Equipment-Free Fabrication of Thiolated Reduced Graphene Oxide Langmuir–Blodgett Films: A Novel Approach for Versatile Surface Engineering

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. The Impact of Organic Solvents on m-RGO Langmuir Film Formation

2.2. Elemental and Functional Group Analysis of m-RGO

2.3. Optical and Electrical Characterization of m-RGO LB Film

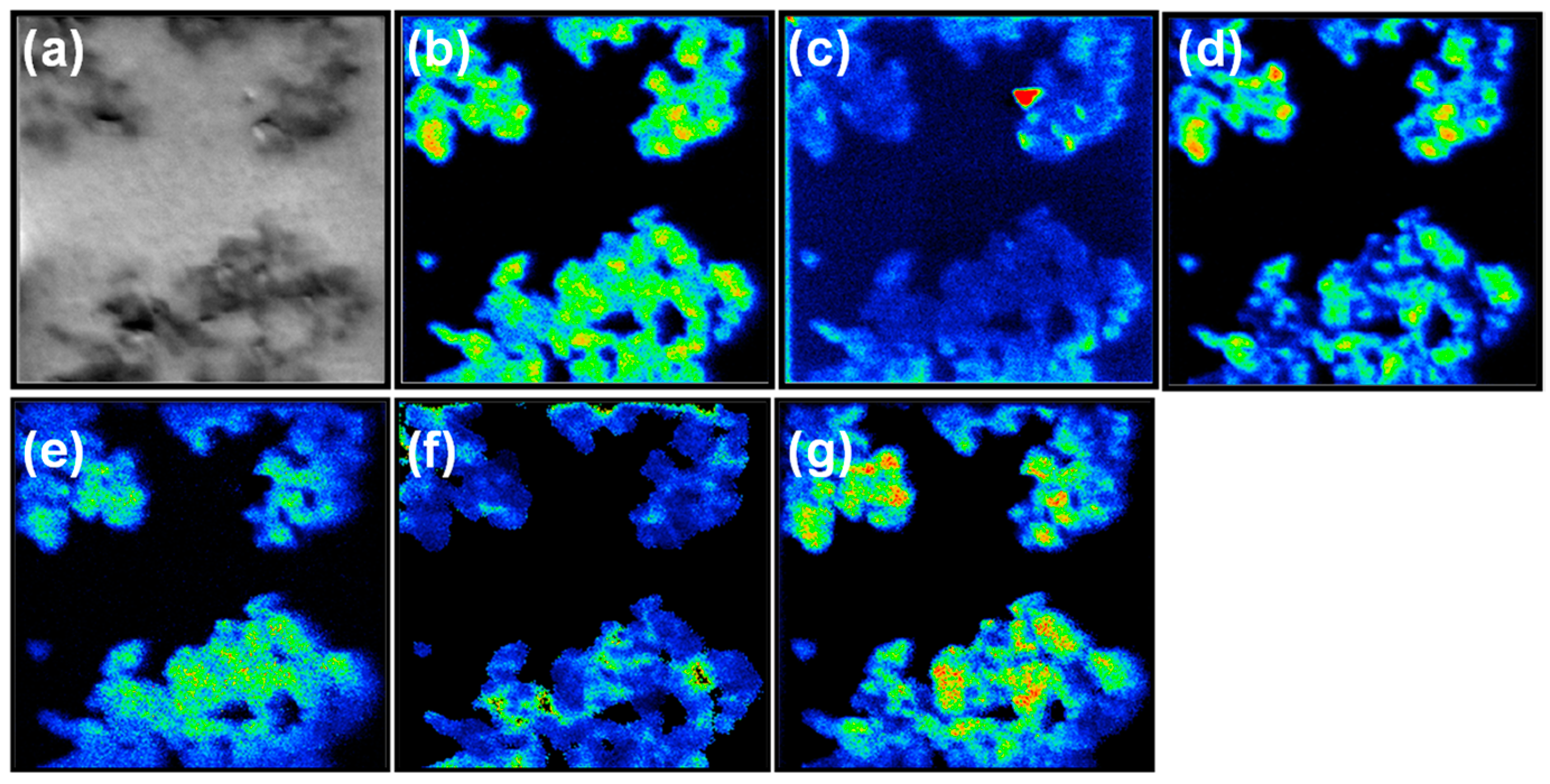

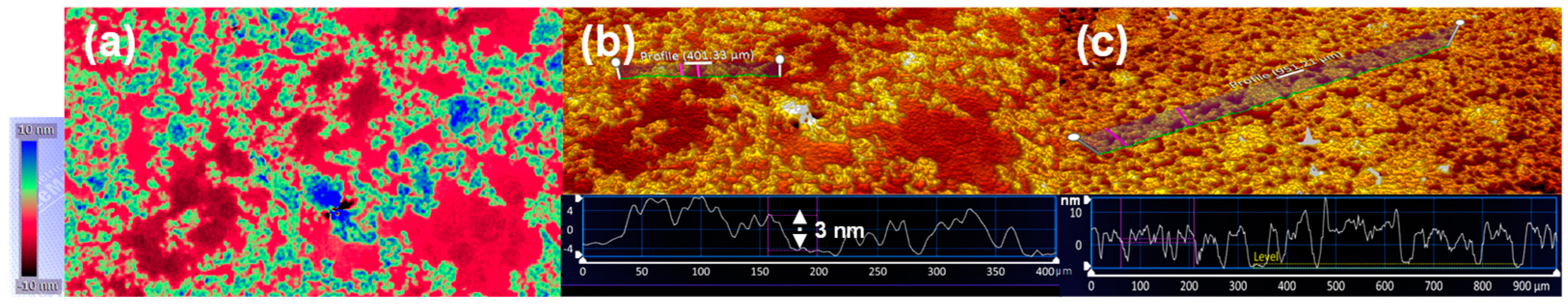

2.4. Structural Analysis of m-RGO Langmuir Film on Water and m-RGO LB Film

3. Experimental Section

3.1. Synthesis of Mercapto Reduced Graphene Oxide (m-RGO)

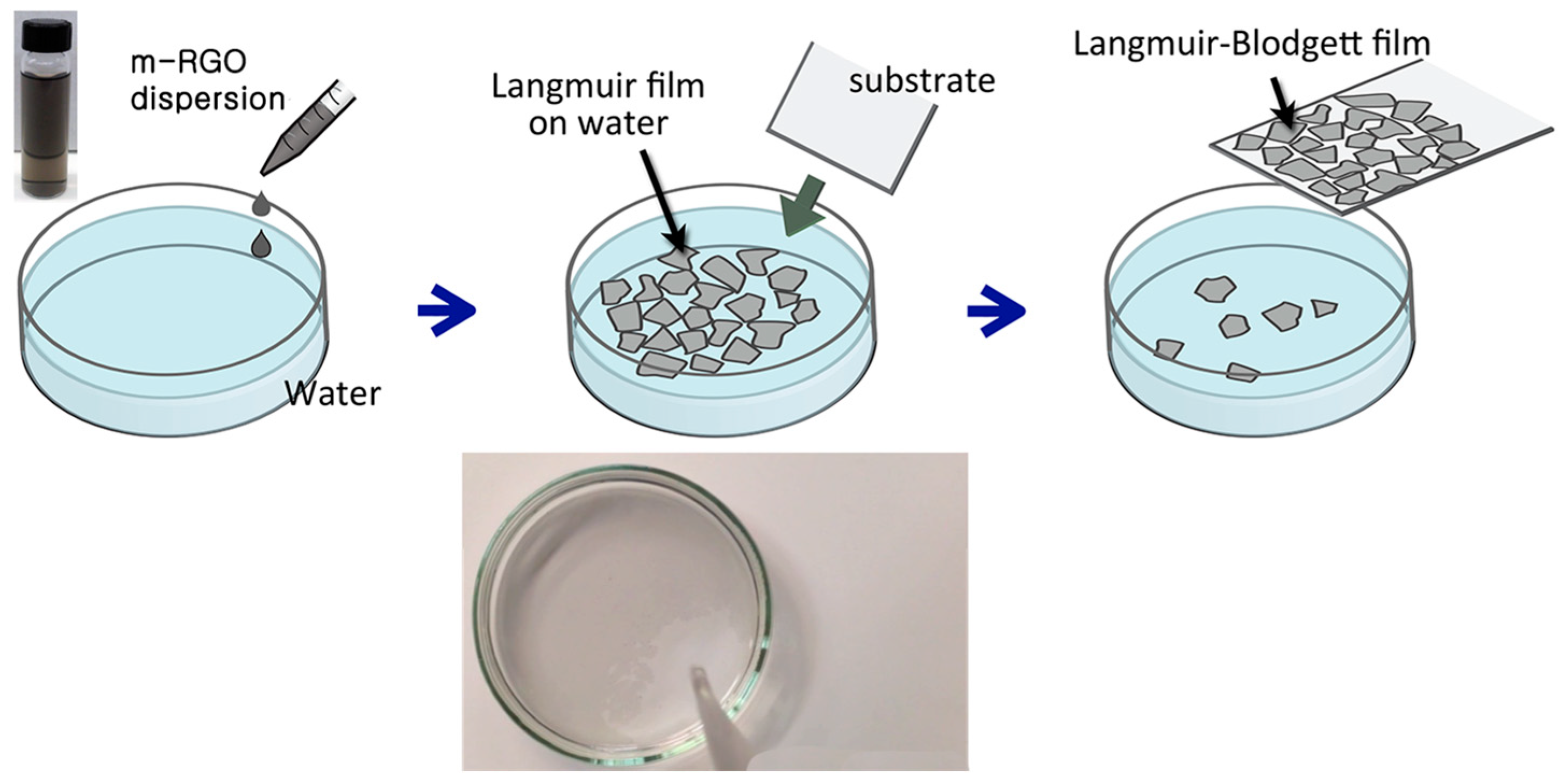

3.2. Fabrication of m-RGO Langmuir–Blodgett (LB) Film

3.3. Materials Characterization

4. Concluding Remarks

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Qiu, T.; Akinoglu, E.M.; Luo, B.; Konarova, M.; Yun, J.-H.; Gentle, I.R.; Wang, L. Nanosphere lithography: A versatile approach to develop transparent conductive films for optoelectronic applications. Adv. Mater. 2022, 34, 2103842–2103868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anzni, M.-R.; Hassanpour, A.; Torres, T. Benefits, problems, and solutions of silver nanowire transparent conductive electrodes in indium tin oxide (ITO)-free flexible solar cells. Adv. Energy Mater. 2020, 10, 2002536–2002568. [Google Scholar]

- Deepak, D.; Soin, N.; Roy, S. Optimizing the efficiency of triboelectric nanogenerators by surface nanoarchitectonics of graphene-based electordes: A review. Mater. Today Commun. 2023, 34, 105412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, J.; Fan, T. Flexible and stretchable transparent conductive graphene-based electrodes for emerging wearable electrodnics. Carbon 2023, 15, 495–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, M.; Alshammari, Y.; Majeed, S.A.; Al-Nasrallah, E. Chemical vapour deposition of graphene-synthesis, characterization, and applications: A review. Molecules 2020, 15, 3856–3918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norimatsu, W. A review on carrier mobilities of epitaxial graphene on silicon carbide. Materials 2023, 16, 7668–7682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Y.; Shi, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Bu, S.; Hu, Z.; Liao, J.; Lu, Q.; Zhou, C.; Guo, B.; Shang, M.; et al. Recent trends in the transfer of graphene film. Nanoscale 2024, 16, 7862–7873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razaq, A.; Bibi, F.; Zheng, X.; Papadakis, R.; Jafri, S.H.M.; Li, H. Review on graphene-, graphene oxide-, reduced graphene oxide-based flexible composites: From fabrication to applications. Materials 2022, 15, 1012–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwon, O.; Choi, Y.; Choi, E.; Kim, M.; Woo, Y.C.; Kim, D.W. Fabrication techniques for graphene oxide-based molecular separation membranes: Towards industrial applicaion. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 757–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, Y.T.; Kim, S.J.; Kang, K.M.; Jung, W.-B.; Kim, D.W.; Jung, H.-T. Enhanced nanofiltration performance of graphene-based membranes on wrinkled polymer supports. Carbon 2019, 148, 370–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, C.; Wang, X.; Peng, Y.; Qian, Y.; Hu, Z.; Dong, J.; Zhao, D. Facile Preparation of Graphene Oxide Membranes for Gas separation. Chem. Mater. 2016, 28, 2921–2927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Shen, Q.; Hou, J.; Sutrisna, P.D.; Chen, V. Shear-aligned graphene oxide laminate/Pebax ultrathin composite hollow fiber membranes using a facile dip-coating approach. J. Mater. Chem. A 2017, 5, 7732–7737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heo, J.; Choi, M.; Hong, J. Facile surface modification of polyethylene film via spray-assisted layer-by-layer self-assembly of graphene oxide for oxygen barrier properties. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 2754–2761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Periasamy, V.; Jaafar, M.M.; Chandrasekaran, K.; Talebi, S.; Ng, F.L.; Phang, S.M.; Kumar, G.G.; Iwamoto, M. Langmuir-Blodgett graphene-based films for algal biophotovoltaic fuel cells. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 840–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, Y.J.; Hong, W.G.; Kim, W.J.; Jun, Y.; Kim, B.H. A novel method for applying reduced graphene oxide directly to electronic textiles from yarns to fabrics. Adv. Mater. 2013, 25, 5701–5705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Liu, S.; Shen, J.; Wei, L.; Liu, A.; Chan-Park, M.B.; Chen, Y. Ethanol-assisted graphene oxide-based thin film formation at pentane-water interface. Langmuir 2011, 15, 9174–9181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ariga, K. Liquid-liquid interfacial nanoarchitectonics. Small 2023, 2305636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chhowalla, G.E.M. Chemically derived graphene oxide: Towards large-area thin film electronics and optoelectronics. Adv. Mater. 2010, 22, 2392–2415. [Google Scholar]

- Saroja, A.P.V.K.; Muthusamy, K.; Sundara, R. Strong surface bonding of polysulfides by teflonized carbon matrix for enhanced performance in room temperature sodium-sulfur battery. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 6, 1801873–1801882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; Zhang, D.; Wang, X.; Jin, H.; Zhang, W.; Tong, B.; Liu, Y.; Burn, P.; Cheng, H.-M.; Ren, W. Extremely efficient flexible organic solar cells with a graphene transparent anode: Dependence on number of layers and doping of graphene. Carbon 2021, 171, 350–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.-G.; Bae, J.-S.; Hwang, I.; Kim, S.-H.; Jeon, K.-W. Superior heavy metal ion adsorption capacity in aqueous solution by high-density thiol-functionalized reduced graphene oxides. Molecules 2023, 28, 3998–4010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, K.-W. Easily processable, highly transparent and conducting thiol-functionalized reduced graphene oxides Langmuir-Blodgett films. Molecules 2021, 26, 2686–2698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Jeon, K.-W.; Seo, D.-K. Equipment-free deposition of graphene-based molybdenum oxide nanohybrid Langmuir-Blodgett films for flexible electrochromic panel application. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 24, 21539–21544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Solvent | Surface Tension (mN/m at 20 °C) | Density (g/mL) | Miscibility | Langmuir Film Formation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ethanol | 22.1 | 0.79 | miscible | Very Good |

| Methanol | 22.7 | 0.79 | miscible | Very Good |

| Acetone | 25.2 | 0.79 | miscible | Very Good |

| Dimethylformamide | 37.1 | 0.95 | miscible | Very Good |

| N-Methyl-2-pyrrolidone | 41 | 1.03 | miscible | No Langmuir film forms |

| Dimethylsulfoxide | 43.54 | 1.10 | miscible | Not Good |

| Ethyl acetate | 23.52 | 0.90 | immiscible | Not Good |

| Butanol | 24.21 | 0.81 | immiscible | Not Good |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hwang, I.; Jeon, K.-W. Equipment-Free Fabrication of Thiolated Reduced Graphene Oxide Langmuir–Blodgett Films: A Novel Approach for Versatile Surface Engineering. Molecules 2024, 29, 2464. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules29112464

Hwang I, Jeon K-W. Equipment-Free Fabrication of Thiolated Reduced Graphene Oxide Langmuir–Blodgett Films: A Novel Approach for Versatile Surface Engineering. Molecules. 2024; 29(11):2464. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules29112464

Chicago/Turabian StyleHwang, Injoo, and Ki-Wan Jeon. 2024. "Equipment-Free Fabrication of Thiolated Reduced Graphene Oxide Langmuir–Blodgett Films: A Novel Approach for Versatile Surface Engineering" Molecules 29, no. 11: 2464. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules29112464

APA StyleHwang, I., & Jeon, K.-W. (2024). Equipment-Free Fabrication of Thiolated Reduced Graphene Oxide Langmuir–Blodgett Films: A Novel Approach for Versatile Surface Engineering. Molecules, 29(11), 2464. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules29112464