Ascorbate as a Bioactive Compound in Cancer Therapy: The Old Classic Strikes Back

Abstract

:1. Introduction

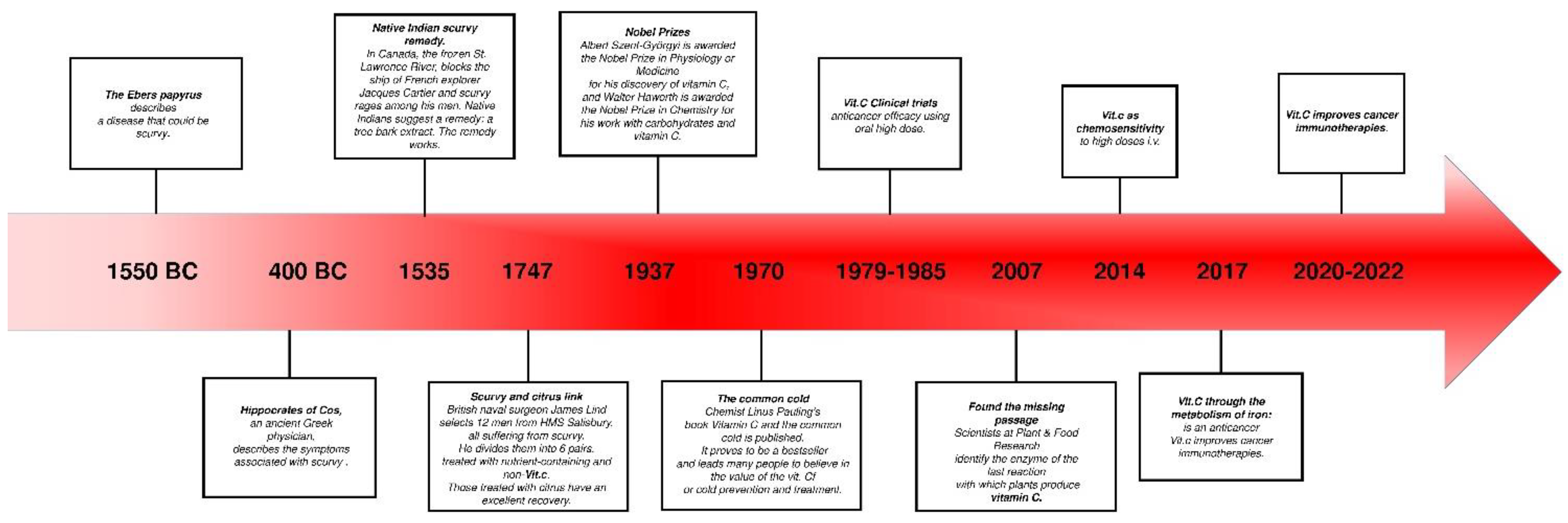

1.1. Historical Aspects

1.2. Ascorbate in Human Medicine

- Collagen production: Ascorbate plays the role of a coenzyme for prolyl and lysyl hydroxylases in order to convert protocollagen to collagen. Ascorbate is necessary for the maintenance of connective tissue and the wound healing process [7].

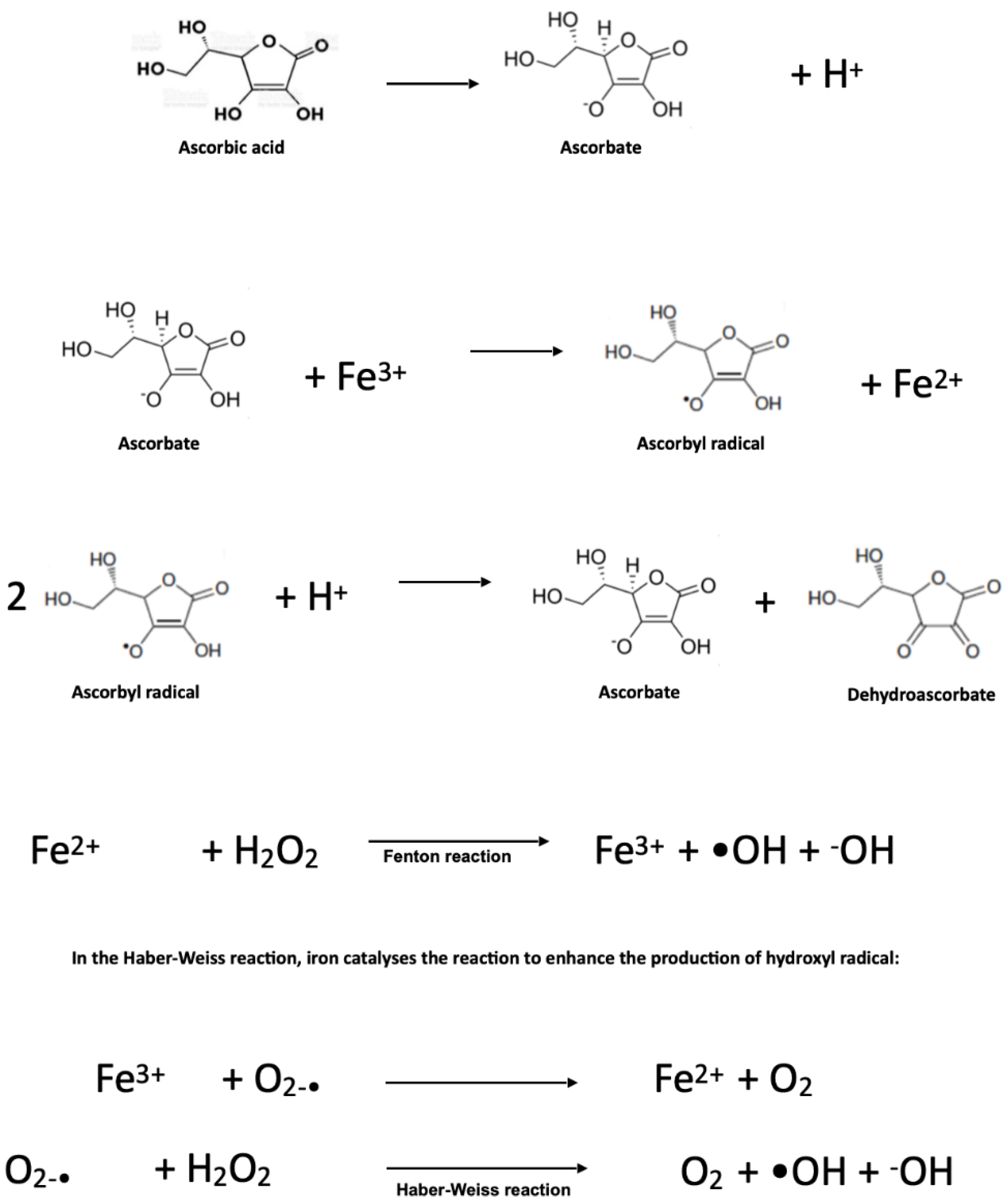

- Iron, haemoglobin metabolism, and erythrocyte maturation: Ascorbate enhances iron absorption by keeping it in the ferrous form. Due its reducing property, vitamin C helps the storage form of iron (complexed with ferritin) and its metabolisation [8]. Ascorbic acid is also involved in the production of the active form of folic acid and in erythrocyte maturation [9].

- Hormone synthesis: The synthesis of many hormones requires vitamin C. Ascorbate is an important cofactor of dopamine β-hydroxylase, the enzyme required to convert dopamine into norepinephrine [12]. Ascorbate is also an essential cofactor for the enzyme peptidylglycine α-amidating mono-oxygenase, which is required for the synthesis of vasopressin. Moreover, ascorbate may contribute to the magnitude of vasopressin biosynthesis [13]. Ascorbate is necessary for the hydroxylation reactions in the synthesis of corticosteroid hormones [14].

- Immunological function: Ascorbate enhances the synthesis of immunoglobulins and increases the phagocytic action of leucocytes [15]. Moreover, vitamin C has been shown to regulate the expression of pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines, to improve chemotaxis and phagocytosis, to enhance lymphocytic proliferation, and to assist in the oxidative neutrophilic killing of bacteria [13].

- Prevention of some diseases: Vitamin C concentrations may be low in acute illnesses, including myocardial infarction, pancreatitis, and sepsis [16]. Ascorbate, as an antioxidant, reduces coronary heart diseases and the risk of cancer [17]. Ascorbate has been shown to be involved in other biochemical activities [18], protecting the body from free radicals, enhancing the absorption of iron from vegetables, cereals, and fruits, helping in resistance against the common cold, and preventing some types of cancer [19].

- Ascorbate is widely known for its immunological functions. Ascorbate enhances the synthesis of immunoglobulins and increases the phagocytic action of leucocytes [15]. Moreover, vitamin C has been shown to regulate the expression of pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines, to improve chemotaxis and phagocytosis, to enhance lymphocytic proliferation, and to assist in the oxidative neutrophilic killing of bacteria [13]. More broadly, low levels of vitamin C have been implicated in a variety of acute illnesses, suggesting a potential application in disease prevention. Low levels of vitamin C have been described in association with acute myocardial infarction, pancreatitis, and sepsis [16]. Ascorbate, as an antioxidant, reduces coronary heart diseases and the risk of developing cancer [17]. Its myriad biochemical activities [18] have been proposed to contribute to a variety of health benefits, including protecting the body from free radicals, enhancing the absorption of iron from vegetables, cereals, and fruits, contributing to resistance against the common cold [19].

2. Pharmacology of Ascorbate

2.1. Ascorbate Distribution

2.2. Plasma Ascorbate Concentrations

2.3. Ascorbate Pharmacodynamics and Pharmacokinetic

2.4. Ascorbate Transport

2.5. Subcellular Distribution

2.5.1. Endoplasmic Reticulum

2.5.2. Mitochondrion

2.5.3. Nucleus

2.6. Ascorbate and Redox Balance

2.7. Pro-Oxidant Effects of Ascorbate

2.8. Ascorbate-GSH and Glucose Metabolism

2.9. Ascorbate and Enhancement of Cell Death

2.10. Ascorbate and Ferroptosis

2.11. The Ascorbate Paradox: Biphasic Effect

2.12. Hormetic Effect of Ascorbate

3. Application of Ascorbate in Cancer Therapy

3.1. Experimental Models

3.2. Clinical Models

3.2.1. Cancer Prevention

3.2.2. Cancer Treatment

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- van Gorkom, G.N.Y.; Lookermans, E.L.; Van Elssen, C.H.M.J.; Bos, G.M.J. The Effect of Vitamin C (Ascorbic Acid) in the Treatment of Patients with Cancer: A Systematic Review. Nutrients 2019, 11, 977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Siegel, R.L.; Miller, K.D.; Fuchs, H.E.; Jemal, A. Cancer Statistics, 2021. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71, 7–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ngo, B.; Van Riper, J.M.; Cantley, L.C.; Yun, J. Targeting cancer vulnerabilities with high-dose vitamin C. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2019, 19, 271–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manzie, T.; Celine, G.; Kakulas, E. Scurvy: The almost forgotten disease—A case report. Aust. Dent. J. 2022, 67, 100–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Packer, L.; Fuchs, J. Vitamin C in Health and Disease; Marcel Dekker Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1997; ISBN 0-8247-9313-7. [Google Scholar]

- Du, J.; Cullen, J.J.; Buettner, G.R. Ascorbic acid: Chemistry, biology and the treatment of cancer. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2012, 1826, 443–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Murad, S.; Grove, D.; Lindberg, K.A.; Reynolds, G.; Sivarajah, A.; Pinnell, S.R. Regulation of collagen synthesis by ascorbic acid. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1981, 78, 2879–2882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lane, D.J.; Richardson, D.R. The active role of vitamin C in mammalian iron metabolism: Much more than just enhanced iron absorption! Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2014, 75, 69–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magana, A.A.; Reed, R.L.; Koluda, R.; Miranda, C.L.; Maier, C.S.; Stevens, J.F. Vitamin C Activates the Folate-Mediated One-Carbon Cycle in C2C12 Myoblasts. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cooper, J.R. The role of ascorbic acid in the oxidation of tryptophan to 5-hydroxytryptophan. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1961, 92, 208–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doseděl, M.; Jirkovský, E.; Macáková, K.; Krčmová, L.K.; Javorská, L.; Pourová, J.; Mercolini, L.; Remião, F.; Nováková, L.; Mladěnka, P. Vitamin C-Sources, Physiological Role, Kinetics, Deficiency, Use, Toxicity, and Determination. Nutrients 2021, 13, 615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, J.M.; Qu, Z.C.; Meredith, M.E. Mechanisms of ascorbic acid stimulation of norepinephrine synthesis in neuronal cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2012, 426, 148–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gordon, D.S.; Rudinsky, A.J.; Guillaumin, J.; Parker, V.J.; Creighton, K.J. Vitamin C in Health and Disease: A Companion Animal Focus. Top. Companion Anim. Med. 2020, 39, 100432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitani, F.; Ogishima, T.; Mukai, K.; Suematsu, M. Ascorbate stimulates monooxygenase-dependent steroidogenesis in adrenal zona glomerulosa. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2005, 338, 483–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, A.C.; Maggini, S. Vitamin C and Immune Function. Nutrients 2017, 9, 1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kashiouris, M.G.; L’Heureux, M.; Cable, C.A.; Fisher, B.J.; Leichtle, S.W.; Fowler, A.A. The Emerging Role of Vitamin C as a Treatment for Sepsis. Nutrients 2020, 12, 292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Morelli, M.B.; Gambardella, J.; Castellanos, V.; Trimarco, V.; Santulli, G. Vitamin C and Cardiovascular Disease: An Update. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambial, S.; Dwivedi, S.; Shukla, K.K.; John, P.J.; Sharma, P.; Vitamin, C. in disease prevention and cure: An overview. Indian J. Clin. Biochem. 2013, 28, 314–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pawlowska, E.; Szczepanska, J.; Blasiak, J. Pro- and Antioxidant Effects of Vitamin C in Cancer in correspondence to Its Dietary and Pharmacological Concentrations. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2019, 2019, 7286737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lykkesfeldt, J.; Tveden-Nyborg, P. The Pharmacokinetics of Vitamin C. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Subramanian, V.S.; Srinivasan, P.; Wildman, A.J.; Marchant, J.S.; Said, H.M. Molecular mechanism(s) involved in differential expression of vitamin C transporters along the intestinal tract. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2017, 312, G340–G347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hasselholt, S.; Tveden-Nyborg, P.; Lykkesfeldt, J. Distribution of vitamin C is tissue specific with early saturation of the brain and adrenal glands following differential oral dose regimens in guinea pigs. Br. J. Nutr. 2015, 113, 1539–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Padayatty, S.J.; Sun, H.; Wang, Y.; Riordan, H.D.; Hewitt, S.M.; Katz, A.; Wesley, R.A.; Levine, M. Vitamin C pharmacokinetics: Implications for oral and intravenous use. Ann. Intern. Med. 2004, 140, 533–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duconge, J.; Miranda-Massari, J.R.; Gonzalez, M.J.; Jackson, J.A.; Warnock, W.; Riordan, N.H. Pharmacokinetics of vitamin C: Insights into the oral and intravenous administration of ascorbate. P. R. Health Sci. J. 2008, 27, 7–19. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Przybyło, M.; Langner, M. On the physiological and cellular homeostasis of ascorbate. Cell. Mol. Biol. Lett. 2020, 25, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Böttger, F.; Vallés-Martí, A.; Cahn, L.; Jimenez, C.R. High-dose intravenous vitamin C, a promising multi-targeting agent in the treatment of cancer. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2021, 40, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tóth, S.Z.; Lőrincz, T.; Szarka, A. Concentration Does Matter: The Beneficial and Potentially Harmful Effects of Ascorbate in Humans and Plants. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2018, 29, 1516–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tsukaguchi, H.; Tokui, T.; Mackenzie, B.; Berger, U.V.; Chen, X.Z.; Wang, Y.; Brubaker, R.F.; Hedigeret, M.A. A family of mammalian Na+-dependent L-ascorbic acid transporters. Nature 1999, 399, 70–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linowiecka, K.; Foksinski, M.; Brożyna, A.A. Vitamin C Transporters and Their Implications in Carcinogenesis. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayland, C.R.; Bennett, M.I.; Allan, K. Vitamin C deficiency in cancer patients. Palliat. Med. 2005, 19, 17–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timpson, N.J.; Forouhi, N.G.; Brion, M.J.; Harbord, R.M.; Cook, D.G.; Johnson, P.; McConnachie, A.; Morris, R.W.; Rodriguez, S.; Luan, J.; et al. Genetic variation at the SLC23A1 locus is associated with circulating concentrations of L-ascorbic acid (vitamin C): Evidence from 5 independent studies with >15,000 participants. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2010, 92, 375–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zangar, R.C.; Davydov, D.R.; Verma, S. Mechanisms that regulate production of reactive oxygen species by cytochrome P450. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2004, 199, 316–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vissers, M.C.; Kuiper, C.; Dachs, G.U. Regulation of the 2-oxoglutarate-dependent dioxygenases and implications for cancer. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2014, 42, 945–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saaranen, M.J.; Karala, A.R.; Lappi, A.K.; Ruddock, L.W. The role of dehydroascorbate in disulfide bond formation. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2010, 12, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pozzer, D.; Invernizzi, R.W.; Blaauw, B.; Cantoni, O.; Zito, E. Ascorbic Acid Route to the Endoplasmic Reticulum: Function and Role in Disease. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2021, 34, 845–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, J.M.; Li, L.; Qu, Z.C.; Cobb, C.E. Mitochondrial recycling of ascorbic acid as a mechanism for regenerating cellular ascorbate. Biofactors 2007, 30, 35–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakalova, R.; Zhelev, Z.; Miller, T.; Aoki, I.; Higashi, T. Vitamin C versus Cancer: Ascorbic Acid Radical and Impairment of Mitochondrial Respiration? Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2020, 2020, 1504048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canali, R.; Natarelli, L.; Leoni, G.; Azzini, E.; Comitato, R.; Sancak, O.; Barella, L.; Virgili, F. Vitamin C supplementation modulates gene expression in peripheral blood mononuclear cells specifically upon an inflammatory stimulus: A pilot study in healthy subjects. Genes Nutr. 2014, 9, 390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Losman, J.A.; Koivunen, P.; Kaelin, W.G., Jr. 2-Oxoglutarate-dependent dioxygenases in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2020, 20, 710–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corti, A.; Raggi, C.; Franzini, M.; Paolicchi, A.; Pompella, A.; Casini, A.F. Plasma membrane gamma-glutamyltransferase activity facilitates the uptake of vitamin C in melanoma cells. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2004, 37, 1906–1915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, F.E.; May, J.M. Vitamin C function in the brain, vital role of the ascorbate transporter SVCT2. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2009, 46, 719–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Parrow, N.L.; Leshin, J.A.; Levine, M. Parenteral ascorbate as a cancer therapeutic: A reassessment based on pharmacokinetics. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2013, 19, 2141–2156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schoenfeld, J.D.; Alexander, M.S.; Waldron, T.J.; Sibenaller, Z.A.; Spitz, D.R.; Buettner, G.R.; Allen, B.G.; Cullen, J.J. Pharmacological Ascorbate as a Means of Sensitizing Cancer Cells to Radio-Chemotherapy While Protecting Normal Tissue. Semin Radiat Oncol. 2019, 29, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.Z.; Lee, E.E.; Sudderth, J.; Yue, Y.; Zia, A.; Glass, D.; Deberardinis, R.J.; Wang, R.C. Glutathione Depletion, Pentose Phosphate Pathway Activation, and Hemolysis in Erythrocytes Protecting Cancer Cells from Vitamin C-induced Oxidative Stress. J. Biol. Chem. 2016, 291, 22861–22867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Smeyne, M.; Smeyne, R.J. Glutathione metabolism and Parkinson’s disease. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2013, 62, 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Szarka, A.; Kapuy, O.; Lőrincz, T.; Bánhegyi, G. Vitamin C and Cell Death. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2021, 34, 831–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Liu, T.; Li, Z.; Feng, Y.; Corpe, C.; Liu, S.; Zhang, J.; He, X.; Liu, F.; Xu, L.; et al. Hepatomas are exquisitely sensitive to pharmacologic ascorbate (P-AscH(-)). Theranostics 2019, 9, 8109–8126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Chapman, J.; Levine, M.; Polireddy, K.; Drisko, J.; Chen, Q. High-dose parenteral ascorbate enhanced chemosensitivity of ovarian cancer and reduced toxicity of chemotherapy. Sci. Transl. Med. 2014, 6, 222ra218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, H.; Nam, A.; Song, K.H.; Lee, K.; Rebhun, R.B.; Seo, K.W. Anticancer effects of high-dose ascorbate on canine melanoma cell lines. Vet. Comp. Oncol. 2018, 16, 616–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Espey, M.G.; Krishna, M.C.; Mitchell, J.B.; Corpe, C.P.; Buettner, G.R.; Shacter, E.; Levine, M. Pharmacologic ascorbic acid concentrations selectively kill cancer cells: Action as a pro-drug to deliver hydrogen peroxide to tissues. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 13604–13609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, Y.; Wei, Z.; Pan, K.; Li, J.; Chen, Q. The function and mechanism of ferroptosis in cancer. Apoptosis 2020, 25, 786–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lőrincz, T.; Holczer, M.; Kapuy, O.; Szarka, A. The Interrelationship of Pharmacologic Ascorbate Induced Cell Death and Ferroptosis. Pathol Oncol Res 2019, 25, 669–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parra-Flores, P.; Riquelme, J.A.; Valenzuela-Bustamante, P.; Leiva-Navarrete, S.; Vivar, R.; Cayupi-Vivanco, J.; Castro, E.; Espinoza-Pérez, C.; Ruz-Cortés, F.; Pedrozo, Z.; et al. The Association of Ascorbic Acid, Deferoxamine and N-Acetylcysteine Improves Cardiac Fibroblast Viability and Cellular Function Associated with Tissue Repair Damaged by Simulated Ischemia/Reperfusion. Antioxidants 2019, 8, 614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Park, E.; Chung, S.W. ROS-mediated autophagy increases intracellular iron levels and ferroptosis by ferritin and transferrin receptor regulation. Cell Death Dis. 2019, 10, 822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ito, J.; Omiya, S.; Rusu, M.C.; Ueda, H.; Murakawa, T.; Tanada, Y.; Abe, H.; Nakahara, K.; Asahi, M.; Taneike, M.; et al. Iron derived from autophagy-mediated ferritin degradation induces cardiomyocyte death and heart failure in mice. Elife 2021, 10, e62174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.S.; SriRamaratnam, R.; Welsch, M.E.; Shimada, K.; Skouta, R.; Viswanathan, V.S.; Cheah, J.H.; Clemons, P.A.; Shamji, A.F.; Clish, C.B.; et al. Regulation of ferroptotic cancer cell death by GPX4. Cell 2014, 156, 317–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Magtanong, L.; Ko, P.J.; Dixon, S.J. Emerging roles for lipids in non-apoptotic cell death. Cell Death Differ. 2016, 23, 1099–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hangauer, M.J.; Viswanathan, V.S.; Ryan, M.J.; Bole, D.; Eaton, J.K.; Matov, A.; Galeas, J.; Dhruv, H.D.; Berens, M.E.; Schreiber, S.L.; et al. Drug-tolerant persister cancer cells are vulnerable to GPX4 inhibition. Nature 2017, 551, 247–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Viswanathan, V.S.; Ryan, M.J.; Dhruv, H.D.; Gill, S.; Eichhoff, O.M.; Seashore-Ludlow, B.; Kaffenberger, S.D.; Eaton, J.K.; Shimada, K.; Aguirre, A.J.; et al. Dependency of a therapy-resistant state of cancer cells on a lipid peroxidase pathway. Nature 2017, 547, 453–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaschler, M.M.; Andia, A.A.; Liu, H.; Csuka, J.M.; Hurlocker, B.; Vaiana, C.A.; Heindel, D.W.; Zuckerman, D.S.; Bos, P.H.; Reznik, E.; et al. FINO2 initiates ferroptosis through GPX4 inactivation and iron oxidation. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2018, 14, 507–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Kon, N.; Li, T.; Wang, S.J.; Su, T.; Hibshoosh, H.; Baer, R.; Gu, W. Ferroptosis as a p53-mediated activity during tumour suppression. Nature 2015, 520, 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mao, C.; Liu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Lei, G.; Yan, Y.; Lee, H.; Koppula, P.; Wu, S.; Zhuang, L.; Fang, B.; et al. DHODH-mediated ferroptosis defence is a targetable vulnerability in cancer. Nature 2021, 593, 586–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Putchala, M.C.; Ramani, P.; Sherlin, H.J.; Premkumar, P.; Natesan, A. Ascorbic acid and its pro-oxidant activity as a therapy for tumours of oral cavity—A systematic review. Arch. Oral. Biol. 2013, 58, 563–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Mata, A.M.O.F.; de Carvalho, R.M.; de Alencar, M.V.O.B.; de Carvalho Melo Cavalcante, A.A.; da Silva, B.B. Ascorbic acid in the prevention and treatment of cancer. Rev. Da Assoc. Médica Bras. 2016, 62, 680–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Frei, B.; Lawson, S. Vitamin C and cancer revisited. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 11037–11038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Yen, G.-C.; Duh, P.-D.; Tsai, H.-L. Antioxidant and pro-oxidant properties of ascorbic acid and gallic acid. Food Chem. 2002, 79, 307–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venturelli, S.; Sinnberg, T.; Niessner HBusch, M.C. Molecular mechanisms of pharmacological doses of ascorbate on cancer cells. Wien. Med. Wochenschr. 2015, 165, 251–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborthy, A.; Ramani, P.; Sherlin, H.J.; Premkumar, P.; Natesan, A. Antioxidant and pro-oxidant activity of Vitamin C in oral environment. Indian J. Dent. Res. Off. Publ. Indian Soc. Dent. Res. 2014, 25, 499–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, E.; Pauling, L. Supplemental ascorbate in the supportive treatment of cancer: Reevaluation of prolongation of survival times in terminal human cancer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1978, 75, 4538–4542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Creagan, E.T.; Moertel, C.G.; O’Fallon, J.R.; Schutt, A.J.; O’Connell, M.J.; Rubin, J.; Frytak, S. Failure of high-dose vitamin C (ascorbic acid) therapy to benefit patients with advanced cancer: A controlled trial. N. Engl. J. Med. 1979, 301, 687–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, P.M. Defining hormesis: Comments on Calabrese and Baldwin. Hum. Exp. Toxicol. 2002, 21, 99–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, W.; Wang, Y.; Xu, Y.; Guo, X.; Wang, B.; Sun, L.; Liu, L.; Cui, F.; Zhuang, Q.; Bao, X.; et al. The hypoxia-inducible factor renders cancer cells more sensitive to vitamin C-induced toxicity. J. Biol. Chem. 2014, 289, 3339–3351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cho, S.; Chae, J.S.; Shin, H.; Shin, Y.; Song, H.; Kim, Y.; Yoo, B.C.; Roh, K.; Cho, S.; Kil, E.J.; et al. Hormetic dose response to L-ascorbic acid as an anti-cancer drug in colorectal cancer cell lines according to SVCT-2 expression. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 11372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yun, J.; Mullarky, E.; Lu, C.; Bosch, K.N.; Kavalier, A.; Rivera, K.; Roper, J.; Chio, I.I.; Giannopoulou, E.G.; Rago, C.; et al. Vitamin C selectively kills KRAS and BRAF mutant colorectal cancer cells by targeting GAPDH. Science 2015, 350, 1391–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Corti, A.; Belcastro, E.; Pompella, A. Antitumoral effects of pharmacological ascorbate on gastric cancer cells: GLUT1 expression may not tell the whole story. Theranostics 2018, 8, 6035–6037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakanishi, K.; Hiramoto, K.; Sato, E.F.; Ooi, K. High-Dose Vitamin C Administration Inhibits the Invasion and Proliferation of Melanoma Cells in Mice Ovary. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2021, 44, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, C.D.; Song, E.J.; Yang, V.C.; Chao, C.C. Ascorbic acid increases drug accumulation and reverses vincristine resistance of human non-small-cell lung-cancer cells. Biochem. J. 1994, 301 Pt 3, 759–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schoenfeld, J.D.; Sibenaller, Z.A.; Mapuskar, K.A.; Wagner, B.A.; Cramer-Morales, K.L.; Furqan, M.; Sandhu, S.; Carlisle, T.L.; Smith, M.C.; Abu Hejleh, T.; et al. O2- and H2O2-Mediated Disruption of Fe Metabolism Causes the Differential Susceptibility of NSCLC and GBM Cancer Cells to Pharmacological Ascorbate. Cancer Cell 2017, 31, 487–500.e8, Erratum in: Cancer Cell 2017, 32, 268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- O’Leary, B.R.; Alexander, M.S.; Du, J.; Moose, D.L.; Henry, M.D.; Cullen, J.J. Pharmacological ascorbate inhibits pancreatic cancer metastases via a peroxide-mediated mechanism. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 17649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erudaitius, D.; Mantooth, J.; Huang, A.; Soliman, J.; Doskey, C.M.; Buettner, G.R.; Rodgers, V.G.J. Calculated cell-specific intracellular hydrogen peroxide concentration: Relevance in cancer cell susceptibility during ascorbate therapy. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2018, 120, 356–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilera, O.; Muñoz-Sagastibelza, M.; Torrejón, B.; Borrero-Palacios, A.; Del Puerto-Nevado, L.; Martínez-Useros, J.; Rodriguez-Remirez, M.; Zazo, S.; García, E.; Fraga, M.; et al. Vitamin C uncouples the Warburg metabolic switch in KRAS mutant colon cancer. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 47954–47965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, S.A.; Lee, D.H.; Moon, J.H.; Hong, S.W.; Shin, J.S.; Hwang, I.Y.; Shin, Y.J.; Kim, J.H.; Gong, E.Y.; Kim, S.M.; et al. L-Ascorbic acid can abrogate SVCT-2-dependent cetuximab resistance mediated by mutant KRAS in human colon cancer cells. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2016, 95, 200–208, Erratum in: Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2016, 97, 620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.J.; Jeong, J.H.; Lee, I.H.; Lee, J.; Jung, J.H.; Park, H.Y.; Lee, D.H.; Chae, Y.S. Effect of High-dose Vitamin C Combined With Anti-cancer Treatment on Breast Cancer Cells. Anticancer Res. 2019, 39, 751–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magrì, A.; Germano, G.; Lorenzato, A.; Lamba, S.; Chilà, R.; Montone, M.; Amodio, V.; Ceruti, T.; Sassi, F.; Arena, S.; et al. High-dose vitamin C enhances cancer immunotherapy. Sci. Transl. Med. 2020, 12, eaay8707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dayer, D.; Tabandeh, M.R.; Kazemi, M. The radio-sensitizing effect of pharmacological concentration of ascorbic acid on human pancreatic Cancer cells. Anti-Cancer Agents Med. Chem. 2020, 20, 1927–1932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pires, A.S.; Marques, C.R.; Encarnação, J.C.; Abrantes, A.M.; Marques, I.A.; Laranjo, M.; Oliveira, R.; Casalta-Lopes, J.E.; Gonçalves, A.C.; Sarmento-Ribeiro, A.B.; et al. Ascorbic acid Chemosensitizes colorectal Cancer cells and synergistically inhibits tumor growth. Front. Physiol. 2018, 9, 911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ghavami, G.; Sardari, S. Synergistic effect of vitamin C with Cisplatin for inhibiting proliferation of gastric Cancer cells. Iran. Biomed. J. 2020, 24, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Leekha, A.; Gurjar, B.S.; Tyagi, A.; Rizvi, M.A.; Verma, A.K. Vitamin C in synergism with cisplatin induces cell death in cervical cancer cells through altered redox cycling and p53 upregulation. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2016, 142, 2503–2514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.-.M.; Liu, S.-T.; Chen, S.-Y.; Chen, G.-S.; Wu, C.-C.; Huang, S.-M. Mechanisms and Applications of the Anti-cancer Effect of Pharmacological Ascorbic Acid in Cervical Cancer Cells. Front. Oncol. 2020, 10, 1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gokturk, D.; Kelebek, H.; Ceylan, S.; Yilmaz, D.M. The effect of ascorbic acid over the Etoposide- and Temozolomide-mediated cytotoxicity in Glioblastoma cell culture: A molecular study. Turk. Neurosurg. 2018, 28, 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Alexander, M.S.; Wilkes, J.G.; Schroeder, S.R.; Buettner, G.R.; Wagner, B.A.; Du, J.; Gibson-Corley, K.; O’Leary, B.R.; Spitz, D.R.; Buatti, J.M.; et al. Pharmacologic Ascorbate Reduces Radiation-Induced Normal Tissue Toxicity and Enhances Tumor Radiosensitization in Pancreatic Cancer. Cancer Res. 2018, 78, 6838–6851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lu, Y.-X.; Wu, Q.-N.; Chen, D.; Chen, L.-Z.; Wang, Z.-X.; Ren, C.; Mo, H.Y.; Chen, Y.; Sheng, H.; Wang, Y.N.; et al. Pharmacological Ascorbate suppresses growth of gastric Cancer cells with GLUT1 overexpression and enhances the efficacy of Oxaliplatin through redox modulation. Theranostics 2018, 8, 1312–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bharadwaj, R.; Sahu, B.P.; Haloi, J.; Laloo, D.; Barooah, P.; Keppen, C.; Deka, M.; Medhi, S. Combinatorial therapeutic approach for treatment of oral squamous cell carcinoma. Artif. Cells Nanomed. Biotechnol. 2019, 47, 571–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Yang, G.; Yan, Y.; Ma, Y.; Yang, Y. Vitamin C at high concentrations induces cytotoxicity in malignant melanoma but promotes tumor growth at low concentrations. Mol. Carcinog. 2017, 56, 1965–1976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moertel, C.G.; Fleming, T.R.; Creagan, E.T.; Rubin, J.; O’Connell, M.J.; Ames, M.M. High-dose vitamin C versus placebo in the treatment of patients with advanced cancer who have had no prior chemotherapy. A randomized double-blind comparison. N. Engl. J. Med. 1985, 312, 137–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shenoy, N.; Creagan, E.; Witzig, T.; Levine, M. Ascorbic Acid in Cancer Treatment: Let the Phoenix Fly. Cancer Cell 2018, 34, 700–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Carr, A.C.; Frei, B. Toward a new recommended dietary allowance for vitamin C based on antioxidant and health effects in humans. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1999, 69, 1086–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bertoia, M.; Albanes, D.; Mayne, S.T.; Mannisto, S.; Virtamo, J.; Wright, M.E. No association between fruit, vegetables, antioxidant nutrients and risk of renal cell carcinoma. Int. J. Cancer 2010, 126, 1504–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Heinen, M.M.; Verhage, B.A.; Goldbohm, R.A.; van den Brandt, P.A. Intake of vegetables, fruits, carotenoids and vitamins C and E and pancreatic cancer risk in The Netherlands Cohort Study. Int. J. Cancer 2012, 130, 147–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, M.; Bostick, R.M.; Kucuk, O.; Jones, D.P. Clinical trials of antioxidants as cancer prevention agents: Past, present, and future. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2011, 51, 1068–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Hunter, D.J.; Forman, M.R.; Rosner, B.A.; Speizer, F.E.; Colditz, G.; Manson, J.E.; Hankinson, S.E.; Willett, W.C. Dietary carotenoids and vitamins A, C, and E and risk of breast cancer. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1999, 91, 547–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michels, K.B.; Holmberg, L.; Bergkvist, L.; Ljung, H.; Bruce, A.; Wolk, A. Dietary antioxidant vitamins, retinol, and breast cancer incidence in a cohort of Swedish women. Int. J. Cancer 2001, 91, 563–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchinson, J.; Lentjes, M.A.; Greenwood, D.C.; Burley, V.J.; E Cade, J.; Cleghorn, C.L.; E Threapleton, D.; Key, T.J.; Cairns, B.J.; Keogh, R.H.; et al. Vitamin C intake from diary recordings and risk of breast cancer in the UK Dietary Cohort Consortium. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2012, 66, 561–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagel, G.; Linseisen, J.; van Gils, C.H.; Peeters, P.H.; Boutron-Ruault, M.C.; Clavel-Chapelon, F.; Romieu, I.; Tjonneland, A.; Olsen, A.; Roswall, N.; et al. Dietary beta-carotene, vitamin C and E intake and breast cancer risk in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC). Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2010, 119, 753–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Jenab, M.; Riboli, E.; Ferrari, P.; Sabate, J.; Slimani, N.; Norat, T.; Friesen, M.; Tjonneland, A.; Olsen, A.; Overvad, K.; et al. Plasma and dietary vitamin C levels and risk of gastric cancer in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC-EURGAST). Carcinogenesis 2006, 27, 2250–2257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Park, Y.; Spiegelman, D.; Hunter, D.J.; Albanes, D.; Bergkvist, L.; Buring, J.E.; Freudenheim, J.L.; Giovannucci, E.; Goldbohm, R.A.; Harnack, L.; et al. Intakes of vitamins A, C, and E and use of multiple vitamin supplements and risk of colon cancer: A pooled analysis of prospective cohort studies. Cancer Causes Control 2010, 21, 1745–1757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Sesso, H.D.; Glynn, R.J.; Christen, W.G.; Bubes, V.; E Manson, J.; E Buring, J.; Gaziano, J.M. Vitamin E and C supplementation and risk of cancer in men: Posttrial follow-up in the Physicians’ Health Study II randomized trial. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2014, 100, 915–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fritz, H.; Flower, G.; Weeks, L.; Cooley, K.; Callachan, M.; Mcgowan, J.; Skidmore, B.; Kirchner, L.; Seely, D. Intravenous Vitamin C and cancer: A systematic review. Integr. Cancer Ther. 2014, 13, 280–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, C.; Hutton, B.; Ng, T.; Shorr, R.; Clemons, M. Is there a role for oral or intravenous ascorbate (vitamin C) in treating patients with cancer? A systematic review. Oncologist 2015, 20, 210–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stephenson, C.M.; Levin, R.D.; Spector, T.; Lis, C.G. Phase I clinical trial to evaluate the safety, tolerability, and pharmacokinetics of high-dose intravenous ascorbic acid in patients with advanced cancer. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2013, 72, 139–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Welsh, J.L.; Wagner, B.A.; van’t Erve, T.J.; Zehr, P.S.; Berg, D.J.; Halfdanarson, T.R.; Yee, N.S.; Bodeker, K.L.; Du, J.; Roberts, L.J., 2nd; et al. Pharmacological ascorbate with gemcitabine for the control of metastatic and node-positive pancreatic cancer (PACMAN): Results from a phase I clinical trial. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2013, 71, 765–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Monti, D.A.; Mitchell, E.; Bazzan, A.J.; Littman, S.; Zabrecky, G.; Yeo, C.J.; Pillai, M.V.; Newberg, A.; Deshmukh, S.; Levine, M. Phase I evaluation of intravenous ascorbic acid in combination with gemcitabine and erlotinib in patients with metastatic pancreatic cancer. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e29794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffer, L.J.; Robitaille, L.; Zakarian, R.; Melnychuk, D.; Kavan, P.; Agulnik, J.; Cohen, V.; Small, D.; Miller, W.H. High-dose intravenous vitamin C combined with cytotoxic chemotherapy in patients with advanced cancer: A phase I-II clinical trial. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0120228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polireddy, K.; Dong, R.; Reed, G.; Yu, J.; Chen, P.; Williamson, S.; Violet, P.C.; Pessetto, Z.; Godwin, A.K.; Fan, F.; et al. High dose parenteral ascorbate inhibited pancreatic cancer growth and metastasis: Mechanisms and a Phase I/IIa study. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 17188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Nielsen, T.K.; Hojgaard, M.; Andersen, J.T.; Jorgensen, N.R.; Zerahn, B.; Kristensen, B.; Henriksen, T. Weekly ascorbic acid infusion in castration- resistant prostate cancer patients: A single-arm phase II trial. Transl. Androl. Urol. 2017, 6, 517–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Abdel-Latif, M.M.M.; Babar, M.; Kelleher, D.; Reynolds, J.V. A pilot study of the impact of Vitamin C supplementation with neoadjuvant chemoradiation on regulators of inflammation and carcinogenesis in esophageal cancer patients. J. Cancer Res. Ther. 2019, 15, 185–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Leary, B.R.; Houwen, F.K.; Johnson, C.L.; Allen, B.G.; Mezhir, J.J.; Berg, D.J.; Cullen, J.J.; Spitz, D.R. Pharmacological Ascorbate as an Adjuvant for Enhancing Radiation-Chemotherapy Responses in Gastric Adenocarcinoma. Radiat. Res. 2018, 189, 456–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cieslak, J.A.; Sibenaller, Z.A.; Walsh, S.A.; Ponto, L.L.; Du, J.; Sunderland, J.J.; Cullen, J.J. Fluorine-18-Labeled Thymidine Positron Emission Tomography (FLT-PET) as an Index of Cell Proliferation after Pharmacological Ascorbate-Based Therapy. Radiat. Res. 2016, 185, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Du, J.; Cieslak, J.A., 3rd; Welsh, J.L.; Sibenaller, Z.A.; Allen, B.G.; Wagner, B.A.; Kalen, A.L.; Doskey, C.M.; Strother, R.K.; Button, A.M.; et al. Pharmacological Ascorbate Radiosensitizes Pancreatic Cancer. Cancer Res. 2015, 75, 3314–3326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Haskins, A.H.; Buglewicz, D.J.; Hirakawa, H.; Fujimori, A.; Aizawa, Y.; Kato, T.A. Palmitoyl ascorbic acid 2-glucoside has the potential to protect mammalian cells from high-LET carbon-ion radiation. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 13822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Günes-Bayir, A.; Kiziltan, H.S. Palliative Vitamin C Application in Patients with Radiotherapy-Resistant Bone Metastases: A Retrospective Study. Nutr. Cancer 2015, 67, 921–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffer, L.J.; Levine, M.; Assouline, S.; Melnychuk, D.; Padayatty, S.J.; Rosadiuk, K.; Rousseau, C.; Robitaille, L.; Miller, W.H., Jr. Phase I clinical trial of i.v. ascorbic acid in advanced malignancy. Ann Oncol. 2008, 19, 1969–1974, Erratum in: Ann. Oncol. 2008, 19, 2095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Padayatty, S.J.; Riordan, H.D.; Hewitt, S.M.; Katz, A.; Hoffer, L.J.; Levine, M. Intravenously administered vitamin C as cancer therapy: Three cases. CMAJ 2006, 174, 937–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Takahashi, H.; Mizuno, H.; Yanagisawa, A. High-dose intravenous vitamin C improves quality of life in cancer patients. Personal. Med. Univ. 2012, 1, 49–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; He, M.M.; Wang, Z.X.; Li, S.; Jin, Y.; Ren, C.; Shi, S.M.; Bi, B.T.; Chen, S.Z.; Lv, Z.D.; et al. Phase I study of high-dose ascorbic acid with mFOLFOX6 or FOLFIRI in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer or gastric cancer. BMC Cancer 2019, 19, 460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carr, A.C.; Cook, J. Intravenous Vitamin C for Cancer therapy—Identifying the current gaps in our knowledge. Front. Physiol. 2018, 9, 1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nauman, G.; Gray, J.C.; Parkinson, R.; Levine, M.; Paller, C.J. Systematic review of intravenous ascorbate in cancer clinical trials. Antioxidants 2018, 7, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

| Type Drug | Cancer Type | Study Design | Ascorbate Concentration or Dose | Main Findings | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Radiotherapy | Pancreatic cancer | In vitro study. n = 1 cell line. Concomitant radiotherapy 2 Gy. | 4 mM during 24 h | Radio-sensitising effect of ascorbate | [85] |

| Fluorouracil | Colorectal and gastric cancer | In vitro and in vivo study. Cell lines of colorectal and gastric cancer. n = 60 mice. | 1 mM in vitro 4 g/kg intra peritoneal in vivo | In vitro synergy enhanced efficacy of chemotherapy | [79,86] |

| Anti-PD-1 and Anti-CTL-4 | Breast, colorectal, and pancreatic cancer | In vivo study. n = 13 immunocompetent syngeneic mice. | 4 g/kg intraperitoneal | Synergy and effective anti-tumour immune memory | [84] |

| Carboplatin | Gastric cancer | In vitro and in vivo study. n = 2 cell line. n = 60 athymic-nu/nu mice. | 1 mM in vitro 4 g/kg intraperitoneal in vivo | Enhanced efficacy | [79] |

| Cetuximab | Colorectal cancer with KRAS mutation | In vitro study. n = 5 cell lines. | 0.3, 0.5, and 0.7 mM | Synergy and abrogates resistance | [82] |

| Cisplatin | Gastric, cervical, oral squamous, and ovarian | In vitro studies. | Ranging from 0.0002 mM to 2 mM | Synergy enhanced efficacy | [87,88] |

| Doxorrubicin | Cervical cancer | In vitro. n = 2 cell lines. | 1.25, 3.3, and 16 mM | Synergy | [89] |

| Etoposide Temozolamide | Glioblastoma multiforme | In vitro. n = 1 cell line. | 1 mM | Enhanced efficacy | [90] |

| Gemcitabine | Pancreatic cancer | In vitro, in vivo. n = 6 cell lines. n = 32 mice. | 0.001 mM in vitro 4 g/kg intraperitoneal in vivo | Enhanced efficacy | [91] |

| Irinotecan Oxaliplatin | Colorectal and gastric cancer | In vitro and in vivo studies. | 0.15–13.3 mM in vitro 4 g/kg intraperitoneal in vivo | Synergy in vitro enhanced efficacy | [86,92] |

| Paclitaxel | Oral squamous and gastric cancer | In vivo and in vitro studies. n = 2 cell lines. n = 60 mice. | 1 mM in vitro 4 g/kg intraperitoneal | Enhanced efficacy | [79,93] |

| Vermurafenib | BRAF mutant melanoma | In vitro and in vivo study. n = 2 cell lines. n = 18 c57BL/6 mice. | 1.5 mM in vitro 0.03 mg/kg oral | Synergy and abrogates resistance | [94] |

| Study Characteristics | Ascorbate Dose | Results | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Observational studies | |||

| IV ascorbate in advanced tumours | n = 17 patients treated with ascorbate in dose: 30, 50, 70, 90, and 110 g/m2 for 4 consecutive days for 4 weeks. | 3 patients had stable disease, 13 had progressive disease. | [110] |

| IV ascorbate in advanced pancreatic adenocarcinoma | n = 11 patients treated with IV ascorbate ranging 15–125 g twice weekly, with gemcitabine. | Mean plasma ascorbate levels were significantly higher than baseline. Mean survival time of subjects completing 8 weeks of therapy was 13 ± 2 months. | [111] |

| IV ascorbate in pancreatic adenocarcinoma stage IV | n = 14. 50, 75, and 100 g per infusion (3 cohorts) thrice weekly for 8 weeks. Concurrent therapy with gemcitabine and erlotinib. | 50% of patients had stable disease. Survival analysis excluded 5 patients who progressed quickly (3 died). Overall mean survival was 182 days. | [112] |

| Stage III and IV serous ovarian cancer | n = 25. 75–100 g IV ascorbate twice weekly for 12 months (target plasma concentrations 20–23 mM). | 8.7 month increase in progressive-free survival in ascorbate-treated arm. | [48] |

| Various cancer types (lung, rectum, colon, bladder, ovary, cervix, tonsil, breast, biliary tract) | n = 16. 1.5 g/kg body weight infused for three times | Patients experienced stable disease, increased QOL, and functional improvement. | [113] |

| Glioblastoma under treatment with chemoradiation with concomitant temozolamide | n = 13. Radiation phase: radiation (61.2 Gy in 34 fractions), temozolamide, and ascorbate (ranging from 15 to 125 g, 3 times per week for 7 weeks). Adjuvant phase: ascorbate (2 times per week, dose escalation until 20 mM plasma concentration, around 85 g infusion). | Progression-free survival 13.3 months. Overall survival 21.5 months. | [78] |

| Advanced stage non-small-cell lung cancer | n = 14. 1 cycle is 21 days. IV carboplatin, IV paclitaxel, and IV pharmacological ascorbate (two 75 g infusions per week, up to 4 cycles). | Partial responses (n = 4) and stable disease (n = 9), disease progression. | [78] |

| Locally advanced or metastatic prostate cancer | n = 14. IV ascorbate 25–100 g. Concurrent chemotherapy: Gemcitabine. | Patients experienced a mix of stable disease, partial response, and disease progression. | [114] |

| Castration-resistant prostate cancer | n = 23. 5 g weekly during week 1, 30 g weekly during week 2, and 60 g weekly during weeks 3–12. | Adverse events were thought to be more likely related to disease progression than ascorbic acid. | [115] |

| Phase I clinical trials | |||

| Locally advanced pancreatic cancer treated with chemoradiation | IV ascorbate concomitant to radiation and gemcitabine. Ascorbate dosing: 50 g administered intravenously (by IV) during radiation therapy, for approximately 5 to 6 weeks. | US National Library of Medicine. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/ NCT01852890 (2018). Accessed on 1 May 2022. | On going |

| Glioblastoma multiforme treated with chemoradiation (temozolamide) | IV ascorbate concomitant to radiation and temozolamide. Ascorbate dosing: 15, 25, 50, 62.5, 75, and 87.5 g administered by IV three times a week until 1 month after radiation is completed (approximately 12 weeks). | US National Library of Medicine. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/ NCT01752491. Accessed on 1 May 2022. | On going |

| Metastatic pancreatic cancer treated with gemcitabine and nab-paclitaxel | The dose level for phase II patients will be determined following completion of the phase 1b study based on response from 3–6 patients receiving the designated dose level of ascorbic acid. | US National Library of Medicine. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/ NCT03797443. Accessed on 1 May 2022. | On going |

| Phase II clinical trials | |||

| Stage IV non-small-cell lung cancer patients treated with chemotherapy | IV ascorbate: 75 g per infusion, two infusions per week (each 3 weeks) for 4 cycles. | US National Library of Medicine. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/ NCT02420314. Accessed on 1 May 2022. | On going |

| Pharmacological ascorbate combined with radiation and temozolamide in glioblastoma multiforme: a phase II trial | Intravenous infusions of ascorbate of 87.5 g administered three times weekly during chemoradiation. After radiation, ascorbate is administered twice weekly through the end of cycle 6 of temozolomide. | US National Library of Medicine. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/ NCT02344355. Accessed on 1 May 2022. | On going |

| Various solid tumour malignancies (colorectal, pancreatic, and lung cancer) | IV ascorbate: 1.25 g/kg for 4 days per week for 2–4 consecutive weeks or up to 6 months. | US National Library of Medicine. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/ NCT03146962. Accessed on 1 May 2022. | On going |

| Pharmacological ascorbate with concurrent chemotherapy and radiation therapy for non-small-cell lung cancer | IV ascorbate dosing: 75 g per infusion. 3 infusion per calendar week. | US National Library of Medicine. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/ NCT02905591. Accessed on 1 May 2022. | On going |

| Pharmacological ascorbate, gemcitabine, nab-paclitaxel for metastatic pancreatic cancer | IV dosing: 75 g of ascorbate 3 times per calendar week for each week of the chemotherapy cycle. | US National Library of Medicine. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/ NCT02905578. Accessed on 1 May 2022. | On going |

| Ascorbic acid in combination with docetaxel in men with metastatic prostate cancer | Patients receive docetaxel IV on day 1 and ascorbic acid IV twice weekly. The first ascorbic acid treatment will be given on day 1 (same day as docetaxel). Treatment repeats every 21 days for 8 courses in the absence of disease progression or unacceptable toxicity. | US National Library of Medicine. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/ NCT02516670. Accessed on 1 May 2022. | On going |

| Phase III clinical trials | |||

| IV ascorbic acid in advanced gastric cancer | In patients treated with chemotherapy, ascorbate IV 20 g day (days 1–3) will be administered every 2 weeks. | US National Library of Medicine. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/ NCT03015675. Accessed on 1 May 2022. | On going |

| Stage IV colorectal cancer | IV ascorbic acid (1.5 g/kg/day, days 1–3, every 2 weeks) in combination with FOLFOX and bevacizumab versus treatment with FOLFOX and bevacizumab alone as first-line therapy for advanced colorectal cancer. | US National Library of Medicine. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/ NCT02969681. Accessed on 1 May 2022. | On going |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

González-Montero, J.; Chichiarelli, S.; Eufemi, M.; Altieri, F.; Saso, L.; Rodrigo, R. Ascorbate as a Bioactive Compound in Cancer Therapy: The Old Classic Strikes Back. Molecules 2022, 27, 3818. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules27123818

González-Montero J, Chichiarelli S, Eufemi M, Altieri F, Saso L, Rodrigo R. Ascorbate as a Bioactive Compound in Cancer Therapy: The Old Classic Strikes Back. Molecules. 2022; 27(12):3818. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules27123818

Chicago/Turabian StyleGonzález-Montero, Jaime, Silvia Chichiarelli, Margherita Eufemi, Fabio Altieri, Luciano Saso, and Ramón Rodrigo. 2022. "Ascorbate as a Bioactive Compound in Cancer Therapy: The Old Classic Strikes Back" Molecules 27, no. 12: 3818. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules27123818

APA StyleGonzález-Montero, J., Chichiarelli, S., Eufemi, M., Altieri, F., Saso, L., & Rodrigo, R. (2022). Ascorbate as a Bioactive Compound in Cancer Therapy: The Old Classic Strikes Back. Molecules, 27(12), 3818. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules27123818