DFT Insights into NHC-Catalyzed Switchable [3+4] and [3+2] Annulations of Isatin-Derived Enals and N-Sulfonyl Ketimines: Mechanism, Regio- and Stereoselectivity

Abstract

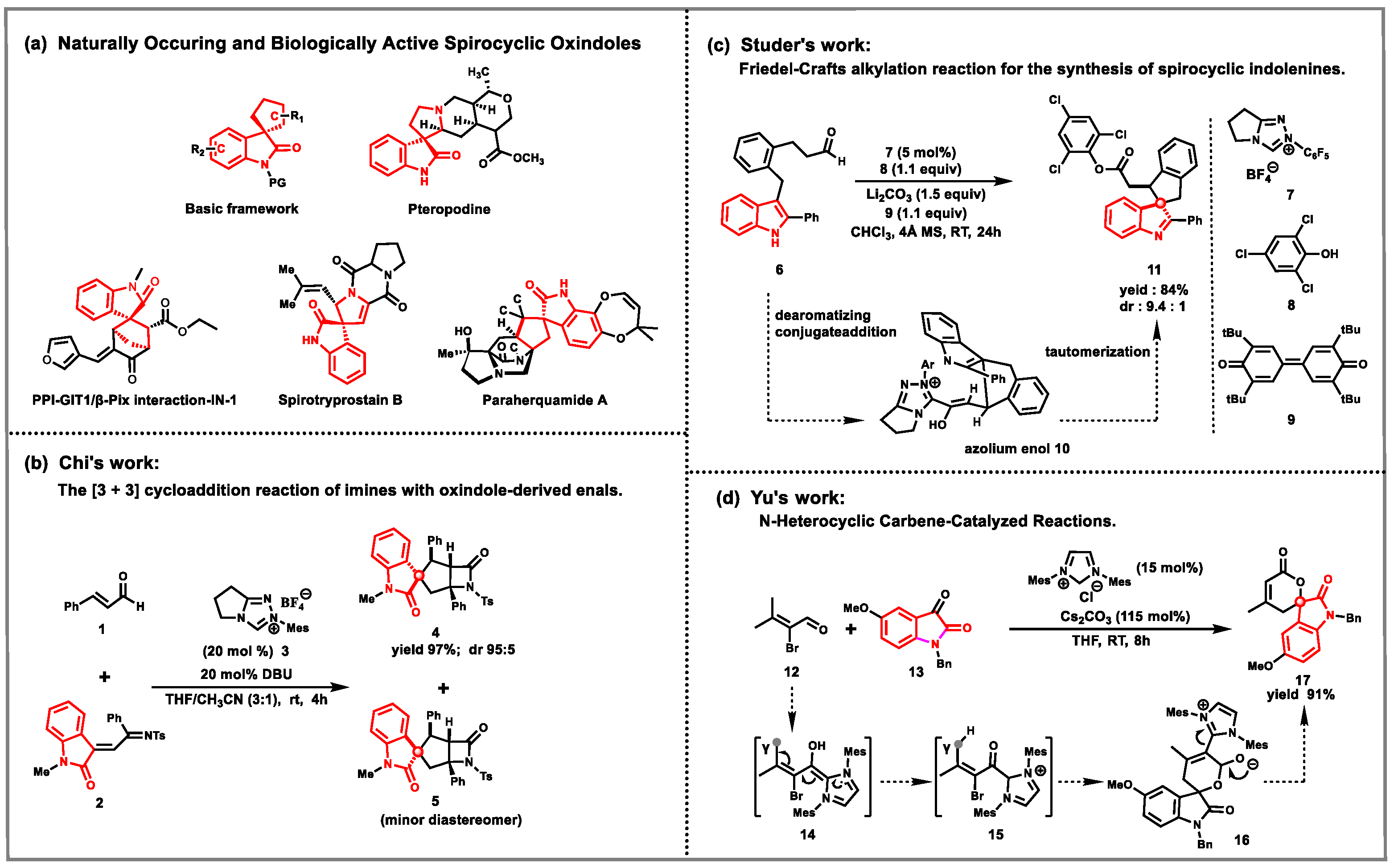

1. Introduction

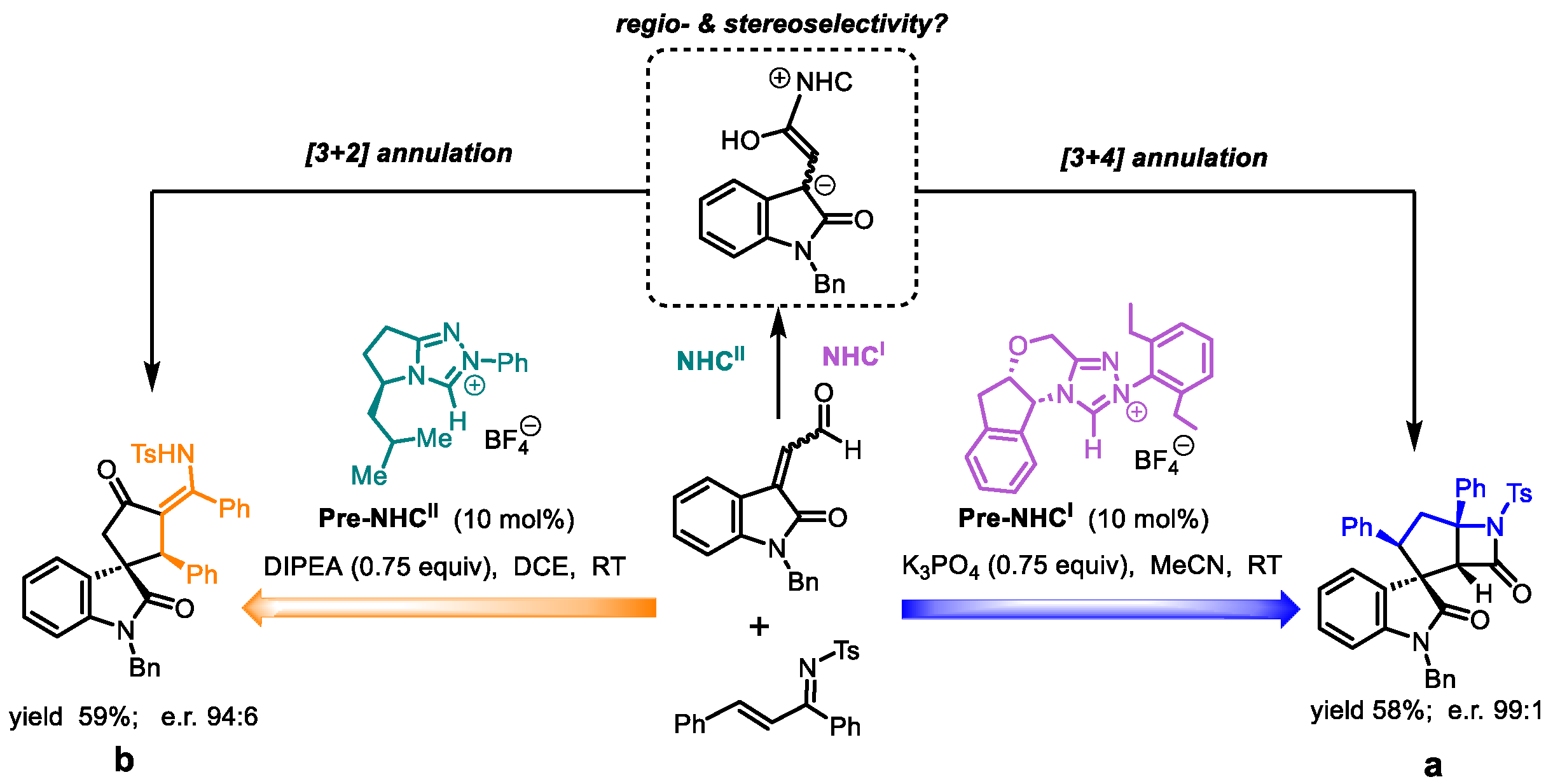

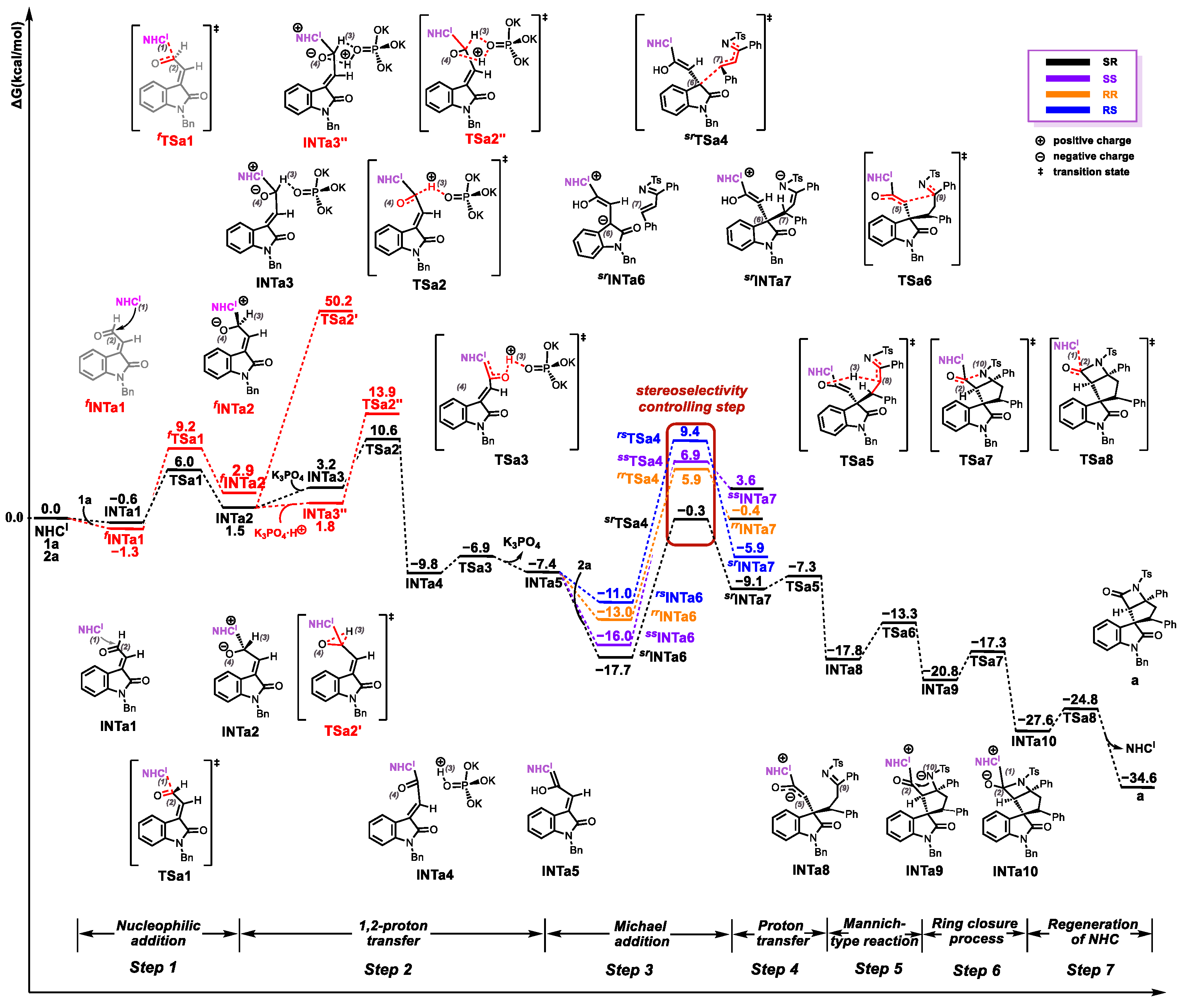

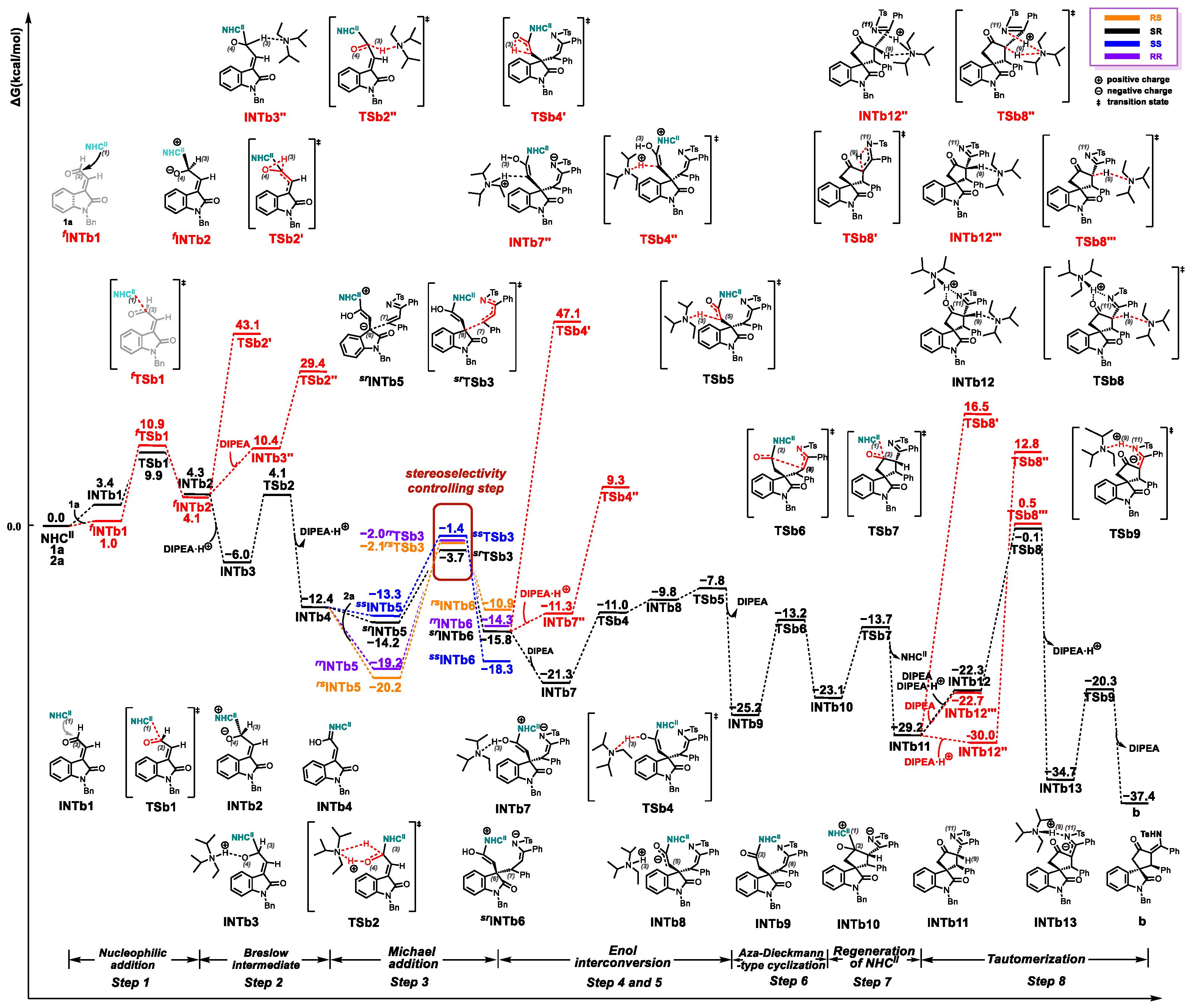

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Reaction Mechanism

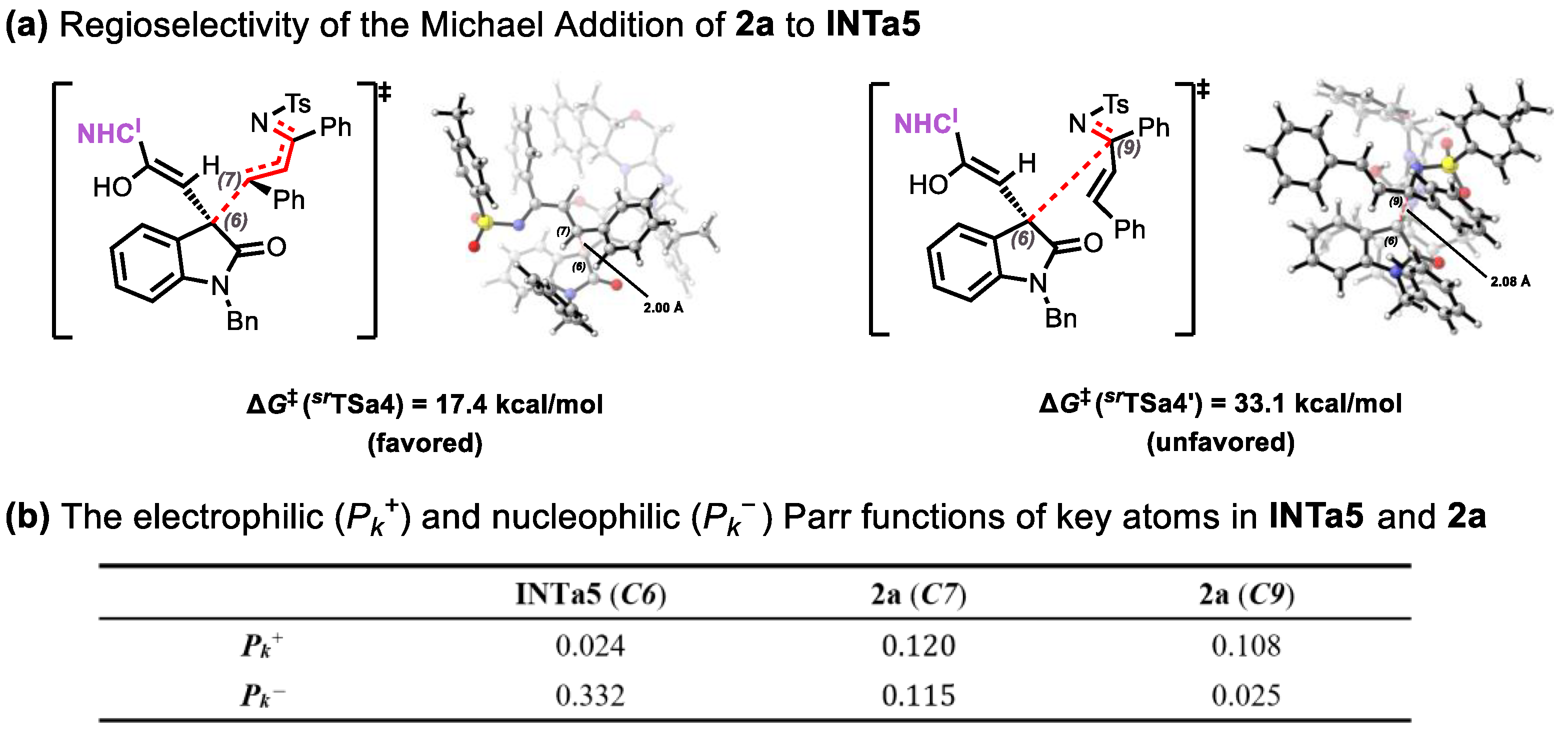

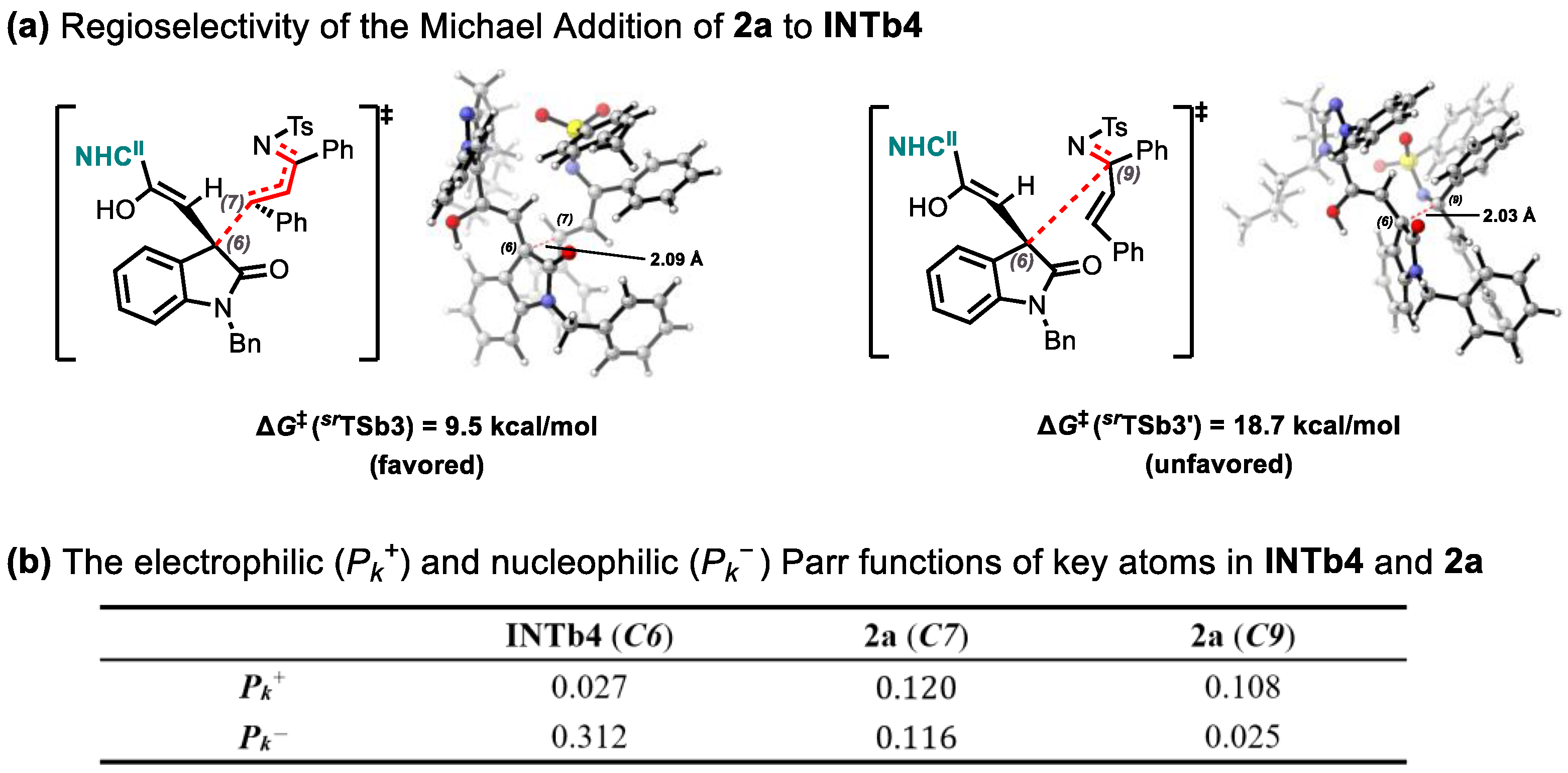

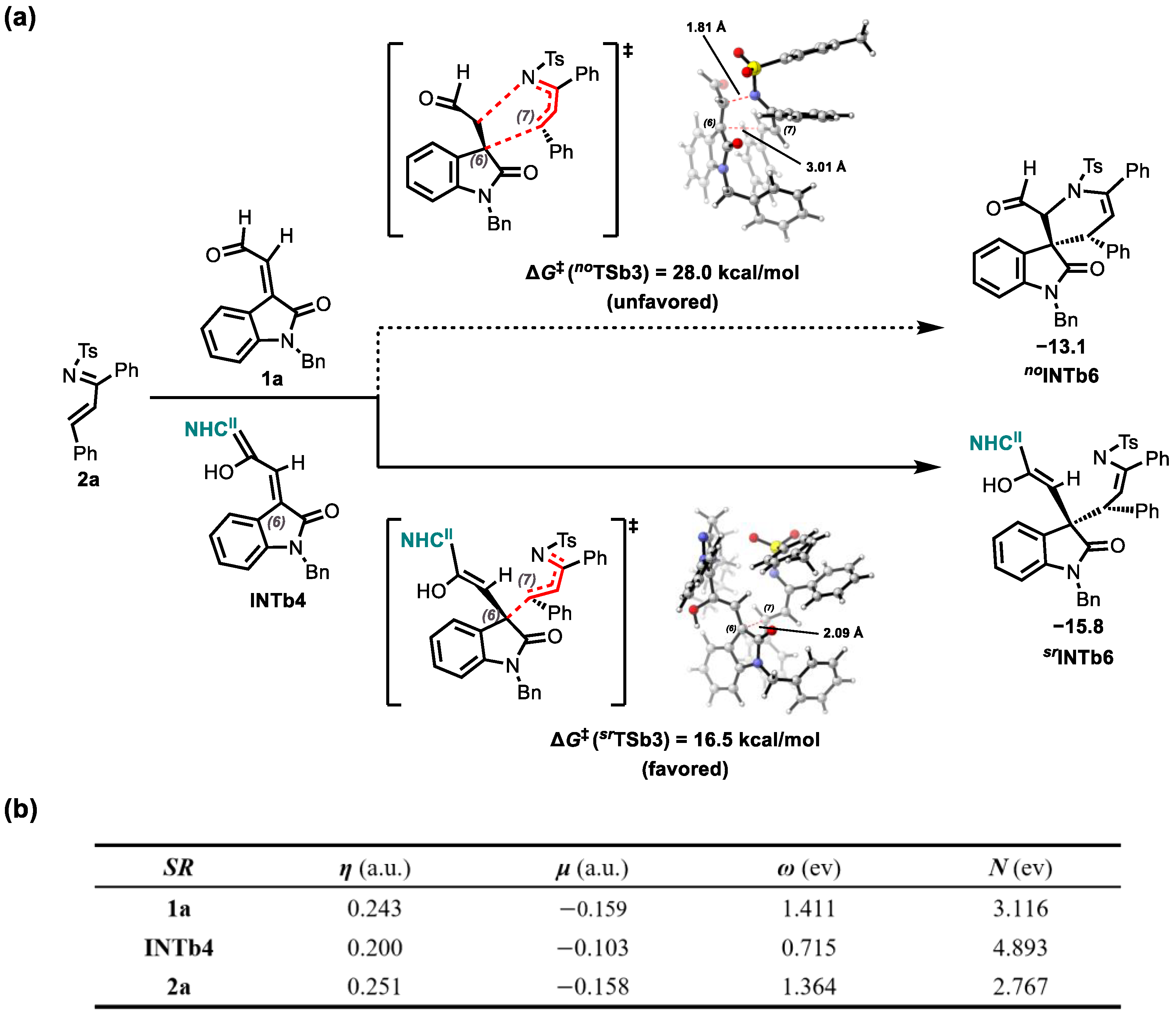

2.2. Origins of Regioselectivity

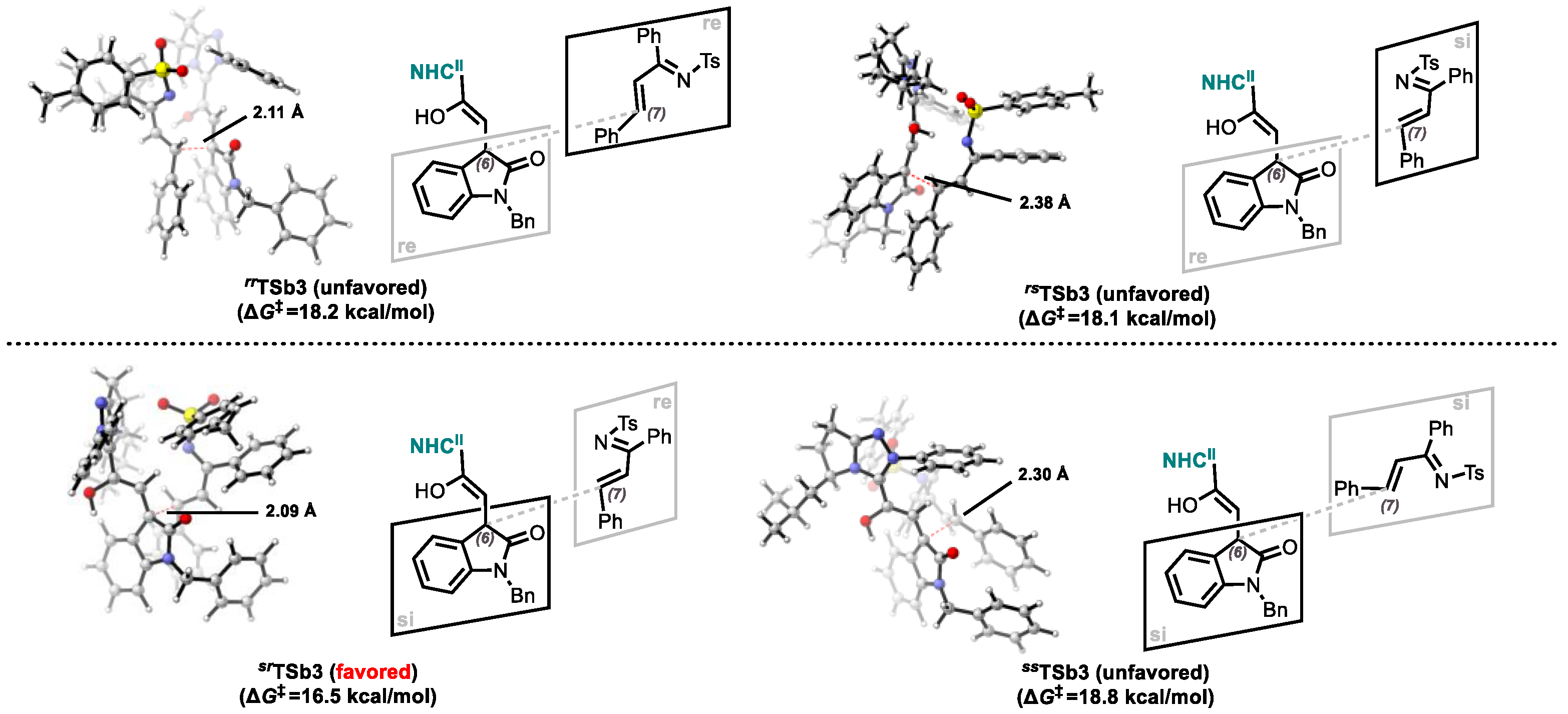

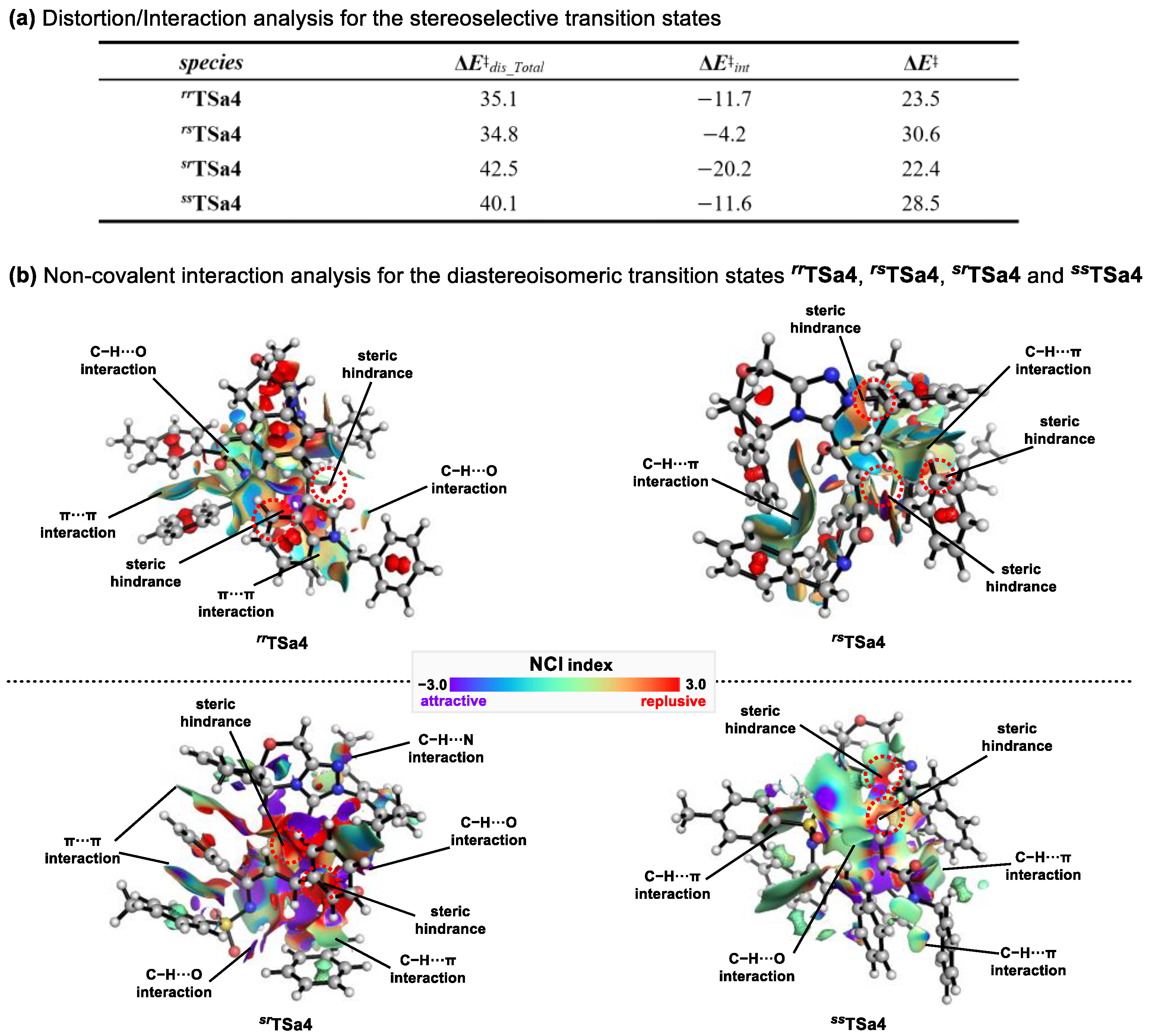

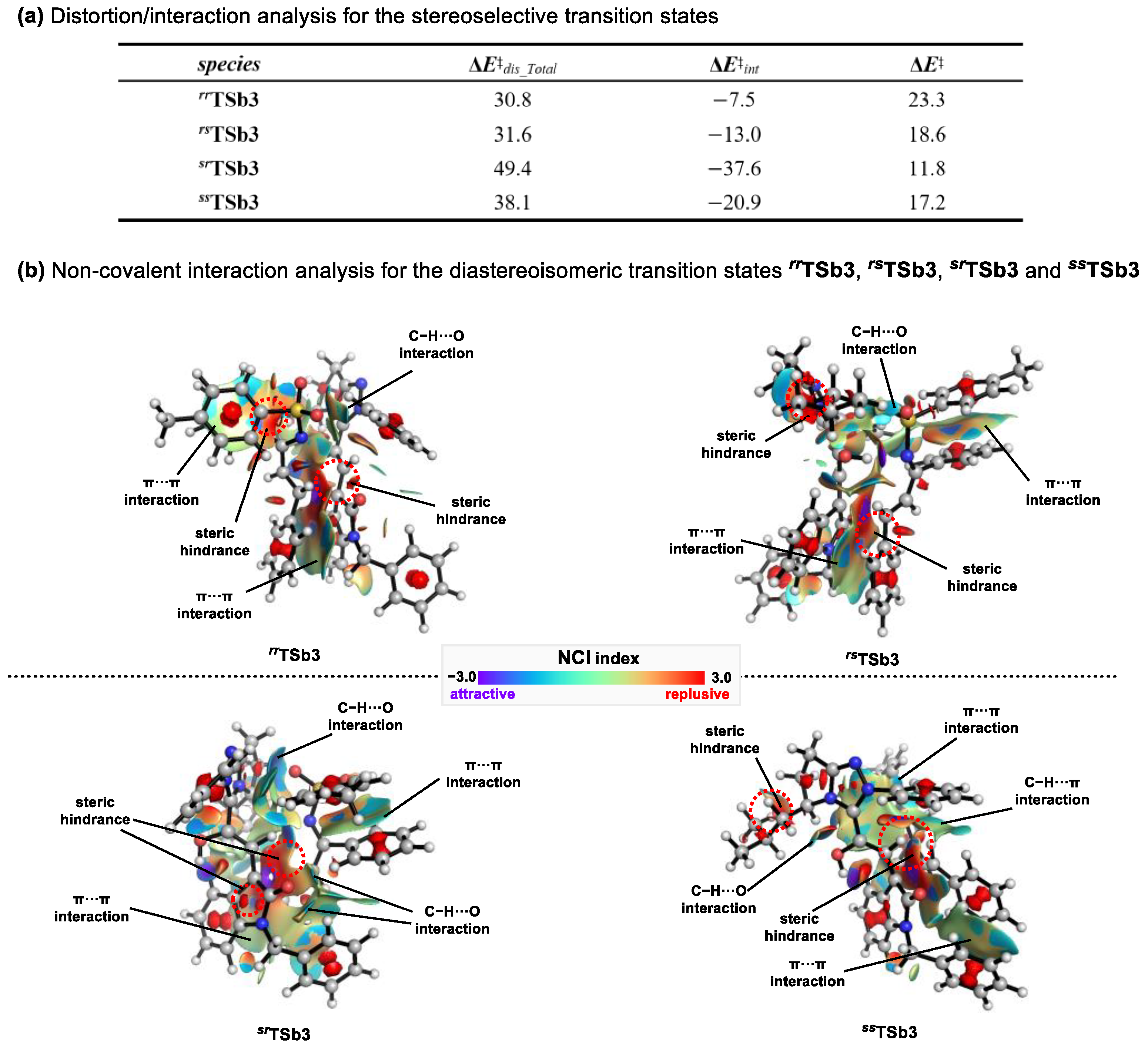

2.3. Origins of Stereoselectivity

2.4. The Role of Catalysts

3. Computational Methods

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chaudhari, P.D.; Hong, B.C.; Wen, C.L.; Lee, G.H. Asymmetric Synthesis of Spirocyclopentane Oxindoles Containing Four Consecutive Stereocenters and Quaternary α-Nitro Esters via Organocatalytic Enantioselective Michael–Michael Cascade Reactions. ACS Omega 2019, 4, 655–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, W.; Han, C.; Mohammed, S.; Li, S.S.; Song, Y.X.; Sun, F.X.; Du, Y.F. Indole-containing pharmaceuticals: Targets, pharmacological activities, and SAR studies. RSC Med. Chem. 2024, 15, 788–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Q.L.; Mao, T.; Luo, Y.; Zhang, T.X.; Wang, F.; Dong, S.X.; Feng, X.M. Enantioselective Synthesis of Spiro [cyclopentane-1,3’-oxindole] Scaffolds with Five Consecutive Stereocenters. Org. Lett. 2024, 26, 6402–6406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boddy, A.J.; Bull, J.A. Stereoselective synthesis and applications of spirocyclic oxindoles. Org. Chem. Front. 2021, 8, 1026–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.Q.; Li, N.K.; Yin, S.J.; Sun, B.B.; Fan, W.T.; Wang, X.W. Chiral N-Heterocyclic Carbene-Catalyzed Asymmetric Michael-Intramolecular Aldol-Lactonization Cascade for Enantioselective Construction of β-Propiolactone-Fused Spiro [cyclopentane-oxindoles]. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2017, 359, 1541–1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dočekal, V.; Vopálenská, A.; Měrka, P.; Konečná, K.; Jand’ourek, O.; Pour, M.; Císařová, I.; Veselý, J. Enantioselective Construction of Spirooxindole-Fused Cyclopentanes. J. Org. Chem. 2021, 86, 12623–12643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, J.; Ding, S.H.; Li, X.N.; Zhao, Q.S. Unified strategy enables the collective syntheses of structurally diverse indole alkaloids. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2024, 146, 7616–7627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, S.; Chafeev, M.; Liu, S.F.; Sun, J.Y.; Raina, V.; Chui, R.; Young, W.; Kwan, R.; Fu, J.M.; Cadieux, J.A. Discovery of XEN907, a spirooxindole blocker of NaV1.7 for the treatment of pain. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2011, 21, 3676–3681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chowdhury, S.; Liu, S.F.; Cadieux, J.A.; Hsieh, T.; Chafeev, M.; Sun, S.Y.; Jia, Q.; Sun, J.Y.; Wood, M.; Langille, J.; et al. Tetracyclic spirooxindole blockers of hNa V 1.7: Activity in vitro and in CFA-induced inflammatory pain model. Med. Chem. Res. 2013, 22, 1825–1836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, J.; Peng, R.K.; Guo, C.L.; Zhang, M.; Yang, J.; Yan, X.; Zhou, Q.; Li, H.W.; Wang, N.; Zhu, J.W.; et al. Construction of a synthetic methodology-based library and its application in identifying a GIT/PIX protein–protein interaction inhibitor. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 7176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakhuja, R.; Panda, S.S.; Khanna, L.; Khurana, S.; Jain, S.C. Design and synthesis of spiro [indole-thiazolidine] spiro [indole-pyrans] as antimicrobial agents. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2011, 21, 5465–5469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhaskar, G.; Arun, Y.; Balachandran, C.; Saikumar, C.; Perumal, P.T. Synthesis of novel spirooxindole derivatives by one pot multicomponent reaction and their antimicrobial activity. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2012, 51, 79–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, K.; Tiwari, B.; Chi, Y.R. Access to spirocyclic oxindoles via N-heterocyclic carbene-catalyzed reactions of enals and oxindole-derived α,β-unsaturated imines. Org. Lett. 2012, 14, 2382–2385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, J.M.; Lv, Y.; Tang, W.L.; Teng, K.P.; Huang, Y.X.; Ding, J.X.; Li, T.T.; Wang, G.J.; Chi, Y.R. Enantioselective Transformation of Hydrazones via Remote NHC Catalysis: Activation Across C=N and N–N Bonds. ACS Catal. 2024, 14, 18378–18384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, H.; Tiwari, B.; Mo, J.M.; Xing, C.; Chi, Y.R. Highly Enantioselective Addition of Enals to Isatin-Derived Ketimines Catalyzed by N-Heterocyclic Carbenes: Synthesis of Spirocyclic γ-Lactams. Org. Lett. 2012, 14, 5412–5415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.F.; Mou, C.L.; Zhu, T.S.; Song, B.A.; Chi, Y.R. N-Heterocyclic Carbene-Catalyzed Chemoselective Cross-Aza-Benzoin Reaction of Enals with Isatin-Derived Ketimines: Access to Chiral Quaternary Aminooxindoles. Org. Lett. 2014, 16, 3272–3275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bera, S.; Daniliuc, C.G.; Studer, A. Oxidative N-heterocyclic carbene catalyzed dearomatization of indoles to spirocyclic indolenines with a quaternary carbon stereocenter. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 7402–7406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, C.S.; Xiao, Z.X.; Liu, R.; Li, T.J.; Jiao, W.H.; Yu, C.X. N-Heterocyclic-Carbene-Catalyzed Reaction of α-Bromo-α,β-Unsaturated Aldehyde or α,β-Dibromoaldehyde with Isatins: An Efficient Synthesis of Spirocyclic Oxindole-Dihydropyranones. Chem. Eur. J. 2013, 19, 456–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Yu, C.X.; Xiao, Z.X.; Li, T.J.; Wang, X.S.; Xie, Y.W.; Yao, C.S. NHC-catalyzed oxidative γ-addition of α,β-unsaturated aldehydes to isatins: A high-efficiency synthesis of spirocyclic oxindole-dihydropyranones. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2014, 12, 1885–1891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Yu, C.X.; Li, T.J.; Wang, Y.H.; Lu, Y.N.; Wang, W.J.; Yao, C.S. N-Heterocyclic carbene-catalyzed [4+2] cyclization of α,β-unsaturated carboxylic acids bearing γ-H with isatins: An enantioselective synthesis of spirocyclic oxindole–dihydropyranones. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2016, 14, 1485–1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, B.H.; Duan, X.Y.; Li, J.H.; Wu, Y.T.; Li, Y.T.; Qi, J. N-heterocyclic carbene-catalyzed [3+2] annulation of 3,3′-bisoxindoles with α-bromoenals: Enantioselective construction of contiguous quaternary stereocenters. Org. Lett. 2022, 24, 5929–5934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breuers, C.B.J.; Daniliuc, C.G.; Studer, A. Dearomatizing Cyclization of 2-Iodoindoles by Oxidative NHC Catalysis to Access Spirocyclic Indolenines and Oxindoles Bearing an All Carbon Quaternary Stereocenter. Org. Lett. 2022, 24, 4960–4964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, Z.; Li, J.B.; Liu, C.L.; Zhu, Y.W.; Du, D. N-heterocyclic carbene-catalyzed enantioselective synthesis of spirocyclic ketones bearing gem-difluoromethylenes. Org. Chem. Front. 2023, 10, 3027–3032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maji, U.; Das, S.; Baidya, A.; Roy, I.; Guin, J. Asymmetric Synthesis of Benzofuranones with a C3 Quaternary Center via an Addition/Cyclization Cascade Using Noncovalent N-Heterocyclic Carbene Catalysis. Org. Lett. 2024, 26, 8719–8724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.H.; Wang, W.; Luo, G.Y.; Song, C.Y.; Bao, Z.W.; Li, P.; Hao, G.F.; Chi, Y.G.R.; Jin, Z.C. Carbene-Catalyzed Activation of C−Si Bonds for Chemo- and Enantioselective Cross Brook–Benzoin Reaction. Angew. Chem. 2022, 134, e202206961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reimler, J.; Yu, X.Y.; Spreckelmeyer, N.; Daniliuc, C.G.; Studer, A. Regiodivergent C-H Acylation of Arenes by Switching from Ionic-to Radical-Type Chemistry Using NHC Catalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2023, 62, e202303222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, S.J.; Candish, L.; Lupton, D.W. N-heterocyclic carbene-catalyzed generation of α,β-unsaturated acyl imidazoliums: Synthesis of dihydropyranones by their reaction with enolates. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 14176–14177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kravina, A.G.; Mahatthananchai, J.; Bode, J.W. Enantioselective NHC-Catalyzed Annulations of Trisubstituted Enals and Cyclic N-Sulfonylimines via α,β-Unsaturated Acyl Azoliums. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 9433–9436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yetra, S.R.; Kaicharla, T.; Kunte, S.S.; Gonnade, R.G.; Biju, A.T. Asymmetric N-heterocyclic carbene (NHC)-catalyzed annulation of modified enals with enolizable aldehydes. Org. Lett. 2013, 15, 5202–5205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.H.; Chen, X.Y.; Zhang, H.M.; Ye, S. N-Heterocyclic carbene-catalyzed [3+3] cyclocondensation of bromoenals with aldimines: Highly enantioselective synthesis of dihydropyridinones. Chem. Commun. 2015, 51, 12040–12043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, L.; Chen, K.Q.; Liang, Z.Q.; Sun, D.Q.; Ye, S. N-Heterocyclic carbene-catalyzed [3+3] annulation of indoline-2-thiones with bromoenals: Synthesis of indolo [2,3-b] dihydrothiopyranones. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2017, 359, 44–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.G.; Blaszczyk, S.A.; Wang, J.M. Asymmetric reactions of N-heterocyclic carbene (NHC)-based chiral acyl azoliums and azolium enolates. Green. Synth. Catal. 2021, 2, 198–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, M.; Struble, J.R.; Bode, J.W. Highly enantioselective azadiene Diels-Alder reactions catalyzed by chiral N-heterocyclic carbenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 8418–8420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Lv, H.; Zhang, Y.R.; Ye, S. Formal cycloaddition of disubstituted ketenes with 2-oxoaldehydes catalyzed by chiral N-heterocyclic carbenes. J. Org. Chem. 2008, 73, 8101–8103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.N.; Shao, P.L.; Lv, H.; Ye, S. Enantioselective Synthesis of β-Trifluoromethyl-β-lactones via NHC-Catalyzed Ketene-Ketone Cycloaddition Reactions. Org. Lett. 2009, 11, 4029–4031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.N.; Zhang, Y.Y.; Ye, S. Enantioselective Synthesis of Spirocyclic Oxindole-β-lactones via N-Heterocyclic Carbene-Catalyzed Cycloaddition of Ketenes and Isatins. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2010, 352, 1892–1895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.N.; Shen, L.T.; Ye, S. NHC-catalyzed enantioselective [2+2] and [2+2+2] cycloadditions of ketenes with isothiocyanates. Org. Lett. 2011, 13, 6382–6385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Ni, Q.J.; Blümel, M.; Shu, T.; Raabe, G.; Enders, D. NHC-Catalyzed Asymmetric Synthesis of Functionalized Succinimides from Enals and α-Ketoamides. Chem. Eur. J. 2015, 21, 8033–8037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burstein, C.; Glorius, F. Organocatalyzed conjugate umpolung of α,β-unsaturated aldehydes for the synthesis of γ-butyrolactones. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2004, 43, 6205–6208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuoka, Y.; Ishida, Y.; Sasaki, D.; Saigo, K. Cyclophane-type imidazolium salts with planar chirality as a new class of N-heterocyclic carbene precursors. Chem. Eur. J. 2008, 14, 9215–9222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, X.Q.; Zheng, C.; You, S.L. Highly enantioselective intramolecular Michael reactions by D-camphor-derived triazolium salts. Chem. Commun. 2009, 39, 5823–5825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, D.T.; Eichman, C.C.; Phillips, E.M.; Zarefsky, E.R.; Scheidt, K.A. Catalytic dynamic kinetic resolutions with N-heterocyclic carbenes: Asymmetric synthesis of highly substituted β-lactones. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 7309–7313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Schedler, M.; Daniliuc, C.G.; Glorius, F. N-Heterocyclic Carbene Catalyzed Formal [3+2] Annulation Reaction of Enals: An Efficient Enantioselective Access to Spiro-Heterocycles. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 10232–10236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Sahoo, B.; Daniliuc, C.G.; Glorius, F. N-heterocyclic carbene catalyzed switchable reactions of enals with azoalkenes: Formal [4+3] and [4+1] annulations for the synthesis of 1,2-diazepines and pyrazoles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 17402–17405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.Y.; Xong, J.W.; Liu, Q.; Li, S.; Sheng, H.; von Essen, C.; Rissanen, K.; Enders, D. Control of N-Heterocyclic Carbene Catalyzed Reactions of Enals: Asymmetric Synthesis of Oxindole-γ-Amino Acid Derivatives. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 300–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, L.X.; Zhou, C.Y.; Wang, C.M. Construction of highly congested quaternary carbon centers by NHC catalysis through dearomatization. Green. Synth. Catal. 2023, 4, 263–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.H.; Han, P.L.; Zhang, X.S.; Qiao, Y.; Xu, Z.H.; Zhang, Y.G.; Li, D.P.; Wei, D.H.; Lan, Y. NHC-Catalyzed transformation reactions of imines: Electrophilic versus nucleophilic attack. J. Org. Chem. 2022, 87, 7989–7994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nong, Y.L.; Pang, C.; Teng, K.P.; Zhang, S.; Liu, Q. NHC-Catalyzed Chemoselective Reactions of Enals and Cyclopropylcarbaldehydes for Access to Chiral Dihydropyranone Derivatives. J. Org. Chem. 2023, 88, 13535–13543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, X.X.; Wei, D.H. Mechanism and origin of stereoselectivity for the NHC-catalyzed desymmetrization reaction for the synthesis of axially chiral biaryl aldehydes. J. Org. Chem. 2024, 89, 3133–3142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.M.; Long, X.W.; Zhang, J.W.; Qu, C.L.; Wang, P.; Yang, X.D.; Puno, P.T.; Deng, J. Asymmetric total synthesis of penicilfuranone A through an NHC-catalyzed umpolung strategy. Chem. Sci. 2025, 16, 8302–8308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Li, S.; Blümel, M.; Puttreddy, R.; Peuronen, A.; Rissanen, K.; Enders, D. Switchable Access to Different Spirocyclopentane Oxindoles by N-Heterocyclic Carbene Catalyzed Reactions of Isatin-Derived Enals and N-Sulfonyl Ketimines. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017, 129, 8636–8641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.Y.; Wei, D.H.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, W.J.; Tang, M.S. N-heterocyclic carbene (NHC)-catalyzed sp3 β-C-H activation of saturated carbonyl compounds: Mechanism, role of NHC, and origin of stereoselectivity. ACS Catal. 2016, 6, 279–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, N.; Zhu, Y.Y.; Zhu, Z.H.; Yang, Y.K.; Zhang, W.J.; Wei, D.H.; Qu, L.B.; Tang, M.S.; Chen, H.S. A density functional theory study on mechanisms of [4+2] annulation of enal with α-methylene cycloalkanone catalyzed by N-heterocyclic carbene. Int. J. Quantum Chem. 2019, 119, e26039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, S.S.; Yuan, H.Y.; Zhang, J.P. A mechanistic investigation into N-heterocyclic carbene (NHC) catalyzed umpolung of ketones and benzonitriles: Is the cyano group better than the classical carbonyl group for the addition of NHC? Org. Chem. Front. 2019, 6, 523–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domingo, L.R.; Pérez, P.; Sáez, J.A. Understanding the local reactivity in polar organic reactions through electrophilic and nucleophilic Parr functions. RSC Adv. 2013, 3, 1486–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bickelhaupt, F.M.; Houk, K.N. Analyzing Reaction Rates with the Distortion/Interaction-Activation Strain Model. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 10070–10086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parr, R.G.; Pearson, R.G. Absolute hardness: Companion parameter to absolute electronegativity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1983, 105, 7512–7516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yepes, D.; Murray, J.S.; Pérez, P.; Domingo, L.R.; Politzer, P.; Jaque, P. Complementarity of reaction force and electron localization function analyses of asynchronicity in bond formation in Diels-Alder reactions. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2014, 16, 6726–6734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sham, L.J.; Kohn, W. One-particle properties of an inhomogeneous interacting electron gas. Phys. Rev. 1966, 145, 561–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domingo, L.R.; Picher, M.T.; Sáez, J.A. Toward an understanding of the unexpected regioselective hetero-diels-alder reactions of asymmetric tetrazines with electron-rich ethylenes: A DFT study. J. Org. Chem. 2009, 74, 2726–2735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domingo, L.R.; Saézm, J.A.; Zaragozá, R.J.; Arnó, M. Understanding the participation of quadricyclane as nucleophile in polar [2σ+2σ+2π] cycloadditions toward electrophilic π molecules. J. Org. Chem. 2008, 73, 8791–8799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frisch, M.J.; Trucks, G.W.; Schlegel, H.B.; Scuseria, G.E.; Robb, M.A.; Cheeseman, J.R.; Scalmani, G.; Barone, V.; Mennucci, B.; Petersson, G.A.; et al. Gaussian 09, Revision E.01; Gaussian, Inc.: Wallingford, CT, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y.; Truhlar, D.G. The M06 suite of density functionals for main group thermochemistry, thermochemical kinetics, noncovalent interactions, excited states, and transition elements: Two new functionals and systematic testing of four M06-class functionals and 12 other functionals. Theor. Chem. Acc. 2008, 120, 215–241. [Google Scholar]

- Schröder, H.; Hühnert, J.; Schwabe, T. Evaluation of DFT-D3 dispersion corrections for various structural benchmark sets. J. Chem. Phys. 2017, 146, 044115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hariharan, P.C.; Pople, J.A. The influence of polarization functions on molecular orbital hydrogenation energies. Theoret. Chim. Acta 1973, 28, 213–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francl, M.M.; Pietro, W.J.; Hehre, W.J.; Binkley, J.S.; Gordon, M.S.; DeFrees, D.J.; Pople, J.A. Self-consistent molecular orbital methods. XXIII. A polarization-type basis set for second-row elements. J. Chem. Phys. 1982, 77, 3654–3665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rassolov, V.A.; Pople, J.A.; Ratner, M.A.; Windus, T.L. 6-31G* basis set for atoms K through Zn. J. Chem. Phys. 1998, 109, 1223–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Truhlar, D.G. Density functionals with broad applicability in chemistry. Acc. Chem. Res. 2008, 41, 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonaccorsi, R.; Cimiraglia, R.; Tomasi, J. Ab initio evaluation of absorption and emission transitions for molecular solutes, including separate consideration of orientational and inductive solvent effects. J. Comput. Chem. 1983, 4, 567–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukui, K. The path of chemical reactions-the IRC approach. Acc. Chem. Res. 1981, 14, 363–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hratchian, H.P.; Schlegel, H.B. Accurate reaction paths using a Hessian based predictor–corrector integrator. J. Chem. Phys. 2004, 120, 9918–9924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hratchian, H.P.; Schlegel, H.B. Using Hessian updating to increase the efficiency of a Hessian based predictor-corrector reaction path following method. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2005, 1, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reed, A.E.; Curtiss, L.A.; Weinhold, F. Intermolecular interactions from a natural bond orbital, donor-acceptor viewpoint. Chem. Rev. 1988, 88, 899–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, E.R.; Keinan, S.; Mori-Sánchez, P.; Contreras-García, J.; Cohen, A.J.; Yang, W. Revealing Noncovalent Interactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 6498–6506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Contreras-García, J.; Johnson, E.R.; Keinan, S.; Chaudret, R.; Piquemal, J.P.; Beratan, D.N.; Yang, W.T. NCIPLOT: A program for plotting noncovalent interaction regions. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2011, 7, 625–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schrödinger, LLC.; DeLano, W. The PyMOLmolecular Graphics System, version 3.0.0; Schrödinger, LLC.: New York, NY, USA, 2020.

- Legault, C.Y. CYLview20; Université de Sherbrooke: Quebec City, QC, Canada, 2020. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yu, S.; Zhou, W.; Jiang, Y.; Wang, H.; Zhou, X.; Yang, S. DFT Insights into NHC-Catalyzed Switchable [3+4] and [3+2] Annulations of Isatin-Derived Enals and N-Sulfonyl Ketimines: Mechanism, Regio- and Stereoselectivity. Molecules 2025, 30, 4218. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30214218

Yu S, Zhou W, Jiang Y, Wang H, Zhou X, Yang S. DFT Insights into NHC-Catalyzed Switchable [3+4] and [3+2] Annulations of Isatin-Derived Enals and N-Sulfonyl Ketimines: Mechanism, Regio- and Stereoselectivity. Molecules. 2025; 30(21):4218. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30214218

Chicago/Turabian StyleYu, Saisai, Wenxin Zhou, Yueming Jiang, Hangyu Wang, Xiaoyu Zhou, and Shengwen Yang. 2025. "DFT Insights into NHC-Catalyzed Switchable [3+4] and [3+2] Annulations of Isatin-Derived Enals and N-Sulfonyl Ketimines: Mechanism, Regio- and Stereoselectivity" Molecules 30, no. 21: 4218. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30214218

APA StyleYu, S., Zhou, W., Jiang, Y., Wang, H., Zhou, X., & Yang, S. (2025). DFT Insights into NHC-Catalyzed Switchable [3+4] and [3+2] Annulations of Isatin-Derived Enals and N-Sulfonyl Ketimines: Mechanism, Regio- and Stereoselectivity. Molecules, 30(21), 4218. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30214218