Abstract

Curcumin has long been used for health purposes and is currently attracting significant research interest. In this study, we present a series of curcumin derivatives featuring structural modifications, including methoxy groups, short alcohol chains, and bromine atoms. The cytotoxic activity of the compounds obtained was tested against BA/F3 wt, BA/F3 del52, BA/F3 ins5, K562, Jurkat, HCT-116, and MDA-MB-231 cell lines and non-cancerous Balb/3T3 fibroblast lines. The most promising compounds 2a, 6a, and 9a demonstrated anticancer activity comparable to that of doxorubicin, while exhibiting toxicity toward fibroblasts similar to natural curcumin. In addition, thanks to microscopic fluorescence analysis, a mechanism of action was proposed for the most active compounds against the HCT-116 cell line. Some compounds exhibit moderate or strong proapoptotic activity, while others are characterized by cytostatic activity. Studied compounds demonstrated the DNA-intercalation ability and increased the content of cellular ROS in treated HCT-116 cells.

1. Introduction

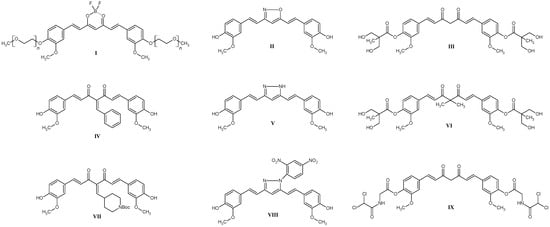

Curcumin derivatives are the subject of intense research in the context of cancer therapy due to their enhanced biological activity and more favorable pharmacokinetic properties relative to natural curcumin (Figure 1) [1,2]. Numerous chemical modifications—such as PEGylation, encapsulation in nanocarrier structures, and isotope labeling—have been shown to enhance water solubility, chemical stability, and bioavailability, resulting in markedly more potent anticancer activity [3,4,5,6]. In colorectal cancer studies, it has been demonstrated that select curcumin derivatives can inhibit the activity of the NF-κB signaling pathway and induce apoptosis through caspase activation. At the same time, a reduction in tumor cell proliferation and modulation of the expression of pro- and anti-apoptotic proteins such as Bax and Bcl-2 have been observed [2,3,7]. In breast cancer models, it has been noted that curcumin derivatives can modulate the activity of key signaling pathways involved in tumor development and progression, including the PI3K/Akt/mTOR, MAPK, Wnt/β-catenin, and JAK/STAT pathways. Effects on these molecular mechanisms have been linked to reducing the proliferation, migration, and invasive capacity of cancer cells, as well as potentially overcoming drug resistance (Structures III, VI, IX, Figure 1) [1]. Curcumin derivatives have shown therapeutic potential in the treatment of prostate cancer, primarily through modulation of key signaling pathways linked to factors such as NF-κB, EGFR, and MAPK, leading to the induction of apoptosis and inhibition of cancer cell proliferation (Structures IV, VII, Figure 1) [2,7]. In esophageal cancer, curcumin derivatives have been demonstrated to inhibit tumor cell proliferation, lead to cell cycle arrest, and induce apoptosis. The mechanism of these actions involves, among other things, modulation of the expression of proteins such as p53, Bax, and Bcl-2, and inhibition of the activity of the transcription factor NF-κB, which plays a key role in inflammatory reactions and cancer progression [8]. In liver tumors, curcumin derivatives exhibit anti-inflammatory effects by inhibiting the expression of cytokines, such as TNF-α and IL-6, as well as the activity of key signaling kinases (MAPK, JAK/STAT), leading to suppression of processes that contribute to carcinogenesis. Additionally, these compounds inhibit the process of epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT), which translates into reduced invasiveness and migration of tumor cells [4]. It is also worth noting the importance of radioisotope-labeled derivatives, which allow imaging of tumors and delivery of therapeutic compounds directly to the affected tissues [5]. PEGylated curcumin derivatives (Structure I, Figure 1) exhibit enhanced cytotoxicity against tumor cells, due to both the induction of oxidative stress and the modulation of signaling pathways involved in cell cycle regulation and cellular stress response mechanisms [6]. Another mechanism of anticancer activity is oxidative DNA breakage involving copper ions and simultaneous ROS generation. Additionally, curcumin and its derivatives can also inhibit copper transporters, which are essential for cell survival. Moreover, targeting NF-κB and DYRK2 factors in synergy with ROS ROS-driven pathway suppresses tumor cell proliferation [9]. Importantly, some curcumin derivatives act synergistically with cytostatic agents such as cisplatin—not only enhancing the anticancer effect, but also reducing toxicity to healthy tissues [10]. The diketone moiety, which is a central part of the curcumin molecule, can be modified easily in many different ways. Most commonly, it is changed into either a pyrazole or an oxazole ring (Structures II, V, and VIII, Figure 1) by employing various hydrazine or hydroxylamine derivatives [1,11]. The modification we have decided to utilize—the introduction of the BF2 moiety is steadily gaining more attention. It appeared first as a reaction steering group to increase the yield of curcumin synthesis when compared to the Pabon method [12]. Soon after, however, it turned out that its presence can have a beneficial effect on the anticancer activity of curcuminoid [13,14]. While it is unknown if the presence of the BF2 moiety changes any mechanism or target, the presence of fluorine is important. Kim et al. have shown that substituting fluorine, for example, with phenyl rings does not change the antiproliferative activity when compared to curcumin [15]. A common modification employed when searching for new biologically active molecules is halogenation [16]. Most of the halogenated curcumins and curcuminoid derivatives incorporate fluorine in their structure, leaving other halogens underrepresented [1,17,18,19]. Thus, in this work, we have focused on testing whether bromine could offer any benefits. The broad spectrum of activity exhibited by curcumin derivatives—including their modulation of molecular pathways and demonstrated therapeutic potential across various cancer types—positions them as one of the most promising avenues in the development of contemporary oncological treatment strategies.

Figure 1.

The most interesting and promising curcumin derivatives being the object of interest of scientists from the literature review.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Synthesis

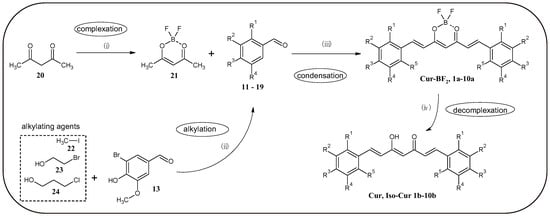

In this work, the method for obtaining curcuminoid complexes with BF2, which was developed by Liu et al. [12], was used (Figure 2). First, the corresponding aromatic aldehydes (17–19) were obtained by nucleophilic substitution reaction, using 5-bromovanillin and halogenated aliphatic compounds as substrates. Then, the previously obtained acetylacetone complex (21) with BF2 underwent an aldol condensation reaction to obtain curcuminoid complexes with BF2 1a–10a. The final step was a hydrolysis reaction in a microwave reactor to obtain curcuminoids with a free keto-enol moiety 1b–10b. This reaction was developed by Abonia et al. [13]. Such a synthetic pathway makes it possible not only to increase the total yield of the process, but also to obtain an additional series of compounds with high anticancer potential [6,13,20]. Table 1 shows the position of substituents in final compounds and substrates.

Figure 2.

General synthesis plan of curcuminoids obtained in this study and precursors for their synthesis. (i) BF3·Et2O, DCM, 24 h, 20 °C; (ii) LiOH·H2O or K2CO3 DMF, 24h 80 °C; (iii) n-BuNH2, tributyl borate, toluene, 24 h, 65 °C; (iv) Na2C2O4, MeOH:H2O 4:1, MW, 8 min, 140 °C. The numbered substances: 11—vanillin; 12—isovanillin; 13—5-bromovanillin; 14—2-bromoisovanillin; 15—3,4,5-trimethoxybenzaldehyde; 16—syringaldehyde, 20—acetylacetone, 21—acetylacetone-BF2 complex, 22—iodomethane, 23—2-bromoethanol, 24—3-chloropropanol. Abbreviations: DCM, dichloromethane; DMF, dimethylformamide; MW, microwave.

Table 1.

The structure of the synthetized aldehydes (11–19) and curcuminoid compounds (1a–10b, Cur, Cur-BF2, Iso-Cur) is described by the type and position of substituents.

2.2. NMR Study

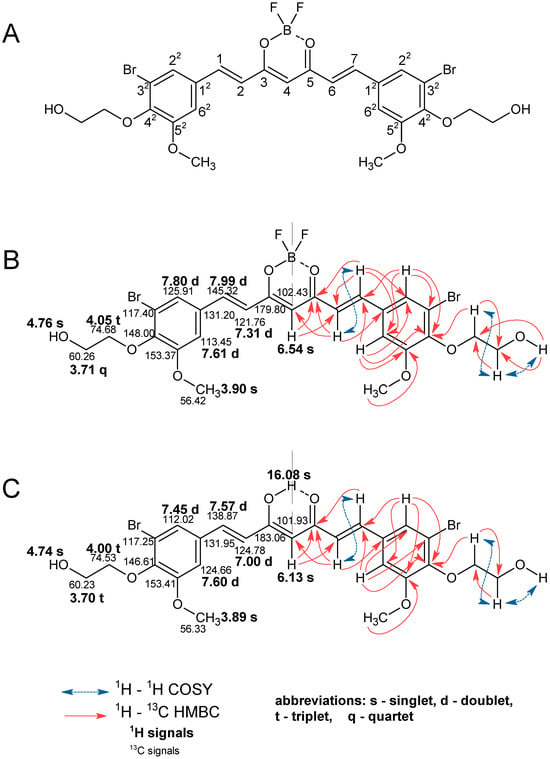

The identity of the obtained compounds was confirmed by 1D 1H and 13C NMR techniques. To assign the observed signals in the 1D NMR experiments to the individual structural elements of the molecules, 2D correlation experiments (1H-1H COSY, 1H-13C HSQC, and 1H-13C HMBC) were also carried out, what is demonstrated in Figure 3 using the example of derivatives 5a and 5b.

Figure 3.

1H and 13C NMR data for compounds 5a and 5b in DMSO. (A) Numbering of atoms in the curcuminoid molecule. (B) Annotated 1H and 13C NMR signals for 5a. (C) Annotated 1H and 13C NMR signals for compound 5b.

As expected, NMR data confirmed that curcuminoids are present in the enol form. Based on the NMR spectra, the structure of compound 5a was confirmed by observing a characteristic signal of the CH group at the C4 position singlet with integration of one proton at 6.54 ppm. For compound 5b, the corresponding signal is observed at 6.13 ppm, and a broad signal (singlet) from the OH group is also visible at 16.08 ppm as a result of tautomerization. The presence of carbonyl groups at the C3 and C5 positions is confirmed by the signal in the 13C NMR spectrum at 179.80 ppm for 5a and 183.06 ppm for 5b. The presence of -HC=CH- vinylene groups was confirmed by the presence of signals from protons and carbons at positions 1, 2, 6, and 7. Signals for H1 and H7 are observed as doublets for compounds 5a and 5b at 7.99 ppm and 7.57 ppm, respectively. Similarly, doublets for protons H2 and H6 are also observed at 7.31 ppm for 5a and 7.00 ppm for 5b. In all the curcuminoids obtained, the vinylene protons appear in trans configuration, as confirmed by the value of the JH,H constant at ca. 16 Hz. For compound 5a, signals from C1 and C7 were observed at 145.32 ppm, and for 5b at 138.87 ppm. Signals from C2 and C6 are observed at 121.76 ppm for 5a and 124.78 ppm for 5b. With these data, the presence of the BF2 group is confirmed, as shifts from 1H and 13C signals are observed at positions 1, 2, 6, and 7 of compound 5a compared to 5b. In aromatic rings, signals from protons are observed as two doublets. For compound 5a, these are peaks at 7.80 ppm and 7.61 ppm for H62 and H22, respectively. For compound 5b, these are signals at 7.45 ppm and 7.60 ppm. In the 13C NMR spectra, the signals for C12-C62 are represented by values of 131.20 ppm, 113.45 ppm, 153.37 ppm, 148.00 ppm, 117.40 ppm, and 125.91 ppm for compound 5a and 131.95 ppm, 124.66 ppm, 153.41 ppm, 146.61 ppm, 117.25 ppm, and 112.02 ppm for compound 5b. In the 1H NMR spectrum, signals from the methoxy group are represented by singlets at 3.90 ppm for compound 5a and 3.89 ppm for compound 5b. In the 13C NMR spectrum, these signals are at 56.42 ppm and 56.33 ppm for compounds 5a and 5b, respectively. For an alcohol chain linked by an ether group to an aromatic ring at the C42 position, the characteristic signals in the 1H NMR spectrum are one singlet, one quartet, and one triplet for compound 5a. A proton from the OH group is observed at 4.76 ppm. Protons from the chain are observed at 3.71 ppm and 4.05 ppm, that closer to the alcohol and ether groups, respectively. In the 13C MNR spectrum, there are peaks at 60.23 ppm and 74.53 ppm, respectively. For compound 5b, the singlet from the proton of the alcohol group is observed at 4.74 ppm. The signal from protons closer to the alcohol group is observed as a triplet at 3.70 ppm, and for protons closer to the ether group is observed at 4.00 ppm as a triplet. On the 13C NMR spectrum, these are the signals at 60.23 ppm and 74.53 ppm, respectively. All NMR spectra from the other compounds are included in the Supplementary Materials (Figures S1–S132).

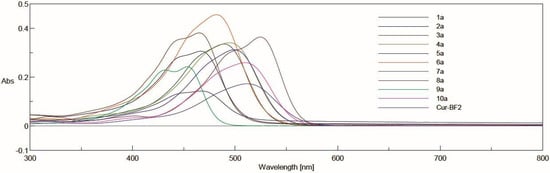

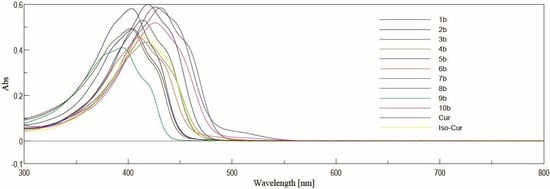

2.3. UV-Vis Study

UV-Vis spectra were performed for solutions in acetonitrile at the concentrations 5 µM and 10 µM for complexes with BF2 and derivatives after decomplexation, respectively (Figure 4 and Figure 5). In general, the range of absorbance maxima is wide for each series. In the series of curcuminoid complexes with BF2, the absorbance maxima for these compounds are in the range from 453 nm to 525 nm. For derivatives with a free keto-enol moiety, the values are from 394 to 431 nm. Depending on the derivative, the difference in λmax after decomplexation is from 59 nm to 94 nm.

Figure 4.

The absorption spectra in acetonitrile for Cur-BF2 and derivatives 1a–10a. The compounds were dissolved at a concentration of 5 µM in acetonitrile, and acetonitrile was used as a blank. The spectra were recorded using a standard cuvette port for single-sample absorbance.

Figure 5.

The absorption spectra in acetonitrile for Cur, Iso-Cur, and derivatives 1b–10b. The compounds were dissolved at a concentration of 10 µM in acetonitrile, and acetonitrile was used as a blank. The spectra were recorded using a standard cuvette port for single-sample absorbance.

2.4. X-Ray Diffraction Studies

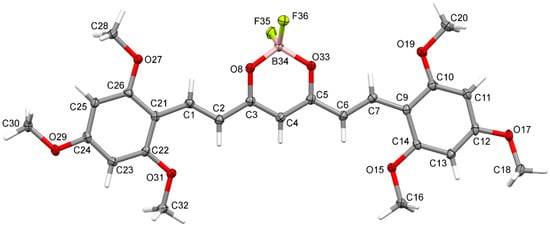

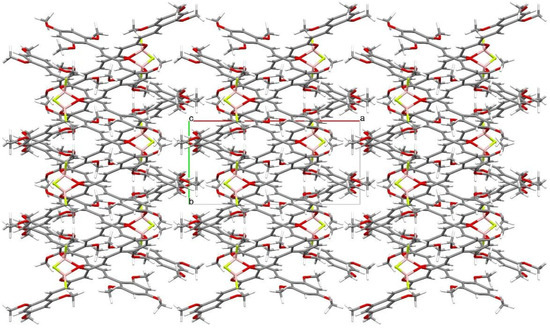

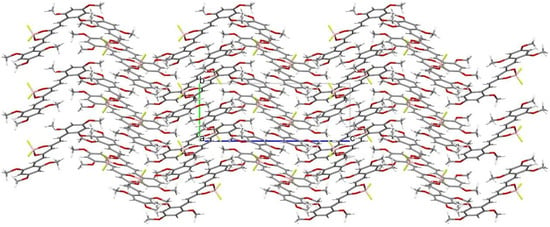

Crystal structure of (1E,4Z,6E)-5-((difluoroboranyl)oxy)-1,7-bis(2,4,6-trimethoxyphenyl)-hepta-1,4,6-trien-3-one was determined by single-crystal X-ray diffraction. Crystals were grown from DMF by slow evaporation of the solution. The crystal structure of C23H27BF2O8 is monoclinic with P21/c space group. The asymmetric unit of C23H27BF2O8 contains one molecule in the asymmetric unit. Atom labeling of C23H27BF2O8 is shown in Figure 6. Packing of molecule 8a along the directions [001] and [100] are shown in Figure 7 and Figure 8.

Figure 6.

Anisotropic ellipsoid representation of (1E,4Z,6E)-5-((difluoroboranyl)oxy)-1,7-bis(2,4,6-trimethoxyphenyl)hepta-1,4,6-trien-3-one 8a, showing the atom-labeling scheme. Displacement ellipsoids are drawn at the 50% probability level, and H atoms are shown as small spheres of arbitrary radii.

Figure 7.

Packing of molecules (1E,4Z,6E)-5-((difluoroboranyl)oxy)-1,7-bis(2,4,6-trimethoxyphenyl)hepta-1,4,6-trien-3-one, along the direction [001]. Atomic colors according to the convention adopted for Figure 6.

Figure 8.

Packing of molecules (1E,4Z,6E)-5-((difluoroboranyl)oxy)-1,7-bis(2,4,6-trimethoxyphenyl)hepta-1,4,6-trien-3-one, along the direction [100]. Atomic colors according to the convention adopted for Figure 6.

Analysis of the X-ray data showed that the C23H27BF2O8 molecule is not quite planar. The C(9)-C(14) and C(21)-C(26) rings are deviated from the plane of the molecule by 5.73(7) and 12.59(6) degrees, respectively. CH···O and CH···F interactions cause a bending of the molecule as shown by the increased valence angles C(21)-C(1)-C(2) 131.0(1) and C(6)-C(7)-C(9) 130.7(1). Intermolecular CH-F interactions to the F(35) atom also cause the boron atom to deviate from the plane formed by the O(8)-C(3)-C(4)-C(5)-O(33) atoms. The angle to the plane formed by the O(33)-B(34)-O(8) atoms is 22.3(1) degrees. In the crystal structure of C23H27BF2O8, weak interactions of C-H···O and CH···F-type connect the molecules in a three-dimensional network. The rest of the crystallographic data is included in Table 2 and in the Supplementary Materials (Tables S1–S6).

Table 2.

Experimental details for compound 8a.

2.5. Biological Activity of Tested Compounds

The results of cell assays show that all obtained derivatives, irrespective of their activity against pathological cells, show low cytotoxicity to healthy cells (Balb/3T3 fibroblast line). When comparing IC50 values to natural curcumin, which is considered safe and non-toxic, we can see that most derivatives display comparable or even lower cytotoxicity. The exception is compound 6b with an IC50 value of 20.88 + −3.84 µM. In contrast, doxorubicin, which was used as a reference compound, showed the same cytotoxicity against both normal and cancerous cells.

Considering activity against abnormal cells, the presence of the BF2 group in the central part of the molecule appears to be crucial. The absence of this group resulted in a decrease in anticancer activity of about 2–10 times in most cases. In extreme instances (derivative 9a/9b), the lack of this group resulted in an approximately 45-fold decrease in activity against the BA/F3 wt and BA/F3 ins5 lines and an approximately 70-fold decrease against the BA/F3 del52 line (Table 3). Activity charts in the 72 h MTT test are included in the Supplementary Materials (Figure S165).

Table 3.

Toxicity of compounds towards tumor and non-tumor cells (MTT data on 72 h of cell exposure, M ± SD). Values of IC50 below 2 µM were highlighted by bold text in green.

2.5.1. Structure–Activity Relationships for Curcuminoids with Methoxyl Groups

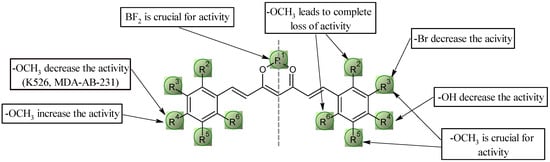

A preliminary analysis of the structure–activity relationship analysis grouped the results by cell line into five categories. The most important conclusions are presented graphically in Figure 9 and Figure 10. In the first group, which includes the BA/F3 wt, BA/F3 del52, and BA/F3 ins5 cell lines, and the second group represented by the Jurkat cell line, compounds 6a and 9a exhibited the highest activity. These two derivatives have very similar IC50 values to doxorubicin. The most favorable configuration seems to be the presence of methoxyl groups at positions 32, 52, and/or 42. Given that the most active derivatives are 6a and 9a, the absence of the -OH group in position 42 is crucial, as this resulted in an approximately 10-fold increase in activity against these cell lines. It is interesting to note that changing the position of the methoxyl group from 32 or 52 to 22 or 62 results in an almost complete loss of activity against all lines tested. The replacement of one of the methoxyl groups with bromine at position 32 also appears to be an unfavorable change, resulting in an approximately 10-fold decrease in activity.

Figure 9.

Key structural elements for the methoxyl curcuminoids group.

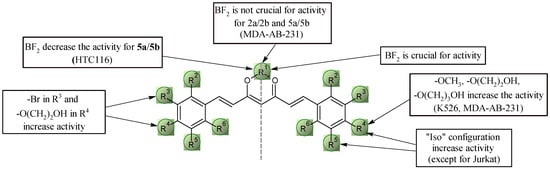

Figure 10.

Key structural elements for curcuminoids and bromo-curcuminoids.

In the case of the K562 leukemia cell line, the most favorable configuration is the presence of methoxy groups at positions 32 and 52 (compound 9a), resulting in the same IC50 value as for doxorubicin. The presence of a methoxyl or -OH group at position 42 leads to a decrease in activity by four- and nine-fold, respectively. Similarly, substituting the methoxy group with bromine at position 32 leads to a significant reduction in activity. Concerning the presence of the BF2 group, the relationships follow the general trend except for the pair of compounds 6a–6b, where the differences in the activity of these compounds are not significant.

In the case of HTC116 colon cancer cells, structure–activity relationships are similar—the presence of methoxyl groups at positions 32, 52, and/or 42 seems to be the most favorable configuration, leading to IC50 values the same as doxorubicin. As in the above-mentioned group in the case of pair 6a–6b, the absence of the BF2 group does not lead to a decrease in activity.

For the MDA-MB-231 cell line, the structure–activity relationship remains consistent—the replacement of methoxyl for bromine at position 32 and the unblocking of the -OH group at position 42 results in an approximately 10-fold decrease in activity. Methoxyl groups at positions 22, 42, and/or 62 are an undesirable configuration, as it is characterized by a complete lack of activity against this cell line. The most favorable configuration is the presence of methoxy groups at positions 32 and 52 (compound 9a).

2.5.2. Structure–Activity Relationships for Curcuminoids and Bromo-Curcuminoids

In case of BA/F3 wt, BA/F3 del52, Ba/F3 ins5 cell lines 2a and Cur-BF2 have the highest activity (comparable to doxorubicin). In the context of brominated curcumin derivatives, the key is the presence of bromine at position 32 and the substitution of the alcohol chain via an ether bond at position 42. The length of the chain is also important; extending it by one -CH2- group resulted in an approximately 10-fold decrease in activity. Blocking the -OH group at position 42 with a methyl group is also a favorable modification, which resulted in a two–four-fold increase in activity. In the case of curcumin, the “iso” configuration (methoxyl group in the para position, hydroxyl group in the meta position) is more desirable. This leads to a 2–5-fold increase in activity. In contrast, for brominated curcuminoids, no significant change in activity was observed.

Very similar relationships can be observed for activity against cells of the Jurkat line. Although in the case of the “iso” configuration, no significant increase in activity is observed (Figure 10).

In the case of the K562 leukemia cell line, compounds Cur-BF2 and 2a showed high levels of activity, although weaker than doxorubicin. As is the case for natural curcumin, for the series of brominated derivatives, the more favorable configuration is the “iso”, in which an approximately four-fold increase in activity is observed. The most favorable structural modification within this group of compounds is the introduction of an alcohol chain at position 42 (compound 2a), with neither elongation of the chain by an additional -CH2- group nor substitution with a methyl group significantly affecting anticancer activity.

In the case of HTC116 colon cancer cells, we can observe a slightly different correlation. First of all, the “iso” configuration is not characterized by greater activity against this cell line. Although the most active compounds are 2a, Cur-BF2, 6a, 6b, and 9a, an inverse relationship is characterized by the pair of compounds 5a and 5b. Namely, the absence of the BF2 group results in an approximately four-fold increase in activity.

In the case of the MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cell line, only one compound (9a) has a similar level of activity to doxorubicin. Most of the compounds in the series show good cytotoxic activity at around 4–7 µM. As before, the “iso” configuration for both natural curcumin and its derivative contribute to an approximately five-fold increase in activity. For a series of brominated derivatives, the key is to block the -OH group at position 42 with a methyl group or a short alcohol chain. Interestingly, in this case, the chain length does not matter. It is also interesting to note the level of activity of the derivatives with the alcohol group, particularly in terms of the presence of the BF2 group; the loss of this group does not result in a decrease in activity.

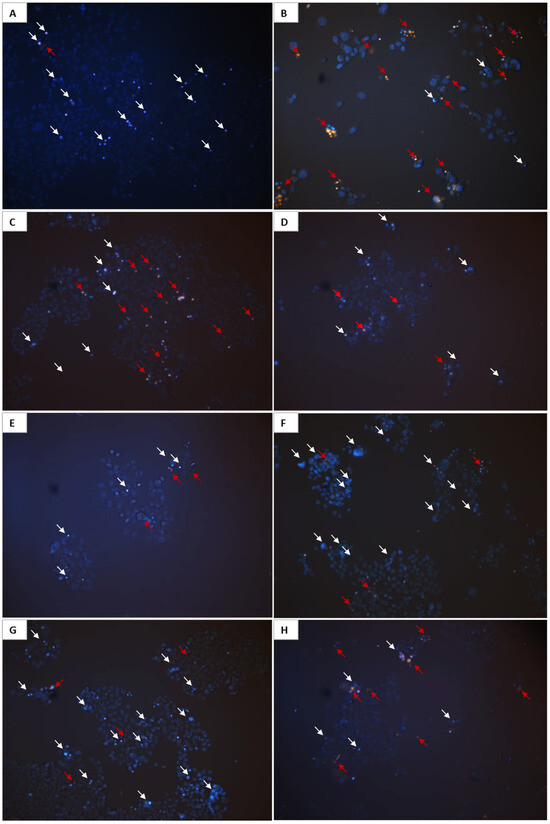

2.5.3. Fluorescence Microscopic Analysis of Cell Death Induced by the Most Active Compounds

The relationship between the structure and activity of curcuminoids and bromo-curcuminoids, supported by cytotoxicity data demonstrating their varied impact on cell survival, is illustrated through fluorescence images of HCT-116 cells. These cells, treated with the most potent compounds for 72 h and stained with Hoechst 33342/EtBr, reveal how structural differences affect cell shape and condition. Doxorubicin (0.5 µM), used as a positive control, shows the highest level of cell death. In the doxorubicin-treated sample (Figure 11B), the intense orange/red fluorescence of EtBr indicates significant membrane damage and cell death, due to its well-known mechanism of intercalating into DNA and inhibiting topoisomerase II, leading to DNA damage and apoptosis or necrosis, as evidenced by fragmented or diffusely stained nuclei reflecting this cytotoxic effect. The control cells (A) show normal nuclear morphology with uniform blue Hoechst 33342 staining and low amounts of orange/red EtBr signal, indicating healthy, intact cells with no significant chromatin condensation or cell death. Curcumin (C, 1 µM) exhibits a moderate cytotoxic effect with fewer dead cells marked by orange/red EtBr fluorescence than in doxorubicin. Additionally, several cells display condensed chromatin indicated by white arrows, suggesting a mild induction of apoptosis. Samples treated with 1 µM 5b (D), 6a (E), and 9a (H) show a markedly reduced cell number compared to the control and other samples along with a small amount of orange/red EtBr staining, suggesting that these compounds may exert a cytostatic effect. In contrast, 6b (F) and Cur-BF2 (G) induce significant chromatin condensation as evidenced by white arrows and prominent Hoechst 33342 staining, suggesting a strong pro-apoptotic activity, with some cells transitioning to death as indicated by minor orange/red EtBr signals.

Figure 11.

Representative fluorescent images of HCT-116 cells treated with 0.5 μM doxorubicin (B), 1 μM Cur (C), 5b (D), 6a (E), 6b (F), Cur-BF2 (G), 9a (H), and control cells (A) for 72 h, stained with Hoechst 33342/EtBr. White arrows indicate chromatin condensation; red arrows indicate dead cells. Magnification is 200×.

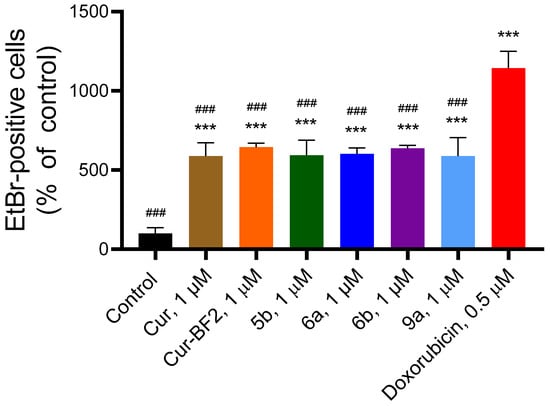

The studied compounds significantly increased the fluorescence of EtBr in treated HCT-116 cells (Figure 12).

Figure 12.

Compounds Cur, 5b, 6a, 6b, Cur-BF2, and 9a (1 μM) influenced the level of EtBr-positive cells in the HCT-116 cells after 72 h treatment. The data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (M ± SD). ***—p < 0.001 (significant changes compared to the control cells; ###—p < 0.001 significant changes compared to the effect of doxorubicin (1 μM).

Compounds Cur, 5b, 6a, 6b, Cur-BF2, and 9a (1 μM) elevated the content of EtBr-positive cells by 5.9–6.4 times as compared to the control (non-treated) HCT-116 cells.

2.5.4. The Affinity of Studied Compounds Towards DNA

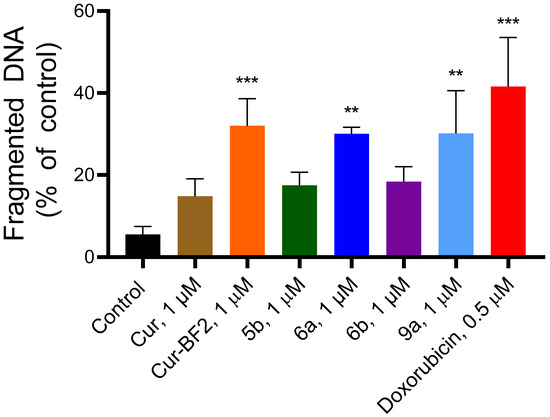

DNA fragmentation and chromatin condensation are terminal hallmarks of apoptosis and are frequently induced by anticancer compounds. We used the spectroscopic diphenylamine assay to evaluate the amount of DNA fragmentation in HCT-116 cells under their treatment with the studied compounds and doxorubicin.

An increased content of the fragmented DNA was observed in the treated cells under the action of the Cur, 5b, 6a, 6b, Cur-BF2, and 9a and Dox (Figure 13). The Cur at 1 µM induced DNA fragmentation at the level of 14.81 ± 4.24%, 5b induced 17.49 ± 3.19% of DNA fragmentation, and 6b induced 18.39 ± 3.61% of DNA fragmentation. Compounds Cur-BF2, 6a, and 9a at 1 µM induced a higher DNA fragmentation level (32.02 ± 6.62%, 30.09 ± 1.60%, and 30.20 ± 10.36%, respectively). Doxorubicin at 0.5 µM caused 41.55 ± 12.00% of DNA fragmentation in HCT-116 cells (Figure 12).

Figure 13.

The percentage of fragmentation DNA in the HCT-116 cells after 72 h treatment with compounds Cur, 5b, 6a, 6b, Cur-BF2, and 9a (1 μM), and doxorubicin (0.5 μM). The data are presented as M ± SD. **—p < 0.01 and ***—p < 0.001 (significant changes compared to the control cells).

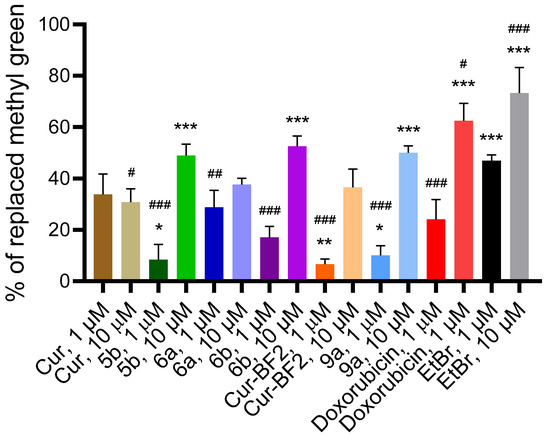

When a compound directly interacts with DNA (through intercalation, alkylation, or inhibition of topoisomerases), the link to these apoptotic events is direct. We used the spectroscopic DNA/methyl green displacement assay to identify the ability of the tested compounds to intercalate into the DNA molecule (Figure 14). When an intercalator or groove-binding compound is introduced, it competes with methyl green for DNA binding sites. A higher displacement of methyl green indicates a stronger interaction of the compound with DNA.

Figure 14.

The percentage of methyl green displaced from its DNA complex by the tested compounds, as well as by the reference agents doxorubicin and EtBr, at 1 and 10 μM. *—p < 0.05, **—p < 0.01, ***—p < 0.001 (significant changes compared with the effect of doxorubicin (1 μM); #—p < 0.05, ##—p < 0.01, ###—p < 0.001 significant changes compared with the impact of EtBr (1 µM). Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation.

The known intercalator doxorubicin displaced 19.52–58.33% of methyl green from its DNA complex (Figure 14). Another intercalator, EtBr, displaced 45.24–61.90% of methyl green from its DNA complex. The tested compounds exhibited DNA-methyl green displacement activity comparable to that of DOX and EtBr. Compounds Cur, 5b, 6a, 6b, Cur-BF2, and 9a (1 μM) displaced methyl green from the DNA–methyl green complex by 2.50–27.50%. Compounds Cur, 5b, 6a, 6b, Cur-BF2, and 9a (10 μM) demonstrated higher ability to replace methyl green from the DNA–methyl green complex (25.00–50.00%). These results indicate that compounds Cur, 5b, 6a, 6b, Cur-BF2, and 9a possess a high affinity for DNA via intercalation. One can say that the studied compounds directly interact with DNA.

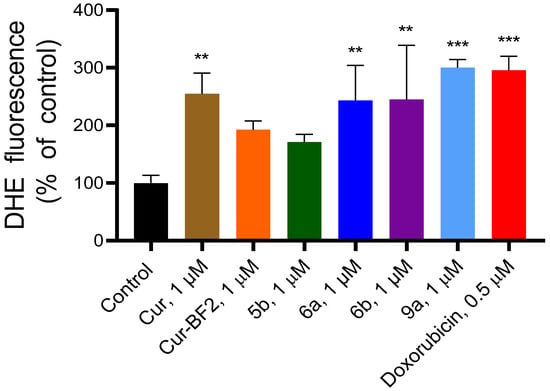

2.5.5. Tested Compounds Influence Reactive Oxygen Species Level in HCT-116 Cells

The ability of Cur, 5b, 6a, 6b, Cur-BF2, and 9a (1 μM) to elevate the reactive oxygen species (ROS) level in HCT-116 cells was found using dihydroethidium (DHE) staining of cells (Figure 15). The fluorescent probe dihydroethidium (DHE) is readily taken up by cells and reacts specifically with superoxide radicals to form the red fluorescent product 2-hydroxyethidium (2-OH-E+), allowing selective detection of intracellular O2−. However, DHE can also undergo nonspecific oxidation to ethidium (E+), whose fluorescence overlaps with that of 2-OH-E+. Thus, the combined fluorescence of 2-OH-E+ and E+ provides a reliable measure of overall ROS generation associated with superoxide production [21]. The Cur increased the ROS content by 2.55 times, compound 5b—by 1.71 times, 6a—by 2.43 times, 6b—by 2.45 times, Cur-BF2—by 1.93 times, and 9a—by 3 times as compared to the control. Doxorubicin at 0.5 µM increased the ROS level in HCT-116 cells by 2.96 times. The obtained results correlate with the data that curcumin, demethoxycurcumin, and bisdemethoxycurcumin induced apoptosis in tumor cells via DNA damage and ROS production [9].

Figure 15.

Compounds Cur, 5b, 6a, 6b, Cur-BF2, and 9a (1 μM) induced the elevation of DHE fluorescence in the HCT-116 cells after 72 h treatment. The data are presented as M ± SD. **—p < 0.01 and ***—p < 0.001 (significant changes compared to the control cells).

Thus, Cur, 5b, 6a, 6b, Cur-BF2, and 9a elevated cellular ROS content in HCT-116 cells.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials

All substrates and solvents used in the synthesis were purchased from either Alfa Aesar, TCI, or Merck. NMR spectra were recorded at 298 K either on a Bruker Avance III 500 spectrometer (Bruker Daltonics, Bremen, Germany) using a PABBO BBF/1Hand19F 5 mm probe or an Agilent DD2 800 spectrometer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) equipped with a 5 mm 1H(13C/15N) probe head. UV-Vis spectra were recorded on a UV-Vis Jasco V-770 spectrometer (JASCO, Tokyo, Japan). The chromatographic analysis of new compounds purity was performed on an Agilent 1260 Infinity II LC System (Agilent Technologies, Bolinem, Germany) equipped with a quaternary pump (model G7111B) and degasser, a vial sampler (model G7129A) set at 25 °C, multicolumn thermostat (model G7116A) set at 25 °C, and diode array (DAD WR, model G7115A) detector. The DAD detector was used for the purity test, and the detection wavelength for the DAD detector was adjusted for each compound tested at its absorption maxima. The ESI-MS analyses were performed on the Q-TRAP 4000 mass spectrometer from AB-Sciex (Foster City, CA, USA). All ESI-MS spectra are included in the Supplementary Materials (Figures S133–S164). The melting point (M.p) was determined using a “Stuart” apparatus (Bibby Sterlin Ltd., Caerphilly Wales, UK), using single-ended capillaries.

3.1.1. Reagents Used for In Vitro Experiments

MTT (3-[4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl]-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide) test, crystal violet, Hoechst-33342, EtBr, DHE, doxorubicin, dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO), salmon sperm DNA, Tris, EDTA, Triton X-100, diphenylamine, and methyl green were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA. Trichloroacetic acid, glacial acetic acid, acetaldehyde solution, and H2SO4 were purchased from SferaSim (Lviv, Ukraine).

3.1.2. Cell Lines

MDA-MD-231 human breast adenocarcinoma cell line, HCT-116 colon adenocarcinoma cell line, Jurkat human T lymphocyte cell line, K562 human chronic myelogenous leukemia cell line, and BALB/3T3 mouse embryonic fibroblasts were kindly provided by a Collection at the Institute of Molecular Biology and Genetics, National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine (Kyiv, Ukraine). Murine interleukin-3-dependent pro-B cell lines Ba/F3 wt, Ba/F3 Calr del52, and Ba/F3 Calr ins5 were kindly provided by Prof. Robert Kralovics, Medical University of Vienna, Austria.

Cells were maintained in DMEM (Biowest, France) or RPMI-1640 medium (Biowest, France), containing 10% of fetal bovine serum (FBS, Biowest, France) according to recommendations of American Type Culture Collection (ATCC), under the incubation conditions of 5% CO2 humidity at 37 °C.

3.2. Synthesis

3.2.1. Aldehyde Synthesis–General Procedure

Aromatic aldehyde alkylation was performed using the standard nucleophilic substitution method. To a solution of 5-bromovanillin in DMF, 1.05 equivalents of iodomethane, 2-bromoethanol, or 3-chloropropan-1-ol, and 1.05 equivalents of K2CO3 (for compound 17) or LiOH monohydrate (for compounds 18 and 19) were added. The reaction was then heated to 80 °C and stirred for 24 h. After that, the reaction was quenched with distilled water. Then, the product was extracted with chloroform from water alkalized with sodium hydroxide (pH ca. 11) and purified by hot recrystallization from hexane.

3-Bromo-4,5-dimethoxybenzaldehyde (17) ESI [M + H]+ m/z 244.98

1H NMR (800 MHz, CDCl3) δ 9.85 (s, 1H), 7.66 (d, J = 1.8 Hz, 1H), 7.39 (d, J = 1.8 Hz, 1H), 3.95 (s, 3H), 3.94 (s, 3H).

13C NMR (201 MHz, CDCl3) δ 189.85, 154.82, 151.82, 133.05, 128.77, 117.94, 110.12, 60.84, 56.26.

Rf(hexane/ethyl acetate 2:1): 0.75, yield 98.9% white amorphous solid.

3-Bromo-4-(2-hydroxyethoxy)-5-methoxybenzaldehyde (18) ESI [M + H]+ m/z 274.99

1H NMR (800 MHz, CDCl3) δ 9.86 (s, 1H), 7.67 (d, J = 1.8 Hz, 1H), 7.41 (d, J = 1.8 Hz, 1H), 4.37–4.19 (m, 2H), 3.95 (s, 3H). 3.91–3.79 (m, 2H), 2.74 (t, J = 6.5 Hz. 1H).

13C NMR (201 MHz, CDCl3) δ 189.82, 154.09, 150.70, 133.38, 128.98, 118.20, 110.25, 75.88, 62.05, 56.51.

Rf(ethyl acetate): 0.74, yield 70.1% white crystals.

3-Bromo-4-(3-hydroxypropoxy)-5-methoxybenzaldehyde (19) ESI [M + H]+ m/z 289.00

1H NMR (800 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 9.88 (s, 1H), 7.77 (s, 1H), 7.53 (s, 1H), 4.48 (t, J = 5.1 Hz, 1H), 4.15 (t, J = 6.5 Hz, 2H), 3.90 (s, 3H), 3.59 (dd, J = 11.6, 6.3 Hz, 2H), 1.86 (p, J = 6.4 Hz, 2H).

13C NMR (201 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 190.91, 153.70, 150.07, 132.84, 127.22, 117.16, 111.49, 70.85, 57.52, 56.32, 33.18.

Rf(dichloromethane/acetone 10:1): 0.68, yield 74.4% white amorphous solid.

3.2.2. Curcuminoids Synthesis

Curcuminoid complexes with BF2 (1–10a) were synthesized by the condensation reaction of a BF2 complex of acetylacetone with the corresponding aldehyde (2.1 equivalent) in toluene. Tributyl borate (2 equivalents) was added as a dehydrating agent. Then, n-butylamine (0.2 equivalent) was added dropwise to the reaction mixture over 15 min. The reaction was carried out at 65 °C in nitrogen for 24 h. The dark residue was separated by filtration, then washed with a small amount of toluene and dried under vacuum. Derivative 2a was purified by 3-fold recrystallization. The total was dissolved in THF and then precipitated with 2-fold volume of toluene. The rest of the compounds were purified using column chromatography.

In order to obtain free curcuminoids, compounds from the first series were decomplexed. The curcuminoid complex with BF2 was suspended in a methanol/water (4:1) mixture, and disodium oxalate (2 equivalents) was added. The reaction mixture was heated at 140 °C for 15 min under microwave conditions in an Anton Paar Monowave 400 microwave reactor. The precipitate was filtered and purified by column chromatography.

Compounds Cur-BF2, Cur, and Iso-Cur were obtained from a library of compounds synthesized earlier in previous research work [6,20].

(1E,4Z,6E)-5-((difluoroboranyl)oxy)-1,7-bis(3-bromo-4-hydroxy-5-methoxyphenyl)hepta-1,4,6-trien-3-one (1a) ESI [M − H]− m/z 572.94, UV-Vis λmax = 489 nm, ε = 67,012 dm3·mol−1·cm−1, M.p. = 238 °C (dec.),

1H NMR (800 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 10.48 (s, 2H), 7.89 (d, J = 15.5 Hz, 2H), 7.72 (d, J = 1.8 Hz, 2H), 7.50 (d, J = 1.8 Hz, 2H), 7.12 (d, J = 15.5 Hz, 2H), 6.40 (s, 1H), 3.90 (s, 6H).

13C NMR (201 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 178.67, 148.58, 148.12, 145.56, 127.32, 126.49, 119.24, 111.67, 109.98, 101.73, 56.44.

Rf(ethyl acetate): 0.75, yield 95.0% crimson amorphous solid.

(1E,4Z,6E)-5-((difluoroboranyl)oxy)-1,7-bis(3-bromo-4-(2-hydroxyethoxy)-5-methoxyphenyl)hepta-1,4,6-trien-3-one (2a) ESI [M-F]+ m/z 642.99, UV-Vis λmax = 466 nm, ε = 61,111 dm3·mol−1·cm−1, M.p. = 215 °C (dec.),

1H NMR (800 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 7.99 (d, J = 15.6 Hz, 2H), 7.80 (d, J = 1.8 Hz, 2H), 7.61 (d, J = 1.9 Hz, 2H), 7.31 (d, J = 15.7 Hz, 2H), 6.54 (s, 1H), 4.76 (t, J = 5.6 Hz, 2H), 4.05 (t, J = 5.5 Hz, 4H), 3.90 (s, 6H), 3.71 (q, J = 5.5 Hz, 4H).

13C NMR (201 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 179.80, 153.37, 148.00, 145.32, 131.20, 125.91, 121.76, 117.40, 113.45, 102.43, 74.68, 60.26, 56.42.

Rf(ethyl acetate): 0.67, yield 66.2% orange amorphous solid.

(1E,4Z,6E)-5-((difluoroboranyl)oxy)-1,7-bis(3-bromo-4,5-dimethoxyphenyl)hepta-1,4,6-trien-3-one (3a) ESI [M + Na]+ m/z 624.96, UV-Vis λmax = 465 nm, ε = 76,119 dm3·mol−1·cm−1, M.p. = 252–254 °C (dec.),

1H NMR (800 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 7.99 (d, J = 15.7 Hz, 2H), 7.80 (d, J = 1.6 Hz, 2H), 7.63 (d, J = 1.6 Hz, 2H), 7.31 (d, J = 15.7 Hz, 2H), 6.54 (s, 1H), 3.91 (s, 6H), 3.82 (s, 6H).

13C NMR (201 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 179.86, 153.52, 148.50, 145.28, 131.48, 125.77, 121.91, 117.23, 113.54, 102.47, 60.39, 56.40.

Rf(ethyl acetate): 0.67, yield 23.4% light orange amorphous solid.

(1E,4Z,6E)-5-((difluoroboranyl)oxy)-1,7-bis(2-bromo-5-hydroxy-4-methoxyphenyl)hepta-1,4,6-trien-3-one (4a) ESI [M + H]+ m/z 575.00, UV-Vis λmax = 495 nm, ε = 68,040 dm3·mol−1·cm−1, M.p. = 257–259 °C (dec.),

1H NMR (800 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 9.68 (s, 2H), 8.09 (d, J = 15.4 Hz, 2H), 7.44 (s, 2H), 7.30 (s, 2H), 7.04 (d, J = 15.4 Hz, 2H), 6.61 (s, 1H), 3.89 (s, 3H).

13C NMR (201 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 179.15, 152.33, 146.61, 143.56, 125.32, 121.11, 117.24, 116.19, 114.13, 103.12, 56.33.

Rf(ethyl acetate): 0.52, yield 42.6% dark maroon amorphous solid.

(1E,4Z,6E)-5-((difluoroboranyl)oxy)-1,7-bis(3-bromo-4-(3-hydroxypropoxy)-5-methoxyphenyl)hepta-1,4,6-trien-3-one (5a) ESI [M + H]+ m/z 691.00, UV-Vis λmax = 468 nm, ε = 28,454 dm3·mol−1·cm−1, MP = 222–223 °C,

1H NMR (800 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 7.98 (d, J = 15.6 Hz, 2H), 7.79 (d, J = 1.8 Hz, 2H), 7.61 (d, J = 1.9 Hz, 2H), 7.30 (d, J = 15.7 Hz, 2H), 6.54 (s, 1H), 4.48 (s, 2H), 4.12 (t, J = 6.5 Hz, 4H), 3.90 (s, 6H), 3.59 (t, J = 6.4 Hz, 4H), 1.86 (p, J = 6.5 Hz, 4H).

13C NMR (201 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 179.79, 153.44, 147.92, 145.31, 131.16, 125.92, 121.74, 117.37, 113.47, 102.42, 70.82, 57.59, 56.41, 33.20.

Rf(ethyl acetate): 0.21, yield 42.9% orange amorphous solid.

(1E,4Z,6E)-5-((difluoroboranyl)oxy)-1,7-bis(3,4,5-trimethoxyphenyl)hepta-1,4,6-trien-3-one (6a) ESI [M + H]+ m/z 505.10, UV-Vis λmax = 482 nm, ε = 91,108 dm3·mol−1·cm−1, MP = 276–277 °C,

1H NMR (800 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.98 (d, J = 15.4 Hz, 2H), 6.84 (s, 4H), 6.62 (d, J = 15.4 Hz, 2H), 6.09 (s, 1H), 3.93 (s, 6H), 3.92 (s, 12H).

13C NMR (201 MHz, CDCl3) δ 179.67, 153.58, 147.46, 141.87, 129.41, 119.62, 106.50, 101.99, 61.11, 56.27.

Rf(ethyl acetate): 0.79, yield 87.7% burgundy amorphous solid.

(1E,4Z,6E)-5-((difluoroboranyl)oxy)-1,7-bis(4-hydroxy-3,5-dimethoxyphenyl)hepta-1,4,6-trien-3-one (7a) ESI [M + H]+ m/z 477.3, UV-Vis λmax = 512 nm, ε = 34,437 dm3·mol−1·cm−1, MP = 238–239 °C (dec.),

1H NMR (800 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 7.94 (d, J = 15.4 Hz, 2H), 7.22 (s, 4H), 7.07 (d, J = 15.5 Hz, 2H), 6.44 (s, 1H), 3.84 (s, 12H).

13C NMR (201 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 178.57, 148.19, 147.29, 140.49, 124.71, 118.19, 107.75, 101.10, 56.17.

Rf(ethyl acetate): 0.48, yield 84.5% dark burgundy amorphous solid.

(1E,4Z,6E)-5-((difluoroboranyl)oxy)-1,7-bis(2,4,6-trimethoxyphenyl)hepta-1,4,6-trien-3-one (8a) ESI [M + H]+ m/z 505.30, UV-Vis λmax = 525 nm, ε = 72,714 dm3·mol−1·cm−1, MP = 175–177 °C (dec.),

1H NMR (800 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 8.22 (d, J = 15.7 Hz, 2H), 7.15 (d, J = 15.7 Hz, 2H), 6.40 (s, 1H), 6.33 (s, 4H), 3.93 (s, 12H), 3.89 (s, 6H).

13C NMR (201 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 178.82, 164.98, 162.11, 136.39, 119.22, 105.39, 102.19, 91.24, 56.23, 55.83.

Rf(ethyl acetate): 0.72, yield 85.4% maroon amorphous solid.

(1E,4Z,6E)-5-((difluoroboranyl)oxy)-1,7-bis(3,5-dimethoxyphenyl)hepta-1,4,6-trien-3-one (9a) ESI [M + H]+ m/z 445.10, UV-Vis λmax = 453 nm, ε = 48,459 dm3·mol−1·cm−1, MP = 201–202 °C,

1H NMR (800 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.92 (d, J = 15.5 Hz, 2H), 6.71 (d, J = 2.1 Hz, 4H), 6.67 (d, J = 15.5 Hz, 2H), 6.55 (t, J = 2.1 Hz, 2H), 6.10 (s, 1H), 3.82 (s, 12H).

13C NMR (201 MHz, CDCl3) δ 180.18, 161.13, 147.60, 135.73, 121.02, 106.94, 104.29, 102.31, 55.51.

Rf(hexane/ethyl acetate 1:1): 0.72, yield 82.8% neon orange amorphous solid.

(1E,4Z,6E)-5-((difluoroboranyl)oxy)-1,7-bis(2,4-dimethoxyphenyl)hepta-1,4,6-trien-3-one (10a) ESI [M + H]+ m/z 445.10, UV-Vis λmax = 510 nm, ε = 48,459 dm3·mol−1·cm−1, MP = 181–182 °C (dec.),

1H NMR (800 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.23 (d, J = 15.6 Hz, 2H), 7.51 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 2H), 6.75 (d, J = 15.6 Hz, 2H), 6.54 (dd, J = 8.6, 2.3 Hz, 2H), 6.45 (d, J = 2.3 Hz, 2H), 5.99 (s, 1H), 3.91 (s, 6H), 3.87 (s, 6H).

13C NMR (201 MHz, CDCl3) δ 179.59, 164.18, 161.17, 142.39, 132.07, 118.72, 116.82, 105.98, 101.48, 98.40, 55.59.

Rf(ethyl acetate): 0.83, yield 87.4% dark purple amorphous solid.

(1E,4Z,6E)-5-hydroxy-1,7-bis(3-bromo-4-hydroxy-5-methoxyphenyl)-hepta-1,4,6-trien-3-one (1b) ESI [M + H]+ m/z 526.95, UV-Vis λmax = 414 nm, ε = 53,058 dm3·mol−1·cm−1, MP = 234–235 °C (dec.),

1H NMR (800 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 16.27 (s, 1H), 10.08 (s, 2H), 7.54 (s, 2H), 7.52 (d, J = 2.0 Hz, 2H), 7.38 (d, J = 1.8 Hz, 2H), 6.88 (d, J = 15.8 Hz, 2H), 6.06 (s, 1H), 3.90 (s, 6H).

13C NMR (201 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 183.09, 148.50, 145.96, 139.41, 127.18, 125.56, 122.66, 110.44, 109.56, 101.36, 56.37.

Rf(ethyl acetate): 0.91, yield 41.1% orange amorphous solid.

(1E,4Z,6E)-5-hydroxy-1,7-bis(3-bromo-4-(2-hydroxyethoxy)-5-methoxyphenyl)-hepta-1,4,6-trien-3-one (2b) ESI [M − H]− m/z 612.99, UV-Vis λmax = 403 nm, ε = 58,156 dm3·mol−1·cm−1, MP = 107–108 °C,

1H NMR (800 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 16.08 (s, 1H), 7.60 (d, J = 1.7 Hz, 2H), 7.57 (d, J = 15.8 Hz, 2H), 7.45 (d, J = 1.8 Hz, 2H), 7.00 (d, J = 15.9 Hz, 2H), 6.13 (s, 1H), 4.74 (s, 2H), 4.00 (t, J = 5.5 Hz, 4H), 3.89 (s, 6H), 3.70 (t, J = 5.3 Hz, 4H).

13C NMR (201 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 183.06, 153.41, 146.61, 138.87, 131.95, 124.78, 124.66, 117.25, 112.02, 101.93, 74.53, 60.23, 56.33.

Rf(ethyl acetate): 0.76, yield 38.7% light orange amorphous solid.

(1E,4Z,6E)-5-hydroxy-1,7-bis(3-bromo-4,5-dimethoxyphenyl)-hepta-1,4,6-trien-3-one (3b) ESI [M + H]+ m/z 554.98, UV-Vis λmax = 402 nm, ε = 49,437 dm3·mol−1·cm−1, MP = 145–147 °C,

1H NMR (800 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 16.07 (s, 1H), 7.59 (d, J = 1.9 Hz, 2H), 7.56 (d, J = 15.9 Hz, 2H), 7.45 (d, J = 1.9 Hz, 2H), 6.99 (d, J = 15.9 Hz, 2H), 6.12 (s, 1H), 3.88 (s, 6H), 3.76 (s, 6H).

13C NMR (201 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 183.06, 153.54, 147.16, 138.83, 132.23, 124.91, 124.54, 117.08, 112.08, 101.97, 60.24, 56.30.

Rf(hexane/ethyl acetate 2:1): 0.66, yield 45.3% yellow amorphous solid.

(1E,4Z,6E)-5-hydroxy-1,7-bis(2-bromo-5-hydroxy-4-methoxyphenyl)-hepta-1,4,6-trien-3-one (4b) ESI [M + H]+ m/z 527.00, UV-Vis λmax = 417 nm, ε = 43,399 dm3·mol−1·cm−1, MP = 242–245 °C,

1H NMR (800 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 7.77 (d, J = 15.7 Hz, 2H), 7.32 (s, 2H), 7.22 (s, 2H), 6.74 (d, J = 15.6 Hz, 2H), 6.14 (s, 1H), 3.85 (s, 6H).

13C NMR (201 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 182.70, 150.73, 146.46, 137.81, 125.95, 124.21, 115.94, 115.03, 113.50, 102.63, 56.12.

Rf(hexane/ethyl acetate 1:1): 0.19, yield 89.6% orange amorphous solid.

(1E,4Z,6E)-5-hydroxy-1,7-bis(3-bromo-4-(3-hydroxypropoxy)-5-methoxyphenyl)-hepta-1,4,6-trien-3-one (5b) ESI [M + H]+ m/z 643.2, UV-Vis λmax = 404 nm, ε = 49,188 dm3·mol−1·cm−1, MP = 134–135 °C,

1H NMR (800 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 16.08 (s, 1H), 7.60 (d, J = 1.8 Hz, 2H), 7.57 (d, J = 15.8 Hz, 2H), 7.45 (d, J = 1.9 Hz, 2H), 7.00 (d, J = 15.9 Hz, 2H), 6.13 (s, 1H), 4.47 (s, 2H), 4.06 (t, J = 6.5 Hz, 4H), 3.89 (s, 6H), 3.59 (t, J = 6.3 Hz, 4H), 1.86 (p, J = 6.5 Hz, 4H).

13C NMR (201 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 183.06, 153.48, 146.54, 138.87, 131.90, 124.76, 124.66, 117.24, 112.03, 101.92, 70.65, 57.65, 56.31, 33.18.

Rf(ethyl acetate): 0.39, yield 74.7% light orange amorphous solid.

(1E,4Z,6E)-5-hydroxy-1,7-bis(3,4,5-trimethoxyphenyl)-hepta-1,4,6-trien-3-one (6b) ESI [M + H]+ m/z 457.10, UV-Vis λmax = 410 nm, ε = 45,517 dm3·mol−1·cm−1, MP = 183–184 °C,

1H NMR (800 MHz, CDCl3) δ 15.91 (s, 1H), 7.58 (d, J = 15.7 Hz, 2H), 6.79 (s, 4H), 6.53 (d, J = 15.7 Hz, 2H), 5.86 (s, 1H), 3.91 (s, 12H), 3.89 (s, 6H).

13C NMR (201 MHz, CDCl3) δ 183.11, 153.48, 140.60, 140.14, 130.52, 123.40, 105.33, 101.53, 61.01, 56.20.

Rf(hexane/ethyl acetate 2:1): 0.4, yield 54.8% orange amorphous solid.

(1E,4Z,6E)-5-hydroxy-1,7-bis(4-hydroxy-3,5-dimethoxyphenyl)-hepta-1,4,6-trien-3-one (7b) ESI [M + H]+m/z 429.10, UV-Vis λmax = 426 nm, ε = 58,833 dm3·mol−1·cm−1, M.p. = 115–116 °C,

1H NMR (800 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 16.36 (s, 1H), 9.02 (s, 3H), 7.56 (d, J = 15.7 Hz, 2H), 7.04 (s, 4H), 6.80 (d, J = 15.8 Hz, 2H), 6.08 (s, 1H), 3.82 (s, 12H).

13C NMR (201 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 183.15, 148.11, 141.03, 138.40, 125.12, 121.49, 106.28, 100.75, 56.09.

Rf(hexane/ethyl acetate 1:1): 0.19, yield 48.0% black-purple amorphous solid.

(1E,4Z,6E)-5-hydroxy-1,7-bis(2,4,6-trimethoxyphenyl)-hepta-1,4,6-trien-3-one (8b) ESI [M + H]+m/z 457.10, UV-Vis λmax = 431 nm, ε = 58,515 dm3·mol−1·cm−1, M.p. = 195–196 °C,

1H NMR (800 MHz, CDCl3) δ 16.41 (s, 1H), 8.05 (d, J = 16.1 Hz, 2H), 6.99 (d, J = 16.1 Hz, 2H), 6.12 (s, 4H), 5.78 (s, 1H), 3.88 (s, 12H), 3.85 (s, 6H).

13C NMR (201 MHz, CDCl3) δ 184.74, 162.53, 161.21, 130.94, 124.47, 106.75, 101.55, 90.55, 55.74, 55.38.

Rf(hexane/ethyl acetate 2:1): 0.33, yield 57.0% orange amorphous solid.

(1E,4Z,6E)-5-hydroxy-1,7-bis(3,5-dimethoxyphenyl)-hepta-1,4,6-trien-3-one (9b) ESI [M + H]+m/z 397.10, UV-Vis λmax = 394 nm, ε = 41,030 dm3·mol−1·cm−1, M.p. = 143–145 °C,

1H NMR (800 MHz, CDCl3) δ 15.82 (s, 1H), 7.58 (d, J = 15.8 Hz, 2H), 6.70 (d, J = 2.1 Hz, 4H), 6.59 (d, J = 15.8 Hz, 2H), 6.50 (t, J = 2.2 Hz, 2H), 5.85 (s, 1H), 3.83 (s, 12H).

13C NMR (201 MHz, CDCl3) δ 183.20, 161.05, 140.65, 136.88, 124.58, 106.04, 102.43, 101.80, 55.45.

Rf(hexane/ethyl acetate 2:1): 0.73, yield 87.4% yellow amorphous solid.

(1E,4Z,6E)-5-hydroxy-1,7-bis(2,4-dimethoxyphenyl)-hepta-1,4,6-trien-3-one (10b) ESI [M + H]+m/z 397.00, UV-Vis λmax = 425 nm, ε = 51,918 dm3·mol−1·cm−1, M.p. = 147–148 °C,

1H NMR (800 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 16.41 (s, 1H), 7.80 (d, J = 16.0 Hz, 2H), 7.67 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 2H), 6.78 (d, J = 15.9 Hz, 2H), 6.63 (d, J = 2.4 Hz, 2H), 6.61 (dd, J = 8.6, 2.4 Hz, 2H), 6.00 (s, 1H), 3.89 (s, 6H), 3.83 (s, 6H).

13C NMR (201 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 183.33, 162.71, 159.52, 134.74, 129.79, 121.65, 115.99, 106.37, 101.32, 98.37, 55.77, 55.51.

Rf(hexane/ethyl acetate 2:1): 0.57, yield 58.8% dark orange amorphous solid.

3.3. HPLC Purity and Chromatographic Conditions for Determining the Purity of the Tested Compounds

All analyses were performed using an Agilent 1260 Infinity II LC System coupled to a diode array detector (DAD WR, model G7115A) (Agilent Technologies, Böblingen, Germany). Chromatographic separation was conducted at 25 °C in gradient mode, using a reverse phase column (Luna® C18(2), 100 Å, 150 × 4.6 mm ID, 5 µm; Phenomenex, Torrance, CA, USA) as the stationary phase, at a flow rate of 1.0 mL/min. The mobile phase consisted of 0.1% formic acid in water (Solvent A) and acetonitrile (Solvent B). The gradient elution program was as follows: 0–10.0 min (90–70% B), 10.0–13.0 min (70–50% B), and 13.0–15.0 min (50–90% B). Acetonitrile was used as a wash solvent between injections. For each analysis, 10.0 μL of sample was injected using an autosampler maintained at 25 °C. The total run time was 15.0 min per sample. The DAD detection wavelength was individually adjusted to the absorption maximum of each compound. The gradient conditions are reported in Table 4. The determined purity of all new compounds exceeded the value of 95.0% (Table S8 of Supplementary Materials).

Table 4.

HPLC gradient used for the analysis of a newly synthesized compound.

3.4. Single Crystal X-Ray Diffraction Studies

Crystals of (1E,4Z,6E)-5-((difluoroboranyl)oxy)-1,7-bis(2,4,6-trimethoxyphenyl)hepta-1,4,6-trien-3-one were grown from DMF by slow evaporation technique. Reflection intensities were collected with Oxford Diffraction Xcalibur diffractometer using graphite-monochromated MoKα radiation, at 100,0(1)K. Data were processed with the Agilent Technologies CrysAlis Pro 1.171.43.93a software. The structures were solved by direct methods (Olex2 [22]) and refined by the full-matrix least-squares techniques based on F2 with SHELXL [23]. All non-H atoms were refined anisotropically. Hydrogen atoms were placed at calculated positions and refined using a riding model. Interpretation of the results has been performed using SHELXTL [23] and Mercury [24] programs. The crystal and refinement data are given in Table 2. The CIFs files have been deposited with the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre (www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk, deposition date 16 may 2025) CCDC 2451690.

3.5. Biological Studies

3.5.1. MTT Assay for Measuring Cell Viability

The sensitivity of tumor and pseudo-normal cells to the studied compounds was evaluated using the MTT (3-[4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl]-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide) test (Sigma-Aldrich, USA). The 3500–4000 adherent or 15,000 suspension cells per well were seeded in 96-well plates according to ATCC recommendations in 100 μL DMEM or RPMI-1640 complete medium (Sigma-Aldrich, Burlington, MA, USA), and incubated for 72 h at 37 °C in a CO2 incubator with the studied compounds. After incubation, MTT reagents were added to the cells in accordance with the manufacturer’s recommendation and incubated for the next 4 h. Crystals of formazan were dissolved in dimethylsulfoxide, and the reaction absorbance was measured by an Absorbance Reader BioTek ELx800 (BioTek Instruments, Inc., Winooski, VT, USA). The half maximal inhibitory concentration value (IC50) was calculated by GraphPad Prism 8 software (San Diego, CA, USA) [25].

3.5.2. The Fluorescent Microscopy of HCT-116 Cells

The HCT-116 cells were seeded in 24-well plates at 50,000 cells/mL and then allowed to adhere overnight. After, cells were treated for 24 h with compounds (1 μM) and doxorubicin (0.5 μM). Cells were stained with 0.2–0.5 μg/mL of Hoechst-33342 and 1 μg/mL of EtBr. The fluorescent microscope (LIM-400, LABEX INSTRUMENT Limited, NingBo, China), MTR3CCD camera, and Image View analysis software were used for HCT-116 cells examination [25]. The fluorescence of EtBr was measured with the microplate reader (Varioskan LUX, Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) at 520 nm excitation and 600 nm emission wavelength. The results were presented as a percentage of the non-treated cells, which served as the control. Data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism 8 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). The experiments were performed in triplicate. One-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s test was used for statistical analysis. A p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3.5.3. Methyl Green Displacement Assay

An aliquot of salmon sperm DNA (485 μL; 50 μg/mL) was incubated with 15 μL of methyl green solution (1 mg/mL) at 37 °C for 1 h. Subsequently, 500 μL of the tested compounds, doxorubicin, or ethidium bromide (each at final concentrations of 1 μM and 10 μM) were added to the preformed DNA–methyl green complex. The samples were further incubated at 37 °C for 2 h in the dark. Absorbance was then recorded at 630 nm. Data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism 8 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). The experiments were performed in triplicate. One-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s test was used for statistical analysis. A p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3.5.4. DHE Staining of HCT-116 Cells

The HCT-116 cells were seeded in 96-well plates at 5000 cells/mL and then allowed to adhere overnight. After, cells were treated for 24 h with compounds (1 μM) and doxorubicin (0.5 μM). Cells were stained with 10 μM DHE for 30 min [21]. The fluorescence was measured with the microplate reader (Varioskan LUX, Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) at 495 nm excitation and 617 nm emission wavelength. The results were presented as a percentage of the non-treated cells, which served as the control. Data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism 8 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). The experiments were performed in triplicate. One-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s test was used for statistical analysis. A p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3.5.5. Diphenylamine Assay

DNA fragmentation was quantified using the diphenylamine assay. HCT-116 cells were exposed for 72 h to the tested compounds at concentrations of 1 µM and doxorubicin at 0.5 µM. Following treatment, cells were lysed in 0.5 mL of Tris–EDTA buffer (pH 7.4) containing 0.2% Triton X-100 and centrifuged at 12,000× g for 10 min at 4 °C. The supernatant containing fragmented DNA (fraction “B”) was transferred to a separate tube, while the pellet containing intact chromatin was designated as fraction “A”. Both fractions received 0.5 mL of 25% trichloroacetic acid (Sfera Sim, Lviv, Ukraine), were mixed, and incubated for 1 h at 56 °C, followed by centrifugation at 14,000× g for 10 min at 4 °C. The resulting pellets (“A” and “B”) were treated with 1 mL of freshly prepared diphenylamine reagent (150 mg diphenylamine [Sigma-Aldrich] dissolved in 10 mL glacial acetic acid, 150 mL concentrated H2SO4, and 50 mL acetaldehyde solution, all from SferaSim, Lviv, Ukraine) and incubated overnight at 37 °C [26].

Absorbance was recorded at 630 nm using a BioTek ELx800 Absorbance Reader (BioTek Instruments, Winooski, VT, USA). DNA fragmentation (%) was calculated as: OD(B)/[OD(A) + OD(B)] × 100%. Data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism 8 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). The experiments were performed in triplicate. One-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s test was used for statistical analysis. A p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

4. Conclusions

This work presents a series of BF2, bromine, and methoxy-modified curcumin derivatives, which were subjected to physicochemical and biological studies. The cytotoxicity tests performed on the series of compounds allowed us to select the most active molecules. It was demonstrated that the cytotoxic activities of the obtained derivatives could be increased by inserting the BF2 moiety into their chemical structures. In general, the presence of the BF2 moiety is crucial for increased cytotoxic activity. Bromine substituent influence is specific to the cell line. For high activity, the preferred configuration is “isocurcumin” with a free hydroxyl group and bromine in the meta position and a methoxyl group in the para position. As such, future modifications should be focused primarily on the central part of the molecule, such as the alkyl chain or the diketone moiety. Interestingly, in the case of derivatives 2a/2b and 5a/5b, no significant increase in activity was observed after the introduction of this moiety, which may suggest active metabolites in potential therapeutic applications. It is also worth noting that none of the derivatives obtained show significantly higher cytotoxicity towards normal cells compared to natural curcumin. In general, compounds 2a, 6a, and 9a show the best activity, which makes those interesting lead compounds for further research. Compounds Cur, 5b, 6a, 6b, Cur-BF2, and 9a interact with DNA through intercalation. These compounds elevated cellular ROS in treated HCT-116 cells.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/molecules30234609/s1.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: M.W. and E.P.; methodology: M.W. and R.L.; validation: M.W. and R.L.; formal analysis: E.P., D.Ł., A.K., N.F., Y.K., I.I. and R.S.; investigation:, E.P., Ł.P., A.K., D.Ł., J.M., A.G.-K., A.Z.-G., N.F., Y.K., I.I., J.K. and R.S.; resources: M.W. and R.L.; data curation: M.W. and R.L.; writing—original draft preparation: E.P., D.Ł, G.K., K.C.-W. and M.W.; writing—review and editing: E.P., M.W. and R.L.; visualization: E.P., D.Ł., N.F., Y.K., I.I. and R.S.; supervision: M.W. and R.L.; project administration: M.W.; funding acquisition: R.L. and K.C.-W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Eduard Potapskyi is a participant of the STER Internationalisation of Doctoral Schools Programme from NAWA Polish National Agency for Academic Exchange No. PPI/STE/2020/1/00014/DEC/02. Research was partially supported by the National Research Foundation of Ukraine (project No. 2023.03/0104) as well as by the National Science Center of Poland (grant No. 2019/35/B/NZ7/01165).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors are sincerely grateful to Robert Kralovics for the Ba/F3 cell lines provided for research. The authors would like to thank Jon Facer for his meticulous language editing and proofreading of this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Kuzminska, J.; Szyk, P.; Mlynarczyk, D.T.; Bakun, P.; Muszalska-Kolos, I.; Dettlaff, K.; Sobczak, A.; Goslinski, T.; Jelinska, A. Curcumin Derivatives in Medicinal Chemistry: Potential Applications in Cancer Treatment. Molecules 2024, 29, 5321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zintle, M.; Khwaza, V.; Blessing, A.A. Curcumin and Its Derivative agents in Prostate, Colon and Breast Cancers. Molecules 2019, 24, 4386–4409. [Google Scholar]

- Idoudi, S.; Bedhiafi, T.; Hijji, Y.M.; Billa, N. Curcumin and Derivatives in Nanoformulations with Therapeutic Potential on Colorectal Cancer. AAPS PharmSciTech 2022, 23, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karatayli, E.; Sadiq, S.C.; Schattenberg, J.M.; Grabbe, S.; Biersack, B.; Kaps, L. Curcumin and Its Derivatives in Hepatology: Therapeutic Potential and Advances in Nanoparticle Formulations. Cancers 2025, 17, 484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mari, M.; Carrozza, D.; Ferrari, E.; Asti, M. Applications of radiolabelled curcumin and its derivatives in medicinal chemistry. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 7410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazewski, D.; Kucinska, M.; Potapskiy, E.; Kuzminska, J.; Popenda, L.; Tezyk, A.; Goslinski, T.; Wierzchowski, M.; Murias, M. Enhanced Cytotoxic Activity of PEGylated Curcumin Derivatives: Synthesis, Structure–Activity Evaluation, and Biological Activity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomeh, M.A.; Hadianamrei, R.; Zhao, X. A review of curcumin and its derivatives as anticancer agents. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komal, K.; Chaudhary, S.; Yadav, P.; Pramanik, R.; Singh, M. The therapeutic and preventive efficacy of curcumin and its derivatives in esophageal cancer. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2019, 20, 1329–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Alhasawi, M.A.I.; Aatif, M.; Muteeb, G.; Alam, M.W.; El Oirdi, M.; Farhan, M. Curcumin and Its Derivatives Induce Apoptosis in Human Cancer Cells by Mobilizing and Redox Cycling Genomic Copper Ions. Molecules 2022, 27, 7410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abadi, A.J.; Mirzaei, S.; Mahabady, M.K.; Hashemi, F.; Zabolian, A.; Hashemi, F.; Raee, P.; Aghamiri, S.; Ashrafizadeh, M.; Aref, A.R.; et al. Curcumin and its derivatives in cancer therapy: Potentiating antitumor activity of cisplatin and reducing side effects. Phytother. Res. 2022, 36, 189–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, K.; Al-Khazaleh, A.K.; Bhuyan, D.J.; Li, F.; Li, C.G. A Review of Recent Curcumin Analogues and Their Antioxidant, Anti-Inflammatory, and Anticancer Activities. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Chen, J.; Chojnacki, J.; Zhang, S. BF3·OEt2-promoted concise synthesis of difluoroboron-derivatized curcumins from aldehydes and 2,4-pentanedione. Tetrahedron Lett. 2013, 54, 2070–2073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abonia, R.; Laali, K.K.; Somu, D.R.; Bunge, S.D.; Wang, E.C. A Flexible Strategy for Modular Synthesis of Curcuminoid-BF2/Curcuminoid Pairs and Their Comparative Antiproliferative Activity in Human Cancer Cell Lines. ChemMedChem 2020, 15, 354–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laali, K.K.; Rathman, B.M.; Bunge, S.D.; Qi, X.; Borosky, G.L. Fluoro-curcuminoids and curcuminoid-BF2 adducts: Synthesis, X-ray structures, bioassay, and computational/docking study. J. Fluor. Chem. 2016, 191, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.Y.; Kang, Y.Y.; Kim, E.J.; Ahn, J.-H.; Mok, H. Effects of curcumin-/boron-based compound complexation on antioxidant and antiproliferation activity. Appl. Biol. Chem. 2018, 61, 403–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potapskyi, E.; Kustrzyńska, K.; Łażewski, D.; Skupin-Mrugalska, P.; Lesyk, R.; Wierzchowski, M. Introducing bromine to the molecular structure as a strategy for drug design. J. Med. Sci. 2024, 93, e1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagargoje, A.A.; Deshmukh, T.R.; Shaikh, M.H.; Khedkar, V.M.; Shingate, B.B. Anticancer perspectives of monocarbonyl analogs of curcumin: A decade (2014–2024) review. Arch. Pharm. 2024, 357, e2400197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatamipour, M.; Hadizadeh, F.; Jaafari, M.R.; Khashyarmanesh, Z.; Sathyapalan, T.; Sahebkar, A. Anti-Proliferative Potential of Fluorinated Curcumin Analogues: Experimental and Computational Analysis and Review of the Literature. Curr. Med. Chem. 2022, 29, 1459–1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, T.A.; Koko, W.S.; Al Nasr, I.S.; Schobert, R.; Biersack, B. Activity of Fluorinated Curcuminoids against Leishmania major and Toxoplasma gondii Parasites. Chem. Biodivers. 2021, 18, e2100381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuźmińska, J.; Kobyłka, P.; Wierzchowski, M.; Łażewski, D.; Popenda, Ł.; Szubska, P.; Jankowska, W.; Jurga, S.; Goslinski, T.; Muszalska-Kolos, I.; et al. Novel fluorocurcuminoid-BF2 complexes and their unlocked counterparts as potential bladder anticancer agents—synthesis, physicochemical characterization, and in vitro anticancer activity. J. Mol. Struct. 2023, 1283, 135269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Gullapalli, R.R. High Throughput Screening Assessment of Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) Generation using Dihydroethidium (DHE) Fluorescence Dye. J. Vis. Exp. 2024, 203, e66238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dolomanov, O.V.; Bourhis, L.J.; Gildea, R.J.; Howard, J.A.K.; Puschmann, H. OLEX2: A complete structure solution, refinement and analysis program. J. Appl. Cryst. 2009, 42, 339–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldrick, G.M. Crystal structure refinement with SHELXL. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. C Struct. Chem. 2015, 71, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macrae, C.F.; Bruno, I.J.; Chisholm, J.A.; Edgington, P.R.; McCabe, P.; Pidcock, E.; Rodriguez-Monge, L.; Taylor, R.; Van De Streek, J.; Wood, P.A. Mercury CSD 2.0—New features for the visualization and investigation of crystal structures. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2008, 41, 466–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivasechko, I.; Lozynskyi, A.; Senkiv, J.; Roszczenko, P.; Kozak, Y.; Finiuk, N.; Klyuchivska, O.; Kashchak, N.; Manko, N.; Maslyak, Z.; et al. Molecular design, synthesis and anticancer activity of new thiopyrano [2,3-d] thiazoles based on 5-hydroxy-1,4-naphthoquinone (juglone). Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2023, 252, 115304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, S.; Tandon, S. DNA fragmentation and cell cycle arrest: A hallmark of apoptosis induced by Ruta graveolens in human colon cancer cells. Homeopathy 2015, 104, 36–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).