Carvacrol@ZnO and trans-Cinnamaldehyde@ZnO Nanohybrids for Poly-Lactide/tri-Ethyl Citrate-Based Active Packaging Films

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Characterization of CV@ZnO and tCN@ZnO Nanostructures

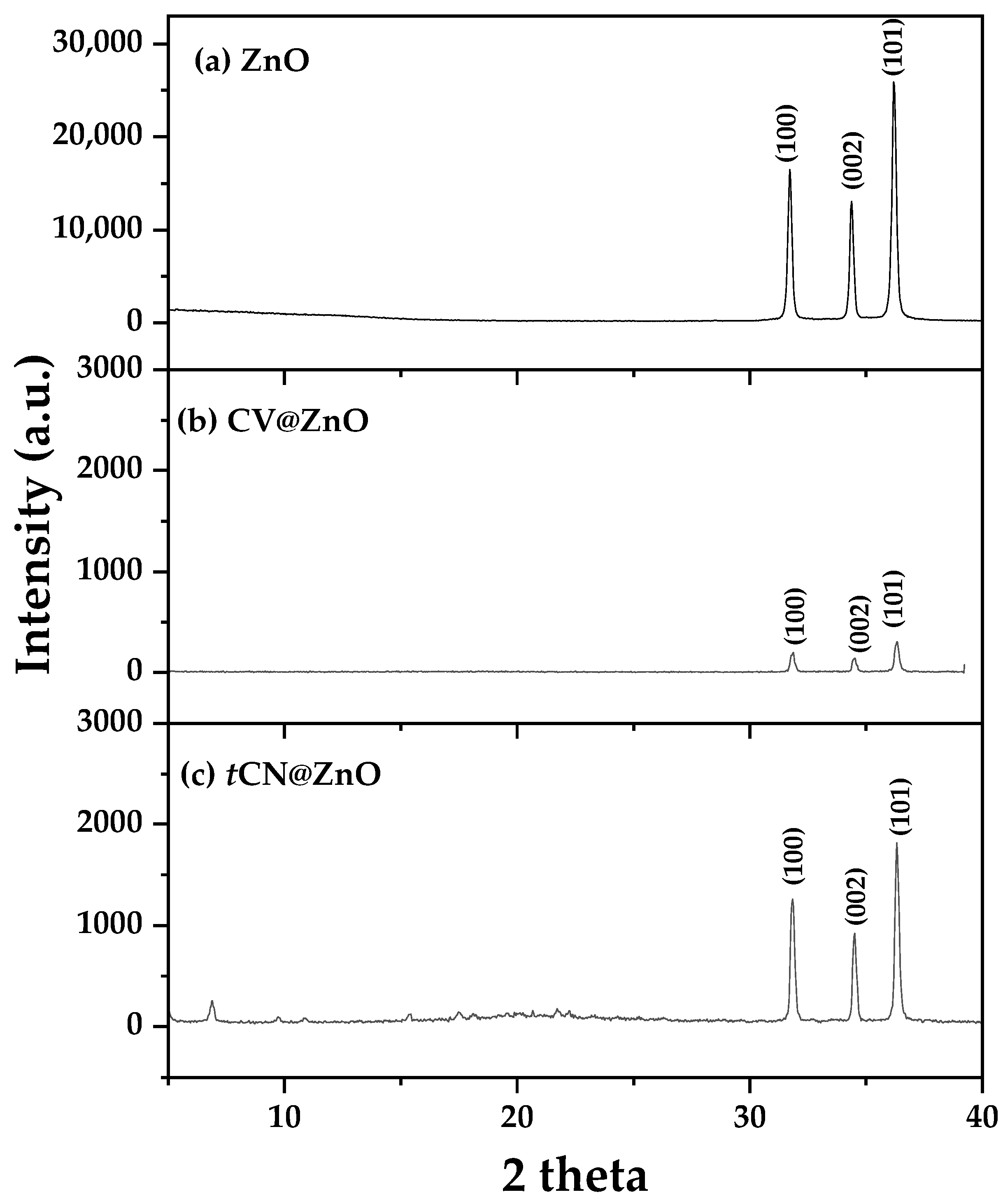

2.1.1. Nanohybrids’ XRD Analysis

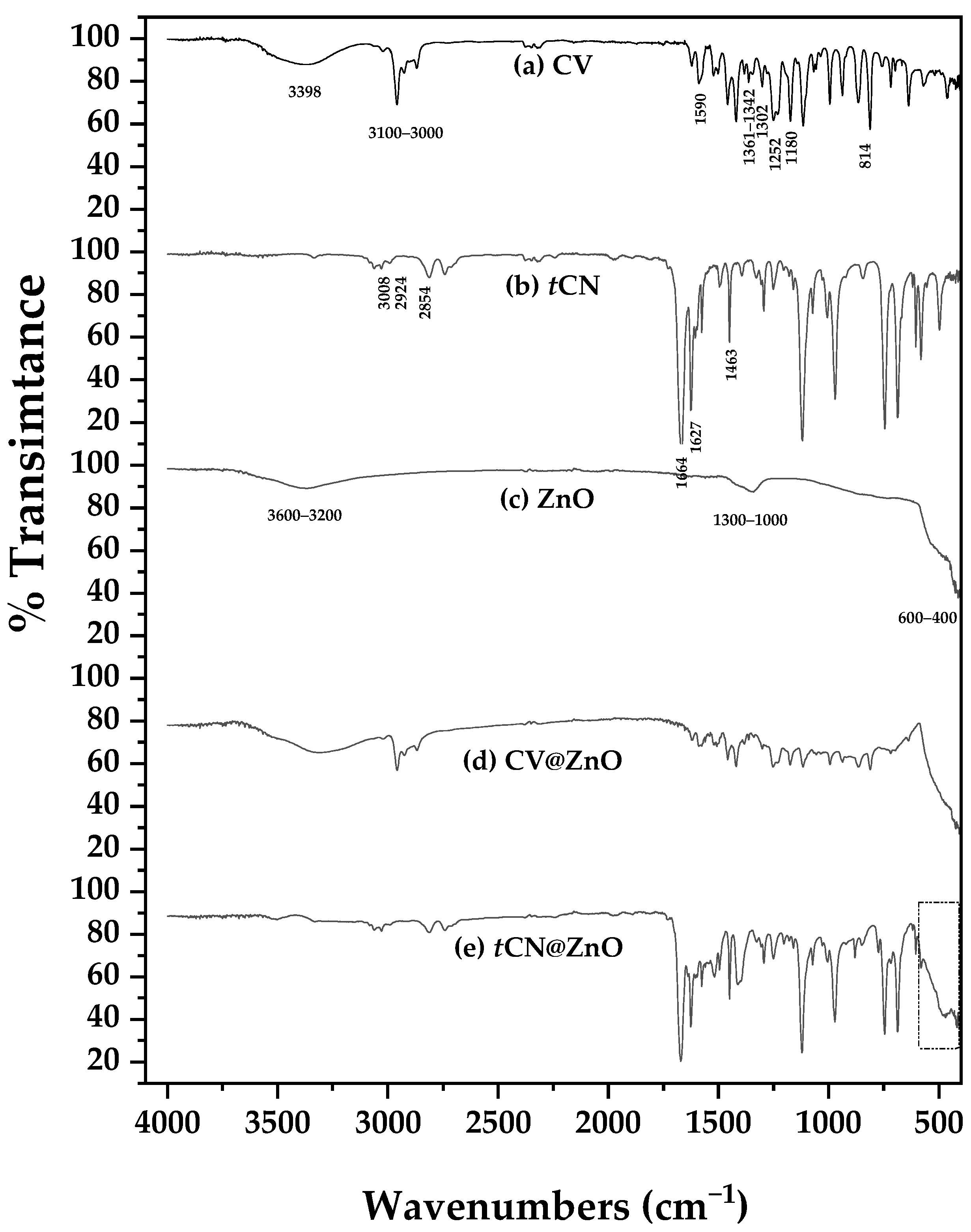

2.1.2. Nanohybrids’ ATR-FTIR Analysis

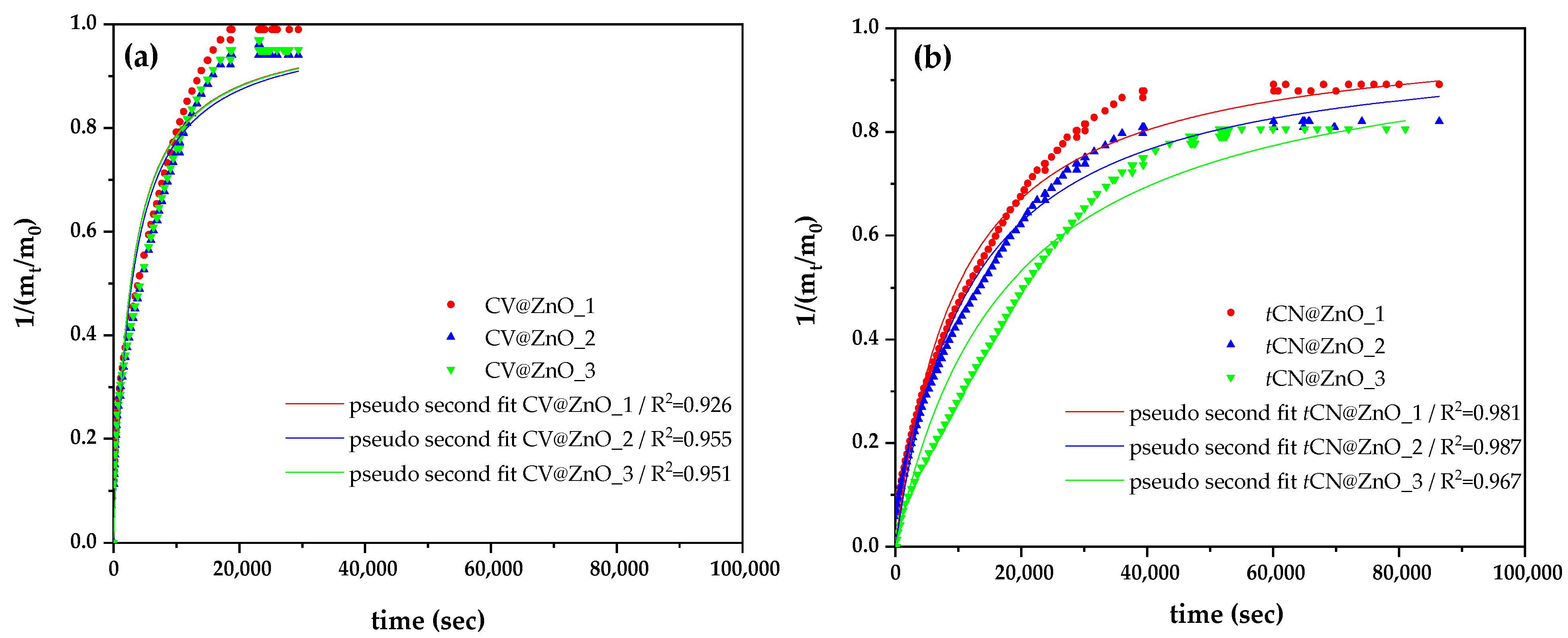

2.1.3. Release Kinetics from Nanohybrids

2.1.4. Nanohybrids’ Antioxidant Activity

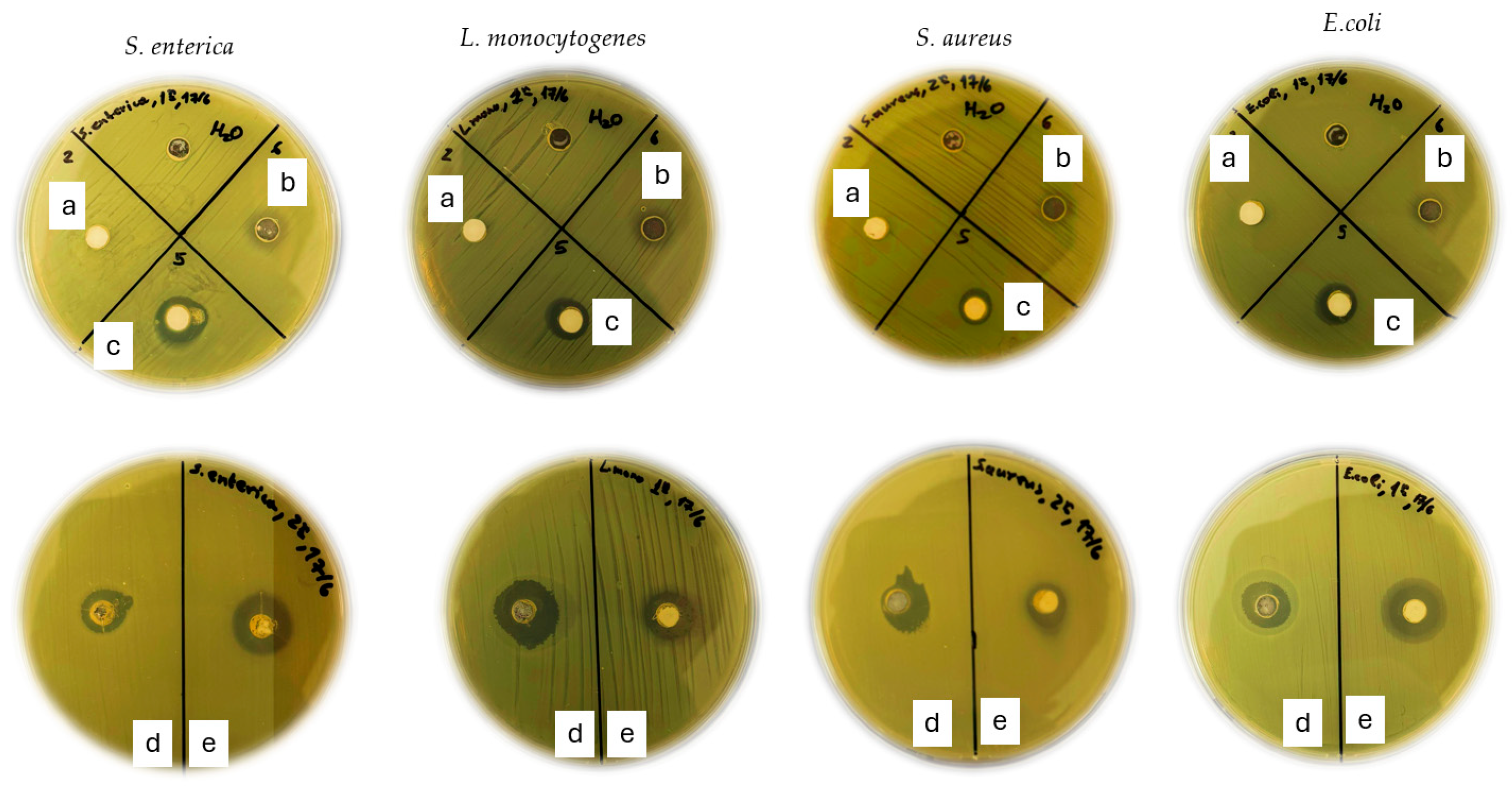

2.1.5. Nanohybrids’ Antibacterial Activity

2.2. Characterization of PLA/TEC/xZnO, PLA/TEC/xCV@ZnO, and PLA/TEC/xtCN@ZnO Active Films

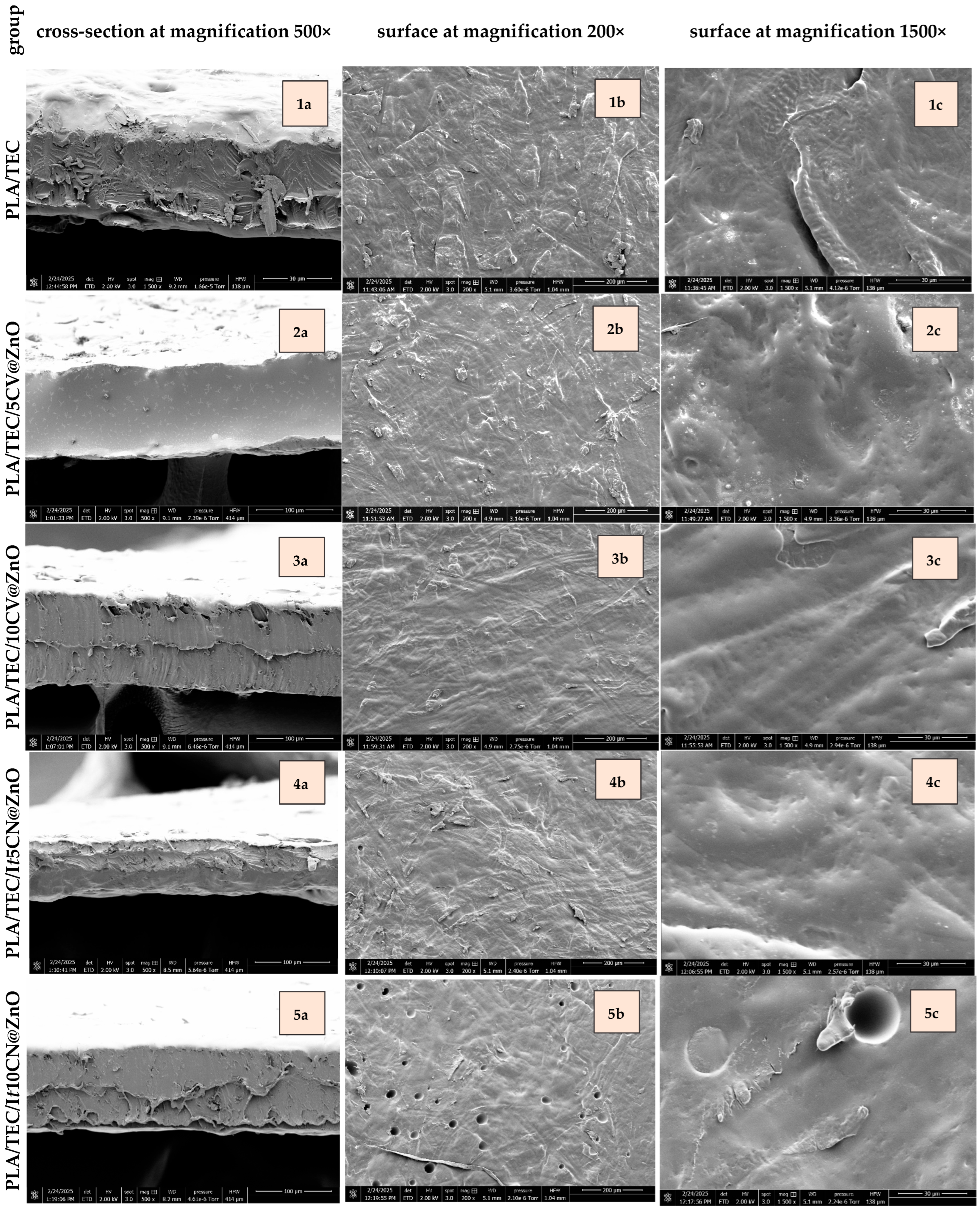

2.2.1. Films’ SEM Images

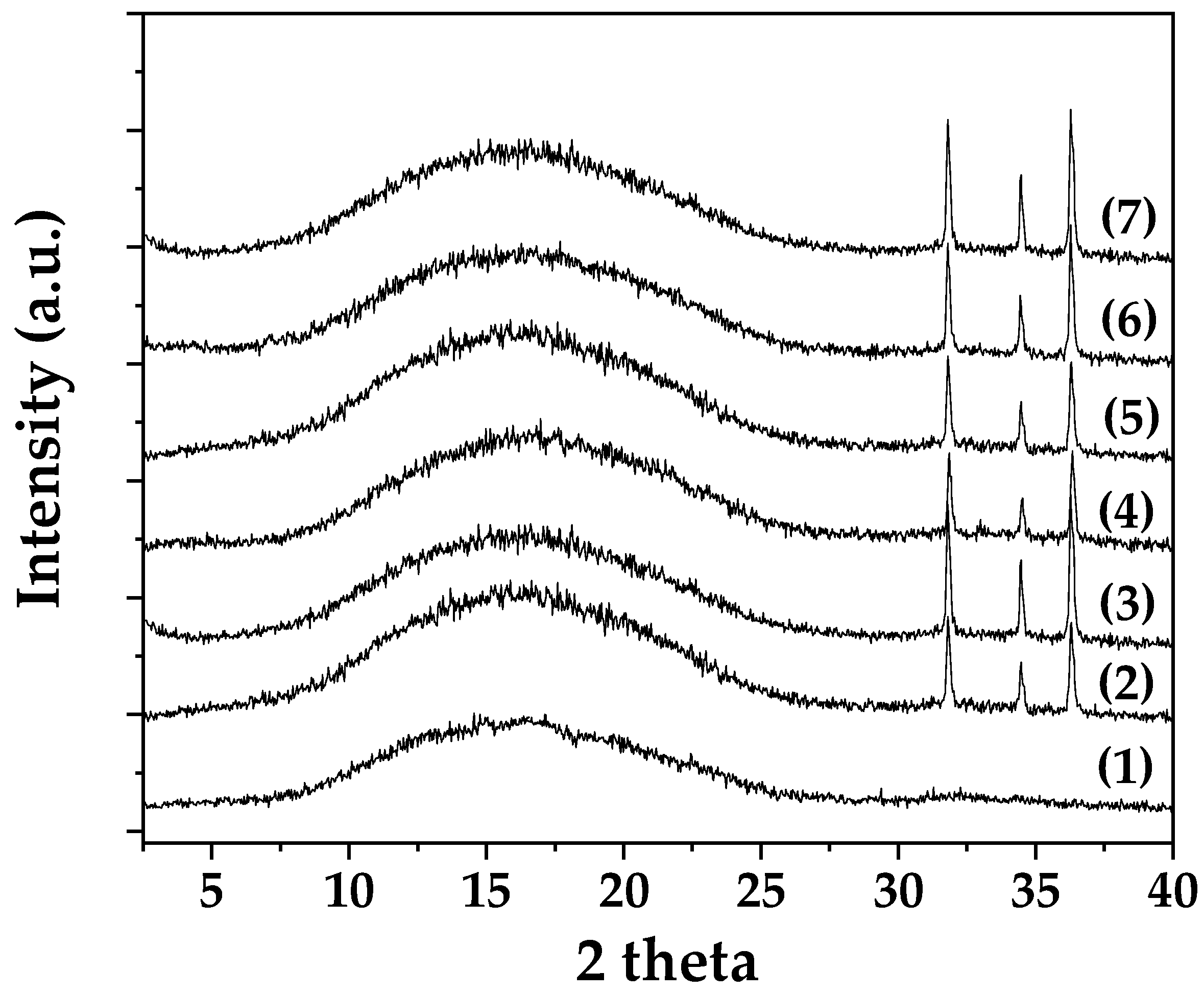

2.2.2. Films’ XRD Analysis

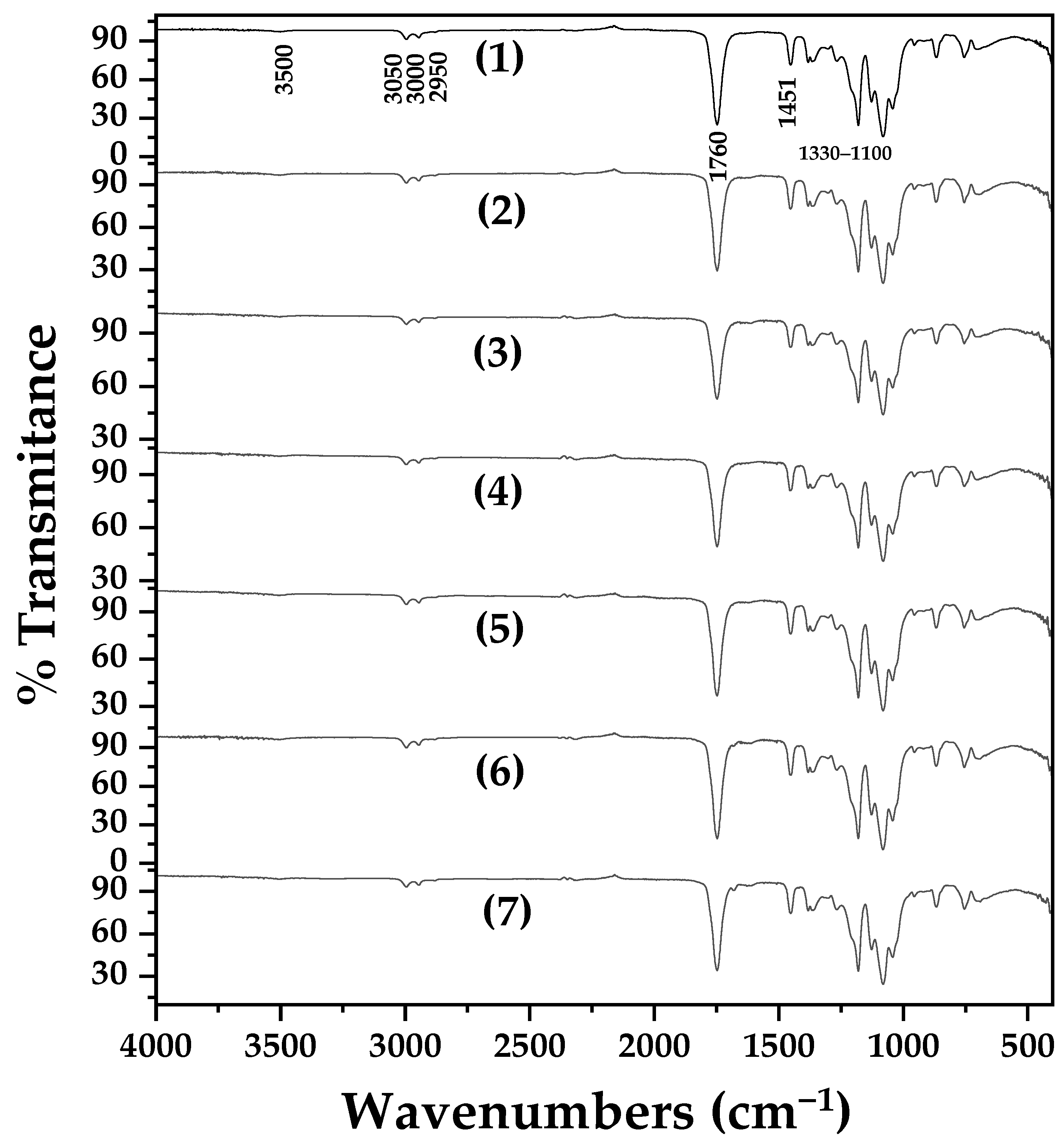

2.2.3. Films’ ATR-FTIR Analysis

2.2.4. Films’ Tensile Properties

2.2.5. Films’ Oxygen Barrier Properties

2.2.6. Films’ Antioxidant Activity

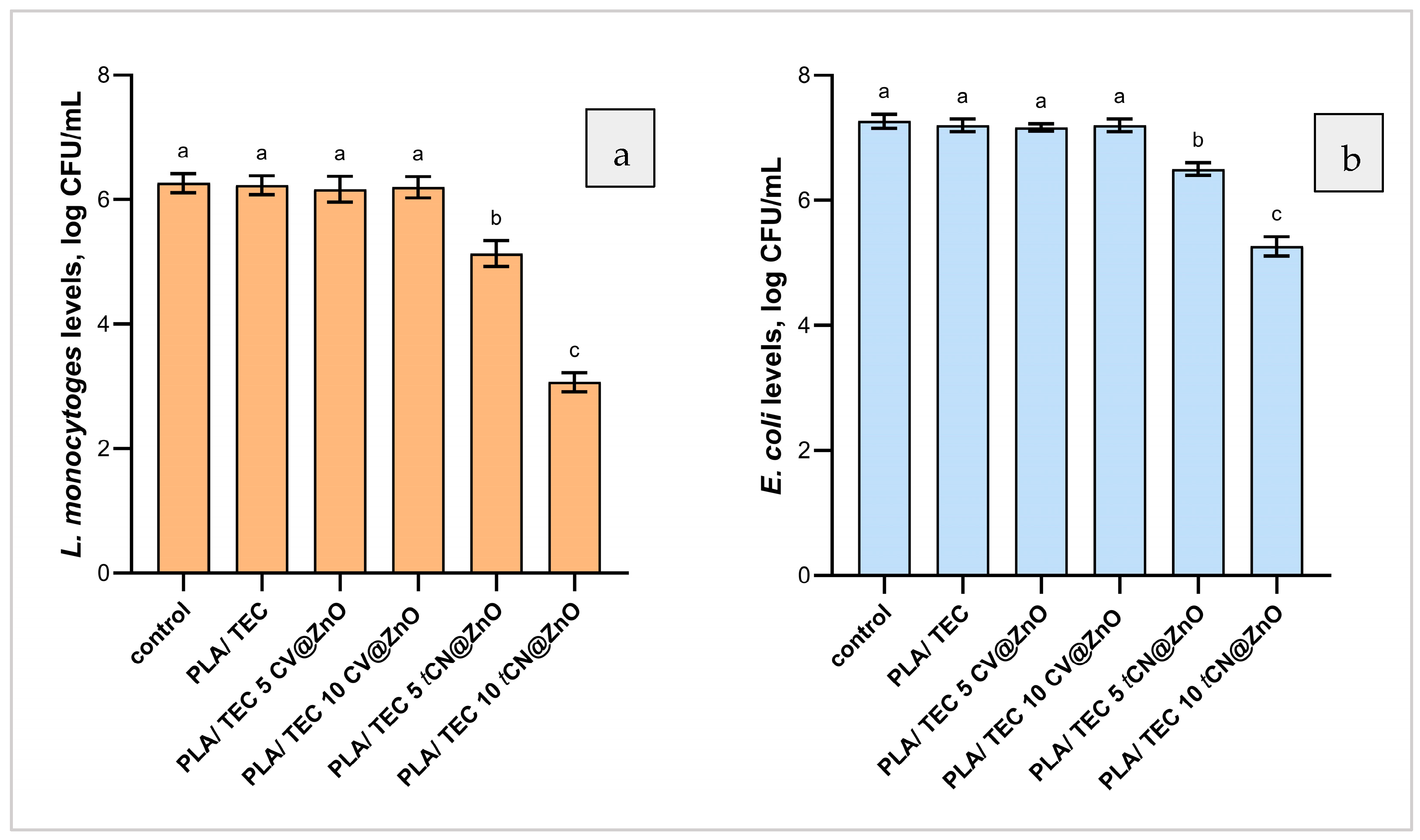

2.2.7. Films’ Antibacterial Activity

2.3. Evaluation of PLA/TEC/10tCN@ZnO Film Efficacy in Preserving Fresh Minced Pork

2.3.1. Lipid Oxidation and Heme Iron Content of Fresh Minced Pork

2.3.2. Total Variable Counts (TVC) of Minced Pork

2.3.3. Total Variable Counts (TVC) of Fresh Minced Pork

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials

4.2. Preparation of ZnO Nanorods

4.3. Preparation of CV@ZnO and tCN@ZnO Nanohybrids

4.4. Preparation of PLA/TEC/xZnO, PLA/TEC/xCV@ZnO, and PLA/TEC/xtCN@ZnO Films

4.5. Physicochemical Characterization of ZnO Nanorods, CV@ZnO and tCN@ZnO Nanohybrids and PLA/TEC/xZnO, PLA/TEC/xCV@ZnO, and PLA/TEC/xtCN@ZnO Films

4.6. Desorption Kinetics of CV@ZnO and tCN@ZnO Nanohybrids

4.7. Antioxidant Activity of ZnO Nanorods, CV@ZnO and tCN@ZnO Nanohybrids and PLA/TEC/xZnO, PLA/TEC/xCV@ZnO, and PLA/TEC/xtCN@ZnO Films

4.8. Antibacterial Activity CV@ZnO, tCN@ZnO Nanohybrids with Well Diffusion Method

4.9. Antimicrobial Effectiveness of PLA/TEC/xZnO, PLA/TEC/xCV@ZnO, and PLA/TEC/xtCN@ZnO Films

4.10. Tensile Properties of PLA/TEC/xZnO, PLA/TEC/xCV@ZnO, and PLA/TEC/xtCN@ZnO Films

4.11. Oxygen Barrier Properties of PLA/TEC/xZnO, PLA/TEC/xCV@ZnO, and PLA/TEC/xtCN@ZnO Films

4.12. Evaluation of Film Efficacy in Preserving Fresh Minced Pork

4.12.1. Meat Packaging and Storage Protocol

4.12.2. Assessment of Lipid Oxidation via TBARS Assay

4.12.3. Determination of Heme Iron Content

4.12.4. Microbiological Analysis: Total Viable Count (TVC)

4.13. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ahmed, W.; Haque, A.; Mohibbullah; Khan, S.I.; Islam, M.A.; Mondal, H.T.; Ahmmed, R. A Review on Active Packaging for Quality and Safety of Foods: Current Trends, Applications, Prospects and Challenges. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2022, 33, 100913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almasi, H.; Jahanbakhsh Oskouie, M.; Saleh, A. A Review on Techniques Utilized for Design of Controlled Release Food Active Packaging. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2021, 61, 2601–2621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azevedo, A.G.; Barros, C.; Miranda, S.; Machado, A.V.; Castro, O.; Silva, B.; Saraiva, M.; Silva, A.S.; Pastrana, L.; Carneiro, O.S.; et al. Active Flexible Films for Food Packaging: A Review. Polymers 2022, 14, 2442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpena, M.; Nuñez-Estevez, B.; Soria-Lopez, A.; Garcia-Oliveira, P.; Prieto, M.A. Essential Oils and Their Application on Active Packaging Systems: A Review. Resources 2021, 10, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chacha, J.S.; Ofoedu, C.E.; Xiao, K. Essential Oil-Based Active Polymer-Based Packaging System: A Review of Its Effect on the Antimicrobial, Antioxidant, and Sensory Properties of Beef and Chicken Meat. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2022, 46, e16933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Luca, S.; Milanese, D.; Gallichi-Nottiani, D.; Cavazza, A.; Sciancalepore, C. Poly(Lactic Acid) and Its Blends for Packaging Application: A Review. Clean Technol. 2023, 5, 1304–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-López, M.E.; Calva-Estrada, S.d.J.; Gradilla-Hernández, M.S.; Barajas-Álvarez, P. Current Trends in Biopolymers for Food Packaging: A Review. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2023, 7, 1225371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cakmak, H.; Sogut, E. Functional Biobased Composite Polymers for Food Packaging Applications. In Reactive and Functional Polymers Volume One: Biopolymers, Polyesters, Polyurethanes, Resins and Silicones; Gutiérrez, T.J., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 95–136. ISBN 978-3-030-43403-8. [Google Scholar]

- González-Arancibia, F.; Mamani, M.; Valdés, C.; Contreras-Matté, C.; Pérez, E.; Aguilera, J.; Rojas, V.; Ramirez-Malule, H.; Andler, R. Biopolymers as Sustainable and Active Packaging Materials: Fundamentals and Mechanisms of Antifungal Activities. Biomolecules 2024, 14, 1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Loughlin, J.; Doherty, D.; Herward, B.; McGleenan, C.; Mahmud, M.; Bhagabati, P.; Boland, A.N.; Freeland, B.; Rochfort, K.D.; Kelleher, S.M.; et al. The Potential of Bio-Based Polylactic Acid (PLA) as an Alternative in Reusable Food Containers: A Review. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swetha, T.A.; Bora, A.; Mohanrasu, K.; Balaji, P.; Raja, R.; Ponnuchamy, K.; Muthusamy, G.; Arun, A. A Comprehensive Review on Polylactic Acid (PLA)—Synthesis, Processing and Application in Food Packaging. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 234, 123715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashfaq, A.; Khursheed, N.; Fatima, S.; Anjum, Z.; Younis, K. Application of Nanotechnology in Food Packaging: Pros and Cons. J. Agric. Food Res. 2022, 7, 100270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Sousa, M.S.; Schlogl, A.E.; Estanislau, F.R.; Souza, V.G.L.; dos Reis Coimbra, J.S.; Santos, I.J.B. Nanotechnology in Packaging for Food Industry: Past, Present, and Future. Coatings 2023, 13, 1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, M. Nanotechnology: A New Approach in Food Packaging. J. Food Microbiol. Saf. Hyg. 2017, 2, 8–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanty, F.; Swain, S.K. Bionanocomposites for Food Packaging Applications. In Nanotechnology Applications in Food: Flavor, Stability, Nutrition and Safety; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2017; pp. 363–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, T.V. Applications of Nanotechnology in Food Packaging and Food Safety: Barrier Materials, Antimicrobials and Sensors. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2011, 363, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Befa Kinki, A.; Atlaw, T.; Haile, T.; Meiso, B.; Belay, D.; Hagos, L.; Hailemichael, F.; Abid, J.; Elawady, A.; Firdous, N. Preservation of Minced Raw Meat Using Rosemary (Rosmarinus Officinalis) and Basil (Ocimum Basilicum) Essential Oils. Cogent Food Agric. 2024, 10, 2306016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Froiio, F.; Mosaddik, A.; Morshed, M.T.; Paolino, D.; Fessi, H.; Elaissari, A. Edible Polymers for Essential Oils Encapsulation: Application in Food Preservation. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2019, 58, 20932–20945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojeda-Piedra, S.A.; Zambrano-Zaragoza, M.L.; González-Reza, R.M.; García-Betanzos, C.I.; Real-Sandoval, S.A.; Quintanar-Guerrero, D. Nano-Encapsulated Essential Oils as a Preservation Strategy for Meat and Meat Products Storage. Molecules 2022, 27, 8187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro-Martínez, A.; López-Gómez, A.; Martínez-Hernández, G.B. Potential of Essential Oils from Active Packaging to Highly Reduce Ethylene Biosynthesis in Broccoli and Apples. ACS Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 1, 1050–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, L.M.; Cruxen, C.E.d.S.; Bruni, G.P.; Fiorentini, Â.M.; Zavareze, E.d.R.; Lim, L.-T.; Dias, A.R.G. Development of Antimicrobial and Antioxidant Electrospun Soluble Potato Starch Nanofibers Loaded with Carvacrol. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 139, 1182–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamimura, J.A.; Santos, E.H.; Hill, L.E.; Gomes, C.L. Antimicrobial and Antioxidant Activities of Carvacrol Microencapsulated in Hydroxypropyl-Beta-Cyclodextrin. LWT—Food Sci. Technol. 2014, 57, 701–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dembińska, K.; Shinde, A.H.; Pejchalová, M.; Richert, A.; Swiontek Brzezinska, M. The Application of Natural Phenolic Substances as Antimicrobial Agents in Agriculture and Food Industry. Foods 2025, 14, 1893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidiropoulou, E.; Marugán-Hernández, V.; Skoufos, I.; Giannenas, I.; Bonos, E.; Aguiar-Martins, K.; Lazari, D.; Papagrigoriou, T.; Fotou, K.; Grigoriadou, K.; et al. In Vitro Antioxidant, Antimicrobial, Anticoccidial, and Anti-Inflammatory Study of Essential Oils of Oregano, Thyme, and Sage from Epirus, Greece. Life 2022, 12, 1783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karabagias, V.K.; Giannakas, A.E.; Andritsos, N.D.; Leontiou, A.A.; Moschovas, D.; Karydis-Messinis, A.; Avgeropoulos, A.; Zafeiropoulos, N.E.; Proestos, C.; Salmas, C.E. Shelf Life of Minced Pork in Vacuum-Adsorbed Carvacrol@Natural Zeolite Nanohybrids and Poly-Lactic Acid/Triethyl Citrate/Carvacrol@Natural Zeolite Self-Healable Active Packaging Films. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karabagias, V.K.; Giannakas, A.E.; Leontiou, A.A.; Karydis-Messinis, A.; Moschovas, D.; Andritsos, N.D.; Avgeropoulos, A.; Zafeiropoulos, N.E.; Proestos, C.; Salmas, C.E. Novel Carvacrol@activated Carbon Nanohybrid for Innovative Poly(Lactide Acid)/Triethyl Citrate Based Sustainable Active Packaging Films. Polymers 2025, 17, 605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaharioudakis, K.; Kollia, E.; Leontiou, A.; Moschovas, D.; Karydis-Messinis, A.; Avgeropoulos, A.; Zafeiropoulos, N.E.; Ragkava, E.; Kehayias, G.; Proestos, C.; et al. Carvacrol Microemulsion vs. Nanoemulsion as Novel Pork Minced Meat Active Coatings. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 3161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaharioudakis, K.; Salmas, C.E.; Andritsos, N.D.; Kollia, E.; Leontiou, A.; Karabagias, V.K.; Karydis-Messinis, A.; Moschovas, D.; Zafeiropoulos, N.E.; Avgeropoulos, A.; et al. Carvacrol, Citral, Eugenol and Cinnamaldehyde Casein Based Edible Nanoemulsions as Novel Sustainable Active Coatings for Fresh Pork Tenderloin Meat Preservation. Front. Food. Sci. Technol. 2024, 4, 1400224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaharioudakis, K.; Salmas, C.E.; Andritsos, N.D.; Leontiou, A.A.; Moschovas, D.; Karydis-Messinis, A.; Triantafyllou, E.; Avgeropoulos, A.; Zafeiropoulos, N.E.; Proestos, C.; et al. Investigating the Synergistic Effects of Carvacrol and Citral-Edible Polysaccharide-Based Nanoemulgels on Shelf Life Extension of Chalkidiki Green Table Olives. Gels 2024, 10, 722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alkan Tas, B.; Sehit, E.; Erdinc Tas, C.; Unal, S.; Cebeci, F.C.; Menceloglu, Y.Z.; Unal, H. Carvacrol Loaded Halloysite Coatings for Antimicrobial Food Packaging Applications. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2019, 20, 100300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, J.; Dwibedi, V.; Huang, H.; Ge, Y.; Li, Y.; Li, Q.; Sun, T. Preparation and Antibacterial Mechanism of Cinnamaldehyde/Tea Polyphenol/Polylactic Acid Coaxial Nanofiber Films with Zinc Oxide Sol to Shewanella putrefaciens. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 237, 123932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, C.; Ge, L.; Li, Z.; Chen, B.; Liao, S.; Lu, L.; Wu, Q.; Jiang, X.; An, Y.; Wang, Z.; et al. Antibacterial Activity of Cinnamon Essential Oil and Its Main Component of Cinnamaldehyde and the Underlying Mechanism. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1378434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaramillo Jimenez, B.A.; Awwad, F.; Desgagné-Penix, I. Cinnamaldehyde in Focus: Antimicrobial Properties, Biosynthetic Pathway, and Industrial Applications. Antibiotics 2024, 13, 1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usai, F.; Di Sotto, A. Trans-Cinnamaldehyde as a Novel Candidate to Overcome Bacterial Resistance: An Overview of In Vitro Studies. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nasution, H.; Harahap, H.; Julianti, E.; Safitri, A.; Jaafar, M. Properties of Active Packaging of PLA-PCL Film Integrated with Chitosan as an Antibacterial Agent and Syzygium cumini Seed Extract as an Antioxidant Agent. Heliyon 2024, 10, e23952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiore, A.; Park, S.; Volpe, S.; Torrieri, E.; Masi, P. Active Packaging Based on PLA and Chitosan-Caseinate Enriched Rosemary Essential Oil Coating for Fresh Minced Chicken Breast Application. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2021, 29, 100708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Mao, L.; Yao, J.; Zhu, H. Improving the Active Food Packaging Function of Poly(Lactic Acid) Film Coated by Poly(Vinyl Alcohol) Based on Proanthocyanidin Functionalized Layered Clay. LWT 2023, 174, 114407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karabagias, V.K.; Giannakas, A.E.; Andritsos, N.D.; Moschovas, D.; Karydis-Messinis, A.; Leontiou, A.; Avgeropoulos, A.; Zafeiropoulos, N.E.; Proestos, C.; Salmas, C.E. Νovel Polylactic Acid/Tetraethyl Citrate Self-Healable Active Packaging Films Applied to Pork Fillets’ Shelf-Life Extension. Polymers 2024, 16, 1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virág, L.; Bocsi, R.; Pethő, D. Adsorption Properties of Essential Oils on Polylactic Acid Microparticles of Different Sizes. Materials 2022, 15, 6602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Javidi, Z.; Hosseini, S.F.; Rezaei, M. Development of Flexible Bactericidal Films Based on Poly(Lactic Acid) and Essential Oil and Its Effectiveness to Reduce Microbial Growth of Refrigerated Rainbow Trout. LWT—Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 72, 251–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llana-Ruiz-Cabello, M.; Pichardo, S.; Bermúdez, J.M.; Baños, A.; Núñez, C.; Guillamón, E.; Aucejo, S.; Cameán, A.M. Development of PLA Films Containing Oregano Essential Oil (Origanum vulgare L. Virens) Intended for Use in Food Packaging. Food Addit. Contam. Part A 2016, 33, 1374–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, J.; Mulla, M.Z.; Arfat, Y.A. Thermo-Mechanical, Structural Characterization and Antibacterial Performance of Solvent Casted Polylactide/Cinnamon Oil Composite Films. Food Control 2016, 69, 196–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Sani, M.A.; Zhang, Z.; McClements, D.J.; Jafari, S.M. High Performance Biopolymeric Packaging Films Containing Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles for Fresh Food Preservation: A Review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 230, 123188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dejene, B.K.; Abtew, M.A. Chitosan/Zinc Oxide (ZnO) Nanocomposites: A Critical Review of Emerging Multifunctional Applications in Food Preservation and Biomedical Systems. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 316, 144773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vyas, A.; Ng, S.; Fu, T.; Anum, I. ZnO-Embedded Carboxymethyl Cellulose Bioplastic Film Synthesized from Sugarcane Bagasse for Packaging Applications. Polymers 2025, 17, 579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buntinx, M.; Vanheusden, C.; Hermans, D. Processing and Properties of Polyhydroxyalkanoate/ZnO Nanocomposites: A Review of Their Potential as Sustainable Packaging Materials. Polymers 2024, 16, 3061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, J.; Wang, T.; Liu, L.-Z.; Tian, C.; Cui, Y.; Shao, W.; Hua, X.; Shi, Y.; Wang, Y. Antibacterial Properties and Mechanism of Nanometer Zinc Oxide Composites. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2023, 40, 101167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes, C.R.; Dilarri, G.; Forsan, C.F.; Sapata, V.d.M.R.; Lopes, P.R.M.; de Moraes, P.B.; Montagnolli, R.N.; Ferreira, H.; Bidoia, E.D. Antibacterial Action and Target Mechanisms of Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles against Bacterial Pathogens. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 2658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeon, Y.-R.; Yu, J.; Choi, S.-J. Fate Determination of ZnO in Commercial Foods and Human Intestinal Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, Z.; Zhao, T.; Li, L.; Fan, J.; Qin, Y. Characterization of Antimicrobial Poly (Lactic Acid)/Nano-Composite Films with Silver and Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles. Materials 2017, 10, 659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murariu, M.; Benali, S.; Paint, Y.; Dechief, A.-L.; Murariu, O.; Raquez, J.-M.; Dubois, P. Adding Value in Production of Multifunctional Polylactide (PLA)–ZnO Nanocomposite Films through Alternative Manufacturing Methods. Molecules 2021, 26, 2043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jayaramudu, J.; Das, K.; Sonakshi, M.; Siva Mohan Reddy, G.; Aderibigbe, B.; Sadiku, R.; Sinha Ray, S. Structure and Properties of Highly Toughened Biodegradable Polylactide/ZnO Biocomposite Films. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2014, 64, 428–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, I.; Viswanathan, K.; Kasi, G.; Sadeghi, K.; Thanakkasaranee, S.; Seo, J. Poly(Lactic Acid)/ZnO Bionanocomposite Films with Positively Charged ZnO as Potential Antimicrobial Food Packaging Materials. Polymers 2019, 11, 1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeżo, A.; Poohphajai, F.; Herrera Diaz, R.; Kowaluk, G. Incorporation of Nano-Zinc Oxide as a Strategy to Improve the Barrier Properties of Biopolymer–Suberinic Acid Residues Films: A Preliminary Study. Materials 2024, 17, 3868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Lan, W.; Ji, T.; Sameen, D.E.; Ahmed, S.; Qin, W.; Liu, Y. Development of Polylactic Acid/ZnO Composite Membranes Prepared by Ultrasonication and Electrospinning for Food Packaging. LWT 2021, 135, 110072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Zhou, Z.; Yang, J.; Zhang, M.; Cai, F.; Lu, P. ZnO Nanoparticles Stabilized Oregano Essential Oil Pickering Emulsion for Functional Cellulose Nanofibrils Packaging Films with Antimicrobial and Antioxidant Activity. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 190, 433–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Motelica, L.; Ficai, D.; Oprea, O.; Ficai, A.; Trusca, R.-D.; Andronescu, E.; Holban, A.M. Biodegradable Alginate Films with ZnO Nanoparticles and Citronella Essential Oil—A Novel Antimicrobial Structure. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasti, T.; Dixit, S.; Hiremani, V.D.; Chougale, R.B.; Masti, S.P.; Vootla, S.K.; Mudigoudra, B.S. Chitosan/Pullulan Based Films Incorporated with Clove Essential Oil Loaded Chitosan-ZnO Hybrid Nanoparticles for Active Food Packaging. Carbohydr. Polym. 2022, 277, 118866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alizadeh-Sani, M.; Moghaddas Kia, E.; Ghasempour, Z.; Ehsani, A. Preparation of Active Nanocomposite Film Consisting of Sodium Caseinate, ZnO Nanoparticles and Rosemary Essential Oil for Food Packaging Applications. J. Polym. Environ. 2021, 29, 588–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heydari-Majd, M.; Ghanbarzadeh, B.; Shahidi-Noghabi, M.; Abdolshahi, A.; Dahmardeh, S.; Malek Mohammadi, M. Poly(Lactic Acid)-Based Bionanocomposites: Effects of ZnO Nanoparticles and Essential Oils on Physicochemical Properties. Polym. Bull. 2022, 79, 97–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heydari-Majd, M.; Ghanbarzadeh, B.; Shahidi-Noghabi, M.; Najafi, M.A.; Hosseini, M. A New Active Nanocomposite Film Based on PLA/ZnO Nanoparticle/Essential Oils for the Preservation of Refrigerated Otolithes ruber Fillets. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2019, 19, 94–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.; Chen, L.; Liu, T.; Liu, M.; Yang, Y.; Liu, G.; Zhao, H.; Chen, P.; Fu, S.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Poly-(Lactic Acid) Composite Films Comprising Carvacrol and Cellulose Nanocrystal–Zinc Oxide with Synergistic Antibacterial Effects. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 266, 130937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, L.H.; Trigueiro, P.; Souza, J.S.N.; de Carvalho, M.S.; Osajima, J.A.; da Silva-Filho, E.C.; Fonseca, M.G. Montmorillonite with Essential Oils as Antimicrobial Agents, Packaging, Repellents, and Insecticides: An Overview. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2022, 209, 112186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannakas, A.; Tsagkalias, I.; Achilias, D.S.; Ladavos, A. A Novel Method for the Preparation of Inorganic and Organo-Modified Montmorillonite Essential Oil Hybrids. Appl. Clay Sci. 2017, 146, 362–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannakas, A.E.; Salmas, C.E.; Leontiou, A.; Moschovas, D.; Baikousi, M.; Kollia, E.; Tsigkou, V.; Karakassides, A.; Avgeropoulos, A.; Proestos, C. Performance of Thyme Oil@Na-Montmorillonite and Thyme Oil@Organo-Modified Montmorillonite Nanostructures on the Development of Melt-Extruded Poly-L-Lactic Acid Antioxidant Active Packaging Films. Molecules 2022, 27, 1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giannakas, A.E.; Baikousi, M.; Karabagias, V.K.; Karageorgou, I.; Iordanidis, G.; Emmanouil-Konstantinos, C.; Leontiou, A.; Karydis-Messinis, A.; Zafeiropoulos, N.E.; Kehayias, G.; et al. Low-Density Polyethylene-Based Novel Active Packaging Film for Food Shelf-Life Extension via Thyme-Oil Control Release from SBA-15 Nanocarrier. Nanomaterials 2024, 14, 423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannakas, A. Na-Montmorillonite Vs. Organically Modified Montmorillonite as Essential Oil Nanocarriers for Melt-Extruded Low-Density Poly-Ethylene Nanocomposite Active Packaging Films with a Controllable and Long-Life Antioxidant Activity. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannakas, A.E.; Salmas, C.E.; Moschovas, D.; Zaharioudakis, K.; Georgopoulos, S.; Asimakopoulos, G.; Aktypis, A.; Proestos, C.; Karakassides, A.; Avgeropoulos, A.; et al. The Increase of Soft Cheese Shelf-Life Packaged with Edible Films Based on Novel Hybrid Nanostructures. Gels 2022, 8, 539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salmas, C.E.; Giannakas, A.E.; Karabagias, V.K.; Moschovas, D.; Karabagias, I.K.; Gioti, C.; Georgopoulos, S.; Leontiou, A.; Kehayias, G.; Avgeropoulos, A.; et al. Development and Evaluation of a Novel-Thymol@Natural-Zeolite/Low-Density-Polyethylene Active Packaging Film: Applications for Pork Fillets Preservation. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmas, C.; Giannakas, A.; Katapodis, P.; Leontiou, A.; Moschovas, D.; Karydis-Messinis, A. Development of ZnO/Na-Montmorillonite Hybrid Nanostructures Used for PVOH/ZnO/Na-Montmorillonite Active Packaging Films Preparation via a Melt-Extrusion Process. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsu, H.-C.; Cheng, C.-S.; Chang, C.-C.; Yang, S.; Chang, C.-S.; Hsieh, W.-F. Orientation-Enhanced Growth and Optical Properties of ZnO Nanowires Grown on Porous Silicon Substrates. Nanotechnology 2005, 16, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, A.A.; Geioushy, R.A.; Bouzid, H.; Al-Sayari, S.A.; Al-Hajry, A.; Bahnemann, D.W. TiO2 Decoration of Graphene Layers for Highly Efficient Photocatalyst: Impact of Calcination at Different Gas Atmosphere on Photocatalytic Efficiency. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2013, 129, 62–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cullity, B.D.; Stock, S.R. Elements of X-Ray Diffraction, 3rd ed.; Prentice-Hall: New York, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- de Souza, A.G.; dos Santos, N.M.A.; da Silva Torin, R.F.; dos Santos Rosa, D. Synergic Antimicrobial Properties of Carvacrol Essential Oil and Montmorillonite in Biodegradable Starch Films. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 164, 1737–1747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valderrama, A.C.S.; De, G.C.R. Traceability of Active Compounds of Essential Oils in Antimicrobial Food Packaging Using a Chemometric Method by ATR-FTIR. Am. J. Anal. Chem. 2017, 8, 726–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jailani, A.; Kalimuthu, S.; Rajasekar, V.; Ghosh, S.; Collart-Dutilleul, P.-Y.; Fatima, N.; Koo, H.; Solomon, A.P.; Cuisinier, F.; Neelakantan, P. Trans-Cinnamaldehyde Eluting Porous Silicon Microparticles Mitigate Cariogenic Biofilms. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Bayati, F.A.; Mohammed, M.J. Isolation, Identification, and Purification of Cinnamaldehyde from Cinnamomum Zeylanicum Bark Oil. An Antibacterial Study. Pharm. Biol. 2009, 47, 61–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannakas, A.E.; Salmas, C.E.; Moschovas, D.; Baikousi, M.; Kollia, E.; Tsigkou, V.; Karakassides, A.; Leontiou, A.; Kehayias, G.; Avgeropoulos, A.; et al. Nanocomposite Film Development Based on Chitosan/Polyvinyl Alcohol Using ZnO@Montmorillonite and ZnO@Halloysite Hybrid Nanostructures for Active Food Packaging Applications. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 1843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelghani, G.M.; Ahmed, A.B.; Al-Zubaidi, A.B. Synthesis, Characterization, and the Influence of Energy of Irradiation on Optical Properties of ZnO Nanostructures. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 20016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albarakaty, F.M.; Alzaban, M.I.; Alharbi, N.K.; Bagrwan, F.S.; El-Aziz, A.R.M.A.; Mahmoud, M.A. Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles, Biosynthesis, Characterization and Their Potent Photocatalytic Degradation, and Antioxidant Activities. J. King Saud Univ. Sci. 2022, 35, 102434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lal, M.; Sharma, P.; Singh, L.; Ram, C. Photocatalytic Degradation of Hazardous Rhodamine B Dye Using Sol-Gel Mediated Ultrasonic Hydrothermal Synthesized of ZnO Nanoparticles. Results Eng. 2023, 17, 100890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benbettaieb, N.; Nyagaya, J.; Seuvre, A.-M.; Debeaufort, F. Antioxidant Activity and Release Kinetics of Caffeic and P-Coumaric Acids from Hydrocolloid-Based Active Films for Healthy Packaged Food. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2018, 66, 6906–6916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lüth, H.; Rubloff, G.W.; Grobman, W.D. Chemisorption of Organic Molecules on ZnO(11̄00) Surfaces: C5H5N, (CH3)2CO, and (CH3)2SO. Surf. Sci. 1978, 74, 365–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, S.P.; Swain, S.; Sa, N.; Pilla, S.N.; Behera, A.; Sahu, P.K.; Chandra Si, S. Photocatalysis of Environmental Organic Pollutants and Antioxidant Activity of Flavonoid Conjugated Gold Nanoparticles. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2022, 282, 121699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adebayo, E.A.; Oke, M.A.; Aina, D.A.; Afolabi, F.J.; Ibikunle, J.B.; Adetayo, M.O. Antioxidant Potential of the Biosynthesized Silver, Gold and Silver-Gold Alloy Nanoparticles Using Opuntia Ficus-Indica Extract. Fountain J. Nat. Appl. Sci. 2021, 10, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, N.-Y.; Trinh, N.-T.; Ahn, S.-G.; Kim, S.-A. Cinnamaldehyde Protects against Oxidative Stress and Inhibits the TNF-α-Induced Inflammatory Response in Human Umbilical Vein Endothelial Cells. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2020, 46, 449–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariestiani, B.; Fachriyah, E.; Nurani, K. Antioxidant Activity from Encapsulated Cinnamaldehyde-Chitosan. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2018, 1025, 012132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vielkind, M.; Kampen, I.; Kwade, A. Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles in Bacterial Growth Medium: Optimized Dispersion and Growth Inhibition of Pseudomonas Putida. Adv. Nanopart. 2013, 2, 287–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinelli, L.; Di Stefano, A.; Cacciatore, I. Carvacrol and Its Derivatives as Antibacterial Agents. Phytochem. Rev. 2018, 17, 903–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doyle, A.A.; Stephens, J.C. A Review of Cinnamaldehyde and Its Derivatives as Antibacterial Agents. Fitoterapia 2019, 139, 104405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, L.; Baruzzi, F.; Terzano, R.; Busto, F.; Marzulli, A.; Magno, C.; Cometa, S.; De Giglio, E. Analytical and Antimicrobial Characterization of Zn-Modified Clays Embedding Thymol or Carvacrol. Molecules 2024, 29, 3607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jovanović, J.; Ćirković, J.; Radojković, A.; Tasić, N.; Mutavdžić, D.; Branković, G.; Branković, Z. Enhanced Stability of Encapsulated Lemongrass Essential Oil in Chitosan-Gelatin and Pectin-Gelatin Biopolymer Matrices Containing ZnO Nanoparticles. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 275, 133335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Windiasti, G.; Feng, J.; Ma, L.; Hu, Y.; Hakeem, M.J.; Amoako, K.; Delaquis, P.; Lu, X. Investigating the Synergistic Antimicrobial Effect of Carvacrol and Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles against Campylobacter jejuni. Food Control 2019, 96, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-González, L.; Chiralt, A.; González-Martínez, C.; Cháfer, M. Effect of Essential Oils on Properties of Film Forming Emulsions and Films Based on Hydroxypropylmethylcellulose and Chitosan. J. Food Eng. 2011, 105, 246–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Zuo, Y. Relationship between Porosity, Pore Parameters and Properties of Microarc Oxidation Film on AZ91D Magnesium Alloy. Results Phys. 2019, 12, 2044–2054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cama, E.S.; Pasini, M.; Giovanella, U.; Galeotti, F. Crack-Templated Patterns in Thin Films: Fabrication Techniques, Characterization, and Emerging Applications. Coatings 2025, 15, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonilla, J.; Atarés, L.; Vargas, M.; Chiralt, A. Effect of Essential Oils and Homogenization Conditions on Properties of Chitosan-Based Films. Food Hydrocoll. 2012, 26, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera, N.; Singh, A.A.; Salaberria, A.M.; Labidi, J.; Mathew, A.P.; Oksman, K. Triethyl Citrate (TEC) as a Dispersing Aid in Polylactic Acid/Chitin Nanocomposites Prepared via Liquid-Assisted Extrusion. Polymers 2017, 9, 406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, D.; Wu, L.; Zhang, M.; Zhao, Y. Viscoelasticity and Thermal Stability of Polylactide Composites with Various Functionalized Carbon Nanotubes. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2008, 93, 1577–1584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, M.; Jiménez, A.; Peltzer, M.; Garrigós, M.C. Characterization and Antimicrobial Activity Studies of Polypropylene Films with Carvacrol and Thymol for Active Packaging. J. Food Eng. 2012, 109, 513–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murariu, M.; Dubois, P. PLA Composites: From Production to Properties. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2016, 107, 17–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devi, L.S.; Krishnan, R.; Begum, S.; Nath, D.; Mohanty, A.; Misra, M.; Kumar, S. Curcumin as Bioactive Agent in Active and Intelligent Food Packaging Systems: A Comprehensive Review. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2025, 24, e70228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostenko, M.; Stetsyshyn, Y.; Harhay, K.; Melnyk, Y.; Donchak, V.; Khomyak, S.; Ivanukh, O.; Kracalik, M. Impact of the Functionalized Clay on the Poly(Lactic Acid)/Polybutylene Adipate Terephthalate (PLA/PBAT) Based Biodegradable Nanocomposites: Thermal and Rheological Properties. Appl. Clay Sci. 2025, 278, 108020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, L.E. Models for the Permeability of Filled Polymer Systems. J. Macromol. Sci. Part A—Chem. 1967, 1, 929–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudalakis, G.; Gotsis, A.D. Permeability of Polymer/Clay Nanocomposites: A Review. Eur. Polym. J. 2009, 45, 967–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armentano, I.; Fortunati, E.; Burgos, N.; Dominici, F.; Luzi, F.; Fiori, S.; Jimenez, A.; Yoon, K.; Ahn, J.; Kang, S.; et al. Processing and Characterization of Plasticized PLA/PHB Blends for Biodegradable Multiphase Systems. Express Polym. Lett. 2015, 9, 583–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muriel-Galet, V.; López-Carballo, G.; Hernández-Muñoz, P.; Gavara, R. Characterization of Ethylene-Vinyl Alcohol Copolymer Containing Lauril Arginate (LAE) as Material for Active Antimicrobial Food Packaging. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2014, 1, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siracusa, V.; Rocculi, P.; Romani, S.; Rosa, M.D. Biodegradable Polymers for Food Packaging: A Review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2008, 19, 634–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuorwel, K.K.; Cran, M.J.; Orbell, J.D.; Buddhadasa, S.; Bigger, S.W. Review of Mechanical Properties, Migration, and Potential Applications in Active Food Packaging Systems Containing Nanoclays and Nanosilver. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2015, 14, 411–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastarrachea, L.J.; Wong, D.E.; Roman, M.J.; Lin, Z.; Goddard, J.M. Active Packaging Coatings. Coatings 2015, 5, 771–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Effect of Bacteriophages Against Biofilms of Escherichia Coli on Food Processing Surfaces. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/2076-2607/12/2/366 (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- Fliss, O.; Fliss, I.; Biron, E. Bioprotective Strategies to Control Listeria monocytogenes in Food Products and Processing Environments. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 10481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashrafudoulla, M.; Mizan, M.F.R.; Park, S.H.; Ha, S.-D. Antibiofilm Activity of Carvacrol against Listeria monocytogenes and Pseudomonas aeruginosa Biofilm on MBECTM Biofilm Device and Polypropylene Surface. LWT 2021, 147, 111575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arancibia, M.; Giménez, B.; López-Caballero, M.E.; Gómez-Guillén, M.C.; Montero, P. Release of Cinnamon Essential Oil from Polysaccharide Bilayer Films and Its Use for Microbial Growth Inhibition in Chilled Shrimps. LWT—Food Sci. Technol. 2014, 59, 989–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somrani, M.; Inglés, M.-C.; Debbabi, H.; Abidi, F.; Palop, A. Garlic, Onion, and Cinnamon Essential Oil Anti-Biofilms’ Effect against Listeria Monocytogenes. Foods 2020, 9, 567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shankar, S.; Teng, X.; Li, G.; Rhim, J.-W. Preparation, Characterization, and Antimicrobial Activity of Gelatin/ZnO Nanocomposite Films. Food Hydrocoll. 2015, 45, 264–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosavinia, S.Z.; Mousavi, S.M.; Khodanazary, A.; Hosseini, S.M. Effect of a Chitosan-Based Nanocomposite Containing ZnO and Zataria Multiflora Essential Oil on Quality Properties of Asian Sea Bass (Lates calcarifer) Fillet. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 59, 869–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montaño-Sánchez, E.; Torres-Martínez, B.d.M.; Vargas-Sánchez, R.D.; Huerta-Leidenz, N.; Sánchez-Escalante, A.; Beriain, M.J.; Torrescano-Urrutia, G.R. Effects of Chitosan Coating with Green Tea Aqueous Extract on Lipid Oxidation and Microbial Growth in Pork Chops during Chilled Storage. Foods 2020, 9, 766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, W.; Dang, S.; Liu, H.; Zhang, Z.; Yu, C.; Liu, X.; Xu, B. Evidence of the Formation Mechanism of ZnO in Aqueous Solution. Mater. Lett. 2012, 82, 99–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannakas, A.E. 7—Extrusion of Biopolymers for Food Applications. In Advances in Biopolymers for Food Science and Technology; Pal, K., Sarkar, P., Cerqueira, M.Â., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2024; pp. 137–169. ISBN 978-0-443-19005-6. [Google Scholar]

- Saleh, T.A. Chapter 3—Kinetic Models and Thermodynamics of Adsorption Processes: Classification. In Interface Science and Technology; Surface Science of Adsorbents and Nanoadsorbents; Saleh, T.A., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; Volume 34, pp. 65–97. [Google Scholar]

- Zeitschrift Für Physik A Hadrons and Nuclei. Available online: https://link.springer.com/journal/218/volumes-and-issues (accessed on 17 September 2025).

- Turalija, M.; Bischof, S.; Budimir, A.; Gaan, S. Antimicrobial PLA Films from Environment Friendly Additives. Compos. Part B Eng. 2016, 102, 94–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardjoum, N.; Chibani, N.; Shankar, S.; Fadhel, Y.B.; Djidjelli, H.; Lacroix, M. Development of Antimicrobial Films Based on Poly(Lactic Acid) Incorporated with Thymus vulgaris Essential Oil and Ethanolic Extract of Mediterranean Propolis. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 185, 535–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salmas, C.E.; Giannakas, A.E.; Baikousi, M.; Kollia, E.; Tsigkou, V.; Proestos, C. Effect of Copper and Titanium-Exchanged Montmorillonite Nanostructures on the Packaging Performance of Chitosan/Poly-Vinyl-Alcohol-Based Active Packaging Nanocomposite Films. Foods 2021, 10, 3038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarladgis, B.G.; Watts, B.M.; Younathan, M.T.; Dugan, L. A Distillation Method for the Quantitative Determination of Malonaldehyde in Rancid Foods. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 1960, 37, 44–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, E.M.; Mahoney, A.W.; Carpenter, C.E. Heme and Total Iron in Ready-to-Eat Chicken. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1997, 45, 124–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample Code Name | %wt. Adsorbed CV or tCN | k2,average | qe,average | EC50,DPPH (mg/mL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CV@ZnO | 49.9 ± 0.1 | 3.59 × 10−4 ± 0.14 × 10−4 | 0.98 ± 0.01 | 4.66 ± 0.68 |

| tCN@ZnO | 50.1 ± 0.03 | 8.25 × 10−5 ± 0.33 × 10−5 | 0.83 ± 0.03 | 33.33 ± 5.72 |

| Food Pathogen | ZnO * | CV@ZnO | tCN@ZnO | CV | tCN |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S. enterica | 0.00 a | 8.00 ± 0.80 a,b | 3.50 ± 0.70 a,b,c | 7.00 ± 0.14 a,b,c | 8.00 ± 0.14 a,c |

| L. monocytogenes | 0.00 d | 5.00 ± 0.14 d,e | 2.50 ± 0.50 d,e,f | 10.5 ± 0.21 d,e,f | 10.00 ± 1.40 d,e |

| S. aureus | 0.00 h | 5.00 ± 0.14 h,i | 2.30 ± 0.20 h,i,j | 6.00 ± 0.14 h,i,j | 8.50 ± 0.85 h,i |

| E. coli | 0.00 k | 4.00 ± 0.14 k,l | 5.00 ± 0.50 k,l,m | 7.00 ± 0.70 k,l,m | 8.00 ± 1.40 k,l |

| Sample | E (MPa) | σuts (MPa) | %ε |

|---|---|---|---|

| PLA/TEC | 594.0 c,d ± 76.1 | 20.0 c ± 3.5 | 156.7 a ± 25.2 |

| PLA/TEC/5ZnO | 811.2 c ± 67.5 | 30.7 b ± 2.3 | 7.3 b ± 2.1 |

| PLA/TEC/10ZnO | 590.4 c,d ± 81.2 | 20.0 c ± 1.7 | 200.0 a ± 43.6 |

| PLA/TEC/5CV@ZnO | 1125.7 b ± 74.5 | 34.3 b ± 5.5 | 28.3 b ± 7.3 |

| PLA/TEC/10CVZnO | 510.5 d ± 85.1 | 18.7 c ± 4.0 | 230.7 a ± 78.0 |

| PLA/TEC/5tCN@ZnO | 1354.8 a ± 110.4 | 60.0 a ± 1.7 | 4.3 b ± 0.5 |

| PLA/TEC/10tCN@ZnO | 745.4 c ± 45.9 | 26.0 b,c ± 2.8 | 50.5 b ± 16.0 |

| Sample | Thickness (mm) | OTR (mL·m−2·day−1) | PeO2 (cm2·s−1) × 10−9 | EC50,DPPH mg/mL |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PLA/TEC | 0.23 a,b ± 0.01 | 196 a ± 5 | 5.21 × 10−9 a ± 1.33 × 10−10 | - |

| PLA/TEC/5ZnO | 0.24 a ± 0.01 | 180 b ± 5 | 5.00 × 10−9 a ± 1.38 × 10−10 | 363.4 a ± 36.8 |

| PLA/TEC/10ZnO | 0.21 b,c ± 0.01 | 30 e ± 2 | 7.29 × 10−10 e ± 4.86 × 10−11 | 222.8 b ± 37.4 |

| PLA/TEC/5CV@ZnO | 0.20 c ± 0.01 | 60 d ± 3 | 1.38 × 10−9 d ± 6.94 × 10−11 | 75.2 d ± 2.0 |

| PLA/TEC/10CV@ZnO | 0.19 c ± 0.01 | 190 a,b ± 5 | 4.17 × 10−9 b ± 1.09 × 10−10 | 54.4 d ± 9.0 |

| PLA/TEC/5tCN@ZnO | 0.21 b,c ± 0.01 | 120 c ± 5 | 2.91 × 10−9 c ± 1.21 × 10−10 | 122.2 c ± 17.1 |

| PLA/TEC/10tCN@ZnO | 0.20 c ± 0.01 | 192 a,b ± 5 | 4.44 × 10−9 b ± 1.16 × 10−10 | 48.2 d ± 14.5 |

| Sample Code | Day 0 | Day 2 | Day 4 | Day 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TBARS (mg/kg) | ||||

| CONTROL | 0.42 ± 0.01 | 0.60 ± 0.02 | 0.74± 0.02 | 0.83 ± 0.02 |

| PLA/TEC/10tCN@ZnO | 0.42 ± 0.01 | 0.56 ± 0.01 | 0.67 ± 0.01 | 0.77 ± 0.01 |

| Heme iron (μg/g) | ||||

| CONTROL | 7.64 ± 0.12 | 6.24 ± 0.36 | 5.50 ± 0.18 | 4.65 ± 0.33 |

| PLA/TEC/10tCN@ZnO | 7.64 ± 0.12 | 7.14 ± 0.12 | 6.15 ± 0.21 | 5.22 ± 0.27 |

| Sample Code | logCFU/g | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day 0 | Day 2 | Day 4 | Day 6 | |

| CONTROL | 4.32 ± 0.03 | 5.59 ± 0.13 | 6.79 ± 0.06 | 8.14 ± 0.01 |

| PLA/TEC/10tCN@ZnO | 4.32 ± 0.03 | 5.01 ± 0.04 | 6.32 ± 0.07 | 7.37 ± 0.05 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Leontiou, A.A.; Kechagias, A.; Kopsacheili, A.; Kollia, E.; Oliinychenko, Y.K.; Stratakos, A.C.; Proestos, C.; Salmas, C.E.; Giannakas, A.E. Carvacrol@ZnO and trans-Cinnamaldehyde@ZnO Nanohybrids for Poly-Lactide/tri-Ethyl Citrate-Based Active Packaging Films. Molecules 2025, 30, 4646. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234646

Leontiou AA, Kechagias A, Kopsacheili A, Kollia E, Oliinychenko YK, Stratakos AC, Proestos C, Salmas CE, Giannakas AE. Carvacrol@ZnO and trans-Cinnamaldehyde@ZnO Nanohybrids for Poly-Lactide/tri-Ethyl Citrate-Based Active Packaging Films. Molecules. 2025; 30(23):4646. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234646

Chicago/Turabian StyleLeontiou, Areti A., Achilleas Kechagias, Anna Kopsacheili, Eleni Kollia, Yelyzaveta K. Oliinychenko, Alexandros Ch. Stratakos, Charalampos Proestos, Constantinos E. Salmas, and Aris E. Giannakas. 2025. "Carvacrol@ZnO and trans-Cinnamaldehyde@ZnO Nanohybrids for Poly-Lactide/tri-Ethyl Citrate-Based Active Packaging Films" Molecules 30, no. 23: 4646. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234646

APA StyleLeontiou, A. A., Kechagias, A., Kopsacheili, A., Kollia, E., Oliinychenko, Y. K., Stratakos, A. C., Proestos, C., Salmas, C. E., & Giannakas, A. E. (2025). Carvacrol@ZnO and trans-Cinnamaldehyde@ZnO Nanohybrids for Poly-Lactide/tri-Ethyl Citrate-Based Active Packaging Films. Molecules, 30(23), 4646. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234646