Efficient Lead Pb(II) Removal with Chemically Modified Nostoc commune Biomass

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

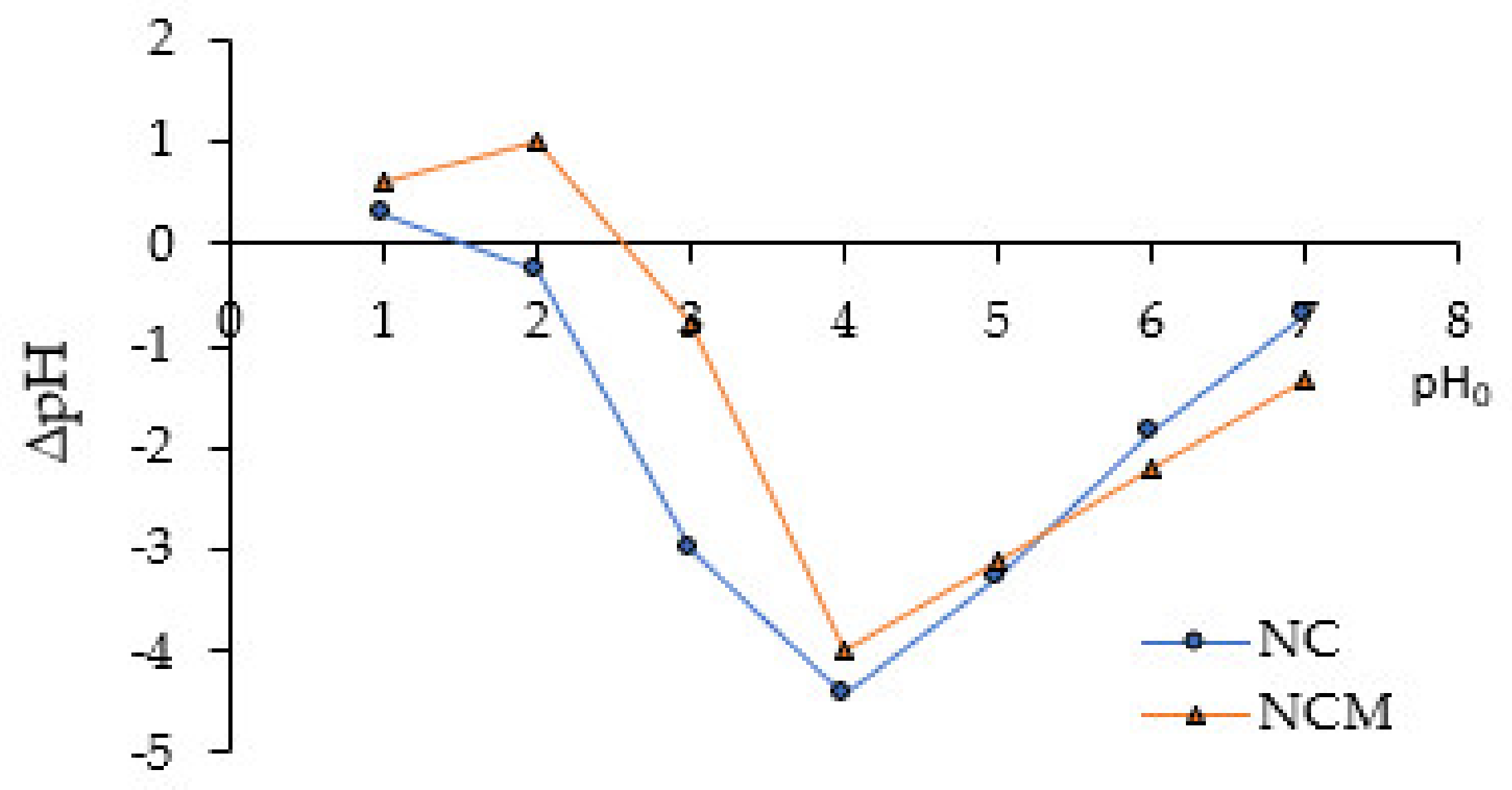

2.1. Effect of Alkaline Treatment, Concentration of Acidic and Basic Sites, pHPZC Determination

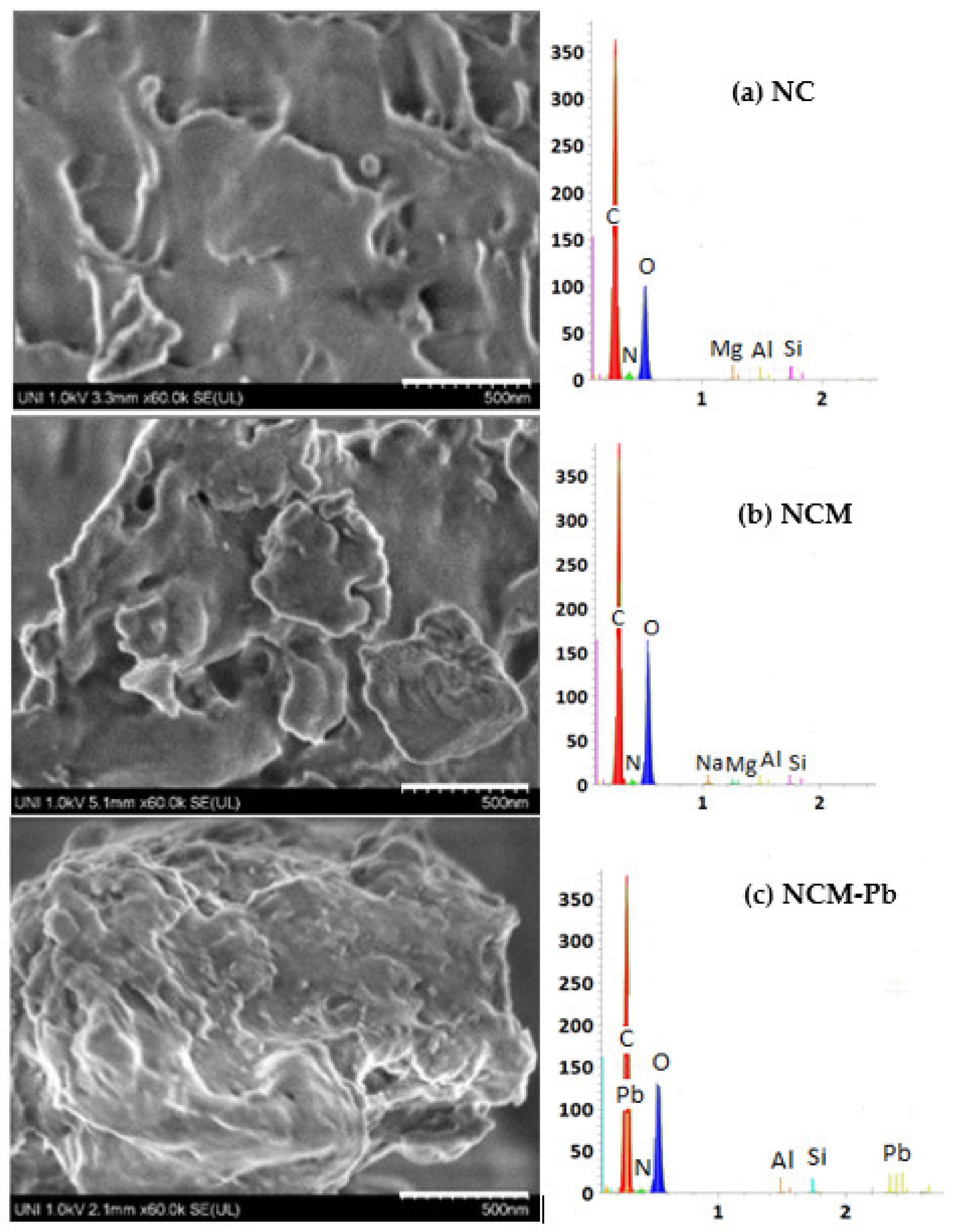

2.2. SEM/EDX Morphological and Structural Characterization, FTIR Analysis

FTIR Analysis

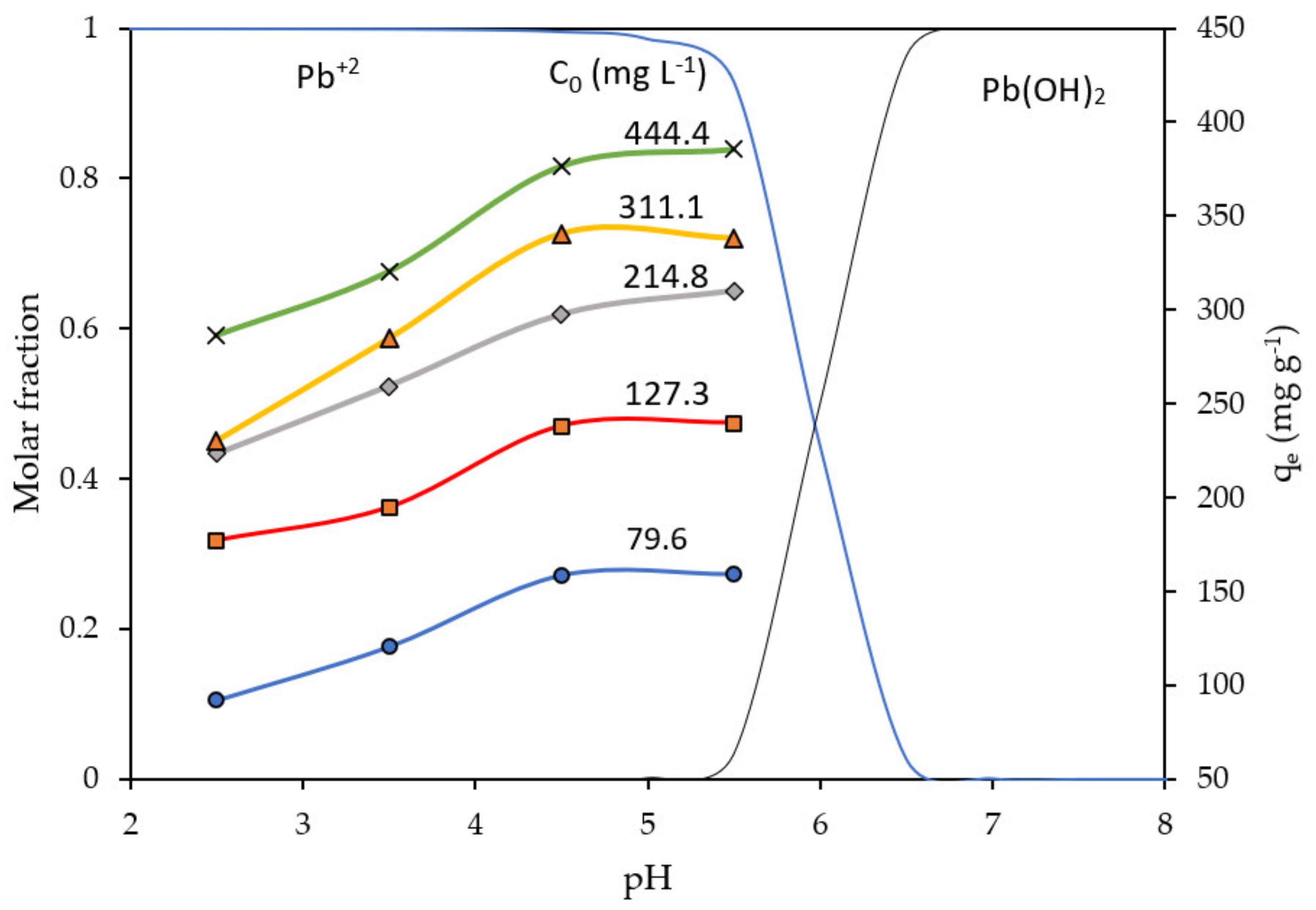

2.3. Influence of pH Solution

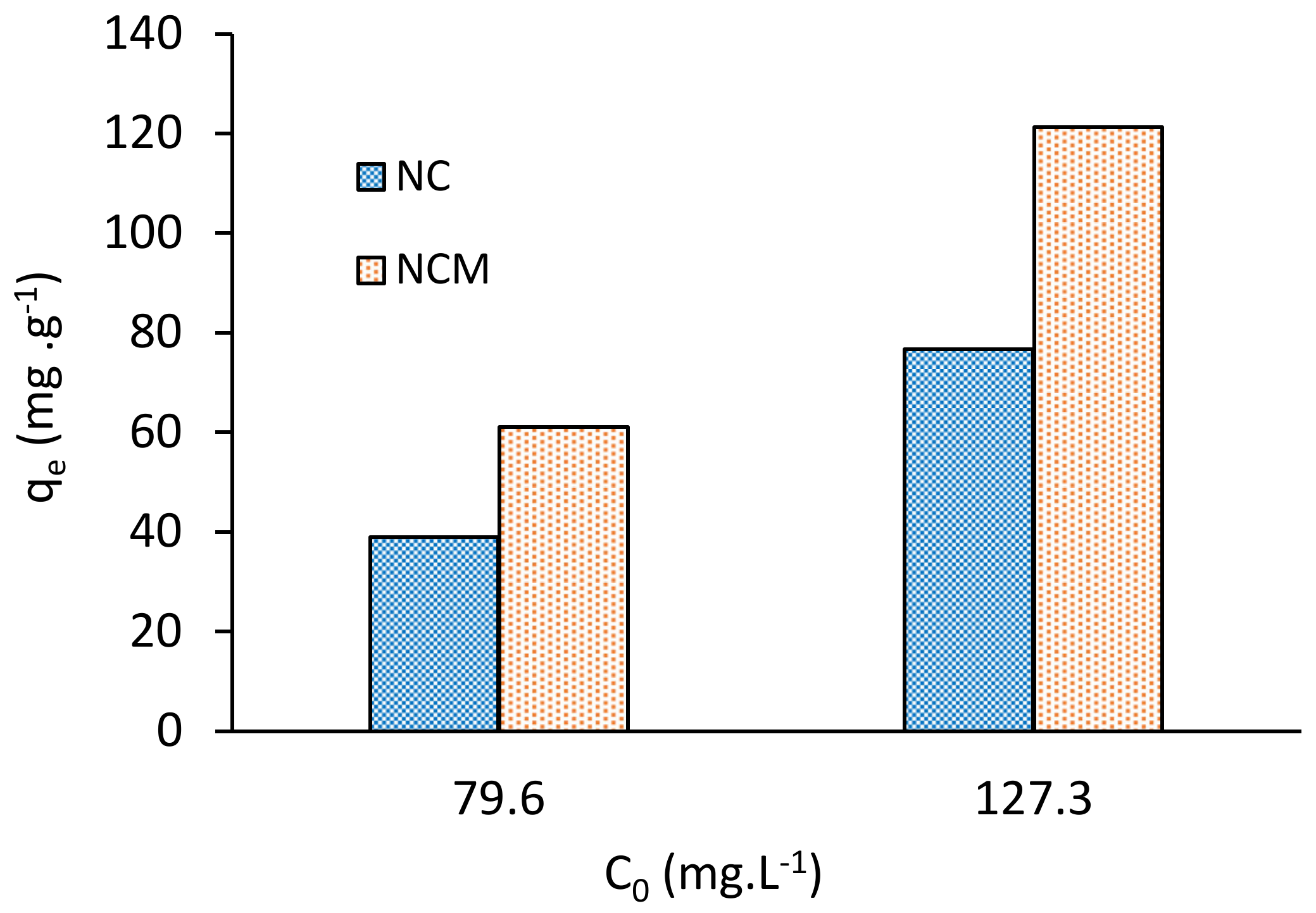

2.4. Influence of NCM Dose and Initial Concentration of Pb(II) Ions, C0

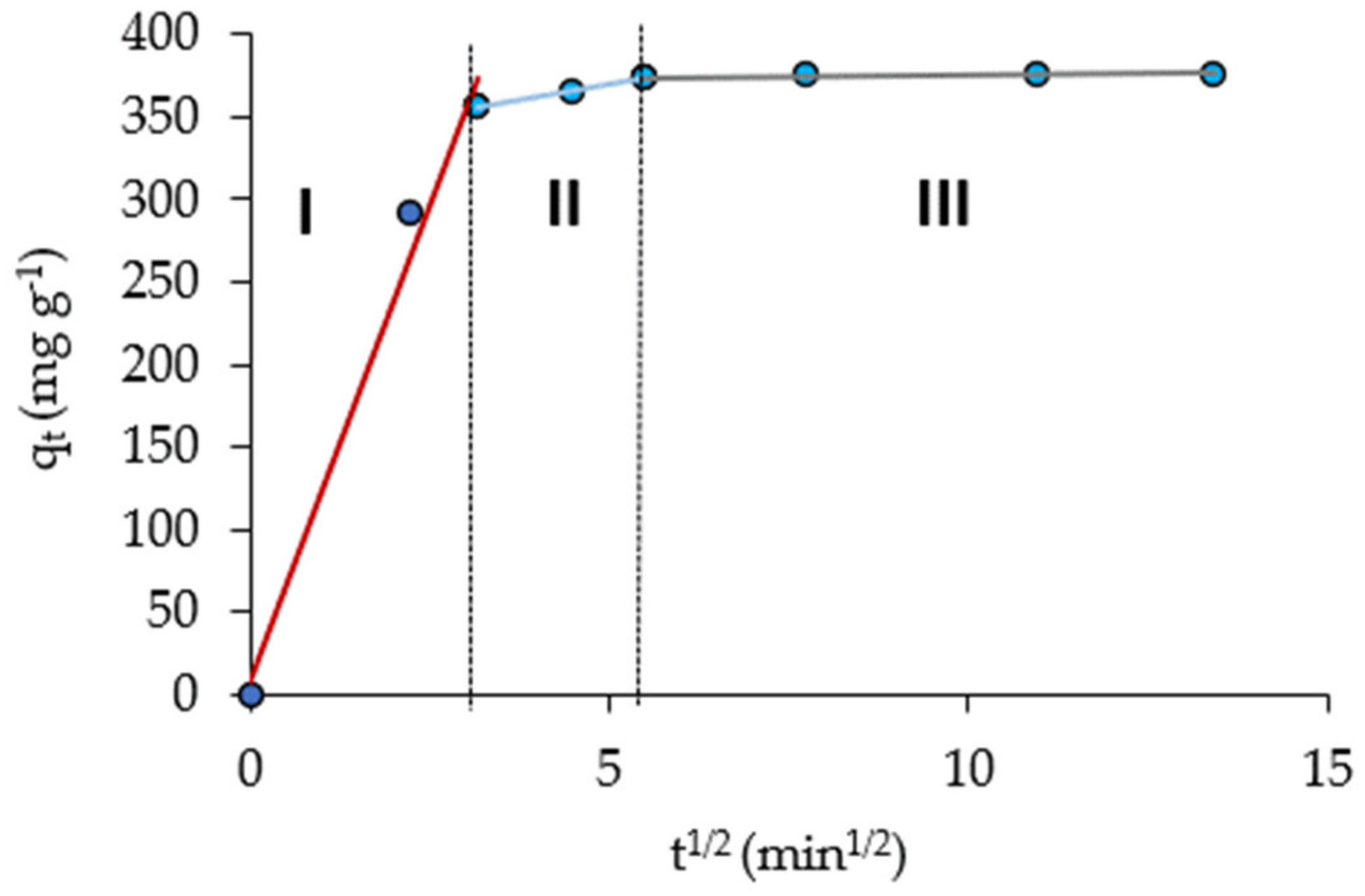

2.5. Kinetic of Biosorption

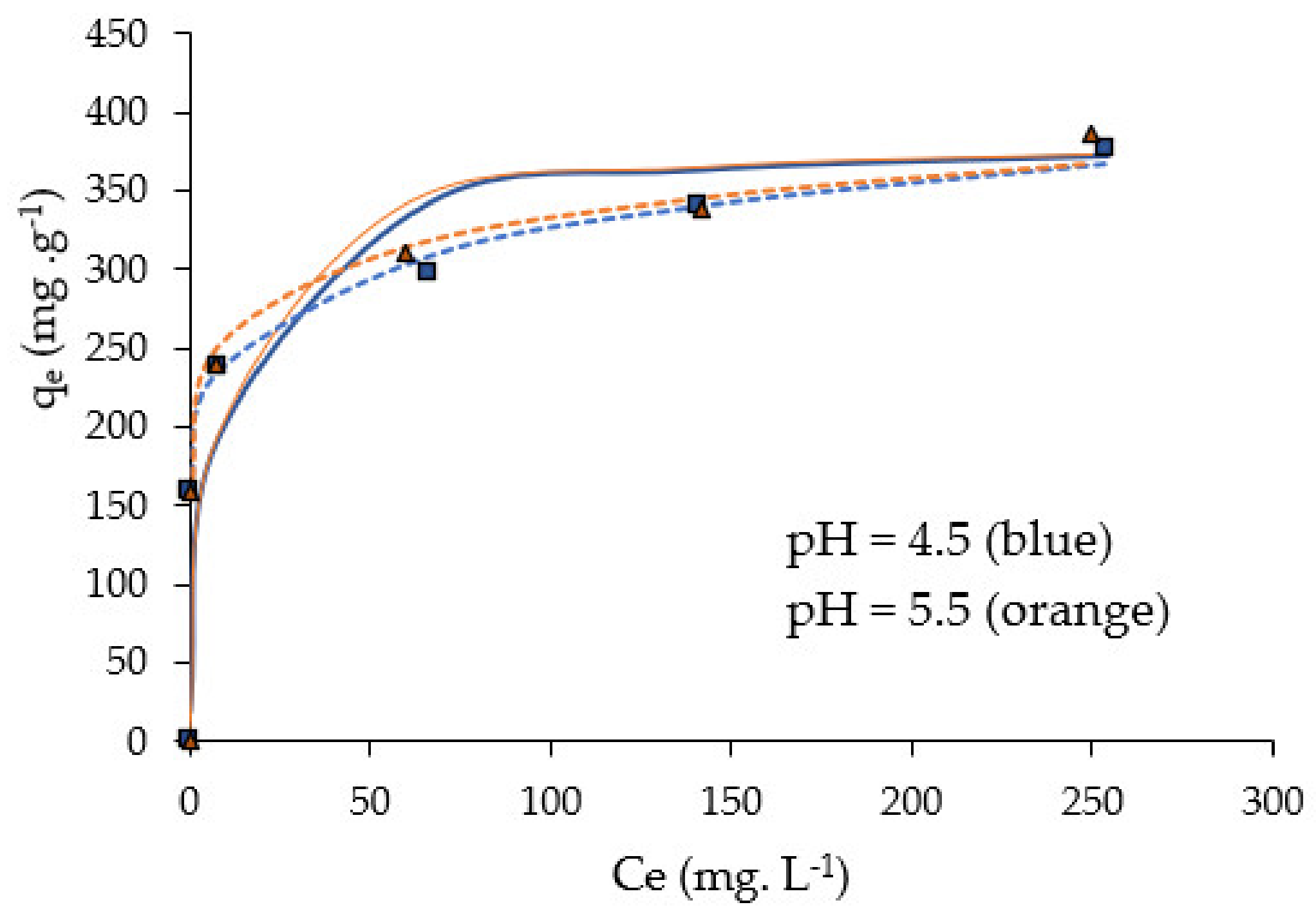

2.6. Adsorption Isotherms

2.7. Biosorption Thermodynamics

2.8. NCM for the Pb(II) Removal in Real-Wastewater

2.9. Regeneration of NCM Biosorbent

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Preparation of Nostoc Commune Biosorbent

- Untreated biomass (NC)

- Treated biomass (NCM)

3.2. Biosorbent Characterization

- The point zero of charge pH values (pHPZC) were determined according to the procedures described by do Nascimento et al. [20]. It has been prepared as a mixture of 0.05 g of biosorbent with 50 mL of aqueous solutions under different initial pHs (pH0) ranging from 1 to 8. The acid solutions were prepared from 1 M HCl, while the basic solutions were prepared from 1 M NaOH. After 24 h of equilibrium, the final pHs (pHf) were determined.

- A Fourier transform infrared spectrophotometer (FTIR, SHIMADZU- 8700) was used to identify the functional groups present on the surface of biosorbents. The wavelength was set to 4000 to 400 cm−1.

- Morphological and elemental analysis of the biosorbent surface were performed by scanning electron microscopy (SEM) coupled with EDX (energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy) (Hitachi SU8230 model).

- The concentration of acid and basic sites was determined by the Boehm method following the procedures described by do Nascimento et al. [51].

3.3. Biosorption Assays

3.4. Desorption Experiments

4. Conclusions

- Nostoc commune cyanobacteria was chemically modified, with a 0.1 M NaOH. The Pb(II) adsorption capacity of the treated biomass (NCM) was almost 1.6 times higher than for untreated biomass (NC).

- Point zero of charge, pHPZC, of NCM (= 2.5) was greater than for NC (=1.3). It is consistent with the concentration of basic sites, which is almost six times higher for treated than untreated biosorbents. The basic sites would be associated with OH, C=O, COH, COO− and NH functional groups (identified by FTIR).

- SEM/EDX analyses of NCM showed a more porous and cracked surface than NC, but once charged with Pb(II), the morphology changed to a less rough and porous surface.

- For a given initial Pb ions concentration, C0, the biosorption capacity qe of NCM reached a maximum plateau at a pH between pH 4.5 and 5.5.

- We consider 0.5 g L−1 the optimal NCM dose for Pb(II) removal, given that the corresponding efficiency, %R, can reach almost 97% for low C0 values.

- The adsorption kinetic data were well fitted with the pseudo-second order model, indicating that the Pb(II) biosorption on NCM was a chemisorption process, with a removal capacity of qe = 384.6 mg g−1. The Elovich kinetic model indicated a rapid sorption of Pb(II). It is consistent for the first stage described by the intra-particle diffusion Weber–Morris model, since, in the following stages, Pb(II) adsorption was very slow.

- The adsorption isotherms’ data were well fitted with the Freundlich model (heterogeneous adsorption) at pH 4.5 and 5.5. Freundlich, Dubinin–Radushkevich and Temkin models confirmed that Pb(II) adsorption on NCM is a chemisorption process, which was thermodynamically characterized as exothermic (ΔH0 < 0), feasible and spontaneous (ΔG0 < 0) and with a decreasing randomness (ΔS0 < 0) at the solid/liquid interface.

- The maximum Pb(II) biosorption capacity of NCM, qe,max= 384.6 mg g−1, is higher than for other similar treated biosorbents reported in the literature.

- Desorption–regeneration experiments showed that NCM can be recovered efficiently (%D > 92%) up to four times.

- NCM was tested as an inexpensive and efficient biosorbent to remove Pb and Ca, from real wastewater, with an efficiency %R of almost 98% and 64%, respectively.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Correction Statement

Sample Availability

References

- Lee, J.W.; Choi, H.; Hwang, U.K.; Kang, J.C.; Kang, Y.J.; Kim, K., II; Kim, J.H. Toxic effects of lead exposure on bioaccumulation, oxidative stress, neurotoxicity, and immune responses in fish: A review. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2019, 68, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lentini, P.; Zanoli, L.; de Cal, M.; Granata, A.; Dell’Aquila, R. Lead and Heavy Metals and the Kidney. In Critical Care Nephrology, 3rd ed.; Elsevier: Rome, Italy, 2019; Chapter 222; pp. 1324–1330. [Google Scholar]

- Morosanu, I.; Teodosiu, C.; Paduraru, C.; Ibanescu, D.; Tofan, L. Biosorption of lead ions from aqueous effluents by rapeseed biomass. New Biotechnol. 2017, 39, 110–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blázquez, G.; Calero, M.; Ronda, A.; Tenorio, G.; Martín-Lara, M.A. Study of kinetics in the biosorption of lead onto native and chemically treated olive stone. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2014, 20, 2754–2760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, P.; Diwan, B. Bacterial Exopolysaccharide mediated heavy metal removal: A Review on biosynthesis, mechanism and remediation strategies. Biotechnol. Rep. 2017, 13, 58–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Marghany, A.; Badjah Hadj Ahmed, A.Y.; AlOthman, Z.A.; Sheikh, M.; Ghfar, A.A.; Habila, M. Fabrication of Schiff’s base-functionalized porous carbon materials for the effective removal of toxic metals from wastewater. Arab. J. Geosci. 2021, 14, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alothman, Z.A.; Habila, M.A.; Moshab, M.S.; Al-Qahtani, K.M.; AlMasoud, N.; Al-Senani, G.M.; Al-Kadhi, N.S. Fabrication of renewable palm-pruning leaves based nano-composite for remediation of heavy metals pollution. Arab. J. Chem. 2020, 13, 4936–4944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, V.K.; Rastogi, A. Sorption and desorption studies of chromium(VI) from nonviable cyanobacterium Nostoc muscorum biomass. J. Hazard. Mater. 2008, 154, 347–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, V.K.; Rastogi, A. Biosorption of lead (II) from aqueous solutions by non-living algal biomass Oedogonium sp. and Nostoc sp.−A comparative study. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2008, 64, 170–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fomina, M.; Gadd, G.M. Biosorption: Current perspectives on concept, definition and application. Bioresour. Technol. 2014, 160, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šoštarić, T.D.; Petrović, M.S.; Pastor, F.T.; Lončarević, D.R.; Petrović, J.T.; Milojković, J.V.; Stojanović, M.D. Study of heavy metals biosorption on native and alkali-treated apricot shells and its application in wastewater treatment. J. Mol. Liq. 2018, 259, 340–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, A.; Matsakas, L.; Rova, U.; Christakopoulos, P. Bioresource Technology A perspective on biotechnological applications of thermophilic microalgae and cyanobacteria. Bioresour. Technol. 2019, 278, 424–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulal, D.K.; Loni, P.C.; Dcosta, C.; Some, S.; Kalambate, P.K. Cyanobacteria: As a promising candidate for heavy-metals removal. In Advances in Cyanobacterial Biology; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020; Chapter 19; pp. 291–300. [Google Scholar]

- Bhunia, B.; Shankar, U.; Uday, P.; Oinam, G.; Mondal, A. Characterization, genetic regulation and production of cyanobacterial exopolysaccharides and its applicability for heavy metal removal. Carbohydr. Polym. 2018, 179, 228–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tran, H.T.; Vu, N.D.; Matsukawa, M.; Okajima, M.; Kaneko, T.; Ohki, K.; Yoshikawa, S. Heavy metal biosorption from aqueous solutions by algae inhabiting rice paddies in Vietnam. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2016, 2, 2529–2535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Shu, X.; Wang, W. Biochemical composition, heavy metal content and their geographic variations of the form species Nostoc commune across China. Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 42, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodds, W.K.; Gudder, D.A.; Mollenhauer, D. The ecology of Nostoc. J. Phycol. 1995, 31, 2–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atoku, D.I.; Ojekunle, O.Z.; Taiwo, A.M.; Shittu, O.B. Evaluating the efficiency of Nostoc commune, Oscillatoria limosa and Chlorella vulgaris in a phycoremediation of heavy metals contaminated industrial wastewater. Sci. Afr. 2021, 12, e00817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iddou, A.; Hadj Youcef, M.; Aziz, A.; Ouali, M.S. Biosorptive removal of lead (II) ions from aqueous solutions using Cystoseira stricta biomass: Study of the surface modification effect. J. Saudi Chem. Soc. 2011, 15, 83–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronda, A.; Martín-Lara, M.A.; Almendros, A.I.; Pérez, A.; Blázquez, G. Comparison of two models for the biosorption of Pb(II) using untreated and chemically treated olive stone: Experimental design methodology and adaptive neural fuzzy inference system (ANFIS). J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2015, 54, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, S.C.R.; Ungureanu, G.; Volf, I.; Boaventura, R.A.R.; Botelho, C.M.S. Macroalgae Biomass as Sorbent for Metal Ions. In Biomass as Renewable Raw Material to Obtain Bioproducts of High-Tech Value; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 69–112. [Google Scholar]

- Bulgariu, L.; Bulgariu, D.; Macoveanu, M. Adsorptive Performances of Alkaline Treated Peat for Heavy Metal Removal. Sep. Sci. Technol. 2011, 46, 1023–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulgariu, L.; Bulgariu, D. Enhancing Biosorption Characteristics of Marine Green Algae (Ulva lactuca) for Heavy Metals Removal by Alkaline Treatment. J. Bioprocess. Biotech. 2014, 4, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafar, M.N.; Aslam, I.; Nadeem, R.; Munir, S.; Rana, U.A.; Khan, S.U.D. Characterization of chemically modified biosorbents from rice bran for biosorption of Ni(II). J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2015, 46, 82–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Naggar, N.E.A.; Hamouda, R.A.; Mousa, I.E.; Abdel-Hamid, M.S.; Rabei, N.H. Biosorption optimization, characterization, immobilization and application of Gelidium amansii biomass for complete Pb2+ removal from aqueous solutions. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 13456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrović, M.; Šoštarić, T.; Stojanović, M.; Petrović, J.; Mihajlović, M.; Ćosović, A.; Stanković, S. Mechanism of adsorption of Cu2+ and Zn2+ on the corn silk (Zea mays L.). Ecol. Eng. 2017, 99, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calero, M.; Pérez, A.; Blázquez, G.; Ronda, A.; Martín-lara, M.A. Characterization of chemically modified biosorbents from olive tree pruning for the biosorption of lead. Ecol. Eng. 2013, 58, 344–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morsy, F.M.; Hassan, S.H.A.; Koutb, M. Biosorption of Cd (II) and Zn (II) by Nostoc commune: Isotherm and Kinetics Studies. Clean Soil Air Water 2011, 39, 680–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohki, K.; Le, N.Q.T.; Yoshikawa, S.; Kanesaki, Y.; Okajima, M.; Kaneko, T.; Thi, T.H. Exopolysaccharide production by a unicellular freshwater cyanobacterium Cyanothece sp. isolated from a rice field in Vietnam. J. Appl. Phycol. 2014, 26, 265–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raj, K.; Sardar, U.R.; Bhargavi, E.; Devi, I.; Bhunia, B.; Tiwari, O.N. Advances in exopolysaccharides based bioremediation of heavy metals in soil and water: A critical review. Carbohydr. Polym. 2018, 199, 353–364. [Google Scholar]

- Warjri, S.M.; Syiem, M.B. Analysis of Biosorption Parameters, Equilibrium Isotherms and Thermodynamic Studies of Chromium (VI) Uptake by a Nostoc sp. Isolated from a Coal Mining Site in Meghalaya, India. Mine Water Environ. 2018, 37, 713–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, L.; Jun, B.M.; Flora, J.R.V.; Park, C.M.; Yoon, Y. Removal of heavy metals from water sources in the developing world using low-cost materials: A review. Chemosphere 2019, 229, 142–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, W.M. Biosorption of heavy metal ions from aqueous solution by red macroalgae. J Hazard Mater. 2011, 192, 1827–1835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, D.H.K.; Harinath, Y.; Seshaiah, K.; Reddy, A.V.R. Biosorption of Pb(II) from aqueous solutions using chemically modified Moringa oleifera tree leaves. Chem. Eng. J. 2010, 162, 626–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangwandi, C.; Kurniawan, T.A.; Albadarin, A.B. Comparative biosorption of chromium (VI) using chemically modified date pits (CM-DP) and olive stone (CM-OS): Kinetics, isotherms and influence of co-existing ions. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2020, 56, 251–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijayaraghavan, J.; Pushpa, T.B.; Basha, S.J.S.; Jegan, J.; Pushpa, T.B.; Basha, S.J.S. Isotherm, kinetics and mechanistic studies of methylene blue biosorption onto red seaweed Gracilaria corticata. Desalination Water Treat. 2015, 57, 13540–13548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albadarin, A.B.; Solomon, S.; Daher, M.A.; Walker, G. Efficient removal of anionic and cationic dyes from aqueous systems using spent Yerba Mate “Ilex paraguariensis”. J. Taiwan Inst. 2018, 82, 144–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, G.C.; Hoque, M.I.U.; Miah, M.A.M.; Holze, R.; Chowdhury, D.A.; Khandaker, S.; Chowdhury, S. Biosorptive removal of lead from aqueous solutions onto Taro (Colocasiaesculenta (L.) Schott) as a low cost bioadsorbent: Characterization, equilibria, kinetics and biosorption-mechanism studies. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2017, 5, 2151–2162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taşar, Ş.; Kaya, F.; Özer, A. Biosorption of lead(II) ions from aqueous solution by peanut shells: Equilibrium, thermodynamic and kinetic studies. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2014, 2, 1018–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elwakeel, K.Z.; Elgarahy, A.M.; Mohammad, S.H. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering Use of beach bivalve shells located at Port Said coast (Egypt) as a green approach for methylene blue removal. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2017, 5, 578–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koyuncu, H.; Kul, A.R. Biosorption study for removal of methylene blue dye from aqueous solution using a novel activated carbon obtained from nonliving lichen (Pseudevernia furfuracea (L.) Zopf.). Surf. Interfaces 2020, 19, 100527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, S.; Agrawal, S.B.; Mondal, M.K. Biosorption isotherms and kinetics on removal of Cr(VI) using native and chemically modified Lagerstroemia speciosa bark. Ecol. Eng. 2015, 85, 56–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkhaleefa, A.; Ali, I.H.; Brima, E.I.; Shigidi, I.; Elhag, A.B.; Karama, B. Evaluation of the adsorption efficiency on the removal of lead(II) ions from aqueous solutions using Azadirachta indica leaves as an adsorbent. Processes 2021, 9, 559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebron, Y.A.R.; Moreira, V.R.; Santos, L.V.S.; Jacob, R.S. Remediation of methylene blue from aqueous solution by Chlorella pyrenoidosa and Spirulina maxima biosorption: Equilibrium, kinetics, thermodynamics and optimization studies. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2018, 6, 6680–6690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo, C.S.T.; Almeida, I.L.S.; Rezende, H.C.; Marcionilio, S.M.L.O.; Léon, J.J.L.; de Matos, T.N. Elucidation of mechanism involved in adsorption of Pb(II) onto lobeira fruit (Solanum lycocarpum) using Langmuir, Freundlich and Temkin isotherms. Microchem. J. 2018, 137, 348–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guyo, U.; Mhonyera, J.; Moyo, M. Pb(II) adsorption from aqueous solutions by raw and treated biomass of maize stover—A comparative study. Process. Saf. Environ. Prot. 2015, 93, 192–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, H.; Yu, Z. Adsorption of Pb(II) onto Modified Rice Bran. Nat. Resour. 2010, 01, 104–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moyo, M.; Pakade, V.E.; Modise, S.J. Biosorption of lead(II) by chemically modified Mangifera indica seed shells: Adsorbent preparation, characterization and performance assessment. Process. Saf. Environ. Prot. 2017, 111, 40–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, N.F.; Lima, E.C.; Royer, B.; Bach, M.V.; Dotto, G.L.; Pinto, L.A.A.; Calvete, T. Comparison of Spirulina platensis microalgae and commercial activated carbon as adsorbents for the removal of Reactive Red 120 dye from aqueous effluents. J. Hazard. Mater. 2012, 241–242, 146–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bangaraiah, P.; Peele, K.A.; Venkateswarulu, T.C. Removal of lead from aqueous solution using chemically modified green algae as biosorbent: Optimization and kinetics study. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 18, 317–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do Nascimento, J.M.; de Oliveira, J.D.; Leite, S.G.F. Chemical characterization of biomass flour of the babassu coconut mesocarp (Orbignya speciosa) during biosorption process of copper ions. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2019, 16, 100440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, K.L.; Hameed, B.H. Insight into the adsorption kinetics models for the removal of contaminants from aqueous solutions. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2017, 74, 25–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayak, A.K.; Pal, A. Green and ef fi cient biosorptive removal of methylene blue by Abelmoschus esculentus seed: Process optimization and multi-variate modeling. J. Environ. Manag. 2017, 200, 145–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Biomass | Acidic Sites (mmol g−1) | Basic Sites (mmol g−1) |

|---|---|---|

| Untreated, NC | 0.52 | 0.02 |

| Treated, NCM | 0.38 | 0.11 |

| Model | Parameters | NCM Biosorbent |

|---|---|---|

| Pseudo first-order | qe,cal (mg g−1) (a) | 5.34 |

| k1 (min−1) | 0.041 | |

| R2 | 0.6 | |

| Pseudo second-order | qe,cal (mg g−1) (a) | 384.6 |

| k2 (g mg−1⋅min−1) | 0.0042 | |

| h (mg g−1⋅min−1) | 624.99 | |

| R2 | 1 | |

| Elovich | (g mg−1) | 0.16 |

| α ×106 (mg g−1·min−1) | 4.27 | |

| R2 | 0.8 | |

| Intra-particle diffusion | kid, I (mg g−1·min−1/2) | 115.9 |

| BI | 7.25 | |

| R2 | 0.99 | |

| kid, II (mg g−1·min−1/2) | 7.4 | |

| BII | 332.84 | |

| R2 | 1 | |

| kid, III (mg g−1·min−1/2) | 0.3 | |

| BIII | 372.23 | |

| R2 | 0.81 |

| pH | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Model | Parameters | 4.5 | 5.5 |

| Langmuir | qmax (mg g−1) (a) | 384.6 | 384.6 |

| KL (L mg−1) | 0.12 | 0.13 | |

|

R2 χ2 | 0.99 1.6 | 0.99 7.6 | |

| Freundlich | n | 7.7 | 9.1 |

| KF (mg L1/n g−1 mg−1/n) | 178.5 | 200.4 | |

| R2 χ2 | 0.99 0.6 | 0.98 1.5 | |

| Dubinin–Radushkevich (D–R) | BDR (mol2 kJ−2) | 2 × 10−8 | 7 × 10−8 |

| qmax (mg g−1) (a) | 327.3 | 309.3 | |

| E (kJ mol−1) | 500 | 2673 | |

|

R2 χ2 | 0.67 34.8 | 0.67 36.3 | |

| Temkin |

B (J mol−1) KT (Lg−1) R2 χ2 | 75.3 256.16 0.96 2.27 | 89.6 217.41 0.93 4.51 |

| Biomass | Treatment | qe,max (mg·g−1) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Algae Nostoc sp Algae Oedogonium sp | Non Non | 93.5 145.0 | Gupta & Rastogi [9] |

| Algae Cystoseira stricta | NaOH | 65 | Iddou et al. [19] |

| Olive Stone | NaOH NaOH | 15 ≤25.48 | Blázquez et al. [4] Ronda et al. [20] |

| Maize stover | HNO3 | 27.1 | Guyo et al. [46] |

| Rice bran | NaOH | 78.9 | Ye and Yu [47] |

| Mangifera indica seed shells | NaOH Carboxyl functionalized | 59.25 306.33 | Moyo et al. [48] |

| Moringa oleifera tree leaves | NaOH | 209.554 | Reddy et al. [34] |

| Nostoc commune | NaOH | 384.6 | This work |

| ∆Ho (kJ mol−1) | ∆So (J mol−1 K−1) | ∆Go (kJ mol−1) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 293 K | 303K | 313K | ||

| −65.1 | −200.8 | −6.5 | −3.7 | −2.5 |

| Metal Concentration (mg L−1) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pb | Ca | K | Na | |

| Untreated wastewater | 5.85 | 125.92 | 50.35 | 40.32 |

| Treated wastewater | 0.12 | 45.84 | 45.29 | 40.14 |

| removal efficiency, % R | 97.9 | 63.6 | 10.0 | 0.4 |

| Model | Equation | Parameters |

|---|---|---|

| Kinetic model | ||

| Pseudo-first order | qe: adsorption capacity at equilibrium qt: amount of Pb(II) retained per unit mass of biosorbent at time t. k1: the first-order kinetic constant k2: rate constant adsorption h: initial adsorption rate | |

| Pseudo-second order | ||

| Elovich | ∝: rate constant β: constant related to the covered surface and the activation energy by chemisorption | |

| Intra-particle diffusion | kid: intraparticle diffusion rate constant c: constant | |

| Isotherms | ||

| Langmuir | Ce: adsorbate concentration at equilibrium qmax: Langmuir constant related to the maximum biosorption capacity KL: Langmuir constant related to the affinity between sorbent and sorbate | |

| Freundlich | KF: equilibrium constant n: constant related to the affinity between sorbent and sorbate. | |

| Dubinin–Radushkevich (D–R) | ΒDR: constant related to adsorption energy ε: Polanyi potential | |

| Temkin | R: universal gas constant T: temperature : Temkin’s equilibrium constant B: adsorption energy variation |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lavado-Meza, C.; De la Cruz-Cerrón, L.; Lavado-Puente, C.; Angeles-Suazo, J.; Dávalos-Prado, J.Z. Efficient Lead Pb(II) Removal with Chemically Modified Nostoc commune Biomass. Molecules 2023, 28, 268. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules28010268

Lavado-Meza C, De la Cruz-Cerrón L, Lavado-Puente C, Angeles-Suazo J, Dávalos-Prado JZ. Efficient Lead Pb(II) Removal with Chemically Modified Nostoc commune Biomass. Molecules. 2023; 28(1):268. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules28010268

Chicago/Turabian StyleLavado-Meza, Carmencita, Leonel De la Cruz-Cerrón, Carmen Lavado-Puente, Julio Angeles-Suazo, and Juan Z. Dávalos-Prado. 2023. "Efficient Lead Pb(II) Removal with Chemically Modified Nostoc commune Biomass" Molecules 28, no. 1: 268. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules28010268

APA StyleLavado-Meza, C., De la Cruz-Cerrón, L., Lavado-Puente, C., Angeles-Suazo, J., & Dávalos-Prado, J. Z. (2023). Efficient Lead Pb(II) Removal with Chemically Modified Nostoc commune Biomass. Molecules, 28(1), 268. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules28010268