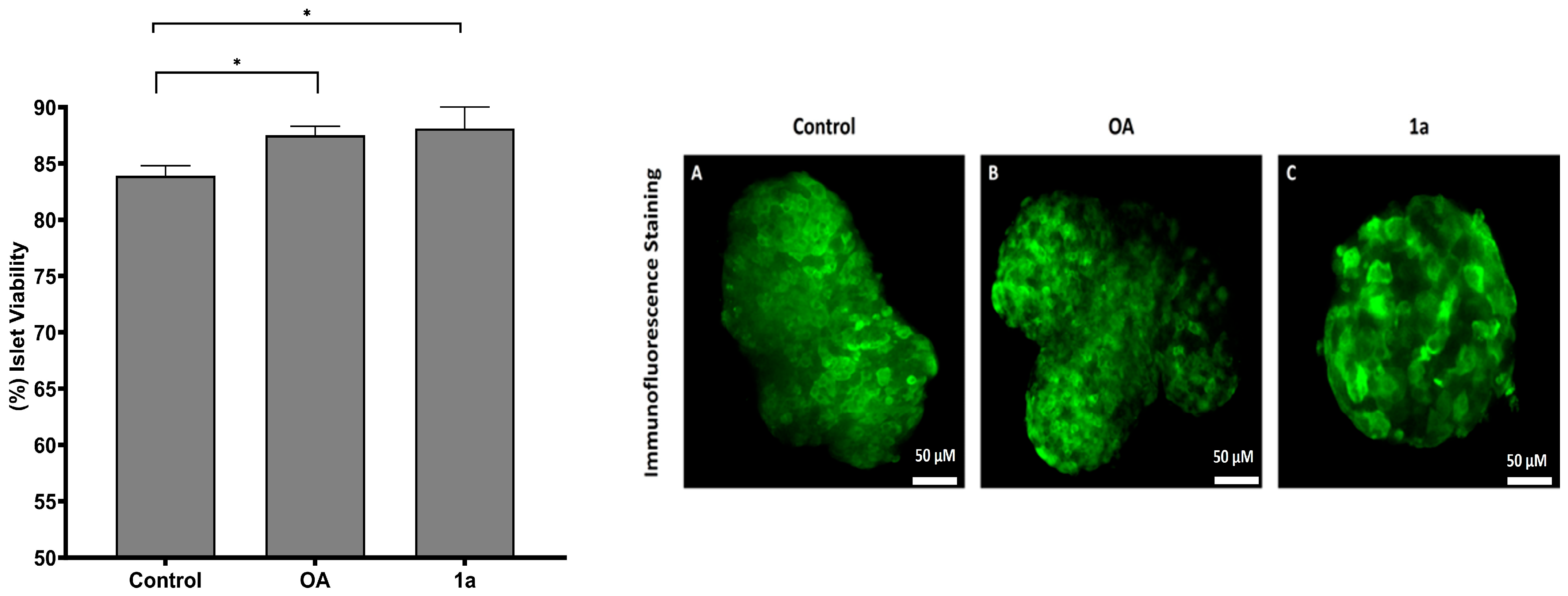

2.2.2. Viability Evaluation for Human Islets Cultured with OA and Its Derivative 1a

2.2.3. Immunofluorescence Staining Assay for Post-Cultured Human Islets

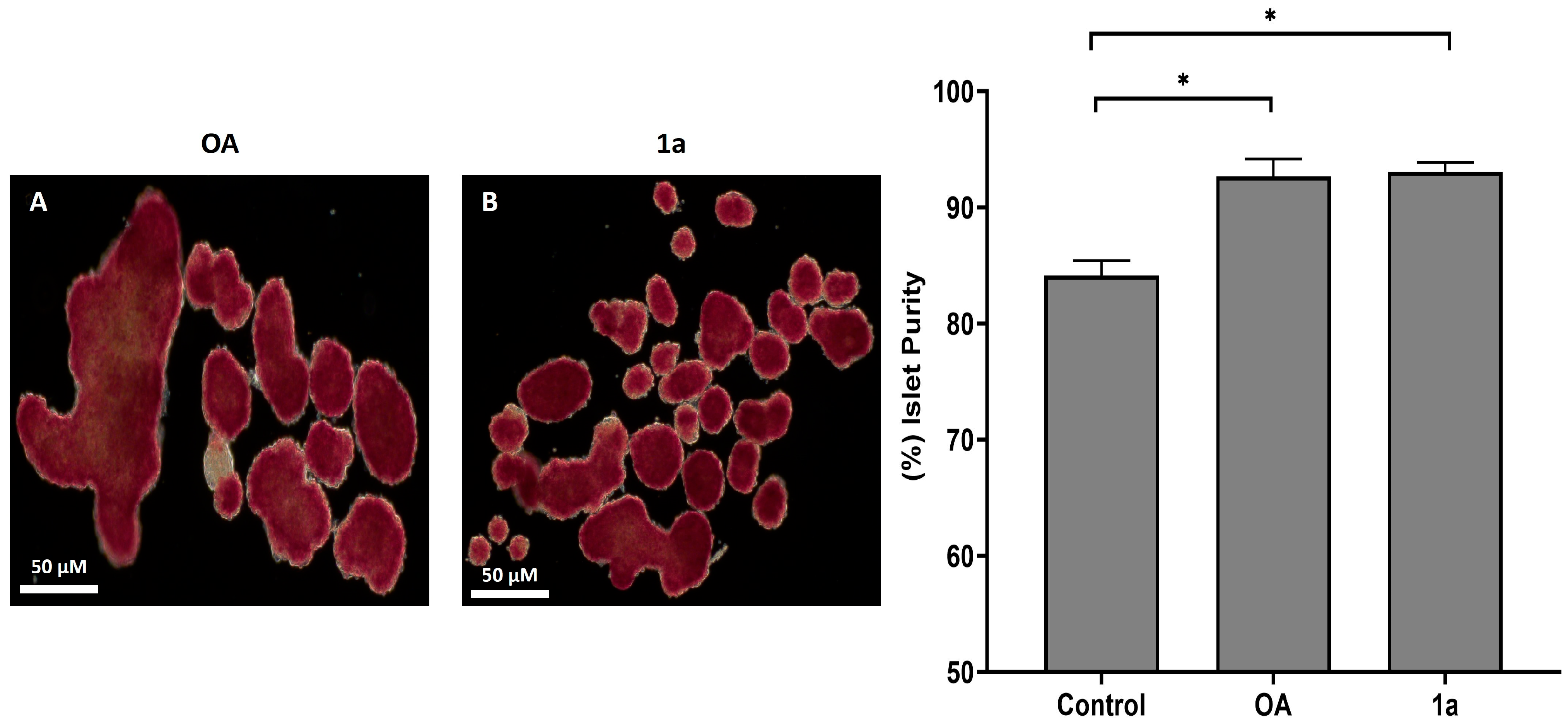

2.2.4. Dithizone (DTZ) Staining Assay for Post-Cultured Human Islets

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials

3.2. Methods

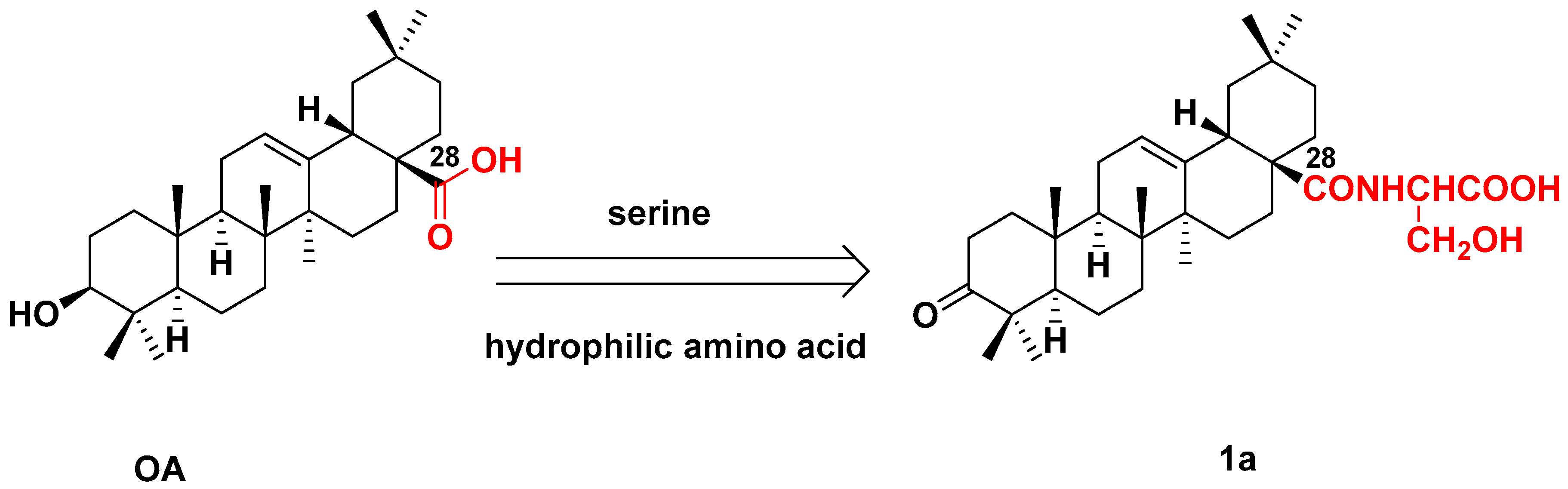

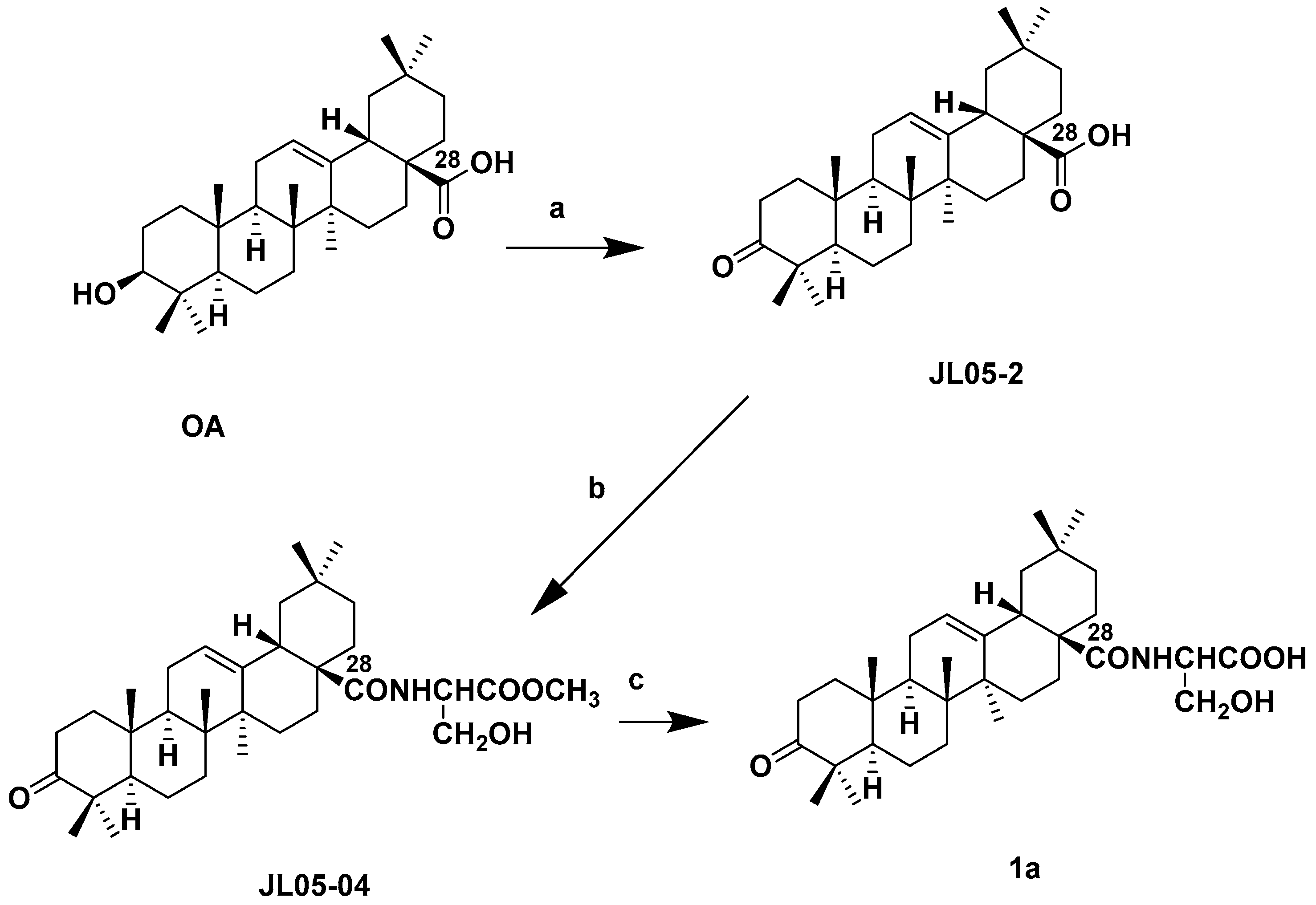

3.2.1. Synthesis of 1a

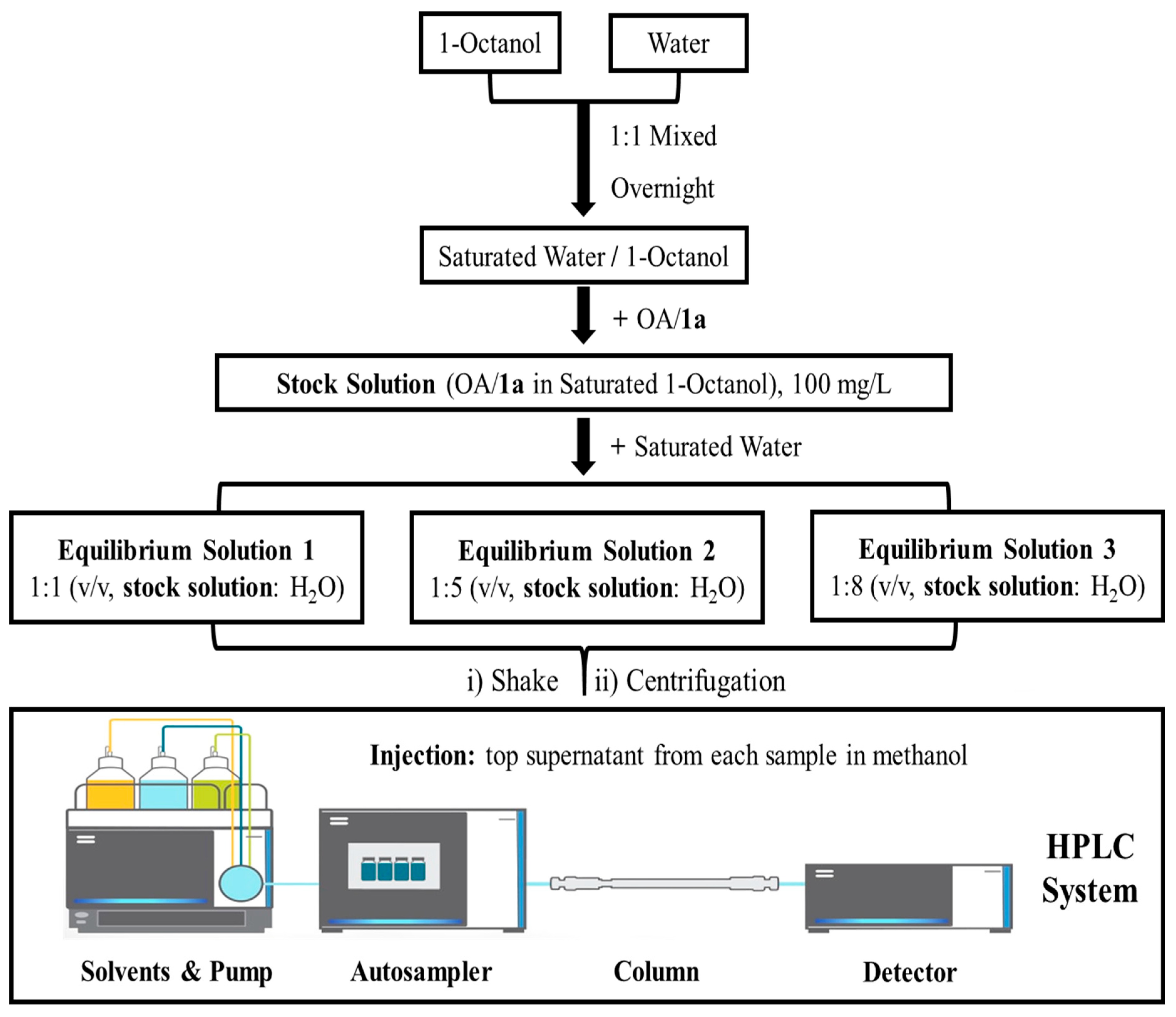

3.2.2. Measuring Log Pow by HPLC

HPLC Program Conditions

Standard Calibration Curves of OA and 1a

Sample Preparation and Partitioning Procedure

Calculation of Log Pow Value

3.2.3. OA and 1a Pre-Treatment

OA/1a Culture Concentration and Culture Period

Human Islet Culture

In Vitro Islet Viability Assay

DTZ Staining for Islet Purity

Immunofluorescence Staining

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Langlois, A.; Pinget, M.; Kessler, L.; Bouzakri, K. Islet transplantation: Current limitations and challenges for successful outcomes. Cells 2024, 13, 1783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yehya, H.; Wells, A.; Majcher, M.; Nakhwa, D.; King, R.; Senturk, F.; Padmanabhan, R.; Jensen, J.; Bukys, M.A. Identifying and optimizing critical process parameters for large-scale manufacturing of iPSC derived insulin-producing β-cells. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2024, 15, 408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, X.; Gong, Z.; Yin, W.; Li, H.; Douroumis, D.; Huang, L.; Li, H. Islet cell spheroids produced by a thermally sensitive scaffold: A new diabetes treatment. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2024, 22, 657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Tian, M.; Wu, J.; Gu, X.; Liu, H.; Ma, X.; Wang, W. Mesenchymal stem cell conditioned medium improves hypoxic injury to protect islet graft function. Zhong Nan Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban 2024, 49, 1210–1219. [Google Scholar]

- Noguchi, H.; Miyagi-Shiohira, C.; Kurima, K.; Kobayashi, N.; Saitoh, I.; Watanabe, M.; Noguchi, Y.; Matsushita, M. Islet culture/preservation before islet transplantation. Cell Med. 2015, 8, 25–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iskender, H.; Dokumacioglu, E.; Terim Kapakin, K.A.; Yenice, G.; Mohtare, B.; Bolat, I.; Hayirli, A. Effects of oleanolic acid on inflammation and metabolism in diabetic rats. Biotech. Histochem. 2022, 97, 269–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, K.; Haider, K.; Jabeen, K.; Akash, M.S.H. Current perspectives of oleic acid: Regulation of molecular pathways in mitochondrial and endothelial functioning against insulin resistance and diabetes. Rev. Endocr. Metab. Disord. 2020, 21, 631–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, Z.C.; Lin, S.X.; Yan, W.L.; Chen, D.; Zeng, Z.W.; Chen, L.; Li, Y.; He, B. Enhanced water solubility and anti-tumor activity of oleanolic acid through chemical structure modification. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 13291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, A. Prophylactic and therapeutic roles of oleanolic acid and its derivatives in several diseases. World J. Clin. Cases 2020, 8, 1767–1792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Aparicio, A.; Correa-Rodriguez, M.; Castellano, J.M.; Schmidt-RioValle, J.; Perona, J.S.; Gonzalez-Jimenez, E. Potential molecular targets of oleanolic acid in insulin resistance and underlying oxidative stress: A systematic review. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Q.F.; Peng, H.P.; Lu, X.R.; Hu, Y.; Xu, Z.H.; Xu, J.K. Oleanolic acid regulates the Treg/Th17 imbalance in gastric cancer by targeting IL-6 with miR-98-5p. Cytokine 2021, 148, 155656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayeleso, T.B.; Matumba, M.G.; Mukwevho, E. Oleanolic acid and its derivatives: Biological activities and therapeutic potential in chronic diseases. Molecules 2017, 22, 1915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; He, T.; Lu, Q.; Shang, J.; Sun, H.; Zhang, L. Asiatic acid preserves beta cell mass and mitigates hyperglycemia in streptozocin-induced diabetic rats. Diabetes Metab. Res. Rev. 2010, 26, 448–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teodoro, T.; Zhang, L.; Alexander, T.; Yue, J.; Vranic, M.; Volchuk, A. Oleanolic acid enhances insulin secretion in pancreatic beta-cells. FEBS Lett. 2008, 582, 1375–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, J.H.; Wu, Y.C.; Liu, I.M.; Cheng, J.T. Release of acetylcholine to raise insulin secretion in Wistar rats by oleanolic acid, one of the active principles contained in Cornus officinalis. Neurosci. Lett. 2006, 404, 112–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nataraju, A.; Saini, D.; Ramachandran, S.; Benshoff, N.; Liu, W.; Chapman, W.; Mohanakumar, T. Oleanolic acid, a plant triterpenoid, significantly improves survival and function of islet allograft. Transplantation 2009, 88, 987–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Vaziri, N.D.; Masuda, Y.; Hajighasemi-Ossareh, M.; Robles, L.; Le, A.; Vo, K.; Chan, J.Y.; Foster, C.E.; Stamos, M.J.; et al. Pharmacological activation of Nrf2 pathway improves pancreatic islet isolation and transplantation. Cell Transpl. 2015, 24, 2273–2283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans, J.L.; Goldfine, I.D.; Maddux, B.A.; Grodsky, G.M. Oxidative stress and stress-activated signaling pathways: A unifying hypothesis of type 2 diabetes. Endocr. Rev. 2002, 23, 599–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iskender, H.; Dokumacioglu, E.; Terim Kapakin, K.A.; Bolat, I.; Mokhtare, B.; Hayirli, A.; Yenice, G. Effect of oleanolic acid administration on hepatic AMPK, SIRT-1, IL-6 and NF-kappaB levels in experimental diabetes. J. Diabetes Metab. Disord. 2023, 22, 581–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takada, K.; Nakane, T.; Masuda, K.; Ishii, H. Ursolic acid and oleanolic acid, members of pentacyclic triterpenoid acids, suppress TNF-alpha-induced E-selectin expression by cultured umbilical vein endothelial cells. Phytomedicine 2010, 17, 1114–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramírez-Espinosa, J.J.; Rios, M.Y.; López-Martínez, S.; López-Vallejo, F.; Medina-Franco, J.L.; Paoli, P.; Camici, G.; Navarrete-Vázquez, G.; Ortiz-Andrade, R.; Estrada-Soto, S. Antidiabetic activity of some pentacyclic acid triterpenoids, role of PTP-1B: In vitro, in silico, and in vivo approaches. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2011, 46, 2243–2251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bu, Y.; Shi, T.; Meng, M.; Kong, G.; Tian, Y.; Chen, Q.; Yao, X.; Feng, G.; Chen, H.; Lu, Z. A novel screening model for the molecular drug for diabetes and obesity based on tyrosine phosphatase Shp2. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2011, 21, 874–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quang, T.H.; Ngan, N.T.; Minh, C.V.; Kiem, P.V.; Thao, N.P.; Tai, B.H.; Nhiem, N.X.; Song, S.B.; Kim, Y.H. Effect of triterpenes and triterpene saponins from the stem bark of Kalopanax pictus on the transactivational activities of three PPAR subtypes. Carbohydr. Res. 2011, 346, 2567–2575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Q.K.; Yang, X.X.; Du, P.; Zhang, H.F.; Zhang, T.H. Dual strategies to improve oral bioavailability of oleanolic acid: Enhancing water-solubility, permeability and inhibiting cytochrome P450 isozymes. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2016, 99, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, D.W.; Kim, Y.H.; Kim, H.H.; Ji, H.Y.; Yoo, S.D.; Choi, W.R.; Lee, S.M.; Han, C.K.; Lee, H.S. Dose-linear pharmacokinetics of oleanolic acid after intravenous and oral administration in rats. Biopharm. Drug Dispos. 2007, 28, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, G.F.; Luan, W.J.; Wang, S.; Cui, S.S.; Li, F.R.; Liu, Y.X.; Liu, Y.; Cheng, M.S. A library of 1,2,3-triazole-substituted oleanolic acid derivatives as anticancer agents: Design, synthesis, and biological evaluation. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2015, 13, 1507–1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, Y.Q.; Kuai, Z.Y.; Zhan, S.W.; Li, C.L.; Chen, H.R. Design, synthesis, and antitumor activity of oleanolic acid derivatives. J. Asian Nat. Prod. Res. 2019, 21, 633–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.F.; Zhao, Y.; Cai, M.M.; Li, X.F.; Li, J.X. Synthesis and evaluation of a novel series of heterocyclic oleanolic acid derivatives with anti-osteoclast formation activity. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2009, 44, 2796–2806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.F.; Chen, S.J.; Zhao, Y.; Li, J.X. Glycoside modification of oleanolic acid derivatives as a novel class of anti-osteoclast formation agents. Carbohydr. Res. 2009, 344, 599–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.Y.; Jia, X.J.; Dong, J.Z.; Chen, D.Y.; Liu, J.; Zhang, L.Y.; Wen, X.A. Synthesis and evaluation of novel oleanolic acid derivatives as potential antidiabetic agents. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 2014, 83, 297–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Z.J.; Zhang, L.Y.; Li, L.C.; Liu, J.; Li, H.L.; Zhang, L.Y.; Chen, L.M.; Cheng, K.G.; Zheng, M.Y.; Wen, X.A.; et al. Identification of pentacyclic triterpenes derivatives as potent inhibitors against glycogen phosphorylase based on 3D-QSAR studies. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2011, 46, 2011–2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaddis, J.S.; Olack, B.J.; Sowinski, J.; Cravens, J.; Contreras, J.L.; Niland, J.C. Human pancreatic islets and diabetes research. JAMA 2009, 301, 1580–1587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, A.; Miller, K.; Jo, J.; Kilimnik, G.; Wojcik, P.; Hara, M. Islet architecture: A comparative study. Islets 2009, 1, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilimnik, G.; Jo, J.; Periwal, V.; Zielinski, M.C.; Hara, M. Quantification of islet size and architecture. Islets 2012, 4, 167–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steiner, D.J.; Kim, A.; Miller, K.; Hara, M. Pancreatic islet plasticity: Interspecies comparison of islet architecture and composition. Islets 2010, 2, 135–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dolensek, J.; Rupnik, M.S.; Stozer, A. Structural similarities and differences between the human and the mouse pancreas. Islets 2015, 7, e1024405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, C.; Brissova, M.; Hang, Y.; Thompson, C.; Poffenberger, G.; Shostak, A.; Chen, Z.; Stein, R.; Powers, A.C. Islet-enriched gene expression and glucose-induced insulin secretion in human and mouse islets. Diabetologia 2012, 55, 707–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vernier, S.; Chiu, A.; Schober, J.; Weber, T.; Nguyen, P.; Luer, M.; McPherson, T.; Wanda, P.E.; Marshall, C.A.; Rohatgi, N.; et al. beta-cell metabolic alterations under chronic nutrient overload in rat and human islets. Islets 2012, 4, 379–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brissova, M.; Shostak, A.; Fligner, C.L.; Revetta, F.L.; Washington, M.K.; Powers, A.C.; Hull, R.L. Human islets have fewer Blood vessels than mouse islets and the density of islet vascular structures is increased in type 2 diabetes. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 2015, 63, 637–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avrahami, D.; Li, C.; Yu, M.; Jiao, Y.; Zhang, J.; Naji, A.; Ziaie, S.; Glaser, B.; Kaestner, K.H. Targeting the cell cycle inhibitor p57Kip2 promotes adult human beta cell replication. J. Clin. Investig. 2014, 124, 670–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amisten, S.; Atanes, P.; Hawkes, R.; Ruz-Maldonado, I.; Liu, B.; Parandeh, F.; Zhao, M.; Huang, G.C.; Salehi, A.; Persaud, S.J. A comparative analysis of human and mouse islet G-protein coupled receptor expression. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 46600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leo, A.; Hansch, C.; Elkins, D. Partition coefficients and their uses. Chem. Rev. 1971, 71, 525–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cumming, H.; Rucker, C. Octanol-water partition coefficient measurement by a simple 1H NMR Method. ACS Omega 2017, 2, 6244–6249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.; Baboota, S.; Ali, J.; Khan, S.; Narang, R.S.; Narang, J.K. Nanostructured lipid carriers: An emerging platform for improving oral bioavailability of lipophilic drugs. Int. J. Pharm. Investig. 2015, 5, 182–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu Lila, A.S.; Ishida, T. Liposomal delivery systems: Design optimization and current applications. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2017, 40, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodges, G.; Eadsforth, C.; Bossuyt, B.; Bouvy, A.; Enrici, M.-H.; Geurts, M.; Kotthoff, M.; Michie, E.; Miller, D.; Müller, J.; et al. A comparison of log Kow (n-octanol–water partition coefficient) values for non-ionic, anionic, cationic and amphoteric surfactants determined using predictions and experimental methods. Environ. Sci. Eur. 2019, 31, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isik, M.; Levorse, D.; Mobley, D.L.; Rhodes, T.; Chodera, J.D. Octanol-water partition coefficient measurements for the SAMPL6 blind prediction challenge. J. Comput. Aid Mol. Des. 2020, 34, 405–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pretzner, B.; Maschke, R.W.; Haiderer, C.; John, G.T.; Herwig, C.; Sykacek, P. Predictive monitoring of shake flask cultures with online estimated growth models. Bioengineering 2021, 8, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tolls, J.; Bodo, K.; De Felip, E.; Dujardin, R.; Kim, Y.H.; Moeller-Jensen, L.; Mullee, D.; Nakajima, A.; Paschke, A.; Pawliczek, J.B.; et al. Slow-stirring method for determining the n-octanol/water partition coefficient (Pow) for highly hydrophobic chemicals: Performance evaluation in a ring test. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2003, 22, 1051–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mtewa, A.G.; Ngwira, K.; Lampiao, F.; Weisheit, A.; Tolo, C.U.; Ogwang, P.E.; Sesaazi, D.C. Fundamental methods in drug permeability, pKa, LogP and LogDx determination. J. Drug Res. Dev. 2018, 4, 2470-1009.146. [Google Scholar]

- Elmansi, H.; Nasr, J.J.; Rageh, A.H.; El-Awady, M.I.; Hassan, G.S.; Abdel-Aziz, H.A.; Belal, F. Assessment of lipophilicity of newly synthesized celecoxib analogues using reversed-phase HPLC. Bmc Chem. 2019, 13, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.Y.; Chen, C. Evaluation of calibration equations by using regression analysis: An example of chemical analysis. Sensors 2022, 22, 447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pagliano, E.; Meija, J. A tool to evaluate nonlinearity in calibration curves involving isotopic internal standards in mass spectrometry. Int. J. Mass. Spectrom. 2021, 464, 116557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banarase, N.B.; Kaur, C.D. UV-spectrophotometric determination of partition coefficient (log p) of oleanolic acid and its comparison with software predicted values. Indian Drugs 2022, 59, 91–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellano, J.M.; Garcia-Rodriguez, S.; Espinosa, J.M.; Millan-Linares, M.C.; Rada, M.; Perona, J.S. Oleanolic acid exerts a neuroprotective effect against microglial cell activation by modulating cytokine release and antioxidant defense systems. Biomolecules 2019, 9, 683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, A.M.; Alvarado, H.L.; Abrego, G.; Martins-Gomes, C.; Garduno-Ramirez, M.L.; Garcia, M.L.; Calpena, A.C.; Souto, E.B. In vitro cytotoxicity of oleanolic/ursolic acids-loaded in PLGA nanoparticles in different cell lines. Pharmaceutics 2019, 11, 362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verheijen, M.; Lienhard, M.; Schrooders, Y.; Clayton, O.; Nudischer, R.; Boerno, S.; Timmermann, B.; Selevsek, N.; Schlapbach, R.; Gmuender, H.; et al. DMSO induces drastic changes in human cellular processes and epigenetic landscape in vitro. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 4641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellin, M.D.; Kim, T.; Wilhelm, J.J.; Schwarzenberg, S.J.; Chinnakotla, S. Regulatory considerations of delayed autologous islet infusion in a 4-year-old child undergoing total pancreatectomy for chronic pancreatitis. Am. J. Transpl. 2020, 20, 306–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salgado, M.; Gonzalez, N.; Medrano, L.; Rawson, J.; Omori, K.; Qi, M.; Al-Abdullah, I.; Kandeel, F.; Mullen, Y.; Komatsu, H. Semi-automated assessment of human islet viability predicts transplantation outcomes in a diabetic mouse model. Cell Transpl. 2020, 29, 963689720919444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komatsu, H.; Omori, K.; Parimi, M.; Rawson, J.; Kandeel, F.; Mullen, Y. Determination of islet viability using a zinc-specific fluorescent dye and a semiautomated assessment method. Cell Transpl. 2016, 25, 1777–1786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemos, N.E.; Dieter, C.; Farias, M.G.; Rheinheimer, J.; Souza, B.M.; Bauer, A.C.; Crispim, D. Comparison of two techniques for assessing pancreatic islet viability: Flow cytometry and fluorescein diacetate/propidium iodide staining. Clin. Biomed. Res. 2021, 41, 325–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Im, K.; Mareninov, S.; Diaz, M.F.P.; Yong, W.H. An introduction to performing immunofluorescence staining. Methods Mol. Biol. 2019, 1897, 299–311. [Google Scholar]

- Bussolati, G.; Annaratone, L.; Berrino, E.; Miglio, U.; Panero, M.; Cupo, M.; Gugliotta, P.; Venesio, T.; Sapino, A.; Marchio, C. Acid-free glyoxal as a substitute of formalin for structural and molecular preservation in tissue samples. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0182965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, W.; Zhang, C.; Mohiuddin, T.M.; Al-Rawe, M.; Zeppernick, F.; Falcone, F.H.; Meinhold-Heerlein, I.; Hussain, A.F. Multiplex Immunofluorescence: A Powerful Tool in Cancer Immunotherapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 3086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kitzmann, J.P.; Karatzas, T.; Mueller, K.R.; Avgoustiniatos, E.S.; Gruessner, A.C.; Balamurugan, A.N.; Bellin, M.D.; Hering, B.J.; Papas, K.K. Islet preparation purity is overestimated, and less pure fractions have lower post-culture viability before clinical allotransplantation. Transpl. Proc. 2014, 46, 1953–1955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benomar, K.; Chetboun, M.; Espiard, S.; Jannin, A.; Le Mapihan, K.; Gmyr, V.; Caiazzo, R.; Torres, F.; Raverdy, V.; Bonner, C.; et al. Purity of islet preparations and 5-year metabolic outcome of allogenic islet transplantation. Am. J. Transpl. 2018, 18, 945–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Latif, Z.A.; Noel, J.; Alejandro, R. A simple method of staining fresh and cultured islets. Transplantation 1988, 45, 827–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thapa, B.; Suh, E.H.; Parrott, D.; Khalighinejad, P.; Sharma, G.; Chirayil, S.; Sherry, A.D. Imaging beta-cell function using a zinc-tesponsive MRI contrast agent may identify first responder islets. Front. Endocrinol. 2021, 12, 809867. [Google Scholar]

- Khiatah, B.; Qi, M.; Wu, Y.; Chen, K.T.; Perez, R.; Valiente, L.; Omori, K.; Isenberg, J.S.; Kandeel, F.; Yee, J.K.; et al. Pancreatic human islets and insulin-producing cells derived from embryonic stem cells are rapidly identified by a newly developed Dithizone. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 9295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Y.Q.; Liu, D.; Cai, L.L.; Chen, H.; Cao, B.; Wang, Y.Z. The synthesis of ursolic acid derivatives with cytotoxic activity and the investigation of their preliminary mechanism of action. Bioorgan Med. Chem. 2009, 17, 848–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, J.W.; Dai, Y.C.; Xue, J.P.; Wang, J.C.; Lin, F.P.; Guo, Y.H. In vitro and in vivo anticancer activity evaluation of ursolic acid derivatives. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2011, 46, 2652–2661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yin, R.; Zhao, L.; Huang, L.A.; Zhao, R.; Wu, A.; Rao, M.; Wu, J.; Wu, C.; Kandeel, F.R.; Li, J. First In Vitro Human Islet Assessment of Oleanolic Acid (OA) and Its Serine Conjugate: Enhanced Solubility with Comparable Effects. Molecules 2025, 30, 4716. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244716

Yin R, Zhao L, Huang LA, Zhao R, Wu A, Rao M, Wu J, Wu C, Kandeel FR, Li J. First In Vitro Human Islet Assessment of Oleanolic Acid (OA) and Its Serine Conjugate: Enhanced Solubility with Comparable Effects. Molecules. 2025; 30(24):4716. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244716

Chicago/Turabian StyleYin, Runkai, Li Zhao, Lina A. Huang, Rui Zhao, Andy Wu, Maggie Rao, Jason Wu, Claire Wu, Fouad R. Kandeel, and Junfeng Li. 2025. "First In Vitro Human Islet Assessment of Oleanolic Acid (OA) and Its Serine Conjugate: Enhanced Solubility with Comparable Effects" Molecules 30, no. 24: 4716. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244716

APA StyleYin, R., Zhao, L., Huang, L. A., Zhao, R., Wu, A., Rao, M., Wu, J., Wu, C., Kandeel, F. R., & Li, J. (2025). First In Vitro Human Islet Assessment of Oleanolic Acid (OA) and Its Serine Conjugate: Enhanced Solubility with Comparable Effects. Molecules, 30(24), 4716. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244716