Elemental Composition and Strontium Isotopic Ratio Analysis of Industrial Hemp (Cannabis sativa L.) for Textile Applications

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Fitness for Purpose of the Analytical Method

2.1.1. AAS

2.1.2. Determination of Elements Using ICP-MS Technique

2.1.3. Determination of 87Sr/86Sr Ratio

2.2. Characterization of Hemp Samples

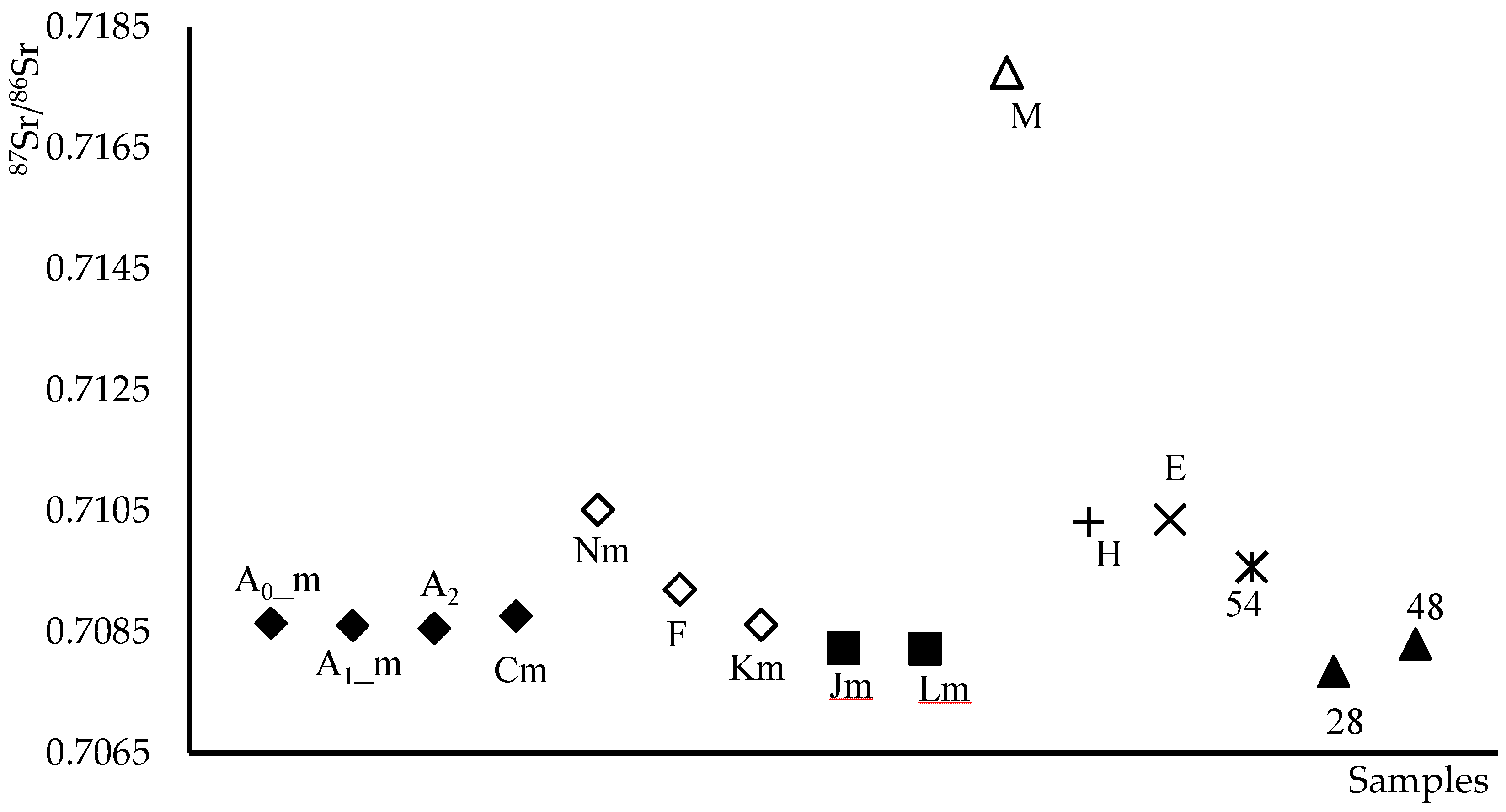

2.2.1. Determination of 87Sr/86Sr Ratio

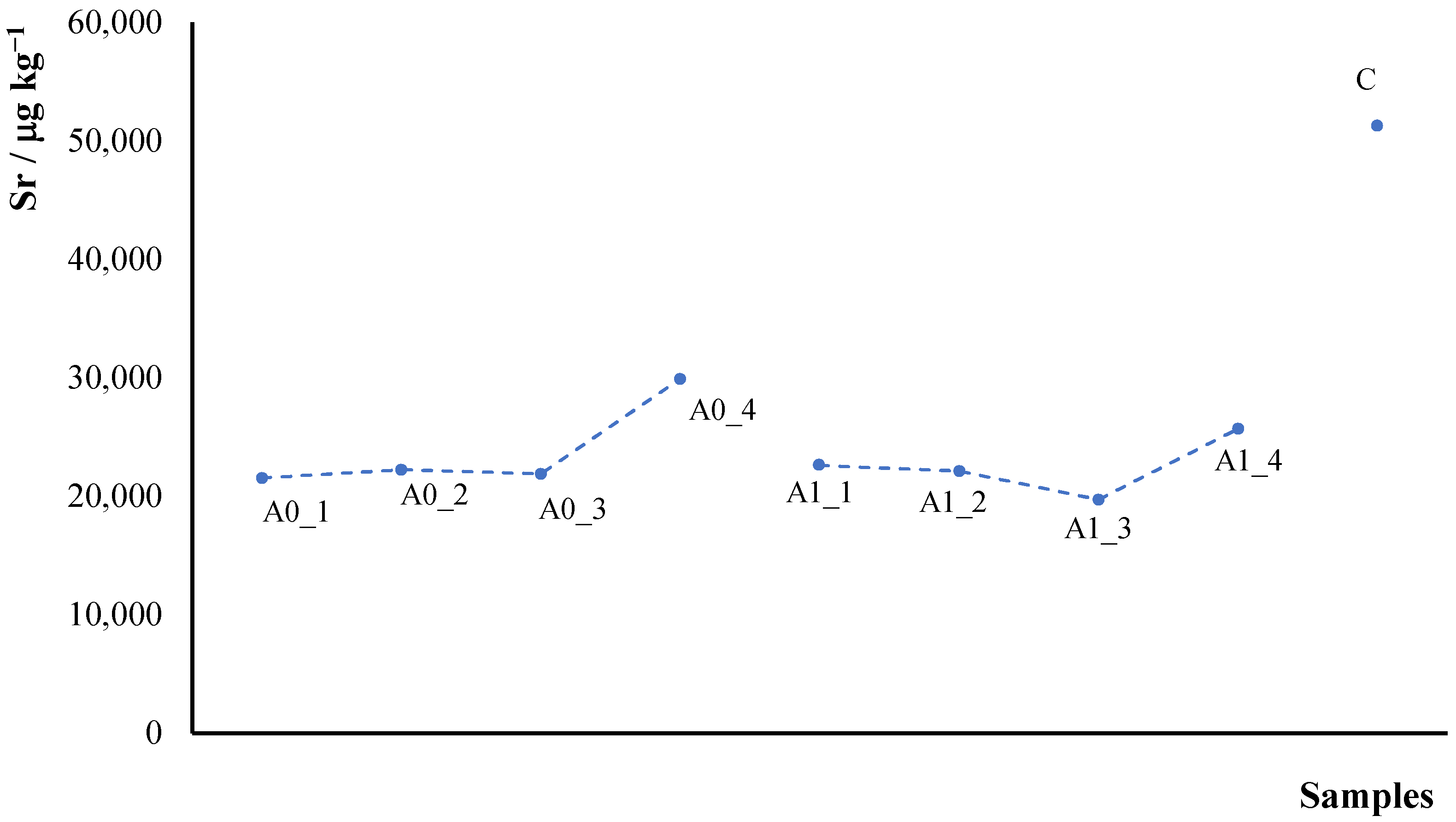

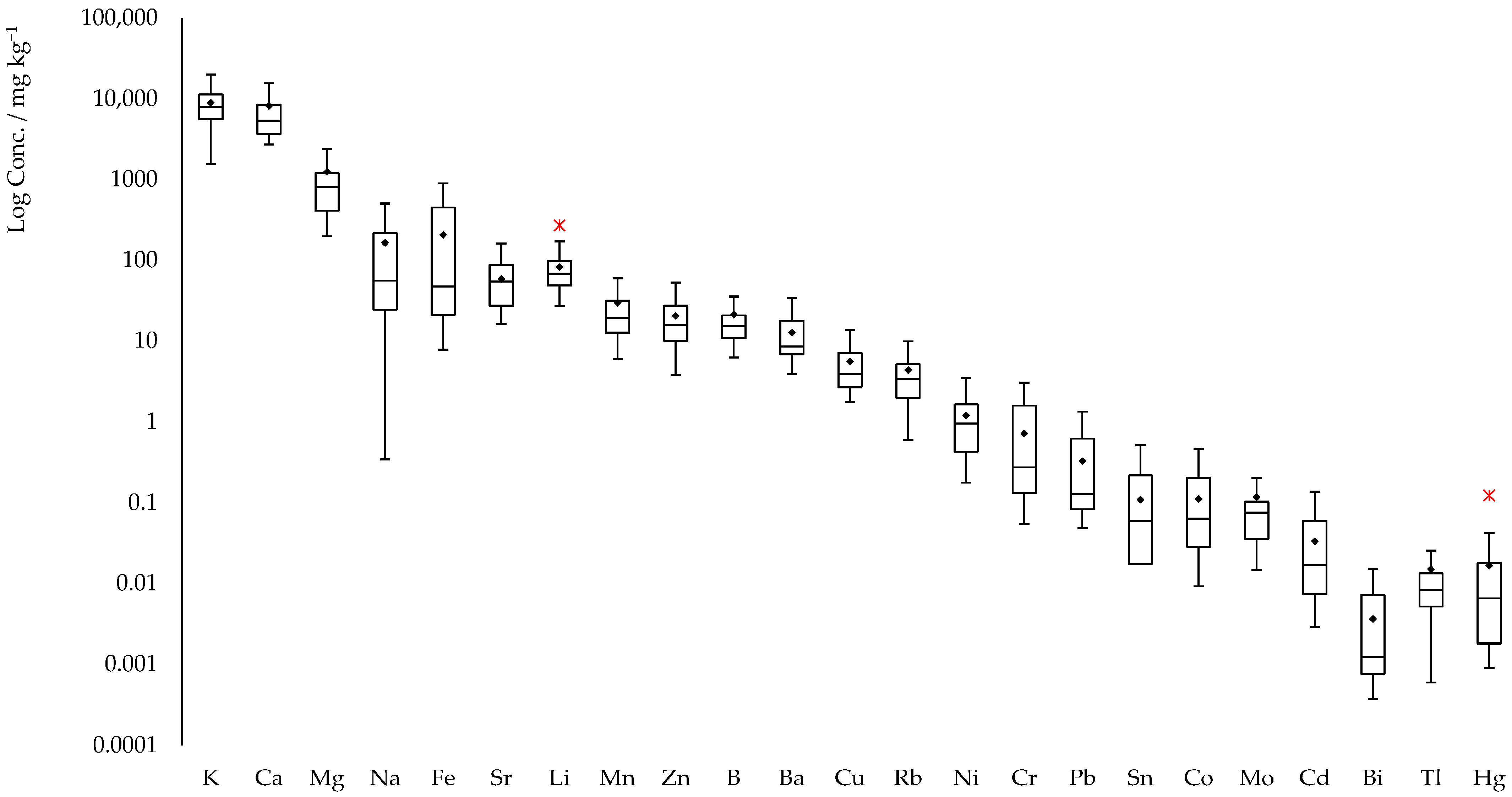

2.2.2. Elemental Content in Hemp Samples

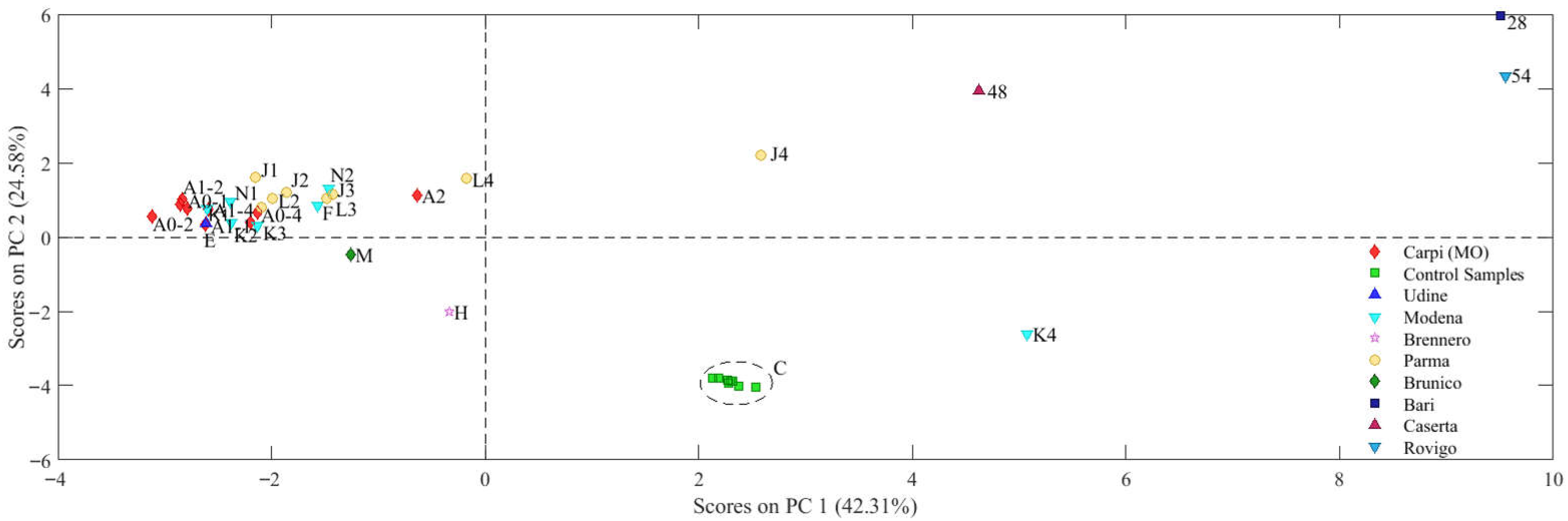

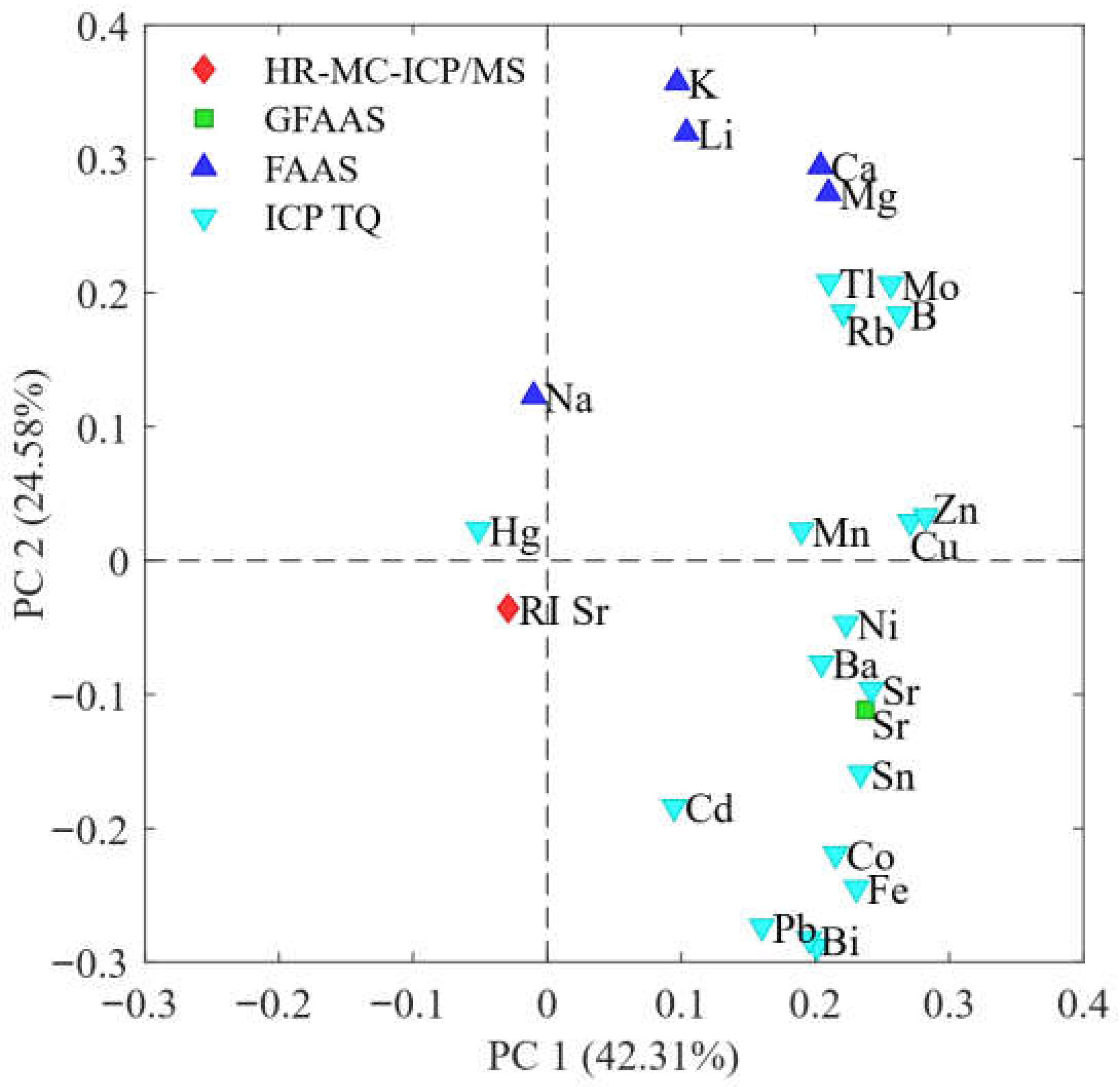

2.2.3. PCA

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Reagents and Materials

3.2. Sampling

3.3. Grinding

3.4. Sample Mineralization

3.5. Atomic Absorption Spectroscopy (AAS)

3.6. ICP-MS Mass Spectrometry

3.7. The MC-ICP-MS Mass Spectrometer

3.8. Data Analysis

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Michels, M.; Brinkmann, A.; Mußhoff, O. Economic, Ecological and Social Perspectives of Industrial Hemp Cultivation in Germany: A Qualitative Analysis. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 389, 126117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tripathi, A.; Kumar, R. Industrial Hemp for Sustainable Agriculture: A Critical Evaluation from Global and Indian Perspectives. In Cannabis/Hemp for Sustainable Agriculture and Materials; Agrawal, D.C., Kumar, R., Dhanasekaran, M., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2022; pp. 29–57. ISBN 978-981-16-8778-5. [Google Scholar]

- Visković, J.; Zheljazkov, V.D.; Sikora, V.; Noller, J.; Latković, D.; Ocamb, C.M.; Koren, A. Industrial Hemp (Cannabis sativa L.) Agronomy and Utilization: A Review. Agronomy 2023, 13, 931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United States Department of Agriculture. Italian Industrial Hemp Overview 2023—USDA Report. Available online: https://Apps.Fas.Usda.Gov/Newgainapi/Api/Report/DownloadReportByFileName?fileName=Italian%20Industrial%20Hemp%20Overview%202023_Rome_Italy_IT2023-0012 (accessed on 2 June 2025).

- Amaducci, S. Hemp Production in Italy. J. Ind. Hemp 2005, 10, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crini, G.; Lichtfouse, E.; Chanet, G.; Morin-Crini, N. Traditional and New Applications of Hemp. In Sustainable Agriculture Reviews 42: Hemp Production and Applications; Crini, G., Lichtfouse, E., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 37–87. ISBN 978-3-030-41384-2. [Google Scholar]

- Lawson, L.; Degenstein, L.M.; Bates, B.; Chute, W.; King, D.; Dolez, P.I. Cellulose Textiles from Hemp Biomass: Opportunities and Challenges. Sustainability 2022, 14, 15337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Promhuad, K.; Srisa, A.; San, H.; Laorenza, Y.; Wongphan, P.; Sodsai, J.; Tansin, K.; Phromphen, P.; Chartvivatpornchai, N.; Ngoenchai, P.; et al. Applications of Hemp Polymers and Extracts in Food, Textile and Packaging: A Review. Polymers 2022, 14, 4274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malabadi, R.B.; Kolkar, K.P.; Chalannavar, R.K. Industrial Cannabis sativa: Role of Hemp (Fiber Type) in Textile Industries. World J. Biol. Pharm. Health Sci. 2023, 16, 001–014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbash, V.A.; Yashchenko, O.V.; Yakymenko, O.S.; Zakharko, R.M.; Myshak, V.D. Preparation of Hemp Nanocellulose and Its Use to Improve the Properties of Paper for Food Packaging. Cellulose 2022, 29, 8305–8317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabels-Sneiders, M.; Platnieks, O.; Grase, L.; Gaidukovs, S. Lamination of Cast Hemp Paper with Bio-Based Plastics for Sustainable Packaging: Structure-Thermomechanical Properties Relationship and Biodegradation Studies. J. Compos. Sci. 2022, 6, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, A.; Jia, L.; Kumar, D.; Yoo, C.G. Recent Advancements in Biological Conversion of Industrial Hemp for Biofuel and Value-Added Products. Fermentation 2021, 7, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prade, T.; Svensson, S.-E.; Mattsson, J.E. Energy Balances for Biogas and Solid Biofuel Production from Industrial Hemp. Biomass Bioenergy 2012, 40, 36–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Eusanio, V.; Rivi, M.; Malferrari, D.; Marchetti, A. Optimizing Hempcrete Properties Through Thermal Treatment of Hemp Hurds for Enhanced Sustainability in Green Building. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malabadi, R.B.; Kolkar, K.P.; Chalannavar, R.K.; Vassanthini, R.; Mudigoudra, B.S. Mudigoudra Industrial Cannabis sativa: Hemp Plastic-Updates. World J. Adv. Res. Rev. 2023, 20, 715–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danielewicz, D.; Surma-Ślusarska, B. Properties and Fibre Characterisation of Bleached Hemp, Birch and Pine Pulps: A Comparison. Cellulose 2017, 24, 5173–5186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikulcová, V.; Kašpárková, V.; Humpolíček, P.; Buňková, L. Formulation, Characterization and Properties of Hemp Seed Oil and Its Emulsions. Molecules 2017, 22, 700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ostapczuk, K.; Apori, S.O.; Estrada, G.; Tian, F. Hemp Growth Factors and Extraction Methods Effect on Antimicrobial Activity of Hemp Seed Oil: A Systematic Review. Separations 2021, 8, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, G.; Kander, R. The Sustainability of Industrial Hemp: A Literature Review of Its Economic, Environmental, and Social Sustainability. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blum, J.D.; Taliaferro, E.H.; Weisse, M.T.; Holmes, R.T. Changes in Sr/Ca, Ba/Ca and 87Sr/86Sr Ratios between Trophic Levels in Two Forest Ecosystems in the Northeastern U.S.A. Biogeochemistry 2000, 49, 87–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lancellotti, L.; D’Eusanio, V.; Manzini, D.; Durante, C.; Marchetti, A.; Tassi, L. Evaluation of the Strontium Isotope Ratios in Soil–Plant–Fruit: A Comprehensive Study on Vignola Cherry (Ciliegia Di Vignola PGI). Foods 2025, 14, 1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, T.D.; Burton, J.H.; Bentley, R.A. The Characterization of Biologically Available Strontium Isotope Ratios for the Study of Prehistoric Migration. Archaeometry 2002, 44, 117–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Han, X.; Jiang, Y.; Ren, A.; Yang, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, M.; Yang, B.; Yin, M.; Peng, H.; et al. Study on Strontium Isotope Characteristics in Plants: Providing Reference for Food Production Area Traceability. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2025, 73, 20745–20755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tommasini, S.; Marchionni, S.; Tescione, I.; Casalini, M.; Braschi, E.; Avanzinelli, R.; Conticelli, S. Strontium Isotopes in Biological Material: A Key Tool for the Geographic Traceability of Foods and Humans Beings. In Behaviour of Strontium in Plants and the Environment; Gupta, D.K., Walther, C., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 145–166. ISBN 978-3-319-66574-0. [Google Scholar]

- Durante, C.; Baschieri, C.; Bertacchini, L.; Cocchi, M.; Sighinolfi, S.; Silvestri, M.; Marchetti, A. Geographical Traceability Based on 87Sr/86Sr Indicator: A First Approach for PDO Lambrusco Wines from Modena. Food Chem. 2013, 141, 2779–2787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lancellotti, L.; Sighinolfi, S.; Ulrici, A.; Maletti, L.; Durante, C.; Marchetti, A.; Tassi, L. Tracing Geographical Origin of Lambrusco PDO Wines Using Isotope Ratios of Oxygen, Boron, Strontium, Lead and Their Elemental Concentration. Curr. Res. Food Sci. 2021, 4, 807–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durante, C.; Baschieri, C.; Bertacchini, L.; Bertelli, D.; Cocchi, M.; Marchetti, A.; Manzini, D.; Papotti, G.; Sighinolfi, S. An Analytical Approach to Sr Isotope Ratio Determination in Lambrusco Wines for Geographical Traceability Purposes. Food Chem. 2015, 173, 557–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calvi, M.; Corami, F.; Radaelli, M.; Pizzini, S.; Baldini, M.; Stenni, B. Distribution Pattern of Rare Earth Elements in Four Different Industrial Hemp Cultivars (Cannabis sativa L.) Grown in Friuli Venezia Giulia, Italy. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2024, 24, 1059–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvi, M.; Bontempo, L.; Pizzini, S.; Cucinotta, L.; Camin, F.; Stenni, B. Isotopic Characterization of Italian Industrial Hemp (Cannabis sativa L.) Intended for Food Use: A First Exploratory Study. Separations 2022, 9, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durante, C.; Bertacchini, L.; Bontempo, L.; Camin, F.; Manzini, D.; Lambertini, P.; Marchetti, A.; Paolini, M. From Soil to Grape and Wine: Variation of Light and Heavy Elements Isotope Ratios. Food Chem. 2016, 210, 648–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackey, E.A.; Becker, D.A.; Oflaz, R.D.; Paul, R.L.; Greenberg, R.R.; Lindstrom, R.M.; Yu, L.L.; Wood, L.J.; Long, S.E.; Kelley, W.R.; et al. Certification of NIST Standard Reference Material 1575a Pine Needles and Results of an International Laboratory Comparison; National Institute of Standards and Technology: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2004; p. NIST SP 260-156. [Google Scholar]

- Horwitz, W.; Albert, R. The Horwitz Ratio (HorRat): A Useful Index of Method Performance with Respect to Precision. J. AOAC Int. 2006, 89, 1095–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sighinolfi, S.; Durante, C.; Lisa, L.; Tassi, L.; Marchetti, A. Influence of Chemical and Physical Variables on 87Sr/86Sr Isotope Ratios Determination for Geographical Traceability Studies in the Oenological Food Chain. Beverages 2018, 4, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ager Project. Available online: http://www.progettoager.it/ (accessed on 11 May 2025).

- Silvestri, M.; Bertacchini, L.; Durante, C.; Marchetti, A.; Salvatore, E.; Cocchi, M. Application of Data Fusion Techniques to Direct Geographical Traceability Indicators. Anal. Chim. Acta 2013, 769, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, M.; Starinsky, A.; Katz, A.; Goldstein, S.L.; Machlus, M.; Schramm, A. Strontium Isotopic, Chemical, and Sedimentological Evidence for the Evolution of Lake Lisan and the Dead Sea. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 1997, 61, 3975–3992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durante, C.; Bertacchini, L.; Cocchi, M.; Manzini, D.; Marchetti, A.; Rossi, M.C.; Sighinolfi, S.; Tassi, L. Development of 87Sr/86Sr Maps as Targeted Strategy to Support Wine Quality. Food Chem. 2018, 255, 139–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, V.; Feller, U. Heavy Metals in Crop Plants: Transport and Redistribution Processes on the Whole Plant Level. Agronomy 2015, 5, 447–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roebuck, C.J.; Klink, M.J. Phytoremediation Potential of Hemp in Metal-Contaminated Soils: Soil Analysis, Metal Uptake, and Growth Dynamics. Processes 2025, 13, 3384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flajšman, M.; Košmelj, K.; Grčman, H.; Ačko, D.K.; Zupan, M. Industrial Hemp (Cannabis sativa L.)—A Valuable Alternative Crop for Growing in Agricultural Soils Contaminated with Heavy Metals. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2023, 30, 115414–115429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosa, A.C.G.; Melo, E.S.d.P.; Junior, A.S.A.; Gondim, J.M.S.; de Sousa, A.G.; Cardoso, C.A.L.; Viana, L.F.; Carvalho, A.M.A.; Machate, D.J.; do Nascimento, V.A. Transfer of Metal(Loid)s from Soil to Leaves and Trunk Xylem Sap of Medicinal Plants and Possible Health Risk Assessment. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Zee, L.; Corzo Remigio, A.; Casey, L.W.; Purwadi, I.; Yamjabok, J.; van der Ent, A.; Kootstra, G.; Aarts, M.G.M. Quantification of Spatial Metal Accumulation Patterns in Noccaea Caerulescens by X-Ray Fluorescence Image Processing for Genetic Studies. Plant Methods 2021, 17, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petit, J.; Gulisano, A.; Dechesne, A.; Trindade, L.M. Phenotypic Variation of Cell Wall Composition and Stem Morphology in Hemp (Cannabis sativa L.): Optimization of Methods. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eboh, L.O.; Thomas, B.E. Analysis of Heavy Metal Content in Canabis Leaf and Seed Cultivated in Southern Part of Nigeria. Pak. J. Nutr. 2005, 4, 349–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ćaćić, M.; Perčin, A.; Zgorelec, Ž.; Kisić, I. Evaluation of Heavy Metals Accumulation Potential of Hemp (Cannabis sativa L.). J. Cent. Eur. Agric. 2019, 20, 700–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linger, P. Industrial Hemp (Cannabis sativa L.) Growing on Heavy Metal Contaminated Soil: FIbre Quality and Phytoremediation Potential. Ind. Crops Prod. 2002, 16, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafeiraki, E.; Kasiotis, K.M.; Nisianakis, P.; Machera, K. Macro and Trace Elements in Hemp (Cannabis sativa L.) Cultivated in Greece: Risk Assessment of Toxic Elements. Front. Chem. 2021, 9, 654308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrado, G.; Pannico, A.; Zarrelli, A.; Kyriacou, M.C.; De Pascale, S.; Rouphael, Y. Macro and Trace Element Mineral Composition of Six Hemp Varieties Grown as Microgreens. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2022, 114, 104750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korkmaz, K.; Kara, S.M.; Ozkutlu, F.; Gul, V. Monitoring of Heavy Metals and Selected Micronutrients in Hempseeds from North-Western Turkey. Afr. J. Agric. Res. 2010, 5, 463–467. [Google Scholar]

- Oeko-Tex Oeko-Tex Standard 100; OEKO-TEX: Zurich, Switzerland, 2025.

- Moore, L.J.; Murphy, T.J.; Barnes, I.L.; Paulsen, P.J. Absolute Isotopic Abundance Ratios and Atomic Weight of a Reference Sample of Strontium. J. Res. Natl. Bur. Stand. 1982, 87, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berglund, M.; Wieser, M.E. Isotopic compositions of the elements 2009 (IUPAC Technical Report). Pure Appl. Chem. 2011, 83, 397–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rivi, M.; D’Eusanio, V.; Marchetti, A.; Bonfiglioli, E.; Tassi, L. Elemental Composition and Strontium Isotopic Ratio Analysis of Industrial Hemp (Cannabis sativa L.) for Textile Applications. Molecules 2025, 30, 4573. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234573

Rivi M, D’Eusanio V, Marchetti A, Bonfiglioli E, Tassi L. Elemental Composition and Strontium Isotopic Ratio Analysis of Industrial Hemp (Cannabis sativa L.) for Textile Applications. Molecules. 2025; 30(23):4573. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234573

Chicago/Turabian StyleRivi, Mirco, Veronica D’Eusanio, Andrea Marchetti, Emilio Bonfiglioli, and Lorenzo Tassi. 2025. "Elemental Composition and Strontium Isotopic Ratio Analysis of Industrial Hemp (Cannabis sativa L.) for Textile Applications" Molecules 30, no. 23: 4573. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234573

APA StyleRivi, M., D’Eusanio, V., Marchetti, A., Bonfiglioli, E., & Tassi, L. (2025). Elemental Composition and Strontium Isotopic Ratio Analysis of Industrial Hemp (Cannabis sativa L.) for Textile Applications. Molecules, 30(23), 4573. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234573