Adjuvant Novel Nanocarrier-Based Targeted Therapy for Lung Cancer

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Drug Delivery Constraints in Lung Cancer Management

3. Nucleic Acid Role in Lung Cancer Management

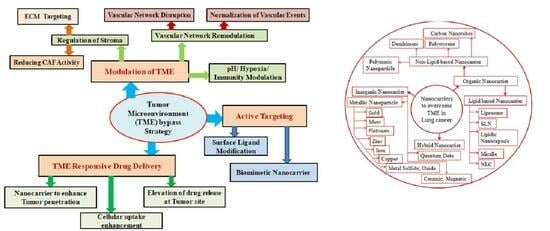

4. Strategies to Overcome the Tumor Microenvironment

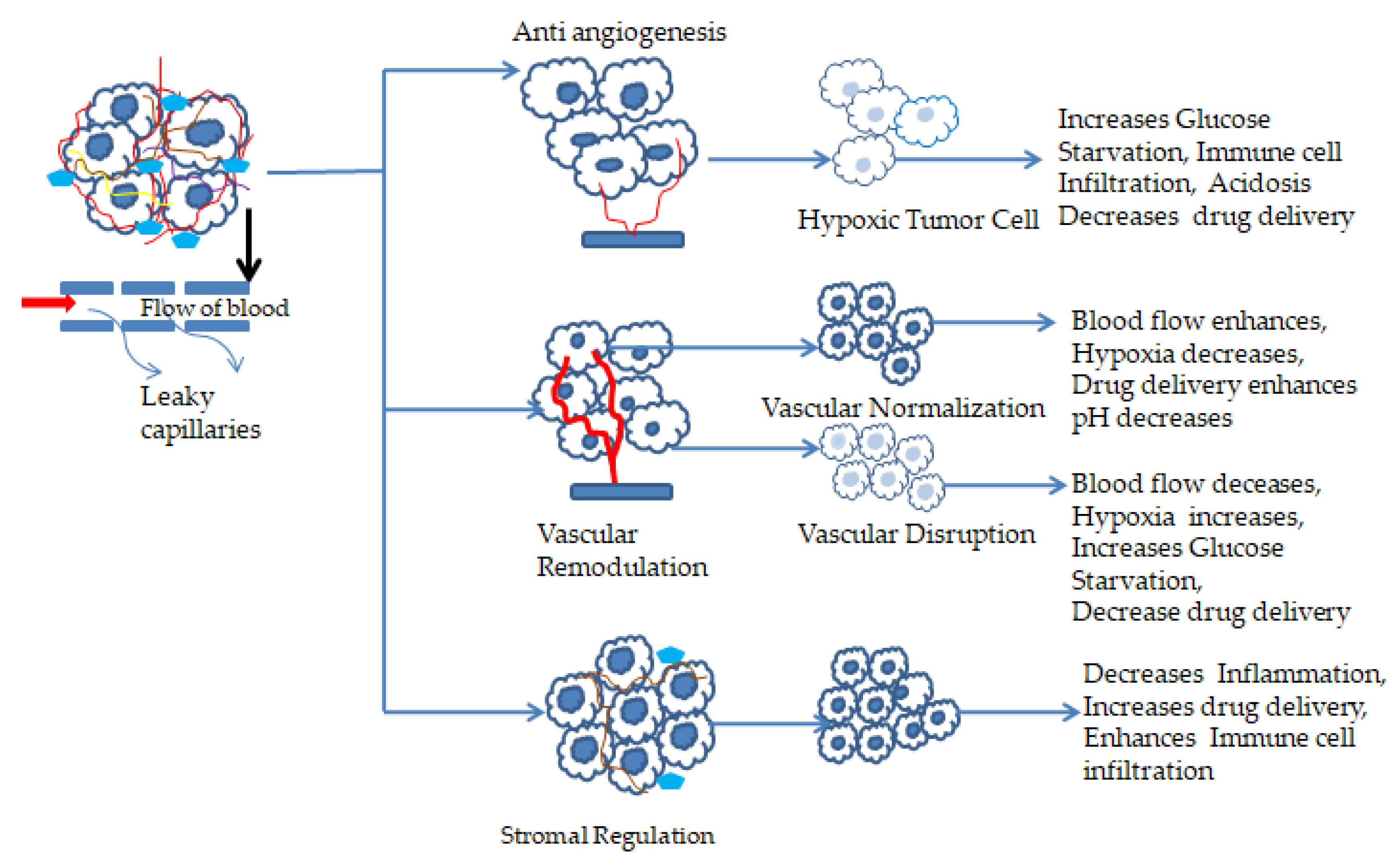

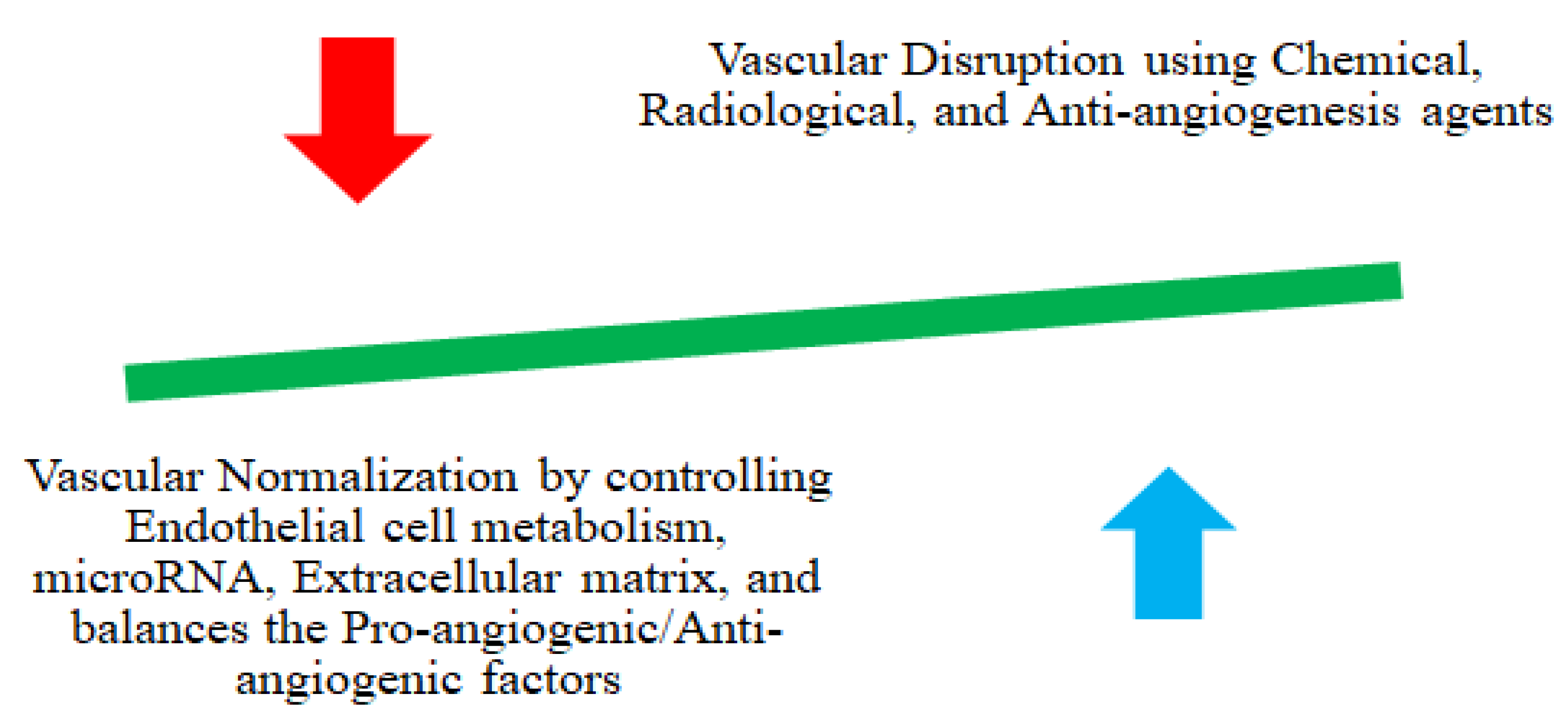

4.1. Vascular Remodulation

4.2. Stromal Regulation

4.3. Hypoxia Manipulation

4.4. pH Manipulation

4.5. Immunity Modulation

4.6. Active Targeting

4.7. Tumor Environment Responsive Drug Delivery

| Strategies | Process | Mechanism | Example | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Modulation of TME | Vascular network remodulation | Vascular network disruption and decompression | Co-administration of combretastatin A4 (CA4) NPs with doxorubicin, CA4 NPs with Imiquimod, nanocomposite hydrogel antitumor therapy, and near-infrared radiation | [112,113,114,115,116] |

| Normalizing the vascular network | Anti-VEGF-receptor-2 antibody DC101 modulates NPs andnitric oxide delivery with nanocarriers | [105,117,118] | ||

| Regulation of stroma | Extracellular matrix (ECM) targeting | [92,94] | ||

| ECM synthesis | Metelimumab (transforming growth factor-β ligand-blocking antibody) conjugate NPs can enhance loaded drug effectivity. Prolyl-4-hydroxylase inhibitors (which inhibit collagen synthesis in vascular smooth muscle cells) conjugate NPs can enhance drug effectivity | [123,124,125,126,127,128] | ||

| ECM degradation | Inhibition of hyaluronidases, collagenase enzymes, and putrescine regulates ECM degradation. Conjugating these particles into the loaded NPs can enhance the drug’s effectivity | [122,130,131] | ||

| ECM signaling | Volociximab inhibits angiogenesis by interfering with integrin α binding with fibronectin in tumor vasculature. Co-administration of volociximab with other tumor-mimicking drugs can be a more effective therapeutic target | [123,129] | ||

| ECM mimicking | Preparing artificial extracellular matrix (AECM) based on transformable laminin (LN)-mimic peptides and hydrogel-fabricated NP-loaded drugs can enhance effectivity | [92,132,133] | ||

| Reducing cancer-associated fibroblast (CAF) activity | [92] | |||

| CAFs disruption | Vimentin expression increased the migration and invasion of cancer cells. Preparing artemisinin (which inhibits vimentin expression) as a capping agent for the NPs loaded with drugs can be useful. Fibroblast activation protein is overexpressed in the stroma. N-(4-quinolinoyl)-Gly-(2-cyanopyrrolidine)-capping NPs inhibit FAPs overexpression with the active drug, which may be useful to regulate stroma | [134,135,136,137,138] | ||

| Reprogramming CAFs | CAFs act as either immune suppressive or supportive agents. Angiotensin receptor blockers (ARB) reduce latent CAF activity. ARB nanoconjugates can enhance immune-supportive activity | [139,140] | ||

| Hypoxia manipulation | Oxygen supply elevation | Using theranostic conversion nanoprobe MnO2 NPs. In the tumor cell, excessive amounts of H2O2 and lactic acid are produced. Theranostic MnO2 reacts with acidic H2O2 and produces Mn2+ and enhanced O2 production | [141,142] | |

| Decreases oxygen consumption | Encapsulating photothermal therapy with electron transport chain hindering agents through NPs | [92,140,145] | ||

| Using hypoxia-activated prodrugs (HAP) | HAPs are activated through spontaneous electron oxidoreductases. HAP agents combined with targeted therapy with checkpoint blockers increase the influx into the hypoxic zone | [143,144,145] | ||

| pH manipulation | Acidity neutralizing agents | Sodium potassium citrate increased blood HCO3- levels in oral doses and neutralized the TME pH | [146,147,148,149] | |

| Controlling pH regulatory enzymes | As in the tumor microenvironment, acidic pH affects the chemotherapeutic drug efficacy. By regulating pH, the efficacy can be enhanced. Few drugs are carbonic anhydrase IX/XII and proton pump inhibitors | [146,147] | ||

| Immunity modulation | Tyro3, Axl, and Mertk receptor (TAM) regulation | TAM overexpression increases cell survival and decreases apoptotic signaling. Again, TAM down-streaming promotes metastasis via migration and invasion. The immunosuppressive nature of the TAM arises from the polarization of macrophages M1 to M2. M2 releases immune-suppressive cytokines. M2 blocking agents and M1 reprogramming agents can regulate this immunity suppression. Using small-molecule tyrosine inhibitors and TAM receptor targeted ligands is useful to regulate it | [152,153,154,155] | |

| Regulatory T-cell (Treg) inhibition | Treg cells regulate T-cell immune responses to maintain cell homeostasis. But in the TME, Treg cells decrease the entry of T cells. Transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) inhibitors and anti-PD-L1 antibodies reduce the TGF-β signal to promote T-cell infiltration into the TME. Again, cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein-4 (CTLA-4) antibodies remove the Treg cells and can enhance T cell functions | [152,156] | ||

| Myeloid-derived suppressor cell(MDSC) inhibition | MDSC induces immune suppression by inhibiting T-cell, NK-cell, and macrophage functions. Targeting and inhibiting phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)δ, PD-L1 or CTLA-4, and multi-kinase MDSC can be controlled | [157,158] | ||

| Enhancement of active targeting | Surface ligand modification | Folate discs enhanced the permeability and photothermal efficacy | [153,166] | |

| Biomimetically modified NPs | Cancer cell membrane-coated NPs can carry antigens and drugs to the target | [164,165] | ||

| Tumor microenvironment responsive drug delivery system | Enhanced tumor penetration of carrier NPs | Functional moieties sensitive to a variety of Tumor cellular stimuli | In response to the TME, supramolecular architectures based on peptides can convert structurally and allow therapeutics for controlled release. This dissertation emphatically introduces peptide assemblies with a stimulus-responsive structural conversion to acids, high temperatures, and high oxidative potentials in tumor tissues | [153,166,167] |

| Particle size modification | After blood circulation, particles with a large size can shrink in size due to internal stimuli, such as enzymes, acidic pH, and hypoxia. Using peptides or other favorable ligands, NP entraps to form corona at TME | [170,174,175,176,177,178,179] | ||

| Enhancement of cellular uptake | Conversion of surface charges | It helps to eliminate long circulation times and cellular uptake by modifying its surface charge. An example is a pH-sensitive PEG coating | [180] | |

| Detachments of shell of the NPs | As nano-vectors accumulate at tumor sites via the EPR effect, overexpressed MMP-9 can detach the PEG corona to expose peptide RGD to facilitate cellular internalization | [92] | ||

| Elevate the drug release at cancer site | Polymer switches between hydrophilic–hydrophobic triggered by TME signals | Protonation and de-protonation polymers present in the NPs can switch from hydrophilic to hydrophobic and trigger drug release at the targeted sites. Poly(2-(diisopropylamino)ethyl methacrylate) can trigger the drug release | [181,182] | |

| Cleavage with a sensitive linker | Hypoxia-sensitive linker | [144,181] | ||

5. Novel Nanocarriers Based Treatment Approach

5.1. Organic Nanocarriers

5.1.1. Lipid Based Nanocarriers

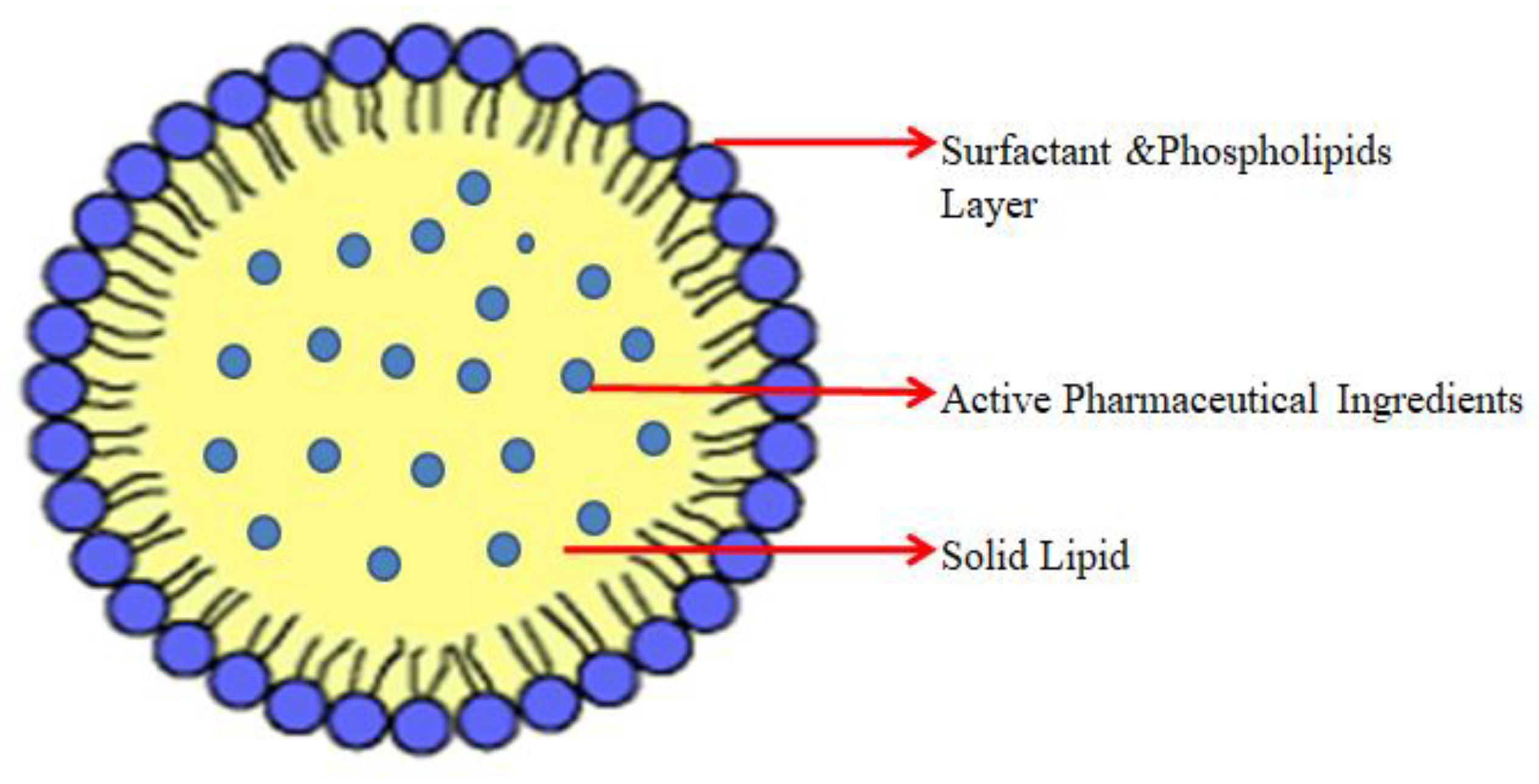

Solid Lipid Based NPs

Liposomes

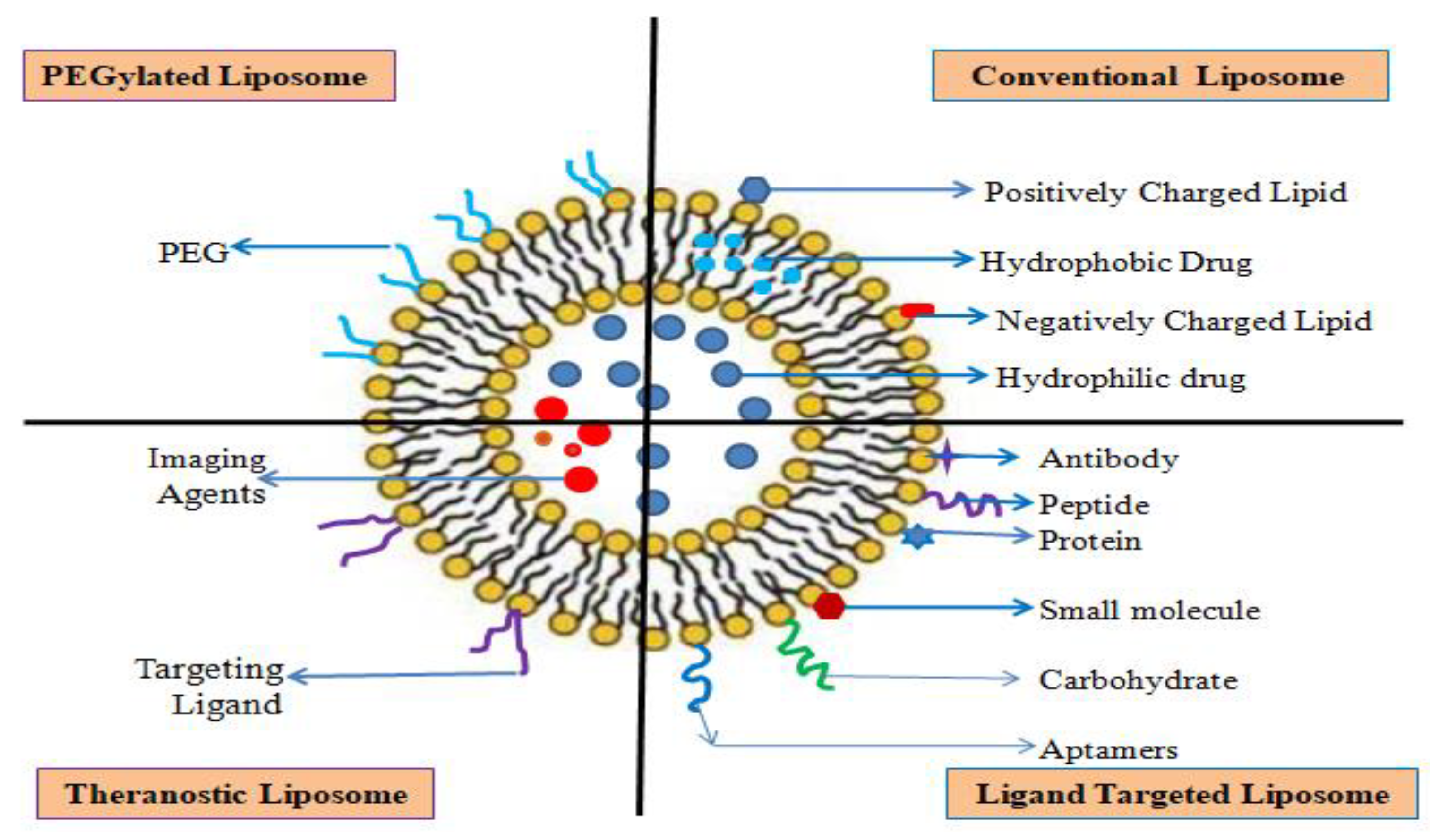

Conventional Liposome

PEGylated Liposome

Ligand Targeted Liposome

Theranostic Liposome

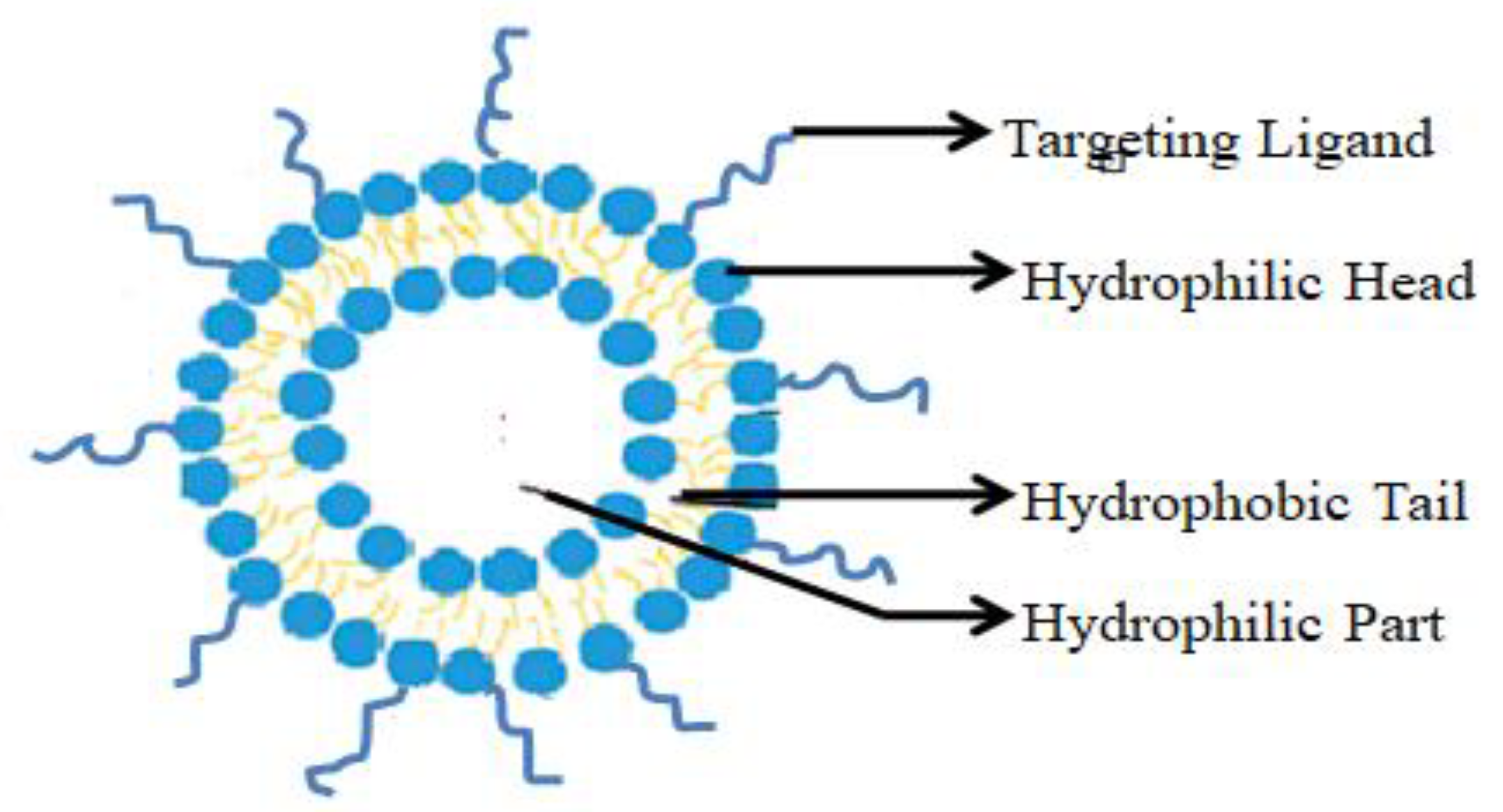

Micelles

Lipidic Nanocapsule

Nanostructured Lipid Nanocarrier

5.1.2. Non-Lipid-Based Organic Nanocarriers

Polymeric Nanocarriers

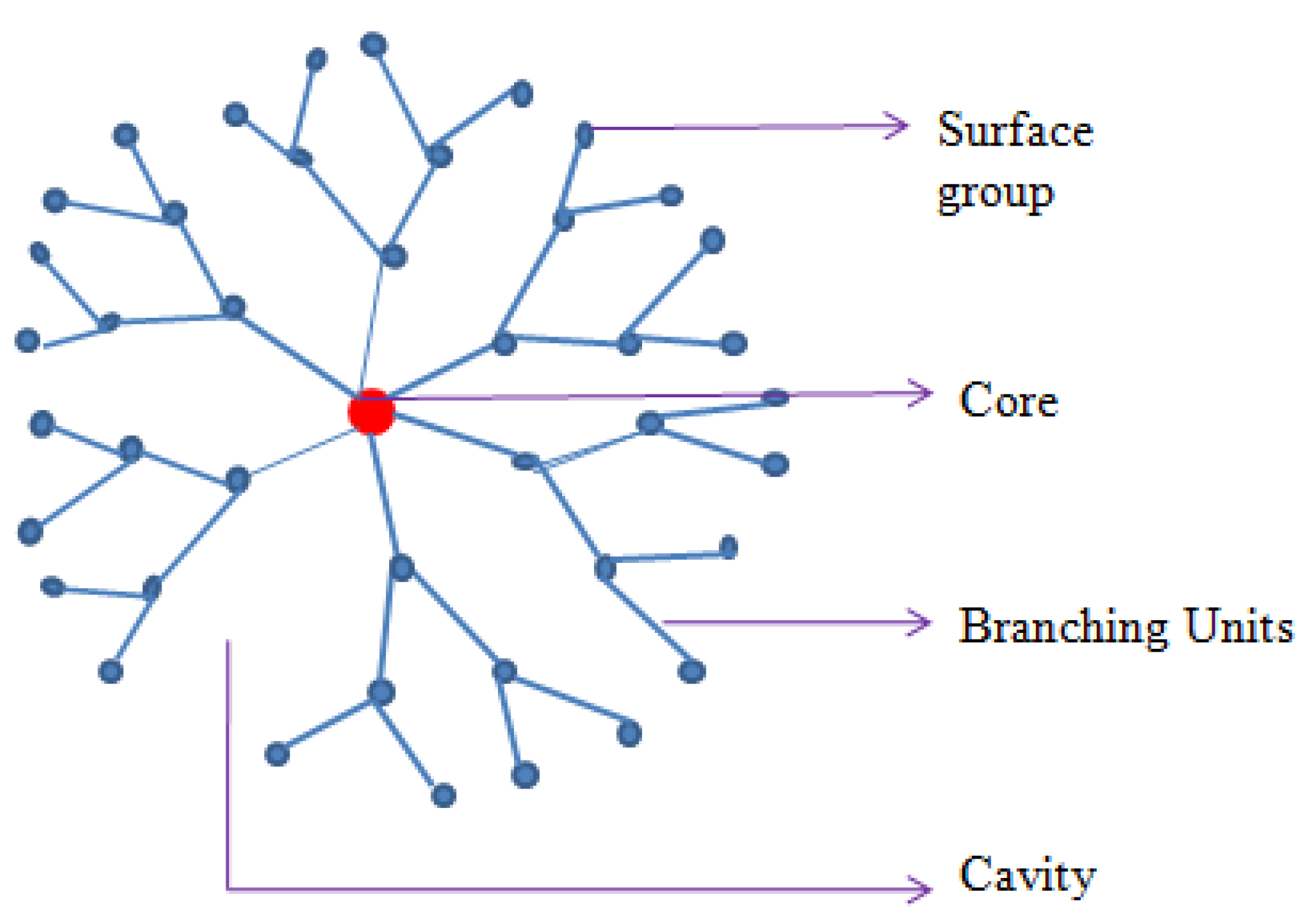

Dendrimers

Polystyrene NP Carriers

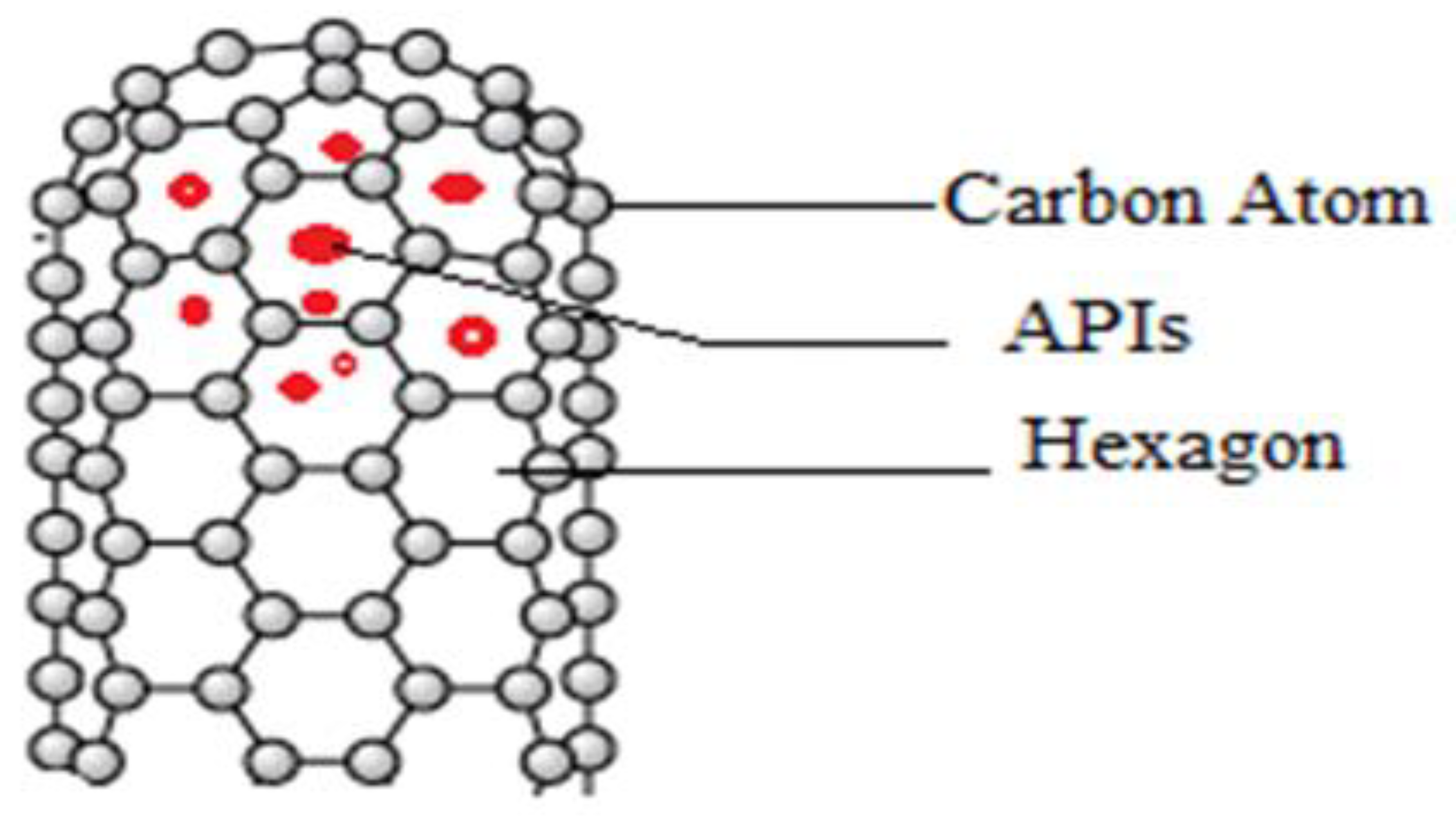

Carbon Nanotubes

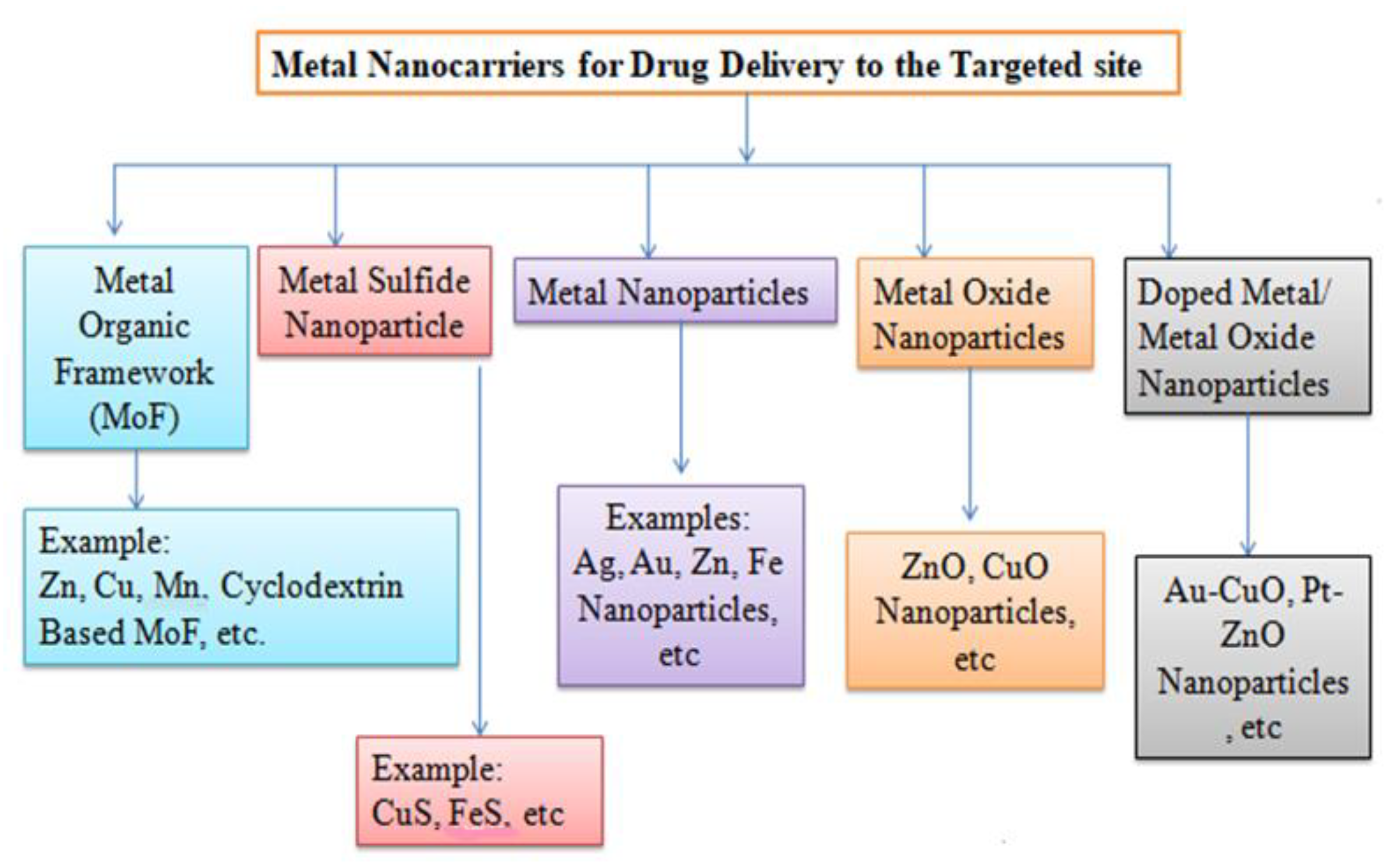

5.2. Inorganic Nanocarriers

5.2.1. Metallic NP Carrier

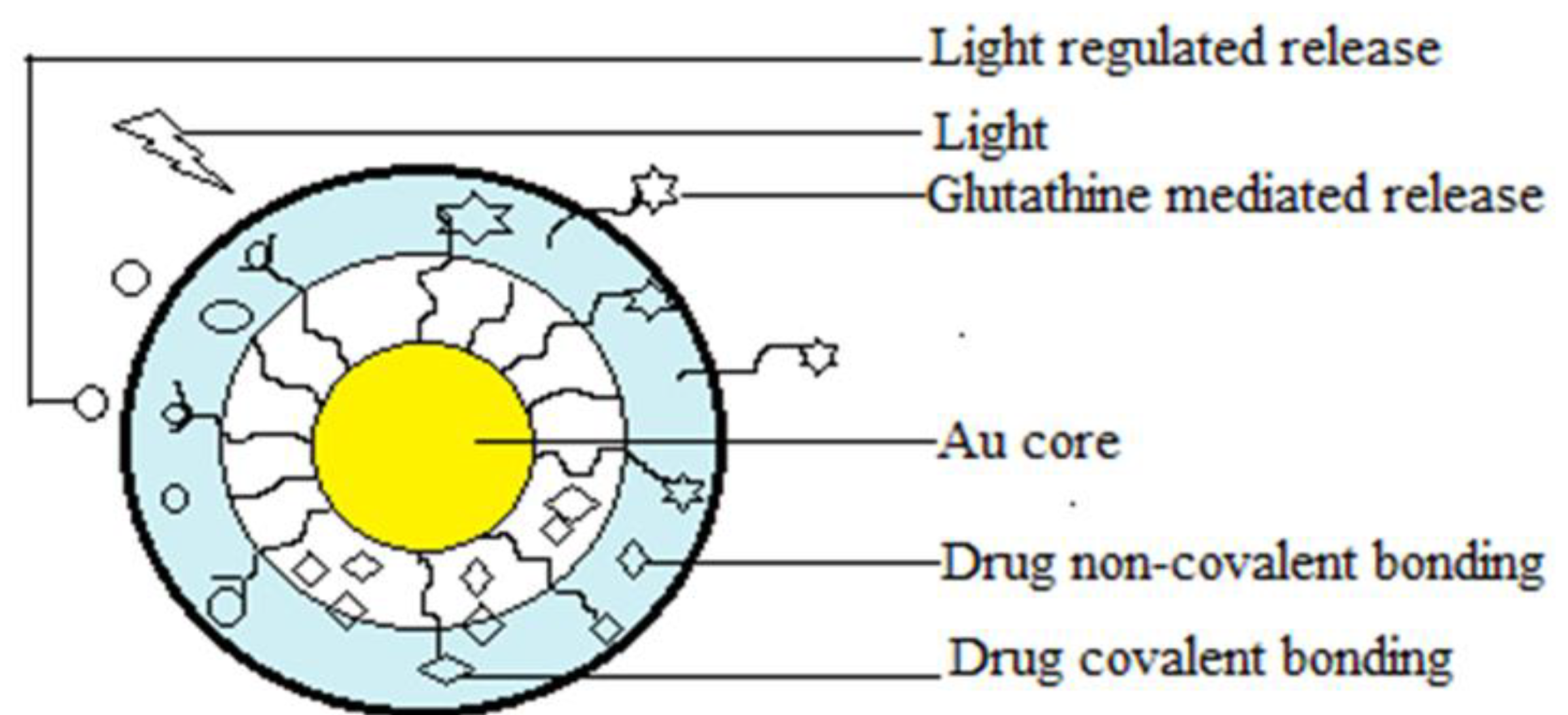

Gold NP

Silver NP

Platinum NP

5.2.2. Metal Oxide NP

Zinc Oxide NP

Iron Oxide NP

Copper Oxide NP

Titanium Dioxide NP

Magnesium Oxide NP

5.2.3. Metal Sulfide NP

5.2.4. Metal–Organic NPs

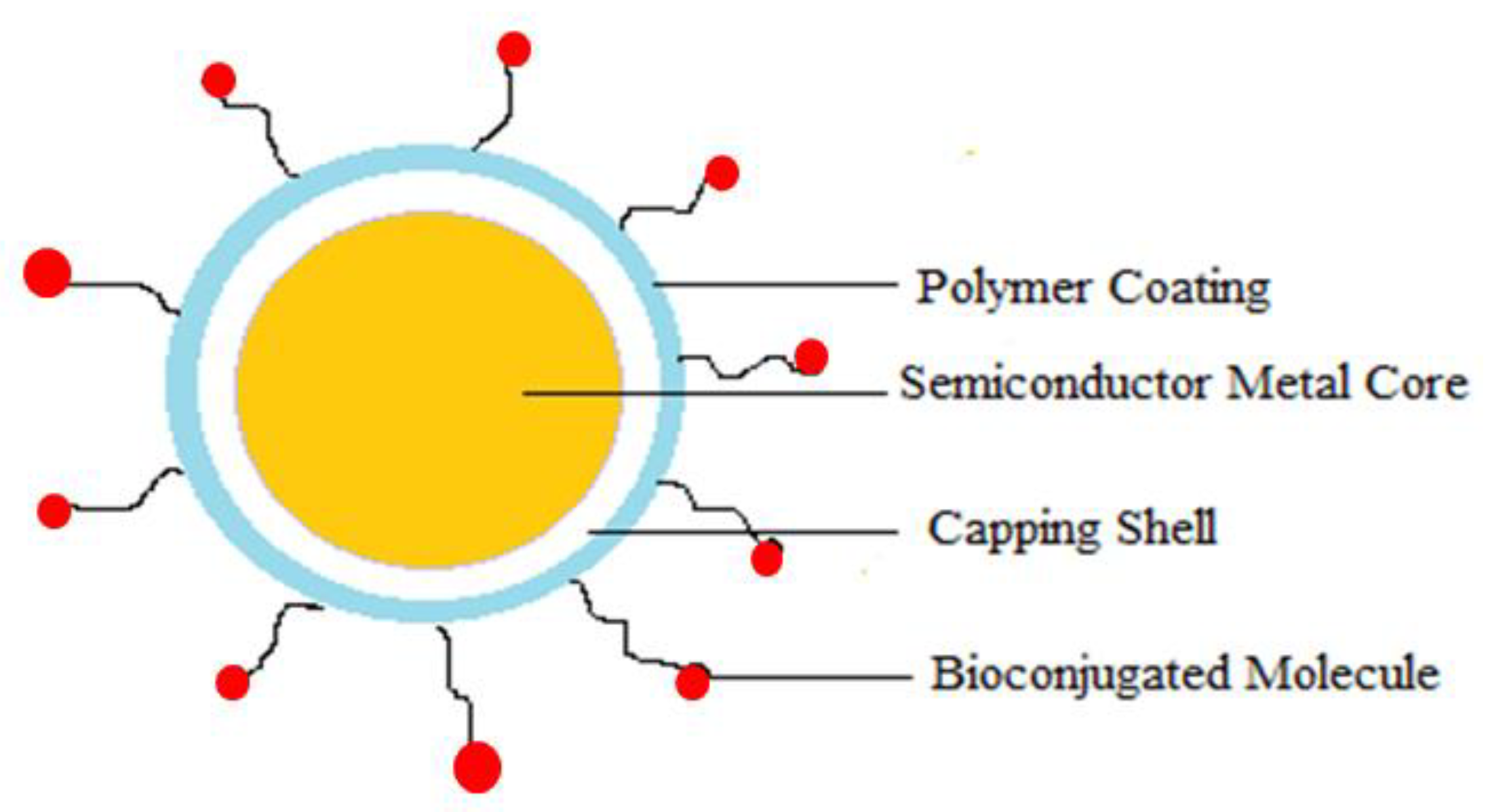

5.2.5. Quantum Dots

5.2.6. Magnetic NP

5.2.7. Ceramic NP

5.2.8. Mesoporous Silica Nanocarrier

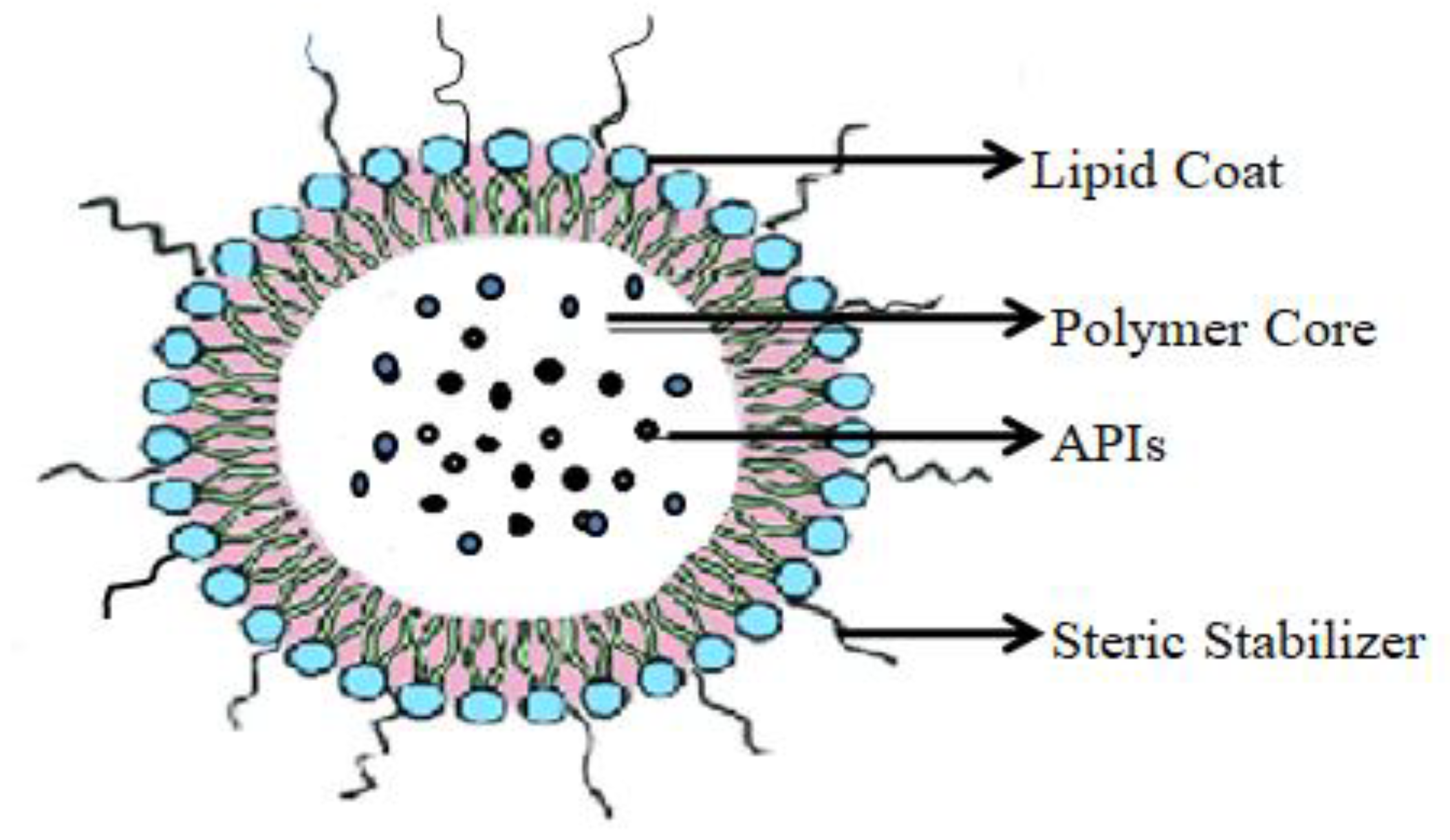

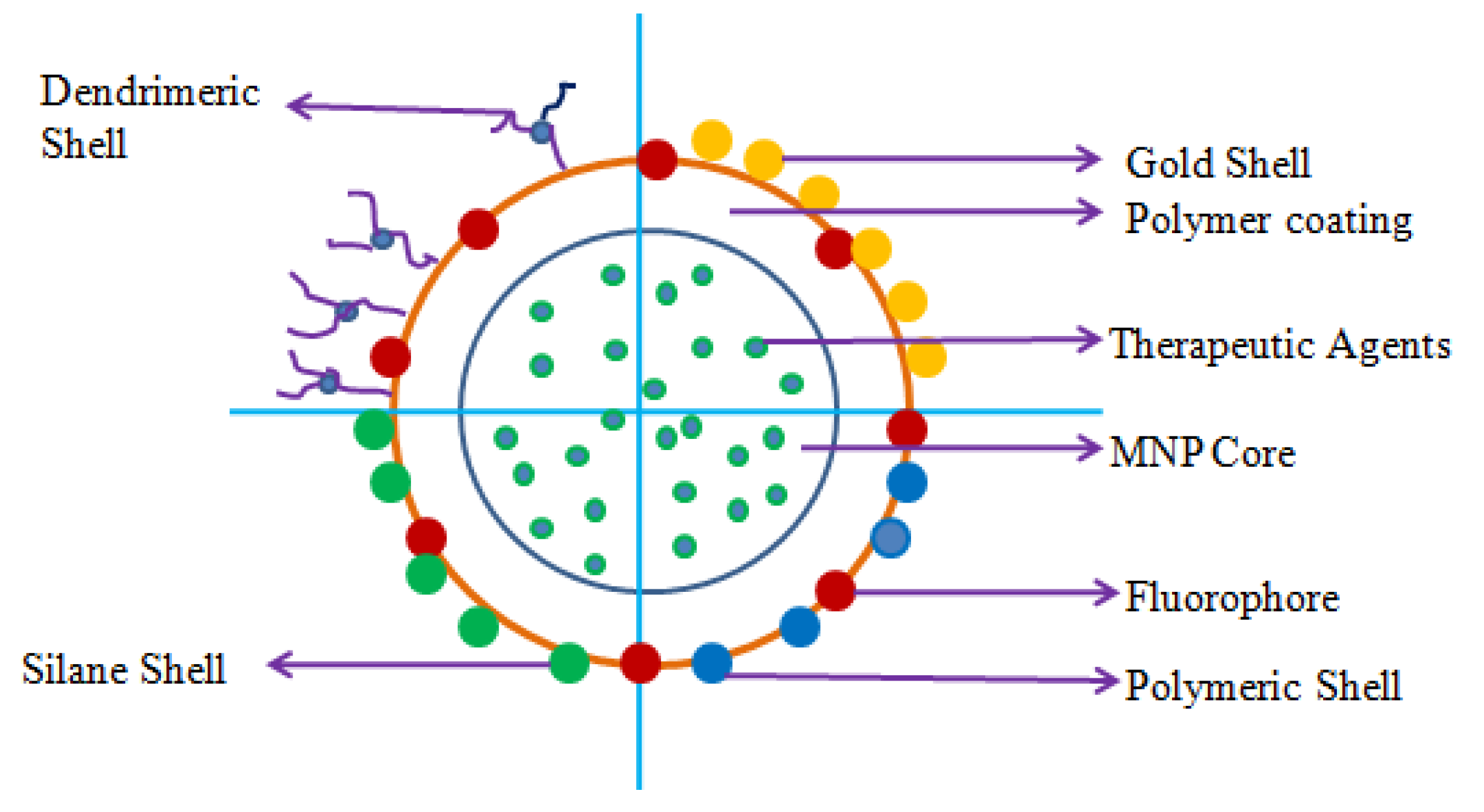

5.3. Hybrid Nanocarrier

| Drugs | Nanocarriers | Dosage Form | Key Target | Approve Status | Approved By | Remarks | Patent No | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ceranib-2 | Lipid NP | Nanoemulsion | Ceramidase inhibitors | Approved | World Patent | Enhances penetration through the cell membrane and increases bioavailability | WO2020018049A2 | [192] |

| Silymarin | Solid lipid NP | Intravenous injection | Folic acid | Pending | Chinese patent | Folic acid modified silymarin SLN enhances internalization in TME | CN111195239A | [196] |

| Anticancer drug | Liposome | Subcutaneous | Active targeting | Approved | Chinese patent | Biofunctionalization further enhances the loaded drug efficacy | CN105726483B | [206] |

| Irinotecan, veliparib | Nanoliposome | Intravenous | PARP and topoisomerase-1 inhibition | Granted | Japanese patent | Nano-liposomal formulation shows combinational synergy along with better efficacy | JP2018528184A | [207] |

| Anticancer drug | Epirubicin conjugated polymeric micelle | Intravenous and oral | Epirubicin resistant cancer | Granted | United States patent | pH-sensitive epirubicin-conjugated micelle with anticancer drug synergistically enhances the efficacy of epirubicin in resistant and metastasizing cancer | US10220026B2 | [227] |

| Docetaxel | Polymeric NP | Intravenous | Drug resistant cancer | Granted | World patent | Refractory cancer | WO2014210485A1 | [246] |

| Bromoenol lactone inhibitor | Dendrimers | Intravenous infusion | Inhibit bromoenol lactone | Granted | World patent | Bromoenol lactone inhibitor covalently attached dendrimers enhance the solubility, improve tolerability, and increase therapeutic index | WO2018154004A9 | [255] |

| Anticancer Drug | Polymeric micelle | Intravenous | Endogenous protein | Granted | World patent | Facilitates drug release, especially in unstable, low AUC, low Cmax, high volume of distribution, critical micelle concentration above theoretical Cmax of the drug | WO2014165829A2 | [247] |

| Anticancer Drug | Carbon nanotubes | Parenteral administration | Drug resistance decreases | Granted | United States patent | Decreases drug resistance | US20150196650A1 | [270] |

| Protein | Single-walled carbon nanotubes | Parenteral administration | Immune stimulant | Granted | United States patent | Bind to tumor vasculature and endothelial cancer cells | US20100184669A1 | [271] |

| T cell | Gold NP | Systemic administration | T-cell receptor protein | Abandoned | United States patent | Conjugation or entrapment of the gold NP enhances the EPR effect, and then the photothermal effect inhibits the growth of cancer cells | US20140086828A1 | [289] |

| Sorafenib | Metal-cluster-doped protein NP | Intravenous | EGFR | Granted | Worldwide | Metal cluster-doped protein NP enhances the drug efficacy and bioavailability by enhancing optical contrast, and magnetic contrast, modulation of zeta potential | WO2014087413A1 | [277] |

| Phospholipids containing cis-platin prodrug | MnO2 NP | Intravenous | Multidrug resistant cancer | Pending | Chinese patent | Tumor cells carry platinum through endocytosis. In the uptake of drugs, MnO2 can generate a glutathione oxidation–reduction reaction to cause hyperpyrexia and activate photothermal effects to treat lung cancer | CN111214488A | [278] |

| Anticancer drug | Metal–organic framework | Intravenous | Double effects: Metal–organic framework photothermal effect Anticancer drug inhibits cancer through a specific mechanism | Granted | Chinese patent | Photothermal effects, in addition to the loaded drugs inhibitory action, can treat cancer | CN110652497A | [279] |

| Antitumor drug | Hybrid metal–organic framework modified with cholesterol oxidase | Intravenous | Catalyze the oxidation reaction of cholesterol | Granted | Chinese patent | Hybrid metal–organic framework can catalyze the overexpression of cholesterol and overcome multidrug resistance | CN112274648A | [280] |

| Photosensitizer and chemotherapeutic drug | Polymeric NP | Intravenous | Hypoxia responsive | Granted | Chinese patent | Hypoxic response polymer NP helps generate reactive oxygen species that enhance the chemotherapeutic drug’s efficacy along with the photodynamic response | CN108653288B | [247] |

| Antitumor drug | Mesoporous silica-coated gold NP | Intravenous | pH-responsive antitumor drug carrier | Granted | Chinese patent | Photothermal effect | CN107412195B | [370] |

| Rapamycin | Zinc–organic framework | Intravenous | mTOR pathway | Pending | Chinese patent | Inhibits mTOR pathway and enhances the sensitivity of chemotherapy | CN110693883A | [312] |

| Antitumor drug | Bionic titanium dioxide | Intravenous | Generate reactive oxygen species | Granted Drugive oxygen species | Chinese patent | Reactive oxygen species can enhance the antitumor drug’s efficacy | CN109646675B | [329] |

| Drug | Nanocarrier | Composition | Cell Line | InVitro Character Results | Remarks | Refs. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Particle Size (nm) | Zeta Potential (mV) | Drug Release | ||||||

| Paclitaxel + curcumin | Solid lipid NP | Hydrogenated soybean phospholipids; 1,2-distearoyl-sn-glycero-3phosphoethanolamine-N[methoxy(polyethylene glycol)-2000]; polyvinyl pyrrolidone k15 | A549 | 121.8 ± 1.69 | 30.4 ± 1.25 | Improved tumor inhibition. Reduces P-glycoprotein efflux, reverses MDR, and down-regulates the NF-κB pathway | [201] | |

| Honokiol | Liposome | Sodium per-carbonate, cholesterol, PEG2000-DSPE | H1975, HCC827 | 130 ± 20 | −20.0 to −30.0 | Sustained manner | Shows time-dependent inhibition of degradation of HSP90 client proteins to inhibit Akt and Erk1/2, which are mutant or wild-type EGFR signaling cascade effectors | [209] |

| Baicalin | Nanoliposome | Phospholipon90H, Tween-80, citric acid, NaHCO3 | A549 | 131.7 ± 11.7 | Sustained release for 24 h up to 89.6 + 2.1%, stable for 12 months | Baicalin, the antioxidant, has antitumor activity | [210] | |

| Gold | Theranostic liposome | Distearoyl phosphatidylcholine, 1,2-distearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine (methoxy(polyethylene glycol)-5000), 1,2-distearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine-N-[amino(polyethylene glycol)-2000], cholesterol | 72.84 ± 22.49 | −20 to −40 | Sustained release | Liposomal gold liposomes act via photothermal effect, and their stability is also enhanced | [221] | |

| Docetaxel | Micelle | PLGA-PEG-Mal | A549 | 72 + 1 | Neutral | Sustained release | Higher cytotoxicity in NSCLC | [229] |

| Tretinoin | Lipidic nanocapsule | Poly(e-caprolactone), sorbitan monostearate, f polysorbate 80 | A549 | 250 | 12.7 ± 0.9 | Sustained release | Higher cytotoxicity through cell cycle arrest at the G1phase | [233] |

| Gemcitabine and clodronate | Polymeric multilayer nanocapsules | Poly-L-arginine hydrochloride, dextran sulfate sodium salt, tetramethylrhodamine isothiocyanate mixed isomers, rhodamine B, boric acid, glycerol, ethylene diamine tetraacetic acid disodium salt (EDTA), clodronate disodium tetrahydrate | A549 | ~250–500 | Neutral | Sustained release | PMC inhibited macrophage-induced tumor growth | [244] |

| siRNA and different chemotherapeutic agents | Mesoporous silica NP | A549 | 172 | -21 | Sustained release | Combination of siRNA with chemotherapeutic agents shows synergistic effect with restraint of survivin effect | [368] | |

| Silibinin | Polymeric NP | Silibinin (SB), polyvinyl alcohol (Mw 30,000–70,000 kDa), polycaprolactone (PCL), inhalable grade lactose | A549 | 108 ± 3.21–397 ± 3.19 | Neutral | Sustained release | PCL/Pluronic F68 NPs loade silibinin significantly inhibited tumor growth in lung cancer-induced rats after inhalable administration | [243] |

| Methotrexate | Gold NP | Methotrexate, HAuCl4, sodium citrate, phosphate buffer 7.4 | A549, QU-DB | 14.3 | −7.3 ± 2.5 | Gold NP, through PTT effect, enhances the drug’s efficacy | [285] | |

| Silibinin | Gold NP | HAuCl4, trisodium citrate dehydrate, silibinin, DMSO | A549 | 163 ± 5 | −22.2 ± 0.458 | Silibinin-conjugated gold NPs released pH-responsively enhanced silibinin efficacy up to 4-5 times | [287] | |

| Embelin | Silver NP | Embelin, silver nitrate | A549 | 25 | −5.42 | Embelin-biofunctionalized silver NPs exhibit significantly lower necrotic cells than apoptotic cells in A549 cancer cells in a dose-dependent manner | [294] | |

| Juniperus chinensis leaf extracts | Silver NP | Juniperus chinensis leaf extracts, silver nitrite | A549, HEK293 | 98.21 ± 1.54 | −26.5 | Juniperus Chinensis leaf extract fabricated biofunctionalized silver NPs showed better antiproliferation and apoptotic effects | [295] | |

| Cis-platin, gemcitabine | Zinc NP | Zinc oxide NP, methanol, tri-ethylamine, cis-platin, gemcitabine | A549 | 21 ± 0.4 | NA | Sustained release | NP loaded with cis-platin, gemcitabine inhibits tumor formation and enhances the apoptotic nature of the drugs | [310] |

| Iron NP | Iron NP modified with silica layer NP | Superparamagnetic iron (II,III) oxide NPs (SPIONs), tetraethyl orthosilicate, hexadecyltrimethylammonium bromide | A549BEAS-2B | 101.3 ± 2.8 | −26.1 ± 0.1 | Sustained release | Delays the proliferation of cancer cells | [315] |

| Drug | Nanocarriers | Receptors | Ligand | Composition | Cell Line | In Vitro Character Result | Remarks | Refs. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Particle Size (nm) | Zeta Potential (MV) | Drug Release | ||||||||

| Enhanced green fluorescence protein plasmid (pEGFP)+ doxorubicin | Transferrin-conjugated SLN | Transferrin | Transferrin | Enhanced green fluorescence protein plasmid (pEGFP)-N1 Soya lecithin Human transferrin | A549 | 267 | 42 | Sustained | Improves anticancer activity | [202] |

| Paclitaxel | PEGylated large liposome | Blocks cell cycle in the G2/M phase | PEG | Lipo-Cat-PEG phosphatidylcholine, cholesterol, stearylamine, and DSPE-PEG2000 | A549, LL2 | 180 | Sustained | Antitumor activity with painful neuropathy reduction | [199] | |

| Doxorubicin | Peptidomimetic conjugate (SA-5) liposome | Blocks human epidermal growth factor receptor-2 (HER2) | lipid stearic acid peptidomimetic conjugate SA-5 | Lipid dipalmitoylphosphatidylcholine Poly(ethylene glycol) distearoylphosphatidylethanolamine Cholesterol | BT474 A 549 CALC3 | 107.19 | −13.38 mV | Sustained | Antiproliferativeactivity | [215] |

| Triptolide | CPP33 peptide and monoclonal anti-CA IX antibody)-modified liposome | 3D tumor spheroids | CPP33 peptide, monoclonal anti-CA IX antibody | Anti-CA IX antibody, CPP33 peptide with a terminal cysteine, soybean lecithin, NBD-DPPE, DSPE-PEG-MAL | A549 | 137.6 ± 0.8 | Sustained | Tumor-specific targeting and increasing tumor cell penetrationwithout causing systemic toxicity | [220] | |

| Erlotinib | PEGylated lipidic nanocapsule | EGFR | PEGylated polypeptide | Poly(ethylene glycol)-b-poly(L-aspartic acid), lecithin, sunflower oil, castor oil, Tween-20, and Span 20 | HCC-827 and NCI-H358-20 | ∼200 | −20 | Sustained release | Higher cytotoxicity than erlotinib without loading in any nanocarrier | [233] |

| Plasmid-containing enhanced green fluorescence protein | Transferrin-nanostructured lipid carriers | Gene delivery | Transferrin | Soya lecithin, Maleimide-PEG2000-COOH, human transferrin (iron-free), stearic acid, L-a-phosphatidylethanolamine | A549 | 157 | +15.9 ± 1.9 | Sustained release | Gene targeting drug delivery | [238] |

| Doxorubicin, sorafenib | Folic acid Nanostructured lipid carrier | Immunotherapy | Folic acid | Folic acid, soya lecithin, maleimide-PEG2000-COOH, stearic acid | 100 | Sustained release | Helps overcome the TME, immune response enhancement, cytotoxicity | [240] | ||

| siRNA, cis-diamine platinum | Folic acid -conjugated polyamidoamine dendrimers | Folate receptor-α inhibition | Folic acid | Folic acid, | H1299, A 543 | 280 | +14.5–17.2 | Sustained release | Suitable for co-deliveryof si-RNA along with cytotoxicity | [254] |

| siRNA, myricetin | Folic acid conjugated mesoporous silica NP | Multidrug resistance protein-1, folate receptor | Folic acid | Folic acid, tetraethylorthosilicate, cetyltrimethylammonium bromide, myricetin | A549, NCI-H1299 | 109.9 | Neutral | Sustained release | It accumulates in TME and prevents colony formation by enhancing the cancer cells’ radiosensitivity | [368] |

| Bromocriptine | Carboxyl or Hydroxyl conjugated multiwalled carbon nanotubes | Dopamine receptor | Carboxyl or hydroxyl group | Carbon nanotubes, thionyl chloride, tetrahydrofuran | A549, QU-DB | 26.3–32.6 | Sustained Release | Bromocriptine act via dopamine receptor and cause cancer cell apoptosis | [268] | |

| Gold NP | Aluminum (III) phthalocyanine chloride tetra sulfonic acid and anti-CD133 bioconjugated goldNP | Photodynamic effect | Aluminum (III) phthalocyanine chloride tetra sulfonic acid and anti-CD133 antibody | Aluminum (III) phthalocyanine chloride tetra sulfonic acid, anti-CD133 antibody | A549 | 63.91 nm | −14.7 | The bioconjugate enhance the gold NPs’ photothermal activity | [286] | |

| Doxorubicin | Au–Pt NP | Photothermal/photodynamic | cRGD, Au | Gold(III) chloride trihydrate (HAuCl4·3H2O), Pluronic® F-127 (F-127), silver nitrate (AgNO3), ascorbic acid, potassium tetrachloroplatinate(II) (K2PtCl4), methyl thiazolyl tetrazolium (MTT), calcein AM, and PI, thiol poly-(ethylene glycol) succinimidylglutaramide, doxorubicin | MDA-MB231 | 78.4–85.3 | −14.8 | Sustained release | Porous Au–Pt NPs loaded with doxorubicin modified with cRGD exhibit better drug release patterns, as well as enhanced anticancer properties | [303] |

| Cantharidin | Mesoporous titanium peroxide NPs | Photodynamic, increased reactive oxygen species | YSA | Tetrabutyl titanate, (3-aminopropyl) trimethoxysilanetitanium butoxide, hydrogen peroxide, heptanoic acid, ethanol, N-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)-N-ethylcarbodiimide hydrochloride, doxorubicin and N-hydroxysuccinimide. Cantharidin (CTD) | A549 | 150 | −21.77 | YSA-modified mesoporous titanium peroxide NPs loaded with cantharidin produced reactive oxygen species and increased photodynamic lung cancer apoptosis | [329] | |

| Doxorubicin | Metal–organic framework | Enhanced the loading drug efficacy up to 5 times without affecting the normal cells | RGD | Diphenyl carbomate, KOH, gamma cyclodextrin, RGD peptide, NHS, EDC, low-molecular-weight heparin | A549 | 150 | −25.6 | Sustained release | The loaded drug efficacy enhanced the targeted sites | [85] |

| Doxorubicin | Quantum dots | Folate receptor | Folic acid, 11-mercaptoundecanoic acid | Sodium dihydrogen phosphate, disodium hydrogen phosphate, sodium chloride, potassium chloride, silver nitrate, indium(III) chloride, zinc stearate, 1-dodecanethiol, sulfur, 1-octadecene, oleylamine, MUA, dimethyl sulfoxide, cysteine, lipoic acid, NHS, EDC, doxorubicin hydrochloride, folic acid | A549 | 11–19 | −15.5 ± 3.5 | Sustained release | QD nanocrystals modified with folic acid and 11-mercaptoundecanoic acid showed improved cytotoxicity, genotoxicity, and migration inhibitory activity against A549 lung cancer cells | [355] |

| Doxorubicin | Quantum dots | Overexpressed glycoprotein CD44 | Hyaluronic acid | Dicarboxyyl-terminated poly(ethylene glycol), hyaluronic acid, zinc acetate, magnesium acetate, sodium hydroxide, dimethyl sulfoxide, anhydrous N,N-dimethylformamide, doxorubicin | A549 | −0.0521 −1.90 | Sustained release | Shows synergistic effect of Zn2+and doxorubicin for antitumor activity | [354] | |

6. Conclusions

7. Future Prospective

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- WHO. WHO Global Report on Trends in Prevalence of Tobacco Smoking 2000–2025, 2nd ed. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/272694 (accessed on 2 December 2020).

- Allemani, C.; Matsuda, T.; Di Carlo, V.; Harewood, R.; Matz, M.; Nikšić, M.; Bonaventure, A.; Valkov, M.; Johnson, C.J.; Estève, J.; et al. Global surveillance of trends in cancer survival 2000–14 (CONCORD-3): Analysis of individual records for 37 513 025 patients diagnosed with one of 18 cancers from 322 population-based registries in 71 countries. Lancet 2018, 391, 1023–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goss, P.E.; Strasser-Weippl, K.; Lee-Bychkovsky, B.L.; Fan, L.L.J.; Chavarri-Guerra, Y.; Liedke, P.E.R.; Pramesh, C.S.; Badovinac-Crnjevic, T.; Sheikine, Y.; Chen, Z.; et al. Challenges to effective cancer control in China, India, and Russia. Lancet Oncol. 2014, 15, 489–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Heyden, J.H.A.; Schaap, M.M.; Kunst, A.E.; Esnaola, S.; Borrell, C.; Cox, B.; Leinsalu, M.; Stirbu, I.; Kalediene, R.; Deboosere, P.; et al. Socioeconomic inequalities in lung cancer mortality in 16 European populations. Lung Cancer 2009, 63, 322–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walters, S.; Maringe, C.; Coleman, M.P.; Peake, M.D.; Butler, J.; Young, N.; Bergström, S.; Hanna, L.; Jakobsen, E.; Kölbeck, K.; et al. Lung cancer survival and stage at diagnosis in Australia, Canada, Denmark, Norway, Sweden and the UK: A population-based study 2004–2007. Thorax 2013, 68, 551–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Fujimoto, J.; Zhang, J.; Wedge, D.C.; Song, X.; Zhang, J.; Seth, S.; Chow, C.W.; Cao, Y.; Gumbs, C.; et al. Intratumor heterogeneity in localized lung adenocarcinomas delineated by multiregion sequencing. Science 2014, 346, 256–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alberg, A.J.; Brock, M.V.; Ford, J.G.; Samet, J.M.; Spivack, S.D. Epidemiology of lung cancer: Diagnosis and management of lung cancer, 3rd ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest 2013, 143 (Suppl. S5), e1S–e29S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devesa, S.S.; Bray, F.; Vizcaino, A.P.; Parkin, D.M. International lung cancer trends by histologic type: Male: Female differences diminishing and adenocarcinoma rates rising. Int. J. Cancer 2005, 117, 294–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasin, D.S. US Epidemiology of Cannabis Use and Associated Problems. Neuropsychopharmacol. Off. Publ. Am. Coll. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2018, 43, 195–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krewski, D.; Lubin, J.H.; Zielinski, J.M.; Alavanja, M.; Catalan, V.S.; Field, R.W.; Klotz, J.B.; Létourneau, E.G.; Lynch, C.F.; Lyon, J.L.; et al. A combined analysis of North American case-control studies of residential radon and lung cancer. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health Part A 2006, 69, 533–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bade, B.C.; Dela Cruz, C.S. Lung Cancer 2020: Epidemiology, Etiology, and Prevention. Clin. Chest Med. 2020, 41, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; He, K.; Li, Y.; Wu, Q.; Yang, P.; Wang, D. Exposure to mercury causes formation of male-specific structural deficits by inducing oxidative damage in nematodes. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2012, 79, 90–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brenner, D.R.; McLaughlin, J.R.; Hung, R.J. Previous lung diseases and lung cancer risk: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e17479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caramori, G.; Adcock, I.M.; Casolari, P.; Ito, K.; Jazrawi, E.; Tsaprouni, L.; Villetti, G.; Civelli, M.; Carnini, C.; Chung, K.F.; et al. Unbalanced oxidant-induced DNA damage and repair in COPD: A link towards lung cancer. Thorax 2011, 66, 521–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matakidou, A.; Eisen, T.; Houlston, R.S. Systematic review of the relationship between family history and lung cancer risk. Br. J. Cancer 2005, 93, 825–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caliri, A.W.; Tommasi, S.; Besaratinia, A. Relationships among smoking, oxidative stress, inflammation, macromolecular damage, and cancer. Mutat. Research. Rev. Mutat. Res. 2021, 787, 108365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaoka, K.; Kataoka, T. Confirmation of efficacy, elucidation of mechanism, and new search for indications of radon therapy. J. Clin. Biochem. Nutr. 2022, 70, 87–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valavanidis, A.; Vlachogianni, T.; Fiotakis, K. Tobacco smoke: Involvement of reactive oxygen species and stable free radicals in mechanisms of oxidative damage, carcinogenesis and synergistic effects with other respirable particles. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2009, 6, 445–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coluzzi, E.; Leone, S.; Sgura, A. Oxidative Stress Induces Telomere Dysfunction and Senescence by Replication Fork Arrest. Cells 2019, 8, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Cheresh, P.; Kamp, D.W. Molecular basis of asbestos-induced lung disease. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 2013, 8, 161–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gout, T. Role of ATP binding and hydrolysis in the gating of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator. Ann. Thorac. Med. 2012, 7, 115–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Rivera, Z.; Jube, S.; Nasu, M.; Bertino, P.; Goparaju, C.; Franzoso, G.; Lotze, M.T.; Krausz, T.; Pass, H.I.; et al. Programmed necrosis induced by asbestos in human mesothelial cells causes high-mobility group box 1 protein release and resultant inflammation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 12611–12616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klebe, S.; Leigh, J.; Henderson, D.W.; Nurminen, M. Asbestos, Smoking and Lung Cancer: An Update. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 17, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kou, F.; Wu, L.; Ren, X.; Yang, L. Chromosome Abnormalities: New Insights into Their Clinical Significance in Cancer. Mol. Ther. Oncolytics 2020, 17, 562–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weir, B.A.; Woo, M.S.; Getz, G.; Perner, S.; Ding, L.; Beroukhim, R.; Lin, W.M.; Province, M.A.; Kraja, A.; Johnson, L.A.; et al. Characterizing the cancer genome in lung adenocarcinoma. Nature 2007, 450, 893–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, H.; Bignell, G.R.; Cox, C.; Stephens, P.; Edkins, S.; Clegg, S.; Teague, J.; Woffendin, H.; Garnett, M.J.; Bottomley, W.; et al. Mutations of the BRAF gene in human cancer. Nature 2002, 417, 949–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, X.; Zhuo, M.; Su, Z.; Duan, J.; Gao, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zong, C.; Bai, H.; Chapman, A.R.; Zhao, J.; et al. Reproducible copy number variation patterns among single circulating tumor cells of lung cancer patients. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 21083–21088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cristofanilli, M.; Budd, G.T.; Ellis, M.J.; Stopeck, A.; Matera, J.; Miller, M.C.; Reuben, J.M.; Doyle, G.V.; Allard, W.J.; Terstappen, L.W.; et al. Circulating tumor cells, disease progression, and survival in metastatic breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004, 351, 781–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krebs, M.G.; Sloane, R.; Priest, L.; Lancashire, L.; Hou, J.M.; Greystoke, A.; Ward, T.H.; Ferraldeschi, R.; Hughes, A.; Clack, G.; et al. Evaluation and prognostic significance of circulating tumor cells in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. Off. J. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. 2011, 29, 1556–1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magbanua, M.J.; Sosa, E.V.; Scott, J.H.; Simko, J.; Collins, C.; Pinkel, D.; Ryan, C.J.; Park, J.W. Isolation and genomic analysis of circulating tumor cells from castration resistant metastatic prostate cancer. BMC Cancer 2012, 12, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seto, M.; Honma, K.; Nakagawa, M. Diversity of genome profiles in malignant lymphoma. Cancer Sci. 2010, 101, 573–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalmay, T.; Edwards, D.R. MicroRNAs and the hallmarks of cancer. Oncogene 2006, 25, 6170–6175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassanpour, S.H.; Dehghani, M.A. Review of cancer from perspective of molecular. J. Cancer Res. Pract. 2017, 4, 127–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazebnik, Y. What are the hallmarks of cancer? Nat. Rev. Cancer 2010, 10, 232–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macé, A.; Kutalik, Z.; Valsesia, A. Copy Number Variation. Methods Mol. Biol. 2018, 1793, 231–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zappa, C.; Mousa, S.A. Non-small cell lung cancer: Current treatment and future advances. Transl. Lung Cancer Res. 2016, 5, 288–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landesman-Milo, D.; Ramishetti, S.; Peer, D. Nanomedicine as an emerging platform for metastatic lung cancer therapy. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2015, 34, 291–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Travis, W.D.; Brambilla, E.; Nicholson, A.G.; Yatabe, Y.; Austin, J.H.M.; Beasley, M.B.; Chirieac, L.R.; Dacic, S.; Duhig, E.; Flieder, D.B.; et al. The 2015 World Health Organization Classification of Lung Tumors: Impact of Genetic, Clinical and Radiologic Advances Since the 2004 Classification. J. Thorac. Oncol. Off. Publ. Int. Assoc. Study Lung Cancer 2015, 10, 1243–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bychkov, A.; WHO Classification. Website. Available online: https://www.pathologyoutlines.com/topic/lungtumorWHO.html (accessed on 3 April 2023).

- Kim, E.S. Chemotherapy Resistance in Lung Cancer. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2016, 893, 189–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manser, R.; Wright, G.; Hart, D.; Byrnes, G.; Campbell, D.A. Surgery for early stage non-small cell lung cancer. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2005, 2005, CD004699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnes, H.; See, K.; Barnett, S.; Manser, R. Surgery for limited-stage small-cell lung cancer. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang-Lazdunski, L. Surgery for nonsmall cell lung cancer. Eur. Respir. Rev. 2013, 22, 382–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demaria, S.; Golden, E.B.; Formenti, S.C. Role of Local Radiation Therapy in Cancer Immunotherapy. JAMA Oncol. 2015, 1, 1325–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baskar, R.; Lee, K.A.; Yeo, R.; Yeoh, K.W. Cancer and radiation therapy: Current advances and future directions. Int. J. Med. Sci. 2012, 9, 193–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falls, K.C.; Sharma, R.A.; Lawrence, Y.R.; Amos, R.A.; Advani, S.J.; Ahmed, M.M.; Vikram, B.; Coleman, C.N.; Prasanna, P.G. Radiation-Drug Combinations to Improve Clinical Outcomes and Reduce Normal Tissue Toxicities: Current Challenges and New Approaches: Report of the Symposium Held at the 63rd Annual Meeting of the Radiation Research Society, 15–18 October 2017; Cancun, Mexico. Radiat. Res. 2018, 190, 350–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majeed, H.; Gupta, V. Adverse Effects Of Radiation Therapy. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, C.Y.; Ju, D.T.; Chang, C.F.; Reddy, M.P.; Velmurugan, B.K. A review on the effects of current chemotherapy drugs and natural agents in treating non-small cell lung cancer. BioMedicine 2017, 7, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiller, J.H.; Harrington, D.; Belani, C.P.; Langer, C.; Sandler, A.; Krook, J.; Zhu, J.; Johnson, D.H.; Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. Comparison of four chemotherapy regimens for advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2002, 346, 92–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebastian, N.T.; Xu-Welliver, M.; Williams, T.M. Stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT) for early stage non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC): Contemporary insights and advances. J. Thorac. Dis. 2018, 10 (Suppl. S21), S2451–S2464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- VlaskouBadra, E.; Baumgartl, M.; Fabiano, S.; Jongen, A.; Guckenberger, M. Stereotactic radiotherapy for early stage non-small cell lung cancer: Current standards and ongoing research. Transl. Lung Cancer Res. 2021, 10, 1930–1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, L.R.; Suy, S.; Collins, S.P.; Lischalk, J.W.; Yuan, B.; Saligan, L.N. Comparison of Late Urinary Symptoms Following SBRT and SBRT with IMRT Supplementation for Prostate Cancer. Curr. Urol. 2018, 11, 218–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arvizo, R.R.; Miranda, O.R.; Moyano, D.F.; Walden, C.A.; Giri, K.; Bhattacharya, R.; Robertson, J.D.; Rotello, V.M.; Reid, J.M.; Mukherjee, P. Modulating pharmacokinetics, tumor uptake and biodistribution by engineered nanoparticles. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e24374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decuzzi, P.; Lee, S.; Bhushan, B.; Ferrari, M. A theoretical model for the margination of particles within blood vessels. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2005, 33, 179–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.; Shah, S.; Thomas, A.; Ou-Yang, H.D.; Liu, Y. The influence of size, shape and vessel geometry on nanoparticle distribution. Microfluid. Nanofluidics 2013, 14, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, A.P.; Biswas, A.; Shukla, A.; Maiti, P. Targeted therapy in chronic diseases using nanomaterial-based drug delivery vehicles. Sig. Transduct. Target. Ther. 2019, 4, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steven, A.; Fisher, S.A.; Robinson, B.W. Immunotherapy for lung cancer. Respirology 2016, 21, 821–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradbury, P.A.; Shepherd, F.A. Immunotherapy for Lung Cancer. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2008, 3, S164–S170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrell, B.; Koczywas, M.; Grannis, F.; Harrington, A. Palliative care in lung cancer. Surg. Clin. N. Am. 2011, 91, 403–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansoori, B.; Mohammadi, A.; Davudian, S.; Shirjang, S.; Baradaran, B. The Different Mechanisms of Cancer Drug Resistance: A Brief Review. Adv. Pharm. Bull. 2017, 7, 339–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neubert, R.H.H. Potentials of new nanocarriers for dermal and transdermal drug delivery. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2011, 77, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Din, F.U.; Aman, W.; Ullah, I.; Qureshi, O.S.; Mustapha, O.; Shafique, S.; Zeb, A. Effective use of nanocarriers as drug delivery systems for the treatment of selected tumors. Int. J. Nanomed. 2017, 12, 7291–7309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madni, A.; Tahir, N.; Rehman, M.; Raza, A.; Mahmood, M.A.; Khan, M.I.; Kashif, P.M. Hybrid Nano-carriers for potential drug delivery. Adv. Technol. Deliv. Ther. 2017, 54–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhaliwal, A.; Zheng, G. Improving accessibility of EPR-insensitive tumor phenotypes using EPR-adaptive strategies: Designing a new perspective in nanomedicine delivery. Theranostics 2019, 9, 8091–8108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco, E.; Shen, H.; Ferrari, M. Principles of design for overcoming biological barriers to drug delivery. Nat. Biotechnol. 2015, 33, 941–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kay, M.A.; Glorioso, J.C.; Naldini, L. Viral vectors for gene therapy: The art of turning infectious agents into vehicles of therapeutics. Nat. Med. 2001, 7, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peer, D.; Karp, J.M.; Hong, S.; Farokhzad, O.C.; Margalit, R.; Langer, R. Nanocarriers as an emerging platform for cancer therapy. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2007, 2, 751–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rawal, S.; Patel, M. Bio-Nanocarriers for Lung Cancer Management: Befriending the Barriers. Nano-Micro Lett. 2021, 13, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, S.P. Drug delivery to the lungs: Challenges and opportunities. Ther. Deliv. 2017, 8, 647–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plaunt, A.J.; Nguyen, T.L.; Corboz, M.R.; Malinin, V.S.; Cipolla, D.C. Strategies to Overcome Biological Barriers Associated with Pulmonary Drug Delivery. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.M.; Faix, P.H.; Schnitzer, J.E. Overcoming key biological barriers to cancer drug delivery and efficacy. J. Control. Release Off. J. Control. Release Soc. 2017, 267, 15–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, L.; Yang, X.; Yin, Q.; Cai, K.; Wang, H.; Chaudhury, I.; Yao, C.; Zhou, Q.; Kwon, M.; Hartman, J.A.; et al. Investigating the optimal size of anticancer nanomedicine. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 15344–15349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruffin, R.E.; Dolovich, M.B.; Wolff, R.K.; Newhouse, M.T. The effects of preferential deposition of histamine in the human airway. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 1978, 117, 485–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.-S.; Tsay, R.-Y. Drug Release from a Spherical Matrix: Theoretical Analysis for a Finite Dissolution Rate Affected by Geometric Shape of Dispersed Drugs. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12, 582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, Y.; Xu, J.; Sun, X.; Ren, X.; Maharjan, A.; York, P.; Su, Y.; Li, H.; Zhang, J. Cuboidal tethered cyclodextrin frameworks tailored for hemostasis and injured vessel targeting. Theranostics 2019, 9, 2489–2504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yokoi, K.; Tanei, T.; Godin, B.; van de Ven, A.L.; Hanibuchi, M.; Matsunoki, A.; Alexander, J.; Ferrari, M. Serum biomarkers for personalization of nanotherapeutics-based therapy in different tumor and organ microenvironments. Cancer Lett. 2014, 345, 48–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yokoi, K.; Kojic, M.; Milosevic, M.; Tanei, T.; Ferrari, M.; Ziemys, A. Capillary-wall collagen as a biophysical marker of nanotherapeutic permeability into the tumor microenvironment. Cancer Res. 2014, 74, 4239–4246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beg, S.; Almalki, W.H.; Khatoon, F.; Alharbi, K.S.; Alghamdi, S.; Akhter, M.H.; Khalilullah, H.; Baothman, A.A.; Hafeez, A.; Rahman, M.; et al. Lipid/polymer-based nanocomplexes in nucleic acid delivery as cancer vaccines. Drug Discov. Today 2021, 26, 1891–1903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tenzer, S.; Docter, D.; Kuharev, J.; Musyanovych, A.; Fetz, V.; Hecht, R.; Schlenk, F.; Fischer, D.; Kiouptsi, K.; Reinhardt, C.; et al. Rapid formation of plasma protein corona critically affects nanoparticle pathophysiology. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2013, 8, 772–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nel, A.E.; Mädler, L.; Velegol, D.; Xia, T.; Hoek, E.M.; Somasundaran, P.; Klaessig, F.; Castranova, V.; Thompson, M. Understanding biophysicochemical interactions at the nano-bio interface. Nat. Mater. 2009, 8, 543–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahay, G.; Alakhova, D.Y.; Kabanov, A.V. Endocytosis of nanomedicines. J. Control. Release Off. J. Control. Release Soc. 2010, 145, 182–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvati, A.; Pitek, A.S.; Monopoli, M.P.; Prapainop, K.; Bombelli, F.B.; Hristov, D.R.; Kelly, P.M.; Åberg, C.; Mahon, E.; Dawson, K.A. Transferrin-functionalized nanoparticles lose their targeting capabilities when a biomolecule corona adsorbs on the surface. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2013, 8, 137–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Docter, D.; Distler, U.; Storck, W.; Kuharev, J.; Wünsch, D.; Hahlbrock, A.; Knauer, S.K.; Tenzer, S.; Stauber, R.H. Quantitative profiling of the protein coronas that form around nanoparticle. Nat. Protoc. 2014, 9, 2030–2044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.J.; Kim, H.J.; Yang, C.S.; Kyeong, H.H.; Choi, J.M.; Hwang, D.E.; Yuk, J.M.; Park, K.; Kim, Y.J.; Lee, S.G.; et al. A high-affinity protein binder that blocks the IL-6/STAT3 signaling pathway effectively suppresses non-small cell lung cancer. Mol. Ther. J. Am. Soc. Gene Ther. 2014, 22, 1254–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Xiong, T.; He, S.; Sun, H.; Huang, C.; Ren, X.; Zhang, J. Pulmonary targeting crosslinked cyclodextrin metal–organic frameworks for lung cancer therapy. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2021, 31, 2004550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, M.; Liang, X.; Shi, L.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, L.; Gong, Z.; Luo, S.; Wang, X.; Zhang, X. Folic acid deficiency exacerbates the inflammatory response of astrocytes after ischemia-reperfusion by enhancing the interaction between IL-6 and JAK-1/pSTAT3. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 2023, 29, 1537–1546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoffmann, M.; Gerlach, S.; Hoffmann, C.; Richter, N.; Hersch, N.; Csiszár, A.; Merkel, R.; Hoffmann, B. PEGylation and folic-acid functionalization of cationic lipoplexes-Improved nucleic acid transfer into cancer cells. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2022, 10, 1066887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, P.L.; Harada, T.; Christian, D.A.; Pantano, D.A.; Tsai, R.K.; Discher, D.E. Minimal “Self” peptides that inhibit phagocytic clearance and enhance delivery of nanoparticles. Science 2013, 339, 971–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parodi, A.; Quattrocchi, N.; van de Ven, A.L.; Chiappini, C.; Evangelopoulos, M.; Martinez, J.O.; Brown, B.S.; Khaled, S.Z.; Yazdi, I.K.; Enzo, M.V.; et al. Synthetic nanoparticle NPs functionalized with biomimetic leukocyte membranes possess cell-like functions. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2013, 8, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prapainop, K.; Witter, D.P.; Wentworth, P., Jr. A chemical approach for cell-specific targeting of nanomaterials: Small-molecule-initiated misfolding of nanoparticle corona proteins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 4100–4103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overchuk, M.; Zheng, G. Overcoming obstacles in the tumor microenvironment: Recent advancements in nanoparticle delivery for cancer theranostics. Biomaterials 2018, 156, 217–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Chen, X.; Cao, J.; Gao, H. Overcoming the biological barriers in the tumor microenvironment for improving drug delivery and efficacy. J. Mater. Chem. B 2020, 8, 6765–6781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junttila, M.R.; de Sauvage, F.J. Influence of tumour micro-environment heterogeneity on therapeutic response. Nature 2013, 501, 346–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azzi, S.; Hebda, J.K.; Gavard, J. Vascular permeability and drug delivery in cancers. Front. Oncol. 2013, 3, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, J.; Nakamura, H.; Maeda, H. The EPR effect: Unique features of tumor blood vessels for drug delivery, factors involved, and limitations and augmentation of the effect. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2011, 63, 136–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roma-Rodrigues, C.; Mendes, R.; Baptista, P.V.; Fernandes, A.R. Targeting Tumor Microenvironment for Cancer Therapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinshaw, D.C.; Shevde, L.A. The Tumor Microenvironment Innately Modulates Cancer Progression. Cancer Res. 2019, 79, 4557–4566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Xu, Z.; Alrobaian, M.; Afzal, O.; Kazmi, I.; Almalki, W.H.; Altamimi, A.S.A.; Al-Abbasi, F.A.; Alharbi, K.S.; Altowayan, W.M.; et al. EGF-functionalized lipid-polymer hybrid nanoparticles of 5-fluorouracil and sulforaphane with enhanced bioavailability and anticancer activity against colon carcinoma. Biotechnol. Appl. Biochem. 2022, 69, 2205–2221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, J.; Ameeduzzafar; Ahmad, M.Z.; Akhter, H.M. Surface-Engineered Cancer Nanomedicine: Rational Design and Recent Progress. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2020, 26, 1181–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhter, M.H.; Rizwanullah, M.; Ahmad, J.; Ahsan, M.J.; Mujtaba, M.A.; Amin, S. Nanocarriers in advanced drug targeting: Setting novel paradigm in cancer therapeutics. Artif. Cells Nanomed. Biotechnol. 2018, 46, 873–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schito, L.; Semenza, G. Hypoxia and Breast Cancer Metastasis. In Hypoxia and Cancer. Cancer Drug Discovery and Development; Melillo, G., Ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tashkin, D.P.; Ferguson, G.T. Combination bronchodilator therapy in the management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respir. Res. 2013, 14, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tammela, T.; Zarkada, G.; Wallgard, E.; Murtomäki, A.; Suchting, S.; Wirzenius, M.; Waltari, M.; Hellström, M.; Schomber, T.; Peltonen, R.; et al. Blocking VEGFR-3 suppresses angiogenic sprouting and vascular network formation. Nature 2008, 454, 656–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goel, S.; Wong, A.H.; Jain, R.K. Vascular normalization as a therapeutic strategy for malignant and nonmalignant disease. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2012, 2, a006486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigo, G.J.; Plaza, V.; Castro-Rodríguez, J.A. Comparison of three combined pharmacological approaches with tiotropium monotherapy in stable moderate to severe COPD: A systematic review. Pulm. Pharmacol. Ther. 2012, 25, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanjani, N.A.; Esmaelizad, N.; Zanganeh, S.; Gharavi, A.T.; Heidarizadeh, P.; Radfar, M.; Omidi, F.; MacLoughlin, R.; Doroudian, M. Emerging role of exosomes as biomarkers in cancer treatment and diagnosis. Crit. Rev.Oncol. Hematol. 2022, 169, 103565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, S.M.; Kang, P. Recent Advances in Nanocarrier-Assisted Therapeutics Delivery Systems. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12, 837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Conniot, J.; Amorim, J.; Jin, Y.; Prasad, R.; Yan, X.; Fan, K.; Conde, J. Nucleic acid-based therapy for brain cancer: Challenges and strategies. J. Control. Release Off. J. Control. Release Soc. 2022, 350, 80–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaughan, H.J.; Green, J.J.; Tzeng, S.Y. Cancer-Targeting Nanoparticles for Combinatorial Nucleic Acid Delivery. Adv. Mater. 2020, 32, e1901081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Y.; Cao, X.; Zheng, X.; Abbas, S.K.J.; Li, J.; Tan, W. Construction of nanocarriers based on nucleic acids and their applications in nanobiology delivery systems. Natl. Sci. Rev. 2022, 9, nwac006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendes, B.B.; Conniot, J.; Avital, A.; Yao, D.; Jiang, X.; Zhou, X.; Sharf-Pauker, N.; Xiao, Y.; Adir, O.; Liang, H.; et al. Nanodelivery of nucleic acids. Nat. Rev. Methods Prim. 2022, 2, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W.; Tang, Z.; Zhang, D.; Yu, H.; Chen, X. Coadministration of Vascular Disrupting Agents and Nanomedicines to Eradicate Tumors from Peripheral and Central Regions. Small 2015, 11, 3755–3761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sengupta, S.; Eavarone, D.; Capila, I.; Zhao, G.; Watson, N.; Kiziltepe, T.; Sasisekharan, R. Temporal targeting of tumour cells and neovasculature with a nanoscale delivery system. Nature 2005, 436, 568–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, N.; Wu, J.; Yang, C.; Yu, H.; Yang, S.; Li, T.; Chen, J.; Tang, Z.; Chen, X. Combretastatin A4 Nanoparticles Combined with Hypoxia-Sensitive Imiquimod: A New Paradigm for the Modulation of Host Immunological Responses during Cancer Treatment. Nano Lett. 2019, 19, 8021–8031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Hao, Y.; Wu, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Li, J.; Sun, X.; Liu, Y.N. Integrated Hydrogel Platform for Programmed Antitumor Therapy Based on Near Infrared-Triggered Hyperthermia and Vascular Disruption. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 21381–21390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siemann, D.W. The unique characteristics of tumor vasculature and preclinical evidence for its selective disruption by Tumor-Vascular Disrupting Agents. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2011, 37, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Schuetze, R.; Gerberich, J.L.; Lopez, R.; Odutola, S.O.; Tanpure, R.P.; Charlton-Sevcik, A.K.; Tidmore, J.K.; Taylor, E.A.-S.; Kapur, P.; et al. Demonstrating Tumor Vascular Disrupting Activity of the Small-Molecule Dihydronaphthalene Tubulin-Binding Agent OXi6196 as a Potential Therapeutic for Cancer Treatment. Cancers 2022, 14, 4208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, T.; Xiao, H.; Liu, X.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Wei, N.; Guo, X. Vascular Normalization: A New Window Opened for Cancer Therapies. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 719836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magnussen, A.L.; Mills, I.G. Vascular normalisation as the stepping stone into tumour microenvironment transformation. Br. J. Cancer 2021, 125, 324–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chauhan, V.P.; Stylianopoulos, T.; Martin, J.D.; Popović, Z.; Chen, O.; Kamoun, W.S.; Bawendi, M.G.; Fukumura, D.; Jain, R.K. Normalization of tumour blood vessels improves the delivery of nanomedicines in a size-dependent manner. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2012, 7, 383–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, Y.C.; Jin, P.R.; Chu, L.A.; Hsu, F.F.; Wang, M.R.; Chang, C.C.; Chiou, S.J.; Qiu, J.T.; Gao, D.Y.; Lin, C.C.; et al. Delivery of nitric oxide with a nanocarrier promotes tumour vessel normalization and potentiates anti-cancer therapies. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2019, 14, 1160–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bremnes, R.M.; Dønnem, T.; Al-Saad, S.; Al-Shibli, K.; Andersen, S.; Sirera, R.; Camps, C.; Marinez, I.; Busund, L.T. The Role of Tumor Stroma in Cancer Progression and Prognosis: Emphasis on Carcinoma-Associated Fibroblasts and Non-small Cell Lung Cancer. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2011, 6, 209–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Järveläinen, H.; Sainio, A.; Koulu, M.; Wight, T.N.; Penttinen, R. Extracellular matrix molecules: Potential targets in pharmacotherapy. Pharmacol. Rev. 2009, 61, 198–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denton, C.P.; Merkel, P.A.; Furst, D.E.; Khanna, D.; Emery, P.; Hsu, V.M.; Silliman, N.; Streisand, J.; Powell, J.; Akesson, A.; et al. Clinical Trials Consortium. Recombinant human anti-transforming growth factor beta1 antibody therapy in systemic sclerosis: A multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled phase I/II trial of CAT-192. Arthritis Rheum. 2007, 56, 323–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuster, L.; Seifert, O.; Vollmer, S.; Kontermann, R.E.; Schlosshauer, B.; Hartmann, H. Immunoliposomes for Targeted Delivery of an Antifibrotic Drug. Mol. Pharm. 2015, 12, 3146–3157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dykman, L.A.; Khlebtsov, N.G. Gold nanoparticles in chemo-, immuno-, and combined therapy: Review. Biomed. Opt. Express 2019, 10, 3152–3182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwogu, J.I.; Geenen, D.; Bean, M.; Brenner, M.C.; Huang, X.; Buttrick, P.M. Inhibition of collagen synthesis with prolyl 4-hydroxylase inhibitor improves left ventricular function and alters the pattern of left ventricular dilatation after myocardial infarction. Circulation 2001, 104, 2216–2221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Li, J.; Jiang, X.; Liu, S.; Liu, Y.; Chen, W.; Yang, J.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, W. Melatonin enhances atherosclerotic plaque stability by inducing prolyl-4-hydroxylase α1 expression. J. Hypertens. 2019, 37, 964–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almokadem, S.; Belani, C.P. Volociximab in cancer. Expert Opin. Biol. Ther. 2012, 12, 251–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ingber, D.E. Can cancer be reversed by engineering the tumor microenvironment? Semin. Cancer Biol. 2008, 18, 356–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.; Wang, L.; Sun, T.; Tang, H.; Bui, B.; Cao, D.; Wang, R.; Chen, W. Characterization of nanoparticles combining polyamine detection with photodynamic therapy. Commun. Biol. 2021, 4, 803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.X.; He, P.P.; Qi, G.B.; Gao, Y.J.; Lin, Y.X.; Yang, C.; Yang, P.P.; Hao, H.; Wang, L.; Wang, H. Transformable Nanomaterials as an Artificial Extracellular Matrix for Inhibiting Tumor Invasion and Metastasis. ACS Nano 2017, 11, 4086–4096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geckil, H.; Xu, F.; Zhang, X.; Moon, S.; Demirci, U. Engineering hydrogels as extracellular matrix mimics. Nanomedicine 2010, 5, 469–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Ahrens, D.; Bhagat, T.D.; Nagrath, D.; Maitra, A.; Verma, A. The role of stromal cancer-associated fibroblasts in pancreatic cancer. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2017, 10, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngan, C.Y.; Yamamoto, H.; Seshimo, I.; Tsujino, T.; Man-i, M.; Ikeda, J.I.; Konishi, K.; Takemasa, I.; Ikeda, M.; Sekimoto, M.; et al. Quantitative evaluation of vimentin expression in tumour stroma of colorectal cancer. Br. J. Cancer 2007, 96, 986–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiu, Y.; Peränen, J.; Schaible, N.; Cheng, F.; Eriksson, J.E.; Krishnan, R.; Lappalainen, P. Vimentin intermediate filaments control actin stress fiber assembly through GEF-H1 and RhoA. J. Cell Sci. 2017, 130, 892–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javed, R.; Zia, M.; Naz, S.; Aisida, S.O.; Ain, N.U.; Ao, Q. Role of capping agents in the application of nanoparticles in biomedicine and environmental remediation: Recent trends and future prospects. J. Nanobiotechnology 2020, 18, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen, K.; Heirbaut, L.; Cheng, J.D.; Joossens, J.; Ryabtsova, O.; Cos, P.; Maes, L.; Lambeir, A.M.; De Meester, I.; Augustyns, K.; et al. Selective Inhibitors of Fibroblast Activation Protein (FAP) with a (4-Quinolinoyl)-glycyl-2-cyanopyrrolidine Scaffold. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2013, 4, 491–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chauhan, V.P.; Chen, I.X.; Tong, R.; Ng, M.R.; Martin, J.D.; Naxerova, K.; Wu, M.W.; Huang, P.; Boucher, Y.; Kohane, D.S.; et al. Reprogramming the microenvironment with tumor-selective angiotensin blockers enhances cancer immunotherapy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 10674–10680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.; Jia, H.H.; Xu, Y.Q.; Zhou, X.; Zhao, X.H.; Wang, Y.F.; Song, X.; Zhu, Z.Y.; Sun, T.; Dou, Y.; et al. Paracrine and epigenetic control of CAF-induced metastasis: The role of HOTAIR stimulated by TGF-ß1 secretion. Mol. Cancer 2018, 17, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, W.; Bu, W.; Shen, B.; He, Q.; Cui, Z.; Liu, Y.; Zheng, X.; Zhao, K.; Shi, J. Intelligent MnO2 Nanosheets Anchored with Upconversion Nanoprobes for Concurrent pH-/H2O2-Responsive UCL Imaging and Oxygen-Elevated Synergetic Therapy. Adv. Mater. 2015, 27, 4155–4161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Zhang, M.; Tang, Z.; He, M.; Bu, W. Modulating Hypoxia via Nanomaterials Chemistry for Efficient Treatment of Solid Tumors. Acc. Chem. Res. 2018, 51, 2502–2511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baran, N.; Konopleva, M. Molecular Pathways: Hypoxia-Activated Prodrugs in Cancer Therapy. Clin. Cancer Res. Off. J. Am. Assoc. Cancer Res. 2017, 23, 2382–2390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayaprakash, P.; Ai, M.; Liu, A.; Budhani, P.; Bartkowiak, T.; Sheng, J.; Ager, C.; Nicholas, C.; Jaiswal, A.R.; Sun, Y.; et al. Targeted hypoxia reduction restores T cell infiltration and sensitizes prostate cancer to immunotherapy. J. Clin. Investig. 2018, 128, 5137–5149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, Y.T.; Zhou, T.J.; Cui, P.F.; He, Y.J.; Chang, X.; Xing, L.; Jiang, H.L. Modulation of intracellular oxygen pressure by dual-drug nanoparticles to enhance photodynamic therapy. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2019, 29, 1806708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, G.; Xu, Z.P.; Li, L. Manipulating extracellular tumour pH: An effective target for cancer therapy. RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 22182–22192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ando, H.; Eshima, K.; Ishida, T. Neutralization of Acidic Tumor Microenvironment (TME) with Daily Oral Dosing of Sodium Potassium Citrate (K/Na Citrate) Increases Therapeutic Effect of Anti-cancer Agent in Pancreatic Cancer Xenograft Mice Model. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2021, 44, 266–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pilon-Thomas, S.; Kodumudi, K.N.; El-Kenawi, A.E.; Russell, S.; Weber, A.M.; Luddy, K.; Damaghi, M.; Wojtkowiak, J.W.; Mulé, J.J.; Ibrahim-Hashim, A.; et al. Neutralization of Tumor Acidity Improves Antitumor Responses to Immunotherapy. Cancer Res. 2016, 76, 1381–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iessi, E.; Logozzi, M.; Mizzoni, D.; Di Raimo, R.; Supuran, C.T.; Fais, S. Rethinking the Combination of Proton Exchanger Inhibitors in Cancer Therapy. Metabolites 2017, 8, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Milito, A.; Fais, S. Tumor acidity, chemoresistance and proton pump inhibitors. Future Oncol. 2005, 1, 779–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, P.; Ferraro, M.; Haag, R.; Quadir, M. Dendritic Polyglycerol-Derived Nano-Architectures as Delivery Platforms of Gemcitabine for Pancreatic Cancer. Macromol. Biosci. 2019, 19, e1900073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gadiyar, V.; Patel, G.; Davra, V. Immunological role of TAM receptors in the cancer microenvironment. Int. Rev. Cell Mol. Biol. 2020, 357, 57–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phuengkham, H.; Ren, L.; Shin, I.W.; Lim, Y.T. Nanoengineered Immune Niches for Reprogramming the Immunosuppressive Tumor Microenvironment and Enhancing Cancer Immunotherapy. Adv. Mater. 2019, 31, e1803322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zanganeh, S.; Hutter, G.; Spitler, R.; Lenkov, O.; Mahmoudi, M.; Shaw, A.; Pajarinen, J.S.; Nejadnik, H.; Goodman, S.; Zanganeh, S.; et al. Iron oxide nanoparticles inhibit tumour growth by inducing pro-inflammatory macrophage polarization in tumour tissues. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2016, 11, 986–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulens-Arias, V.; Rojas, J.M.; Pérez-Yagüe, S.; Morales, M.P.; Barber, D.F. Polyethylenimine-coated SPIONs trigger macrophage activation through TLR-4 signaling and ROS production and modulate podosome dynamics. Biomaterials 2015, 52, 494–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zhou, L.; Zhou, J.; Li, Q.; Ji, Q. Underlying mechanisms and drug intervention strategies for the tumour microenvironment. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2021, 40, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groth, C.; Hu, X.; Weber, R.; Fleming, V.; Altevogt, P.; Utikal, J.; Umansky, V. Immunosuppression mediated by myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) during tumour progression. Br. J. Cancer 2019, 120, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mi, Y.; Guo, N.; Luan, J.; Cheng, J.; Hu, Z.; Jiang, P.; Jin, W.; Gao, X. The Emerging Role of Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells in the Glioma Immune Suppressive Microenvironment. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dijk, M.V.; Mundt, C.A.; Ritter, G.; Schaer, D.; Wolchok, J.D.; Merghoub, T.; Savitsky, D.A.; Wilson, N.S. Anti-Ctla-4 Antibodies and Methods of Use Thereof. US20190135919A1, 9 May 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Amano, T.; Yu, H.; Amano, M.; Leyder, E.; Badiola, M.; Ray, P.; Kim, J.; Ko, A.C.; Achour, A.; Weng, N.P.; et al. Controllable self-replicating RNA vaccine delivered intradermally elicits predominantly cellular immunity. IScience 2023, 26, 106335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbeit, R.D.; Ragan, P.M. Methods for Treating Cancer. JP2019502741A, 31 January 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Bertrand, N.; Wu, J.; Xu, X.; Kamaly, N.; Farokhzad, O.C. Cancer nanotechnology: The impact of passive and active targeting in the era of modern cancer biology. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2014, 66, 2–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tahmasbi Rad, A.; Chen, C.W.; Aresh, W.; Xia, Y.; Lai, P.S.; Nieh, M.P. Combinational Effects of Active Targeting, Shape, and Enhanced Permeability and Retention for Cancer Theranostic Nanocarriers. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 10505–10519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, J.; Bhujwalla, Z.M. Biomimetic Nanoparticles Camouflaged in Cancer Cell Membranes and Their Applications in Cancer Theranostics. Front. Oncol. 2019, 9, 1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sushnitha, M.; Evangelopoulos, M.; Tasciotti, E.; Taraballi, F. Cell Membrane-Based Biomimetic Nanoparticles and the Immune System: Immunomodulatory Interactions to Therapeutic Applications. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2020, 8, 627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, S.; Ahmad, A.; Wang, A.; Raza, M.; Jan, A.U.; Tahir, K.; Rahman, A.U.; Qipeng, Y. Bio-fabrication of catalytic platinum nanoparticles and their in vitro efficacy against lungs cancer cells line (A549). J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 2017, 173, 368–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, S.; Azad, A.K.; Nawaz, A.; Shah, K.U.; Iqbal, M.; Albadrani, G.M.; Al-Joufi, F.A.; Sayed, A.A.; Abdel-Daim, M.M. 5-Fluorouracil-Loaded Folic-Acid-Fabricated Chitosan Nanoparticles for Site-Targeted Drug Delivery Cargo. Polymers 2022, 14, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, K.; Zhang, W.; Yu, L.; Yu, Y.; Liu, H.; Zhang, X. Transferrin-Decorated Protein-Lipid Hybrid Nanoparticle Efficiently Delivers Cisplatin and Docetaxel for Targeted Lung Cancer Treatment. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 2021, 15, 3475–3486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, B.; Chauhan, M.; Shekhar, S.; Kumar, A.; Mehata, A.K.; Nayak, A.K.; Dutt, R.; Garg, V.; Kailashiya, V.; Muthu, M.S.; et al. RGD-decorated PLGA nanoparticles improved effectiveness and safety of cisplatin for lung cancer therapy. Int. J. Pharm. 2023, 633, 122587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhter, M.H.; Beg, S.; Tarique, M.; Malik, A.; Afaq, S.; Choudhry, H.; Hosawi, S. Receptor-based targeting of engineered nanocarrier against solid tumors: Recent progress and challenges ahead. Biochim. Et Biophys. Acta. Gen. Subj. 2021, 1865, 129777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Yu, L.; Ji, T.; Wang, C. Tumor Microenvironment-Responsive Peptide-Based Supramolecular Drug Delivery System. Front. Chem. 2020, 8, 549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, Q.; Chen, J.; Yan, J.; Cai, S.; Xiong, H.; Liu, Y.; Peng, D.; Mo, M.; Liu, Z. Tumor microenvironment responsive drug delivery systems. Asian J. Pharm. Sci. 2020, 15, 416–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morales-Cruz, M.; Delgado, Y.; Castillo, B.; Figueroa, C.M.; Molina, A.M.; Torres, A.; Milián, M.; Griebenow, K. Smart Targeting To Improve Cancer Therapeutics. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 2019, 13, 3753–3772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Wang, H.; Tan, T.; Li, J.; Wang, Z.; Li, Y. Rational Design of Nanoparticles with Deep Tumor Penetration for Effective Treatment of Tumor Metastasis. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2018, 28, 1801840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Cun, X.; Ruan, S.; Liu, R.; Xiao, W.; Yang, X.; Yang, Y.; Yang, C.; Gao, H. Enzyme-triggered size shrink and laser-enhanced NO release nanoparticles for deep tumor penetration and combination therapy. Biomaterials 2018, 168, 64–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Ding, J.; Wang, Y.; Cheng, J.; Ji, S.; Zhuang, X.; Chen, X. Sequentially Responsive Shell-Stacked Nanoparticles for Deep Penetration into Solid Tumors. Adv. Mater. 2017, 29, 1701170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, R.; Sunil, D.; Ningthoujam, R.S. Hypoxia-responsive nanoparticle based drug delivery systems in cancer therapy: An up-to-date review. J. Control. Release Off. J. Control. Release Soc. 2020, 319, 135–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, Y.; Zhu, J.; Li, Y.; Shi, H.; Gong, Y.; Li, R.; Huo, Q.; Ma, T.; Liu, Y. Size shrinkable drug delivery nanosystems and priming the tumor microenvironment for deep intratumoral penetration of nanoparticles. J. Control. Release Off. J. Control. Release Soc. 2018, 277, 35–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; An, L.; Tian, Q.; Lin, J.; Yang, S. Tumor-microenvironment activated second near-infrared agents for tumor imaging and therapy. J. Mater. Chem. B 2020, 8, 4738–4747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Valdepérez, D.; Jin, Q.; Yang, B.; Li, Z.; Wu, Y.; Pelaz, B.; Parak, W.J.; Ji, J. Dual Enzymatic Reaction-Assisted Gemcitabine Delivery Systems for Programmed Pancreatic Cancer Therapy. ACS Nano 2017, 11, 1281–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Wu, W.; Xiu, K.; Xu, F.; Li, Z.; Li, J. Doxorubicin loaded pH-responsive micelles capable of rapid intracellular drug release for potential tumor therapy. J. Biomed. Nanotechnol. 2014, 10, 1480–1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thambi, T.; Deepagan, V.G.; Yoon, H.Y.; Han, H.S.; Kim, S.H.; Son, S.; Jo, D.G.; Ahn, C.H.; Suh, Y.D.; Kim, K.; et al. Hypoxia-responsive polymeric nanoparticles for tumor-targeted drug delivery. Biomaterials 2014, 35, 1735–1743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hossen, S.; Hossain, M.K.; Basher, M.K.; Mia, M.N.H.; Rahman, M.T.; Uddin, M.J. Smart nanocarrier-based drug delivery systems for cancer therapy and toxicity studies: A review. J. Adv. Res. 2018, 15, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Seebacher, N.; Shi, H.; Kan, Q.; Duan, Z. Novel strategies to prevent the development of multidrug resistance (MDR) in cancer. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 84559–84571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Housman, G.; Byler, S.; Heerboth, S.; Lapinska, K.; Longacre, M.; Snyder, N.; Sarkar, S. Drug resistance in cancer: An overview. Cancers 2014, 6, 1769–1792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sever, R.; Brugge, J.S. Signal transduction in cancer. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2015, 5, a006098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, C.; Tong, L.; Feng, J.; Fu, J. Recent Advances in Stimuli-Responsive Release Function Drug Delivery Systems for Tumor Treatment. Molecules 2016, 21, 1715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alves, A.C.S.; Bruinsmann, F.A.; Guterres, S.S.; Pohlmann, A.R. Organic Nanocarriers for Bevacizumab Delivery: An Overview of Development, Characterization and Applications. Molecules 2021, 26, 4127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Bariwal, J.; Kumar, V.; Tan, C.; Mahato, R.I. Organic nanocarriers for delivery and targeting of therapeutic agents for cancer treatment. Adv. Ther. 2020, 3, 1900136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelaziz, H.M.; Freag, M.S.; Elzoghby, A.O. Solid lipid nanoparticle-based drug delivery for lung cancer. In Nanotechnology-Based Targeted Drug Delivery Systems for Lung Cancer; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2019; pp. 95–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhiman, N.; Awasthi, R.; Sharma, B.; Kharkwal, H.; Kulkarni, G.T. Lipid Nanoparticles as Carriers for Bioactive Delivery. Front. Chem. 2021, 9, 580118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kutlu, M.; Kus, G.; Ulukaya, E. Lipid Nanoparticles Loaded with Ceranib-2 as Anticancer Agents. WO Patent 2020018049A3, 27 February 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Naseri, N.; Valizadeh, H.; Zakeri-Milani, P. Solid Lipid Nanoparticles and Nanostructured Lipid Carriers: Structure, Preparation and Application. Adv. Pharm. Bull. 2015, 5, 305–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.H.; Jin, S.E.; Lee, M.K.; Lim, S.J.; Park, J.S.; Kim, B.G.; Ahn, W.S.; Kim, C.K. Novel cationic solid lipid nanoparticles enhanced p53 gene transfer to lung cancer cells. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. Off. J. Arb. Fur Pharm. V 2008, 68, 545–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naguib, Y.W.; Rodriguez, B.L.; Li, X.; Hursting, S.D.; Williams, R.O.; Cui, Z., 3rd. Solid lipid nanoparticle formulations of docetaxel prepared with high melting point triglycerides: In vitro and in vivo evaluation. Mol. Pharm. 2014, 11, 1239–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, Z. Preparation Method of Folic Acid Targeted Silymarin Solid Lipid Nanoparticles. China Patent 111195239A, 26 May 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Chamundeeswari, M.; Jeslin, J.; Verma, M.L. Nanocarriers for drug delivery applications. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2019, 17, 849–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, S.; Zimmer, A.; Pardeike, J. Solid Lipid Nanoparticles (SLN) and Nanostructured Lipid Carriers (NLC) for pulmonary application: A review of the state of the art. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. Off. J. Arb. Fur Pharm. V 2014, 86, 7–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Jia, Y. Preparation and characterization of solid lipid nanoparticles loaded with epirubicin for pulmonary delivery. Die Pharm. Int. J. Pharm. Sci. 2010, 65, 585–587. [Google Scholar]

- da Rocha, M.C.O.; da Silva, P.B.; Radicchi, M.A.; Andrade, B.Y.G.; de Oliveira, J.V.; Venus, T.; Merker, C.; Estrela-Lopis, I.; Longo, J.P.F.; Báo, S.N. Docetaxel-loaded solid lipid nanoparticles prevent tumor growth and lung metastasis of 4T1 murine mammary carcinoma cells. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2020, 18, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pi, C.; Zhao, W.; Zeng, M.; Yuan, J.; Shen, H.; Li, K.; Su, Z.; Liu, Z.; Wen, J.; Song, X.; et al. Anti-lung cancer effect of paclitaxel solid lipid nanoparticles delivery system with curcumin as co-loading partner in vitro and in vivo. Drug Deliv. 2022, 29, 1878–1891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Zhang, P.; Chen, Y.; Sun, J.; Kong, F. Co-delivery of plasmid DNA and doxorubicin by solid lipid nanoparticles for lung cancer therapy. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2014, 34, 191–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pilch, E.; Musiał, W. Liposomes with an Ethanol Fraction as an Application for Drug Delivery. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 3806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sercombe, L.; Veerati, T.; Moheimani, F.; Wu, S.Y.; Sood, A.K.; Hua, S. Advances and Challenges of Liposome Assisted Drug Delivery. Front. Pharmacol. 2015, 6, 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skupin-Mrugalska, P. Liposome-based drug delivery for lung cancer. In Nanotechnology-Based Targeted Drug Delivery Systems for Lung Cancer; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2019; pp. 123–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaihua, L.; Liang, H.; Meiling, Z. Active Targeting Liposome for Resisting Lung Cancer and Preparing Method and Application of Active Targeting Liposome. China Patent 105726483B, 3 February 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Blanchett, S.F.; Drummond, D.C.; Fitzgerald, J.B.; Moyo, V. Combination Therapy Using Liposomal Irinotecan and PARP Inhibitors for Cancer Treatment. Japanese Patent 2018528184A, 27 September 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava, M.K.; Zhu, L.; Harris-White, M.; Kar, U.K.; Huang, M.; Johnson, M.F.; Lee, J.M.; Elashoff, D.; Strieter, R.; Dubinett, S.; et al. Myeloid suppressor cell depletion augments antitumor activity in lung cancer. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e40677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbarzadeh, A.; Rezaei-Sadabady, R.; Davaran, S.; Joo, S.W.; Zarghami, N.; Hanifehpour, Y.; Samiei, M.; Kouhi, M.; Nejati-Koshki, K. Liposome: Classification, preparation, and applications. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2013, 8, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Wu, W.; Wen, J.; Ye, H.; Luo, H.; Bai, P.; Tang, M.; Wang, F.; Zheng, L.; Yang, S.; et al. Liposomal honokiol induced lysosomal degradation of Hsp90 client proteins and protective autophagy in both gefitinib-sensitive and gefitinib-resistant NSCLC cells. Biomaterials 2017, 141, 188–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Liang, J.; Zheng, X.; Pi, C.; Liu, H.; Yang, H.; Zou, Y.; Ye, Y.; Zhao, L. Lung-targeting drug delivery system of baicalin-loaded nanoliposomes: Development, biodistribution in rabbits, and pharmacodynamics in nude mice bearing orthotopic human lung cancer. Int. J. Nanomed. 2016, 12, 251–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabarnick Portnoy, E.; Andriyanov, A.V.; Han, H.; Eyal, S.; Barenholz, Y. PEGylated Liposomes Remotely Loaded with the Combination of Doxorubicin, Quinine, and Indocyanine Green Enable Successful Treatment of Multidrug-Resistant Tumors. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 2181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kibria, G.; Hatakeyama, H.; Sato, Y.; Harashima, H. Anti-Tumor Effect via Passive Anti-angiogenesis of PEGylated Liposomes Encapsulating Doxorubicin in Drug Resistant Tumors. Int. J. Pharm. 2016, 509, 178–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabizon, A.; Martin, F. Polyethylene glycol-coated (pegylated) liposomal doxorubicin. Rationale for use in solid tumours. Drugs 1997, 54 (Suppl. S4), 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiménez-López, J.; Bravo-Caparrós, I.; Cabeza, L.; Nieto, F.R.; Ortiz, R.; Perazzoli, G.; Fernández-Segura, E.; Cañizares, F.J.; Baeyens, J.M.; Melguizo, C.; et al. Paclitaxel antitumor effect improvement in lung cancer and prevention of the painful neuropathy using large pegylated cationic liposomes. Biomed. Pharmacother. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021, 133, 111059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapra, P.; Tyagi, P.; Allen, T.M. Ligand-targeted liposomes for cancer treatment. Curr. Drug Deliv. 2005, 2, 369–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, B.; Tai, H.C.; Xue, W.; Lee, L.J.; Lee, R.J. Receptor-targeted nanocarriers for therapeutic delivery to cancer. Mol. Membr. Biol. 2010, 27, 286–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noble, G.T.; Stefanick, J.F.; Ashley, J.D.; Kiziltepe, T.; Bilgicer, B. Ligand-targeted liposome design: Challenges and fundamental considerations. Trends Biotechnol. 2014, 32, 32–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naik, H.; Sonju, J.J.; Singh, S.; Chatzistamou, I.; Shrestha, L.; Gauthier, T.; Jois, S. Lipidated Peptidomimetic Ligand-Functionalized HER2 Targeted Liposome as Nano-Carrier Designed for Doxorubicin Delivery in Cancer Therapy. Pharmaceuticals 2021, 14, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.; Zhang, X.; Chen, H.; Bian, Z.; Zhang, G.; Riaz, M.K.; Tyagi, D.; Lin, G.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, J.; et al. Dual-ligand modified liposomes provide effective local targeted delivery of lung-cancer drug by antibody and tumor lineage-homing cell-penetrating peptide. Drug Deliv. 2018, 25, 256–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthu, M.S.; Feng, S.S. Theranostic liposomes for cancer diagnosis and treatment: Current development and pre-clinical success. Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 2013, 10, 151–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, M.; Kim, G.; Lee, W.; Baek, S.; Jung, H.N.; Im, H.-J. Development of theranostic dual-layered Au-liposome for effective tumor targeting and photothermal therapy. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2021, 19, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karpuz, M.; Silindir-Gunay, M.; Ozer, A.Y.; Ozturk, S.C.; Yanik, H.; Tuncel, M.; Aydin, C.; Esendagli, G. Diagnostic and therapeutic evaluation of folate-targeted paclitaxel and vinorelbine encapsulating theranostic liposomes for non-small cell lung cancer. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. Off. J. Eur. Fed. Pharm. Sci. 2021, 156, 105576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Zhang, E.; Yang, J.; Cao, Z. Strategies to improve micelle stability for drug delivery. Nano Res. 2018, 11, 4985–4998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanafy, N.A.N.; El-Kemary, M.; Leporatti, S. Micelles Structure Development as a Strategy to Improve Smart Cancer Therapy. Cancers 2018, 10, 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panagi, M.; Mpekris, F.; Chen, P.; Voutouri, C.; Nakagawa, Y.; Martin, D.J.; Hiroko, H.; Hashimoto, H.; Demetriou, P.; Pierides, C.; et al. Polymeric micelles effectively reprogram the tumor microenvironment to potentiate nano-immunotherapy in mouse breast cancer models. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 7165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kinoh, H.; Kataoka, K.; Cabral, H.; Miura, Y.; Fukushima, S.; Nishiyama, N.; Chida, T. Micelle Containing Epirubicin-Complexed Block Copolymer and Anti-Cancer Agent, and Pharmaceutical Composition Containing Said Micelle Applicable to Treatment of Cancer, Resistant Cancer or Metastatic Cancer. US Patent 10220026B2, 5 March 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, D.W.; Kim, S.Y.; Kim, H.K.; Kim, S.W.; Shin, S.W.; Kim, J.S.; Park, K.; Lee, M.Y.; Heo, D.S. Multicenter phase II trial of Genexol-PM, a novel Cremophor-free, polymeric micelle formulation of paclitaxel, with cisplatin in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. Ann. Oncol. Off. J. Eur. Soc. Med. Oncol. 2007, 18, 2009–2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]