Molecular Mechanisms by Which Linear Versus Branched Alkyl Chains in Nonionic Surfactants Govern the Wettability of Long-Flame Coal

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experiments and Simulations

2.1. Experimental Materials

| Sample | Industrial Analysis (wt%) | Density (g/cm3) | Elemental Analysis (wt%, d.m.m.f) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mad | Aad | Vdaf | C | H | N | S | O | ||

| long-flame coal | 2.55 | 1.25 | 37.77 | 1.26 | 78.46 | 4.52 | 1.18 | 0.75 | 15.09 |

2.2. Adsorption Experiment

2.3. Surface Characterization

2.4. Coal Structural Characterization

2.5. Molecular Simulation

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Surface Characterization Analysis

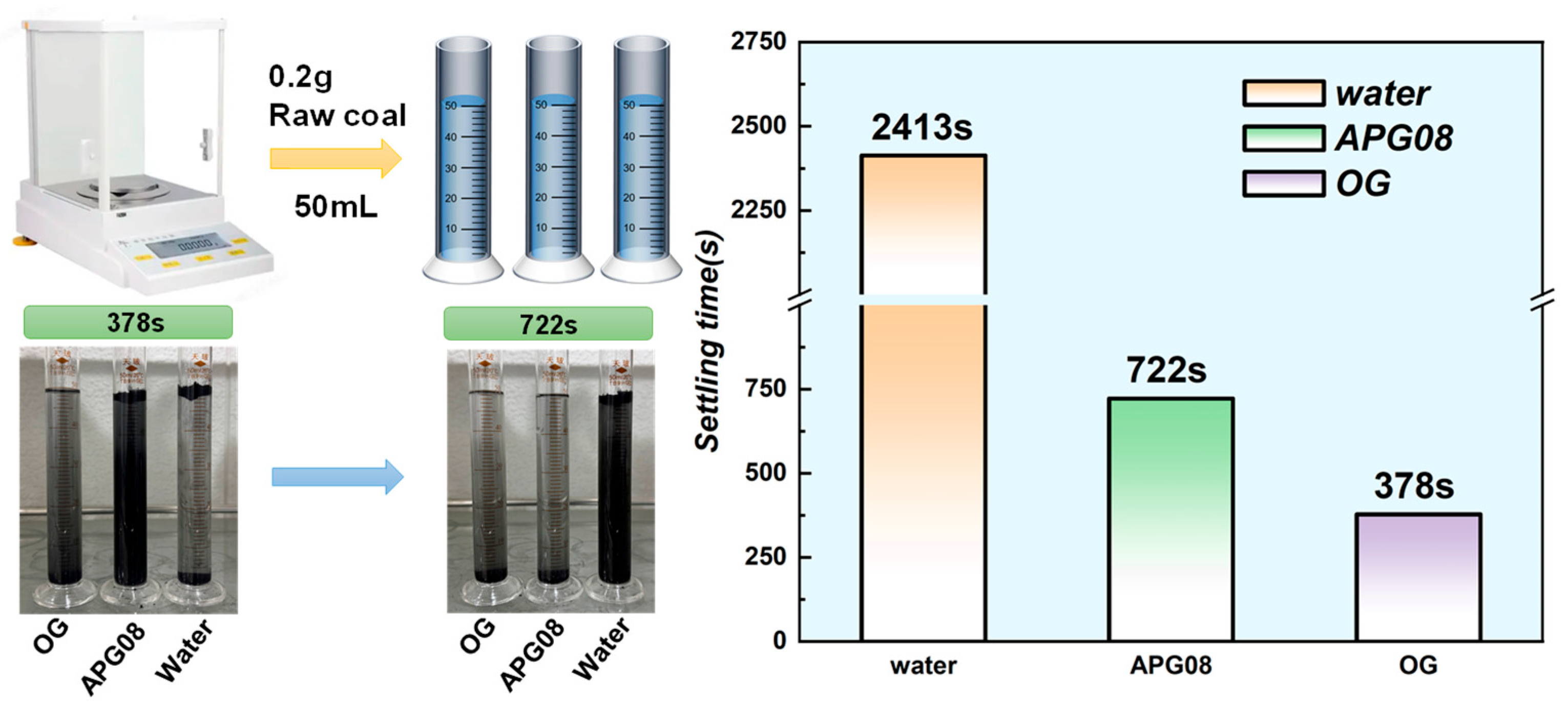

3.1.1. Settlement Experimental Analysis

3.1.2. Contact Angle Analysis

3.2. Coal Structural Characterization Analysis

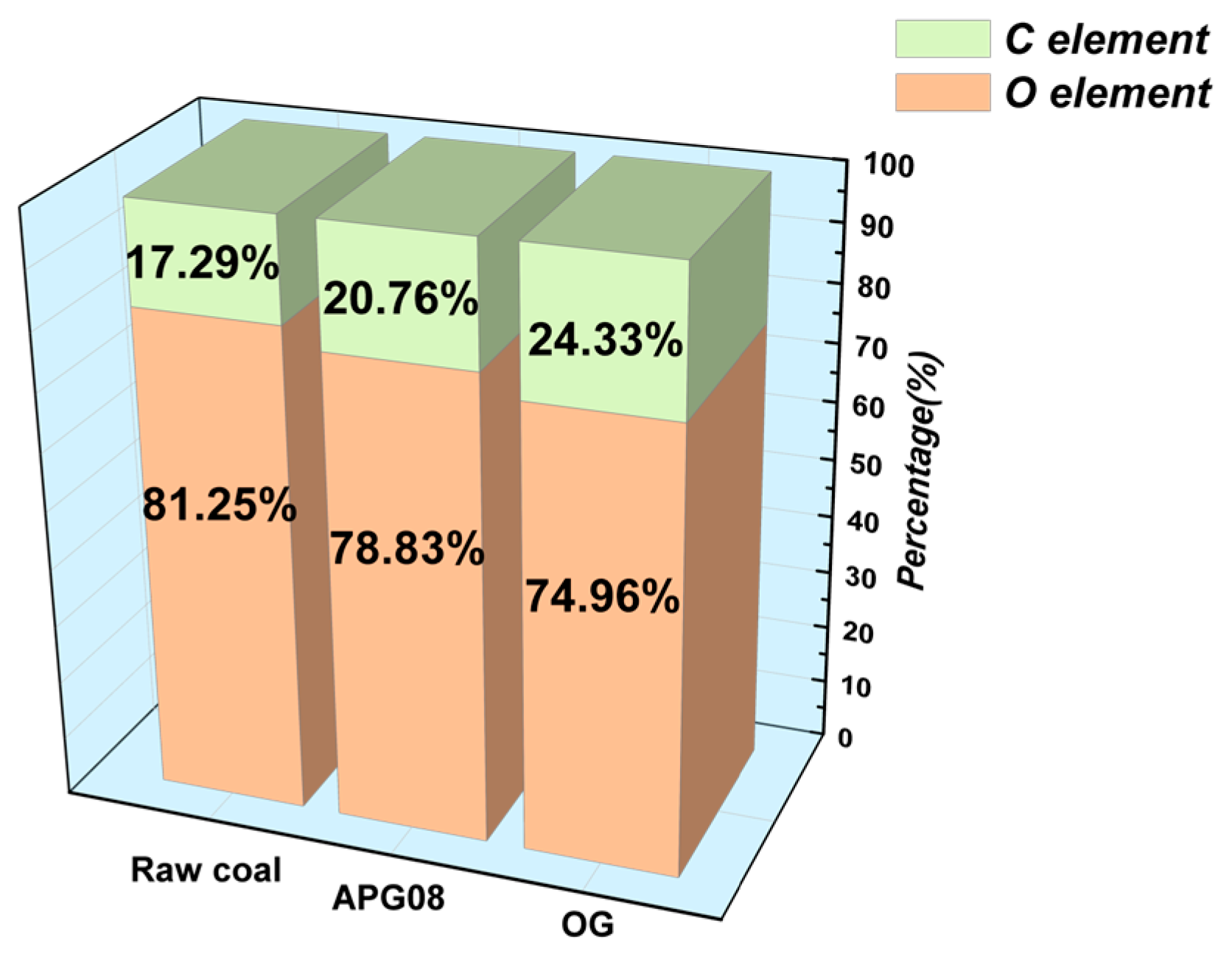

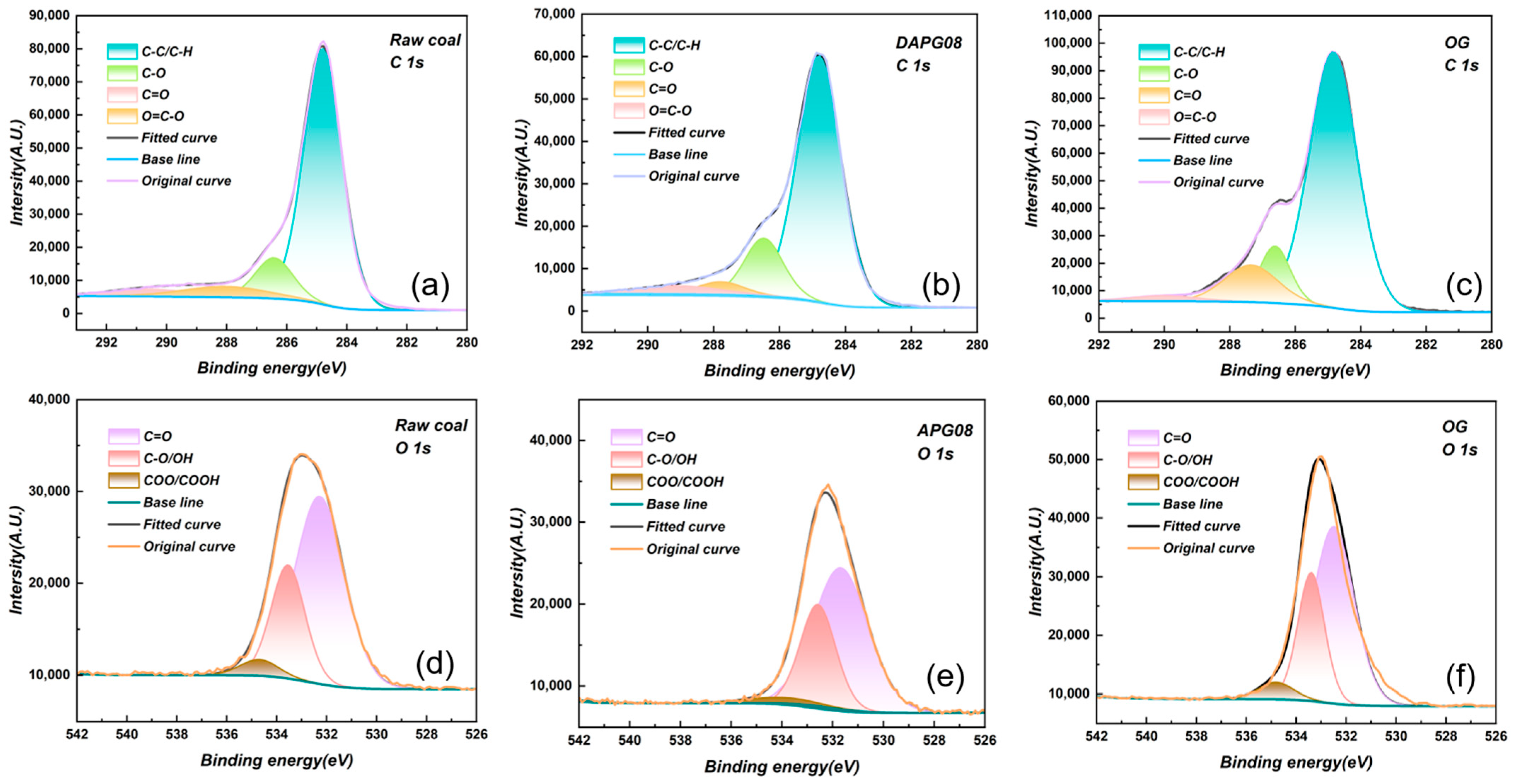

3.2.1. XPS Analysis

3.2.2. FTIR Analysis

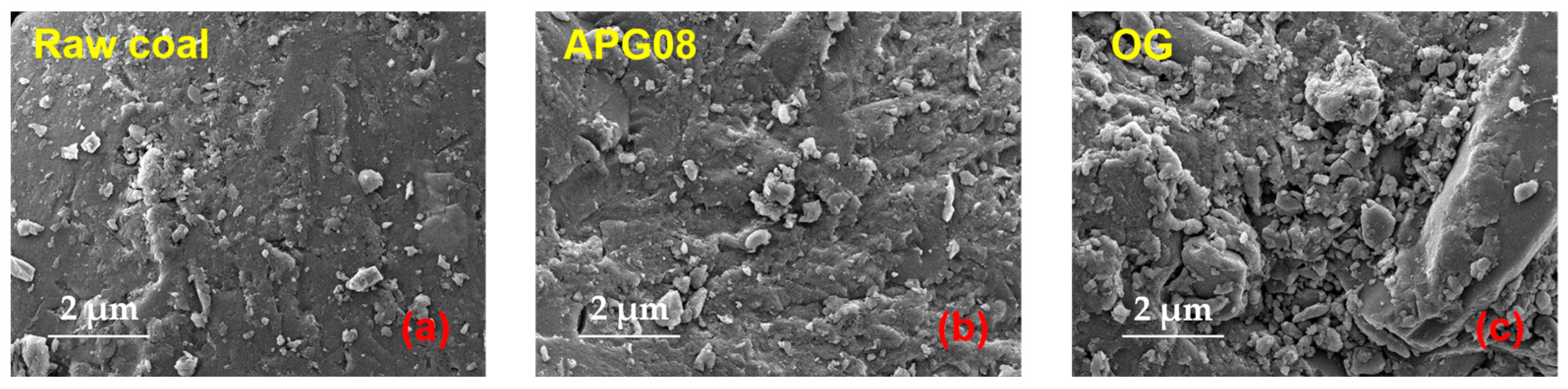

3.2.3. SEM Analysis

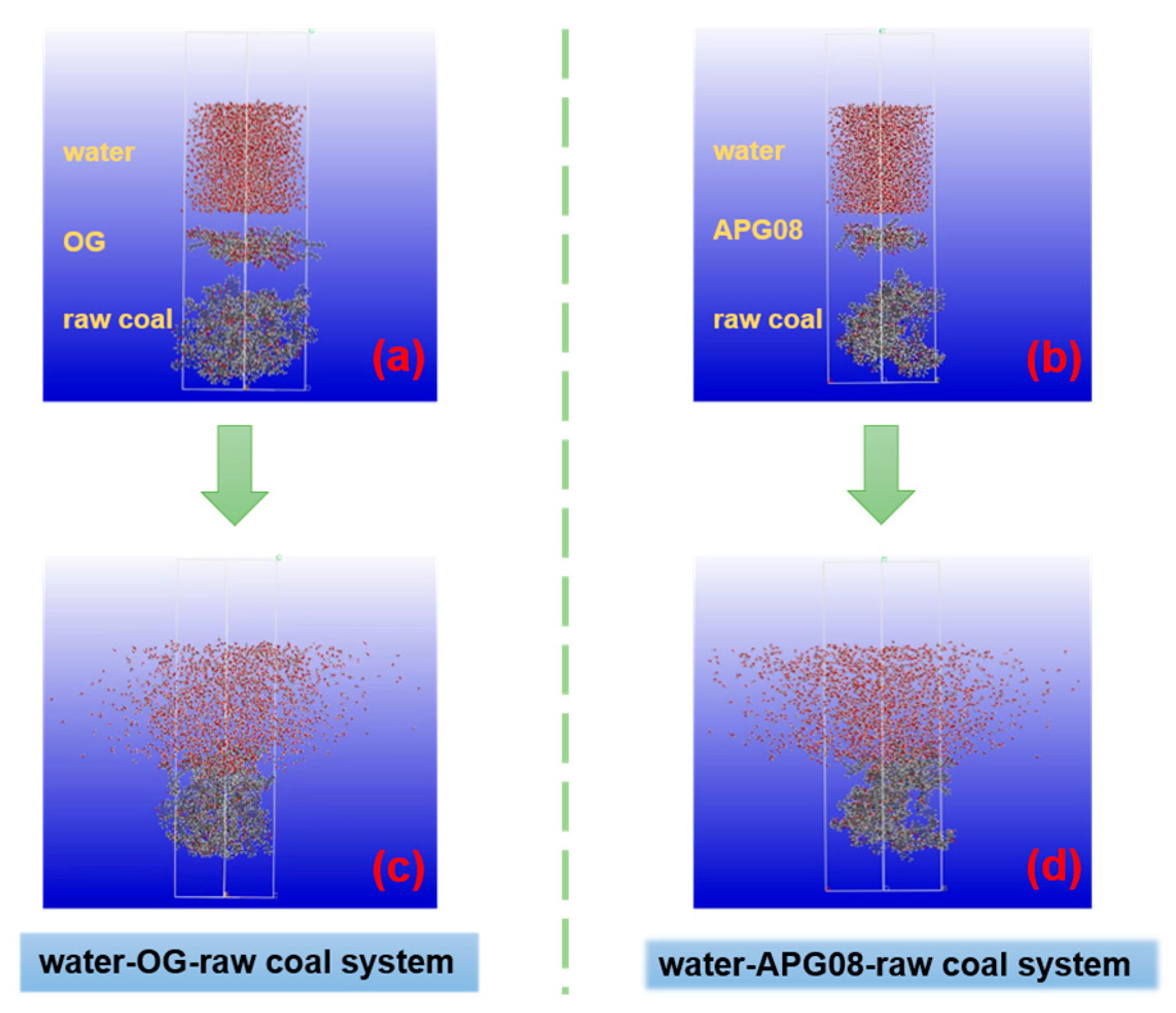

3.3. Molecular Dynamics Simulation

3.3.1. Contact Surface Area

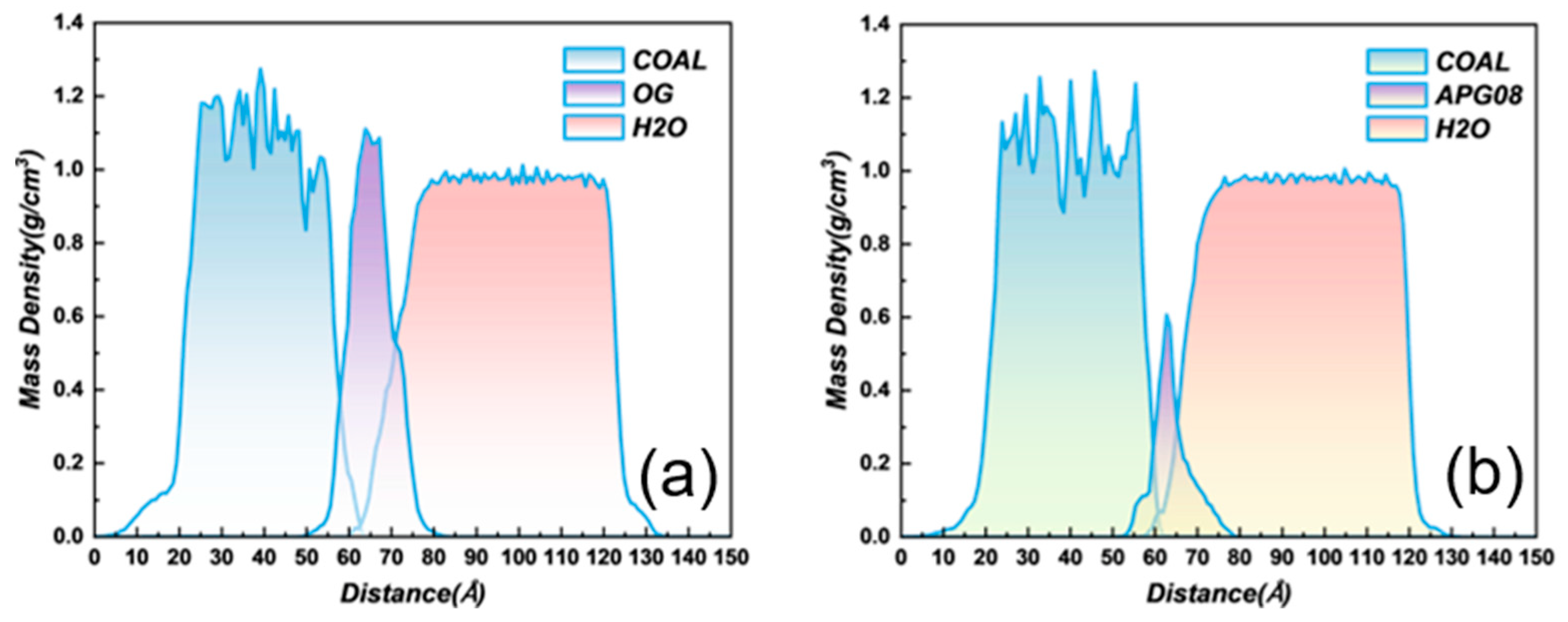

3.3.2. Mass Density Distribution

3.3.3. Interaction Energy

3.3.4. Mean Square Displacement

3.3.5. Number of Hydrogen Bonds

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Liu, G.; Xu, Q.; Zhao, J.; Nie, W.; Guo, Q.; Ma, G. Research Status of Pathogenesis of Pneumoconiosis and Dust Control Technology in Mine—A Review. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 10313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangani, R.G.; Ghio, A.J.; Deepak, V.; Anwar, J.; Vaidya, V.; Patel, Z.; Abdullah, A. Impact of Coal Mine Dust Exposure and Cigarette Smoking on Lung Disease in Appalachian Coalminers. Respir. Res. 2025, 26, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saka, M.B.; Hashim, M.H.M.; Shehu, S.A. Mining Dust: Health Impacts, Control Measures and Future Directions. Environ. Eng. Manag. J. 2025, 24, 407–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Animah, F.; Keles, C.; Reed, W.R.; Sarver, E. Effects of Dust Controls on Respirable Coal Mine Dust Composition and Particle Sizes: Case Studies on Auxiliary Scrubbers and Canopy Air Curtain. Int. J. Coal Sci. Technol. 2024, 11, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbar, K.A.; Kallawicha, K. Black Lung Disease among Coal Miners: First Ever Evidence from Indonesia’s National Coal Production Report. Aerosol Air Qual. Res. 2024, 24, 240161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petavratzi, E.; Kingman, S.; Lowndes, I. Particulates from Mining Operations: A Review of Sources, Effects and Regulations. Miner. Eng. 2005, 18, 1183–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nevskaya, E.E.; Guskov, M.A.; Samylovskaya, E.E. Advanced Risk Assessment in Coal Mines: Integrating Fuzzy Logic and Linguistic Variables for Enhanced Hazard Management. Int. J. Eng. 2025, 38, 2854–2864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleem, H.A.; Ayalew, A.T. Enhancing Environmental Sustainability and Operational Efficiency in a Case Study of Limestone Quarry in an Arid Climate. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 18884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Xia, M.; Bentley, T. The Paradoxical Effects of Emerging Mining Technologies on Psychosocial Work Factors: An Integrated Framework and Research Agenda. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2026, 222, 124391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.-N.; Deng, J.; Xiao, Y. Comprehensive Review of Spray and Ventilation Technologies for Coal Dust Control at Mining Faces. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2025, 195, 106799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Wang, D.; Han, F.; Yang, F.; Sheng, Y. Study and Application on Foam-Water Mist Integrated Dust Control Technology in Fully Mechanized Excavation Face. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2020, 133, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Xu, P.; Liu, S.; Wang, J.; Zhang, L.; Ji, H.; Guo, F.; Li, G. An Experimental Investigation on the Foam Proportion for Coal Dust Suppression in Underground Coal Mines. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2024, 187, 1354–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, R.; Tao, Y.; Chen, J.; Li, S.; Wang, S. Review on Dust Control Technologies in Coal Mines of China. Sustainability 2024, 16, 4038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, W.; Shi, J.; Guo, Q.; Zhao, Q.; Bai, L. The Influence of Dust Particles on the Stability of Foam Used as Dust Control in Underground Coal Mines. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2017, 111, 740–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, J.; Wang, D.; Xiao, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, K.; Zhu, X.; Li, S. Experimental and Molecular Dynamics Investigations of the Effects of Ionic Surfactants on the Wettability of Low-Rank Coal. Energy 2023, 271, 127012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Yuan, S.; Jiang, B. Experimental Investigation of the Wetting Ability of Surfactants to Coals Dust Based on Physical Chemistry Characteristics of the Different Coal Samples. Adv. Powder Technol. 2019, 30, 1696–1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, G.-Q.; Han, C.; Wang, Y.; Wang, H.-T. Experimental Study on Synergistic Wetting of a Coal Dust with Dust Suppressant Compounded with Noncationic Surfactants and Its Mechanism Analysis. Powder Technol. 2019, 356, 1077–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B.; Li, S.; Lin, H.; Cheng, Y.; Kong, X.; Ding, Y. Experimental Study on the Influence of Surfactants in Compound Solution on the Wetting-Agglomeration Properties of Bituminous Coal Dust. Powder Technol. 2022, 395, 766–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, X.; Kong, S.; Zhang, J.; Li, G.; Li, J.; Wen, P.; Yan, G. Molecular Mechanism Study of Nonionic Surfactant Enhanced Anionic Surfactant to Improve the Wetting Ability of Anthracite Dust. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2024, 686, 133455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, W.; Liu, S.; Guo, J.; Zhang, L. Decrease in Hydrophilicity and Inhibition Moisture Re-Adsorption of Lignite Using Binary Surfactant Mixtures with Different Hydrophilic Head-Groups. J. Mol. Liq. 2019, 276, 638–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Zhu, M.; Yang, H.; Zhao, D.; Zhang, K. Study on the Influence of New Compound Reagents on the Functional Groups and Wettability of Coal. Fuel 2021, 302, 121113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Jing, P.; Qu, H.; Huang, L.; Wang, Z.; Liu, C. Study on Wetting Mechanism of Nonionic Silicone Surfactant on Coal Dust. Heliyon 2023, 9, e16184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Yuan, S.; Li, X.; Jiang, B. Synergistic Effect of Surfactant Compounding on Improving Dust Suppression in a Coal Mine in Erdos, China. Powder Technol. 2019, 344, 561–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, K.D.; Danielson, E.P.; Peterson, K.N.; Nocevski, N.O.; Boock, J.T.; Berberich, J.A. The Amphoteric Surfactant N,N-Dimethyldodecylamine N-Oxide Unfolds β-Lactoglobulin above the Critical Micelle Concentration. Langmuir 2022, 38, 4090–4101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Liu, X.; Guo, Z.; Liu, Y.; Guo, J.; Zhang, S. Wettability Modification and Restraint of Moisture Re-Adsorption of Lignite Using Cationic Gemini Surfactant. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2016, 508, 286–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Liu, S.; Cheng, Y.; Xu, G. Decrease in Hydrophilicity and Moisture Readsorption of Lignite: Effects of Surfactant Structure. Fuel 2020, 273, 117812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharmoria, P.; Singh, T.; Kumar, A. Complexation of Chitosan with Surfactant like Ionic Liquids: Molecular Interactions and Preparation of Chitosan Nanoparticles. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2013, 407, 361–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Yan, G.; Kong, S.; Bai, X.; Li, G.; Zhang, J. Molecular Mechanism Study on the Effect of Microstructural Differences of Octylphenol Polyoxyethylene Ether (OPEO) Surfactants on the Wettability of Anthracite. Molecules 2023, 28, 4748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wei, X.; Qiu, C.; Chang, C.; Li, P.; Li, D. Effects of Surface Tension on the Kinetics of Methane Hydrate Formation with APG Additive in an Impinging Stream Reactor. Fuel 2024, 363, 130889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Ma, Z.; Xia, F.; Li, X. Adsorption Behavior of Oil-Displacing Surfactant at Oil/Water Interface: Molecular Simulation and Experimental. J. Water Process Eng. 2020, 36, 101292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Dong, X.; Fan, Y.; Ma, X.; Dong, Y.; Chang, M. Interaction between STAC and Coal/Kaolinite in Tailing Dewatering: An Experimental and Molecular-Simulation Study. Fuel 2020, 279, 118224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, W.; Yang, S.; Yuan, T.-Q.; Charlton, A.; Sun, R.-C. Effects of Various Surfactants on Alkali Lignin Electrospinning Ability and Spun Fibers. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2017, 56, 9551–9559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.-D.; Liu, Y.-F.; Zhou, D.; Yu, W.; Yin, J.-Z. Critical Microemulsion Concentration and Molar Ratio of Water-to-Surfactant of Supercritical CO2 Microemulsions with Commercial Nonionic Surfactants: Experiment and Molecular Dynamics Simulation. J. Chem. Eng. Data 2016, 61, 3135–3143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Wang, D.; Wang, H.; Xin, H.; Ma, L.; Zhu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Q. Effects of Chemical Properties of Coal Dust on Its Wettability. Powder Technol. 2017, 318, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Lin, B.; Zhao, S.; Dai, H. Surface Physical Properties and Its Effects on the Wetting Behaviors of Respirable Coal Mine Dust. Powder Technol. 2013, 233, 137–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alghunaim, A.; Kirdponpattara, S.; Newby, B.Z. Techniques for Determining Contact Angle and Wettability of Powders. Powder Technol. 2016, 287, 201–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabir, H.; Garg, N. Machine Learning Enabled Orthogonal Camera Goniometry for Accurate and Robust Contact Angle Measurements. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 1497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akintola, G.O.; Amponsah-Dacosta, F.; Rupprecht, S.; Palaniyandy, N.; Mhlongo, S.E.; Gitari, W.M.; Edokpayi, J.N. Methanogenesis Potentials: Insights from Mineralogical Diagenesis, SEM and FTIR Features of the Permian Mikambeni Shale of the Tuli Basin, Limpopo Province of South Africa. Minerals 2021, 11, 651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, R.L.T.; Cauda, E.; Chubb, L.; Krebs, P.; Stach, R.; Mizaikoff, B.; Johnston, C. Complexity of Respirable Dust Found in Mining Operations as Characterized by X-Ray Diffraction and FTIR Analysis. Minerals 2021, 11, 383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Amico, F.; Musso, M.E.; Berger, R.J.F.; Cefarin, N.; Birarda, G.; Tondi, G.; Bertoldo Menezes, D.; Reyer, A.; Scarabattoli, L.; Sepperer, T.; et al. Chemical Constitution of Polyfurfuryl Alcohol Investigated by FTIR and Resonant Raman Spectroscopy. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2021, 262, 120090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandt, C.; Waeytens, J.; Deniset-Besseau, A.; Nielsen-Leroux, C.; Réjasse, A. Use and Misuse of FTIR Spectroscopy for Studying the Bio-Oxidation of Plastics. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2021, 258, 119841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aschaffenburg, D.J.; Kawasaki, S.; Pemmaraju, C.D.; Cuk, T. Accuracy in Resolving the First Hydration Layer on a Transition-Metal Oxide Surface: Experiment (AP-XPS) and Theory. J. Phys. Chem. C 2020, 124, 21407–21417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Zhou, G.; Li, S.; Wang, C.; Liu, R.; Jiang, W. Molecular Dynamics Simulation and Experimental Characterization of Anionic Surfactant: Influence on Wettability of Low-Rank Coal. Fuel 2020, 279, 118323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yang, J.; Pan, Z.; Tong, W. Nanoscale Pore Structure and Mechanical Property Analysis of Coal: An Insight Combining AFM and SEM Images. Fuel 2020, 260, 116352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Wang, C.; Yan, K. Adsorption of Collectors on Model Surface of Wiser Bituminous Coal: A Molecular Dynamics Simulation Study. Miner. Eng. 2015, 79, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, J.; Wang, L.; Wang, J.; Lyu, C.; Zhang, S.; Nie, B. Molecular Mechanism of Influence of Alkyl Chain Length in Ionic Surfactant on the Wettability of Low Rank Coal. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2024, 680, 132661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, J.; Wang, L.; Lyu, C.; Wang, J.; Lyu, Y.; Nie, B. Molecular Simulation of the Regulation Mechanism of the Hydrophilic Structure of Surfactant on the Wettability of Bituminous Coal Surface. J. Mol. Liq. 2023, 383, 122185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisuzzo, L.; Cavallaro, G.; Pasbakhsh, P.; Milioto, S.; Lazzara, G. Why Does Vacuum Drive to the Loading of Halloysite Nanotubes? The Key Role of Water Confinement. J. Colloid. Interface Sci. 2019, 547, 361–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, B.; Xia, W.; Niu, C. Comparison of Pyrolysis and Oxidation Actions on Chemical and Physical Property of Anthracite Coal Surface. Adv. Powder Technol. 2020, 31, 2447–2455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Liu, S.; Fan, M.; Guo, J.; Li, B. Decrease in Hydrophilicity and Moisture Readsorption of Manglai Lignite Using Lauryl Polyoxyethylene Ether: Effects of the HLB and Coverage on Functional Groups and Pores. Fuel Process. Technol. 2018, 174, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Wu, X.; Gao, J.; Li, G. Surface Characteristics and Wetting Mechanism of Respirable Coal Dust. Min. Sci. Technol. 2010, 20, 365–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Gao, J.; Deng, C.; Ge, S.; Fan, C.; Zhang, W. Experimental Study on Chemical Structure and Wetting Influence of Imidazole Ionic Liquids on Coal. Fuel 2022, 330, 125545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, C.; Xia, W.; Peng, Y. Analysis of Coal Wettability by Inverse Gas Chromatography and Its Guidance for Coal Flotation. Fuel 2018, 228, 290–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Yan, G.; Zhou, Y.; Xu, G.; Bai, X.; Li, J. Molecular Mechanism Study on the Effect of Nonionic Surfactants with Different Degrees of Ethoxylation on the Wettability of Anthracite. Chemosphere 2023, 310, 136902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, X.; You, X.; He, M.; Zhang, W.; Wei, H.; Li, L.; He, Q. Adsorption and Molecular Dynamics Simulations of Nonionic Surfactant on the Low Rank Coal Surface. Fuel 2018, 211, 529–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Kalinichev, A.G.; Kirkpatrick, R.J. Molecular Modeling of Water Structure in Nano-Pores between Brucite (001) Surfaces1. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2004, 68, 3351–3365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anvari, M.H.; Liu, Q.; Xu, Z.; Choi, P. Molecular Dynamics Study of Hydrophilic Sphalerite (110) Surface as Modified by Normal and Branched Butylthiols. Langmuir 2018, 34, 3363–3373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Li, H.; Gao, M.; Ye, S.; Zhao, Y.; Xie, J.; Liu, G.; Liu, J.; Li, L.-M.; Deng, J.; et al. Experimental and Molecular Dynamics Study into the Surfactant Effect upon Coal Wettability. RSC Adv. 2021, 11, 24543–24555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Zhang, M.; Yang, H.; Zhu, M.; Jiao, L.; Xu, Y.; Jiao, L. Molecular Simulation of the Regulation Mechanism of Surfactant on Microscopic Chemical Wetting of Coal. J. Mol. Liq. 2024, 404, 124896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, X.; He, M.; Zhang, W.; Wei, H.; Lyu, X.; He, Q.; Li, L. Molecular Dynamics Simulations of Nonylphenol Ethoxylate on the Hatcher Model of Subbituminous Coal Surface. Powder Technol. 2018, 332, 323–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.; Xing, M.; Wang, K.; Wang, Q.; Xu, Z.; Li, L.; Cheng, W. Study on Wetting Behavior between CTAC and BS-12 with Gas Coal Based on Molecular Dynamics Simulation. J. Mol. Liq. 2022, 357, 118996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.; Xu, S.; Wang, G.; Tang, Q.; Jiang, X.; Li, Z.; Xu, Y.; Wang, R.; Lin, F. Proposed Hydrogen-Bonding Index of Donor or Acceptor Reflecting Its Intrinsic Contribution to Hydrogen-Bonding Strength. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2017, 57, 1535–1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Surfactant | Molecular Formula | Molecular Weight (g mol−1) | CMC (mg L−1) | Molecular Structure |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OG | C14H28O6 | 292.37 | 1300 |  |

| APG08 | C14H28O6 | 292.37 | 1300 |  |

| Surfactant | θi (°) | k (s−n) | n | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H2O | 71.3 | 0.1447 ± 0.0147 | 0.4179 | 0.9587 |

| APG08 | 49.2 | 0.2039 ± 0.0123 | 0.3239 | 0.9743 |

| OG | 36.5 | 0.4727 ± 0.0236 | 0.2093 | 0.9662 |

| Functional Groups | Raw Coal | APG08 | OG | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peak (BE) | FWHM (EV) | Atomic (%) | Peak (BE) | FWHM (EV) | Atomic (%) | Peak (BE) | FWHM (EV) | Atomic (%) | ||

| C1s | C–C/C–H(%) | 284.80 | 1.51 | 76.21 | 284.80 | 1.56 | 73.60 | 284.80 | 1.59 | 70.44 |

| C–O(%) | 286.44 | 1.48 | 12.04 | 286.50 | 1.55 | 18.19 | 286.54 | 1.33 | 19.62 | |

| C=O(%) | 288.11 | 3.37 | 7.16 | 288.21 | 1.91 | 6.07 | 288.01 | 1.96 | 8.09 | |

| O=C–O(%) | 290.46 | 3.27 | 4.59 | 290.33 | 1.91 | 2.14 | 290.37 | 1.96 | 1.65 | |

| O1s | C=O(%) | 532.23 | 2.02 | 69.92 | 532.37 | 2.67 | 60.42 | 532.66 | 2.24 | 63.00 |

| C–O/OH(%) | 533.54 | 1.61 | 26.79 | 533.14 | 1.74 | 35.37 | 533.15 | 1.53 | 29.85 | |

| COO/COOH(%) | 534.68 | 3.37 | 3.29 | 534.27 | 3.37 | 4.21 | 534.04 | 2.40 | 7.15 | |

| Model | EE (kcal mol−1) | EV (kcal mol−1) | E (kcal mol−1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| OG System | −1636 | −347 | −1983 |

| APG08 System | −1275 | −512 | −1787 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, B.; Yan, G.; Kong, S.; Wu, K.; Wang, Y. Molecular Mechanisms by Which Linear Versus Branched Alkyl Chains in Nonionic Surfactants Govern the Wettability of Long-Flame Coal. Molecules 2025, 30, 4686. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244686

Li B, Yan G, Kong S, Wu K, Wang Y. Molecular Mechanisms by Which Linear Versus Branched Alkyl Chains in Nonionic Surfactants Govern the Wettability of Long-Flame Coal. Molecules. 2025; 30(24):4686. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244686

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Boyu, Guochao Yan, Shaoqi Kong, Kuangkuang Wu, and Yanheng Wang. 2025. "Molecular Mechanisms by Which Linear Versus Branched Alkyl Chains in Nonionic Surfactants Govern the Wettability of Long-Flame Coal" Molecules 30, no. 24: 4686. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244686

APA StyleLi, B., Yan, G., Kong, S., Wu, K., & Wang, Y. (2025). Molecular Mechanisms by Which Linear Versus Branched Alkyl Chains in Nonionic Surfactants Govern the Wettability of Long-Flame Coal. Molecules, 30(24), 4686. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244686