Imine- and Amine-Type Macrocycles Derived from Chiral Diamines and Aromatic Dialdehydes

Abstract

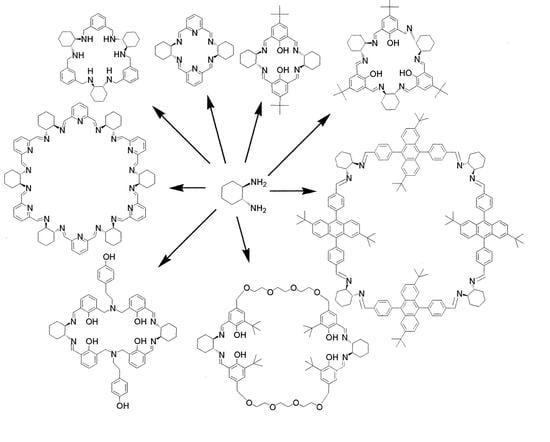

1. Introduction

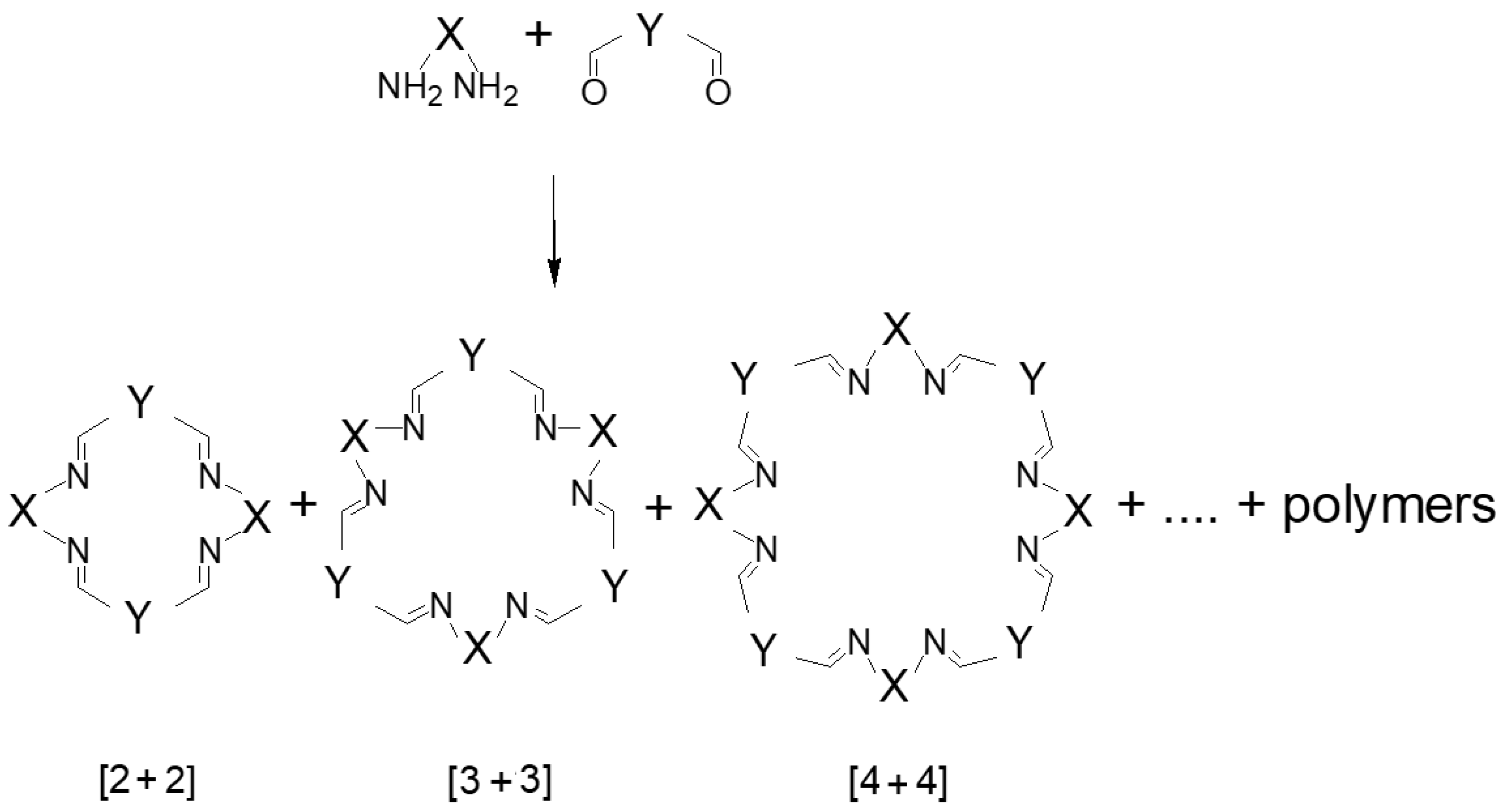

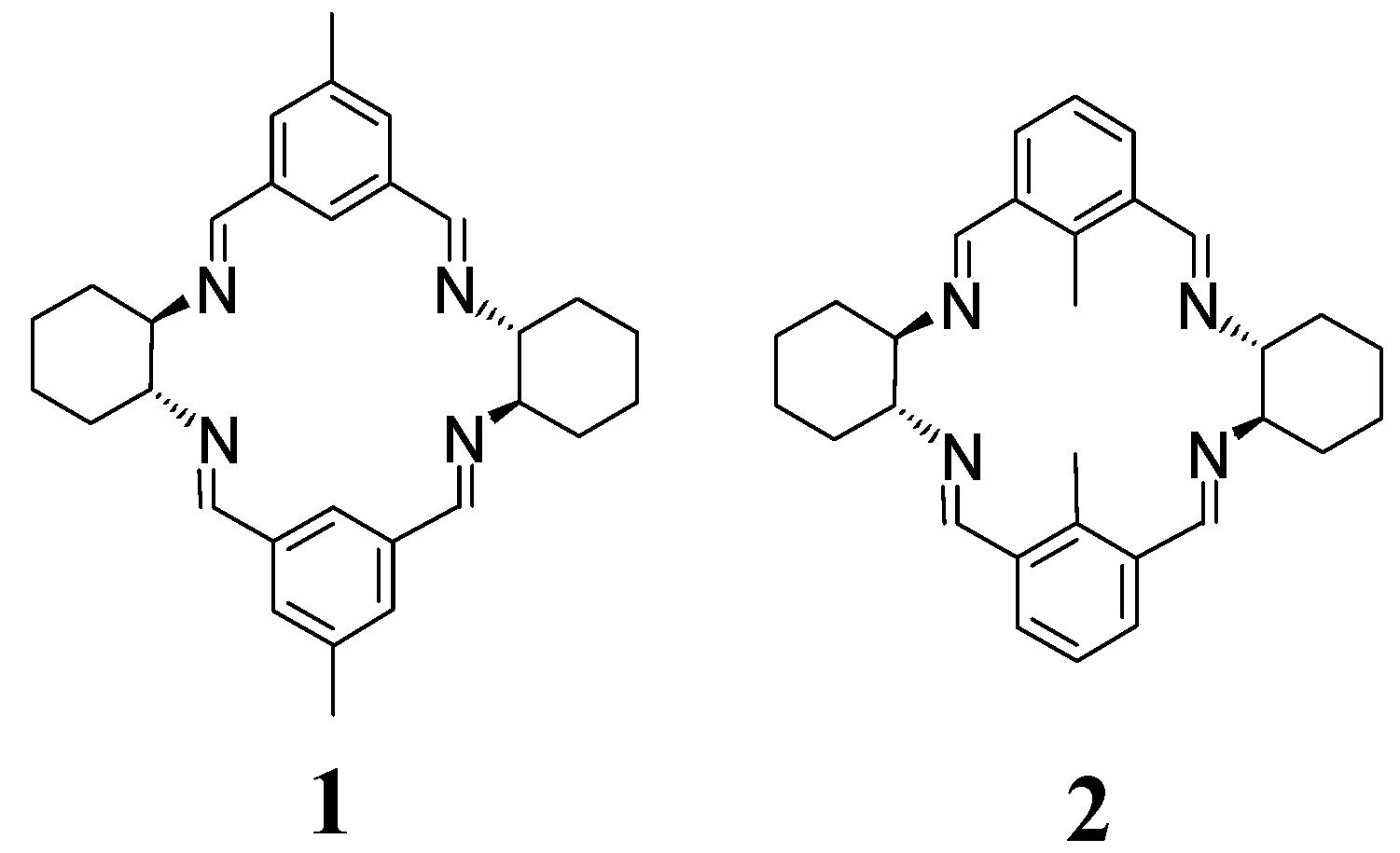

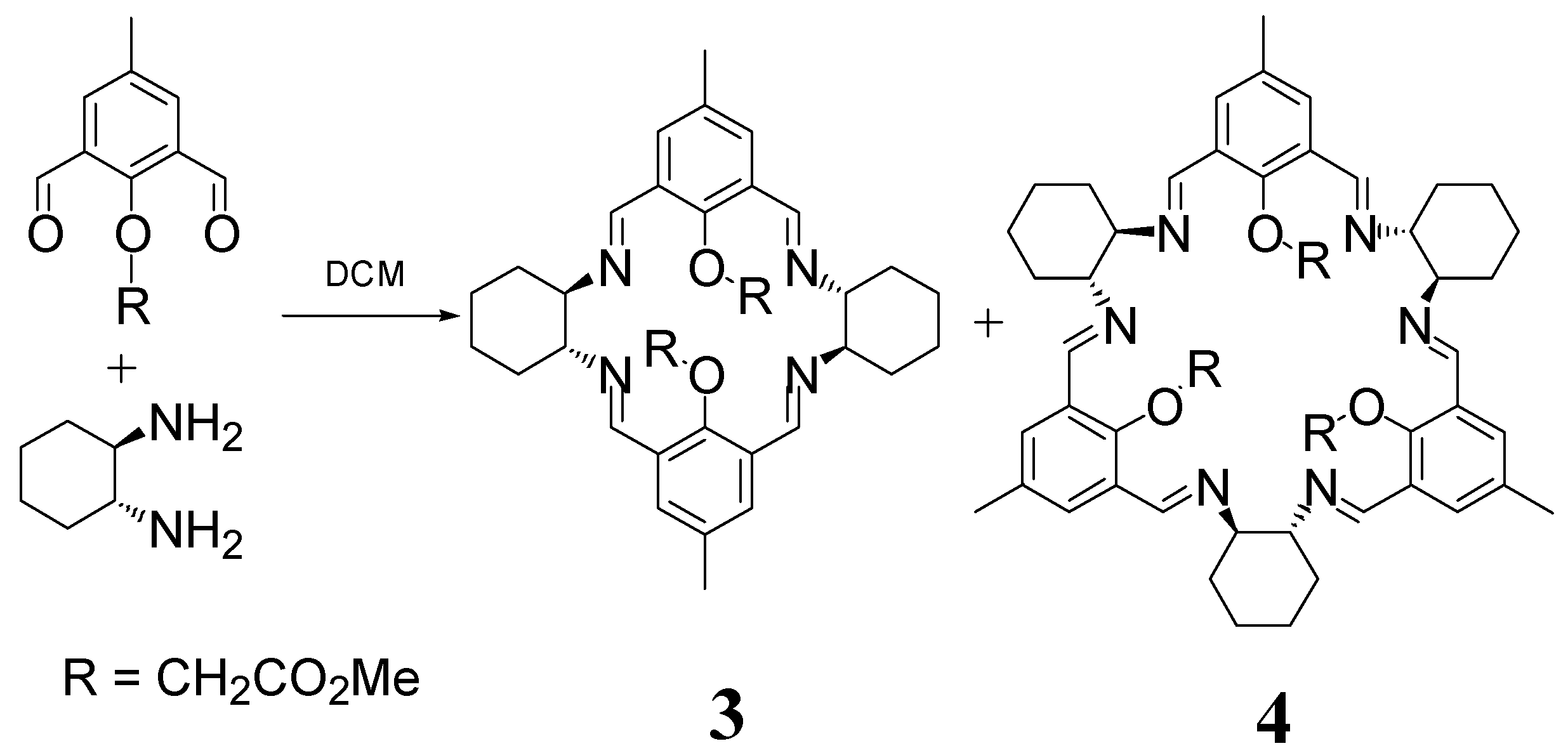

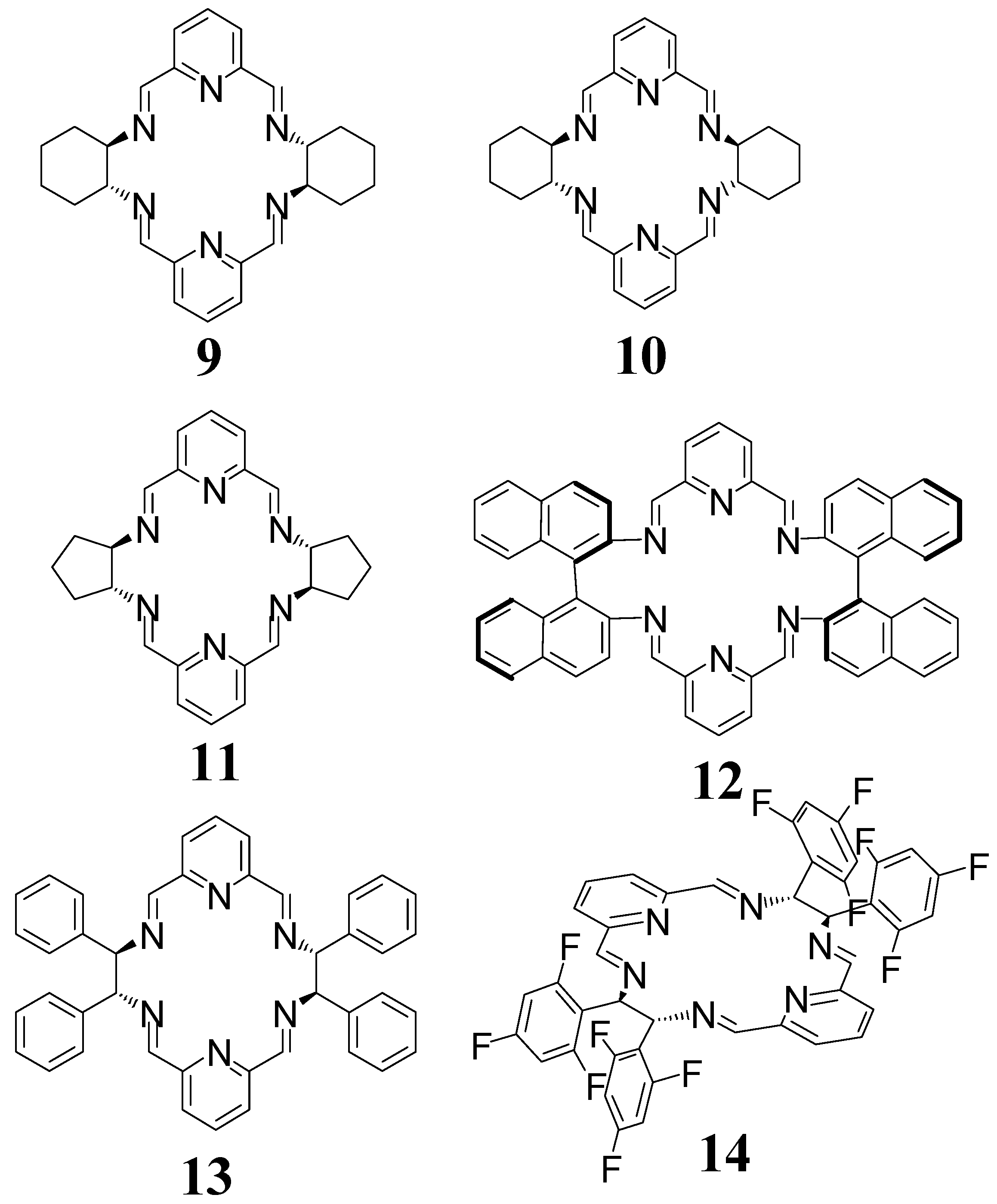

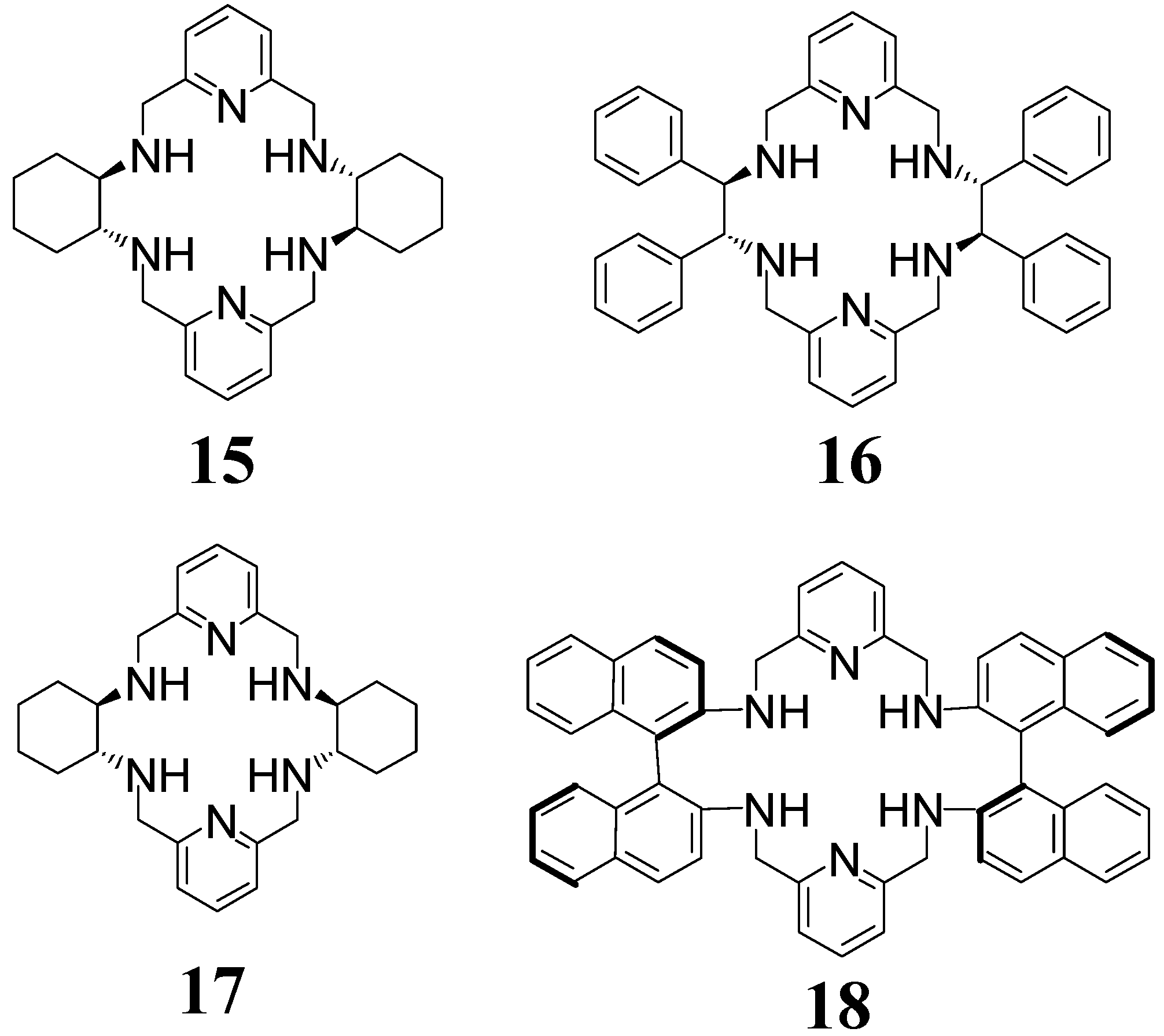

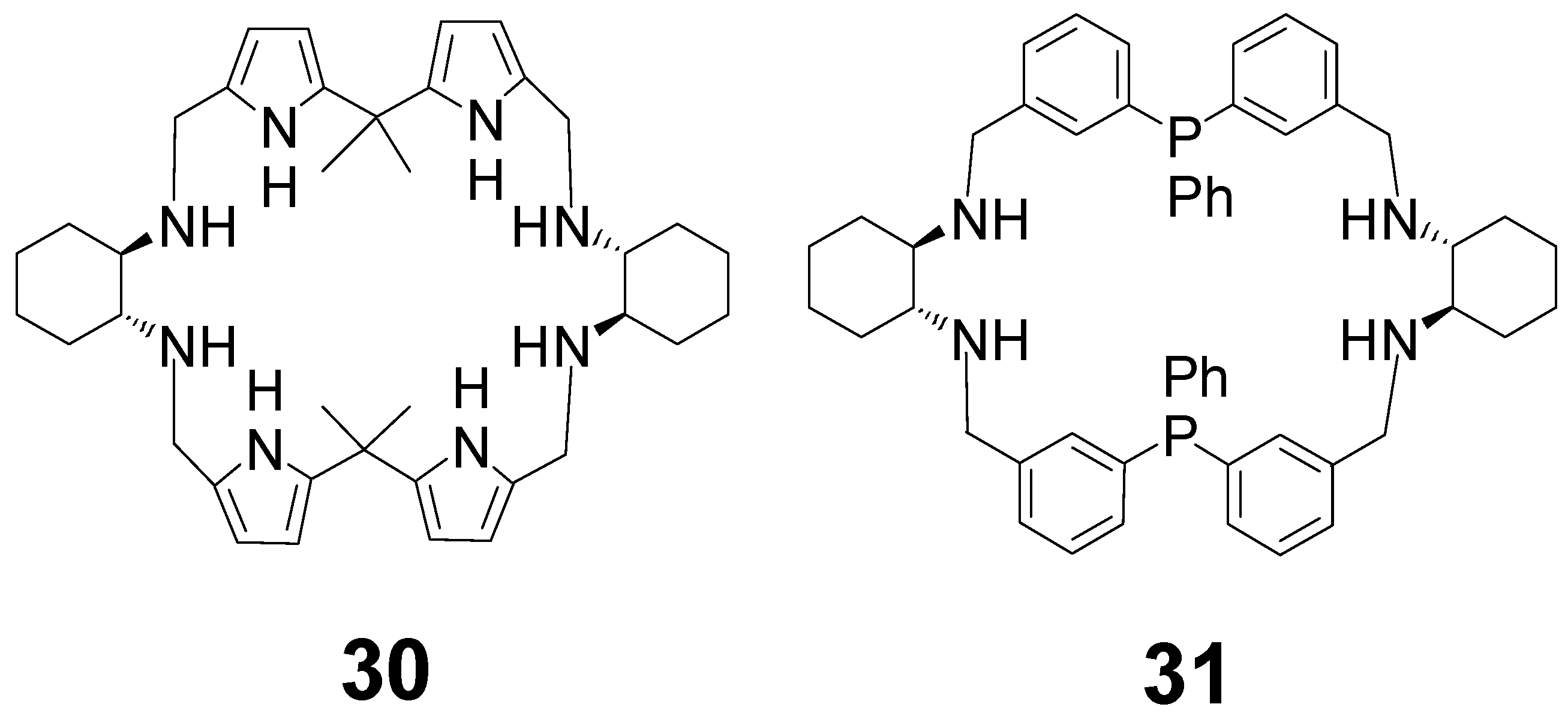

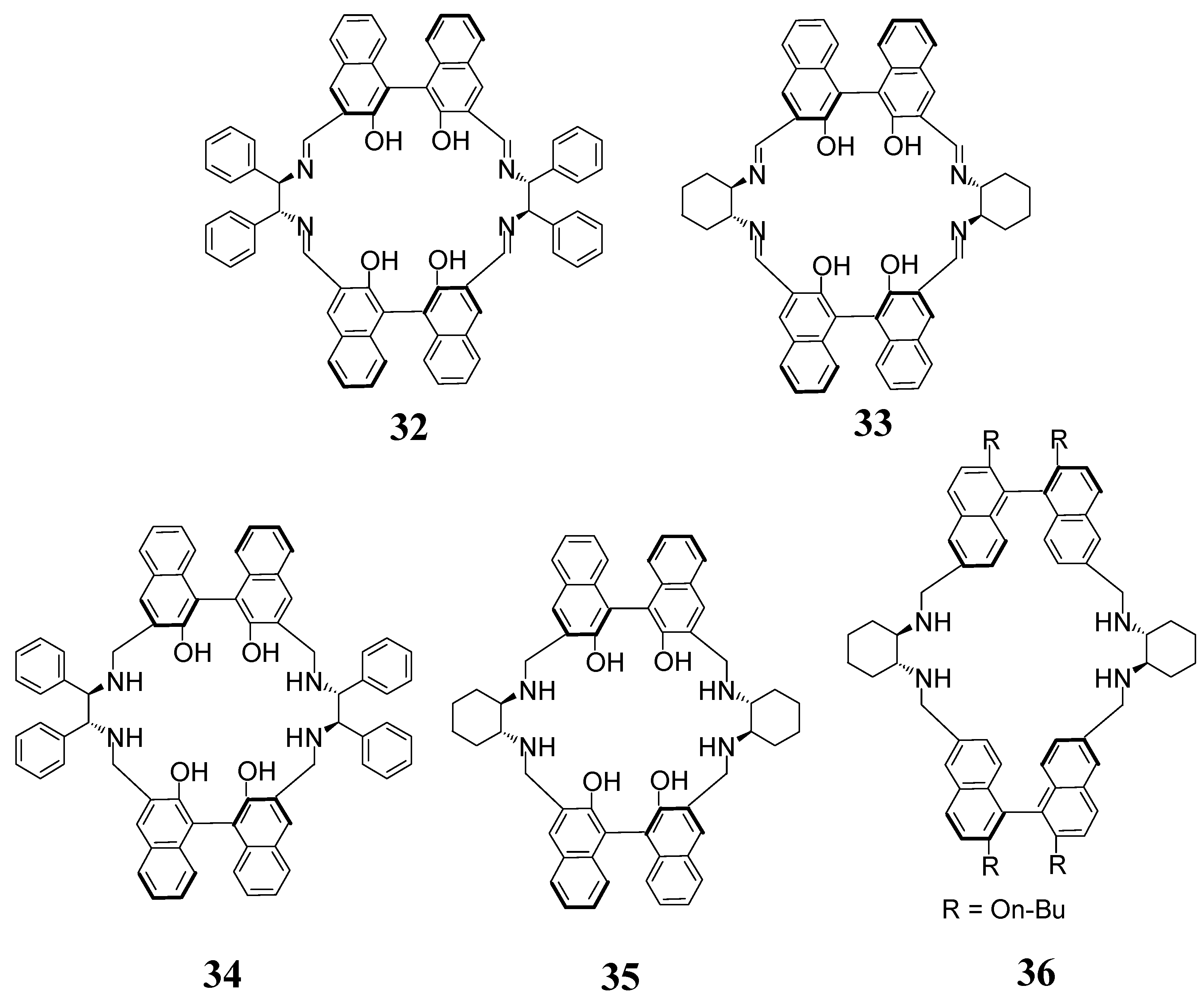

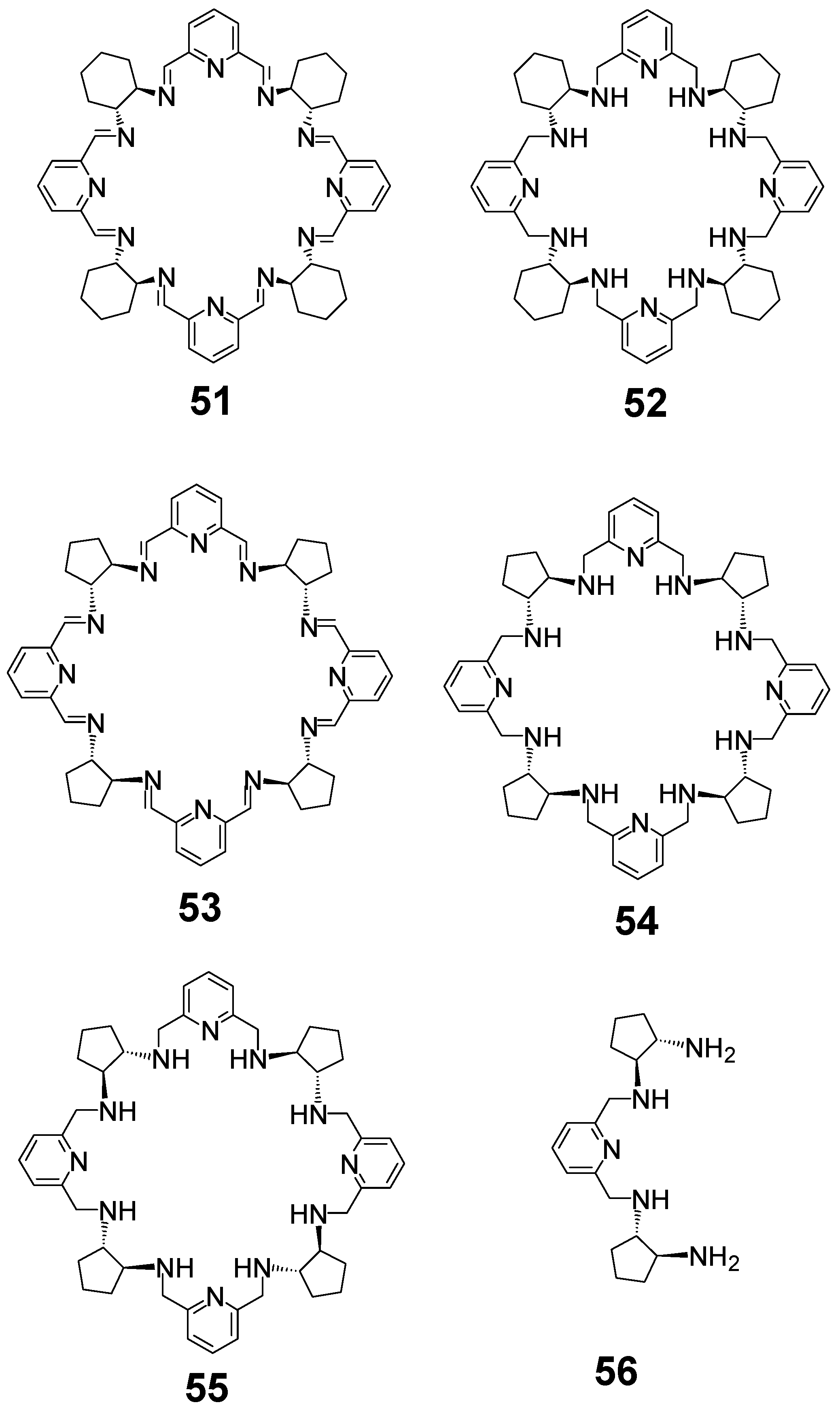

2. [2 + 2] Macrocycles

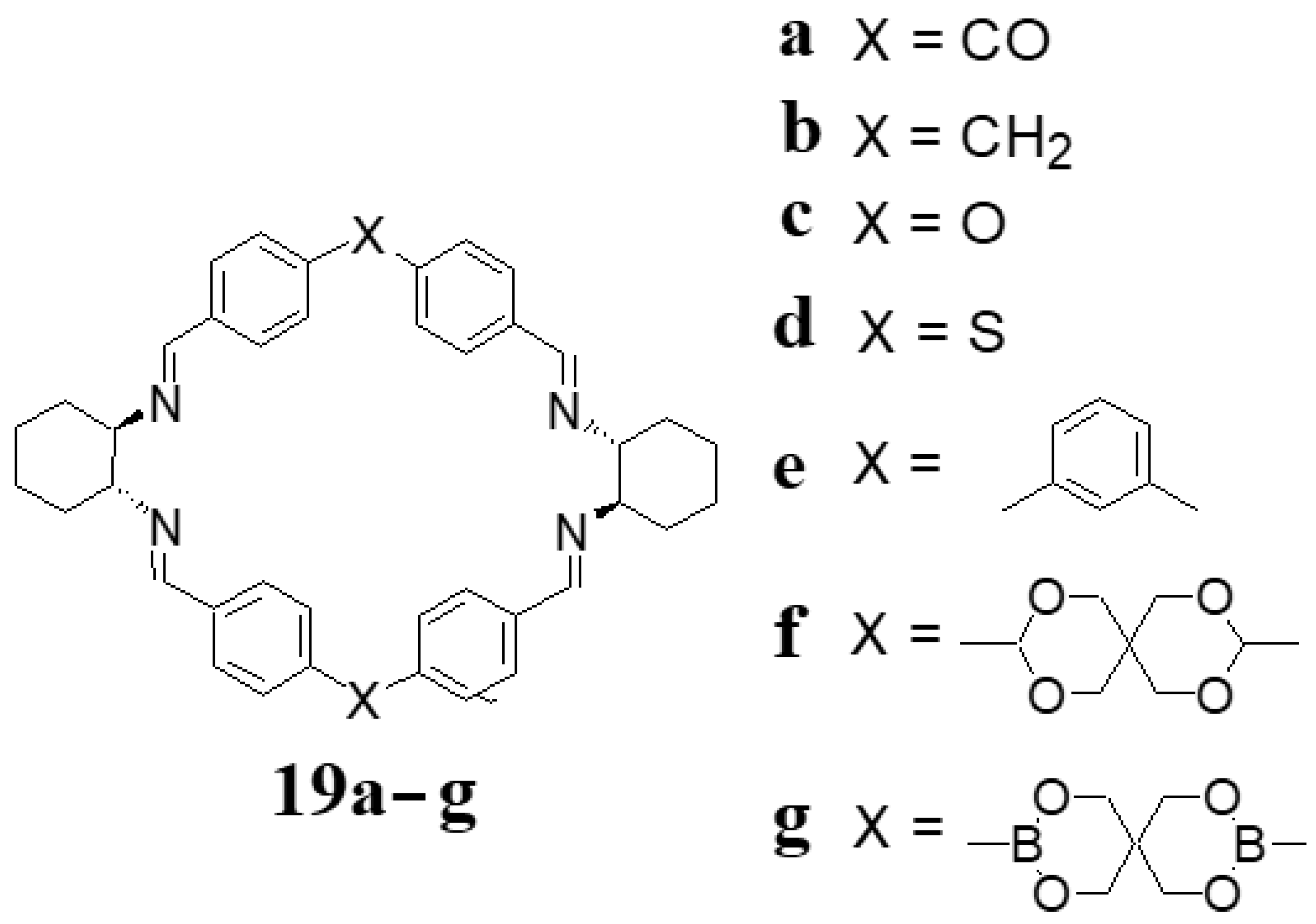

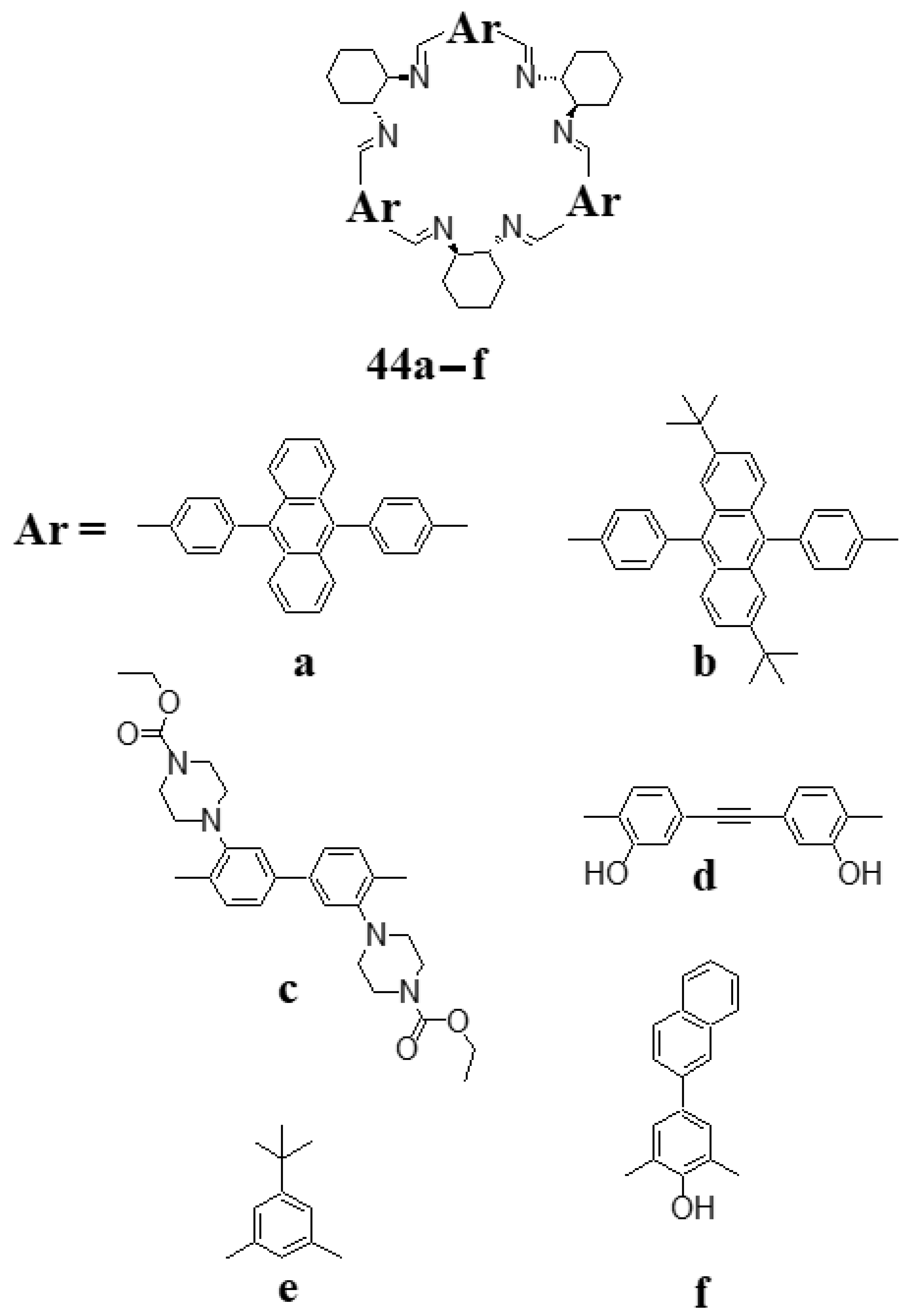

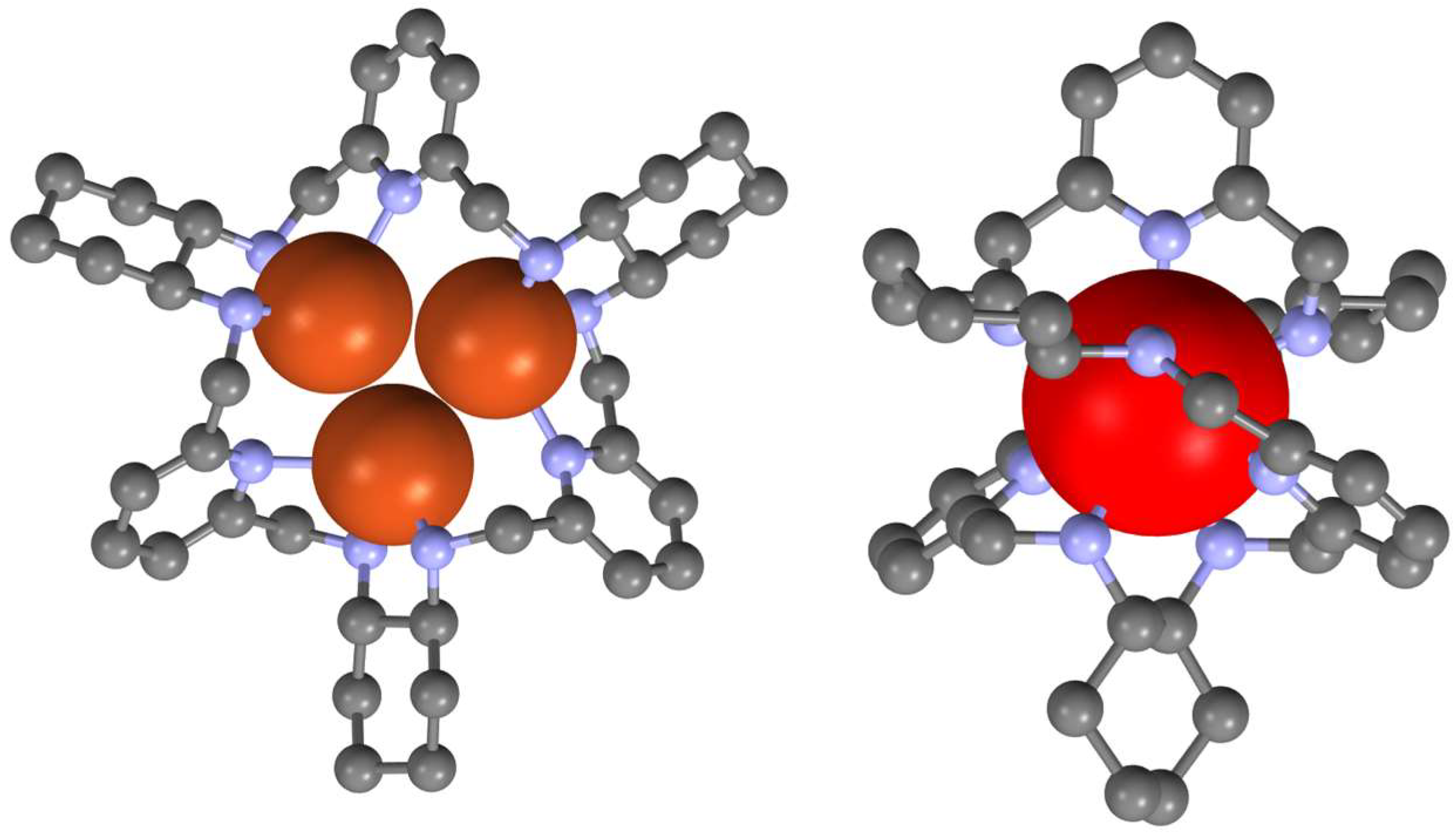

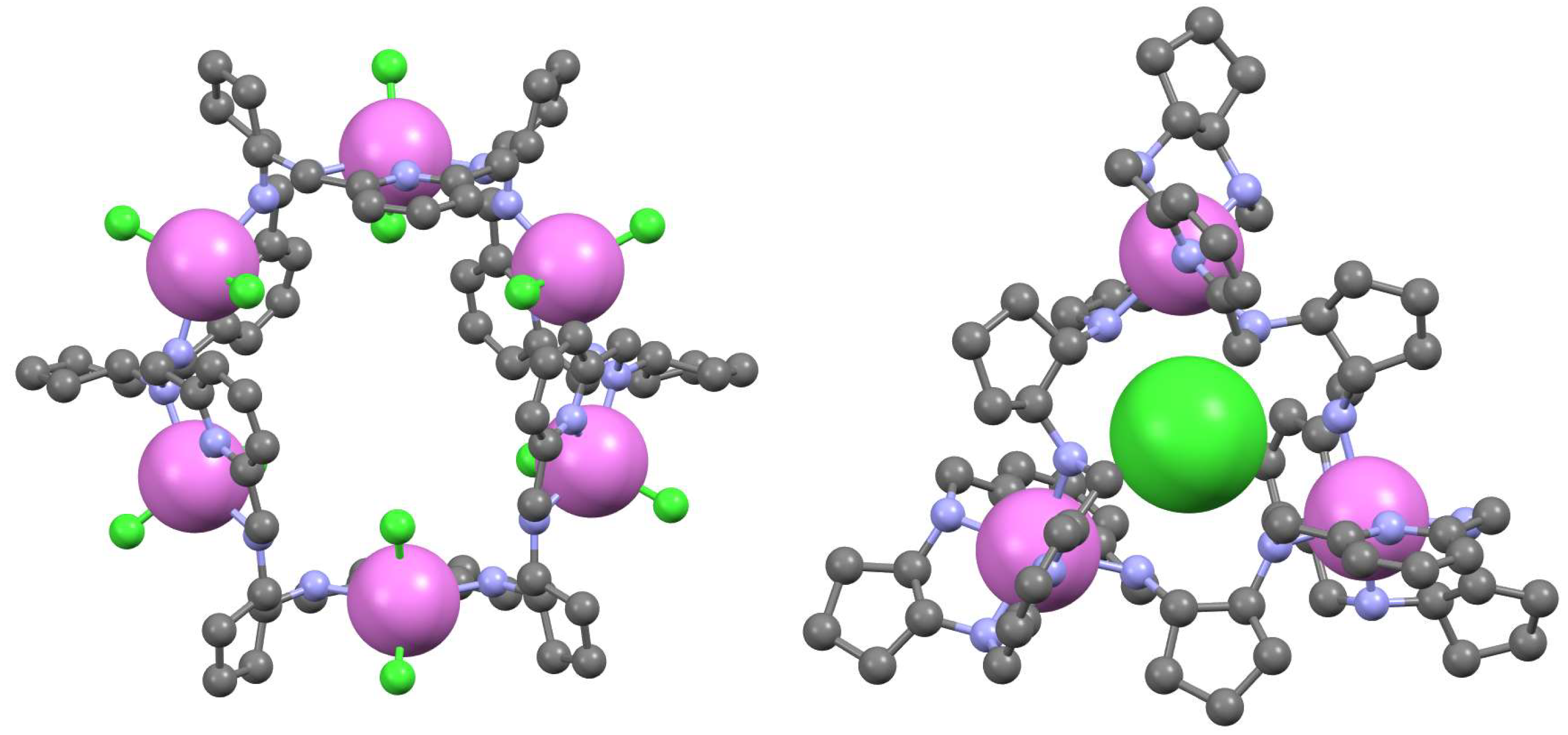

3. [3 + 3] Macrocycles

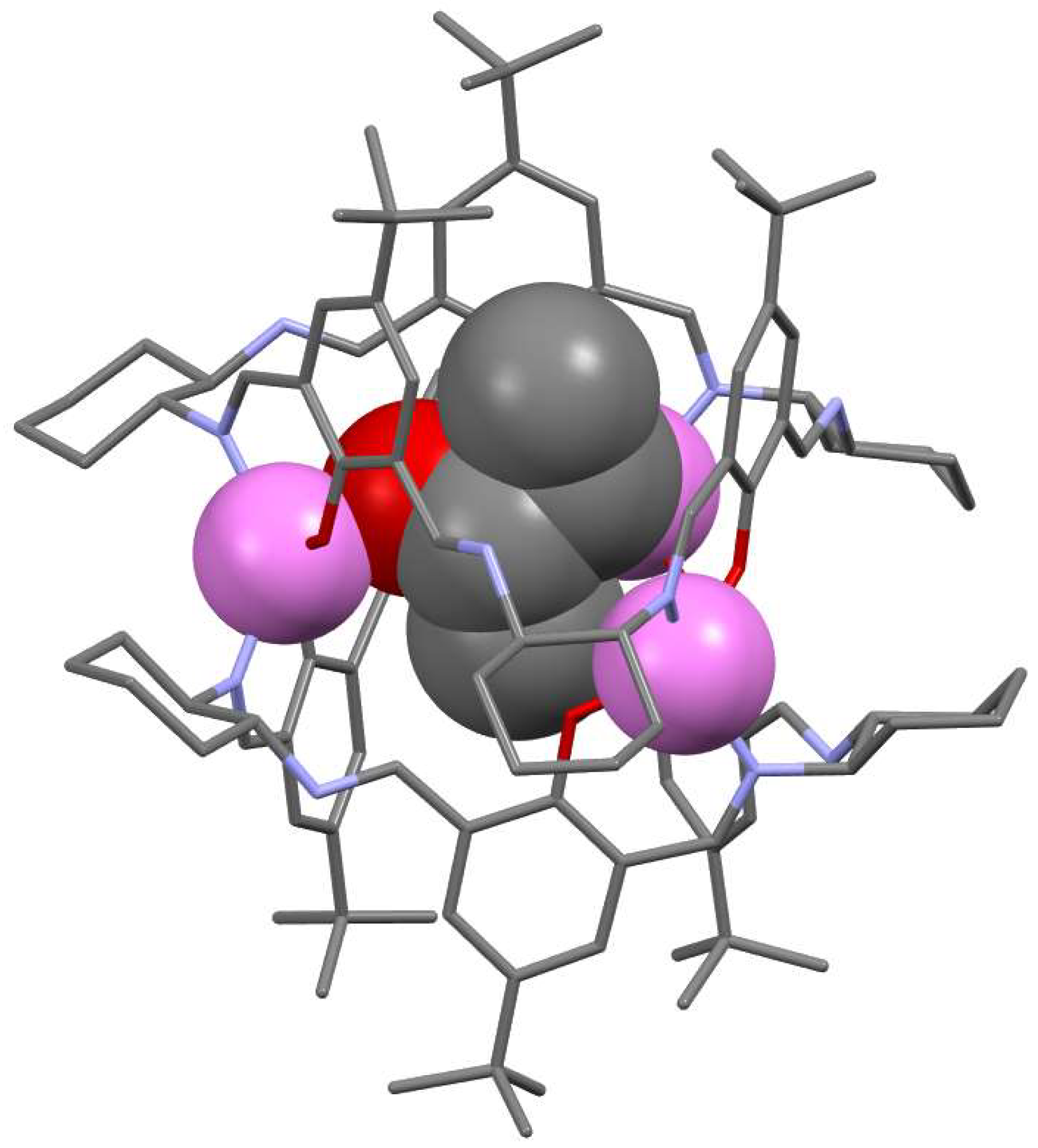

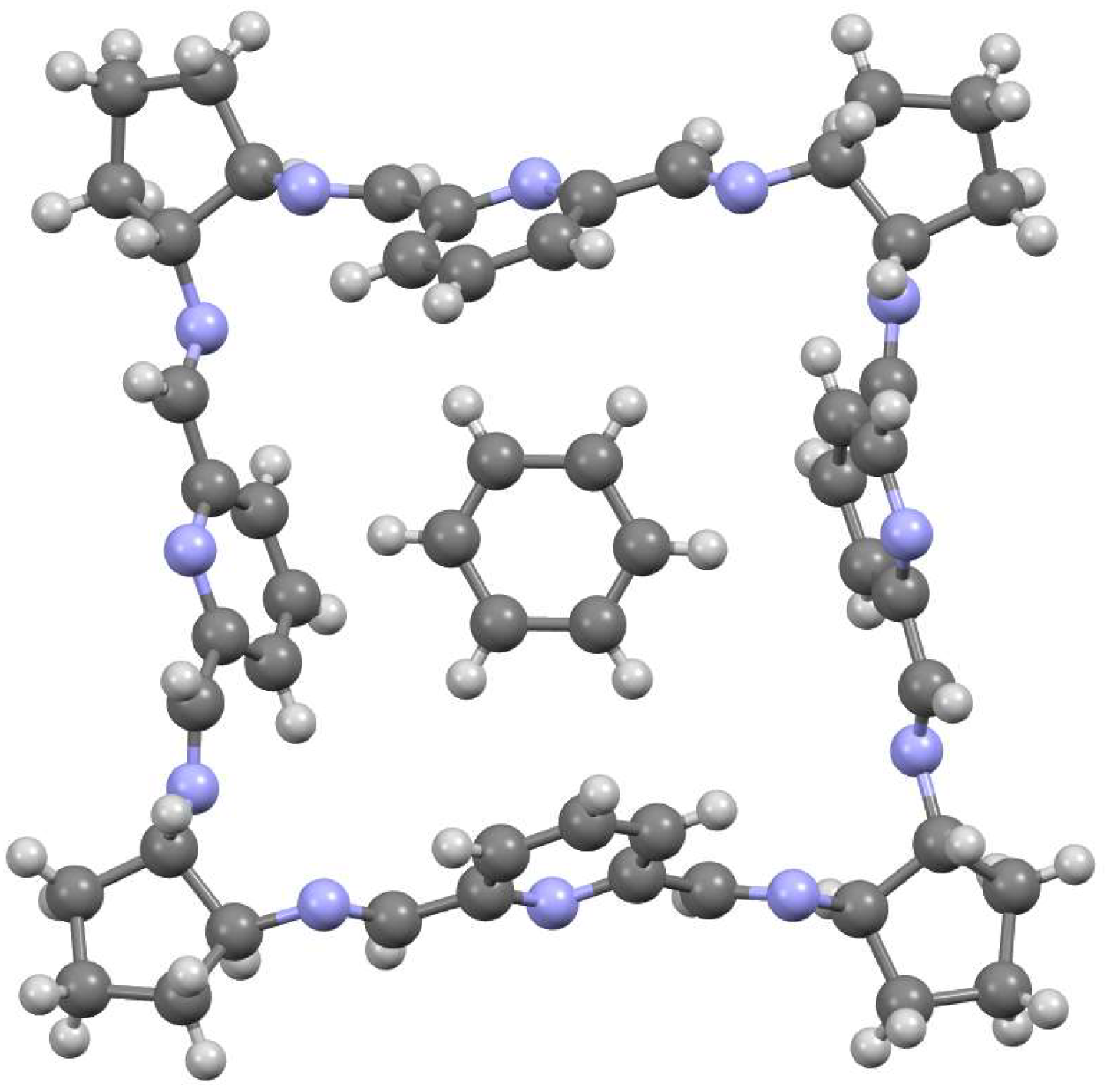

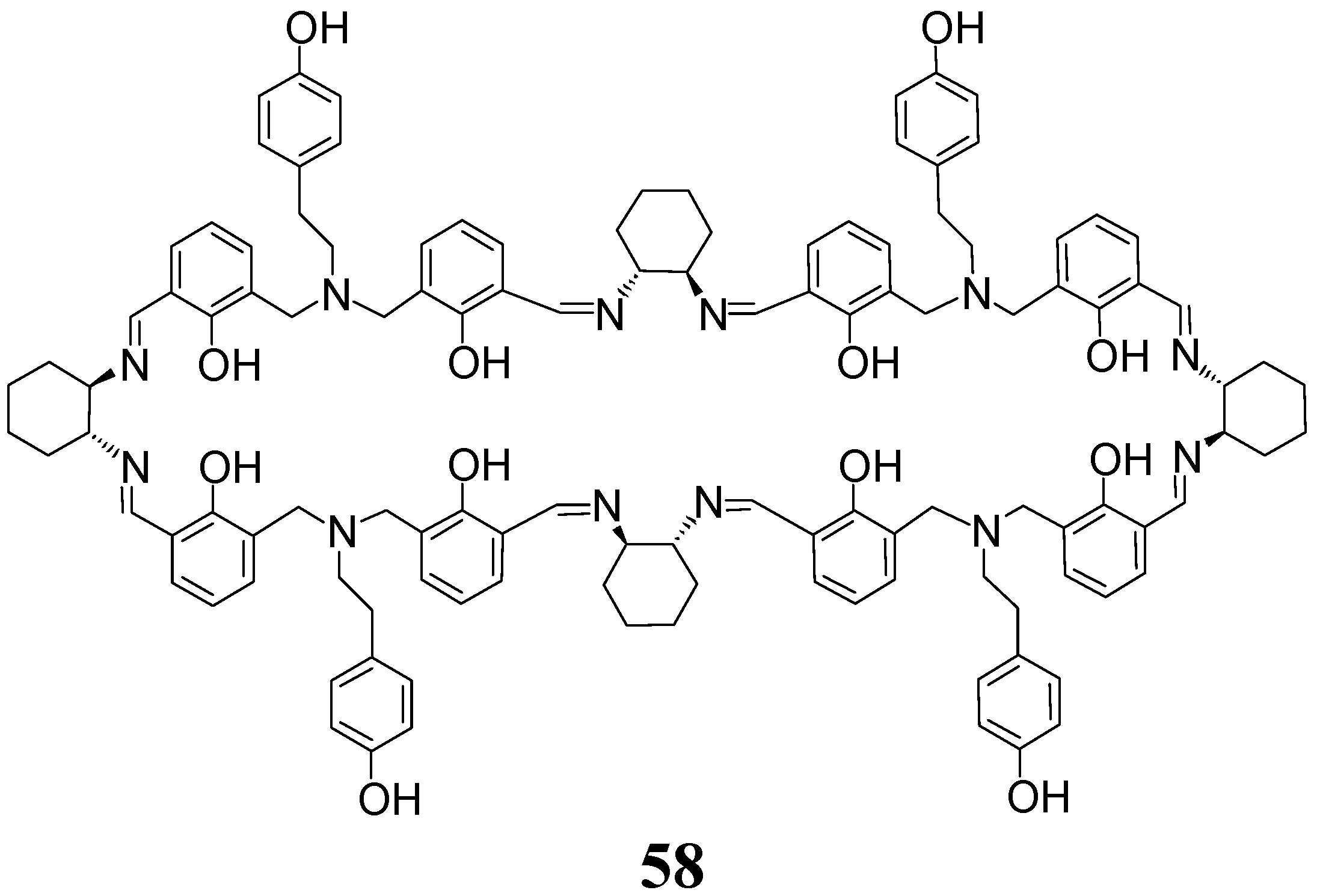

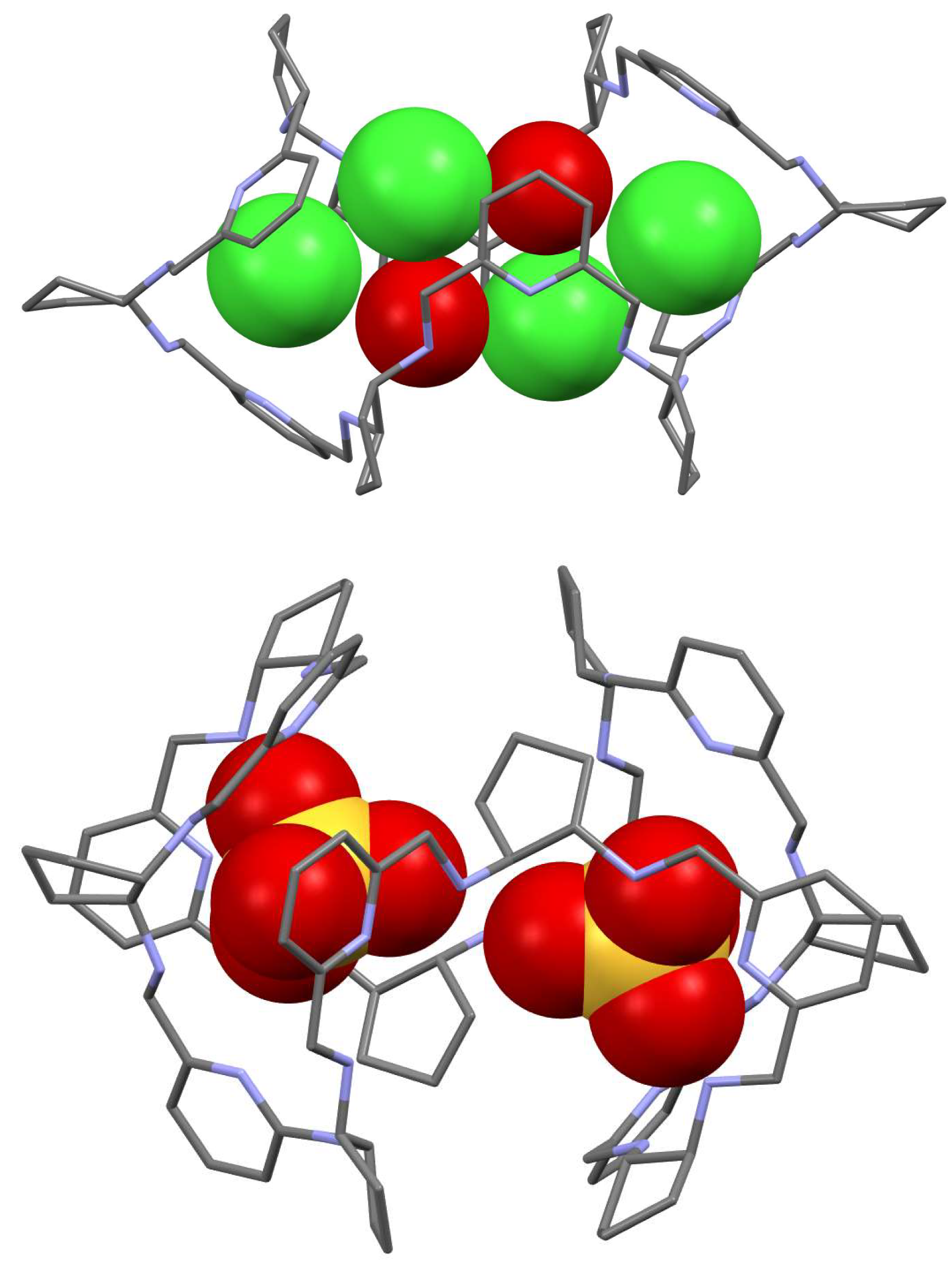

4. [4 + 4] Macrocycles

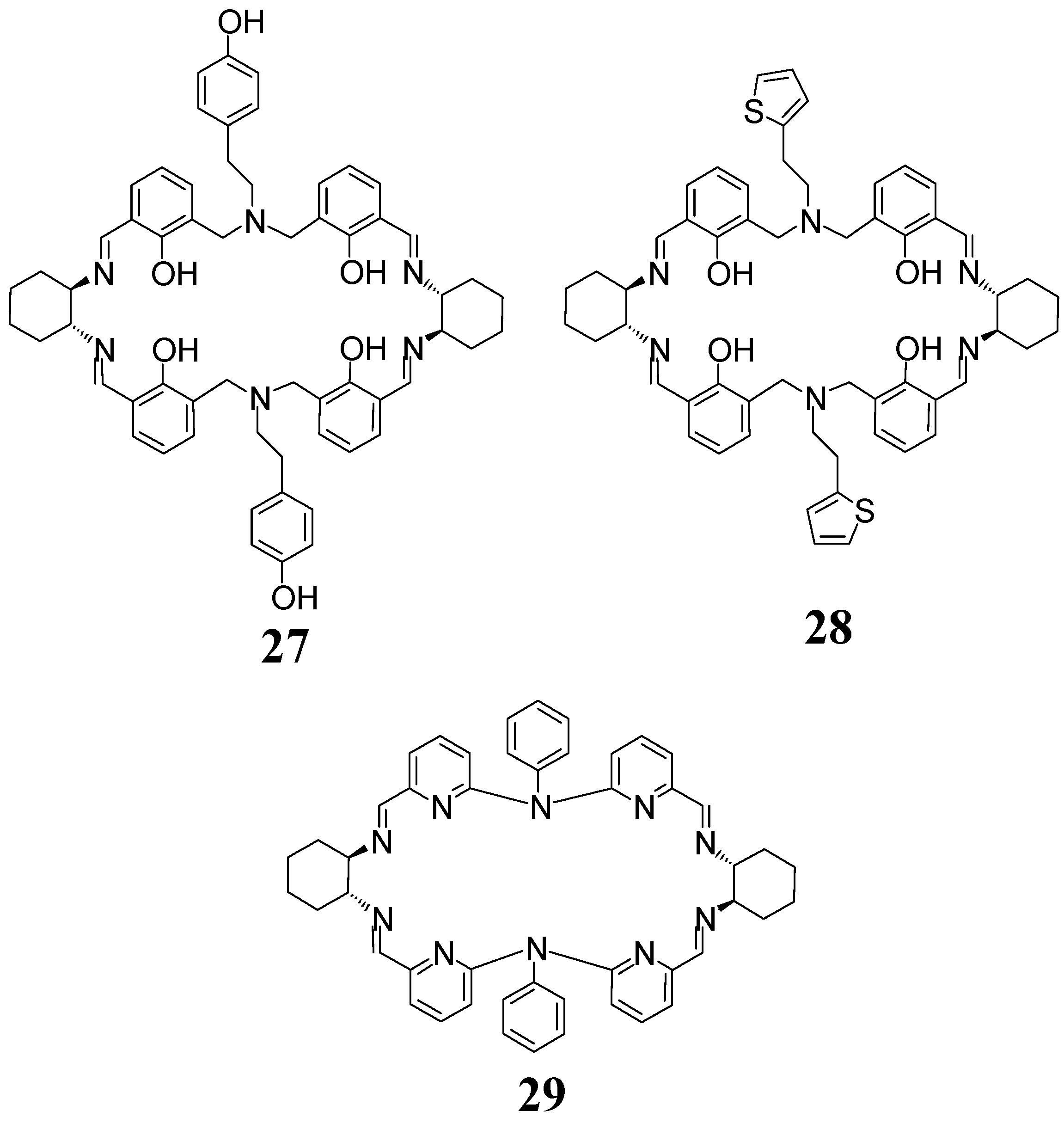

5. [6 + 6] and [8 + 8] Macrocycles

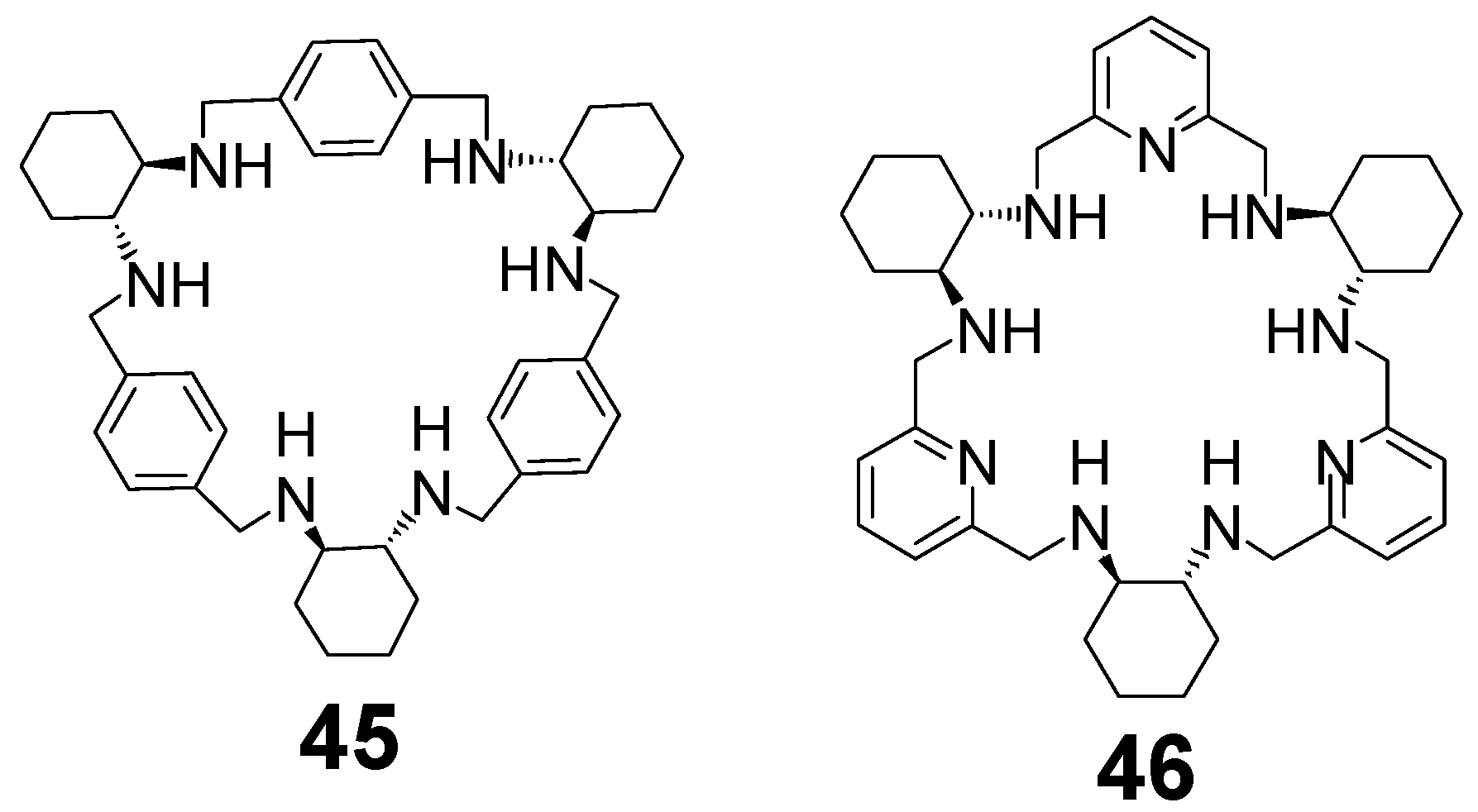

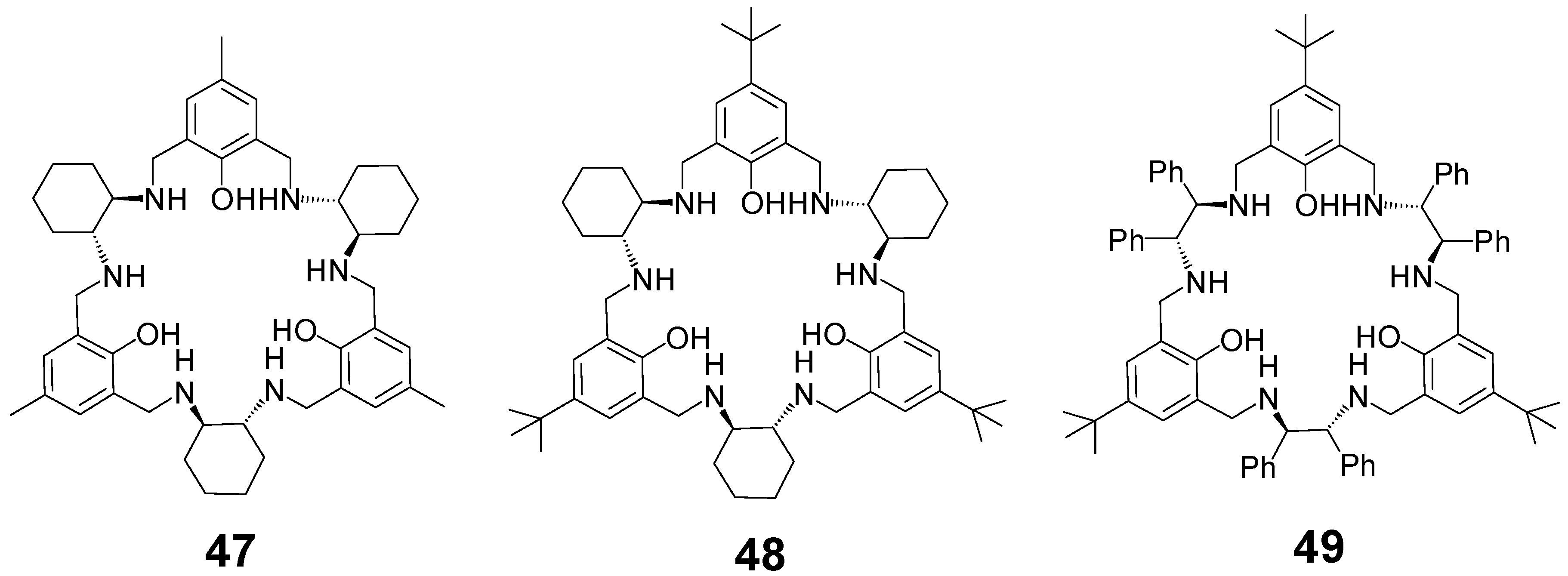

6. Macrocycles Containing Different Diamine Fragments

7. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DACH | 1,2-trans-diaminocyclohexane |

| DPEN | 1,2-diphenylethylenediamine |

| DCAP | trans-1,2-diaminocyclopentane |

| DFP | 2,6-diformylpyridine |

| SMM | Single Molecule Magnet |

References

- Lindoy, L.F.; Park, K.-M.; Lee, S.S. Metals, macrocycles and molecular assemblies-macrocyclic complexes in metallo-supramolecular chemistry. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013, 42, 1713–1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Nalluri, S.K.M.; Stoddart, J.F. Surveying macrocyclic chemistry: From flexible crown ethers to rigid cyclophanes. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2017, 46, 2459–2478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaeivala, M.; Keypour, H. Schiff base and non-Schiff base macrocyclic ligands and complexes incorporating the pyridine moiety–The first 50 years. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2014, 280, 203–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marti-Centelles, V.; Pandey, M.D.; Burguete, M.I.; Luis, S.V. Macrocyclization Reactions: The Importance of Conformational, Configurational, and Template-Induced Preorganization. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 8736–8834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alfonso, I. Chiral Molecular Receptors Based on Trans-Cyclohexane-1,2-diamine. Curr. Org. Synth. 2010, 7, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borisova, N.E.; Reshetova, M.D.; Ustynyuk, Y.A. Metal-Free Methods in the Synthesis of Macrocyclic Schiff Bases. Chem. Rev. 2007, 107, 46–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grajewski, J. Recent Advances in the Synthesis and Applications of Nitrogen-Containing Macrocycles. Molecules 2022, 27, 1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwit, M.; Grajewski, J.; Skowronek, P.; Zgorzelak, M.; Gawroński, J. One-Step Construction of the Shape Persistent, Chiral but Symmetrical Polyimine Macrocycles. Chem. Rec. 2019, 19, 213–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tashiro, S.; Shionoya, M. Novel Porous Crystals with Macrocycle-Based Well-Defined Molecular Recognition Sites. Acc. Chem. Res. 2020, 53, 632–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, D.; Wang, P.; Ji, X.; Khashab, N.M.; Sessler, J.L.; Huang, F. Functional Supramolecular Polymeric Networks: The Marriage of Covalent Polymers and Macrocycle-Based Host–Guest Interactions. Chem. Rev. 2020, 120, 6070–6123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Q.; Vargas-Zúñiga, G.I.; Kim, S.H.; Kim, S.K.; Sessler, J.L. Macrocycles as Ion Pair Receptors. Chem. Rev. 2019, 119, 9753–9835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhry, M.T.; Akine, S.; MacLachlan, M.J. Contemporary macrocycles for discrete polymetallic complexes: Precise control over structure and function. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2021, 50, 10713–10732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner-Wysiecka, E.; Łukasik, N.; Biernat, J.F.; Luboch, E. Azo group(s) in selected macrocyclic compounds. J. Incl. Phenom. Macrocycl. Chem. 2018, 90, 189–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nath, B.D.; Takaishi, K.; Ema, T. Macrocyclic multinuclear metal complexes acting as catalysts for organic synthesis. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2020, 10, 12–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belowich, M.E.; Stoddart, J.F. Dynamic imine chemistry. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012, 41, 2003–2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciaccia, M.; Di Stefano, S. Mechanisms of imine exchange reactions in organic solvents. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2015, 13, 646–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhers, S.; Holub, J.; Lehn, J.-M. Coevolution and ratiometric behaviour in metal cation-driven dynamic covalent systems. Chem. Sci. 2017, 8, 2125–2130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klein, J.M.; Saggiomo, V.; Reck, L.; Lüning, U.; Sanders, J.K.M. Dynamic combinatorial libraries for the recognition of heavy metal ions. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2012, 10, 60–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kołodziejski, M.; Stefankiewicz, A.R.; Lehn, J.-M. Dynamic polyimine macrobicyclic cryptands-self-sorting with component selection. Chem. Sci. 2019, 10, 1836–1843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matache, M.; Bogdan, E.; Hădade, N.D. Selective Host Molecules Obtained by Dynamic Adaptive Chemistry. Chem.—Eur. J. 2014, 20, 2106–2131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rue, N.M.; Sun, J.; Warmuth, R. Polyimine Container Molecules and Nanocapsules. Isr. J. Chem. 2011, 51, 743–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziach, K.; Jurczak, J. Controlling and Measuring the Equilibration of Dynamic Combinatorial Libraries of Imines. Org. Lett. 2008, 10, 5159–5162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, J.; Reibenspies, J.H.; Zingaro, R.A.; Woolley, F.R.; Martell, A.E.; Clearfield, A. Novel chiral “calixsalen” macrocycle and chiral Robson-type macrocyclic complexes. Inorg. Chem. 2005, 44, 232–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korupoju, S.R.; Mangayarkarasi, N.; Ameerunisha, S.; Valente, E.J.; Zacharias, P.S. Formation of dinuclear macrocyclic and mononuclear acyclic complexes of a new trinucleating hexaaza triphenolic Schiff base macrocycle: Structure and NLO properties. J. Chem. Soc. Dalton Trans. 2000, 16, 2845–2852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhnert, N.; Rossignolo, G.M.; Lopez-Periago, A. The synthesis of trianglimines: On the scope and limitations of the 3 + 3 cyclocondensation reaction between (1R,2R)diaminocyclohexane and aromatic dicarboxaldehydes. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2003, 1, 1157–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhnert, N.; Lopez-Periago, A.; Rossignolo, G.M. The synthesis and conformation of oxygenated trianglimine macrocycles. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2005, 3, 524–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janczak, J.; Prochowicz, D.; Lewiński, J.; Fairen-Jimenez, D.; Bereta, T.; Lisowski, J. Trinuclear Cage-Like ZnII Macrocyclic Complexes: Enantiomeric Recognition and Gas Adsorption Properties. Chem.—Eur. J. 2016, 22, 598–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarnicka, A.; Starynowicz, P.; Lisowski, J. Controlling the macrocycle size by the stoichiometry of the applied template ion. Chem. Commun. 2012, 48, 2237–2239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byun, J.C.; Lee, N.H.; Mun, D.H.; Park, K.M. Synthesis and characterization of dinuclear copper(II) complexes, Cu-2( 20 -DCHDC) (L-a)(2) (L-a = N-3(-), NCS- or S2O32-) with tetraazadiphenol macrocyclic ligand having cyclohexane rings. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2010, 13, 1156–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Liu, Y.-G.; Zhou, Y.; Boxer, L.M.; Woolley, F.R.; Zingaro, R.A. Artificial Zinc(II) Complexes Regulate Cell Cycle and Apoptosis-Related Genes in Tumor Cell Lines. ChemBioChem 2007, 8, 332–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Woolley, F.R.; Zingaro, R.A. Catalytic asymmetric cyclopropanation at a chiral platform. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2005, 3, 2126–2128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, J.; Reibenspies, J.H.; Martell, A.E. Structurally Defined Catalysts for Enantioselective Oxidative Coupling Reactions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2003, 42, 6008–6012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chinnaraja, E.; Arunachalam, R.; Samanta, J.; Natarajan, R.; Subramanian, P.S. Desymmetrization of meso diols using enantiopure zinc (II) dimers: Synthesis and chiroptical properties. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 2019, 33, e4827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinnaraja, E.; Arunachalam, R.; Pillai, R.S.; Peuronen, A.; Rissanen, K.; Subramanian, P.S. One-pot synthesis of [2 + 2]-helicate-like macrocycle and 2 + 4-μ4-oxo tetranuclear open frame complexes: Chiroptical properties and asymmetric oxidative coupling of 2-naphthols. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 2020, 34, e5666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregoliński, J.; Starynowicz, P.; Hua, K.T.; Lunkley, J.L.; Muller, G.; Lisowski, J. Helical Lanthanide(III) Complexes with Chiral Nonaaza Macrocycle. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 17761–17773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gregoliński, J.; Lisowski, J.; Lis, T. New 2 + 2, 3 + 3 and 4 + 4 macrocycles derived from 1,2-diaminocyclohexane and 2,6-diformylpyridine. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2005, 3, 3161–3166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lisowski, J.; Ripoli, S.; Di Bari, L. Axial ligand exchange in chiral macrocyclic ytterbium(III) complexes. Inorg. Chem. 2004, 43, 1388–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisowski, J. Enantiomeric Self-Recognition in Homo- and Heterodinuclear Macrocyclic Lanthanide(III) Complexes. Inorg. Chem. 2011, 50, 5567–5576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starynowicz, P.; Lisowski, J. Chirality transfer between hexaazamacrocycles in heterodinuclear rare earth complexes. Dalton Trans. 2019, 48, 8717–8724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ślepokura, K.; Cabreros, T.A.; Muller, G.; Lisowski, J. Sorting Phenomena and Chirality Transfer in Fluoride-Bridged Macrocyclic Rare Earth Complexes. Inorg. Chem. 2021, 60, 18442–18454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregoliński, J.; Ślepokura, K. Monomeric and dimeric nitrate lanthanide(III) and yttrium(III) coordination compounds of (2 + 2) imine macrocycle derived from 2,6-diformylpyridine and trans-1,2-diaminocyclopentane. Polyhedron 2020, 181, 114433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paluch, M.; Gawryszewska, P.; Lis, T.; Lisowski, J. Chiral macrocyclic lanthanide complexes derived from (R)-2,2′-diamino-1,1′-binaphthyl: X-ray crystal structure and luminescence studies. Polyhedron 2010, 29, 3387–3393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazurek, J.; Lisowski, J. Chiral macrocyclic lanthanide complexes derived from (1R,2R)-1,2-diphenylethylenediamine and 2,6-diformylpyridine. Polyhedron 2003, 22, 2877–2883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.-H.; Zhai, Y.-Q.; Chen, W.-P.; Ding, Y.-S.; Zheng, Y.-Z.; Li, Z.H.; Zhai, Y.Q.; Chen, W.P.; Ding, Y.S.; Zheng, Y.Z. Air-Stable Hexagonal Bipyramidal Dysprosium(III) Single-Ion Magnets with Nearly Perfect D-6h Local Symmetry. Chem.—Eur. J. 2019, 25, 16219–16224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Z.H.; Zhao, C.; Feng, T.T.; Liu, X.D.; Ying, X.; Li, X.L.; Zhang, Y.Q.; Tang, J.K. Air-Stable Chiral Single-Molecule Magnets with Record Anisotropy Barrier Exceeding 1800 K. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 10077–10082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krężel, A.; Lisowski, J. Enantioselective cleavage of supercoiled plasmid DNA catalyzed by chiral macrocyclic lanthanide (III) complexes. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2012, 107, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gregoliński, J.; Ślepokura, K.; Lisowski, J. Lanthanide complexes of the chiral hexaaza macrocycle and its meso-type isomer: Solvent-controlled helicity inversion. Inorg. Chem. 2007, 46, 7923–7934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerus, A.; Ślepokura, K.; Lisowski, J. Anion and Solvent Induced Chirality Inversion in Macrocyclic Lanthanide Complexes. Inorg. Chem. 2013, 52, 12450–12460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerus, A.; Ślepokura, K.; Lisowski, J. Carbonate-bridged dinuclear lanthanide(III) complexes of chiral macrocycle. Polyhedron 2019, 170, 115–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gospodarowicz, K.; Hołyńska, M.; Paluch, M.; Lisowski, J. Novel chiral hexaazamacrocycles for the enantiodiscrimination of carboxylic acids. Tetrahedron 2012, 68, 9930–9935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Álvarez, A.; Alfonso, I.; Díaz, P.; García-España, E.; Gotor, V. A highly enantioselective abiotic receptor for malate dianion in aqueous solution. Chem. Commun. 2006, 1227–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Gonzalez-Alvarez, A.; Alfonso, I.; Diaz, P.; Garcia-Espana, E.; Gotor-Fernandez, V.; Gotor, V. A simple helical macrocyclic polyazapyridinophane as a stereoselective receptor of biologically important dicarboxylates under physiological conditions. J. Org. Chem. 2008, 73, 374–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Busto, E.; Gonzalez-Alvarez, A.; Gotor-Fernandez, V.; Alfonso, I.; Gotor, V. Optically active macrocyclic hexaazapyridinophanes decorated at the periphery: Synthesis and applications in the NMR enantiodiscrimination of carboxylic acids. Tetrahedron 2010, 66, 6070–6077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraschetti, C.; Filippi, A.; Crestoni, M.E.; Marcantoni, E.; Glucini, M.; Guarcini, L.; Montagna, M.; Guidoni, L.; Speranza, M. Protonated Hexaazamacrocycles as Selective K+ Receptors. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2015, 26, 1186–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Fraschetti, C.; Filippi, A.; Crestoni, M.E.; Marcantoni, E.; Glucini, M.; Guarcini, L.; Montagna, M.; Guidoni, L.; Speranza, M. Contact Ion Pairs on a Protonated Azamacrocycle: The Role of the Anion Basicity. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2016, 27, 615–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grajewski, J.; Piotrowska, K.; Zgorzelak, M.; Janiak, A.; Biniek-Antosiak, K.; Rychlewska, U.; Gawronski, J. Introduction of axial chirality at a spiro carbon atom in the synthesis of pentaerythritol–imine macrocycles. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2018, 16, 981–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zgorzelak, M.; Grajewski, J. Axial chirality inversion at a spiro carbon leads to efficient synthesis of polyimine macrocycle. J. Mol. Struct. 2020, 1202, 127336–127341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gawroński, J.; Brzostowska, M.; Kwit, M.; Plutecka, A.; Rychlewska, U. Rhombimines-cyclic tetraimines of trans-1,2-diaminocyclohexane shaped by the diaryl ether structural motif. J. Org. Chem. 2005, 70, 10147–10150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gawroński, J.; Kwit, M.; Grajewski, J.; Gajewy, J.; Dlugokinska, A. Structural constraints for the formation of macrocyclic rhombimines. Tetrahedron Asymmetry 2007, 18, 2632–2637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigoras, M.; Vacareanu, L.; Ivan, T.; Ailiesei, G.L. Triphenylamine-based rhombimine macrocycles with solution interconvertable conformation. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2010, 8, 3638–3643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, K.; Nakai, Y.; Takahashi, H. Efficient NMR chiral discrimination of carboxylic acids using rhombamine macrocycles as chiral shift reagent. Tetrahedron Asymmetry 2011, 22, 178–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, K.; Iwashita, T.; Sasaki, C.; Takahashi, H. Ring-expanded chiral rhombamine macrocycles for efficient NMR enantiodiscrimination of carboxylic acid derivatives. Tetrahedron Asymmetry 2014, 25, 602–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.M.; Jablonski, C. Synthesis, characterization, and structure of macrocyclic mono- and C-2-symmetric, binuclear nickel calixsalen complexes. Inorg. Chem. 2000, 39, 2456–2461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadhukhan, A.; Khan, N.U.H.; Roy, T.; Kureshy, R.I.; Abdi, S.H.; Bajaj, H.C. Asymmetric Hydrolytic Kinetic Resolution with Recyclable Macrocyclic CoIII-Salen Complexes: A Practical Strategy in the Preparation of (R)-Mexiletine and (S)-Propranolol. Chem.—Eur. J. 2012, 18, 5256–5260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kureshy, R.I.; Das, A.; Khan, N.U.; Abdi, S.H.; Bajaj, H.C. Cu(II)-Macrocylic H-4 Salen Catalyzed Asymmetric Nitroaldol Reaction and Its Application in the Synthesis of alpha 1-Adrenergic Receptor Agonist (R)-Phenylephrine. Acs Catal. 2011, 1, 1529–1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, N.U.H.; Sadhukhan, A.; Maity, N.C.; Kureshy, R.I.; Abdi, S.H.; Saravanan, S.; Bajaj, H.C. Enantioselective O-acetylcyanation/cyanoformylation of aldehydes using catalysts with built-in crown ether-like motif in chiral macrocyclic V(V) salen complexes. Tetrahedron 2011, 67, 7073–7080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saravanan, S.; Khan, N.U.H.; Bera, P.K.; Kureshy, R.I.; Abdi, S.H.; Kumari, P.; Bajaj, H.C. Catalysis of Enantioselective Strecker Reaction in the Synthesis of D-Homophenylalanine Using Recyclable, Chiral, Macrocyclic MnIII-Salen Complexes. Chemcatchem 2013, 5, 1374–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadhukhan, A.; Choudhary, M.K.; Khan, N.U.H.; Kureshy, R.I.; Abdi, S.H.; Bajaj, H.C. Asymmetric Cyanoethoxy Carbonylation Reaction of Aldehydes Catalyzed by a TiIV Macrocyclic Complex: An Efficient Synthetic Protocol for -Blocker and 1-Adrenergic Receptor Agonists. Chemcatchem 2013, 5, 1441–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kureshy, R.I.; Roy, T.; Khan, N.U.; Abdi, S.H.; Sadhukhan, A.; Bajaj, H.C. Reusable chiral macrocyclic Mn(III) salen complexes for enantioselective epoxidation of nonfunctionalized alkenes. J. Catal. 2012, 286, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menapara, T.; Choudhary, M.K.; Tak, R.; Kureshy, R.I.; Khan, N.U.; Abdi, S.H. Recyclable chiral Cu(II) macrocyclic salen complex catalyzed enantioselective aza-Henry reaction of isatin derived N-Boc ketimines and its application for the synthesis of beta-diamine. J. Mol. Catal. A Chem. 2016, 421, 161–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinnaraja, E.; Arunachalam, R.; Choudhary, M.K.; Kureshy, R.I.; Subramanian, P.S. Binuclear Cu(II) chiral complexes: Synthesis, characterization and application in enantioselective nitroaldol (Henry) reaction. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 2016, 30, 95–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Chang, F.F.; Zhao, P.C.; Feng, G.F.; Zhang, K.; Huang, W. Construction of Chiral 4 + 4 and 2 + 2 Schiff-Base Macrocyclic Zinc(II) Complexes Influenced by Counterions and Pendant Arms. Inorg. Chem. 2016, 55, 8260–8262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, F.F.; Li, W.Q.; Feng, F.D.; Huang, W. Construction and Photoluminescent Properties of Schiff-Base Macrocyclic Mono-/Di-/Trinuclear Zn-II Complexes with the Common 2-Ethylthiophene Pendant Arm. Inorg. Chem. 2019, 58, 7812–7821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, P.C.; Chang, F.F.; Feng, F.D.; Huang, W. Transmetalation and Demetallization for Open-Oyster-like Non-Ionic Cd(II) Macrocycles. Inorg. Chem. 2020, 59, 7504–7511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gualandi, A.; Cerisoli, L.; Stoeckli-Evans, H.; Savoia, D. Pyrrole Macrocyclic Ligands for Cu-Catalyzed Asymmetric Henry Reactions. J. Org. Chem. 2011, 76, 3399–3408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.Y.; Yu, S.L.; Wu, X.F.; Xiao, J.L.; Shen, W.Y.; Dong, Z.R.; Gao, J.X. Iron Catalyzed Asymmetric Hydrogenation of Ketones. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 4031–4039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.L.; Shen, W.Y.; Li, Y.Y.; Dong, Z.R.; Xu, Y.Q.; Li, Q.; Zhang, J.N.; Gao, J.X. Iron-Catalyzed Highly Enantioselective Reduction of Aromatic Ketones with Chiral P2N4-Type Macrocycles. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2012, 354, 818–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.B.; Lin, J.; Pu, L. A cyclohexyl-1,2-diamine-derived bis(binaphthyl) macrocycle: Enhanced sensitivity and enantioselectivity in the fluorescent recognition of mandelic acid. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2005, 44, 1690–1693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.B.; Lin, J.; Sabat, M.; Hyacinth, M.; Pu, L. Enantioselective fluorescent recognition of chiral acids by cyclohexane-1,2-diamine-based bisbinaphthyl molecules. J. Org. Chem. 2007, 72, 4905–4916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Lin, J.; Zhang, H.C.; Pu, L. Bisbinaphthyl macrocycle-based highly enantioselective fluorescent sensors for alpha-hydroxycarboxylic acids. Org. Lett. 2002, 4, 3297–3300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, X.C.; Trindle, C.O.; Zhang, G.Q.; Pu, L. Fluorescent recognition of Hg2+ by a 1,1 ′-binaphthyl-based macrocycle: A highly selective off-on-off response. Chem. Commun. 2015, 51, 8469–8472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, K.; Yang, X.; Cheng, Y.X.; Zhu, C.J. A highly selective ratiometric fluorescent chemosensor for Zn2+ ion based on a polyimine macrocycle. Tetrahedron 2012, 68, 5719–5723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Liu, X.C.; Shen, K.; Zhu, C.J.; Cheng, Y.X. A Chiral Perazamacrocyclic Fluorescent Sensor for Cascade Recognition of Cu(II) and the Unmodified alpha-Amino Acids in Protic Solutions. Org. Lett. 2011, 13, 3510–3513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gawroński, J.; Kolbon, H.; Kwit, M.; Katrusiak, A. Designing large triangular chiral macrocycles: Efficient 3 + 3 diamine-dialdehyde condensations based on conformational bias. J. Org. Chem. 2000, 65, 5768–5773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korupoju, S.R.; Zacharias, P.S. New optically active hexaaza triphenolic macrocycles: Synthesis, molecular structure and crystal packing features. Chem. Commun. 1998, 12, 1267–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grajewski, J.; Zgorzelak, M.; Janiak, A.; Taras-Goslinska, K. Controlled, Sunlight-Driven Reversible Cycloaddition of Multiple Singlet Oxygen Molecules to Anthracene-Containing Trianglimine Macrocycles. Chempluschem 2022, 87, e202100510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Nour, H.F.; Roch, L.M.; Guo, M.; Li, W.; Baldridge, K.K.; Sue, A.C.H.; Olson, M.A. 3 + 3 Cyclocondensation of Disubstituted Biphenyl Dialdehydes: Access to Inherently Luminescent and Optically Active Hexa-substituted C-3-Symmetric and Asymmetric Trianglimine Macrocycles. J. Org. Chem. 2017, 82, 2472–2480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janiak, A.; Gajewy, J.; Szymkowiak, J.; Gierczyk, B.; Kwit, M. Specific Noncovalent Association of Truncated exo-Functionalized Triangular Homochiral Isotrianglimines through Head-to-Head, Tail-to-Tail, and Honeycomb Supramolecular Motifs. J. Org. Chem. 2022, 87, 2356–2366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szymkowiak, J.; Warżajtis, B.; Rychlewska, U.; Kwit, M. Consistent supramolecular assembly arising from a mixture of components-self-sorting and solid solutions of chiral oxygenated trianglimines. Crystengcomm 2018, 20, 5200–5208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szymkowiak, J.; Warżajtis, B.; Rychlewska, U.; Kwit, M. One-step Access to Resorcinsalens-Solvent-Dependent Synthesis, Tautomerism, Self-sorting and Supramolecular Architectures of Chiral Polyimine Analogues of Resorcinarene. Chem.—Eur. J. 2018, 24, 6041–6046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troć, A.; Gajewy, J.; Danikiewicz, W.; Kwit, M. Specific Noncovalent Association of Chiral Large-Ring Hexaimines: Ion Mobility Mass Spectrometry and PM7 Study. Chem.—Eur. J. 2016, 22, 13258–13264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petryk, M.; Janiak, A.; Barbour, L.J.; Kwit, M. Awkwardly-Shaped Dimers, Capsules and Tetramers: Molecular and Supramolecular Motifs in C5-Arylated Chiral Calixsalens. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2018, 16, 1916–1923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petryk, M.; Troć, A.; Gierczyk, B.; Danikiewicz, W.; Kwit, M. Dynamic Formation of Noncovalent Calixsalen Aggregates. Chem.—Eur. J. 2015, 21, 10318–10321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janiak, A.; Bardziński, M.; Gawroński, J.; Rychlewska, U. From Cavities to Channels in Host:Guest Complexes of Bridged Trianglamine and Aliphatic Alcohols. Cryst. Growth Des. 2016, 16, 2779–2788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janiak, A.; Petryk, M.; Barbour, L.J.; Kwit, M. Readily prepared inclusion forming chiral calixsalens. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2016, 14, 669–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajewy, J.; Gawroński, J.; Kwit, M. Convenient, enantioselective hydrosilylation of imines in protic media catalyzed by a Zn-trianglamine complex. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2011, 9, 3863–3870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, K.; Fukuda, N.; Fujiwara, T. Trianglamine as a new chiral shift reagent for secondary alcohols. Tetrahedron Asymmetry 2007, 18, 2657–2661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gualandi, A.; Grilli, S.; Savoia, D.; Kwit, M.; Gawroński, J. C-hexaphenyl-substituted trianglamine as a chiral solvating agent for carboxylic acids. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2011, 9, 4234–4241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, K.; Fukuda, N. ‘Calixarene-like’ chiral amine macrocycles as novel chiral shift reagents for carboxylic acids. Tetrahedron Asymmetry 2009, 20, 111–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, K.; Tsuchitani, T.; Fukuda, N.; Masumoto, A.; Arakawa, R. Highly enantioselective fluorescent recognition of mandelic acid derivatives by chiral salen macrocycles. Tetrahedron Asymmetry 2012, 23, 205–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwit, M.; Zabicka, B.; Gawroński, J. Synthesis of chiral large-ring triangular salen ligands and structural characterization of their complexes. Dalton Trans. 2009, 34, 6783–6789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez-Alvarez, A.; Alfonso, I.; Lopez-Ortiz, F.; Aguirre, A.; Garcia-Granda, S.; Gotor, V. Selective host amplification from a dynamic combinatorial library of oligoimines for the syntheses of different optically active polyazamacrocycles. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2004, 5, 1117–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Alvarez, A.; Alfonso, I.; Gotor, V. Highly diastereoselective amplification from a dynamic combinatorial library of macrocyclic oligoimines. Chem. Commun. 2006, 21, 2224–2226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Gonzalez-Alvarez, A.; Alfonso, I.; Cano, J.; Diaz, P.; Gotor, V.; Gotor-Fernandez, V.; Garcia-Espana, E.; Garcia-Granda, S.; Jimenez, H.R.; Lloret, F. A Ferromagnetic [Cu3(OH)2]4+ Cluster Formed inside a Tritopic Nonaazapyridinophane: Crystal Structure and Solution Studies. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2009, 48, 6055–6058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loffler, M.; Gregoliński, J.; Korabik, M.; Lis, T.; Lisowski, J. Multinuclear Ni(II), Cu(II) and Zn(II) complexes of chiral macrocyclic nonaazamine. Dalton Trans. 2016, 45, 15586–15594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, C.Q.; Ren, J.S.; Gregoliński, J.; Lisowski, J.; Qu, X.G. Contrasting enantioselective DNA preference: Chiral helical macrocyclic lanthanide complex binding to DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 40, 8186–8196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Gregoliński, J.; Lisowski, J. Helicity inversion in lanthanide(III) complexes with chiral nonaaza macrocyclic ligands. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2006, 45, 6122–6126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gregoliński, J.; Lis, T.; Cyganik, M.; Lisowski, J. Lanthanide Complexes of the Heterochiral Nonaaza Macrocycle: Switching the Orientation of the Helix Axis. Inorg. Chem. 2008, 47, 11527–11534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.C.; Chu, Z.L.; Huang, W.; Wang, G.; You, X.Z. Dinuclear Cadmium(II), Zinc(II), and Manganese(II), Trinuclear Nickel(II), and Pentanuclear Copper(II) Complexes with Novel Macrocyclic and Acyclic Schiff-Base Ligands Having Enantiopure or Racemic Camphoric Diamine Components. Inorg. Chem. 2010, 49, 5897–5911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, S.M.; Fu, N.; Li, L.; Yuan, B.Y.; Zhang, J.H.; Li, Y.X.; Yuan, L.M. Homochiral Metal-Organic Cage for Gas Chromatographic Separations. Anal. Chem. 2018, 90, 9182–9188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.X.; Tian, C.R.; Zhang, J.H.; Xu, W.; Peng, B.; Xie, S.M.; Zi, M.; Yuan, L.M. Chiral metal-organic cages used as stationary phase for enantioseparations in capillary electrochromatography. Electrophoresis 2020, 41, 104–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.T.; Mao, Z.K.; Zhou, W.; Chen, Z.L. Incorporation of homochiral metal-organic cage into ionic liquid based monolithic column for capillary electrochromatography. Anal. Chim. Acta 2020, 1094, 160–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kobyłka, M.J.; Janczak, J.; Lis, T.; Kowalik-Jankowska, T.; Klak, J.; Pietruszka, M.; Lisowski, J. Trinuclear Cu(II) complexes of a chiral N6O3 amine. Dalton Trans. 2012, 41, 1503–1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korupoju, S.R.; Mangayarkarasi, N.; Zacharias, P.S.; Mizuthani, J.; Nishihara, H. Synthesis, structure, and DNA cleavage activity of new trinuclear Zn-3 and Zn-2Cu complexes of a chiral macrocycle: Structural correlation with the active center of P1 nuclease. Inorg. Chem. 2002, 41, 4099–4101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, J.; Zingaro, R.A.; Reibenspies, J.H.; Martell, A.E. Direct observation of enantioselective synergism at trimetallic centers. Org. Lett. 2004, 6, 2453–2455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobyłka, M.J.; Ślepokura, K.; Rodicio, M.A.; Paluch, M.; Lisowski, J. Incorporation of Trinuclear Lanthanide(III) Hydroxo Bridged Clusters in Macrocyclic Frameworks. Inorg. Chem. 2013, 52, 12893–12903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bereta, T.; Mondal, A.; Ślepokura, K.; Peng, Y.; Powell, A.K.; Lisowski, J. Trinuclear and Hexanuclear Lanthanide(III) Complexes of the Chiral 3 + 3 Macrocycle: X-ray Crystal Structures and Magnetic Properties. Inorg. Chem. 2019, 58, 4201–4213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, S.Y.; Guo, Y.N.; Guo, Y.; Zhao, L.; Zhang, P.; Ke, H.S.; Tang, J.K. Macrocyclic ligand encapsulating dysprosium triangles: Axial ligands perturbed magnetic dynamics. Chem. Commun. 2012, 48, 6924–6926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.Y.; Wang, C.; Zhao, L.; Tang, J.K. Enantioselective Self-Assembly of Triangular Dy-3 Clusters with Single Molecule Magnet Behavior. Chem. Asian J. 2014, 9, 3558–3564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wydra, K.; Kobyłka, M.J.; Lis, T.; Ślepokura, K.; Lisowski, J. Versatile Binding Modes of Chiral Macrocyclic Amine towards Rare Earth Ions. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2020, 2020, 2096–2104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamashita, A.; Watanabe, A.; Akine, S.; Nabeshima, T.; Nakano, M.; Yamamura, T.; Kajiwara, T. Wheel-Shaped (ErZn3II)-Zn-III Single-Molecule Magnet: A Macrocyclic Approach to Designing Magnetic Anisotropy. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011, 50, 4016–4019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

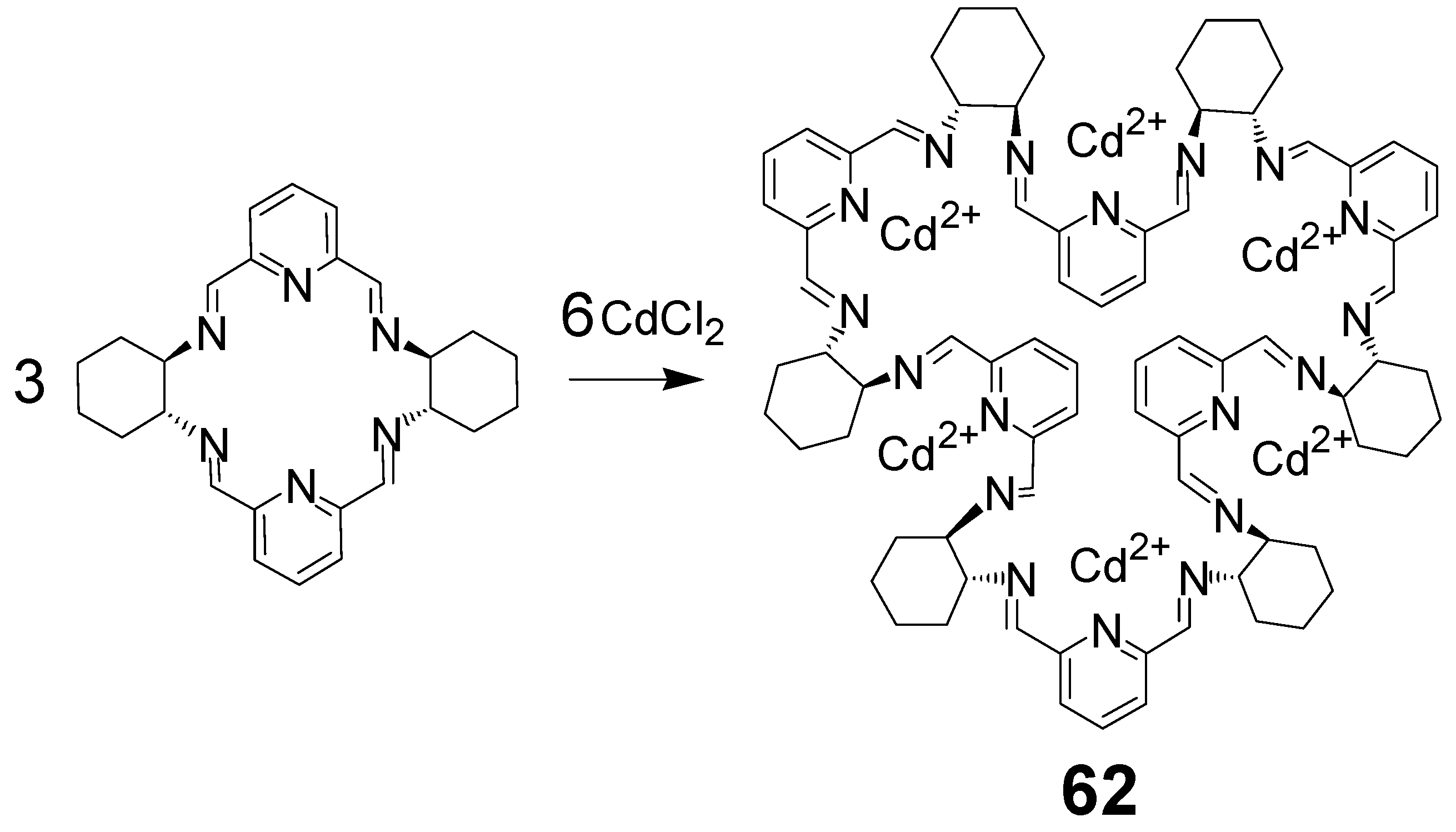

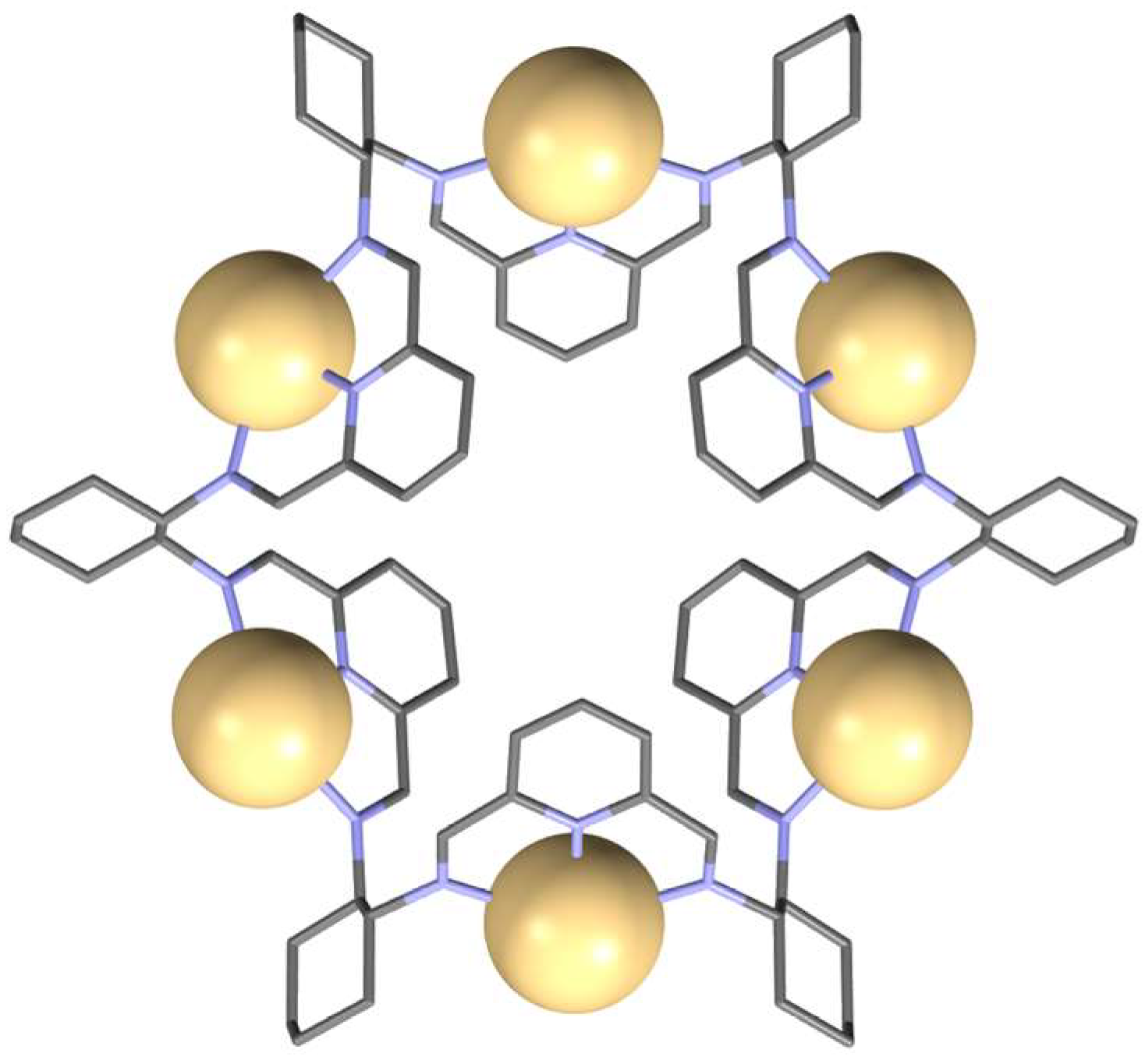

- Gregoliński, J.; Ślepokura, K.; Paćkowski, T.; Lisowski, J. Expansion of a 2 + 2 Macrocycle into a 6 + 6 Macrocycle: Template Effect of Cadmium(II). Org. Lett. 2014, 16, 4372–4375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

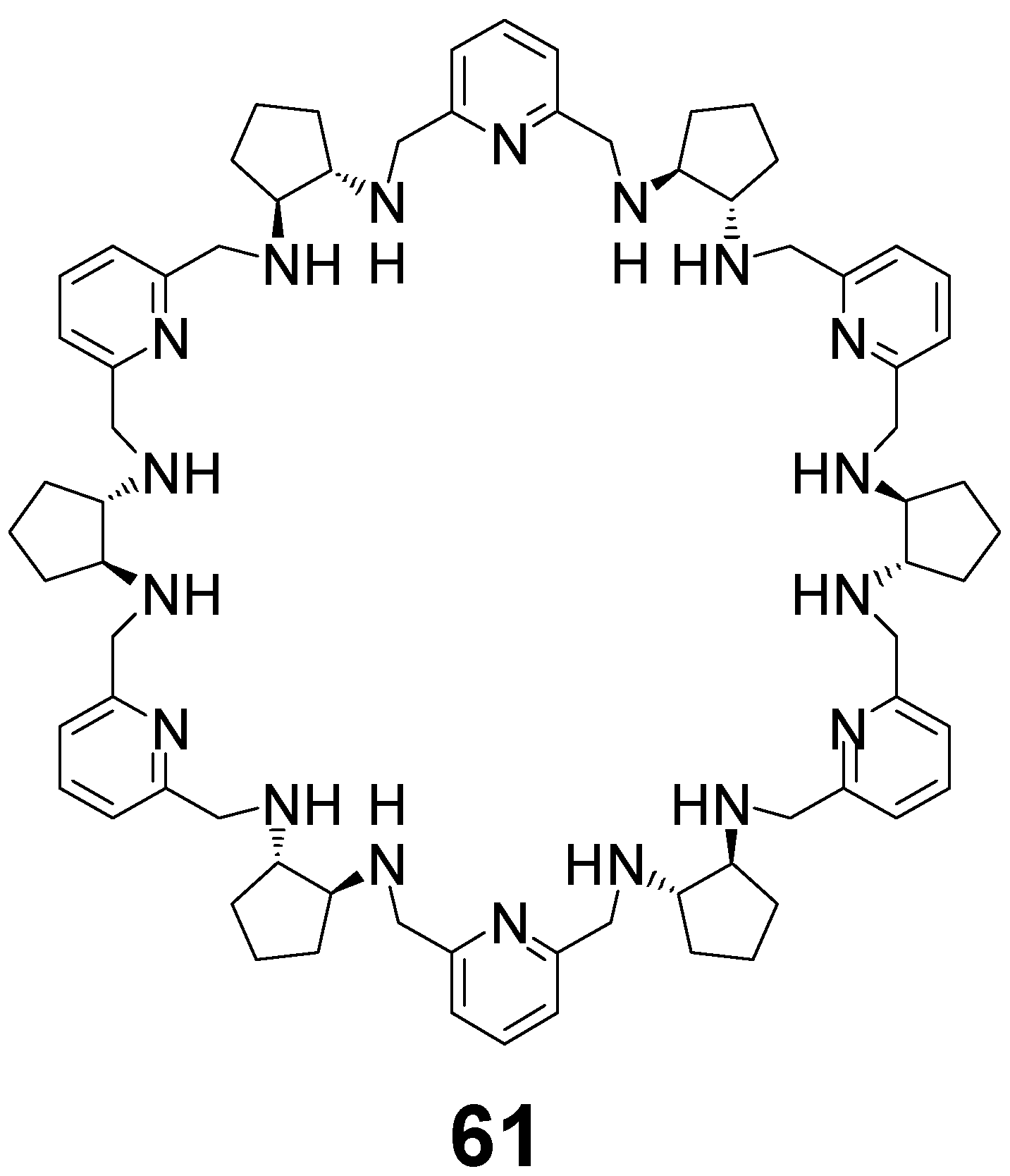

- Gregoliński, J.; Ślepokura, K.; Bil, A.; Lisowski, J. A New Synthetic Strategy Leading to Homochiral Macrocycles Derived from 2,6-Diformylpyridine and (1S,2S)-trans-1,2-Diaminocyclopentane. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2020, 2020, 5714–5728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedorowicz, D.; Banach, S.; Koza, P.; Frydrych, R.; Ślepokura, K.; Gregoliński, J. Controlling chirality in the synthesis of 4 + 4 diastereomeric amine macrocycles derived from trans-1,2-diaminocyclopentane and 2,6-diformylpyridine. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2022, 20, 1080–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zgorzelak, M.; Grajewski, J.; Gawroński, J.; Kwit, M. Solvent-assisted synthesis of a shape-persistent chiral polyaza gigantocycle characterized by a very large internal cavity and extraordinarily high amplitude of the ECD exciton couplet. Chem. Commun. 2019, 55, 2301–2304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregoliński, J.; Ślepokura, K.; Paćkowski, T.; Panek, J.; Stefanowicz, P.; Lisowski, J. From 2 + 2 to 8 + 8 Condensation Products of Diamine and Dialdehyde: Giant Container-Shaped Macrocycles for Multiple Anion Binding. J. Org. Chem. 2016, 81, 5285–5294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gregoliński, J.; Ślepokura, K.; Lisowski, J. Hexanuclear and Trinuclear Metal Complexes of a Giant Octadecaaza Macrocycle. Inorg. Chem. 2017, 56, 12719–12727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paćkowski, T.; Gregoliński, J.; Ślepokura, K.; Lisowski, J. 6 + 6 Macrocycles derived from 2,6-diformylpyridine and trans-1,2-diaminocyclohexane. Tetrahedron Lett. 2018, 59, 3669–3673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frydrych, R.; Ślepokura, K.; Bil, A.; Gregoliński, J. Mixed Macrocycles Derived from 2,6-Diformylpyridine and Opposite Enantiomers of trans-1,2-Diaminocyclopentane and trans-1,2-Diaminocyclohexane. J. Org. Chem. 2019, 84, 5695–5711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolska, K.; Janczak, J.; Gawryszewska, P.; Lisowski, J. Rare earth complexes of chiral unsymmetrical hexaazamacrocycles. Polyhedron 2021, 198, 115057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lisowski, J. Imine- and Amine-Type Macrocycles Derived from Chiral Diamines and Aromatic Dialdehydes. Molecules 2022, 27, 4097. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules27134097

Lisowski J. Imine- and Amine-Type Macrocycles Derived from Chiral Diamines and Aromatic Dialdehydes. Molecules. 2022; 27(13):4097. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules27134097

Chicago/Turabian StyleLisowski, Jerzy. 2022. "Imine- and Amine-Type Macrocycles Derived from Chiral Diamines and Aromatic Dialdehydes" Molecules 27, no. 13: 4097. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules27134097

APA StyleLisowski, J. (2022). Imine- and Amine-Type Macrocycles Derived from Chiral Diamines and Aromatic Dialdehydes. Molecules, 27(13), 4097. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules27134097