Molecular Mechanisms and Signaling Pathways Underlying the Therapeutic Potential of Thymoquinone Against Colorectal Cancer

Abstract

1. Introduction

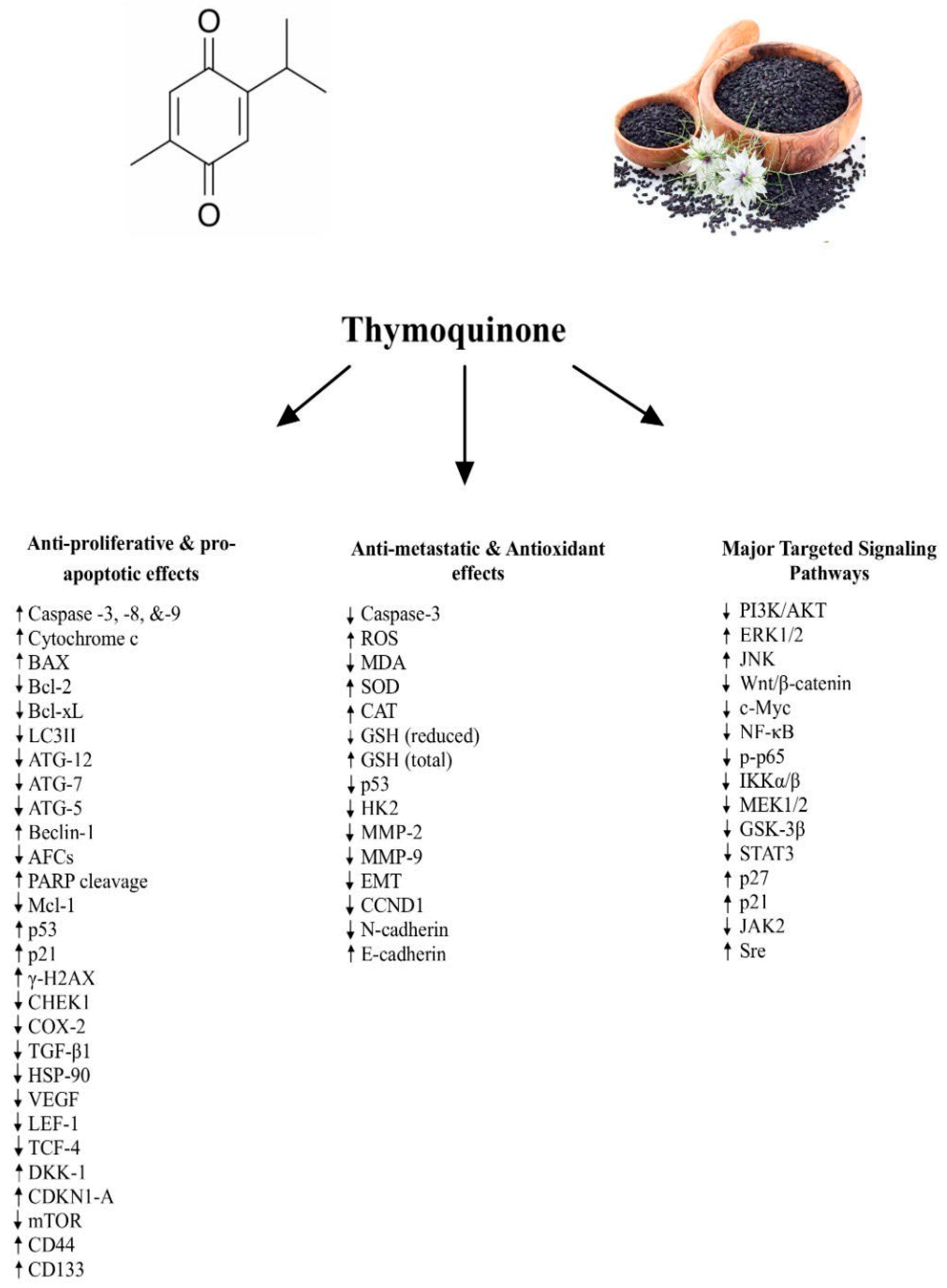

2. Search Methodology

3. Anti-Proliferative and Pro-Apoptotic Effects of TQ

4. Anti-Metastatic and Antioxidant Effects of TQ

5. Signaling Pathways Underlying the Anti-Cancer Effects of TQ

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Colorectal Cancer Statistics. Available online: https://www.cancer.org/cancer/types/colon-rectal-cancer/about/key-statistics.html (accessed on 12 October 2024).

- Hardcastle, J. Colorectal cancer. CA Cancer J. Clin. 1993, 47, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wancata, L.M.; Banerjee, M.; Muenz, D.G.; Haymart, M.R.; Wong, S.L. Conditional survival in advanced colorectal cancer and surgery. J. Surg. Res. 2016, 201, 196–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azwar, S.; Seow, H.F.; Abdullah, M.; Faisal Jabar, M.; Mohtarrudin, N. Recent updates on mechanisms of resistance to 5-Fluorouracil and reversal strategies in colon cancer treatment. Biology 2021, 10, 854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nan, Y.; Su, H.; Zhou, B.; Liu, S. The function of natural compounds in important anticancer mechanisms. Front. Oncol. 2023, 12, 1049888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imran, M.; Rauf, A.; Khan, I.A.; Shahbaz, M.; Qaisrani, T.B.; Fatmawati, S.; Abu-Izneid, T.; Imran, A.; Rahman, K.U.; Gondal, T.A. Thymoquinone: A Novel Strategy to Combat cancer: A review. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2018, 106, 390–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almajali, B.; Al-Jamal, H.; Taib, W.R.W.; Ismail, I.; Johan, M.F.; Doolaanea, A.A.; Ibrahim, W.N. Thymoquinone, as a novel therapeutic candidate of cancers. Pharmaceuticals 2021, 14, 369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A.; Husain, A.; Mujeeb, M.; Khan, S.A.; Najmi, A.K.; Siddique, N.A.; Damanhouri, Z.A.; Anwar, F. A review on therapeutic potential of Nigella sativa: A miracle herb. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Biomed. 2013, 3, 337–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majdalawieh, A.F.; Fayyad, M.W. Immunomodulatory and anti-inflammatory action of Nigella sativa and thymoquinone: A comprehensive review. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2015, 28, 295–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khader, M.; Eckl, P.M. Thymoquinone: An emerging natural drug with a wide range of medical applications. Iran. J. Basic Med. Sci. 2014, 17, 950–957. [Google Scholar]

- Majdalawieh, A.F.; Fayyad, M.W.; Nasrallah, G.K. Anti-cancer properties and mechanisms of action of thymoquinone, the major active ingredient of Nigella sativa. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2017, 57, 3911–3928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, M.; Borgmann, M.; Oberhuber, G.; Evstatiev, R.; Jimenez, K.; Dammann, K.W.; Jambrich, M.; Khare, V.; Campregher, C.; Ristl, R.; et al. Thymoquinone attenuates tumor growth in ApcMin mice by interference with Wnt-signaling. Mol. Cancer 2013, 12, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, H.; Chen, M.; Day, C.H.; Lin, Y.; Li, S.; Tu, C.; Padma, V.V.; Shih, H.; Kuo, W.; Huang, C. Thymoquinone suppresses migration of LoVo human colon cancer cells by reducing prostaglandin E2 induced COX-2 activation. World J. Gastroenterol. 2017, 23, 1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Özkoç, M.; Mutlu Altundag, E. Antiproliferative effect of thymoquinone on human colon cancer cells: Is it dependent on glycolytic pathway? Acıbadem Üniversitesi Sağlık Bilim. Derg. 2023, 14, 103–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gali-Muhtasib, H.; Ocker, M.; Kuester, D.; Krueger, S.; El-Hajj, Z.; Diestel, A.; Evert, M.; El-Najjar, N.; Peters, B.; Jurjus, A.; et al. Thymoquinone reduces mouse colon tumor cell invasion and inhibits tumor growth in murine colon cancer models. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2008, 12, 330–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ballout, F.; Monzer, A.; Fatfat, M.; Ouweini, H.E.; Jaffa, M.A.; Abdel-Samad, R.; Darwiche, N.; Abou-Kheir, W.; Gali-Muhtasib, H. Thymoquinone induces apoptosis and DNA damage in 5-Fluorouracil-resistant colorectal cancer stem/progenitor cells. Oncotarget 2020, 11, 2959–2972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, W.; Mahdy, E.; Abdu, S.; El Baseer, M.A. Effect of thymoquinone and allicin on some antioxidant parameters in cancer prostate (PC3) and colon cancer (Caco2) cell lines. Sci. J. Al Azhar Med. Fac. Girls 2020, 4, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karim, S.; Burzangi, A.S.; Ahmad, A.; Siddiqui, N.A.; Ibrahim, I.M.; Sharma, P.; Abualsunun, W.A.; Gabr, G.A. PI3K-AKT pathway modulation by thymoquinone limits tumor growth and glycolytic metabolism in colorectal cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 2305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabet-Helal, S. Thymoquinone: In vitro potential cytotoxic agent against colorectal cancer. South Asian J. Exp. Biol. 2020, 10, 455–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mounir, T. Antioxidant and anticancer effects of thymoquinone on colorectal cancer cells. Am. J. Biomed. Sci. Res. 2022, 16, 606–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norsharina, I.; Maznah, I.; Aied, A.; Ghanya, A.; Ehsan, S. Thymoquinone rich fraction from Nigella sativa and thymoquinone are cytotoxic towards colon and leukemic carcinoma cell lines. J. Med. Plants Res. 2011, 1996, 0875. [Google Scholar]

- Fröhlich, T.; Ndreshkjana, B.; Muenzner, J.K.; Reiter, C.; Hofmeister, E.; Mederer, S.; Fatfat, M.; El-Baba, C.; Gali-Muhtasib, H.; Schneider-Stock, R.; et al. Corrigendum: Synthesis of novel hybrids of thymoquinone and artemisinin with high activity and selectivity against colon cancer. ChemMedChem 2021, 16, 1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gali-Muhtasib, H.; Kuester, D.; Mawrin, C.; Bajbouj, K.; Diestel, A.; Ocker, M.; Habold, C.; Foltzer-Jourdainne, C.; Schoenfeld, P.; Peters, B.; et al. Thymoquinone triggers inactivation of the stress response pathway sensorCHEK1 and contributes to apoptosis in colorectal cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2008, 68, 5609–5618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokay, E. Determination of Cytotoxic effect and Expression analyses of Apoptotic and Autophagic related genes in Thymoquinone-treated Colon Cancer Cells. Sak. Univ. J. Sci. 2020, 24, 189–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gali-Muhtasib, H.; Diab-Assaf, M.; Boltze, C.; Al-Hmaira, J.; Hartig, R.; Roessner, A.; Schneider-Stock, R. Thymoquinone extracted from black seed triggers apoptotic cell death in human colorectal cancer cells via a p53-dependent mechanism. Int. J. Oncol. 2004, 25, 857–866. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Idris, S.; Refaat, B.; Almaimani, R.A.; Ahmed, H.G.; Ahmad, J.; Alhadrami, M.; El-Readi, M.; Elzubier, M.E.; Alaufi, H.A.A.; Al-Amin, B.; et al. Enhanced in vitro tumoricidal effects of 5-Fluorouracil, thymoquinone and active vitamin D3 triple therapy against colon cancer cells by attenuating the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway. Life Sci. 2022, 296, 120442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Shemi, A.; Kensara, O.; Mohamed, A.; Refaat, B.; Idris, S.; Ahmad, J. Thymoquinone subdues tumor growth and potentiates the chemopreventive effect of 5-fluorouracil on the early stages of colorectal carcinogenesis in rats. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 2016, 10, 2239–2253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohamed, A.M.; Refaat, B.A.; El-Shemi, A.G.; Kensara, O.A.; Ahmad, J.; Idris, S. Thymoquinone potentiates chemoprotective effect of Vitamin D3 against colon cancer: A pre-clinical finding. Am. J. Transl. Res. 2017, 9, 774–790. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chen, M.; Lee, N.; Hsu, H.; Ho, T.; Tu, C.; Hsieh, D.J.; Lin, Y.; Chen, L.; Kuo, W.; Huang, C. Thymoquinone induces caspase-independent, autophagic cell death in CPT-11-resistant LoVo colon cancer via mitochondrial dysfunction and activation of JNK and p38. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2015, 63, 1540–1546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kundu, J.; Choi, B.U.Y.; Jeong, C.; Kundu, J.K.; Chun, K. Thymoquinone induces apoptosis in human colon cancer HCT116 cells through inactivation of STAT3 by blocking JAK2- and Src-mediated phosphorylation of EGF receptor tyrosine kinase. Oncol. Rep. 2014, 32, 821–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Najjar, N.; Chatila, M.; Moukadem, H.; Vuorela, H.; Ocker, M.; Gandesiri, M.; Schneider-Stock, R.; Gali-Muhtasib, H. Reactive oxygen species mediate thymoquinone-induced apoptosis and activate ERK and JNK signaling. Apoptosis 2010, 15, 183–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jrah-Harzallah, H.; Ben-Hadj-Khalifa, S.; Almawi, W.Y.; Maaloul, A.; Houas, Z.; Mahjoub, T. Effect of thymoquinone on 1,2-dimethyl-hydrazine-induced oxidative stress during initiation and promotion of colon carcinogenesis. Eur. J. Cancer 2013, 49, 1127–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, Y.K.; Abdelrazek, H.M.A. Cancer: Thymoquinone antioxidant/pro-oxidant effect as potential anticancer remedy. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2019, 115, 108783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakamura, H.; Takada, K. Reactive oxygen species in cancer: Current findings and future directions. Cancer Sci. 2021, 112, 3945–3952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Bai, Y.; Yang, Y. Thymoquinone chemosensitizes colon cancer cells through inhibition of NF-κB. Oncol. Lett. 2016, 12, 2840–2845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Bitar, S.; Ballout, F.; Monzer, A.; Kanso, M.; Saheb, N.; Mukherji, D.; Faraj, W.; Tawil, A.; Doughan, S.; Hussein, M.; et al. Thymoquinone radiosensitizes human colorectal cancer cells in 2D and 3D culture models. Cancers 2022, 14, 1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kortüm, B.; Campregher, C.; Lang, M.; Khare, V.; Pinter, M.; Evstatiev, R.; Schmid, G.; Mittlböck, M.; Scharl, T.; Kucherlapati, M.H.; et al. Mesalazine and thymoquinone attenuate intestinal tumour development in Msh2loxP/loxPVillin-Cre mice. Gut 2015, 64, 1905–1912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, M.; Lee, N.; Hsu, H.; Ho, T.; Tu, C.; Chen, R.; Lin, Y.; Viswanadha, V.P.; Kuo, W.; Huang, C. Inhibition of NF-κB and metastasis in irinotecan (CPT-11)-resistant LoVo colon cancer cells by thymoquinone via JNK and p38. Environ. Toxicol. 2017, 32, 669–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, A.; Simon, M.C. Glutathione metabolism in cancer progression and treatment resistance. J. Cell Biol. 2018, 217, 2291–2298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Far, A.; Salaheldin, T.A.; Godugu, K.; Darwish, N.H.E.; Mousa, S.A. Thymoquinone and its nanoformulation attenuate colorectal and breast cancers and alleviate doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity. Nanomedicine 2021, 16, 1457–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Main Effects | Experimental Model | Dosage | Administration Mode and Duration | Dose-Dependent and/or Time-Dependent | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TQ reduced cellular proliferation TQ inhibited cell viability and colony formation with ionizing radiation (IR) TQ reduced mTOR, MEK, and NF-κB and stem cell markers CD133, β-catenin, and CD44 TQ induced G2/M cell cycle arrest TQ increased p53 expression and upregulated p21 expression TQ and IR reduced the sphere-forming ability of CRC cells | HCT116, HT29, and DLD1 cells | 3, 10, 30, 40, 60, 120 μm | Incubation (48 h) | Dose-dependent and Time-dependent | [36] |

| TQ decreased cell viability TQ inhibited the activation of NF-κB by reducing the phosphorylation of its p65 subunit TQ down-regulated VEGF, c-Myc, and Bcl-2 | HCT116 and COLO205 cells | 20, 40, 60 μM | Incubation (24 h) | Dose-dependent | [35] |

| TQ reduced tumor counts large ACFs TQ downregulated Wnt, β-catenin, NF-κB, COX-2, TGF-β1, HSP-90, and VEGF and upregulated tumor suppressor genes like DKK-1 and CDKN1-A TQ increased expression of smad4 and reduced iNOS | Male Wistar rats (200–250 g) | 35 mg/kg/day | Oral gavage (3 times/week) | Dose-dependent | [28] |

| TQ increased the number of cells in sub-G1 phase TQ reduced hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) levels while increasing total GSH TQ induced the expression of BAX, Cytochrome C, and caspase-3 TQ reduced PTEN and inhibited PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway | SW480 cells | 75 μM | Incubation (12 h) | Dose-dependent | [26] |

| TQ reduced cell viability of cells TQ inhibited the expression of PI3K, Akt, p-GSK3β, β-catenin and COX-2 TQ inhibited the nuclear translocation of β-catenin TQ reduced cell migration | LoVo cells | 2.5, 5, 7.5, 10, 20 μM | Incubation (24 h) | Dose-dependent | [13] |

| TQ reduced the total protein levels and phosphorylation of IKKα/β and NF-κB TQ decrease in protein levels of EMT markers Snail, Twist, MMP-2, and MMP-9 TQ reduced the cell migratory abilities of the cells | LoVo cells | 2, 4, 6, 8 μM | Incubation (24 h) | Dose-dependent | [38] |

| TQ treatment reduced the viability of cells TQ treatment induced the cleavage of caspase-9, caspase-7, caspase-3, and PARP TQ treatment attenuated STAT3 activation and expression of its target gene products TQ inhibited STAT3 activation by blocking the phosphorylation of EGFR (Y1173), JAK2 and Src kinases | HCT-116 cells | 10, 25, 50 μM | Incubation (24, 48, 72 h) | Dose-dependent and Time-dependent | [30] |

| TQ treatment caused early and dramatic increase in the amount of H2A.X protein TQ treatment upregulated the production of p53+/+ TQ treatment down regulated the production of CHEK1 TQ lowered CHEK1 expression and induced apoptosis in a p53-dependent manner | HCT116 cells Male NMRI mice (4–6 weeks) | 60 μM 20 mg/kg | Incubation (24, 48, 72 h) Intraperitoneal injection (3 times/week) | Dose-dependent and Time-dependent | [15] |

| TQ elevated the total cell death index TQ reduced cytochrome c and cleaved caspase 3 TQ induced autophagic cell death via increasing MOMP and activating JNK and p38 TQ treatment increased the cellular expression of LC3 | Lovo cells | 2, 4, 6, 8 μM | Incubation (24 h) | Dose-dependent | [29] |

| TQ treatment reduces the gross tumour cell count TQ attenuated CRC initiation and enhanced the tumoricidal and chemopreventive efficacy of 5-FU Combined TQ and 5-FU treatment synergistically upregulated the expression of DKK-1, CDNK-1A, TGF-β1, and Smad4 Combined TQ and 5-FU therapy repressed the expression of β-catenin and iNOS | Adult Male Wistar rats (230 ± 20 g) | 35 mg/kg/day | Orally by gastric gavage (3 times/week) | Dose-dependent | [27] |

| TQ increased the percentage of cells in the pre-G1 phase of the cell cycle TQ increased apoptosis, increasing caspase-3 and caspase-7 activity TQ activated the ERK and JNK pathways | HCT116, Caco-2, LoVo, and DLD-1 cells | 20, 40, 60, 80, 100 μM | Incubation (24 and 48 h) | Dose-dependent and Time-dependent | [31] |

| TQ activated GSK-3β, inducing membranous localization of β-catenin and reduced nuclear c-myc expression TQ reduced the number of colonic polyps and their growth and induced apoptosis in polyps TQ reduces c-myc expression in the polyps TQ translocates β–catenin to the membrane in polyps | RKO cells Male and Female ApcMin mice (4–6 weeks old) | 10, 15, 30, 60, 90 μM 375 mg/kg | Incubation (24 h) Fed with chow (12 weeks) | Dose-dependent | [12] |

| TQ decreased the concentration of GSH in its reduced form | Caco2 cells | 389.60 µg/mL | Incubation (24 h) | Dose-dependent | [17] |

| TQ caused a significant decrease in cell viability TQ induced an increase in LDH release TQ increased the percentage of apoptotic cells | HCT116 and HT-29 cells | 12.5, 25, 50, 100 μg/mL | Incubation (24 and 48 h) | Dose-dependent | [20] |

| TQ reduced cell viability TQ decreased cell proliferation rate TQ treatment reduces glycolytic metabolism/glucose fermentation rate (Warburg effect) TQ inhibited HK2 expression and PI3K-AKT activation | HCT116 and SW480 cells | 20.53 and 21.71 µM | Incubation (4 days) | Dose-dependent and Time-dependent | [18] |

| TQ led to PARP cleavage | HCT116 and HT-29 cells | 1, 2.5, 5 μM | Incubation (24 h) | Dose-dependent | [22] |

| TQ reduces cell viability TQ significantly decreased the sphere formation ability TQ decreased expression CD44, EpCAM, and Ki67 TQ inhibited cell migration ability by upregulating E-cadherin and downregulating mesenchymal markers TQ caused an upregulation of p53, p21, γ-H2AX TQ inhibited tumor growth | HCT116 cells Male NOD-SCID and NOG mice (6–8 weeks old) | 1, 3, 5, 40, 60, 100 μM 20 mg/kg | Incubation (24, 48, 72 h) Intraperitoneal injection (3 times/week for 21 days) | Dose-dependent and Time-dependent Time-dependent | [16] |

| TQ significantly decreased cell viability | HCT-116 cells | 60 and 68 μM | Incubation (24 h) | Dose-dependent | [14] |

| TQ reduced cell growth and improved replication fidelity TQ reduced small intestinal tumor incidence TQ reduced the number of small and medium-sized intestinal tumors TQ decreased mutation rates | HCT116 cells Male and Female Msh2loxP/loxP Villin-Cre mice (4–6 weeks) | 1.25 and 2.50 μM 37.5 and 375 mg/kg | Incubation (7 days) Fed through chow (43 weeks) | Dose-dependent Dose-dependent | [37] |

| TQ significantly increased cell mortality rate TQ treatment decreased cell proliferation TQ treatment induced morphological changes in cells by inducing p53 overexpression and caspase 3/Mcl-1 downregulation | HCT116 cells | 20 and 60 μM | Incubation (20 h) | Dose-dependent | [19] |

| TQ inhibited cell proliferation TQ induced significant alterations in cellular morphology TQ induced cell cycle arrest at G1/S phase TQ upregulated p53 mRNA expression and decreased Bcl-2 | HCT116 cells | 10–100 μM | Incubation (12, 24, 48 h) | Dose-dependent and Time-dependent | [25] |

| TQ decreased cellular viability TQ reduced the invasive abilities of the cells TQ downregulated the expression of ATG-12, ATG-7, and LC3-II TQ downregulated the expression of Bcl-2 and Bcl-X and upregulated Bax | HT-29 cells | 19, 18, 39, 75, 150 µM | Incubation (6, 24, 48 h) | Dose-dependent and Time-dependent | [24] |

| TQ reduced cell viability | HT-29 cells | 3, 5, 8 μg/m | Incubation (24 and 72 h) | Dose-dependent and Time-dependent | [21] |

| TQ treatment reduced the number and sizes of aberrant crypt foci (ACF) TQ reduced cell invasion potential of cells. TQ displayed increased apoptosis, loss of intercellular adhesion, and sponge-like growth pattern TQ treatment significantly reduced tumor multiplicity and size | C26 cells Female BALB/c mice (20–24 g, 9 weeks) | 20, 40, 60 μM 5, 10, 20, 30 mg/kg | Incubation (24 h) Intraperitoneal injection (daily for 20 days) | Dose-dependent Dose-dependent | [23] |

| TQ reduced tumor incidence, multiplicity, and size TQ attenuated oxidative stress by reducing ROS and restoring antioxidant enzyme levels of GPx, CAT, SOD, and GSH | Adult Male Wistar rats | 5 mg/kg | Intraperitoneal injection (once every 10 or 20 weeks) | Time-dependent | [32] |

| TQ increased Bax and decreased Bcl-2, inducing apoptosis TQ inhibited expression and activity of NF-κB and STAT3 | HCT116 cells | 30 μM | Incubation (24 h) | - | [40] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Majdalawieh, A.F.; Al-Samaraie, S.; Terro, T.M. Molecular Mechanisms and Signaling Pathways Underlying the Therapeutic Potential of Thymoquinone Against Colorectal Cancer. Molecules 2024, 29, 5907. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules29245907

Majdalawieh AF, Al-Samaraie S, Terro TM. Molecular Mechanisms and Signaling Pathways Underlying the Therapeutic Potential of Thymoquinone Against Colorectal Cancer. Molecules. 2024; 29(24):5907. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules29245907

Chicago/Turabian StyleMajdalawieh, Amin F., Saud Al-Samaraie, and Tala M. Terro. 2024. "Molecular Mechanisms and Signaling Pathways Underlying the Therapeutic Potential of Thymoquinone Against Colorectal Cancer" Molecules 29, no. 24: 5907. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules29245907

APA StyleMajdalawieh, A. F., Al-Samaraie, S., & Terro, T. M. (2024). Molecular Mechanisms and Signaling Pathways Underlying the Therapeutic Potential of Thymoquinone Against Colorectal Cancer. Molecules, 29(24), 5907. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules29245907