Alkaline Reaction Pathways of Phenolic Compounds with β-Lactoglobulin Peptides: Polymerization and Covalent Adduct Formation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

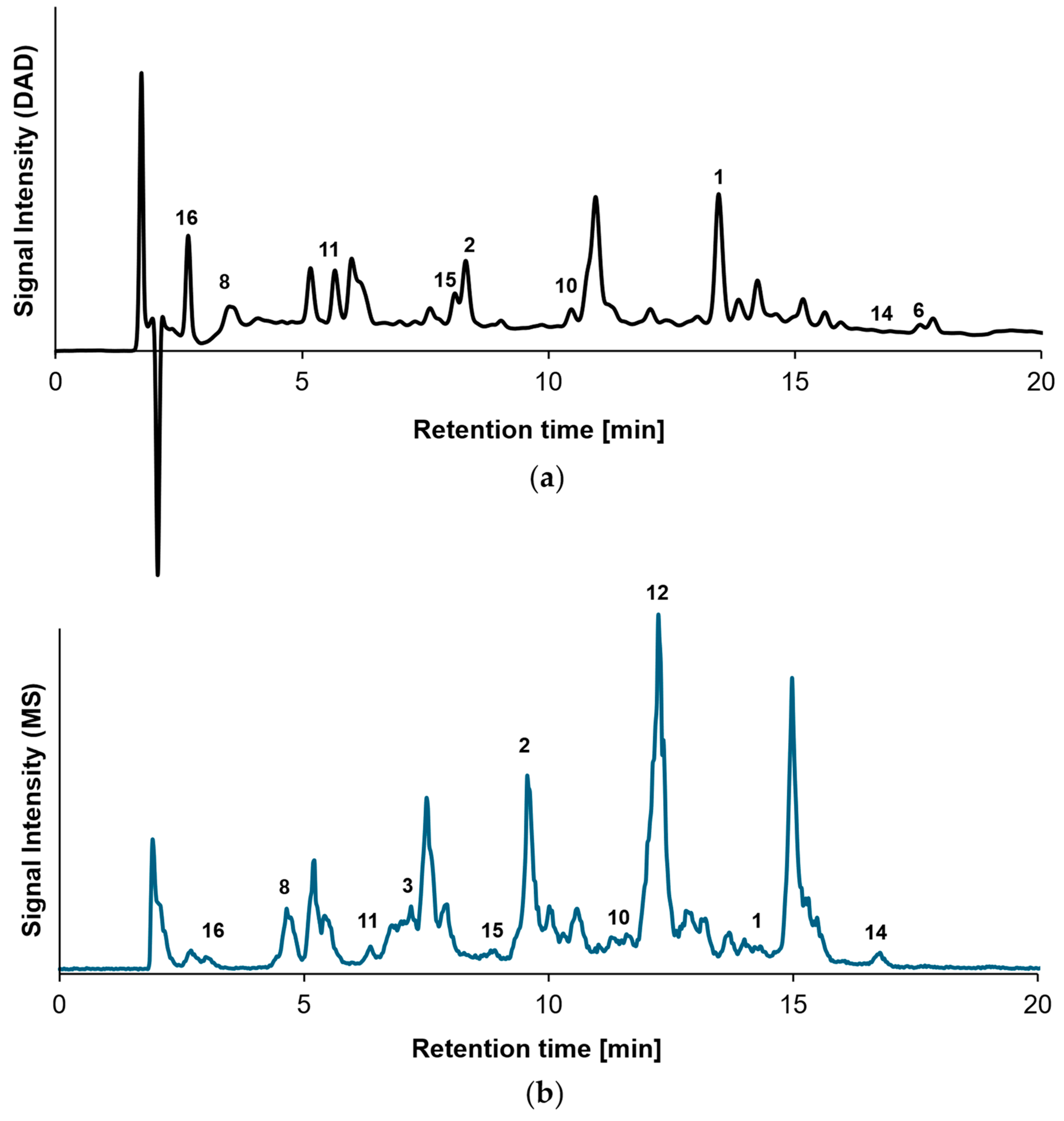

2.1. Characterization of β-Lg Peptides

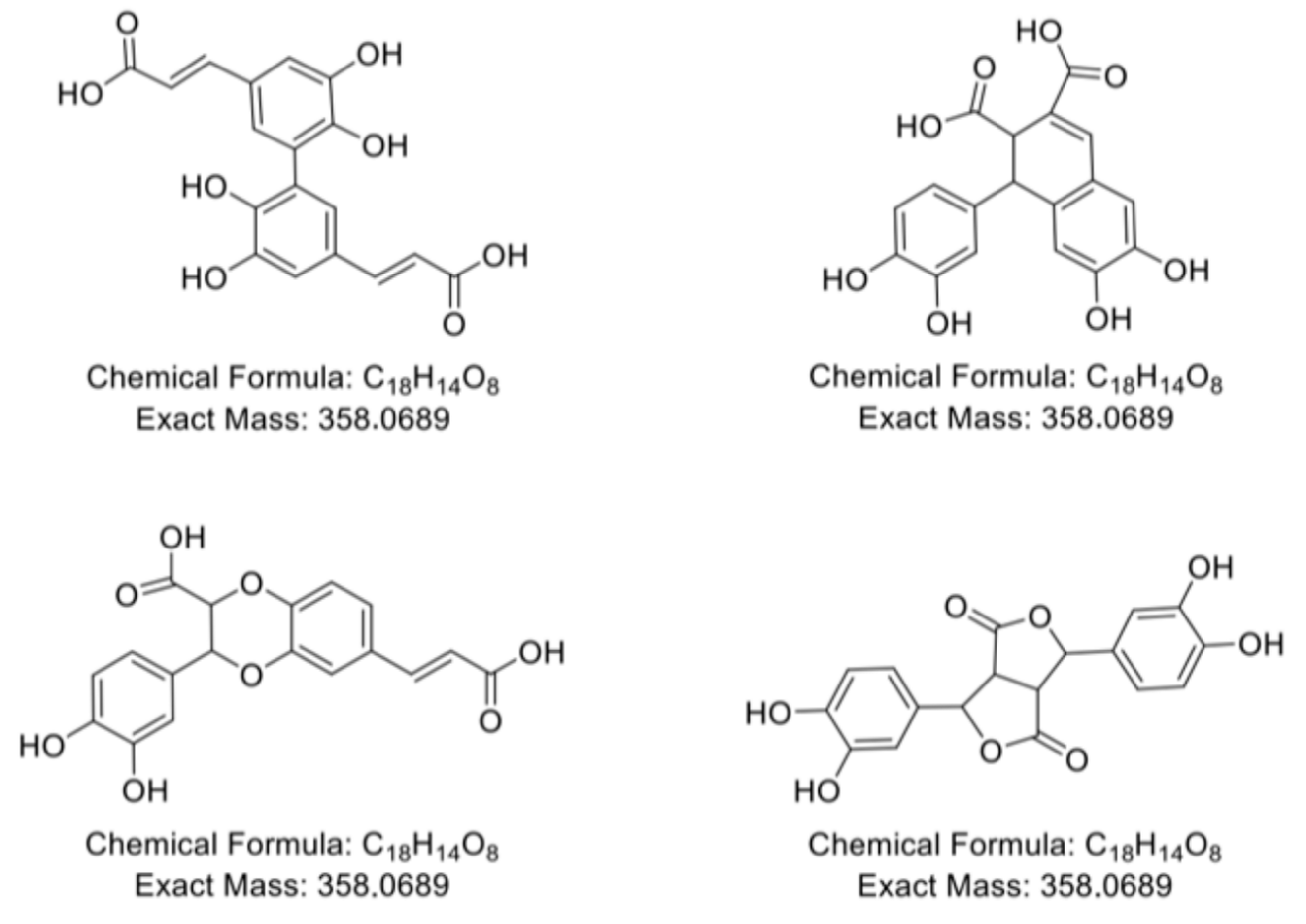

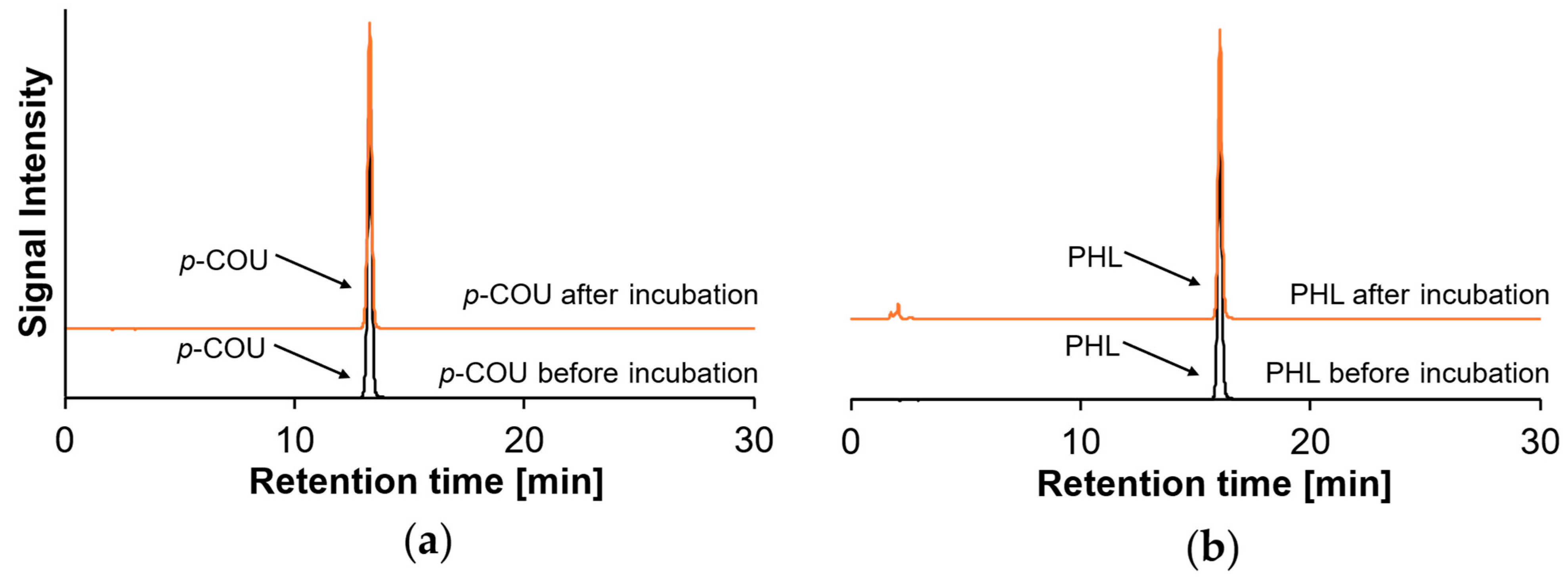

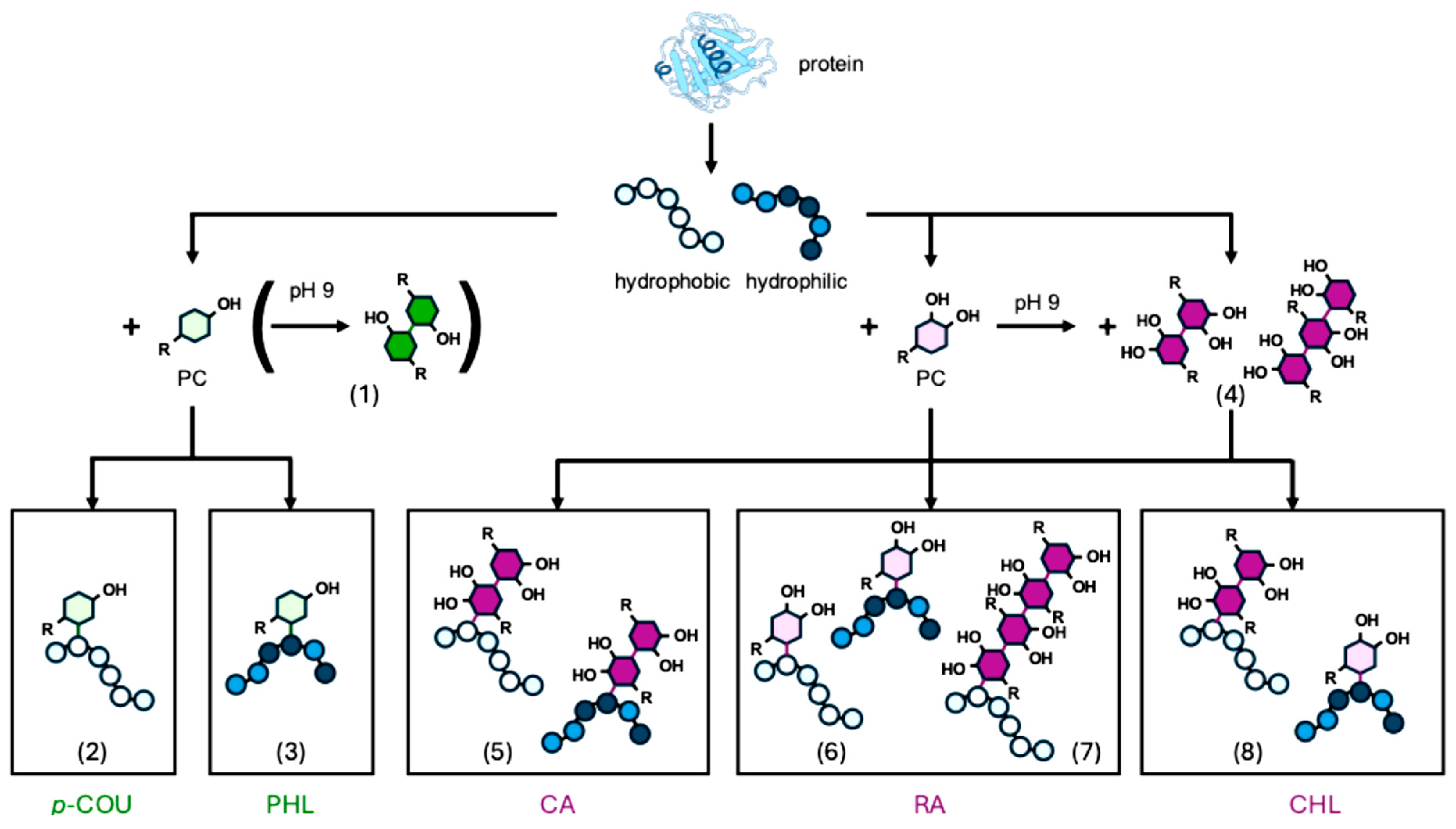

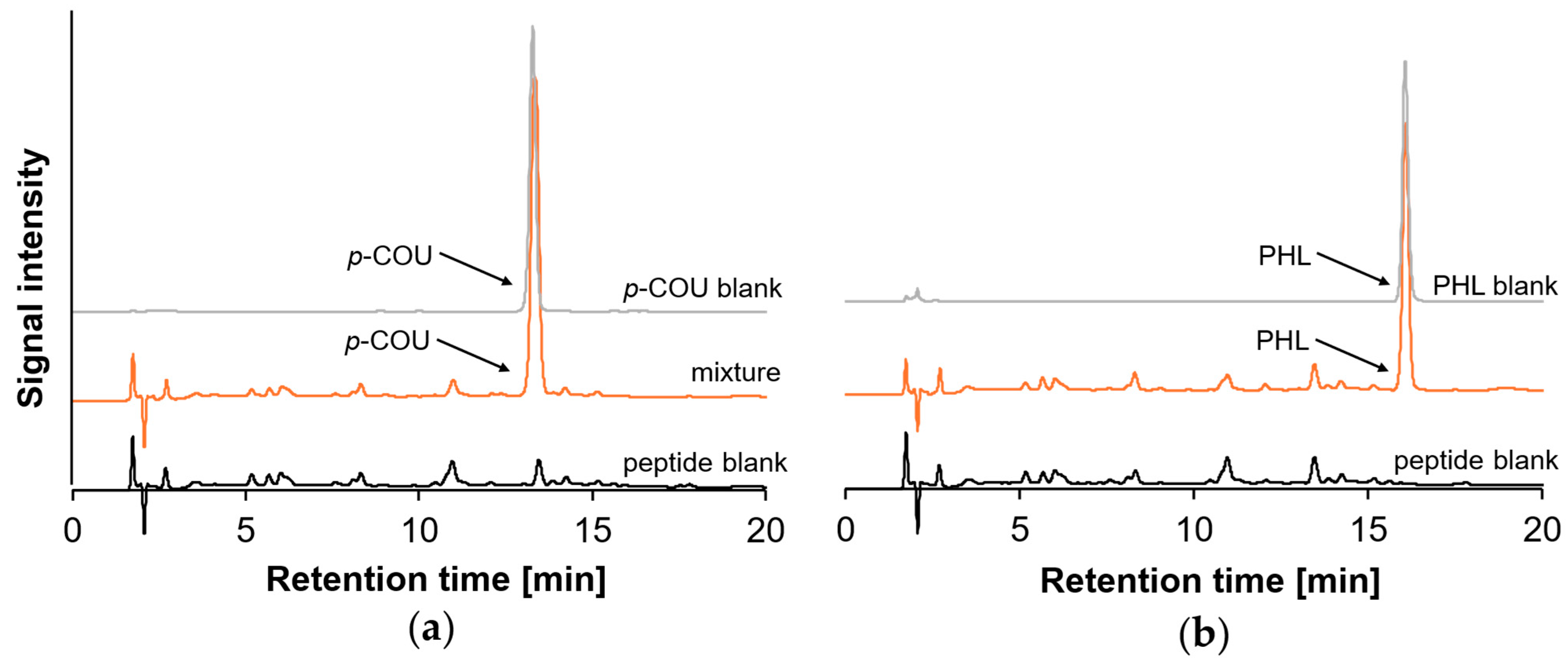

2.2. Polymerization Behavior of Monohydroxy PCs

2.3. Reaction Behavior of Monohydroxy PCs with β-Lg Peptides

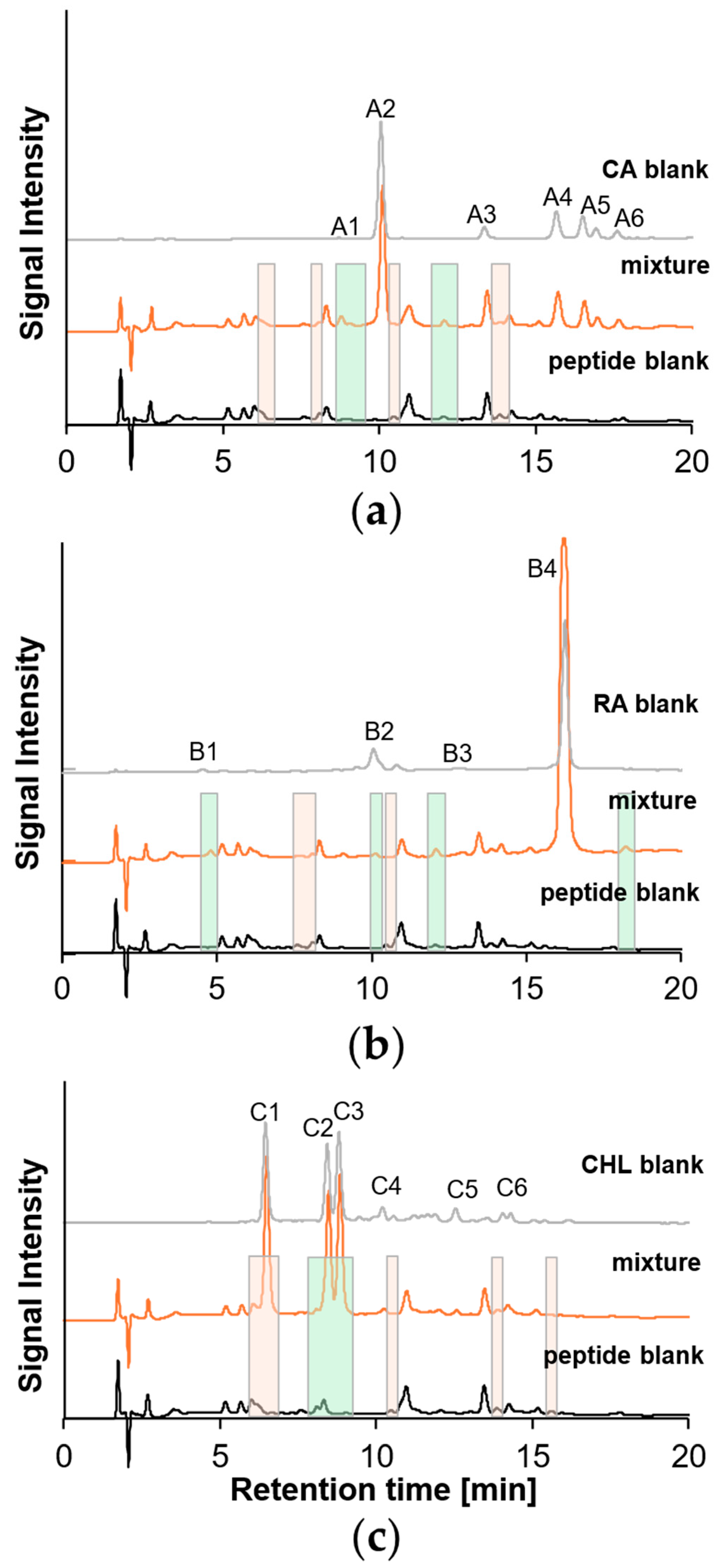

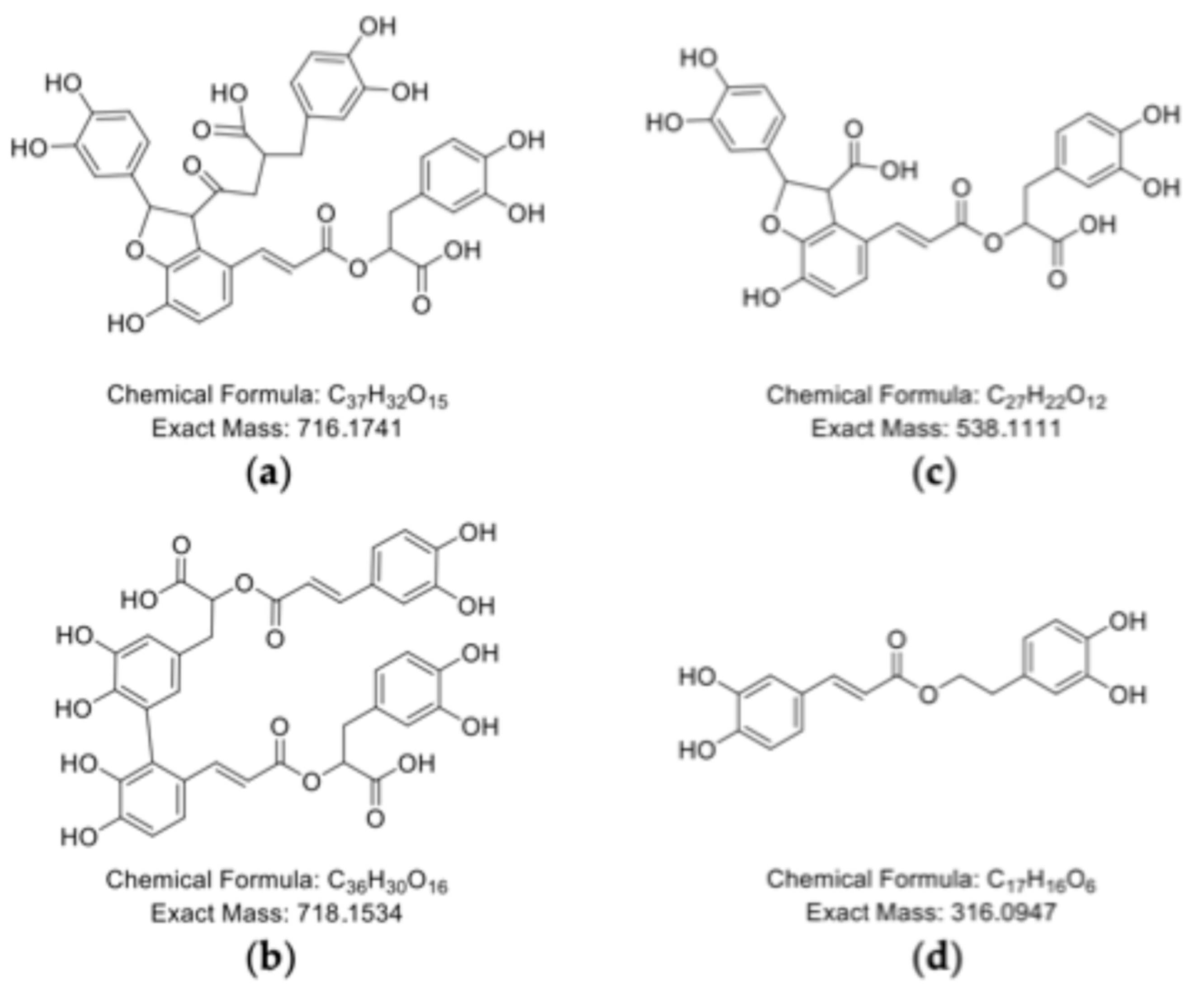

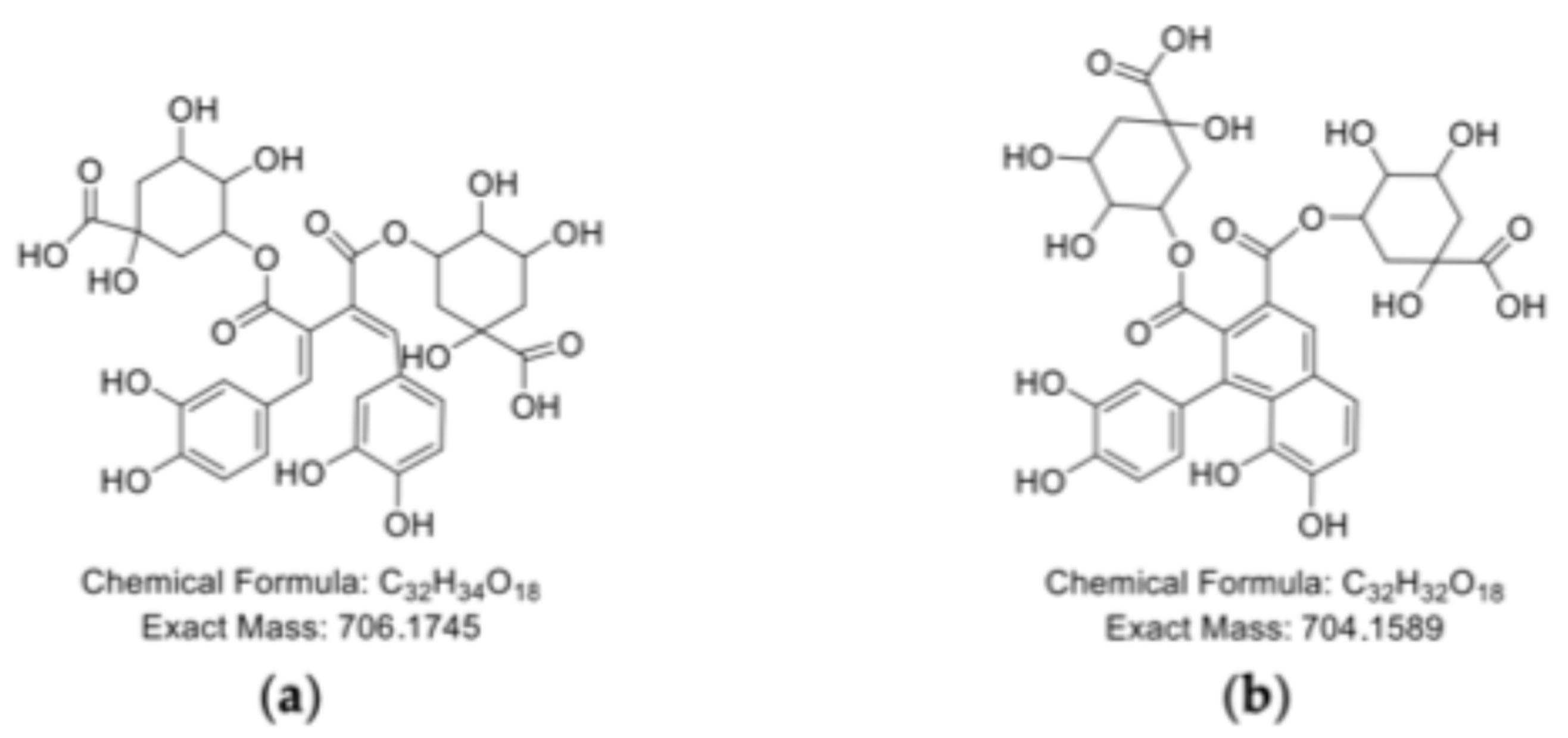

2.4. Polymerization Behavior of o-Dihydroxy PCs

2.5. Reaction Behavior of o-Dihydroxy PCs with β-Lg Peptides

3. Materials and Methods

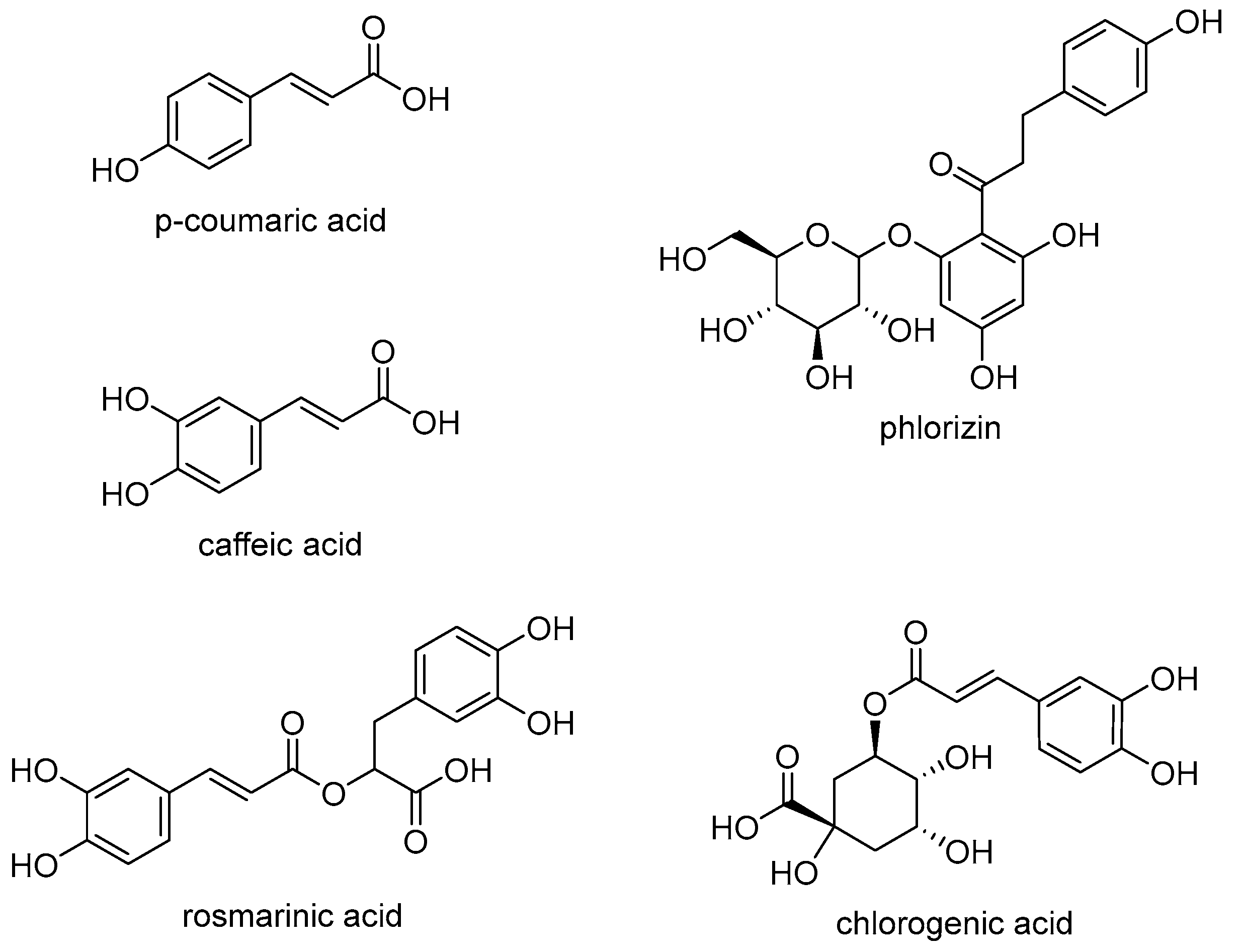

3.1. Phenolic Compounds—Structural Characteristics

3.2. β-Lactoglobulin Solutions and Tryptic Digestion

3.3. Formation of Peptide–PC Adducts

3.4. Characterization of Covalent Adducts

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rohn, S. Possibilities and Limitations in the Analysis of Covalent Interactions between Phenolic Compounds and Proteins. Food Res. Int. 2014, 65, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozdal, T.; Capanoglu, E.; Altay, F. A Review on Protein-Phenolic Interactions and Associated Changes. Food Res. Int. 2013, 51, 954–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kieserling, H.; de Bruijn, W.J.C.; Keppler, J.; Yang, J.; Sagu, S.T.; Güterbock, D.; Rawel, H.; Schwarz, K.; Vincken, J.P.; Schieber, A.; et al. Protein–Phenolic Interactions and Reactions: Discrepancies, Challenges, and Opportunities. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2024, 23, e70015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanakis, C.D.; Hasni, I.; Bourassa, P.; Tarantilis, P.A.; Polissiou, M.G.; Tajmir-Riahi, H.A. Milk β-Lactoglobulin Complexes with Tea Polyphenols. Food Chem. 2011, 127, 1046–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, L.B.; Wang, B.; Zisu, B.; Adhikari, B. Covalent Modification of Flaxseed Protein Isolate by Phenolic Compounds and the Structure and Functional Properties of the Adducts. Food Chem. 2019, 293, 463–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagis, L.M.; Yang, J. Protein-Stabilized Interfaces in Multiphase Food: Comparing Structure-Function Relations of Plant-Based and Animal-Based Proteins. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2022, 43, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahidi, F.; Dissanayaka, C.S. Phenolic-Protein Interactions: Insight from in-Silico Analyses—A Review. Food Prod. Process. Nutr. 2023, 5, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; Zeng, Z.; McClements, D.J.; Gong, X.; Yu, P.; Xia, J.; Gong, D. A Review of the Structure, Function, and Application of Plant-Based Protein–Phenolic Conjugates and Complexes. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2023, 22, 1312–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bittner, S. When Quinones Meet Amino Acids: Chemical, Physical and Biological Consequences. Amino Acids 2006, 30, 205–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, W.; Zhou, X.; McCallum, N.C.; Hu, Z.; Ni, Q.Z.; Kapoor, U.; Heil, C.M.; Cay, K.S.; Zand, T.; Mantanona, A.J.; et al. Unraveling the Structure and Function of Melanin through Synthesis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 2622–2637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pirker, K.F.; Baratto, M.C.; Basosi, R.; Goodman, B.A. Influence of PH on the Speciation of Copper(II) in Reactions with the Green Tea Polyphenols, Epigallocatechin Gallate and Gallic Acid. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2012, 112, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prigent, S.V.E.; Voragen, A.G.J.; van Koningsveld, G.A.; Baron, A.; Renard, C.M.G.C.; Gruppen, H. Interactions between Globular Proteins and Procyanidins of Different Degrees of Polymerization. J. Dairy Sci. 2009, 92, 5843–5853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strauss, G.; Gibson, S.M. Plant Phenolics as Cross-Linkers of Gelatin Gels and Gelatin-Based Coacervates for Use as Food Ingredients. Food Hydrocoll. 2004, 18, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horigome, T.; Kumar, R. Fractionation, Characterization, and Protein-Precipitating Capacity of the Condensed Tannins from Robinia Pseudo Acacia L. Leaves. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1986, 34, 487–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawel, H.M.; Rohn, S. Nature of Hydroxycinnamate-Protein Interactions. Phytochem. Rev. 2010, 9, 93–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singleton, V.L.; Cilliers, J.J.L. Characterization of the Products of Nonenzymic Autoxidative Phenolic Reactions in a Caffeic Acid Model System. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1991, 39, 1298–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Cheng, Z.; Wang, Y.; Fu, L. Dietary Protein-Phenolic Interactions: Characterization, Biochemical-Physiological Consequences, and Potential Food Applications. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020, 61, 3589–3615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbiroli, A.; Iametti, S.; Bonomi, F. Beta-Lactoglobulin as a Model Food Protein: How to Promote, Prevent and Exploit Its Unfolding Processes. Molecules 2022, 27, 1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bock, A.; Kieserling, H.; Steinhäuser, U.; Rohn, S. Impact of Phenolic Acid Derivatives on the Oxidative Stability of β-Lactoglobulin-Stabilized Emulsions. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rye, T.K.; Lee, C.Y.; Zellner, A.; Moen, S.H.; Dowlatshah, S.; Grønhaug Halvorsen, T.; Pedersen-Bjergaard, S.; Hansen, F.A. Electromembrane Extraction of Peptides Based on Charge, Hydrophobicity, and Size—A Large-Scale Fundamental Study of the Extraction Window. J. Sep. Sci. 2024, 47, e2400292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, A.K.; Manasa, B.P.; Murty, U.S. Assessing the Relationship among Physicochemical Properties of Proteins with Respect to Hydrophobicity: A Case Study on AGC Kinase Superfamily. Indian J. Biochem. Biophys. 2010, 47, 370–377. [Google Scholar]

- Turgeon, S.L.; Gauthier, S.F.; Mollé, D.; Léonil, J. Interfacial Properties of Tryptic Peptides of β-Lactoglobulin. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1992, 40, 669–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Löwik, D.W.P.M.; van Hest, J.C.M. Peptide Based Amphiphiles. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2004, 33, 234–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Ledesma, B.; Recio, I.; Amigo, L. β-Lactoglobulin as Source of Bioactive Peptides. Amino Acids 2008, 35, 257–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villanueva, A.; Vioque, J.; Sânchez-Vioque, R.; Clémente, A.; Pedroche, J.; Bautista, J.; Millan, F. Peptide Characteristics of Sunflower Protein Hydrolysates. JAOCS J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 1999, 76, 1455–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hapiot, P.; Neudeck, A.; Pinson, J.; Fulcrand, H.; Neta, P.; Rolando, C. Oxidation of Caffeic Acid and Related Hydroxycinnamic Acids. J. Electroanal. Chem. 1996, 405, 169–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antolovich, M.; Bedgood, D.R.; Bishop, A.G.; Jardine, D.; Prenzler, P.D.; Robards, K. LC-MS Investigation of Oxidation Products of Phenolic Antioxidants. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2004, 52, 962–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thi, T.H.; Matsusaki, M.; Shi, D.; Kaneko, T.; Akashi, M. Synthesis and Properties of Coumaric Acid Derivative Homo-Polymers. J. Biomater. Sci. Polym. Ed. 2008, 19, 75–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, C.; Xue, J.; Yang, X.; Ke, Y.; Ou, R.; Wang, Y.; Madbouly, S.A.; Wang, Q. From Plant Phenols to Novel Bio-Based Polymers. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2022, 125, 101473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikumi, Y.; Kida, T.; Sakuma, S.; Yamashita, S.; Akashi, M. Polymer-Phloridzin Conjugates as an Anti-Diabetic Drug That Inhibits Glucose Absorption through the Na+/Glucose Cotransporter (SGLT1) in the Small Intestine. J. Control. Release 2008, 125, 42–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, H.; Liu, C.; Geng, S. Laccase Catalyzed Oxidative Polymerization of Phloridzin: Polymer Characterization, Antioxidant Capacity and α-Glucosidase Inhibitory Activity. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2021, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawel, H.M.; Kroll, J.; Rohn, S. Reactions of Phenolic Substances with Lysozyme-Physicochemical Characterisation and Proteolytic Digestion of the Derivatives. Food Chem. 2001, 72, 59–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljawish, A.; Chevalot, I.; Paris, C.; Muniglia, L. Enzymatic Oxidation of Ferulic Acid as a Way of Preparing New Derivatives. BioTech 2022, 11, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stafford, H.A.; Brown, M.A. Oxidative Dimerization of Ferulic Acid by Extracts from Sorghum. Phytochemistry 1976, 15, 465–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziyatdinova, G.; Kozlova, E.; Budnikov, H. Selective Electrochemical Sensor Based on the Electropolymerized P-Coumaric Acid for the Direct Determination of L-Cysteine. Electrochim. Acta 2018, 270, 369–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asano, K.; Shinagawa, K.; Hashimoto, N.; Brewery, K. Characterization of Haze-Forming Proteins of Beer and Their Roles in Chill Haze Formation. J. Am. Soc. Brew. Chem. 1982, 40, 147–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, M.; Du, D.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, S.; Li, Z.; Dongye, Z.; Wang, L.; Qian, Y.; Chen, C.; Cheng, X.; et al. Non-Covalent Complexes Between β-Lactoglobulin and Baicalein: Characteristics and Binding Properties. Food Biophys. 2024, 19, 58–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Wu, J.; Peng, X.; Hu, X.; Gong, D.; Zhang, G. Protein Glycosylation Inhibitory Effects and Mechanisms of Phloretin and Phlorizin. Food Biosci. 2024, 61, 104971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, H.; Liu, X.; Ulrih, N.P.; Sengupta, P.K.; Xiao, J. Plasma Protein Binding of Dietary Polyphenols to Human Serum Albumin: A High Performance Affinity Chromatography Approach. Food Chem. 2019, 270, 257–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bock, A.; Rußbült, E.; Barthel, L.; Drusch, S.; Rohn, S.; Steinh, U.; Kieserling, H. Co-Adsorption and Displacement Behavior of Phenolic Acid Derivatives at a β -Lactoglobulin-Stabilized Oil—Water Interface and the Interactions of Both Solutes. Food Hydr. 2024, 149, 109578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arakawa, R.; Yamaguchi, M.; Hotta, H.; Osakai, T.; Kimoto, T. Product Analysis of Caffeic Acid Oxidation by On-Line Electrochemistry/ Electrospray Ionization Mass Spectrometry. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2004, 15, 1228–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ly, T.N.; Shimoyamada, M.; Yamauchi, R. Isolation and Characterization of Rosmarinic Acid Oligomers in Celastrus Hindsii Benth Leaves and Their Antioxidative Activity. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006, 54, 3786–3793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Mousallamy, A.M.D.; Hawas, U.W.; Hussein, S.A.M. Teucrol, a Decarboxyrosmarinic Acid and Its 4′-O-Triglycoside, Teucroside from Teucrium Pilosum. Phytochemistry 2000, 55, 927–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pezeshki, S.; Petersen, M. Rosmarinic Acid and Related Metabolites. In Biotechnology of Natural Products; Schwab, W., Lange, B.M., Wüst, M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Germany, 2018; pp. 25–60. ISBN 978-3-319-67903-7. [Google Scholar]

- Liudvinaviciute, D.; Rutkaite, R.; Bendoraitiene, J.; Klimaviciute, R. Thermogravimetric Analysis of Caffeic and Rosmarinic Acid Containing Chitosan Complexes. Carbohydr. Polym. 2019, 222, 115003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Wang, J.; Sun, J.; Qiu, S.; Chu, B.; Fang, R.; Li, L.; Gong, J.; Zheng, F. Degradation Kinetics and Isomerization of 5-O-Caffeoylquinic Acid under Ultrasound: Influence of Epigallocatechin Gallate and Vitamin C. Food Chem. X 2021, 12, 100147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagu, S.T.; Ulbrich, N.; Morche, J.R.; Nichani, K.; Özpinar, H.; Schwarz, S.; Henze, A.; Rohn, S.; Rawel, H.M. Formation of Cysteine Adducts with Chlorogenic Acid in Coffee Beans. Foods 2024, 13, 1660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prigent, V.E.; Voragen, A.G.J.; Li, F.; Visser, A.J.W.G.; Van Koningsveld, G.A.; Gruppen, H. Covalent Interactions between Amino Acid Side Chains and Oxidation Products of Caffeoylquinic Acid (Chlorogenic Acid). J. Sci. Food Agri. 2008, 1754, 1748–1754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehninger, A.L.; Nelson, D.L.; Cox, M.M. Lehninger Principles of Biochemistry; Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 2005; ISBN 0716743396. [Google Scholar]

- Keppler, J.K.; Schwarz, K.; van der Goot, A.J. Covalent Modification of Food Proteins by Plant-Based Ingredients (Polyphenols and Organosulphur Compounds): A Commonplace Reaction with Novel Utilization Potential. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 101, 38–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giacomelli, C.; Ckless, K.; Galato, D.; Miranda, F.S.; Spinelli, A. Electrochemistry of Caffeic Acid Aqueous Solutions with PH 2.0 to 8.5. J. Braz. Chem. Soc. 2002, 13, 332–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Gong, X.; Tan, H.; Liu, Y.; He, L.; Ouyang, J. Study of the Noncovalent Interactions between Phenolic Acid and Lysozyme by Cold Spray Ionization Mass Spectrometry (CSI-MS), Multi-Spectroscopic and Molecular Docking Approaches. Talanta 2020, 211, 120762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarahi, M.; Gharagozlou, M.; Niakousari, M.; Hedayati, S. Protein–Chlorogenic Acid Interactions: Mechanisms, Characteristics, and Potential Food Applications. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rawel, H.M.; Rohn, S.; Kruse, H.-P.; Kroll, J. Structural Changes Induced in Bovine Serum Albumin by Covalent Attachment of Chlorogenic Acid. Food Chem. 2002, 78, 443–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keppler, J.K.; Koudelka, T.; Palani, K.; Stuhldreier, M.C.; Temps, F.; Tholey, A.; Schwarz, K. Characterization of the Covalent Binding of Allyl Isothiocyanate to β-Lactoglobulin by Fluorescence Quenching, Equilibrium Measurement, and Mass Spectrometry. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2014, 32, 1103–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Peptide No. | Amino Acid Sequence | GRAVY | IEP | MW [m/z] | RTDAD [min] | RTMS [min] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | MKCLLLALALTCGAQA | 1.538 | 7.82 | 1620.06 | 13.6 | 14.4 |

| 2 | LIVTQTMK | 0.700 | 8.75 | 933.17 | 8.6 | 9.6 |

| 3 | GLDIQK | −0.500 | 5.84 | 672.78 | n.a. | 7.1 |

| 4 | VAGTWYSLAMAASDISLLDAQSAPLR | 0.519 | 4.21 | 2708.08 | n.a. | 25.6 |

| 5 | VYVEELKPTPEGDLEILLQK | −0.315 | 4.25 | 2313.67 | n.a. | 26.0 |

| 6 | WENGECAQK | −1.656 | 4.53 | 1064.14 | 17.3 | 18.5 |

| 7 | K | n.a. | 9.74 | 146.19 | n.a. | n.a. |

| 8 | IIAEK | 0.680 | 6.00 | 572.70 | 3.3 | 4.3 |

| 9 | TK | n.a. | n.a. | 247.29 | n.a. | n.a. |

| 10 | IPAVFK | 1.300 | 8.75 | 673.85 | 10.4 | 11.6 |

| 11 | IDALNENK | −0.975 | 4.37 | 916.00 | 5.6, 5.9 | 6.6 |

| 12 | VLVLDTDYK | 0.344 | 4.21 | 1065.23 | 11.8 | 12.5 |

| 13 | K | n.a. | 9.74 | 146.19 | n.a. | n.a. |

| 14 | YLLFCMENSAEPEQSLACQCLVR | 0.226 | 4.25 | 2648.08 | 16.8 | 17.2 |

| 15 | TPEVDDEALEK | −1.264 | 3.83 | 1245.31 | 8.2 | 8.9 |

| 16 | FDK | n.a. | n.a. | 408.44 | 2.6 | 3.5 |

| 17 | ALK | n.a. | n.a. | 330.41 | n.a. | n.a. |

| 18 | ALPMHIR | 0.386 | 9.80 | 837.05 | n.a. | 20.7 |

| 19 | LSFNPTQLEEQCHI | −0.457 | 4.51 | 1658.85 | n.a. | 25.9 |

| Adduct Mass [m/z]+ (=Mpeptide + Mp-COU − 2H) | Original RT [min] | Potentially Shifted RT [min] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial Peptide Characteristics | ||||

| Peptide No. | Nonpolar | Polar | ||

| 1 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. |

| 2 | 1095.5924 | n.a. | 9.6 | 15.5 |

| 3 | n.a. | 835.4348 | 7.1 | 14.9 |

| 4 | 2869.4326 | n.a. | 25.6 | 22.6 |

| 5 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. |

| 6 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. |

| 7 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. |

| 8 | 735.4102 | n.a. | 4.3 | 19.1 |

| 9 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. |

| 10 | 836.4687 | n.a. | 11.6 | 17.5 |

| 11 | n.a. | 1078.5166 | 6.6 | 7.1 |

| 12 | 1227.6237 | n.a. | 12.5 | 11.5 |

| 13 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. |

| 14 | 2809.2527 | n.a. | 17.2 | 18.5–34.2 |

| 15 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. |

| 16 | n.a. | 571.3024 | 3.5 | 12.9 |

| 17 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. |

| 18 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. |

| 19 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. |

| Mp-COU | 164.04373 | n.a. | 13.4 | |

| Adduct Mass [m/z]+ (=Mpeptide + MPHL − 2H) | Original RT [min] | Potentially Shifted RT [min] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peptide Characteristics | ||||

| Peptide No. | Nonpolar | Polar | ||

| 1 | 2054.2239 | n.a. | 14.4 | 13.2 |

| 2 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. |

| 3 | n.a. | 1107.7913 | 7.1 | 24.8 |

| 4 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. |

| 5 | n.a. | 2747.6589 | 26.0 | 21.9 |

| 6 | n.a. | 1498.8547 | 18.5 | 16.4 |

| 7 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. |

| 8 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. |

| 9 | n.a. | 682.5577 | n.a. | 9.1–26.8 |

| 10 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. |

| 11 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. |

| 12 | 1499.9841 | n.a. | 12.5 | 16.5–21.5 |

| 13 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. |

| 14 | 3081.6091 | n.a. | 17.2 | 16.7 |

| 15 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. |

| 16 | n.a. | 843.6095 | 3.5 | 6.4 |

| 17 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. |

| 18 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. |

| 19 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. |

| MPHL | 437.1439 | 14.7 | ||

| Peak | RTMS [min] | Mexp. [m/z]+ | Mtheor. [m/z]+ | Delta [ppm] | Putative Compound |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | 10.20 | 547.0840 | n.a. | n.a. | CA trimer with modifications |

| 1088.1510 | n.a. | n.a. | CA hexamer with modification | ||

| A2 | 12.38–16.09 | 177.0199 | 177.0194 | 2.8245 | CA monomer (as quinone) |

| A3 | 14.51 | 359.0758 | 359.0761 | 0.8354 | CA dimer |

| 479.0757 | n.a. | n.a. | CA dimer or trimer with modifications | ||

| A4 | 15.23 | 359.0759 | 359.0761 | 0.5570 | CA dimer |

| 479.0757 | n.a. | n.a. | CA dimer or trimer with modifications | ||

| A5 | 15.46 | 359.0757 | 359.0761 | 0.2785 | CA dimer |

| A6 | 19.33 | 539.1184 | 539.1211 | 5.0081 | CA trimer |

| Peak | RTMS [min] | Mexp. [m/z]+ | Mtheor. [m/z]+ | Delta [ppm] | Putative Compound |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B1 | 6.38 | 717.1815 | 717.1814 | −0.1394 | RA dimer |

| B2 | 13.96–23.64 | 539.1180 | 539.1184 | 0.7420 | RA–CA adduct |

| B3 | 15.97 | 317.1011 | 317.1020 | 2.8382 | Teucrol |

| B4 | 17.18 | 361.0916 | 361.0918 | 0.5539 | RA monomer |

| 17.16 | 721.1757 | 721.1752 | −0.6933 | RA dimer | |

| 17.16–17.30 | 1079.2460 | 1079.2441 | −1.7605 | RA trimer | |

| 17.13–17.22 | 1441.3451 | 1441.3421 | −2.0814 | RA tetramer | |

| 17.16 | 1800.4113 | 1800.4182 | 3.8324 | RA pentamer |

| Peak | RTMS [min] | Mexp. [m/z]+ | Mtheor. [m/z]+ | Delta [ppm] | Putative Compound |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C1 | 6.44 | 355.1021 | 355.1024 | 0.8448 | CHL monomer |

| C2 | 8.11–8.42 | 355.1021 | 355.1024 | 0.8448 | CHL monomer |

| C3 | 10.40–10.69 | 707.1806 | 707.1818 | 1.6969 | CHL dimer |

| 10.46 | 705.1649 | 705.1661 | 1.7017 | CHL dimer, cyclic | |

| C4 | 11.63 | 707.1807 | 707.1818 | 1.5555 | CHL dimer |

| C5 | 13.04 | 533.1285 | n.a. | n.a. | CHL dimer with modifications |

| C6 | 14.59 | 456.1168 | n.a. | n.a. | CHL dimer with modifications |

| Adduct Mass [m/z]+ (=Mpeptide + MCA−2H) | Original RTMS [min] | Potentially Shifted RTMS [min] | Adduct Mass [m/z]+ (=Mpeptide + M2×CA−4H) | Original RTMS [min] | Potentially Shifted RTMS [min] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peptide | Nonpolar | Polar | Nonpolar | Polar | ||||

| 1 | 1798.2048 | n.a. | 14.4 | 8.59 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. |

| 2 | 1111.6990 | n.a. | 9.6 | 10.67 | 1289.6125 | n.a. | 9.6 | 16.73 |

| 3 | n.a. | 851.5459 | 7.1 | 11.44 | n.a. | 1029.4604 | 7.1 | 7.53 |

| 4 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | 3036.4360 | n.a. | 25.6 | 12.07 |

| 5 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. |

| 6 | n.a. | 1042.5319 | 18.5 | 12.15 | n.a. | 1420.4955 | 18.5 | 9.42 |

| 7 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. |

| 8 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | 929.4304 | n.a. | 4.3 | 10.24–19.19 |

| 9 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. |

| 10 | 852.6366 | n.a. | 11.6 | 16.67 | 1030.4845 | n.a. | 11.6 | 13.74 |

| 11 | n.a. | 1094.6332 | 6.6 | 7.02 | n.a. | 1272.5353 | 6.6 | 7.50–21.34 |

| 12 | 1243.7330 | n.a. | 12.5 | 7.02 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. |

| 13 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. |

| 14 | 2825.3457 | n.a. | 17.2 | 26.01 | 3003.2693 | n.a. | 17.2 | 14.34 |

| 15 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | 1601.6439 | 8.9 | 11.96 |

| 16 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | 765.2756 | 3.5 | 5.65–17.45 |

| 17 | 509.3890 | n.a. | n.a | 7.11 | 687.2969 | n.a. | n.a | 12.07–18.77 |

| 18 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. |

| 19 | n.a. | 1836.9390 | 25.9 | 5.47 | n.a. | 2014.8451 | 25.9 | 15.90 |

| MCA-quinone | 177.0197 | 6.64–8.79 | ||||||

| Adduct Mass [m/z]+ (=Mpeptide + MRA−2H) | Original RTMS [min] | Pot. Shifted RT [min] | Adduct Mass [m/z]+ (=Mpeptide + M 2×RA−2H) | Original RTMS [min] | Pot. Shifted RT [min] | Adduct Mass [m/z]+ (=Mpeptide + M3×RA−2H) | Original RTMS [min] | Pot. Shifted RT [min] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peptide No. | Nonpolar | Polar | Nonpolar | Polar | nonpolar | polar | ||||||

| 1 | 1979.1447 | n.a. | 14.4 | 21.3 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. |

| 2 | 1292.6310 | n.a. | 9.6 | 9.2 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | 9.6 | 8.3 |

| 3 | n.a. | 1032.4800 | 7.1 | 20.9 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. |

| 4 | 3066.4714 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | |

| 5 | n.a. | 22.26 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | 3390.5076 | n.a. | 12.2 |

| 6 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | 1779.6382 | 18.5 | 12.29–12.84 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. |

| 7 | n.a. | 506.2024 | n.a. | 17.4 | n.a. | 862.2908 | n.a | 16.76 | n.a. | 1224.3535 | 18.5 | 17.1 |

| 8 | 932.4530 | n.a. | 4.3 | 12.4–22.5 | 1288.5459 | 4.3 | 20.14 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | |

| 9 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | 1325.4041 | 4.3 | 20.7 −20.9 |

| 10 | 1033.5137 | n.a. | 11.6 | 24.9 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | 1751.6683 | n.a. | n.a. | 16.2 −16.3 |

| 11 | n.a. | 1275.5621 | 6.6 | 4.1 | n.a. | 1631.6575 | 6.6 | 22.32 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. |

| 12 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | 1780.7589 | n.a. | 12.5 | 11.83 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. |

| 13 | n.a. | 506.2024 | n.a | 17.4 | n.a. | 862.2908 | n.a | 16.76 | n.a. | 1224.3535 | 12.5 | 17.1 |

| 14 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a | n.a. |

| 15 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. |

| 16 | n.a. | 768.3024 | 3.5 | 7.6 | n.a. | 1124.3964 | 3.5 | 11.32 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. |

| 17 | 690.3228 | n.a. | n.a | 18.7–20.6 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | 1408.4753 | n.a. | 3.5 | 21.7 |

| 18 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. |

| 19 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | 2373.9618 | 25.9 | 9.40 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. |

| MRA | 17.2 | |||||||||||

| Adduct Mass [m/z]+ (=Mpeptide + MCHL−2H) | Original RTMS [min] | Pot. Shifted RT [min] | Adduct Mass [m/z]+ (=Mpeptide + M2×CHL−2H) | Original RTMS [min] | Pot. Shifted RT [min] | Adduct Mass [m/z]+ (=Mpeptide + M2×CHL, cycl.−2H) | Original RTMS [min] | Pot. Shifted RT [min] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peptide No. | Nonpolar | Polar | Nonpolar | Polar | Nonpolar | Polar | ||||||

| 1 | n.a | n.a | n.a | n.a | n.a | n.a | n.a | n.a | 2323.2161 | n.a | 14.4 | 16.3 |

| 2 | n.a | n.a | n.a | n.a | 1638.7141 | n.a | 9.6 | 17.3 | 1636.7076 | n.a | 9.6 | 10.1–17.9 |

| 3 | n.a | 1026.4930 | 7.1 | 9.6; 16.2 | n.a | 13.5424 | 7.1 | 4.8 | n.a | 1376.5588 | 7.1 | 19.1 |

| 4 | n.a | n.a | n.a | n.a | n.a | n.a | n.a | n.a | n.a | n.a | n.a | n.a |

| 5 | n.a | n.a | n.a | n.a | n.a | 3018.4565 | 26.0 | 22.6 | n.a | n.a | n.a | n.a |

| 6 | n.a | n.a | n.a | n.a | n.a | n.a | n.a | n.a | n.a | n.a | n.a | n.a |

| 7 | n.a | 500.2122 | n.a | 9.1–12.8 | n.a | 852.2927 | n.a | 15.9–17.6 | n.a | 850.2761 | n.a | 6.3 |

| 8 | 926.4523 | n.a | 4.3 | 20.3 | 1278.5418 | n.a | 4.3 | 18.6 | 1276.5227 | n.a | 4.3 | 14.6 |

| 9 | n.a | 601.2634 | n.a. | 5.2; 11.8 | n.a | 953.3428 | n.a. | 18.5 | 951.3271 | n.a. | 19.5 | |

| 10 | 1027.5257 | n.a | 11.6 | 16.9–17.9 | 1379.5995 | n.a | 11.6 | 12.4; 17.2 | 1377.5861 | n.a | 11.6 | 17.4–21.5 |

| 11 | n.a | 1269.5715 | 6.6 | 8.5–8.6 | n.a | n.a | n.a | n.a | n.a | 1619.6305 | 6.6 | 23.9 |

| 12 | n.a | n.a | n.a | n.a | n.a | n.a | n.a | n.a | 1768.7405 | 12.5 | 25.9 | |

| 13 | n.a | 500.2122 | n.a | 9.1–12.8 | n.a | 852.2927 | n.a | 15.9–17.6 | 850.2761 | n.a | 6.3 | |

| 14 | n.a | n.a | n.a | n.a | n.a | n.a | n.a | n.a | 3350.3818 | n.a | 17.2 | 23.3 |

| 15 | n.a | n.a | n.a | n.a | n.a | 1950.7694 | 8.9 | 14.8–16.2 | n.a | n.a | n.a | n.a |

| 16 | n.a | 726.3128 | 3.5 | 11.4 | n.a | 1114.3912 | 3.5 | 9.5–9.9 | n.a | 1112.3787 | 3.5 | 11.0 |

| 17 | 684.3307 | n.a | n.a | 6.1 | 1036.4121 | n.a | n.a | 17.6–18.9 | 1034.3961 | n.a | n.a | 16.9 |

| 18 | 1190.5847 | n.a | 20.7 | 19.7 | 1542.6652 | n.a | 20.7 | 9.9 | n.a | n.a | n.a | n.a |

| 19 | n.a | n.a | n.a | n.a | n.a | n.a | n.a | n.a | n.a | n.a | 25.9 | n.a |

| MCHL | 355.1017 | 6.4 | ||||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bock, A.; Rottner, S.; Güterbock, D.; Steinhäuser, U.; Rohn, S.; Kieserling, H. Alkaline Reaction Pathways of Phenolic Compounds with β-Lactoglobulin Peptides: Polymerization and Covalent Adduct Formation. Molecules 2025, 30, 4584. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234584

Bock A, Rottner S, Güterbock D, Steinhäuser U, Rohn S, Kieserling H. Alkaline Reaction Pathways of Phenolic Compounds with β-Lactoglobulin Peptides: Polymerization and Covalent Adduct Formation. Molecules. 2025; 30(23):4584. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234584

Chicago/Turabian StyleBock, Alina, Sarah Rottner, Daniel Güterbock, Ulrike Steinhäuser, Sascha Rohn, and Helena Kieserling. 2025. "Alkaline Reaction Pathways of Phenolic Compounds with β-Lactoglobulin Peptides: Polymerization and Covalent Adduct Formation" Molecules 30, no. 23: 4584. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234584

APA StyleBock, A., Rottner, S., Güterbock, D., Steinhäuser, U., Rohn, S., & Kieserling, H. (2025). Alkaline Reaction Pathways of Phenolic Compounds with β-Lactoglobulin Peptides: Polymerization and Covalent Adduct Formation. Molecules, 30(23), 4584. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234584