1. Introduction

Fungal infections have emerged as a significant public health concern, particularly in immunocompromised individuals. Opportunistic fungal pathogens such as

Candida,

Aspergillus, and

Cryptococcus are responsible for a substantial number of infections worldwide.

Candida species are among the most prevalent causes of invasive fungal infections, with

Candida parapsilosis (

C.

parapsilosis) and

Candida albicans (

C.

albicans) being particularly problematic in hospital settings [

1]. Epidemiological data indicate that invasive candidiasis accounts for approximately 1.57 million cases annually, with mortality rates reaching 63.6% [

2]. Furthermore, it has been estimated that invasive fungal infections cause more than 3.8 million deaths annually, with a significant proportion of these deaths resulting from undiagnosed and untreated cases [

2]. The growing prevalence of fungal infections is attributed to several factors, including climate change, increased use of immunosuppressive therapies, and an increasing population of immunocompromised individuals [

3]. Additionally, changes in the epidemiology, diversity in clinical presentation, and emergence of new pathogens further complicate the management and understanding of fungal diseases [

4]. These infections can affect various organ systems, leading to conditions such as bloodstream infections (candidemia), respiratory infections (aspergillosis), and central nervous system infections (cryptococcal meningitis). Recent studies suggest that fungal diseases cause more deaths annually than malaria or breast cancer, highlighting the urgent need for improved diagnostics and treatment strategies [

5].

The genus

Candida belongs to the Ascomycota phylum, within the Saccharomycotina subphylum, and is classified under the Saccharomycetales order [

6]. Phylogenetic studies have shown that

Candida species are polyphyletic and have evolved independently to occupy similar ecological niches as opportunistic pathogens. This evolutionary adaptability contributes not only to their ability to colonize diverse host environments, but also to the development of drug resistance traits [

7]. To effectively cause mucosal and/or systemic disease and withstand the subsequent antifungal host response and antifungal drug treatment,

Candida employs several virulence factors, including temperature adaptation, adhesion and invasion, nutrient acquisition, immune evasion, and drug tolerance [

8].

Infections caused by

Candida species are typically treated with four main classes of antifungal drugs: polyenes, azoles, echinocandins, and pyrimidine analogs. One of the most commonly used drugs is Amphotericin B (

AmpB), a member of the polyene class, which is considered a first-line treatment for severe fungal infections because of its broad-spectrum fungicidal activity. The choice of treatment depends on factors such as species-specific susceptibility and patient health status. Despite the availability of these antifungal agents, increasing resistance to these treatments has been documented, particularly in

C.

parapsilosis, which has shown a marked decrease in susceptibility to polyenes, azoles, and echinocandin-based drugs [

5,

9,

10].

Antifungal resistance has become a major challenge in clinical treatment, limiting the effectiveness of currently available drugs. Resistance develops when fungal pathogens adapt and survive exposure to antifungal agents, reducing drug efficacy and complicating treatment. Several mechanisms contribute to antifungal resistance, including genetic mutations that alter drug targets, increased expression of efflux pumps that remove antifungal agents from fungal cells, and the formation of biofilms that act as protective barriers against treatment [

5,

11,

12].

The overuse of antifungal drugs, particularly in preventive treatments, has accelerated the development of resistance by selectively promoting the survival of resistant strains [

11]. A particularly concerning development is the rise of multidrug-resistant (MDR) fungal species, such as

C. auris, which exhibit resistance to multiple drug classes, including azoles, echinocandins, and polyenes [

5]. These resistant pathogens are more difficult to eliminate, leading to higher mortality rates and prolonged infections in patients.

AmpB is a polyene antifungal agent that has been widely used for the treatment of invasive fungal infections. It binds to ergosterol, a major component of fungal cell membranes, leading to increased membrane permeability and cell death [

13].

AmpB is especially valuable in treating infections caused by fungi that are resistant to other antifungal drugs [

14]. Despite its effectiveness,

AmpB is associated with several adverse effects that limit its clinical use. The most notable among these factors is nephrotoxicity, which can result in significant kidney impairment. Other side effects include infusion-related reactions such as fever and chills, as well as disturbances in serum electrolytes [

15].

Photodynamic therapy (PDT) is a non-invasive approach that has garnered increasing interest in circumventing conventional drug resistance and is a viable option for addressing pathogen infections, especially those resistant to traditional medicines. PDT employs a photosensitizer (PS), which, upon activation by light, generates highly toxic, oxygen-based (ROS) and non-oxygen-based reactive species (RSs), such as singlet oxygen, superoxide, hydrogen peroxide, and free radicals [

16]. These RSs induce oxidative damage critical to cellular components, leading to microbial cell death [

16,

17]. Importantly, the non-specific oxidative mechanism of PDT minimizes the risk of resistance development, making it an attractive modality for treating persistent and resistant infections [

18].

To date, a number of PSs of different dye classes have been introduced and evaluated. The majority of these dyes, such as cyanines (e.g., Indocyanine green, ICG), phenothiazinium dyes (e.g., Methylene blue and Toluidine blue), and BODIPY derivatives, are cationic fluorophores.

Iodinated heptamethine cyanine dyes are relatively new but well-characterized photosensitizers. The incorporation of iodine atoms in conventional (non-iodinated) cyanines enhances intersystem crossing via the heavy-atom effect, thereby increasing the efficiency of ROS generation upon photoactivation. These dyes exhibit, therefore, high quantum yields of singlet oxygen and the generation of other reactive species [

19,

20,

21] but are also characterized by strong absorption in the near-infrared (NIR) optical window, which is advantageous for in vivo applications, as light penetration through the body is maximized and light absorption and scattering are minimized, causing less damage to the skin [

22] and improving safety for therapeutic use [

23]. Our recent studies highlighted the phototoxic potential of iodinated cyanines against bacterial pathogens [

21,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28] and cancer cells [

29]. However, the antifungal activity of these dyes, particularly against highly drug-resistant

Candida strains remains unexplored.

Methylene blue (

MB), categorized as a phenothiazine dye, is another example of a well-known and thoroughly investigated PS with less pronounced but still satisfactory absorption in the deep-red region and high singlet oxygen production [

30,

31]. The high efficacy of

MB in eradicating pathogenic bacteria [

32], fungi such as

C.

albicans [

33,

34,

35,

36],

C.

parapsilosis [

35],

C.

glabrata [

35], and cancer cells [

37,

38] has been repeatedly reported in the literature. We anticipated that, similar to cyanines and some other dye classes, the introduction of iodine atoms in

MB can improve its ROS generation and photocytotoxicity. However, such iodinated Methylene blue derivatives have never been synthesized and investigated.

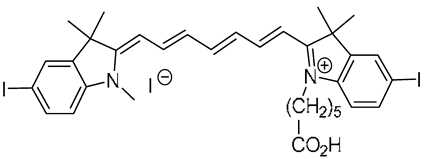

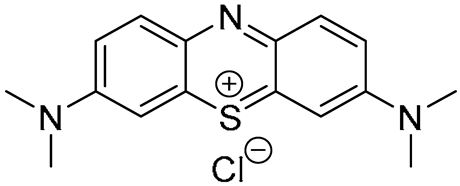

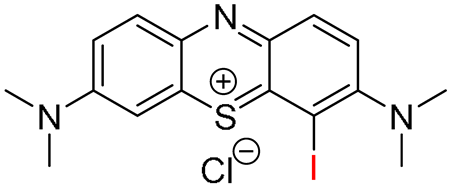

In the present study, for the first time, we developed a simple one-step synthetic approach and synthesized two iodinated MB derivatives—monoiodo (IMB) and diiodo-(2IMB) Methylene blue dyes. The photodynamic efficacy of these dyes and iodinated heptamethine cyanines was investigated against clinically relevant C. albicans and antifungal drug-resistant C. parapsilosis.

2. Results

2.1. Synthesis of Photosensitizers

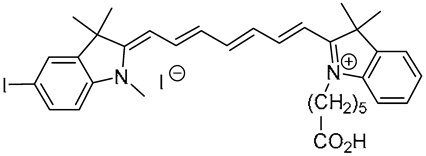

The heptamethine cyanine dyes

Cy7CO2H,

ICy7CO2H,

ICy7CONHPr,

ICy7SO3H, and

2ICy7CO2H were synthesized according to previously reported procedures [

21,

28] with reasonable yields (17–56%) via a one-pot sequential reaction of

N-[5-(phenylamino)-2,4-pentadienylidene]aniline with the first indolenine molecule

1a or

1b in acetic anhydride to form a corresponding

N-phenylacetamide derivative

2a or

2b, which was then reacted with the second indolenine

3a–

3d in the presence of pyridine (

Scheme 1).

The iodinated

MB dyes

IMB and

2IMB were synthesized in reasonable yields (67% for

IMB and 43% for

2IMB) via direct iodination of

MB with

N-iodosuccinimide (NIS) in the presence of

p-toluene sulfonic acid (pTSA) at room temperature (

Scheme 2). The preferable yield of the mono- or di-iodinated products was achieved by varying the ratio between

MB and the iodination agent.

2.2. Spectral Properties

The absorption and emission spectra of the newly synthesized

MB derivatives are presented in

Figure 1. The absorption (λ

maxAb) and fluorescence (λ

maxFl) maxima, extinction coefficients (ε), absolute fluorescence quantum yields (Φ

F), relative quantum yields of ROS generation (φ

ROS) (determined using the H

2DCFDA-based method), and absolute quantum yields of singlet oxygen generation (Φ

Δ), measured via DPBF for the investigated cyanine and

MB derivatives (

cDye~1 μM), are summarized in

Table 1 and

Table 2, respectively. To avoid confusion between relative and absolute quantum yields, Φ

F and Φ

Δ (absolute values) are given as percentages, whereas φ

ROS (relative values) are expressed as a fraction of one.

The cyanine dyes demonstrate longer-wavelength absorption in the fNIR range (740–754 nm) and significantly higher extinction coefficients (109,000–238,000 M−1cm−1) compared to MB derivatives (λmaxAb = 665–685 nm, ε = 24,000–74,200 M−1cm−1) in saline and somewhat higher extinction coefficients in MeOH (ε = 30,000–88,200 M−1cm−1), making them easily excitable within the biological window. Additionally, cyanines emit at longer wavelengths and have increased fluorescence quantum yields in aqueous media (ΦF~4–13%) compared with MB (ΦF = 2%). The brightness of cyanines (B~6800–23,800 M−1cm−1), calculated as B = ε × ΦF, is nearly 4.5–16 times higher than that of MB (B~1500 M−1cm−1), whereas iodinated IMB and 2IMB derivatives exhibit negligible practical fluorescence. Importantly, iodination has only a minor effect on the ε, ΦF, and B values of cyanines. These properties facilitate the application of iodinated cyanines for fluorescence imaging of these PSs in vivo, including tracking their delivery and accumulation in target tissues.

Conversely, iodinated

MB derivatives exhibit extremely low fluorescence in aqueous saline, with Φ

F values of ~0.021% (

IMB) and 0.0015% (

2IMB), along with reduced extinction coefficients, rendering fluorescence monitoring impractical. The decrease in Φ

F and ε upon iodination of

MB likely results from enhanced intersystem crossing (ISC) to the triplet state and aggregation of these dyes in aqueous saline, as evidenced by an increased shoulder on the shorter-wavelength slope of the absorption spectrum (

Figure 1). Nevertheless, these dyes exhibit significant singlet oxygen generation yields (Φ

Δ~20–52% in acetonitrile), comparable in magnitude to those of cyanines (Φ

Δ~4.5–65%) (see

Section 2.4).

2.3. Photostability of Cyanines and Methylene Blue (MB) Derivatives

The photostabilities of cyanines and

MB-based dyes were evaluated in saline under continuous light irradiation, using 730 nm and 632 nm LEDs for cyanines and

MB derivatives, respectively. The light power density was 75 mW/cm

2, identical to that used in the subsequent biological experiments. Absorption spectra were recorded, and the normalized absorbances at λ

maxAb were plotted as a function of illumination time, fitted with a monoexponential function (

Figure 2A,B), and used to estimate photostabilities through the decay half-lives (τ

1/2).

The cyanine dyes exhibited distinct differences in photostability, increasing in the order: 2ICy7COOH ≈ ICy7COOH < ICy7SO3H < ICy7CONHPr < Cy7COOH. Thus, the most photostable dye is Cy7COOH, while iodination facilitates photobleaching, likely due to the increasing population of the long-lived triplet state and increased probability of photochemical reactions. The higher stability of ICy7CONHPr compared with iodinated cyanines bearing negatively charged carboxylic groups suggests that the neutral amide group moderates the oxidative degradation rate by influencing dye–solvent interactions and restricting the access of reactive oxygen species to the polymethine chain. In contrast, the sulfonated derivative ICy7SO3H, which is highly polar and anionic, is more exposed to the aqueous environment, facilitating ROS-mediated oxidation. The overall trend demonstrates the intrinsic trade-off between photodynamic efficiency and photochemical stability: substituents promoting intersystem crossing and ROS generation simultaneously increase the vulnerability of the chromophore to photodecomposition.

The photostabilities decreased upon iodination in the following order: MB (τ1/2~17.5 min) > IMB (τ1/2~15.6 min) > 2IMB (τ1/2~2.9 min). When both dye families are compared, a clear difference in photostability behavior emerges. Under identical irradiation power (75 mW/cm), MB derivatives (MB, IMB, 2IMB) demonstrated substantially longer half-lives (minutes), whereas cyanine derivatives exhibited much faster decay (seconds). This pronounced contrast reflects intrinsic molecular differences between the phenothiazinium and polymethine scaffolds. While iodination in both series promoted intersystem crossing and enhanced ROS generation, its impact on photostability was more severe in the cyanines, causing rapid bleaching. Conversely, MB and its iodinated analogs maintained higher photochemical stability.

2.4. Quantum Yields of Singlet Oxygen and ROS Generation

Experimental conditions for measuring the quantum yields of singlet oxygen (ΦΔ) and ROS (φROS) generation, including the concentrations of the photosensitizer and scavenger (DPBF, SOSG, and H2DCFDA), as well as the light power density (irradiance) and illumination time, were optimized based on preliminary tests with varying parameters.

The singlet oxygen yields (Φ

Δ) for cyanine dyes in saline and methanol were previously reported [

21,

28] but remeasured in this work in saline (

Table 1) together with the new MB dye series to ensure that all experiments were performed under identical conditions. For both the cyanine and

MB derivatives, Φ

Δ values were determined in saline using SOSG as the singlet oxygen trap, and in methanol or acetonitrile using DPBF as a singlet oxygen scavenger.

Briefly, mixtures of dye and scavenger solutions were irradiated with a 730 nm LED (for cyanines) or a 632 nm LED (for MB derivatives) The increasing SOSG or H

2DCFDA fluorescence or the decreasing DPBF absorbance was plotted against irradiation time and fitted with a monoexponential decay function (

Figure 3 and

Figure 4). The corresponding time-dependent spectra are shown in

Figures S1–S3. The Φ

Δ values were calculated using Equation (2) with Cy7CO

2H (Φ

Δ = 9.5% in saline) [

28] and MB (Φ

Δ = 52% in acetonitrile) [

40] as the references (

Table 2).

To ensure that the measurements were completed within a practical time scale (longer than several seconds but shorter than several hours), irradiances of 100 mW/cm2 and 4 mW/cm2 were used for determining φROS of cyanines and MB derivatives, respectively. For ΦΔ measurements in saline, an irradiance of 40 mW/cm2 was applied to both dye series, while ΦΔ values of the cyanines in methanol and MB dyes in acetonitrile were obtained at 1 mW/cm2. The pronounced difference in irradiance reflected the distinct singlet oxygen and ROS generation efficiencies of the cyanine and MB dyes, as well as the differing sensitivities of the DPBF, SOSG, and H2DCFDA scavengers toward singlet oxygen and other photoinduced reactive species.

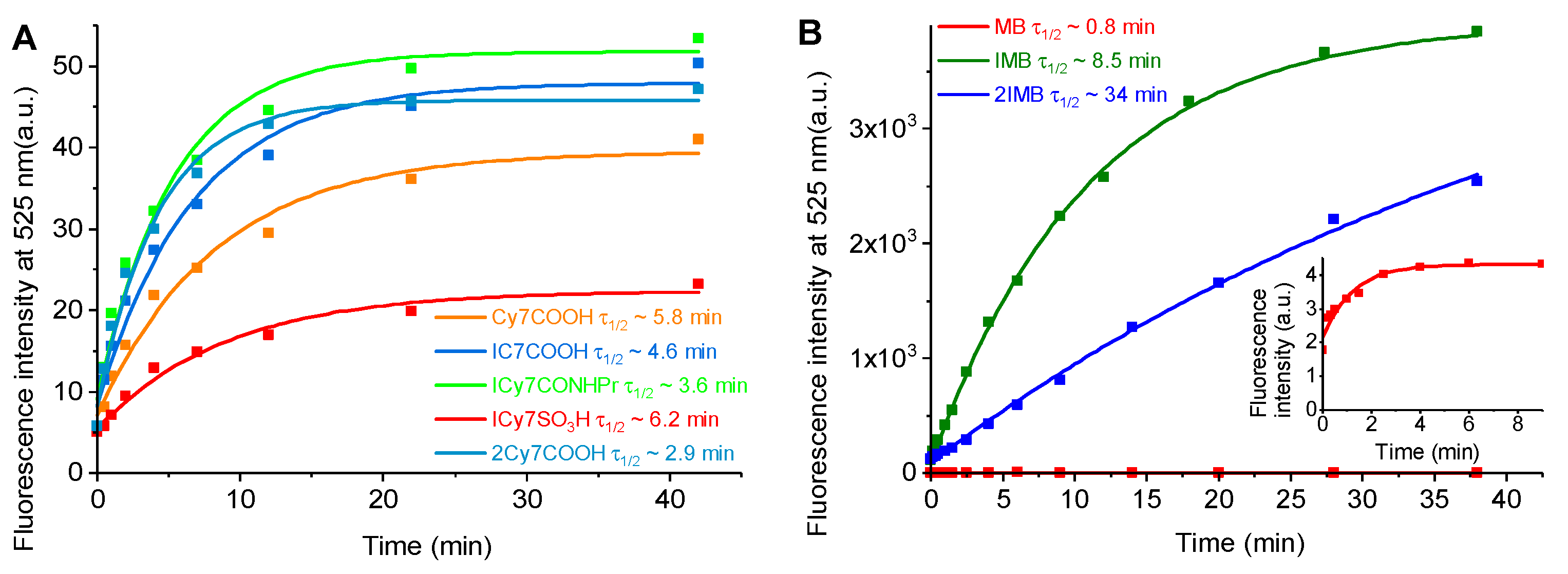

The yields of ROS generation (φ

ROS) for both dye classes were measured in saline by monitoring the increasing fluorescence intensity of DCF formed upon oxidation of H

2DCFDA under 632 nm (4 mW/cm

2) and 730 nm (100 mW/cm

2) irradiation for

MB derivatives and cyanines, respectively. The kinetic curves fitted with monoexponential functions are shown in

Figure 5A,B, and the φ

ROS values are given in

Table 1 and

Table 2. The corresponding time-dependent spectra are shown in

Figures S4 and S5.

Because the illumination time for the

MB derivatives (up to 90 s at 4 mW/cm

2,

Figure 4A) was much shorter than the photobleaching half-lives (2.9–17.5 min at 75 mW/cm

2,

Figure 2), the photobleaching effect on the φ

ROS measurements was negligible.

The quantum yield of ROS generation (φ

ROS) exhibits a clear increase upon iodination in both cyanines and

MB dye series:

Cy7CO2H <<

ICy7CONHPr <

ICy7CO2H <

ICy7SO3H <

2ICy7CO2H (

Table 1) and

MB <

IMB <

2IMB (

Table 2). In the cyanine dye series, φ

ROS depends not only on the number of iodine atoms but also on the solubilizing group. Thus, φ

ROS measured in saline for the mono-iodinated dyes increases in the following order:

ICy7CONHPr <

ICy7CO2H <

ICy7SO3H, whereas in methanol the order changes to

ICy7CO2H <

ICy7SO3H <

ICy7CONHPr.

The effects of iodines and solubilizing groups on the singlet oxygen generation yield (Φ

Δ) in the cyanine dye series were thoroughly discussed in our previous work [

28]. While iodination increases Φ

Δ measured in saline in the order

ICy7SO3H <

Cy7CO2H <

ICy7CO2H <

ICy7CONHPr <

2ICy7CO2H, in methanol the order differs:

Cy7CO2H <

ICy7CO2H <

ICy7SO3H <

2ICy7CO2H <

ICy7CONHPr. Remarkably, these orders are not the same as those observed for φ

ROS, which indicates that there is no correlation between φ

ROS and Φ

Δ. This non-synchronous change in φ

ROS and Φ

Δ indicates the generation of other ROS upon light irradiation, with their concentrations depending on the dye structure. Interestingly, the Φ

Δ values measured in aqueous saline are higher than those obtained in methanol.

An even stronger lack of correlation between φROS and ΦΔ in aqueous media was observed for the MB derivatives. While φROS increases upon iodination (MB < IMB < 2IMB), ΦΔ conversely, decreases (2IMB > IMB > MB) in non-aqueous (acetonitrile) media and even more so in aqueous saline. These findings suggest that the introduction of iodine atoms into MB reduces singlet oxygen production, as measured with SOSG and DPBF, while enhancing the generation of other ROSs that are not detectable by the H2DCFDA scavenger. Thus, in MB derivatives, iodination facilitates the switching of the photodynamic mechanism from Type II to Type I.

Notably, the iodinated

MB dyes are more efficient ROS generators than are iodinated cyanines. Because of the large difference in ROS generation efficiency between these two dye series, a direct quantitative comparison was not feasible. Accordingly, the ROS measurements required light doses of ~480 J/cm

2 (at 100 mW/cm

2) for the iodinated cyanines, whereas the

MB derivatives required doses about three orders of magnitude lower (~0.4 J/cm

2 at 3 mW/cm

2). Nevertheless, the quantum yields of singlet oxygen generation for both dye series in saline were comparable: 8.3–18.9% for the cyanines and 0.6–60.5% for the

MB derivatives. Φ

Δ was higher for the non-iodinated

MB (60.5%) than for the non-iodinated cyanine

Cy7CO2H (9.5%), whereas the opposite trend was observed for the mono-iodinated cyanines (8.3–14.1%) vs.

IMB (5.6%) and the di-iodinated cyanine

2ICy7CO2H (18.9%) vs.

2IMB (0.6%). The solvent strongly impacts the Φ

Δ of cyanines, increasing from 1.1–2.5% in methanol to 8.3–18.9% in saline [

28] (

Table 1), whereas iodinated

MB derivatives constitute 20–52% in acetonitrile and 0.6–60.5% in saline (

Table 2).

2.5. Dye Uptake by Fungi

The uptake of a dye by fungal cells is the second most important parameter, after ROS and singlet oxygen generation efficiency, for determining dye phototoxicity. Dye uptake was measured using a spectrophotometric method [

26]. Suspensions of

C.

albicans and

C.

parapsilosis (~10

6 cells/mL, 1 mL per well) were incubated in saline with the tested dyes at three concentrations (0.05, 0.1, and 0.5 µM) for 30, 45, and 60 min at each concentration. Control wells with saline and dye but no cells were included to correct for any non-cellular dye loss or adsorption. Dye uptake was quantified as the complement of the ratio of fluorescence intensity in the supernatant to the initial dye solution. All the measurements were repeated for each concentration and incubation period. The dye concentration and incubation time had no statistically significant effect on uptake.

The uptake of cyanine and

MB dyes by both fungal species moderately varied between 68 and 94% (

Table 3). Only the sulfonated cyanine

ICy7SO3H, characterized by increased hydrophilicity, showed notably reduced uptake (~27%). Iodination of

MB tended to increase cellular accumulation, likely due to enhanced hydrophobicity. In the cyanine series, iodination had a slight effect on uptake, which remained consistently high except for the hydrophilic

ICy7SO3H. These results suggest that differences in dye uptake between series and within series may have a minor to moderate influence on photocytotoxicity.

ICy7SO3H is predicted to have reduced phototoxicity because of substantially lower fungal accumulation.

This analysis of dye uptake complements photophysical data to explain variations in phototoxic effects between dyes.

2.6. Photodynamic Versus AmpB Eradication of Candida Strains

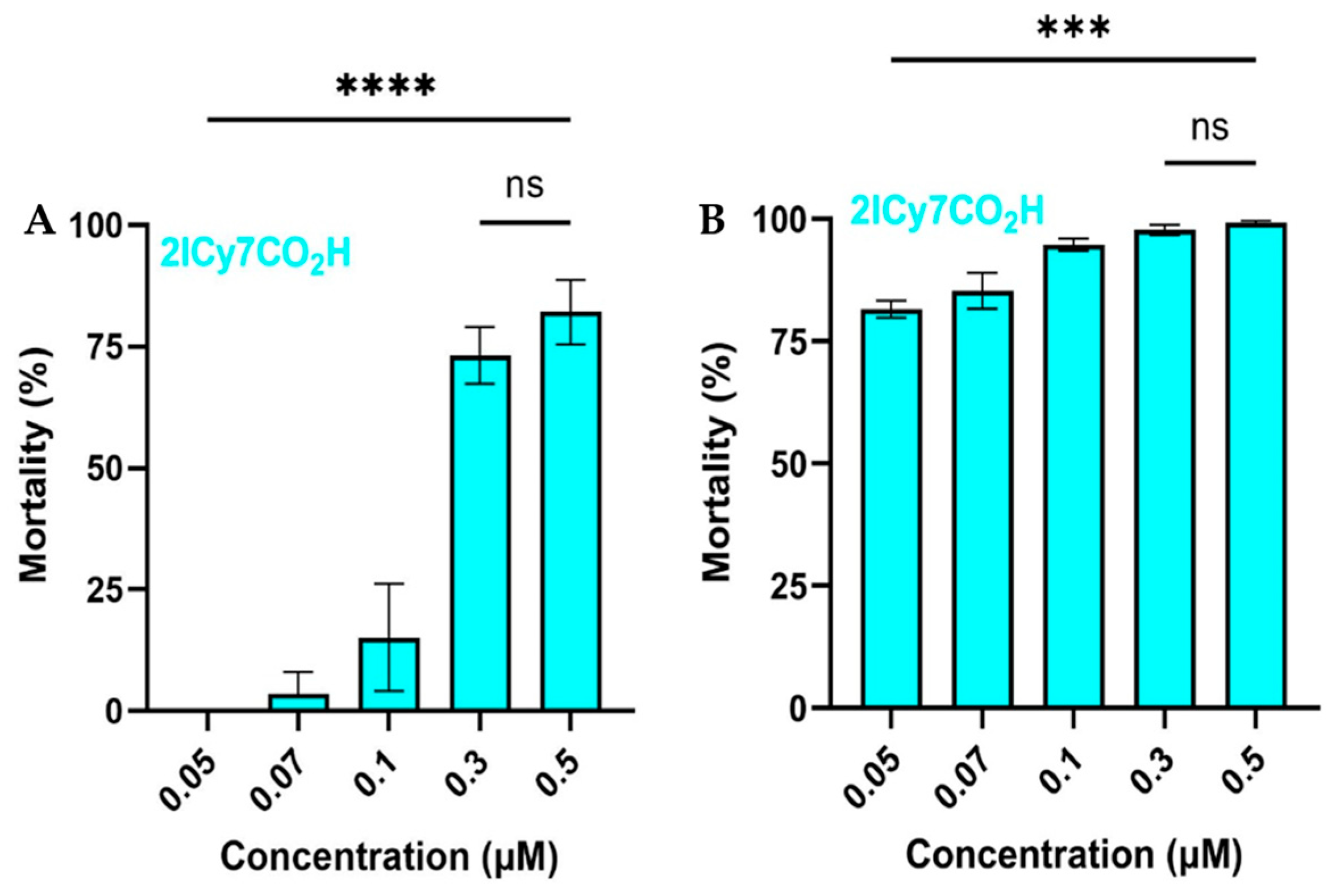

Next, we evaluated the antifungal response of C. albicans and C. parapsilosis to PDT with cyanine- and MB-based PSs and compared it with that of AmpB treatment. Fungal mortality was assessed using colony-forming unit (CFU) counts and quantified through the median lethal concentration (LC50), which represents the concentration that kills 50% of the cell population.

For the estimation of the photodynamic effect, fungal suspensions in saline were incubated with dyes at concentrations of 0.05, 0.07, 0.1, 0.3, and 0.5 µM for 30 min, followed by 30 min of illumination. Light exposure was performed at a dose of 115 J/cm2 (irradiance 75 mW/cm2) using a 30 W LEDs at 730 nm for cyanines and 632 nm for MB derivatives. This dose was optimized, as increasing it further did not enhance cell killing, while reducing it decreased phototoxicity. After treatment, the fungi were cultured, and mortality (%) was quantified as the ratio between CFU post-treatment and CFU without light exposure.

Control experiments confirmed that fungal inactivation was solely due to the PS photodynamic effect. Experiments in the dark revealed no fungal killing at any dye concentration. Additional controls with fungal samples incubated (i) in the dark without DMSO, (ii) in the dark with DMSO, and (iii) exposed to light with DMSO showed no effect on viability.

Upon light irradiation, both strains exhibited low sensitivity and failed to reach 50% mortality at any concentration, with non-iodinated dyes

Cy7CO2H and

MB reaching 0.5 µM (

Figure 6 and

Figure 7).

Conversely, PDT with iodinated cyanines achieved stronger killing, with sensitivity dependent on the dye structure. After treatment with monoiodo

ICy7CONHPr (

Figure 8A,B), both fungi exhibited photoinduced mortality.

C.

albicans showed higher mortality (

Figure 8B) with LC

50 at 0.06 µM (

C.

albicans) than

C.

parapsilosis (0.12 µM), with near-complete mortality at 0.5 µM in both strains.

Diiodo cyanine

2ICy7CO2H (

Figure 9A,B) exhibited even stronger eradication (compared to

ICy7CONHPr) causing nearly complete mortality of

C.

albicans at 0.1 µM but killing of

C.

parapsilosis by ~15%. The LC

50 values for

2ICy7CO2H were 0. 21 µM (

C.

parapsilosis) and 0.020 µM (

C.

albicans).

Compared to

ICy7CONHPr and

2ICy7CO2H, the carboxy-derivatized mono-iodinated cyanine

ICy7CO2H (

Figure 10) exhibited reduced phototoxicity against both fungal species. Significant efficacy was observed only at 0.5 µM, with LC

50 values of 0.45 µM for

C.

parapsilosis and 0.30 µM for

C.

albicans.

Sulfonated

ICy7SO3H lacked statistically significant phototoxicity (

Figure 11), which is consistent with its low fungal uptake.

While

MB exhibits very low phototoxicity, iodinated

IMB (

Figure 12) and especially diiodinated

2IMB (

Figure 13) dyes show markedly increased phototoxicity.

2IMB has a photokilling effect (~85% mortality at

cDye = 0.5 µM) on

C.

parapsilosis comparable to that of the iodinated cyanine

ICy7CONHPr. However, we did not achieve complete eradication of

C.

albicans with iodinated

MB dyes, even at the maximal concentration tested (0.5 µM), whereas the iodinated cyanines

ICy7CONHPr (

Figure 8B) and

2ICy7CO2H (

Figure 9B) caused nearly 100% cell death.

The photokilling efficacy of

2IMB, estimated by the LC

50, was approximately 2.5-fold higher for

C.

albicans and 1.5-fold higher for

C.

parapsilosis than for

IMB (

Table 4). The LC

50 values for

IMB (0.45 µM for

C.

albicans and 0.34 µM for

C.

parapsilosis) and

2IMB (0.18 µM for

C.

albicans and 0.23 µM for

C.

parapsilosis) indicated that both dyes were less efficient PSs than were the mono- and di-iodinated cyanines, except for

ICy7CO2H, which was less effective than

2IMB. The strongest photokilling effect against both fungal species was observed for diiodinated

2ICy7CO2H and monoiodinated

ICy7CONHPr. In

C.

parapsilosis,

2IMB had an effect similar to that of

2ICy7CO2H, although its efficacy was approximately half that of

ICy7CONHPr.

The obtained phototoxicity data for the PSs were compared with those for conventional therapy using

AmpB applied at the same concentrations (0.05, 0.07, 0.1, 0.3, and 0.5 μM).

Figure 14 shows that the highest tested concentration of 0.5 μM

AmpB induced only approximately 25% mortality of

C.

parapsilosis, which is considered insufficient for clinical treatment. Owing to this limited efficacy, no LC

50 value could be determined for

AmpB against

C.

parapsilosis within the tested concentration range.

In contrast,

AmpB was more effective against

C.

albicans, resulting in approximately 75% mortality at 0.5 μM (LC

50 = 0.20 μM,

Table 4). The

AmpB concentration needed to achieve 25% mortality in

C.

parapsilosis was tenfold higher (0.5 µM) than that required for the same effect in

C.

albicans (0.05 µM). Nonetheless, the 75% mortality observed with

AmpB in

C.

albicans was still inferior to that of PDT with the iodinated cyanines

ICy7CONHPr (

Figure 8B) and

2ICy7CO2H (

Figure 9B), which presented LC

50 values of 0.06 μM and 0.02 μM, respectively, and almost completely eradicated this strain even at 0.3 μM.

3. Discussion

In this study, the efficacy of PDT based on photosensitizers from the cyanine and

MB families was evaluated against

C.

albicans and

C.

parapsilosis. These findings reveal species-dependent susceptibility and considerable differences in compound performance.

AmpB, the first-line antifungal agent, was moderately effective against

C.

albicans, whereas significantly higher concentrations were required to achieve a similar effect against

C.

parapsilosis. This observation is in agreement with previous reports [

41] and underscores the need for alternative therapeutic strategies. Therefore, we considered photosensitizers that exhibited measurable LC

50 values for

C.

parapsilosis within the tested range as effective against this species. With respect to

C.

albicans, we assumed that photosensitizers with LC

50 values lower than those of

AmpB may offer a therapeutic advantage.

The antifungal activity of cyanine derivatives upon light irradiation demonstrated a clear dependence on both the presence of iodine atoms and the linker functional group. The non-iodinated photosensitizer

Cy7CO2H did not have a measurable LC

50, whereas the introduction of one iodine atom, such as

ICy7CO2H markedly enhanced antifungal activity. The di-iodinated dye

2ICy7CO2H achieved nearly complete killing at the highest concentration tested (0.5 µM) and exhibited the lowest LC

50 values in both species. Similar results were obtained for

ICy7CONHPr, which has a single iodine atom but contains an amide rather than a carboxylic group at its linker terminus, a modification likely affecting solubility, membrane permeability, and intracellular localization [

28]. In contrast, iodinated

ICy7SO3H displayed weak antifungal activity due to its pure uptake associated with reduced lipophilicity and repulsion between negatively charged dye molecules and negatively charged phospholipids in fungal membranes.

Within the

MB family, the parent

MB dye exhibited limited antifungal efficacy in both species, which is consistent with earlier reports [

42]. As expected, its iodinated derivatives,

IMB and

2IMB, demonstrated markedly enhanced phototoxic activity. Interestingly,

IMB showed the opposite species sensitivity pattern.

C.

parapsilosis was slightly more susceptible than

C.

albicans possibly due to differences in its intracellular localization or metabolism. The di-iodinated derivative

2IMB further amplified the effect, achieving over 75% killing in both species at 0.5 µM. In addition to their high efficacy,

IMB and

2IMB offer practical advantages:

MB is inexpensive and widely available, and iodination requires only a single synthetic step, unlike the more complex and costly synthesis of iodocyanine derivatives.

The enhanced antifungal activity following iodination can be explained by the heavy-atom effect. The incorporation of heavy atoms such as iodine increases intersystem crossing (ISC) through spin–orbit coupling, promoting triplet-state formation and the subsequent generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), including singlet oxygen. In this study, ICy7CO2H and IMB, each bearing one iodine atom, presented similar LC50 values (0.30 µM and 0.45 µM, respectively) in C. albicans, whereas their non-iodinated counterparts (Cy7CO2H and MB) exhibited weak or undetectable activity. The difference became even more pronounced when mono- and di-iodinated sensitizers were compared: 2ICy7CO2H was approximately 15-fold more potent than ICy7CO2H, and 2IMB was almost twice as effective as IMB.

The quantum yields of singlet oxygen generation (Φ

Δ) and overall ROS formation (φ

ROS) were measured to better understand the photochemical contribution to antifungal activity. These parameters were determined using specific scavengers for each photosensitizing mechanism: DPBF and SOSG, preferably specific for singlet oxygen (Type II photosensitization) [

43], and less specific H

2DCFDA for radical ROS (Type I photosensitization) [

44]. Typically, both Type I and Type II mechanisms can operate concurrently, with their relative contributions depending on factors such as the oxygen concentration, chemical structure of the PS, and microenvironment [

45].

Analysis of the cyanine derivatives indicated that iodination affects the two photochemical pathways differently. An increase in the number of iodine atoms led to higher singlet oxygen yields and an even more pronounced enhancement in overall ROS generation. Owing to their different solubilizing properties, the terminal functional group at the linker also strongly influences photochemical behavior and cell uptake. The monoiodinated ICy7CONHPr, which displayed antifungal activity similar to that of the diiodinated 2ICy7CO2H, produced relatively low levels of ROS but elevated levels of singlet oxygen. Conversely, despite its low antifungal activity, ICy7SO3H presented relatively high ΦΔ and φROS values in aqueous media (e.g., relative to IMB and 2IMB). However, as mentioned above, its low membrane permeability (uptake) limits its phototoxicity. These observations suggest that iodination and functional group modification can differentially alter ROS generation and antifungal efficacy.

For the MB derivatives, the opposite trend was observed: ΦΔ decreased with iodination (MB > IMB > 2IMB), whereas overall ROS generation increased (MB < IMB < 2IMB). This pattern reflects a mechanistic shift from a singlet-oxygen-dominated Type II pathway in MB to a radical-mediated Type I photosensitization process in the iodinated derivatives. Mechanistically, the iodine atoms introduced into the MB derivatives play a crucial role in this photodynamic switch. In addition to enhancing intersystem crossing (ISC) through the heavy-atom effect, these iodine atoms can directly participate in electron-transfer reactions from the dye triplet state to molecular oxygen or other substrates. This electron-transfer pathway promotes the formation of radical species such as superoxide and hydroxyl radicals, which are characteristic ROSs involved in Type I photosensitization, in contrast to singlet oxygen generated via energy transfer in Type II processes. Moreover, iodinated MB derivatives may generate reactive iodine species via redox cycling, further amplifying radical ROS production. Therefore, the iodine atoms themselves facilitate enhanced radical generation through electron transfer, inducing a mechanistic shift from predominantly singlet oxygen-based Type II photochemistry towards Type I radical pathways.

Furthermore, a sharp decline in the fluorescence quantum yield (Φ

F) was observed with iodination: while

MB exhibited strong fluorescence,

IMB and

2IMB were almost non-fluorescent, with the emission intensity decreasing by orders of magnitude as the number of iodine atoms increased. This finding supports the hypothesis that iodination promotes deactivation of the singlet-excited state via ISC to the triplet state, thereby explaining both the mechanistic shift and the higher antifungal efficiency of

2IMB despite its relatively low Φ

Δ value. The observed decrease in fluorescence quantum yield with increasing iodination can be explained by the absorption spectra, which show that the addition of iodine atoms enhances the shoulder on the blue side, indicating the formation of

H-aggregates. In most cases, such

H-aggregates lead to a pronounced reduction in fluorescence intensity due to excitonic interactions and quenching effects [

23].

Photostability experiments revealed that

MB was more stable in aqueous solution than its iodinated counterparts, with

2IMB being the least stable. The reduced stability of the iodinated derivatives may result from an increased ISC rate and triplet state lifetime (associated with enhanced ROS production), since dissolved oxygen facilitates photobleaching through singlet-oxygen formation from the triplet state [

22,

23]. In contrast, iodocyanines exhibited relatively good photochemical stability compared with iodo-

MBs. Biologically, greater stability may prolong activity; however, when ROS production is rapid and intense, as observed for

IMB, reduced stability may be compensated by strong antifungal efficacy within short time frames.

In addition to photochemical properties, cellular uptake plays a major role in determining antifungal efficacy. Iodocyanines showed high cellular uptake in both fungal species except for ICy7SO3H, which exhibited much lower penetration. The uptake of PSs was, in general, only negligibly higher for C. albicans than for C. parapsilosis; therefore, the increased mortality of C. albicans upon treatment with PSs and AmpB is more likely due to the increased sensitivity of this strain.

Although photosensitizer uptake was similar between

C.

albicans and

C.

parapsilosis, the greater PDT susceptibility of

C.

albicans may reflect intrinsic biological differences between the species. Previous studies have shown that

C.

albicans forms a thicker and more complex biofilm than

C.

parapsilosis [

46], and that the two species also differ in cell-wall mannan organization and lipid homeostasis systems [

47]. In

C.

parapsilosis, the stearoyl-CoA desaturase Ole1 plays a central role in the synthesis of unsaturated fatty acids (UFAs), which are essential to maintaining membrane fluidity, stability, and appropriate stress responses [

48]. This enhanced ability to regulate and preserve membrane lipid composition may provide

C.

parapsilosis with an advantage in coping with photodynamically induced membrane damage, contributing to the higher resilience observed under the PDT conditions tested. Nevertheless, these mechanisms were not directly examined in the present study and warrant further investigation.

Overall, these findings suggest that iodinated cyanines represent a more promising structure for developing highly phototoxic PSs against both C. albicans and C. parapsilosis, while iodinated MB derivatives have comparable efficiency in C. parapsilosis. An additional advantage of iodinated cyanines over MB derivatives is their strong fluorescence, which enables real-time monitoring in vivo. There is a high probability that further improvement of iodinated cyanines can be achieved by combining the structural benefits of ICy7CONHPr and 2ICy7CO2H, specifically by derivatizing the carboxylic group in 2ICy7CO2H with propylamide. An important advantage of iodinated MB derivatives over cyanines is their synthetic accessibility and substantially lower production cost.

The cytotoxicity of photosensitizers arises from a combination of factors, including singlet oxygen generation, the type and yield of free radicals, the membrane permeability of these RSs, their intracellular localization, and their accumulation within particular organelles such as mitochondria, lysosomes, and the rough endoplasmic reticulum (RER).

Future research should focus on elucidating the precise biological mechanisms underlying the antifungal efficacy of photosensitizers, including singlet oxygen and ROS generation, membrane permeability of reactive species, intracellular localization, and accumulation within key organelles such as mitochondria and lysosomes. Detailed studies on the cellular uptake pathways and subcellular targeting will enhance the understanding of PS functionality and optimize design.

Furthermore, validation of these photosensitizers under relevant in vivo conditions is essential for assessing their therapeutic potential and safety profiles in complex biological systems. Optimizing treatment parameters, including photosensitizer concentrations, light dosimetry, and exposure timing, is critical for maximizing effectiveness while minimizing side effects.

Advances in PS structural optimization, particularly combining beneficial features from cyanine derivatives (e.g., ICy7CONHPr and 2ICy7CO2H), could improve efficacy and selectivity. The integration of real-time fluorescence imaging to monitor PS delivery and localization in vivo offers opportunities for personalized therapy and treatment monitoring.

Finally, exploration of combination therapies, such as coupling PDT with conventional antifungals or immune modulators, may enhance the efficacy against resistant fungal strains and biofilms, addressing current challenges in antifungal treatment.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. General

All chemicals were obtained from Alfa Aesar Israel and Sigma-Aldrich, Israel. The solvents were sourced from Bio-Lab Israel and used without further purification. The progress of the chemical reactions was monitored using thin-layer chromatography (TLC) on Silica gel 60 F-254 plates (Merck, Israel) and by LC/MS analysis. LC/MS measurements were performed with an Agilent Technologies 1260 Infinity LC system coupled to a 6120 quadrupole mass spectrometer (MS) with an Agilent Zorbax SB-C18 column (1.8 µm, 2.1 mm × 50 mm) maintained at 50 °C. The mobile phase consisted of water and acetonitrile (ACN) with 0.1% formic acid. High-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS) was performed in positive electrospray ionization (ESI) mode using an Agilent 6550 iFunnel Q-TOF LC/MS detector. Proton (1H) and carbon (13C) NMR spectra were recorded on a Bruker Avance III HD spectrometer operating at 400 MHz (1H) and 100 MHz (13C) and equipped with a BBO probe and a Z-axis gradient coil.

4.2. Synthesis of Photosensitizers

4.2.1. Cyanines

While specific synthetic procedures for cyanines are not detailed here, they follow conventional condensing agent-mediated methods, as described in previous studies [

21,

28]. These reactions involve a one-pot sequential reaction of

N-[5-(phenylamino)-2,4-pentadienylidene]aniline with the first indolenine molecule in acetic anhydride to form a corresponding

N-phenylacetamide derivative, which subsequently reacts with the second indolenine in the presence of pyridine.

4.2.2. Iodinated Methylene Blue (IMB)

p-Toluenesulfonic acid (pTSA, 26.9 mg, 0.156 mmol) and N-iodosuccinimide (NIS, 28 mg, 0.125 mmol) were added to a suspension of MB (50 mg, 0.156 mmol) in acetonitrile and stirred at RT for 1 h. The obtained IMB was column-purified (Silica gel) using a dichloromethane (DCM)–methanol (MeOH) gradient, starting from 3% MeOH and increasing to 10% MeOH. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6, ppm): δ 8.14 (s, 1H), 7.47 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H), 7.10 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 3.34 (s, 12H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6, ppm): δ 159.7, 157.7, 152.0, 151.7, 148.1, 144.3, 138.3, 132.0, 129.4, 127.6, 123.2, 119.8, 43.3, 38.3. HRMS m/z (ESI+) C16H17IN3S+ calculated [M]+ 410.0187, found m/z: 410.0200.

4.2.3. Diiodinated Methylene Blue (2IMB)

In a suspension of MB (50 mg, 0.156 mmol) in acetonitrile, 4-toluenesulfonic acid (26.9 mg, 0.156 mmol) and N-iodosuccinimide (NIS, 70 mg, 0.312 mmol) were added. The mixture was stirred at RT for 2 h. The resulting diiodinated product, 2IMB, was purified by column chromatography on Silica gel using a dichloromethane (DCM)–methanol (MeOH) gradient, starting from 3% MeOH and increasing to 10% MeOH. 1H NMR (400 MHz, chloroform-d, ppm): δ 7.51 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 2H), 7.06 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 2H), 2.77 (s, 12H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, Chloroform-d, ppm): δ 158.8, 150.5, 142.1, 131.6, 128.3, 119.2, 45.4. HRMS m/z (ESI+) C16H16I2N3S+ calculated [M]+ 535.9154, found m/z: 535.9156.

4.3. Absorption and Fluorescence Measurements

The absorption and emission characteristics of the cyanine dyes were obtained from our previous studies [

21,

28]. For the

MB derivatives, absorption spectra were recorded using a Jasco V-730 UV–Vis spectrophotometer, and fluorescence spectra were measured on an Edinburgh FS5 spectrofluorometer. Measurements were conducted at 25 °C in a standard 1-cm quartz cuvette at an excitation wavelength (λ*) of 620 nm.

To determine the absolute fluorescence quantum yields (ΦF), the integrated relative intensities of the dye were measured vs. the commercially available MB as the reference (ΦF = 2%), and the quantum yields were calculated according to Equation (1).

The absolute fluorescence quantum yields (Φ

F) were determined by comparing the integrated fluorescence intensities of the sample dyes with a commercially available

MB reference (Φ

F = 2%) [

39]. The quantum yields were calculated according to Equation (1).

where Φ

F,Ref is the quantum yield of the reference,

FRef and

F are the integrated emission intensities (i.e., areas under the emission spectra) of the emission spectra of the reference and sample dyes, respectively, and

ARef and

A are the absorbances of the reference and sample dyes at the excitation wavelength.

4.4. Photostability

Stock solutions of the dyes were prepared in DMSO and diluted in 0.9% physiological saline to achieve final absorbances of approximately 0.03 at 632 nm. All the solutions contained 0.7% DMSO. The solutions were filtered using syringe filters and transferred to standard 1-cm quartz cuvettes. Light irradiation was performed using a 30 W LED equipped with a 60° lens to disperse light uniformly. The distance between the light source and the samples for MB derivatives was 8.0 cm (irradiated at 632 nm). The light power density was maintained at 75 mW/cm2.

Absorption spectra were recorded over predefined time intervals. The normalized absorbance at the absorption maximum of the dye was plotted as a function of illumination time. These data were fitted with a monoexponential decay function to estimate photostability via the decay half-life (τ1/2). All measurements were performed in triplicate, and average values were reported.

4.5. Quantum Yields of Singlet Oxygen Generation

The singlet oxygen quantum yields (Φ

Δ) of the cyanine dyes in methanol were taken from our previous publications [

21,

28], whereas those in saline were measured in this work. For the

MB derivatives, Φ

Δ was measured in acetonitrile following the method described in [

40]. Solutions containing 1,3-diphenylisobenzofuran (DPBF, absorbance ~0.20 at 410 nm) and the MB-derivatized dye under examination (absorbance ~0.25 at an excitation wavelength of 632 nm) were prepared in acetonitrile. Samples of

MB,

IMB, and

2IMB were placed in standard 1-cm quartz cuvettes and irradiated at a 50 cm distance using a 632 nm, 30 W LED with a 60° lens for light dispersion at a light power density of 1 mW/cm

2.

Absorption spectra were collected over time, and DPBF absorbances at 410 nm were corrected for dye absorbance overlap measured under identical conditions without DPBF. The corrected DPBF absorbance data were normalized, plotted against irradiation time, and fitted with first-order exponential decay functions. The Φ

Δ values were calculated using Equation (2), with

MB (Φ

Δ = 52% in acetonitrile [

40]) as the reference.

where Φ

Δ,Ref is the singlet oxygen quantum yield of the reference dye (

MB),

k and

kRef are the DPBF degradation rates derived from the kinetic fits for the sample and reference dyes, respectively, and

A and

ARef are the absorbances of the sample and reference dyes at the excitation wavelength (632 nm), respectively.

The Φ

Δ values for the cyanine and

MB dye series in saline were measured using a procedure similar to that described above for

MB in acetonitrile. Solutions containing SOSG (5 mM) and cyanine or

MB-derivatized dye in saline with 15% DMSO (

A = 0.10 at 730 nm and 630 nm, respectively) were irradiated using a 730 nm LED for cyanine and a 632 nm LED for

MB dyes (30 W, irradiance 40 mW/cm

2). The fluorescence intensities at 525 nm (SOSG emission) were plotted as a function of irradiation time and fitted with first-order exponential decay functions. The Φ

Δ values were calculated using Equation (2), with

Cy7CO2H (Φ

Δ = 9.5% [

28]) as the reference.

Each experiment involving the ΦΔ measurements was performed in triplicate, and the average ΦΔ values were reported.

4.6. Quantum Yield of ROS Generation

The quantum yields of reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation (φROS) were determined using the fluorogenic probe 2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (H2DCFDA, Lumiprobe, Batch 9GC7V). Upon light irradiation in the presence of photosensitizers, H2DCFDA is oxidized to fluorescent dichlorofluorescein (DCF).

Stock solutions of PSs and H2DCFDA were prepared in a minimal volume of methanol and subsequently diluted with saline. The final PS concentrations were adjusted to yield an absorbance of approximately 0.15 at the excitation wavelength (632 nm for MB dyes and 730 nm for cyanines). The samples containing H2DCFDA (absorbance ~0.20) and the PS under investigation (absorbance ~0.15) were irradiated with a 632 nm, 30 W LED positioned 30 cm from the sample, with a light power density of 4 mW/cm2 for the MB derivatives. The cyanine dyes were irradiated with a 730 nm, 30 W LED at 5 cm, delivering a light power density of 100 mW/cm2.

Fluorescence spectra were recorded over time with excitation at 495 nm (appropriate for DCF excitation). Kinetic curves representing the fluorescence intensity of DCF at 525 nm versus illumination time were fitted to monoexponential functions. The φ

ROS values were calculated using Equation (3):

where φ

ROS,Ref is the ROS quantum yield of the reference dye (either

MB or

ICy7CO2H),

k and

kRef are the rates of DCF fluorescence increase obtained from the fittings for the sample and reference dyes, respectively, and

A and

ARef denote absorbances of the sample and reference dyes at their excitation wavelengths (632 nm for MB dyes, 730 nm for cyanines).

Control experiments, which were conducted without photosensitizers under identical irradiation conditions, confirmed that the minimal contribution from the intrinsic fluorescence increase in H2DCFDA.

All the measurements were performed in triplicate, and the averaged φROS values are reported.

4.7. Fungal Strains

Two fungal strains, C. albicans (ATCC 24433) and C. parapsilosis (ATCC 22019), which were supplied by Beit HaEmek (Israel), were used in this study.

4.8. Preparation and Growth of Fungi

C. albicans and C. parapsilosis strains were cultured on Difco™ Yeast Mold (YM) agar plates (BD, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) and incubated at 37 ± 1 °C for 48 h. Subsequently, 2–3 yeast colonies were inoculated into Difco™ YM broth (BD) and incubated with shaking at 200 rpm for 24 h at 37 ± 1 °C.

The resulting fungal suspension was diluted with physiological saline (0.90% w/v NaCl in distilled water) to achieve optical densities of A530 = 0.10 ± 0.02 for C. albicans and A490 = 0.10 ± 0.02 for C. parapsilosis. Absorbance measurements were performed using a Genesys 10S UV–Vis spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA). In accordance with the 0.5 McFarland standard method, these absorbance values correspond to a cell concentration of approximately 1 × 106–3 × 106 cells/mL.

4.9. Dye Uptake by Fungal Cells

Suspensions of C. albicans and C. parapsilosis (~106 cells/mL, 1 mL per well) were incubated in physiological saline containing the test dyes at three concentrations (0.05, 0.1, and 0.5 µM) at 25 °C in the dark for predetermined time intervals (30, 45, and 60 min). Following incubation, the samples were centrifuged at 13,400 rpm for 12 min to pellet the fungal cells. The supernatants containing unbound dye were carefully collected.

The fluorescence intensities of the supernatants (

Fsupernatant) and corresponding reference dye solutions without fungal cells (

FDye) were measured at emission maxima specific to each dye using an Infinite M200 ELISA microplate reader (Tecan). Dye uptake was quantified as the complement of the ratio of fluorescence intensity in the supernatant to that in the initial dye solution, expressed as a percentage according to Equation (4).

All measurements were performed in triplicate for each dye concentration and incubation period, and average values were reported.

4.10. Photodynamic Treatment of C. albicans and C. parapsilosis

All preparatory procedures involving photosensitizers were performed in the dark to prevent premature activation and photobleaching. Stock solutions of cyanines and MB dyes were prepared in DMSO at concentrations of 0.05, 0.07, 0.1, 0.3, and 0.5 µM (confirmed spectrophotometrically). Subsequently, 10 µL of each dye solution was added to 1 mL of fungal suspension (103 cells/mL) in 0.9% saline in a Falcon® 48-well polystyrene clear flat-bottom plate at a final DMSO concentration of 1% for all the samples.

The samples were incubated in the dark at RT for 30 min, followed by exposure to light under continuous shaking for an additional 30 min. Control samples were kept in the dark. Light exposure was carried out using 30 W LEDs emitting at 730 nm for cyanines and at 632 nm for MB derivatives, each equipped with a 60° lens for light dispersion. The light source was positioned at 6.5 cm (cyanines) and 8.0 cm (MB dyes) from the samples, delivering an irradiance of 75 mW/cm2 and a light dose of 115 J/cm2.

Post-irradiation, 100 µL aliquots of each sample were spread onto YM agar plates via a Drigalski spreader and incubated at 37 ± 1 °C for 24 h (C. albicans) or 48 h (C. parapsilosis). Colony-forming units (CFUs) were quantified using a Scan 500 colony counter (Interscience, Saint-Nom-la-Bretèche, France). Dark toxicity was assessed in parallel by conducting identical procedures without light exposure.

The control groups included fungal samples incubated under the following conditions: (i) in the dark without DMSO, (ii) in the dark with 1% DMSO, and (iii) exposed to light with 1% DMSO. All experiments were performed in duplicate and repeated three times on different days to ensure reproducibility.

Fungal mortality was evaluated based on CFU counts and quantified by calculating the median lethal concentration (LC50) required to kill 50% of the cell population. Each experiment was performed in triplicate, and average values were reported.

4.11. Statistical Analysis

The data are presented as the means ± SDs from at least three independent experiments (n = 3). Statistical comparisons were performed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test to compare each treatment group against the control. All the analyses were conducted via GraphPad Prism version 10.0.1. Statistical significance was determined based on adjusted p-values from Dunnett’s test, which accounts for multiple comparisons while controlling for the family-wise error rate.