Three New Ionone Glycosides from Rhododendron capitatum Maxim

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

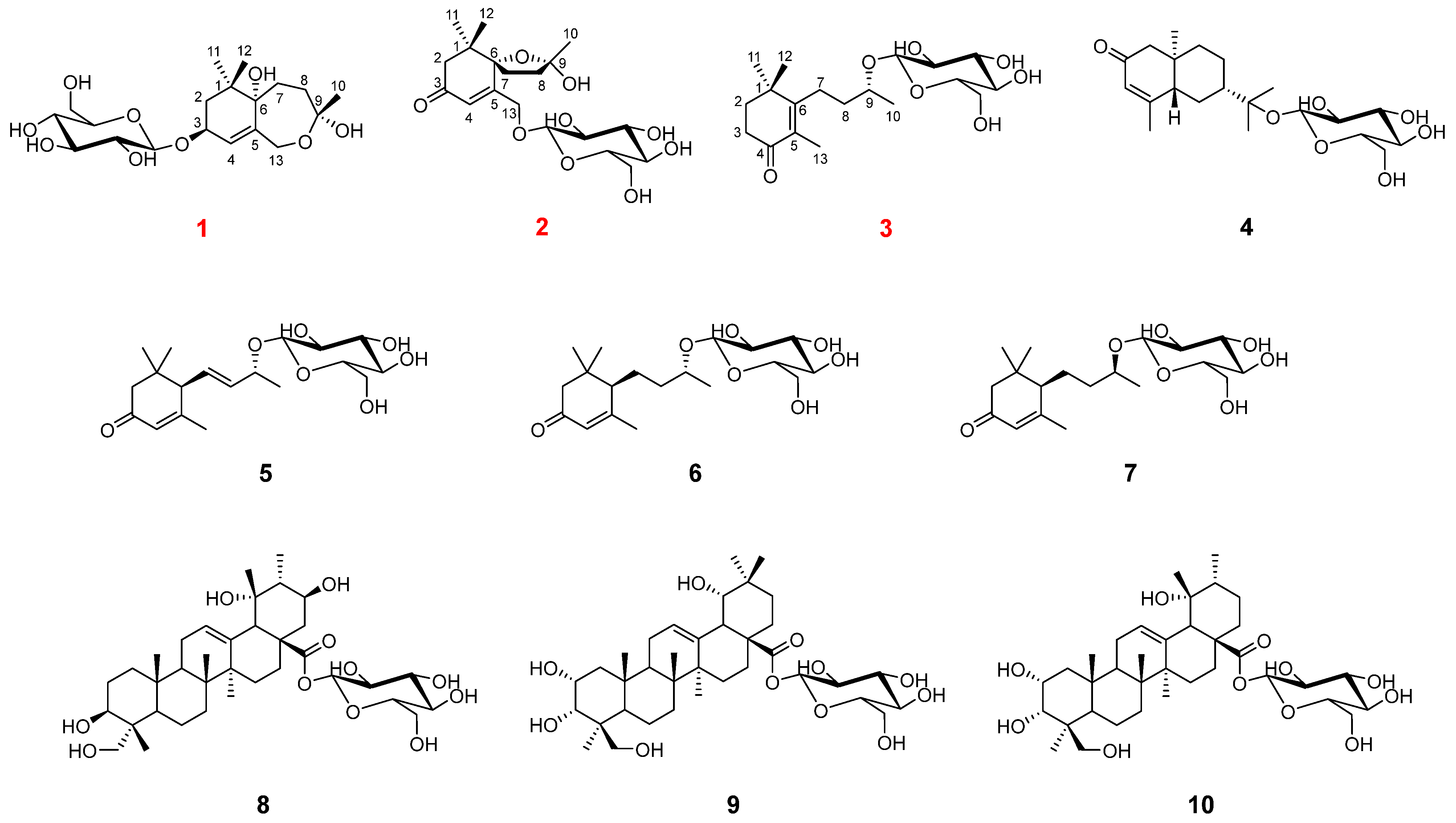

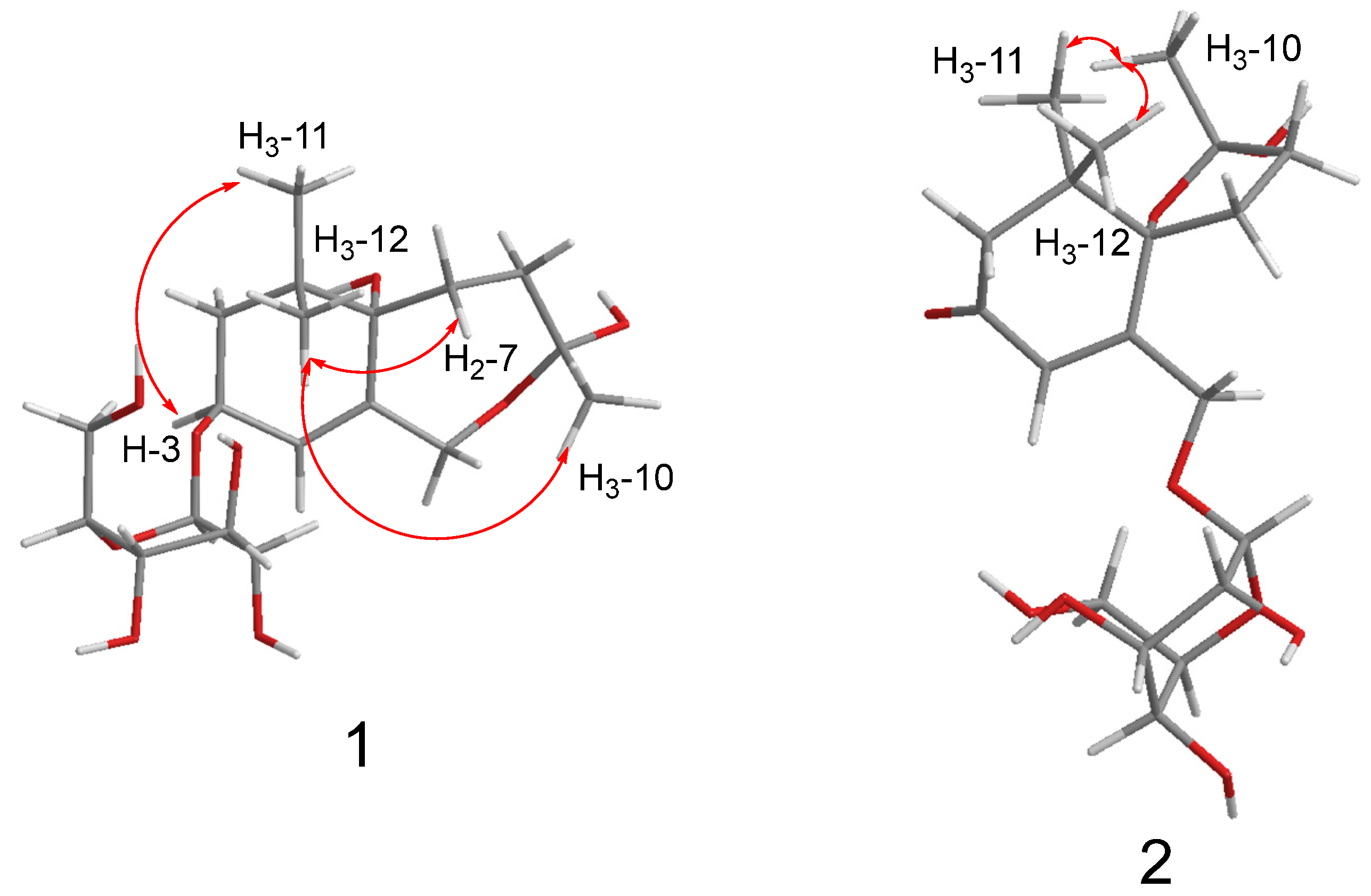

2.1. Structure Elucidation

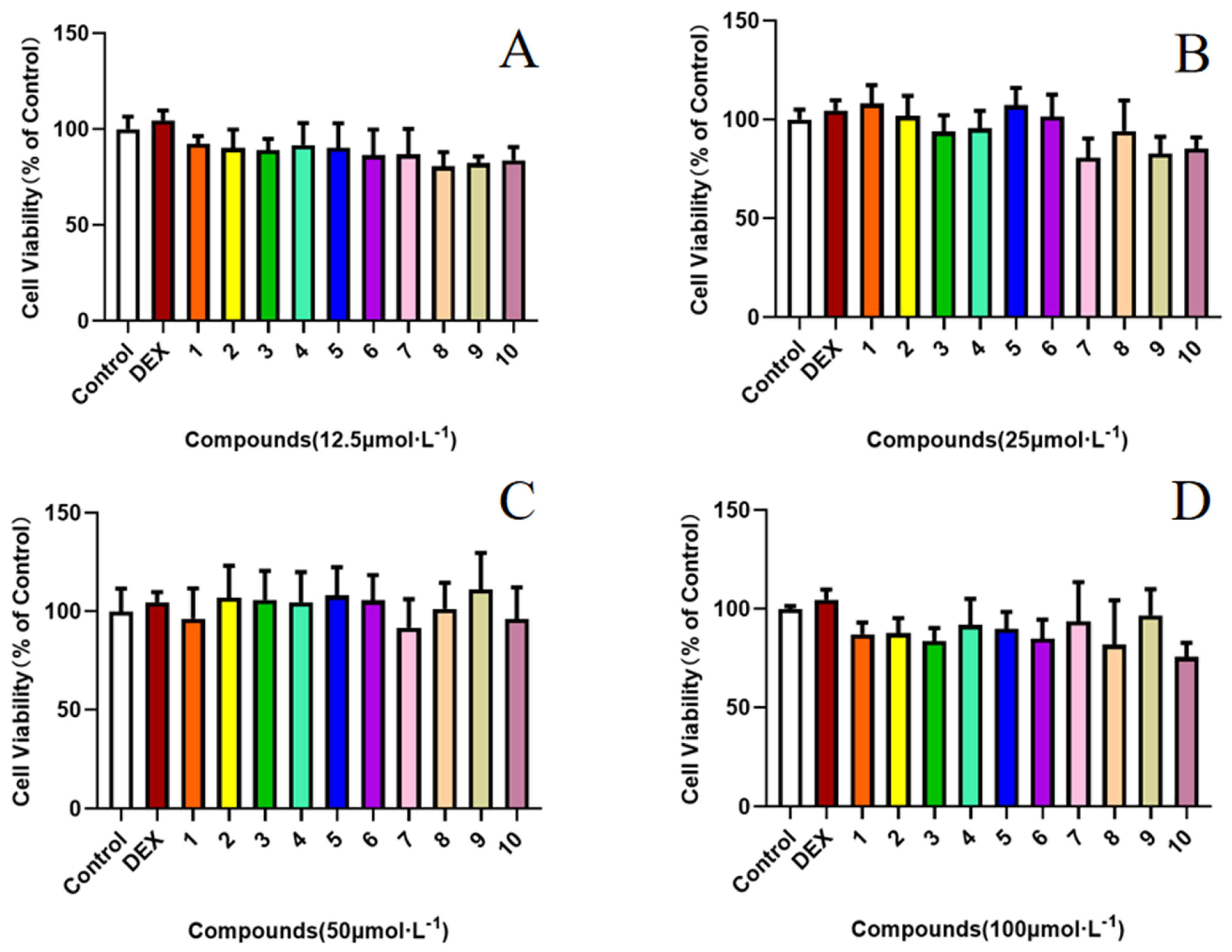

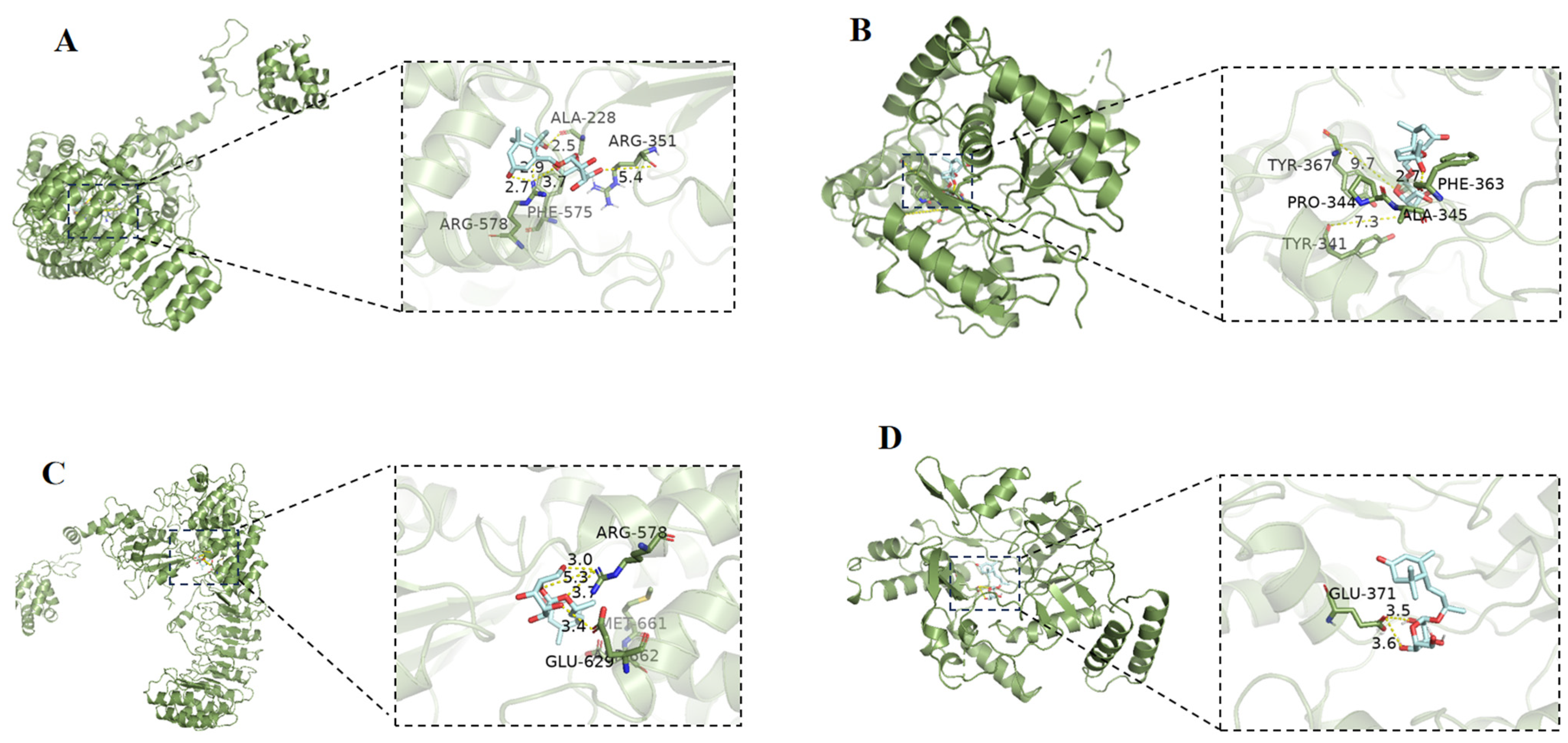

2.2. Effect of Compounds 1–10 on the LPS-Induced Production of NO

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. General Experimental Procedures

3.2. Plant Material

3.3. Extraction and Isolation

3.4. Acid Hydrolysis of Compounds 1–3

3.5. ECD Calculations

3.6. Cell Culture

3.7. MTT Assay for Cytotoxicity

3.8. Measurement of NO

3.9. Molecular Docking

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chen, X.; Cao, Y.G.; Ren, Y.J.; Liu, Y.L.; Fan, X.L.; He, C.; Li, X.D.; Ma, X.Y.; Zheng, X.K.; Feng, W.S. Ionones and lignans from the fresh roots of Rehmannia glutinosa. Phytochemistry 2022, 203, 113423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bendjedou, H.; Maggi, F.; Bennaceur, M.; Mancinelli, M.; Benamar, H.; Barboni, L. A new ionone derivative from Lycium intricatum Boiss. (Solanaceae). Nat. Prod. Res. 2022, 36, 687–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.; Cheng, R.R.; Han, Z.Z.; Yang, Y.B.; Zhou, Y.; Yang, L.; Wang, Z.T. A new ionone derivative from the leaves of Picrasma quassioides. J. Asian Nat. Prod. Res. 2019, 21, 652–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.X.; Li, Q.; Li, H.J.; Ning, Y.M.; Zhang, R.H.; Zhang, X.J.; Li, X.L.; Xiao, W.L. Centrantheroside F, a new ionone glycoside from Centranthera grandiflora. J. Asian Nat. Prod. Res. 2022, 24, 777–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, J.; Shi, G.R.; Zhang, W.Q.; Chen, R.Y.; Liu, Y.F.; Yu, D.Q. Four ionones and ionone glycosides from the whole plant of Rehmannia piasezkii. J. Asian Nat. Prod. Res. 2022, 24, 955–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.; Hu, H.; Pu, C.; Peng, D.; Wei, Z.; Kuang, H.; Wang, Q. New Ionone glycosides from the aerial parts of Allium sativum and their anti-platelet aggregation activity. Planta Med. 2023, 89, 729–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, H.B.; Huang, G.H.; Yu, M.H.; Lei, C.; Hou, A.J. Five pairs of meroterpenoid enantiomers from Rhododendron capitatum. J. Org. Chem. 2017, 82, 1632–1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, H.B.; Lei, C.; Gao, L.X.; Li, J.Y.; Li, J.; Hou, A.J. Two enantiomeric pairs of meroterpenoids from Rhododendron capitatum. Org. Lett. 2015, 17, 5040–5043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, C.; Kjaerulff, L.; Hansen, P.R.; Kongstad, K.T.; Staerk, D. Dual high-resolution α-glucosidase and PTP1B inhibition profiling combined with HPLC-PDA-HRMS-SPE-NMR analysis for the identification of potentially antidiabetic chromene meroterpenoids from Rhododendron capitatum. J. Nat. Prod. 2021, 84, 2454–2467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Shang, X.; Dai, L.; Yang, X.; Li, B.; Wei, Y.; Zhang, J.; Pan, H. Chemical constituents, antibacterial, acaricidal and anti-inflammatory activities of the essential oils from four Rhododendron species. Front. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 882060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.Y.; Li, P.; Yan, X.T.; Gao, J.M. Discovery from Hypericum elatoides and synthesis of hyperelanitriles as α-aminopropionitrile-containing polycyclic polyprenylated acylphloroglucinols. Commun. Chem. 2024, 7, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, X.T.; Chen, J.X.; Wang, Z.X.; Zhang, R.Q.; Xie, J.Y.; Kou, R.W.; Zhou, H.F.; Zhang, A.L.; Wang, M.C.; Ding, Y.X.; et al. Hyperhubeins A–I, Bioactive Sesquiterpenes with Diverse Skeletons from Hypericum hubeiense. J. Nat. Prod. 2023, 86, 119–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Tommasi, N.; Piacente, S.; De Simone, F.; Pizza, C. Constituents of Cydonia vulgaris: Isolation and structure elucidation of four new flavonol glycosides and nine new α-ionol-derived glycosides. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1996, 44, 1676–1681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, L.; Zhou, Q.M.; Peng, C.; Xie, X.F.; Guo, L.; Li, X.H.; Liu, J.; Liu, Z.H.; Dai, O. Sesquiterpenoids from the herb of Leonurus japonicus. Molecules 2013, 18, 5051–5058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knapp, H.; Weigand, C.; Gloser, J.; Winterhalter, P. 2-Hydroxy-2,6,10,10-tetramethyl-1-oxaspiro[4.5]dec-6-en-8-one: Precursor of 8,9-dehydrotheaspirone in white-fleshed nectarines. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1997, 45, 1309–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viet Thanh, N.T.; Minh, T.T.; Linh, N.T.; Phuong Ly, G.T.; Trang, D.T.; Tai, B.H.; Kiem, P.V. Megastigmane glycosides from Phoebe tavoyana. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2019, 14, 1934578X1985243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamano, Y.; Shimizu, Y.; Ito, M. Stereoselective synthesis of optically active 3-hydroxy-7,8-dihydro-β-ionol-glucosides. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2003, 51, 878–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kitajima, J.; Kamoshita, A.; Ishikawa, T.; Takano, A.; Fukuda, T.; Isoda, S.; Ida, Y. Glycosides of Atractylodes iancea. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2003, 51, 673–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pabst, A.; Barron, D.; Sémon, E.; Schreier, P. Two diastereomeric 3-oxo-α-ionol β-D-glucosides from raspberry fruit. Phytochemistry 1992, 31, 1649–1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeda, Y.; Zhang, H.; Masuda, T.; Honda, G.; Otsuka, H.; Sezik, E.; Yesilada, E.; Sun, H. Megastigmane glucosides from Stachys byzantina. Phytochemistry 1997, 44, 1335–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, X.; Lin, D.C.; Zhang, W.D.; Zhang, X.R. Triterpenoid saponins and monoterpenoid glycosides from Incarvillea delavayi. J. Asian Nat. Prod. Res. 2009, 11, 838–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ono, M.; Chikuba, T.; Mishima, K.; Yamasaki, T.; Ikeda, T.; Yoshimitsu, H.; Nohara, T. A new diterpenoid and a new triterpenoid glucosyl ester from the leaves of Callicarpa japonica Thunb. var. luxurians Rehd. J. Nat. Med. 2009, 63, 318–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.T.; Fang, H.B.; Liu, X.N.; Yan, Y.M.; Feng, W.S.; Cheng, Y.X.; Wang, Y.Z. Unusual acetylated flavonol glucuronides, oxyphyllvonides A-H with renoprotective activities from the fruits of Alpinae oxyphylla. Phytochemistry 2023, 215, 113849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruhn, T.; Schaumlöffel, A.; Hemberger, Y.; Bringmann, G. SpecDis: Quantifying the comparison of calculated and experimental electronic circular dichroism spectra. Chirality 2013, 25, 243–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kou, R.W.; Han, R.; Gao, Y.Q.; Li, D.; Yin, X.; Gao, J.M. Anti-neuroinflammatory polyoxygenated lanostanoids from Chaga mushroom Inonotus obliquus. Phytochemistry 2021, 184, 112647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

) and 1H-1H COSY (

) and 1H-1H COSY ( ) correlations of compounds 1–3.

) correlations of compounds 1–3.

) correlations of compounds 1 and 2.

) correlations of compounds 1 and 2.

| No. | 1 | 2 | 3 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| δC | δH | δC | δH | δC | δH | |

| 1 | 35.8 | 43.0 | 37.6 | |||

| 2 | 41.8 | 1.75 (m) | 50.7 | 2.58 (d, 17.4) 1.20 (d, 17.4) | 38.4 | 1.82 (t, 7.2) |

| 3 | 73.9 | 4.36 (dd, 6.4, 4.7) | 200.7 | 35.1 | 2.45 (t, 7.2) | |

| 4 | 124.8 | 5.77 (br s) | 122.6 | 6.19 (s) | 201.5 | |

| 5 | 137.3 | 168.1 | 131.6 | |||

| 6 | 85.4 | 91.4 | 1.50 (m) | 168.7 | ||

| 7 | 29.8 | 2.10 (dd, 12.8, 4.6) 1.75 (m) | 31.7 | 2.44 (m) 2.10 (dd, 14.5, 5.9) | 27.9 | 2.53 (m) 2.31 (m) |

| 8 | 35.7 | 2.19 (m) 1.96 (dd, 12.8, 4.6) | 40.0 | 2.10 (dd, 14.5, 5.9) 2.01 (dd, 14.5, 9.6) | 37.2 | 1.67 (m) |

| 9 | 108.3 | 111.1 | 75.7 | 3.97 (m) | ||

| 10 | 24.3 | 1.39 (s) | 21.4 | 1.52 (s) | 19.8 | 1.23 (d, 6.2) |

| 11 | 23.5 | 0.99 (s) | 23.3 | 1.01 (s) | 27.2 | 1.20 (s) |

| 12 | 24.1 | 0.96 (s) | 24.9 | 1.03 (s) | 27.2 | 1.20 (s) |

| 13 | 66.7 | 4.48 (d, 12.3) 4.02 (d, 12.3) | 67.9 | 4.73 (dd, 18.4, 2.0) 4.54 (dd, 18.4, 2.0) | 11.7 | 1.76 (s) |

| 1′-Gly | 103.5 | 4.40 (d, 7.8) | 104.0 | 4.33 (d, 7.7) | 102.2 | 4.35 (d, 7.8) |

| 2′-Gly | 75.1 | 3.17 (m) | 75.0 | 3.26 (m) | 75.2 | 3.17 (dd, 9.0, 7.8) |

| 3′-Gly | 78.0 | 3.35 (m) | 78.1 | 3.36 (m) | 77.9 | 3.37 (m) |

| 4′-Gly | 71.6 | 3.28 (m) | 71.6 | 3.36 (m) | 71.8 | 3.37 (m) |

| 5′-Gly | 77.9 | 3.28 (m) | 78.1 | 3.26 (m) | 78.2 | 3.28 (m) |

| 6′-Gly | 62.8 | 3.86 (dd, 12.0, 2.2) 3.67 (dd, 12.0, 5.4) | 62.7 | 3.86 (dd, 12.0, 2.0) 3.68 (dd, 12.0, 5.3) | 62.9 | 3.88 (dd, 12.0, 2.0) 3.66 (dd, 12.0, 5.0) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yang, J.-R.; Zhu, Y.-T.; Zeng, Y.-Q.; Li, H.-Q.; Li, C.-H.; Gao, J.-M. Three New Ionone Glycosides from Rhododendron capitatum Maxim. Molecules 2024, 29, 2462. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules29112462

Yang J-R, Zhu Y-T, Zeng Y-Q, Li H-Q, Li C-H, Gao J-M. Three New Ionone Glycosides from Rhododendron capitatum Maxim. Molecules. 2024; 29(11):2462. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules29112462

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Jun-Ren, Yue-Tong Zhu, Yi-Qin Zeng, Hong-Quan Li, Chun-Huan Li, and Jin-Ming Gao. 2024. "Three New Ionone Glycosides from Rhododendron capitatum Maxim" Molecules 29, no. 11: 2462. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules29112462

APA StyleYang, J.-R., Zhu, Y.-T., Zeng, Y.-Q., Li, H.-Q., Li, C.-H., & Gao, J.-M. (2024). Three New Ionone Glycosides from Rhododendron capitatum Maxim. Molecules, 29(11), 2462. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules29112462