Lighting Up DNA in the Near-Infrared: An Os(II)–pydppn Complex with Light-Switch Behavior

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

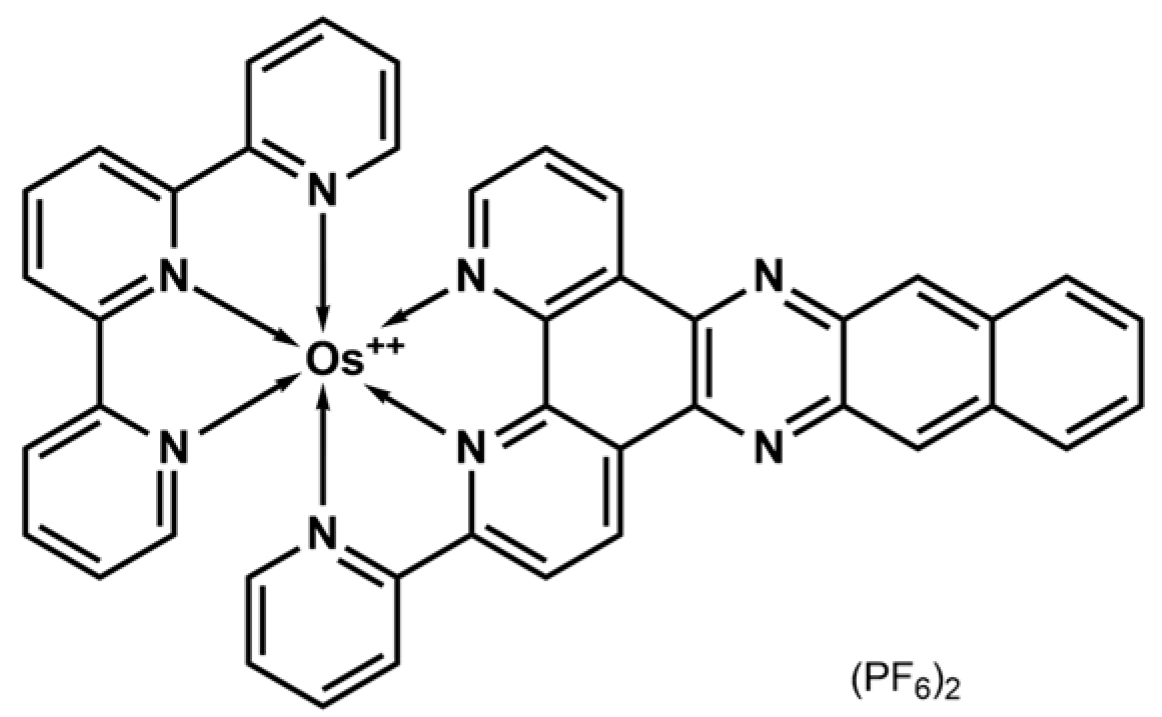

2.1. Synthesis and Characterization

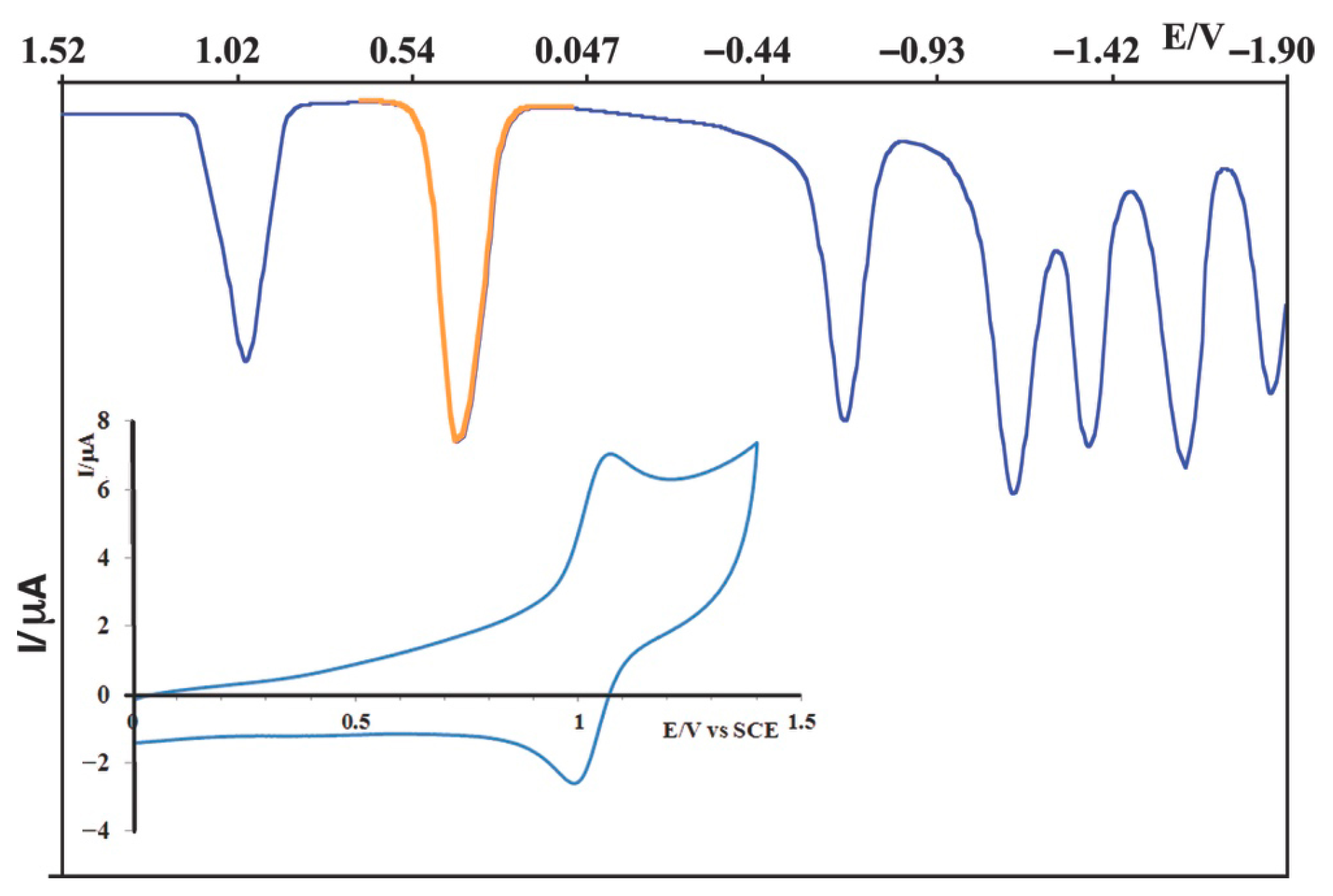

2.2. Redox Properties

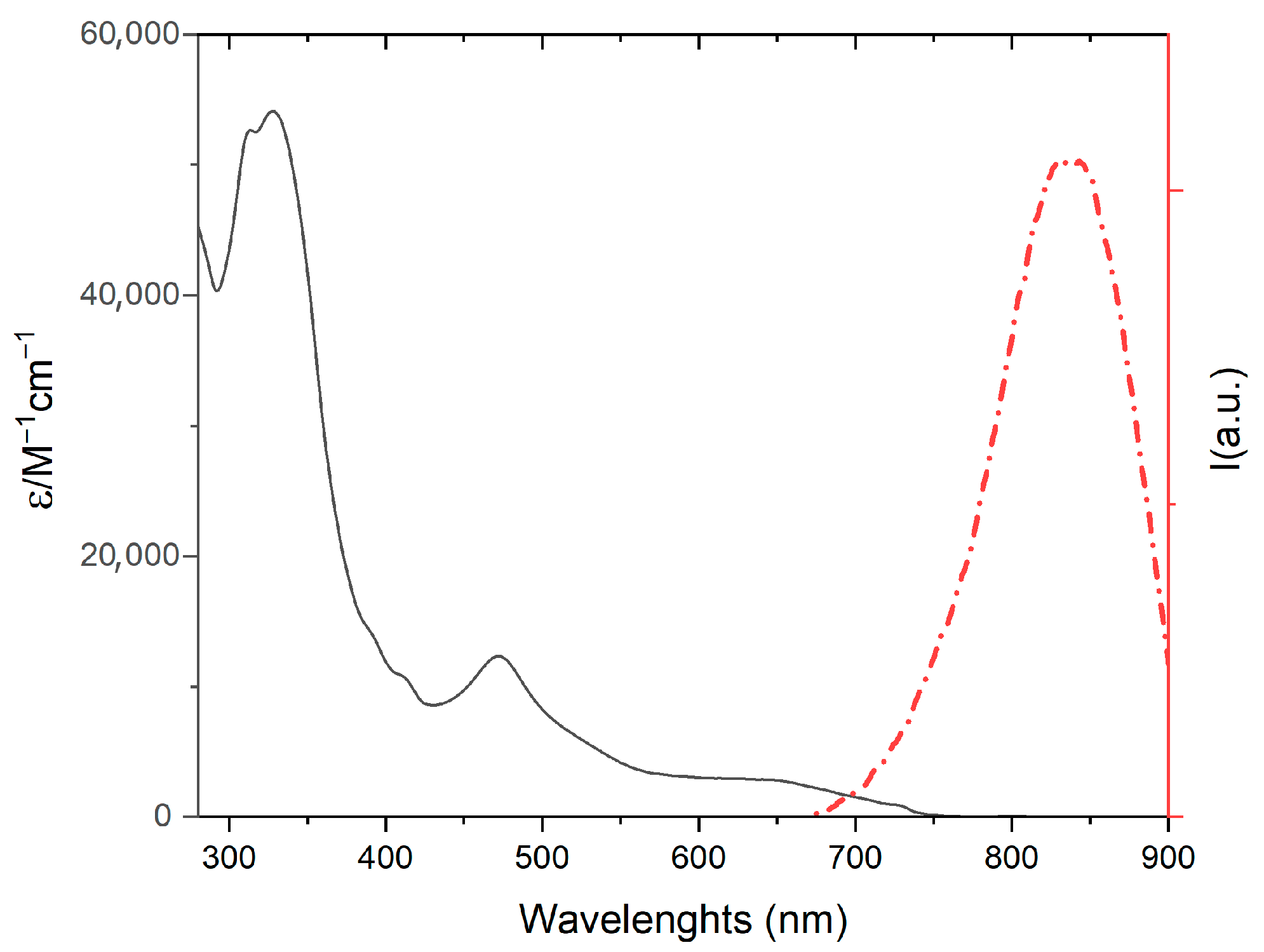

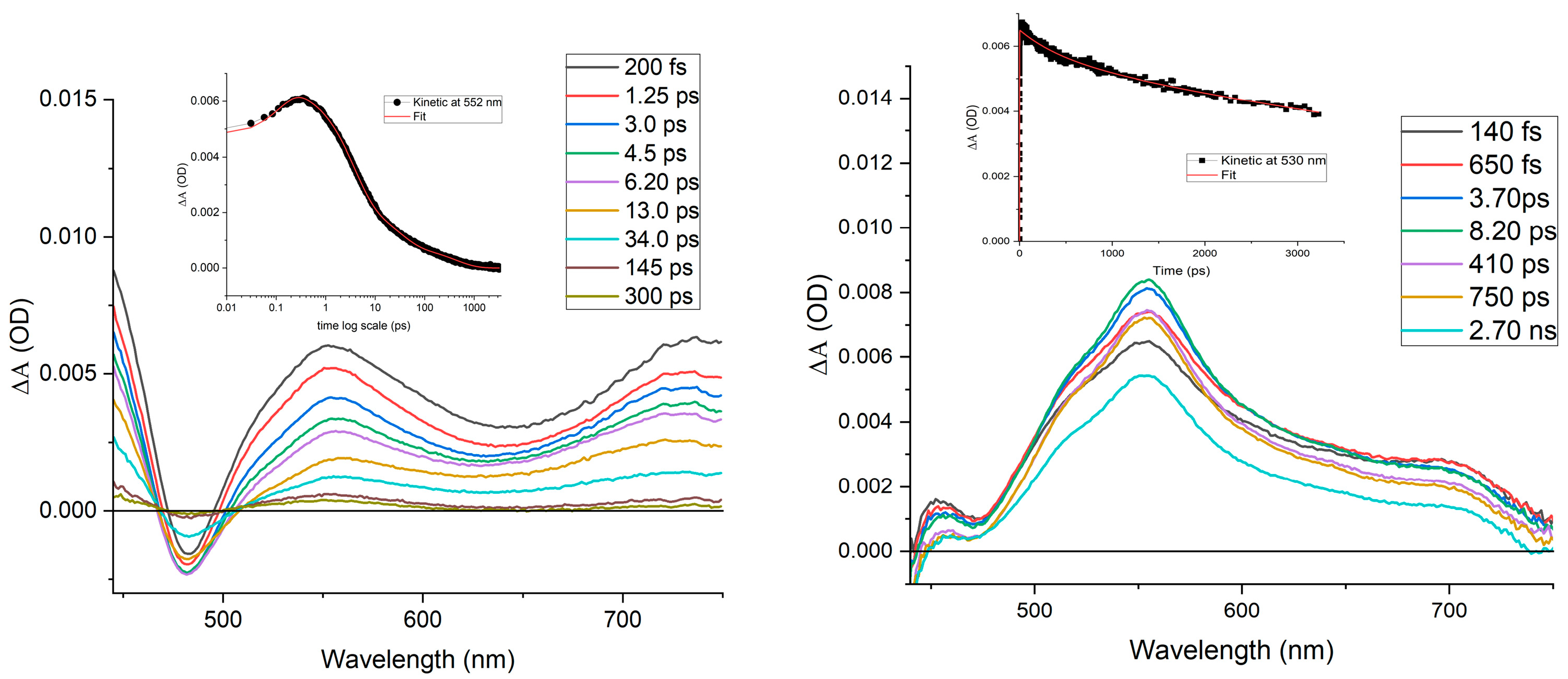

2.3. Spectroscopic and Photophysical Properties

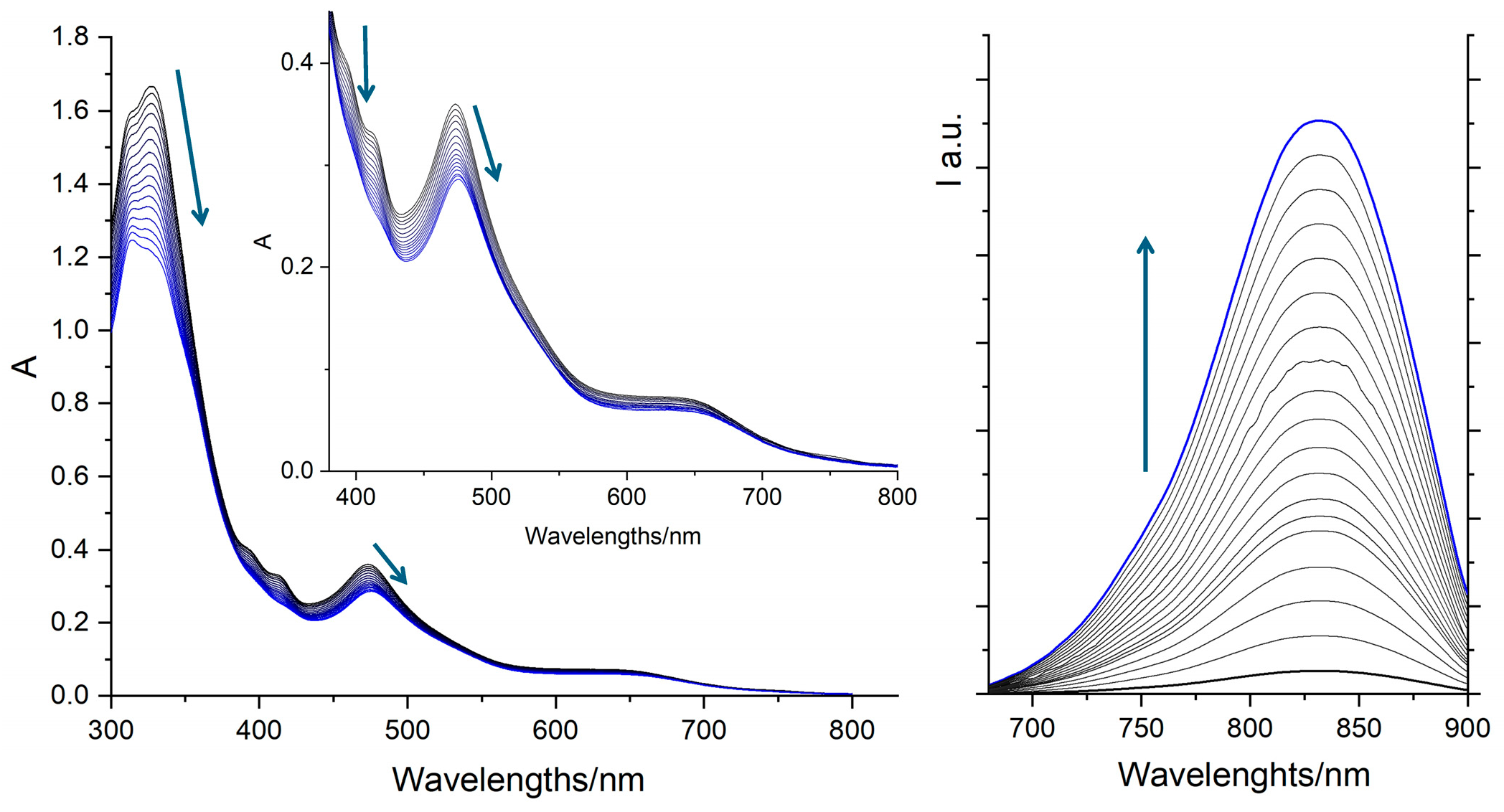

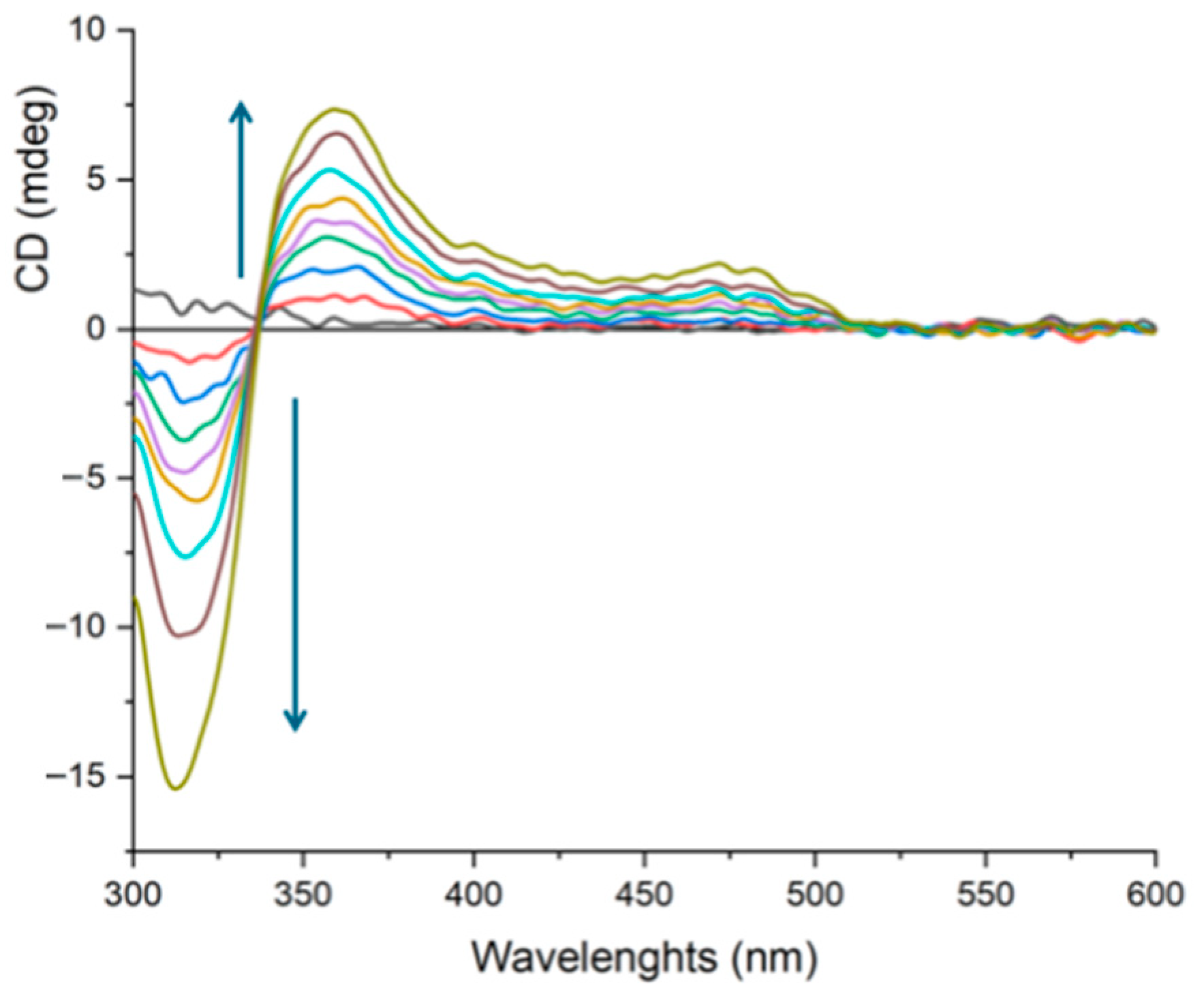

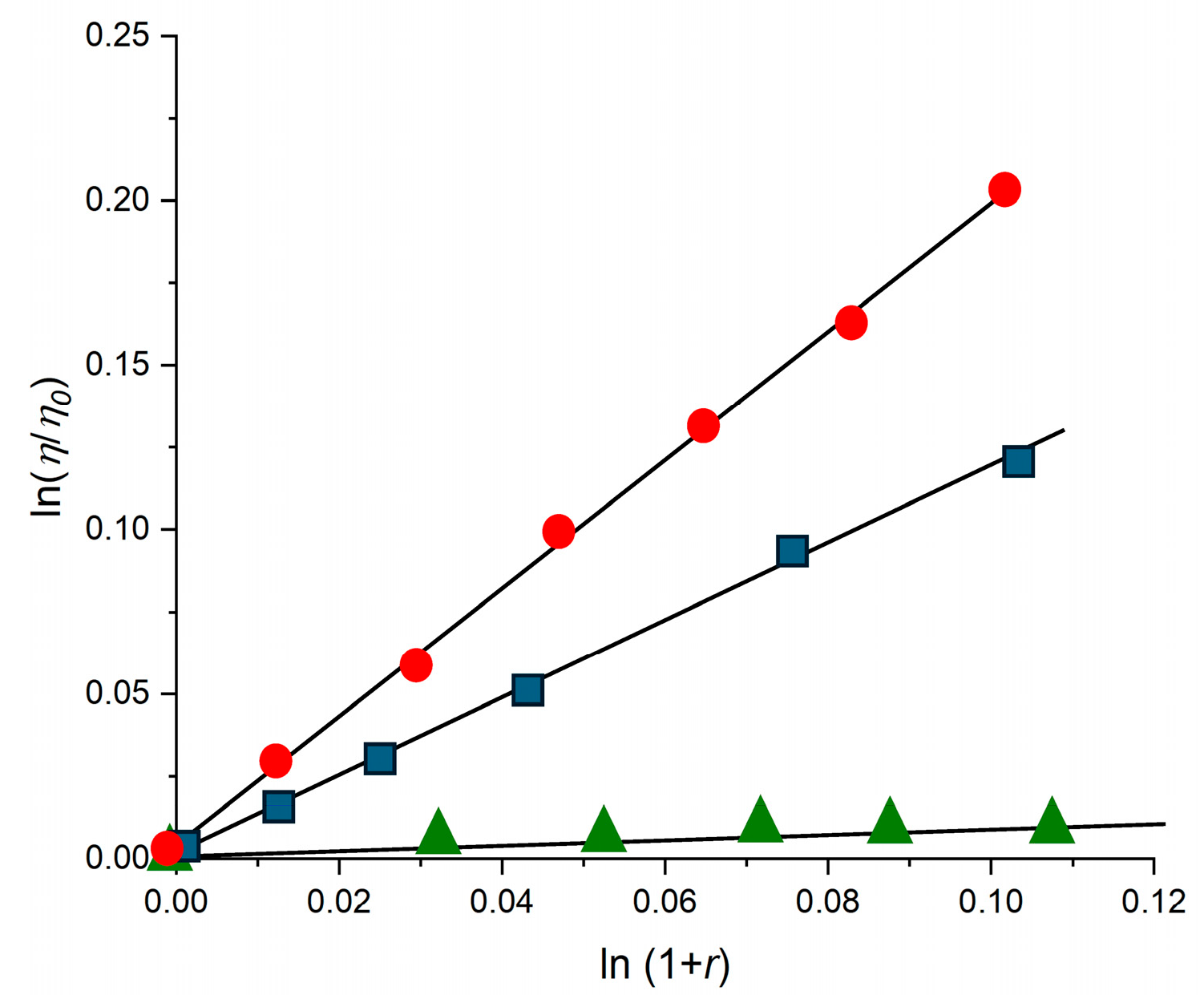

2.4. DNA Interaction: The “Light-Switch” Effect

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Chemicals

3.2. Synthesis Procedures

3.3. Instrumentations

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Friedman, A.E.; Chambron, J.C.; Sauvage, J.P.; Turro, N.J.; Barton, J.K. A molecular light switch for DNA: Ru(bpy)2(dppz)2+. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1990, 112, 4960–4962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Lutterman, D.A.; Turro, C. Role of electronic structure on DNA light switch behavior of Ru(II) intercalators. Inorg. Chem. 2008, 47, 6427–6434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Pietro, M.L.; La Ganga, G.; Puntoriero, F.; Nastasi, F. Ru(II)-Dppz derivatives and their interactions with DNA: Thirty years and counting. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 3038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Hammitt, R.; Lutterman, D.A.; Joyce, L.E.; Thummel, R.P.; Turro, C. Ru(II) Complexes of New Tridentate Ligands: Unexpected High Yield of Sensitized 1O2. Inorg. Chem. 2009, 48, 375–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, J.P.; Keane, P.M.; Beer, H.; Buchner, K.; Winter, G.; Sorensen, T.L.; Cardin, D.J.; Brazier, J.A.; Cardin, C.J. Delta chirality ruthenium ‘light-switch’ complexes can bind in the minor groove of DNA with five different binding modes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016, 44, 9472–9482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olofsson, J.; Önfelt, B.; Lincoln, P. Three-State Light Switch of [Ru(phen)2dppz]2+: Distinct Excited-State Species with Two, One, or No Hydrogen Bonds from Solvent. J. Phys. Chem. A 2004, 108, 4391–4398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, M.-J.; Duan, Z.-M.; Hao, Q.; Zheng, S.-Z.; Wang, K.-Z. Molecular Light Switches for Calf Thymus DNA Based on Three Ru(II) Bipyridyl Complexes with Variations of Heteroatoms. J. Phys. Chem. C 2007, 111, 16577–16585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Zhou, Q.; Jiao, Z.; Zhao, H.; Huang, C.-H.; Zhu, B.-Z.; Su, H. Ultrafast excited state dynamics and light-switching of [Ru(phen)2(dppz)]2+ in G-quadruplex DNA. Commun. Chem. 2021, 4, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Sun, L.; Ji, L.; Chao, H. Ruthenium(II) complexes with dppz: From molecular photoswitch to biological applications. Dalton Trans. 2016, 45, 13261–13276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graczyk, D.; Cowin, R.A.; Chekulaev, D.; Haigh, M.A.; Scattergood, P.A.; Quinn, S.J. Study of the Photophysical Properties and the DNA Binding of Enantiopure [Cr(TMP)2(dppn)]3+ Complex. Inorg. Chem. 2024, 63, 23620–23629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stitch, M.; Boota, R.Z.; Chalkley, A.S.; Keene, T.D.; Simpson, J.C.; Scattergood, P.A.; Elliott, P.I.P.; Quinn, S.J. Photophysical Properties and DNA Binding of Two Intercalating Osmium Polypyridyl Complexes Showing Light-Switch Effects. Inorg. Chem. 2022, 61, 14947–14961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moucheron, C.; Kirsch-De Mesmaeker, A.; Kelly, J.M. Photoreactions of ruthenium(II) and osmium(II) complexes with deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA). J. Photochem. Photobiol. B 1997, 40, 91–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes, J.B.; Kuimova, M.K.; Vilar, R. Metal complexes as optical probes for DNA sensing and imaging. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2021, 61, 179–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Joyce, L.E.; Dickson, N.M.; Turro, C. Efficient DNA photocleavage by [Ru(bpy)2(dppn)]2+ with visible light. Chem. Commun. 2010, 46, 2426–2428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, R.; Hammitt, R.; Thummel, R.P.; Liu, Y.; Turro, C.; Snapka, R.M. Nuclear targets of photodynamic tridentate ruthenium complexes. Dalton Trans. 2009, 10926–10931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Hammitt, R.; Lutterman, D.A.; Thummel, R.P.; Turro, C. Marked Differences in Light-Switch Behavior of Ru(II) Complexes Possessing a Tridentate DNA Intercalating Ligand. Inorg. Chem. 2007, 46, 6011–6021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinke, S.J.; Dunbar, M.N.; Amalfi Suarez, M.A.; Turro, C. Ru(II) Complexes with Absorption in the Photodynamic Therapy Window: 1O2 Sensitization, DNA Binding, and Plasmid DNA Photocleavage. Inorg. Chem. 2024, 63, 11450–11458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knoll, J.D.; Turro, C. Control and utilization of ruthenium and rhodium metal complex excited states for photoactivated cancer therapy. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2015, 282–283, 110–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terek, S.; Milovanović, M. Ab initio multireference calculation of electronic spectra of the osmium complexes, [Os(bpy)3]2+ and [Os(phen)3]2+. J. Comput. Chem. 2024, 45, 1750–1761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Omar, S.A.E.; Scattergood, P.A.; McKenzie, L.K.; Jones, C.; Patmore, N.; Meijer, A.J.H.M.; Weinstein, J.A.; Rice, C.R.; Bryant, H.E.; Elliott, P.I. Photophysical and Cellular Imaging Studies of Brightly Luminescent Osmium(II) Pyridyltriazole Complexes. Inorg. Chem. 2018, 57, 13201–13212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chi, Y.; Chou, P.-T. Contemporary progresses on neutral, highly emissive Os(II) and Ru(II) complexes. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2007, 36, 1421–1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Shafi, A.A.; Worrall, D.R.; Ershov, A.Y. Photosensitized generation of singlet oxygen from ruthenium(II) and osmium(II) bipyridyl complexes. Dalton Trans. 2004, 30, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mani, A.; Feng, T.; Gandioso, A.; Vinck, R.; Notaro, A.; Gourdon, L.; Burckel, P.; Saubaméa, B.; Blacque, O.; Cariou, K.; et al. Structurally Simple Osmium(II) Polypyridyl Complexes as Photosensitizers for Photodynamic Therapy in the Near Infrared. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2023, 62, e202218347, For German version see Angew. Chem. 2023, 135, e202218347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitz, M.; Naumann, R.; Heinze, K.; Kerzig, C. Efficient Red Light-Driven Singlet Oxygen Photocatalysis with an Osmium-Based Coulombic Dyad. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2025, 64, e202502840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trovato, E.; Di Pietro, M.L.; Puntoriero, F. Shining a New Light on an Old Game—An OsII-Based Near-IR Light Switch. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2012, 2012, 3984–3988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonnet, S. Ruthenium-based photoactivated chemotherapy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2023, 145, 23397–23415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poynton, F.E.; Bright, S.A.; Blasco, S.; Williams, D.C.; Kelly, J.M.; Gunnlaugsson, T. The development of ruthenium(ii) polypyridyl complexes and conjugates for in vitro cellular and in vivo applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2017, 46, 7706–7756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, L.C.; Lo, K.K. Shining new light on biological systems: Luminescent transition metal complexes for bioimaging and biosensing applications. Chem. Rev. 2024, 124, 8825–9014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sauvage, J.-P.; Collin, J.-C.; Chambron, J.-C.; Guillerez, S.; Coudret, C.; Balzani, V.; Barigelletti, F.; De Cola, L.; Flamigni, L. Ruthenium(II) and Osmium(II) bis(terpyridine) complexes in covalently-linked multicomponent systems: Synthesis, electrochemical behavior, absorption spectra, and photochemical and photophysical properties. Chem. Rev. 1994, 94, 993–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barigelletti, F.; Flamigni, L.; Balzani, V.; Sauvage, J.-P.; Collin, J.-C.; Sour, A.; Constable, E.C.; Thompson, A.M.W.C. Rigid rod-like dinuclear Ru(II)/Os(II) terpyridine-type complexes: Electrochemical behaviour, absorption spectra, luminescence properties, and electronic energy transfer through phenylene bridges. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1994, 116, 7692–7699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cullen, A.A.; Long, C.; Pryce, M.T. Explaining the role of water in the “light-switch” probe for DNA intercalation: Modelling water loss from [Ru(phen)2(dppz)]2+·2H2O using DFT and TD-DFT methods. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 2021, 410, 113169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutterman, D.A.; Chouai, A.; Liu, Y.; Sun, Y.; Stewart, C.D.; Dunbar, K.R.; Turro, C. Intercalation Is Not Required for DNA Light-Switch Behavior. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 1163–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campagna, S.; Cavazzini, M.; Cusumano, M.; Di Pietro, M.L.; Giannetto, A.; Puntoriero, F.; Quici, S. Luminescent Ir(III) Complex Exclusively Made of Polypyridine Ligands Capable of Intercalating into Calf-Thymus DNA. Inorg. Chem. 2011, 50, 10667–10672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Satyanarayana, S.; Dabrowiak, J.C.; Chaires, J.B. Neither Δ- nor Λ-Tris(phenanthroline)ruthenium(II) Binds to DNA by Classical Intercalation. Biochemistry 1992, 31, 9319–9324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGhee, J.D.; von Hippel, P.H. Theoretical aspects of DNA-protein interactions: Co-operative and non-co-operative binding of large ligands to a one-dimensional homogeneous lattice. J. Mol. Biol. 1974, 86, 469–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasternack, R.F.; Gibbs, E.J.; Villafranca, J.J. Interactions of porphyrins with nucleic acids. Biochemistry 1983, 22, 2406–2414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, R.D.; Larson, J.E.; Grant, R.C.; Shortle, B.E.; Cantor, C.R. Physicochemical studies on polydeoxyribonucleotides containing defined repeating nucleotide sequences. J. Mol. Biol. 1970, 54, 465–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zigler, D.F.; Mongelli, M.T.; Jeletic, M.; Brewer, K.J. A trimetallic supramolecular complex of osmium(II) and rhodium(III) displaying MLCT transitions in the near-IR. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2007, 10, 295–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demas, J.N.; Crosby, G.A. Measurement of photoluminescence quantum yields. Review. J. Phys. Chem. 1971, 75, 991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| E1/2 ox/V vs. SCE | E1/2 red/V vs. SCE | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | +0.99 [1] | −0.67 [1]; −1.08 [1]; −1.32 [1]; −1.56 [1]; −1.83 [1] |

| MOD [b] | +0.89 [1] | –0.88 [1]; –1.21 [1]; –1.36 [1]; –1.53 [1] |

| Absorption | Luminescence | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| λmax [nm](ε [M−1cm−1]) | λmax [nm] | Φ | τ [ns] | |

| 1 | 328 (54,100) 473 (11,900) | 830 | 0.02 | 110 |

| MOD | 325 (50,500) 375 (22,100) 475 (14,600) | 800 | 0.008 | 50 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Trovato, E.; Genovese, S.; Galletta, M.; Campagna, S.; Di Pietro, M.L.; Puntoriero, F. Lighting Up DNA in the Near-Infrared: An Os(II)–pydppn Complex with Light-Switch Behavior. Molecules 2025, 30, 4671. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244671

Trovato E, Genovese S, Galletta M, Campagna S, Di Pietro ML, Puntoriero F. Lighting Up DNA in the Near-Infrared: An Os(II)–pydppn Complex with Light-Switch Behavior. Molecules. 2025; 30(24):4671. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244671

Chicago/Turabian StyleTrovato, Emanuela, Salvatore Genovese, Maurilio Galletta, Sebastiano Campagna, Maria Letizia Di Pietro, and Fausto Puntoriero. 2025. "Lighting Up DNA in the Near-Infrared: An Os(II)–pydppn Complex with Light-Switch Behavior" Molecules 30, no. 24: 4671. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244671

APA StyleTrovato, E., Genovese, S., Galletta, M., Campagna, S., Di Pietro, M. L., & Puntoriero, F. (2025). Lighting Up DNA in the Near-Infrared: An Os(II)–pydppn Complex with Light-Switch Behavior. Molecules, 30(24), 4671. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244671