Structural Characterization and Protective Effects of CPAP-1, an Arabinogalactan from Curcuma phaeocaulis Val., Against H2O2-Induced Oxidative Damage in HUVECs

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Extraction and Isolation of CPAP-1

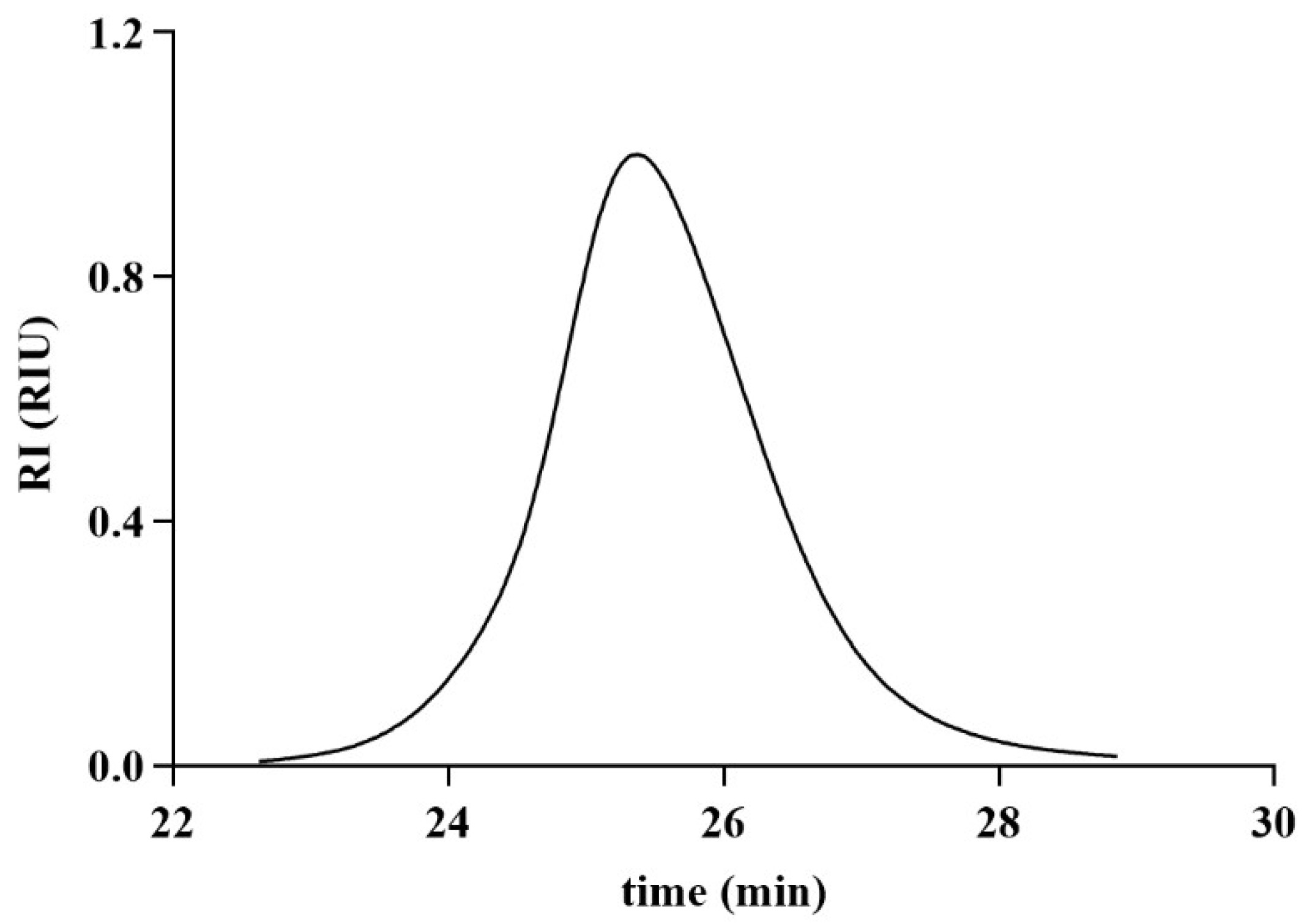

2.2. Structural Characterization of CPAP-1

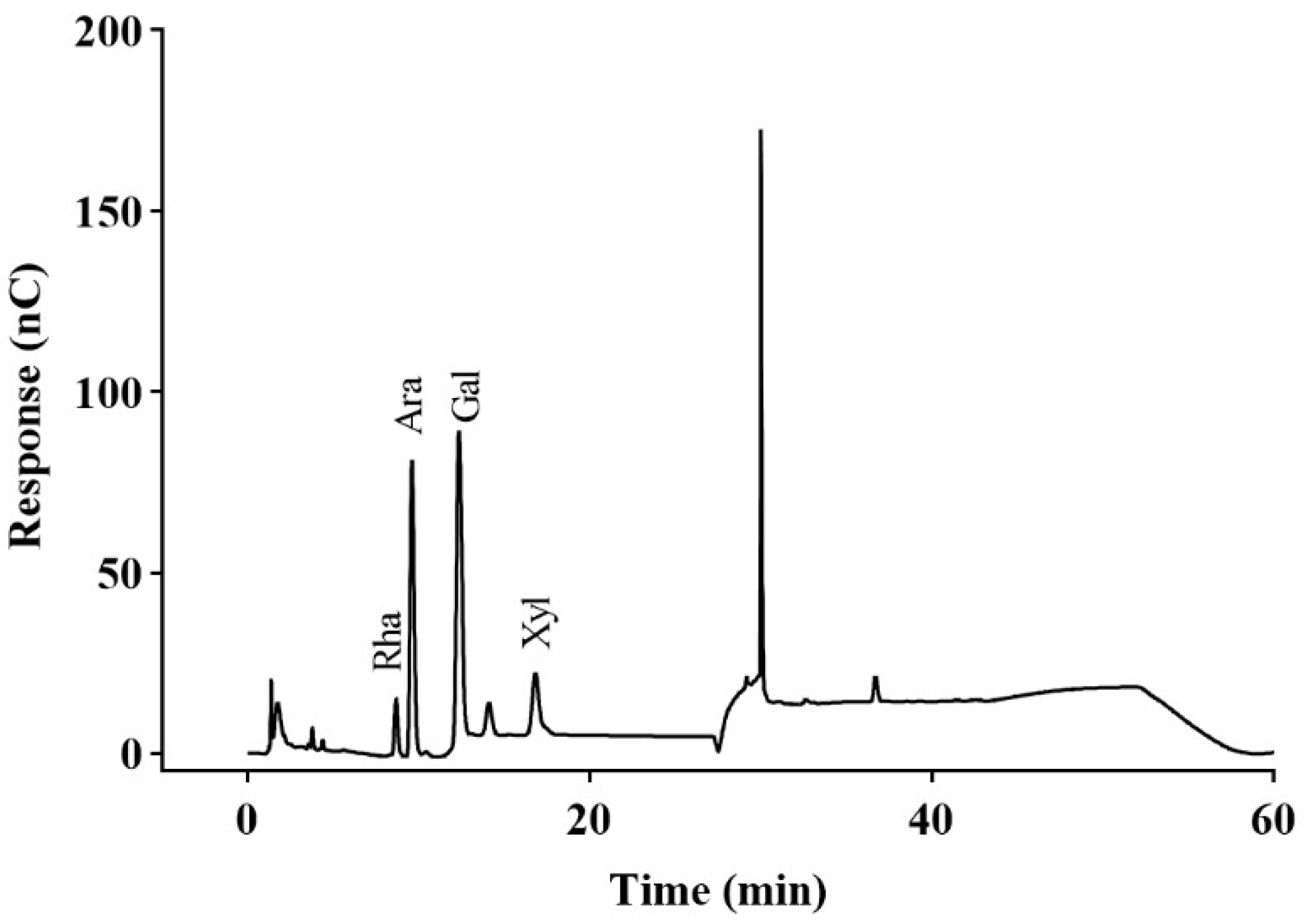

2.2.1. Monosaccharide Composition Results

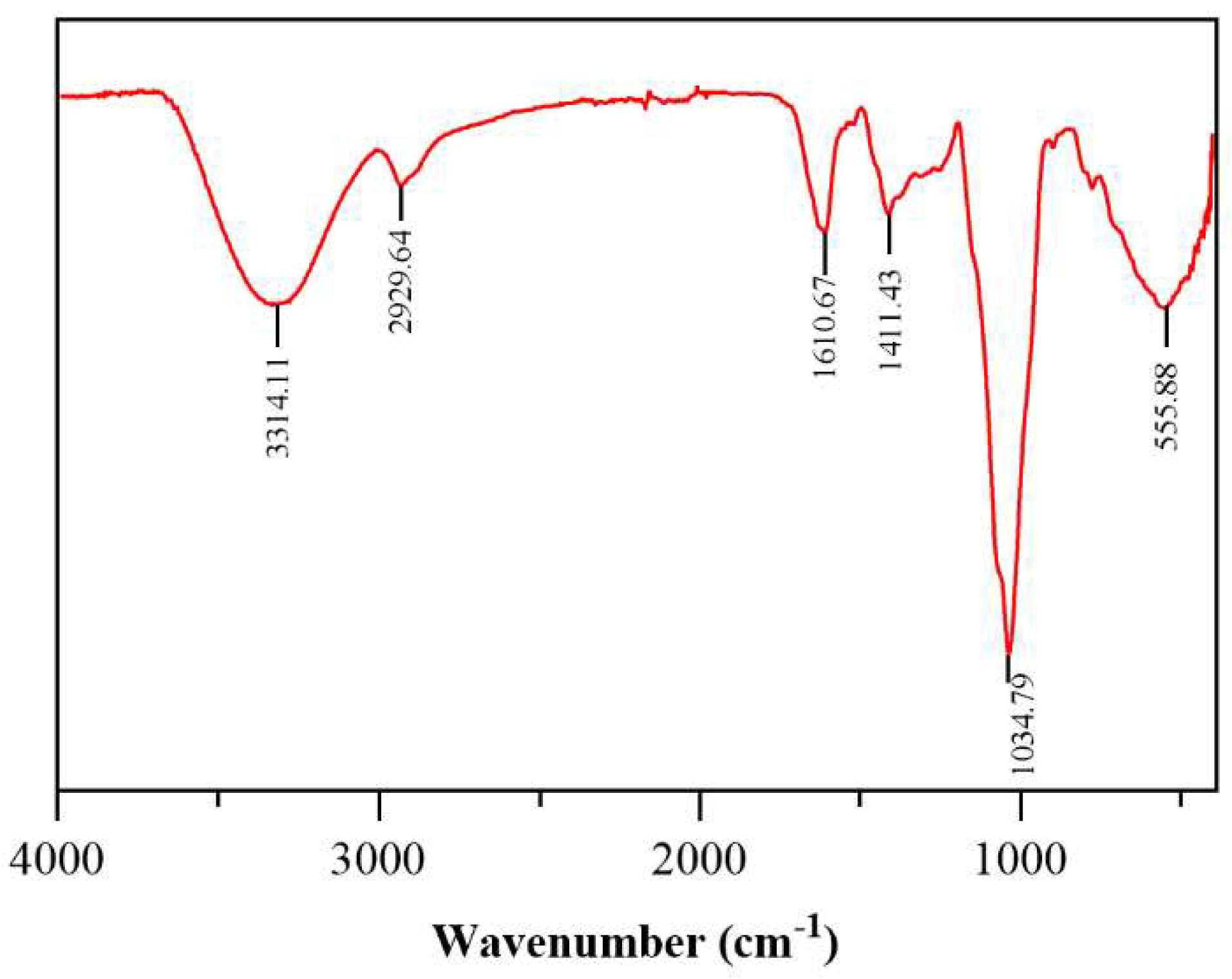

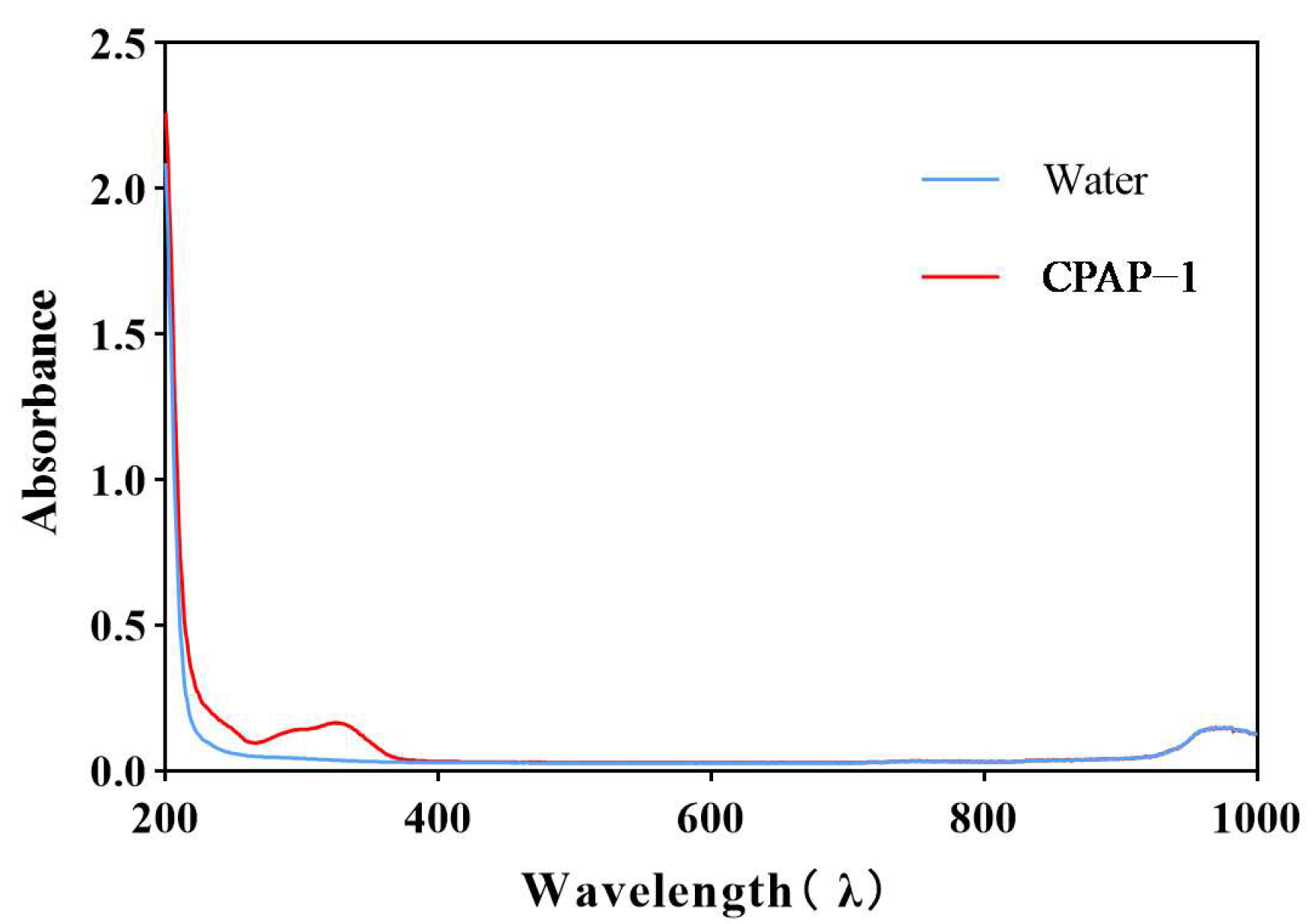

2.2.2. Infrared and Ultraviolet Scanning Results

2.2.3. Methylation Results

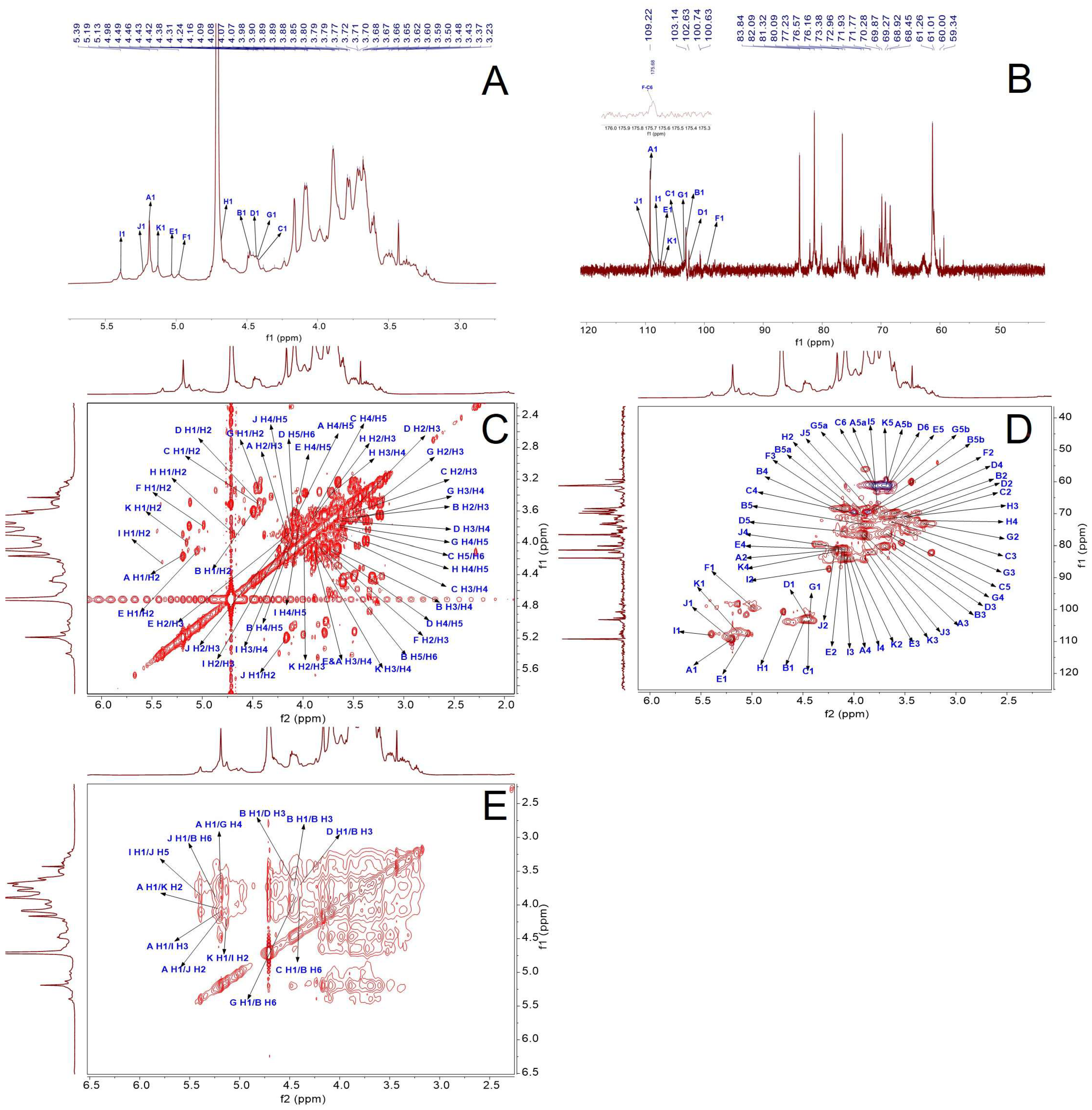

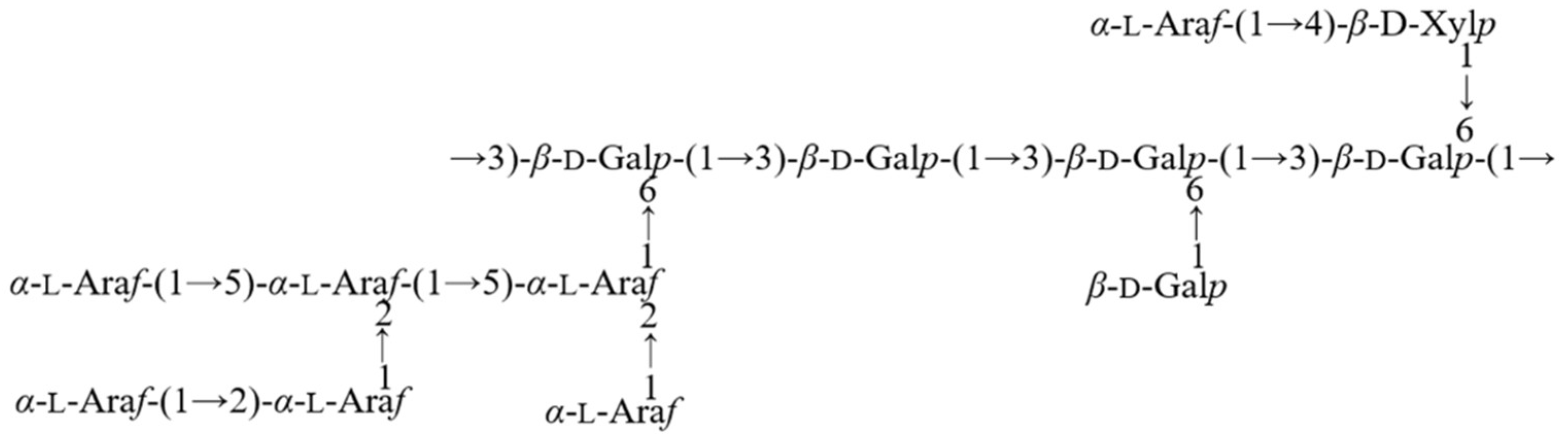

2.2.4. NMR Results

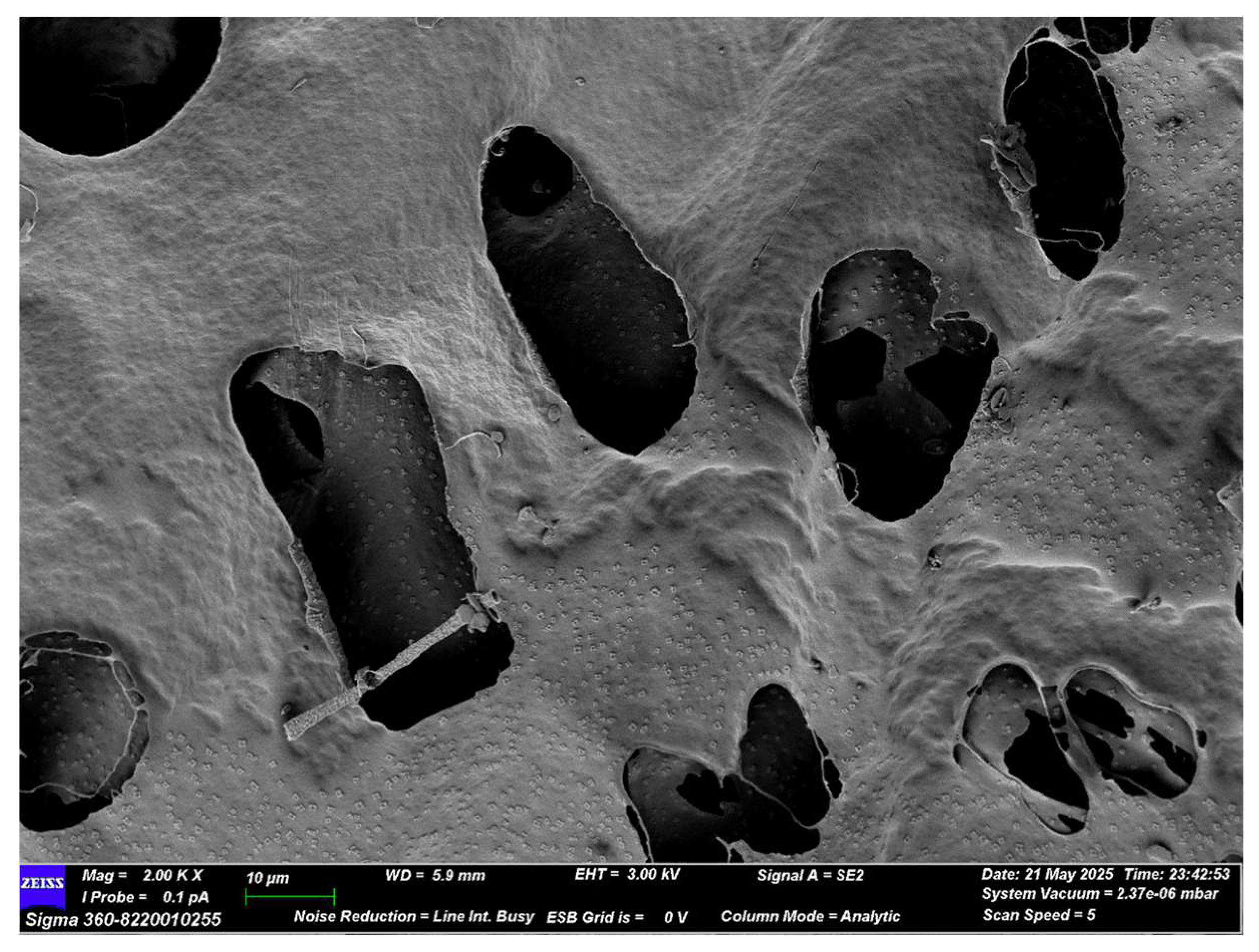

2.2.5. Electron Microscope Scanning Results

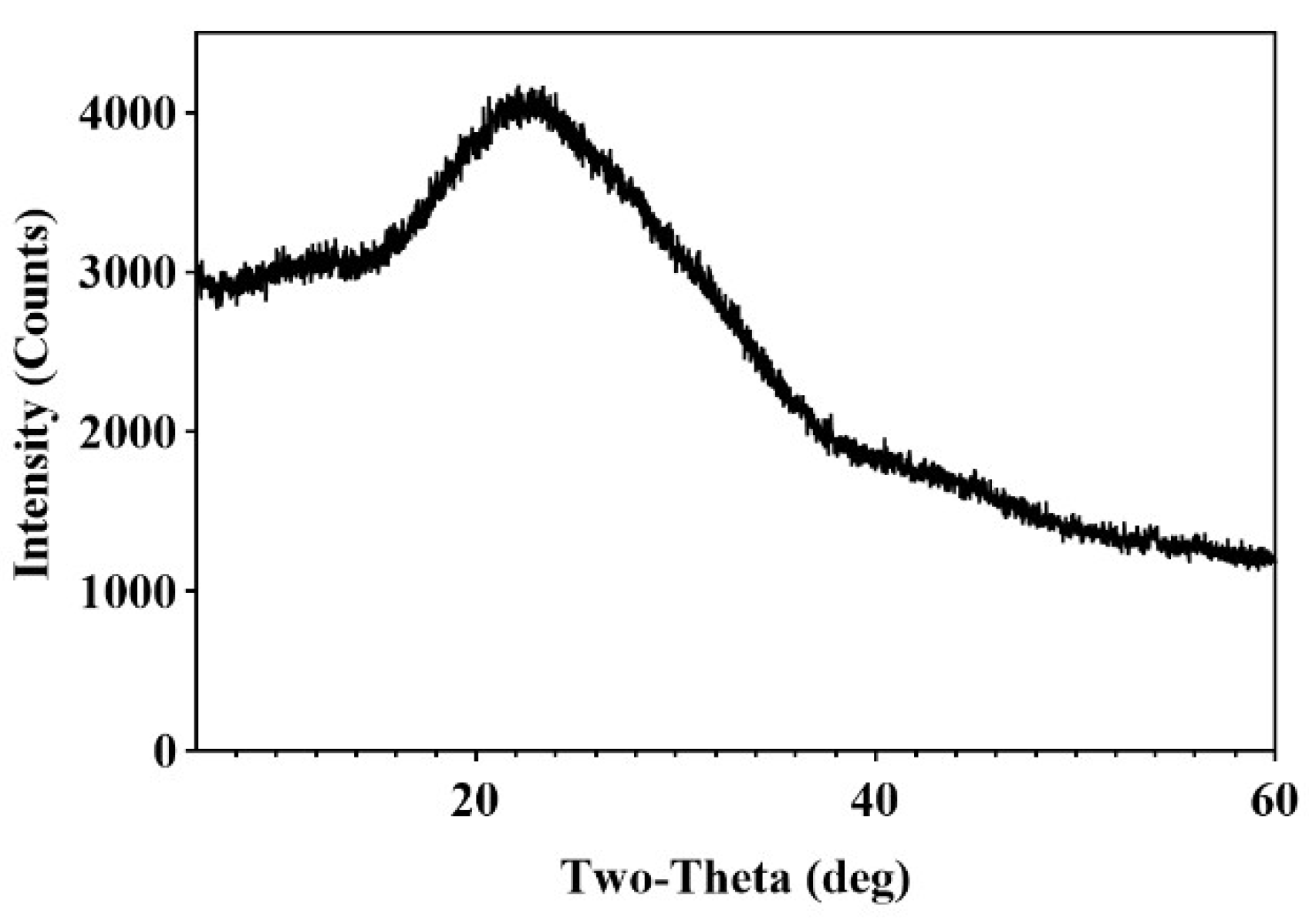

2.2.6. Results of X-Ray Diffraction Measurements

2.3. Results of Antioxidant Activity Assay

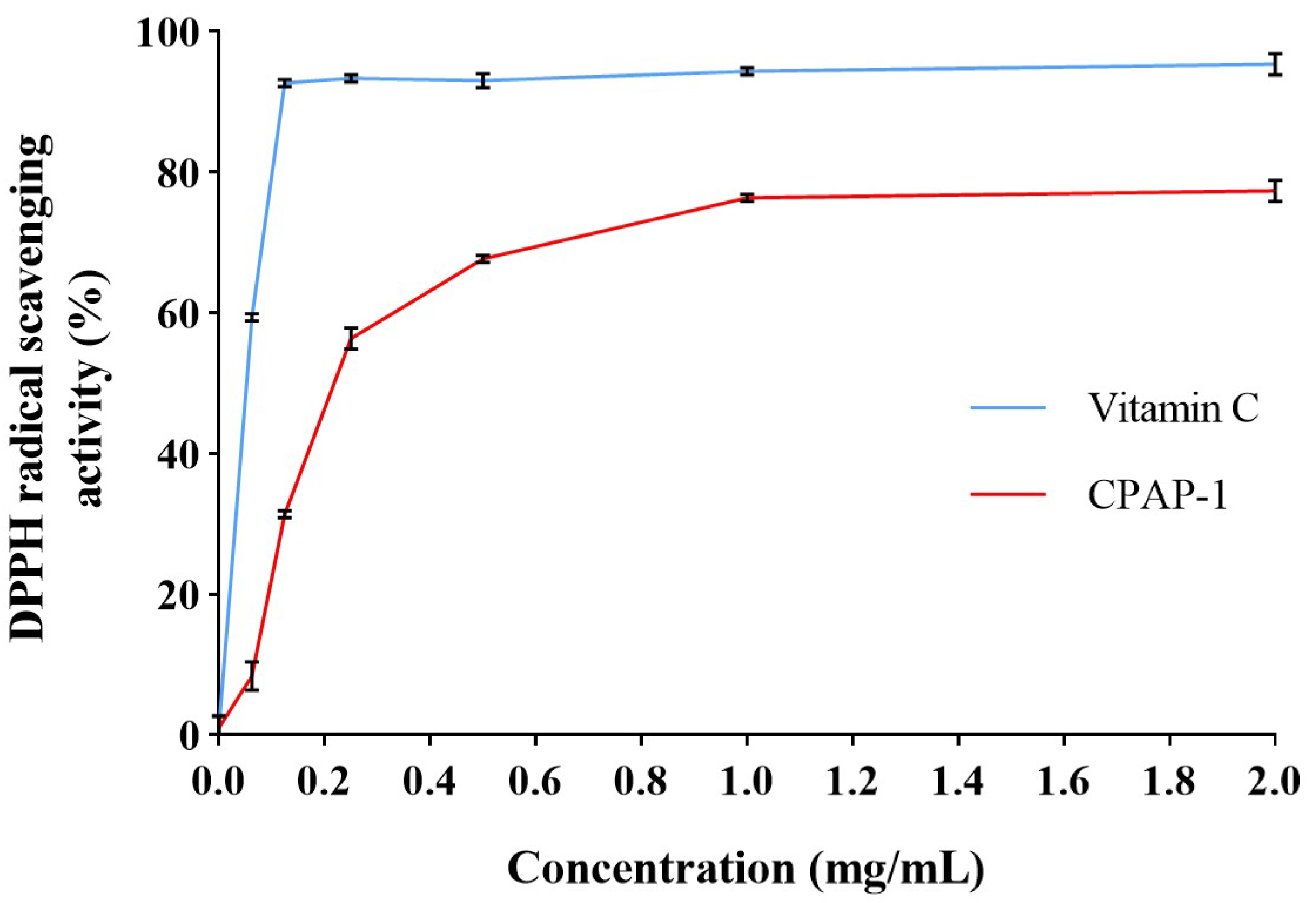

2.3.1. DPPH Radical Scavenging Activity

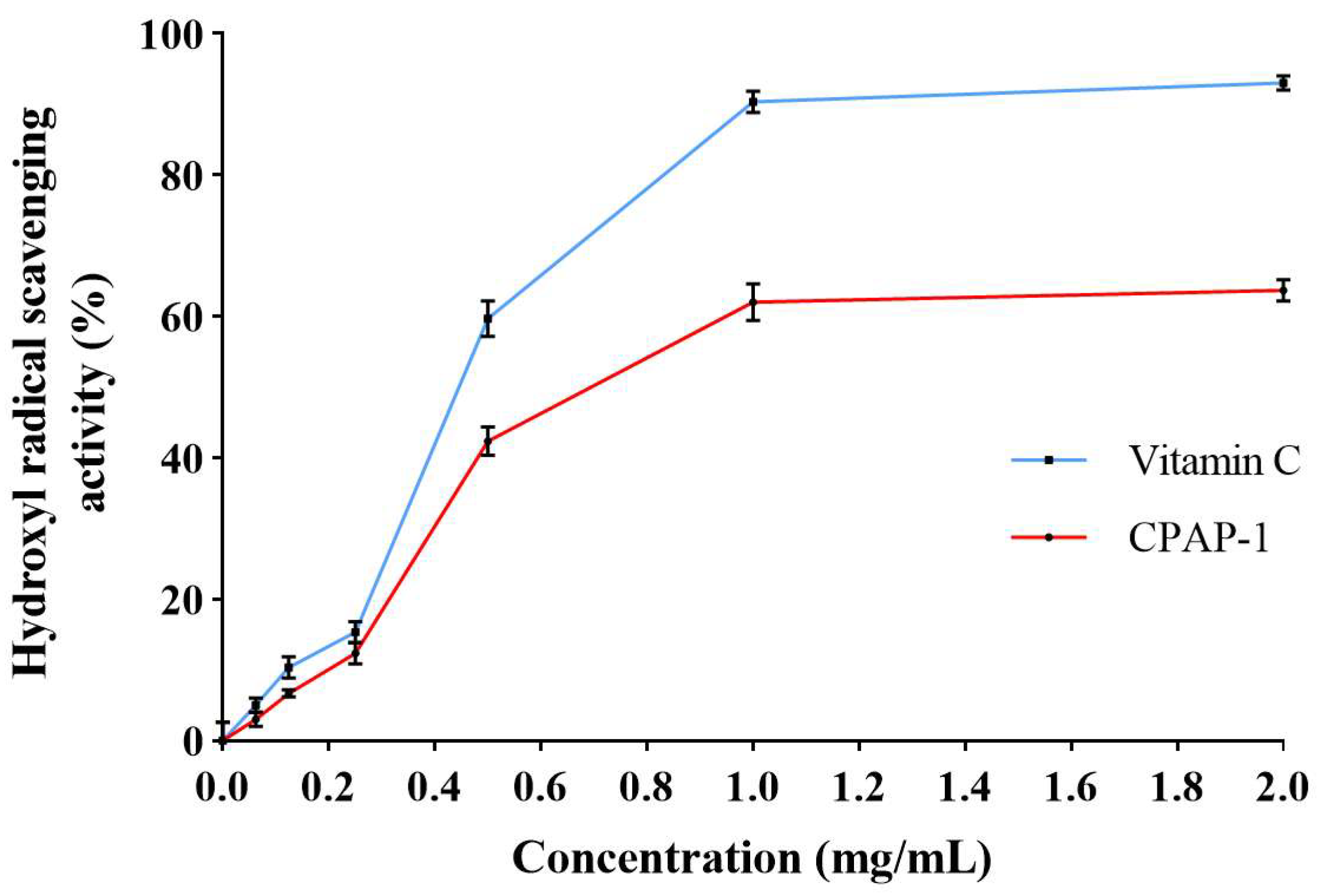

2.3.2. Scavenging of Hydroxyl Radicals

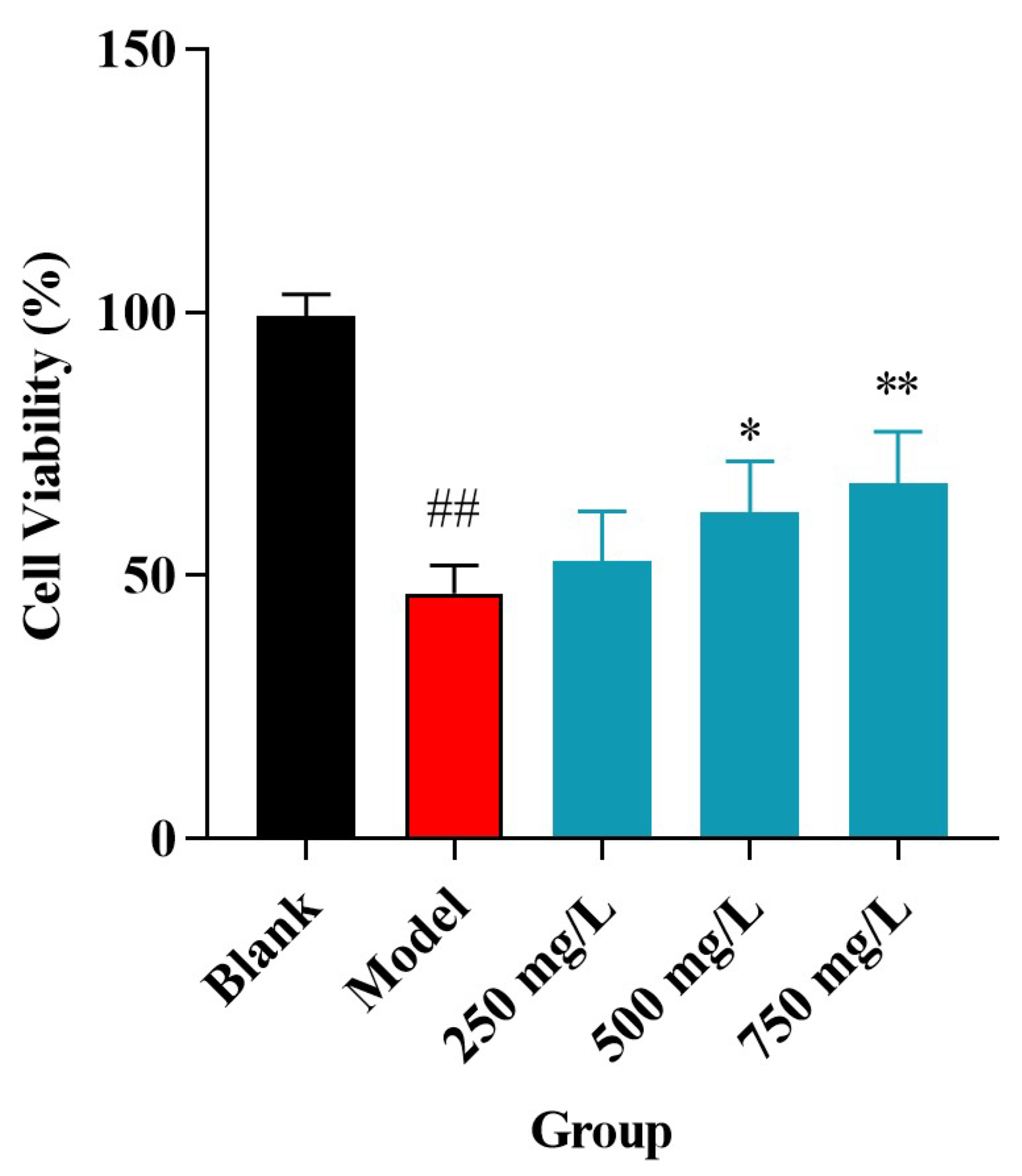

2.4. Impact of CPAP-1 on H2O2-Injured HUVEC Proliferation

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials and Experimental Devices

4.2. Polysaccharide Retrieval and Refinement

4.3. Purity Assessment and Molecular Weight Approximation

4.4. Monosaccharide Composition

4.5. Infrared Scanning Measurement

4.6. Ultraviolet Scanning Measurement

4.7. Methylation Analysis

4.8. NMR Analysis

4.9. Electron Microscope Scanning

4.10. X-Ray Diffraction Measurement

4.11. Antioxidant Activity Assay

4.11.1. DPPH Free Radical Scavenging Activity

4.11.2. Hydroxyl Radical Scavenging Activity

4.12. Tests Evaluating CPAP-1’s Protective Impact on HUVECs Subjected to H2O2-Induced Damage

4.13. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ren, L.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, T.H. Immunomodulatory activities of polysaccharides from Ganoderma on immune effector cells. Food Chem. 2021, 340, 127933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toussé, R.K.; Bossi, D.S.D.; Saah, M.B.D.; Kouam, E.M.F.; Njapndounke, B.; Tene, S.T.; Kaktcham, P.M.; Ngoufack, F.Z. Effect of Curcuma longa Rhizome Powder on Metabolic Parameters and Oxidative Stress Markers in High-Fructose and High-Fat Diet-Fed Rats. J. Food Biochem. 2024, 2024, 1445355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, J.; Dai, P.; Ren, L.; Song, B.; Chen, X.; Wang, X.; Wang, J.; Zhang, T.; Zhu, W. Apoptosis-induced anti-tumor effect of Curcuma kwangsiensis polysaccharides against human nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells. Carbohydr. Polym. 2012, 89, 1067–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, C.-X.; Zhang, W.-S.; Sun, Q.-L.; Jiang, Y.-J.; Fu, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Du, J.; Sun, Y.-X.; Tao, N.; Yao, Z. Structural characterization of a pectin-type polysaccharide from Curcuma kwangsiensis and its effects on reversing MDSC-mediated T cell suppression. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 115, 1233–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, N.; Wang, L.; Guan, J.; Tang, C.; He, N.; Zhang, W.; Fu, S. Wound healing effects of a Curcuma zedoaria polysaccharide with platelet-rich plasma exosomes assembled on chitosan/silk hydrogel sponge in a diabetic rat model. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 117, 102–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, C.-X.; Zhang, L.-J.; Xu, R.; Zhang, G.; Zhou, Y.-B.; Han, X.-Q.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, Y.-X. Structural characterization and immunostimulating activity of a levan-type fructan from Curcuma kwangsiensis. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2015, 77, 99–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; Xie, M.; Song, Y.; Wang, W.; Zhao, H.; Tian, Y.; Wang, Y.; Bai, S.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, X.; et al. Two Traditional Chinese Medicines Curcumae Radix and Curcumae Rhizoma: An Ethnopharmacology, Phytochemistry, and Pharmacology Review. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2016, 2016, 4973128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Pei, L.; Zhong, Z.; Guo, J.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, Y. Anti-tumor potential of ethanol extract of Curcuma phaeocaulis Valeton against breast cancer cells. Phytomedicine 2011, 18, 1238–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y.; Lu, C.L.; Zeng, Q.H.; Jiang, J.G. Anti-inflammatory, antioxidant and antitumor activities of ingredients of Curcuma phaeocaulis Val. Excli J. 2015, 14, 706–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Yang, Z.; Wei, J.; Su, P.; Chen, D.; Pan, W.; Zhou, W.; Zhang, K.; Zheng, X.; Lin, L. Contrastive analysis of chemical composition of essential oil from twelve Curcuma species distributed in China. Ind. Crops Prod. 2017, 108, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Bai, J.; Shao, C.; Liu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Li, X.; Yang, Y.; Xu, Y.; Wang, L. Degradation of blue honeysuckle polysaccharides, structural characteristics and antiglycation and hypoglycemic activities of degraded products. Food Res. Int. 2021, 143, 110281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, Y.; Shen, Y.; Jiang, H.; Li, D.; Li, B. Structural characterization, antioxidant and antibacterial activity of three pectin polysaccharides from blueberry. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 262, 129707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Gong, Z.; Liu, H.; Wang, J.; Wang, D.; Yang, Y.; Zhong, S. Structural characterization and anti-tumor activity in vitro of a water-soluble polysaccharide from dark brick tea. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 205, 615–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.-H.; Cao, J.-J.; Zhang, B.; Chen, H.-Q. Structural characterization, physicochemical properties and α-glucosidase inhibitory activity of polysaccharide from the fruits of wax apple. Carbohydr. Polym. 2019, 211, 227–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Shi, S.; Su, J.; Xu, Y.; Ordaz-Ortiz, J.J.; Li, N.; Wu, J.; Wang, H.; Wang, S. Structural characterization of a heteropolysaccharide from fruit of Chaenomelese speciosa (Sweet) Nakai and its antitumor activity. Carbohydr. Polym. 2020, 236, 116065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Tang, W.; Huang, X.-J.; Hu, J.-L.; Wang, J.-Q.; Yin, J.-Y.; Nie, S.-P.; Xie, M.-Y. Structural characteristic of pectin-glucuronoxylan complex from Dolichos lablab L. hull. Carbohydr. Polym. 2022, 298, 120023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, L.; Zhong, Z.-C.; Liu, Y.; Quan, H.; Lu, Y.-Z.; Zhang, E.-H.; Cai, H.; Li, L.-Q.; Lan, X.-Z. Structures and immunomodulatory activity of one galactose- and arabinose-rich polysaccharide from Sambucus adnata. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 207, 730–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakhmatov, E.G.; Makarova, E.N. Structure of KOH-soluble polysaccharides from coniferous greens of Norway spruce (Picea abies): The pectin-xylan-AGPs complex. Part 1. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 264, 130289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Lorenzo, F.; Silipo, A.; Molinaro, A.; Parrilli, M.; Schiraldi, C.; D’Agostino, A.; Izzo, E.; Rizza, L.; Bonina, A.; Bonina, F.; et al. The polysaccharide and low molecular weight components of Opuntia ficus indica cladodes: Structure and skin repairing properties. Carbohydr. Polym. 2016, 157, 128–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hui, H.; Gao, W. Structure characterization, antioxidant and hypoglycemic activity of an arabinogalactoglucan from Scutellaria baicalensis Georgi. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 207, 346–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, P.; Wang, Q.; Wang, Q.; Chen, J.; He, L.; Qin, Z.; Li, S.; Han, J.; Yao, X.; Yu, Y.; et al. Evaluation of the anti-atherosclerotic effect for Allium macrostemon Bge. Polysaccharides and structural characterization of its a newly active fructan. Carbohydr. Polym. 2024, 340, 122289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Gan, J.; Yan, B.; Wang, P.; Wu, H.; Huang, C. Polysaccharides from Russula: A review on extraction, purification, and bioactivities. Front. Nutr. 2024, 11, 1406817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Wang, R.; Zhou, Y.; Cao, H.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Tan, M.; Xiang, Z. Structural characterization of a polysaccharide from Thesium chinense Turcz and its immunomodulatory activities. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 329, 147847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizzino, G.; Irrera, N.; Cucinotta, M.; Pallio, G.; Mannino, F.; Arcoraci, V.; Squadrito, F.; Altavilla, D.; Bitto, A. Oxidative Stress: Harms and Benefits for Human Health. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2017, 2017, 8416763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teleanu, D.M.; Niculescu, A.G.; Lungu, I.I.; Radu, C.I.; Vladâcenco, O.; Roza, E.; Costăchescu, B.; Grumezescu, A.M.; Teleanu, R.I. An Overview of Oxidative Stress, Neuroinflammation, and Neurodegenerative Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 5938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inagami, T.; Naruse, M.; Hoover, R. Endothelium as an endocrine organ. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 1995, 57, 171–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vergallo, R.; Crea, F. Atherosclerotic Plaque Disruption and Healing. Eur. Heart J. 2020, 41, 4079–4080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Ilyas, I.; Little, P.J.; Li, H.; Kamato, D.; Zheng, X.; Luo, S.; Li, Z.; Liu, P.; Han, J.; et al. Endothelial Dysfunction in Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Diseases and Beyond: From Mechanism to Pharmacotherapies. Pharmacol. Rev. 2021, 73, 924–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Qiu, Y.; Pei, X.; Chitteti, R.; Steiner, R.; Zhang, S.; Jin, Z.G. Endothelial specific YY1 deletion restricts tumor angiogenesis and tumor growth. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 20493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Ma, X.; Ilyas, I.; Zheng, X.; Luo, S.; Little, P.J.; Kamato, D.; Sahebkar, A.; Wu, W.; Weng, J.; et al. Impact of sodium glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors on atherosclerosis: From pharmacology to pre-clinical and clinical therapeutics. Theranostics 2021, 11, 4502–4515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, C.; Zhang, J.; Chen, H.; Zhuge, Y.; Chen, H.; Qian, F.; Zhou, K.; Niu, C.; Wang, F.; Qiu, H.; et al. Endothelial cell pyroptosis plays an important role in Kawasaki disease via HMGB1/RAGE/cathespin B signaling pathway and NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Cell Death Dis. 2019, 10, 778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higashi, Y. Roles of Oxidative Stress and Inflammation in Vascular Endothelial Dysfunction-Related Disease. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 1958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zenin, V.; Ivanova, J.; Pugovkina, N.; Shatrova, A.; Aksenov, N.; Tyuryaeva, I.; Kirpichnikova, K.; Kuneev, I.; Zhuravlev, A.; Osyaeva, E.; et al. Resistance to H2O2-induced oxidative stress in human cells of different phenotypes. Redox Biol. 2022, 50, 102245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ransy, C.; Vaz, C.; Lombès, A.; Bouillaud, F. Use of H2O2 to Cause Oxidative Stress, the Catalase Issue. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 9149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyerinde, A.S.; Selvaraju, V.; Boersma, M.; Babu, J.R.; Geetha, T. Effect of H2O2 induced oxidative stress on volatile organic compounds in differentiated 3T3-L1 cells. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 2597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kou, R.; Mi, F.; Qiu, J.; Zeng, S.; Peng, C.; Liu, F.; Xiong, L. Integrated tandem ultrafiltration membrane technology for separating polysaccharides from Curcuma longa: Structure characterization, separation mechanisms, and protective effects on HUVECs. Food Chem. 2025, 488, 144918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Zhao, P.; Qu, Z.; Bai, D.; Gao, X.; Zhao, C.; Chen, J.; Gao, W. Physicochemical characterizations of polysaccharides from Angelica Sinensis Radix under different drying methods for various applications. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 121, 381–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zheng, Y.; Lai, Z.; Hu, X.; Wang, L.; Wang, X.; Li, Z.; Gao, M.; Yang, Y.; Wang, Q.; et al. Effect of monosaccharide composition and proportion on the bioactivity of polysaccharides: A review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 254 Pt 2, 127955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, T.; Huang, Q.L.; Wong, K.H.; Yang, H. Structure, molecular conformation, and immunomodulatory activity of four polysaccharide fractions from Lignosus rhinocerotis sclerotia. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2017, 94, 423–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.M.; Huang, Q.L.; Ling, C.Q. Water-soluble yeast β-glucan fractions with different molecular weights: Extraction and separation by acidolysis assisted-size exclusion chromatography and their association with proliferative activity. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 123, 269–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Zhang, B.; Xiao, J.; Huang, Q.; Li, C.; Fu, X. Physicochemical, functional, and biological properties of water-soluble polysaccharides from Rosa roxburghii Tratt fruit. Food Chem. 2018, 249, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.Q.; Huang, R.M.; Wen, P.; Song, Y.; He, B.L.; Tan, J.L.; Hao, H.L.; Wang, H. Structural characterization and immunological activity of pectin polysaccharide from kiwano (Cucumis metuliferus) peels. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021, 254, 117371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Huang, G.; Chen, G. Extraction, structural analysis, derivatization and antioxidant activity of polysaccharide from Chinese yam. Food Chem. 2021, 361, 130089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Hu, P.; Zhang, X.; Li, X. Chemical structure elucidation of an inulin-type fructan isolated from Lobelia chinensis lour with anti-obesity activity on diet-induced mice. Carbohydr. Polym. 2020, 240, 116357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Li, C.; Ding, J.; Lai, P.F.H.; Xia, Y.; Ai, L. Structural features and emulsifying stability of a highly branched arabinogalactan from immature peach (Prunus persica) exudates. Food Hydrocoll. 2020, 104, 105721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Li, C.; Bai, L.; Wu, J.; Bo, R.; Ye, M.; Huang, L.; Chen, H.; Rui, W. Structural differences of polysaccharides from Astragalus before and after honey processing and their effects on colitis mice. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 182, 815–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Yao, J.; Wang, F.; Wu, D.; Zhang, R. Extraction, isolation, structural characterization, and antioxidant activity of polysaccharides from elderberry fruit. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 947706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.M.; Zhu, L.; Qu, Y.H.; Qu, X.; Mu, M.X.; Zhang, M.S.; Muneer, G.; Zhou, Y.F.; Sun, L. Analyses of active antioxidant polysaccharides from four edible mushrooms. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 123, 945–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ning, X.; Liu, Y.; Jia, M.; Wang, Q.; Sun, Z.; Ji, L.; Mayo, K.H.; Zhou, Y.; Sun, L. Pectic polysaccharides from Radix Sophorae Tonkinensis exhibit significant antioxidant effects. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021, 262, 117925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.L.; Wang, R.F.; Zhang, S.P.; Zhu, W.J.; Tang, J.; Liu, J.F.; Chen, P.; Zhang, D.M.; Ye, W.C.; Zheng, Y.L. Polysaccharides from Panax japonicus CA Meyer and their antioxidant activities. Carbohydr. Polym. 2014, 101, 386–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Sugar Derivatives | Diagnostic Fragments (m/z) | Relative Molecular Weight | mol % | Deduced Residues |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1,5-di-O-acetyl-6-deoxy-2,3,4-tri-O-methyl mannitol | 59, 72, 89, 102, 115, 118, 131, 145, 162, 175 | 418 | 2.10% | t *-Rha(p) |

| 1,4-di-O-acetyl-2,3,5-tri-O-methyl arabinitol | 71, 87, 102, 118, 129, 145, 161 | 7678 | 38.47% | t-Ara(f) |

| 1,2,4-tri-O-acetyl-3,5-di-O-methyl arabinitol | 88, 101, 129, 130, 161, 190, 233 | 375 | 1.88% | 2-Ara(f) |

| 1,3,4-tri-O-acetyl-2,5-di-O-methyl arabinitol | 87, 99, 113, 118, 129, 201, 233 | 1182 | 5.92% | 3-Ara(f) |

| 1,5-di-O-acetyl-2,3,4,6-tetra-O-methyl galactitol | 87, 102, 118, 129, 145, 161, 162, 205 | 2269 | 11.37% | t-Gal(p) |

| 1,4,5-tri-O-acetyl-2,3-di-O-methyl xylitol | 87, 102, 118, 129, 162, 189 | 1004 | 5.03% | 4-Xyl(p) |

| 1,3,5-tri-O-acetyl-2,4,6-tri-O-methyl galactitol | 87, 101, 118, 129, 161, 202, 234 | 1282 | 6.42% | 3-Gal(p) |

| 1,4,5-tri-O-acetyl-2,3,6-tri-O-methyl glucitol | 87, 102, 113, 118, 129, 162, 233 | 1008 | 5.05% | 4-Glc(p)-UA |

| 1,2,4,5-tetra-O-acetyl-3-O-methyl arabinitol | 87, 88, 129, 130, 189, 190 | 255 | 1.28% | 2,5-Ara(f) |

| 1,2,3,4,5-penta-O-acetyl arabinitol | 85, 86, 103, 115, 116, 128, 145, 146, 159, 188, 201, 218, 290 | 756 | 3.79% | 2,3,5-Ara(f) |

| 1,3,5,6-tetra-O-acetyl-2,4-di-O-methyl galactitol | 87, 101, 118, 129, 160, 189, 234 | 3733 | 18.70% | 3,6-Gal(p) |

| Code | Glycosyl Residues | Chemical Shifts (ppm) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1/C1 | H2/C2 | H3/C3 | H4/C4 | H5/C5 | H6/C6 | ||

| Residue A | α-l-Araf-(1→ | 5.19 | 4.16 | 3.89 | 4.08 | 3.68, 3.78 | / |

| 109.22 | 81.32 | 76.57 | 83.84 | 61.26 | / | ||

| Residue B | →3,6)-β-d-Galp-(1→ | 4.48 | 3.6 | 3.7 | 4.09 | 3.89 | 3.87, 3.99 |

| 103.14 | 69.87 | 80.09 | 68.45 | 73.38 | 69.62 | ||

| Residue C | β-d-Galp-(1→ | 4.41 | 3.49 | 3.62 | 3.89 | 3.66 | 3.79 |

| 103.57 | 71.31 | 72.74 | 70.74 | 75.85 | 61.74 | ||

| Residue D | →3)-β-d-Galp-(1→ | 4.44 | 3.5 | 3.61 | 3.72 | 4.09 | 3.63 |

| 102.63 | 71.77 | 80.36 | 70.02 | 75.52 | 61.01 | ||

| Residue E | →3)-α-l-Araf-(1→ | 5.03 | 4.11 | 3.89 | 4.09 | 3.63 | / |

| 107.47 | 80.86 | 83.99 | 81.03 | 60.91 | / | ||

| Residue F | →4)-α-d-GlcpA-(1→ | 4.98 | 3.78 | 4.08 | n.d | n.d * | / |

| 99.55 | 68.87 | 68.15 | n.d | n.d | 175.68 | ||

| Residue G | →4)-β-d-Xylp-(1→ | 4.43 | 3.31 | 3.5 | 3.68 | 3.67, 3.77 | / |

| 103.31 | 73.46 | 75.08 | 76.47 | 63.27 | / | ||

| Residue H | β-l-Rhap-(1→ | 4.69 | 3.92 | 3.71 | 3.37 | 3.98 | 1.2 |

| 100.68 | 68.61 | 70.47 | 72.00 | n.d | 16.54 | ||

| Residue I | →2,3,5)-α-l-Araf-(1→ | 5.39 | 4.24 | 4.13 | 4.05 | 3.76 | / |

| 107.74 | 87.28 | 81.93 | 84.08 | 66.7 | / | ||

| Residue J | →2,5)-α-l-Araf-(1→ | 5.24 | 4.17 | 3.95 | 4.14 | 3.85 | / |

| 108.42 | 82.24 | 76.95 | 81.96 | 68.92 | / | ||

| Residue K | →2)-α-l-Araf-(1→ | 5.13 | 4.01 | 3.86 | 4.19 | 3.69 | / |

| 106.98 | 83.98 | 82.08 | 81.87 | 59.34 | / | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Long, Y.; Yi, S.; Zhou, H.; Chen, F.; Guo, Y.; Guo, L. Structural Characterization and Protective Effects of CPAP-1, an Arabinogalactan from Curcuma phaeocaulis Val., Against H2O2-Induced Oxidative Damage in HUVECs. Molecules 2025, 30, 4340. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30224340

Long Y, Yi S, Zhou H, Chen F, Guo Y, Guo L. Structural Characterization and Protective Effects of CPAP-1, an Arabinogalactan from Curcuma phaeocaulis Val., Against H2O2-Induced Oxidative Damage in HUVECs. Molecules. 2025; 30(22):4340. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30224340

Chicago/Turabian StyleLong, Yuhao, Sirui Yi, Huizhi Zhou, Fangrou Chen, Yiping Guo, and Li Guo. 2025. "Structural Characterization and Protective Effects of CPAP-1, an Arabinogalactan from Curcuma phaeocaulis Val., Against H2O2-Induced Oxidative Damage in HUVECs" Molecules 30, no. 22: 4340. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30224340

APA StyleLong, Y., Yi, S., Zhou, H., Chen, F., Guo, Y., & Guo, L. (2025). Structural Characterization and Protective Effects of CPAP-1, an Arabinogalactan from Curcuma phaeocaulis Val., Against H2O2-Induced Oxidative Damage in HUVECs. Molecules, 30(22), 4340. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30224340