Abstract

A chemical investigation of Anthriscus sylvestris roots led to the isolation and characterization of two new nitrogen-containing phenylpropanoids (1–2) and two new phenol glycosides (8–9), along with fifteen known analogues. Structure elucidation was based on HRESIMS, 1D and 2D NMR spectroscopy, and electronic circular dichroism (ECD). In addition, compounds 3, 6, 9–10, 12, and 17 exhibited inhibitory effects against the abnormal proliferation of pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells with IC50 values ranging from 10.7 ± 0.6 to 57.1 ± 1.1 μM.

1. Introduction

Anthriscus sylvestris L. Hoffm. (Umbelliferae), known as wild chervil, is a common perennial plant in Europe, North America, and Asia [1,2]. Its dried root has been used as an anti-pyretic, analgesic, diuretic, and anti-tussive agent in traditional Chinese medicine [3]. The major classes of phytochemicals of A. sylvestris include lignans, phenylpropanoids, and flavonoids [4,5]. Pharmacological investigations have demonstrated that this plant possesses certain biological properties such as anti-tumor, anti-proliferative, anti-asthmatic, and anti-inflammatory [6,7,8].

Pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) is a chronic, progressive disease of the pulmonary circulation characterized by vascular remodeling [9]. Pulmonary vascular remodeling involves a variety of cells, including vascular endothelial cells, pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells (PASMCs), and multiple inflammatory cells [10,11]. The previous study demonstrated that diarylpentanoids and phenylpropanoids isolated from the roots of A. sylvestris could inhibit the abnormal proliferation of PASMCs induced by hypoxia [12], which attracted our interest to search for more natural products with anti-proliferative effects from this plant. In this study, two new nitrogen-containing phenylpropanoids (1–2), and two new phenol glycosides (8–9), along with fifteen known analogues, were isolated from the roots of A. sylvestris, and their anti-proliferative effects against the abnormal proliferation of pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells were evaluated.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Structure Characterization

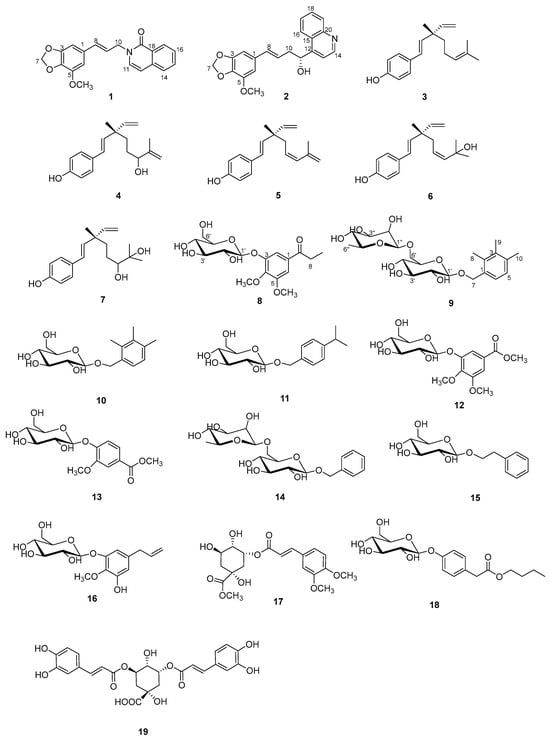

The chemical investigations on the extract of the roots of A. sylvestris resulted in the characterization of compounds (1–19) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The chemical structures of compounds 1–19.

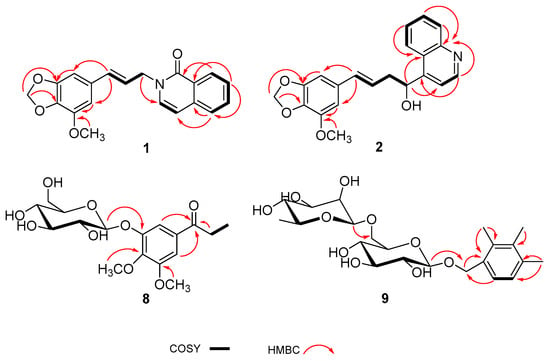

Compound 1, a white amorphous powder, was assigned a molecular formula of C20H17NO4 due to the HRESIMS ion at m/z 336.1230 [M + Na]+ (calcd. 336.1232). The 1D NMR spectrum of 1 exhibited the signals of a carbonyl carbon [δC 180.3 (C-19)], a tetrasubstituted aromatic ring [δH 6.62 (1H, s, H-2), 6.56 (1H, s, H-6); δC 150.8 (C-3), 145.0 (C-5), 136.8 (C-4), 132.3 (C-1), 108.8 (C-6), 100.9 (C-2)], a disubstituted aromatic ring [δH 8.35 (1H, dd, J = 7.8, 1.3 Hz, H-15), 7.80 (2H, overlap, H-14,17), 7.47 (1H, t, J = 7.8 Hz, H-16); δC 141.6 (C-13), 133.9 (C-14), 127.8 (C-18), 127.1 (C-15), 125.4 (C-16), 118.2 (C-17)], two olefinic groups [δH 8.11 (1H, d, J = 7.6 Hz, H-11), 6.47 (1H, d, J = 15.9 Hz, H-8), 6.36 (1H, d, J = 7.6 Hz, H-12), 6.29 (1H, dt, J = 15.9, 5.8 Hz, H-9); δC 146.4 (C-11), 134.6 (C-8), 122.6 (C-9), 110.2 (C-12)], an oxygenated methylene group [δH 5.88 (2H, s, H-7); δC 102.7 (C-7)], a nitrogenated methylene group [δH 5.07 (2H, d, J = 5.8 Hz, H-10); δC 55.8 (C-10)], and a methoxy group [δH 3.82 (3H, s, OCH3-5); δC 57.2 (OCH3-5)]. The 1D NMR data of compound 1 were very similar to those of 2-[2-(1,3-benzodioxol-5-yl)ethyl]-6-methoxy-1(2H)-isoquinolinone [13]. Major discrepancies were concentrated on the absence of the methoxy group at C-16 and the presence of the methoxy group at C-5, and the Δ8(9) double bond linked with a methylene carbon, which was confirmed by the 1H-1H COSY correlations of H-9 with H-8 and H-10 and the HMBC crosspeaks from H-8 to C-2 and C-6, from H-10 to C-11, and from the hydrogens of the methoxy group (δH 3.82) to C-5 (Figure 2). Based on these data, the structure of compound 1 was identified and named as anthriscusin O.

Figure 2.

The key HMBC and 1H-1H COSY correlations of compounds 1–2 and 8–9.

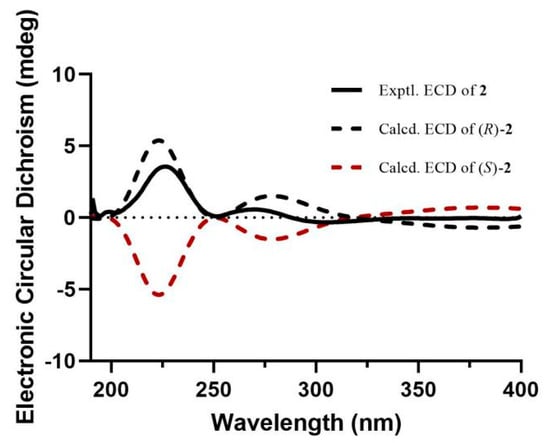

Compound 2 was obtained as a colorless solid. Its molecular formula, C21H19NO4, was established by the HRESIMS ion at m/z 372.1205 [M + Na]+ (calcd. for 372.1206). The 1H and 13C NMR data (Table 1) of 2 revealed the presence of a tetrasubstituted aromatic ring [δH 6.52 (1H, s, H-2), 6.47 (1H, s, H-6); δC 150.6 (C-3), 144.9 (C-5), 135.9 (C-4), 133.9 (C-1), 108.0 (C-6), 100.5 (C-2)], a quinoline unit [δH 8.82 (1H, d, J = 4.6 Hz, H-14), 8.20 (1H, d, J = 8.4 Hz, H-16), 8.05 (1H, d, J = 8.4 Hz, H-19), 7.78 (1H, t, J = 8.4 Hz, H-17), 7.70 (1H, d, J = 4.6 Hz, H-13), 7.64 (1H, t, J = 8.4 Hz, H-18); δC 153.3 (C-12), 151.0 (C-14), 148.7 (C-20), 130.6 (C-17), 129.9 (C-19), 127.9 (C-18), 127.0 (C-15), 124.7 (C-16), 119.1 (C-13)], an olefinic group [δH 6.27 (1H, d, J = 15.8 Hz, H-8), 6.17 (1H, dt, J = 15.8, 5.8 Hz, H-9); δC 133.6 (C-8), 125.6 (C-9)], an oxygenated methine group [δH 5.60 (1H, dd, J = 7.2, 5.8 Hz, H-11); δC 70.4 (C-11)], an oxygenated methylene group [δH 5.87 (2H, s, H-7); δC 102.5 (C-7)], a methylene group [δH 2.76 (1H, m, H-10a), 2.68 (1H, dd, J = 14.3, 7.2 Hz, H-10b); δC 43.0 (C-10)], and a methoxy group [δH 3.82 (3H, s, OCH3-5); δC 57.2 (OCH3-5)]. The 1H and 13C NMR data of 2 were similar to those of (2E)-3-(1,3-benzodioxol-5-yl)-2-propen-1-yl]benzenemethanol [14], except for the absence of the aromatic group and the presence of a quinoline unit at C-11 and an additional methoxy group at C-5, which was deduced by the HMBC correlations from H-11 to C-13 and C-15, and from the hydrogens of the methoxy group (δH 3.82) to C-5 (Figure 2). To define the absolute configuration, the ECD calculation was performed at the B3LYP/6-311G(d) level using the TDDFT method. Furthermore, the agreement of the Cotton effects of the calculated ECD spectrum of (R)-2 with the experimental ECD spectrum of 2 allowed the absolute configuration of 2 to be assigned as (R) (Figure 3). Thus, the structure of 2 was elucidated as shown and named as anthriscusin P.

Table 1.

1H (500 MHz) and 13C (125 MHz) NMR spectroscopic and HMBC data of compounds 1–2 in CD3OD.

Figure 3.

Experimental and calculated ECD spectra of compound 2.

Compound 8 was acquired as a white amorphous powder with a molecular formula of C17H24O9, as determined by its HRESIMS and 13C NMR data. The 1H and 13C NMR data (Table 2) of 8 were similar to those of 12 [15], except for the replacement of the methoxy group at C-8 by the ethyl group in 8, which was corroborated by the HMBC correlations (Figure S31, Supplementary Materials) of H-8 with δC 201.9 (C-7) and 8.7 (C-9). Additionally, the hexose moiety was determined as d-glucose through the chiral-phase HPLC analysis of a monosaccharide produced by the hydrolysis of compound 8 (Figure S63, Supplementary Materials). The anomeric proton (δH 4.95) of hexose moiety had a large coupling constant (J = 7.4 Hz), indicating a β-configuration. Thus, the structure of 8 was defined as shown and named as 1-(3-β-d-glucopyranosyloxy)-4,5-dimethoxyphenyl)propan-1-one.

Table 2.

1H (500 MHz) and 13C (125 MHz) NMR spectroscopic and HMBC data of compounds 8–9 in CD3OD.

Compound 9 was acquired as colorless crystals. According to the HRESIMS at m/z 481.2053 [M + Na]+, its molecular formula was inferred as C22H34O10. The 1H NMR spectrum showed signals for two aromatic protons [δH 7.06 (1H, d, J = 7.7 Hz, H-6), 6.94 (1H, d, J = 7.7 Hz, H-5)], an oxygenated methylene group [δH 4.89 (1H, overlap, H-7a), 4.58 (1H, d, J = 11.2 Hz, H-7b)], three methyl groups [δH 2.28 (3H, s, H-8), 2.25 (1H, s, H-10), 2.18 (1H, s, H-9)], and two anomeric protons [δH 4.79 (1H, d, J = 1.2 Hz, H-1′′), 4.25 (1H, d, J = 7.8 Hz, H-1′)]. The 13C NMR spectrum exhibited resonances for six aromatic carbons [δC 137.5 (C-4), 137.0 (C-2), 136.3 (C-3), 133.8 (C-1), 128.5 (C-6), 127.9 (C-5)], an oxygenated methylene carbon [δC 70.9 (C-7)], and three methyl groups [δC 20.9 (C-10), 15.7 (C-8, 9)]. Additionally, two anomeric carbons (δC 102.6 and 102.2), as well as ten carbon signals [δC 78.1 (C-3′), 76.9 (C-5′), 75.0 (C-2′), 74.0 (C-4′′), 72.4 (C-3′′), 72.2 (C-2′′), 71.4 (C-4′), 69.8 (C-6′), 68.1 (C-5′′), 18.1 (C-6′′)] indicated the occurrence of two sugar substituents. The hexose moieties were identified as d-glucose and l-rhamnose by chiral-phase HPLC analysis (Figure S64, Supplementary Materials). Moreover, the anomeric proton (δH 4.25) of d-glucose had a large coupling constant (J = 7.8 Hz), and the anomeric proton (δH 4.79) of l-rhamnose had a small coupling constant (J = 1.2 Hz), which suggested the configurations of the anomeric carbons of d-glucose and l-rhamnose were β and α, respectively. In the HMBC spectrum, the anomeric proton of the d-glucose unit showed a correlation with C-7, and the anomeric proton of the l-rhamnose unit was correlated with the C-6′ of d-glucose unit. These NMR data mentioned above were similar to those of compound 14 [16], except for the presence of three methyl groups. The three methyl groups were respectively located at C-2, C-3, and C-4, which was determined by the key HMBC correlations from the methyl protons at δH 2.28 to C-1, C2, and C-3, from the methyl protons at δH 2.18 to C-3 and C-4, and from the methyl protons at δH 2.25 to C-4 and C-5 (Figure 2). Based on these data, the structure of compound 9 was identified and named as 2,3,4-trimethylbenzylalcohol-α-l-rhamnopyranosyl-(6→1)-β-d-glucopyranoside.

Fifteen known compounds were identified as bakuchiol (3) [17], 1,3-hydroxybakuchiol (4) [17], 15-demetyl-12,13-dihydro-13-ketobakuchiol (5) [17], 3,2-hydroxybakuchiol (6) [17], 12,13-diolbakuchiol (7) [18], 2,3,4-trimethylbenzylalcohol-O-β-d-glucopyranoside acid (10) [19], p-cymen-7-yloxy-β-d-glucopyranoside (11) [20], methyl di-O-methyl-O-glucosylgallate (12) [15], methyl 4-(β-d-glucopyranosyloxy)-3-methoxybenzoate (13) [21], benzyl α-l-rhamnopyranosyl-(1→6)-β-d-glucopyranoside (14) [16], 2-phenylethyl-β-d-glucopyranoside (15) [22], 3,5-dihydroxyestragole 3-O-β-d-glucopyranoside (16) [23], 5-O-feruloylquinic acid methyl ester (17) [24], butyl(4-β-d-glucopyranosyloxy-phenyl)acetate (18) [25], and 3,5-dicaffeoylquinic acid (19) [26].

2.2. Biological Activity

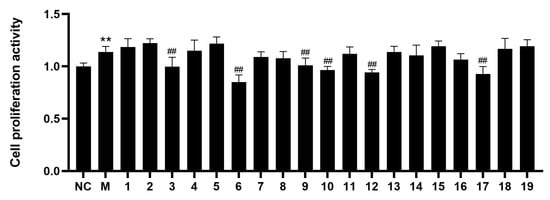

The isolates 1–19 were screened for their inhibitory effects on PASMCs’ abnormal proliferation induced by hypoxia in vitro. As shown in Figure 4, compared with the normal (NC) group, the proliferation rate of PASMCs in the model (M) group was significantly increased (p < 0.01). Compared with the M group, the proliferation rates of the compounds 3, 6, 9–10, 12, and 17 groups were significantly decreased (p < 0.01), which indicated that compounds 3, 6, 9–10, 12, and 17 can significantly inhibit the abnormal proliferation of PASMCs at 5 μM. Then, these cells were treated with the compounds (3, 6, 9–10, 12, and 17) with different concentrations (1, 2.5, 5, 10, 20, 50, and 100 μM). Compounds 3, 6, 9–10, 12, and 17 suppressed the abnormal proliferation of PASMCs, with IC50 values of 56.3 ± 0.5, 10.7 ± 0.65, 57.1 ± 1.1, 44.0 ± 0.75, 41.5 ± 0.87, and 35.3 ± 0.42 μM, respectively. Notably, the comparison of compounds 8 and 12 showed that the methoxy fragment connected to C-8 may be responsible for the inhibition. Additionally, compounds 9 and 10 exhibited an inhibitory effect in contrast to compounds 14 and 15, which might be attributed to the presence of a 2,3,4-trimethylphenyl group.

Figure 4.

The inhibitory effects of compounds 1–19 were tested in hypoxia-stimulated PASMCs by MTT assay. (Compared with NC group, ** p < 0.01; Compared with M group, ## p < 0.01.)

Pharmacological studies have shown that deoxypodophyllotoxin isolated from A. sylvestris possesses antitumor, antibacterial, and antiviral activities [7,8,27,28], which has led to the pharmacological effects of A. sylvestris being mainly focused on antitumor effects, with less research and attention paid to other pharmacological effects. In this study, the inhibitory effects of compounds isolated from A. sylvestris on the hypoxia-induced cell proliferation of PASMCs were investigated for the first time. The preliminary results of this experiment have an important potential value for future development and research on A. sylvestris.

3. Experimental

3.1. General Experimental Procedures

MS spectra were obtained using a Bruker maXis HD mass spectrometer (Bruker, Bremen, Germany). Optical rotations were measured on a Rudolph AP-Ⅳ polarimeter (Rudolph, Hackettstown, NJ, USA). IR spectra were recorded on a Thermo Nicolet IS 10 spectrometer (Thermo, Waltham, MA, USA). UV spectra were recorded on a ThermoEVO 300 spectrometer (Thermo, Waltham, MA, USA). NMR spectra were acquired using a Bruker Avance III 500 spectrometer (Bruker, Bremen, Germany). ECD spectra were recorded on an Applied Photophysics Chirascan qCD spectropolarimeter (AppliedPhotophysics, Leatherhead, Surrey, UK). Semipreparative HPLC separations were conducted on a Saipuruisi LC 52 HPLC system with a UV/vis 50 detector (Saipuruisi, Beijing, China) and a YMC Pack ODS A column (20 × 250 mm, 5 μm; YMC, Kyoto, Japan). Monosaccharide elucidation was conducted on a Waters 2695 separation module equipped with an evaporative light-scattering detector (ELSD) (Waters, Milford, MA, USA) using a CHIRALPAK AD-H column (4.6 × 250 mm) (Daicel Chiral Technologies Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China). Column chromatography was performed using the Toyopearl HW-40C (TOSOH Corp, Tokyo, Japan), Sephadex LH-20 (40–70 mm, Amersham Pharmacia Biotech AB, Uppsala, Sweden), and silica gel (200–300 mesh, Marine Chemical Industry, Qingdao, China). The chemical reagents were supplied by the Tianjin Fuyu Fine Chemical Industry, Tianjin, China.

3.2. Plant Material

The dried roots of A. sylvestris were collected in November 2021 from Leshan city, Sichuan province, China, and identified by Professor Chengming Dong of Henan University of Chinese Medicine. A voucher specimen (No. 20211116A) was deposited at the Department of Natural Medicinal Chemistry, Henan University of Chinese Medicine, Zhengzhou, China.

3.3. Extraction and Isolation

The chopped dried roots (48.0 kg) were extracted with 70% aqueous acetone (smashed tissue extraction). The extract (15 kg) was suspended in water and sequentially partitioned with petroleum ether, EtOAc, and n-BuOH for fifteen times, respectively.

The EtOAc fraction (100.0 g) was separated by silica gel column chromatography (CC) eluted with a petroleum ether-EtOAc (100:0−0:100) gradient system and an EtOAc-CH3OH (100:0−0:100) gradient system and yielded seven subfractions (E1−E7). Subfraction E6 (6.5 g) was chromatographed using silica gel CC eluted with a CH2Cl2-CH3OH (200:1–1:1) gradient system to give seven subfractions (E6-1–E6-7). Subfraction E6-2 (510.0 mg) was separated by the Toyopearl HW-40C CC (CH3OH-H2O 70:30) to obtain three subfractions (E6-2-1–E6-2-3). Subfraction E6-2-2 (200.0 mg) was purified by semipreparative HPLC (CH3OH-H2O 84:16) to produce compounds 4 (5.3 mg), 6 (3.1 mg), and 7 (8.0 mg). Subfraction E6-3 (400.0 mg) was separated by the Sephadex LH-20 (CH3OH-H2O 70:30) to obtain three subfractions (E6-3-1–E6-3-3). Subfraction E6-3-1 (49.0 mg) was purified by semipreparative HPLC (CH3OH-H2O 89:11) to yield compounds 3 (3.9 mg) and 5 (3.5 mg). Subfraction E6-3-3 (88.0 mg) was purified by semipreparative HPLC (CH3OH-H2O 70:30) to yield compounds 1 (7.5 mg) and 2 (5.3 mg). Subfraction E6-4 (280.0 mg) was purified by semipreparative HPLC (CH3OH-H2O 52:48) to yield compounds 10 (20.4 mg) and 16 (5.0 mg). Subfraction E6-5 (1.9 g) was subjected to silica gel CC eluted with a petroleum EtOAc-CH3OH gradient system (80:1–1:1) to give five subfractions (E-6-5-1–E6-5-5). Subfraction E6-5-3 (550.0 mg) was separated by Toyopearl HW-40C CC (CH3OH-H2O 50:50) to obtain four subfractions (E6-5-3-1–E6-5-3-4). Then subfraction E6-5-3-2 (89.9 mg) was purified by semipreparative HPLC (CH3OH-H2O 60:40) to produce compounds 8 (5.0 mg) and 12 (10.3 mg). Subfraction E6-5-4 (100.0 mg) was purified by semipreparative HPLC (CH3OH-H2O 52:48) to yield compound 9 (13.0 mg).

The n-BuOH fraction (160.0 g) was separated by Diaion HP-20 eluted with a petroleum ethanol-H2O (0:100−95:5) gradient to produce seven subfractions (N1−N7). Subfraction N3 (10.5 g) was subjected to ODS gel CC (CH3OH-H2O 10:90−50:50) to obtain five subfractions (N3-1–N3-5). Subfraction N3-3 (2.0 g) was chromatographed with the Sephadex LH-20 CC (MeOH-H2O 30:70) to obtain five subfractions (N3-3-1−N3-3-5). Then, subfraction N3-3-2 (480.9 mg) was subjected to silica gel CC eluted with a petroleum EtOAc-CH3OH gradient system (50:1–1:1) to give three subfractions (N3-3-2-1–N3-3-2-3). Subfraction N3-3-2-2 (90.0 mg) was purified by semipreparative HPLC (CH3OH-H2O 55:45) to yield compounds 13 (3.1 mg), 15 (2.5 mg), and 17 (5.1 mg). Subfraction N3-3-2-3 (120.0 mg) was purified by semipreparative HPLC (CH3OH-H2O 52:48) to yield compounds 11 (3.5 mg) and 18 (4.8 mg). Subfraction N3-4 (1.5 g) was subjected to the Toyopearl HW-40C CC (CH3OH-H2O 80:20) to obtain four subfractions (N3-4-1–N3-4-4). Then subfraction N3-4-3 (530.9 mg) was subjected to silica gel CC eluted with a petroleum EtOAc-CH3OH gradient system (50:1–1:1) to give four subfractions (N3-4-3-1–N3-4-3-4). Subfraction N3-4-3-3 (100.0 mg) was purified by semipreparative HPLC (CH3OH-H2O 55:45) to yield compounds 14 (7.1 mg) and 19 (16.0 mg).

Anthriscusin O (1): white amorphous powder; UV (CH3OH) λmax: 213, 280, 322, and 335 nm; IR (iTR) νmax: 2922, 1621, and 1025 cm−1; HRESIMS m/z 336.1230 [M + Na]+ (calcd. for C20H17NO4Na, 336.1232); 1H and 13C NMR data, see Table 1.

Anthriscusin P (2): white amorphous powder; +17.1 (c 0.04, CH3OH); UV (CH3OH) λmax: 224 and 278 nm; IR (iTR) νmax: 3327, 2931, 1625, 1509, and 1135 cm−1; ECD (CH3OH) λmax (Δε): 226 (+3.5) and 267 (+0.5); HRESIMS m/z 372.1205 [M + Na]+ (calcd. for C21H19NO4Na, 372.1206); 1H and 13C NMR data, see Table 1.

1-(3-β-d-glucopyranosyloxy)-4,5-dimethoxyphenyl)propan-1-one (8): white amorphous powder; UV (CH3OH) λmax: 202 nm; IR (iTR) νmax: 3354, 2926, 1454, and 1041 cm−1; HRESIMS m/z 395.1318 [M + Na]+ (calcd. for C17H24O9Na, 395.1312); 1H and 13C NMR data, see Table 2.

2,3,4-trimethylbenzylalcohol-α-l-rhamnopyranosyl-(6→1)-β-d-glucopyranoside (9): white amorphous powder; UV (CH3OH) λmax: 217 and 272 nm; IR (iTR) νmax: 3396, 2938, 1675, 1589, 1419, and 1075 cm−1; HRESIMS m/z 481.2053 [M + Na]+ (calcd. for C22H34O10Na, 481.2044); 1H and 13C NMR data, see Table 2.

3.4. Computational Analysis

The conformations of 2 were analyzed by GMMX software (6.0) using the MMFF94 force field. The conformers were optimized with density functional theory (DFT) at the B3LYP/6-31G using the Gaussian 2016 package. The ECD calculations of conformers with Boltzmann distributions over 1% were further calculated by the TDDFT method at the B3LYP/6-311G (d) level in CH3OH. The ECD spectra were simulated by the SpecDis 1.71 software [29].

3.5. MTT Assay

Briefly, the PASMCs were seeded in 96-well plates at 2 × 104 cells/well at 37 °C in an atmosphere of 5% CO2. The cells were divided into the normal group (NC), model group (M), and treatment groups (isolated compounds). Then, the MTT assay was performed as previously described [12]. All data were analyzed by SPSS software version 26.0 (IBM, New York, NY, USA) and presented as the mean ± standard deviation. Concentration-response analysis was performed to determine the compound concentrations required to inhibit the growth of cells by 50% (IC50) using GraphPad Prism 8.02 software.

4. Conclusions

Four new compounds (1–2, 8, and 9), together with fifteen known analogs were isolated from the roots of A. sylvestris. All compounds were isolated from the plant for the first time, which greatly enriches the chemical content of this plant. In preliminary in vitro bioassays, the results showed that 3, 6, 9–10, 12, and 17 exhibited anti-proliferation effects on hypoxia-induced PASMCs’ cell proliferation, suggesting that they may further act as potential lead molecules for the development of therapeutic agents for PAH. Then, we will discover more bioactive compounds from A. sylvestris and carry out further research on the mechanism with potential compounds for the treatment of PAH.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/molecules29112547/s1, Figures S1–S16: 1D/2D NMR, HR-ESIMS, IR, and UV spectra of compounds 1–2, Figures S17–S26: 1D NMR spectra of compounds 3–7; Figures S27–S42: 1D/2D NMR, HR-ESIMS, IR, and UV spectra of compounds 8–9; Figures S43–S61: 1D NMR spectra of compounds 10–19; Figures S62–S64: Chiral-HPLC profile from acid hydrolysis of compounds 8 and 9 compared to authentic standard.

Author Contributions

Original draft preparation, Y.L.; performed the experiments, Y.L., Y.Z., Y.N., L.C., X.C., X.M. and X.L.; data analysis, Y.L. and Y.C.; review and editing, X.Z. and W.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Central Government Guide Local Science and Technology Development Funds ([2016]149), Henan Province High-level Personnel Special Support (ZYQR201810080).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available in the Supplementary Materials.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Bos, R.; Koulman, A.; Woerdenbag, H.J.; Quax, W.J.; Pras, N. Volatile components from Anthriscus sylvestris (L.) Hoffm. J. Chromatogr. A 2002, 966, 233–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeong, G.S.; Kwon, O.K.; Park, B.Y.; Oh, S.R.; Ahn, K.S.; Chang, M.J.; Oh, W.K.; Kim, J.C.; Min, B.S.; Kim, Y.C. Lignans and coumarins from the roots of Anthriscus sylvestris and their increase of caspase-3 activity in HL-60 cells. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2007, 30, 1340–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kozawa, M.; Baba, K.; Matsuyama, Y.; Kido, T.; Sakai, M.; Takemoto, T. Components of the root of Anthriscus sylvestris Hoffm. II. Insecticidal Activity. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1982, 30, 2885–2888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, C.; Lei, B.; Ning, N.; Fan, J.; Zhang, X.; Ma, C.; Jiang, H. A new phenylpropanoid ester from the roots of Anthriscus sylvestris and its chemotaxonomic significance. Biochem. Sys. Ecol. 2020, 93, 104144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orčić, D.; Berežni, S.; Škorić, D.D.; Mimica Dukić, N. Comprehensive study of Anthriscus sylvestris lignans. Phytochemistry 2021, 192, 112958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guerrero, E.; Abad, A.; Montenegro, G.; Del-Olmo, E.; López-Pérez, J.L.; San Feliciano, A. Analgesic and anti-inflammatory activity of podophyllotoxin derivatives. Pharm. Biol. 2013, 51, 566–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suh, S.J.; Kim, J.R.; Jin, U.H.; Choi, H.S.; Chang, Y.C.; Lee, Y.C.; Kim, S.H.; Lee, I.S.; Moon, T.C.; Chang, H.W.; et al. Deoxypodophyllotoxin, flavolignan, from Anthriscus sylvestris Hoffm. inhibits migration and MMP-9 via MAPK pathways in TNF-alpha-induced HASMC. Vascul. Pharmacol. 2009, 51, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, C.; Lee, E.; Jin, M.; Yook, J.; Quan, Z.; Ha, K.; Moon, T.; Kim, M.; Kim, K.; Lee, S. Deoxypodophyllotoxin (DPT) inhibits eosinophil recruitment into the airway and Th2 cytokine expression in an OVA-induced lung inflammation. Planta Med. 2006, 72, 786–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Humbert, M.; Sitbon, O.; Simonneau, G. Treatment of pulmonary arterial hypertension. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004, 351, 1425–1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.Y.; Ba, H.X.; Li, Y.; Tang, S.Y.; Luo, Z.Q.; Li, X.H. Regulatory effects of prohibitin 1 on proliferation and apoptosis of pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells in monocrotaline-induced PAH rats. Life Sci. 2020, 250, 117548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, B.; Peng, X.; Su, D.; Liu, D.; Huang, Y.; Huang, Y.; Pang, Y. Effects of YM155 on the proliferation and apoptosis of pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells in a rat model of high pulmonary blood flow-induced pulmonary arterial hypertension. Clin. Exp. Hypertens. 2022, 44, 470–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.L.; Cao, Y.G.; Niu, Y.; Zheng, Y.J.; Chen, X.; Ren, Y.J.; Fan, X.L.; Li, X.D.; Ma, X.Y.; Zheng, X.K.; et al. Diarylpentanoids and phenylpropanoids from the roots of Anthriscus sylvestris (L.) Hoffm. Phytochemistry 2023, 216, 113865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Huang, T.; Song, Y.; Qi, Y.; Li, L.; Li, Y.; Xiao, Q.; Zhang, Y. Co(III)-catalyzed annulative vinylene transfer via C-H activation: Three-step total synthesis of 8-oxopseudopalmatine and oxopalmatine. Org. Lett. 2020, 22, 5925–5930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madala, H.B.; Gadi, R.K.; Ruchir, K.; Maddi, S.R. Ni-Catalyzed regio- and stereoselective addition of arylboronic acids to terminal alkynes with a directing group tether. Chem. Commun. 2017, 53, 3894–3897. [Google Scholar]

- Ito, H.; Koreishi, M.; Tokuda, H.; Nishino, H.; Yoshida, T. Cypellocarpins A-C, phenol glycosides esterified with oleuropeic acid from Eucalyptus cypellocarpa. J. Nat. Prod. 2000, 63, 1253–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawahara, E.; Fujii, M.; Kato, K.; Ida, Y.; Akita, H. Chemoenzymatic synthesis of naturally occurring benzyl 6-O-glycosyl-beta-D-glucopyranosides. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2005, 53, 1058–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y.; Liu, X.; Wu, Y.; Li, Y.; Guo, F. Meroterpenes from Psoralea corylifolia against Pyricularia oryzae. Planta. Med. 2014, 80, 1298–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.; Du, X.; Tang, W.; Zhou, Y.; Zuo, J.; Feng, H.; Li, Y. Synthesis and structure-immunosuppressive activity relationships of bakuchiol and its derivatives. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2008, 16, 2403–2411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shikishima, Y.; Takaishi, Y.; Honda, G.; Ito, M.; Takeda, Y.; Kodzhimatov, O.K.; Ashurmetov, O. Terpenoids and γ-pyrone derivatives from Prangos tschimganica. Phytochemistry 2001, 57, 135–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.J.; Jiang, H.X.; Gao, K. One novel nortriterpene and other constituents from Eupatorium fortune Turcz. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 2013, 47, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.Y.; Gong, L.M.; Wu, L.L.; She, S.Q.; Liao, Y.; Zheng, H.; Zhao, Z.F.; Liu, G.; Yan, S. Immunomodulatory effects of fermented fig (Ficus carica L.) fruit extracts on cyclophosphamide-treated mice. J. Funct. Foods. 2020, 75, 104219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, L.; Jin, H.Z.; Nie, L.Y.; Qin, J.J.; Fu, J.J.; Zhang, W.D. Chemical Constituents from Inula nervosa Wall. Nat. Prod. Res. Dev. 2011, 23, 258–261. [Google Scholar]

- Kitajima, J.; Ishikawa, T.; Tanaka, Y.; Ono, M.; Ito, Y.; Nohara, T. Water-soluble constituents of Fennel. V. glycosides of aromatic compounds. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1998, 46, 1587–1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smarrito, C.M.; Munari, C.; Robert, F.; Barron, D. A novel efficient and versatile route to the synthesis of 5-O-feruloylquinic acids. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2008, 6, 986–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Su, Y.F.; Gao, Y.H.; Yan, S.L. Chemical constituents from roots of Pteroxygonum giraldii. Chin. Tradit. Herbal. Drugs. 2013, 51, 16–18. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, E.J.; Kim, J.S.; Kim, H.P.; Lee, J.H.; Kang, S.S. Phenolic constituents from the flower buds of Lonicera japonica and their 5-lipoxygenase inhibitory activities. Food. Chem. 2010, 120, 134–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.S.; Oh, H.N.; Kwak, A.W.; Kim, E.; Lee, M.H.; Seo, J.H.; Cho, S.S.; Yoon, G.; Chae, J.I.; Shim, J.H. Deoxypodophyllotoxin inhibits cell growth and induces apoptosis by blocking EGFR and MET in gefitinib-resistant non-small cell lung cancer. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2021, 31, 559–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwak, A.W.; Lee, M.H.; Yoon, G.; Cho, S.S.; Choi, J.S.; Chae, J.I.; Shim, J.H. Deoxypodophyllotoxin, a lignan from Anthriscus sylvestris, induces apoptosis and cell cycle arrest by inhibiting the EGFR signaling pathways in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 6854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frisch, M.J.; Trucks, G.W.; Schlegel, H.B.; Scuseria, G.E.; Robb, M.A.; Cheeseman, J.R.; Scalmani, G.; Barone, V.; Petersson, G.A.; Nakatsuji, H.; et al. Gaussian 16, Revision A.03; Gaussian, Inc.: Wallingford, CT, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).