Biosynthesis of Silver Nanoparticles Using Tagetes erecta: Extract Characterization, Morphological Modification Using Structure Directing or Heterogeneous Nucleating Agents, and Antibacterial Evaluation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Extract Characterization

2.1.1. Phytochemical Screening of TEE

2.1.2. TEE UPLC-Qtof-MS/MS Profile

2.2. AgNP Characterization

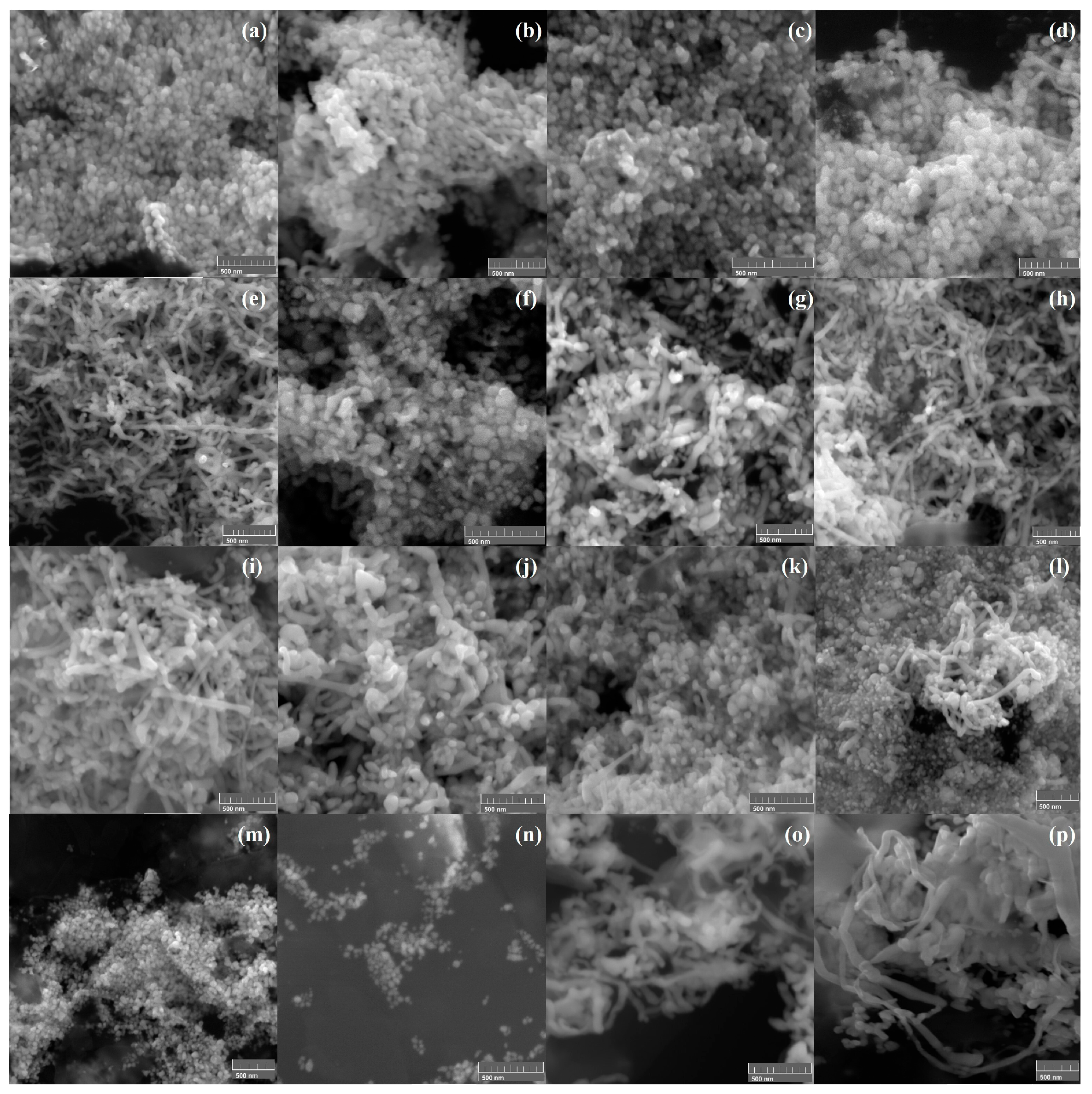

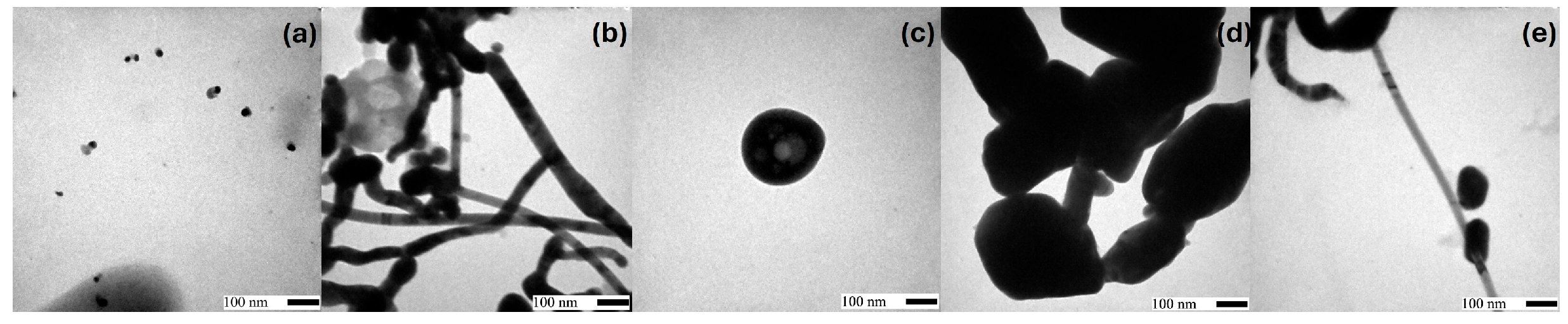

2.2.1. Morphology

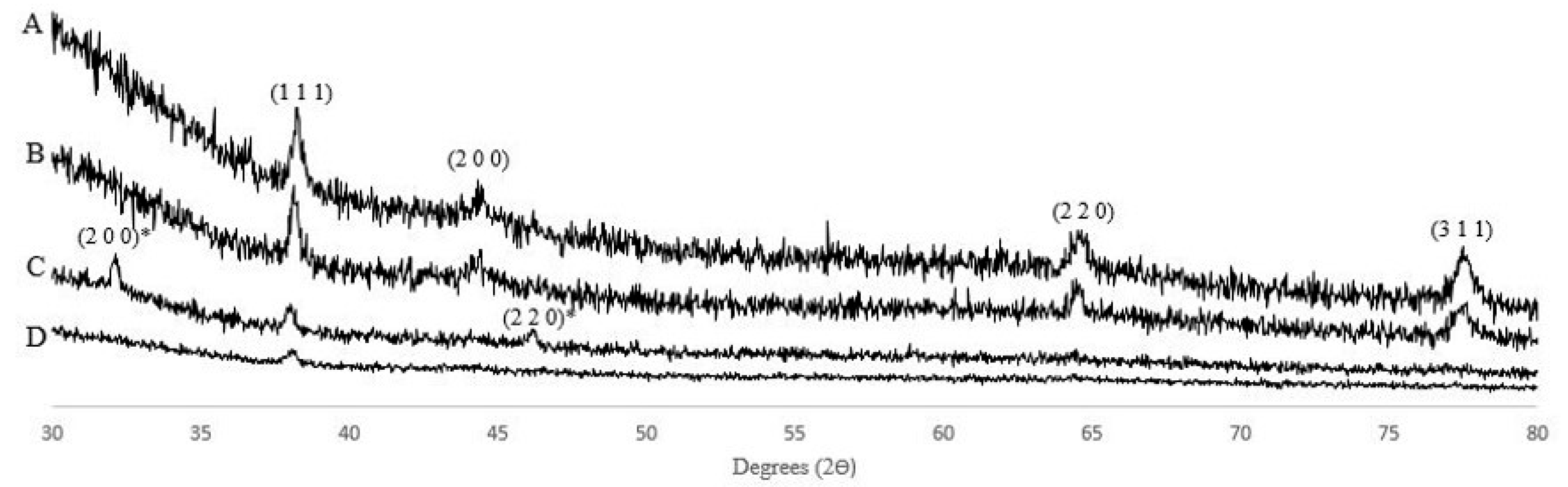

2.2.2. Crystal Structure

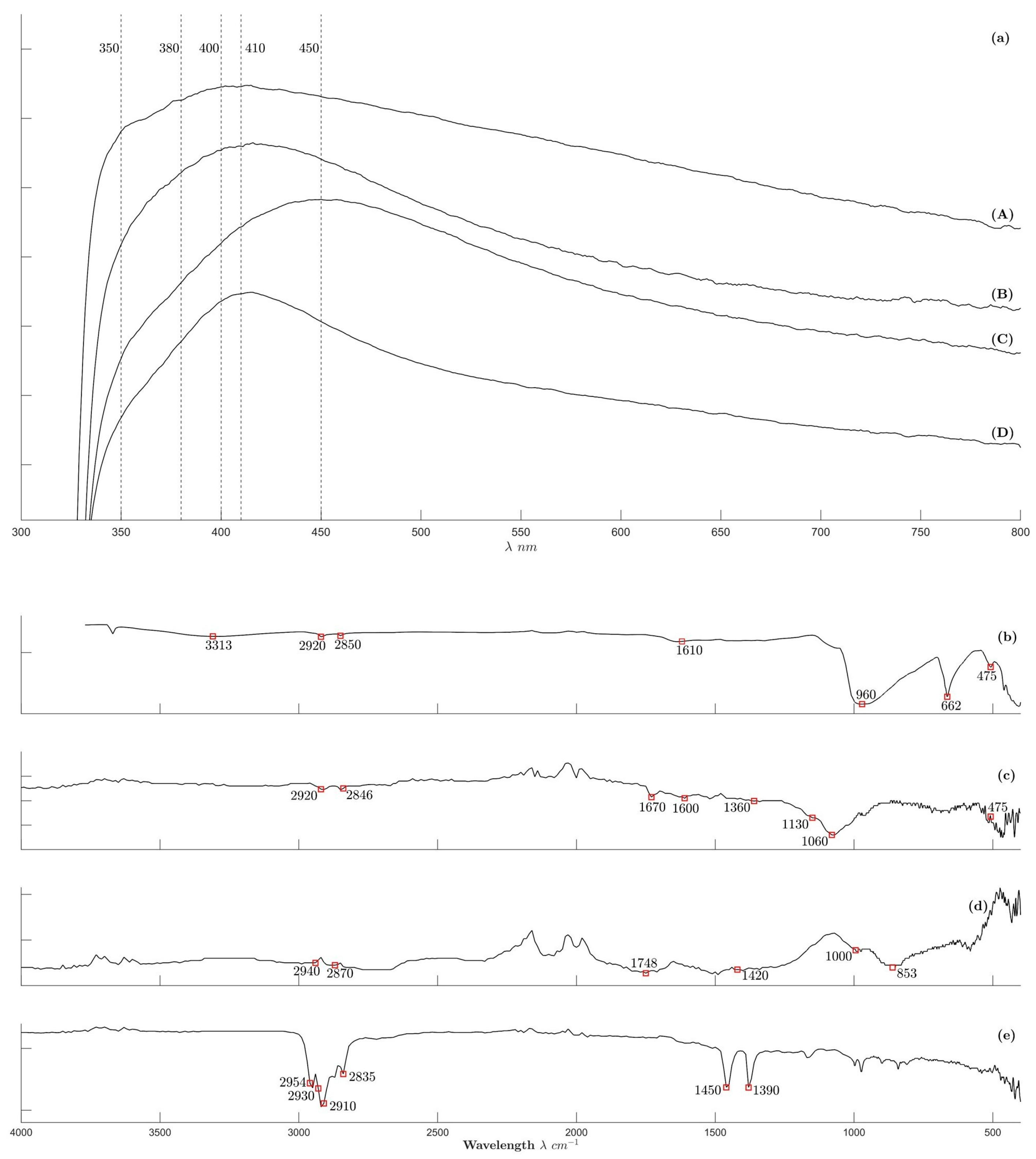

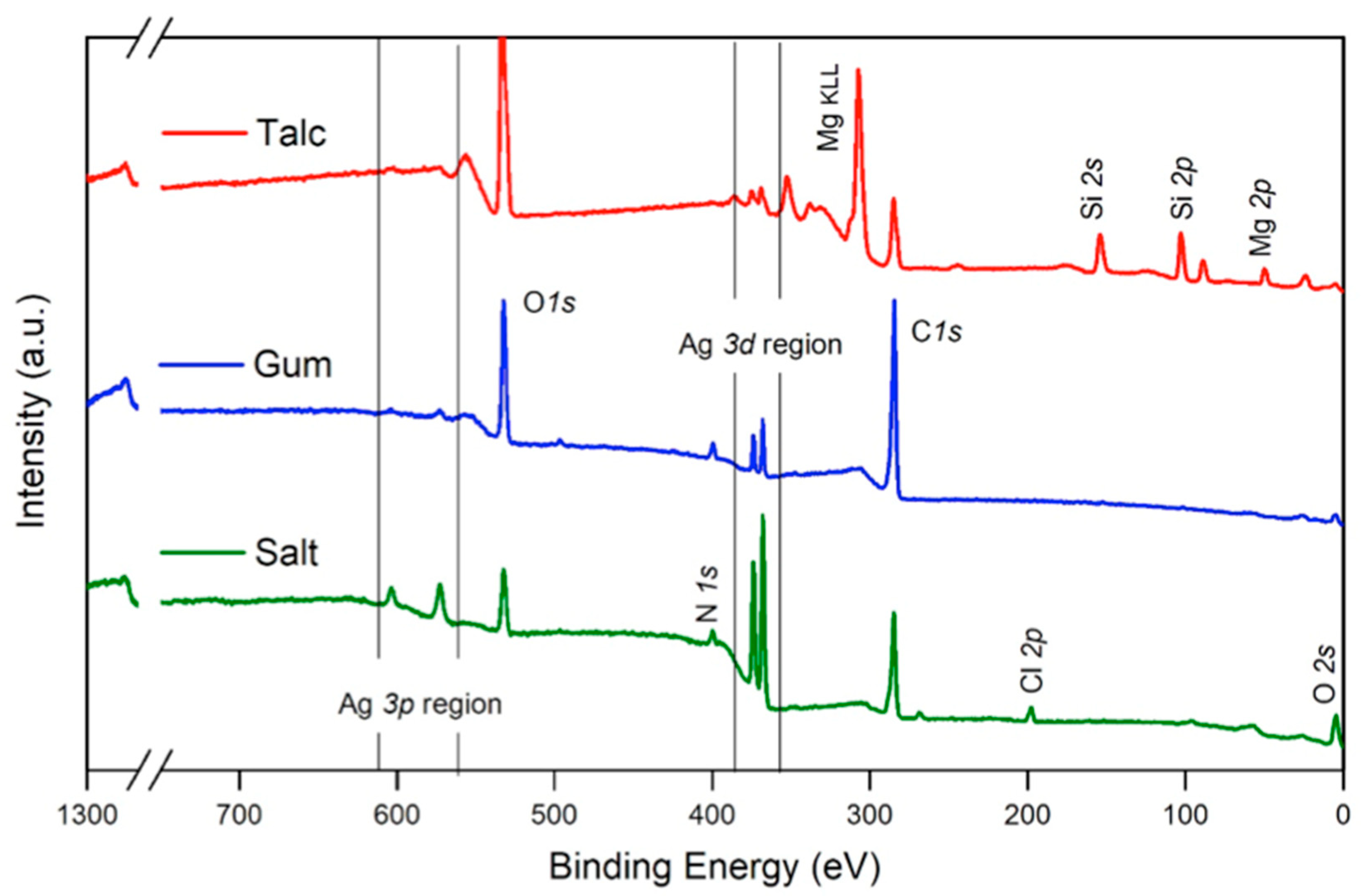

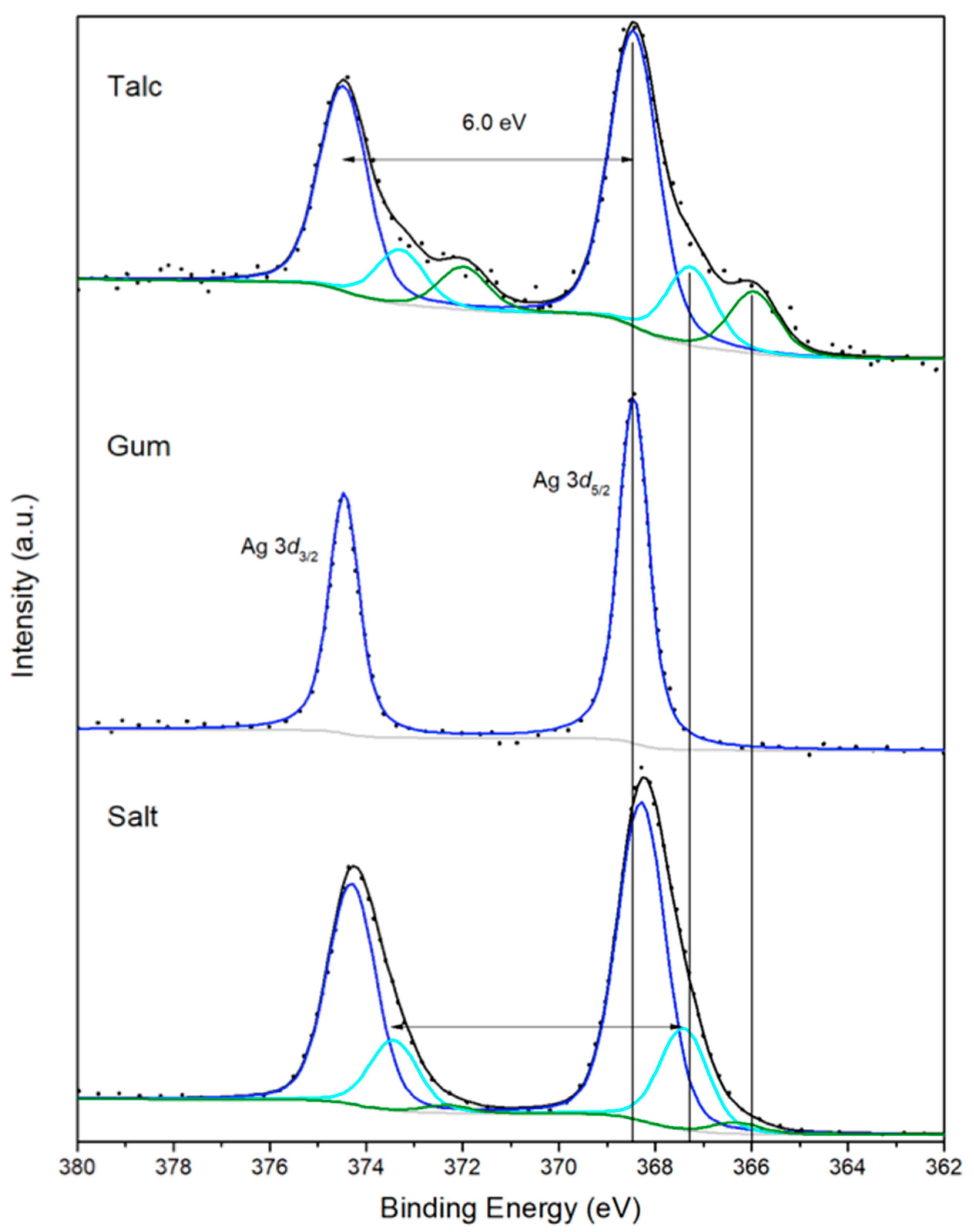

2.2.3. Spectroscopic Analysis Results Are Shown in Figure 4

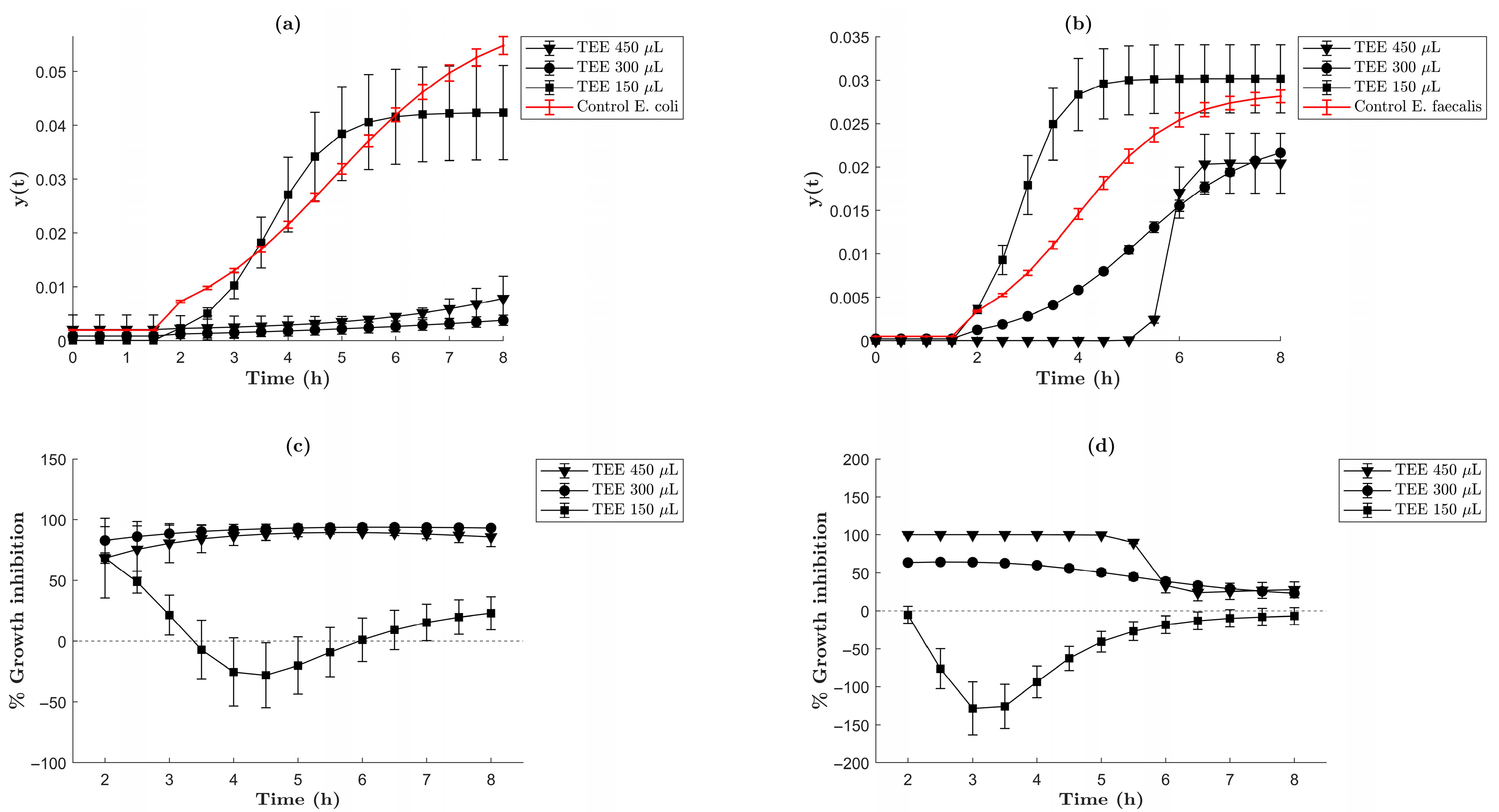

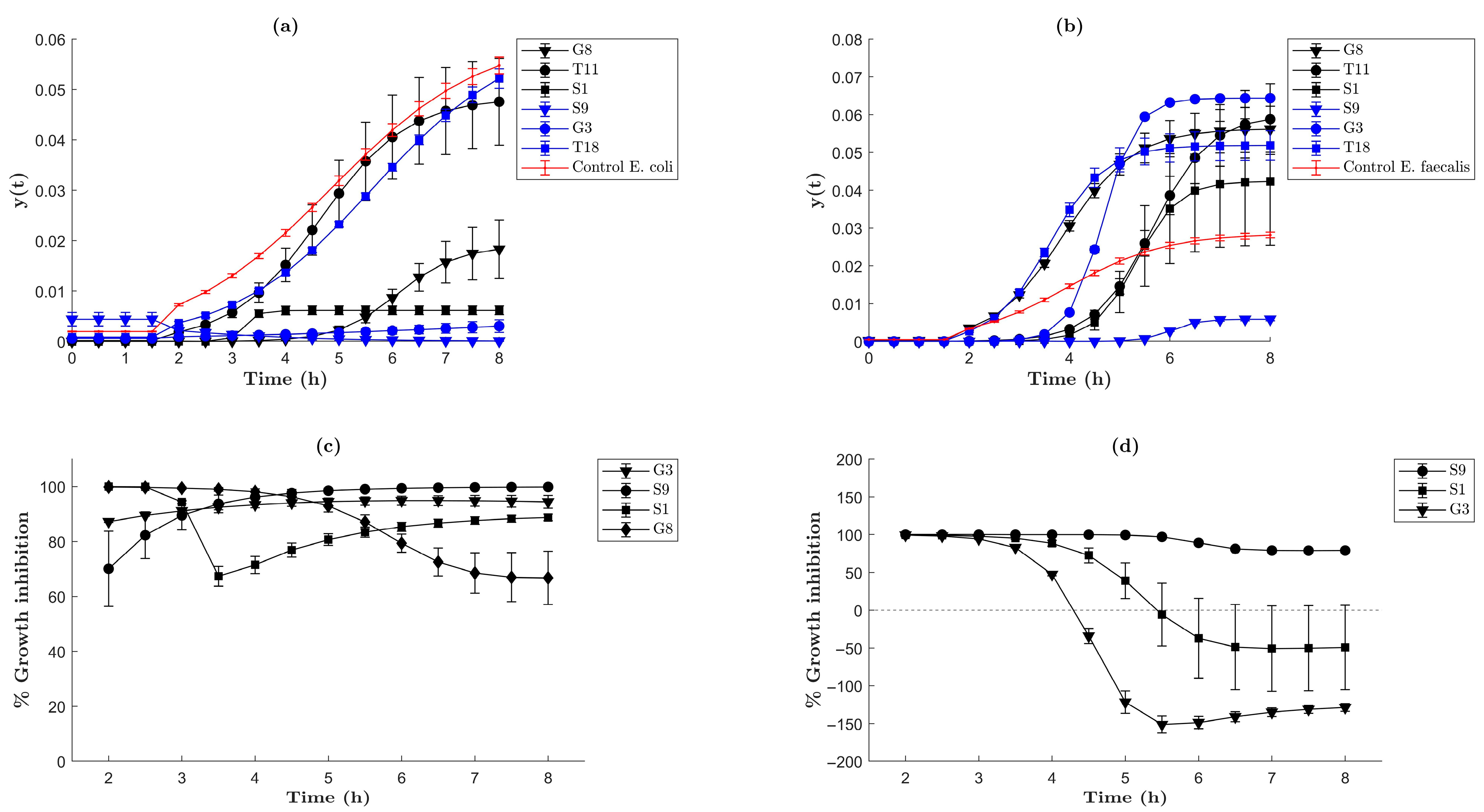

2.3. Antibacterial Activity

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials

3.2. TEE Preparation

3.3. Synthesis of AgNPs

3.4. Phytochemical Screening of TEE

3.4.1. Saponins

Hot Water Test

Rosenthaler Assay

3.4.2. Triterpenes

3.4.3. Tannins

3.4.4. Flavonoids

Ammonia Vapors

Shinoda

NaOH Assay

3.4.5. Coumarins

3.4.6. Quantification of Reducing Sugars in TEE

3.4.7. Quantification of Fe2+ in TEE

3.5. TEE UPLC-Qtof-MS/MS Profile

3.6. AgNP Characterization

3.7. Antibacterial Activity

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gómez-Acosta, A.; Manzano-Ramírez, A.; López-Naranjo, E.J.; Apatiga, L.M.; Herrera-Basurto, R.; Rivera-Muñoz, E.M. Silver nanostructure dependence on the stirring-time in a high-yield polyol synthesis using a short-chain PVP. Mat. Lett. 2015, 138, 167–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padalia, H.; Moteriya, P.; Chanda, S. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles from marigold flower and its synergistic antimicrobial potential. Arab. J. Chem. 2015, 8, 732–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.; Ahmad, M.; Swami, B.L.; Ikram, S. A review on plants extract mediated synthesis of silver nanoparticles for antimicrobial applications: A green expertise. J. Adv. Res. 2016, 7, 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lomelí-Rosales, D.A.; Zamudio-Ojeda, A.; Reyes-Maldonado, O.K.; López-Reyes, M.E.; Basulto-Padilla, G.C.; López-Naranjo, E.J.; Zuñiga-Mayo, V.M.; Velázquez-Juárez, G. Green synthesis of gold and silver nanoparticles using leaf extract of Capsicum chinense plant. Molecules 2022, 27, 1692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafique, M.; Sadaf, I.; Rafique, M.S.; Tahir, M.B. A review on green synthesis of silver nanoparticles and their applications. Artif. Cells Nanomed. Biotechnol. 2016, 45, 1272–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Wu, W.; Jing, X.; Huang, J.; Sun, D.D.; Odoom-Wubah, T.; Liu, H.; Wang, H.; Li, Q. Trisodium citrate-assisted biosynthesis of silver nanoflowers by Canarium album foliar broths as a platform for SERS detection. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2013, 52, 5085–5094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logaranjan, K.; Jaculin Raiza, A.; Gopinath, S.C.B.; Chen, Y.; Pandian, K. Shape- and size-controlled synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Aloe vera plant extract and their antimicrobial activity. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2016, 11, 520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smirnov, O.; Dzhagan, V.; Kovalenko, M.; Gudymenko, O.; Dzhagan, V.; Mazur, N.; Isaieva, O.; Maksimenko, Z.; Kondratenko, S.; Skoryk, M.; et al. ZnO and AgNP-decorated ZnO nanoflowers: Green synthesis using Ganoderma lucidum aqueous extract and characterization. RSC Adv. 2023, 13, 756–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katta, V.K.M.; Dubey, R.S. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Tagetes erecta plant and investigation of their structural, optical, chemical and morphological properties. Mater. Today Proc. 2021, 45, 794–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maji, A.; Beg, M.; Das, S.; Aktara, M.N.; Patra, A.; Islam, M.M.; Hossain, M. Study on the antibacterial activity and interaction with human serum albumin of Tagetes erecta inspired biogenic silver nanoparticles. Process Biochem. 2020, 97, 191–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, X.; Balankura, T.; Zhou, Y.; Fichthorn, K.A. How structure-directing agents control nanocrystal shape: PVP-mediated growth of Ag nanocubes. Nano Lett. 2015, 15, 7711–7717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samanta, S.; Pyne, S.; Sarkar, P.; Sahoo, G.P.; Bar, H.; Bhui, D.K.; Misra, A. Synthesis of silver nanostructures of varying morphologies through seed mediated growth approach. J. Mol. Liq. 2010, 153, 170–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuette, W.M.; Buhro, W.E. Silver chloride as a heterogeneous nucleant for the growth of silver nanowires. ACs Nano 2013, 7, 3844–3853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruna, T.; Maldonado-Bravo, F.; Jara, P.; Caro, N. Silver nanoparticles and their antibacterial applications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 7202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S.A.; Das, S.S.; Khatoon, A.; Ansari, M.T.; Afzal, M.; Hasnain, M.S.; Nayak, A.K. Bactericidal activity of silver nanoparticles: A mechanistic review. Mater. Sci. Energy Technol. 2020, 3, 756–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menichetti, A.; Mavridi-Printezi, A.; Mordini, D.; Montalti, M. Effect of size, shape and surface functionalization on the antibacterial activity of silver nanoparticles. J. Funct. Biomater. 2023, 14, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fracassetti, D.; Cost, C.; Moulay, L.; Tomás-Barberán, F.A. Ellagic acid derivatives, ellagitannins, proanthocyanidins and other phenolics, vitamin C and antioxidant capacity of two powder products from camu-camu fruit (Myrciaria dubia). Food Chem. 2013, 139, 578–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burlec, A.F.; Pecio, L.; Kozachok, S.; Mirces, C.; Corciova, A.; Verestiuc, L.; Cioanca, O.; Olezek, W.; Hancianu, M. Phytochemical profile, antioxidant activity, and cytotoxicity assessment of Tagetes erecta L. flowers. Molecules 2021, 26, 1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moliner, C.; Barros, L.; Dias, M.I.; López, V.; Langa, E.; Ferreira, I.C.F.R.; Gómez-Rincón, C. Edible flowers of Tagetes erecta L. as functional ingredients: Phenolic composition, antioxidant and protective effects on Caenorhabditis elegans. Nutrients 2018, 10, 2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parejo, I.; Jáuregui, O.; Viladomat, F.; Bastida, J.; Codina, C. Characterization of acylated flavonoid-O-glycosides and methoxylated flavonoids from Tagetes maxima by LC-ESI-MS/MS. Rapid Commun. Mass. Spectrom. 2004, 18, 2801–2810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luu, Q.N.; Doorn, J.M.; Berry, M.T.; Jiang, C.; Lin, C.F.; May, P.S. Preparation and optical properties of silver nanowires and silver-nanowire thin films. J. Colloid. Interf. Sci. 2011, 356, 151–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; An, C.; Zhang, M.; Qin, C.; Ming, X.; Zhang, Q. Photochemical conversion of AgCl nanocubes to hybrid AgCl-Ag nanoparticles with high activity and long-term stability towads photocatalytic degradation of organic dyes. Can. J. Chem. 2012, 90, 858–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, C.; Yang, P.; Zhang, A. Glycerol and ethylene glycol co-mediated synthesis of uniform multiple crystalline silver nanowires. Mat. Chem. Phys. 2014, 143, 794–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shankar, S.; Prasad, R.G.S.V.; Selvakannan, P.R.; Jaiswal, L.; Laxman, R.S. Green synthesis of silver nanoribbons from waste X-ray films using alkaline protease. Mat. Exp. 2015, 5, 165–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyllested, J.A.; Espina Palanco, M.; Hagen, N.; Mogensen, K.B.; Kneipp, K. Green preparation and spectroscopic characterization of plasmonic silver nanoparticles using fruits as reducing agents. Beilstein J. Nanotehcnol 2015, 6, 293–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinten, M. The color of finely dispersed nanoparticles. Appl. Phys. B 2001, 73, 317–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shameli, K.; Bin Ahmad, M.; Yunus, W.Z.W.; Ibrahim, N.A.; Darroudi, M. Synthesis and characterization of silver/talc nanocomposites using the wet chemical reduction method. Int. J. Nanomed. 2010, 5, 743–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesham, M.; Ayodhya, D.; Madhusudhan, A.; Veerabhadram, G. Synthesis of stable silver nanoparticles using gum acacia as reducing and stabilizing agent and study of its microbial properties: A novel green approach. Int. J. Green. Nanotechnol. 2015, 4, 199–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashyap, M.; Samadhiya, K.; Ghosh, A.; Anand, V.; Shirage, P.M.; Bala, K. Screening of microalgae for biosynthesis and optimization of Ag/AgCl nano hybrids having antibacterial effect. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 25583–25591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alharbi, N.S.; Alsubhi, N.S.; Felimban, A.I. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using medicina plants: Characterization and application. J. Radiat. Res. Appl. Sci. 2022, 15, 109–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.J.; Sung, W.S.; Suh, B.K.; Moon, S.K.; Choi, J.S.; Kim, J.G.; Lee, D.G. Antifungal activity and mode of action of silver nanoparticles on Candida Albicans. Biometals 2009, 22, 235–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, K.; Setyawati, M.I.; Leong, D.T.; Xie, J. Antimicrobial silver nanomaterials. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2018, 357, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.Z.; Nikaido, H.; Williams, K.E. Silver resistant mutants of Eschericha Coli display active efflux of Ag+ and are deficient in Porins. J. Bacteriol. 1997, 179, 6127–6132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levard, C.; Mitra, S.; Yang, T.; Jew, A.D.; Badireddy, A.R.; Lowry, G.V.; Brown, G.E. Effect of chloride on the disolution rate of silver nanoparticles and toxicity to E. coli. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013, 47, 5738–5745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Maynes, M.; Silver, S. Effects of halides on plasmid-mediated silver resistance in Escherichia coli. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1998, 64, 5042–5045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silver, S.; Perry, R.D.; Tynecka, Z.; Kinscherf, T.G. Mechanisms of bacterial resistances to the toxic heavy metals antimony, arsenic, cadmium, mercury and silver. In Proceedings of Third Tokyo Symposium on Drug Resistance in Bacteria, Tokyo, Japan, August 1982; Japan Scientific Societes Press: Tokyo, Japan, 1982; pp. 347–361. [Google Scholar]

- Domínguez, X. Métodos de Investigación Fitoquímica; Limusa: Mexico City, Mexico, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Ballesteros, O.J.V.; Perea, E.M.; Méndez, J.J.; Arango, W.M.; Noreña, D.A. Quantification, chemical and biological characterization of the saponosides material from Sida cordifolia (escobilla). Rev. Cubana Plant Med. 2013, 12, 298–314. [Google Scholar]

- Scales, F.M. The determination of reducing sugars. J. Bio Chem. 1915, 23, 81–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, S.; Hypolito, R.; Ulbrich, H.H.G.J.; Silva, M. Iron (II) oxide determination in rocks and mineral. Chem. Geo 2002, 182, 85–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera-Gómez, A. Uncertainties in photoemision peak fitting accounting for the covariance with background parameters. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. A 2020, 38, 033211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vickerman, J.C.; Gilmore, I.S. Surface Analysis. The Principal Techniques, 2nd ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Beamson, G.; Briggs, D. High Resolution XPS of Organic Polymers. The Scienta ESCA300 Databse; John Wiley & Sons: Chirchester, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Kahm, M.; Hasenbrink, G.; Lichtenberg-Fraté, H.; Ludwig, J.; Kschischo, M. grofit: Fitting biological growth curves with R. J. Stat. Softw. 2010, 33, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, D.J.; Laure, N.B.; Guru, S.K.; Khan, I.A.; Ajit, S.K.; Vishwakarma, R.A.; Pierre, T. Antiproliferative and antimicrobial activities of alkylbenzoquinone derivatives from Ardisia kivuensis. Pharm. Biol. 2014, 52, 392–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Phytochemical Compounds | Test | Result |

|---|---|---|

| Saponins | Hot water | Honeycomb stable for about 60 min. Positive test |

| Rosenthaler assay | Negative | |

| Triterpenes | Chloroform/H2SO4 | Negative |

| Tannins | Chloride ferric salt | Negative |

| Flavonoids | Ammonia vapors | Positive for the presence of flavonoids |

| Shinoda | Positive for the presence of flavanone or dihydroflavonol | |

| NaOH Assay | Positive for the presence of flavonoids | |

| Coumarins | NaOH/heat/UV light | Negative |

| No. | RT (min) | m/z Observed | Ion Compared | m/z Theoretical | Error (ppm) | Neutral Formula | Compound | Major Fragments (%) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.820 | 191.117 | [M−H]− | 191.055563 | −0.061437 u; −321.6 ppm | C7H12O6 | Quinic acid | 191 (base); 173, 127, 111 | Parejo et al., 2004 [20] |

| 2 | 1.097 | 191.080 | [M−H]− | 191.055563 | −0.024437 u; −127.9 ppm | C7H12O6 | Quinic acid (co-eluting isomer) | 191 (base); 173, 127, 111 | Parejo et al., 2004 [20] |

| 3 | 1.320 | 169.079 | [M−H]− | 169.013698 | −0.065302 u; −386.4 ppm | C7H6O5 | Gallic acid | 169 → 125 (CO2 loss) | Parejo et al., 2004 [20] |

| 4 | 2.070 | 301.000 | [M−H]− | 300.998442 | −0.001558 u; −5.2 ppm | C14H6O8 | Ellagic acid | 301 (base); 257, 229 | Fracassetti et al., 2013 [17] |

| 5 | 3.140 | 645.135 | [M+HCOO]− | 645.1456 | +0.010600 u; +16.4 ppm | C29H28O14 | Kaempferol-3-O-(6″-galloyl)-hexoside | 645 (adduct), ~599 ([M−H]−), 453 (−Hex), 437 (−acyl), 285 (aglycone), 169/125 (galloyl) | Parejo et al., 2004 [20] |

| 6 | 3.790 | 687.139 | [M+HCOO]− | 687.119739 | −0.019261 u; −28.0 ppm | C30H26O16 | Quercetagetin-O-caffeoyl-hexoside | 687 (100); 641; 317; 179/161 | Parejo et al., 2004 [20] |

| 7 | 4.360 | 555.158 | [M+HCOO]− | 555.1449 | +0.013100 u; +23.6 ppm | C23H22O14 | Flavonol-O-glycoside | 509 ([M−H]−), 345 (aglycone, −Hex), 327/315 (H2O/CO), 179/161 (caffeoyl, trace) | Parejo et al., 2004 [20] |

| 8 | 4.680 | 525.160 | [M+HCOO]− | 525.088045 | −0.071955 u; −137.0 ppm | C21H20O13 | Myricetin-3-O-hexoside | 525 (adduct); 479 ([M−H]−); aglycone 317 | Moliner et al., 2018 [19]; Burlec et al., 2021 [18] |

| 9 | 5.090 | 539.168 | [M+HCOO]− | 539.103695 | −0.064305 u; −119.3 ppm | C22H22O13 | Patuletin-O-hexoside | 539 (adduct); 493 ([M−H]−); aglycone 331 | Parejo et al., 2004 [20]; Burlec et al., 2021 [18] |

| 10 | 5.450 | 579.201 | [M+HCOO]− | 579.098610 | −0.102390 u; −176.8 ppm | C24H22O14 | Kaempferol-3-O-(6″-malonyl)-hexoside (putative) | 579 (adduct); 245/305 | Parejo et al., 2004 [20] |

| 11 | 5.570 | 317.084 | [M−H]− | 317.029742 | −0.054258 u; −171.1 ppm | C15H10O8 | Quercetagetin (aglycone) | 317; [2M−H]− ≈ 635 | Parejo et al., 2004 [20] |

| 12 | 5.680 | 864.331 | [M+HCOO]− | 863.209342 | −1.121658 u; −1299.4 ppm | C34H42O23 | Laricitrin-trihexoside (putative) | 864 adduct series; 317/331 present | Moliner et al., 2018 [19]; Burlec et al., 2021 [18] |

| 13 | 6.070 | 491.244 | [M−H]− | 491.082566 | −0.161434 u; −328.7 ppm | C22H20O13 | Isorhamnetin-3-O-glucuronide (co-eluting) | 491; [2M−H]− ≈ 983 (weak) | Burlec et al., 2021 [18] |

| 14 | 6.070 | 545.151 | [M−H]− | 545.150645 | −0.000355 u; −0.7 ppm | C23H30O15 | Flavonol-O-acyl-glucuronide (putative) | Formate adduct ~591 | Parejo et al., 2004 [20] |

| 15 | 6.260 | 491.245 | [M−H]− | 491.082566 | −0.162434 u; −330.8 ppm | C22H20O13 | Isorhamnetin-3-O-glucuronide (isomer) | 491; [2M−H]− ≈ 983 | Burlec et al., 2021 [18] |

| 16 | 6.400 | 625.333 | [M+HCOO]− | 625.104089 | −0.228911 u; −366.2 ppm | C25H24O16 | Laricitrin-3-O-(6″-malonyl)-hexoside (putative) | 625 (adduct) ↔ 579 ([M−H]−); 491 co-eluting | Parejo et al., 2004 [20]; Burlec et al., 2021 [18] |

| 17 | 6.400 | 491.246 | [M−H]− | 491.082566 | −0.163434 u; −332.8 ppm | C22H20O13 | Isorhamnetin-3-O-glucuronide (co-eluting) | 491; [2M−H]− ≈ 983 (trace) | Burlec et al., 2021 [18] |

| 18 | 6.500 | 491.280 | [M−H]− | 491.082566 | −0.197434 u; −402.0 ppm | C22H20O13 | Isorhamnetin-3-O-glucuronide (isomer) | 491; 534/535; 580/625 | Burlec et al., 2021 [18] |

| 19 | 6.650 | 787.243 | [M+HCOO]− | 787.156912 | −0.086088 u; −109.4 ppm | C31H34O21 | Laricitrin-dihexoside-malonyl | 787 adduct; 575→463→331 | Parejo et al., 2004 [20]; Moliner et al., 2018 [19] |

| 20 | 6.730 | 485.405 | [M−H]− | 493.1135 | +7.7085 u; +15,630 ppm | C22H22O13 | Laricitrin-3-O-hexo-side | 331/330/329 (aglycone ladder), 314 (demethylation), 483/489 | Moliner et al., 2018 [19]; Burlec et al., 2021 [18] |

| Core Level | Talc | Gum % Atomic Presence | Salt |

|---|---|---|---|

| Carbon 1s | 19.6 | 72.8 | 60.2 |

| Oxygen 1s | 35.8 | 22.6 | 17.3 |

| Silver 3d | 1.0 | 1.7 | 12.9 |

| Silicon 2p | 23.4 | - | - |

| Magnesium 2p | 20.2 | - | - |

| Others (N1s, Cl2p) | - | 2.9 | 9.6 |

| Sample Number | AgNO3 [20 mM] | Stirring | * Additional Reaction Agent [0.01 M] | Extract (mL) | TEE | Stirring |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3 mL | x | 3 mL | 3 mL | A | |

| 2 | 1.5 mL | 3 mL | 4.5 mL | A | ||

| 3 | 4.5 mL | 3 mL | 1.5 mL | A | ||

| 4 | 3 mL | 30 min | 3 mL | 3 mL | A | |

| 5 | 1.5 mL | 30 min | 3 mL | 4.5 mL | A | |

| 6 | 4.5 mL | 30 min | 3 mL | 1.5 mL | A | |

| 7 | 3 mL | 30 min | 3 mL | 3 mL | A | 30 min |

| 8 | 1.5 mL | 30 min | 3 mL | 4.5 mL | A | 30 min |

| 9 | 4.5 mL | 30 min | 3 mL | 1.5 mL | A | 30 min |

| 10 | 3 mL | 3 mL | 3 mL | B | ||

| 11 | 1.5 mL | 3 mL | 4.5 mL | B | ||

| 12 | 4.5 mL | 3 mL | 1.5 mL | B | ||

| 13 | 3 mL | 30 min | 3 mL | 3 mL | B | |

| 14 | 1.5 mL | 30 min | 3 mL | 4.5 mL | B | |

| 15 | 4.5 mL | 30 min | 3 mL | 1.5 mL | B | |

| 16 | 3 mL | 30 min | 3 mL | 3 mL | B | 30 min |

| 17 | 1.5 mL | 30 min | 3 mL | 4.5 mL | B | 30 min |

| 18 | 4.5 mL | 30 min | 3 mL | 1.5 mL | B | 30 min |

| Test | E. faecalis | E. coli |

|---|---|---|

| Blank | 10 mL LB media | 10 mL LB media |

| Positive control | 10 mL LB media + 2 μL of the overnight | 10 mL LB media + 2 μL of the overnight |

| Blank I | 10 mL LB media + 100 μL AE-Tef | 10 mL LB media + 100 μL AE-Tef |

| TEE I | 10 mL LB media + 2 μL of the overnight + 100 μL AE-Tef | 10 mL LB media + 2 μL of the overnight + 100 μL AE-Tef |

| Blank II | 10 mL LB media + 450 μL AE-Tef | 10 mL LB media + 450 μL AE-Tef |

| TEE II | 10 mL LB media + 2 μL of the overnight + 450 μL AE-Tef | 10 mL LB media + 2 μL of the overnight + 450 μL AE-Tef |

| Blank III | 10 mL LB media + 100 μL nanomaterial | 10 mL LB media + 100 μL nanomaterial |

| Nanomaterial test | 10 mL LB media + 2 μL of the overnight + 100 μL nanomaterial | 10 mL LB media + 2 μL of the overnight + 100 μL nanomaterial |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

López-Naranjo, E.J.; Cid-Hernández, M.; Vázquez-Lepe, M.O.; Luviano, M.; Sánchez-Peña, M.J.; González-Ortiz, L.J.; Dueñas-Bolaños, C.A.; Jiménez-Aguilar, J.A.; Briones-Márquez, L.F.; Herrera-González, A. Biosynthesis of Silver Nanoparticles Using Tagetes erecta: Extract Characterization, Morphological Modification Using Structure Directing or Heterogeneous Nucleating Agents, and Antibacterial Evaluation. Molecules 2025, 30, 4596. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234596

López-Naranjo EJ, Cid-Hernández M, Vázquez-Lepe MO, Luviano M, Sánchez-Peña MJ, González-Ortiz LJ, Dueñas-Bolaños CA, Jiménez-Aguilar JA, Briones-Márquez LF, Herrera-González A. Biosynthesis of Silver Nanoparticles Using Tagetes erecta: Extract Characterization, Morphological Modification Using Structure Directing or Heterogeneous Nucleating Agents, and Antibacterial Evaluation. Molecules. 2025; 30(23):4596. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234596

Chicago/Turabian StyleLópez-Naranjo, Edgar J., Margarita Cid-Hernández, Milton O. Vázquez-Lepe, Marisol Luviano, María Judith Sánchez-Peña, Luis J. González-Ortiz, César A. Dueñas-Bolaños, Jaime A. Jiménez-Aguilar, Luisa Fernanda Briones-Márquez, and Azucena Herrera-González. 2025. "Biosynthesis of Silver Nanoparticles Using Tagetes erecta: Extract Characterization, Morphological Modification Using Structure Directing or Heterogeneous Nucleating Agents, and Antibacterial Evaluation" Molecules 30, no. 23: 4596. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234596

APA StyleLópez-Naranjo, E. J., Cid-Hernández, M., Vázquez-Lepe, M. O., Luviano, M., Sánchez-Peña, M. J., González-Ortiz, L. J., Dueñas-Bolaños, C. A., Jiménez-Aguilar, J. A., Briones-Márquez, L. F., & Herrera-González, A. (2025). Biosynthesis of Silver Nanoparticles Using Tagetes erecta: Extract Characterization, Morphological Modification Using Structure Directing or Heterogeneous Nucleating Agents, and Antibacterial Evaluation. Molecules, 30(23), 4596. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234596