Metallomic Aspects of Stroke and Recovery: ICP-MS Study with Chemometric Analysis

Abstract

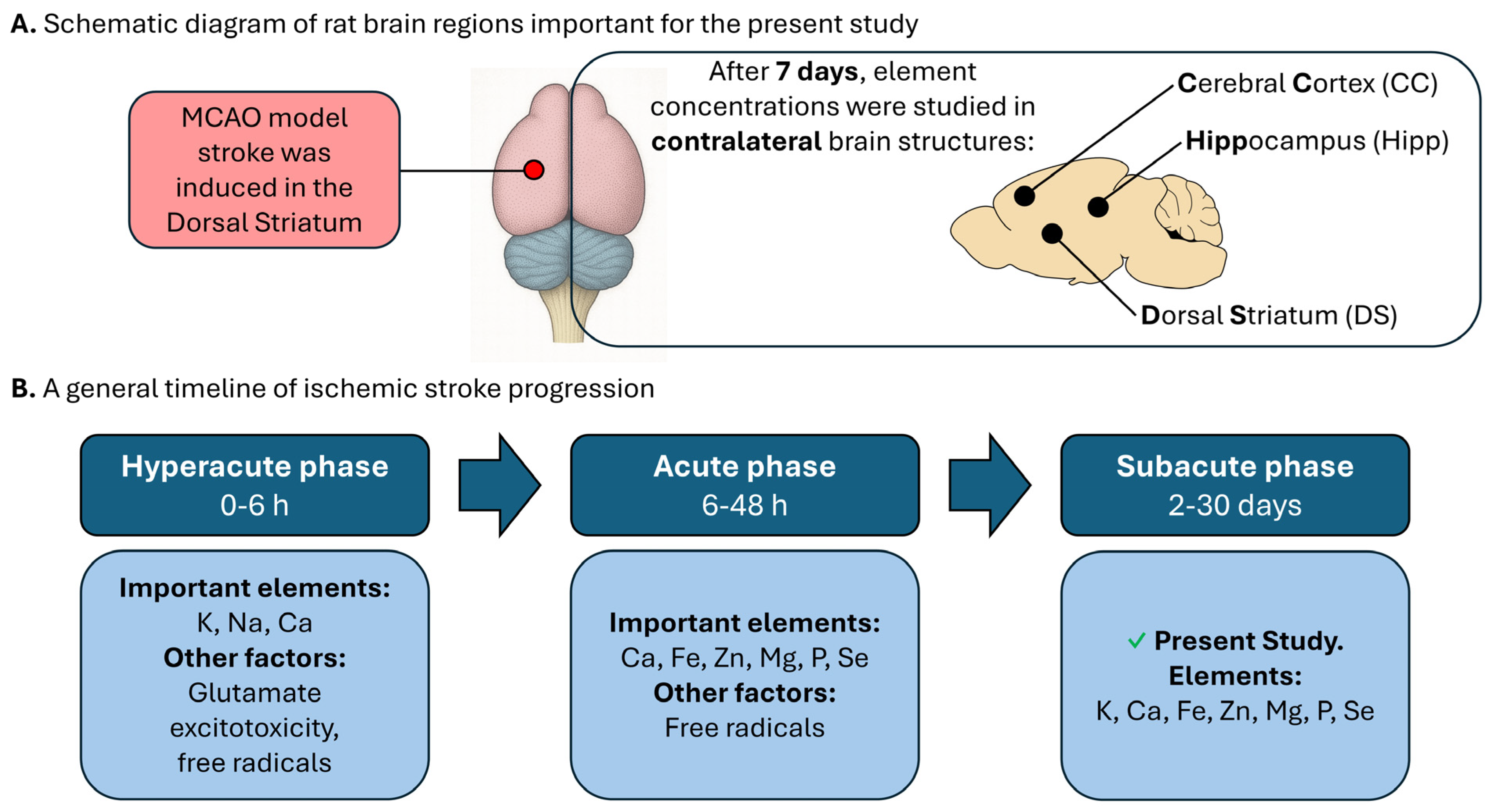

1. Introduction

2. Results

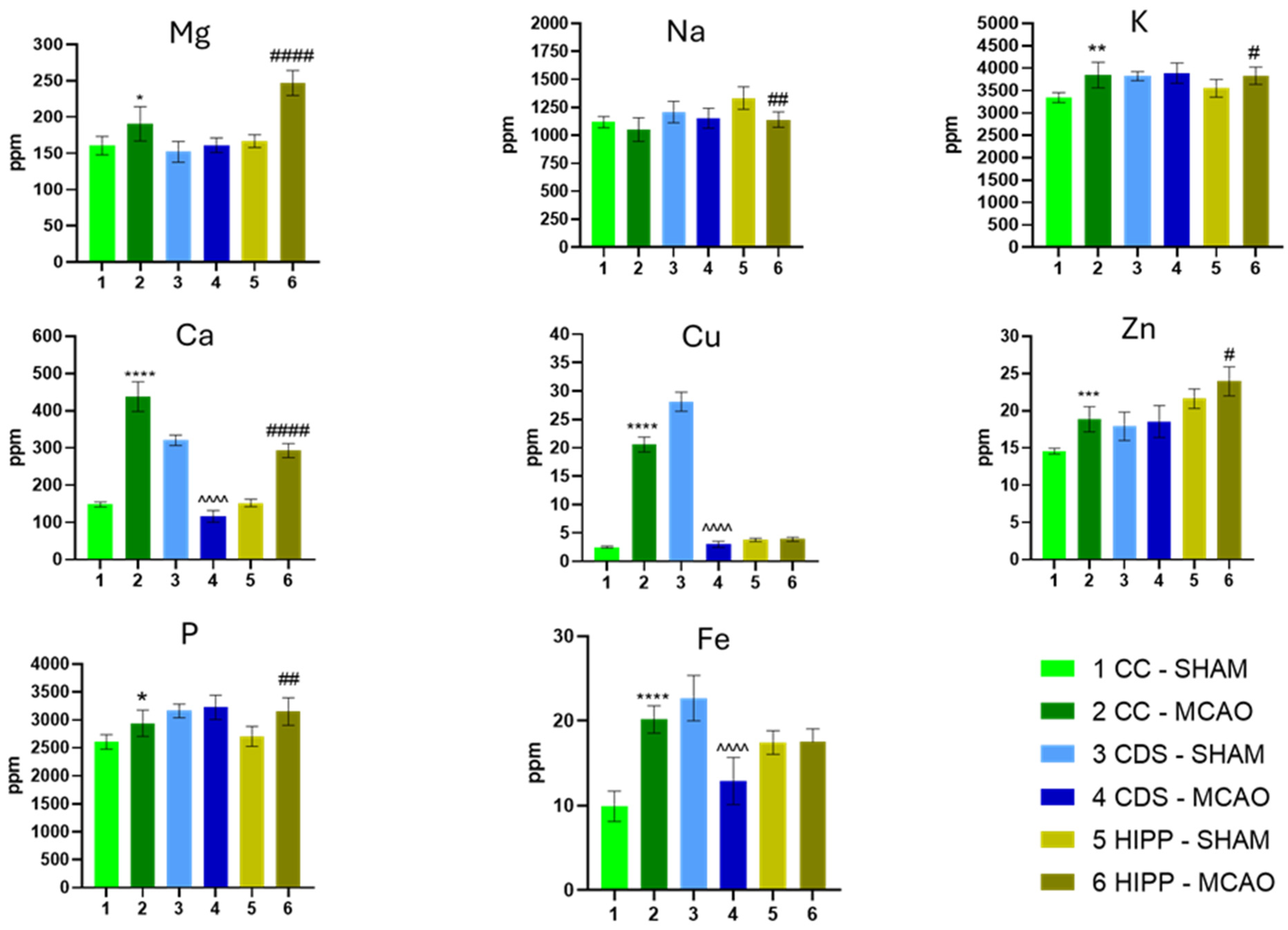

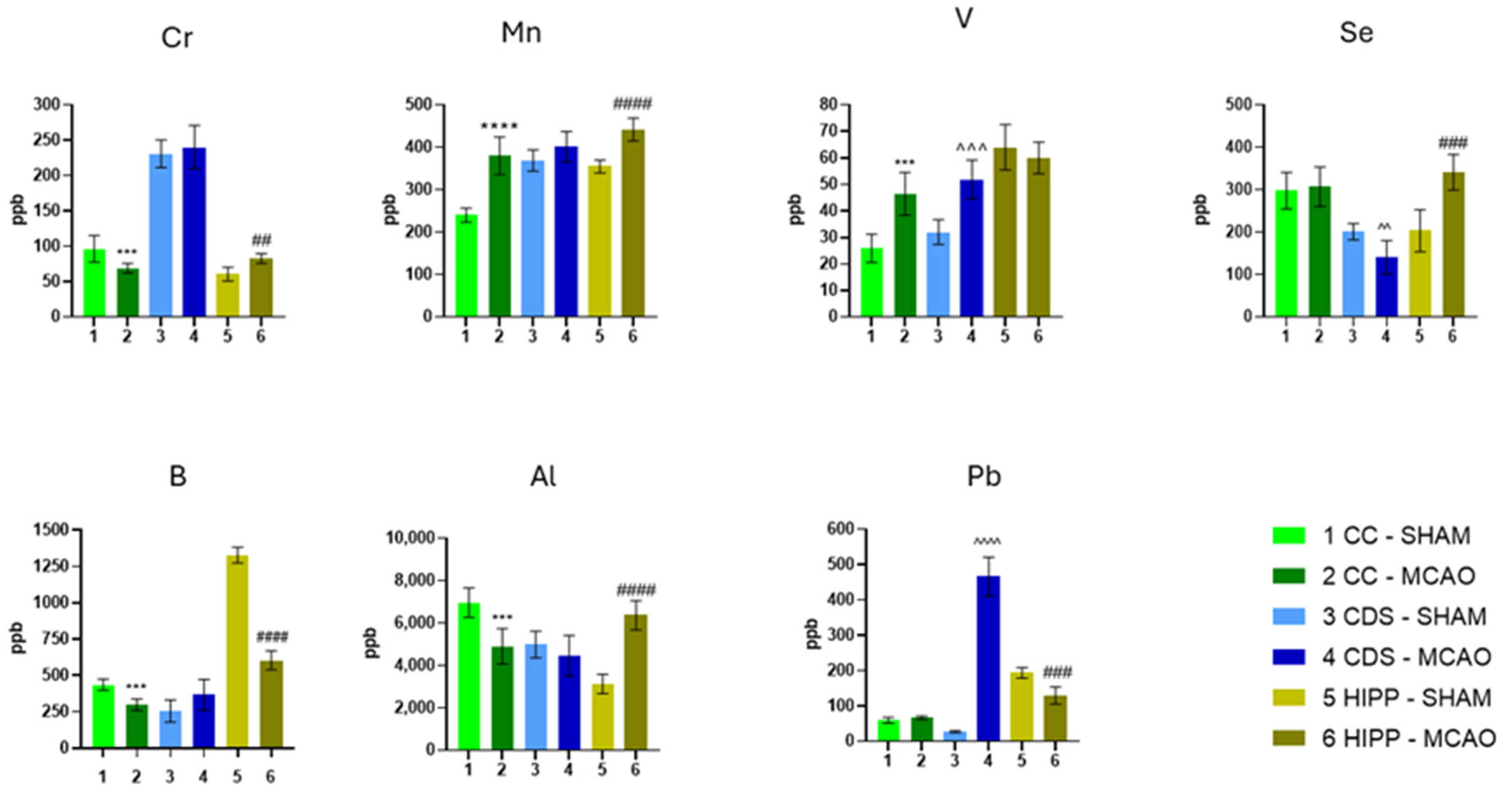

2.1. The Concentration of Elements

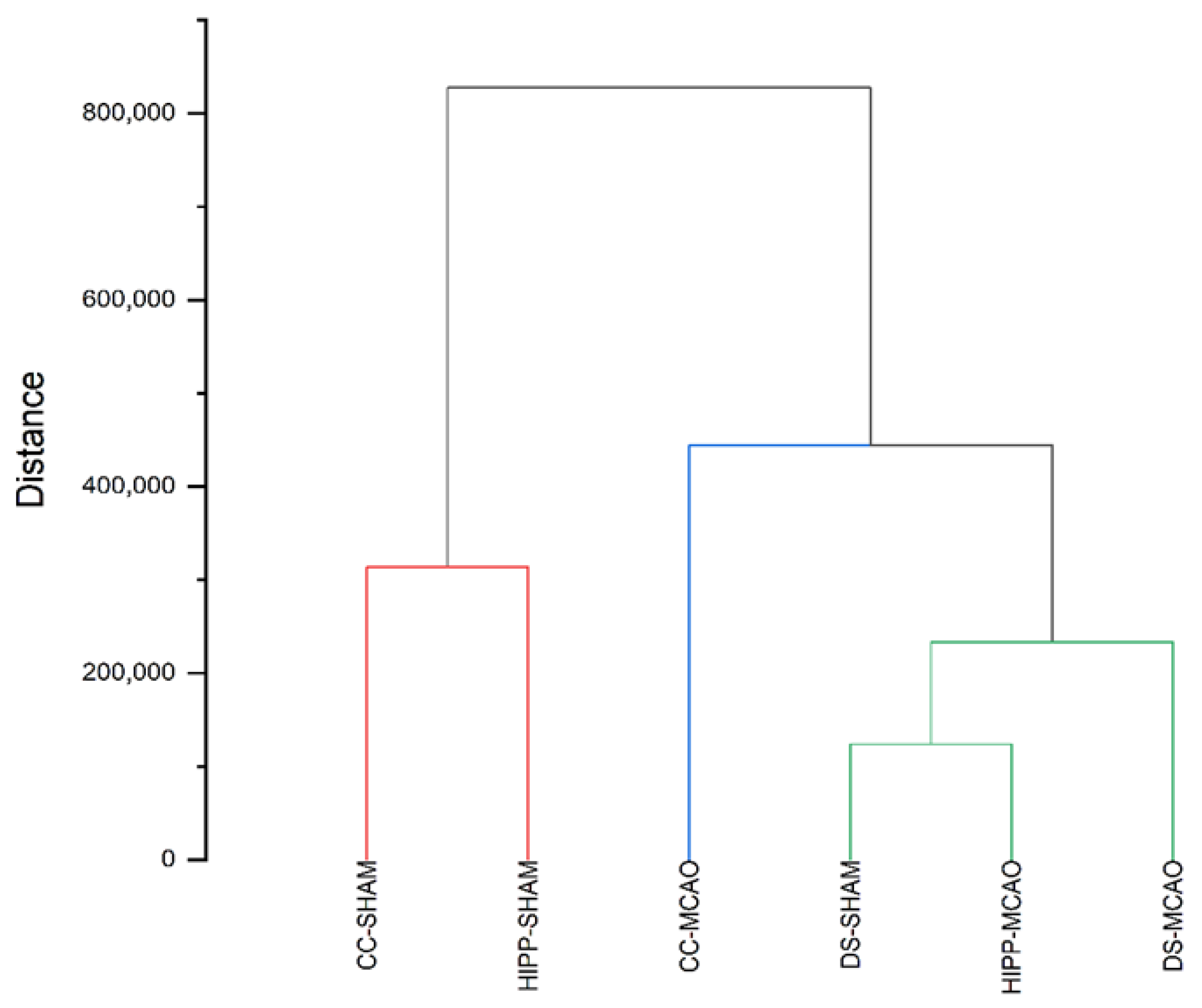

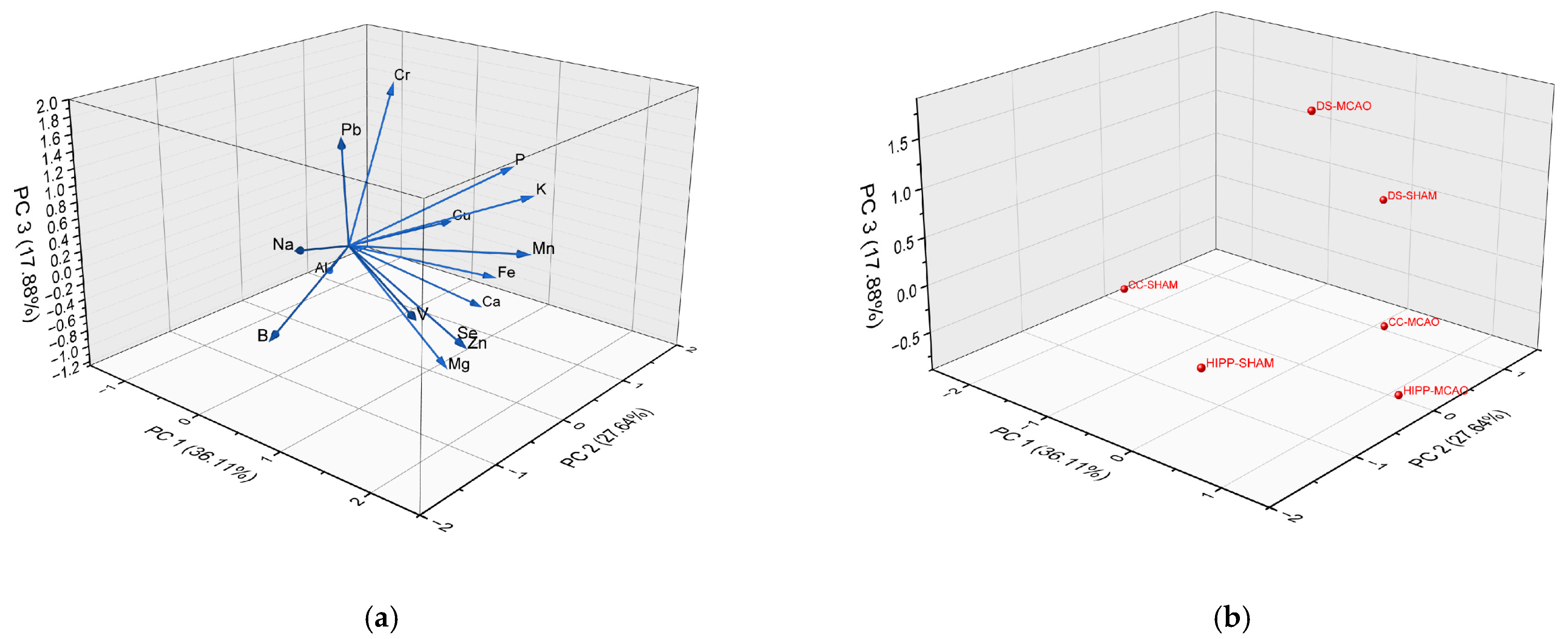

2.2. Chemometric Analysis: Cluster Analysis (CA) and Principal Component Analysis (PCA)

3. Discussion

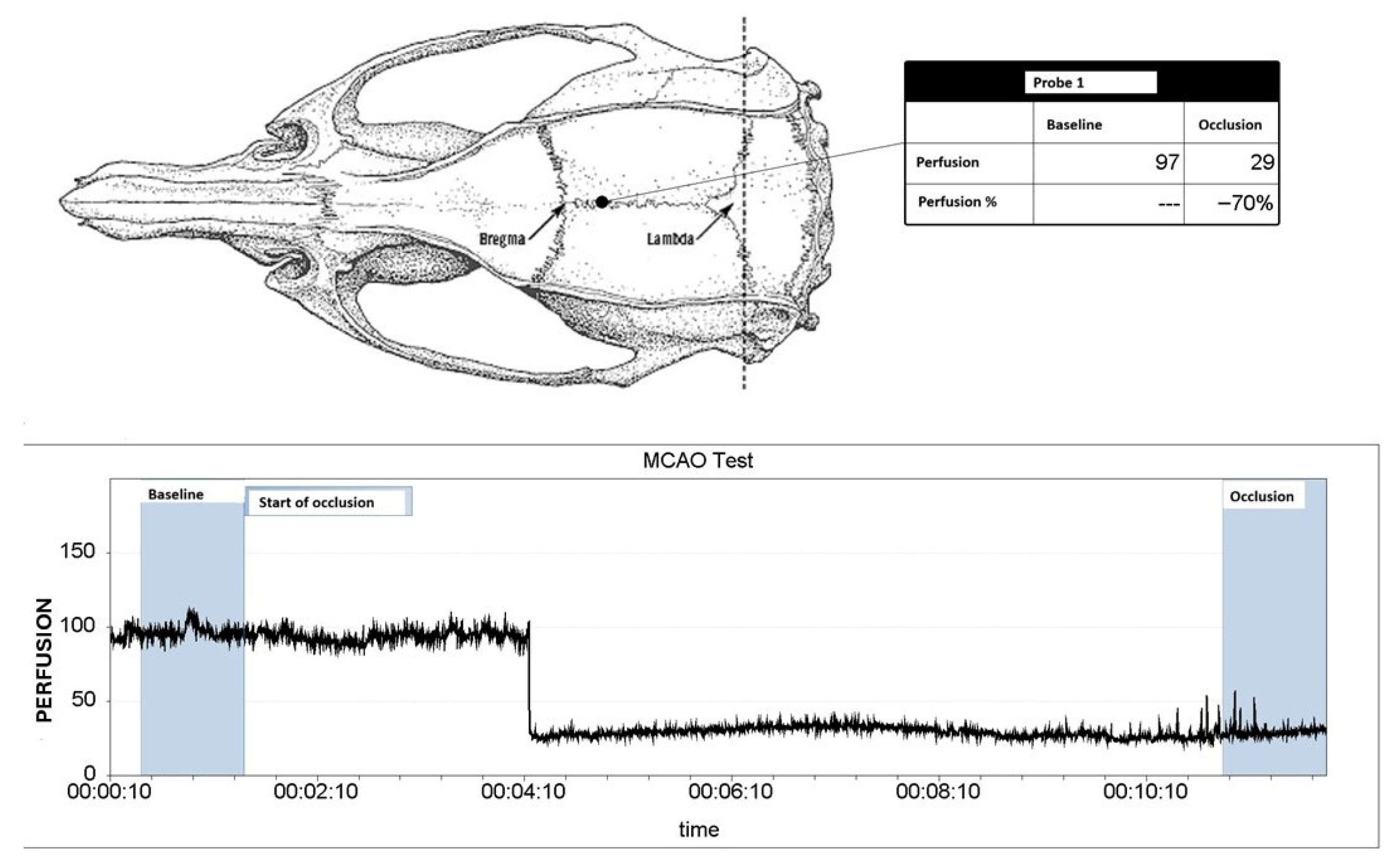

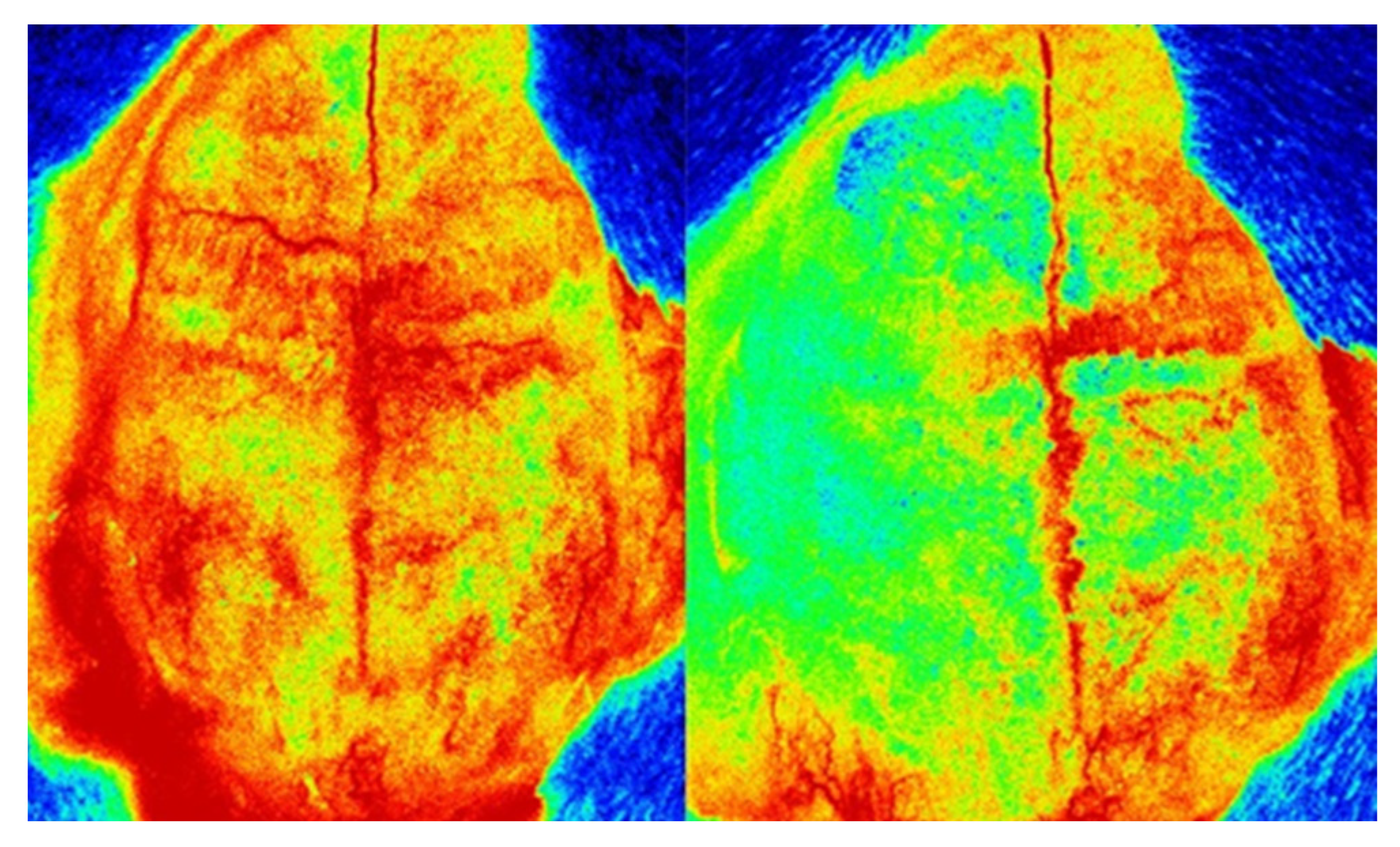

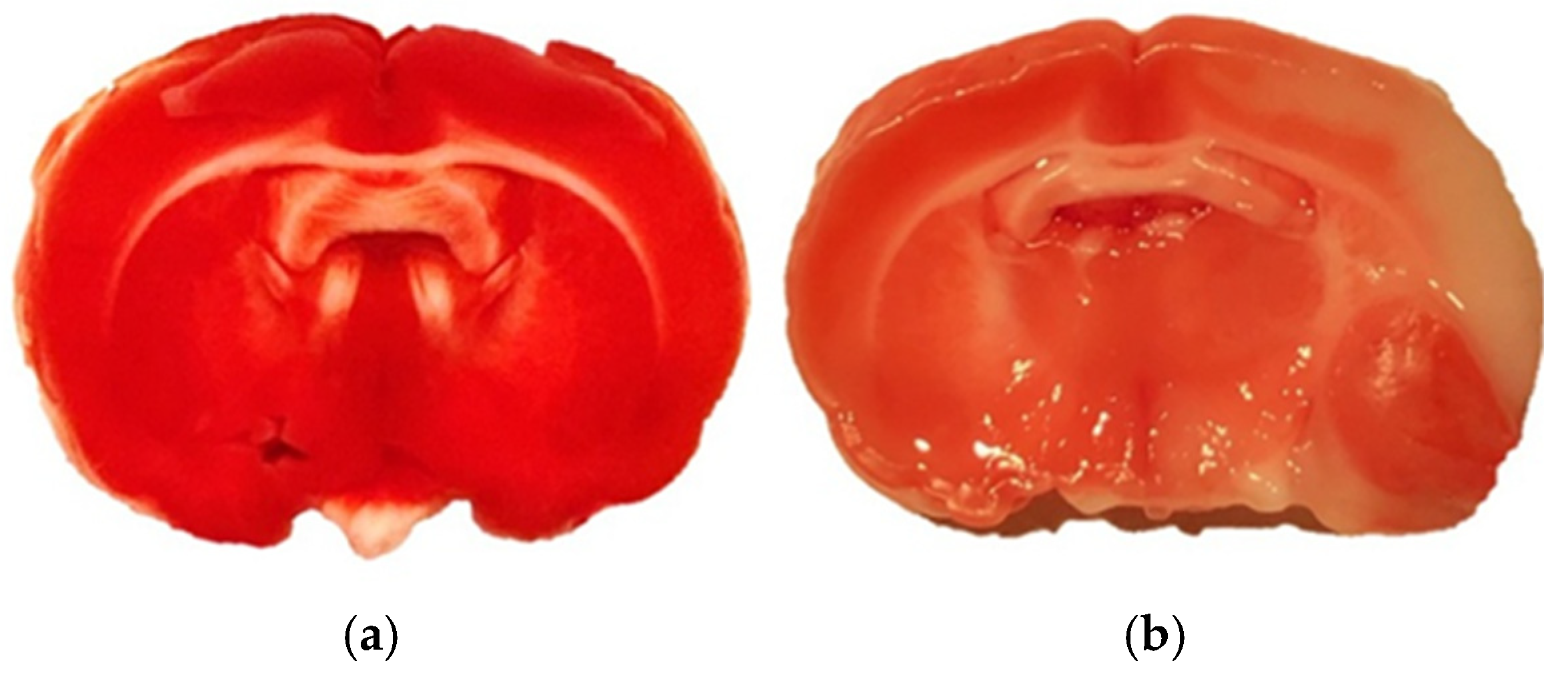

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Reagents

4.2. Animals

4.3. Sample Preparation

4.4. Instrumentation

4.5. Data Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ATP | Adenosine 5′-triphosphate |

| BBB | Blood–brain barrier |

| CA | Cluster analysis |

| CC | Frontal cortex |

| CDS | Dorsal striatum |

| DALYs | Disability-adjusted life-years |

| HIPP | Hippocampus |

| ICP-MS | Inductively coupled plasma-mass spectrometry |

| LOD | Limit of detection |

| LOQ | Limit of quantification |

| MCAO | Middle cerebral artery occlusion |

| nNOS | Neuronal nitric oxide synthase |

| PCA | Principal component analysis |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| SD | Standard deviation |

References

- Feigin, V.L.; Brainin, M.; Norrving, B.; Martins, S.O.; Pandian, J.; Lindsay, P.; Grupper, M.F.; Rautalin, I. World Stroke Organization: Global Stroke Fact Sheet 2025. Int. J. Stroke 2025, 20, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herpich, F.; Rincon, F. Management of Acute Ischemic Stroke. Crit. Care Med. 2020, 48, 1654–1663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soto, A.; Guillén-Grima, F.; Morales, G.; Muñoz, S.; Aguinaga-Ontoso, I.; Fuentes-Aspe, R. Prevalence and Incidence of Ictus in Europe: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. An. Sist. Sanit. Navar. 2022, 45, e0979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheng, H.; Dang, L.; Li, X.; Yang, Z.; Yang, W. A Modified Transcranial Middle Cerebral Artery Occlusion Model to Study Stroke Outcomes in Aged Mice. J. Vis. Exp. 2023, 195, e65345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayan, S.K.; Cherian, S.G.; Phaniti, P.B.; Chidambaram, S.B.; Vasanthi, A.H.R.; Arumugam, M. Preclinical Animal Studies in Ischemic Stroke: Challenges and Some Solutions. Anim. Model. Exp. Med. 2021, 4, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacRae, I. Preclinical Stroke Research—Advantages and Disadvantages of the Most Common Rodent Models of Focal Ischaemia. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2011, 164, 1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, L.; Hu, S.; Zeng, L.; Chen, R.; Li, H.; Yu, J.; Yang, H. Animal Models of Ischemic Stroke with Different Forms of Middle Cerebral Artery Occlusion. Brain Sci. 2023, 13, 1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Xun, P.; Tsinovoi, C.; McClure, L.A.; Brockman, J.; MacDonald, L.; Cushman, M.; Cai, J.; Kamendulis, L.; Mackey, J. Urinary Cadmium Concentration and the Risk of Ischemic Stroke. Neurology 2018, 91, e382–e391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulsen, A.H.; Sears, C.G.; Harrington, J.; Howe, C.J.; James, K.A.; Roswall, N.; Overvad, K.; Tjønneland, A.; Wellenius, G.A.; Meliker, J. Urinary Cadmium and Stroke—A Case-Cohort Study in Danish Never-Smokers. Environ. Res. 2021, 200, 111394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, L.; Qiu, R.; Tang, Y.; Wang, S. Cadmium-Zinc Exchange and Their Binary Relationship in the Structure of Zn-Related Proteins: A Mini Review. Metallomics 2014, 6, 1313–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Li, W.; Wang, Y.; Wang, T.; Ma, M.; Tian, C. Association Between the Change of Serum Copper and Ischemic Stroke: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Mol. Neurosci. 2020, 70, 475–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, G.; Huang, Y.; Xie, G.; Tang, J. Exploring Copper’s Role in Stroke: Progress and Treatment Approaches. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1409317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kahlson, M.A.; Dixon, S.J. Copper-Induced Cell Death. Science 2022, 375, 1231–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Q.; Ma, M.; Yu, H.; Han, Y.; Zhang, D. Dexmedetomidine Enables Copper Homeostasis in Cerebral Ischemia/Reperfusion via Ferredoxin 1. Ann. Med. 2023, 55, 2209735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rospond, B.; Krakowska, A.; Piotrowska, J.; Pomierny, B.; Krzyżanowska, W.; Szewczyk, B.; Szafrański, P.; Dorożynski, P.; Paczosa-Bator, B. Multidimensional Analysis of Selected Bioelements in Rat’s Brain Subjected to Stroke Procedure and Treatment with H2S Donor AP-39. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. 2025, 88, 127628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegele, R.; Howell, N.R.; Callaghan, P.D.; Pastuovic, Z. Investigation of Elemental Changes in Brain Tissues Following Excitotoxic Injury. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. B 2013, 306, 125–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pushie, M.J.; Sylvain, N.J.; Hou, H.; Pendleton, N.; Wang, R.; Zimmermann, L.; Pally, M.; Cayabyab, F.S.; Peeling, L.; Kelly, M.E. X-Ray Fluorescence Mapping of Brain Tissue Reveals the Profound Extent of Trace Element Dysregulation in Stroke Pathophysiology. Metallomics 2024, 16, mfae054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pushie, M.J.; Sylvain, N.J.; Hou, H.; George, D.; Kelly, M.E. Ion Dyshomeostasis in the Early Hyperacute Phase after a Temporary Large-Vessel Occlusion Stroke. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2024, 15, 2132–2143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szydlowska, K.; Tymianski, M. Calcium, Ischemia and Excitotoxicity. Cell Calcium 2010, 47, 122–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sensi, S.L.; Paoletti, P.; Bush, A.I.; Sekler, I. Zinc in the Physiology and Pathology of the CNS. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2009, 10, 780–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuo, Q.Z.; Lei, P.; Jackman, K.A.; Li, X.L.; Xiong, H.; Li, X.L.; Liuyang, Z.Y.; Roisman, L.; Zhang, S.T.; Ayton, S.; et al. Tau-Mediated Iron Export Prevents Ferroptotic Damage after Ischemic Stroke. Mol. Psychiatry 2017, 22, 1520–1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dixon, S.J.; Stockwell, B.R. The Role of Iron and Reactive Oxygen Species in Cell Death. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2014, 10, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flora, G.; Gupta, D.; Tiwari, A. Toxicity of Lead: A Review with Recent Updates. Interdiscip. Toxicol. 2012, 5, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shayganfard, M. Are Essential Trace Elements Effective in Modulation of Mental Disorders? Update and Perspectives. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2022, 200, 1032–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawahara, M.; Kato-Negishi, M. Link between Aluminum and the Pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s Disease: The Integration of the Aluminum and Amyloid Cascade Hypotheses. Int. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2011, 2011, 276393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guilarte, T.R. Manganese and Parkinson’s Disease: A Critical Review and New Findings. Environ. Health Perspect. 2010, 118, 1071–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigual, R.; Fuentes, B.; Díez-Tejedor, E. Management of Acute Ischemic Stroke. Med. Clin. 2023, 161, 485–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candelario-Jalil, E. Injury and Repair Mechanisms in Ischemic Stroke: Considerations for the Development of Novel Neurotherapeutics. Curr. Opin. Investig. Drugs 2009, 10, 644–654. [Google Scholar]

- Przykaza, Ł. Understanding the Connection Between Common Stroke Comorbidities, Their Associated Inflammation, and the Course of the Cerebral Ischemia/Reperfusion Cascade. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 782569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, S.L.; Manhas, N.; Raghubir, R. Molecular Targets in Cerebral Ischemia for Developing Novel Therapeutics. Brain Res. Rev. 2007, 54, 34–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahimpour, S.; Meadows, E.; Hollander, J.M.; Karelina, K.; Brown, C.M. Assessment of Phase-Dependent Alterations in Cortical Glycolytic and Mitochondrial Metabolism Following Ischemic Stroke. ASN Neuro 2025, 17, 2488935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giffard, R.G.; Swanson, R.A. Ischemia-Induced Programmed Cell Death in Astrocytes. Glia 2005, 50, 299–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, A.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, J.; Huang, Z. Ischemic Stroke and Intervention Strategies Based on the Timeline of Stroke Progression: Review and Prospects. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2025, 15, 4543–4581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martynov, M.Y.; Zhuravleva, M.V.; Vasyukova, N.S.; Kuznetsova, E.V.; Kameneva, T.R. Oxidative Stress in the Pathogenesis of Stroke and Its Correction. Zhurnal Nevrologii i Psihiatrii imeni S.S. Korsakova 2023, 123, 16–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parvez, S.; Kaushik, M.; Ali, M.; Alam, M.M.; Ali, J.; Tabassum, H.; Kaushik, P. Dodging Blood Brain Barrier with “Nano” Warriors: Novel Strategy against Ischemic Stroke. Theranostics 2022, 12, 689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, R.; Xu, M.; Wang, Y.; Xie, F.; Zhang, G.; Qin, X. Nrf2-a Promising Therapeutic Target for Defensing Against Oxidative Stress in Stroke. Mol. Neurobiol. 2017, 54, 6006–6017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Z.J.; Lin, X.; Yang, L.; Li, Y.; Gao, W. Activation of Inflammasomes and Relevant Modulators for the Treatment of Microglia-Mediated Neuroinflammation in Ischemic Stroke. Mol. Neurobiol. 2024, 61, 10792–10804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Bonilla, L.; Shahanoor, Z.; Sciortino, R.; Nazarzoda, O.; Racchumi, G.; Iadecola, C.; Anrather, J. Analysis of Brain and Blood Single-Cell Transcriptomics in Acute and Subacute Phases after Experimental Stroke. Nat. Immunol. 2024, 25, 357–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, R.Z.; Achón Buil, B.; Rentsch, N.H.; Bosworth, A.; Zhang, M.; Kisler, K.; Tackenberg, C.; Rust, R. A Molecular Brain Atlas Reveals Cellular Shifts during the Repair Phase of Stroke. J. Neuroinflammation 2025, 22, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enzmann, G.; Kargaran, S.; Engelhardt, B. Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury in Stroke: Impact of the Brain Barriers and Brain Immune Privilege on Neutrophil Function. Ther. Adv. Neurol. Disord. 2018, 11, 1756286418794184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nesto, R.W.; Kowalchuk, G.J. The Ischemic Cascade: Temporal Sequence of Hemodynamic, Electrocardiographic and Symptomatic Expressions of Ischemia. Am. J. Cardiol. 1987, 59, C23–C30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Tuo, Q.; Lei, P. Iron, Ferroptosis, and Ischemic Stroke. J. Neurochem. 2023, 165, 487–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, S.J.; Pratt, D.A. Ferroptosis: A Flexible Constellation of Related Biochemical Mechanisms. Mol. Cell 2023, 83, 1030–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pifferi, F.; Laurent, B.; Plourde, M. Lipid Transport and Metabolism at the Blood-Brain Interface: Implications in Health and Disease. Front. Physiol. 2021, 12, 645646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, Z.; Zhou, X.; Dong, W.; Timmins, G.S.; Pan, R.; Shi, W.; Yuan, S.; Zhao, Y.; Ji, X.; Liu, K.J. Neuronal Zinc Transporter ZnT3 Modulates Cerebral Ischemia-Induced Blood-Brain Barrier Disruption. Aging Dis. 2023, 15, 2727–2741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, M.; Zhu, L.; Chen, Y.; Jin, Y.; Fang, Z.; Yao, Y. Serum/Plasma Zinc Is Apparently Increased in Ischemic Stroke: A Meta-Analysis. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2022, 200, 615–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, R.; Wang, L.; Sun, L.; Dong, J. Neuroprotective Effect of Magnesium Supplementation on Cerebral Ischemic Diseases. Life Sci. 2021, 272, 119257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.Y.; Chung, S.Y.; Lin, M.C.; Cheng, F.C. Effects of Magnesium Sulfate on Energy Metabolites and Glutamate in the Cortex during Focal Cerebral Ischemia and Reperfusion in the Gerbil Monitored by a Dual-Probe Microdialysis Technique. Life Sci. 2002, 71, 803–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westermaier, T.; Zausinger, S.; Baethmann, A.; Schmid-Elsaesser, R. Dose Finding Study of Intravenous Magnesium Sulphate in Transient Focal Cerebral Ischemia in Rats. Acta Neurochir. 2005, 147, 525–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, S.; Jang, M.; Kim-Tenser, M.; Shkirkova, K.; Liebeskind, D.S.; Starkman, S.; Villablanca, J.P.; Hamilton, S.; Naidech, A.; Saver, J.L.; et al. Effect of Magnesium on Deterioration and Symptomatic Hemorrhagic Transformation in Cerebral Ischemia: An Ancillary Analysis of the FAST-MAG Trial. Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2023, 52, 539–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.; Wang, W.; Xia, Y.; Li, Y.; Jia, J.; Xiao, G. Regulators of Phagocytosis as Pharmacologic Targets for Stroke Treatment. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1122527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adibhatla, R.M.; Hatcher, J.F. Phospholipase A2, Reactive Oxygen Species, and Lipid Peroxidation in Cerebral Ischemia. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2006, 40, 376–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, J.M.; Zhu, X.H.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, W. Dynamic Correlations between Hemodynamic, Metabolic, and Neuronal Responses to Acute Whole-Brain Ischemia. NMR Biomed. 2015, 28, 1357–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, M.A.; Ahmad, A.S.; Ahmad, M.; Salim, S.; Yousuf, S.; Ishrat, T.; Islam, F. Selenium Protects Cerebral Ischemia in Rat Brain Mitochondria. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2004, 101, 73–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Özbal, S.; Erbil, G.; Koçdor, H.; Tuǧyan, K.; Pekçetin, Ç.; Özoǧul, C. The Effects of Selenium against Cerebral Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury in Rats. Neurosci. Lett. 2008, 438, 265–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, L.; Ma, Y.M.; Shen, X.L.; Fan, Y.C.; Zhang, J.Z.; Li, P.A.; Jing, L. The Involvement of Mitochondrial Biogenesis in Selenium Reduced Hyperglycemia-Aggravated Cerebral Ischemia Injury. Neurochem. Res. 2020, 45, 1888–1901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuo, Q.Z.; Masaldan, S.; Southon, A.; Mawal, C.; Ayton, S.; Bush, A.I.; Lei, P.; Belaidi, A.A. Characterization of Selenium Compounds for Anti-Ferroptotic Activity in Neuronal Cells and After Cerebral Ischemia–Reperfusion Injury. Neurotherapeutics 2021, 18, 2682–2691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.X.; Zhou, X.Y.; Li, C.S.; Liu, L.Q.; Huang, S.Y.; Zhou, S.N. Selenoprotein S Expression in the Rat Brain Following Focal Cerebral Ischemia. Neurol. Sci. 2013, 34, 1671–1678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fradejas, N.; Del Carmen Serrano-Pérez, M.; Tranque, P.; Calvo, S. Selenoprotein S Expression in Reactive Astrocytes Following Brain Injury. Glia 2011, 59, 959–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuo, Z.; Wang, H.; Zhang, S.; Bartlett, P.F.; Walker, T.L.; Hou, S.T. Selenium Supplementation Provides Potent Neuroprotection Following Cerebral Ischemia in Mice. J. Cereb. Blood Flow. Metab. 2023, 43, 1060–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turovsky, E.A.; Mal’tseva, V.N.; Sarimov, R.M.; Simakin, A.V.; Gudkov, S.V.; Plotnikov, E.Y. Features of the Cytoprotective Effect of Selenium Nanoparticles on Primary Cortical Neurons and Astrocytes during Oxygen–Glucose Deprivation and Reoxygenation. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 1710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gönüllü, H.; Karadaş, S.; Milanlioğlu, A.; Gönüllü, E.; Katı, C.; Demir, H. Levels of serum trace elements in ischemic stroke patients. J. Exp. Clin. Med. 2014, 30, 301–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamebozorgi, K.; Kooshki, A.; Saljoughi, M.; Sanjari, M.; Ahmadi, Z.; Mosavi Mirzaei, S.M. Cerebrovascular Accidents Association between Serum Trace Elements and Toxic Metals Level, a Case-Control Study. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0317731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira-Paula, G.H.; Martins, A.C.; Ferrer, B.; Tinkov, A.A.; Skalny, A.V.; Aschner, M. The Impact of Manganese on Vascular Endothelium. Toxicol. Res. 2024, 40, 501–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, Y.; Huang, S.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zhou, L.; Li, D.; Xie, C.; Lv, Z.; Guo, Y.; Ke, Y.; et al. Associations of Multiple Plasma Metals with the Risk of Ischemic Stroke: A Case-Control Study. Environ. Int. 2019, 125, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirończuk, A.; Kapica-Topczewska, K.; Socha, K.; Soroczyńska, J.; Jamiołkowski, J.; Chorąży, M.; Czarnowska, A.; Mitrosz, A.; Kułakowska, A.; Kochanowicz, J. Disturbed Ratios between Essential and Toxic Trace Elements as Potential Biomarkers of Acute Ischemic Stroke. Nutrients 2023, 15, 1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Chen, X.; Cheng, H.; Zhang, L. Dietary Copper Intake and Risk of Stroke in Adults: A Case-Control Study Based on National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2013–2018. Nutrients 2022, 14, 409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, Q.J.; Zhao, K.; Guo, Y.; Wu, X.T.; Yang, J.C.; Yang, M.F. Environmental Toxic Metal Contaminants and Risk of Stroke: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2022, 29, 32545–32565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, L.; Lu, J.; Wen, X.; Song, Z.; Sun, C.; Zhao, Y.; Huang, F.; Chen, S.; Jiang, D.; Che, W.; et al. Cuproptosis: Mechanisms and Nanotherapeutic Strategies in Cancer and Beyond. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2025, 54, 6282–6334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Cai, Q.; Liang, R.; Zhang, D.; Liu, X.; Zhang, M.; Xiong, Y.; Xu, M.; Liu, Q.; Li, P.; et al. Copper Homeostasis and Copper-Induced Cell Death in the Pathogenesis of Cardiovascular Disease and Therapeutic Strategies. Cell Death Dis. 2023, 14, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Song, M.; Ren, J.; Liang, L.; Mao, G.; Chen, M. Copper Homeostasis and Cuproptosis in Central Nervous System Diseases. Cell Death Dis. 2024, 15, 850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Liu, X.; Wu, Y.; Qi, X.; Ling, Q.; Wu, Z.; Shi, Y.; Hu, H.; Yu, P.; Ma, J.; et al. Association between Serum Copper Levels and Stroke in the General Population: A Nationally Representative Study. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2024, 33, 107473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storves, K.P.; Talcott, M.R.; Wallace, J.M.; Bennett, B.T.; Makaron, L.M.; Clemons, D.; Hugh (Chip) Price, V.; Cohen, J.K.; Hasenau, J.J.; Freed, C.K.; et al. The Veterinary Consortium for Research Animal Care and Welfare Survey on Revisions to the Eighth Edition of the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. J. Am. Assoc. Lab. Anim. Sci. 2025, 64, 553–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- du Sert, N.P.; Hurst, V.; Ahluwalia, A.; Alam, S.; Avey, M.T.; Baker, M.; Browne, W.J.; Clark, A.; Cuthill, I.C.; Dirnagl, U.; et al. The ARRIVE Guidelines 2.0: Updated Guidelines for Reporting Animal Research. PLoS Biol. 2020, 18, e3000410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pomierny, B.; Krzyżanowska, W.; Skórkowska, A.; Jurczyk, J.; Budziszewska, B.; Pera, J. Chicago Sky Blue 6B Exerts Neuroprotective and Anti-Inflammatory Effects on Focal Cerebral Ischemia. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2024, 170, 116102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.H.M.; Rakib, F.; Abdelalim, E.M.; Limbeck, A.; Mall, R.; Ullah, E.; Mesaeli, N.; McNaughton, D.; Ahmed, T.; Al-Saad, K. Fourier-Transform Infrared Imaging Spectroscopy and Laser Ablation -ICPMS New Vistas for Biochemical Analyses of Ischemic Stroke in Rat Brain. Front. Neurosci. 2018, 12, 647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Element | PC1 36.11% | PC2 27.64% | PC3 17.88% |

|---|---|---|---|

| B | 0.51 | −1.61 | −0.35 |

| Na | 0.39 | −1.15 | 0.49 |

| Mg | 1.20 | 0.02 | −1.17 |

| K | 1.42 | 1.03 | 0.70 |

| Ca | 0.64 | 1.32 | −1.13 |

| V | 1.60 | −0.95 | 0.02 |

| Cr | −0.11 | 0.80 | 1.81 |

| Fe | 1.10 | 0.92 | −0.41 |

| Cu | 0.12 | 1.46 | −0.16 |

| Zn | 1.80 | −0.49 | −0.44 |

| Se | 1.80 | −0.49 | −0.44 |

| Pb | 0.49 | −0.65 | 1.68 |

| Mn | 1.85 | 0.38 | 0.34 |

| Al | −0.82 | 0.58 | −0.86 |

| P | 1.19 | 1.01 | 1.01 |

| Category | Element | CC | DS. | HIPP | Functional Significance/Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I. Macroelements | Ca | ↑↑ | ↓↓ | ↑ | Consistent with Ca2+-driven excitotoxicity, mitochondrial dysfunction, and protease activation in ischemic injury. |

| Na | ~ | ~ | ↓ | Varied least among all elements; suggests Na imbalance is less dominant in the subacute phase. | |

| K | ↑ | ~ | ↑ | Linked to ionic imbalance and key for ATP-dependent metabolism and cell function. | |

| Mg | ↑ | ~ | ↑↑ | Pivotal for ATP-dependent metabolism; acts as a natural Ca2+ antagonist. | |

| P | ↑ | ~ | ↑ | Pivotal for ATP-dependent metabolism and structural membrane integrity. | |

| II Antioxidants | Fe | ↑↑ | ↓↓ | ~ | Redox-active; Fe accumulation ↑ ROS and lipid peroxidation; linked to ferroptotic pathways in stroke. |

| Cu | ↑↑ | ↓↓ | ~ | Redox-active; accumulation ↑ ROS generation. Opposite trends underscore divergent regional responses (defense vs. destruction). | |

| Zn | ↑ | ~ | ↑ | Synaptic neuromodulator; dysregulation contributes to oxidative/inflammatory injury. | |

| Se | ~ | ↓ | ↑↑ | Supports selenoprotein-mediated antioxidant defenses (GPX). Suggests region-dependent vulnerability/capacity. | |

| III Toxicants | Pb | ~ | ↑↑ | ↓ | Well-established neurotoxicant associated with oxidative stress and synaptic dysfunction. |

| V | ↑↑ | ↑↑ | ~ | Trace metal showing opposite trends between cortex and striatum. | |

| IV. Trace & Neurotoxic | Mn | ↑↑ | ~ | ↑ | Documented neurotoxic potential at high levels via oxidative/inflammatory pathways. |

| Al. | ↓ | ~ | ↑↑ | Documented neurotoxic potential via mitochondrial and oxidative impairments. | |

| Cr | ↓ | ~ | ↑ | Trace metal showing regional differences. | |

| B | ↓ | ~ | ↓↓ | Trace metal showing regional differences. |

| Step | Time (Min) | Power (W) | Internal Temperature (°C) | External Temperature (°C) | Pressure (Bar) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 10:00 | 800 | 110 | 60 | 80 |

| 2 | 10:00 | 1000 | 180 | 60 | 80 |

| 3 | 10:00 | 1500 | 240 | 60 | 120 |

| 4 | 10:00 | 1500 | 240 | 60 | 120 |

| ICP-MS Parameter | Operating Mode |

|---|---|

| RF power (W) | 1550 |

| Sample depth (mm) | 10.0 |

| Nebulizer gas flow (L/min) | 0.99 |

| Plasma gas flow (L/min) | 15 |

| Auxiliary gas flow (L/min) | 0.9 |

| Cell gas flow in He mode (mL/min) | 4.3 mL/min |

| Lens Tune | Autotune |

| Element | R | LOD [ppb] | LOQ [ppb] |

|---|---|---|---|

| 11B | 1.0000 | 0.34 | 1.0 |

| 23Na | 0.9994 | 0.27 | 0.82 |

| 24Mg | 0.9997 | 0.14 | 0.42 |

| 27Al | 0.9997 | 0.039 | 0.12 |

| 31P | 0.9996 | 34 | 101 |

| 39K | 0.9998 | 17 | 50 |

| 44Ca | 0.9980 | 0.62 | 1.9 |

| 51V | 1.0000 | 0.0054 | 0.016 |

| 52Cr | 1.0000 | 0.029 | 0.087 |

| 55Mn | 1.0000 | 0.012 | 0.037 |

| 56Fe | 1.0000 | 0.42 | 1.3 |

| 63Cu | 1.0000 | 0.037 | 0.11 |

| 66Zn | 0.9999 | 0.21 | 0.63 |

| 78Se | 1.0000 | 0.17 | 0.52 |

| Pb * | 1.0000 | 0.010 | 0.030 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rospond, B.; Matusiak, A.; Stolarczyk, E.U.; Piotrowska, J.; Pomierny, B.; Krzyżanowska, W.; Szafrański, P.W.; Dorożyński, P. Metallomic Aspects of Stroke and Recovery: ICP-MS Study with Chemometric Analysis. Molecules 2025, 30, 4672. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244672

Rospond B, Matusiak A, Stolarczyk EU, Piotrowska J, Pomierny B, Krzyżanowska W, Szafrański PW, Dorożyński P. Metallomic Aspects of Stroke and Recovery: ICP-MS Study with Chemometric Analysis. Molecules. 2025; 30(24):4672. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244672

Chicago/Turabian StyleRospond, Bartłomiej, Aleksander Matusiak, Elżbieta U. Stolarczyk, Joanna Piotrowska, Bartosz Pomierny, Weronika Krzyżanowska, Przemysław W. Szafrański, and Przemysław Dorożyński. 2025. "Metallomic Aspects of Stroke and Recovery: ICP-MS Study with Chemometric Analysis" Molecules 30, no. 24: 4672. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244672

APA StyleRospond, B., Matusiak, A., Stolarczyk, E. U., Piotrowska, J., Pomierny, B., Krzyżanowska, W., Szafrański, P. W., & Dorożyński, P. (2025). Metallomic Aspects of Stroke and Recovery: ICP-MS Study with Chemometric Analysis. Molecules, 30(24), 4672. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244672